User login

Sprint to find Zika vaccine could hinge on summer outbreaks

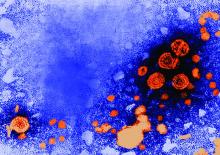

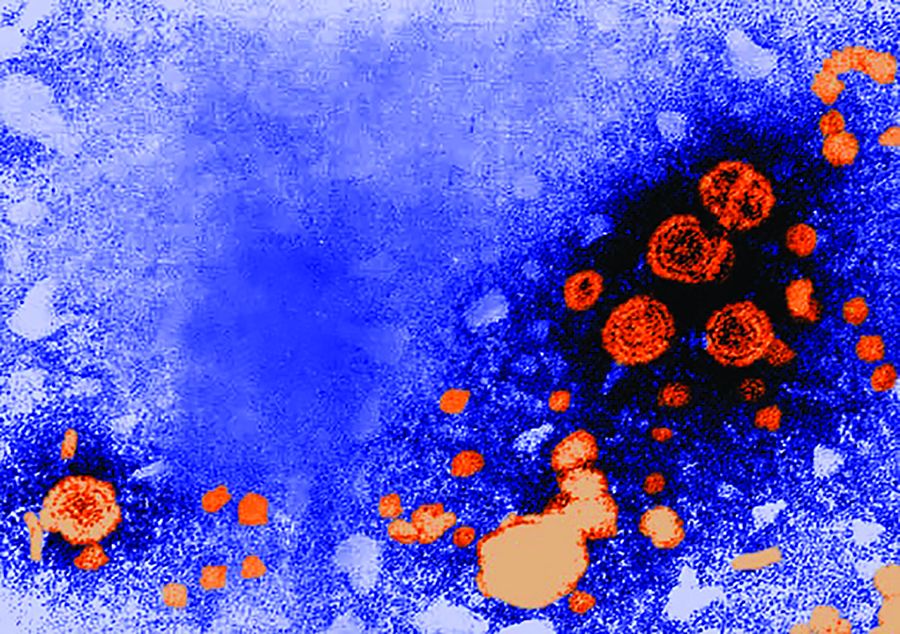

As warmer temperatures herald the arrival of pesky mosquitoes, researchers are feverishly working on several promising vaccines against Zika, a virus notorious for infecting humans through this insect’s bite.

The speed and debilitating effects of last year’s Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere prompted a sprint to develop a vaccine. Just a little more than a year after the pandemic was declared a global health emergency, a handful of candidates are undergoing preliminary testing in humans.

“On one hand, you don’t want to see outbreaks of infection,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “But on the other hand, [without that testing] you might have to wait a long time to make sure that the vaccine works.”

All the vaccines currently being tested are in phase I clinical trials, which means they are being tested for safety in a small number of people. According to a review paper published Tuesday in the journal Immunity, the vaccines represent a variety of scientific techniques to thwart the disease, ranging from inactivating the virus to manipulating its DNA.

The NIAID announced Tuesday it is launching yet another phase I trial for a vaccine made out of proteins found in mosquito saliva. The product is intended to trigger a human immune system response to the mosquito’s saliva and any viruses mixed with it. If successful, the product could protect humans against a spectrum of mosquito-transmitted diseases, including Zika.

Col. Nelson Michael, MD, PhD, director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and coauthor of the paper, said he expects preliminary reports on the safety of some of the older vaccines in April. As of now, he said, it is impossible to guess which vaccine will prove most effective in providing immunity.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to predict which horse will win the race,” Michael said.

Zika – which is spread from infected people to others by mosquito bites or sexual contact, often infects people without showing symptoms. In some cases, it causes flu-like symptoms, such as fever, muscle aches and joint pain in adults – and, in rare cases, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis. But it is most notorious for causing some children to be born with microcephaly – a birth defect in which a child’s head is smaller than the average size – if their mothers were exposed to Zika.

The virus garnered international attention after hundreds of cases of disabled babies surfaced in Brazil. It quickly swept through South America and the Caribbean before stopping on the southern coast of the U.S.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on Feb. 1, 2016, then ended the alert on Nov. 18.

Vaccines that meet the safety standard in phase I clinical trials undergo subsequent rounds of testing to gauge effectiveness. To measure this, researchers rely on the gold standard of administering the vaccine to large number of individuals already exposed to the virus. However, Zika’s recent arrival to the Western Hemisphere means researchers don’t know whether the virus will become a perennial threat or a one-time explosion.

The uncertainty poses several implications for the surge in Zika vaccine development. A lull in the outbreak could cause significant delays in testing, pushing back the timetable for a commercially available product, Dr. Fauci said.

While researchers can use alternative methods to measure efficacy without large-scale testing, a decline in the circulation of the Zika virus could set progress back by years because the vaccine testing would be ineffective.

“If we don’t get a lot of infections this season in South America and Puerto Rico, it may take years to make sure the vaccine works,” he said.

Dr. Fauci expects to launch the next round of human trials for a DNA vaccine developed by the NIAID next month.

Dr. Michael also worries that a lag in the number of Zika cases could lead the private sector to pull funds from vaccine development. It takes millions of dollars to develop a drug or vaccine, and pharmaceutical companies play a critical role in making and manufacturing them, he said. But those companies have many competing interests, he noted, and if it is hard to test a vaccine this year, the public and private Zika prevention efforts may turn attention elsewhere.

“This is a constant issue where you put your resources,” Dr. Michael said.

So far, signs suggest that the climate could be ripe for Zika again this year. Warmer-than-usual temperatures are affecting areas across the Western Hemisphere, CBS reported, including hotbeds of the Zika outbreaks in Brazil. The higher temperatures increase the voracity of Zika’s main transmitter, the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

In the United States, areas with populations of the Aedes aegypti are closely monitoring their numbers. Last year, Texas and Florida dealt with locally acquired cases of Zika infection.

In Texas, public health officials have monitored mosquito populations throughout the winter to track their numbers and any presence of the virus. Despite unseasonably warm weather, said Chris Van Deusen, spokesman for the Texas Department of State Health Services, they have seen lower numbers of the Aedes aegypti and no cases of Zika.

Mr. Van Deusen said the state is also monitoring the outbreak in Mexico, since heavy traffic across the border increases the possibility of transmission. Officials are expecting another outbreak of locally transmitted cases of disease, Mr. Van Deusen said.

“There’s so many factors that go into it, it’s really impossible to make an ironclad prediction,” he said.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

As warmer temperatures herald the arrival of pesky mosquitoes, researchers are feverishly working on several promising vaccines against Zika, a virus notorious for infecting humans through this insect’s bite.

The speed and debilitating effects of last year’s Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere prompted a sprint to develop a vaccine. Just a little more than a year after the pandemic was declared a global health emergency, a handful of candidates are undergoing preliminary testing in humans.

“On one hand, you don’t want to see outbreaks of infection,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “But on the other hand, [without that testing] you might have to wait a long time to make sure that the vaccine works.”

All the vaccines currently being tested are in phase I clinical trials, which means they are being tested for safety in a small number of people. According to a review paper published Tuesday in the journal Immunity, the vaccines represent a variety of scientific techniques to thwart the disease, ranging from inactivating the virus to manipulating its DNA.

The NIAID announced Tuesday it is launching yet another phase I trial for a vaccine made out of proteins found in mosquito saliva. The product is intended to trigger a human immune system response to the mosquito’s saliva and any viruses mixed with it. If successful, the product could protect humans against a spectrum of mosquito-transmitted diseases, including Zika.

Col. Nelson Michael, MD, PhD, director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and coauthor of the paper, said he expects preliminary reports on the safety of some of the older vaccines in April. As of now, he said, it is impossible to guess which vaccine will prove most effective in providing immunity.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to predict which horse will win the race,” Michael said.

Zika – which is spread from infected people to others by mosquito bites or sexual contact, often infects people without showing symptoms. In some cases, it causes flu-like symptoms, such as fever, muscle aches and joint pain in adults – and, in rare cases, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis. But it is most notorious for causing some children to be born with microcephaly – a birth defect in which a child’s head is smaller than the average size – if their mothers were exposed to Zika.

The virus garnered international attention after hundreds of cases of disabled babies surfaced in Brazil. It quickly swept through South America and the Caribbean before stopping on the southern coast of the U.S.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on Feb. 1, 2016, then ended the alert on Nov. 18.

Vaccines that meet the safety standard in phase I clinical trials undergo subsequent rounds of testing to gauge effectiveness. To measure this, researchers rely on the gold standard of administering the vaccine to large number of individuals already exposed to the virus. However, Zika’s recent arrival to the Western Hemisphere means researchers don’t know whether the virus will become a perennial threat or a one-time explosion.

The uncertainty poses several implications for the surge in Zika vaccine development. A lull in the outbreak could cause significant delays in testing, pushing back the timetable for a commercially available product, Dr. Fauci said.

While researchers can use alternative methods to measure efficacy without large-scale testing, a decline in the circulation of the Zika virus could set progress back by years because the vaccine testing would be ineffective.

“If we don’t get a lot of infections this season in South America and Puerto Rico, it may take years to make sure the vaccine works,” he said.

Dr. Fauci expects to launch the next round of human trials for a DNA vaccine developed by the NIAID next month.

Dr. Michael also worries that a lag in the number of Zika cases could lead the private sector to pull funds from vaccine development. It takes millions of dollars to develop a drug or vaccine, and pharmaceutical companies play a critical role in making and manufacturing them, he said. But those companies have many competing interests, he noted, and if it is hard to test a vaccine this year, the public and private Zika prevention efforts may turn attention elsewhere.

“This is a constant issue where you put your resources,” Dr. Michael said.

So far, signs suggest that the climate could be ripe for Zika again this year. Warmer-than-usual temperatures are affecting areas across the Western Hemisphere, CBS reported, including hotbeds of the Zika outbreaks in Brazil. The higher temperatures increase the voracity of Zika’s main transmitter, the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

In the United States, areas with populations of the Aedes aegypti are closely monitoring their numbers. Last year, Texas and Florida dealt with locally acquired cases of Zika infection.

In Texas, public health officials have monitored mosquito populations throughout the winter to track their numbers and any presence of the virus. Despite unseasonably warm weather, said Chris Van Deusen, spokesman for the Texas Department of State Health Services, they have seen lower numbers of the Aedes aegypti and no cases of Zika.

Mr. Van Deusen said the state is also monitoring the outbreak in Mexico, since heavy traffic across the border increases the possibility of transmission. Officials are expecting another outbreak of locally transmitted cases of disease, Mr. Van Deusen said.

“There’s so many factors that go into it, it’s really impossible to make an ironclad prediction,” he said.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

As warmer temperatures herald the arrival of pesky mosquitoes, researchers are feverishly working on several promising vaccines against Zika, a virus notorious for infecting humans through this insect’s bite.

The speed and debilitating effects of last year’s Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere prompted a sprint to develop a vaccine. Just a little more than a year after the pandemic was declared a global health emergency, a handful of candidates are undergoing preliminary testing in humans.

“On one hand, you don’t want to see outbreaks of infection,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “But on the other hand, [without that testing] you might have to wait a long time to make sure that the vaccine works.”

All the vaccines currently being tested are in phase I clinical trials, which means they are being tested for safety in a small number of people. According to a review paper published Tuesday in the journal Immunity, the vaccines represent a variety of scientific techniques to thwart the disease, ranging from inactivating the virus to manipulating its DNA.

The NIAID announced Tuesday it is launching yet another phase I trial for a vaccine made out of proteins found in mosquito saliva. The product is intended to trigger a human immune system response to the mosquito’s saliva and any viruses mixed with it. If successful, the product could protect humans against a spectrum of mosquito-transmitted diseases, including Zika.

Col. Nelson Michael, MD, PhD, director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and coauthor of the paper, said he expects preliminary reports on the safety of some of the older vaccines in April. As of now, he said, it is impossible to guess which vaccine will prove most effective in providing immunity.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to predict which horse will win the race,” Michael said.

Zika – which is spread from infected people to others by mosquito bites or sexual contact, often infects people without showing symptoms. In some cases, it causes flu-like symptoms, such as fever, muscle aches and joint pain in adults – and, in rare cases, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis. But it is most notorious for causing some children to be born with microcephaly – a birth defect in which a child’s head is smaller than the average size – if their mothers were exposed to Zika.

The virus garnered international attention after hundreds of cases of disabled babies surfaced in Brazil. It quickly swept through South America and the Caribbean before stopping on the southern coast of the U.S.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on Feb. 1, 2016, then ended the alert on Nov. 18.

Vaccines that meet the safety standard in phase I clinical trials undergo subsequent rounds of testing to gauge effectiveness. To measure this, researchers rely on the gold standard of administering the vaccine to large number of individuals already exposed to the virus. However, Zika’s recent arrival to the Western Hemisphere means researchers don’t know whether the virus will become a perennial threat or a one-time explosion.

The uncertainty poses several implications for the surge in Zika vaccine development. A lull in the outbreak could cause significant delays in testing, pushing back the timetable for a commercially available product, Dr. Fauci said.

While researchers can use alternative methods to measure efficacy without large-scale testing, a decline in the circulation of the Zika virus could set progress back by years because the vaccine testing would be ineffective.

“If we don’t get a lot of infections this season in South America and Puerto Rico, it may take years to make sure the vaccine works,” he said.

Dr. Fauci expects to launch the next round of human trials for a DNA vaccine developed by the NIAID next month.

Dr. Michael also worries that a lag in the number of Zika cases could lead the private sector to pull funds from vaccine development. It takes millions of dollars to develop a drug or vaccine, and pharmaceutical companies play a critical role in making and manufacturing them, he said. But those companies have many competing interests, he noted, and if it is hard to test a vaccine this year, the public and private Zika prevention efforts may turn attention elsewhere.

“This is a constant issue where you put your resources,” Dr. Michael said.

So far, signs suggest that the climate could be ripe for Zika again this year. Warmer-than-usual temperatures are affecting areas across the Western Hemisphere, CBS reported, including hotbeds of the Zika outbreaks in Brazil. The higher temperatures increase the voracity of Zika’s main transmitter, the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

In the United States, areas with populations of the Aedes aegypti are closely monitoring their numbers. Last year, Texas and Florida dealt with locally acquired cases of Zika infection.

In Texas, public health officials have monitored mosquito populations throughout the winter to track their numbers and any presence of the virus. Despite unseasonably warm weather, said Chris Van Deusen, spokesman for the Texas Department of State Health Services, they have seen lower numbers of the Aedes aegypti and no cases of Zika.

Mr. Van Deusen said the state is also monitoring the outbreak in Mexico, since heavy traffic across the border increases the possibility of transmission. Officials are expecting another outbreak of locally transmitted cases of disease, Mr. Van Deusen said.

“There’s so many factors that go into it, it’s really impossible to make an ironclad prediction,” he said.

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Preterm infants at higher risk of pertussis

Preterm infants are at greater risk for pertussis than full-term infants, according to a population-based study from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Øystein Rolandsen Riise, MD, PhD, of the institute, and his colleagues identified all live births in Norway from 1998 to 2010 from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway and studied the gestational age of 713,166 infants as an indicator of increased risk of pertussis.

Infants born at 23-27 weeks of gestational age had an incidence rate ratio of pertussis more than fourfold higher than term infants (IRR = 4.49), while those born at 32-34 weeks and 35-36 weeks each had an IRR about 1.5 time higher than term infants (Pediatr Infect Dis J. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

The IRR of preterm infants hospitalized with pertussis was double that of full-term infants (IRR = 1.99).

The increased risk in preterm infants could be attributed to an incomplete transfer of maternal antibodies, specifically the “abundance of IgG [that] is acquired during the last month of full-term pregnancy,” Dr. Riise and colleagues wrote.

While previous studies have found links between preterm birth and pertussis infection, those studies used birth weight instead of gestational age, which leads to possibly inaccurate results, they added.

“Although other studies have used low birth weight to identify infants with increased risk of pertussis, we would have underestimated the number of infants with increased risk by using low birth weight instead of gestational age, since many of the late preterm infants have normal birth weight,” the researchers noted.

Early vaccination is key to protecting preterm infants from pertussis, Dr. Riise and colleagues said, adding that vaccine effectiveness was similar between preterm (93%) and full-term (88.8%) infants.

Preterm infants are at greater risk for pertussis than full-term infants, according to a population-based study from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Øystein Rolandsen Riise, MD, PhD, of the institute, and his colleagues identified all live births in Norway from 1998 to 2010 from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway and studied the gestational age of 713,166 infants as an indicator of increased risk of pertussis.

Infants born at 23-27 weeks of gestational age had an incidence rate ratio of pertussis more than fourfold higher than term infants (IRR = 4.49), while those born at 32-34 weeks and 35-36 weeks each had an IRR about 1.5 time higher than term infants (Pediatr Infect Dis J. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

The IRR of preterm infants hospitalized with pertussis was double that of full-term infants (IRR = 1.99).

The increased risk in preterm infants could be attributed to an incomplete transfer of maternal antibodies, specifically the “abundance of IgG [that] is acquired during the last month of full-term pregnancy,” Dr. Riise and colleagues wrote.

While previous studies have found links between preterm birth and pertussis infection, those studies used birth weight instead of gestational age, which leads to possibly inaccurate results, they added.

“Although other studies have used low birth weight to identify infants with increased risk of pertussis, we would have underestimated the number of infants with increased risk by using low birth weight instead of gestational age, since many of the late preterm infants have normal birth weight,” the researchers noted.

Early vaccination is key to protecting preterm infants from pertussis, Dr. Riise and colleagues said, adding that vaccine effectiveness was similar between preterm (93%) and full-term (88.8%) infants.

Preterm infants are at greater risk for pertussis than full-term infants, according to a population-based study from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Øystein Rolandsen Riise, MD, PhD, of the institute, and his colleagues identified all live births in Norway from 1998 to 2010 from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway and studied the gestational age of 713,166 infants as an indicator of increased risk of pertussis.

Infants born at 23-27 weeks of gestational age had an incidence rate ratio of pertussis more than fourfold higher than term infants (IRR = 4.49), while those born at 32-34 weeks and 35-36 weeks each had an IRR about 1.5 time higher than term infants (Pediatr Infect Dis J. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001545).

The IRR of preterm infants hospitalized with pertussis was double that of full-term infants (IRR = 1.99).

The increased risk in preterm infants could be attributed to an incomplete transfer of maternal antibodies, specifically the “abundance of IgG [that] is acquired during the last month of full-term pregnancy,” Dr. Riise and colleagues wrote.

While previous studies have found links between preterm birth and pertussis infection, those studies used birth weight instead of gestational age, which leads to possibly inaccurate results, they added.

“Although other studies have used low birth weight to identify infants with increased risk of pertussis, we would have underestimated the number of infants with increased risk by using low birth weight instead of gestational age, since many of the late preterm infants have normal birth weight,” the researchers noted.

Early vaccination is key to protecting preterm infants from pertussis, Dr. Riise and colleagues said, adding that vaccine effectiveness was similar between preterm (93%) and full-term (88.8%) infants.

FROM PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The risk of pertussis infection was 4.49-fold higher in infants with a gestational age of 23-27 weeks.

Data source: A cohort study of 713,166 children from the Medical Birth Registry of Norway with a gestation period of 23-37 weeks during 1998-2010.

Disclosures: No funding was secured for this study. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Inactivated hepatitis A vaccine shows promise in 5-year study

, a study has shown.

In October 2008, a team of investigators in China led by Zhilun Zhang of the Tianjin Center for Disease Control and Prevention, randomly assigned 332 children aged 18-60 months with prevaccination anti-HAV antibody titers of less than 20 mIU/mL to receive either one dose of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine or one dose of live, attenuated hepatitis A vaccine. Both groups were followed through December 2013, with assessments of anti-HAV antibody concentrations at years 1, 2, and 5 post vaccination. In all, 182 successfully completed the study, meeting all requirements, including providing serum samples at each time point.

Titer levels were 76.3% mIU/mL and 66.8mIU/mL for the inactivated and live vaccines at 5 years, respectively. No clinical hepatitis A case was reported.

The study appears online in Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics (doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1278329).

, a study has shown.

In October 2008, a team of investigators in China led by Zhilun Zhang of the Tianjin Center for Disease Control and Prevention, randomly assigned 332 children aged 18-60 months with prevaccination anti-HAV antibody titers of less than 20 mIU/mL to receive either one dose of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine or one dose of live, attenuated hepatitis A vaccine. Both groups were followed through December 2013, with assessments of anti-HAV antibody concentrations at years 1, 2, and 5 post vaccination. In all, 182 successfully completed the study, meeting all requirements, including providing serum samples at each time point.

Titer levels were 76.3% mIU/mL and 66.8mIU/mL for the inactivated and live vaccines at 5 years, respectively. No clinical hepatitis A case was reported.

The study appears online in Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics (doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1278329).

, a study has shown.

In October 2008, a team of investigators in China led by Zhilun Zhang of the Tianjin Center for Disease Control and Prevention, randomly assigned 332 children aged 18-60 months with prevaccination anti-HAV antibody titers of less than 20 mIU/mL to receive either one dose of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine or one dose of live, attenuated hepatitis A vaccine. Both groups were followed through December 2013, with assessments of anti-HAV antibody concentrations at years 1, 2, and 5 post vaccination. In all, 182 successfully completed the study, meeting all requirements, including providing serum samples at each time point.

Titer levels were 76.3% mIU/mL and 66.8mIU/mL for the inactivated and live vaccines at 5 years, respectively. No clinical hepatitis A case was reported.

The study appears online in Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics (doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1278329).

FROM HUMAN VACCINES & IMMUNOTHERAPEUTICS

ACIP approves minor changes to pediatric hepatitis B vaccine recommendations

Approval to changes of current recommendations for hepatitis B vaccinations for children were voted on by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The 14-member panel voted to approve changes to existing language, which states that infants who are HBsAg negative with anti-HBs levels of less than 10 mIU/mL should be revaccinated with a second three-dose series and retested within 2 months of the series’ final dose. The approved proposal will change that language to state that these infants should receive only one dose, not the entire series of three. However, if anti-HBs levels remain lower than 10 mIU/mL after the one dose, the remaining two vaccinations should be administered, along with testing within 2 months of the final dose.

The other change, a relatively minor one, affects the wording of the recommendations regarding the Vaccines for Children program. In addition to incorporating a language change similar to the aforementioned one – the only difference being that now, the recommendations will explicitly mention postvaccination serologic testing within 2 months of series completion – under the minimum dosing intervals for interrupted vaccination schedules, the second bullet has been modified to say “final dose” instead of “third dose,” as it currently does.

“[This is] to address potential confusion related to different schedules when single-antigen or combination vaccines are used,” explained Jeanne Santoli, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, adding that “the eligible groups are unchanged, schedule and intervals are unchanged, [so] the purpose is to clarify related to dosing intervals and revaccination.”

Both votes were approved of nearly unanimously, with 13 committee members voting to approve while 1 – José R. Romero, MD, who holds the Horace C. Cabe Endowed Chair in Pediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock – abstained because of potential conflicts of interest.

Approval by ACIP does not automatically mean that these changes will go into effect; they must first be approved by CDC director Tom Frieden, MD. However, the CDC generally follows ACIP guidance.

Approval to changes of current recommendations for hepatitis B vaccinations for children were voted on by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The 14-member panel voted to approve changes to existing language, which states that infants who are HBsAg negative with anti-HBs levels of less than 10 mIU/mL should be revaccinated with a second three-dose series and retested within 2 months of the series’ final dose. The approved proposal will change that language to state that these infants should receive only one dose, not the entire series of three. However, if anti-HBs levels remain lower than 10 mIU/mL after the one dose, the remaining two vaccinations should be administered, along with testing within 2 months of the final dose.

The other change, a relatively minor one, affects the wording of the recommendations regarding the Vaccines for Children program. In addition to incorporating a language change similar to the aforementioned one – the only difference being that now, the recommendations will explicitly mention postvaccination serologic testing within 2 months of series completion – under the minimum dosing intervals for interrupted vaccination schedules, the second bullet has been modified to say “final dose” instead of “third dose,” as it currently does.

“[This is] to address potential confusion related to different schedules when single-antigen or combination vaccines are used,” explained Jeanne Santoli, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, adding that “the eligible groups are unchanged, schedule and intervals are unchanged, [so] the purpose is to clarify related to dosing intervals and revaccination.”

Both votes were approved of nearly unanimously, with 13 committee members voting to approve while 1 – José R. Romero, MD, who holds the Horace C. Cabe Endowed Chair in Pediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock – abstained because of potential conflicts of interest.

Approval by ACIP does not automatically mean that these changes will go into effect; they must first be approved by CDC director Tom Frieden, MD. However, the CDC generally follows ACIP guidance.

Approval to changes of current recommendations for hepatitis B vaccinations for children were voted on by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

The 14-member panel voted to approve changes to existing language, which states that infants who are HBsAg negative with anti-HBs levels of less than 10 mIU/mL should be revaccinated with a second three-dose series and retested within 2 months of the series’ final dose. The approved proposal will change that language to state that these infants should receive only one dose, not the entire series of three. However, if anti-HBs levels remain lower than 10 mIU/mL after the one dose, the remaining two vaccinations should be administered, along with testing within 2 months of the final dose.

The other change, a relatively minor one, affects the wording of the recommendations regarding the Vaccines for Children program. In addition to incorporating a language change similar to the aforementioned one – the only difference being that now, the recommendations will explicitly mention postvaccination serologic testing within 2 months of series completion – under the minimum dosing intervals for interrupted vaccination schedules, the second bullet has been modified to say “final dose” instead of “third dose,” as it currently does.

“[This is] to address potential confusion related to different schedules when single-antigen or combination vaccines are used,” explained Jeanne Santoli, MD, of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, adding that “the eligible groups are unchanged, schedule and intervals are unchanged, [so] the purpose is to clarify related to dosing intervals and revaccination.”

Both votes were approved of nearly unanimously, with 13 committee members voting to approve while 1 – José R. Romero, MD, who holds the Horace C. Cabe Endowed Chair in Pediatric Infectious Diseases at the University of Arkansas in Little Rock – abstained because of potential conflicts of interest.

Approval by ACIP does not automatically mean that these changes will go into effect; they must first be approved by CDC director Tom Frieden, MD. However, the CDC generally follows ACIP guidance.

Pertussis susceptibility estimates call for public health push

, according to results of research by Lana Childs and Robert A. Bednarczyk, PhD.

There were 32,971 pertussis cases reported in 2014, a 15% increase over 2013; most cases occurred in children who were too young to be fully vaccinated and in preadolescents with waning immunity from their vaccines. In the United States, vaccine coverage during childhood tends to be high overall, but DTaP coverage (84% in 2014) “remains lower than coverage for other childhood vaccinations,” they noted.

“These findings emphasize the need for public health professionals to continue efforts to increase DTaP vaccine coverage in children and Tdap coverage in pregnant women, plan for potential outbreaks, and maintain immunity levels needed to prevent the spread of pertussis.” the investigators concluded.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001537).

, according to results of research by Lana Childs and Robert A. Bednarczyk, PhD.

There were 32,971 pertussis cases reported in 2014, a 15% increase over 2013; most cases occurred in children who were too young to be fully vaccinated and in preadolescents with waning immunity from their vaccines. In the United States, vaccine coverage during childhood tends to be high overall, but DTaP coverage (84% in 2014) “remains lower than coverage for other childhood vaccinations,” they noted.

“These findings emphasize the need for public health professionals to continue efforts to increase DTaP vaccine coverage in children and Tdap coverage in pregnant women, plan for potential outbreaks, and maintain immunity levels needed to prevent the spread of pertussis.” the investigators concluded.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001537).

, according to results of research by Lana Childs and Robert A. Bednarczyk, PhD.

There were 32,971 pertussis cases reported in 2014, a 15% increase over 2013; most cases occurred in children who were too young to be fully vaccinated and in preadolescents with waning immunity from their vaccines. In the United States, vaccine coverage during childhood tends to be high overall, but DTaP coverage (84% in 2014) “remains lower than coverage for other childhood vaccinations,” they noted.

“These findings emphasize the need for public health professionals to continue efforts to increase DTaP vaccine coverage in children and Tdap coverage in pregnant women, plan for potential outbreaks, and maintain immunity levels needed to prevent the spread of pertussis.” the investigators concluded.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001537).

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

Study: No link between vaccines, inhibitor development

The administration of pediatric vaccinations in close proximity to factor VIII (FVIII) exposure was not associated with inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with severe hemophilia A in the PedNet Registry.

Similarly, no association was seen between recurrent vaccinations and inhibitor development, Dr. van den Berg reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

Inhibitor development in this patient population is a multifactorial event, but these findings show no association between vaccinations administered early in life and increased inhibitor risk, she concluded.

Dr. van den Berg received grant/research support from Bayer, Baxalta, Pfizer, CSI, and Grifols.

The administration of pediatric vaccinations in close proximity to factor VIII (FVIII) exposure was not associated with inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with severe hemophilia A in the PedNet Registry.

Similarly, no association was seen between recurrent vaccinations and inhibitor development, Dr. van den Berg reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

Inhibitor development in this patient population is a multifactorial event, but these findings show no association between vaccinations administered early in life and increased inhibitor risk, she concluded.

Dr. van den Berg received grant/research support from Bayer, Baxalta, Pfizer, CSI, and Grifols.

The administration of pediatric vaccinations in close proximity to factor VIII (FVIII) exposure was not associated with inhibitor development in previously untreated patients with severe hemophilia A in the PedNet Registry.

Similarly, no association was seen between recurrent vaccinations and inhibitor development, Dr. van den Berg reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for Haemophilia and Allied Disorders.

Inhibitor development in this patient population is a multifactorial event, but these findings show no association between vaccinations administered early in life and increased inhibitor risk, she concluded.

Dr. van den Berg received grant/research support from Bayer, Baxalta, Pfizer, CSI, and Grifols.

FROM EAHAD 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The adjusted hazard ratio for any inhibitor development related to vaccinations in close proximity to FVIII was 0.65.

Data source: A review of data from 375 children in the PedNet Registry.

Disclosures: Dr. van den Berg received grant/research support from Bayer, Baxalta, Pfizer, CSI, and Grifols.

Review offers reassurance on prenatal Tdap vaccination safety

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Combined tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) vaccination during the second or third trimester of pregnancy does not appear to be associated with clinically significant harm to the fetus or neonate, according to findings from a systematic review of the literature.

However, the findings are limited by a dearth of randomized, placebo-controlled trials.

Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60, Mark McMillan of the University of Adelaide, North Adelaide, Australia and his colleagues reported (Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:560-73).

“Statistical imprecision for combined ‘all anomalies’ outcomes meant that upper 95% [confidence intervals] were 2.0 or above,” the researchers wrote. “Statistical imprecision was even greater in the individual congenital anomaly outcomes and little confidence can be placed in these estimates.”

Additionally, one of three studies assessing chorioamnionitis showed a small but significant increase in risk (relative risk, 1.19) after vaccination.

Among the studies examining medically attended adverse events, no association was seen between vaccination and such events or reactions, including neurologic events, gestational diabetes, preeclampsia or eclampsia, and cardiac events. Maternal effects included fever in 1%-3% of subjects, and headache, malaise, and myalgia, which were more common.

“Overall, despite the limitations described, the review offers reassurance for antenatal Tdap or Tdap-IPV [diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and polio] vaccination administered during the second or third trimester of pregnancy,” the researchers wrote. “These findings need to be interpreted in the context of the evidence of effectiveness of antenatal vaccination programs at preventing serious morbidity and mortality from pertussis in young infants.”

Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Point estimates for all anomalies after Tdap vaccination ranged from 1.20 to 1.60.

Data source: A systematic review of 21 studies.

Disclosures: Mr. McMillan received travel support from GlaxoSmithKline, and institutional research grants from GSK and Sanofi Pasteur. Other researchers also reported receiving research funding and/or travel support from these companies.

Adverse event reporting in second-dose varicella vaccination shows no surprises

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

No new or unexpected adverse events were reported in association with second-dose varicella vaccination in children age 4-18 years during 2006-2014.

During the study period of 2006-2014, 14,641 reports regarding second-dose varicella vaccinations were made to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, according to John Su, MD, PhD, and his associates. Of these reports, only 3% were serious adverse events (AE), with the most common nonserious AE being injection-site reaction, which occurred in 48% of patients age 4-6 years reporting AEs, and in 38% of patients age 7-18 years reporting AEs.

Of the 494 serious AEs reported, pyrexia was the most common in children age 4-6 years, and headache and vomiting were the most common in children age 7-18 years. A total of seven deaths from various causes were reported, though no causal relation to vaccination was seen, and significant chronic medical problems were common in these children.

“The safety data on second-dose varicella vaccination are reassuring,” the investigators noted. “Reported AEs after second-dose varicella vaccination were mild, self limiting, and similar in reported frequency to AEs after first-dose vaccination, with no new or unexpected safety concerns.”

Find the full study in Pediatrics (2017 Feb 7. doi: 1542/peds.2016-2536).

Teen vaccines: Where we are now, and how can we go further?

Adolescents remain undervaccinated for several diseases, and clinicians need to lead the charge to change this reality, according to new clinical reports issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases.

Teens are lagging behind the Healthy People 2020 vaccination goals for the Tdap, quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate (menACWY), and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, lead authors Henry H. Bernstein, DO, and Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, wrote in the Feb. 6 issue of Pediatrics.

“Although HPV vaccination rates are slowly improving, they continue to lag far behind Tdap and menACWY rates for both boys and girls,” the authors wrote. Only 63% of girls and 50% of boys have gotten at least one HPV vaccine dose; just 42% of girls and 28% of boys finished the entire three-dose series in 2015.

A recent study found that parents declined the HPV vaccine 56% of the time. The three most common reasons were the belief that their child had a low risk of acquiring HPV; fear that the risk of adverse events was too great and belief that the vaccine wasn’t well researched and hasn’t been on the market long enough.

But teens also are falling behind with less controversial vaccines, the report noted. Fewer than half of teens got a flu shot in the 2015-2016 season. Rates for the MenACWY and Tdap are better, but not optimal (81% and 86%, respectively).

Barriers to optimal immunization

The clinical report puts clinicians on the first line of responsibility and makes no apologies for that.

“One of the greatest challenges is health care provider recommendation, which often lacks consistency and urgency,” the authors said. “Many health care providers do not universally recommend vaccines to eligible populations and do not offer concomitant vaccination with indicated vaccines during a single patient encounter.”

In fact, they noted, a recent physician survey found that only about 60% of pediatricians and family doctors strongly recommend the HPV vaccine for 11- and 12-year-old girls. Several parent surveys have determined that lack of provider recommendation is a leading reason for undervaccination among adolescents.

A companion clinical report, also authored by Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini, discusses practical ways to confront these barriers (Pediatrics. 2017 Feb 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4187). It opens with a strong call to physicians to lead the charge in increasing immunization rates.

“Up to 65% of parents have reported not receiving a recommendation … for immunizations. The major reason for nonreceipt [of Tdap and menACWY] was lack of a health care provider recommendation,” they said.

Overcoming parental vaccine hesitancy is a thorny struggle, the authors acknowledge. But they offer some helpful suggestions, including:

• Don’t offer immunizations as “optional.” This opens the door to vaccine dismissal. Instead, “strongly endorse all universally recommended vaccines as important for adolescents’ health.”

• Ask open-ended questions to get at the root of parental hesitancy. Give fact-based, medically sound information. Stress that doctors are parent partners in raising healthy children and protecting them from disease.

• Stress the big-picture benefits of vaccines. Telling parents that the HPV vaccine prevents cancer lifelong is a powerful message. “Up-to-date information on current events and disease outbreaks is a tool to bring into the conversation about vaccines as well.”

• Review the vaccine timeline. Do everything possible to ensure parents follow up and complete each series. “Follow-up immunization visits should be scheduled before the family leaves the care setting.”

• Don’t give up when a parent refuses a vaccine. “Although it may be challenging, it’s important that health care providers offer the vaccine at the next most appropriate time. Perseverance is critical for vaccine uptake and immunization rates.”

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini also suggest that vaccine uptake could be boosted by a mental re-set of the office visit. “Missed opportunities for adolescent immunizations,” such as sick calls, are a prime example. “The majority of vaccines are administered during well-child visit [sports or camp physicals]. … However, acute care visits or sick visits in the patient-centered medical home are also an opportunity to deliver vaccines or to discuss upcoming vaccines,” they said.

Education and communication are essential to improving vaccine uptake, the report concludes. “Appropriate techniques for approaching adolescent patients and their parents in the office to encourage immunizations are important skills for healthcare providers. The key to increasing immunization rates and decreasing vaccine-preventable disease … is to focus on educating adolescents and strengthening health care providers’ recommendations by using all clinical opportunities to assess immunization status and provide needed vaccinations.”

Neither Dr Bernstein nor Dr. Bocchini had any financial disclosures.

Need help talking about teen vaccines? Check out these resources

The American Academy of Pediatrics offered the following resources designed to help clinicians communicate effectively when talking to patients and parents about vaccines:

• Talking to parents about the HPV vaccine. This website hosted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention includes a link to the latest vaccination recommendations, as well as a tip sheet with HPV vaccine talking points, a fact sheet on the vaccine’s safety data, and a video with four clinical vignettes that model effective communication.

• The HPV Champion Toolkit. This contains numerous resources to help clinicians learn to educate other health care professionals, discuss HPV vaccination with parents, and make practice changes to increase HPV vaccine uptake.

• You Are the Key to HPV Prevention. This CDC video presents up-to-date information on HPV infection and disease, the HPV vaccine, and ways to successfully communicate with patients and their parents about HPV vaccination.

• Adolescentvaccination.org. The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases maintains a website is entirely devoted to adolescent vaccination issues. It contains resources for clinicians, and parents.

• Top Strategies for Increasing Vaccine Coverage. This is a report by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

• You Call the Shots. This is an interactive, Web-based immunization training course created by the CDC.

• Suggestions to Improve Your Immunization Services. This is a checklist of suggestions, by the Immunization Action.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Adolescents remain undervaccinated for several diseases, and clinicians need to lead the charge to change this reality, according to new clinical reports issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases.

Teens are lagging behind the Healthy People 2020 vaccination goals for the Tdap, quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate (menACWY), and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, lead authors Henry H. Bernstein, DO, and Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, wrote in the Feb. 6 issue of Pediatrics.

“Although HPV vaccination rates are slowly improving, they continue to lag far behind Tdap and menACWY rates for both boys and girls,” the authors wrote. Only 63% of girls and 50% of boys have gotten at least one HPV vaccine dose; just 42% of girls and 28% of boys finished the entire three-dose series in 2015.

A recent study found that parents declined the HPV vaccine 56% of the time. The three most common reasons were the belief that their child had a low risk of acquiring HPV; fear that the risk of adverse events was too great and belief that the vaccine wasn’t well researched and hasn’t been on the market long enough.

But teens also are falling behind with less controversial vaccines, the report noted. Fewer than half of teens got a flu shot in the 2015-2016 season. Rates for the MenACWY and Tdap are better, but not optimal (81% and 86%, respectively).

Barriers to optimal immunization

The clinical report puts clinicians on the first line of responsibility and makes no apologies for that.

“One of the greatest challenges is health care provider recommendation, which often lacks consistency and urgency,” the authors said. “Many health care providers do not universally recommend vaccines to eligible populations and do not offer concomitant vaccination with indicated vaccines during a single patient encounter.”

In fact, they noted, a recent physician survey found that only about 60% of pediatricians and family doctors strongly recommend the HPV vaccine for 11- and 12-year-old girls. Several parent surveys have determined that lack of provider recommendation is a leading reason for undervaccination among adolescents.

A companion clinical report, also authored by Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini, discusses practical ways to confront these barriers (Pediatrics. 2017 Feb 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4187). It opens with a strong call to physicians to lead the charge in increasing immunization rates.

“Up to 65% of parents have reported not receiving a recommendation … for immunizations. The major reason for nonreceipt [of Tdap and menACWY] was lack of a health care provider recommendation,” they said.

Overcoming parental vaccine hesitancy is a thorny struggle, the authors acknowledge. But they offer some helpful suggestions, including:

• Don’t offer immunizations as “optional.” This opens the door to vaccine dismissal. Instead, “strongly endorse all universally recommended vaccines as important for adolescents’ health.”

• Ask open-ended questions to get at the root of parental hesitancy. Give fact-based, medically sound information. Stress that doctors are parent partners in raising healthy children and protecting them from disease.

• Stress the big-picture benefits of vaccines. Telling parents that the HPV vaccine prevents cancer lifelong is a powerful message. “Up-to-date information on current events and disease outbreaks is a tool to bring into the conversation about vaccines as well.”

• Review the vaccine timeline. Do everything possible to ensure parents follow up and complete each series. “Follow-up immunization visits should be scheduled before the family leaves the care setting.”

• Don’t give up when a parent refuses a vaccine. “Although it may be challenging, it’s important that health care providers offer the vaccine at the next most appropriate time. Perseverance is critical for vaccine uptake and immunization rates.”

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini also suggest that vaccine uptake could be boosted by a mental re-set of the office visit. “Missed opportunities for adolescent immunizations,” such as sick calls, are a prime example. “The majority of vaccines are administered during well-child visit [sports or camp physicals]. … However, acute care visits or sick visits in the patient-centered medical home are also an opportunity to deliver vaccines or to discuss upcoming vaccines,” they said.

Education and communication are essential to improving vaccine uptake, the report concludes. “Appropriate techniques for approaching adolescent patients and their parents in the office to encourage immunizations are important skills for healthcare providers. The key to increasing immunization rates and decreasing vaccine-preventable disease … is to focus on educating adolescents and strengthening health care providers’ recommendations by using all clinical opportunities to assess immunization status and provide needed vaccinations.”

Neither Dr Bernstein nor Dr. Bocchini had any financial disclosures.

Need help talking about teen vaccines? Check out these resources

The American Academy of Pediatrics offered the following resources designed to help clinicians communicate effectively when talking to patients and parents about vaccines:

• Talking to parents about the HPV vaccine. This website hosted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention includes a link to the latest vaccination recommendations, as well as a tip sheet with HPV vaccine talking points, a fact sheet on the vaccine’s safety data, and a video with four clinical vignettes that model effective communication.

• The HPV Champion Toolkit. This contains numerous resources to help clinicians learn to educate other health care professionals, discuss HPV vaccination with parents, and make practice changes to increase HPV vaccine uptake.

• You Are the Key to HPV Prevention. This CDC video presents up-to-date information on HPV infection and disease, the HPV vaccine, and ways to successfully communicate with patients and their parents about HPV vaccination.

• Adolescentvaccination.org. The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases maintains a website is entirely devoted to adolescent vaccination issues. It contains resources for clinicians, and parents.

• Top Strategies for Increasing Vaccine Coverage. This is a report by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

• You Call the Shots. This is an interactive, Web-based immunization training course created by the CDC.

• Suggestions to Improve Your Immunization Services. This is a checklist of suggestions, by the Immunization Action.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

Adolescents remain undervaccinated for several diseases, and clinicians need to lead the charge to change this reality, according to new clinical reports issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases.

Teens are lagging behind the Healthy People 2020 vaccination goals for the Tdap, quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate (menACWY), and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines, lead authors Henry H. Bernstein, DO, and Joseph A. Bocchini Jr., MD, wrote in the Feb. 6 issue of Pediatrics.

“Although HPV vaccination rates are slowly improving, they continue to lag far behind Tdap and menACWY rates for both boys and girls,” the authors wrote. Only 63% of girls and 50% of boys have gotten at least one HPV vaccine dose; just 42% of girls and 28% of boys finished the entire three-dose series in 2015.

A recent study found that parents declined the HPV vaccine 56% of the time. The three most common reasons were the belief that their child had a low risk of acquiring HPV; fear that the risk of adverse events was too great and belief that the vaccine wasn’t well researched and hasn’t been on the market long enough.

But teens also are falling behind with less controversial vaccines, the report noted. Fewer than half of teens got a flu shot in the 2015-2016 season. Rates for the MenACWY and Tdap are better, but not optimal (81% and 86%, respectively).

Barriers to optimal immunization

The clinical report puts clinicians on the first line of responsibility and makes no apologies for that.

“One of the greatest challenges is health care provider recommendation, which often lacks consistency and urgency,” the authors said. “Many health care providers do not universally recommend vaccines to eligible populations and do not offer concomitant vaccination with indicated vaccines during a single patient encounter.”

In fact, they noted, a recent physician survey found that only about 60% of pediatricians and family doctors strongly recommend the HPV vaccine for 11- and 12-year-old girls. Several parent surveys have determined that lack of provider recommendation is a leading reason for undervaccination among adolescents.

A companion clinical report, also authored by Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini, discusses practical ways to confront these barriers (Pediatrics. 2017 Feb 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4187). It opens with a strong call to physicians to lead the charge in increasing immunization rates.

“Up to 65% of parents have reported not receiving a recommendation … for immunizations. The major reason for nonreceipt [of Tdap and menACWY] was lack of a health care provider recommendation,” they said.

Overcoming parental vaccine hesitancy is a thorny struggle, the authors acknowledge. But they offer some helpful suggestions, including:

• Don’t offer immunizations as “optional.” This opens the door to vaccine dismissal. Instead, “strongly endorse all universally recommended vaccines as important for adolescents’ health.”

• Ask open-ended questions to get at the root of parental hesitancy. Give fact-based, medically sound information. Stress that doctors are parent partners in raising healthy children and protecting them from disease.

• Stress the big-picture benefits of vaccines. Telling parents that the HPV vaccine prevents cancer lifelong is a powerful message. “Up-to-date information on current events and disease outbreaks is a tool to bring into the conversation about vaccines as well.”

• Review the vaccine timeline. Do everything possible to ensure parents follow up and complete each series. “Follow-up immunization visits should be scheduled before the family leaves the care setting.”

• Don’t give up when a parent refuses a vaccine. “Although it may be challenging, it’s important that health care providers offer the vaccine at the next most appropriate time. Perseverance is critical for vaccine uptake and immunization rates.”

Dr. Bernstein and Dr. Bocchini also suggest that vaccine uptake could be boosted by a mental re-set of the office visit. “Missed opportunities for adolescent immunizations,” such as sick calls, are a prime example. “The majority of vaccines are administered during well-child visit [sports or camp physicals]. … However, acute care visits or sick visits in the patient-centered medical home are also an opportunity to deliver vaccines or to discuss upcoming vaccines,” they said.

Education and communication are essential to improving vaccine uptake, the report concludes. “Appropriate techniques for approaching adolescent patients and their parents in the office to encourage immunizations are important skills for healthcare providers. The key to increasing immunization rates and decreasing vaccine-preventable disease … is to focus on educating adolescents and strengthening health care providers’ recommendations by using all clinical opportunities to assess immunization status and provide needed vaccinations.”

Neither Dr Bernstein nor Dr. Bocchini had any financial disclosures.

Need help talking about teen vaccines? Check out these resources

The American Academy of Pediatrics offered the following resources designed to help clinicians communicate effectively when talking to patients and parents about vaccines:

• Talking to parents about the HPV vaccine. This website hosted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention includes a link to the latest vaccination recommendations, as well as a tip sheet with HPV vaccine talking points, a fact sheet on the vaccine’s safety data, and a video with four clinical vignettes that model effective communication.

• The HPV Champion Toolkit. This contains numerous resources to help clinicians learn to educate other health care professionals, discuss HPV vaccination with parents, and make practice changes to increase HPV vaccine uptake.

• You Are the Key to HPV Prevention. This CDC video presents up-to-date information on HPV infection and disease, the HPV vaccine, and ways to successfully communicate with patients and their parents about HPV vaccination.

• Adolescentvaccination.org. The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases maintains a website is entirely devoted to adolescent vaccination issues. It contains resources for clinicians, and parents.

• Top Strategies for Increasing Vaccine Coverage. This is a report by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

• You Call the Shots. This is an interactive, Web-based immunization training course created by the CDC.

• Suggestions to Improve Your Immunization Services. This is a checklist of suggestions, by the Immunization Action.

msullivan@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

ACIP releases updated guidance for adult vaccinations

, according to the newly issued 2017 adult Recommended Immunization Schedule released by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Changes are related to concerns regarding low effectiveness of [LAIV] (FluMist, MedImmune) against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in the United States during the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 influenza seasons,” wrote the authors of the report, published in Annals of Internal Medicine and led by David K. Kim, MD, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division in Atlanta.

Another major change involves vaccination of adults with mild or severe egg allergy. The new guidance states that those with a mild egg allergy should receive either inactivated influenza vaccine or recombinant influenza vaccine, while those with severe allergies should be given one of the same vaccinations but only in a health care setting, so a clinician can monitor any signs of reaction and treat the patient accordingly.

Vaccine doses should be administered based on the patient’s age; a patient with “severe” egg allergy is one who exhibits angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent emesis; requires epinephrine; or requires emergency medical care of any kind after consuming egg products.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) schedules have also been noticeably altered, with the CDC now considering all men and women through the ages of 21 and 26 years, respectively, who received a two-dose series of HPV vaccinations before the age of 15 to be adequately protected. Those who took only one of those two doses still need to take another dose, while men and women who have not been vaccinated should received a three-dose series at 0, 1-2, and 6 months.

Hepatitis B recommendations were also updated, with the CDC now advising: “Adults with chronic liver disease, including, but not limited to, hepatitis C virus infection, cirrhosis, fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level greater than twice the upper limit of normal, should receive a HepB series.”

Meningococcal vaccination guidelines also underwent a number of small changes pertaining to adults with anatomical or functional asplenia and human immunodeficiency virus, among other risk factors.

A number of small changes to the schedule chart were implemented to help make the immunization schedule more “clean and streamlined,” according to the CDC.

“Physicians should pay careful attention to the details found in the footnotes,” the CDC said in a statement. “The footnotes clarify who needs what vaccine, when, and at what dose.”

, according to the newly issued 2017 adult Recommended Immunization Schedule released by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Changes are related to concerns regarding low effectiveness of [LAIV] (FluMist, MedImmune) against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in the United States during the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 influenza seasons,” wrote the authors of the report, published in Annals of Internal Medicine and led by David K. Kim, MD, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division in Atlanta.

Another major change involves vaccination of adults with mild or severe egg allergy. The new guidance states that those with a mild egg allergy should receive either inactivated influenza vaccine or recombinant influenza vaccine, while those with severe allergies should be given one of the same vaccinations but only in a health care setting, so a clinician can monitor any signs of reaction and treat the patient accordingly.

Vaccine doses should be administered based on the patient’s age; a patient with “severe” egg allergy is one who exhibits angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent emesis; requires epinephrine; or requires emergency medical care of any kind after consuming egg products.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) schedules have also been noticeably altered, with the CDC now considering all men and women through the ages of 21 and 26 years, respectively, who received a two-dose series of HPV vaccinations before the age of 15 to be adequately protected. Those who took only one of those two doses still need to take another dose, while men and women who have not been vaccinated should received a three-dose series at 0, 1-2, and 6 months.

Hepatitis B recommendations were also updated, with the CDC now advising: “Adults with chronic liver disease, including, but not limited to, hepatitis C virus infection, cirrhosis, fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level greater than twice the upper limit of normal, should receive a HepB series.”

Meningococcal vaccination guidelines also underwent a number of small changes pertaining to adults with anatomical or functional asplenia and human immunodeficiency virus, among other risk factors.

A number of small changes to the schedule chart were implemented to help make the immunization schedule more “clean and streamlined,” according to the CDC.

“Physicians should pay careful attention to the details found in the footnotes,” the CDC said in a statement. “The footnotes clarify who needs what vaccine, when, and at what dose.”

, according to the newly issued 2017 adult Recommended Immunization Schedule released by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).

“Changes are related to concerns regarding low effectiveness of [LAIV] (FluMist, MedImmune) against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 in the United States during the 2013-2014 and 2015-2016 influenza seasons,” wrote the authors of the report, published in Annals of Internal Medicine and led by David K. Kim, MD, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division in Atlanta.

Another major change involves vaccination of adults with mild or severe egg allergy. The new guidance states that those with a mild egg allergy should receive either inactivated influenza vaccine or recombinant influenza vaccine, while those with severe allergies should be given one of the same vaccinations but only in a health care setting, so a clinician can monitor any signs of reaction and treat the patient accordingly.

Vaccine doses should be administered based on the patient’s age; a patient with “severe” egg allergy is one who exhibits angioedema, respiratory distress, lightheadedness, or recurrent emesis; requires epinephrine; or requires emergency medical care of any kind after consuming egg products.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) schedules have also been noticeably altered, with the CDC now considering all men and women through the ages of 21 and 26 years, respectively, who received a two-dose series of HPV vaccinations before the age of 15 to be adequately protected. Those who took only one of those two doses still need to take another dose, while men and women who have not been vaccinated should received a three-dose series at 0, 1-2, and 6 months.

Hepatitis B recommendations were also updated, with the CDC now advising: “Adults with chronic liver disease, including, but not limited to, hepatitis C virus infection, cirrhosis, fatty liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level greater than twice the upper limit of normal, should receive a HepB series.”

Meningococcal vaccination guidelines also underwent a number of small changes pertaining to adults with anatomical or functional asplenia and human immunodeficiency virus, among other risk factors.

A number of small changes to the schedule chart were implemented to help make the immunization schedule more “clean and streamlined,” according to the CDC.

“Physicians should pay careful attention to the details found in the footnotes,” the CDC said in a statement. “The footnotes clarify who needs what vaccine, when, and at what dose.”

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE