User login

Patients With Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis Want More Disease Information

Adults with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) expressed interest in more knowledge of prognosis, etiology, treatment, and living well with the disease, based on new survey data presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference.

HP is caused by environmental exposure and is often incurable, and patients are challenged with identifying and mitigating the exposure with limited guidance, wrote Janani Varadarajan, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

Surveys Conducted to Understand Patient Concerns

To better identify patient-perceived HP knowledge gaps and develop educational resources, the researchers assessed 21 adults diagnosed with HP. Patients underwent interviews using nominal group technique (NGT) for group consensus and completed a survey on educational preferences. The mean age of the participants was 69.5 years, and 81% were women.

The researchers conducted five NGTs. Participants were asked two questions: What questions about your HP do you have that keep you awake at night?” and “What information do you want about your HP that you cannot find?” They also voted on responses that were grouped by theme.

The top themes that emerged from the interviews were concerns about natural history and prognosis of HP (28.3%), current treatment options and therapeutic research (22.5%), epidemiology and etiology (17.5%), living well with HP (15.4%), origin and management of symptoms (8.3%), identifying and mitigating exposures (4.6%), and methods of information uptake and dissemination (3.3%).

The findings were limited by the relatively small sample size. However, the results will inform the development of educational materials on the virtual Patient Activated Learning System, the researchers noted in their abstract. “This curriculum will be a component of a larger support intervention that aims to improve patient knowledge, self-efficacy, and HRQOL [health-related quality of life],” they said.

Findings Will Fuel Needed Education

Recognizing more interstitial lung disease (ILD) has led to diagnosing more hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and it is important to keep patients’ concerns in mind, said Aamir Ajmeri, MD, assistant professor of clinical thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, in an interview.

“If patients research ILD online, most of the literature is based on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” he said. “IPF literature can be frightening because patients will see a median 2- to 5-year survival rate from time of diagnosis, the need for lung transplant, and progressive hypoxemia; however, all of this may not be true in HP,” he noted.

“HP is more of a spectrum, but it is more difficult for patient to understand when we say ‘your lungs have reacted to something in your environment,’ and they will ask ‘what can I do to change this?’” Dr. Ajmeri told this news organization. “That is why these types of studies, where we recognize what patients need and how they can learn more about their diagnosis, are very important,” he said.

The study findings were not surprising, Dr. Ajmeri said. “We have a large cohort of patients with HP at Temple Health, and these are the same questions they ask me and my colleagues,” he said. “It can be tough for patients to grasp this diagnosis. We know it is related to something inhaled from the environment, but it may be difficult to pinpoint,” he said.

In patient-centered research, patients can help shed light onto the needs that are unmet for the disease process by asking hypothesis-generating questions, Dr. Ajmeri said. For example, he said he is frequently asked by patients why HP continues to recur after they have remediated a home (potential source of exposure) and been on medication.

“The study was limited in part by the small sample size but captured a good representation of what patients are asking their physicians about,” Dr. Ajmeri said. Although it is always preferable to have more patients, the findings are important, “and the educational materials that they will lead to are greatly needed,” he said.

The study was supported by the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund, the American Lung Association Catalyst Award, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ajmeri had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) expressed interest in more knowledge of prognosis, etiology, treatment, and living well with the disease, based on new survey data presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference.

HP is caused by environmental exposure and is often incurable, and patients are challenged with identifying and mitigating the exposure with limited guidance, wrote Janani Varadarajan, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

Surveys Conducted to Understand Patient Concerns

To better identify patient-perceived HP knowledge gaps and develop educational resources, the researchers assessed 21 adults diagnosed with HP. Patients underwent interviews using nominal group technique (NGT) for group consensus and completed a survey on educational preferences. The mean age of the participants was 69.5 years, and 81% were women.

The researchers conducted five NGTs. Participants were asked two questions: What questions about your HP do you have that keep you awake at night?” and “What information do you want about your HP that you cannot find?” They also voted on responses that were grouped by theme.

The top themes that emerged from the interviews were concerns about natural history and prognosis of HP (28.3%), current treatment options and therapeutic research (22.5%), epidemiology and etiology (17.5%), living well with HP (15.4%), origin and management of symptoms (8.3%), identifying and mitigating exposures (4.6%), and methods of information uptake and dissemination (3.3%).

The findings were limited by the relatively small sample size. However, the results will inform the development of educational materials on the virtual Patient Activated Learning System, the researchers noted in their abstract. “This curriculum will be a component of a larger support intervention that aims to improve patient knowledge, self-efficacy, and HRQOL [health-related quality of life],” they said.

Findings Will Fuel Needed Education

Recognizing more interstitial lung disease (ILD) has led to diagnosing more hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and it is important to keep patients’ concerns in mind, said Aamir Ajmeri, MD, assistant professor of clinical thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, in an interview.

“If patients research ILD online, most of the literature is based on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” he said. “IPF literature can be frightening because patients will see a median 2- to 5-year survival rate from time of diagnosis, the need for lung transplant, and progressive hypoxemia; however, all of this may not be true in HP,” he noted.

“HP is more of a spectrum, but it is more difficult for patient to understand when we say ‘your lungs have reacted to something in your environment,’ and they will ask ‘what can I do to change this?’” Dr. Ajmeri told this news organization. “That is why these types of studies, where we recognize what patients need and how they can learn more about their diagnosis, are very important,” he said.

The study findings were not surprising, Dr. Ajmeri said. “We have a large cohort of patients with HP at Temple Health, and these are the same questions they ask me and my colleagues,” he said. “It can be tough for patients to grasp this diagnosis. We know it is related to something inhaled from the environment, but it may be difficult to pinpoint,” he said.

In patient-centered research, patients can help shed light onto the needs that are unmet for the disease process by asking hypothesis-generating questions, Dr. Ajmeri said. For example, he said he is frequently asked by patients why HP continues to recur after they have remediated a home (potential source of exposure) and been on medication.

“The study was limited in part by the small sample size but captured a good representation of what patients are asking their physicians about,” Dr. Ajmeri said. Although it is always preferable to have more patients, the findings are important, “and the educational materials that they will lead to are greatly needed,” he said.

The study was supported by the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund, the American Lung Association Catalyst Award, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ajmeri had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adults with hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) expressed interest in more knowledge of prognosis, etiology, treatment, and living well with the disease, based on new survey data presented at the American Thoracic Society International Conference.

HP is caused by environmental exposure and is often incurable, and patients are challenged with identifying and mitigating the exposure with limited guidance, wrote Janani Varadarajan, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

Surveys Conducted to Understand Patient Concerns

To better identify patient-perceived HP knowledge gaps and develop educational resources, the researchers assessed 21 adults diagnosed with HP. Patients underwent interviews using nominal group technique (NGT) for group consensus and completed a survey on educational preferences. The mean age of the participants was 69.5 years, and 81% were women.

The researchers conducted five NGTs. Participants were asked two questions: What questions about your HP do you have that keep you awake at night?” and “What information do you want about your HP that you cannot find?” They also voted on responses that were grouped by theme.

The top themes that emerged from the interviews were concerns about natural history and prognosis of HP (28.3%), current treatment options and therapeutic research (22.5%), epidemiology and etiology (17.5%), living well with HP (15.4%), origin and management of symptoms (8.3%), identifying and mitigating exposures (4.6%), and methods of information uptake and dissemination (3.3%).

The findings were limited by the relatively small sample size. However, the results will inform the development of educational materials on the virtual Patient Activated Learning System, the researchers noted in their abstract. “This curriculum will be a component of a larger support intervention that aims to improve patient knowledge, self-efficacy, and HRQOL [health-related quality of life],” they said.

Findings Will Fuel Needed Education

Recognizing more interstitial lung disease (ILD) has led to diagnosing more hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and it is important to keep patients’ concerns in mind, said Aamir Ajmeri, MD, assistant professor of clinical thoracic medicine and surgery at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia, in an interview.

“If patients research ILD online, most of the literature is based on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,” he said. “IPF literature can be frightening because patients will see a median 2- to 5-year survival rate from time of diagnosis, the need for lung transplant, and progressive hypoxemia; however, all of this may not be true in HP,” he noted.

“HP is more of a spectrum, but it is more difficult for patient to understand when we say ‘your lungs have reacted to something in your environment,’ and they will ask ‘what can I do to change this?’” Dr. Ajmeri told this news organization. “That is why these types of studies, where we recognize what patients need and how they can learn more about their diagnosis, are very important,” he said.

The study findings were not surprising, Dr. Ajmeri said. “We have a large cohort of patients with HP at Temple Health, and these are the same questions they ask me and my colleagues,” he said. “It can be tough for patients to grasp this diagnosis. We know it is related to something inhaled from the environment, but it may be difficult to pinpoint,” he said.

In patient-centered research, patients can help shed light onto the needs that are unmet for the disease process by asking hypothesis-generating questions, Dr. Ajmeri said. For example, he said he is frequently asked by patients why HP continues to recur after they have remediated a home (potential source of exposure) and been on medication.

“The study was limited in part by the small sample size but captured a good representation of what patients are asking their physicians about,” Dr. Ajmeri said. Although it is always preferable to have more patients, the findings are important, “and the educational materials that they will lead to are greatly needed,” he said.

The study was supported by the Stony Wold-Herbert Fund, the American Lung Association Catalyst Award, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ajmeri had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Why Are We Undertreating So Many Pulmonary Embolisms?

LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA — A small fraction of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) who are eligible for advanced therapies are actually getting them, reported investigators who conducted a big data analysis.

“Advanced PE therapy seems to be vulnerable to disparate use, and perhaps underuse,” Sahil Parikh, MD, a cardiovascular interventionalist at the Columbia University Medical Center in New York, said when he presented results from the REAL-PE study at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) 2024 Scientific Sessions.

The underuse of advanced PE therapies is “the controversy,” Dr. Parikh said after his presentation. “It remains unclear what the role of invasive therapy is in the management of so-called high-intermediate–risk people. There isn’t a Class 1 guideline recommendation, and there is a very rapidly evolving trend that we’re increasingly treating these patients invasively,” he said.

“However, if you come to these meetings [such as SCAI], you might think everyone is getting one of these devices, but these data show that’s not the case,” Dr. Parikh said.

The analysis mined deidentified data from Truveta, a collective of health systems that provides regulatory-grade electronic health record data for research.

The researchers accessed data on patients treated with ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy, identified from claims codes. Patient characteristics — age, race, ethnicity, sex, comorbidities, and diagnoses — were also accessed for the analysis. Earlier results were published in the January issue of the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angioplasty Interventions.

Less Intervention for Black Patients and Women

White patients were more likely to receive advanced therapy than were Black patients (0.5% vs 0.37%; P = .000), Dr. Parikh reported, and women were less likely to receive advanced therapy than were men (0.41% vs 0.55%; P = .000).

The only discernable differences in outcomes were in major bleeding events in the 7 days after the procedure, which affected more White patients than it did Black patients (13.9% vs 9.3%) and affected more women than it did men (16.6% vs 11.1%).

What’s noteworthy about this study is that it demonstrates the potential of advanced data analytics to identify disparities in care and outcomes, Dr. Parikh said during his presentation. “These analyses provide a means of evaluating disparities in real clinical practice, both in the area of PE and otherwise, and may also be used for real-time monitoring of clinical decision-making and decisional support,” he said. “We do think that both novel and established therapies can benefit equally from similar types of analyses.”

Big Data Signaling Disparities

“That’s where these data are helpful,” Dr. Parikh explained. They provide “a real snapshot of how many procedures are being performed and in what kinds of patients. The low number of patients getting the procedure would suggest that there are probably more patients who would be eligible for treatment based on some of the emerging consensus documents, and they’re not receiving them.”

The data are “hypotheses generating,” Dr. Parikh said in an interview. “These hypotheses have to be evaluated further in more granular databases.”

REAL-PE is also a “clarion call” for clinical trials of investigative devices going forward, he said. “In those trials, we need to endeavor to enroll enough women and men, minority and nonminority patients so that we can make meaningful assessments of differences in efficacy and safety.”

This study is “real proof that big data can be used to provide information on outcomes for patients in a very rapid manner; that’s really exciting,” said Ethan Korngold, MD, chair of structural and interventional cardiology at the Providence Health Institute in Portland, Oregon. “This is an area of great research with great innovation, and it’s proof that, with these type of techniques using artificial intelligence and big data, we can generate data quickly on how we’re doing and what kind of patients we’re reaching.”

Findings like these may also help identify sources of the disparities, Dr. Korngold added.

“This shows we need to be reaching every patient with advanced therapies,” he said. “Different hospitals have different capabilities and different expertise in this area and they reach different patient populations. A lot of the difference in utilization stems from this fact,” he said.

“It just underscores the fact that we need to standardize our treatment approaches, and then we need to reach every person who’s suffering from this disease,” Dr. Korngold said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA — A small fraction of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) who are eligible for advanced therapies are actually getting them, reported investigators who conducted a big data analysis.

“Advanced PE therapy seems to be vulnerable to disparate use, and perhaps underuse,” Sahil Parikh, MD, a cardiovascular interventionalist at the Columbia University Medical Center in New York, said when he presented results from the REAL-PE study at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) 2024 Scientific Sessions.

The underuse of advanced PE therapies is “the controversy,” Dr. Parikh said after his presentation. “It remains unclear what the role of invasive therapy is in the management of so-called high-intermediate–risk people. There isn’t a Class 1 guideline recommendation, and there is a very rapidly evolving trend that we’re increasingly treating these patients invasively,” he said.

“However, if you come to these meetings [such as SCAI], you might think everyone is getting one of these devices, but these data show that’s not the case,” Dr. Parikh said.

The analysis mined deidentified data from Truveta, a collective of health systems that provides regulatory-grade electronic health record data for research.

The researchers accessed data on patients treated with ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy, identified from claims codes. Patient characteristics — age, race, ethnicity, sex, comorbidities, and diagnoses — were also accessed for the analysis. Earlier results were published in the January issue of the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angioplasty Interventions.

Less Intervention for Black Patients and Women

White patients were more likely to receive advanced therapy than were Black patients (0.5% vs 0.37%; P = .000), Dr. Parikh reported, and women were less likely to receive advanced therapy than were men (0.41% vs 0.55%; P = .000).

The only discernable differences in outcomes were in major bleeding events in the 7 days after the procedure, which affected more White patients than it did Black patients (13.9% vs 9.3%) and affected more women than it did men (16.6% vs 11.1%).

What’s noteworthy about this study is that it demonstrates the potential of advanced data analytics to identify disparities in care and outcomes, Dr. Parikh said during his presentation. “These analyses provide a means of evaluating disparities in real clinical practice, both in the area of PE and otherwise, and may also be used for real-time monitoring of clinical decision-making and decisional support,” he said. “We do think that both novel and established therapies can benefit equally from similar types of analyses.”

Big Data Signaling Disparities

“That’s where these data are helpful,” Dr. Parikh explained. They provide “a real snapshot of how many procedures are being performed and in what kinds of patients. The low number of patients getting the procedure would suggest that there are probably more patients who would be eligible for treatment based on some of the emerging consensus documents, and they’re not receiving them.”

The data are “hypotheses generating,” Dr. Parikh said in an interview. “These hypotheses have to be evaluated further in more granular databases.”

REAL-PE is also a “clarion call” for clinical trials of investigative devices going forward, he said. “In those trials, we need to endeavor to enroll enough women and men, minority and nonminority patients so that we can make meaningful assessments of differences in efficacy and safety.”

This study is “real proof that big data can be used to provide information on outcomes for patients in a very rapid manner; that’s really exciting,” said Ethan Korngold, MD, chair of structural and interventional cardiology at the Providence Health Institute in Portland, Oregon. “This is an area of great research with great innovation, and it’s proof that, with these type of techniques using artificial intelligence and big data, we can generate data quickly on how we’re doing and what kind of patients we’re reaching.”

Findings like these may also help identify sources of the disparities, Dr. Korngold added.

“This shows we need to be reaching every patient with advanced therapies,” he said. “Different hospitals have different capabilities and different expertise in this area and they reach different patient populations. A lot of the difference in utilization stems from this fact,” he said.

“It just underscores the fact that we need to standardize our treatment approaches, and then we need to reach every person who’s suffering from this disease,” Dr. Korngold said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

LONG BEACH, CALIFORNIA — A small fraction of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE) who are eligible for advanced therapies are actually getting them, reported investigators who conducted a big data analysis.

“Advanced PE therapy seems to be vulnerable to disparate use, and perhaps underuse,” Sahil Parikh, MD, a cardiovascular interventionalist at the Columbia University Medical Center in New York, said when he presented results from the REAL-PE study at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) 2024 Scientific Sessions.

The underuse of advanced PE therapies is “the controversy,” Dr. Parikh said after his presentation. “It remains unclear what the role of invasive therapy is in the management of so-called high-intermediate–risk people. There isn’t a Class 1 guideline recommendation, and there is a very rapidly evolving trend that we’re increasingly treating these patients invasively,” he said.

“However, if you come to these meetings [such as SCAI], you might think everyone is getting one of these devices, but these data show that’s not the case,” Dr. Parikh said.

The analysis mined deidentified data from Truveta, a collective of health systems that provides regulatory-grade electronic health record data for research.

The researchers accessed data on patients treated with ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis or mechanical thrombectomy, identified from claims codes. Patient characteristics — age, race, ethnicity, sex, comorbidities, and diagnoses — were also accessed for the analysis. Earlier results were published in the January issue of the Journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Angioplasty Interventions.

Less Intervention for Black Patients and Women

White patients were more likely to receive advanced therapy than were Black patients (0.5% vs 0.37%; P = .000), Dr. Parikh reported, and women were less likely to receive advanced therapy than were men (0.41% vs 0.55%; P = .000).

The only discernable differences in outcomes were in major bleeding events in the 7 days after the procedure, which affected more White patients than it did Black patients (13.9% vs 9.3%) and affected more women than it did men (16.6% vs 11.1%).

What’s noteworthy about this study is that it demonstrates the potential of advanced data analytics to identify disparities in care and outcomes, Dr. Parikh said during his presentation. “These analyses provide a means of evaluating disparities in real clinical practice, both in the area of PE and otherwise, and may also be used for real-time monitoring of clinical decision-making and decisional support,” he said. “We do think that both novel and established therapies can benefit equally from similar types of analyses.”

Big Data Signaling Disparities

“That’s where these data are helpful,” Dr. Parikh explained. They provide “a real snapshot of how many procedures are being performed and in what kinds of patients. The low number of patients getting the procedure would suggest that there are probably more patients who would be eligible for treatment based on some of the emerging consensus documents, and they’re not receiving them.”

The data are “hypotheses generating,” Dr. Parikh said in an interview. “These hypotheses have to be evaluated further in more granular databases.”

REAL-PE is also a “clarion call” for clinical trials of investigative devices going forward, he said. “In those trials, we need to endeavor to enroll enough women and men, minority and nonminority patients so that we can make meaningful assessments of differences in efficacy and safety.”

This study is “real proof that big data can be used to provide information on outcomes for patients in a very rapid manner; that’s really exciting,” said Ethan Korngold, MD, chair of structural and interventional cardiology at the Providence Health Institute in Portland, Oregon. “This is an area of great research with great innovation, and it’s proof that, with these type of techniques using artificial intelligence and big data, we can generate data quickly on how we’re doing and what kind of patients we’re reaching.”

Findings like these may also help identify sources of the disparities, Dr. Korngold added.

“This shows we need to be reaching every patient with advanced therapies,” he said. “Different hospitals have different capabilities and different expertise in this area and they reach different patient populations. A lot of the difference in utilization stems from this fact,” he said.

“It just underscores the fact that we need to standardize our treatment approaches, and then we need to reach every person who’s suffering from this disease,” Dr. Korngold said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Age, Race, and Insurance Status May Effect Initial Sarcoidosis Severity

presented at the American Thoracic Society’s International Conference 2024.

“We know socioeconomic status plays an important role in health outcomes; however, there is little research into the impact of socioeconomic status on patients with sarcoidosis, particularly with disease severity,” said lead author Joshua Boron, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, in an interview. Identification of patients at higher risk of developing severe lung disease can help clinicians stratify these patients, he said.

Overall, the risk for severe lung disease at initial presentation was nearly three times higher in patients with no insurance than in those with private insurance and nearly three times higher in Black patients than in White patients (odds ratio [OR], 2.97 and 2.83, respectively). In addition, older age was associated with increased risk of fibrosis, with an OR of 1.03 per year increase in age.

No differences in fibrosis at presentation occurred based on sex or median income, and no difference in the likelihood of fibrosis at presentation appeared between patients with Medicaid vs private insurance.

“We were surprised at the degree of risk associated with no insurance,” said Dr. Boron. The researchers also were surprised at the lack of association between higher risk of severe stage lung disease in sarcoidosis patients and zip code estimates of household income as an indicator of socioeconomic status, he said.

For clinical practice, the study findings highlight the potentially increased risk for fibrotic lung disease among patients who are older, uninsured, and African American, said Dr. Boron.

“A limitation of our study was the utilization of zip code based on the US Census Bureau to get an estimation of average household income — a particular limitation in our city because of gentrification over the past few decades,” Dr. Boron said in an interview. “Utilizing area deprivation indices could be a better marker for identifying household income and give a more accurate representation of the true impact of socioeconomic disparities and severity of sarcoidosis at presentation,” he said.

Pinpointing Persistent Disparities

“We know there are multiple sources of disparities in the sarcoidosis population,” said Rohit Gupta, MD, director of the sarcoidosis program at Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, in an interview.

The current study identified the relationship between several socioeconomic factors and sarcoidosis severity, showing greater disease severity in people experiencing socioeconomic inequalities, said Dr. Gupta, who was not involved in the study.

“I have personally seen this [disparity] in clinic,” said Dr. Gupta. However, supporting data are limited, aside from recent studies published in the last few years by researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he said. The current study reflects those previous findings that people suffering from inequality have worse medical care, he added.

Overall, the findings were not surprising, “as we know this cohort of patients have chronic disease and worse morbidity and, in some cases, higher mortality,” but the results reinforce the need to pay closer attention to socioeconomic factors, said Dr. Gupta.

In practice, “we might use these findings as a reminder that when we see these patients for the first time, we should pay closer attention because they might need higher care,” he said. “The study also suggests these patients are coming late to a center of excellence,” he noted. When patients with socioeconomic disparities are seen for sarcoidosis at community hospitals and small centers, providers should keep in mind that their disease might progress faster and, therefore, send them to advanced centers earlier, he said.

The study was limited to the use of data from a single center and by the retrospective design, Dr. Gupta said. “Additional research should focus on building better platforms to understand these disparities,” he emphasized, so clinicians can develop plans not only to identify inequalities but also to address them.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gupta had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

presented at the American Thoracic Society’s International Conference 2024.

“We know socioeconomic status plays an important role in health outcomes; however, there is little research into the impact of socioeconomic status on patients with sarcoidosis, particularly with disease severity,” said lead author Joshua Boron, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, in an interview. Identification of patients at higher risk of developing severe lung disease can help clinicians stratify these patients, he said.

Overall, the risk for severe lung disease at initial presentation was nearly three times higher in patients with no insurance than in those with private insurance and nearly three times higher in Black patients than in White patients (odds ratio [OR], 2.97 and 2.83, respectively). In addition, older age was associated with increased risk of fibrosis, with an OR of 1.03 per year increase in age.

No differences in fibrosis at presentation occurred based on sex or median income, and no difference in the likelihood of fibrosis at presentation appeared between patients with Medicaid vs private insurance.

“We were surprised at the degree of risk associated with no insurance,” said Dr. Boron. The researchers also were surprised at the lack of association between higher risk of severe stage lung disease in sarcoidosis patients and zip code estimates of household income as an indicator of socioeconomic status, he said.

For clinical practice, the study findings highlight the potentially increased risk for fibrotic lung disease among patients who are older, uninsured, and African American, said Dr. Boron.

“A limitation of our study was the utilization of zip code based on the US Census Bureau to get an estimation of average household income — a particular limitation in our city because of gentrification over the past few decades,” Dr. Boron said in an interview. “Utilizing area deprivation indices could be a better marker for identifying household income and give a more accurate representation of the true impact of socioeconomic disparities and severity of sarcoidosis at presentation,” he said.

Pinpointing Persistent Disparities

“We know there are multiple sources of disparities in the sarcoidosis population,” said Rohit Gupta, MD, director of the sarcoidosis program at Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, in an interview.

The current study identified the relationship between several socioeconomic factors and sarcoidosis severity, showing greater disease severity in people experiencing socioeconomic inequalities, said Dr. Gupta, who was not involved in the study.

“I have personally seen this [disparity] in clinic,” said Dr. Gupta. However, supporting data are limited, aside from recent studies published in the last few years by researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he said. The current study reflects those previous findings that people suffering from inequality have worse medical care, he added.

Overall, the findings were not surprising, “as we know this cohort of patients have chronic disease and worse morbidity and, in some cases, higher mortality,” but the results reinforce the need to pay closer attention to socioeconomic factors, said Dr. Gupta.

In practice, “we might use these findings as a reminder that when we see these patients for the first time, we should pay closer attention because they might need higher care,” he said. “The study also suggests these patients are coming late to a center of excellence,” he noted. When patients with socioeconomic disparities are seen for sarcoidosis at community hospitals and small centers, providers should keep in mind that their disease might progress faster and, therefore, send them to advanced centers earlier, he said.

The study was limited to the use of data from a single center and by the retrospective design, Dr. Gupta said. “Additional research should focus on building better platforms to understand these disparities,” he emphasized, so clinicians can develop plans not only to identify inequalities but also to address them.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gupta had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

presented at the American Thoracic Society’s International Conference 2024.

“We know socioeconomic status plays an important role in health outcomes; however, there is little research into the impact of socioeconomic status on patients with sarcoidosis, particularly with disease severity,” said lead author Joshua Boron, MD, of Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, in an interview. Identification of patients at higher risk of developing severe lung disease can help clinicians stratify these patients, he said.

Overall, the risk for severe lung disease at initial presentation was nearly three times higher in patients with no insurance than in those with private insurance and nearly three times higher in Black patients than in White patients (odds ratio [OR], 2.97 and 2.83, respectively). In addition, older age was associated with increased risk of fibrosis, with an OR of 1.03 per year increase in age.

No differences in fibrosis at presentation occurred based on sex or median income, and no difference in the likelihood of fibrosis at presentation appeared between patients with Medicaid vs private insurance.

“We were surprised at the degree of risk associated with no insurance,” said Dr. Boron. The researchers also were surprised at the lack of association between higher risk of severe stage lung disease in sarcoidosis patients and zip code estimates of household income as an indicator of socioeconomic status, he said.

For clinical practice, the study findings highlight the potentially increased risk for fibrotic lung disease among patients who are older, uninsured, and African American, said Dr. Boron.

“A limitation of our study was the utilization of zip code based on the US Census Bureau to get an estimation of average household income — a particular limitation in our city because of gentrification over the past few decades,” Dr. Boron said in an interview. “Utilizing area deprivation indices could be a better marker for identifying household income and give a more accurate representation of the true impact of socioeconomic disparities and severity of sarcoidosis at presentation,” he said.

Pinpointing Persistent Disparities

“We know there are multiple sources of disparities in the sarcoidosis population,” said Rohit Gupta, MD, director of the sarcoidosis program at Temple University Hospital, Philadelphia, in an interview.

The current study identified the relationship between several socioeconomic factors and sarcoidosis severity, showing greater disease severity in people experiencing socioeconomic inequalities, said Dr. Gupta, who was not involved in the study.

“I have personally seen this [disparity] in clinic,” said Dr. Gupta. However, supporting data are limited, aside from recent studies published in the last few years by researchers at the Cleveland Clinic and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, he said. The current study reflects those previous findings that people suffering from inequality have worse medical care, he added.

Overall, the findings were not surprising, “as we know this cohort of patients have chronic disease and worse morbidity and, in some cases, higher mortality,” but the results reinforce the need to pay closer attention to socioeconomic factors, said Dr. Gupta.

In practice, “we might use these findings as a reminder that when we see these patients for the first time, we should pay closer attention because they might need higher care,” he said. “The study also suggests these patients are coming late to a center of excellence,” he noted. When patients with socioeconomic disparities are seen for sarcoidosis at community hospitals and small centers, providers should keep in mind that their disease might progress faster and, therefore, send them to advanced centers earlier, he said.

The study was limited to the use of data from a single center and by the retrospective design, Dr. Gupta said. “Additional research should focus on building better platforms to understand these disparities,” he emphasized, so clinicians can develop plans not only to identify inequalities but also to address them.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gupta had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Educational Tool Reduces Unnecessary Inhaler Use in ILD

Use of an electronic tool contributed to the deprescribing of unnecessary inhalers in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), based on data from nearly 200 individuals.

Patients with ILD often have symptoms that overlap with those of obstructive airways diseases, Stephanie Nevison, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues wrote in a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

, they noted.

“Our aim was twofold: To quantify the extent of inappropriate inhaler use in patients with ILD and to discontinue them where appropriate,” the researchers wrote.

“We hypothesized that inappropriate inhaler use in ILD is common and that an electronic initiative would improve deprescribing rates,” they said.

The researchers conducted a quality improvement project in an ILD clinic at a single center. They reviewed 5 months of baseline data for 191 patients with ILD to assess baseline frequency of inappropriate inhaler use, defined as one or more of the following criteria: Reported asthma history, smoking history of > 15 pack/years, emphysema on chest CT, patient-reported benefits from therapy, airflow obstruction, or bronchodilator response on spirometry.

A total of 48 patients (25.1%) were on inhalers, and 15 (7.8%) had no indication for them (9% of new referrals and 7% of follow-up patients). The most-prescribed inhalers for patients with no indication were corticosteroids (10 patients), short-acting beta-agonists (8 patients), and long-acting beta-agonists (7 patients).

None of the patients on inhalers received counseling about discontinuing their use. The results of the baseline assessment were shared with clinicians along with education about reducing unnecessary inhaler use in the form of a prompt linked to electronic medical records to discuss deprescription of unnecessary inhalers.

The electronic intervention was applied in 400 of 518 patient encounters, and the researchers reviewed data over another 5-month period. A total of 99 patients were on inhalers, and 3.3% had no indication (5.3% of new referrals and 3.0% of follow-up patients). In the wake of the intervention, “all patients on unnecessary inhalers were counseled on deprescribing, representing a significant increase compared to the preintervention period,” the researchers wrote.

Intervention Shows Potential to Curb Unnecessary Inhaler Use

More research is needed as the findings were limited by the relatively small sample size and use of data from a single center, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that electronic reminders are effective for prompting a review of inhaler use, and deprescribing inappropriate inhalers for patients with ILD could reduce the potential for adverse events associated with their use, they concluded.

The current study is important because some patients with ILD may not benefit from inhaler use, David Mannino, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said in an interview. In the study, “I was a bit surprised that only 3.3% of patients had no indication for them; this seems rather low,” said Dr. Mannino, who was not involved in the study.

Use of an electronic system that evaluates patients and flags inappropriate therapy is an effective way to decrease overprescribing of medications, Dr. Mannino told this news organization.

As for additional research, application of the tool used in this study to other pulmonary populations could be interesting and potentially useful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Mannino had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of an electronic tool contributed to the deprescribing of unnecessary inhalers in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), based on data from nearly 200 individuals.

Patients with ILD often have symptoms that overlap with those of obstructive airways diseases, Stephanie Nevison, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues wrote in a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

, they noted.

“Our aim was twofold: To quantify the extent of inappropriate inhaler use in patients with ILD and to discontinue them where appropriate,” the researchers wrote.

“We hypothesized that inappropriate inhaler use in ILD is common and that an electronic initiative would improve deprescribing rates,” they said.

The researchers conducted a quality improvement project in an ILD clinic at a single center. They reviewed 5 months of baseline data for 191 patients with ILD to assess baseline frequency of inappropriate inhaler use, defined as one or more of the following criteria: Reported asthma history, smoking history of > 15 pack/years, emphysema on chest CT, patient-reported benefits from therapy, airflow obstruction, or bronchodilator response on spirometry.

A total of 48 patients (25.1%) were on inhalers, and 15 (7.8%) had no indication for them (9% of new referrals and 7% of follow-up patients). The most-prescribed inhalers for patients with no indication were corticosteroids (10 patients), short-acting beta-agonists (8 patients), and long-acting beta-agonists (7 patients).

None of the patients on inhalers received counseling about discontinuing their use. The results of the baseline assessment were shared with clinicians along with education about reducing unnecessary inhaler use in the form of a prompt linked to electronic medical records to discuss deprescription of unnecessary inhalers.

The electronic intervention was applied in 400 of 518 patient encounters, and the researchers reviewed data over another 5-month period. A total of 99 patients were on inhalers, and 3.3% had no indication (5.3% of new referrals and 3.0% of follow-up patients). In the wake of the intervention, “all patients on unnecessary inhalers were counseled on deprescribing, representing a significant increase compared to the preintervention period,” the researchers wrote.

Intervention Shows Potential to Curb Unnecessary Inhaler Use

More research is needed as the findings were limited by the relatively small sample size and use of data from a single center, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that electronic reminders are effective for prompting a review of inhaler use, and deprescribing inappropriate inhalers for patients with ILD could reduce the potential for adverse events associated with their use, they concluded.

The current study is important because some patients with ILD may not benefit from inhaler use, David Mannino, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said in an interview. In the study, “I was a bit surprised that only 3.3% of patients had no indication for them; this seems rather low,” said Dr. Mannino, who was not involved in the study.

Use of an electronic system that evaluates patients and flags inappropriate therapy is an effective way to decrease overprescribing of medications, Dr. Mannino told this news organization.

As for additional research, application of the tool used in this study to other pulmonary populations could be interesting and potentially useful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Mannino had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Use of an electronic tool contributed to the deprescribing of unnecessary inhalers in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD), based on data from nearly 200 individuals.

Patients with ILD often have symptoms that overlap with those of obstructive airways diseases, Stephanie Nevison, MD, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues wrote in a study presented at the American Thoracic Society’s international conference.

, they noted.

“Our aim was twofold: To quantify the extent of inappropriate inhaler use in patients with ILD and to discontinue them where appropriate,” the researchers wrote.

“We hypothesized that inappropriate inhaler use in ILD is common and that an electronic initiative would improve deprescribing rates,” they said.

The researchers conducted a quality improvement project in an ILD clinic at a single center. They reviewed 5 months of baseline data for 191 patients with ILD to assess baseline frequency of inappropriate inhaler use, defined as one or more of the following criteria: Reported asthma history, smoking history of > 15 pack/years, emphysema on chest CT, patient-reported benefits from therapy, airflow obstruction, or bronchodilator response on spirometry.

A total of 48 patients (25.1%) were on inhalers, and 15 (7.8%) had no indication for them (9% of new referrals and 7% of follow-up patients). The most-prescribed inhalers for patients with no indication were corticosteroids (10 patients), short-acting beta-agonists (8 patients), and long-acting beta-agonists (7 patients).

None of the patients on inhalers received counseling about discontinuing their use. The results of the baseline assessment were shared with clinicians along with education about reducing unnecessary inhaler use in the form of a prompt linked to electronic medical records to discuss deprescription of unnecessary inhalers.

The electronic intervention was applied in 400 of 518 patient encounters, and the researchers reviewed data over another 5-month period. A total of 99 patients were on inhalers, and 3.3% had no indication (5.3% of new referrals and 3.0% of follow-up patients). In the wake of the intervention, “all patients on unnecessary inhalers were counseled on deprescribing, representing a significant increase compared to the preintervention period,” the researchers wrote.

Intervention Shows Potential to Curb Unnecessary Inhaler Use

More research is needed as the findings were limited by the relatively small sample size and use of data from a single center, the researchers noted.

However, the results suggest that electronic reminders are effective for prompting a review of inhaler use, and deprescribing inappropriate inhalers for patients with ILD could reduce the potential for adverse events associated with their use, they concluded.

The current study is important because some patients with ILD may not benefit from inhaler use, David Mannino, MD, of the University of Kentucky, Lexington, said in an interview. In the study, “I was a bit surprised that only 3.3% of patients had no indication for them; this seems rather low,” said Dr. Mannino, who was not involved in the study.

Use of an electronic system that evaluates patients and flags inappropriate therapy is an effective way to decrease overprescribing of medications, Dr. Mannino told this news organization.

As for additional research, application of the tool used in this study to other pulmonary populations could be interesting and potentially useful, he said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers and Dr. Mannino had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ATS 2024

Use of Hypoglossal Nerve Stimulation for Treating OSA in Military Patient Populations

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the repetitive collapse of posterior oropharynx during sleep resulting in hypoxia and/or arousals from sleep, is the most common form of sleep disordered breathing and a common chronic respiratory disorders among middle-aged adults. OSA can lead to significant health problems, such as worsened cardiometabolic disease and cognitive impairment, which can increase morbidity and mortality.1

The gold standard for OSA diagnosis is polysomnography (PSG), although home sleep studies can be performed for select patients. OSA diagnoses are based on the number of times per hour of sleep a patient’s airway narrows or collapses, reducing or stopping airflow, scored as hypopnea or apnea events, respectively. An Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) score of 5 to 14 events/hour is considered mild OSA, 15 to 30 events/hour moderate OSA, and ≥ 30 events/hour severe OSA.2

Treatment commonly includes positive airway pressure (PAP) but more than one-half of patients are not adherent to continuous PAP (CPAP) treatment after about 90 days.3 Efficacy of treatments vary as a function of disease severity and etiology, which—in addition to the classic presentation of obesity with large neck/narrowupper airway—includes craniofacial abnormalities, altered muscle function in the upper airway, pharyngeal neuropathy, and fluid shifts to the neck.

Background

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) estimates that 10% to 17% of adults in the United States have OSA.4 Compared with civilians, the military population generally is younger and healthier. Service members have access to regular health care with yearly physical examinations, exercise scheduled into the workday, and mandatory height/weight and fitness standards. Because obesity is a major risk factor for OSA, and the incidence of obesity is relatively low in the military population (estimated at 18.8% in 2021 vs 39.8% among all US adults aged 20 to 39 years), it might be expected that incidence of OSA would be correspondingly low.5,6 However, there is evidence of a rapidly increasing incidence of OSA in military populations. A 2021 study revealed that OSA incidence rates increased from 11 to 333 per 10,000 between 2005 and 2019 across all military branches and demographics, with the highest rate among Army personnel.7 An earlier study revealed a 600% increase in OSA incidence among Army personnel between 2003 and 2011.8

Several factors likely contributed to this increase, including expanding obesity and greater physician awareness and availability of sleep study centers. Rogers and colleagues found that 40% to 50% of incident OSA diagnoses among military personnel occur within 12 months of separation, suggesting that the secondary gains associated with military disability benefits might motivate OSA evaluation.9 It is possible that secondary gain is a factor because an OSA diagnosis can range from a 0% to 100% disability rating, depending on the severity.10 This disability claim is based on evidence that untreated OSA can negatively affect long-term health and mission readiness.8 For example, untreated OSA can lead to hypertension, which contributes to a long list of adverse health and wellness consequences. Most importantly for the military, OSA has been shown to increase daytime sleepiness and reduce cognitive performance.10

The current first-line treatment for OSA is CPAP, which improves symptoms of daytime sleepiness, hypertension management, and daytime alertness.11 Despite its efficacy, nonadherence rates range from 29% to 83%.12-15 Nonadherence factors include lifestyle changes, adverse effects (eg, nasal congestion), and lack of education on proper use.11 Lifestyle changes needed to increase the likelihood of successful therapy, such as regular sleep schedules and proper CPAP cleaning and maintenance, are difficult for military personnel because of the nature of continuous or sustained operations that might require shift work and/or around-the-clock (ie, 24-hour, 7 days a week) task performance. Traveling with CPAP is an added burden for service members deployed to combat operations (ie, added luggage, weight, maintenance). Although alternate treatments such as oral appliances (ie, custom dental devices) are available, they generally are less effective than CPAP.2 Oral appliances could be a reasonable alternative treatment for some patients who cannot manage their OSA with behavioral modifications and are intolerant or unable to effectively use CPAP. This could include patients in the military who are deployed to austere environments.

Surgically implanted hypoglossal nerve stimulator (HGNS) treatment may provide long-term health benefits to service members. After the device is implanted near the hypoglossal nerve, electrical stimulation causes the tongue to move forward, which opens the airway in the anteroposterior dimension. The most important consideration is the mechanism of airway collapse. HGNS is not effective for patients whose OSA events are caused by circumferential collapse of other airway muscles. The cause of airway collapse is ascertained before surgery with drug-induced sleep endoscopy, a procedure that allows visualization of conformational changes in the upper airway during OSA events.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved HGNS in 2014. However, it is not considered a first-line treatment for OSA by the AASM. Original candidate criteria for HGNS included an AHI score of 15 to 65 events/hour, age ≥ 18 years, failed CPAP use, body mass index (BMI) < 32, absence of palatal complete concentric collapse, and central apneas comprising < 25% of total events.16 In June 2023, the FDA expanded approval to increase the upper limit of AHI to 100 events/hour and the BMI to < 40.17

HGNS has been reported to be effective in appropriately selected patients with OSA at tertiary care centers with established multidisciplinary sleep surgical programs. These benefits have not been confirmed in larger, community-based settings, where most of these surgeries occur. In community practice, there is significant confusion among patients and clinicians about the optimal pathway for patient selection and clinical follow-up. Many patients view HGNS as a viable alternative to CPAP, but initially do not understand that it requires surgery. Surgical treatments for OSA, such as HGNS, are appealing because they suggest a 1-time intervention that permanently treats the condition, without need for follow-up or equipment resupply. HGNS might be an appealing treatment option because it is less obtrusive than CPAP and requires fewer resources for set-up and maintenance. Also, it does not cause skin irritation (a possible adverse effect of nightly use of a CPAP mask), allows the individual to sleep in a variety of positions, has less impact on social and sex life, and does not require an electric outlet. In the long term, HGNS might be more cost effective because there is no yearly physician follow-up or equipment resupply and/or maintenance.

The military population has specific demands that impact delivery and effectiveness of health care. Among service members with OSA, CPAP treatment can be challenging because of low adherence, required annual follow-up despite frequent moving cycles that pose a challenge for care continuity, and duty limitations for affected service members (ie, the requirement for a waiver to deploy and potential medical separation if symptoms are not adequately controlled). As the incidence of OSA continues to increase among service members, so does the need for OSA treatment options that are efficacious as CPAP but better tolerated and more suitable for use during military operations. The aim of this review is to assess the effectiveness of HGNS and its potential use by the military OSA patient population.

METHODS

To identify eligible studies, we employed PICOS: Population (patients aged ≥ 18 years with a history of OSA), Intervention (HGNS), Comparator (standard of care PAP therapy), Outcome (AHI or Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS], and Study (randomized control trial [RCT] or clinical trial). Studies were excluded if they were not written in English or included pediatric populations. The ESS is a subjective rating scale used to determine and quantify a patient’s level of daytime sleepiness, using a 4-point scale for the likelihood of falling asleep totaled across 8 different situations.18 Daytime sleepiness is considered lower normal(0-5 points), higher normal (6-10 points), mild or moderate excessive (11-15 points), and severe excessive (16-24 points).

Literature Search

We conducted a review of PubMed and Scopus for RCTs and controlled trials published from 2013 to 2023 that included the keywords and phrases: obstructive sleep apnea and either hypoglossal nerve stimulation or upper airway stimulation. The final literature search was performed December 8, 2023.

Two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of studies identified in the literature search based on the predefined inclusion criteria. If it was not clear whether an article met inclusion criteria based on its title and/or abstract, the 2 review authors assessed the full text of study and resolved any disagreement through consensus. If consensus was not obtained, a third author was consulted. No duplicates were identified. The PRISMA study selection process is presented in the Figure.

Data extraction was performed by 1 independent reviewer. A second author reviewed the extracted data. Any identified discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. If consensus was not obtained, a third author was consulted. Study data included methods (study design and study objective), participants mean age, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, interventions and comparators, and primary study outcomes.

The quality of evidence was assessed using a rating of 1 to 5 based on a modified version of the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine Levels of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation.19 A rating of 1 indicated a properly powered and conducted RCT, 2 demonstrated a well-designed controlled trial without randomization or prospective comparative cohort trial, 3 designated a case-control study or retrospective cohort study, 4 signified a case series with or without intervention or a cross-sectional study, and 5 denoted an opinion of respected authorities or case reports. Two reviewers independently evaluated the quality of evidence. Any identified discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. If consensus was not obtained, a third review author was consulted.

RESULTS

We identified 30 studies; 19 articles did not meet inclusion criteria. The remaining 11 articles were divided into 4 cohorts. Five articles were based on data from the STAR trial, a multicenter study that included adults with moderate-to-severe OSA and inadequate adherence to CPAP.20-24 Four articles used the same patient selection criteria as the STAR trial for a long-term German postmarket study of upper airway stimulation efficacy with OSA.25-28 The third and fourth cohorts each consist of 31 patients with moderate-to-severe OSA with CPAP nonadherence or failure.29,30 The STAR trial included follow-up at 5 years, and the German-postmarket had a follow-up at3 years. The remaining 2 cohorts have 1-year follow-ups.

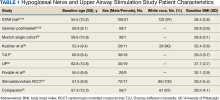

The Scopus review identified 304 studies; 299 did not meet inclusion criteria and 1 was part of the STAR trial.31 The remaining 4 articles were classified as distinct cohorts. Huntley and colleagues included patients from Thomas Jefferson University (TJU) and University of Pittsburgh (UP) academic medical centers.32 The Pordzik and colleagues cohort received implantation at a tertiary medical center, an RCCT, and a 1:1 comparator trial (Table 1).33-35

STAR Trial

This multicenter, prospective, single-group cohort study was conducted in the US, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, and France. The STAR trial included 126 patients who were not CPAP therapy adherent. Patients were excluded if they had AHI < 20 or > 50, central sleep apnea > 25% of total AHI, anatomical abnormalities that prevent effective assessment of upper-airway stimulation, complete concentric collapse of the retropalatal airway during drug-induced sleep, neuromuscular disease, hypoglossal-nerve palsy, severe restrictive or obstructive pulmonary disease, moderate-to-severe pulmonary arterial hypertension, severe valvular heart disease, New York Heart Association class III or IV heart failure, recent myocardial infarction or severe cardiac arrhythmias (within the past 6 months), persistent uncontrolled hypertension despite medication use, active psychiatric illness, or coexisting nonrespiratory sleep disorders that would confound functional sleep assessment. Primary outcome measures included the AHI and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) with secondary outcomes using the ESS, the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), and the percentage of sleep time with oxygen saturation < 90%. Of 126 patients who received implantation, 71 underwent an overnight PSG evaluation at 5-year follow-up. Mean (SD) AHI at baseline was reduced with HGNS treatment to from 32.0 (11.8) to 12.4 (16.3). Mean (SD) ESS for 92 participants with 2 measurements declined from 11.6 (5.0) at baseline to 6.9 (4.7) at 5-year follow-up.

The STAR trial included a randomized controlled withdrawal study for 46 patients who had a positive response to therapy to evaluate efficacy and durability of upper airway stimulation. Patients were randomly assigned to therapy maintenance or therapy withdrawal groups for ≥ 1 week. The short-term withdrawal effect was assessed using the original trial outcome measures and indicated that both the withdrawal and maintenance groups showed improvements at 12 months compared with the baseline. However, after the randomized withdrawal, the withdrawal group’s outcome measures deteriorated to baseline levels while the maintenance group showed no change. At 18 months of therapy, outcome measures for both groups were similar to those observed with therapy at 12 months.24 The STAR trial included self-reported outcomes at baseline, 12 months, and 24 months that used ESS to measure daytime sleepiness. These results included subsequent STAR trial reports.20-24,31

The German Postmarket Cohort

This multicenter, prospective, single-arm study used selection criteria that were based on those used in the STAR trial and included patients with moderate-to-severe OSA and nonadherence to CPAP. Patients were excluded if they had a BMI > 35, AHI < 15 or > 65; central apnea index > 25% of total AHI; or complete concentric collapse at the velopharynx during drug-induced sleep. Measured outcomes included AHI, ODI, FOSQ, and ESS. Among the 60 participants, 38 received implantation and a 3-year follow-up. Mean (SD) AHI decreased from 31.2 (13.2) at baseline to 13.1 (14.1) at follow-up, while mean (SD) ESS decreased from 12.8 (5.3) at baseline to 6.0 (3.2) at follow-up.25-28

Munich Cohort

This single-center, prospective clinical trial included patients with AHI > 15 and < 65, central apnea index < 25% of total AHI, and nonadherence to CPAP. Patients were excluded if they had a BMI > 35, anatomical abnormalities that would prevent effective assessment of upper-airway stimulation; all other exclusion criteria matched those used in the STAR trial. Among 31 patients who received implants and completed a 1-year follow-up, mean (SD) AHI decreased from 32.9 (11.2) at baseline to 7.1 (5.9) at follow-up and mean (SD) ESS decreased from 12.6 (5.6) at baseline to 5.9 (5.2) at follow-up.29

Kezirian and Colleagues Cohort

This prospective, single-arm, open-label study was conducted at 4 Australian and 4 US sites. Selection criteria included moderate-to-severe OSA with failure of CPAP, AHI of 20 to 100 with ≥ 15 events/hour occurring in sleep that was non-REM (rapid eye movement) sleep, BMI ≤ 40 (Australia) or ≤ 37 (US), and a predominance of hypopneas (≥ 80% of disordered breathing events during sleep). Patients were excluded if they had earlier upper airway surgery, markedly enlarged tonsils, uncontrolled nasal obstruction, severe retrognathia, > 5% central or mixed apneic events, incompletely treated sleep disorders other than OSA, or a major disorder of the pulmonary, cardiac, renal, or nervous systems. Data were reported for 31 patients whose mean (SD) AHI declined from 45.4 (17.5) at baseline to 25.3 (20.6) at 1-year follow-up and mean (SD) ESS score declined from 12.1 (4.6) at baseline to 7.9 (3.8) 1 year later.30

TJU and UP Cohorts

The TJU and UP cohorts are composed of patients who underwent implantation between May 2014 and August 2016 at 2 academic centers.31,32 Selection criteria was consistent with that used in the STAR trial, and patients completed postoperative titration PSG and outpatient follow-up (48 patients at TJU and 49 at UP). Primary outcomes included AHI, ESS, and O2 nadir. Secondary outcomes consisted of surgical success and percentage of patients tolerating optimal titration setting at follow-up. Postoperative outcomes were assessed during the titration PSG. Time from initial ESS to postoperative PSG at TJU was 1.7 years and at UP was 1.9 years. Time from initial AHI to postoperative PSG at TJU was 90.4 days and 85.2 days at UP. At TJU, mean (SD) AHI and ESS dropped from 35.9 (20.8) and 11.1 (3.8), respectively at baseline to 6.3 (11.5) and 5.8 (3.4), respectively at follow-up. At UP, mean (SD) AHI and ESS fell from 35.3 (15.3) and 10.9 (4.9), respectively at baseline to 6.3 (6.1) and 6.6 (4.5), respectively at follow-up. There were no site-related differences in rates of AHI, ESS, or surgical success.31

Pordzik and Colleagues Cohort

This cohort of 29 patients underwent implantation between February 2020 and June 2022 at a tertiary university medical center with both pre- and postoperative PSG. Selection criteria was consistent with that of the German postmarket cohort. Postoperative PSG was completed a mean (SD) 96.3 (27.0) days after device activation. Mean (SD) AHI dropped from 38.6 (12.7) preoperatively to 24.4 (13.3) postoperatively. Notably, this cohort showed a much lower decrease of postoperative AHI than reported by the STAR trial and UP/TJU cohort.33

Stimulation vs Sham Trial

This multicenter, double-blinded, randomized, crossover trial assessed the effect of HGNS (stim) vs sham stimulation (sham) in 86 patients that completed both phases of the trial. Primary outcomes included AHI and ESS. Secondary outcomes included FOSQ. No carryover effect was found during the crossover phase. The difference between the phases was−15.5 (95% CI, −18.3 to −12.8) for AHI and −3.3 (95% CI, −4.4 to −2.2) for ESS.34

Comparator

The comparator study used propensity score matching to compare outcomes of HGNS and PAP therapy. Primary outcomes included sleepiness, AHI, and effectiveness with outcome measures of AHI and ESS collected at baseline and 12 months postimplantation. The article reported that 126 of 227 patients were matched 1:1. Both groups showed improvement in AHI and ESS. Mean (SD) AHI for the HGNS group at baseline started at 33.9 (15.1) and decreased to 8.1 (6.3). Mean (SD) ESS for the HGNS group at baseline was 15.4 (3.5) and decreased to 7.5 (4.7). In the PAP comparator group, mean (SD) baseline AHI was 36.8 (21.6) and at follow-up was 6.6 (8.0) and mean (SD) ESS was 14.6 (3.9) at baseline and 10.8 (5.6) at follow-up.35

DISCUSSION

The current clinical data on HGNS suggest that this treatment is effective in adults with moderate-to-severe OSA and effects are sustained at long-term follow-up, as measured by AHI reduction and improvements in sleep related symptoms and quality of life (Table 2). These results have been consistent across several sites.

The STAR trial included a randomized control withdrawal group, for whom HGNS treatment was withdrawn after the 12-month follow-up, and then restored at 18 months.21 This revealed that withdrawal of HGNS treatment resulted in deterioration of both objective and subjective measures of OSA and sleepiness. The beneficial effects of HGNS were restored when treatment was resumed.24 Additionally, the RCCT revealed that therapeutic stimulation via HGNS significantly reduced subjective and objective measures of OSA.34 These studies provide definitive evidence of HGNS efficacy.

Currently, a diagnosis of OSA on PAP is classified as a 50% military disability rating. This rating is based primarily on epidemiologic evidence that untreated OSA is a costly disease that leads to other chronic illnesses that increases health care utilization.9 HGNS requires an initially invasive procedure and higher upfront costs, but it could result in reduced health care use and long-term costs because of improved adherence to treatment—compared with CPAP—that results in better outcomes.

Limitations to OSA Studies

The reviewed studies have several limitations that warrant caution when determining the possible benefits of HGNS treatment. The primary limitation is the lack of active control groups, therefore precluding a direct comparison of the short- and long-term effectiveness of HGNS vs other treatments (eg, CPAP). This is especially problematic because in the reviewed studies HGNS treatment efficacy is reported as a function of the mean—and SD—percent reduction in the AHI, whereas the efficacy of CPAP treatment usually is defined in terms of “adequacy of titration” as suggested by the AASM.36 It has been reported that with CPAP treatment, 50% to 60% of OSA patients achieve AASM-defined optimal improvement of respiratory disturbance index of < 5/hour during a polysomnographic sleep recording of ≥ 15 minutes duration that includes REM sleep in the supine position.37 In most of the reviewed studies, treatment success was more liberally defined as a decrease of AHI by ≥ 50%, regardless of the resulting AHI. It is notable that among the reviewed HGNS studies, the TJU and UP cohorts achieved the best outcome in short-term follow-up of 2 months with a mean (SD) AHI of 6.3 (11.5) and 6.4 (6.1), respectively. Among those cohortsassessed at a 12-month follow-up, the Munich cohort achieved the best outcome with a mean (SD) AHI of 7.1 (5.9).

Although the metrics reported in the reviewed studies are not directly comparable, the reported findings strongly suggest that HGNS generally is less effective than CPAP. How important are these differences? With findings that HGNS “reliably produces clinically meaningful (positive) effects on daytime sleepiness, daytime functioning, and sleep quality,” does it really matter if the outcome metrics for HGNS are a little less positive than those produced by CPAP?38 For individual military OSA patients the answer is yes. This is because in military operational environments—especially during deployment—sleep restriction is nearly ubiquitous, therefore any mild residual deficits in sleep quality and daytime alertness resulting from nominally adequate, but suboptimal OSA treatment, could be exacerbated by sleep restriction, therefore placing the service member and the mission at increased risk.39

Another limitation is the narrow inclusion criteria these studies employed, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Participants in the reviewed clinical trials were selected from a patient population that was mostly middle-aged, White, and obese or overweight. In a Medical Surveillance Monthly Report study, OSA was found to be highest among service members aged > 40 years, male, obese, and Black/non-Hispanic (although it should be noted that more than one-half of enlisted service members aged ≤ 25 years).40,41 Obesity has been noted as a growing concern for the military as the military population is beginning to mirror the civilian population in terms of being overweight or obese despite height and weight standards. HGNS might not be as successful in military populations with different demographics. Moreover, HGNS has been shown to have greater AHI reduction among those with higher BMI.30 Although obese service members have a 6-fold higher 12-year incidence rate of OSA than service members without obesity, this nevertheless suggests that general level of HGNS efficacy might be lower among the military patient population, because obesity is less prevalent in the military than the general population.9

Ethnicity has been found to be a relevant factor, with the highest incidence rate of OSA among non-Hispanic Black males, a demographic that was underrepresented in cohorts included in this review. Further studies will be needed to determine the extent to which findings from HGNS treatment studies are generalizable to the broader OSA patient population.

HGNS Implementation Challenges

Current impediments to widespread use of HGNS as an OSA treatment include no standardized guidance for titration and follow-on care, which varies based on the resources available. Titrating a new device for HGNS requires experienced sleep technicians who have close relationships with device representatives and can troubleshoot problems. Technical expertise, which currently is rare, is required if there are complications after placement or if adjustments to voltage settings are needed over time. In addition, patients may require multiple specialists making it easy to get lost to follow-up after implantation. This is particularly challenging in a transient community, such as the military, because there is no guarantee that a service member will have access to the same specialty care at the next duty station.

Although some evidence suggests that HGNS is a viable alternative treatment for some patients with OSA, the generalizability of these findings to the military patient population is unclear. Specialized facilities and expertise are needed for the surgical procedure and follow-up requirements, which currently constitute significant logistical constraints. As with any implantable device, there is a risk of complications including infection that could result in medical evacuation from a theater of operations. If the device malfunctions or loses effectiveness in a deployed environment, the service member might not have immediate access to medical support, potentially leading to undertreatment of OSA. In future battlefield scenarios in multidomain operations, prolonged, far-forward field care will become the new normal because the military is not expected to have air superiority or the ability to quickly evacuate service members to a higher level of medical care.42