User login

Don’t shy away from vaginal salpingectomy

SAN ANTONIO – Surgeons at Houston Methodist Hospital reported a 75% success rate in removing both fallopian tubes during vaginal hysterectomy in a study presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Serous ovarian carcinoma is now thought to arise from the distal fallopian tube, and it’s estimated that salpingectomy prevents diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 1 in 225 women and death from ovarian cancer in 1 in 450 women. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that surgeons and patients “discuss the potential benefits of the removal of the fallopian tubes” during hysterectomy in women not having an oophorectomy.

The findings from the Houston team show that “it’s feasible in most cases, with very little risk,” said Danielle Antosh, MD, lead investigator and director of the Center for Restorative Pelvic Medicine at Houston Methodist Urogynecology Associates.

“People are doing laparoscopic hysterectomies or robotic hysterectomies” to get at the fallopian tubes, “but they shouldn’t be deterred from trying to remove the fallopian tubes vaginally,” Dr. Antosh said at the SGS 2017 meeting. When women are having a vaginal hysterectomy, “why not try to remove the fallopian tubes? It’s something I would definitely consider counseling your patients about.”

Dr. Antosh said that residents should be taught how to perform salpingectomy during vaginal hysterectomy. “I think it is definitely feasible for residents to do.” Technically, “it’s a lot easier than removing the ovaries” vaginally, she said.

The 70 women in the study were undergoing vaginal hysterectomies by attending physicians for benign reasons, mostly uterine prolapse, followed by heavy menstrual flow and fibroids. In total, 52 (75%) had successful concomitant bilateral vaginal salpingectomies, and 7 additional women had one tube removed. Success was more likely with increasing parity and a history of prolapse. Most of the failures were because the tubes were too high in the pelvis or there were adhesions from prior adnexal surgery. Even with prior adnexal surgery, however, the success rate was 50%.

Vaginal salpingectomy added a mean of 11 minutes to surgery and a mean of 5 mL blood loss. There were no complications reported from including salpingectomy with vaginal hysterectomy. The study wasn’t powered to detect an impact on menopause symptoms, but there was a decrease in menopause symptoms at 16 week follow-up in the salpingectomy group, perhaps related to less sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

The mean age in the study was 51 years, and mean body mass index was 27 kg/m2. There were no malignancies found on tubal pathology.

Five women were transferred to an abdominal approach because of a large uterus or discovery of ovarian pathology. None were transferred for the purpose of salpingectomy.

There was no external funding for the study, and the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Surgeons at Houston Methodist Hospital reported a 75% success rate in removing both fallopian tubes during vaginal hysterectomy in a study presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Serous ovarian carcinoma is now thought to arise from the distal fallopian tube, and it’s estimated that salpingectomy prevents diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 1 in 225 women and death from ovarian cancer in 1 in 450 women. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that surgeons and patients “discuss the potential benefits of the removal of the fallopian tubes” during hysterectomy in women not having an oophorectomy.

The findings from the Houston team show that “it’s feasible in most cases, with very little risk,” said Danielle Antosh, MD, lead investigator and director of the Center for Restorative Pelvic Medicine at Houston Methodist Urogynecology Associates.

“People are doing laparoscopic hysterectomies or robotic hysterectomies” to get at the fallopian tubes, “but they shouldn’t be deterred from trying to remove the fallopian tubes vaginally,” Dr. Antosh said at the SGS 2017 meeting. When women are having a vaginal hysterectomy, “why not try to remove the fallopian tubes? It’s something I would definitely consider counseling your patients about.”

Dr. Antosh said that residents should be taught how to perform salpingectomy during vaginal hysterectomy. “I think it is definitely feasible for residents to do.” Technically, “it’s a lot easier than removing the ovaries” vaginally, she said.

The 70 women in the study were undergoing vaginal hysterectomies by attending physicians for benign reasons, mostly uterine prolapse, followed by heavy menstrual flow and fibroids. In total, 52 (75%) had successful concomitant bilateral vaginal salpingectomies, and 7 additional women had one tube removed. Success was more likely with increasing parity and a history of prolapse. Most of the failures were because the tubes were too high in the pelvis or there were adhesions from prior adnexal surgery. Even with prior adnexal surgery, however, the success rate was 50%.

Vaginal salpingectomy added a mean of 11 minutes to surgery and a mean of 5 mL blood loss. There were no complications reported from including salpingectomy with vaginal hysterectomy. The study wasn’t powered to detect an impact on menopause symptoms, but there was a decrease in menopause symptoms at 16 week follow-up in the salpingectomy group, perhaps related to less sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

The mean age in the study was 51 years, and mean body mass index was 27 kg/m2. There were no malignancies found on tubal pathology.

Five women were transferred to an abdominal approach because of a large uterus or discovery of ovarian pathology. None were transferred for the purpose of salpingectomy.

There was no external funding for the study, and the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

SAN ANTONIO – Surgeons at Houston Methodist Hospital reported a 75% success rate in removing both fallopian tubes during vaginal hysterectomy in a study presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons.

Serous ovarian carcinoma is now thought to arise from the distal fallopian tube, and it’s estimated that salpingectomy prevents diagnosis of ovarian cancer in 1 in 225 women and death from ovarian cancer in 1 in 450 women. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that surgeons and patients “discuss the potential benefits of the removal of the fallopian tubes” during hysterectomy in women not having an oophorectomy.

The findings from the Houston team show that “it’s feasible in most cases, with very little risk,” said Danielle Antosh, MD, lead investigator and director of the Center for Restorative Pelvic Medicine at Houston Methodist Urogynecology Associates.

“People are doing laparoscopic hysterectomies or robotic hysterectomies” to get at the fallopian tubes, “but they shouldn’t be deterred from trying to remove the fallopian tubes vaginally,” Dr. Antosh said at the SGS 2017 meeting. When women are having a vaginal hysterectomy, “why not try to remove the fallopian tubes? It’s something I would definitely consider counseling your patients about.”

Dr. Antosh said that residents should be taught how to perform salpingectomy during vaginal hysterectomy. “I think it is definitely feasible for residents to do.” Technically, “it’s a lot easier than removing the ovaries” vaginally, she said.

The 70 women in the study were undergoing vaginal hysterectomies by attending physicians for benign reasons, mostly uterine prolapse, followed by heavy menstrual flow and fibroids. In total, 52 (75%) had successful concomitant bilateral vaginal salpingectomies, and 7 additional women had one tube removed. Success was more likely with increasing parity and a history of prolapse. Most of the failures were because the tubes were too high in the pelvis or there were adhesions from prior adnexal surgery. Even with prior adnexal surgery, however, the success rate was 50%.

Vaginal salpingectomy added a mean of 11 minutes to surgery and a mean of 5 mL blood loss. There were no complications reported from including salpingectomy with vaginal hysterectomy. The study wasn’t powered to detect an impact on menopause symptoms, but there was a decrease in menopause symptoms at 16 week follow-up in the salpingectomy group, perhaps related to less sexual dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

The mean age in the study was 51 years, and mean body mass index was 27 kg/m2. There were no malignancies found on tubal pathology.

Five women were transferred to an abdominal approach because of a large uterus or discovery of ovarian pathology. None were transferred for the purpose of salpingectomy.

There was no external funding for the study, and the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

* The meeting sponsor information was updated 6/9/2017.

AT SGS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Three-quarters of women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for benign reasons had successful concomitant bilateral vaginal salpingectomy.

Data source: A single-center, observational study among 70 women undergoing vaginal hysterectomy for benign reasons.

Disclosures: There was no external funding and the investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Abdominal myomectomy: Patient and surgical technique considerations

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

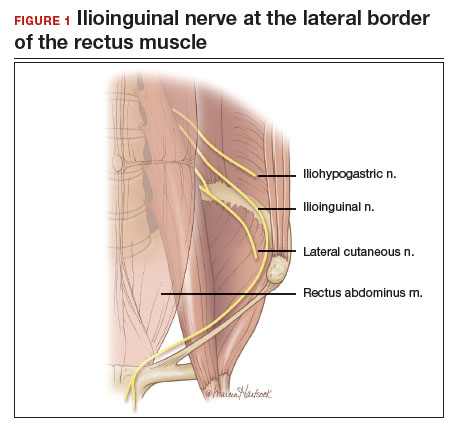

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

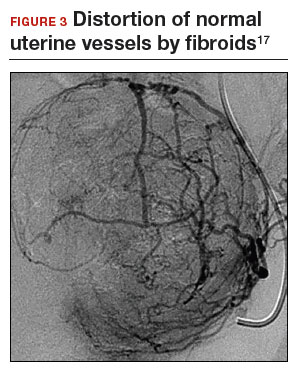

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

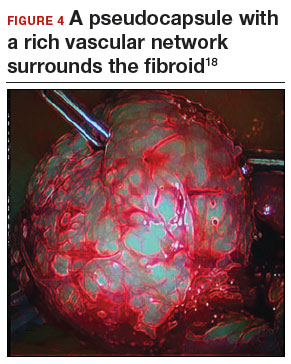

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

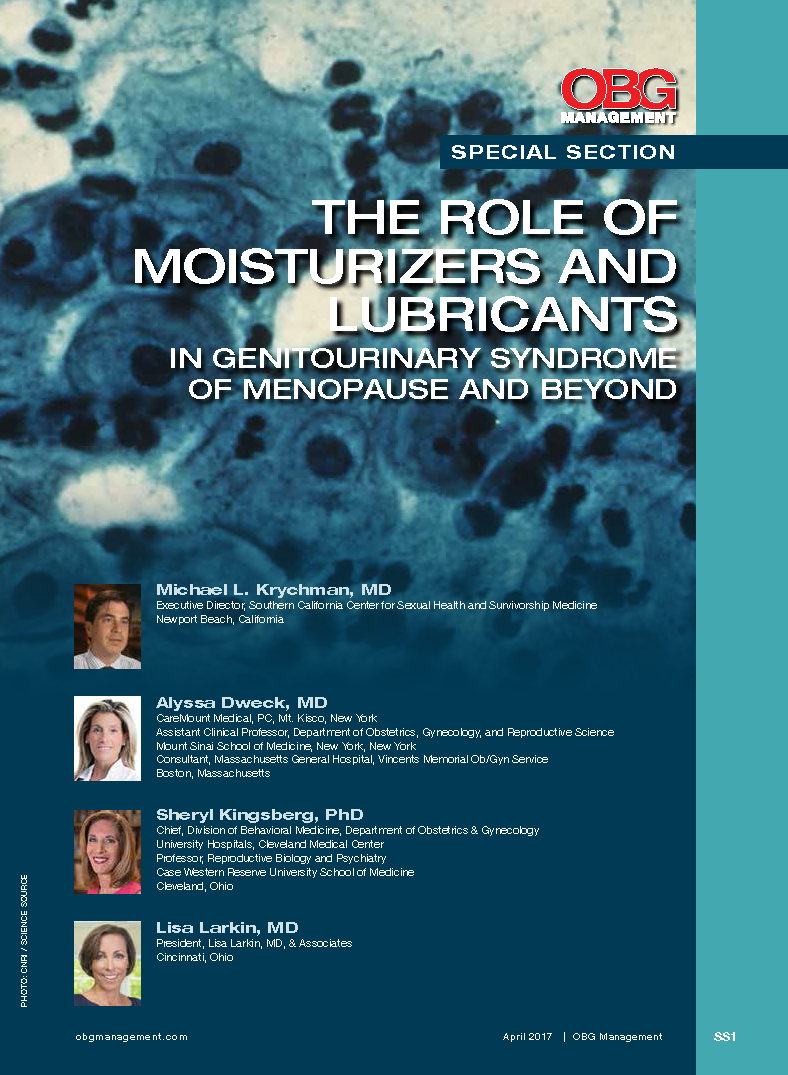

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

CASE Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to the office for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy.

Abdominal myomectomy: A good option for many women

Abdominal myomectomy is an underutilized procedure. With fibroids as the indication for surgery, 197,000 hysterectomies were performed in the United States in 2010, compared with approximately 40,000 myomectomies.1,2 Moreover, the rates of both laparoscopic and abdominal myomectomy have decreased following the controversial morcellation advisory issued by the US Food and Drug Administration.3

The differences in the hysterectomy and myomectomy rates might be explained by the many myths ascribed to myomectomy. Such myths include the beliefs that myomectomy, when compared with hysterectomy, is associated with greater risk of visceral injury, more blood loss, poor uterine healing, and high risk of fibroid recurrence, and that myomectomy is unlikely to improve patient symptoms.

Studies show, however, that these beliefs are wrong. The risk of needing treatment for new fibroid growth following myomectomy is low.4 Hysterectomy, compared with myomectomy for similar size uteri, is actually associated with a greater risk of injury to the bowel, bladder, and ureters and with a greater risk of operative hemorrhage. Furthermore, hysterectomy (without oophorectomy) can be associated with early menopause in approximately 10% of women, while myomectomy does not alter ovarian hormones. (See “7 Myomectomy myths debunked,” which appeared in the February 2017 issue of OBG

For women who have serious medical problems (severe anemia, ureteral obstruction) due to uterine fibroids, surgery usually is necessary. In addition, women may request surgery for fibroid-associated quality-of-life concerns, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, or incontinence. In one prospective study, the authors found that when women were assessed 6 months after undergoing myomectomy, 75% reported experiencing a significant decrease in bothersome symptoms.7

Myomectomy may be considered even for women with large uterine fibroids who desire uterine conservation. In a systematic review of the perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with abdominal hysterectomy for fibroids, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 16 to 18 weeks, no difference was found in major morbidity rates.8 Investigators who studied 91 women with uterine size ranging from 16 to 36 weeks who underwent abdominal myomectomy reported 1 bowel injury, 1 bladder injury, and 1 reoperation for bowel obstruction; no women had conversion to hysterectomy.9

Since ObGyn residency training emphasizes hysterectomy techniques, many residents receive only limited exposure to myomectomy procedures. Increased exposure to and comfort with myomectomy surgical technique would encourage more gynecologists to offer this option to their patients who desire uterine conservation, including those who do not desire future childbearing.

Imaging techniques are essential in the preoperative evaluation

For women with fibroid-related symptoms who desire surgery with uterine preservation, determining the myomectomy approach (abdominal, laparoscopic/robotic, hysteroscopic) depends on accurate assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids. If abdominal myomectomy is planned because of uterine size, the presence of numerous fibroids, or patient choice, transvaginal/transabdominal ultrasonography usually is adequate for anticipating what will be found during surgery. Sonography is readily available and is the least costly imaging technique that can help differentiate fibroids from other pelvic pathology. Although small fibroids may not be seen on sonography, they can be palpated and removed at the time of open surgery.

If submucous fibroids need to be better defined, saline-infusion sonography can be performed. However, if laparoscopic/robotic myomectomy (which precludes accurate palpation during surgery) is being considered, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows the best assessment of the size, number, and position of the fibroids.10 When adenomyosis is considered in the differential diagnosis, MRI is an accurate way to determine its presence and helps in planning the best surgical procedure and approach.

Correct anemia before surgery

Women with fibroids may have anemia requiring correction before surgery to reduce the need for intraoperative or postoperative blood transfusion. Mild iron deficiency anemia can be treated prior to surgery with oral elemental iron 150 to 200 mg per day. Vitamin C 1,000 mg per day helps to increase intestinal iron absorption. Three weeks of treatment with oral iron can increase hemoglobin concentration by 2 g/dL.

For more severe anemia or rapid correction of anemia, intravenous (IV) iron sucrose infusions, 200 mg infused over 2 hours and given 3 times per week for 3 weeks, can increase hemoglobin by 3 g/dL.11 In our ObGyn practice, hematologists manage iron infusions.

Read about abdominal incision technique

Abdominal incision technique

Even a large uterus with multiple fibroids usually can be managed through use of a transverse lower abdominal incision. Prior to reaching the lateral borders of the rectus abdominis, curve the fascial incision cephalad to avoid injury to the ileoinguinal nerves (FIGURE 1). Detaching the midline rectus fascia (linea alba) from the anterior abdominal wall, starting at the pubic symphysis and continuing up to the umbilicus, frees the rectus muscles and allows them to be easily separated (see VIDEO 1). Since fascia is not elastic, these 2 steps are important to allow more room to deliver the uterus through the incision.

Delivery of the uterus through the incision isolates the surgical field from the bowel, bladder, ureters, and pelvic nerves. Once the uterus is delivered, inspect and palpate it for fibroids. Identify the fundus and the position of the uterine cavity by locating both uterine cornua and imagining a straight line between them. It may be necessary to explore the endometrial cavity to look for and remove submucous fibroids. Then plan the necessary uterine incisions for removing all fibroids (see VIDEO 2).

Read about managing blood loss

4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.

Postoperative care: Manage pain, restore function

The pain pump infuser, attached to one soaker catheter above and one below the fascia, provides continuous infusion of bupivacaine to the incision at 4 mL per hour for 4 days. The pain pump greatly reduces the need for postoperative opioids.22 Use of a patient-controlled analgesia pump, with its associated adverse effects (sedation, need for oxygen saturation monitoring, slowing of bowel function) can thus be avoided. The patient’s residual pain is controlled with oral oxycodone or hydrocodone and scheduled nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

In my practice, we use an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol designed to reduce postoperative surgical stress and expedite a return to baseline physiologic body functions.23 Excellent well-researched, evidence-based studies support the effectiveness of ERAS in gynecologic and general surgery procedures.24

Pre-emptive, preoperative analgesia (gabapentin and celecoxib) and end-of-case IV acetaminophen are given to reduce the inflammatory response and the need for postoperative opioids. Once it is confirmed that the patient is hemodynamically stable, add ketorolac 30 mg IV every 6 hours on postoperative day 1. Nausea and vomiting prophylaxis includes ondansetron and dexamethasone at the end of surgery, avoidance of bowel edema with restriction of intraoperative and postoperative fluids (euvolemia), early oral feeding, and gum chewing. On the evening of surgery, the urinary catheter is removed to reduce the risk of bladder infection and facilitate ambulation. Encourage sitting at the bedside and early ambulation starting the evening of surgery to reduce risk of thromboembolism and to avoid skeletal muscle weakness and postoperative fatigue.

Most women are able to be discharged on postoperative day 2. They return to the office on postoperative day 5 for removal of the pain pump.

CASE Continued: Fibroids removed via abdominal myomectomy

We performed an abdominal myomectomy through a Pfannenstiel incision. Nine fibroids—3 of which were not seen on MRI—ranging in size from 1 to 7 cm were removed. Intravaginal misoprostol, IV tranexamic acid, subserosal vasopressin, and a uterine vessel tourniquet limited the intraoperative blood loss to 225 mL. After surgery, a pain pump and ERAS protocol allowed the patient to be discharged on postoperative day 2, and she returned to the office on day 5 for removal of the pain pump. Oral pain medication was continued on an as-needed basis.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Stanley West, MD, for generously teaching him the surgical techniques for performing abdominal myomectomy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

- Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

- Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Stocks C, Steiner CA, Myers ER. Statistical brief 200. Procedures to treat benign uterine fibroids in hospital inpatient and hospital-based ambulatory surgery settings, 2013. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb200-Procedures-Treat-Uterine-Fibroids.jsp. Published January 2016. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- Stentz NC, Cooney L, Sammel MD, Shah DK. Impact of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) safety communication on morcellation on surgical practice and perioperative morbidity following myomectomy [abstract p300]. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(3 suppl):e219.

- Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87(4):539–543.

- Pritts E, Vanness D, Berek JS, et al. The prevalence of occult leiomyosarcoma at surgery for presumed uterine fibroids: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Surg. 2015;12(3):165–177.

- Bogani G, Cliby WA, Aletti GD. Impact of morcellation on survival outcomes of patients with unexpected uterine leiomyosarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(1):167–172.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- West S, Ruiz R, Parker WH. Abdominal myomectomy in women with very large uterine size. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(1):36–39.

- Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(2):350–357.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kang SB, Kim SC, Kim YT. Safety and usefulness of intravenous iron sucrose in the management of preoperative anemia in patients with menorrhagia: a phase IV, open-label, prospective, randomized study. Acta Haematol. 2009;121(1):37–41.

- Kongnyuy EJ, Wiysonge CS. Interventions to reduce haemorrhage during myomectomy for fibroids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Aug 15;(8):CD005355.

- Hobo R, Netsu S, Koyasu Y, Tsutsumi O. Bradycardia and cardiac arrest caused by intramyometrial injection of vasopressin during a laparoscopically assisted myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2 pt 2):484–486.

- Oelsner G, Cohen SB, Soriano D, Admon D, Mashiach S, Carp H. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(12):2599–2602.

- Yasa C, Dural O, Bastu E, Zorlu M, Demir O, Ugurlucan FG. Impact of laparoscopic ovarian detorsion on ovarian reserve. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(2):298–302.

- Yamada T, Ikeda A, Okamoto Y, Okamoto Y, Kanda T, Ueki M. Intraoperative blood salvage in abdominal simple total hysterectomy for uterine myoma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):233–236.

- Discepola F, Valenti DA, Reinhold C, Tulandi T. Analysis of arterial blood vessels surrounding the myoma: relevance to myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(6):1301–1303.

- Malavasi A, Cavalotti C, Nicolardi G, et al. The opioid neuropeptides in uterine fibroid pseudocapsules: a putative association with cervical integrity in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(11):982–988.

- Walocha JA, Litwin JA, Miodonski AJ. Vascular system of intramural leiomyomata revealed by corrosion casting and scanning electron microscopy. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1088–1093.

- Tinelli A, Mynbaev OA, Sparic R, et al. Angiogenesis and vascularization of uterine leiomyoma: clinical value of pseudocapsule containing peptides and neurotransmitters [published online ahead of print March 22, 2016]. Curr Protein Pept Sci. doi:10.2174/1389203717666160322150338.

- Diamond MP. Reduction of adhesions after uterine myomectomy by Seprafilm membrane (HAL-F): a blinded, prospective, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Seprafilm Adhesion Study Group. Fertil Steril. 1996;66(6):904–910.

- Liu SS, Richman JM, Thirlby RC, Wu CL. Efficacy of continuous wound catheters delivering local anesthetic for postoperative analgesia: a quantitative and qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(6):914–932.

- Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):961–969.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):319–328.

The role of moisturizers and lubricants in genitourinary syndrome of menopause and beyond

Delivering clinician should be seated

“MANAGEMENT OF WOUND COMPLICATIONS FOLLOWING OBSTETRIC ANAL SPHINCTER INJURY (OASIS)”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD, AND JEANNINE M. MIRANNE, MD, MS (EDITORIAL; DECEMBER 2016)

Delivering clinician should be seated

Indeed, obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS),1 with their short- and long-term consequences, merit clinical attention, as spotlighted in Dr. Barbieri and Dr. Miranne’s article. An issue not discussed is the position of the obstetrician.

In our practice, we sit down to perform a vaginal delivery, as taught by Soranus of Ephesus.2 We strive to be at the bedside sooner than when the nurse calls “she is crowning.” This allows communication with the woman, attending nurse, and support person(s), as well as for a brief review of recent estimated fetal weight, length of the second stage, position of the presenting part, degree of flexion, presence of caput, and other last-minute details. Sitting down in front of the outlet permits uninterrupted visual evaluation of the distention of the soft perineal tissues. All traditional maneuvers are performed comfortably from the sitting position: the vertex is controlled by hands-on, and a quick reach with the nonpredominant hand searches for a loop of cord or a small part procidentia to resolve it. The patient is coached either for the next bearing-down effort or to not push to allow for gradual, controlled delivery of the fetal shoulder girdle. We avoid use of the fetal head for traction and move to facilitate “shrugging” with reduction of the bisacromial to facilitate delivery.

In our experience, the sitting position is ideal to observe uninterruptedly the tension of the perineal body during vertex and shoulders delivery, without having to flex and rotate our back and neck in repeatedly nonergonomic positions.

If an obstetrician of above-average height stands for the delivery, the obstetric bed should be elevated to fit her or his reach. Should shoulder dystocia occur, an assistant will stand on a chair and hover over the maternal abdomen to provide suprapubic pressure (indeed, an indelible memory for any parturient and her family). From the sitting position, exploration of the birth canal and repair of any injury, if necessary, can be conducted without technical impediments.

These simple steps have provided our patients and ourselves with clinical and professional satisfaction with minimal OASIS events as shown by others.3 Ironically, if we successfully avoid perineal injuries, our young trainees may require simulation training to learn this tedious repair procedure. In our geographic practice area, a new “collaborative” expects the frequency of episiotomy to be less than 4.6%. Third- and 4th-degree spontaneous or procedure-related perineal injuries still are used to measure quality of care despite demonstrated reasons for this parameter to be a noncredible metric.

Federico G. Mariona, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Mariona that in some cases the fetal head delivers without causing a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration, but then the delivery of the posterior shoulder causes a severe perineal injury. Dr. Mariona’s clinical pearl is that the delivering clinician should be seated, carefully observe the delivery of the shoulders, and facilitate fetal shrugging by gently reducing the bisacromial diameter as the posterior shoulder transitions over the perineal body.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Verghese TS, Champaneria R, Kapoor DS, Latthe PM. Obstetric anal sphincter injuries after episiotomy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(10):1459–1467.

- Drife J. The start of life: a history of obstetrics. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78(919):311–315.

- Basu M, Smith D, Edwards R; STOMP Project Team. Can the incidence of obstetric anal sphincter injury be reduced? The STOMP experience. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;202:55–59.

“MANAGEMENT OF WOUND COMPLICATIONS FOLLOWING OBSTETRIC ANAL SPHINCTER INJURY (OASIS)”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD, AND JEANNINE M. MIRANNE, MD, MS (EDITORIAL; DECEMBER 2016)

Delivering clinician should be seated

Indeed, obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS),1 with their short- and long-term consequences, merit clinical attention, as spotlighted in Dr. Barbieri and Dr. Miranne’s article. An issue not discussed is the position of the obstetrician.

In our practice, we sit down to perform a vaginal delivery, as taught by Soranus of Ephesus.2 We strive to be at the bedside sooner than when the nurse calls “she is crowning.” This allows communication with the woman, attending nurse, and support person(s), as well as for a brief review of recent estimated fetal weight, length of the second stage, position of the presenting part, degree of flexion, presence of caput, and other last-minute details. Sitting down in front of the outlet permits uninterrupted visual evaluation of the distention of the soft perineal tissues. All traditional maneuvers are performed comfortably from the sitting position: the vertex is controlled by hands-on, and a quick reach with the nonpredominant hand searches for a loop of cord or a small part procidentia to resolve it. The patient is coached either for the next bearing-down effort or to not push to allow for gradual, controlled delivery of the fetal shoulder girdle. We avoid use of the fetal head for traction and move to facilitate “shrugging” with reduction of the bisacromial to facilitate delivery.

In our experience, the sitting position is ideal to observe uninterruptedly the tension of the perineal body during vertex and shoulders delivery, without having to flex and rotate our back and neck in repeatedly nonergonomic positions.

If an obstetrician of above-average height stands for the delivery, the obstetric bed should be elevated to fit her or his reach. Should shoulder dystocia occur, an assistant will stand on a chair and hover over the maternal abdomen to provide suprapubic pressure (indeed, an indelible memory for any parturient and her family). From the sitting position, exploration of the birth canal and repair of any injury, if necessary, can be conducted without technical impediments.

These simple steps have provided our patients and ourselves with clinical and professional satisfaction with minimal OASIS events as shown by others.3 Ironically, if we successfully avoid perineal injuries, our young trainees may require simulation training to learn this tedious repair procedure. In our geographic practice area, a new “collaborative” expects the frequency of episiotomy to be less than 4.6%. Third- and 4th-degree spontaneous or procedure-related perineal injuries still are used to measure quality of care despite demonstrated reasons for this parameter to be a noncredible metric.

Federico G. Mariona, MD

Dearborn, Michigan

Dr. Barbieri responds

I agree with Dr. Mariona that in some cases the fetal head delivers without causing a 3rd- or 4th-degree laceration, but then the delivery of the posterior shoulder causes a severe perineal injury. Dr. Mariona’s clinical pearl is that the delivering clinician should be seated, carefully observe the delivery of the shoulders, and facilitate fetal shrugging by gently reducing the bisacromial diameter as the posterior shoulder transitions over the perineal body.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“MANAGEMENT OF WOUND COMPLICATIONS FOLLOWING OBSTETRIC ANAL SPHINCTER INJURY (OASIS)”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD, AND JEANNINE M. MIRANNE, MD, MS (EDITORIAL; DECEMBER 2016)

Delivering clinician should be seated

Indeed, obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS),1 with their short- and long-term consequences, merit clinical attention, as spotlighted in Dr. Barbieri and Dr. Miranne’s article. An issue not discussed is the position of the obstetrician.