User login

Depressed and awkward: Is it more than that?

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

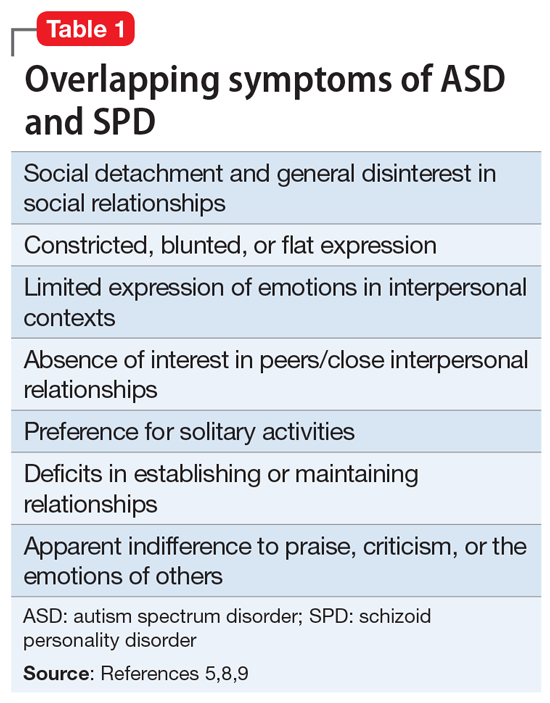

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

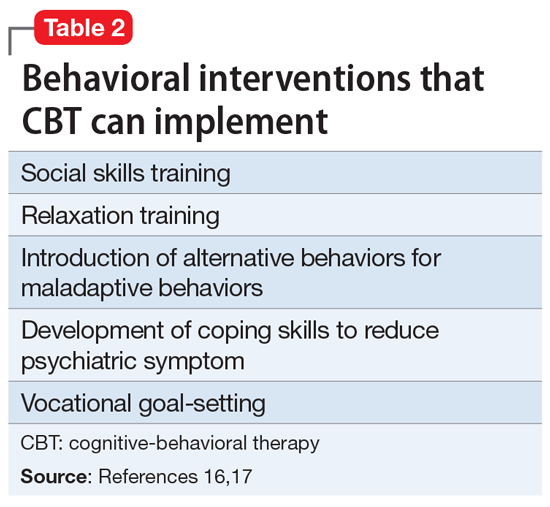

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

1. Fariba K, Gupta V. Schizoid personality disorder. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559234/

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed rev. American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

3. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(4):515-528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8

4. Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid personality disorder: a review of current status and implications for DSM-IV. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7(1), 43-52.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

7. Vatano

8. Ritsner MS. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances. Springer; 2011.

9. Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. On the continuity between autistic and schizoid personality disorder trait burden: a prospective study in adolescence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(2):94-100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

10. Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013-1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

11. Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, et al. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;10.1007/s00406-020-01189-2. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

12. Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

13. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, et al. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2389-2402. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

14. Giarelli E, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, et al. Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):107-116. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

15. Frazier TW, Georgiades S, Bishop SL, et al. Behavioral and cognitive characteristics of females and males with autism in the Simons Simplex Collection. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):329-40.e403. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.004

16. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA Jr, et al. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

17. Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;9, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019

18. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):687-694. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

CASE Treatment-resistant MDD

Ms. P, age 21, presents to the outpatient clinic. She has diagnoses of treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD) and schizoid personality disorder (SPD). Ms. P was diagnosed with MDD 3 years ago after reporting symptoms of prevailing sadness for approximately 8 years, described as feelings of worthlessness, anhedonia, social withdrawal, and decreased hygiene and self-care behaviors, as well as suicidal ideation and self-harm. SPD was diagnosed 1 year earlier based on her “odd” behaviors and disheveled appearance following observation and in collateral with her family. Her odd behaviors are described as spending most of her time alone, preferring solitary activities, and having little contact with people other than her parents.

Ms. P reports that she was previously treated with citalopram, 20 mg/d, bupropion, 150 mg/d, aripiprazole, 3.75 mg/d, topiramate, 100 mg twice daily, and melatonin, 9 mg/d at bedtime, but discontinued follow-up appointments and medications after no significant improvement in symptoms.

[polldaddy:11027942]

The authors’ observations

The term “schizoid” first made its debut in the medical community to describe the prodromal social withdrawal and isolation observed in schizophrenia.1 The use of schizoid to describe a personality type first occurred in DSM-III in 1980.2 SPD is a Cluster A personality disorder that groups personalities characterized by common traits that are “odd” or “eccentric” and may resemble the positive and/or negative symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Relatively uncommon in clinical settings, SPD includes individuals who do not desire or enjoy close relationships. Those afflicted with SPD will be described as isolated, aloof, and detached from social relationships with others, even immediate family members. Individuals with SPD may appear indifferent to criticism and praise, and may take pleasure in only a few activities. They may exhibit a general absence of affective range, which contributes to their characterization as flat, blunted, or emotionally vacant. SPD is more commonly diagnosed in males and may be present in childhood and adolescence. These children are typified by solitariness, poor peer relationships, and underachievement in school. SPD impacts 3.1% to 4.9% of the United States population and approximately 1% of community populations.5,6

EVALUATION Persistent depressive symptoms

Ms. P is accompanied by her parents for the examination. She reports a chronic, persistent sad mood, hopelessness, anergia, insomnia, anhedonia, and decreased concentration and appetite. She says she experiences episodes of intense worry, along with tension, restlessness, feelings of being on the edge, irritability, and difficulty relaxing. Socially, she is withdrawn, preferring to stay alone in her room most of the day watching YouTube or trying to write stories. She has 2 friends with whom she does not interact with in person, but rather through digital means. Ms. P has never enjoyed attending school and feels “nervous” when she is around people. She has difficulty expressing her thoughts and often looks to her parents for help. Her parents add that getting Ms. P to attend school was a struggle, which resulted in periods of home schooling throughout high school.

The treating team prescribes citalopram, 10 mg/d, and aripiprazole, 2 mg/d. On subsequent follow-up visits, Ms. P’s depression improves with an increase in citalopram to 40 mg/d. Psychotherapy is added to her treatment plan to help address the persistent social deficits, odd behavior, and anxieties.

Continue to: Evaluation Psychological assessment...

EVALUATION Psychological assessment

At her psychotherapy intake appointment with the clinical neuropsychologist, Ms. P is dressed in purple from head to toe and sits clutching her purse and looking at the ground. She is overweight with clean, fitting clothing. Ms. P takes a secondary role during most of the interview, allowing her parents to answer most questions. When asked why she is starting therapy, Ms. P replies, “Well, I’ve been using the bathroom a lot.” She describes a feeling of comfort and calmness while in the restroom. Suddenly, she asks her parents to exit the exam room for a moment. Once they leave, she leans in and whispers, “Have you ever heard of self-sabotage? I think that’s what I’m doing.”

Her mood is euthymic, with a blunted affect. She scores 2 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and 10 on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7), which indicates the positive impact of medication on her depressive symptoms but continuing moderate anxious distress. She endorses fear of the night, insomnia, and suicidal ideation. She reports an unusual “constant itching sensation,” resulting in hours of repetitive excoriation. Physical examination reveals several significant scars and scabs covering her bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her vocational history is brief; she had held 2 entry-level customer service positions that lasted <1 year. She was fired due to excessive bathroom use.

As the interview progresses, the intake clinician’s background in neuropsychological assessment facilitates screening for possible developmental disorders. Given the nature of the referral and psychotherapy intake, a full neuropsychological assessment is not conducted. The clinician emphasizes verbal abstraction and theory of mind. Ms. P’s IQ was estimated to be average by Wide Range Achievement Test 4 word reading and interview questions about her academic history. Questions are abstracted from the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Module 4, to assess for conversation ability, emotional insight, awareness and expression, relationships, and areas of functioning in daily living. Developmental history questions, such as those found on the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System, 3rd edition, help guide developmental information provided by parents in the areas of communication, emotion and eye-gaze, gestures, sensory function, language, social functioning, hygiene behavior, and specific interests.

Ms. P’s mother describes a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, she states that Ms. P was “born with problems,” including difficulty with rooting and sucking, and required gastrointestinal intubation until age 3. Cyclical vomiting followed normal food consumption. Ambulation, language acquisition, toilet training, and hygiene behavior were delayed. Ms. P experienced improvements with early intervention in intensive physical and occupational therapy.

Ms. P’s hygiene is well below average, and she requires cueing from her parents. She attended general education until she reached high school, when she began special education. She was sensitive to sensory stimulation from infancy, with sensory sensitivity to textures. Ms. P continues to report sensory sensitivity and lapses in hygiene.

She has difficulty establishing and maintaining relationships with her peers, and prefers solitary activities. Ms. P has no history of romantic relationships, although she does desire one. When asked about her understanding of various relationships, Ms. P’s responses are stereotyped, such as “I know someone is my friend because they are nice to me” and “People get married because they love each other.” She struggles to offer greater insight into the nuances that form lasting relationships and bonds. Ms. P struggles to imitate and describe the physical and internal cues of several basic emotions (eg, fear, joy, anger).

Her conversational and social skills are assessed by asking her to engage in a conversation with the examiner as if meeting for the first time. Her speech is reciprocal, aprosodic, and delayed. The conversation is one-sided, and the examiner fills in several awkward pauses. Ms. P’s gaze at times is intense and prolonged, especially when responding to questions. She tends to use descriptive statements (eg, “I like your purple pen, I like your shirt”) to engage in conversation, rather than gathering more information through reflective statements, questions, or expressing a shared interest.

Ms. P’s verbal abstraction is screened using questions from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition Similarities subtest, to which she provides several responses within normal limits. Her understanding of colloquial speech is assessed by asking her the meaning of common phrases (eg, “Get knocked down 9 times, get up 10,” “Jack and Jill are 2 peas in a pod”). On many occasions, she is able to limit her response to 1 word, (eg, “resiliency”), demonstrating intact ability to decipher idioms.

[polldaddy:11027971]

The authors’ observations

Upon reflection of Ms. P’s clinical presentation and history of developmental delays, social deficits, sensory sensitivity since infancy, and repetitive behaviors (all which continue to impact her), the clinical team concluded that the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) helps explain the patient’s “odd” behaviors, more so than SPD.

ASD is a heterogenous, complex neuropsychiatric disorder characterized by a persistent deficit in social reciprocity, verbal, and nonverbal communication, and includes a pattern of restricted, repetitive and/or stereotyped behaviors and/or interests.5 The term “autismus” is Greek meaning “self,” and was first used to classify the qualities of “morbid self-admiration” observed in prodromal schizophrenia.7

To properly distinguish these disorders, keep in mind that patients with ASD have repetitive and restricted patterns of behaviors or interests that are not found in SPD, and experience deficits in forming, maintaining, and understanding relationships since they lack those skills, while patients with SPD are more prone to desire solitary activities and limited relationships.5,9

There has been an increased interest in determining why for some patients the diagnosis of ASD is delayed until they reach adulthood. Limited or no access to the patient’s childhood caregiver to obtain a developmental history, as well as generational differences on what constitutes typical childhood behavior, could contribute to a delayed diagnosis of ASD until adulthood. Some patients develop camouflaging strategies that allow them to navigate social expectations to a limited degree, such as learning stock phrases, imitating gestures, and telling anecdotes. Another factor to consider is that co-occurring psychiatric disorders may take center stage when patients present for mental health services.10 Fusar-Poli et al11 investigated the characteristics of patients who received a diagnosis of ASD in adulthood. They found that the median time from the initial clinical evaluation to diagnosis of ASD in adulthood was 11 years. In adults identified with ASD, their cognitive abilities ranged from average to above average, and they required less support. Additionally, they also had higher rates of being previously diagnosed with psychotic disorders and personality disorders.11

It is important to keep in mind that the wide spectrum of autism as currently defined by DSM-5 and its overlap of symptoms with other psychiatric disorders can make the diagnosis challenging for both child and adolescent psychiatrists and adult psychiatrists and might help explain why severe cases of ASD are more readily identified earlier than milder cases of ASD.10

Ms. P’s case is also an example of how women are more likely than men to be overlooked when evaluated for ASD. According to DSM-5, the estimated gender ratio for ASD is believed to be 4:1 (male:female).5 However, upon systematic review and meta-analysis, Loomes et al12 found that the gender ratio may be closer to 3:1 (male:female). These authors suggested that diagnostic bias and a failure of passive case ascertainment to estimate gender ratios as stated by DSM-5 in identifying ASD might explain the lower gender ratio.12 A growing body of evidence suggests that ASD is different in males and females. A 2019 qualitative study by Milner et al13 found that female participants reported using masking and camouflaging strategies to appear neurotypical. Compensatory behaviors were found to be linked to a delay in diagnosis and support for ASD.13

Cognitive ability as measured by IQ has also been found to be a factor in receiving a diagnosis of ASD. In a 2010 secondary analysis of a population-based study of the prevalence of ASD, Giarelli et al14found that girls with cognitive impairments as measured by IQ were less likely to be diagnosed with ASD than boys with cognitive impairment, despite meeting the criteria for ASD. Females tend to exhibit fewer repetitive behaviors than males, and tend to be more likely to show accompanying intellectual disability, which suggests that females with ASD may go unrecognized when they exhibit average intelligence with less impairment of behavior and subtler manifestation of social and communication deficits.15 Consequently, females tend to receive this diagnosis later than males.

Continue to: Treatment...

TREATMENT Adding CBT

At an interdisciplinary session several weeks later that includes Ms. P and her parents, the treatment team discusses the revised diagnoses of ASD and MDD, a treatment recommendation for cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and continued use of medication. At this session, Ms. P discloses that she has not been consistent with her medication regimen since her last appointment, which helps explain the increase in her PHQ-9 score from 2 to 14 and GAD-7 score

[polldaddy:11027990]

The authors’ observations

CBT can be helpful in improving medication adherence, developing coping skills, and modifying maladaptive behaviors.

OUTCOME Improvement with psychotherapy

Ms. P and family agree with the team’s recommendations. The aims of Ms. P’s psychotherapy are to maintain medication compliance; implement behavioral modification, vocational rehabilitation, and community engagement; develop social skills; increase functional independence; and develop coping skills for depression and anxiety.

Bottom Line

The prevalence of schizoid personality disorder (SPD) is low, and its symptoms overlap with those of autism spectrum disorder. Therefore, before diagnosing SPD in an adult patient, it is important to obtain a detailed developmental history and include an interdisciplinary team to assess for autism spectrum disorder.

1. Fariba K, Gupta V. Schizoid personality disorder. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559234/

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed rev. American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

3. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(4):515-528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8

4. Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid personality disorder: a review of current status and implications for DSM-IV. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7(1), 43-52.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

7. Vatano

8. Ritsner MS. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances. Springer; 2011.

9. Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. On the continuity between autistic and schizoid personality disorder trait burden: a prospective study in adolescence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(2):94-100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

10. Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013-1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

11. Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, et al. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;10.1007/s00406-020-01189-2. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

12. Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

13. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, et al. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2389-2402. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

14. Giarelli E, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, et al. Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):107-116. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

15. Frazier TW, Georgiades S, Bishop SL, et al. Behavioral and cognitive characteristics of females and males with autism in the Simons Simplex Collection. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):329-40.e403. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.004

16. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA Jr, et al. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

17. Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;9, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019

18. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):687-694. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8

1. Fariba K, Gupta V. Schizoid personality disorder. StatPearls Publishing. Updated June 9, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559234/

2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III. 3rd ed rev. American Psychiatric Association; 1987.

3. Esterberg ML, Goulding SM, Walker EF. Cluster A personality disorders: schizotypal, schizoid and paranoid personality disorders in childhood and adolescence. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010;32(4):515-528. doi:10.1007/s10862-010-9183-8

4. Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid personality disorder: a review of current status and implications for DSM-IV. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7(1), 43-52.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Eaton NR, Greene AL. Personality disorders: community prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;21:28-32. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.001

7. Vatano

8. Ritsner MS. Handbook of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, Volume I: Conceptual Issues and Neurobiological Advances. Springer; 2011.

9. Cook ML, Zhang Y, Constantino JN. On the continuity between autistic and schizoid personality disorder trait burden: a prospective study in adolescence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(2):94-100. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001105

10. Lai MC, Baron-Cohen S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(11):1013-1027. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

11. Fusar-Poli L, Brondino N, Politi P, et al. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;10.1007/s00406-020-01189-2. doi:10.1007/s00406-020-01189-w

12. Loomes R, Hull L, Mandy WPL. What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(6):466-474. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013

13. Milner V, McIntosh H, Colvert E, et al. A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49(6):2389-2402. doi:10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

14. Giarelli E, Wiggins LD, Rice CE, et al. Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disabil Health J. 2010;3(2):107-116. doi:10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

15. Frazier TW, Georgiades S, Bishop SL, et al. Behavioral and cognitive characteristics of females and males with autism in the Simons Simplex Collection. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(3):329-40.e403. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.004

16. Julius RJ, Novitsky MA Jr, et al. Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15(1):34-44. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77

17. Spain D, Sin J, Chalder T, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorders and psychiatric co-morbidity: a review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2015;9, 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.019

18. Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Eack SM. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43(3):687-694. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1615-8

The skill of administering IM medications: 3 questions to consider

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

The intramuscular (IM) route is commonly used to administer medication in various clinical settings. Even when an IM medication is administered appropriately, patient factors such as high subcutaneous tissue, greater body mass index, and gender can lower the success rate of injections.1 A key but infrequently discussed issue is the skill of the individual administering the IM medication. Incorrectly administering an IM medication can lead to complications, such as abscesses, nerve injury, and skeletal muscle fibrosis.2 Poor IM injection technique can impact patient care and safety.1 For example, a poorly administered antipsychotic medication might lead to the patient receiving a subtherapeutic dose, and could prompt a clinician to ask, “Does this agitated patient need more emergent medication because the medication being given is not effective, or because the medication is not being administered properly?”

This article offers 3 questions to ask when clinicians are evaluating how IM medications are being administered in their clinical setting.

1. Who is administering the medication?

Is the person a registered nurse, licensed psychiatric technician, certified nursing assistant, licensed vocational nurse, or medical assistant? What a specific clinician is permitted to do in one state may not be permitted in another state. For example, in the state of Washington, under certain conditions a medical assistant is allowed to administer an IM medication.3

2. What is the individual’s training in administering IM medications?

Has the person been trained in the proper technique, depending on the body location? Is the injection being properly prepared? Is the correct needle gauge being used?

3. What is the individual’s comfort level with administering IM medications?

Is the person comfortable administering medication only when a patient is calm? Or are they comfortable administering medication when a patient is agitated and being physically held or in 4-point restraints, such as in inpatient psychiatric units or emergency departments?

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

1. Soliman E, Ranjan S, Xu T, et al. A narrative review of the success of intramuscular gluteal injections and its impact in psychiatry. Biodes Manuf. 2018;1(3):161-170.

2. Nicoll LH, Hesby A. Intramuscular injection: an integrative research review and guideline for evidence-based practice. Appl Nurs Res. 2002;15(3):149-162.

3. Washington State Legislature. WAC 246-827-0240. Medical assistant-certified—Administering medications and injections. Accessed January 10, 2022. https://apps.leg.wa.gov/wac/default.aspx?cite=246-827-0240

Brain stimulation for improved memory?

Electrical brain stimulation may have the potential to improve verbal memory, results of a small study of patients with epilepsy suggest.

Investigators observed improvements in patients implanted with a responsive neurostimulation system (RNS) to control seizures, in that the patients had improved word recall when the system was activated.

Beyond epilepsy, “we suspect that our results would be broadly applicable regardless of the underlying condition, for example, memory loss with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury,” Zulfi Haneef, MBBS, MD, associate professor of neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“Mental health conditions such as depression or psychosis could also benefit from targeted electrical stimulation. While we focused on enhancing a preferred brain function [such as memory], parallel areas of research may target enhancing function [such as weakness following stroke] or suppressing function [to manage conditions such as chronic pain,]” Dr. Haneef added.

The study was published online Jan. 17, 2022, in Neurosurgery.

As reported by this news organization, Following implantation of the system, patients attend the clinic for adjustments about every 8-12 weeks.

The investigators studied 17 patients with epilepsy and RNS implants who attended the clinic for routine appointments. A clinical neuropsychologist administered the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R), a well-validated list-learning measure of memory and verbal learning.

Patients were read a list of 12 semantically related words and asked to recall the list after three different learning trials. Active or sham stimulation was performed for every third word presented for immediate recall.

The investigators found that the HVLT-R delayed recall raw score was higher for the stimulation condition, compared with the nonstimulation condition (paired t-test, P = .04; effect size, d = 0.627).

“The patients were not aware of when the RNS system was being activated. We alternated when patients were undergoing stimulation versus no stimulation, and still found that when patients’ RNS systems were activated, their memory recall score was greater than when there was no stimulation,” Dr. Haneef said in a release.

This suggests the “human memory can be potentially improved by direct electrical brain stimulation at extremely low currents,” Dr. Haneef said in an interview.

Most patients in the study had stimulation of the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center.

“Moving forward we would want to look at how different patterns or standardized stimulation patterns affect memory. Ultimately, the underlying brain rhythms responsible for these changes in brain function need to be understood so that a more targeted and precise application of electrical stimulation can be achieved,” Dr. Haneef said.

The researchers also caution that, for this preliminary study, no follow-up testing was conducted to determine whether the memory improvement was transient and settled back to baseline after a specified period.

However, they note, this study lays the groundwork for larger-scale and extensive studies examining the nuanced effects of brain stimulation on human cognition and memory.

The study was funded by the Mike Hogg Foundation. Dr. Haneef and two coauthors received coverage for travel expenses but no honorarium for a NeuroPace advisory meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Electrical brain stimulation may have the potential to improve verbal memory, results of a small study of patients with epilepsy suggest.

Investigators observed improvements in patients implanted with a responsive neurostimulation system (RNS) to control seizures, in that the patients had improved word recall when the system was activated.

Beyond epilepsy, “we suspect that our results would be broadly applicable regardless of the underlying condition, for example, memory loss with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury,” Zulfi Haneef, MBBS, MD, associate professor of neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“Mental health conditions such as depression or psychosis could also benefit from targeted electrical stimulation. While we focused on enhancing a preferred brain function [such as memory], parallel areas of research may target enhancing function [such as weakness following stroke] or suppressing function [to manage conditions such as chronic pain,]” Dr. Haneef added.

The study was published online Jan. 17, 2022, in Neurosurgery.

As reported by this news organization, Following implantation of the system, patients attend the clinic for adjustments about every 8-12 weeks.

The investigators studied 17 patients with epilepsy and RNS implants who attended the clinic for routine appointments. A clinical neuropsychologist administered the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R), a well-validated list-learning measure of memory and verbal learning.

Patients were read a list of 12 semantically related words and asked to recall the list after three different learning trials. Active or sham stimulation was performed for every third word presented for immediate recall.

The investigators found that the HVLT-R delayed recall raw score was higher for the stimulation condition, compared with the nonstimulation condition (paired t-test, P = .04; effect size, d = 0.627).

“The patients were not aware of when the RNS system was being activated. We alternated when patients were undergoing stimulation versus no stimulation, and still found that when patients’ RNS systems were activated, their memory recall score was greater than when there was no stimulation,” Dr. Haneef said in a release.

This suggests the “human memory can be potentially improved by direct electrical brain stimulation at extremely low currents,” Dr. Haneef said in an interview.

Most patients in the study had stimulation of the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center.

“Moving forward we would want to look at how different patterns or standardized stimulation patterns affect memory. Ultimately, the underlying brain rhythms responsible for these changes in brain function need to be understood so that a more targeted and precise application of electrical stimulation can be achieved,” Dr. Haneef said.

The researchers also caution that, for this preliminary study, no follow-up testing was conducted to determine whether the memory improvement was transient and settled back to baseline after a specified period.

However, they note, this study lays the groundwork for larger-scale and extensive studies examining the nuanced effects of brain stimulation on human cognition and memory.

The study was funded by the Mike Hogg Foundation. Dr. Haneef and two coauthors received coverage for travel expenses but no honorarium for a NeuroPace advisory meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Electrical brain stimulation may have the potential to improve verbal memory, results of a small study of patients with epilepsy suggest.

Investigators observed improvements in patients implanted with a responsive neurostimulation system (RNS) to control seizures, in that the patients had improved word recall when the system was activated.

Beyond epilepsy, “we suspect that our results would be broadly applicable regardless of the underlying condition, for example, memory loss with Alzheimer’s disease or traumatic brain injury,” Zulfi Haneef, MBBS, MD, associate professor of neurology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in an interview.

“Mental health conditions such as depression or psychosis could also benefit from targeted electrical stimulation. While we focused on enhancing a preferred brain function [such as memory], parallel areas of research may target enhancing function [such as weakness following stroke] or suppressing function [to manage conditions such as chronic pain,]” Dr. Haneef added.

The study was published online Jan. 17, 2022, in Neurosurgery.

As reported by this news organization, Following implantation of the system, patients attend the clinic for adjustments about every 8-12 weeks.

The investigators studied 17 patients with epilepsy and RNS implants who attended the clinic for routine appointments. A clinical neuropsychologist administered the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised (HVLT-R), a well-validated list-learning measure of memory and verbal learning.

Patients were read a list of 12 semantically related words and asked to recall the list after three different learning trials. Active or sham stimulation was performed for every third word presented for immediate recall.

The investigators found that the HVLT-R delayed recall raw score was higher for the stimulation condition, compared with the nonstimulation condition (paired t-test, P = .04; effect size, d = 0.627).

“The patients were not aware of when the RNS system was being activated. We alternated when patients were undergoing stimulation versus no stimulation, and still found that when patients’ RNS systems were activated, their memory recall score was greater than when there was no stimulation,” Dr. Haneef said in a release.

This suggests the “human memory can be potentially improved by direct electrical brain stimulation at extremely low currents,” Dr. Haneef said in an interview.

Most patients in the study had stimulation of the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center.

“Moving forward we would want to look at how different patterns or standardized stimulation patterns affect memory. Ultimately, the underlying brain rhythms responsible for these changes in brain function need to be understood so that a more targeted and precise application of electrical stimulation can be achieved,” Dr. Haneef said.

The researchers also caution that, for this preliminary study, no follow-up testing was conducted to determine whether the memory improvement was transient and settled back to baseline after a specified period.

However, they note, this study lays the groundwork for larger-scale and extensive studies examining the nuanced effects of brain stimulation on human cognition and memory.

The study was funded by the Mike Hogg Foundation. Dr. Haneef and two coauthors received coverage for travel expenses but no honorarium for a NeuroPace advisory meeting.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROSURGERY

Identifying and preventing IPV: Are clinicians doing enough?

Violence against women remains a global dilemma in need of attention. Physical violence in particular, is the most prevalent type of violence across all genders, races, and nationalities.

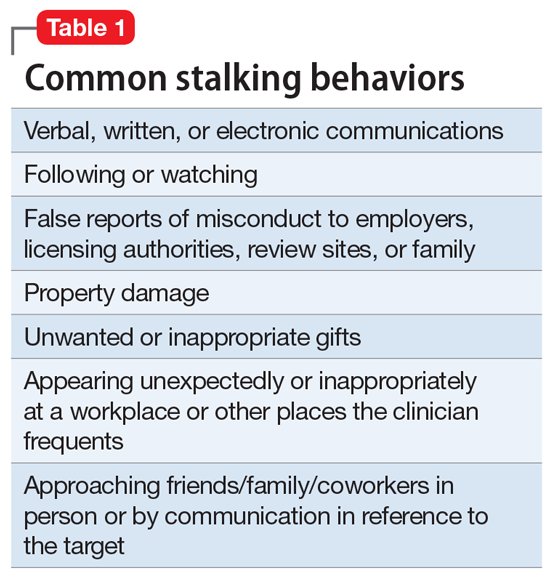

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says more than 43 million women and 38 million men report experiencing psychological aggression by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Meanwhile, 11 million women and 5 million men report enduring sexual or physical violence and intimate partner violence (IPV), and/or stalking by an intimate partner during their lifetimes, according to the CDC.1

Women who have endured this kind of violence might present differently from men. Some studies, for example, show a more significant association between mutual violence, depression, and substance use among women than men.2 Studies on the phenomenon of IPV victims/survivors becoming perpetrators of abuse are limited, but that this happens in some cases.

Having a psychiatric disorder is associated with a higher likelihood of being physically violent with a partner.3,4 One recent study of 250 female psychiatric patients who were married and had no history of drug abuse found that almost 68% reported psychological abuse, 52% reported sexual abuse, 38% social abuse, 37% reported economic abuse, and 25% reported physical abuse.5

Given those statistics and trends, it is incumbent upon clinicians – including those in primary care, psychiatry, and emergency medicine – to learn to quickly identify IPV survivors, and to use available prognostic tools to monitor perpetrators and survivors.

COVID pandemic’s influence

Isolation tied to the COVID-19 pandemic has been linked to increased IPV. A study conducted by researchers at the University of California, Davis, suggested that extra stress experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic caused by income loss, and the inability to pay for housing and food exacerbated the prevalence of IPV early during the pandemic.6

That study, where researchers collected in surveys of nearly 400 adults in the beginning in April 2020 for 10 weeks, showed that more services and communication are needed so that frontline health care and food bank workers, for example, in addition to social workers, doctors, and therapists, can spot the signs and ask clients questions about potential IPV. They could then link survivors to pertinent assistance and resources.

Furthermore, multiple factors probably have played a pivotal role in increasing the prevalence of IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, disruption to usual health and social services as well as diminished access to support systems, such as shelters, and charity helplines negatively affected the reporting of domestic violence.

Long before the pandemic, over the past decade, international and national bodies have played a crucial role in terms of improving the awareness and response to domestic violence.7,8 In addition, several policies have been introduced in countries around the globe emphasizing the need to inquire routinely about domestic violence. Nevertheless, mental health services often fail to adequately address domestic violence in clinical encounters. A systematic review of domestic violence assessment screening performed in a variety of health care settings found that evidence was insufficient to conclude that routine inquiry improved morbidity and mortality among victims of IPV.9 So the question becomes: How can we get our patients to tell us about these experiences so we can intervene?

Gender differences in perpetuating IPV

Several studies have found that abuse can result in various mental illnesses, such as depression, PTSD, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Again, men have a disproportionately higher rate of perpetrating IPV, compared with women. This theory has been a source of debate in the academic community for years, but recent research has confirmed that women do perpetuate violence against their partners to some extent.10,11

Some members of the LGBTQ+ community also report experiencing violence from partners, so as clinicians, we also need to raise our awareness about the existence of violence among same-sex couples. In fact, a team of Italian researchers report more than 50% of gay men and almost 75% of lesbian women reported that they had been psychologically abused by a partner.12 More research into this area is needed.

Our role as health care professionals

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advises that all clinic visits include regular IPV screening.13 But these screenings are all too rare. In fact, a meta-analysis of 19 trials of more than 1,600 participants showed only 9%-40% of doctors routinely test for IPV.14 That research clearly shows how important it is for all clinicians to execute IPV screening. However, numerous challenges toward screening exist, including personal discomfort, limited time during appointments, insufficient resources, and inadequate training.

One ongoing debate revolves around which clinician should screen for IPV. Should the psychiatrist carry out this role – or perhaps the primary care physician, nurse, or social worker? These issues become even more fraught when clinicians worry about offending the patient – especially if the clinician is a male.15

The bottom line is that physicians should inquire about intimate partner violence, because research indicates that women are more likely to reveal abuse when prompted. In addition, during physician appointments, they can use the physician-patient therapeutic connection to conduct a domestic violence evaluation, give resources to victims, and provide ongoing care. Patients who exhibit treatment resistance, persistent pain, depression, sleeplessness, and headaches should prompt psychiatrists to conduct additional investigations into the likelihood of intimate partner violence and domestic abuse.

W also should be attentive when counseling patients about domestic violence when suggesting life-changing events such as pregnancy, employment loss, separation, or divorce. Similar to the recommendations of the USPSTF that all women and men should be screened for IPV, it is suggested that physicians be conscious of facilitating a conversation and not being overtly judgmental while observing body cues. Using the statements such as “we have been hearing a lot of violence in our community lately” could be a segue to introduce the subject.

Asking the question of whether you are being hit rather than being abused has allowed more women to open up more about domestic violence. While physicians are aware that most victims might recant and often go back to their abusers, victims need to be counseled that the abuse might intensify and lead to death.