User login

Moving toward safer morcellation techniques

For minimally invasive surgeons throughout the world, particularly in the United States, as well as the patients we treat, April 17, 2014, is our day of infamy. It was on this day that the Food and Drug Administration recommended against the use of the electronic power morcellator. The basis of the agency’s decision was the concern about inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. Many hospitals, medical centers, and hospital systems subsequently banned the use of power morcellation. With such bans, a subsequent study by Wright et al. noted a decrease in the percentage of both laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy (JAMA. 2016 Aug 23-30;316[8]:877-8). This is concerning when you consider that the complication rate for abdominal hysterectomy is around 17%, compared with about 4% for the minimally invasive procedure.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked Tony Shibley, MD, to describe the PneumoLiner, the first FDA-approved bag for the purpose of contained laparoscopic morcellation. Dr. Shibley, who is in private practice in the Minneapolis area, first came to national attention because of his expertise in single-port surgery. He has been performing power morcellation in a contained system for 5 years and is the thought leader behind the design and creation of the PneumoLiner.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported receiving research funds from Espiner Medical Inc., and being a consultant to Olympus, which manufacturers the PneumoLiner.

For minimally invasive surgeons throughout the world, particularly in the United States, as well as the patients we treat, April 17, 2014, is our day of infamy. It was on this day that the Food and Drug Administration recommended against the use of the electronic power morcellator. The basis of the agency’s decision was the concern about inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. Many hospitals, medical centers, and hospital systems subsequently banned the use of power morcellation. With such bans, a subsequent study by Wright et al. noted a decrease in the percentage of both laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy (JAMA. 2016 Aug 23-30;316[8]:877-8). This is concerning when you consider that the complication rate for abdominal hysterectomy is around 17%, compared with about 4% for the minimally invasive procedure.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked Tony Shibley, MD, to describe the PneumoLiner, the first FDA-approved bag for the purpose of contained laparoscopic morcellation. Dr. Shibley, who is in private practice in the Minneapolis area, first came to national attention because of his expertise in single-port surgery. He has been performing power morcellation in a contained system for 5 years and is the thought leader behind the design and creation of the PneumoLiner.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported receiving research funds from Espiner Medical Inc., and being a consultant to Olympus, which manufacturers the PneumoLiner.

For minimally invasive surgeons throughout the world, particularly in the United States, as well as the patients we treat, April 17, 2014, is our day of infamy. It was on this day that the Food and Drug Administration recommended against the use of the electronic power morcellator. The basis of the agency’s decision was the concern about inadvertent spread of sarcomatous tissue. Many hospitals, medical centers, and hospital systems subsequently banned the use of power morcellation. With such bans, a subsequent study by Wright et al. noted a decrease in the percentage of both laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy (JAMA. 2016 Aug 23-30;316[8]:877-8). This is concerning when you consider that the complication rate for abdominal hysterectomy is around 17%, compared with about 4% for the minimally invasive procedure.

For this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, I have asked Tony Shibley, MD, to describe the PneumoLiner, the first FDA-approved bag for the purpose of contained laparoscopic morcellation. Dr. Shibley, who is in private practice in the Minneapolis area, first came to national attention because of his expertise in single-port surgery. He has been performing power morcellation in a contained system for 5 years and is the thought leader behind the design and creation of the PneumoLiner.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and past president of the AAGL and the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville and Schaumburg, Ill.; director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. He reported receiving research funds from Espiner Medical Inc., and being a consultant to Olympus, which manufacturers the PneumoLiner.

VIDEO: Tips for performing contained power morcellation

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

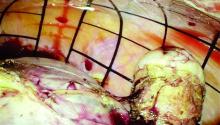

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Postoperative pain in women with preexisting chronic pain

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

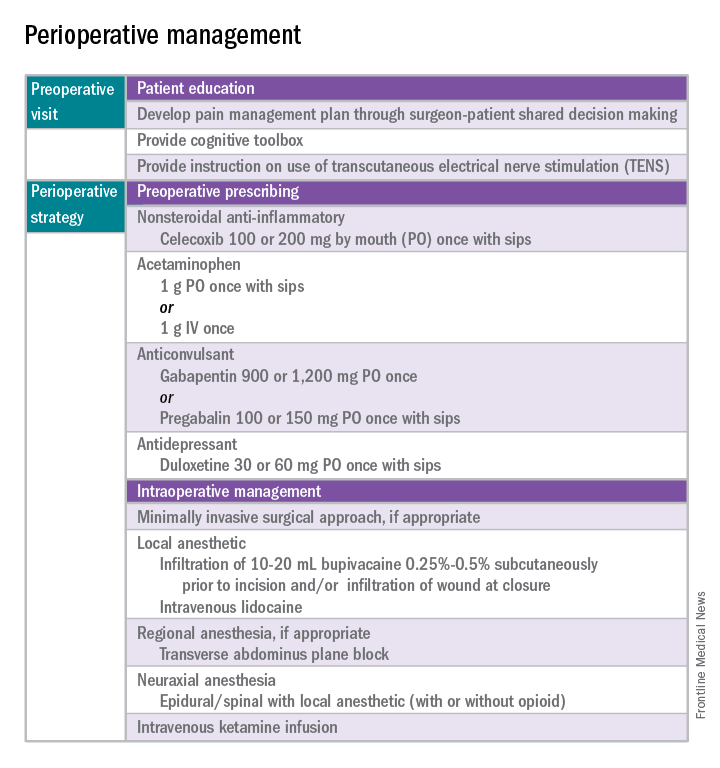

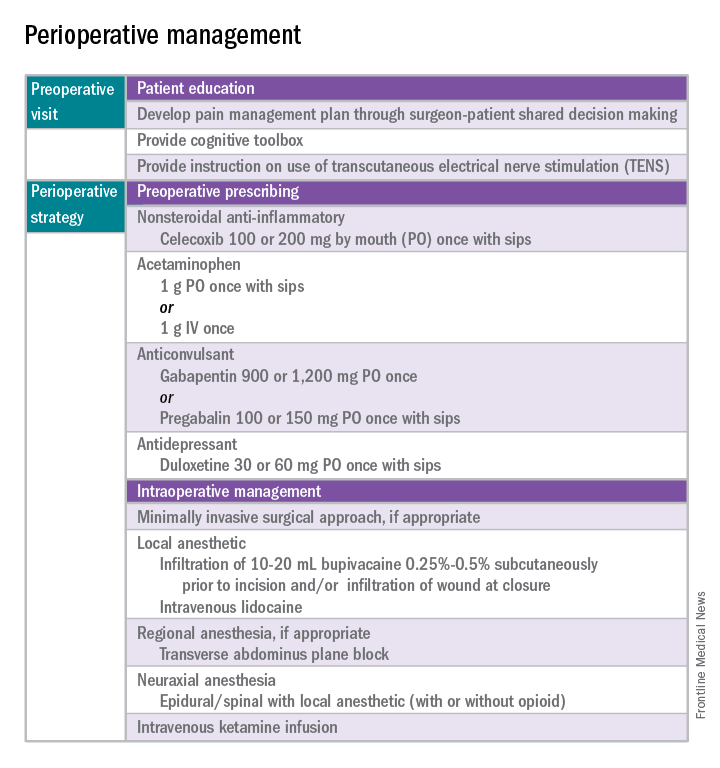

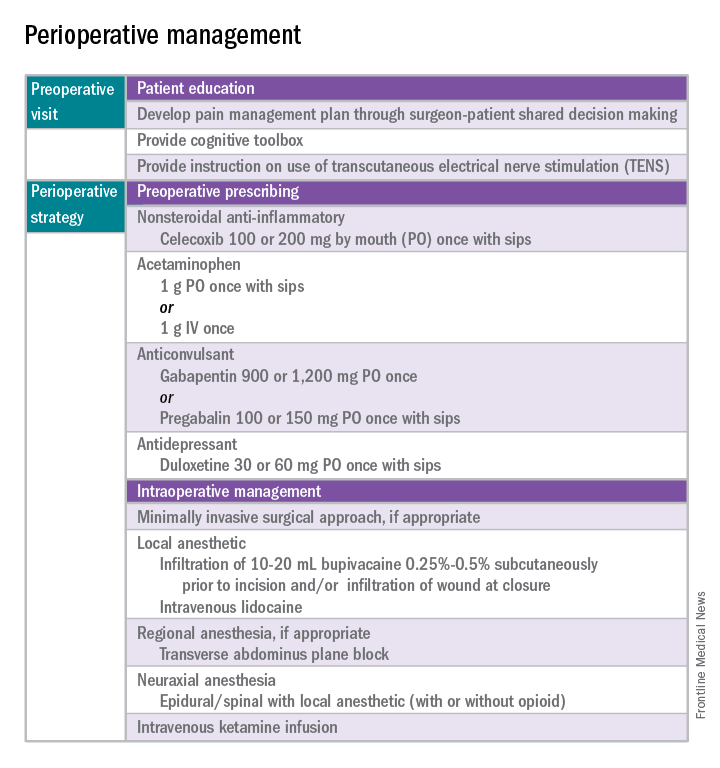

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

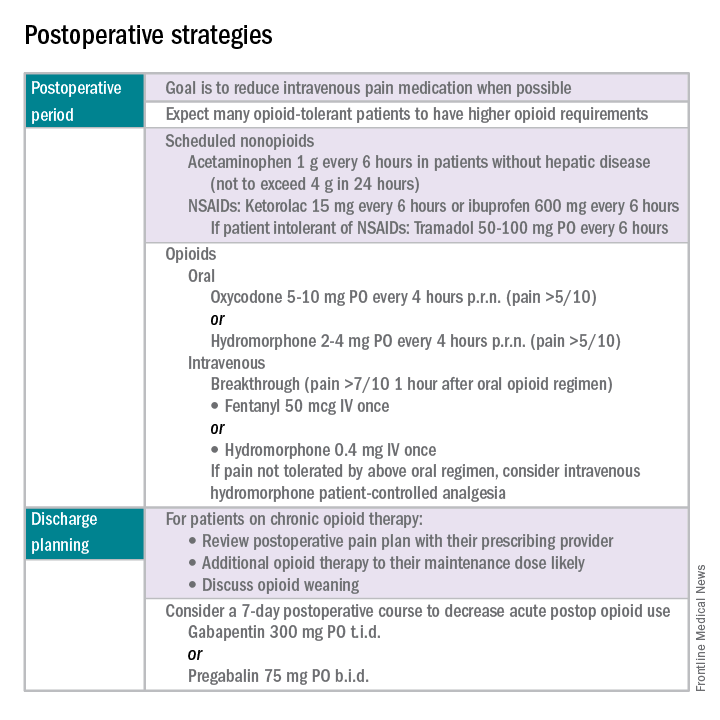

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

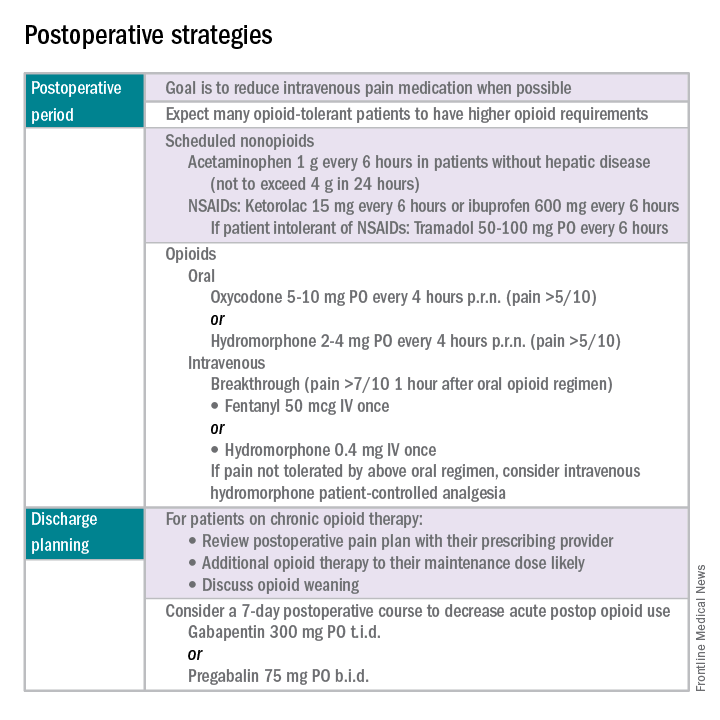

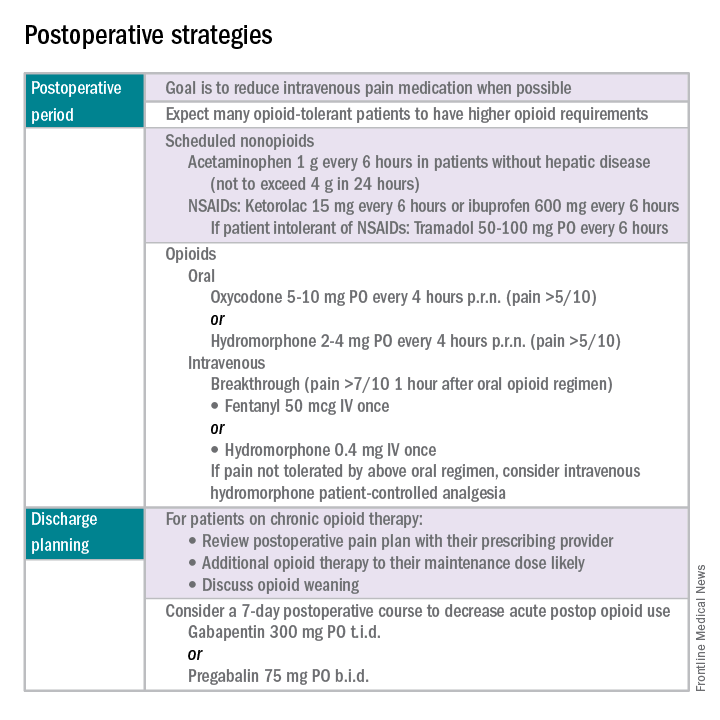

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Chronic pain disorders have reached epidemic levels in the United States, with the Institute of Medicine reporting more than 100 million Americans affected and health care costs more than $500 billion annually.1 Although many pain disorders are confined to the abdomen or pelvis (chronic pelvic pain, vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome, and bladder pain syndrome), others present with global symptoms (fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome). Women are more likely to be diagnosed with a chronic pain condition and more likely to seek treatment for chronic pain, including undergoing a surgical intervention. In fact, chronic pelvic pain alone affects upward of 20% of women in the United States, and, of the 400,000 hysterectomies performed each year (54.2%, abdominal; 16.7%, vaginal; and 16.8%, laparoscopic/robotic assisted), approximately 15% are for chronic pain.2

Neurobiology of pain

Perioperative pain control, specifically in women with preexisting pain disorders, can provide an additional challenge. Unlike acute pain, chronic pain (lasting more than 6 months) is associated with an amplified pain response of the central nervous system. This abnormal pain processing, known as centralization of pain, may result in a decrease of the inhibitory pain pathways and/or an increase of the amplification pathways, often augmenting the pain response of the original peripheral insult, specifically surgery. Because of these physiologic changes, a multimodal approach to perioperative pain should be offered, especially in women with preexisting pain. The approach ideally ought to target the different mechanisms of actions in both the peripheral and central nervous systems to provide an overall reduction in pain perception.

Preoperative visit

Perhaps the most underutilized opportunity to optimize postoperative pain is a proactive, preoperative approach. Preoperative education, including goal setting of postoperative pain expectations, has been associated with a significant reduction in postoperative opioid use, less preoperative anxiety, and a decreased length of surgical stay.3 While it is unknown exactly when this should be provided to the patient in the treatment course, it should occur prior to the day of surgery to allow for appropriate intervention.

The use of a shared decision-making model between the clinician and the chronic pain patient in the development of a pain management plan has been highly successful in improving pain outcomes in the outpatient setting.4 A similar method can be applied to the preoperative course as well. A detailed history (including the use of an opioid risk assessment tool) allows the clinician to identify patients at risk for opioid misuse and abuse. This is also an opportunity to review a plan for an opioid taper with the patient and the prescriber, if the postoperative plan includes opioid reduction/cessation. The preoperative visit may be an opportunity to adjust centrally acting medications (antidepressants, anticonvulsants) before surgery or to reduce the dose or frequency of high-risk medications, such as benzodiazepines.

Perioperative strategy

One of the most impactful ways for us, as surgeons, to reduce tissue injury and decrease pain from surgery is by offering a minimally invasive approach. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are well established, resulting in improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, lower infection rates, decreased length of hospital stay, and a faster recovery, compared with laparotomy. Because patients with chronic pain disorders are at increased risk of greater acute postoperative pain and have an elevated risk for the development of chronic postsurgical pain, a minimally invasive surgical approach should be prioritized, when available.

Perioperative multimodal drug therapy is associated with significant decreases in opioid consumption and reductions in acute postoperative pain.6 Recently, a multidisciplinary expert panel from the American Pain Society devised an evidence-based clinical practice guideline for postoperative pain.7 While there is no consensus as to the best regimen specific to gynecologic surgery, the general principles are similar across disciplines.

The postoperative period

Opioid-tolerant patients may experience greater pain during the first 24 hours postoperatively and require an increase in opioids, compared with opioid-naive patients.8 In the event that a postoperative patient does not respond as expected to the usual course, that patient should be evaluated for barriers to routine postoperative care, such as a surgical complication, opioid tolerance, or psychological distress. Surgeons should be aggressive with pain management immediately after surgery, even in the opioid-tolerant patient, and make short-term adjustments as needed based on the pain response. These patients will require pain medications beyond their baseline dose. Additionally, if an opioid taper is not planned in a chronic opioid user, work with the patient and the long-term opioid prescriber in restarting baseline opioid therapy outside of the acute surgical window.

References

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2011.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):233-41.

3. N Engl J Med. 1964 Apr 16;270:825-7.

4. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Jul;18(1):38-48.

5. Pain. 2010 Dec;151(3):694-702.

6. Anesthesiology. 2005 Dec;103(6):1296-304.

7. J Pain. 2016 Feb;17(2):131-57.

8. Pharmacotherapy. 2008 Dec;28(12):1453-60.

Dr. Carey is the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and specializes in the medical and surgical management of pelvic pain disorders. Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at UNC–Chapel Hill. They reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Point/Counterpoint: Is endograft PAA repair durable?

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.

Patrick Muck, MD, is chief of vascular surgery and director of vascular residency and fellowship at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He is also on staff at Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, and is affiliated with TriHealth Heart Institute in southwestern Ohio. Dr. Muck had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.

Patrick Muck, MD, is chief of vascular surgery and director of vascular residency and fellowship at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He is also on staff at Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, and is affiliated with TriHealth Heart Institute in southwestern Ohio. Dr. Muck had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair is durable

Endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms is vastly superior to all other previous techniques of popliteal aneurysm repair. Half of all popliteal artery aneurysms are bilateral, and 40% are associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm; 1%-2% of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm have a popliteal aneurysm (ANZ J Surg. 2006 Oct;76[10]:912-5). Less than 0.01% of hospitalized patients have popliteal artery aneurysms, and men are 20 times more prone to them than women are.

Traditional treatment involves either bypass with interval ligation or a direct posterior approach with an interposition graft, but surgery is not without its problems. I think of the retired anesthesiologist who came to me with a popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) that his primary care doctor diagnosed. “I’m not having any damn femoral popliteal bypass operation,” he told me. “Every single one of those patients dies.”

Endograft repair is a technique that is reaching its prime, as a growing number of reports have shown – although none of these studies has large numbers because the volume just isn’t available. One recent paper compared 52 open and 23 endovascular PAA repairs (Ann Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;30:253-7) and found both had similarly high rates of reintervention – 50% at 4 years. But it is noteworthy that the endovascular results improved with time.

A University of Pittsburgh study of 186 open and endovascular repairs found that patients with acute presentations of embolization or aneurysm thrombosis did better with open surgery. In addition, while open repair had superior patency initially after surgery, midterm secondary patency and amputation rates of open and endovascular repair were similar (J Vasc Surg. 2016 Jan;63[1]:70-6).

A Netherlands study of 72 PAA treated with endografting showed that 84% had primary patency at 1 year, and 74% had assisted primary patency at 3 years (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016 Jul;52[1]:99-104). Among these patients, 13 had late occlusions, 7 were converted to bypass, and 2 required thrombolysis; but none required limb amputation.

A meta-analysis of 540 patients found no statistically significant difference in outcomes between endovascular and open repair for PAA (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50(3):351-9). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies and 514 patients also found no difference in pooled primary and secondary patency at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7).

There certainly are contradictory studies, such as one by Dr. Alik Farber’s group in Boston that showed open repair is superior to endovascular surgery (J Vasc Surg. 2015 Mar;61[3]:663-9); but retrospective database mining certainly has its limitations. Their retrospective study queried the Vascular Quality Initiative database and found that 95% of patients who had open elective popliteal aneurysm repair were free from major adverse limb events, vs. 80% for endovascular treatments.

The best outcomes of open repair happen with autologous vein, but there is precious little of that around now. Emergency patients would probably do better with open surgery, but in elective repair there is no clear differential data.

So, if that’s the case, I’m going to take the small incision.

Peter Rossi, MD, FACS, is an associate professor of surgery and radiology, and the clinical director of vascular surgery, at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. He is also on staff at Clement J. Zablocki Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Milwaukee. Dr. Rossi had no financial relationships to disclose.

Endovascular repair may not be durable

Debating the durability of elective endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysm raises a question: Who determines durability anyway?

Is it the patients who only want the Band-Aid and no incision? I don’t think so. Is it the interventionalist who only does endovascular repairs? I don’t think so. I’m sure it’s not the insurance companies, who only worry about cost containment, either.

So, who should determine durability of endovascular popliteal artery aneurysm (PAA) repair?

So, the question is, do we have such data?

There are multiple reports looking at how well open repair works. It has been done for decades. In 2008, a Veterans Affairs study of 583 open PAA repairs reported low death rates and excellent rates of limb salvage at 2 years, even in high-risk patients (J Vasc Surg. 2008 Oct;48[4]:845-51). Open surgical repair has excellent documented durability, and that is not the question at hand.

Endovascular repair has some presumed advantages. It’s less invasive and involves less postoperative pain and a quicker recovery. But it is not without problems – graft thrombosis and occlusion, endoleaks, distal limb ischemia, and stent fractures among them.

Surgery, to be clear, is not perfect, either. One of my patients who years ago presented with an occluded PAA underwent open bypass repair – but then went on later to have a pseudoaneurysm of the proximal anastomosis. I repaired this with an endograft, and he has done quite well. So, we all do endograft repairs, walk out, chest bump the Gore rep, and send the patient home that day.

Is it durable, though?

Most of the data on endovascular repair are from single-center studies dating back to 2003. There’s only one prospective trial comparing endovascular vs. open repair (J Vasc Surg. 2005 Aug;42[2]:185-93), but it was a single-center trial with a severe power limitation, because it involved only 30 patients. It found endovascular repair was comparable to open surgery. Also, I suspect a great deal of selection bias is involved in studies of endovascular repair.

A number of studies have found endovascular repair is not inferior to surgical repair. For example, a study by Dr. Audra Duncan, at Mayo Clinic, and her colleagues found that primary and secondary patency rates of elective and emergent stenting were excellent – but the study results only extended out to 2 years (J Vasc Surg. 2013 May;57[5]:1299-305). I don’t think we could hang our hat on that.

A Swedish study that compared open and endovascular surgery in 592 patients reported that endovascular repair has “significantly inferior results compared with open repair,” particularly in those who present with acute ischemia (Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015 Sep;50[3]:342-50). A close look at the data shows that primary patency rates were 89% for open repair and 67.4% for stent graft.

Referencing the systematic review and meta-analysis that Dr. Rossi cited, the primary patency of endovascular repair was only 69% and the secondary patency rate was 77% at 5 years (J Endovasc Ther. 2015 Jun;22[3]:330-7). As physicians, I submit that we can do better.

A Netherlands study investigated stent fractures, finding that 17% (13 out of 78 cases) had circumferential fractures (J Vasc Surg. 2010 Jun;51[6]:1413-8). This study only included circumferential stent fractures and excluded localized strut fractures. I think these studies show that endovascular repair is not always durable.

I want to remind you that we are vascular surgeons, so it is appropriate for us to embrace surgical bypass and its known durability, especially when the durability of endovascular repair is still not known.

Patrick Muck, MD, is chief of vascular surgery and director of vascular residency and fellowship at Good Samaritan Hospital, Cincinnati. He is also on staff at Bethesda North Hospital, Cincinnati, and is affiliated with TriHealth Heart Institute in southwestern Ohio. Dr. Muck had no financial relationships to disclose.

AT MIDWESTERN VASCULAR 2016

Primary prophylaxis of bleeding in portal hypertension safe in cirrhosis with high-risk varices

Primary prophylaxis of bleeding in children with portal hypertension is safe for treatment of cirrhosis associated with high-risk varices, according to Mathieu Duché, MD, of Hôpital Bicêtre in France, and his associates.

In a study from July 1989 to June 2014, researchers examined 1,300 children with various causes of liver disease, based on the presence of palpable splenomegaly and/or ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension. During the study, a high-risk pattern – including grade 3 esophageal varices, grade 2 varices with red markings and/or gastric varices along the cardia, or gastric varices with or without esophageal varices – was present in 96% of the 246 children who bled spontaneously and in 11% of the 872 children who did not bleed. Of the 246 children who bled spontaneously, 170 children with high-risk varices underwent primary prophylaxis of bleeding with portal surgery, endoscopic banding/sclerotherapy of varices, or interventional radiology.

In 50 children with noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension and the high risk varices, those with portal vein obstruction underwent portal surgery (Rex bypass or portosystemic shunt) as primary prophylaxis. Endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy was performed instead in younger children or when angiograms did not favor the surgery. One child who had a severe stenosis of the portal trunk underwent successful interventional radiology. After a mean follow-up of 5.5 years after primary prophylaxis, all these patients are alive.

Of the 120 children with cirrhosis with high risk varices, 10 children with well compensated cirrhosis received a portosystemic shunt; thrombosis of the shunt occurred in 1 child who later underwent liver transplantation, and 1 child with a patent shunt developed portosystemic encephalopathy and underwent liver transplantation. No gastrointestinal bleeding was recorded in these 10 children who were alive at the last follow-up.

Of 110 children who underwent endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy, in 76 children there was eradication of varices; there was a relapse of high-risk varices in 20 children, so further endoscopic was needed. In two children who initially underwent endoscopic treatment and achieved eradication of varices, a protein-losing enteropathy and bleeding from ectopic varices, respectively, required subsequent treatment by a surgical portosystemic shunt. Of the 34 children in whom no eradication was obtained with this primary prophylaxis, 3 died and 29 underwent liver transplantation before eradication could be obtained; 1 was lost to follow-up and 1 received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. After a mean follow-up of 5 years, 8 of the 120 children with cirrhosis who underwent primary prophylaxis have died: 4 children died before transplantation, 2 of septic shock unrelated to endoscopic treatment, and 1 of atrioventricular block during variceal injection of aethoxysklerol. Four other children died after transplantation.

It was noted that no esophageal or gastric perforation was observed as a consequence of endoscopic primary prophylaxis in the pre- or posttransplantation period.

“Although no statistical analysis was performed because this was not a controlled study, the results suggest that, compared with liver transplantation performed directly or with care after a spontaneous bleed, primary prophylaxis of bleeding has a fairly good safety record for the management of children with cirrhosis and high-risk varices,” researchers concluded.

Read the full study in the Journal of Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.006).

Primary prophylaxis of bleeding in children with portal hypertension is safe for treatment of cirrhosis associated with high-risk varices, according to Mathieu Duché, MD, of Hôpital Bicêtre in France, and his associates.

In a study from July 1989 to June 2014, researchers examined 1,300 children with various causes of liver disease, based on the presence of palpable splenomegaly and/or ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension. During the study, a high-risk pattern – including grade 3 esophageal varices, grade 2 varices with red markings and/or gastric varices along the cardia, or gastric varices with or without esophageal varices – was present in 96% of the 246 children who bled spontaneously and in 11% of the 872 children who did not bleed. Of the 246 children who bled spontaneously, 170 children with high-risk varices underwent primary prophylaxis of bleeding with portal surgery, endoscopic banding/sclerotherapy of varices, or interventional radiology.

In 50 children with noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension and the high risk varices, those with portal vein obstruction underwent portal surgery (Rex bypass or portosystemic shunt) as primary prophylaxis. Endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy was performed instead in younger children or when angiograms did not favor the surgery. One child who had a severe stenosis of the portal trunk underwent successful interventional radiology. After a mean follow-up of 5.5 years after primary prophylaxis, all these patients are alive.

Of the 120 children with cirrhosis with high risk varices, 10 children with well compensated cirrhosis received a portosystemic shunt; thrombosis of the shunt occurred in 1 child who later underwent liver transplantation, and 1 child with a patent shunt developed portosystemic encephalopathy and underwent liver transplantation. No gastrointestinal bleeding was recorded in these 10 children who were alive at the last follow-up.

Of 110 children who underwent endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy, in 76 children there was eradication of varices; there was a relapse of high-risk varices in 20 children, so further endoscopic was needed. In two children who initially underwent endoscopic treatment and achieved eradication of varices, a protein-losing enteropathy and bleeding from ectopic varices, respectively, required subsequent treatment by a surgical portosystemic shunt. Of the 34 children in whom no eradication was obtained with this primary prophylaxis, 3 died and 29 underwent liver transplantation before eradication could be obtained; 1 was lost to follow-up and 1 received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. After a mean follow-up of 5 years, 8 of the 120 children with cirrhosis who underwent primary prophylaxis have died: 4 children died before transplantation, 2 of septic shock unrelated to endoscopic treatment, and 1 of atrioventricular block during variceal injection of aethoxysklerol. Four other children died after transplantation.

It was noted that no esophageal or gastric perforation was observed as a consequence of endoscopic primary prophylaxis in the pre- or posttransplantation period.

“Although no statistical analysis was performed because this was not a controlled study, the results suggest that, compared with liver transplantation performed directly or with care after a spontaneous bleed, primary prophylaxis of bleeding has a fairly good safety record for the management of children with cirrhosis and high-risk varices,” researchers concluded.

Read the full study in the Journal of Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.006).

Primary prophylaxis of bleeding in children with portal hypertension is safe for treatment of cirrhosis associated with high-risk varices, according to Mathieu Duché, MD, of Hôpital Bicêtre in France, and his associates.

In a study from July 1989 to June 2014, researchers examined 1,300 children with various causes of liver disease, based on the presence of palpable splenomegaly and/or ultrasonographic signs of portal hypertension. During the study, a high-risk pattern – including grade 3 esophageal varices, grade 2 varices with red markings and/or gastric varices along the cardia, or gastric varices with or without esophageal varices – was present in 96% of the 246 children who bled spontaneously and in 11% of the 872 children who did not bleed. Of the 246 children who bled spontaneously, 170 children with high-risk varices underwent primary prophylaxis of bleeding with portal surgery, endoscopic banding/sclerotherapy of varices, or interventional radiology.

In 50 children with noncirrhotic causes of portal hypertension and the high risk varices, those with portal vein obstruction underwent portal surgery (Rex bypass or portosystemic shunt) as primary prophylaxis. Endoscopic banding or sclerotherapy was performed instead in younger children or when angiograms did not favor the surgery. One child who had a severe stenosis of the portal trunk underwent successful interventional radiology. After a mean follow-up of 5.5 years after primary prophylaxis, all these patients are alive.

Of the 120 children with cirrhosis with high risk varices, 10 children with well compensated cirrhosis received a portosystemic shunt; thrombosis of the shunt occurred in 1 child who later underwent liver transplantation, and 1 child with a patent shunt developed portosystemic encephalopathy and underwent liver transplantation. No gastrointestinal bleeding was recorded in these 10 children who were alive at the last follow-up.