User login

The rising cost of the pneumococcal vaccine: What gives?

Every November, like clockwork, she gets the same letter, said Lindsay Irvin, MD, a pediatrician in San Antonio.

It’s from the drug company Pfizer, and it informs her that the price tag for the pneumococcal vaccine Prevnar 13 is going up. Again.

And it makes her angry.

“They’re the only ones who make it,” she said. “It’s like buying gas in a hurricane – or Coke in an airport. They charge what they want to.”

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends Prevnar 13 for all children younger than 2 years – given at 2, 4, 6, and 15 months – as well as for adults aged 65 years and older.

The vaccine’s formulation has remained mostly unchanged since its 2010 federal approval, but its price continues creeping up, increasing by about 5%-6% most years. In just 8 years, its cost has climbed by more than 50%.

It is among the most expensive vaccines Dr. Irvin provides her young patients.

Doctors and clinics purchase the vaccine and then, once they inject patients, they typically recoup the cost through patients’ insurance coverage. In most cases there are no out-of-pocket costs.

But the steady rise in prices for branded drugs contributes indirectly to rises in premiums, deductibles, and government health spending, analysts say.

A full pediatric course of the vaccine typically involves four shots. In 2010, a single shot cost about $109, according to pricing archives kept by the CDC. It currently costs about $170, according to those archives. Next year, Pfizer says, a shot will cost almost $180.

“Pfizer and other drug companies are raising their prices because they can,” said Gerard Anderson, PhD, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies drug pricing. “They have a patent, and they have a CDC recommendation, which is a double whammy – and a strong incentive for price increases.”

The company disagrees – arguing vaccine pricing supports research for new immunizations, along with ongoing efforts to keep products safe and to improve effectiveness. For instance, Prevnar 13’s shelf life was extended from 2 years to 3 years this year. Pricing also doesn’t affect access.

“Thanks to comprehensive health authority guidelines, Prevnar 13 is one of the most widely available public health interventions, supported by broad insurance coverage and innovative federal programs that guarantee access to vulnerable populations,” Pfizer spokeswoman Sally Beatty said in an interview.

But such arguments don’t justify the pattern of “consistent price increases,” suggested Ameet Sarpatwari, PhD, an epidemiologist and lawyer at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug policy.

“Does that explain what’s going on? Probably not,” he said. “The onus should be on them to show us why this is needed.”

Consumers are not likely to feel a pinch from these increases directly. The Affordable Care Act requires that ACIP-recommended vaccines are covered by insurance, with no cost sharing.

There are other implications, though.

Higher vaccine prices make it harder for physicians to stock up, noted Michael Munger, MD, a family physician in Overland Park, Kan., and president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

They have to buy immunizations in advance to provide them for patients. Insurance will eventually reimburse them – typically at cost – but it can take months for that to come through, which is an especially tough proposition for small practices on tight budgets.

“You’ve got to keep track of your inventory, and make sure you don’t have any waste, and are going to get adequate reimbursement,” he said. “The cost of vaccines is definitely something in primary care we worry about, because we’re on thin margins. ... You don’t want to provide a service you lose money on, even if it’s as important as immunization.”

Gardasil, a human papillomavirus vaccine, has also seen its price climbing. And, in a similar response, ob.gyns. are providing it in smaller numbers.

A vaccine like Prevnar 13 is harder to make than older vaccines that are much cheaper, said William Moss, MD, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, who specializes in vaccines and global children’s health. It provides immunization for 13 different variations of pneumococcal infection. That makes it a more effective vaccine, but also one that requires greater investment.

Critics, however, note that those investments were made by another company, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Pfizer bought Wyeth in 2009, along with the rights to the vaccine.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs, and pricing is supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Every November, like clockwork, she gets the same letter, said Lindsay Irvin, MD, a pediatrician in San Antonio.

It’s from the drug company Pfizer, and it informs her that the price tag for the pneumococcal vaccine Prevnar 13 is going up. Again.

And it makes her angry.

“They’re the only ones who make it,” she said. “It’s like buying gas in a hurricane – or Coke in an airport. They charge what they want to.”

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends Prevnar 13 for all children younger than 2 years – given at 2, 4, 6, and 15 months – as well as for adults aged 65 years and older.

The vaccine’s formulation has remained mostly unchanged since its 2010 federal approval, but its price continues creeping up, increasing by about 5%-6% most years. In just 8 years, its cost has climbed by more than 50%.

It is among the most expensive vaccines Dr. Irvin provides her young patients.

Doctors and clinics purchase the vaccine and then, once they inject patients, they typically recoup the cost through patients’ insurance coverage. In most cases there are no out-of-pocket costs.

But the steady rise in prices for branded drugs contributes indirectly to rises in premiums, deductibles, and government health spending, analysts say.

A full pediatric course of the vaccine typically involves four shots. In 2010, a single shot cost about $109, according to pricing archives kept by the CDC. It currently costs about $170, according to those archives. Next year, Pfizer says, a shot will cost almost $180.

“Pfizer and other drug companies are raising their prices because they can,” said Gerard Anderson, PhD, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies drug pricing. “They have a patent, and they have a CDC recommendation, which is a double whammy – and a strong incentive for price increases.”

The company disagrees – arguing vaccine pricing supports research for new immunizations, along with ongoing efforts to keep products safe and to improve effectiveness. For instance, Prevnar 13’s shelf life was extended from 2 years to 3 years this year. Pricing also doesn’t affect access.

“Thanks to comprehensive health authority guidelines, Prevnar 13 is one of the most widely available public health interventions, supported by broad insurance coverage and innovative federal programs that guarantee access to vulnerable populations,” Pfizer spokeswoman Sally Beatty said in an interview.

But such arguments don’t justify the pattern of “consistent price increases,” suggested Ameet Sarpatwari, PhD, an epidemiologist and lawyer at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug policy.

“Does that explain what’s going on? Probably not,” he said. “The onus should be on them to show us why this is needed.”

Consumers are not likely to feel a pinch from these increases directly. The Affordable Care Act requires that ACIP-recommended vaccines are covered by insurance, with no cost sharing.

There are other implications, though.

Higher vaccine prices make it harder for physicians to stock up, noted Michael Munger, MD, a family physician in Overland Park, Kan., and president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

They have to buy immunizations in advance to provide them for patients. Insurance will eventually reimburse them – typically at cost – but it can take months for that to come through, which is an especially tough proposition for small practices on tight budgets.

“You’ve got to keep track of your inventory, and make sure you don’t have any waste, and are going to get adequate reimbursement,” he said. “The cost of vaccines is definitely something in primary care we worry about, because we’re on thin margins. ... You don’t want to provide a service you lose money on, even if it’s as important as immunization.”

Gardasil, a human papillomavirus vaccine, has also seen its price climbing. And, in a similar response, ob.gyns. are providing it in smaller numbers.

A vaccine like Prevnar 13 is harder to make than older vaccines that are much cheaper, said William Moss, MD, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, who specializes in vaccines and global children’s health. It provides immunization for 13 different variations of pneumococcal infection. That makes it a more effective vaccine, but also one that requires greater investment.

Critics, however, note that those investments were made by another company, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Pfizer bought Wyeth in 2009, along with the rights to the vaccine.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs, and pricing is supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Every November, like clockwork, she gets the same letter, said Lindsay Irvin, MD, a pediatrician in San Antonio.

It’s from the drug company Pfizer, and it informs her that the price tag for the pneumococcal vaccine Prevnar 13 is going up. Again.

And it makes her angry.

“They’re the only ones who make it,” she said. “It’s like buying gas in a hurricane – or Coke in an airport. They charge what they want to.”

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends Prevnar 13 for all children younger than 2 years – given at 2, 4, 6, and 15 months – as well as for adults aged 65 years and older.

The vaccine’s formulation has remained mostly unchanged since its 2010 federal approval, but its price continues creeping up, increasing by about 5%-6% most years. In just 8 years, its cost has climbed by more than 50%.

It is among the most expensive vaccines Dr. Irvin provides her young patients.

Doctors and clinics purchase the vaccine and then, once they inject patients, they typically recoup the cost through patients’ insurance coverage. In most cases there are no out-of-pocket costs.

But the steady rise in prices for branded drugs contributes indirectly to rises in premiums, deductibles, and government health spending, analysts say.

A full pediatric course of the vaccine typically involves four shots. In 2010, a single shot cost about $109, according to pricing archives kept by the CDC. It currently costs about $170, according to those archives. Next year, Pfizer says, a shot will cost almost $180.

“Pfizer and other drug companies are raising their prices because they can,” said Gerard Anderson, PhD, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University who studies drug pricing. “They have a patent, and they have a CDC recommendation, which is a double whammy – and a strong incentive for price increases.”

The company disagrees – arguing vaccine pricing supports research for new immunizations, along with ongoing efforts to keep products safe and to improve effectiveness. For instance, Prevnar 13’s shelf life was extended from 2 years to 3 years this year. Pricing also doesn’t affect access.

“Thanks to comprehensive health authority guidelines, Prevnar 13 is one of the most widely available public health interventions, supported by broad insurance coverage and innovative federal programs that guarantee access to vulnerable populations,” Pfizer spokeswoman Sally Beatty said in an interview.

But such arguments don’t justify the pattern of “consistent price increases,” suggested Ameet Sarpatwari, PhD, an epidemiologist and lawyer at Harvard Medical School, Boston, who studies drug policy.

“Does that explain what’s going on? Probably not,” he said. “The onus should be on them to show us why this is needed.”

Consumers are not likely to feel a pinch from these increases directly. The Affordable Care Act requires that ACIP-recommended vaccines are covered by insurance, with no cost sharing.

There are other implications, though.

Higher vaccine prices make it harder for physicians to stock up, noted Michael Munger, MD, a family physician in Overland Park, Kan., and president of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

They have to buy immunizations in advance to provide them for patients. Insurance will eventually reimburse them – typically at cost – but it can take months for that to come through, which is an especially tough proposition for small practices on tight budgets.

“You’ve got to keep track of your inventory, and make sure you don’t have any waste, and are going to get adequate reimbursement,” he said. “The cost of vaccines is definitely something in primary care we worry about, because we’re on thin margins. ... You don’t want to provide a service you lose money on, even if it’s as important as immunization.”

Gardasil, a human papillomavirus vaccine, has also seen its price climbing. And, in a similar response, ob.gyns. are providing it in smaller numbers.

A vaccine like Prevnar 13 is harder to make than older vaccines that are much cheaper, said William Moss, MD, a professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, who specializes in vaccines and global children’s health. It provides immunization for 13 different variations of pneumococcal infection. That makes it a more effective vaccine, but also one that requires greater investment.

Critics, however, note that those investments were made by another company, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals. Pfizer bought Wyeth in 2009, along with the rights to the vaccine.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs, and pricing is supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Biologics during pregnancy did not affect infant vaccine response

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

The use of biologic therapy during pregnancy did not lower antibody titers among infants vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae B (HiB) or tetanus toxin, according to the results of a study of 179 mothers reported in the January issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.041).

Additionally, there was no link between median infliximab concentration in uterine cord blood and antibody titers among infants aged 7 months and older, wrote Dawn B. Beaulieu, MD, with her associates. “In a limited cohort of exposed infants given the rotavirus vaccine, there was no association with significant adverse reactions,” they also reported.

Experts now recommend against live vaccinations for infants who may have detectable concentrations of biologics, but it remained unclear whether these infants can mount adequate responses to inactive vaccines. Therefore, the researchers analyzed data from the Pregnancy in IBD and Neonatal Outcomes (PIANO) registry collected between 2007 and 2016 and surveyed women about their infants’ vaccination history. They also quantified antibodies in serum samples from infants aged 7 months and older and analyzed measured concentrations of biologics in cord blood.

Among 179 mothers with IBD, most had inactive (77%) or mild disease activity (18%) during pregnancy, the researchers said. Eleven (6%) mothers were not on immunosuppressives while pregnant, 15 (8%) were on an immunomodulator, and the rest were on biologic monotherapy (65%) or a biologic plus an immunomodulator (21%). A total of 46 infants had available HiB titer data, of whom 38 were potentially exposed to biologics; among 49 infants with available tetanus titers, 41 were potentially exposed. In all, 71% of exposed infants had protective levels of antibodies against HiB, and 80% had protective titers to tetanus toxoid. Proportions among unexposed infants were 50% and 75%, respectively. Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ between groups even after excluding infants whose mothers received certolizumab pegol, which has negligible rates of placental transfer.

A total of 39 infants received live rotavirus vaccine despite having detectable levels of biologics in cord blood at birth. Seven developed mild vaccine reactions consisting of fever (six infants) or diarrhea (one infant). This proportion (18%) resembles that from a large study (N Engl J Med. 2006;354:23-33) of healthy infants who were vaccinated against rotavirus, the researchers noted. “Despite our data suggesting a lack of severe side effects with the rotavirus vaccine in these infants, in the absence of robust evidence, one should continue to avoid live vaccines in infants born to mothers on biologic therapy (excluding certolizumab) during the first year of life or until drug clearance is confirmed,” they suggested. “With the growing availability of tests, one conceivably could test serum drug concentration in infants, and, if undetectable, consider live vaccination at that time, if appropriate for the vaccine, particularly in infants most likely to benefit from such vaccines.”

The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: In utero biologic exposure did not prevent immune response to Haemophilus influenzae B and tetanus vaccines during infancy.

Major finding: Proportions of protective antibody titers did not significantly differ among groups.

Data source: A prospective study of 179 mothers with IBD and their infants.

Disclosures: The Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation provided funding. Dr. Beaulieu disclosed a consulting relationship with AbbVie, and four coinvestigators also reported ties to pharmaceutical companies.

MACRA Monday: Pneumococcal vaccination

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

If you haven’t started reporting quality data for the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), there’s still time to avoid a 4% cut to your Medicare payments.

Under the Pick Your Pace approach being offered this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services allows clinicians to test the system by reporting on one quality measure for one patient through paper-based claims. Be sure to append a Quality Data Code (QDC) to the claim form for care provided up to Dec. 31, 2017, in order to avoid a penalty in payment year 2019.

Consider this measure:

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Measure #111: Pneumococcal Vaccination Status for Older Adults

This measure is aimed at capturing the percentage of patients aged 65 years and older who have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine.

What you need to do: Review the medical record to find out if the patient has ever received a pneumococcal vaccine and if not, administer the vaccine.

Eligible cases include patients who were aged 65 years or older on the date of the encounter and a patient encounter during the performance period. Applicable codes include (CPT or HCPCS): 99201, 99202, 99203, 99204, 99205, 99212, 99213, 99214, 99215, 99341, 99342, 99343, 99344, 99345, 99347, 99348, 99349, 99350, G0402, G0438, G0439.

To get credit under MIPS, be sure to include a QDC that shows that you successfully performed the measure or had a good reason for not doing so. For instance, CPT II 4040F indicates that the pneumococcal vaccine was administered or previously received. Use exclusion code G9707 to indicate that the patient was not eligible because they received hospice services at any time during the measurement period.

CMS has a full list measures available for claims-based reporting at qpp.cms.gov. The American Medical Association has also created a step-by-step guide for reporting on one quality measure.

Certain clinicians are exempt from reporting and do not face a penalty under MIPS:

• Those who enrolled in Medicare for the first time during a performance period.

• Those who have Medicare Part B allowed charges of $30,000 or less.

• Those who have 100 or fewer Medicare Part B patients.

• Those who are significantly participating in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model (APM).

Parents have diverse reasons for refusing HPV vaccine for their child

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, so health care providers have much work to do to educate parents about this anticancer vaccine, said Frances DiAnna Kinder, PhD, RN, CPNP-PC, of the La Salle University, Philadelphia.

Pediatricians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants from numerous private pediatric settings in Philadelphia discussed HPV vaccination during a well-child visit with parents and children who were eligible for the vaccine, which generally starts at age 9 years. After a health visit in which the HPV vaccine was refused, the parent was asked to complete a survey in a private room. Of 72 surveys by 63 mothers, 8 fathers, and 1 grandparent of children who were mostly female and mostly between ages 11-16 years, 58% said the vaccine was too new, and 50% said there was not enough research. However, 63% said they believed in the HPV vaccine’s efficacy, and all reported their child was up to date with other recommended vaccines.

There was an open-ended question for parents to indicate other reasons for refusal; some themes of refusal included fear, anxiety, and misunderstanding the facts of the HPV vaccine; 21 parents whose children were aged 11-13 years said their child was too young to be vaccinated with the HPV vaccine. Three parents said that they had “witnessed severe side effects such as becoming paralyzed” or “acquiring an autoimmune disease after the vaccine was administered” to either a family member or friend’s child, Dr. Kinder noted. One parent said, “this vaccine was a money maker for the pharmaceutical companies” and there was “too much controversy for her to be comfortable giving this to her child.”

Read more at (J Pediatr Health Care. 2017. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.09.003).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRIC HEALTH CARE

A program to increase flu vaccine compliance

. It won’t hurt your bottom line either and actually will help it. A flu shot program potentially can be run by a licensed practical nurse, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or pediatric nurse practitioner, depending on your state’s law regarding vaccine administration by other than a physician, thus freeing up the physician to see well-child and sick-call patients.

It’s easy to set up a flu shot program and run it. Start preparing in June, preceding the upcoming flu season. Designate several Saturdays and or Sundays in September, October, November, December, and January as flu shot Saturdays and/or Sundays. And if Columbus day falls on a weekday, consider adding Columbus Day to your program dates as the kids often are off from school that day (check the local school calendar).

Next, prepare a postcard to be mailed to all patients on the lists your EMR produced for you. Keep the postcard simple. Announce the program, and state the dates the flu shot program is running. Ask parents to call to make an appointment for a flu vaccine only by appointment “with the program.” In addition to mailing a postcard, announce the flu shot program by sending out automated telephone calls and emails to all three lists the EMR has produced for you. The postcard mailing is your first contact, essentially announcing the program with dates and times. An automated phone call may be used to announce a specific date for which you are “now booking.” A good option when using automated phone calls is to allow the caller to press “zero” to be connected to the office to schedule a “flu shot only” appointment! Finally, emails announcing the dates of the program simply will reinforce information about the program.

Mr. Berman has been providing practice management services to physicians and other medical providers since 1983. He is the CEO of a pediatrics practice with locations in Staten Island and Brooklyn, N.Y. He holds a faculty appointment at State University of New York, Brooklyn, as a lecturer for the department of family medicine’s residency training program. He has no disclosures to report. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

. It won’t hurt your bottom line either and actually will help it. A flu shot program potentially can be run by a licensed practical nurse, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or pediatric nurse practitioner, depending on your state’s law regarding vaccine administration by other than a physician, thus freeing up the physician to see well-child and sick-call patients.

It’s easy to set up a flu shot program and run it. Start preparing in June, preceding the upcoming flu season. Designate several Saturdays and or Sundays in September, October, November, December, and January as flu shot Saturdays and/or Sundays. And if Columbus day falls on a weekday, consider adding Columbus Day to your program dates as the kids often are off from school that day (check the local school calendar).

Next, prepare a postcard to be mailed to all patients on the lists your EMR produced for you. Keep the postcard simple. Announce the program, and state the dates the flu shot program is running. Ask parents to call to make an appointment for a flu vaccine only by appointment “with the program.” In addition to mailing a postcard, announce the flu shot program by sending out automated telephone calls and emails to all three lists the EMR has produced for you. The postcard mailing is your first contact, essentially announcing the program with dates and times. An automated phone call may be used to announce a specific date for which you are “now booking.” A good option when using automated phone calls is to allow the caller to press “zero” to be connected to the office to schedule a “flu shot only” appointment! Finally, emails announcing the dates of the program simply will reinforce information about the program.

Mr. Berman has been providing practice management services to physicians and other medical providers since 1983. He is the CEO of a pediatrics practice with locations in Staten Island and Brooklyn, N.Y. He holds a faculty appointment at State University of New York, Brooklyn, as a lecturer for the department of family medicine’s residency training program. He has no disclosures to report. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

. It won’t hurt your bottom line either and actually will help it. A flu shot program potentially can be run by a licensed practical nurse, registered nurse, physician’s assistant, or pediatric nurse practitioner, depending on your state’s law regarding vaccine administration by other than a physician, thus freeing up the physician to see well-child and sick-call patients.

It’s easy to set up a flu shot program and run it. Start preparing in June, preceding the upcoming flu season. Designate several Saturdays and or Sundays in September, October, November, December, and January as flu shot Saturdays and/or Sundays. And if Columbus day falls on a weekday, consider adding Columbus Day to your program dates as the kids often are off from school that day (check the local school calendar).

Next, prepare a postcard to be mailed to all patients on the lists your EMR produced for you. Keep the postcard simple. Announce the program, and state the dates the flu shot program is running. Ask parents to call to make an appointment for a flu vaccine only by appointment “with the program.” In addition to mailing a postcard, announce the flu shot program by sending out automated telephone calls and emails to all three lists the EMR has produced for you. The postcard mailing is your first contact, essentially announcing the program with dates and times. An automated phone call may be used to announce a specific date for which you are “now booking.” A good option when using automated phone calls is to allow the caller to press “zero” to be connected to the office to schedule a “flu shot only” appointment! Finally, emails announcing the dates of the program simply will reinforce information about the program.

Mr. Berman has been providing practice management services to physicians and other medical providers since 1983. He is the CEO of a pediatrics practice with locations in Staten Island and Brooklyn, N.Y. He holds a faculty appointment at State University of New York, Brooklyn, as a lecturer for the department of family medicine’s residency training program. He has no disclosures to report. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Chinese school-based flu vaccination program reduced outbreaks

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

, said Yang Pan, PhD, of the Institute for Infectious Disease and Endemic Disease Control, Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, and associates.

School-based trivalent inactivated influenza vaccination programs generally occurred Oct. 15-Nov. 30 each year since 2007, with greater than 50% vaccination coverage. In an 11-year retrospective study of school outbreaks of influenza in elementary, middle, and high schools in the Beijing area during Sept. 1, 2006-March 31, 2017, there were 286 febrile outbreaks in schools, involving 6,863 children.

During the 11 years, a mismatch between circulating strains and vaccine strains was identified in two influenza seasons, such as “the A(H3N2) 3C.1 (vaccine strain)-A(H3N2) 3C.3a (circulating strains) mismatch in 2014-2015, the B(Yamagata) Clade 2 (vaccine strain)-B(Yamagata) Clade 3 (circulating strain) mismatch in the 2014-2015 influenza season, and B(Yamagata) (vaccine strain)-B(Victoria) (circulating strains) mismatch in 2015-2016,” they reported.

A combination of high flu vaccine coverage because of school-based vaccinations and a good vaccine match reduced influenza outbreaks in schools by 89% (odds ratio, 0.111), Dr. Pan and associates concluded.

“The school-based influenza vaccination program has been in operation for nearly 10 years in the Beijing area, is unique in China, and is one of the few school-based influenza programs in the world,” the researchers explained. “These data can inform and improve vaccination policy locally and nationally.”

Read more in Vaccine (2017 Nov 8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.10.096).

FROM VACCINE

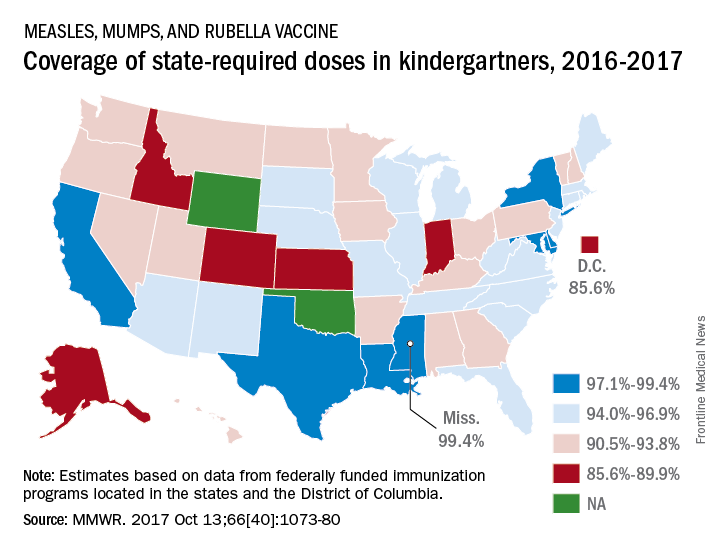

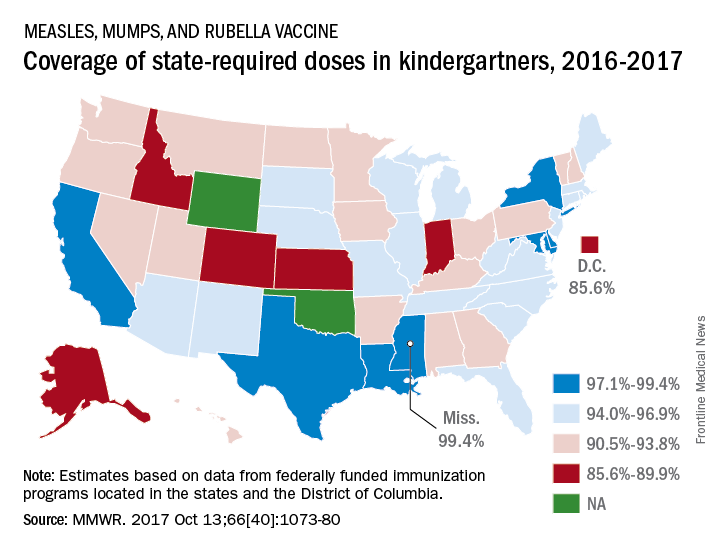

MMR vaccine coverage at 94% in kindergartners

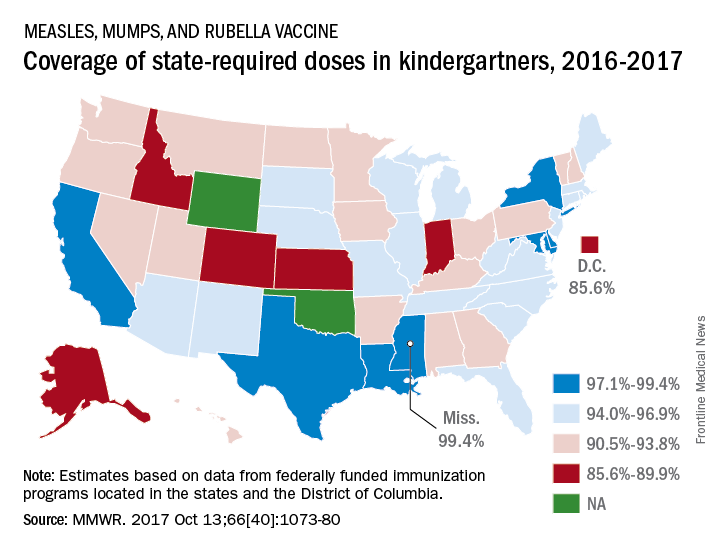

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A look at the map shows that state coverage of required MMR doses varied considerably. Mississippi (99.4%), Maryland (99.3%), Delaware (98.5%), California (97.3%), New York (97.3%), Texas (97.3%), and Louisiana (97.1%) were the furthest above the national median. Occupying the low end of the range were the District of Columbia (85.6%), Colorado (87.3%), Indiana (88.9%), Alaska (89.0%), Kansas (89.5%), and Idaho (89.9%), reported Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta (MMWR 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

The data for the CDC analysis, which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year, were collected by federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C.

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A look at the map shows that state coverage of required MMR doses varied considerably. Mississippi (99.4%), Maryland (99.3%), Delaware (98.5%), California (97.3%), New York (97.3%), Texas (97.3%), and Louisiana (97.1%) were the furthest above the national median. Occupying the low end of the range were the District of Columbia (85.6%), Colorado (87.3%), Indiana (88.9%), Alaska (89.0%), Kansas (89.5%), and Idaho (89.9%), reported Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta (MMWR 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

The data for the CDC analysis, which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year, were collected by federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C.

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A look at the map shows that state coverage of required MMR doses varied considerably. Mississippi (99.4%), Maryland (99.3%), Delaware (98.5%), California (97.3%), New York (97.3%), Texas (97.3%), and Louisiana (97.1%) were the furthest above the national median. Occupying the low end of the range were the District of Columbia (85.6%), Colorado (87.3%), Indiana (88.9%), Alaska (89.0%), Kansas (89.5%), and Idaho (89.9%), reported Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta (MMWR 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

The data for the CDC analysis, which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year, were collected by federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C.

FROM MMWR

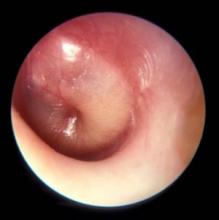

PCVs may reduce AOM severity, although they do not decrease incidence

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

Use of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) may have had a part in reducing the incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of acute otitis media (AOM) in Japanese children, decreasing the rate of myringotomies for AOM, said Atsushi Sasaki, of the Hiroshima (Japan) University, and associates.

To assess whether use of PCV7 and then PCV13 affected AOM incidence, the investigators looked at the incidence of visits to medical institutions (VtMI) due to all-cause AOM in children younger than 15 years in the Japan Medical Data Center Claims Database between January 2005 and December 2015. Data for children aged 10 years to younger than 15 years served as the control. The rate of myringotomies for AOM (MyfA) from January 2007 to December 2015 also was assessed.

Numerous other studies have “concluded that the preventive effect of PCV7 against AOM was very modest,” the researchers said. “In contrast, our study proposes the hypothesis that PCV7 use in 1-year-olds may contribute to the decreased incidence of severe middle ear inflammation of AOM. When evaluating the effectiveness of PCV, measures to evaluate severity may be as important as evaluating disease prevention.”

Read more in Auris Nasus Larynx (2017 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.10.006).

FROM AURIS NASUS LARYNX

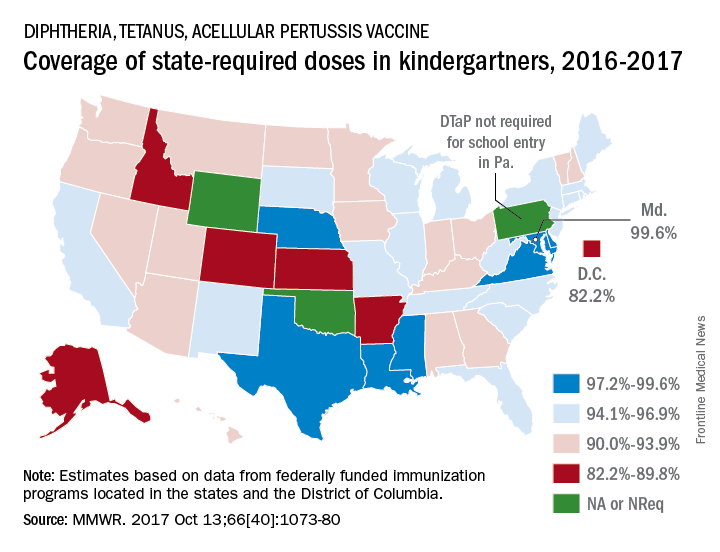

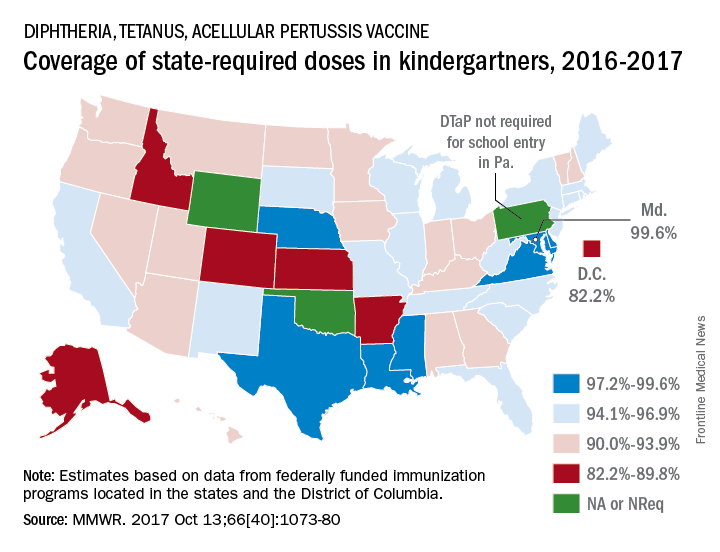

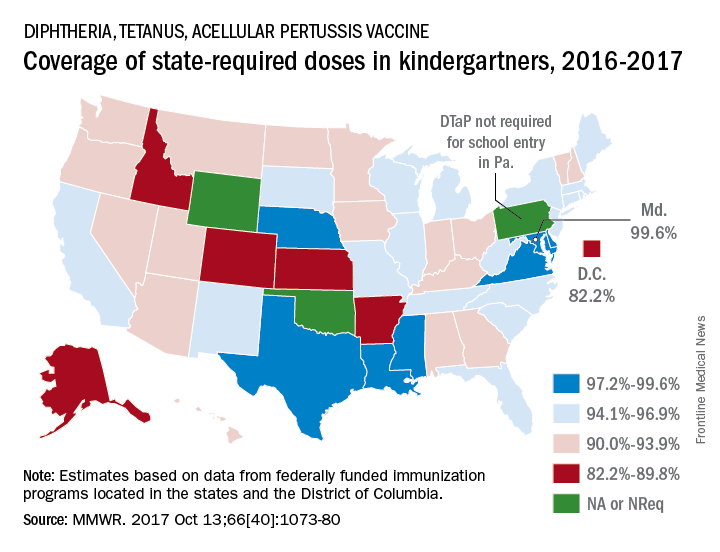

DTaP vaccination rate highest in Maryland

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maryland’s coverage of required DTaP vaccine doses came in at a national high of 99.6% for children entering kindergarten in 2016-2017, while the District of Columbia had the nation’s lowest rate at 82.2%, Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta, reported (MMWR. 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

There is also variation among the states in the number of doses required for kindergarten entry: Most require five, but Illinois, Maryland, Virginia, and Wisconsin require four; Nebraska requires three; and Pennsylvania does not require pertussis vaccine. Oklahoma and Wyoming did not report vaccination coverage “because of widespread problems with the quality of data reported by schools,” they noted.

Nationally, median coverage for state-required doses of the DTaP vaccine was 94.5%, according to data from federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C., which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year.

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maryland’s coverage of required DTaP vaccine doses came in at a national high of 99.6% for children entering kindergarten in 2016-2017, while the District of Columbia had the nation’s lowest rate at 82.2%, Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta, reported (MMWR. 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

There is also variation among the states in the number of doses required for kindergarten entry: Most require five, but Illinois, Maryland, Virginia, and Wisconsin require four; Nebraska requires three; and Pennsylvania does not require pertussis vaccine. Oklahoma and Wyoming did not report vaccination coverage “because of widespread problems with the quality of data reported by schools,” they noted.

Nationally, median coverage for state-required doses of the DTaP vaccine was 94.5%, according to data from federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C., which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year.

, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Maryland’s coverage of required DTaP vaccine doses came in at a national high of 99.6% for children entering kindergarten in 2016-2017, while the District of Columbia had the nation’s lowest rate at 82.2%, Ranee Seither, MPH, of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Disease, and associates at the CDC, Atlanta, reported (MMWR. 2017 Oct 13;66[40]:1073-80).

There is also variation among the states in the number of doses required for kindergarten entry: Most require five, but Illinois, Maryland, Virginia, and Wisconsin require four; Nebraska requires three; and Pennsylvania does not require pertussis vaccine. Oklahoma and Wyoming did not report vaccination coverage “because of widespread problems with the quality of data reported by schools,” they noted.

Nationally, median coverage for state-required doses of the DTaP vaccine was 94.5%, according to data from federally funded immunization programs in the 50 states and D.C., which included 3,973,172 kindergartners for the 2016-2017 school year.

FROM MMWR

Vaccine coverage high among U.S. toddlers in 2016, but gaps remain

, said Holly A. Hill, MD, PhD, and her associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta.

Coverage still was below 90% for vaccines that needed booster doses during the second year of life (four or more doses of DTaP and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] and Haemophilus influenzae type b [Hib] full series) and for other recommended vaccines (hepatitis B [HepB] birth dose, rotavirus, and hepatitis A [HepA]), they reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Coverage was estimated to be 61% for two or more doses of HepA vaccine, 71% of the HepB birth dose, 74% of a completed series of rotavirus vaccine, and 71% of the combined seven-vaccine series (four or more doses of DTaP; three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine; one or more doses of measles-containing vaccine; three or four doses of Hib [depending upon product type of vaccine]; three or more doses of HepB; one or more doses of varicella vaccine; and four or more doses of PCV).

Fewer than 1% of children received no vaccinations.

Coverage of most vaccines in 2016 was lower in non-Hispanic black children, compared with non-Hispanic white children. It also was lower for children living below the federal poverty level, compared with children living at or above the poverty level. For Medicaid children, vaccination coverage was lower by 3%-13% than among children who had private insurance; for children with no insurance, vaccination coverage was lower by 12%-25% than among children with private insurance, the investigators reported.

Uninsured children “are eligible for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which was designed to increase access to vaccination among children through age 18 years who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay,” the researchers said. “Some families might not be aware of the VFC program, be unable to afford fees associated with visits to a vaccine provider, or might need assistance locating a physician who participates in the VFC program. Children living below poverty and up to a certain percentage above the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid … and are entitled to VFC vaccines.”

The investigators cited language barriers, lack of trust in providers, transportation problems, inconvenient office hours, and other provider- and system-level factors as health care–access barriers among publicly insured children.

“These data indicate that the immunization safety net is not reaching all children early in life,” Dr. Hill and her associates said. “Health care providers can increase vaccination coverage using evidence-based strategies such as provider reminders, standing orders to provide vaccination whenever appropriate, and immunization information systems” such as www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination.

Read more in MMWR (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1171-7).

, said Holly A. Hill, MD, PhD, and her associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta.

Coverage still was below 90% for vaccines that needed booster doses during the second year of life (four or more doses of DTaP and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] and Haemophilus influenzae type b [Hib] full series) and for other recommended vaccines (hepatitis B [HepB] birth dose, rotavirus, and hepatitis A [HepA]), they reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Coverage was estimated to be 61% for two or more doses of HepA vaccine, 71% of the HepB birth dose, 74% of a completed series of rotavirus vaccine, and 71% of the combined seven-vaccine series (four or more doses of DTaP; three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine; one or more doses of measles-containing vaccine; three or four doses of Hib [depending upon product type of vaccine]; three or more doses of HepB; one or more doses of varicella vaccine; and four or more doses of PCV).

Fewer than 1% of children received no vaccinations.

Coverage of most vaccines in 2016 was lower in non-Hispanic black children, compared with non-Hispanic white children. It also was lower for children living below the federal poverty level, compared with children living at or above the poverty level. For Medicaid children, vaccination coverage was lower by 3%-13% than among children who had private insurance; for children with no insurance, vaccination coverage was lower by 12%-25% than among children with private insurance, the investigators reported.

Uninsured children “are eligible for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which was designed to increase access to vaccination among children through age 18 years who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay,” the researchers said. “Some families might not be aware of the VFC program, be unable to afford fees associated with visits to a vaccine provider, or might need assistance locating a physician who participates in the VFC program. Children living below poverty and up to a certain percentage above the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid … and are entitled to VFC vaccines.”

The investigators cited language barriers, lack of trust in providers, transportation problems, inconvenient office hours, and other provider- and system-level factors as health care–access barriers among publicly insured children.

“These data indicate that the immunization safety net is not reaching all children early in life,” Dr. Hill and her associates said. “Health care providers can increase vaccination coverage using evidence-based strategies such as provider reminders, standing orders to provide vaccination whenever appropriate, and immunization information systems” such as www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination.

Read more in MMWR (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1171-7).

, said Holly A. Hill, MD, PhD, and her associates at the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Atlanta.

Coverage still was below 90% for vaccines that needed booster doses during the second year of life (four or more doses of DTaP and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine [PCV] and Haemophilus influenzae type b [Hib] full series) and for other recommended vaccines (hepatitis B [HepB] birth dose, rotavirus, and hepatitis A [HepA]), they reported in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Coverage was estimated to be 61% for two or more doses of HepA vaccine, 71% of the HepB birth dose, 74% of a completed series of rotavirus vaccine, and 71% of the combined seven-vaccine series (four or more doses of DTaP; three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine; one or more doses of measles-containing vaccine; three or four doses of Hib [depending upon product type of vaccine]; three or more doses of HepB; one or more doses of varicella vaccine; and four or more doses of PCV).

Fewer than 1% of children received no vaccinations.

Coverage of most vaccines in 2016 was lower in non-Hispanic black children, compared with non-Hispanic white children. It also was lower for children living below the federal poverty level, compared with children living at or above the poverty level. For Medicaid children, vaccination coverage was lower by 3%-13% than among children who had private insurance; for children with no insurance, vaccination coverage was lower by 12%-25% than among children with private insurance, the investigators reported.

Uninsured children “are eligible for the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program, which was designed to increase access to vaccination among children through age 18 years who might not otherwise be vaccinated because of inability to pay,” the researchers said. “Some families might not be aware of the VFC program, be unable to afford fees associated with visits to a vaccine provider, or might need assistance locating a physician who participates in the VFC program. Children living below poverty and up to a certain percentage above the poverty level are eligible for Medicaid … and are entitled to VFC vaccines.”

The investigators cited language barriers, lack of trust in providers, transportation problems, inconvenient office hours, and other provider- and system-level factors as health care–access barriers among publicly insured children.

“These data indicate that the immunization safety net is not reaching all children early in life,” Dr. Hill and her associates said. “Health care providers can increase vaccination coverage using evidence-based strategies such as provider reminders, standing orders to provide vaccination whenever appropriate, and immunization information systems” such as www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination.

Read more in MMWR (2017 Nov 3;66[43]:1171-7).

FROM MMWR