User login

California bans “Pay for Delay,” promotes black maternal health, PrEP access

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

Congenital syphilis continues to rise at an alarming rate

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

One of the nation’s most preventable diseases is killing newborns in ever-increasing numbers.

Seventy-eight of those babies were stillborn, and 16 died after birth.

In California, cases of congenital syphilis – the term used when a mother passes the infection to her baby during pregnancy – continued a stark 7-year climb, to 332 cases, an 18.1% increase from 2017, according to the federal data. Only Texas, Nevada, Louisiana, and Arizona had congenital syphilis rates higher than California’s. Those five states combined made up nearly two-thirds of total cases, although all but 17 states saw increases in their congenital syphilis rates.

The state-by-state numbers were released as part of a broader report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracking trends in sexually transmitted diseases. Cases of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia combined reached an all-time high in 2018. Cases of the most infectious stage of syphilis rose 14% to more than 35,000 cases; gonorrhea increased 5% to more than 580,000 cases; and chlamydia increased 3% to more than 1.7 million cases.

For veteran public health workers, the upward trend in congenital syphilis numbers is particularly disturbing because the condition is so easy to prevent. Blood tests can identify infection in pregnant women. The treatment is relatively simple and effective. When caught during pregnancy, transmission from mother to baby generally can be stopped.

“When we see a case of congenital syphilis, it is a hallmark of a health system and a health care failure,” said Virginia Bowen, PhD, an epidemiologist with the CDC and an author of the report.

It takes just a few shots of antibiotics to prevent a baby from getting syphilis from its mother. Left untreated, Treponema pallidum, the corkscrew-shaped organism that causes syphilis, can wiggle its way through a mother’s placenta and into a fetus. Once there, it can multiply furiously, invading every part of the body.

The effects on a newborn can be devastating. Philip Cheng, MD, is a neonatologist at St. Joseph’s Medical Center in Stockton, a city in San Joaquin County in California’s Central Valley. Twenty-six babies were infected last year in San Joaquin County, according to state data.

The brain of one of Cheng’s patients didn’t develop properly and the baby died shortly after birth. Other young patients survive but battle blood abnormalities, bone deformities, and organ damage. Congenital syphilis can cause blindness and excruciating pain.

Public health departments across the Central Valley, a largely rural expanse, report similar experiences. Following the release of the CDC report Tuesday, the California Department of Public Health released its county-by-county numbers for 2018. The report showed syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia levels at their highest in 30 years, and attributed 22 stillbirths or neonatal deaths to congenital syphilis.

For the past several years, Fresno County, which had 63 cases of congenital syphilis in 2017, had the highest rate in California. In 2018, Fresno fell to fourth, behind Yuba, Kern, and San Joaquin counties. But the epidemic is far from under control. “I couldn’t even tell you how soon I think we’re going to see a decrease,” said Jena Adams, who oversees HIV and STD programs for Fresno County.

Syphilis was once a prolific and widely feared STD. But by the 1940s, penicillin was found to have a near-perfect cure rate for the disease. By 2000, syphilis rates were so low in the U.S. that the federal government launched a plan to eliminate the disease. Today, that goal is a distant memory.

Health departments once tracked down every person who tested positive for chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis, to make sure they and their partners got treatment. With limited funds and climbing caseloads, many states now devote resources only to tracking syphilis. The caseloads are so high in some California counties that they track only women of childbearing age or just pregnant women.

“A lot of the funding for day-to-day public health work isn’t there,” said Jeffrey Klausner, MD, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles who ran San Francisco’s STD program for more than a decade.

The bulk of STD prevention funding is appropriated by Congress to the CDC, which passes it on to states. That funding has been largely flat since 2003, according to data from the National Coalition of STD Directors, which represents health departments across the country. Take into account inflation and the growing caseloads, and the money is spread thinner. “It takes money, it takes training, it takes resources,” Dr. Klausner said, “and policymakers have just not prioritized that.”

A report this year by Trust for America’s Health, a public health policy research and advocacy group, estimated that 55,000 jobs were cut from local public health departments from 2008 to 2017. “We have our hands tied as much as [states] do,” said Dr. Bowen of the CDC. “We take what we’re given and try to distribute it as fairly as we can.”

San Joaquin County health officials have reorganized the department and applied for grants to increase the number of investigators available while congenital syphilis has spiked, said Hemal Parikh, county coordinator for STD control. But even with new hires and cutting back to tracking only women of childbearing age with syphilis, an investigator can have anywhere from 20 to 30 open cases at a time. In other counties, the caseload can be double that.

In 2018, Jennifer Wagman, PhD, a UCLA professor who studies infectious diseases and gender inequality, was part of a group that received CDC funding to look into what is causing the spike in congenital syphilis in California’s Central Valley.

Dr. Wagman said that, after years of studying health systems in other countries, she was shocked to see how much basic public health infrastructure has crumbled in California. In many parts of the Central Valley, county walk-in clinics that tested for and treated STDs were shuttered in the wake of the recession. That left few places for drop-in care, and investigators with no place to take someone for immediate treatment. Investigators or their patients must make appointments at one of the few providers who carry the right kind of treatment and hope the patients can keep the appointment when the time comes.

In focus groups, women told Dr. Wagman that working hourly jobs, or dealing with chaotic lives involving homelessness, abusive partners, and drug use, can make it all but impossible to stick to the appointments required at private clinics.

Dr. Wagman found that women in these high-risk groups were seeking care, though sometimes late in their pregnancy. They were just more likely to visit an emergency room, urgent care, or even a methadone clinic – places that take drop-ins but don’t necessarily routinely test for or treat syphilis.

“These people already have a million barriers,” said Jenny Malone, the public health nurse for San Joaquin County. “Now there are more.”

The most challenging cases in California are wrapped up with the state’s growing housing crisis and a methamphetamine epidemic with few treatment options. Women who are homeless often have unreliable contact information and are unlikely to have a primary care doctor. That makes them tough to track down to give a positive diagnosis or to follow up on a treatment plan.

Louisiana had the highest rate of congenital syphilis in the country for several years – until 2018. After a 22% drop in its rate, combined with increases in other states, Louisiana now ranks behind Texas and Nevada. That drop is the direct result of $550 million in temporary supplemental funding that the CDC gave the state to combat the epidemic, said Chaquetta Johnson, DNP, deputy director of operations for the state’s STD/HIV/hepatitis program. The money helped bolster the state’s lagging public health infrastructure. It was used to host two conferences for providers in the hardest-hit areas, hire two case managers and a nurse educator, create a program for in-home treatment, and improve data systems to track cases, among other things.

In California, more than 40% of pregnant women with syphilis passed it on to their baby in 2016, the most recent year for which data is available. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) made additional funding available this year, but it’s a “drop in the bucket,” said Sergio Morales of Essential Access Health, a nonprofit that focuses on sexual and reproductive health and is working with Kern County on congenital syphilis. “We are seeing the results of years of inaction and a lack of prioritization of STD prevention, and we’re now paying the price.”

This KHN story first published on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation. Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

[Update: This story was revised at 6:50 p.m. ET on Oct. 8 to reflect news developments.]

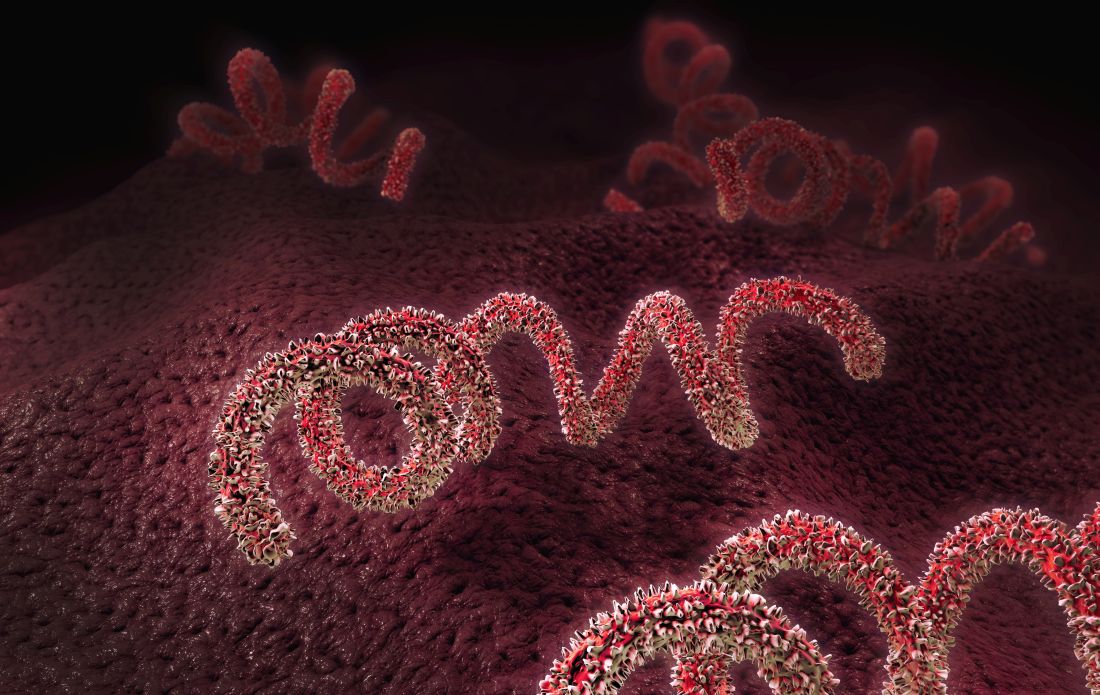

Too few pregnant women receive both influenza and Tdap vaccines

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

according to a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC recommends that all pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks’ gestation. The flu vaccine is recommended for all women at any point in pregnancy if the pregnancy falls within flu season. Women do not need a second flu shot if they received the vaccine before pregnancy in the same influenza season. Both vaccines provide protection to infants after birth.

“Clinicians caring for women who are pregnant have a huge role in helping women understand risks and benefits and the value of vaccines,” Anne Schuchat, MD, principal deputy director of the CDC, Atlanta, said in a telebriefing about the new report. “A lot of women are worried about taking any extra medicine or getting shots during pregnancy, and clinicians can let them know about the large data available showing the safety of the vaccine as well as the effectiveness. We also think it’s important to let people know about the risk of not vaccinating.”

Pregnant women are at higher risk for influenza complications and represent a disproportionate number of flu-related hospitalizations. From the 2010-2011 to 2017-2018 influenza seasons, 24%-34% of influenza hospitalizations each season were pregnant women aged 15-44, yet only 9% of women in this age group are pregnant at any point each year, according to the report.

Similarly, infants under 6 months have the greatest risk of hospitalization from influenza, and half of pertussis hospitalizations and 69% of pertussis deaths occur in infants under 2 months old. But a fetus receives protective maternal antibodies from flu and pertussis vaccines about 2 weeks after the mother is vaccinated.

Influenza hospitalization is 40% lower among pregnant women vaccinated against flu and 72% lower in infants under 6 months who received maternal influenza antibodies during gestation. Similarly, Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy reduces pertussis infection risk by 78% and pertussis hospitalization by 91% in infants under 2 months.

“Infant protection can motivate pregnant women to receive recommended vaccines, and intention to vaccinate is higher among women who perceive more serious consequences of influenza or pertussis disease for their own or their infant’s health,” Megan C. Lindley, MPH, of the CDC’s Immunization Services Division, and colleagues wrote in the MMWR report.

In March-April 2019, Ms. Lindley and associates conducted an Internet survey about flu and Tdap immunizations among women aged 18-49 who had been pregnant at any point since August 1, 2018. A total of 2,626 women completed the survey of 2,762 invitations (95% response rate).

Among 817 women who knew their Tdap status during pregnancy, 55% received the Tdap vaccine. Among 2,097 women who reported a pregnancy between October 2018 and January 2019, 54% received the flu vaccine before or during pregnancy.

But many women received one vaccine without the other: 65% of women surveyed had not received both vaccines during pregnancy. Higher immunization rates occurred among women whose clinicians recommended the vaccines: 66% received a flu shot and 71% received Tdap.

“We’re learning a lot about improved communication between clinicians and patients. One thing we suggest is to begin the conversations early.” Dr Schuchat said. “If you begin talking early in the pregnancy about the things you’ll be looking forward to and provide information, by the time it is flu season or it is that third trimester, they’re prepared to make a good choice.”

Most women surveyed (75%) said their providers did offer a flu or Tdap vaccine in the office or a referral for one. Yet more than 30% of these women did not get the recommended vaccine.

The most common reason for not getting the Tdap during pregnancy, cited by 38% of women who didn’t receive it, was not knowing about the recommendation. Those who did not receive flu vaccination, however, cited concerns about effectiveness (18%) or safety for the baby (16%). A similar proportion of women cited safety concerns for not getting the Tdap (17%).

Sharing information early and engaging respectfully with patients are key to successful provider recommendations, Dr Schuchat said.

“It’s really important for clinicians to begin by listening to women, asking, ‘Can I answer your questions? What are the concerns that you have?’ ” she said. “We find that, when a clinician validates a patient’s concerns and really shows that they’re listening, they can build trust and respect.”

Providers’ sharing their personal experience can help as well, Dr Schuchat added. Clinicians can let patients know if they themselves, or their partner, received the vaccines during pregnancy.

Rates for turning down vaccines were higher for black women: 47% received the flu vaccine after a recommendation, compared with 69% of white women. Among those receiving a Tdap recommendation, 53% of black women accepted it, compared with 77% of white women and 66% of Latina women. The authors noted a past study showing black adults had a higher distrust of flu vaccination, their doctor, and CDC information than white adults.

“Differential effects of provider vaccination offers or referrals might also be explained by less patient-centered provider communication with black patients,” Ms. Lindley and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Lindley MC. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Oct 8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6840e1.

FROM MMWR TELEBRIEFING

Corticosteroid use in pregnancy linked to preterm birth

Pregnant women taking oral corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis may be at increased risk of preterm birth, according to research published online Sept. 30 in Rheumatology.

A study of 528 pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis enrolled in the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies found that those taking a daily dose of 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent – representing a mean cumulative dose of 2,208.6 mg over the first 139 days of pregnancy – had 4.77-fold higher odds of preterm birth, compared with those not taking oral corticosteroids. Women on medium doses – with a mean cumulative dose of 883 mg – had 81% higher odds of preterm birth, while those on low cumulative doses of 264.9 mg showed a nonsignificant 38% increase in preterm birth risk.

Women who did not use oral corticosteroids before day 140 of pregnancy had a 2.2% risk of early preterm birth. Among women with low use of oral corticosteroids, the risk was 3.4%, among those with medium use the risk was 3.3%, but among those with high use the risk was 26.7%.

After day 140 of gestation, there was a nonsignificant 64% increase in the risk for preterm birth with any use of oral corticosteroids, compared with no use. But among women taking 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent per day, the risk was 2.45-fold higher, whereas those taking under 10 mg showed no significant increase in risk.

“Systemic corticosteroid use has been associated with serious infection in pregnant women and serious and nonserious infection in individuals with autoimmune diseases, independent of other immunosuppressive medications, especially for doses of 10 mg of prednisone equivalent per day and greater,” wrote Kristin Palmsten, ScD, a research investigator with HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, Minn., and coauthors.

Given that intrauterine infection is believed to contribute to preterm birth, some have suggested that the immunosuppressive effects of oral corticosteroids could be associated with an increased risk of preterm birth because of subclinical intra-amniotic infection, they wrote.

However, they noted that there was a lack of information on the effect of dose and timing of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy on the risk of preterm birth.

The authors acknowledged that dosage of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy was linked to disease activity, which was itself associated with preterm birth risk. They adjusted for self-assessed rheumatoid arthritis severity at enrollment, which was generally during the first trimester, and found that this did attenuate the association with preterm birth.

“Ideally, we would have measures of disease severity at the time of every medication start, stop, or dose change to account for time-varying confounding later in pregnancy,” they wrote.

The study did not find any effect of biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, either before or after the first 140 days of gestation.

The authors also looked at pregnancy outcomes among women with inflammatory bowel disease and asthma who were taking corticosteroids for those conditions.

While noting that these estimates were “imprecise,” they did see the suggestion of an increase in preterm birth among women taking oral corticosteroids for asthma, especially when used in the first half of pregnancy. There was also a suggestion of increased preterm birth risk associated with high oral corticosteroid use for inflammatory bowel disease, but these estimates were unadjusted, they noted.

“Overall, IBD and asthma exploratory analyses align with the direction of the associations in the RA analysis despite limitations of precision and inability to adjust for IBD severity,” they wrote.

The conclusions to be drawn from the study are limited by its small size, the investigators noted, as well as a lack of information on the type of rheumatoid arthritis and longitudinal disease severity. They added that while the hypothesized mechanism of action linking oral corticosteroid use to preterm birth was subclinical intrauterine infection, they did not have access to placental pathology to confirm this.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies are supported by research grants from a number of pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Palmsten K et al. Rheumatology 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez405.

Pregnant women taking oral corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis may be at increased risk of preterm birth, according to research published online Sept. 30 in Rheumatology.

A study of 528 pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis enrolled in the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies found that those taking a daily dose of 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent – representing a mean cumulative dose of 2,208.6 mg over the first 139 days of pregnancy – had 4.77-fold higher odds of preterm birth, compared with those not taking oral corticosteroids. Women on medium doses – with a mean cumulative dose of 883 mg – had 81% higher odds of preterm birth, while those on low cumulative doses of 264.9 mg showed a nonsignificant 38% increase in preterm birth risk.

Women who did not use oral corticosteroids before day 140 of pregnancy had a 2.2% risk of early preterm birth. Among women with low use of oral corticosteroids, the risk was 3.4%, among those with medium use the risk was 3.3%, but among those with high use the risk was 26.7%.

After day 140 of gestation, there was a nonsignificant 64% increase in the risk for preterm birth with any use of oral corticosteroids, compared with no use. But among women taking 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent per day, the risk was 2.45-fold higher, whereas those taking under 10 mg showed no significant increase in risk.

“Systemic corticosteroid use has been associated with serious infection in pregnant women and serious and nonserious infection in individuals with autoimmune diseases, independent of other immunosuppressive medications, especially for doses of 10 mg of prednisone equivalent per day and greater,” wrote Kristin Palmsten, ScD, a research investigator with HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, Minn., and coauthors.

Given that intrauterine infection is believed to contribute to preterm birth, some have suggested that the immunosuppressive effects of oral corticosteroids could be associated with an increased risk of preterm birth because of subclinical intra-amniotic infection, they wrote.

However, they noted that there was a lack of information on the effect of dose and timing of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy on the risk of preterm birth.

The authors acknowledged that dosage of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy was linked to disease activity, which was itself associated with preterm birth risk. They adjusted for self-assessed rheumatoid arthritis severity at enrollment, which was generally during the first trimester, and found that this did attenuate the association with preterm birth.

“Ideally, we would have measures of disease severity at the time of every medication start, stop, or dose change to account for time-varying confounding later in pregnancy,” they wrote.

The study did not find any effect of biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, either before or after the first 140 days of gestation.

The authors also looked at pregnancy outcomes among women with inflammatory bowel disease and asthma who were taking corticosteroids for those conditions.

While noting that these estimates were “imprecise,” they did see the suggestion of an increase in preterm birth among women taking oral corticosteroids for asthma, especially when used in the first half of pregnancy. There was also a suggestion of increased preterm birth risk associated with high oral corticosteroid use for inflammatory bowel disease, but these estimates were unadjusted, they noted.

“Overall, IBD and asthma exploratory analyses align with the direction of the associations in the RA analysis despite limitations of precision and inability to adjust for IBD severity,” they wrote.

The conclusions to be drawn from the study are limited by its small size, the investigators noted, as well as a lack of information on the type of rheumatoid arthritis and longitudinal disease severity. They added that while the hypothesized mechanism of action linking oral corticosteroid use to preterm birth was subclinical intrauterine infection, they did not have access to placental pathology to confirm this.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies are supported by research grants from a number of pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Palmsten K et al. Rheumatology 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez405.

Pregnant women taking oral corticosteroids for rheumatoid arthritis may be at increased risk of preterm birth, according to research published online Sept. 30 in Rheumatology.

A study of 528 pregnant women with rheumatoid arthritis enrolled in the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies found that those taking a daily dose of 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent – representing a mean cumulative dose of 2,208.6 mg over the first 139 days of pregnancy – had 4.77-fold higher odds of preterm birth, compared with those not taking oral corticosteroids. Women on medium doses – with a mean cumulative dose of 883 mg – had 81% higher odds of preterm birth, while those on low cumulative doses of 264.9 mg showed a nonsignificant 38% increase in preterm birth risk.

Women who did not use oral corticosteroids before day 140 of pregnancy had a 2.2% risk of early preterm birth. Among women with low use of oral corticosteroids, the risk was 3.4%, among those with medium use the risk was 3.3%, but among those with high use the risk was 26.7%.

After day 140 of gestation, there was a nonsignificant 64% increase in the risk for preterm birth with any use of oral corticosteroids, compared with no use. But among women taking 10 mg or more of prednisone equivalent per day, the risk was 2.45-fold higher, whereas those taking under 10 mg showed no significant increase in risk.

“Systemic corticosteroid use has been associated with serious infection in pregnant women and serious and nonserious infection in individuals with autoimmune diseases, independent of other immunosuppressive medications, especially for doses of 10 mg of prednisone equivalent per day and greater,” wrote Kristin Palmsten, ScD, a research investigator with HealthPartners Institute in Minneapolis, Minn., and coauthors.

Given that intrauterine infection is believed to contribute to preterm birth, some have suggested that the immunosuppressive effects of oral corticosteroids could be associated with an increased risk of preterm birth because of subclinical intra-amniotic infection, they wrote.

However, they noted that there was a lack of information on the effect of dose and timing of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy on the risk of preterm birth.

The authors acknowledged that dosage of oral corticosteroids during pregnancy was linked to disease activity, which was itself associated with preterm birth risk. They adjusted for self-assessed rheumatoid arthritis severity at enrollment, which was generally during the first trimester, and found that this did attenuate the association with preterm birth.

“Ideally, we would have measures of disease severity at the time of every medication start, stop, or dose change to account for time-varying confounding later in pregnancy,” they wrote.

The study did not find any effect of biologic or nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, either before or after the first 140 days of gestation.

The authors also looked at pregnancy outcomes among women with inflammatory bowel disease and asthma who were taking corticosteroids for those conditions.

While noting that these estimates were “imprecise,” they did see the suggestion of an increase in preterm birth among women taking oral corticosteroids for asthma, especially when used in the first half of pregnancy. There was also a suggestion of increased preterm birth risk associated with high oral corticosteroid use for inflammatory bowel disease, but these estimates were unadjusted, they noted.

“Overall, IBD and asthma exploratory analyses align with the direction of the associations in the RA analysis despite limitations of precision and inability to adjust for IBD severity,” they wrote.

The conclusions to be drawn from the study are limited by its small size, the investigators noted, as well as a lack of information on the type of rheumatoid arthritis and longitudinal disease severity. They added that while the hypothesized mechanism of action linking oral corticosteroid use to preterm birth was subclinical intrauterine infection, they did not have access to placental pathology to confirm this.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, and the MotherToBaby Pregnancy Studies are supported by research grants from a number of pharmaceutical companies. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Palmsten K et al. Rheumatology 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez405.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

Twin births down among women 30 and older

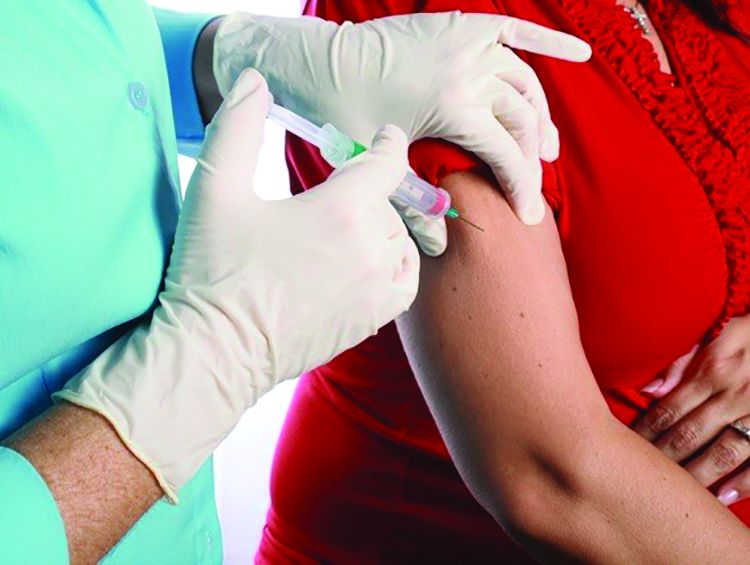

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

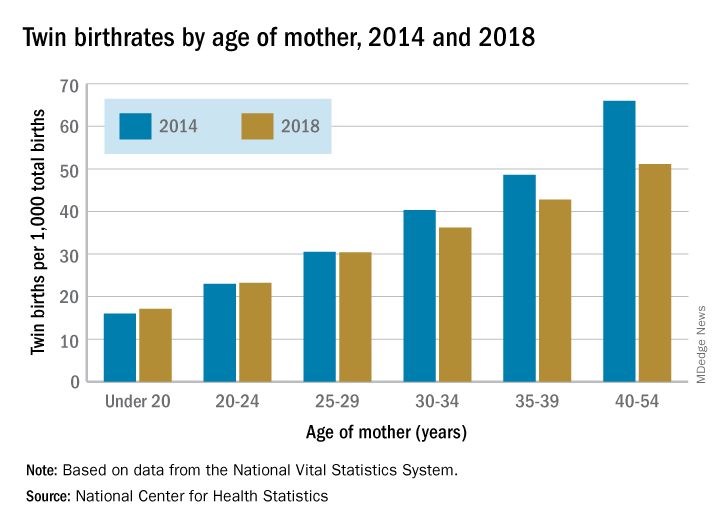

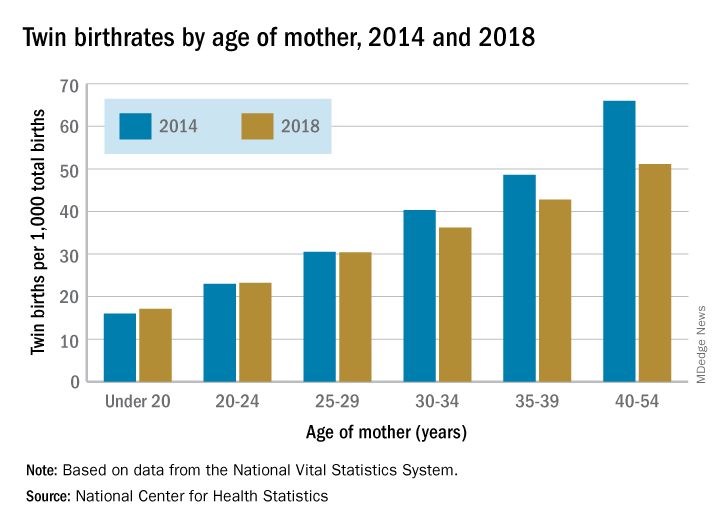

The twin birthrate, which had increased by 79% during 1980-2014, fell by 4% during 2014-2018, but that decline was “not universal across maternal age and race and Hispanic-origin groups,” the NCHS investigators said.

Twin birthrates fell by at least 10% for mothers aged 30 years and older from 2014 to 2018 but held steady for women in their twenties. Over that same period, the twin birthrate fell by a significant 7% among non-Hispanic white women (36.7 to 34.3 per 1,000 total births) but increased just slightly for non-Hispanic black women (40.0 to 40.5 per 1,000) and Hispanic women (24.1 to 24.4), the investigators reported.

For women 30 years and older, the drops in twin births got larger as age increased and were significant for each age group. The rate for women aged 30-34 years fell 10% as it went from 40.3 per 1,000 total births in 2014 to 36.2 per 1,000. The decrease was 12% (from 48.6 per 1,000 to 42.8) for women aged 35-39 and 23% (from 66.0 to 51.1) for those aged 40 years and older, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The rates were basically unchanged for women in their 20s, from 23.0 to 23.2 in 20- to 24-year-olds and 30.5 to 30.4 in 25- to 29-year-olds – but there was a significant increase for the youngest group with rates among those younger than 20 years going from 16.0 to 17.1 per 1,000, the report showed.

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The twin birthrate, which had increased by 79% during 1980-2014, fell by 4% during 2014-2018, but that decline was “not universal across maternal age and race and Hispanic-origin groups,” the NCHS investigators said.

Twin birthrates fell by at least 10% for mothers aged 30 years and older from 2014 to 2018 but held steady for women in their twenties. Over that same period, the twin birthrate fell by a significant 7% among non-Hispanic white women (36.7 to 34.3 per 1,000 total births) but increased just slightly for non-Hispanic black women (40.0 to 40.5 per 1,000) and Hispanic women (24.1 to 24.4), the investigators reported.

For women 30 years and older, the drops in twin births got larger as age increased and were significant for each age group. The rate for women aged 30-34 years fell 10% as it went from 40.3 per 1,000 total births in 2014 to 36.2 per 1,000. The decrease was 12% (from 48.6 per 1,000 to 42.8) for women aged 35-39 and 23% (from 66.0 to 51.1) for those aged 40 years and older, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The rates were basically unchanged for women in their 20s, from 23.0 to 23.2 in 20- to 24-year-olds and 30.5 to 30.4 in 25- to 29-year-olds – but there was a significant increase for the youngest group with rates among those younger than 20 years going from 16.0 to 17.1 per 1,000, the report showed.

according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

The twin birthrate, which had increased by 79% during 1980-2014, fell by 4% during 2014-2018, but that decline was “not universal across maternal age and race and Hispanic-origin groups,” the NCHS investigators said.

Twin birthrates fell by at least 10% for mothers aged 30 years and older from 2014 to 2018 but held steady for women in their twenties. Over that same period, the twin birthrate fell by a significant 7% among non-Hispanic white women (36.7 to 34.3 per 1,000 total births) but increased just slightly for non-Hispanic black women (40.0 to 40.5 per 1,000) and Hispanic women (24.1 to 24.4), the investigators reported.

For women 30 years and older, the drops in twin births got larger as age increased and were significant for each age group. The rate for women aged 30-34 years fell 10% as it went from 40.3 per 1,000 total births in 2014 to 36.2 per 1,000. The decrease was 12% (from 48.6 per 1,000 to 42.8) for women aged 35-39 and 23% (from 66.0 to 51.1) for those aged 40 years and older, they said based on data from the National Vital Statistics System.

The rates were basically unchanged for women in their 20s, from 23.0 to 23.2 in 20- to 24-year-olds and 30.5 to 30.4 in 25- to 29-year-olds – but there was a significant increase for the youngest group with rates among those younger than 20 years going from 16.0 to 17.1 per 1,000, the report showed.

Time to conception after miscarriage: How long to wait?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

To evaluate the longstanding belief that a short IPI after miscarriage is associated with adverse outcomes in subsequent pregnancies, a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 studies (3 randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and 13 retrospective cohort studies) with a total of more than 1 million patients compared IPIs shorter and longer than 6 months (miscarriage was defined as any pregnancy loss before 24 weeks).1 The meta-analysis included 10 of the studies (2 RCTs and 8 cohort studies), with a total of 977,972 women and excluded 6 studies because of insufficient data. The outcomes investigated were recurrent miscarriage, preterm birth, stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, and low birthweight in the pregnancy following miscarriage.

Only 1 study reported the specific gestational age of the index miscarriage at 8.6 ± 2.8 weeks.2 All studies adjusted data for age, and some considered other confounders, such as race, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI).

Women included in the meta-analysis were from Asia, Europe, South America, and the United States and had a history of at least 1 miscarriage.1 A study of 257,908 subjects (Conde-Agudelo) also included women with a history of induced abortion from Latin American countries, where abortion is illegal, and made no distinction between spontaneous and induced abortions in those data sets.3 Women with a history of illegal abortion could be at greater risk of subsequent miscarriage than women who underwent a legally performed abortion.

IPI shorter than 6 months carries fewer risks

Excluding the Conde-Agudelo study, women with an IPI < 6 months, compared with > 6 months, had lower risks of subsequent miscarriage (7 studies, 46,313 women; risk ratio [RR] = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.86) and preterm delivery (7 studies, 60,772 women; RR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.75-0.83); a higher rate of live births (4 studies, 44,586 women; RR = 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.11); and no increase in stillbirths (4 studies, 44,586 women; RR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76-1.02), low birthweight (4 studies, 284,222 women; RR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.48-2.29) or pre-eclampsia (5 studies, 284,899 women; RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.88-1.02) in the subsequent pregnancy.

Including the Conde-Agudelo study, the risk of preterm delivery was the same in women with an IPI < 6 months and > 6 months (8 studies, 318,880 women; RR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.58-1.48).1 Four of the 10 studies evaluated the risk of miscarriage with an IPI < 3 months compared with > 3 months and found either no difference or a lower risk of subsequent miscarriage.2,4-6

IPI shorter than 3 months has lowest risk of all

A 2017 prospective cohort study examined the association between IPI length and risk of recurrent miscarriage in 514 women who had experienced recent miscarriage (defined as spontaneous pregnancy loss before 20 weeks of gestation).7 Average gestational age at the time of initial miscarriage wasn’t reported. Study participants were 30 years of age on average and predominantly white (76.8%); 12.3% were black.

The authors compared IPIs of < 3 months, 3 to 6 months, and > 18 months with IPIs of 6 to 18 months, which correlates with the IPIs recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).8 They adjusted for maternal age, race, parity, BMI, and education. An IPI < 3 months was associated with the lowest risk of subsequent miscarriage (7.3% compared with 22.1%; adjusted hazard ratio = 0.33; 95% CI, 0.16-0.71). Women with IPIs of 3 to 6 months and > 18 months didn’t experience statistically significant differences in subsequent miscarriage rates compared with IPIs of 6 to 18 months.7

Continue to: But a short IPI after second-trimester loss increases risk of miscarriage

But a short IPI after second-trimester loss increases risk of miscarriage

By including all miscarriages, the meta-analysis effectively examined IPI after first-trimester loss because first-trimester loss occurs far more frequently than does second-trimester loss.1 A retrospective cohort study of Australian women, not included in the meta-analysis, assessed 4290 patients with a second-trimester pregnancy loss to specifically examine the association between IPI and risk of recurrent pregnancy loss.9

After a pregnancy loss at 14 to 19 weeks, women with an IPI < 3 months, compared with an IPI of 9 to 12 months, had an increased risk of recurrent pregnancy loss (21.9 vs 11.3%; P < .001). Women with an IPI > 9 to 12 months had rates of pregnancy loss similar to an IPI of 3 to 6 months (RR = 1.24; 95% CI, 0.89-1.7) and 6 to 9 months (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.7-1.5). Women who experienced an initial loss at 20 to 23 weeks, for unclear reasons, showed no evidence that the IPI affected the risk of subsequent loss.

Short IPI may be linked to anxiety in first trimester of next pregnancy

A large cohort study of 20,308 pregnant Chinese women, including 1495 with a previous miscarriage, explored the mental health impact of IPI after miscarriage compared with no miscarriage.10 Investigators used the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale to evaluate anxiety and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale to evaluate depression.

Women with an IPI of < 7 months after miscarriage were more likely to experience anxiety symptoms in the subsequent pregnancy than were women with no previous miscarriage (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.76; 95% CI, 1.4-5.5), whereas women with a history of miscarriage and IPI > 6 months weren’t. Women with IPIs < 7 months and 7 to 12 months, compared with women who had no miscarriage, had an increased risk of depression (AOR = 2.5; 95% CI, 1.4-4.5, and AOR = 2.6; 95% CI, 1.3-5.2, respectively). Women with an IPI > 12 months had no increased risk of depression compared with women with no history of miscarriage.

The odds ratios were adjusted for age, education, BMI, income, and place of residence. The higher rates of depression and anxiety didn’t persist beyond the first trimester of the subsequent pregnancy.

Continue to: RECOMMENDATIONS

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Practice Bulletin on Early Pregnancy Loss states that no quality data exist to support delaying conception after early pregnancy loss (defined as loss of an intrauterine pregnancy in the first trimester) to prevent subsequent pregnancy loss or other pregnancy complications.11

WHO recommends a minimum IPI of at least 6 months after a spontaneous or elective abortion. This recommendation is based on a single multi-center cohort study in Latin America that included women with both spontaneous and induced abortions.8

Editor’s takeaway

High-quality evidence now shows that shorter IPIs after first-trimester miscarriages result in safe subsequent pregnancies. However, some concern remains about second-trimester miscarriages and maternal mental health following a shorter IPI, based on lower-quality evidence.

1. Kangatharan C, Labram S, Bhattacharya S. Interpregnancy interval following miscarriage and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23:221-231.

2. Wong LF, Schliep KC, Silver RM, et al. The effect of a very short interpregnancy interval and pregnancy outcomes following a previous pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:375.e1-375.e11.

3. Conde-Agudelo A, Belizan JM, Breman R, et al. Effect of the interpregnancy interval after an abortion on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(suppl 1):S34-S40.

4. Bentolila Y, Ratzon R, Shoham-Vardi I, et al. Effect of interpregnancy interval on outcomes of pregnancy after recurrent pregnancy loss. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1459-1464.

5. DaVanzo J, Hale L, Rahman M. How long after a miscarriage should women wait before becoming pregnant again? Multivariate analysis of cohort data from Matlab, Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001591.

6. Wyss P, Biedermann K, Huch A. Relevance of the miscarriage-new pregnancy interval. J Perinat Med. 1994;22:235-241.

7. Sundermann AC, Hartmann KE, Jones SH, et al. Interpregnancy interval after pregnancy loss and risk of repeat miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:1312-1318.

8. World Health Organization. Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Department of Making Pregnancy Safer. Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing: Geneva, Switzerland 13-15 June 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2007.

9. Roberts CL, Algert CS, Ford JB, et al. Association between interpregnancy interval and the risk of recurrent loss after a midtrimester loss. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:2834-2840.

10. Gong X, Hao J, Tao F, et al. Pregnancy loss and anxiety and depression during subsequent pregnancies: data from the C-ABC study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;166:30-36.

11. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin no. 150. Early pregnancy loss. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1258-1267.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

To evaluate the longstanding belief that a short IPI after miscarriage is associated with adverse outcomes in subsequent pregnancies, a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 16 studies (3 randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and 13 retrospective cohort studies) with a total of more than 1 million patients compared IPIs shorter and longer than 6 months (miscarriage was defined as any pregnancy loss before 24 weeks).1 The meta-analysis included 10 of the studies (2 RCTs and 8 cohort studies), with a total of 977,972 women and excluded 6 studies because of insufficient data. The outcomes investigated were recurrent miscarriage, preterm birth, stillbirth, pre-eclampsia, and low birthweight in the pregnancy following miscarriage.

Only 1 study reported the specific gestational age of the index miscarriage at 8.6 ± 2.8 weeks.2 All studies adjusted data for age, and some considered other confounders, such as race, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI).

Women included in the meta-analysis were from Asia, Europe, South America, and the United States and had a history of at least 1 miscarriage.1 A study of 257,908 subjects (Conde-Agudelo) also included women with a history of induced abortion from Latin American countries, where abortion is illegal, and made no distinction between spontaneous and induced abortions in those data sets.3 Women with a history of illegal abortion could be at greater risk of subsequent miscarriage than women who underwent a legally performed abortion.

IPI shorter than 6 months carries fewer risks

Excluding the Conde-Agudelo study, women with an IPI < 6 months, compared with > 6 months, had lower risks of subsequent miscarriage (7 studies, 46,313 women; risk ratio [RR] = 0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.86) and preterm delivery (7 studies, 60,772 women; RR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.75-0.83); a higher rate of live births (4 studies, 44,586 women; RR = 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.11); and no increase in stillbirths (4 studies, 44,586 women; RR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76-1.02), low birthweight (4 studies, 284,222 women; RR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.48-2.29) or pre-eclampsia (5 studies, 284,899 women; RR = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.88-1.02) in the subsequent pregnancy.

Including the Conde-Agudelo study, the risk of preterm delivery was the same in women with an IPI < 6 months and > 6 months (8 studies, 318,880 women; RR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.58-1.48).1 Four of the 10 studies evaluated the risk of miscarriage with an IPI < 3 months compared with > 3 months and found either no difference or a lower risk of subsequent miscarriage.2,4-6