User login

VIDEO: Public reporting of congenital heart disease outcomes should be easily understood

HOUSTON – Survival statistics, surgeon-specific experience, and complication rates are the types of information most sought by parents of children with congenital heart disease, results from a large survey suggest.

Future efforts in public reporting for congenital heart surgery outcomes should have better methods for presenting the data in a valid, easily interpreted format, explained study investigator Mallory L. Irons, MD, an integrated cardiac surgery resident at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“We’re doing a good job of public reporting currently, but what we’re doing is not meeting the needs of all of our stakeholders – in this case, the parents of children with congenital heart disease,” Dr. Irons said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “The optimal public reporting scheme still has yet to be determined.”

Dr. Irons reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

HOUSTON – Survival statistics, surgeon-specific experience, and complication rates are the types of information most sought by parents of children with congenital heart disease, results from a large survey suggest.

Future efforts in public reporting for congenital heart surgery outcomes should have better methods for presenting the data in a valid, easily interpreted format, explained study investigator Mallory L. Irons, MD, an integrated cardiac surgery resident at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“We’re doing a good job of public reporting currently, but what we’re doing is not meeting the needs of all of our stakeholders – in this case, the parents of children with congenital heart disease,” Dr. Irons said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “The optimal public reporting scheme still has yet to be determined.”

Dr. Irons reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

HOUSTON – Survival statistics, surgeon-specific experience, and complication rates are the types of information most sought by parents of children with congenital heart disease, results from a large survey suggest.

Future efforts in public reporting for congenital heart surgery outcomes should have better methods for presenting the data in a valid, easily interpreted format, explained study investigator Mallory L. Irons, MD, an integrated cardiac surgery resident at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“We’re doing a good job of public reporting currently, but what we’re doing is not meeting the needs of all of our stakeholders – in this case, the parents of children with congenital heart disease,” Dr. Irons said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. “The optimal public reporting scheme still has yet to be determined.”

Dr. Irons reported having no financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

FROM THE STS ANNUAL MEETING HOUSTON

After TAVR, 1 in 10 Medicare patients need permanent pacemaker

HOUSTON – About 1 in 10 Medicare patients require implantation of a permanent pacemaker following transcatheter aortic valve replacement, results from a large analysis showed.

“There is conflicting evidence and some debate over permanent pacemaker placement following transcatheter aortic valve replacement – whether it has a protective or adverse effect, and how often it takes place,” study investigator Fenton H. McCarthy, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

One recent study found that permanent pacemaker placement within 30 days post TAVR was found in 6.7% of patients undergoing balloon-expanding or self-expanding valve implantation, and is associated with increased mortality and hospitalizations (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Nov 14;9[21]:2189-2199).

To evaluate the relationship between permanent pacemaker implantation and long-term patient outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing TAVR, Dr. McCarthy, a cardiothoracic surgery fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates used Medicare carrier claims and Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files to identify 14,305 TAVR patients between January 2011 and December 2013.

The researchers used univariate Kaplan survival estimates and multivariable models to analyze survival, readmission and risk factors for pacemaker implantation.

The mean age of the 14,305 TAVR patients studied was 83 years, and 11% received a permanent pacemaker after TAVR. Of these, 9% received the pacemaker at index hospitalization, 1% at 30 days after implant, 0.5% at 90 days after implant, and 1% at 1 year after implant. Patient age of greater than 90 years was a significant predictor of pacemaker placement, with an odds ratio of 1.7 (P less than .01).

Dr. McCarthy and his associates observed that the readmission rates for pacemaker placement and no pacemaker placement at index hospitalization were similar at 30 days (21% vs. 19%, respectively), at 90 days (33% vs. 31%) and at 1 year (43% in both groups of patients).

In addition, Kaplan Meier estimates revealed no significant difference in long-term survival for patients with pacemaker placement within 30 days of TAVR, while multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling revealed that pacemaker placement is not a predictor of long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .65).

“This was the largest study to evaluate the question of incidence and effect of permanent pacemaker in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement population in the United States,” Dr. McCarthy said. “The size of our data set and the fact that the Medicare database includes all types of patients, regardless of trial participation, study or registry, is a strength of this study. Some other studies have used different inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used broad inclusion criteria and evaluated patients from as many different centers as possible.”

A key limitation of the study, he said, was that the researchers were unable to determine whether a patient received a balloon-expanding or self-expanding TAVR.

Dr. McCarthy reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About 1 in 10 Medicare patients require implantation of a permanent pacemaker following transcatheter aortic valve replacement, results from a large analysis showed.

“There is conflicting evidence and some debate over permanent pacemaker placement following transcatheter aortic valve replacement – whether it has a protective or adverse effect, and how often it takes place,” study investigator Fenton H. McCarthy, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

One recent study found that permanent pacemaker placement within 30 days post TAVR was found in 6.7% of patients undergoing balloon-expanding or self-expanding valve implantation, and is associated with increased mortality and hospitalizations (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Nov 14;9[21]:2189-2199).

To evaluate the relationship between permanent pacemaker implantation and long-term patient outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing TAVR, Dr. McCarthy, a cardiothoracic surgery fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates used Medicare carrier claims and Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files to identify 14,305 TAVR patients between January 2011 and December 2013.

The researchers used univariate Kaplan survival estimates and multivariable models to analyze survival, readmission and risk factors for pacemaker implantation.

The mean age of the 14,305 TAVR patients studied was 83 years, and 11% received a permanent pacemaker after TAVR. Of these, 9% received the pacemaker at index hospitalization, 1% at 30 days after implant, 0.5% at 90 days after implant, and 1% at 1 year after implant. Patient age of greater than 90 years was a significant predictor of pacemaker placement, with an odds ratio of 1.7 (P less than .01).

Dr. McCarthy and his associates observed that the readmission rates for pacemaker placement and no pacemaker placement at index hospitalization were similar at 30 days (21% vs. 19%, respectively), at 90 days (33% vs. 31%) and at 1 year (43% in both groups of patients).

In addition, Kaplan Meier estimates revealed no significant difference in long-term survival for patients with pacemaker placement within 30 days of TAVR, while multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling revealed that pacemaker placement is not a predictor of long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .65).

“This was the largest study to evaluate the question of incidence and effect of permanent pacemaker in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement population in the United States,” Dr. McCarthy said. “The size of our data set and the fact that the Medicare database includes all types of patients, regardless of trial participation, study or registry, is a strength of this study. Some other studies have used different inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used broad inclusion criteria and evaluated patients from as many different centers as possible.”

A key limitation of the study, he said, was that the researchers were unable to determine whether a patient received a balloon-expanding or self-expanding TAVR.

Dr. McCarthy reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About 1 in 10 Medicare patients require implantation of a permanent pacemaker following transcatheter aortic valve replacement, results from a large analysis showed.

“There is conflicting evidence and some debate over permanent pacemaker placement following transcatheter aortic valve replacement – whether it has a protective or adverse effect, and how often it takes place,” study investigator Fenton H. McCarthy, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

One recent study found that permanent pacemaker placement within 30 days post TAVR was found in 6.7% of patients undergoing balloon-expanding or self-expanding valve implantation, and is associated with increased mortality and hospitalizations (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Nov 14;9[21]:2189-2199).

To evaluate the relationship between permanent pacemaker implantation and long-term patient outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries undergoing TAVR, Dr. McCarthy, a cardiothoracic surgery fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his associates used Medicare carrier claims and Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files to identify 14,305 TAVR patients between January 2011 and December 2013.

The researchers used univariate Kaplan survival estimates and multivariable models to analyze survival, readmission and risk factors for pacemaker implantation.

The mean age of the 14,305 TAVR patients studied was 83 years, and 11% received a permanent pacemaker after TAVR. Of these, 9% received the pacemaker at index hospitalization, 1% at 30 days after implant, 0.5% at 90 days after implant, and 1% at 1 year after implant. Patient age of greater than 90 years was a significant predictor of pacemaker placement, with an odds ratio of 1.7 (P less than .01).

Dr. McCarthy and his associates observed that the readmission rates for pacemaker placement and no pacemaker placement at index hospitalization were similar at 30 days (21% vs. 19%, respectively), at 90 days (33% vs. 31%) and at 1 year (43% in both groups of patients).

In addition, Kaplan Meier estimates revealed no significant difference in long-term survival for patients with pacemaker placement within 30 days of TAVR, while multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling revealed that pacemaker placement is not a predictor of long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .65).

“This was the largest study to evaluate the question of incidence and effect of permanent pacemaker in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement population in the United States,” Dr. McCarthy said. “The size of our data set and the fact that the Medicare database includes all types of patients, regardless of trial participation, study or registry, is a strength of this study. Some other studies have used different inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used broad inclusion criteria and evaluated patients from as many different centers as possible.”

A key limitation of the study, he said, was that the researchers were unable to determine whether a patient received a balloon-expanding or self-expanding TAVR.

Dr. McCarthy reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Pacemaker placement is not a predictor of long-term mortality (hazard ratio, 1.03; P = .65).

Data source: A study of 14,305 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent TAVR between January 2011 and December 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. McCarthy reported having no financial disclosures.

7 Myomectomy myths debunked

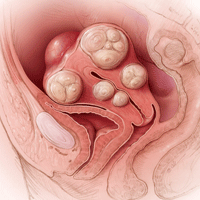

Fibroids are extremely common and can be detected in 60% of African American women and 40% of white women by age 35. By age 50, more than 80% of African American women and almost 70% of white women have fibroids. Although most women with fibroids are relatively asymptomatic, women who have bothersome symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, or pain, account for nearly 30% of all gynecologic admissions in the United States. The cost of fibroid-related care, including surgery, hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and medications, is estimated at $4 to $9 billion per year.1 In addition, each woman seeking treatment for fibroid-related symptoms incurs an expense of $4,500 to $30,000 for lost work or disability every year.1

Many treatment options, including medical therapy and noninvasive procedures, are now available for women with symptomatic fibroids. For women who require surgical treatment, however, hysterectomy is often recommended. Fibroid-related hysterectomy currently accounts for 45% of all hysterectomies, or approximately 195,700 per year. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical management guidelines state that myomectomy is a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of women with symptomatic fibroids, only 30,000 myomectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches) are performed each year.2 Why is this? One reason may be that, although many women wish to have uterus-preserving treatment, they often feel that doctors are too quick to recommend hysterectomy as the first—and sometimes only—treatment option for fibroids.3

CASE: Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for a third opinion regarding her heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy. Both her regular gynecologist and the second gynecologist she consulted recommended hysterectomy as the first, and only, treatment option. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. The patient’s other gynecologists advised her that a myomectomy would be a “bloody operation,” would leave her uterus looking like Swiss cheese, and is not appropriate for women who have completed childbearing.

The patient asks if myomectomy could be considered in her situation. How would you advise her regarding myomectomy as an alternative to hysterectomy?

Organ conservation is important

In 1931, prominent British gynecologic surgeon Victor Bonney said, “Since cure without deformity or loss of function must ever be surgery’s highest ideal, the general proposition that myomectomy is a greater surgical achievement is incontestable.”4 As current hysterectomy and myomectomy rates indicate, however, we are not attempting organ conservation very often.

Other specialties almost never remove an entire organ for benign growths. Using breast cancer surgery as an admirable paradigm, consider that in the early 20th century the standard treatment for breast cancer was a Halsted radical mastectomy with axial lymphadenectomy. By the 1930s, this disfiguring operation was replaced by simple mastectomy and radiation, and by the 1970s, by lumpectomy and lymphadenectomy. Currently, lumpectomy and sentinel node sampling is the standard of care for early stage breast cancer. This is an excellent example of “minimally invasive surgery,” a term fostered by gynecologists. And, these organ-preservingsurgeries are performed for women with cancer, not a benign condition like fibroids.

Although our approach to hysterectomy has evolved with the increasing use of laparoscopic or robotic assistance, removal of the entire uterus nevertheless remains the surgical goal. I think this narrow view of surgical options is a disservice to our patients.

Many of us were taught that myomectomy was associated with more complications and more blood loss than hysterectomy. We were taught that the uterus had no function other than childbearing and that removing the uterus had no adverse health effects. The dogma suggested that myomectomy preserved a uterus that looked like Swiss cheese and would not heal properly and that the risk of fibroid recurrence was high. These beliefs, however, are myths, which are discussed and debunked below. In second and third installments for this series on myomectomy, I present steps for successful abdominal and laparoscopic technique.

Read myths on hysterectomy, myomectomy, and fibroids

MYTH #1: Hysterectomy is safer than myomectomy

Myomectomy is performed within the confines of the uterus and myometrium, with only infrequent occasion to operate near the ureters, uterine vessels, bowel, or bladder. Therefore, it should not be surprising that studies show that fewer complications occur with myomectomy than with hysterectomy.

A retrospective review of 197 women who had myomectomy and 197 women who underwent hysterectomy with similar uterine size (14 vs 15 weeks) reported that 13% (n = 26) of women in the hysterectomy group experienced complications, including 1 bladder injury, 1 ureteral injury, and 3 bowel injuries; 8 women had an ileus and 6 women had a pelvic abscess.5 Only 5% (n = 11) of the myomectomy patients had complications, including 1 bladder injury; 2 women had reoperation for small bowel obstruction, and 6 women had an ileus. The risks of febrile morbidity, unintended surgical procedure, life-threatening events, and rehospitalization were similar for both groups.

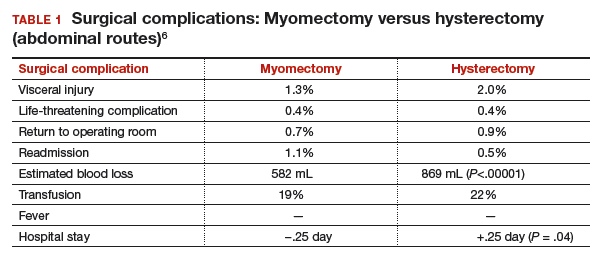

Authors of a recent systematic review of 6 studies, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 18 weeks, found higher rates of visceral injury and longer hospital stays for women who had a hysterectomy compared with those who had a myomectomy (TABLE 1).6

MYTH #2: Myomectomy is associated with more surgical blood loss than hysterectomy

In the previously cited study of 197 women treated with myomectomy and 197 women treated with hysterectomy, the estimated blood loss was greater in the hysterectomy group (484 mL) than in the myomectomy group (227 mL). When uterine size was corrected for, blood loss was no greater for myomectomy than for hysterectomy.5 The risk of hemorrhage (>500 mL blood loss) was greater in the hysterectomy group (14.2% vs 9.6%). Authors of the recent meta-analysis also found that the rate of transfusion was higher in the hysterectomy cohort. Tourniquets, misoprostol, vasopressin, and tranexamic acid all have been shown to significantly decrease surgical blood loss. (These treatments will be discussed in the next installment of this article series.)

MYTH #3: A uterus will look like Swiss cheese after a myomectomy

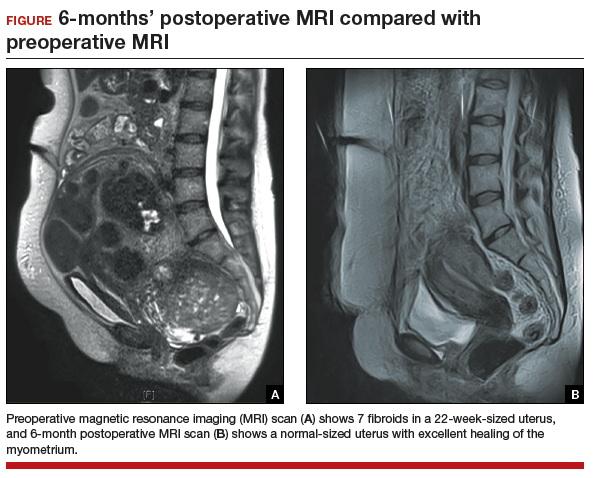

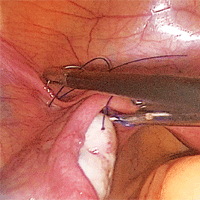

The uterus heals remarkably well after myomectomy. Three months following laparoscopic myomectomy, 3-dimensional Doppler ultrasonography demonstrated complete myometrial healing and normal blood flow to the uterus.7 In a study of women undergoing abdominal myomectomy, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showed complete healing of the myometrium and normal myometrial perfusion by 3 months.8 This study also found that, after removal of 65 g to 380 g of fibroids, the uterine volume 3 months after surgery was 65 mL, essentially equivalent to the normal volume of a uterus without fibroids (57 mL).8 See FIGURE for MRI scans of the uterus before and after myomectomy.

MYTH #4: Fibroids will just grow back after myomectomy

Once a fibroid is completely removed surgically, it does not grow back. The risk of new fibroid growth depends on the number of fibroids originally removed and the amount of time until menopause, when fibroids reduce in size and symptoms usually resolve. Given that the prevalence of fibroids is nearly 80% by age 50, studies measuring the detection of new fibroid growth of 1 cm on ultrasound imaging overstate the problem.9 What is likely a more important consideration for women is whether, following myomectomy, they will need another procedure for new fibroid-related symptoms.

Results of a meta-analysis of 872 women in 7 studies with 10- to 25-year follow-up indicated that 89% of women did not require another surgery.10 In another study, authors found that, over an average follow-up of 7.6 years, a second surgery occurred in 11% of the women who had 1 fibroid initially removed and for 26% of women who had multiple fibroids initially removed.11 In another study of 92 women who had either abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy after age 45and who were followed for an average of 30 months, only 1 woman (1%) required a hysterectomy for fibroid-related symptoms.12 That patient had growth of a fibroid that was present but was not removed at her initial laparoscopic myomectomy.

Read myths 5–7 on ovarian conservation, fibroid growth, and symptom improvement

MYTH #5: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation does not change hormone levels

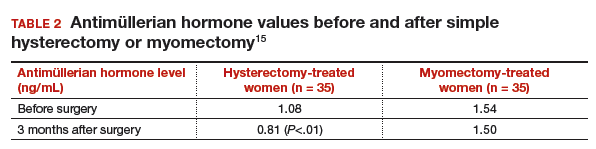

Following hysterectomy with ovarian conservation, some women begin menopause earlier than age-matched women who have not undergone any surgery.13 Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation prior to age 50 has been associated with a significant increase in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.14 In a prospective longitudinal study, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) levels were persistently decreased following hysterectomy despite ovarian conservation.15 However, 3 months after myomectomy, no such changes in AMH levels were seen (TABLE 2).15

Early natural menopause has been associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease and death, and bilateral oophorectomy has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, lung cancer, colon cancer, anxiety, and depression. Although taking estrogen might obviate these adverse health effects, the majority of women who receive a prescription for estrogen following surgery are no longer taking it 5 years later.

MYTH #6: Fibroid growth in a premenopausal patient means cancer may be present

While most fibroids grow slowly, rapid growth of benign fibroids is very common. Using computerized analysis of a group of 72 women having serial MRI scans, investigators found that 34% of benign fibroids increased more than 20% in volume over 6 months.16 In premenopausal women, “rapid uterine growth” almost never indicates presence of uterine sarcoma. One study reported only 1 sarcoma among 371 women operated on for rapid growth of presumed fibroids.17 Using current criteria from the World Health Organization to determine the pathologic diagnosis, however, that 1 woman was determined to have had an atypical leiomyoma. Therefore, the prevalence of leiomyosarcoma in that study approached zero. In addition, in the 198 women who had a 6-week increase in uterine size over 1 year (one published definition of rapid growth), no sarcomas were found.17

Because of recent concern about leiomyosarcoma and morcellation of fibroids, some gynecologists have reverted to advising women that growing fibroids might be cancer and that hysterectomy is recommended. However, there is no evidence that fibroid growth is a sign of leiomyosarcoma in premenopausal women. Leiomyosarcoma should strongly be considered in a postmenopausal woman on no hormone therapy who has growth of a presumed fibroid.

MYTH #7: Myomectomy will not improve symptoms

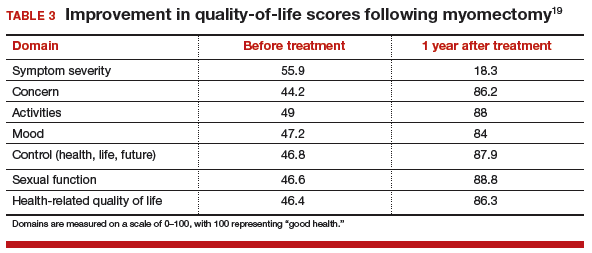

Fibroid-related symptoms can be significant; women who undergo hysterectomy because of fibroid-related symptoms have significantly worse scores on the 36-Item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) quality-of-life questionnaire than women diagnosed with hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease, or arthritis.18

For women with fibroid-related symptoms, myomectomy has been shown to improve quality of life. A study of 72 women showed that SF-36 scores improved significantly following myomectomy (TABLE 3, page 48).19 In another study that used the European Quality of Life Five-Dimension Scale and Visual Analog Scale, 95 women had significant improvement in quality of life (P<.001) following laparoscopic myomectomy.20

For some women, hysterectomy may have an impact on emotional quality of life. Some women report decreased sexual desire after hysterectomy. They worry that partners will see them as “not whole” and less desirable. Some women expect that hysterectomy will lead to depression, crying, lack of sexual desire, and vaginal dryness.21 No such changes have been reported for women having myomectomy.

CASE Continued: Third consult leads patient to schedule surgical procedure

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, examination, and ultrasound results, we advise the patient that abdominal myomectomy is indeed appropriate and feasible in her case. She schedules surgery for the following month.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211.e1–e9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387–400.

- Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Stewart EA. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):319.e1–e20.

- Bonney V. The technique and results of myomectomy. Lancet. 1931;217(5604):171-177.

- Sawin SW, Pilevsky ND, Berlin JA, Barnhart KT. Comparability of perioperative morbidity between abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy for women with uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1448–1455.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- Chang WC, Chang DY, Huang SC, et al. Use of three-dimensional ultrasonography in the evaluation of uterine perfusion and healing after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1110–1115.

- Tsuji S, Takahashi K, Imaoka I, Sugimura K, Miyazaki K, Noda Y. MRI evaluation of the uterine structure after myomectomy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(2):106–110.

- Sudik R, Husch K, Steller J, Daume E. Fertility and pregnancy outcome after myomectomy in sterility patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65(2):209–214.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Babaki-Fard K, Dubuisson JB. Recurrence of leiomyomata after myomectomy. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(6):595–602.

- Malone, LJ. Myomectomy: recurrence after removal of solitary and multiple myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;34(2):200–203.

- Kim DH, Kim ML, Song T, Kim MK, Yoon BS, Seong SJ. Is myomectomy in women aged 45 years and older an effective option? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:57–60.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, Stewart AW. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112(7):956–962.

- Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(6):745–750.

- Wang HY, Quan S, Zhang RL, et al. Comparison of serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels following hysterectomy and myomectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(2):368–371.

- Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(50):19887–19892.

- Parker W, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(3):414–418.

- Rowe MK, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, Bernstein SJ. Quality of life among women undergoing hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(6):915–921.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Radosa JC, Radosa CG, Mavrova R, et al. Postoperative quality of life and sexual function in premenopausal women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic fibroids: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;29;11(11):e0166659.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, Shelton AJ, Lees E, Goode J. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(suppl 2):39S–50S.

Fibroids are extremely common and can be detected in 60% of African American women and 40% of white women by age 35. By age 50, more than 80% of African American women and almost 70% of white women have fibroids. Although most women with fibroids are relatively asymptomatic, women who have bothersome symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, or pain, account for nearly 30% of all gynecologic admissions in the United States. The cost of fibroid-related care, including surgery, hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and medications, is estimated at $4 to $9 billion per year.1 In addition, each woman seeking treatment for fibroid-related symptoms incurs an expense of $4,500 to $30,000 for lost work or disability every year.1

Many treatment options, including medical therapy and noninvasive procedures, are now available for women with symptomatic fibroids. For women who require surgical treatment, however, hysterectomy is often recommended. Fibroid-related hysterectomy currently accounts for 45% of all hysterectomies, or approximately 195,700 per year. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical management guidelines state that myomectomy is a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of women with symptomatic fibroids, only 30,000 myomectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches) are performed each year.2 Why is this? One reason may be that, although many women wish to have uterus-preserving treatment, they often feel that doctors are too quick to recommend hysterectomy as the first—and sometimes only—treatment option for fibroids.3

CASE: Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for a third opinion regarding her heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy. Both her regular gynecologist and the second gynecologist she consulted recommended hysterectomy as the first, and only, treatment option. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. The patient’s other gynecologists advised her that a myomectomy would be a “bloody operation,” would leave her uterus looking like Swiss cheese, and is not appropriate for women who have completed childbearing.

The patient asks if myomectomy could be considered in her situation. How would you advise her regarding myomectomy as an alternative to hysterectomy?

Organ conservation is important

In 1931, prominent British gynecologic surgeon Victor Bonney said, “Since cure without deformity or loss of function must ever be surgery’s highest ideal, the general proposition that myomectomy is a greater surgical achievement is incontestable.”4 As current hysterectomy and myomectomy rates indicate, however, we are not attempting organ conservation very often.

Other specialties almost never remove an entire organ for benign growths. Using breast cancer surgery as an admirable paradigm, consider that in the early 20th century the standard treatment for breast cancer was a Halsted radical mastectomy with axial lymphadenectomy. By the 1930s, this disfiguring operation was replaced by simple mastectomy and radiation, and by the 1970s, by lumpectomy and lymphadenectomy. Currently, lumpectomy and sentinel node sampling is the standard of care for early stage breast cancer. This is an excellent example of “minimally invasive surgery,” a term fostered by gynecologists. And, these organ-preservingsurgeries are performed for women with cancer, not a benign condition like fibroids.

Although our approach to hysterectomy has evolved with the increasing use of laparoscopic or robotic assistance, removal of the entire uterus nevertheless remains the surgical goal. I think this narrow view of surgical options is a disservice to our patients.

Many of us were taught that myomectomy was associated with more complications and more blood loss than hysterectomy. We were taught that the uterus had no function other than childbearing and that removing the uterus had no adverse health effects. The dogma suggested that myomectomy preserved a uterus that looked like Swiss cheese and would not heal properly and that the risk of fibroid recurrence was high. These beliefs, however, are myths, which are discussed and debunked below. In second and third installments for this series on myomectomy, I present steps for successful abdominal and laparoscopic technique.

Read myths on hysterectomy, myomectomy, and fibroids

MYTH #1: Hysterectomy is safer than myomectomy

Myomectomy is performed within the confines of the uterus and myometrium, with only infrequent occasion to operate near the ureters, uterine vessels, bowel, or bladder. Therefore, it should not be surprising that studies show that fewer complications occur with myomectomy than with hysterectomy.

A retrospective review of 197 women who had myomectomy and 197 women who underwent hysterectomy with similar uterine size (14 vs 15 weeks) reported that 13% (n = 26) of women in the hysterectomy group experienced complications, including 1 bladder injury, 1 ureteral injury, and 3 bowel injuries; 8 women had an ileus and 6 women had a pelvic abscess.5 Only 5% (n = 11) of the myomectomy patients had complications, including 1 bladder injury; 2 women had reoperation for small bowel obstruction, and 6 women had an ileus. The risks of febrile morbidity, unintended surgical procedure, life-threatening events, and rehospitalization were similar for both groups.

Authors of a recent systematic review of 6 studies, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 18 weeks, found higher rates of visceral injury and longer hospital stays for women who had a hysterectomy compared with those who had a myomectomy (TABLE 1).6

MYTH #2: Myomectomy is associated with more surgical blood loss than hysterectomy

In the previously cited study of 197 women treated with myomectomy and 197 women treated with hysterectomy, the estimated blood loss was greater in the hysterectomy group (484 mL) than in the myomectomy group (227 mL). When uterine size was corrected for, blood loss was no greater for myomectomy than for hysterectomy.5 The risk of hemorrhage (>500 mL blood loss) was greater in the hysterectomy group (14.2% vs 9.6%). Authors of the recent meta-analysis also found that the rate of transfusion was higher in the hysterectomy cohort. Tourniquets, misoprostol, vasopressin, and tranexamic acid all have been shown to significantly decrease surgical blood loss. (These treatments will be discussed in the next installment of this article series.)

MYTH #3: A uterus will look like Swiss cheese after a myomectomy

The uterus heals remarkably well after myomectomy. Three months following laparoscopic myomectomy, 3-dimensional Doppler ultrasonography demonstrated complete myometrial healing and normal blood flow to the uterus.7 In a study of women undergoing abdominal myomectomy, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showed complete healing of the myometrium and normal myometrial perfusion by 3 months.8 This study also found that, after removal of 65 g to 380 g of fibroids, the uterine volume 3 months after surgery was 65 mL, essentially equivalent to the normal volume of a uterus without fibroids (57 mL).8 See FIGURE for MRI scans of the uterus before and after myomectomy.

MYTH #4: Fibroids will just grow back after myomectomy

Once a fibroid is completely removed surgically, it does not grow back. The risk of new fibroid growth depends on the number of fibroids originally removed and the amount of time until menopause, when fibroids reduce in size and symptoms usually resolve. Given that the prevalence of fibroids is nearly 80% by age 50, studies measuring the detection of new fibroid growth of 1 cm on ultrasound imaging overstate the problem.9 What is likely a more important consideration for women is whether, following myomectomy, they will need another procedure for new fibroid-related symptoms.

Results of a meta-analysis of 872 women in 7 studies with 10- to 25-year follow-up indicated that 89% of women did not require another surgery.10 In another study, authors found that, over an average follow-up of 7.6 years, a second surgery occurred in 11% of the women who had 1 fibroid initially removed and for 26% of women who had multiple fibroids initially removed.11 In another study of 92 women who had either abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy after age 45and who were followed for an average of 30 months, only 1 woman (1%) required a hysterectomy for fibroid-related symptoms.12 That patient had growth of a fibroid that was present but was not removed at her initial laparoscopic myomectomy.

Read myths 5–7 on ovarian conservation, fibroid growth, and symptom improvement

MYTH #5: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation does not change hormone levels

Following hysterectomy with ovarian conservation, some women begin menopause earlier than age-matched women who have not undergone any surgery.13 Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation prior to age 50 has been associated with a significant increase in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.14 In a prospective longitudinal study, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) levels were persistently decreased following hysterectomy despite ovarian conservation.15 However, 3 months after myomectomy, no such changes in AMH levels were seen (TABLE 2).15

Early natural menopause has been associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease and death, and bilateral oophorectomy has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, lung cancer, colon cancer, anxiety, and depression. Although taking estrogen might obviate these adverse health effects, the majority of women who receive a prescription for estrogen following surgery are no longer taking it 5 years later.

MYTH #6: Fibroid growth in a premenopausal patient means cancer may be present

While most fibroids grow slowly, rapid growth of benign fibroids is very common. Using computerized analysis of a group of 72 women having serial MRI scans, investigators found that 34% of benign fibroids increased more than 20% in volume over 6 months.16 In premenopausal women, “rapid uterine growth” almost never indicates presence of uterine sarcoma. One study reported only 1 sarcoma among 371 women operated on for rapid growth of presumed fibroids.17 Using current criteria from the World Health Organization to determine the pathologic diagnosis, however, that 1 woman was determined to have had an atypical leiomyoma. Therefore, the prevalence of leiomyosarcoma in that study approached zero. In addition, in the 198 women who had a 6-week increase in uterine size over 1 year (one published definition of rapid growth), no sarcomas were found.17

Because of recent concern about leiomyosarcoma and morcellation of fibroids, some gynecologists have reverted to advising women that growing fibroids might be cancer and that hysterectomy is recommended. However, there is no evidence that fibroid growth is a sign of leiomyosarcoma in premenopausal women. Leiomyosarcoma should strongly be considered in a postmenopausal woman on no hormone therapy who has growth of a presumed fibroid.

MYTH #7: Myomectomy will not improve symptoms

Fibroid-related symptoms can be significant; women who undergo hysterectomy because of fibroid-related symptoms have significantly worse scores on the 36-Item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) quality-of-life questionnaire than women diagnosed with hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease, or arthritis.18

For women with fibroid-related symptoms, myomectomy has been shown to improve quality of life. A study of 72 women showed that SF-36 scores improved significantly following myomectomy (TABLE 3, page 48).19 In another study that used the European Quality of Life Five-Dimension Scale and Visual Analog Scale, 95 women had significant improvement in quality of life (P<.001) following laparoscopic myomectomy.20

For some women, hysterectomy may have an impact on emotional quality of life. Some women report decreased sexual desire after hysterectomy. They worry that partners will see them as “not whole” and less desirable. Some women expect that hysterectomy will lead to depression, crying, lack of sexual desire, and vaginal dryness.21 No such changes have been reported for women having myomectomy.

CASE Continued: Third consult leads patient to schedule surgical procedure

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, examination, and ultrasound results, we advise the patient that abdominal myomectomy is indeed appropriate and feasible in her case. She schedules surgery for the following month.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Fibroids are extremely common and can be detected in 60% of African American women and 40% of white women by age 35. By age 50, more than 80% of African American women and almost 70% of white women have fibroids. Although most women with fibroids are relatively asymptomatic, women who have bothersome symptoms, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, urinary frequency, pelvic or abdominal pressure, or pain, account for nearly 30% of all gynecologic admissions in the United States. The cost of fibroid-related care, including surgery, hospital admissions, outpatient visits, and medications, is estimated at $4 to $9 billion per year.1 In addition, each woman seeking treatment for fibroid-related symptoms incurs an expense of $4,500 to $30,000 for lost work or disability every year.1

Many treatment options, including medical therapy and noninvasive procedures, are now available for women with symptomatic fibroids. For women who require surgical treatment, however, hysterectomy is often recommended. Fibroid-related hysterectomy currently accounts for 45% of all hysterectomies, or approximately 195,700 per year. Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) clinical management guidelines state that myomectomy is a safe and effective alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of women with symptomatic fibroids, only 30,000 myomectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches) are performed each year.2 Why is this? One reason may be that, although many women wish to have uterus-preserving treatment, they often feel that doctors are too quick to recommend hysterectomy as the first—and sometimes only—treatment option for fibroids.3

CASE: Woman with fibroids seeks alternative to hysterectomy

A 42-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for a third opinion regarding her heavy menstrual bleeding and known uterine fibroids. She does not want to have any more children, but she wishes to avoid a hysterectomy. Both her regular gynecologist and the second gynecologist she consulted recommended hysterectomy as the first, and only, treatment option. Physical examination reveals a 16-week-sized uterus, and ultrasonography shows at least 6 fibroids, 2 of which impinge on the uterine cavity. The patient’s other gynecologists advised her that a myomectomy would be a “bloody operation,” would leave her uterus looking like Swiss cheese, and is not appropriate for women who have completed childbearing.

The patient asks if myomectomy could be considered in her situation. How would you advise her regarding myomectomy as an alternative to hysterectomy?

Organ conservation is important

In 1931, prominent British gynecologic surgeon Victor Bonney said, “Since cure without deformity or loss of function must ever be surgery’s highest ideal, the general proposition that myomectomy is a greater surgical achievement is incontestable.”4 As current hysterectomy and myomectomy rates indicate, however, we are not attempting organ conservation very often.

Other specialties almost never remove an entire organ for benign growths. Using breast cancer surgery as an admirable paradigm, consider that in the early 20th century the standard treatment for breast cancer was a Halsted radical mastectomy with axial lymphadenectomy. By the 1930s, this disfiguring operation was replaced by simple mastectomy and radiation, and by the 1970s, by lumpectomy and lymphadenectomy. Currently, lumpectomy and sentinel node sampling is the standard of care for early stage breast cancer. This is an excellent example of “minimally invasive surgery,” a term fostered by gynecologists. And, these organ-preservingsurgeries are performed for women with cancer, not a benign condition like fibroids.

Although our approach to hysterectomy has evolved with the increasing use of laparoscopic or robotic assistance, removal of the entire uterus nevertheless remains the surgical goal. I think this narrow view of surgical options is a disservice to our patients.

Many of us were taught that myomectomy was associated with more complications and more blood loss than hysterectomy. We were taught that the uterus had no function other than childbearing and that removing the uterus had no adverse health effects. The dogma suggested that myomectomy preserved a uterus that looked like Swiss cheese and would not heal properly and that the risk of fibroid recurrence was high. These beliefs, however, are myths, which are discussed and debunked below. In second and third installments for this series on myomectomy, I present steps for successful abdominal and laparoscopic technique.

Read myths on hysterectomy, myomectomy, and fibroids

MYTH #1: Hysterectomy is safer than myomectomy

Myomectomy is performed within the confines of the uterus and myometrium, with only infrequent occasion to operate near the ureters, uterine vessels, bowel, or bladder. Therefore, it should not be surprising that studies show that fewer complications occur with myomectomy than with hysterectomy.

A retrospective review of 197 women who had myomectomy and 197 women who underwent hysterectomy with similar uterine size (14 vs 15 weeks) reported that 13% (n = 26) of women in the hysterectomy group experienced complications, including 1 bladder injury, 1 ureteral injury, and 3 bowel injuries; 8 women had an ileus and 6 women had a pelvic abscess.5 Only 5% (n = 11) of the myomectomy patients had complications, including 1 bladder injury; 2 women had reoperation for small bowel obstruction, and 6 women had an ileus. The risks of febrile morbidity, unintended surgical procedure, life-threatening events, and rehospitalization were similar for both groups.

Authors of a recent systematic review of 6 studies, which included 1,520 women with uterine size up to 18 weeks, found higher rates of visceral injury and longer hospital stays for women who had a hysterectomy compared with those who had a myomectomy (TABLE 1).6

MYTH #2: Myomectomy is associated with more surgical blood loss than hysterectomy

In the previously cited study of 197 women treated with myomectomy and 197 women treated with hysterectomy, the estimated blood loss was greater in the hysterectomy group (484 mL) than in the myomectomy group (227 mL). When uterine size was corrected for, blood loss was no greater for myomectomy than for hysterectomy.5 The risk of hemorrhage (>500 mL blood loss) was greater in the hysterectomy group (14.2% vs 9.6%). Authors of the recent meta-analysis also found that the rate of transfusion was higher in the hysterectomy cohort. Tourniquets, misoprostol, vasopressin, and tranexamic acid all have been shown to significantly decrease surgical blood loss. (These treatments will be discussed in the next installment of this article series.)

MYTH #3: A uterus will look like Swiss cheese after a myomectomy

The uterus heals remarkably well after myomectomy. Three months following laparoscopic myomectomy, 3-dimensional Doppler ultrasonography demonstrated complete myometrial healing and normal blood flow to the uterus.7 In a study of women undergoing abdominal myomectomy, follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium showed complete healing of the myometrium and normal myometrial perfusion by 3 months.8 This study also found that, after removal of 65 g to 380 g of fibroids, the uterine volume 3 months after surgery was 65 mL, essentially equivalent to the normal volume of a uterus without fibroids (57 mL).8 See FIGURE for MRI scans of the uterus before and after myomectomy.

MYTH #4: Fibroids will just grow back after myomectomy

Once a fibroid is completely removed surgically, it does not grow back. The risk of new fibroid growth depends on the number of fibroids originally removed and the amount of time until menopause, when fibroids reduce in size and symptoms usually resolve. Given that the prevalence of fibroids is nearly 80% by age 50, studies measuring the detection of new fibroid growth of 1 cm on ultrasound imaging overstate the problem.9 What is likely a more important consideration for women is whether, following myomectomy, they will need another procedure for new fibroid-related symptoms.

Results of a meta-analysis of 872 women in 7 studies with 10- to 25-year follow-up indicated that 89% of women did not require another surgery.10 In another study, authors found that, over an average follow-up of 7.6 years, a second surgery occurred in 11% of the women who had 1 fibroid initially removed and for 26% of women who had multiple fibroids initially removed.11 In another study of 92 women who had either abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy after age 45and who were followed for an average of 30 months, only 1 woman (1%) required a hysterectomy for fibroid-related symptoms.12 That patient had growth of a fibroid that was present but was not removed at her initial laparoscopic myomectomy.

Read myths 5–7 on ovarian conservation, fibroid growth, and symptom improvement

MYTH #5: Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation does not change hormone levels

Following hysterectomy with ovarian conservation, some women begin menopause earlier than age-matched women who have not undergone any surgery.13 Hysterectomy with ovarian conservation prior to age 50 has been associated with a significant increase in the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.14 In a prospective longitudinal study, antimüllerian hormone (AMH) levels were persistently decreased following hysterectomy despite ovarian conservation.15 However, 3 months after myomectomy, no such changes in AMH levels were seen (TABLE 2).15

Early natural menopause has been associated with an increase in cardiovascular disease and death, and bilateral oophorectomy has been associated with increased risks of cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, lung cancer, colon cancer, anxiety, and depression. Although taking estrogen might obviate these adverse health effects, the majority of women who receive a prescription for estrogen following surgery are no longer taking it 5 years later.

MYTH #6: Fibroid growth in a premenopausal patient means cancer may be present

While most fibroids grow slowly, rapid growth of benign fibroids is very common. Using computerized analysis of a group of 72 women having serial MRI scans, investigators found that 34% of benign fibroids increased more than 20% in volume over 6 months.16 In premenopausal women, “rapid uterine growth” almost never indicates presence of uterine sarcoma. One study reported only 1 sarcoma among 371 women operated on for rapid growth of presumed fibroids.17 Using current criteria from the World Health Organization to determine the pathologic diagnosis, however, that 1 woman was determined to have had an atypical leiomyoma. Therefore, the prevalence of leiomyosarcoma in that study approached zero. In addition, in the 198 women who had a 6-week increase in uterine size over 1 year (one published definition of rapid growth), no sarcomas were found.17

Because of recent concern about leiomyosarcoma and morcellation of fibroids, some gynecologists have reverted to advising women that growing fibroids might be cancer and that hysterectomy is recommended. However, there is no evidence that fibroid growth is a sign of leiomyosarcoma in premenopausal women. Leiomyosarcoma should strongly be considered in a postmenopausal woman on no hormone therapy who has growth of a presumed fibroid.

MYTH #7: Myomectomy will not improve symptoms

Fibroid-related symptoms can be significant; women who undergo hysterectomy because of fibroid-related symptoms have significantly worse scores on the 36-Item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) quality-of-life questionnaire than women diagnosed with hypertension, heart disease, chronic lung disease, or arthritis.18

For women with fibroid-related symptoms, myomectomy has been shown to improve quality of life. A study of 72 women showed that SF-36 scores improved significantly following myomectomy (TABLE 3, page 48).19 In another study that used the European Quality of Life Five-Dimension Scale and Visual Analog Scale, 95 women had significant improvement in quality of life (P<.001) following laparoscopic myomectomy.20

For some women, hysterectomy may have an impact on emotional quality of life. Some women report decreased sexual desire after hysterectomy. They worry that partners will see them as “not whole” and less desirable. Some women expect that hysterectomy will lead to depression, crying, lack of sexual desire, and vaginal dryness.21 No such changes have been reported for women having myomectomy.

CASE Continued: Third consult leads patient to schedule surgical procedure

After reviewing the patient’s symptoms, examination, and ultrasound results, we advise the patient that abdominal myomectomy is indeed appropriate and feasible in her case. She schedules surgery for the following month.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211.e1–e9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387–400.

- Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Stewart EA. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):319.e1–e20.

- Bonney V. The technique and results of myomectomy. Lancet. 1931;217(5604):171-177.

- Sawin SW, Pilevsky ND, Berlin JA, Barnhart KT. Comparability of perioperative morbidity between abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy for women with uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1448–1455.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- Chang WC, Chang DY, Huang SC, et al. Use of three-dimensional ultrasonography in the evaluation of uterine perfusion and healing after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1110–1115.

- Tsuji S, Takahashi K, Imaoka I, Sugimura K, Miyazaki K, Noda Y. MRI evaluation of the uterine structure after myomectomy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(2):106–110.

- Sudik R, Husch K, Steller J, Daume E. Fertility and pregnancy outcome after myomectomy in sterility patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65(2):209–214.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Babaki-Fard K, Dubuisson JB. Recurrence of leiomyomata after myomectomy. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(6):595–602.

- Malone, LJ. Myomectomy: recurrence after removal of solitary and multiple myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;34(2):200–203.

- Kim DH, Kim ML, Song T, Kim MK, Yoon BS, Seong SJ. Is myomectomy in women aged 45 years and older an effective option? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:57–60.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, Stewart AW. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112(7):956–962.

- Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(6):745–750.

- Wang HY, Quan S, Zhang RL, et al. Comparison of serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels following hysterectomy and myomectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(2):368–371.

- Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(50):19887–19892.

- Parker W, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(3):414–418.

- Rowe MK, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, Bernstein SJ. Quality of life among women undergoing hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(6):915–921.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Radosa JC, Radosa CG, Mavrova R, et al. Postoperative quality of life and sexual function in premenopausal women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic fibroids: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;29;11(11):e0166659.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, Shelton AJ, Lees E, Goode J. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(suppl 2):39S–50S.

- Cardozo ER, Clark AD, Banks NK, Henne MB, Stegmann BJ, Segars JH. The estimated annual cost of leiomyomata in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):211.e1–e9.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 96: alternatives to hysterectomy in the management of leiomyomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):387–400.

- Borah BJ, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Stewart EA. The impact of uterine leiomyomas: a national survey of affected women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(4):319.e1–e20.

- Bonney V. The technique and results of myomectomy. Lancet. 1931;217(5604):171-177.

- Sawin SW, Pilevsky ND, Berlin JA, Barnhart KT. Comparability of perioperative morbidity between abdominal myomectomy and hysterectomy for women with uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1448–1455.

- Pundir J, Walawalkar R, Seshadri S, Khalaf Y, El-Toukhy T. Perioperative morbidity associated with abdominal myomectomy compared with total abdominal hysterectomy for uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;33(7):655–662.

- Chang WC, Chang DY, Huang SC, et al. Use of three-dimensional ultrasonography in the evaluation of uterine perfusion and healing after laparoscopic myomectomy. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(3):1110–1115.

- Tsuji S, Takahashi K, Imaoka I, Sugimura K, Miyazaki K, Noda Y. MRI evaluation of the uterine structure after myomectomy. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(2):106–110.

- Sudik R, Husch K, Steller J, Daume E. Fertility and pregnancy outcome after myomectomy in sterility patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;65(2):209–214.

- Fauconnier A, Chapron C, Babaki-Fard K, Dubuisson JB. Recurrence of leiomyomata after myomectomy. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6(6):595–602.

- Malone, LJ. Myomectomy: recurrence after removal of solitary and multiple myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;34(2):200–203.

- Kim DH, Kim ML, Song T, Kim MK, Yoon BS, Seong SJ. Is myomectomy in women aged 45 years and older an effective option? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;177:57–60.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, Stewart AW. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112(7):956–962.

- Ingelsson E, Lundholm C, Johansson AL, Altman D. Hysterectomy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(6):745–750.

- Wang HY, Quan S, Zhang RL, et al. Comparison of serum anti-Mullerian hormone levels following hysterectomy and myomectomy for benign gynaecological conditions. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;171(2):368–371.

- Peddada SD, Laughlin SK, Miner K, et al. Growth of uterine leiomyomata among premenopausal black and white women. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(50):19887–19892.

- Parker W, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83(3):414–418.

- Rowe MK, Kanouse DE, Mittman BS, Bernstein SJ. Quality of life among women undergoing hysterectomies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(6):915–921.

- Dilek S, Ertunc D, Tok EC, Cimen R, Doruk A. The effect of myomectomy on health-related quality of life of women with myoma uteri. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(2):364–369.

- Radosa JC, Radosa CG, Mavrova R, et al. Postoperative quality of life and sexual function in premenopausal women undergoing laparoscopic myomectomy for symptomatic fibroids: a prospective observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;29;11(11):e0166659.

- Groff JY, Mullen PD, Byrd T, Shelton AJ, Lees E, Goode J. Decision making, beliefs, and attitudes toward hysterectomy: a focus group study with medically underserved women in Texas. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(suppl 2):39S–50S.

Should coffee consumption be added as an adjunct to the postoperative care of gynecologic oncology patients?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postoperative ileus is a common complication following abdominal surgery, particularly for patients undergoing laparotomy. Ileus is frustrating for patients and providers alike, and its occurrence may prolong the length of hospital stay, increase the cost of care, worsen patient satisfaction, and potentially delay postoperative treatments, such as chemotherapy for patients with gynecologic malignancies. The etiology of ileus is multifactorial, but it is thought to be caused primarily by a local inflammatory response from mechanical handling and irritation of the bowel. Although various interventions, such as laxatives, peripheral mu antagonists, and chewing gum, have been shown to reduce the occurrence of ileus, the effectiveness of these interventions varies, and ileus remains a major source of morbidity.1

Details of the study

To investigate whether coffee consumption accelerates recovery of bowel function following surgery, Güngördük and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial of coffee consumption after laparotomy with hysterectomy and staging for patients with gynecologic malignancies. This intervention avoids costs associated with drugs such as oral mu antagonists.

The trial included 114 women; after surgery, 58 were assigned to consume coffee 3 times daily and 56 received routine postoperative care without coffee consumption. The primary outcome measure was the time to the first passage of flatus after surgery. Time to first bowel movement and time to tolerance of a solid diet were secondary outcomes.

The results of this trial are consistent with prior study findings in colorectal surgery.2 Güngördük and associates found that patients in the coffee-consumption group, compared with controls, had reduced the time to flatus by 12 hours (mean [SD] time to flatus, 30.2 [8.0] vs 40.2 [12.1] hours; P<.001), shortened time to full diet by 1.3 days (mean [SD] time to tolerate food, 3.4 [1.2] vs 4.7 [1.6] days; P<.001), reduced time to first bowel movement by 12 hours (43.1 [9.4] vs 58.5 [17.0] hours; P<.001), and shortened length of hospital stay by 1 day. Symptoms of ileus were reduced from 52% to 14% with coffee consumption.

Study limitation. An important weakness of this study is that although the authors defined the severity of ileus by time to resolution, they did not define what constituted a diagnosis of ileus in the first place.

Unanswered questions. Coffee is a known diarrhetic, so it is not unexpected that its use shortened time to flatus and first bowel movement. What is not known, however, is whether coffee consumption improves recovery. The significance of a 1-day reduction in hospital stay is unclear given the relatively prolonged hospitalization (6 to 7 days) seen in this investigation of patients with mixed gynecologic malignancies who underwent staging only. In contrast, another study showed that, for patients managed within an enhanced recovery pathway (a multimodal perioperative care enhancement protocol), median length of stay was 4 days for patients who underwent staging alone and 5 days for patients with ovarian cancer (40% underwent enteric resections).3 Thus, the effects of coffee consumption are unclear for patients managed with an optimized perioperative pathway.

The improvement in oral intake is also of questionable significance since these patients tolerated a solid diet 3 to 4 days after surgery, compared with the evening of surgery for most patients managed with enhanced recovery.

Incisional injection of liposomal bupivacaine has been associated with a reduction in the rate of ileus from 22% to 11% after complex cytoreduction for ovarian cancer when added to an existing enhanced recovery pathway; rates were only 5% for patients undergoing staging alone.4 These findings may be due to the significant reduction in opioid use that accompanied the use of liposomal bupivacaine.

--SEAN C. DOWDY, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for post- operative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations--part II. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):323-332.

- Müller SA, Rahbari NN, Schneider F, et al. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of coffee on postoperative ileus following elective colectomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99(11):1530-1538.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122 (2 pt 1):319-328.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Weaver AL, et al. Abdominal incision injection of liposomal bupivacaine and opioid use after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):1009-1017.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postoperative ileus is a common complication following abdominal surgery, particularly for patients undergoing laparotomy. Ileus is frustrating for patients and providers alike, and its occurrence may prolong the length of hospital stay, increase the cost of care, worsen patient satisfaction, and potentially delay postoperative treatments, such as chemotherapy for patients with gynecologic malignancies. The etiology of ileus is multifactorial, but it is thought to be caused primarily by a local inflammatory response from mechanical handling and irritation of the bowel. Although various interventions, such as laxatives, peripheral mu antagonists, and chewing gum, have been shown to reduce the occurrence of ileus, the effectiveness of these interventions varies, and ileus remains a major source of morbidity.1

Details of the study

To investigate whether coffee consumption accelerates recovery of bowel function following surgery, Güngördük and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial of coffee consumption after laparotomy with hysterectomy and staging for patients with gynecologic malignancies. This intervention avoids costs associated with drugs such as oral mu antagonists.

The trial included 114 women; after surgery, 58 were assigned to consume coffee 3 times daily and 56 received routine postoperative care without coffee consumption. The primary outcome measure was the time to the first passage of flatus after surgery. Time to first bowel movement and time to tolerance of a solid diet were secondary outcomes.

The results of this trial are consistent with prior study findings in colorectal surgery.2 Güngördük and associates found that patients in the coffee-consumption group, compared with controls, had reduced the time to flatus by 12 hours (mean [SD] time to flatus, 30.2 [8.0] vs 40.2 [12.1] hours; P<.001), shortened time to full diet by 1.3 days (mean [SD] time to tolerate food, 3.4 [1.2] vs 4.7 [1.6] days; P<.001), reduced time to first bowel movement by 12 hours (43.1 [9.4] vs 58.5 [17.0] hours; P<.001), and shortened length of hospital stay by 1 day. Symptoms of ileus were reduced from 52% to 14% with coffee consumption.

Study limitation. An important weakness of this study is that although the authors defined the severity of ileus by time to resolution, they did not define what constituted a diagnosis of ileus in the first place.

Unanswered questions. Coffee is a known diarrhetic, so it is not unexpected that its use shortened time to flatus and first bowel movement. What is not known, however, is whether coffee consumption improves recovery. The significance of a 1-day reduction in hospital stay is unclear given the relatively prolonged hospitalization (6 to 7 days) seen in this investigation of patients with mixed gynecologic malignancies who underwent staging only. In contrast, another study showed that, for patients managed within an enhanced recovery pathway (a multimodal perioperative care enhancement protocol), median length of stay was 4 days for patients who underwent staging alone and 5 days for patients with ovarian cancer (40% underwent enteric resections).3 Thus, the effects of coffee consumption are unclear for patients managed with an optimized perioperative pathway.

The improvement in oral intake is also of questionable significance since these patients tolerated a solid diet 3 to 4 days after surgery, compared with the evening of surgery for most patients managed with enhanced recovery.

Incisional injection of liposomal bupivacaine has been associated with a reduction in the rate of ileus from 22% to 11% after complex cytoreduction for ovarian cancer when added to an existing enhanced recovery pathway; rates were only 5% for patients undergoing staging alone.4 These findings may be due to the significant reduction in opioid use that accompanied the use of liposomal bupivacaine.

--SEAN C. DOWDY, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Postoperative ileus is a common complication following abdominal surgery, particularly for patients undergoing laparotomy. Ileus is frustrating for patients and providers alike, and its occurrence may prolong the length of hospital stay, increase the cost of care, worsen patient satisfaction, and potentially delay postoperative treatments, such as chemotherapy for patients with gynecologic malignancies. The etiology of ileus is multifactorial, but it is thought to be caused primarily by a local inflammatory response from mechanical handling and irritation of the bowel. Although various interventions, such as laxatives, peripheral mu antagonists, and chewing gum, have been shown to reduce the occurrence of ileus, the effectiveness of these interventions varies, and ileus remains a major source of morbidity.1

Details of the study

To investigate whether coffee consumption accelerates recovery of bowel function following surgery, Güngördük and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial of coffee consumption after laparotomy with hysterectomy and staging for patients with gynecologic malignancies. This intervention avoids costs associated with drugs such as oral mu antagonists.

The trial included 114 women; after surgery, 58 were assigned to consume coffee 3 times daily and 56 received routine postoperative care without coffee consumption. The primary outcome measure was the time to the first passage of flatus after surgery. Time to first bowel movement and time to tolerance of a solid diet were secondary outcomes.

The results of this trial are consistent with prior study findings in colorectal surgery.2 Güngördük and associates found that patients in the coffee-consumption group, compared with controls, had reduced the time to flatus by 12 hours (mean [SD] time to flatus, 30.2 [8.0] vs 40.2 [12.1] hours; P<.001), shortened time to full diet by 1.3 days (mean [SD] time to tolerate food, 3.4 [1.2] vs 4.7 [1.6] days; P<.001), reduced time to first bowel movement by 12 hours (43.1 [9.4] vs 58.5 [17.0] hours; P<.001), and shortened length of hospital stay by 1 day. Symptoms of ileus were reduced from 52% to 14% with coffee consumption.

Study limitation. An important weakness of this study is that although the authors defined the severity of ileus by time to resolution, they did not define what constituted a diagnosis of ileus in the first place.

Unanswered questions. Coffee is a known diarrhetic, so it is not unexpected that its use shortened time to flatus and first bowel movement. What is not known, however, is whether coffee consumption improves recovery. The significance of a 1-day reduction in hospital stay is unclear given the relatively prolonged hospitalization (6 to 7 days) seen in this investigation of patients with mixed gynecologic malignancies who underwent staging only. In contrast, another study showed that, for patients managed within an enhanced recovery pathway (a multimodal perioperative care enhancement protocol), median length of stay was 4 days for patients who underwent staging alone and 5 days for patients with ovarian cancer (40% underwent enteric resections).3 Thus, the effects of coffee consumption are unclear for patients managed with an optimized perioperative pathway.

The improvement in oral intake is also of questionable significance since these patients tolerated a solid diet 3 to 4 days after surgery, compared with the evening of surgery for most patients managed with enhanced recovery.

Incisional injection of liposomal bupivacaine has been associated with a reduction in the rate of ileus from 22% to 11% after complex cytoreduction for ovarian cancer when added to an existing enhanced recovery pathway; rates were only 5% for patients undergoing staging alone.4 These findings may be due to the significant reduction in opioid use that accompanied the use of liposomal bupivacaine.

--SEAN C. DOWDY, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for post- operative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations--part II. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):323-332.

- Müller SA, Rahbari NN, Schneider F, et al. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of coffee on postoperative ileus following elective colectomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99(11):1530-1538.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122 (2 pt 1):319-328.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Weaver AL, et al. Abdominal incision injection of liposomal bupivacaine and opioid use after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):1009-1017.

- Nelson G, Altman AD, Nick A, et al. Guidelines for post- operative care in gynecologic/oncology surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations--part II. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;140(2):323-332.

- Müller SA, Rahbari NN, Schneider F, et al. Randomized clinical trial on the effect of coffee on postoperative ileus following elective colectomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99(11):1530-1538.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Jankowski CJ, et al. Enhanced recovery in gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122 (2 pt 1):319-328.

- Kalogera E, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Weaver AL, et al. Abdominal incision injection of liposomal bupivacaine and opioid use after laparotomy for gynecologic malignancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(5):1009-1017.

Musculoskeletal Hand Pain Group Visits: An Adaptive Health Care Model

From Cooper Medical School of Rowan University (Dr. Patel, Dr. Fuller) and Cooper University Hospital (Dr. Kaufman), Camden, NJ.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe an adaptive musculoskeletal hand clinic that offers accessible and economically viable musculoskeletal care for an underserved, urban population.

- Methods: Descriptive report.