User login

VA Cancer Clinical Trials as a Strategy for Increasing Accrual of Racial and Ethnic Underrepresented Groups

Background

Cancer clinical trials (CCTs) are central to improving cancer care. However, generalizability of findings from CCTs is difficult due to the lack of diversity in most United States CCTs. Clinical trial accrual of underrepresented groups, is low throughout the United States and is approximately 4-5% in most CCTs. Reasons for low accrual in this population are multifactorial. Despite numerous factors related to accruing racial and ethnic underrepresented groups, many institutions have sought to address these barriers. We conducted a scoping review to identify evidence-based approaches to increase participation in cancer treatment clinical trials.

Methods

We reviewed the Salisbury VA Medical Center Oncology clinical trial database from October 2019 to June 2024. The participants in these clinical trials required consent. These clinical trials included treatment interventional as well as non-treatment interventional. Fifteen studies were included and over 260 Veterans participated.

Results

Key themes emerged that included a focus on patient education, cultural competency, and building capacity in the clinics to care for the Veteran population at three separate sites in the Salisbury VA system. The Black Veteran accrual rate of 29% was achieved. This accrual rate is representative of our VA catchment population of 33% for Black Veterans, and is five times the national average.

Conclusions

The research team’s success in enrolling Black Veterans in clinical trials is attributed to several factors. The demographic composition of Veterans served by the Salisbury, Charlotte, and Kernersville VA provided a diverse population that included a 33% Black group. The type of clinical trials focused on patients who were most impacted by the disease. The VA did afford less barriers to access to health care.

Background

Cancer clinical trials (CCTs) are central to improving cancer care. However, generalizability of findings from CCTs is difficult due to the lack of diversity in most United States CCTs. Clinical trial accrual of underrepresented groups, is low throughout the United States and is approximately 4-5% in most CCTs. Reasons for low accrual in this population are multifactorial. Despite numerous factors related to accruing racial and ethnic underrepresented groups, many institutions have sought to address these barriers. We conducted a scoping review to identify evidence-based approaches to increase participation in cancer treatment clinical trials.

Methods

We reviewed the Salisbury VA Medical Center Oncology clinical trial database from October 2019 to June 2024. The participants in these clinical trials required consent. These clinical trials included treatment interventional as well as non-treatment interventional. Fifteen studies were included and over 260 Veterans participated.

Results

Key themes emerged that included a focus on patient education, cultural competency, and building capacity in the clinics to care for the Veteran population at three separate sites in the Salisbury VA system. The Black Veteran accrual rate of 29% was achieved. This accrual rate is representative of our VA catchment population of 33% for Black Veterans, and is five times the national average.

Conclusions

The research team’s success in enrolling Black Veterans in clinical trials is attributed to several factors. The demographic composition of Veterans served by the Salisbury, Charlotte, and Kernersville VA provided a diverse population that included a 33% Black group. The type of clinical trials focused on patients who were most impacted by the disease. The VA did afford less barriers to access to health care.

Background

Cancer clinical trials (CCTs) are central to improving cancer care. However, generalizability of findings from CCTs is difficult due to the lack of diversity in most United States CCTs. Clinical trial accrual of underrepresented groups, is low throughout the United States and is approximately 4-5% in most CCTs. Reasons for low accrual in this population are multifactorial. Despite numerous factors related to accruing racial and ethnic underrepresented groups, many institutions have sought to address these barriers. We conducted a scoping review to identify evidence-based approaches to increase participation in cancer treatment clinical trials.

Methods

We reviewed the Salisbury VA Medical Center Oncology clinical trial database from October 2019 to June 2024. The participants in these clinical trials required consent. These clinical trials included treatment interventional as well as non-treatment interventional. Fifteen studies were included and over 260 Veterans participated.

Results

Key themes emerged that included a focus on patient education, cultural competency, and building capacity in the clinics to care for the Veteran population at three separate sites in the Salisbury VA system. The Black Veteran accrual rate of 29% was achieved. This accrual rate is representative of our VA catchment population of 33% for Black Veterans, and is five times the national average.

Conclusions

The research team’s success in enrolling Black Veterans in clinical trials is attributed to several factors. The demographic composition of Veterans served by the Salisbury, Charlotte, and Kernersville VA provided a diverse population that included a 33% Black group. The type of clinical trials focused on patients who were most impacted by the disease. The VA did afford less barriers to access to health care.

Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Treatment for Glomerulopathy: Case Report and Review of Literature

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

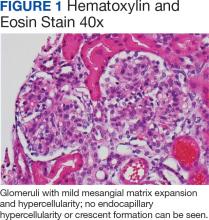

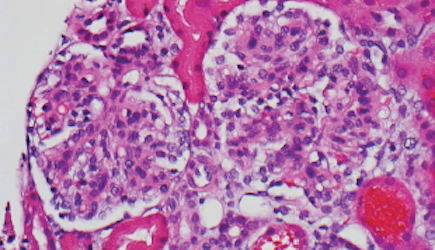

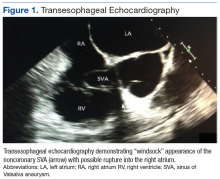

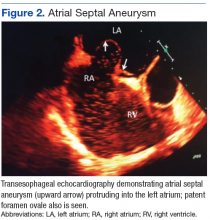

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

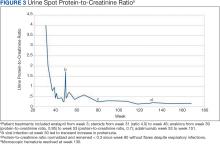

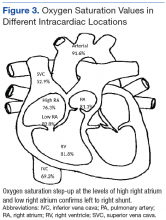

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, highly specialized cells located in juxtaposition to the basement membrane over the abluminal surfaces of endothelial cells within the glomerular tuft. This triad structure is the site of the filtration barrier, which forms highly delicate and tightly regulated architecture to carry out the ultrafiltration function of the kidney.1 The filtration barrier is characterized by foot processes that are connected by specialized junctions called slit diaphragms.

Insults to components of the filtration barrier can initiate cascading events and perpetuate structural alterations that may eventually result in sclerotic changes.2 Common causes among children include minimal change disease (MCD) with the collapse of foot processes resulting in proteinuria, Alport syndrome due to mutation of collagen fibers within the basement membrane leading to hematuria and proteinuria, immune complex mediated nephropathy following common infections or autoimmune diseases, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) that can show variable histopathology toward eventual glomerular scarring.3,4 These children often clinically have minimal, if any, signs of systemic inflammation.3-5 This has been a limiting factor for the commitment to immunomodulatory treatment, except for steroids for the treatment of MCD.6 Although prolonged steroid treatment may be efficacious, adverse effects are significant in a growing child. Alternative treatments, such as tacrolimus and rituximab have been suggested as second-line steroid-sparing agents.7,8 Not uncommonly, however, these cases are managed by supportive measures only during the progression of the natural course of the disease, which may eventually lead to renal failure, requiring transplant for survival.8,9

This case report highlights a child with a variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in genes involved in Alport syndrome and FSGS who developed an abrupt onset of proteinuria and hematuria after a respiratory illness. To our knowledge, he represents the youngest case demonstrating the benefit of targeted treatment against tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) for glomerulopathy using biologic response modifiers.

Case Description

This is currently a 7-year-old male patient who was born at 39 weeks gestation to gravida 3 para 3 following induced labor due to elevated maternal blood pressure. During the first 2 years of life, his growth and development were normal and his immunizations were up to date. The patient's medical history included upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), respiratory syncytial virus, as well as 3 bouts of pneumonia and multiple otitis media that resulted in 18 rounds of antibiotics. The child was also allergic to nuts and milk protein. The patient’s parents are of Northern European and Native American descent. There is no known family history of eye, ear, or kidney diseases.

Renal concerns were first noted at the age of 2 years and 6 months when he presented to an emergency department in Fall 2019 (week 0) for several weeks of intermittent dark-colored urine. His mother reported that the discoloration recently progressed in intensity to cola-colored, along with the onset of persistent vomiting without any fever or diarrhea. On physical examination, the patient had normal vitals: weight 14.8 kg (68th percentile), height 91 cm (24th percentile), and body surface area 0.6 m2. There was no edema, rash, or lymphadenopathy, but he appeared pale.

The patient’s initial laboratory results included: complete blood count with white blood cells (WBC) 10 x 103/L (reference range, 4.5-13.5 x 103/L); differential lymphocytes 69%; neutrophils 21%; hemoglobin 10 g/dL (reference range, 12-16 g/dL); hematocrit, 30%; (reference range, 37%-45%); platelets 437 103/L (reference range, 150-450 x 103/L); serum creatinine 0.46 mg/dL (reference range, 0.5-0.9 mg/dL); and albumin 3.1 g/dL (reference range, 3.5-5.2 g/dL). Serum electrolyte levels and liver enzymes were normal. A urine analysis revealed 3+ protein and 3+ blood with dysmorphic red blood cells (RBC) and RBC casts without WBC. The patient's spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio was 4.3 and his renal ultrasound was normal. The patient was referred to Nephrology.

During the next 2 weeks, his protein-to-creatinine ratio progressed to 5.9 and serum albumin fell to 2.7 g/dL. His urine remained red colored, and a microscopic examination with RBC > 500 and WBC up to 10 on a high powered field. His workup was negative for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antistreptolysin-O (ASO) and anti-DNase B. Serum C3 was low at 81 mg/dL (reference range, 90-180 mg/dL), C4 was 13.3 mg/dL (reference range, 10-40 mg/dL), and immunoglobulin G was low at 452 mg/dL (reference range 719-1475 mg/dL). A baseline audiology test revealed normal hearing.

Percutaneous renal biopsy yielded about 12 glomeruli, all exhibiting mild mesangial matrix expansion and hypercellularity (Figure 1). One glomerulus had prominent parietal epithelial cells without endocapillary hypercellularity or crescent formation. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Immunofluorescence studies showed no evidence of immune complex deposition with negative staining for immunoglobulin heavy and light chains, C3 and C1q. Staining for α 2 and α 5 units of collagen was normal. Electron microscopy showed patchy areas of severe basement membrane thinning with frequent foci of mild to moderate lamina densa splitting and associated visceral epithelial cell foot process effacement (Figure 2).

These were reported as concerning findings for possible Alport syndrome by 3 independent pathology teams. The genetic testing was submitted at a commercial laboratory to screen 17 mutations, including COL4A3, COL4A4, and COL4A5. Results showed the presence of a heterozygous VUS in the COL4A4 gene (c.1055C > T; p.Pro352Leu; dbSNP ID: rs371717486; PolyPhen-2: Probably Damaging; SIFT: Deleterious) as well as the presence of a heterozygous VUS in TRPC6 gene (c2463A>T; p.Lys821Asn; dbSNP ID: rs199948731; PolyPhen-2: Benign; SIFT: Tolerated). Further genetic investigation by whole exome sequencing on approximately 20,000 genes through MNG Laboratories showed a new heterozygous VUS in the OSGEP gene [c.328T>C; p.Cys110Arg]. Additional studies ruled out mitochondrial disease, CoQ10 deficiency, and metabolic disorders upon normal findings for mitochondrial DNA, urine amino acids, plasma acylcarnitine profile, orotic acid, ammonia, and homocysteine levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the patient’s treatment response during 170 weeks of follow-up (Fall 2019 to Summer 2023). The patient was started on enalapril 0.6 mg/kg daily at week 3, which continued throughout treatment. Following a rheumatology consult at week 30, the patient was started on prednisolone 3 mg/mL to assess the role of inflammation through the treatment response. An initial dose of 2 mg/kg daily (9 mL) for 1 month was followed by every other day treatment that was tapered off by week 48. To control mild but noticeably increasing proteinuria in the interim, subcutaneous anakinra 50 mg (3 mg/kg daily) was added as a steroid

DISCUSSION

This case describes a child with rapidly progressive proteinuria and hematuria following a URI who was found to have VUS mutations in 3 different genes associated with chronic kidney disease. Serology tests on the patient were negative for streptococcal antibodies and antinuclear antibodies, ruling out poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis, or systemic lupus erythematosus. His renal biopsy findings were concerning for altered podocytes, mesangial cells, and basement membrane without inflammatory infiltrate, immune complex, complements, immunoglobulin A, or vasculopathy. His blood inflammatory markers, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were normal when his care team initiated daily steroids.

Overall, the patient’s clinical presentation and histopathology findings were suggestive of Alport syndrome or thin basement membrane nephropathy with a high potential to progress into FSGS.10-12 Alport syndrome affects 1 in 5000 to 10,000 children annually due to S-linked inheritance of COL4A5, or autosomal recessive inheritance of COL4A3 or COL4A4 genes. It presents with hematuria and hearing loss.10 Our patient had a single copy COL4A4 gene mutation that was classified as VUS. He also had 2 additional VUS affecting the TRPC6 and OSGEP genes. TRPC6 gene mutation can be associated with FSGS through autosomal dominant inheritance. Both COL4A4 and TRPC6 gene mutations were paternally inherited. Although the patient’s father not having renal disease argues against the clinical significance of these findings, there is literature on the potential role of heterozygous COL4A4 variant mimicking thin basement membrane nephropathy that can lead to renal impairment upon copresence of superimposed conditions.13 The patient’s rapidly progressing hematuria and changes in the basement membrane were worrisome for emerging FSGS. Furthermore, VUS of TRPC6 has been reported in late onset autosomal dominant FSGS and can be associated with early onset steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (NS) in children.14 This concern was voiced by 3 nephrology consultants during the initial evaluation, leading to the consensus that steroid treatment for podocytopathy would not alter the patient’s long-term outcomes (ie, progression to FSGS).

Immunomodulation

Our rationale for immunomodulatory treatment was based on the abrupt onset of renal concerns following a URI, suggesting the importance of an inflammatory trigger causing altered homeostasis in a genetically susceptible host. Preclinical models show that microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides can lead to podocytopathy by several mechanisms through activation of toll-like receptor signaling. It can directly cause apoptosis by downregulation of the intracellular Akt survival pathway.15 Lipopolysaccharide can also activate the NF-αB pathway and upregulate the production of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and TNF-α in mesangial cells.16,17

Both cytokines can promote mesangial cell proliferation.18 Through autocrine and paracrine mechanisms, proinflammatory cytokines can further perpetuate somatic tissue changes and contribute to the development of podocytopathy. For instance, TNF-α can promote podocyte injury and proteinuria by downregulation of the slit diaphragm protein expression (ie, nephrin, ezrin, or podocin), and disruption of podocyte cytoskeleton.19,20 TNF-α promotes the influx and activation of macrophages and inflammatory cells. It is actively involved in chronic alterations within the glomeruli by the upregulation of matrix metalloproteases by integrins, as well as activation of myofibroblast progenitors and extracellular matrix deposition in crosstalk with transforming growth factor and other key mediators.17,21,22

For the patient described in this case report, initial improvement on steroids encouraged the pursuit of additional treatment to downregulate inflammatory pathways within the glomerular milieu. However, within the COVID-19 environment, escalating the patient’s treatment using traditional immunomodulators (ie, calcineurin inhibitors or mycophenolate mofetil) was not favored due to the risk of infection. Initially, anakinra, a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist, was preferred as a steroid-sparing agent for its short life and safety profile during the pandemic. At first, the patient responded well to anakinra and was allowed a steroid wean when the dose was titrated up to 6 mg/kg daily. However, anakinra did not prevent the escalation of proteinuria following a URI. After the treatment was changed to adalimumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody to TNF-α, the patient continued to improve and reach full remission despite experiencing a cold and the flu in the following months.

Literature Review

There is a paucity of literature on applications of biological response modifiers for idiopathic NS and FSGS.23,24 Angeletti and colleagues reported that 3 patients with severe long-standing FSGS benefited from anakinra 4 mg/kg daily to reduce proteinuria and improve kidney function. All the patients had positive C3 staining in renal biopsy and treatment response, which supported the role of C3a in inducing podocyte injury through upregulated expression of IL-1 and IL-1R.23 Trachtman and colleagues reported on the phase II FONT trial that included 14 of 21 patients aged < 18 years with advanced FSGS who were treated with adalimumab 24 mg/m2, or ≤ 40 mg every other week.24 Although, during a 6-month period, none of the 7 patients met the endpoint of reduced proteinuria by ≥ 50%, and the authors suggested that careful patient selection may improve the treatment response in future trials.24

A recent study involving transcriptomics on renal tissue samples combined with available pathology (fibrosis), urinary markers, and clinical characteristics on 285 patients with MCD or FSGS from 3 different continents identified 3 distinct clusters. Patients with evidence of activated kidney TNF pathway (n = 72, aged > 18 years) were found to have poor clinical outcomes.25 The study identified 2 urine markers associated with the TNF pathway (ie, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1), which aligns with the preclinical findings previously mentioned.25

Conclusions

The patient’s condition in this case illustrates the complex nature of biologically predetermined cascading events in the emergence of glomerular disease upon environmental triggers under the influence of genetic factors.

Chronic kidney disease affects 7.7% of veterans annually, illustrating the need for new therapeutics.26 Based on our experience and literature review, upregulation of TNF-α is a root cause of glomerulopathy; further studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of anti-TNF biologic response modifiers for the treatment of these patients. Long-term postmarketing safety profile and steroid-sparing properties of adalimumab should allow inclusion of pediatric cases in future trials. Results may also contribute to identifying new predictive biomarkers related to the basement membrane when combined with precision nephrology to further advance patient selection and targeted treatment.25,27

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient’s mother for providing consent to allow publication of this case report.

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

1. Arif E, Nihalani D. Glomerular filtration barrier assembly: an insight. Postdoc J. 2013;1(4):33-45.

2. Garg PA. Review of podocyte biology. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47(suppl 1):3-13. doi:10.1159/000481633SUPPL

3. Warady BA, Agarwal R, Bangalore S, et al. Alport syndrome classification and management. Kidney Med. 2020;2(5):639-649. doi:10.1016/j.xkme.2020.05.014

4. Angioi A, Pani A. FSGS: from pathogenesis to the histological lesion. J Nephrol. 2016;29(4):517-523. doi:10.1007/s40620-016-0333-2

5. Roca N, Martinez C, Jatem E, Madrid A, Lopez M, Segarra A. Activation of the acute inflammatory phase response in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: association with clinicopathological phenotypes and with response to corticosteroids. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(4):1207-1215. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfaa247

6. Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal change disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(2):332-345.

7. Medjeral-Thomas NR, Lawrence C, Condon M, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of tacrolimus and prednisolone monotherapy for adults with De Novo minimal change disease: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;15(2):209-218. doi:10.2215/CJN.06290420

8. Ye Q, Lan B, Liu H, Persson PB, Lai EY, Mao J. A critical role of the podocyte cytoskeleton in the pathogenesis of glomerular proteinuria and autoimmune podocytopathies. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2022;235(4):e13850. doi:10.1111/apha.13850

9. Trautmann A, Schnaidt S, Lipska-Ziμtkiewicz BS, et al. Long-term outcome of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3055-3065. doi:10.1681/ASN.2016101121

10. Kashtan CE, Gross O. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Alport syndrome in children, adolescents, and young adults-an update for 2020. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36(3):711-719. doi:10.1007/s00467-020-04819-6

11. Savige J, Rana K, Tonna S, Buzza M, Dagher H, Wang YY. Thin basement membrane nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;64(4):1169-78. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00234.x

12. Rosenberg AZ, Kopp JB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017; 12(3):502-517. doi:10.2215/CJN.05960616

13. Savige J. Should we diagnose autosomal dominant Alport syndrome when there is a pathogenic heterozygous COL4A3 or COL4A4 variant? Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3(6):1239-1241. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.08.002

14. Gigante M, Caridi G, Montemurno E, et al. TRPC6 mutations in children with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome and atypical phenotype. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(7):1626-1634. doi:10.2215/CJN.07830910

15. Saurus P, Kuusela S, Lehtonen E, et al. Podocyte apoptosis is prevented by blocking the toll-like receptor pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(5):e1752. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.125

16. Baud L, Oudinet JP, Bens M, et al. Production of tumor necrosis factor by rat mesangial cells in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1111-1118. doi:10.1038/ki.1989.98

17. White S, Lin L, Hu K. NF-κB and tPA signaling in kidney and other diseases. Cells. 2020;9(6):1348. doi:10.3390/cells9061348

18. Tesch GH, Lan HY, Atkins RC, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. Role of interleukin-1 in mesangial cell proliferation and matrix deposition in experimental mesangioproliferative nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151(1):141-150.

19. Lai KN, Leung JCK, Chan LYY, et al. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA Nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62-72. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfn441

20. Saleem MA, Kobayashi Y. Cell biology and genetics of minimal change disease. F1000 Res. 2016;5: F1000 Faculty Rev-412. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7300.1

21. Kim KP, Williams CE, Lemmon CA. Cell-matrix interactions in renal fibrosis. Kidney Dial. 2022;2(4):607-624. doi:10.3390/kidneydial2040055

22. Zvaifler NJ. Relevance of the stroma and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) for the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(3):210. doi:10.1186/ar1963

23. Angeletti A, Magnasco A, Trivelli A, et al. Refractory minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis treated with Anakinra. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;7(1):121-124. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2021.10.018

24. Trachtman H, Vento S, Herreshoff E, et al. Efficacy of galactose and adalimumab in patients with resistant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: report of the font clinical trial group. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:111. doi:10.1186/s12882-015-0094-5

25. Mariani LH, Eddy S, AlAkwaa FM, et al. Precision nephrology identified tumor necrosis factor activation variability in minimal change disease and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2023;103(3):565-579. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2022.10.023

26. Korshak L, Washington DL, Powell J, Nylen E, Kokkinos P. Kidney Disease in Veterans. US Dept of Veterans Affairs, Office of Health Equity. Updated May 13, 2020. Accessed June 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/HEALTHEQUITY/Kidney_Disease_In_Veterans.asp

27. Malone AF, Phelan PJ, Hall G, et al. Rare hereditary COL4A3/COL4A4 variants may be mistaken for familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2014;86(6):1253-1259. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.305

Improving Colorectal Cancer Screening via Mailed Fecal Immunochemical Testing in a Veterans Affairs Health System

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.

The second FIT letter arrived with the FIT kit, introduced FIT and described the importance of CRC screening. The letter detailed instructions for completing FIT and automatically created a FIT order. It also included a list of common conditions that may exclude patients, with a recommendation for patients to contact their medical team if they felt they were not candidates for FIT.

Staff Education

A previous VACHS pilot project demonstrated the success of a mailed FIT program to increase FIT use. Implemented as part of the pilot program, staff education consisted of a session for clinicians about the role of FIT in CRC screening and an all-staff education session. An additional education session about CRC and FIT for all staff was repeated with the program launch.

Program Launch

The mailed FIT program was introduced during a VACHS primary care all-staff meeting. After the meeting, each patient aligned care team (PACT) received an encrypted email that included a list of the patients on their team who were candidates for the program, a patient-facing FIT instruction sheet, detailed instructions on how to send the FIT primer letter, and a FIT package consisting of the labeled FIT kit, FIT letter, and patient instruction sheet. A reminder letter was sent to each patient 3 weeks after the FIT package was mailed. The patient lists were populated into a shared, encrypted Microsoft Teams folder that was edited in real time by PACT teams and viewed by VACHS leadership to track progress.

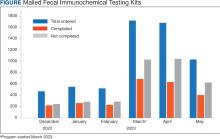

Program Metrics

At program launch, the VACHS had 4642 patients due for CRC screening who were eligible for the mailed FIT program. On March 7, 2023, the data consisting of FIT tests ordered between December 2022 and May 2023—3 months before and after the launch of the program—were reviewed and categorized. In the 3 months before program launch, 1528 FIT were ordered and 714 were returned (46.7%). In the 3 months after the launch of the program, 4383 FIT were ordered and 1712 were returned (39.1%) (Figure). Test orders increased 287% from the preintervention to the postintervention period. The mean (SD) number of monthly FIT tests prelaunch was 509 (32.7), which increased to 1461 (331.6) postlaunch.

At the VACHS, 61.4% of patients aged 45 to 75 years were up to date with CRC screening before the program launch. In the 3 months after program launch, the rate increased to 63.8% among patients aged 45 to 75 years, the highest rate in our Veterans Integrated Services Network and exceeding the VA national average CRC screening rate, according to unpublished VA Monthly Management Report data.

In the 3 months following the program launch, 139 FIT kits tested positive for potential CRC. Of these, 79 (56.8%) patients had completed a diagnostic colonoscopy. PACT PCPs and nurses received reports on patients with positive FIT tests and those with no colonoscopy scheduled or completed and were asked to follow up.

Discussion

Through a proactive, population-based CRC screening program centered on mailed FIT kits outside of the traditional patient visit, the VACHS increased the use of FIT and rates of CRC screening. The numbers of FIT kits ordered and completed substantially increased in the 3 months after program launch.

Compared to mailed FIT programs described in the literature that rely on centralized processes in that a separate team operates the mailed FIT program for the entire organization, this program used existing PACT infrastructure and staff.10,11 This strategy allowed VACHS to design and implement the program in several months. Not needing to hire new staff or create a central team for the sole purpose of implementing the program allowed us to save on any organizational funding and efforts that would have accompanied the additional staff. The program described in this article may be more attainable for primary care practices or smaller health systems that do not have the capacity for the creation of a centralized process.

Limitations

Although the total number of FIT completions substantially increased during the program, the rate of FIT completion during the mailed FIT program was lower than the rate of completion prior to program launch. This decreased rate of FIT kit completion may be related to separation from a patient visit and potential loss of real-time education with a clinician. The program’s decentralized design increased the existing workload for primary care staff, and as a result, consideration must be given to local staffing levels. Additionally, the report of eligible patients depended on diagnosis codes and may have captured patients with higher-than-average risk of CRC, such as patients with prior history of adenomatous polyps, family history of CRC, or other medical or genetic conditions. We attempted to mitigate this by including a list of conditions that would exclude patients from FIT eligibility in the FIT letter and giving them the option to opt out.

Conclusions

CRC screening rates improved following implementation of a primary care team-centered quality improvement process to proactively identify patients appropriate for FIT and mail them FIT kits. This project highlights that population-health interventions around CRC screening via use of FIT can be successful within a primary care patient-centered medical home model, considering the increases in both CRC screening rates and increase in FIT tests ordered.

1. American Cancer Society. Key statistics for colorectal cancer. Revised January 29, 2024. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

2. Chen RC, Haynes K, Du S, Barron J, Katz AJ. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878-884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884

3. Mazidimoradi A, Tiznobaik A, Salehiniya H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2022;53(3):730-744. doi:10.1007/s12029-021-00679-x

4. Adams MA, Kurlander JE, Gao Y, Yankey N, Saini SD. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on screening colonoscopy utilization in a large integrated health system. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(7):2098-2100.e2. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.02.034

5. Sundaram S, Olson S, Sharma P, Rajendra S. A review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening: implications and solutions. Pathogens. 2021;10(11):558. doi:10.3390/pathogens10111508

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

7. Robertson DJ, Lee JK, Boland CR, et al. Recommendations on fecal immunochemical testing to screen for colorectal neoplasia: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(1):2-21.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.09.025

8. Lee JK, Liles EG, Bent S, Levin TR, Corley DA. Accuracy of fecal immunochemical tests for colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(3):171. doi:10.7326/M13-1484

9. Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(1):307-323. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.013

10. Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4):e001927. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

11. Selby K, Jensen CD, Levin TR, et al. Program components and results from an organized colorectal cancer screening program using annual fecal immunochemical testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(1):145-152. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.042

12. Deeds S, Liu T, Schuttner L, et al. A postcard primer prior to mailed fecal immunochemical test among veterans: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023:38(14):3235-3241. doi:10.1007/s11606-023-08248-7

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is among the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related deaths in the United States.1 Reflective of a nationwide trend, CRC screening rates at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System (VACHS) decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic.2-5 Contributing factors to this decrease included cancellations of elective colonoscopies during the initial phase of the pandemic and concurrent turnover of endoscopists. In 2021, the US Preventive Services Task Force lowered the recommended initial CRC screening age from 50 years to 45 years, further increasing the backlog of unscreened patients.6

Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a noninvasive screening method in which antibodies are used to detect hemoglobin in the stool. The sensitivity and specificity of 1-time FIT are 79% to 80% and 94%, respectively, for the detection of CRC, with sensitivity improving with successive testing.7,8 Annual FIT is recognized as a tier 1 preferred screening method by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7,9 Programs that mail FIT kits to eligible patients outside of physician visits have been successfully implemented in health care systems.10,11

The VACHS designed and implemented a mailed FIT program using existing infrastructure and staffing.

Program Description

A team of local stakeholders comprised of VACHS leadership, primary care, nursing, and gastroenterology staff, as well as representatives from laboratory, informatics, mail services, and group practice management, was established to execute the project. The team met monthly to plan the project.

The team developed a dataset consisting of patients aged 45 to 75 years who were at average risk for CRC and due for CRC screening. Patients were defined as due for CRC screening if they had not had a colonoscopy in the previous 9 years or a FIT or fecal occult blood test in the previous 11 months. Average risk for CRC was defined by excluding patients with associated diagnosis codes for CRC, colectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, and anemia. The program also excluded patients with diagnosis codes associated with dementia, deferring discussions about cancer screening to their primary care practitioners (PCPs). Patients with invalid mailing addresses were also excluded, as well as those whose PCPs had indicated in the electronic health record that the patient received CRC screening outside the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system.

Letter Templates

Two patient letter electronic health record templates were developed. The first was a primer letter, which was mailed to patients 2 to 3 weeks before the mailed FIT kit as an introduction to the program.12 The purpose of the primer letter was to give advance notice to patients that they could expect a FIT kit to arrive in the mail. The goal was to prepare patients to complete FIT when the kit arrived and prompt them to call the VA to opt out of the mailed FIT program if they were up to date with CRC screening or if they had a condition which made them at high risk for CRC.