User login

PRISm and nonspecific pattern: New insights in lung testing interpretation

The recent statement on interpretive strategies for lung testing uses the acronym PRISm for preserved ratio impaired spirometry. PRISm identifies patients with a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio but abnormal FEV1 and/or FVC (usually both). Most medical students are taught to call this a “restrictive pattern,” and every first-year pulmonary fellow orders full lung volumes when they see it. If total lung capacity (TLC) is normal, PRISm becomes the nonspecific pattern. If TLC is low, then the patient has “true” restriction, and if it’s elevated, then hyperinflation may be present.

The traditional classification scheme for basic spirometry interpretation (normal, restricted, obstructed, or mixed) is simple and conceptually clear. It turns out that many with this pattern won’t have an abnormal TLC, so the name is, in some ways, a misnomer and can be misleading. Enter PRISm, a more descriptive and inclusive term. The phrase also lends itself to a phonetic acronym that is fun to say, easy to remember, and likely to catch on with learners.

Information on occurrence and clinical behavior comes from large cohorts with basic spirometry, but without full lung volumes because PRISm no longer applies once TLC is determined. As may be expected, prevalence varies by the population studied. Estimates for general populations have been in the 7%-12% range; however, one study examining a database of patients with clinical spirometry referrals found a prevalence of 22.3%. Rates may be far higher in low- and middle-income countries. Identified risk factors include sex, tobacco use, and body mass index; the presence of PRISm is associated with respiratory symptoms and mortality. Thus, PRISm is common and it matters.

Along with PRISm, the nonspecific pattern is a new addition, if not a new concept, to the 2022 interpretative strategies statement. As with PRISm, the title is necessarily broad, though far less imaginative. Defined by reductions in FEV1 and FVC and a normal TLC, the nonspecific pattern has classically been considered a marker of early airway disease. The idea is that early, heterogeneous closure of distal segments of the bronchial tree can reduce total volume during a forced expiration before affecting the FEV1/FVC. The fact that the TLC is not a forced maneuver means there is proportionately less effect from more collapsible/susceptible smaller units. More recent data suggest that there are additional causes.

Because the nonspecific pattern requires full lung volumes, we have less population-level data than for PRISm. Estimated prevalence is approximately 9.5% in patients with complete test results. The two most common causes are obesity and airway obstruction, and the pattern is relatively stable over time. Notably, an increase in specific airway resistance or TLC minus alveolar volume difference predicts progression to frank obstruction on spirometry.

The physiologic changes that obesity inflicts on the lung have been well described. Patients with obesity breathe at lower lung volumes and are therefore susceptible to small airway closure at rest and during forced expiration. There is no doubt that the increased recognition of PRISm and the nonspecific pattern is in part related to the worldwide rise in obesity rates.

Key takeaways

In summary, PRISm and the nonspecific pattern are now part of the classification scheme we use for spirometry and full lung volumes, respectively. They should be included in interpretations given their diagnostic and predictive value. Airway disease and obesity are common causes and often coexist with either pattern. Many will not have a true, restrictive lung deficit, and a reductionist approach to interpretation is likely to lead to erroneous diagnoses. There were many important updates included in the 2022 iteration on lung testing interpretation that should not fly under the radar.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with CHEST College, Metapharm, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The recent statement on interpretive strategies for lung testing uses the acronym PRISm for preserved ratio impaired spirometry. PRISm identifies patients with a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio but abnormal FEV1 and/or FVC (usually both). Most medical students are taught to call this a “restrictive pattern,” and every first-year pulmonary fellow orders full lung volumes when they see it. If total lung capacity (TLC) is normal, PRISm becomes the nonspecific pattern. If TLC is low, then the patient has “true” restriction, and if it’s elevated, then hyperinflation may be present.

The traditional classification scheme for basic spirometry interpretation (normal, restricted, obstructed, or mixed) is simple and conceptually clear. It turns out that many with this pattern won’t have an abnormal TLC, so the name is, in some ways, a misnomer and can be misleading. Enter PRISm, a more descriptive and inclusive term. The phrase also lends itself to a phonetic acronym that is fun to say, easy to remember, and likely to catch on with learners.

Information on occurrence and clinical behavior comes from large cohorts with basic spirometry, but without full lung volumes because PRISm no longer applies once TLC is determined. As may be expected, prevalence varies by the population studied. Estimates for general populations have been in the 7%-12% range; however, one study examining a database of patients with clinical spirometry referrals found a prevalence of 22.3%. Rates may be far higher in low- and middle-income countries. Identified risk factors include sex, tobacco use, and body mass index; the presence of PRISm is associated with respiratory symptoms and mortality. Thus, PRISm is common and it matters.

Along with PRISm, the nonspecific pattern is a new addition, if not a new concept, to the 2022 interpretative strategies statement. As with PRISm, the title is necessarily broad, though far less imaginative. Defined by reductions in FEV1 and FVC and a normal TLC, the nonspecific pattern has classically been considered a marker of early airway disease. The idea is that early, heterogeneous closure of distal segments of the bronchial tree can reduce total volume during a forced expiration before affecting the FEV1/FVC. The fact that the TLC is not a forced maneuver means there is proportionately less effect from more collapsible/susceptible smaller units. More recent data suggest that there are additional causes.

Because the nonspecific pattern requires full lung volumes, we have less population-level data than for PRISm. Estimated prevalence is approximately 9.5% in patients with complete test results. The two most common causes are obesity and airway obstruction, and the pattern is relatively stable over time. Notably, an increase in specific airway resistance or TLC minus alveolar volume difference predicts progression to frank obstruction on spirometry.

The physiologic changes that obesity inflicts on the lung have been well described. Patients with obesity breathe at lower lung volumes and are therefore susceptible to small airway closure at rest and during forced expiration. There is no doubt that the increased recognition of PRISm and the nonspecific pattern is in part related to the worldwide rise in obesity rates.

Key takeaways

In summary, PRISm and the nonspecific pattern are now part of the classification scheme we use for spirometry and full lung volumes, respectively. They should be included in interpretations given their diagnostic and predictive value. Airway disease and obesity are common causes and often coexist with either pattern. Many will not have a true, restrictive lung deficit, and a reductionist approach to interpretation is likely to lead to erroneous diagnoses. There were many important updates included in the 2022 iteration on lung testing interpretation that should not fly under the radar.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with CHEST College, Metapharm, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The recent statement on interpretive strategies for lung testing uses the acronym PRISm for preserved ratio impaired spirometry. PRISm identifies patients with a normal forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio but abnormal FEV1 and/or FVC (usually both). Most medical students are taught to call this a “restrictive pattern,” and every first-year pulmonary fellow orders full lung volumes when they see it. If total lung capacity (TLC) is normal, PRISm becomes the nonspecific pattern. If TLC is low, then the patient has “true” restriction, and if it’s elevated, then hyperinflation may be present.

The traditional classification scheme for basic spirometry interpretation (normal, restricted, obstructed, or mixed) is simple and conceptually clear. It turns out that many with this pattern won’t have an abnormal TLC, so the name is, in some ways, a misnomer and can be misleading. Enter PRISm, a more descriptive and inclusive term. The phrase also lends itself to a phonetic acronym that is fun to say, easy to remember, and likely to catch on with learners.

Information on occurrence and clinical behavior comes from large cohorts with basic spirometry, but without full lung volumes because PRISm no longer applies once TLC is determined. As may be expected, prevalence varies by the population studied. Estimates for general populations have been in the 7%-12% range; however, one study examining a database of patients with clinical spirometry referrals found a prevalence of 22.3%. Rates may be far higher in low- and middle-income countries. Identified risk factors include sex, tobacco use, and body mass index; the presence of PRISm is associated with respiratory symptoms and mortality. Thus, PRISm is common and it matters.

Along with PRISm, the nonspecific pattern is a new addition, if not a new concept, to the 2022 interpretative strategies statement. As with PRISm, the title is necessarily broad, though far less imaginative. Defined by reductions in FEV1 and FVC and a normal TLC, the nonspecific pattern has classically been considered a marker of early airway disease. The idea is that early, heterogeneous closure of distal segments of the bronchial tree can reduce total volume during a forced expiration before affecting the FEV1/FVC. The fact that the TLC is not a forced maneuver means there is proportionately less effect from more collapsible/susceptible smaller units. More recent data suggest that there are additional causes.

Because the nonspecific pattern requires full lung volumes, we have less population-level data than for PRISm. Estimated prevalence is approximately 9.5% in patients with complete test results. The two most common causes are obesity and airway obstruction, and the pattern is relatively stable over time. Notably, an increase in specific airway resistance or TLC minus alveolar volume difference predicts progression to frank obstruction on spirometry.

The physiologic changes that obesity inflicts on the lung have been well described. Patients with obesity breathe at lower lung volumes and are therefore susceptible to small airway closure at rest and during forced expiration. There is no doubt that the increased recognition of PRISm and the nonspecific pattern is in part related to the worldwide rise in obesity rates.

Key takeaways

In summary, PRISm and the nonspecific pattern are now part of the classification scheme we use for spirometry and full lung volumes, respectively. They should be included in interpretations given their diagnostic and predictive value. Airway disease and obesity are common causes and often coexist with either pattern. Many will not have a true, restrictive lung deficit, and a reductionist approach to interpretation is likely to lead to erroneous diagnoses. There were many important updates included in the 2022 iteration on lung testing interpretation that should not fly under the radar.

Dr. Holley is professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Md., and a pulmonary/sleep and critical care medicine physician at MedStar Washington Hospital Center in Washington. He disclosed ties with CHEST College, Metapharm, and WebMD.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Scrubs & Heels Summit 2023: Filling a void for women in GI

.1-3 This gender disparity arises from a multitude of factors including lack of effective mentoring, unequal leadership and career advancement opportunities, and pay inequity. In this context, The Scrubs & Heels Leadership Summit (S&H) was launched in 2022 focused on the professional and personal development of women in gastroenterology.

I had the great pleasure and honor of attending the 2023 summit which took place in February in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif. There were nearly 200 attendees ranging from trainees to midcareer and senior gastroenterologists and other health care professionals from both academia and private practices across the nation. The weekend course was directed by S&H cofounders, Dr. Aline Charabaty and Dr. Anita Afzali, and cochaired by Dr. Amy Oxentenko and Dr. Aja McCutchen.

The 2-day summit opened with a presentation by Sally Helgesen, author of How Women Rise, describing the 12 common habits that often hold women back in career advancement, promotion, or opportunities. Dr. Aline Charabaty addressed the myth of women needing to fulfill the role of superwoman or have suprahuman abilities. Attendees were challenged to reframe this societal construct and begin to find balance and the reasonable choice to switch to part-time work and, as Dr. Aja McCutch emphasized, dial-down responsibilities to maintain wellness when life has competing priorities.

Dr. Amy Oxentenko shared her personal journey to success and instilled the importance of engaging with community and society at large. We then heard from Dr. Neena Abraham on how to gracefully embrace transitions in our professional lives, whether intentionally sought or natural progressions of a career. She encouraged attendees to control our own narrative and seek challenges that promote growth. We explored different practice models with Dr. Caroline Hwang and learned strategies of switching from academics to private practice or vice versa. We also heard from cofounder Dr. Anita Afzali on becoming a physician executive and the importance of staying connected to patient care when rising in ranks of leadership.

The second day opened with a keynote address delivered by Dr. Marla Dubinsky detailing her journey of becoming a CEO of a publicly-traded company while retaining her role as professor and chief of pediatric gastroenterology in a large academic institution. Attendees were provided with a master class on discovering ways to inspire our inner entrepreneur and highlighted the benefit of physicians, especially women, in being effective business leaders. This talk was followed by a talk by Phil Schoenfeld, MD, FACS, editor-in-chief of Evidence-Based GI for the American College of Gastroenterology. He spoke on the importance of male allyship for women in GI and shared his personal experiences and challenges with allyship.

The summit included a breakout session by Dr. Rashmi Advani designed for residents to hear tips on how to have a successful fellowship match and for fellows to embrace a steep learning curve when starting and included tips for efficiency. Additional breakout sessions included learning ergonomic strategies for positioning and scope-holding, vocal-cord exercises before giving oral presentations, and how to formulate a business plan and negotiate a contract.

We ended the summit with uplifting advice from executive coaches Sonia Narang and Dr. Dawn Sears who taught us the art of leaning into opportunities, mansizing aspirations, finding coconspirators for amplification of female GI leaders, and supporting our colleagues personally and professionally.

Three key takeaway messages:

- Recognize your self-worth and the contributions you bring to your patients and community as a whole.

- Lean into the importance of vocalizing your asks, advocating for yourself, building your brand, and showcasing your accomplishments.

- Be mindful of the balance between the time and energy you dedicate towards goals that bring you recognition and fuel your passion and your mental, physical, and emotional health.

As a trainee, I benefited tremendously from attending and expanding my professional network of mentors, sponsors and colleagues. I am encouraged by this programming and hope to see more of it in the future.

Contributors to this article included: Rashmi Advani, MD2; Anita Afzali, MD3; Aline Charabaty, MD.4

Neither Dr. Syed, nor the article contributors, had financial conflicts of interest associated with this article. The AGA was represented at the Scrubs and Heels Summit as a society partner committed to the advancement of women in GI. AGA is building on years of efforts to bolster leadership, mentorship, and sponsorship among women in GI through its annual women’s leadership conference and most recently with its 2022 regional women in GI workshops held around the country that led to the development of a comprehensive gender equity strategy designed to build an environment of gender equity in the field of GI so that all can thrive.

Institutions and social media handle

1. Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, Calif), @noorannemd

2. Cedars Sinai (Los Angeles), @AdvaniRashmiMD

3. University of Cincinnati, @IBD_Afzali

4. Johns Hopkins Medicine (Washington), @DCharabaty

References

Advani R et al. Gender-specific attitudes of internal medicine residents toward gastroenterology. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Nov;67(11):5044-52.

American Association of Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures (2019).

Elta GH. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:259-64

David, Yakira N. et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 116.3 (2021):539-50.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:1047-56.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Survey finds gender disparities impact both women mentors and mentees in gastroenterology. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 2021;116:1876-84.

.1-3 This gender disparity arises from a multitude of factors including lack of effective mentoring, unequal leadership and career advancement opportunities, and pay inequity. In this context, The Scrubs & Heels Leadership Summit (S&H) was launched in 2022 focused on the professional and personal development of women in gastroenterology.

I had the great pleasure and honor of attending the 2023 summit which took place in February in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif. There were nearly 200 attendees ranging from trainees to midcareer and senior gastroenterologists and other health care professionals from both academia and private practices across the nation. The weekend course was directed by S&H cofounders, Dr. Aline Charabaty and Dr. Anita Afzali, and cochaired by Dr. Amy Oxentenko and Dr. Aja McCutchen.

The 2-day summit opened with a presentation by Sally Helgesen, author of How Women Rise, describing the 12 common habits that often hold women back in career advancement, promotion, or opportunities. Dr. Aline Charabaty addressed the myth of women needing to fulfill the role of superwoman or have suprahuman abilities. Attendees were challenged to reframe this societal construct and begin to find balance and the reasonable choice to switch to part-time work and, as Dr. Aja McCutch emphasized, dial-down responsibilities to maintain wellness when life has competing priorities.

Dr. Amy Oxentenko shared her personal journey to success and instilled the importance of engaging with community and society at large. We then heard from Dr. Neena Abraham on how to gracefully embrace transitions in our professional lives, whether intentionally sought or natural progressions of a career. She encouraged attendees to control our own narrative and seek challenges that promote growth. We explored different practice models with Dr. Caroline Hwang and learned strategies of switching from academics to private practice or vice versa. We also heard from cofounder Dr. Anita Afzali on becoming a physician executive and the importance of staying connected to patient care when rising in ranks of leadership.

The second day opened with a keynote address delivered by Dr. Marla Dubinsky detailing her journey of becoming a CEO of a publicly-traded company while retaining her role as professor and chief of pediatric gastroenterology in a large academic institution. Attendees were provided with a master class on discovering ways to inspire our inner entrepreneur and highlighted the benefit of physicians, especially women, in being effective business leaders. This talk was followed by a talk by Phil Schoenfeld, MD, FACS, editor-in-chief of Evidence-Based GI for the American College of Gastroenterology. He spoke on the importance of male allyship for women in GI and shared his personal experiences and challenges with allyship.

The summit included a breakout session by Dr. Rashmi Advani designed for residents to hear tips on how to have a successful fellowship match and for fellows to embrace a steep learning curve when starting and included tips for efficiency. Additional breakout sessions included learning ergonomic strategies for positioning and scope-holding, vocal-cord exercises before giving oral presentations, and how to formulate a business plan and negotiate a contract.

We ended the summit with uplifting advice from executive coaches Sonia Narang and Dr. Dawn Sears who taught us the art of leaning into opportunities, mansizing aspirations, finding coconspirators for amplification of female GI leaders, and supporting our colleagues personally and professionally.

Three key takeaway messages:

- Recognize your self-worth and the contributions you bring to your patients and community as a whole.

- Lean into the importance of vocalizing your asks, advocating for yourself, building your brand, and showcasing your accomplishments.

- Be mindful of the balance between the time and energy you dedicate towards goals that bring you recognition and fuel your passion and your mental, physical, and emotional health.

As a trainee, I benefited tremendously from attending and expanding my professional network of mentors, sponsors and colleagues. I am encouraged by this programming and hope to see more of it in the future.

Contributors to this article included: Rashmi Advani, MD2; Anita Afzali, MD3; Aline Charabaty, MD.4

Neither Dr. Syed, nor the article contributors, had financial conflicts of interest associated with this article. The AGA was represented at the Scrubs and Heels Summit as a society partner committed to the advancement of women in GI. AGA is building on years of efforts to bolster leadership, mentorship, and sponsorship among women in GI through its annual women’s leadership conference and most recently with its 2022 regional women in GI workshops held around the country that led to the development of a comprehensive gender equity strategy designed to build an environment of gender equity in the field of GI so that all can thrive.

Institutions and social media handle

1. Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, Calif), @noorannemd

2. Cedars Sinai (Los Angeles), @AdvaniRashmiMD

3. University of Cincinnati, @IBD_Afzali

4. Johns Hopkins Medicine (Washington), @DCharabaty

References

Advani R et al. Gender-specific attitudes of internal medicine residents toward gastroenterology. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Nov;67(11):5044-52.

American Association of Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures (2019).

Elta GH. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:259-64

David, Yakira N. et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 116.3 (2021):539-50.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:1047-56.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Survey finds gender disparities impact both women mentors and mentees in gastroenterology. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 2021;116:1876-84.

.1-3 This gender disparity arises from a multitude of factors including lack of effective mentoring, unequal leadership and career advancement opportunities, and pay inequity. In this context, The Scrubs & Heels Leadership Summit (S&H) was launched in 2022 focused on the professional and personal development of women in gastroenterology.

I had the great pleasure and honor of attending the 2023 summit which took place in February in Rancho Palos Verdes, Calif. There were nearly 200 attendees ranging from trainees to midcareer and senior gastroenterologists and other health care professionals from both academia and private practices across the nation. The weekend course was directed by S&H cofounders, Dr. Aline Charabaty and Dr. Anita Afzali, and cochaired by Dr. Amy Oxentenko and Dr. Aja McCutchen.

The 2-day summit opened with a presentation by Sally Helgesen, author of How Women Rise, describing the 12 common habits that often hold women back in career advancement, promotion, or opportunities. Dr. Aline Charabaty addressed the myth of women needing to fulfill the role of superwoman or have suprahuman abilities. Attendees were challenged to reframe this societal construct and begin to find balance and the reasonable choice to switch to part-time work and, as Dr. Aja McCutch emphasized, dial-down responsibilities to maintain wellness when life has competing priorities.

Dr. Amy Oxentenko shared her personal journey to success and instilled the importance of engaging with community and society at large. We then heard from Dr. Neena Abraham on how to gracefully embrace transitions in our professional lives, whether intentionally sought or natural progressions of a career. She encouraged attendees to control our own narrative and seek challenges that promote growth. We explored different practice models with Dr. Caroline Hwang and learned strategies of switching from academics to private practice or vice versa. We also heard from cofounder Dr. Anita Afzali on becoming a physician executive and the importance of staying connected to patient care when rising in ranks of leadership.

The second day opened with a keynote address delivered by Dr. Marla Dubinsky detailing her journey of becoming a CEO of a publicly-traded company while retaining her role as professor and chief of pediatric gastroenterology in a large academic institution. Attendees were provided with a master class on discovering ways to inspire our inner entrepreneur and highlighted the benefit of physicians, especially women, in being effective business leaders. This talk was followed by a talk by Phil Schoenfeld, MD, FACS, editor-in-chief of Evidence-Based GI for the American College of Gastroenterology. He spoke on the importance of male allyship for women in GI and shared his personal experiences and challenges with allyship.

The summit included a breakout session by Dr. Rashmi Advani designed for residents to hear tips on how to have a successful fellowship match and for fellows to embrace a steep learning curve when starting and included tips for efficiency. Additional breakout sessions included learning ergonomic strategies for positioning and scope-holding, vocal-cord exercises before giving oral presentations, and how to formulate a business plan and negotiate a contract.

We ended the summit with uplifting advice from executive coaches Sonia Narang and Dr. Dawn Sears who taught us the art of leaning into opportunities, mansizing aspirations, finding coconspirators for amplification of female GI leaders, and supporting our colleagues personally and professionally.

Three key takeaway messages:

- Recognize your self-worth and the contributions you bring to your patients and community as a whole.

- Lean into the importance of vocalizing your asks, advocating for yourself, building your brand, and showcasing your accomplishments.

- Be mindful of the balance between the time and energy you dedicate towards goals that bring you recognition and fuel your passion and your mental, physical, and emotional health.

As a trainee, I benefited tremendously from attending and expanding my professional network of mentors, sponsors and colleagues. I am encouraged by this programming and hope to see more of it in the future.

Contributors to this article included: Rashmi Advani, MD2; Anita Afzali, MD3; Aline Charabaty, MD.4

Neither Dr. Syed, nor the article contributors, had financial conflicts of interest associated with this article. The AGA was represented at the Scrubs and Heels Summit as a society partner committed to the advancement of women in GI. AGA is building on years of efforts to bolster leadership, mentorship, and sponsorship among women in GI through its annual women’s leadership conference and most recently with its 2022 regional women in GI workshops held around the country that led to the development of a comprehensive gender equity strategy designed to build an environment of gender equity in the field of GI so that all can thrive.

Institutions and social media handle

1. Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (San Jose, Calif), @noorannemd

2. Cedars Sinai (Los Angeles), @AdvaniRashmiMD

3. University of Cincinnati, @IBD_Afzali

4. Johns Hopkins Medicine (Washington), @DCharabaty

References

Advani R et al. Gender-specific attitudes of internal medicine residents toward gastroenterology. Dig Dis Sci. 2022 Nov;67(11):5044-52.

American Association of Medical Colleges. Diversity in Medicine: Facts and Figures (2019).

Elta GH. The challenges of being a female gastroenterologist. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):441-7.

Burke CA et al. Gender disparity in the practice of gastroenterology: The first 5 years of a career. Am J Gastroenterol 2005;100:259-64

David, Yakira N. et al. Gender-specific factors influencing gastroenterologists to pursue careers in advanced endoscopy: perceptions vs reality. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 116.3 (2021):539-50.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Gender dynamics in education and practice of gastroenterology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;93:1047-56.

Rabinowitz LG et al. Survey finds gender disparities impact both women mentors and mentees in gastroenterology. Journal of the American College of Gastroenterology, ACG 2021;116:1876-84.

A new and completely different pain medicine

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

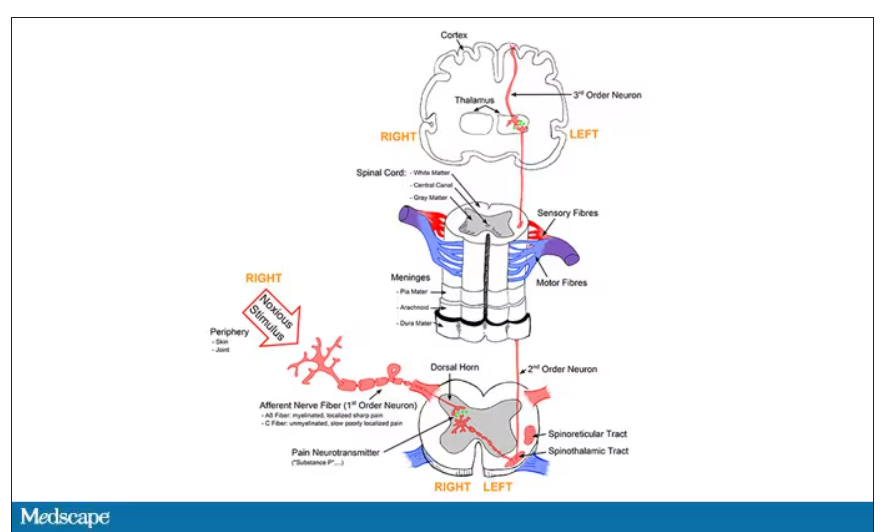

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

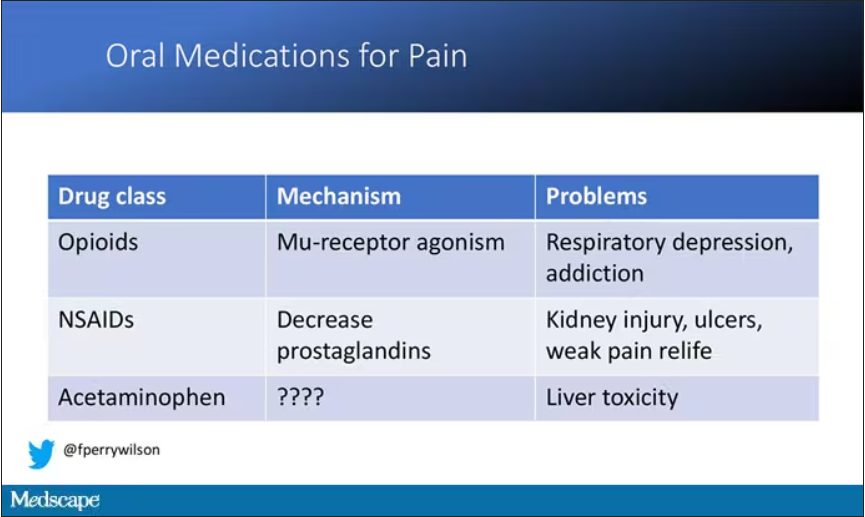

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

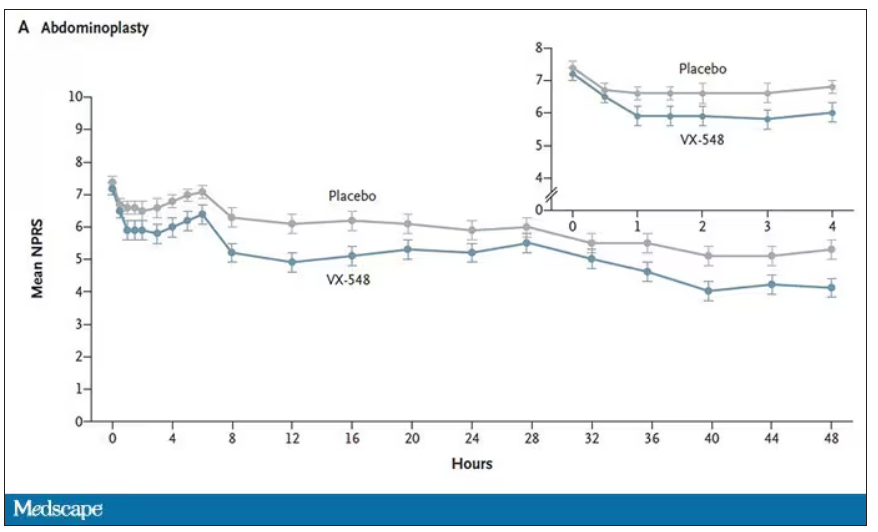

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

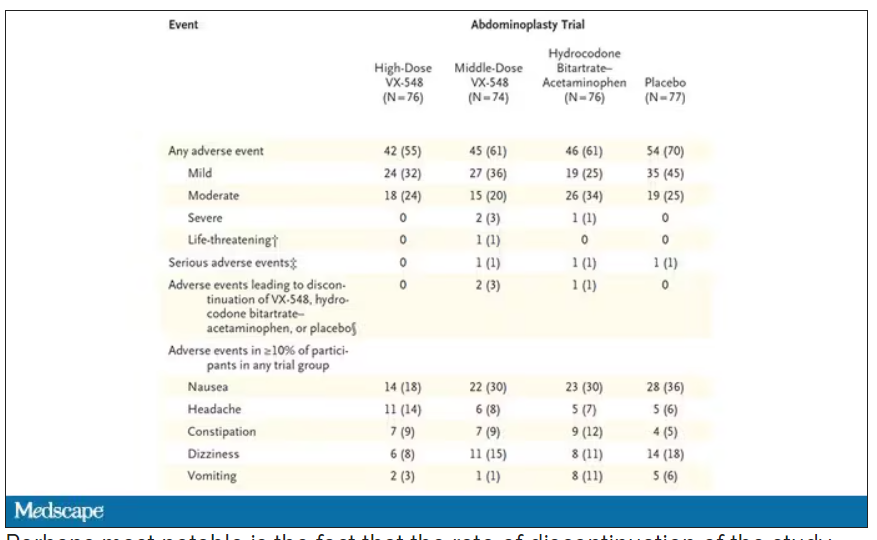

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

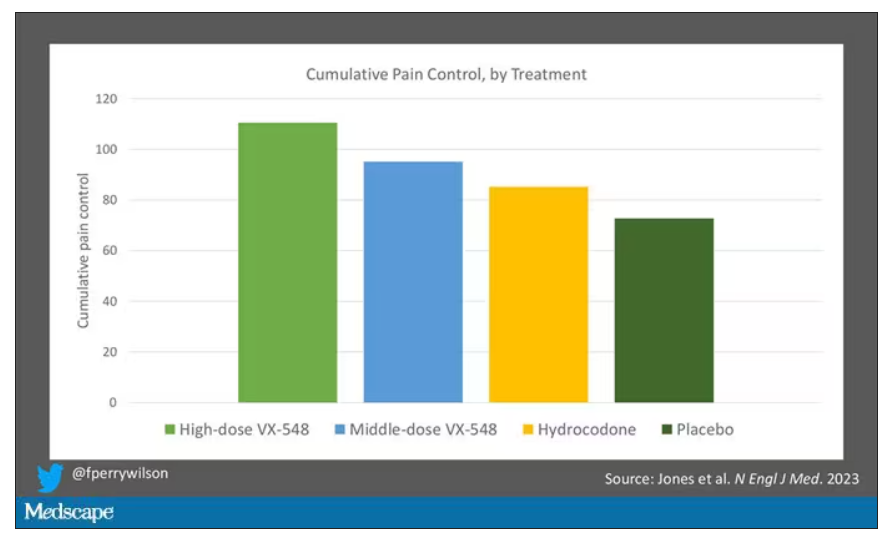

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When you stub your toe or get a paper cut on your finger, you feel the pain in that part of your body. It feels like the pain is coming from that place. But, of course, that’s not really what is happening. Pain doesn’t really happen in your toe or your finger. It happens in your brain.

It’s a game of telephone, really. The afferent nerve fiber detects the noxious stimulus, passing that signal to the second-order neuron in the dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord, which runs it up to the thalamus to be passed to the third-order neuron which brings it to the cortex for localization and conscious perception. It’s not even a very good game of telephone. It takes about 100 ms for a pain signal to get from the hand to the brain – longer from the feet, given the greater distance. You see your foot hit the corner of the coffee table and have just enough time to think: “Oh no!” before the pain hits.

Given the Rube Goldberg nature of the process, it would seem like there are any number of places we could stop pain sensation. And sure, local anesthetics at the site of injury, or even spinal anesthetics, are powerful – if temporary and hard to administer – solutions to acute pain.

But in our everyday armamentarium, let’s be honest – we essentially have three options: opiates and opioids, which activate the mu-receptors in the brain to dull pain (and cause a host of other nasty side effects); NSAIDs, which block prostaglandin synthesis and thus limit the ability for pain-conducting neurons to get excited; and acetaminophen, which, despite being used for a century, is poorly understood.

But

If you were to zoom in on the connection between that first afferent pain fiber and the secondary nerve in the spinal cord dorsal root ganglion, you would see a receptor called Nav1.8, a voltage-gated sodium channel.

This receptor is a key part of the apparatus that passes information from nerve 1 to nerve 2, but only for fibers that transmit pain signals. In fact, humans with mutations in this receptor that leave it always in the “open” state have a severe pain syndrome. Blocking the receptor, therefore, might reduce pain.

In preclinical work, researchers identified VX-548, which doesn’t have a brand name yet, as a potent blocker of that channel even in nanomolar concentrations. Importantly, the compound was highly selective for that particular channel – about 30,000 times more selective than it was for the other sodium channels in that family.

Of course, a highly selective and specific drug does not a blockbuster analgesic make. To determine how this drug would work on humans in pain, they turned to two populations: 303 individuals undergoing abdominoplasty and 274 undergoing bunionectomy, as reported in a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I know this seems a bit random, but abdominoplasty is quite painful and a good model for soft-tissue pain. Bunionectomy is also quite a painful procedure and a useful model of bone pain. After the surgeries, patients were randomized to several different doses of VX-548, hydrocodone plus acetaminophen, or placebo for 48 hours.

At 19 time points over that 48-hour period, participants were asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10. The primary outcome was the cumulative pain experienced over the 48 hours. So, higher pain would be worse here, but longer duration of pain would also be worse.

The story of the study is really told in this chart.

Yes, those assigned to the highest dose of VX-548 had a statistically significant lower cumulative amount of pain in the 48 hours after surgery. But the picture is really worth more than the stats here. You can see that the onset of pain relief was fairly quick, and that pain relief was sustained over time. You can also see that this is not a miracle drug. Pain scores were a bit better 48 hours out, but only by about a point and a half.

Placebo isn’t really the fair comparison here; few of us treat our postabdominoplasty patients with placebo, after all. The authors do not formally compare the effect of VX-548 with that of the opioid hydrocodone, for instance. But that doesn’t stop us.

This graph, which I put together from data in the paper, shows pain control across the four randomization categories, with higher numbers indicating more (cumulative) control. While all the active agents do a bit better than placebo, VX-548 at the higher dose appears to do the best. But I should note that 5 mg of hydrocodone may not be an adequate dose for most people.

Yes, I would really have killed for an NSAID arm in this trial. Its absence, given that NSAIDs are a staple of postoperative care, is ... well, let’s just say, notable.

Although not a pain-destroying machine, VX-548 has some other things to recommend it. The receptor is really not found in the brain at all, which suggests that the drug should not carry much risk for dependency, though that has not been formally studied.

The side effects were generally mild – headache was the most common – and less prevalent than what you see even in the placebo arm.

Perhaps most notable is the fact that the rate of discontinuation of the study drug was lowest in the VX-548 arm. Patients could stop taking the pill they were assigned for any reason, ranging from perceived lack of efficacy to side effects. A low discontinuation rate indicates to me a sort of “voting with your feet” that suggests this might be a well-tolerated and reasonably effective drug.

VX-548 isn’t on the market yet; phase 3 trials are ongoing. But whether it is this particular drug or another in this class, I’m happy to see researchers trying to find new ways to target that most primeval form of suffering: pain.

Dr. Wilson is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In 133-vehicle pileup, bleeding paramedic helps while hurt

It seemed like a typical kind of day. I was out the door by 6:00 a.m., heading into work for a shift on I-35 West, my daily commute. It was still dark out. A little bit colder that morning, but nothing us Texans aren’t used to.

I was cruising down the tollway, which is separated from the main highway by a barrier. That stretch has a slight hill and turns to the left. You can’t see anything beyond the hill when you’re at the bottom.

As I made my way up, I spotted brake lights about 400 yards ahead. I eased on my brake, and next thing I knew, I was sliding.

I realized, I’m on black ice.

I was driving a 2011 Toyota FJ Cruiser and I had it all beefed up – lift tires, winch bumpers front and back. I had never had any sort of issue like that.

My ABS brakes kicked in. I slowed, but not fast enough. I saw a wall of crashed cars in front of me.

I was in the left-hand lane, so I turned my steering wheel into the center median. I could hear the whole side of my vehicle scraping against it. I managed to slow down enough to just tap the vehicle in front of me.

I looked in my passenger side-view mirror and saw headlights coming in the right lane. But this car couldn’t slow down. It crashed into the wreckage to my right.

That’s when it sunk in: There was going to be a car coming in my lane, and it might not be able to stop.

I looked in my rear-view mirror and saw headlights. Sparks flying off that center median.

I didn’t know at the time, but it was a fully loaded semi-truck traveling about 60 miles an hour.

I had a split second to think: This is it. This is how it ends. I closed my eyes.

It was the most violent impact I’ve ever experienced in my life.

I had no idea until afterward, but I had slammed into the vehicle in front of me and my SUV did a kind of 360° barrel roll over the median into the northbound lanes, landing wheels down on top of my sheared off roof rack.

Everything stopped. I opened my eyes. All my airbags had deployed. I gently tried moving my arms and legs, and they worked. I couldn’t move my left foot. It was wedged underneath the brake pedal. But I wasn’t in any pain, just very confused and disoriented. I knew I needed to get out of the vehicle.

My door was wedged shut, so I crawled out of the broken window, slipping on the black ice. I realized I had hit a Fort Worth police cruiser, now all smashed up. The driver couldn’t open his door. So, I helped him force it open, got him out of the vehicle, and checked on him. He was fine.

I had no idea how many vehicles and people were involved. I was in so much shock that the only thing I could do was immediately revert back to my training. I was the only first responder there.

I was helping people with lacerations, back and neck issues from the violent impacts. When you’re involved in a mass casualty incident like that, you have to assess which patients will be the most viable and need the most immediate attention. You have greens, yellows, reds, and then blacks – the deceased. Someone who doesn’t have a pulse and isn’t breathing, you can’t necessarily do CPR because you don’t have enough resources. You have to use your best judgment.

Meanwhile, the crashes kept coming. I found out later I was roughly vehicle No. 50 in the pileup; 83 more would follow. I heard them over and over – a crash and then screams from people in their vehicles. Each time a car hit, the entire pileup would move a couple of inches, getting more and more compacted. With that going on, I couldn’t go in there to pull people out. That scene was absolutely unsafe.

It felt like forever, but about 10 minutes later, an ambulance showed up, and I walked over to them. Because I was in my work uniform, they thought I was there on a call.

A couple fire crews came, and a firefighter yelled, “Hey, we need a backboard!” So, I grabbed a backboard from their unit and helped load up a patient. Then I heard somebody screaming, “This patient needs a stretcher!” A woman was having lumbar pain that seemed excruciating. I helped move her from the wreckage and carry her over to the stretcher. I started trying to get as many people as I could out of their cars.

Around this time, one of my supervisors showed up. He thought I was there working. But then he asked me, “Why is your face bleeding? Why do you have blood coming from your nose?” I pointed to my vehicle, and his jaw just dropped. He said, “Okay, you’re done. Go sit in my vehicle over there.”

He put a stop to my helping out, which was probably for the best. Because I actually had a concussion, a bone contusion in my foot, and a severely sprained ankle. The next day, I felt like I had gotten hit by a truck. (I had!) But when you have so much adrenaline pumping, you don’t feel pain or emotion. You don’t really feel anything.

While I was sitting in that vehicle, I called my mom to let her know I was okay. My parents were watching the news, and there was an aerial view of the accident. It was massive – a giant pile of metal stretching 200 or 300 yards. Six people had perished, more than 60 were hurt.

That night, our public information officer reached out to me about doing an interview with NBC. So, I told my story about what happened. Because of the concussion, a lot of it was a blur.

A day later, I got a call on my cell phone and someone said, “This is Tyler from Toyota. We saw the NBC interview. We wanted to let you know, don’t worry about getting a new vehicle. Just tell us what color 4Runner you want.”

My first thought was: Okay, this can’t be real. This doesn’t happen to people like me. But it turned out that it was, and they put me in a brand new vehicle.

Toyota started sending me to events like NASCAR races, putting me up in VIP suites. It was a cool experience. But it’s just surface stuff – it’s never going to erase what happened. The experience left a mark. It took me 6 months to a year to get rid of that feeling of the impact. Every time I tried to fall asleep, the whole scenario would replay in my head.

In EMS, we have a saying: “Every patient is practice for the next one.” That pileup – you can’t train for something like that. We all learned from it, so we can better prepare if anything like that happens again.

Since then, I’ve seen people die in motor vehicle collisions from a lot less than what happened to me. I’m not religious or spiritual, but I believe there must be a reason why I’m still here.

Now I see patients in traffic accidents who are very distraught even though they’re going to be okay. I tell them, “I’m sorry this happened to you. But remember, this is not the end. You are alive. And I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that doesn’t change while you’re with me.”

Trey McDaniel is a paramedic with MedStar Mobile Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seemed like a typical kind of day. I was out the door by 6:00 a.m., heading into work for a shift on I-35 West, my daily commute. It was still dark out. A little bit colder that morning, but nothing us Texans aren’t used to.

I was cruising down the tollway, which is separated from the main highway by a barrier. That stretch has a slight hill and turns to the left. You can’t see anything beyond the hill when you’re at the bottom.

As I made my way up, I spotted brake lights about 400 yards ahead. I eased on my brake, and next thing I knew, I was sliding.

I realized, I’m on black ice.

I was driving a 2011 Toyota FJ Cruiser and I had it all beefed up – lift tires, winch bumpers front and back. I had never had any sort of issue like that.

My ABS brakes kicked in. I slowed, but not fast enough. I saw a wall of crashed cars in front of me.

I was in the left-hand lane, so I turned my steering wheel into the center median. I could hear the whole side of my vehicle scraping against it. I managed to slow down enough to just tap the vehicle in front of me.

I looked in my passenger side-view mirror and saw headlights coming in the right lane. But this car couldn’t slow down. It crashed into the wreckage to my right.

That’s when it sunk in: There was going to be a car coming in my lane, and it might not be able to stop.

I looked in my rear-view mirror and saw headlights. Sparks flying off that center median.

I didn’t know at the time, but it was a fully loaded semi-truck traveling about 60 miles an hour.

I had a split second to think: This is it. This is how it ends. I closed my eyes.

It was the most violent impact I’ve ever experienced in my life.

I had no idea until afterward, but I had slammed into the vehicle in front of me and my SUV did a kind of 360° barrel roll over the median into the northbound lanes, landing wheels down on top of my sheared off roof rack.

Everything stopped. I opened my eyes. All my airbags had deployed. I gently tried moving my arms and legs, and they worked. I couldn’t move my left foot. It was wedged underneath the brake pedal. But I wasn’t in any pain, just very confused and disoriented. I knew I needed to get out of the vehicle.

My door was wedged shut, so I crawled out of the broken window, slipping on the black ice. I realized I had hit a Fort Worth police cruiser, now all smashed up. The driver couldn’t open his door. So, I helped him force it open, got him out of the vehicle, and checked on him. He was fine.

I had no idea how many vehicles and people were involved. I was in so much shock that the only thing I could do was immediately revert back to my training. I was the only first responder there.

I was helping people with lacerations, back and neck issues from the violent impacts. When you’re involved in a mass casualty incident like that, you have to assess which patients will be the most viable and need the most immediate attention. You have greens, yellows, reds, and then blacks – the deceased. Someone who doesn’t have a pulse and isn’t breathing, you can’t necessarily do CPR because you don’t have enough resources. You have to use your best judgment.

Meanwhile, the crashes kept coming. I found out later I was roughly vehicle No. 50 in the pileup; 83 more would follow. I heard them over and over – a crash and then screams from people in their vehicles. Each time a car hit, the entire pileup would move a couple of inches, getting more and more compacted. With that going on, I couldn’t go in there to pull people out. That scene was absolutely unsafe.

It felt like forever, but about 10 minutes later, an ambulance showed up, and I walked over to them. Because I was in my work uniform, they thought I was there on a call.

A couple fire crews came, and a firefighter yelled, “Hey, we need a backboard!” So, I grabbed a backboard from their unit and helped load up a patient. Then I heard somebody screaming, “This patient needs a stretcher!” A woman was having lumbar pain that seemed excruciating. I helped move her from the wreckage and carry her over to the stretcher. I started trying to get as many people as I could out of their cars.

Around this time, one of my supervisors showed up. He thought I was there working. But then he asked me, “Why is your face bleeding? Why do you have blood coming from your nose?” I pointed to my vehicle, and his jaw just dropped. He said, “Okay, you’re done. Go sit in my vehicle over there.”

He put a stop to my helping out, which was probably for the best. Because I actually had a concussion, a bone contusion in my foot, and a severely sprained ankle. The next day, I felt like I had gotten hit by a truck. (I had!) But when you have so much adrenaline pumping, you don’t feel pain or emotion. You don’t really feel anything.

While I was sitting in that vehicle, I called my mom to let her know I was okay. My parents were watching the news, and there was an aerial view of the accident. It was massive – a giant pile of metal stretching 200 or 300 yards. Six people had perished, more than 60 were hurt.

That night, our public information officer reached out to me about doing an interview with NBC. So, I told my story about what happened. Because of the concussion, a lot of it was a blur.

A day later, I got a call on my cell phone and someone said, “This is Tyler from Toyota. We saw the NBC interview. We wanted to let you know, don’t worry about getting a new vehicle. Just tell us what color 4Runner you want.”

My first thought was: Okay, this can’t be real. This doesn’t happen to people like me. But it turned out that it was, and they put me in a brand new vehicle.

Toyota started sending me to events like NASCAR races, putting me up in VIP suites. It was a cool experience. But it’s just surface stuff – it’s never going to erase what happened. The experience left a mark. It took me 6 months to a year to get rid of that feeling of the impact. Every time I tried to fall asleep, the whole scenario would replay in my head.

In EMS, we have a saying: “Every patient is practice for the next one.” That pileup – you can’t train for something like that. We all learned from it, so we can better prepare if anything like that happens again.

Since then, I’ve seen people die in motor vehicle collisions from a lot less than what happened to me. I’m not religious or spiritual, but I believe there must be a reason why I’m still here.

Now I see patients in traffic accidents who are very distraught even though they’re going to be okay. I tell them, “I’m sorry this happened to you. But remember, this is not the end. You are alive. And I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that doesn’t change while you’re with me.”

Trey McDaniel is a paramedic with MedStar Mobile Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seemed like a typical kind of day. I was out the door by 6:00 a.m., heading into work for a shift on I-35 West, my daily commute. It was still dark out. A little bit colder that morning, but nothing us Texans aren’t used to.

I was cruising down the tollway, which is separated from the main highway by a barrier. That stretch has a slight hill and turns to the left. You can’t see anything beyond the hill when you’re at the bottom.

As I made my way up, I spotted brake lights about 400 yards ahead. I eased on my brake, and next thing I knew, I was sliding.

I realized, I’m on black ice.

I was driving a 2011 Toyota FJ Cruiser and I had it all beefed up – lift tires, winch bumpers front and back. I had never had any sort of issue like that.

My ABS brakes kicked in. I slowed, but not fast enough. I saw a wall of crashed cars in front of me.

I was in the left-hand lane, so I turned my steering wheel into the center median. I could hear the whole side of my vehicle scraping against it. I managed to slow down enough to just tap the vehicle in front of me.

I looked in my passenger side-view mirror and saw headlights coming in the right lane. But this car couldn’t slow down. It crashed into the wreckage to my right.

That’s when it sunk in: There was going to be a car coming in my lane, and it might not be able to stop.

I looked in my rear-view mirror and saw headlights. Sparks flying off that center median.

I didn’t know at the time, but it was a fully loaded semi-truck traveling about 60 miles an hour.

I had a split second to think: This is it. This is how it ends. I closed my eyes.

It was the most violent impact I’ve ever experienced in my life.

I had no idea until afterward, but I had slammed into the vehicle in front of me and my SUV did a kind of 360° barrel roll over the median into the northbound lanes, landing wheels down on top of my sheared off roof rack.

Everything stopped. I opened my eyes. All my airbags had deployed. I gently tried moving my arms and legs, and they worked. I couldn’t move my left foot. It was wedged underneath the brake pedal. But I wasn’t in any pain, just very confused and disoriented. I knew I needed to get out of the vehicle.

My door was wedged shut, so I crawled out of the broken window, slipping on the black ice. I realized I had hit a Fort Worth police cruiser, now all smashed up. The driver couldn’t open his door. So, I helped him force it open, got him out of the vehicle, and checked on him. He was fine.

I had no idea how many vehicles and people were involved. I was in so much shock that the only thing I could do was immediately revert back to my training. I was the only first responder there.

I was helping people with lacerations, back and neck issues from the violent impacts. When you’re involved in a mass casualty incident like that, you have to assess which patients will be the most viable and need the most immediate attention. You have greens, yellows, reds, and then blacks – the deceased. Someone who doesn’t have a pulse and isn’t breathing, you can’t necessarily do CPR because you don’t have enough resources. You have to use your best judgment.

Meanwhile, the crashes kept coming. I found out later I was roughly vehicle No. 50 in the pileup; 83 more would follow. I heard them over and over – a crash and then screams from people in their vehicles. Each time a car hit, the entire pileup would move a couple of inches, getting more and more compacted. With that going on, I couldn’t go in there to pull people out. That scene was absolutely unsafe.

It felt like forever, but about 10 minutes later, an ambulance showed up, and I walked over to them. Because I was in my work uniform, they thought I was there on a call.

A couple fire crews came, and a firefighter yelled, “Hey, we need a backboard!” So, I grabbed a backboard from their unit and helped load up a patient. Then I heard somebody screaming, “This patient needs a stretcher!” A woman was having lumbar pain that seemed excruciating. I helped move her from the wreckage and carry her over to the stretcher. I started trying to get as many people as I could out of their cars.

Around this time, one of my supervisors showed up. He thought I was there working. But then he asked me, “Why is your face bleeding? Why do you have blood coming from your nose?” I pointed to my vehicle, and his jaw just dropped. He said, “Okay, you’re done. Go sit in my vehicle over there.”

He put a stop to my helping out, which was probably for the best. Because I actually had a concussion, a bone contusion in my foot, and a severely sprained ankle. The next day, I felt like I had gotten hit by a truck. (I had!) But when you have so much adrenaline pumping, you don’t feel pain or emotion. You don’t really feel anything.

While I was sitting in that vehicle, I called my mom to let her know I was okay. My parents were watching the news, and there was an aerial view of the accident. It was massive – a giant pile of metal stretching 200 or 300 yards. Six people had perished, more than 60 were hurt.

That night, our public information officer reached out to me about doing an interview with NBC. So, I told my story about what happened. Because of the concussion, a lot of it was a blur.

A day later, I got a call on my cell phone and someone said, “This is Tyler from Toyota. We saw the NBC interview. We wanted to let you know, don’t worry about getting a new vehicle. Just tell us what color 4Runner you want.”

My first thought was: Okay, this can’t be real. This doesn’t happen to people like me. But it turned out that it was, and they put me in a brand new vehicle.

Toyota started sending me to events like NASCAR races, putting me up in VIP suites. It was a cool experience. But it’s just surface stuff – it’s never going to erase what happened. The experience left a mark. It took me 6 months to a year to get rid of that feeling of the impact. Every time I tried to fall asleep, the whole scenario would replay in my head.

In EMS, we have a saying: “Every patient is practice for the next one.” That pileup – you can’t train for something like that. We all learned from it, so we can better prepare if anything like that happens again.

Since then, I’ve seen people die in motor vehicle collisions from a lot less than what happened to me. I’m not religious or spiritual, but I believe there must be a reason why I’m still here.

Now I see patients in traffic accidents who are very distraught even though they’re going to be okay. I tell them, “I’m sorry this happened to you. But remember, this is not the end. You are alive. And I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that doesn’t change while you’re with me.”

Trey McDaniel is a paramedic with MedStar Mobile Healthcare in Fort Worth, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity: Don’t separate mental health from physical health

“The patient is ready,” the medical assistant informs you while handing you the chart. The chart reads: “Chief complaint: Weight gain/Discuss weight loss options.” You note the normal vital signs other than an increased BMI to 34 from 4 months ago. You knock on the exam room door with your plan half-formulated.

“Come in,” the patient says, almost too softly for you to hear. Shock overtakes you as you enter the room and see something you never imagined. The patient is holding their disconnected head in their lap as they say, “Nice to see you, Doc. I want to do something about my weight.”

You’re baffled at how they are speaking with a disconnected head. Of course, this outlandish patient scenario isn’t real. Or is it?

Patients with mental health concerns don’t literally present with their head disconnected from their bodies. Too often, mental health is treated as separate from physical health, especially regarding weight management and obesity. However, studies have shown an association between mental health and obesity. In this pivotal time of pharmacologic innovation in obesity care, we must also ensure that we effectively address the mental health of our patients with obesity.

Screening

Mental health conditions can look different for everyone. It can be hard to diagnose a mental health condition without validated screening. For example, depression is one of the most common mental health disorders. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends depression screening in all adults.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is one screening tool that can alert doctors and clinicians to potential depression. Patients with obesity have higher rates of depression and other mental health conditions. It’s even more critical to screen for depression and other mental health disorders when prescribing these new medications, given recent reports of suicidal ideation with certain antiobesity medications.

Stigma

Mental health–related stigma can trigger shame and prevent patients from seeking psychological help. Furthermore, compounded stigma in patients with larger bodies (weight bias) and from marginalized communities such as the Black community (racial discrimination) add more barriers to seeking mental health care. When patients seek care for mental health conditions, they may feel more comfortable seeing a primary care physician or other clinician than a mental health professional. Therefore, all physicians and clinicians are integral in normalizing mental health care. Instead of treating mental health as separate from physical health, discussing the bidirectional relationship between mental health conditions and physiologic diseases can help patients understand that having a mental health condition isn’t a choice and facilitate openness to multiple treatment options to improve their quality of life.

Support

Addressing mental health effectively often requires multiple layers of patient support. Support can come from loved ones or community groups. But for severe stress and other mental health conditions, treatment with psychotherapy or psychiatric medications is essential. Unfortunately, even if a patient is willing to see a mental health professional, availability or access may be a challenge. Therefore, other clinicians may have to step in and serve as a bridge to mental health care. It’s also essential to ensure that patients are aware of crisis support lines and online resources for mental health care.

Stress

Having a high level of stress can be harmful physically and can also worsen mental health conditions. Additionally, it can contribute to a higher risk for obesity and can trigger emotional eating. Chronic stress has become so common in society that patients often underestimate how much stress they are under. Assessments like the Holmes-Rahe Stress Inventory can help patients identify and quantify potential stressors. While some stressors are uncontrollable, such as social determinants of health (SDOH), addressing controllable stressors and improving coping mechanisms is possible. For instance, mindfulness and breathwork are easy to follow and relatively accessible for most patients.

Social determinants of health

For a treatment plan to be maximally impactful, we must incorporate SDOH in clinical care. SDOH includes financial instability, safe neighborhoods, and more, and can significantly influence an ideal treatment plan. Furthermore, a high SDOH burden can negatively affect mental health and obesity rates. It’s helpful to incorporate patients’ SDOH burden into treatment planning. Learn how to take action on SDOH.

Empowerment

Patients who address their mental health have taken a courageous step toward health and healing. As mentioned, they may experience gaps in care while awaiting connection to the next steps of their journey, such as starting care with a mental health professional or waiting for a medication to take effect. All clinicians can empower patients about their weight by informing them that:

Food may affect their mood. Studies show that certain foods and eating patterns are associated with high levels of depression and anxiety. Limiting processed foods and increasing fruits, vegetables, and foods high in vitamin D, C, and other nutrients is helpful. Everyone is different, so encourage patients to pay attention to how food uniquely affects their mood by keeping a food/feeling log for 1-3 days.

Move more. Increased physical activity can improve mental health.

Get outdoors. Time in nature is associated with better mental health. Spending as little as 10 minutes outside can be beneficial. It’s important to be aware that SDOH factors such as unsafe environments or limited outdoor access may make this difficult for some patients.

Positive stress-relieving activities. Each person has their own way of reducing stress. It is helpful to remind patients of unhealthy stress relievers such as overeating, drinking alcohol, and smoking, and encourage them to replace those with positive stress relievers.

Spiritual well-being. Spirituality is often overlooked in health care. But studies have shown that incorporating a person’s spirituality may have positive health benefits.

It’s time to stop disconnecting mental health from physical health. Each clinician plays a vital role in treating the whole person. Just as you wouldn’t let a patient with a disconnected head leave the office without addressing it, let’s not leave mental health out when addressing our patients’ weight concerns.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is an integrative obesity specialist focused on individualized solutions for emotional and biological overeating. Connect with her at www.embraceyouweightloss.com or on Instagram @embraceyoumd. Her bestselling book, “Embrace You: Your Guide to Transforming Weight Loss Misconceptions Into Lifelong Wellness,” (Baltimore: Purposely Created Publishing Group, 2019) was Healthline.com’s Best Overall Weight Loss Book of 2022 and one of Livestrong.com’s 8 Best Weight-Loss Books to Read in 2022.

Dr. Gonsahn-Bollie is CEO and Lead Physician, Embrace You Weight and Wellness, Telehealth & Virtual Counseling. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“The patient is ready,” the medical assistant informs you while handing you the chart. The chart reads: “Chief complaint: Weight gain/Discuss weight loss options.” You note the normal vital signs other than an increased BMI to 34 from 4 months ago. You knock on the exam room door with your plan half-formulated.

“Come in,” the patient says, almost too softly for you to hear. Shock overtakes you as you enter the room and see something you never imagined. The patient is holding their disconnected head in their lap as they say, “Nice to see you, Doc. I want to do something about my weight.”

You’re baffled at how they are speaking with a disconnected head. Of course, this outlandish patient scenario isn’t real. Or is it?