User login

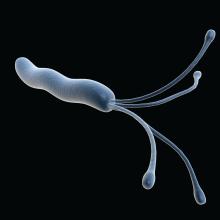

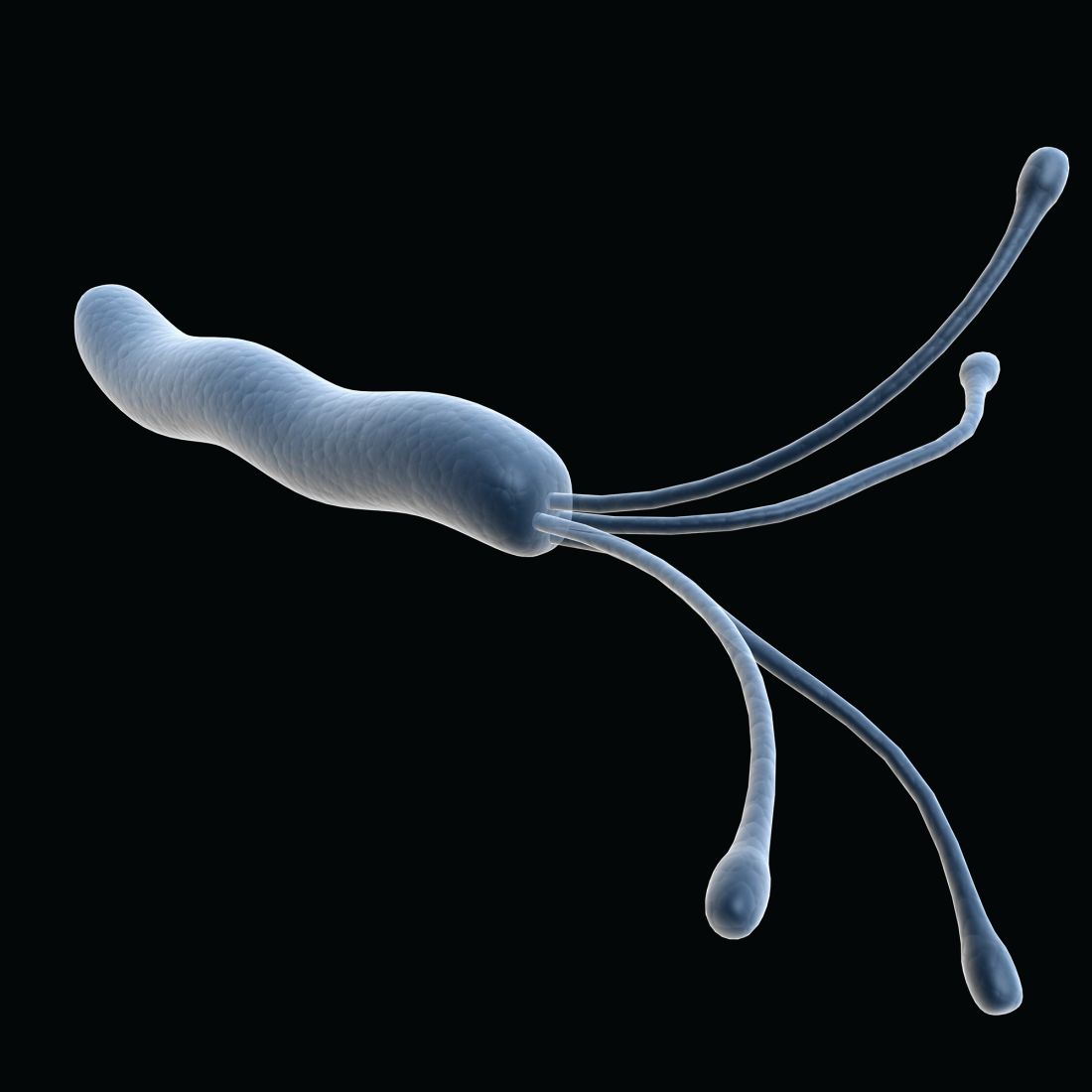

Stool samples meet gastric biopsies for H. pylori antibiotic resistance testing

Using stool samples to test for Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance provides highly similar results to those of gastric biopsy samples, which suggests that stool testing may be a safer, more convenient, and more cost-effective option, according to investigators.

Head-to-head testing for resistance-associated mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS) showed 92% concordance between the two sample types, with 100% technical success among polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–positive stool samples, lead author Steven Moss, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues reported.

“H. pylori eradication rates have declined largely due to rising antimicrobial resistance worldwide,” Dr. Moss said at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “There is therefore a need for rapid, accurate, reliable antibiotic resistance testing.”

According to Dr. Moss, molecular resistance testing of gastric biopsies yields similar results to culture-based testing of gastric biopsies, but endoscopic sample collection remains inconvenient and relatively costly, so “it is not commonly performed in many GI practices.

“Whether reliable resistance testing by NGS is possible from stool samples remains unclear,” Dr. Moss said.

To explore this possibility, Dr. Moss and colleagues recruited 262 patients scheduled for upper endoscopy at four sites in the United States. From each patient, two gastric biopsies were taken, and within 2 weeks of the procedure, prior to starting anti–H. pylori therapy, one stool sample was collected.

For gastric biopsy samples, H. pylori positivity was confirmed by PCR, whereas positivity in stool samples was confirmed by both fecal antigen testing and PCR. After confirmation, NGS was conducted, with screening for resistance-associated mutations to six commonly used antibiotics: clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin.

Out of 262 patients, 73 tested positive for H. pylori via stool testing; however, 2 of these patients had inadequate gastric DNA for analysis, leaving 71 patients in the evaluable dataset. Within this group, samples from 50 patients (70.4%) had at least one resistance-association mutation.

Among all 71 individuals, 65 patients (91.5%) had fully concordant results between the two sample types. In four out of the six discordant cases, there was only one difference in antibiotic-associated mutations. Concordance ranged from 89% for metronidazole mutations to 100% for tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin mutations.

“It is now possible to rapidly obtain susceptibility data without endoscopy,” Dr. Moss concluded. “Using NGS to determine H. pylori antibiotic resistance using stool obviates the cost, inconvenience, and risks of endoscopy resistance profiling.”

Dr. Moss noted that the cost of the stool-based test, through study sponsor American Molecular Laboratories, is about $450, and that the company is “working with various insurance companies to try to get [the test] reimbursed.”

For cases of H. pylori infection without resistance testing results, Dr. Moss recommended first-line treatment with quadruple bismuth–based therapy; however, he noted that “most gastroenterologists, in all kinds of practice, are not measuring their eradication success rate ... so it’s really difficult to know if your best guess is really the appropriate treatment.”

According to Lukasz Kwapisz, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, the concordance results are “encouraging,” and suggest that stool-based testing “could be much easier for the patient and the clinician” to find ways to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Dr. Kwapisz predicted that it will take additional successful studies, as well as real-world data, to convert clinicians to the new approach. He suggested that the transition may be gradual, like the adoption of fecal calprotectin testing.

“I don’t know if it’s one singular defining study that will tell you: ‘Okay, we all have to use this [stool-based resistance testing],’ ” he said. “It kind of happens over time – over a 2- or 3-year stretch, I would think, with positive results.”

The study was supported by American Molecular Labs. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Phathom, and Redhill. Dr. Kwapisz reported no conflicts of interest.

Using stool samples to test for Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance provides highly similar results to those of gastric biopsy samples, which suggests that stool testing may be a safer, more convenient, and more cost-effective option, according to investigators.

Head-to-head testing for resistance-associated mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS) showed 92% concordance between the two sample types, with 100% technical success among polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–positive stool samples, lead author Steven Moss, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues reported.

“H. pylori eradication rates have declined largely due to rising antimicrobial resistance worldwide,” Dr. Moss said at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “There is therefore a need for rapid, accurate, reliable antibiotic resistance testing.”

According to Dr. Moss, molecular resistance testing of gastric biopsies yields similar results to culture-based testing of gastric biopsies, but endoscopic sample collection remains inconvenient and relatively costly, so “it is not commonly performed in many GI practices.

“Whether reliable resistance testing by NGS is possible from stool samples remains unclear,” Dr. Moss said.

To explore this possibility, Dr. Moss and colleagues recruited 262 patients scheduled for upper endoscopy at four sites in the United States. From each patient, two gastric biopsies were taken, and within 2 weeks of the procedure, prior to starting anti–H. pylori therapy, one stool sample was collected.

For gastric biopsy samples, H. pylori positivity was confirmed by PCR, whereas positivity in stool samples was confirmed by both fecal antigen testing and PCR. After confirmation, NGS was conducted, with screening for resistance-associated mutations to six commonly used antibiotics: clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin.

Out of 262 patients, 73 tested positive for H. pylori via stool testing; however, 2 of these patients had inadequate gastric DNA for analysis, leaving 71 patients in the evaluable dataset. Within this group, samples from 50 patients (70.4%) had at least one resistance-association mutation.

Among all 71 individuals, 65 patients (91.5%) had fully concordant results between the two sample types. In four out of the six discordant cases, there was only one difference in antibiotic-associated mutations. Concordance ranged from 89% for metronidazole mutations to 100% for tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin mutations.

“It is now possible to rapidly obtain susceptibility data without endoscopy,” Dr. Moss concluded. “Using NGS to determine H. pylori antibiotic resistance using stool obviates the cost, inconvenience, and risks of endoscopy resistance profiling.”

Dr. Moss noted that the cost of the stool-based test, through study sponsor American Molecular Laboratories, is about $450, and that the company is “working with various insurance companies to try to get [the test] reimbursed.”

For cases of H. pylori infection without resistance testing results, Dr. Moss recommended first-line treatment with quadruple bismuth–based therapy; however, he noted that “most gastroenterologists, in all kinds of practice, are not measuring their eradication success rate ... so it’s really difficult to know if your best guess is really the appropriate treatment.”

According to Lukasz Kwapisz, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, the concordance results are “encouraging,” and suggest that stool-based testing “could be much easier for the patient and the clinician” to find ways to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Dr. Kwapisz predicted that it will take additional successful studies, as well as real-world data, to convert clinicians to the new approach. He suggested that the transition may be gradual, like the adoption of fecal calprotectin testing.

“I don’t know if it’s one singular defining study that will tell you: ‘Okay, we all have to use this [stool-based resistance testing],’ ” he said. “It kind of happens over time – over a 2- or 3-year stretch, I would think, with positive results.”

The study was supported by American Molecular Labs. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Phathom, and Redhill. Dr. Kwapisz reported no conflicts of interest.

Using stool samples to test for Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance provides highly similar results to those of gastric biopsy samples, which suggests that stool testing may be a safer, more convenient, and more cost-effective option, according to investigators.

Head-to-head testing for resistance-associated mutations using next-generation sequencing (NGS) showed 92% concordance between the two sample types, with 100% technical success among polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–positive stool samples, lead author Steven Moss, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues reported.

“H. pylori eradication rates have declined largely due to rising antimicrobial resistance worldwide,” Dr. Moss said at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology. “There is therefore a need for rapid, accurate, reliable antibiotic resistance testing.”

According to Dr. Moss, molecular resistance testing of gastric biopsies yields similar results to culture-based testing of gastric biopsies, but endoscopic sample collection remains inconvenient and relatively costly, so “it is not commonly performed in many GI practices.

“Whether reliable resistance testing by NGS is possible from stool samples remains unclear,” Dr. Moss said.

To explore this possibility, Dr. Moss and colleagues recruited 262 patients scheduled for upper endoscopy at four sites in the United States. From each patient, two gastric biopsies were taken, and within 2 weeks of the procedure, prior to starting anti–H. pylori therapy, one stool sample was collected.

For gastric biopsy samples, H. pylori positivity was confirmed by PCR, whereas positivity in stool samples was confirmed by both fecal antigen testing and PCR. After confirmation, NGS was conducted, with screening for resistance-associated mutations to six commonly used antibiotics: clarithromycin, levofloxacin, metronidazole, tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin.

Out of 262 patients, 73 tested positive for H. pylori via stool testing; however, 2 of these patients had inadequate gastric DNA for analysis, leaving 71 patients in the evaluable dataset. Within this group, samples from 50 patients (70.4%) had at least one resistance-association mutation.

Among all 71 individuals, 65 patients (91.5%) had fully concordant results between the two sample types. In four out of the six discordant cases, there was only one difference in antibiotic-associated mutations. Concordance ranged from 89% for metronidazole mutations to 100% for tetracycline, amoxicillin, and rifabutin mutations.

“It is now possible to rapidly obtain susceptibility data without endoscopy,” Dr. Moss concluded. “Using NGS to determine H. pylori antibiotic resistance using stool obviates the cost, inconvenience, and risks of endoscopy resistance profiling.”

Dr. Moss noted that the cost of the stool-based test, through study sponsor American Molecular Laboratories, is about $450, and that the company is “working with various insurance companies to try to get [the test] reimbursed.”

For cases of H. pylori infection without resistance testing results, Dr. Moss recommended first-line treatment with quadruple bismuth–based therapy; however, he noted that “most gastroenterologists, in all kinds of practice, are not measuring their eradication success rate ... so it’s really difficult to know if your best guess is really the appropriate treatment.”

According to Lukasz Kwapisz, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, the concordance results are “encouraging,” and suggest that stool-based testing “could be much easier for the patient and the clinician” to find ways to eradicate H. pylori infection.

Dr. Kwapisz predicted that it will take additional successful studies, as well as real-world data, to convert clinicians to the new approach. He suggested that the transition may be gradual, like the adoption of fecal calprotectin testing.

“I don’t know if it’s one singular defining study that will tell you: ‘Okay, we all have to use this [stool-based resistance testing],’ ” he said. “It kind of happens over time – over a 2- or 3-year stretch, I would think, with positive results.”

The study was supported by American Molecular Labs. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with Takeda, Phathom, and Redhill. Dr. Kwapisz reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM ACG 2021

GERD: Composite pH impedance monitoring better identifies treatment escalation need

Combinations of abnormal pH-impedance metrics better predicted nonresponse to proton pump inhibitor therapy, as well as benefit of treatment escalation, than individual metrics in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) on twice-daily PPI.

The researchers found a higher proportion of nonresponders to PPI in a group of patients that had combinations of abnormal reflux burden, characterized as acid exposure time greater than 4%, more than 80 reflux episodes, and/or mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI) less than 1,500 ohms, with 85% of these patients improving following initiation of invasive GERD management such as antireflux surgery or magnetic sphincter augmentation.

Not only does the combination of metrics offer more value in identifying responders to PPI than individual metrics, but the combination also offer greater value in “subsequently predicting response to escalation of antireflux management,” study authors C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology.

Currently in question is the applicability of thresholds for metrics from pH impedance monitoring for studies performed on PPI. According to Dr. Gyawali and colleagues, thresholds from the Lyon Consensus may be too high and likewise lack optimal sensitivity for detecting refractory acid burden in patients on PPI, while thresholds based on pH-metry alone, as reported in other publications, may also lack specificity.

To determine which metrics from “on PPI” pH impedance studies predict escalation therapy needs, the researchers analyzed deidentified pH impedance studies performed in healthy volunteers (n=66; median age, 37.5 years) and patients with GERD (n = 43; median age, 57.0 years); both groups were on twice-daily PPI. The investigators compared median values for pH impedance metrics between healthy volunteers and patients with proven GERD using validated measures.

Data were included from a total of three groups: tracings from European and North American healthy volunteers who received twice-daily PPI for 5-7 days; tracings from European patients with heartburn-predominant proven GERD with prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI; and tracings from a cohort of patients with regurgitation-predominant, proven GERD and prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI.

A improvement in heartburn of at least 50%, as recorded on 4-point Likert-type scales, defined PPI responders and improvements following antireflux surgery in the European comparison group. Additionally, an improvement of at least 50% on the GERD Health-Related Quality of Life scale also characterized PPI responders and improvements following magnetic sphincter augmentation in the North American comparison group.

There was no significant difference between PPI responders and nonresponders in terms of individual conventional and novel reflux metrics. The combinations of metrics associated with abnormal reflux burden and abnormal mucosal integrity (acid exposure time >4%, >80 reflux episodes, and MNBI <1,500 ohms) were observed in 32.6% of patients with heartburn and 40.5% of patients with regurgitation-predominant GERD, but no healthy volunteers. The combinations were also observed in 57.1% and 82.4% of nonresponders, respectively.

The authors defined a borderline category (acid exposure time, >0.5% but <4%; >40 but <80 reflux episodes), which accounted for 32.6% of patients with heartburn-predominant GERD and 50% of those regurgitation-predominant GERD. Nonresponse among these borderline cases was identified in 28.6% and 81%, respectively.

“Performance characteristics of the presence of abnormal reflux burden and/or abnormal mucosal integrity in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.50; specificity, 0.71; and AUC, 0.59 (P = .15),” the authors explained. “Performance characteristics of abnormal and borderline reflux burden categories together in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.86; specificity, 0.36; and AUC, 0.62 (P = .07).”

Limitations of this study included its retrospective nature, small sample sizes for the healthy volunteer and GERD populations, and the lack of data on relevant clinical information, including body mass index, dietary patterns, and PPI types and doses. Additionally, the findings may lack generalizability because of the inclusion of only patients with GERD who underwent surgical management.

Despite these limitations, the researchers wrote that the findings and identified “thresholds will be useful in planning prospective outcome studies to conclusively determine when to escalate antireflux therapy when GERD symptoms persist despite bid PPI therapy.”

The study researchers reported conflicts of interest with several pharmaceutical companies. No funding was reported for the study.

The management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common referral for a gastroenterologist; however, metrics to determine dose-escalation for persistent symptoms in patients with proven GERD is an unmet need. The Lyon consensus aimed to standardize abnormal pH parameters but used similar thresholds for off– and on–proton pump inhibitor testing; these thresholds for on-PPI testing are likely too high to detect refractory reflux on PPI therapy. The use of pH-impedance testing is an optimal test for patients with persistent symptoms in the setting of proven GERD to determine escalation of antireflux therapy. In this multicenter, international cohort study, Gyawali and colleagues rigorously challenged the definition of abnormal pH-impedance testing with an evaluation of pH impedance parameters comparing controls (n = 66) versus proven GERD (n = 43) on twice-daily PPI dosing to define pH-impedance parameters.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor in the department of medicine in the section of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

The management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common referral for a gastroenterologist; however, metrics to determine dose-escalation for persistent symptoms in patients with proven GERD is an unmet need. The Lyon consensus aimed to standardize abnormal pH parameters but used similar thresholds for off– and on–proton pump inhibitor testing; these thresholds for on-PPI testing are likely too high to detect refractory reflux on PPI therapy. The use of pH-impedance testing is an optimal test for patients with persistent symptoms in the setting of proven GERD to determine escalation of antireflux therapy. In this multicenter, international cohort study, Gyawali and colleagues rigorously challenged the definition of abnormal pH-impedance testing with an evaluation of pH impedance parameters comparing controls (n = 66) versus proven GERD (n = 43) on twice-daily PPI dosing to define pH-impedance parameters.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor in the department of medicine in the section of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

The management of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common referral for a gastroenterologist; however, metrics to determine dose-escalation for persistent symptoms in patients with proven GERD is an unmet need. The Lyon consensus aimed to standardize abnormal pH parameters but used similar thresholds for off– and on–proton pump inhibitor testing; these thresholds for on-PPI testing are likely too high to detect refractory reflux on PPI therapy. The use of pH-impedance testing is an optimal test for patients with persistent symptoms in the setting of proven GERD to determine escalation of antireflux therapy. In this multicenter, international cohort study, Gyawali and colleagues rigorously challenged the definition of abnormal pH-impedance testing with an evaluation of pH impedance parameters comparing controls (n = 66) versus proven GERD (n = 43) on twice-daily PPI dosing to define pH-impedance parameters.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor in the department of medicine in the section of gastroenterology & hepatology at the Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

Combinations of abnormal pH-impedance metrics better predicted nonresponse to proton pump inhibitor therapy, as well as benefit of treatment escalation, than individual metrics in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) on twice-daily PPI.

The researchers found a higher proportion of nonresponders to PPI in a group of patients that had combinations of abnormal reflux burden, characterized as acid exposure time greater than 4%, more than 80 reflux episodes, and/or mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI) less than 1,500 ohms, with 85% of these patients improving following initiation of invasive GERD management such as antireflux surgery or magnetic sphincter augmentation.

Not only does the combination of metrics offer more value in identifying responders to PPI than individual metrics, but the combination also offer greater value in “subsequently predicting response to escalation of antireflux management,” study authors C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology.

Currently in question is the applicability of thresholds for metrics from pH impedance monitoring for studies performed on PPI. According to Dr. Gyawali and colleagues, thresholds from the Lyon Consensus may be too high and likewise lack optimal sensitivity for detecting refractory acid burden in patients on PPI, while thresholds based on pH-metry alone, as reported in other publications, may also lack specificity.

To determine which metrics from “on PPI” pH impedance studies predict escalation therapy needs, the researchers analyzed deidentified pH impedance studies performed in healthy volunteers (n=66; median age, 37.5 years) and patients with GERD (n = 43; median age, 57.0 years); both groups were on twice-daily PPI. The investigators compared median values for pH impedance metrics between healthy volunteers and patients with proven GERD using validated measures.

Data were included from a total of three groups: tracings from European and North American healthy volunteers who received twice-daily PPI for 5-7 days; tracings from European patients with heartburn-predominant proven GERD with prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI; and tracings from a cohort of patients with regurgitation-predominant, proven GERD and prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI.

A improvement in heartburn of at least 50%, as recorded on 4-point Likert-type scales, defined PPI responders and improvements following antireflux surgery in the European comparison group. Additionally, an improvement of at least 50% on the GERD Health-Related Quality of Life scale also characterized PPI responders and improvements following magnetic sphincter augmentation in the North American comparison group.

There was no significant difference between PPI responders and nonresponders in terms of individual conventional and novel reflux metrics. The combinations of metrics associated with abnormal reflux burden and abnormal mucosal integrity (acid exposure time >4%, >80 reflux episodes, and MNBI <1,500 ohms) were observed in 32.6% of patients with heartburn and 40.5% of patients with regurgitation-predominant GERD, but no healthy volunteers. The combinations were also observed in 57.1% and 82.4% of nonresponders, respectively.

The authors defined a borderline category (acid exposure time, >0.5% but <4%; >40 but <80 reflux episodes), which accounted for 32.6% of patients with heartburn-predominant GERD and 50% of those regurgitation-predominant GERD. Nonresponse among these borderline cases was identified in 28.6% and 81%, respectively.

“Performance characteristics of the presence of abnormal reflux burden and/or abnormal mucosal integrity in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.50; specificity, 0.71; and AUC, 0.59 (P = .15),” the authors explained. “Performance characteristics of abnormal and borderline reflux burden categories together in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.86; specificity, 0.36; and AUC, 0.62 (P = .07).”

Limitations of this study included its retrospective nature, small sample sizes for the healthy volunteer and GERD populations, and the lack of data on relevant clinical information, including body mass index, dietary patterns, and PPI types and doses. Additionally, the findings may lack generalizability because of the inclusion of only patients with GERD who underwent surgical management.

Despite these limitations, the researchers wrote that the findings and identified “thresholds will be useful in planning prospective outcome studies to conclusively determine when to escalate antireflux therapy when GERD symptoms persist despite bid PPI therapy.”

The study researchers reported conflicts of interest with several pharmaceutical companies. No funding was reported for the study.

Combinations of abnormal pH-impedance metrics better predicted nonresponse to proton pump inhibitor therapy, as well as benefit of treatment escalation, than individual metrics in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) on twice-daily PPI.

The researchers found a higher proportion of nonresponders to PPI in a group of patients that had combinations of abnormal reflux burden, characterized as acid exposure time greater than 4%, more than 80 reflux episodes, and/or mean nocturnal baseline impedance (MNBI) less than 1,500 ohms, with 85% of these patients improving following initiation of invasive GERD management such as antireflux surgery or magnetic sphincter augmentation.

Not only does the combination of metrics offer more value in identifying responders to PPI than individual metrics, but the combination also offer greater value in “subsequently predicting response to escalation of antireflux management,” study authors C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, of Washington University, St. Louis, and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology.

Currently in question is the applicability of thresholds for metrics from pH impedance monitoring for studies performed on PPI. According to Dr. Gyawali and colleagues, thresholds from the Lyon Consensus may be too high and likewise lack optimal sensitivity for detecting refractory acid burden in patients on PPI, while thresholds based on pH-metry alone, as reported in other publications, may also lack specificity.

To determine which metrics from “on PPI” pH impedance studies predict escalation therapy needs, the researchers analyzed deidentified pH impedance studies performed in healthy volunteers (n=66; median age, 37.5 years) and patients with GERD (n = 43; median age, 57.0 years); both groups were on twice-daily PPI. The investigators compared median values for pH impedance metrics between healthy volunteers and patients with proven GERD using validated measures.

Data were included from a total of three groups: tracings from European and North American healthy volunteers who received twice-daily PPI for 5-7 days; tracings from European patients with heartburn-predominant proven GERD with prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI; and tracings from a cohort of patients with regurgitation-predominant, proven GERD and prior abnormal reflux monitoring off PPI who subsequently received twice-daily PPI.

A improvement in heartburn of at least 50%, as recorded on 4-point Likert-type scales, defined PPI responders and improvements following antireflux surgery in the European comparison group. Additionally, an improvement of at least 50% on the GERD Health-Related Quality of Life scale also characterized PPI responders and improvements following magnetic sphincter augmentation in the North American comparison group.

There was no significant difference between PPI responders and nonresponders in terms of individual conventional and novel reflux metrics. The combinations of metrics associated with abnormal reflux burden and abnormal mucosal integrity (acid exposure time >4%, >80 reflux episodes, and MNBI <1,500 ohms) were observed in 32.6% of patients with heartburn and 40.5% of patients with regurgitation-predominant GERD, but no healthy volunteers. The combinations were also observed in 57.1% and 82.4% of nonresponders, respectively.

The authors defined a borderline category (acid exposure time, >0.5% but <4%; >40 but <80 reflux episodes), which accounted for 32.6% of patients with heartburn-predominant GERD and 50% of those regurgitation-predominant GERD. Nonresponse among these borderline cases was identified in 28.6% and 81%, respectively.

“Performance characteristics of the presence of abnormal reflux burden and/or abnormal mucosal integrity in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.50; specificity, 0.71; and AUC, 0.59 (P = .15),” the authors explained. “Performance characteristics of abnormal and borderline reflux burden categories together in predicting PPI nonresponse consisted of sensitivity, 0.86; specificity, 0.36; and AUC, 0.62 (P = .07).”

Limitations of this study included its retrospective nature, small sample sizes for the healthy volunteer and GERD populations, and the lack of data on relevant clinical information, including body mass index, dietary patterns, and PPI types and doses. Additionally, the findings may lack generalizability because of the inclusion of only patients with GERD who underwent surgical management.

Despite these limitations, the researchers wrote that the findings and identified “thresholds will be useful in planning prospective outcome studies to conclusively determine when to escalate antireflux therapy when GERD symptoms persist despite bid PPI therapy.”

The study researchers reported conflicts of interest with several pharmaceutical companies. No funding was reported for the study.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Rivaroxaban’s single daily dose may lead to higher bleeding risk than other DOACs

The results, which were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, could help guide DOAC selection for high-risk groups with a prior history of peptic ulcer disease or major GI bleeding, said lead study authors Arnar Bragi Ingason, MD and Einar S. Björnsson, MD, PhD, in an email.

DOACs treat conditions such as atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and ischemic stroke and are known to cause GI bleeding. Previous studies have suggested that rivaroxaban poses a higher GI-bleeding risk than other DOACs.

These studies, which used large administrative databases, “had an inherent risk of selection bias due to insurance status, age, and comorbidities due to their origin from insurance/administrative databases. In addition, they lacked phenotypic details on GI bleeding events,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason, who are both of Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland,

Daily dosage may exacerbate risk

Rivaroxaban is administered as a single daily dose, compared with apixaban’s and dabigatran’s twice-daily regimens. “We hypothesized that this may lead to a greater variance in drug plasma concentration, making these patients more susceptible to GI bleeding,” the lead authors said.

Using data from the Icelandic Medicine Registry, a national database of outpatient prescription information, they compared rates of GI bleeding among new users of apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban from 2014 to 2019. Overall, 5,868 patients receiving one of the DOACs took part in the study. Among these participants, 3,217 received rivaroxaban, 2,157 received apixaban, and 494 received dabigatran. The researchers used inverse probability weighting, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, and Cox regression to compare GI bleeding.

Compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban was associated with a 63%-104% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 39%-95% higher risk for major GI bleeding. Rivaroxaban also had a 40%-42% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 49%-50% higher risk for major GI bleeding, compared with apixaban.

The investigators were surprised by the low rate of upper GI bleeding for dabigatran, compared with the other two drugs. “However, these results must be interpreted in the context that the dabigatran group was relatively small,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason via email.

Overall, the study cohort was small, compared with previous registry studies.

Investigators also did not account for account for socioeconomic status or lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption or smoking. “However, because the cost of all DOACs is similar in Iceland, selection bias due to socioeconomic status is unlikely,” the investigators reported in their paper. “We are currently working on comparing the rates of thromboembolisms and overall major bleeding events between the drugs,” the lead authors said.

Clinicians should consider location of bleeding

Though retrospective, the study by Ingason et. al. “is likely as close as is feasible to a randomized trial as is possible,” said Don C. Rockey, MD, a professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, in an interview.

“From the clinician’s perspective, it is important to take away that there may be differences among the DOACs in terms of where in the GI tract the bleeding occurs,” said Dr. Rockey. In the study, the greatest differences appeared to be in the upper GI tract, with rivaroxaban outpacing apixaban and dabigatran. In patients who are at risk for upper GI bleeding, it may be reasonable to consider use of dabigatran or apixaban, he suggested.

“A limitation of the study is that it is likely underpowered overall,” said Dr. Rockey. It also wasn’t clear how many deaths occurred either directly from GI bleeding or as a complication of GI bleeding, he said.The study also didn’t differentiate major bleeding among DOACs specifically in the upper or lower GI tract, Dr. Rockey added.

Other studies yield similar results

Dr. Ingason and Dr. Björnsson said their work complements previous studies, and Neena S. Abraham, MD, MSc , who has conducted a similar investigation to the new study, agreed with that statement.

Data from the last 4 years overwhelmingly show that rivaroxaban is most likely to cause GI bleeding, said Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine and a consultant with Mayo Clinic’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology, in an interview.

A comparative safety study Dr. Abraham coauthored in 2017 of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran in a much larger U.S. cohort of 372,380 patients revealed that rivaroxaban had the worst GI bleeding profile. Apixaban was 66% safer than rivaroxaban and 64% safer than dabigatran to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding.

“I believe our group was the first to conduct this study and show clinically significant differences in GI safety of the available direct oral anticoagulants,” she said. Other investigators have since published similar results, and the topic of the new study needs no further investigation, according to Dr. Abraham.

“It is time for physicians to choose a better choice when prescribing a direct oral anticoagulant to their atrial fibrillation patients, and that choice is not rivaroxaban,” she said.

The Icelandic Centre for Research and the Landspítali University Hospital Research Fund provided funds for this study. Dr. Ingason, Dr. Björnsson, Dr. Rockey, and Dr. Abraham reported no disclosures.

The results, which were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, could help guide DOAC selection for high-risk groups with a prior history of peptic ulcer disease or major GI bleeding, said lead study authors Arnar Bragi Ingason, MD and Einar S. Björnsson, MD, PhD, in an email.

DOACs treat conditions such as atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and ischemic stroke and are known to cause GI bleeding. Previous studies have suggested that rivaroxaban poses a higher GI-bleeding risk than other DOACs.

These studies, which used large administrative databases, “had an inherent risk of selection bias due to insurance status, age, and comorbidities due to their origin from insurance/administrative databases. In addition, they lacked phenotypic details on GI bleeding events,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason, who are both of Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland,

Daily dosage may exacerbate risk

Rivaroxaban is administered as a single daily dose, compared with apixaban’s and dabigatran’s twice-daily regimens. “We hypothesized that this may lead to a greater variance in drug plasma concentration, making these patients more susceptible to GI bleeding,” the lead authors said.

Using data from the Icelandic Medicine Registry, a national database of outpatient prescription information, they compared rates of GI bleeding among new users of apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban from 2014 to 2019. Overall, 5,868 patients receiving one of the DOACs took part in the study. Among these participants, 3,217 received rivaroxaban, 2,157 received apixaban, and 494 received dabigatran. The researchers used inverse probability weighting, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, and Cox regression to compare GI bleeding.

Compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban was associated with a 63%-104% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 39%-95% higher risk for major GI bleeding. Rivaroxaban also had a 40%-42% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 49%-50% higher risk for major GI bleeding, compared with apixaban.

The investigators were surprised by the low rate of upper GI bleeding for dabigatran, compared with the other two drugs. “However, these results must be interpreted in the context that the dabigatran group was relatively small,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason via email.

Overall, the study cohort was small, compared with previous registry studies.

Investigators also did not account for account for socioeconomic status or lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption or smoking. “However, because the cost of all DOACs is similar in Iceland, selection bias due to socioeconomic status is unlikely,” the investigators reported in their paper. “We are currently working on comparing the rates of thromboembolisms and overall major bleeding events between the drugs,” the lead authors said.

Clinicians should consider location of bleeding

Though retrospective, the study by Ingason et. al. “is likely as close as is feasible to a randomized trial as is possible,” said Don C. Rockey, MD, a professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, in an interview.

“From the clinician’s perspective, it is important to take away that there may be differences among the DOACs in terms of where in the GI tract the bleeding occurs,” said Dr. Rockey. In the study, the greatest differences appeared to be in the upper GI tract, with rivaroxaban outpacing apixaban and dabigatran. In patients who are at risk for upper GI bleeding, it may be reasonable to consider use of dabigatran or apixaban, he suggested.

“A limitation of the study is that it is likely underpowered overall,” said Dr. Rockey. It also wasn’t clear how many deaths occurred either directly from GI bleeding or as a complication of GI bleeding, he said.The study also didn’t differentiate major bleeding among DOACs specifically in the upper or lower GI tract, Dr. Rockey added.

Other studies yield similar results

Dr. Ingason and Dr. Björnsson said their work complements previous studies, and Neena S. Abraham, MD, MSc , who has conducted a similar investigation to the new study, agreed with that statement.

Data from the last 4 years overwhelmingly show that rivaroxaban is most likely to cause GI bleeding, said Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine and a consultant with Mayo Clinic’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology, in an interview.

A comparative safety study Dr. Abraham coauthored in 2017 of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran in a much larger U.S. cohort of 372,380 patients revealed that rivaroxaban had the worst GI bleeding profile. Apixaban was 66% safer than rivaroxaban and 64% safer than dabigatran to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding.

“I believe our group was the first to conduct this study and show clinically significant differences in GI safety of the available direct oral anticoagulants,” she said. Other investigators have since published similar results, and the topic of the new study needs no further investigation, according to Dr. Abraham.

“It is time for physicians to choose a better choice when prescribing a direct oral anticoagulant to their atrial fibrillation patients, and that choice is not rivaroxaban,” she said.

The Icelandic Centre for Research and the Landspítali University Hospital Research Fund provided funds for this study. Dr. Ingason, Dr. Björnsson, Dr. Rockey, and Dr. Abraham reported no disclosures.

The results, which were published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, could help guide DOAC selection for high-risk groups with a prior history of peptic ulcer disease or major GI bleeding, said lead study authors Arnar Bragi Ingason, MD and Einar S. Björnsson, MD, PhD, in an email.

DOACs treat conditions such as atrial fibrillation, venous thromboembolism, and ischemic stroke and are known to cause GI bleeding. Previous studies have suggested that rivaroxaban poses a higher GI-bleeding risk than other DOACs.

These studies, which used large administrative databases, “had an inherent risk of selection bias due to insurance status, age, and comorbidities due to their origin from insurance/administrative databases. In addition, they lacked phenotypic details on GI bleeding events,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason, who are both of Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland,

Daily dosage may exacerbate risk

Rivaroxaban is administered as a single daily dose, compared with apixaban’s and dabigatran’s twice-daily regimens. “We hypothesized that this may lead to a greater variance in drug plasma concentration, making these patients more susceptible to GI bleeding,” the lead authors said.

Using data from the Icelandic Medicine Registry, a national database of outpatient prescription information, they compared rates of GI bleeding among new users of apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban from 2014 to 2019. Overall, 5,868 patients receiving one of the DOACs took part in the study. Among these participants, 3,217 received rivaroxaban, 2,157 received apixaban, and 494 received dabigatran. The researchers used inverse probability weighting, Kaplan–Meier survival estimates, and Cox regression to compare GI bleeding.

Compared with dabigatran, rivaroxaban was associated with a 63%-104% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 39%-95% higher risk for major GI bleeding. Rivaroxaban also had a 40%-42% higher overall risk for GI bleeding and 49%-50% higher risk for major GI bleeding, compared with apixaban.

The investigators were surprised by the low rate of upper GI bleeding for dabigatran, compared with the other two drugs. “However, these results must be interpreted in the context that the dabigatran group was relatively small,” said Dr. Björnsson and Dr. Ingason via email.

Overall, the study cohort was small, compared with previous registry studies.

Investigators also did not account for account for socioeconomic status or lifestyle factors, such as alcohol consumption or smoking. “However, because the cost of all DOACs is similar in Iceland, selection bias due to socioeconomic status is unlikely,” the investigators reported in their paper. “We are currently working on comparing the rates of thromboembolisms and overall major bleeding events between the drugs,” the lead authors said.

Clinicians should consider location of bleeding

Though retrospective, the study by Ingason et. al. “is likely as close as is feasible to a randomized trial as is possible,” said Don C. Rockey, MD, a professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, in an interview.

“From the clinician’s perspective, it is important to take away that there may be differences among the DOACs in terms of where in the GI tract the bleeding occurs,” said Dr. Rockey. In the study, the greatest differences appeared to be in the upper GI tract, with rivaroxaban outpacing apixaban and dabigatran. In patients who are at risk for upper GI bleeding, it may be reasonable to consider use of dabigatran or apixaban, he suggested.

“A limitation of the study is that it is likely underpowered overall,” said Dr. Rockey. It also wasn’t clear how many deaths occurred either directly from GI bleeding or as a complication of GI bleeding, he said.The study also didn’t differentiate major bleeding among DOACs specifically in the upper or lower GI tract, Dr. Rockey added.

Other studies yield similar results

Dr. Ingason and Dr. Björnsson said their work complements previous studies, and Neena S. Abraham, MD, MSc , who has conducted a similar investigation to the new study, agreed with that statement.

Data from the last 4 years overwhelmingly show that rivaroxaban is most likely to cause GI bleeding, said Dr. Abraham, professor of medicine and a consultant with Mayo Clinic’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology, in an interview.

A comparative safety study Dr. Abraham coauthored in 2017 of rivaroxaban, apixaban, and dabigatran in a much larger U.S. cohort of 372,380 patients revealed that rivaroxaban had the worst GI bleeding profile. Apixaban was 66% safer than rivaroxaban and 64% safer than dabigatran to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding.

“I believe our group was the first to conduct this study and show clinically significant differences in GI safety of the available direct oral anticoagulants,” she said. Other investigators have since published similar results, and the topic of the new study needs no further investigation, according to Dr. Abraham.

“It is time for physicians to choose a better choice when prescribing a direct oral anticoagulant to their atrial fibrillation patients, and that choice is not rivaroxaban,” she said.

The Icelandic Centre for Research and the Landspítali University Hospital Research Fund provided funds for this study. Dr. Ingason, Dr. Björnsson, Dr. Rockey, and Dr. Abraham reported no disclosures.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Extraesophageal symptoms of GERD

Patients often present with symptoms that are not classic for reflux such as chronic cough, worsening asthma, sore throat, or globus.

In the upper GI section of the postgraduate course program, Rena Yadlapati, MD, and C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, MRCP, educated us about optimal strategies for diagnosis and treatment of this difficult group of patients. Dr. Gyawali reminded us of risk stratification of patients into those with high or low likelihood of reflux as contributing etiology for patients with suspected extraesophageal reflux. Dr. Yadlapti reviewed the utility of the HASBEER score in stratifying patients into these two risk categories. Patients with known reflux at baseline and/or if they have classic symptoms of reflux in addition to extraesophageal symptoms may be at higher likelihood of having abnormal esophageal acid exposure than those without classic heartburn and/or regurgitation. The low-risk group may then benefit from diagnostic testing off PPI therapy (either impedance/pH monitoring or wireless pH testing), whereas those in the high-risk group for reflux may undergo impedance pH testing on PPI therapy to ensure control of reflux while on therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati also updated the audience about lack of robust data to suggest clinical utility for oropharyngeal pH test or salivary pepsin assay testing. It was generally agreed on that the majority of patients who do not respond to aggressive acid suppressive therapy likely do not have reflux related extraesophageal symptoms and alternative etiologies may be at play.

Finally, both investigators outlined the importance of neuromodulation in those whose symptoms may be due to “irritable larynx.” They emphasized the role of tricyclics as well as gabapentin as off label uses for patients who have normal reflux testing and continue to have chronic cough or globus sensation.

Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, MSc, is an associate chief and a clinical director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition and director of the Clinical Research and Center for Esophageal Disorders at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. He reports consulting for Phathom, Ironwood, Diversatek, Isothrive, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

Patients often present with symptoms that are not classic for reflux such as chronic cough, worsening asthma, sore throat, or globus.

In the upper GI section of the postgraduate course program, Rena Yadlapati, MD, and C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, MRCP, educated us about optimal strategies for diagnosis and treatment of this difficult group of patients. Dr. Gyawali reminded us of risk stratification of patients into those with high or low likelihood of reflux as contributing etiology for patients with suspected extraesophageal reflux. Dr. Yadlapti reviewed the utility of the HASBEER score in stratifying patients into these two risk categories. Patients with known reflux at baseline and/or if they have classic symptoms of reflux in addition to extraesophageal symptoms may be at higher likelihood of having abnormal esophageal acid exposure than those without classic heartburn and/or regurgitation. The low-risk group may then benefit from diagnostic testing off PPI therapy (either impedance/pH monitoring or wireless pH testing), whereas those in the high-risk group for reflux may undergo impedance pH testing on PPI therapy to ensure control of reflux while on therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati also updated the audience about lack of robust data to suggest clinical utility for oropharyngeal pH test or salivary pepsin assay testing. It was generally agreed on that the majority of patients who do not respond to aggressive acid suppressive therapy likely do not have reflux related extraesophageal symptoms and alternative etiologies may be at play.

Finally, both investigators outlined the importance of neuromodulation in those whose symptoms may be due to “irritable larynx.” They emphasized the role of tricyclics as well as gabapentin as off label uses for patients who have normal reflux testing and continue to have chronic cough or globus sensation.

Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, MSc, is an associate chief and a clinical director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition and director of the Clinical Research and Center for Esophageal Disorders at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. He reports consulting for Phathom, Ironwood, Diversatek, Isothrive, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

Patients often present with symptoms that are not classic for reflux such as chronic cough, worsening asthma, sore throat, or globus.

In the upper GI section of the postgraduate course program, Rena Yadlapati, MD, and C. Prakash Gyawali, MD, MRCP, educated us about optimal strategies for diagnosis and treatment of this difficult group of patients. Dr. Gyawali reminded us of risk stratification of patients into those with high or low likelihood of reflux as contributing etiology for patients with suspected extraesophageal reflux. Dr. Yadlapti reviewed the utility of the HASBEER score in stratifying patients into these two risk categories. Patients with known reflux at baseline and/or if they have classic symptoms of reflux in addition to extraesophageal symptoms may be at higher likelihood of having abnormal esophageal acid exposure than those without classic heartburn and/or regurgitation. The low-risk group may then benefit from diagnostic testing off PPI therapy (either impedance/pH monitoring or wireless pH testing), whereas those in the high-risk group for reflux may undergo impedance pH testing on PPI therapy to ensure control of reflux while on therapy.

Dr. Yadlapati also updated the audience about lack of robust data to suggest clinical utility for oropharyngeal pH test or salivary pepsin assay testing. It was generally agreed on that the majority of patients who do not respond to aggressive acid suppressive therapy likely do not have reflux related extraesophageal symptoms and alternative etiologies may be at play.

Finally, both investigators outlined the importance of neuromodulation in those whose symptoms may be due to “irritable larynx.” They emphasized the role of tricyclics as well as gabapentin as off label uses for patients who have normal reflux testing and continue to have chronic cough or globus sensation.

Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, MSc, is an associate chief and a clinical director of the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition and director of the Clinical Research and Center for Esophageal Disorders at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. He reports consulting for Phathom, Ironwood, Diversatek, Isothrive, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

Gastric cancer: Family history–based H. pylori strategy would be cost effective

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

Testing for and treating Helicobacter pylori infection among individuals with a family history of gastric cancer could be a cost-effective strategy in the United States, according to a new model published in the journal Gastroenterology.

As many as 10% of gastric cancers aggregate within families, though just why this happens is unclear, according to Sheila D. Rustgi, MD, and colleagues. Shared environmental or genetic factors, or combinations of both, may be responsible. First-degree family history and H. pylori infection each raise gastric cancer risk by roughly 2.5-fold.

In the United States, universal screening for H. pylori infection is not currently recommended, but some studies have suggested a possible benefit in some high-risk populations. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice guidelines suggest that a patient’s family history should be a factor when considering surveillance strategies for intestinal metaplasia.

Furthermore, a study by Il Ju Choi, MD, and colleagues in 2020 showed that H. pylori treatment with bismuth-based quadruple therapy reduced the risk of gastric cancer by 73% among individuals with a first-degree relative who had gastric cancer. The combination included a proton pump inhibitor, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline for 10 days.

“We hypothesize that, given the dramatic reduction in GC demonstrated by Choi et al., that the screening strategy can be a cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Rustgi and colleagues wrote.

In the new study, the researchers used a Markov state-transition mode, employing a hypothetical cohort of 40-year-old U.S. men and women with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer. It simulated a follow-up period of 60 years or until death. The model assumed a 7-day treatment with triple therapy (proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin) followed by a 14-day treatment period with quadruple therapy if needed. Although the model was analyzed from the U.S. perspective, the trial that informed the risk reduction was performed in a South Korean population.

No screening had a cost of $2,694.09 and resulted in 21.95 quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). 13C-Urea Breath Test screening had a cost of $2,105.28 and led to 22.37 QALYs. Stool antigen testing had a cost of $2,126.00 and yielded 22.30 QALYs.

In the no-screening group, an estimated 2.04% of patients would develop gastric cancer, and 1.82% would die of it. With screening, the frequency of gastric cancer dropped to 1.59%-1.65%, with a gastric cancer mortality rate of 1.41%-1.46%. Overall, screening was modeled to lead to a 19.1%-22.0% risk reduction.

The researchers validated their model by an assumption of an H. pylori infection rate of 100% and then compared the results of the model to the outcome of the study by Dr. Choi and colleagues. In the trial, there was a 55% reduction in gastric cancer among treated patients at a median of 9 years of follow-up. Those who had successful eradication of H. pylori had a 73% reduction. The new model estimated reductions from a testing and treatment strategy of 53.3%-64.5%.

The findings aren’t surprising, according to Joseph Jennings, MD, of the department of medicine at Georgetown University, Washington, and director of the Center for GI Bleeding at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, who was not involved with the study. “Even eliminating one person getting gastric cancer, where they will then need major surgery, chemotherapy, all these very expensive interventions [is important],” said Dr. Jennings. “We have very efficient ways to test for these things that don’t involve endoscopy.”

One potential caveat to identifying and treating H. pylori infection is whether elimination of H. pylori may lead to some adverse effects. Some patients can experience increased acid reflux as a result, while others suffer no ill effects. “But when you’re dealing with the alternative, which is stomach cancer, those negatives would have to stack up really, really high to outweigh the positives of preventing a cancer that’s really hard to treat,” said Dr. Jennings.

Dr. Jennings pointed out that the model also projected testing and an intervention conducted in a South Korean population, and extrapolated it to a U.S. population, where the incidence of gastric cancer is lower. “There definitely are some questions about how well it would translate if applied to the general United States population,” said Dr. Jennings.

That question could prompt researchers to conduct a U.S.-based study modeled after the test and treat study in South Korea to see if the regimen produced similar results. The model should add weight to that argument, said Dr. Jennings: “This is raising the point that, at least from an intellectual level, it might be worth now designing the study to see if it works in our population,” said Dr. Jennings.

The authors and Dr. Jennings have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Is Nissen fundoplication the best we can do?

As an esophagologist that does not perform fundoplication, LINX, or TIF, I find it difficult to debate the merits of one procedure over another based on my experience. In fact, I have always stated that it is difficult to assess a procedure or test that one has not used. That being said, maybe the fact that I have not performed these procedures makes me more objective and I can only use my experience with patients and the data to make the case that we need options beyond Nissen fundoplication.

The recent VA Randomized trial in refractory GERD published by Spechler and colleagues once again highlighted the fact that there are some patients that require a mechanical solution to reflux disease.1 In this study, the authors carefully defined a patient population with refractory GERD and showed that Nissen fundoplication was superior to medical management in patients who did not respond to proton pump inhibitors. However, of the 27 patients who underwent fundoplication, one patient had major complications which required a repeat operation and prolonged hospital stay. These findings highlight the main problem with Nissen fundoplication. Dr. Watson elegantly argued in his assertion during our debate that Nissen and fundoplication are not the same. In this position, he was noting the side effects associated with Nissen fundoplication,2 and he focused his argument on the comparison between a partial wrap versus LINX and TIF to level the playing field. On that note, I agree with Dr. Watson that a well-done partial fundoplication is a great option for patients with a mechanical problem.

Nonetheless, Redo operations have an escalating risk of severe debilitating consequences and we should do everything possible to reduce that risk.3 The LINX and the TIF procedure have data to support their effectiveness, and the initial studies a more favorable side effect profile.4,5 The ability to perform these procedures in patients with hiatal hernia and the fact that these approaches do not exclude the possibility of fundoplication in the future make them an attractive alternative.

In the end, more rigorous comparative studies should be performed to truly determine which approach is better. Although we have good surgical and medical options, we all recognize that they are not perfect and we should not settle on the current state of GERD management.

John E. Pandolfino, MD, MSCI, is the Hans Popper Professor of Medicine and Division Chief, Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. He disclosed relationships with Ethicon/Johnson & Johnson, Endogastric Solutions, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

References

1. Spechler SJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 17;381[16]:1513-23.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113[8]:1137-47.

3. Singhal S et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018 Feb;22[2]:177-86.

4. Ganz RA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May;14(5):671-7.

Endosc Int Open. 2019 May;7(5):E647-E654

As an esophagologist that does not perform fundoplication, LINX, or TIF, I find it difficult to debate the merits of one procedure over another based on my experience. In fact, I have always stated that it is difficult to assess a procedure or test that one has not used. That being said, maybe the fact that I have not performed these procedures makes me more objective and I can only use my experience with patients and the data to make the case that we need options beyond Nissen fundoplication.

The recent VA Randomized trial in refractory GERD published by Spechler and colleagues once again highlighted the fact that there are some patients that require a mechanical solution to reflux disease.1 In this study, the authors carefully defined a patient population with refractory GERD and showed that Nissen fundoplication was superior to medical management in patients who did not respond to proton pump inhibitors. However, of the 27 patients who underwent fundoplication, one patient had major complications which required a repeat operation and prolonged hospital stay. These findings highlight the main problem with Nissen fundoplication. Dr. Watson elegantly argued in his assertion during our debate that Nissen and fundoplication are not the same. In this position, he was noting the side effects associated with Nissen fundoplication,2 and he focused his argument on the comparison between a partial wrap versus LINX and TIF to level the playing field. On that note, I agree with Dr. Watson that a well-done partial fundoplication is a great option for patients with a mechanical problem.

Nonetheless, Redo operations have an escalating risk of severe debilitating consequences and we should do everything possible to reduce that risk.3 The LINX and the TIF procedure have data to support their effectiveness, and the initial studies a more favorable side effect profile.4,5 The ability to perform these procedures in patients with hiatal hernia and the fact that these approaches do not exclude the possibility of fundoplication in the future make them an attractive alternative.

In the end, more rigorous comparative studies should be performed to truly determine which approach is better. Although we have good surgical and medical options, we all recognize that they are not perfect and we should not settle on the current state of GERD management.

John E. Pandolfino, MD, MSCI, is the Hans Popper Professor of Medicine and Division Chief, Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. He disclosed relationships with Ethicon/Johnson & Johnson, Endogastric Solutions, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

References

1. Spechler SJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 17;381[16]:1513-23.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113[8]:1137-47.

3. Singhal S et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018 Feb;22[2]:177-86.

4. Ganz RA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May;14(5):671-7.

Endosc Int Open. 2019 May;7(5):E647-E654

As an esophagologist that does not perform fundoplication, LINX, or TIF, I find it difficult to debate the merits of one procedure over another based on my experience. In fact, I have always stated that it is difficult to assess a procedure or test that one has not used. That being said, maybe the fact that I have not performed these procedures makes me more objective and I can only use my experience with patients and the data to make the case that we need options beyond Nissen fundoplication.

The recent VA Randomized trial in refractory GERD published by Spechler and colleagues once again highlighted the fact that there are some patients that require a mechanical solution to reflux disease.1 In this study, the authors carefully defined a patient population with refractory GERD and showed that Nissen fundoplication was superior to medical management in patients who did not respond to proton pump inhibitors. However, of the 27 patients who underwent fundoplication, one patient had major complications which required a repeat operation and prolonged hospital stay. These findings highlight the main problem with Nissen fundoplication. Dr. Watson elegantly argued in his assertion during our debate that Nissen and fundoplication are not the same. In this position, he was noting the side effects associated with Nissen fundoplication,2 and he focused his argument on the comparison between a partial wrap versus LINX and TIF to level the playing field. On that note, I agree with Dr. Watson that a well-done partial fundoplication is a great option for patients with a mechanical problem.

Nonetheless, Redo operations have an escalating risk of severe debilitating consequences and we should do everything possible to reduce that risk.3 The LINX and the TIF procedure have data to support their effectiveness, and the initial studies a more favorable side effect profile.4,5 The ability to perform these procedures in patients with hiatal hernia and the fact that these approaches do not exclude the possibility of fundoplication in the future make them an attractive alternative.

In the end, more rigorous comparative studies should be performed to truly determine which approach is better. Although we have good surgical and medical options, we all recognize that they are not perfect and we should not settle on the current state of GERD management.

John E. Pandolfino, MD, MSCI, is the Hans Popper Professor of Medicine and Division Chief, Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Northwestern University, Chicago. He disclosed relationships with Ethicon/Johnson & Johnson, Endogastric Solutions, and Medtronic. These remarks were made during one of the AGA Postgraduate Course sessions held at DDW 2021.

References

1. Spechler SJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2019 Oct 17;381[16]:1513-23.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018 Aug;113[8]:1137-47.

3. Singhal S et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018 Feb;22[2]:177-86.

4. Ganz RA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 May;14(5):671-7.