User login

Socioeconomic disparities persist in hysterectomy access

Black women undergoing hysterectomies were significantly more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons than high-volume surgeons, and to experience perioperative complications as a result, based on data from more than 300,000 patients.

“Outcomes for hysterectomy, for both benign and malignant disease, are improved when the procedure is performed at high-volume hospitals and by high-volume surgeons,” Anne Knisely, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Historically, Black patients have been less likely to be referred to high-volume hospitals, the researchers noted. Recent efforts to regionalize surgical procedures to high-volume hospitals aim to reduce disparities and improve care for all patients, but the data on disparities in care within high-volume hospitals are limited, they said.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers identified 300,586 women who underwent hysterectomy in New York state between 2000 and 2014. The researchers divided surgeons at these hospitals into volume groups based on average annual hysterectomy volume.

The women were treated by 5,505 surgeons at 59 hospitals. Overall, Black women comprised significantly more of the patients treated by low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (19.4% vs. 14.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.26), and more women treated by low-volume surgeons had Medicare insurance compared with those treated by high-volume surgeons (20.6% vs. 14.5%; aOR, 1.22).

A majority of the patients (262,005 patients) were treated by a total of 1,377 high-volume surgeons, while 2,105 low-volume surgeons treated 2,900 patients. Abdominal hysterectomies accounted for 57.5% of the procedures, followed by laparoscopic (23.9%), vaginal (13.2%), and robotic assisted (5.3%). Approximately two-thirds (64.4%) of the patients were aged 40-59 years; 63.7% were White, 15.1% were Black, and 8.5% were Hispanic.

The overall complication rate was significantly higher in patients treated by low-volume surgeons, compared with high-volume surgeons (31.0% vs. 10.3%), including intraoperative complications, surgical-site complications, medical complications, and transfusions. The perioperative mortality rate also was significantly higher for patients of low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (2.2% vs. 0.2%).

Low-volume surgeons were more likely to perform urgent or emergent procedures, compared with high-volume surgeons (26.1% vs 6.4%), and to perform abdominal hysterectomy versus minimally invasive hysterectomy compared with high-volume surgeons (77.8% vs. 54.7%), the researchers added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and possible undercoding of outcomes, inclusion only of New York state patients, lack of data on clinical characteristics such as surgical history and complexity, lack of data on surgeon characteristics, and changing practice patterns over time, the researchers noted.

However, “this study demonstrates increased perioperative morbidity and mortality for patients who underwent hysterectomy by low-volume surgeons, in comparison with high-volume surgeons, at high-volume hospitals,” and that Black patients were more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons, they said. “Although centralization of complex surgical care to higher-volume hospitals may have benefit, there are additional surgeon-level factors that must be considered to address disparities in access to high-quality care for patients undergoing hysterectomy.”

Explore range of issues to improve access

“It is always beneficial to review morbidity and mortality statistics,” Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, D.C., said in an interview. “With a heightened awareness of equity and equality, now is a good time to review the data with that focus in mind. Hospital committees review the data on a regular basis, but they may not have looked closely at demographics in the past.

“It was always my understanding that for many procedures, including surgery, volume impacts outcome, so the finding that low-volume surgeons had worse outcomes than high-volume surgeons was not particularly surprising,” said Dr. Bohon. However, the question of how hospitals might address disparities in access to high-volume surgeons “is a difficult question, because there are a variety of issues that may not be caused by disparities,” she added. “It may be that the high-volume surgeons do not take Medicare. It may be that some of the emergent/urgent surgeries come from patients seen in the ED and the high-volume surgeons may not take call or see new patients in the ED. There may be a difference in the preop testing done that may be more extensive with the high-volume surgeons as compared with the low-volume surgeons. It may be that it is easier to get an appointment with a low-volume rather than a high-volume surgeon.

“Additional research is needed to determine whether there is an algorithm that can be created to determine risk for morbidity or mortality based on factors such as the number of years in practice, the number of hysterectomies per year, and the age of the physician,” Dr. Bohon explained. “The patient data could include preexisting risk factors such as weight, preexisting medical conditions, prior surgeries, and current medications, along with demographics. It would be interesting to determine whether low-risk patients have similar outcomes with low- as compared with high-volume surgeons while high-risk patients do not. The demographics could then be evaluated to determine if disparities exist for both low- and high-risk patients.”

The study received no outside funding. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Clovis Oncology, receiving research funding from Merck, and receiving royalties from UpToDate. Lead author Dr. Knisely had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

Black women undergoing hysterectomies were significantly more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons than high-volume surgeons, and to experience perioperative complications as a result, based on data from more than 300,000 patients.

“Outcomes for hysterectomy, for both benign and malignant disease, are improved when the procedure is performed at high-volume hospitals and by high-volume surgeons,” Anne Knisely, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Historically, Black patients have been less likely to be referred to high-volume hospitals, the researchers noted. Recent efforts to regionalize surgical procedures to high-volume hospitals aim to reduce disparities and improve care for all patients, but the data on disparities in care within high-volume hospitals are limited, they said.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers identified 300,586 women who underwent hysterectomy in New York state between 2000 and 2014. The researchers divided surgeons at these hospitals into volume groups based on average annual hysterectomy volume.

The women were treated by 5,505 surgeons at 59 hospitals. Overall, Black women comprised significantly more of the patients treated by low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (19.4% vs. 14.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.26), and more women treated by low-volume surgeons had Medicare insurance compared with those treated by high-volume surgeons (20.6% vs. 14.5%; aOR, 1.22).

A majority of the patients (262,005 patients) were treated by a total of 1,377 high-volume surgeons, while 2,105 low-volume surgeons treated 2,900 patients. Abdominal hysterectomies accounted for 57.5% of the procedures, followed by laparoscopic (23.9%), vaginal (13.2%), and robotic assisted (5.3%). Approximately two-thirds (64.4%) of the patients were aged 40-59 years; 63.7% were White, 15.1% were Black, and 8.5% were Hispanic.

The overall complication rate was significantly higher in patients treated by low-volume surgeons, compared with high-volume surgeons (31.0% vs. 10.3%), including intraoperative complications, surgical-site complications, medical complications, and transfusions. The perioperative mortality rate also was significantly higher for patients of low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (2.2% vs. 0.2%).

Low-volume surgeons were more likely to perform urgent or emergent procedures, compared with high-volume surgeons (26.1% vs 6.4%), and to perform abdominal hysterectomy versus minimally invasive hysterectomy compared with high-volume surgeons (77.8% vs. 54.7%), the researchers added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and possible undercoding of outcomes, inclusion only of New York state patients, lack of data on clinical characteristics such as surgical history and complexity, lack of data on surgeon characteristics, and changing practice patterns over time, the researchers noted.

However, “this study demonstrates increased perioperative morbidity and mortality for patients who underwent hysterectomy by low-volume surgeons, in comparison with high-volume surgeons, at high-volume hospitals,” and that Black patients were more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons, they said. “Although centralization of complex surgical care to higher-volume hospitals may have benefit, there are additional surgeon-level factors that must be considered to address disparities in access to high-quality care for patients undergoing hysterectomy.”

Explore range of issues to improve access

“It is always beneficial to review morbidity and mortality statistics,” Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, D.C., said in an interview. “With a heightened awareness of equity and equality, now is a good time to review the data with that focus in mind. Hospital committees review the data on a regular basis, but they may not have looked closely at demographics in the past.

“It was always my understanding that for many procedures, including surgery, volume impacts outcome, so the finding that low-volume surgeons had worse outcomes than high-volume surgeons was not particularly surprising,” said Dr. Bohon. However, the question of how hospitals might address disparities in access to high-volume surgeons “is a difficult question, because there are a variety of issues that may not be caused by disparities,” she added. “It may be that the high-volume surgeons do not take Medicare. It may be that some of the emergent/urgent surgeries come from patients seen in the ED and the high-volume surgeons may not take call or see new patients in the ED. There may be a difference in the preop testing done that may be more extensive with the high-volume surgeons as compared with the low-volume surgeons. It may be that it is easier to get an appointment with a low-volume rather than a high-volume surgeon.

“Additional research is needed to determine whether there is an algorithm that can be created to determine risk for morbidity or mortality based on factors such as the number of years in practice, the number of hysterectomies per year, and the age of the physician,” Dr. Bohon explained. “The patient data could include preexisting risk factors such as weight, preexisting medical conditions, prior surgeries, and current medications, along with demographics. It would be interesting to determine whether low-risk patients have similar outcomes with low- as compared with high-volume surgeons while high-risk patients do not. The demographics could then be evaluated to determine if disparities exist for both low- and high-risk patients.”

The study received no outside funding. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Clovis Oncology, receiving research funding from Merck, and receiving royalties from UpToDate. Lead author Dr. Knisely had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

Black women undergoing hysterectomies were significantly more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons than high-volume surgeons, and to experience perioperative complications as a result, based on data from more than 300,000 patients.

“Outcomes for hysterectomy, for both benign and malignant disease, are improved when the procedure is performed at high-volume hospitals and by high-volume surgeons,” Anne Knisely, MD, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues wrote.

Historically, Black patients have been less likely to be referred to high-volume hospitals, the researchers noted. Recent efforts to regionalize surgical procedures to high-volume hospitals aim to reduce disparities and improve care for all patients, but the data on disparities in care within high-volume hospitals are limited, they said.

In a study published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, the researchers identified 300,586 women who underwent hysterectomy in New York state between 2000 and 2014. The researchers divided surgeons at these hospitals into volume groups based on average annual hysterectomy volume.

The women were treated by 5,505 surgeons at 59 hospitals. Overall, Black women comprised significantly more of the patients treated by low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (19.4% vs. 14.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.26), and more women treated by low-volume surgeons had Medicare insurance compared with those treated by high-volume surgeons (20.6% vs. 14.5%; aOR, 1.22).

A majority of the patients (262,005 patients) were treated by a total of 1,377 high-volume surgeons, while 2,105 low-volume surgeons treated 2,900 patients. Abdominal hysterectomies accounted for 57.5% of the procedures, followed by laparoscopic (23.9%), vaginal (13.2%), and robotic assisted (5.3%). Approximately two-thirds (64.4%) of the patients were aged 40-59 years; 63.7% were White, 15.1% were Black, and 8.5% were Hispanic.

The overall complication rate was significantly higher in patients treated by low-volume surgeons, compared with high-volume surgeons (31.0% vs. 10.3%), including intraoperative complications, surgical-site complications, medical complications, and transfusions. The perioperative mortality rate also was significantly higher for patients of low-volume surgeons compared with high-volume surgeons (2.2% vs. 0.2%).

Low-volume surgeons were more likely to perform urgent or emergent procedures, compared with high-volume surgeons (26.1% vs 6.4%), and to perform abdominal hysterectomy versus minimally invasive hysterectomy compared with high-volume surgeons (77.8% vs. 54.7%), the researchers added.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including the observational design and possible undercoding of outcomes, inclusion only of New York state patients, lack of data on clinical characteristics such as surgical history and complexity, lack of data on surgeon characteristics, and changing practice patterns over time, the researchers noted.

However, “this study demonstrates increased perioperative morbidity and mortality for patients who underwent hysterectomy by low-volume surgeons, in comparison with high-volume surgeons, at high-volume hospitals,” and that Black patients were more likely to be treated by low-volume surgeons, they said. “Although centralization of complex surgical care to higher-volume hospitals may have benefit, there are additional surgeon-level factors that must be considered to address disparities in access to high-quality care for patients undergoing hysterectomy.”

Explore range of issues to improve access

“It is always beneficial to review morbidity and mortality statistics,” Constance Bohon, MD, a gynecologist in private practice in Washington, D.C., said in an interview. “With a heightened awareness of equity and equality, now is a good time to review the data with that focus in mind. Hospital committees review the data on a regular basis, but they may not have looked closely at demographics in the past.

“It was always my understanding that for many procedures, including surgery, volume impacts outcome, so the finding that low-volume surgeons had worse outcomes than high-volume surgeons was not particularly surprising,” said Dr. Bohon. However, the question of how hospitals might address disparities in access to high-volume surgeons “is a difficult question, because there are a variety of issues that may not be caused by disparities,” she added. “It may be that the high-volume surgeons do not take Medicare. It may be that some of the emergent/urgent surgeries come from patients seen in the ED and the high-volume surgeons may not take call or see new patients in the ED. There may be a difference in the preop testing done that may be more extensive with the high-volume surgeons as compared with the low-volume surgeons. It may be that it is easier to get an appointment with a low-volume rather than a high-volume surgeon.

“Additional research is needed to determine whether there is an algorithm that can be created to determine risk for morbidity or mortality based on factors such as the number of years in practice, the number of hysterectomies per year, and the age of the physician,” Dr. Bohon explained. “The patient data could include preexisting risk factors such as weight, preexisting medical conditions, prior surgeries, and current medications, along with demographics. It would be interesting to determine whether low-risk patients have similar outcomes with low- as compared with high-volume surgeons while high-risk patients do not. The demographics could then be evaluated to determine if disparities exist for both low- and high-risk patients.”

The study received no outside funding. One coauthor disclosed serving as a consultant for Clovis Oncology, receiving research funding from Merck, and receiving royalties from UpToDate. Lead author Dr. Knisely had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Bohon had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Obstetric units place twice as many wrong-patient orders as medical-surgical units

Clinicians in obstetric units place nearly twice as many wrong-patient orders as their medical-surgical counterparts, based on a retrospective look at more than 1.3 million orders.

These findings suggest that obstetric patients are at particular risk for this type of medical error, and that steps are needed to address obstetric clinical culture, work flow, and electronic medical record interfaces, reported lead author Adina R. Kern-Goldberger, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The root of the issue may come from the very nature of obstetrics, and the homogeneity of the patient population, they wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Obstetrics is a unique clinical environment because all patients are admitted with a common diagnosis – pregnancy – and have much more overlap in demographic characteristics than a typical inpatient unit given that they are all females of reproductive age,” the investigators wrote. “The labor and delivery environment also is distinct in the hospital given its dynamic tempo and unpredictable work flow. There also is the added risk of neonates typically being registered in the hospital record under the mother’s name after birth. This generates abundant opportunity for errors in order placement, both between obstetric patients and between postpartum patients and their newborns.”

To determine the relative magnitude of this risk, Dr. Kern-Goldberger and colleagues analyzed EMRs from 45,436 obstetric patients and 12,915 medical-surgical patients at “a large, urban, integrated health system in New York City,” including 1,329,463 order sessions placed between 2016 and 2018.

The primary outcome was near-miss wrong-patient orders, which were identified by the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder measure.

“The measure uses an electronic query to detect retract-and-reorder events, defined as one or more orders placed for patient A, canceled by the same clinician within 10 minutes, and reordered by the same clinician for patient B within the next 10 minutes,” the investigators wrote.In obstetric units, 79.5 wrong-patient orders were placed per 100,000 order sessions, which was 98% higher than the rate of 42.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions in medical-surgical units (odds ratio, 1.98; 95% confidence interval, 1.64-2.39), a disparity that was observed across clinician types and times of day.Advanced practice clinicians in obstetrics placed 47.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, which was significantly lower than that of their colleagues: attending physicians (127.0 per 100,000) and house staff (119.9 per 100,000).

Wrong-patient orders in obstetrics most often involved medication (73.2 per 100,000), particularly nifedipine, antibiotics, tocolytics, and nonoxytocin uterotonics. The “other” category, including but not limited to lab studies and nursing orders, was associated with 51.0 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, while errors in diagnostic imaging orders followed distantly behind, at a rate of 5.7 per 1000,000.

“Although the obstetric clinical environment – particularly labor and delivery – is vibrant and frequently chaotic, it is critical to establish a calm, orderly, and safe culture around order entry,” the investigators wrote. “This, combined with efforts to improve house staff work flow and to optimize EMR interfaces, is likely to help mitigate the threat of wrong order errors to patient care and ultimately improve maternal health and safety.”

According to Catherine D. Cansino, MD, associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis (Calif.) Health, the findings highlight the value of medical informatics while revealing a need to improve EMR interfaces.

“Medical informatics is a growing field and expertise among ob.gyns. is very important,” Dr. Cansino said in an interview. “This study by Kern-Goldberger and colleagues highlights the vulnerability of our EMR systems (and our patients, indirectly) when medical informatics systems are not optimized. The investigators present a study that advocates for greater emphasis on optimizing such systems in obstetrics units, especially in the context of high acuity settings such as obstetrics, compared to medical-surgical units. Appropriately, the study highlights the avoided harm when correcting medical errors for obstetric patients since such errors potentially affect both the delivering patient and the newborn.”

The study was funded by AHRQ. One coauthor disclosed funding from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Georgetown University, the National Institutes of Health – Office of Scientific Review, and the Social Science Research Council. Another reported funding from Roche.

Clinicians in obstetric units place nearly twice as many wrong-patient orders as their medical-surgical counterparts, based on a retrospective look at more than 1.3 million orders.

These findings suggest that obstetric patients are at particular risk for this type of medical error, and that steps are needed to address obstetric clinical culture, work flow, and electronic medical record interfaces, reported lead author Adina R. Kern-Goldberger, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The root of the issue may come from the very nature of obstetrics, and the homogeneity of the patient population, they wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Obstetrics is a unique clinical environment because all patients are admitted with a common diagnosis – pregnancy – and have much more overlap in demographic characteristics than a typical inpatient unit given that they are all females of reproductive age,” the investigators wrote. “The labor and delivery environment also is distinct in the hospital given its dynamic tempo and unpredictable work flow. There also is the added risk of neonates typically being registered in the hospital record under the mother’s name after birth. This generates abundant opportunity for errors in order placement, both between obstetric patients and between postpartum patients and their newborns.”

To determine the relative magnitude of this risk, Dr. Kern-Goldberger and colleagues analyzed EMRs from 45,436 obstetric patients and 12,915 medical-surgical patients at “a large, urban, integrated health system in New York City,” including 1,329,463 order sessions placed between 2016 and 2018.

The primary outcome was near-miss wrong-patient orders, which were identified by the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder measure.

“The measure uses an electronic query to detect retract-and-reorder events, defined as one or more orders placed for patient A, canceled by the same clinician within 10 minutes, and reordered by the same clinician for patient B within the next 10 minutes,” the investigators wrote.In obstetric units, 79.5 wrong-patient orders were placed per 100,000 order sessions, which was 98% higher than the rate of 42.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions in medical-surgical units (odds ratio, 1.98; 95% confidence interval, 1.64-2.39), a disparity that was observed across clinician types and times of day.Advanced practice clinicians in obstetrics placed 47.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, which was significantly lower than that of their colleagues: attending physicians (127.0 per 100,000) and house staff (119.9 per 100,000).

Wrong-patient orders in obstetrics most often involved medication (73.2 per 100,000), particularly nifedipine, antibiotics, tocolytics, and nonoxytocin uterotonics. The “other” category, including but not limited to lab studies and nursing orders, was associated with 51.0 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, while errors in diagnostic imaging orders followed distantly behind, at a rate of 5.7 per 1000,000.

“Although the obstetric clinical environment – particularly labor and delivery – is vibrant and frequently chaotic, it is critical to establish a calm, orderly, and safe culture around order entry,” the investigators wrote. “This, combined with efforts to improve house staff work flow and to optimize EMR interfaces, is likely to help mitigate the threat of wrong order errors to patient care and ultimately improve maternal health and safety.”

According to Catherine D. Cansino, MD, associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis (Calif.) Health, the findings highlight the value of medical informatics while revealing a need to improve EMR interfaces.

“Medical informatics is a growing field and expertise among ob.gyns. is very important,” Dr. Cansino said in an interview. “This study by Kern-Goldberger and colleagues highlights the vulnerability of our EMR systems (and our patients, indirectly) when medical informatics systems are not optimized. The investigators present a study that advocates for greater emphasis on optimizing such systems in obstetrics units, especially in the context of high acuity settings such as obstetrics, compared to medical-surgical units. Appropriately, the study highlights the avoided harm when correcting medical errors for obstetric patients since such errors potentially affect both the delivering patient and the newborn.”

The study was funded by AHRQ. One coauthor disclosed funding from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Georgetown University, the National Institutes of Health – Office of Scientific Review, and the Social Science Research Council. Another reported funding from Roche.

Clinicians in obstetric units place nearly twice as many wrong-patient orders as their medical-surgical counterparts, based on a retrospective look at more than 1.3 million orders.

These findings suggest that obstetric patients are at particular risk for this type of medical error, and that steps are needed to address obstetric clinical culture, work flow, and electronic medical record interfaces, reported lead author Adina R. Kern-Goldberger, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The root of the issue may come from the very nature of obstetrics, and the homogeneity of the patient population, they wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“Obstetrics is a unique clinical environment because all patients are admitted with a common diagnosis – pregnancy – and have much more overlap in demographic characteristics than a typical inpatient unit given that they are all females of reproductive age,” the investigators wrote. “The labor and delivery environment also is distinct in the hospital given its dynamic tempo and unpredictable work flow. There also is the added risk of neonates typically being registered in the hospital record under the mother’s name after birth. This generates abundant opportunity for errors in order placement, both between obstetric patients and between postpartum patients and their newborns.”

To determine the relative magnitude of this risk, Dr. Kern-Goldberger and colleagues analyzed EMRs from 45,436 obstetric patients and 12,915 medical-surgical patients at “a large, urban, integrated health system in New York City,” including 1,329,463 order sessions placed between 2016 and 2018.

The primary outcome was near-miss wrong-patient orders, which were identified by the Wrong-Patient Retract-and-Reorder measure.

“The measure uses an electronic query to detect retract-and-reorder events, defined as one or more orders placed for patient A, canceled by the same clinician within 10 minutes, and reordered by the same clinician for patient B within the next 10 minutes,” the investigators wrote.In obstetric units, 79.5 wrong-patient orders were placed per 100,000 order sessions, which was 98% higher than the rate of 42.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions in medical-surgical units (odds ratio, 1.98; 95% confidence interval, 1.64-2.39), a disparity that was observed across clinician types and times of day.Advanced practice clinicians in obstetrics placed 47.3 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, which was significantly lower than that of their colleagues: attending physicians (127.0 per 100,000) and house staff (119.9 per 100,000).

Wrong-patient orders in obstetrics most often involved medication (73.2 per 100,000), particularly nifedipine, antibiotics, tocolytics, and nonoxytocin uterotonics. The “other” category, including but not limited to lab studies and nursing orders, was associated with 51.0 wrong-patient orders per 100,000 order sessions, while errors in diagnostic imaging orders followed distantly behind, at a rate of 5.7 per 1000,000.

“Although the obstetric clinical environment – particularly labor and delivery – is vibrant and frequently chaotic, it is critical to establish a calm, orderly, and safe culture around order entry,” the investigators wrote. “This, combined with efforts to improve house staff work flow and to optimize EMR interfaces, is likely to help mitigate the threat of wrong order errors to patient care and ultimately improve maternal health and safety.”

According to Catherine D. Cansino, MD, associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at UC Davis (Calif.) Health, the findings highlight the value of medical informatics while revealing a need to improve EMR interfaces.

“Medical informatics is a growing field and expertise among ob.gyns. is very important,” Dr. Cansino said in an interview. “This study by Kern-Goldberger and colleagues highlights the vulnerability of our EMR systems (and our patients, indirectly) when medical informatics systems are not optimized. The investigators present a study that advocates for greater emphasis on optimizing such systems in obstetrics units, especially in the context of high acuity settings such as obstetrics, compared to medical-surgical units. Appropriately, the study highlights the avoided harm when correcting medical errors for obstetric patients since such errors potentially affect both the delivering patient and the newborn.”

The study was funded by AHRQ. One coauthor disclosed funding from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Georgetown University, the National Institutes of Health – Office of Scientific Review, and the Social Science Research Council. Another reported funding from Roche.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Does optimal iron absorption include vitamin C?

Her blood work shows a hematocrit level of 32, a mean corpuscular volume of 77, a platelet count of 390,000, and a ferritin level of 5.

What would you recommend for iron replacement?

A. FeSO4 325 mg three times a day with vitamin C

B. FeSO4 325 mg daily with vitamin C

C. FeSO4 325 mg every other day

Recommendations and supporting research

I think I would start with choice C, FeSO4 every other day.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent evidence has shown that iron absorption is diminished the more frequently it is given.

Stoffel and colleagues found that fractional iron absorption was higher in iron-deficient women who were given iron every other day, compared with those who received daily iron.2 They also found that the more frequently iron was administered, the higher the hepcidin levels were, and the lower the iron absorption.

Karacok and colleagues studied every other day iron versus daily iron for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia of pregnancy.3 A total of 217 women completed randomization and participated in the study, with all women receiving 100 mg of elemental iron, either daily (111) or every other day (106). There was no significant difference in increase in ferritin levels, or hemoglobin increase between the groups. The daily iron group had more gastrointestinal symptoms (41.4%) than the every other day iron group (15.1%) (P < .0057).

Düzen Oflas and colleagues looked at the same question in nonpregnant women with iron deficiency anemia.4 Study patients either received 80 mg iron sulfate twice a day, 80 mg once a day, or 80 mg every other day. There was no statistically significant difference in hemoglobin improvement between groups, but the group that received twice a day dosing of iron had statistically significantly higher ferritin levels than the daily or every other day iron groups. This improvement in ferritin levels came at a cost, though, as 68% of patients in the twice daily iron group had gastrointestinal symptoms, compared with only 10% in the every other day iron group (P < .01).

Vitamin C is often recommended to be taken with iron to promote absorption. The evidence for this practice is scant, and dates back almost 50 years.5,6

Cook and Reddy found there was no significant difference in mean iron absorption among the three dietary periods studied in 12 patients despite a range of mean daily intakes of dietary vitamin C of 51-247 mg/d.7

Hunt and colleagues studied 25 non pregnant, healthy women with low ferritin levels.8 The women’s meals were supplemented with vitamin C (500 mg, three times a day) for 5 of the 10 weeks, in a double-blind, crossover design. Vitamin C supplementation did not lead to a difference in iron absorption, lab indices of iron deficiency, or the biological half-life of iron.

Li and colleagues looked at the effect of vitamin C supplementation on iron levels in women with iron deficiency anemia.9 A total of 440 women were recruited, with 432 completing the trial. Women were randomized to receive iron supplements plus vitamin C or iron supplements only. Their findings were that oral iron supplements alone were equivalent to oral iron supplements plus vitamin C in improving hemoglobin recovery and iron absorption.

Bottom line

Less frequent administration of iron supplements (every other day) is as effective as more frequent administration, with less GI symptoms. Also, adding vitamin C does not appear to improve absorption of iron supplements.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. 1. Fairbanks VF and Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed.” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001).

2. Stoffel N et al. Lancet Haematology. 2017;4: e524-33.

3. Karakoc G et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021 Apr 18:1-5

4. Düzen Oflas N et al. Intern Med J. 2020 Jul;50(7):854-8

5. Cook JD and Monsen ER. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:235-41.

6. Hallberg L etal. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1986;40: 97-113.

7. Cook JD and Reddy M. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:93-8.

8. Hunt JR et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994 Jun;59(6):1381-5.

9. Li N et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2023644.

Her blood work shows a hematocrit level of 32, a mean corpuscular volume of 77, a platelet count of 390,000, and a ferritin level of 5.

What would you recommend for iron replacement?

A. FeSO4 325 mg three times a day with vitamin C

B. FeSO4 325 mg daily with vitamin C

C. FeSO4 325 mg every other day

Recommendations and supporting research

I think I would start with choice C, FeSO4 every other day.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent evidence has shown that iron absorption is diminished the more frequently it is given.

Stoffel and colleagues found that fractional iron absorption was higher in iron-deficient women who were given iron every other day, compared with those who received daily iron.2 They also found that the more frequently iron was administered, the higher the hepcidin levels were, and the lower the iron absorption.

Karacok and colleagues studied every other day iron versus daily iron for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia of pregnancy.3 A total of 217 women completed randomization and participated in the study, with all women receiving 100 mg of elemental iron, either daily (111) or every other day (106). There was no significant difference in increase in ferritin levels, or hemoglobin increase between the groups. The daily iron group had more gastrointestinal symptoms (41.4%) than the every other day iron group (15.1%) (P < .0057).

Düzen Oflas and colleagues looked at the same question in nonpregnant women with iron deficiency anemia.4 Study patients either received 80 mg iron sulfate twice a day, 80 mg once a day, or 80 mg every other day. There was no statistically significant difference in hemoglobin improvement between groups, but the group that received twice a day dosing of iron had statistically significantly higher ferritin levels than the daily or every other day iron groups. This improvement in ferritin levels came at a cost, though, as 68% of patients in the twice daily iron group had gastrointestinal symptoms, compared with only 10% in the every other day iron group (P < .01).

Vitamin C is often recommended to be taken with iron to promote absorption. The evidence for this practice is scant, and dates back almost 50 years.5,6

Cook and Reddy found there was no significant difference in mean iron absorption among the three dietary periods studied in 12 patients despite a range of mean daily intakes of dietary vitamin C of 51-247 mg/d.7

Hunt and colleagues studied 25 non pregnant, healthy women with low ferritin levels.8 The women’s meals were supplemented with vitamin C (500 mg, three times a day) for 5 of the 10 weeks, in a double-blind, crossover design. Vitamin C supplementation did not lead to a difference in iron absorption, lab indices of iron deficiency, or the biological half-life of iron.

Li and colleagues looked at the effect of vitamin C supplementation on iron levels in women with iron deficiency anemia.9 A total of 440 women were recruited, with 432 completing the trial. Women were randomized to receive iron supplements plus vitamin C or iron supplements only. Their findings were that oral iron supplements alone were equivalent to oral iron supplements plus vitamin C in improving hemoglobin recovery and iron absorption.

Bottom line

Less frequent administration of iron supplements (every other day) is as effective as more frequent administration, with less GI symptoms. Also, adding vitamin C does not appear to improve absorption of iron supplements.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. 1. Fairbanks VF and Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed.” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001).

2. Stoffel N et al. Lancet Haematology. 2017;4: e524-33.

3. Karakoc G et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021 Apr 18:1-5

4. Düzen Oflas N et al. Intern Med J. 2020 Jul;50(7):854-8

5. Cook JD and Monsen ER. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:235-41.

6. Hallberg L etal. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1986;40: 97-113.

7. Cook JD and Reddy M. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:93-8.

8. Hunt JR et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994 Jun;59(6):1381-5.

9. Li N et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2023644.

Her blood work shows a hematocrit level of 32, a mean corpuscular volume of 77, a platelet count of 390,000, and a ferritin level of 5.

What would you recommend for iron replacement?

A. FeSO4 325 mg three times a day with vitamin C

B. FeSO4 325 mg daily with vitamin C

C. FeSO4 325 mg every other day

Recommendations and supporting research

I think I would start with choice C, FeSO4 every other day.

Treatment of iron deficiency with oral iron has traditionally been done by giving 150-200 mg of elemental iron (which is equal to three 325 mg tablets of iron sulfate).1 This dosing regimen has considerable gastrointestinal side effects. Recent evidence has shown that iron absorption is diminished the more frequently it is given.

Stoffel and colleagues found that fractional iron absorption was higher in iron-deficient women who were given iron every other day, compared with those who received daily iron.2 They also found that the more frequently iron was administered, the higher the hepcidin levels were, and the lower the iron absorption.

Karacok and colleagues studied every other day iron versus daily iron for the treatment of iron-deficiency anemia of pregnancy.3 A total of 217 women completed randomization and participated in the study, with all women receiving 100 mg of elemental iron, either daily (111) or every other day (106). There was no significant difference in increase in ferritin levels, or hemoglobin increase between the groups. The daily iron group had more gastrointestinal symptoms (41.4%) than the every other day iron group (15.1%) (P < .0057).

Düzen Oflas and colleagues looked at the same question in nonpregnant women with iron deficiency anemia.4 Study patients either received 80 mg iron sulfate twice a day, 80 mg once a day, or 80 mg every other day. There was no statistically significant difference in hemoglobin improvement between groups, but the group that received twice a day dosing of iron had statistically significantly higher ferritin levels than the daily or every other day iron groups. This improvement in ferritin levels came at a cost, though, as 68% of patients in the twice daily iron group had gastrointestinal symptoms, compared with only 10% in the every other day iron group (P < .01).

Vitamin C is often recommended to be taken with iron to promote absorption. The evidence for this practice is scant, and dates back almost 50 years.5,6

Cook and Reddy found there was no significant difference in mean iron absorption among the three dietary periods studied in 12 patients despite a range of mean daily intakes of dietary vitamin C of 51-247 mg/d.7

Hunt and colleagues studied 25 non pregnant, healthy women with low ferritin levels.8 The women’s meals were supplemented with vitamin C (500 mg, three times a day) for 5 of the 10 weeks, in a double-blind, crossover design. Vitamin C supplementation did not lead to a difference in iron absorption, lab indices of iron deficiency, or the biological half-life of iron.

Li and colleagues looked at the effect of vitamin C supplementation on iron levels in women with iron deficiency anemia.9 A total of 440 women were recruited, with 432 completing the trial. Women were randomized to receive iron supplements plus vitamin C or iron supplements only. Their findings were that oral iron supplements alone were equivalent to oral iron supplements plus vitamin C in improving hemoglobin recovery and iron absorption.

Bottom line

Less frequent administration of iron supplements (every other day) is as effective as more frequent administration, with less GI symptoms. Also, adding vitamin C does not appear to improve absorption of iron supplements.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. He is a member of the editorial advisory board of Internal Medicine News. Dr. Paauw has no conflicts to disclose. Contact him at imnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. 1. Fairbanks VF and Beutler E. Iron deficiency, in “Williams Textbook of Hematology, 6th ed.” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001).

2. Stoffel N et al. Lancet Haematology. 2017;4: e524-33.

3. Karakoc G et al. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021 Apr 18:1-5

4. Düzen Oflas N et al. Intern Med J. 2020 Jul;50(7):854-8

5. Cook JD and Monsen ER. Am J Clin Nutr. 1977;30:235-41.

6. Hallberg L etal. Hum Nutr Appl Nutr. 1986;40: 97-113.

7. Cook JD and Reddy M. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:93-8.

8. Hunt JR et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994 Jun;59(6):1381-5.

9. Li N et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2023644.

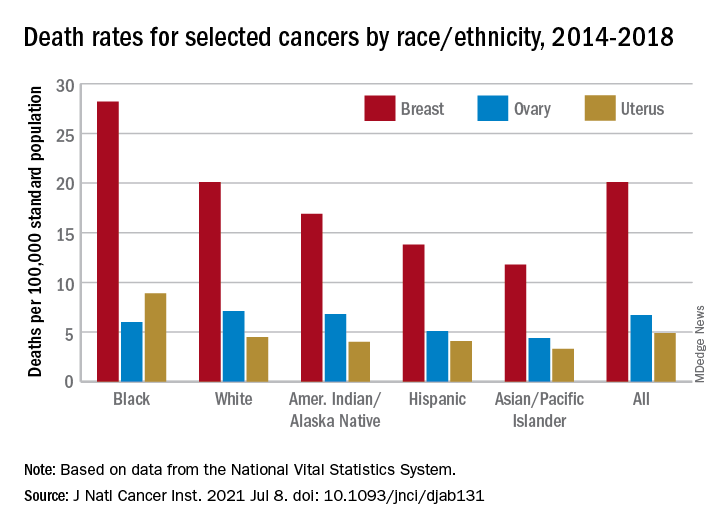

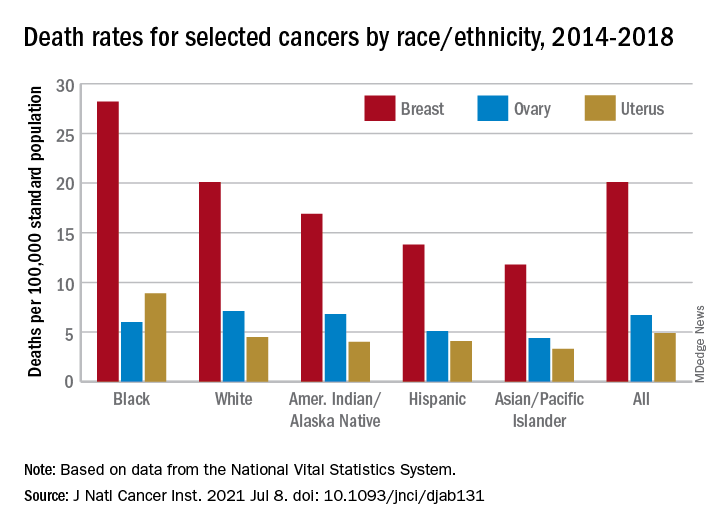

Cancer mortality continues to drop in females as breast cancer reversal looms

Overall cancer mortality in females continues to decrease in the United States, but “previous declining trends in death rates slowed” for breast cancer in recent years, according to an annual report by several national organizations.

The analysis of long-term trends in cancer death rates shows that a decline of 1.4% per year from 2001 to 2016 accelerated to 2.1% per year in 2016-2018, the American Cancer Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries said.

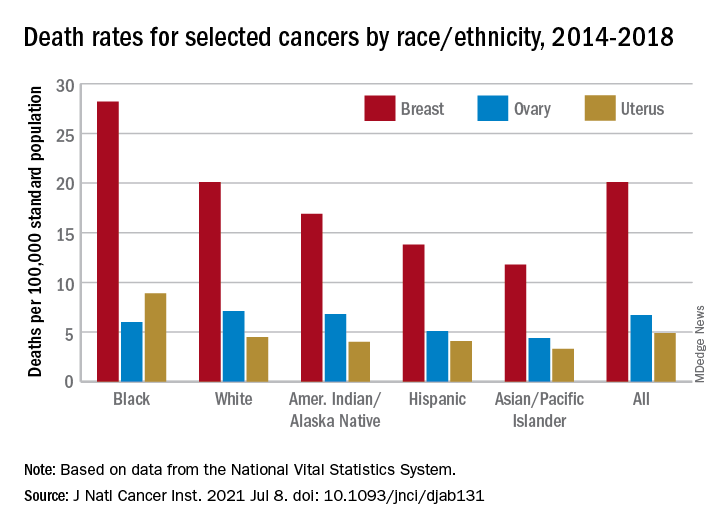

Decreases in overall cancer mortality were seen in females of all races and ethnic groups over the most recent 5-year period included in the report, 2014-2018, varying from –1.6% per year in both non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites to –0.9% for non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and associates said in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Over those 5 years, death rates fell for 14 of the 20 most common cancers in females; increased for liver, uterus, brain, pancreas, and soft tissue including heart; and remained stable for cancers of the oral cavity/pharynx, they reported.

Breast cancer was among those that declined, but the rate of that decline has been slowing. Mortality declined by an average of 2.3% per year in 2003-2007, by 1.6% a year in 2007-2014, and by just 1.0% annually during 2014-2018, based on data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ National Vital Statistics System.

Mortality from all cancers in 2014-2018 was 133.5 deaths per 100,000 standard population, with the racial/ethnic gap ranging from 85.4 per 100,000 (non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander) to 154.9 (non-Hispanic Black), Dr. Islami and associates said.

Melanoma had the largest decline in mortality over that period among the 20 most common cancers in females, falling by an average of 4.4% per year, with lung cancer next at 4.3%. Among those with increased death rates, uterine cancer saw the largest rise at 2.0% a year, the research team said.

The deaths caused by cancer of the uterus were most common in non-Hispanic Black females, 8.9 per 100,000 population, followed by non-Hispanic White (4.5), Hispanic (4.1), non-Hispanic AI/AN (4.0), and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3), they reported.

“Long-term increasing trends in uterine cancer death rates parallel trends in incidence, although death rates are increasing at a somewhat faster rate. Increasing uterine cancer incidence has been attributed to increasing obesity prevalence and decreased use of combined hormone replacement therapy,” Dr. Islami and associates pointed out.

Breast cancer deaths also were most common among Blacks in 2014-2018, occurring at a rate of 28.2 per 100,000, as were deaths from cancer of the cervix (3.4 per 100,000), while ovarian cancers deaths were highest in White females (7.1 per 100,000), the researchers noted.

The continuing racial and ethnic disparity “largely reflects a combination of multiple intertwined factors” of tumor biology, diagnosis, treatment, and systemic discrimination, they wrote, adding that Black persons “are more likely to have a higher exposure to some cancer risk factors and limited access to healthy food, safe places for physical activity, and evidence-based cancer preventive services.”

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Overall cancer mortality in females continues to decrease in the United States, but “previous declining trends in death rates slowed” for breast cancer in recent years, according to an annual report by several national organizations.

The analysis of long-term trends in cancer death rates shows that a decline of 1.4% per year from 2001 to 2016 accelerated to 2.1% per year in 2016-2018, the American Cancer Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries said.

Decreases in overall cancer mortality were seen in females of all races and ethnic groups over the most recent 5-year period included in the report, 2014-2018, varying from –1.6% per year in both non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites to –0.9% for non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and associates said in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Over those 5 years, death rates fell for 14 of the 20 most common cancers in females; increased for liver, uterus, brain, pancreas, and soft tissue including heart; and remained stable for cancers of the oral cavity/pharynx, they reported.

Breast cancer was among those that declined, but the rate of that decline has been slowing. Mortality declined by an average of 2.3% per year in 2003-2007, by 1.6% a year in 2007-2014, and by just 1.0% annually during 2014-2018, based on data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ National Vital Statistics System.

Mortality from all cancers in 2014-2018 was 133.5 deaths per 100,000 standard population, with the racial/ethnic gap ranging from 85.4 per 100,000 (non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander) to 154.9 (non-Hispanic Black), Dr. Islami and associates said.

Melanoma had the largest decline in mortality over that period among the 20 most common cancers in females, falling by an average of 4.4% per year, with lung cancer next at 4.3%. Among those with increased death rates, uterine cancer saw the largest rise at 2.0% a year, the research team said.

The deaths caused by cancer of the uterus were most common in non-Hispanic Black females, 8.9 per 100,000 population, followed by non-Hispanic White (4.5), Hispanic (4.1), non-Hispanic AI/AN (4.0), and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3), they reported.

“Long-term increasing trends in uterine cancer death rates parallel trends in incidence, although death rates are increasing at a somewhat faster rate. Increasing uterine cancer incidence has been attributed to increasing obesity prevalence and decreased use of combined hormone replacement therapy,” Dr. Islami and associates pointed out.

Breast cancer deaths also were most common among Blacks in 2014-2018, occurring at a rate of 28.2 per 100,000, as were deaths from cancer of the cervix (3.4 per 100,000), while ovarian cancers deaths were highest in White females (7.1 per 100,000), the researchers noted.

The continuing racial and ethnic disparity “largely reflects a combination of multiple intertwined factors” of tumor biology, diagnosis, treatment, and systemic discrimination, they wrote, adding that Black persons “are more likely to have a higher exposure to some cancer risk factors and limited access to healthy food, safe places for physical activity, and evidence-based cancer preventive services.”

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Overall cancer mortality in females continues to decrease in the United States, but “previous declining trends in death rates slowed” for breast cancer in recent years, according to an annual report by several national organizations.

The analysis of long-term trends in cancer death rates shows that a decline of 1.4% per year from 2001 to 2016 accelerated to 2.1% per year in 2016-2018, the American Cancer Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Cancer Institute, and the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries said.

Decreases in overall cancer mortality were seen in females of all races and ethnic groups over the most recent 5-year period included in the report, 2014-2018, varying from –1.6% per year in both non-Hispanic Blacks and Whites to –0.9% for non-Hispanic American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), Farhad Islami, MD, PhD, of the American Cancer Society, Atlanta, and associates said in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Over those 5 years, death rates fell for 14 of the 20 most common cancers in females; increased for liver, uterus, brain, pancreas, and soft tissue including heart; and remained stable for cancers of the oral cavity/pharynx, they reported.

Breast cancer was among those that declined, but the rate of that decline has been slowing. Mortality declined by an average of 2.3% per year in 2003-2007, by 1.6% a year in 2007-2014, and by just 1.0% annually during 2014-2018, based on data from the National Center for Health Statistics’ National Vital Statistics System.

Mortality from all cancers in 2014-2018 was 133.5 deaths per 100,000 standard population, with the racial/ethnic gap ranging from 85.4 per 100,000 (non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander) to 154.9 (non-Hispanic Black), Dr. Islami and associates said.

Melanoma had the largest decline in mortality over that period among the 20 most common cancers in females, falling by an average of 4.4% per year, with lung cancer next at 4.3%. Among those with increased death rates, uterine cancer saw the largest rise at 2.0% a year, the research team said.

The deaths caused by cancer of the uterus were most common in non-Hispanic Black females, 8.9 per 100,000 population, followed by non-Hispanic White (4.5), Hispanic (4.1), non-Hispanic AI/AN (4.0), and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander (3.3), they reported.

“Long-term increasing trends in uterine cancer death rates parallel trends in incidence, although death rates are increasing at a somewhat faster rate. Increasing uterine cancer incidence has been attributed to increasing obesity prevalence and decreased use of combined hormone replacement therapy,” Dr. Islami and associates pointed out.

Breast cancer deaths also were most common among Blacks in 2014-2018, occurring at a rate of 28.2 per 100,000, as were deaths from cancer of the cervix (3.4 per 100,000), while ovarian cancers deaths were highest in White females (7.1 per 100,000), the researchers noted.

The continuing racial and ethnic disparity “largely reflects a combination of multiple intertwined factors” of tumor biology, diagnosis, treatment, and systemic discrimination, they wrote, adding that Black persons “are more likely to have a higher exposure to some cancer risk factors and limited access to healthy food, safe places for physical activity, and evidence-based cancer preventive services.”

The report was funded by the four participating groups. Six of the 12 investigators are employees of the American Cancer Society whose salaries are solely paid by the society; the other authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Most U.S. adults age 50+ report good health: Survey

a nonprofit hospice/advanced illness care organization based in Virginia.

Among the respondents, 41% said their health was very good or excellent.

However, the ratings differed largely by race, employment status, and income.

Employment status was also associated with a significant difference in the way people viewed their health at the top tier and bottom tier.

The middle tier (“good” health) was reported similarly (from 33% to 37%) whether a person was employed, retired, or not employed. However, employed respondents were much more likely to report they had “excellent” or “very good” health (51% vs. 44% for retirees and 21% for the not employed).

Conversely, those who were not employed were far more likely to report “fair” or “poor” health (45%) than those who were employed (13%) or retired (20%).

Similarly, respondents with incomes of less than $50,000 were three times more likely to report their health as “fair” or “poor” than were those with incomes of more than $100,000 (36% vs. 12%).

WebMD/CCH surveyed 3,464 U.S. residents ages 50 and older between Aug. 13 and Nov. 9, 2020. WebMD.com readers were randomly invited to take a 10-minute online survey.

Aging at home a priority

The survey also highlighted a strong preference for aging in place, says Steve Cone, chief of communications and philanthropy at CCH.

“More now than ever before, thanks to the COVID experience, baby boomers and their children really believe that’s the holy grail,” he says.

Mr. Cone notes that the quick spread of COVID-19 through some nursing homes early in the pandemic likely has strengthened people’s resolve to live out their lives in their own homes.

The survey indicated that 85% of people aged 50+ who are living in their own home, a family member’s home, or a loved one’s home responded that it is “very important” or “important” to stay in their home as they age.

When asked what services they would need to continue their living situation, the most common responses were housekeeping, home repair services, and transportation (listed as needs by 35% to 45% of respondents). Regarding changes they would have to make to feel safe in their home as they age, installing grab bars and/or safety rails in the bath/shower was the most popular answer (50%).

Use of telemedicine

Respondents were also asked about their acceptance of telemedicine, and 62% said they would be likely or very likely to engage in virtual visits with a doctor it in the future.

However, the likelihood varied by income level. Specifically, respondents with incomes over $100,000 were significantly more likely to say they would use telemedicine in the future than were those with incomes below $50,000 (74% vs. 60%). They were also more likely to already have used telemedicine.

Although respondents generally embraced telemedicine, they are less confident about some types of monitoring, according to Mr. Cone.

Emergency response (64%) was the leading type of remote monitoring respondents ages 50 and older would allow. Only a minority of respondents would allow the other types of monitoring asked about in the survey.

Close to one-quarter of respondents would not allow any type of monitoring.

Fewer than one-third would allow tracking of medication compliance, refrigerator use, sleep habits, or bathroom use.

People see monitoring of some movements as “Orwellian,” Mr. Cone says.

Knowledge of hospice

The survey findings support the need for more widespread use of hospice so people can stay in their homes as they age, Mr. Cone says.

When illness gets severe, “There’s no reason you have to get rushed to the emergency room or wind up in a hospital,” Mr. Cone says.

He notes that hospice and palliative care can come to patients wherever they reside – in their home, an assisted living center, a nursing home, or even a hospital room.

“That doesn’t mean the physician isn’t involved,” he says. “But working as a team, we can keep them in their homes and their lifestyle intact.”

Patients whose doctors attest that they are likely to live a maximum 6 months are eligible for hospice. But most families wait too long to long to start hospice or palliative care for a patient, Mr. Cone says, and may not be aware of what these services typically cover, including meal preparation and pet care.

In the survey, nearly one-third of respondents said they did not know that palliative care is something that “can be given at any stage of a serious illness” or “provides non-medical services (e.g., patient/family communication, help with insurance issues, scheduling appointments, arranging transportation).”

He notes palliative care and hospice are covered by Medicare and Medicaid and also by most private insurance plans or by individual companies providing the service.

However, health care providers may have to overcome a general reluctance to discuss hospice when sharing options for those severely ill.

The survey showed that while 51% of those 50 and older are at least “slightly interested” in learning more about hospice, a nearly equal number say they are “not at all interested” (49%).

Most using hospice are White

More than 90% of those surveyed reported that aspects of hospice care, including “comfort and relief from pain at the end of patients’ lives,” providing a dedicated care team, and an alternative to other care settings, are “very important” or “important.”

However, national hospice use rates are extremely low for minorities and the LGBTQ community, according to Mr. Cone. Among Medicare hospice recipients, 82% were white, 8.2% Black, 6.7% Hispanic, and 1.8% Asian or Pacific Islander, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Those numbers signal a need for outreach to those communities with information on what services are available and how to access them, he says.

Health costs top concern

The survey also asked about level of concern regarding matters including family, health, financials, and end-of-life directives and found adults aged 50 and older expressed the greatest amount of concern for health care costs that are not covered by insurance.

More than half (56%) said they were concerned or very concerned about those costs, which was higher than the percentage concerned about losing a spouse (49%).

Respondents were less concerned (“slightly concerned” or “not at all concerned”) about their children living far away, planning end-of life-directives, and falling or having reduced mobility.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

a nonprofit hospice/advanced illness care organization based in Virginia.

Among the respondents, 41% said their health was very good or excellent.

However, the ratings differed largely by race, employment status, and income.

Employment status was also associated with a significant difference in the way people viewed their health at the top tier and bottom tier.

The middle tier (“good” health) was reported similarly (from 33% to 37%) whether a person was employed, retired, or not employed. However, employed respondents were much more likely to report they had “excellent” or “very good” health (51% vs. 44% for retirees and 21% for the not employed).

Conversely, those who were not employed were far more likely to report “fair” or “poor” health (45%) than those who were employed (13%) or retired (20%).

Similarly, respondents with incomes of less than $50,000 were three times more likely to report their health as “fair” or “poor” than were those with incomes of more than $100,000 (36% vs. 12%).

WebMD/CCH surveyed 3,464 U.S. residents ages 50 and older between Aug. 13 and Nov. 9, 2020. WebMD.com readers were randomly invited to take a 10-minute online survey.

Aging at home a priority

The survey also highlighted a strong preference for aging in place, says Steve Cone, chief of communications and philanthropy at CCH.

“More now than ever before, thanks to the COVID experience, baby boomers and their children really believe that’s the holy grail,” he says.

Mr. Cone notes that the quick spread of COVID-19 through some nursing homes early in the pandemic likely has strengthened people’s resolve to live out their lives in their own homes.

The survey indicated that 85% of people aged 50+ who are living in their own home, a family member’s home, or a loved one’s home responded that it is “very important” or “important” to stay in their home as they age.

When asked what services they would need to continue their living situation, the most common responses were housekeeping, home repair services, and transportation (listed as needs by 35% to 45% of respondents). Regarding changes they would have to make to feel safe in their home as they age, installing grab bars and/or safety rails in the bath/shower was the most popular answer (50%).

Use of telemedicine

Respondents were also asked about their acceptance of telemedicine, and 62% said they would be likely or very likely to engage in virtual visits with a doctor it in the future.

However, the likelihood varied by income level. Specifically, respondents with incomes over $100,000 were significantly more likely to say they would use telemedicine in the future than were those with incomes below $50,000 (74% vs. 60%). They were also more likely to already have used telemedicine.

Although respondents generally embraced telemedicine, they are less confident about some types of monitoring, according to Mr. Cone.

Emergency response (64%) was the leading type of remote monitoring respondents ages 50 and older would allow. Only a minority of respondents would allow the other types of monitoring asked about in the survey.

Close to one-quarter of respondents would not allow any type of monitoring.

Fewer than one-third would allow tracking of medication compliance, refrigerator use, sleep habits, or bathroom use.

People see monitoring of some movements as “Orwellian,” Mr. Cone says.

Knowledge of hospice

The survey findings support the need for more widespread use of hospice so people can stay in their homes as they age, Mr. Cone says.

When illness gets severe, “There’s no reason you have to get rushed to the emergency room or wind up in a hospital,” Mr. Cone says.

He notes that hospice and palliative care can come to patients wherever they reside – in their home, an assisted living center, a nursing home, or even a hospital room.

“That doesn’t mean the physician isn’t involved,” he says. “But working as a team, we can keep them in their homes and their lifestyle intact.”

Patients whose doctors attest that they are likely to live a maximum 6 months are eligible for hospice. But most families wait too long to long to start hospice or palliative care for a patient, Mr. Cone says, and may not be aware of what these services typically cover, including meal preparation and pet care.

In the survey, nearly one-third of respondents said they did not know that palliative care is something that “can be given at any stage of a serious illness” or “provides non-medical services (e.g., patient/family communication, help with insurance issues, scheduling appointments, arranging transportation).”

He notes palliative care and hospice are covered by Medicare and Medicaid and also by most private insurance plans or by individual companies providing the service.

However, health care providers may have to overcome a general reluctance to discuss hospice when sharing options for those severely ill.

The survey showed that while 51% of those 50 and older are at least “slightly interested” in learning more about hospice, a nearly equal number say they are “not at all interested” (49%).

Most using hospice are White

More than 90% of those surveyed reported that aspects of hospice care, including “comfort and relief from pain at the end of patients’ lives,” providing a dedicated care team, and an alternative to other care settings, are “very important” or “important.”

However, national hospice use rates are extremely low for minorities and the LGBTQ community, according to Mr. Cone. Among Medicare hospice recipients, 82% were white, 8.2% Black, 6.7% Hispanic, and 1.8% Asian or Pacific Islander, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Those numbers signal a need for outreach to those communities with information on what services are available and how to access them, he says.

Health costs top concern

The survey also asked about level of concern regarding matters including family, health, financials, and end-of-life directives and found adults aged 50 and older expressed the greatest amount of concern for health care costs that are not covered by insurance.

More than half (56%) said they were concerned or very concerned about those costs, which was higher than the percentage concerned about losing a spouse (49%).

Respondents were less concerned (“slightly concerned” or “not at all concerned”) about their children living far away, planning end-of life-directives, and falling or having reduced mobility.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

a nonprofit hospice/advanced illness care organization based in Virginia.

Among the respondents, 41% said their health was very good or excellent.

However, the ratings differed largely by race, employment status, and income.

Employment status was also associated with a significant difference in the way people viewed their health at the top tier and bottom tier.

The middle tier (“good” health) was reported similarly (from 33% to 37%) whether a person was employed, retired, or not employed. However, employed respondents were much more likely to report they had “excellent” or “very good” health (51% vs. 44% for retirees and 21% for the not employed).

Conversely, those who were not employed were far more likely to report “fair” or “poor” health (45%) than those who were employed (13%) or retired (20%).

Similarly, respondents with incomes of less than $50,000 were three times more likely to report their health as “fair” or “poor” than were those with incomes of more than $100,000 (36% vs. 12%).

WebMD/CCH surveyed 3,464 U.S. residents ages 50 and older between Aug. 13 and Nov. 9, 2020. WebMD.com readers were randomly invited to take a 10-minute online survey.

Aging at home a priority

The survey also highlighted a strong preference for aging in place, says Steve Cone, chief of communications and philanthropy at CCH.

“More now than ever before, thanks to the COVID experience, baby boomers and their children really believe that’s the holy grail,” he says.

Mr. Cone notes that the quick spread of COVID-19 through some nursing homes early in the pandemic likely has strengthened people’s resolve to live out their lives in their own homes.

The survey indicated that 85% of people aged 50+ who are living in their own home, a family member’s home, or a loved one’s home responded that it is “very important” or “important” to stay in their home as they age.

When asked what services they would need to continue their living situation, the most common responses were housekeeping, home repair services, and transportation (listed as needs by 35% to 45% of respondents). Regarding changes they would have to make to feel safe in their home as they age, installing grab bars and/or safety rails in the bath/shower was the most popular answer (50%).

Use of telemedicine

Respondents were also asked about their acceptance of telemedicine, and 62% said they would be likely or very likely to engage in virtual visits with a doctor it in the future.

However, the likelihood varied by income level. Specifically, respondents with incomes over $100,000 were significantly more likely to say they would use telemedicine in the future than were those with incomes below $50,000 (74% vs. 60%). They were also more likely to already have used telemedicine.

Although respondents generally embraced telemedicine, they are less confident about some types of monitoring, according to Mr. Cone.

Emergency response (64%) was the leading type of remote monitoring respondents ages 50 and older would allow. Only a minority of respondents would allow the other types of monitoring asked about in the survey.

Close to one-quarter of respondents would not allow any type of monitoring.

Fewer than one-third would allow tracking of medication compliance, refrigerator use, sleep habits, or bathroom use.

People see monitoring of some movements as “Orwellian,” Mr. Cone says.

Knowledge of hospice

The survey findings support the need for more widespread use of hospice so people can stay in their homes as they age, Mr. Cone says.

When illness gets severe, “There’s no reason you have to get rushed to the emergency room or wind up in a hospital,” Mr. Cone says.

He notes that hospice and palliative care can come to patients wherever they reside – in their home, an assisted living center, a nursing home, or even a hospital room.

“That doesn’t mean the physician isn’t involved,” he says. “But working as a team, we can keep them in their homes and their lifestyle intact.”

Patients whose doctors attest that they are likely to live a maximum 6 months are eligible for hospice. But most families wait too long to long to start hospice or palliative care for a patient, Mr. Cone says, and may not be aware of what these services typically cover, including meal preparation and pet care.

In the survey, nearly one-third of respondents said they did not know that palliative care is something that “can be given at any stage of a serious illness” or “provides non-medical services (e.g., patient/family communication, help with insurance issues, scheduling appointments, arranging transportation).”

He notes palliative care and hospice are covered by Medicare and Medicaid and also by most private insurance plans or by individual companies providing the service.

However, health care providers may have to overcome a general reluctance to discuss hospice when sharing options for those severely ill.

The survey showed that while 51% of those 50 and older are at least “slightly interested” in learning more about hospice, a nearly equal number say they are “not at all interested” (49%).

Most using hospice are White

More than 90% of those surveyed reported that aspects of hospice care, including “comfort and relief from pain at the end of patients’ lives,” providing a dedicated care team, and an alternative to other care settings, are “very important” or “important.”

However, national hospice use rates are extremely low for minorities and the LGBTQ community, according to Mr. Cone. Among Medicare hospice recipients, 82% were white, 8.2% Black, 6.7% Hispanic, and 1.8% Asian or Pacific Islander, according to the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Those numbers signal a need for outreach to those communities with information on what services are available and how to access them, he says.

Health costs top concern

The survey also asked about level of concern regarding matters including family, health, financials, and end-of-life directives and found adults aged 50 and older expressed the greatest amount of concern for health care costs that are not covered by insurance.

More than half (56%) said they were concerned or very concerned about those costs, which was higher than the percentage concerned about losing a spouse (49%).

Respondents were less concerned (“slightly concerned” or “not at all concerned”) about their children living far away, planning end-of life-directives, and falling or having reduced mobility.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

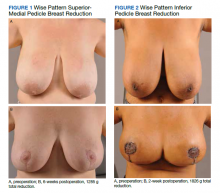

Twenty Years of Breast Reduction Surgery at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Women make up an estimated 10% of the veteran population.1 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) projected that there would be an increase of 18,000 female veterans per year for 10 years based on 2015 data. The number of women veterans enrolled in the VA health care increased from 397,024 to 729,989 (83.9%) between 2005 and 2015.2 This rise in the number of enrolled women veterans also increased the demand for female-specific health care services, such as breast reduction surgery, a reconstructive procedure provided at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center (MRVAMC) federal teaching hospital in Gainesville, Florida.