User login

The Patient Portal That Patients Can’t Navigate

Beth Cavanaugh, 79, was starting a new medication when she ran into a modern hurdle: Her doctor’s office required all follow–up questions, even those about side effects of the drug, to go through the patient portal.

Cavanaugh said she did not know how to set up or use the system.

“I tried to explain that, but the receptionist said that was the only way to contact the doctor. I felt lost,” said Cavanaugh, a retired psychotherapist near Albany, New York.

Cavanaugh is far from alone. Many older people balk at the idea of communicating with their physicians over the internet. They may have limited digital skills, have physical challenges, or simply prefer human connection.

As medicine leans harder on electronic portals and telehealth, these patients are finding themselves shut out of their own care. Experts warn this approach deepens inequities in access to care and can worsen health outcomes.

Clinicians should “offer options for various types of communication, such as phone calls or texts, because whenever an older adult — or anyone, for that matter — is given a choice, they feel more empowered and more committed to their care,” said Susan Wehry, MD, associate clinical professor at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine in Biddeford, Maine.

Tech Support

Use of medical communication tools varies among older adults. One study in JAMA Network Open found nearly two thirds of those older than 65 years who filled out surveys via phone or internet had used a patient portal, while a little under half used telehealth, and only 44% used a medical health application.

Older patients tend to fall into two camps, said Neela Patel, MD, MPH, CMD, chief of the Division of Geriatrics and Supportive Care at the UT Health San Antonio.

Her patients “are at two extremes of the spectrum — some technologically savvy and others with limited digital literacy or limited or no access to the Internet,” Patel, who is also the vice chair of the Health Systems Innovations and Technology Committee of the American Geriatric Society, said.

Patel’s practice has dedicated staff to help patients master certain technologies. For example, a pharmacist teaches patients how to use a glucometer and a blood pressure cuff. Other staff teach them how to use smartphone apps that track blood pressure or glucose.

She usually sees patients in person before offering telehealth as an option, ensuring the person has “enough digital literacy to utilize them and that the patient can see and hear the visit.”

If technological limitations impede a telehealth appointment, clinicians can help patients navigate their computer screen. Patel recounted the story of an older woman who was unable to come to the clinic in person, so had a telehealth visit instead.

“She had trouble hearing me, so I asked her to share her screen with me. I walked her through how to do that. Then I showed her where the ‘volume’ button was located. It turns out her volume was at zero,” Patel said. “Once that was adjusted, we were able to proceed with the appointment.”

Educating older adults on how to use health technology does not have to fall upon clinicians and their staff, according to Wehry. She routinely refers her patients to community resources to help them develop digital skills.

Local libraries and community centers often offer digital education. Some retirement communities and assisted living facilities also have tech support personnel or classes available to residents.

Wehry refers some of her patients to the National Digital Equity Center which teaches older adults how to hold a telehealth visit.

Roughly 90% of Patel’s patients are signed up for the patient portal, but they may not be operating the technology, she said. She advises these patients to ask their children or caregivers for help as appropriate.

Teaching patients to use the communication technology early on can also be helpful in other ways. If patients who have been technologically proficient start having difficulty, “it’s a clue there may be cognitive changes, and we follow up on those,” Patel said.

Additional resources to help older adults develop digital competence include Cyber Seniors, Older Adults Technology Services, AARP, AARP Find Digital Courses, Area Agencies on Aging, and Senior Navigator.

Human Touch

Some older adults may simply want a more traditional means of communicating with their clinician. A review of 29 papers, encompassing over 6200 adults older than 60 years, identified several domains affecting the adoption of healthcare technology, two of which were resistance to new technology and having family or friends that could help with.

Wehry said many older adults “don’t resist this technology because they’re unable to figure out how to use it. Instead, they see the technology as too impersonal.”

One study found many older adults fear technologies may end up replacing face-to-face contact.

“I’m beginning to encourage primary care providers to take a step back and refocus on the doctor-patient relationship. When communication is limited to the technological approach, it can erode trust in that relationship,” Wehry said.

The American Medical Association recommends clinicians “provide a method other than electronic communication for patients who are without technological proficiency or access.”

Some busy clinicians might be concerned phone calls will be too time-consuming, Wehry said. Patients should be informed of hours of phone availability, how much time is allotted to calls, and how many days or hours a response may take. Clinicians might also use tools that allow patients to use their cell phone to text their practice with medical questions.

Cavanaugh ended up finding technological help from a professional organizer whom she hired to help rearrange her closets.

“She’s knowledgeable and patient, and she’s helping me with the portal,” she said. “If I hadn’t serendipitously found the organizer, I’d still be struggling and unable to access proper medical care.”

Wehry and Patel disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Beth Cavanaugh, 79, was starting a new medication when she ran into a modern hurdle: Her doctor’s office required all follow–up questions, even those about side effects of the drug, to go through the patient portal.

Cavanaugh said she did not know how to set up or use the system.

“I tried to explain that, but the receptionist said that was the only way to contact the doctor. I felt lost,” said Cavanaugh, a retired psychotherapist near Albany, New York.

Cavanaugh is far from alone. Many older people balk at the idea of communicating with their physicians over the internet. They may have limited digital skills, have physical challenges, or simply prefer human connection.

As medicine leans harder on electronic portals and telehealth, these patients are finding themselves shut out of their own care. Experts warn this approach deepens inequities in access to care and can worsen health outcomes.

Clinicians should “offer options for various types of communication, such as phone calls or texts, because whenever an older adult — or anyone, for that matter — is given a choice, they feel more empowered and more committed to their care,” said Susan Wehry, MD, associate clinical professor at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine in Biddeford, Maine.

Tech Support

Use of medical communication tools varies among older adults. One study in JAMA Network Open found nearly two thirds of those older than 65 years who filled out surveys via phone or internet had used a patient portal, while a little under half used telehealth, and only 44% used a medical health application.

Older patients tend to fall into two camps, said Neela Patel, MD, MPH, CMD, chief of the Division of Geriatrics and Supportive Care at the UT Health San Antonio.

Her patients “are at two extremes of the spectrum — some technologically savvy and others with limited digital literacy or limited or no access to the Internet,” Patel, who is also the vice chair of the Health Systems Innovations and Technology Committee of the American Geriatric Society, said.

Patel’s practice has dedicated staff to help patients master certain technologies. For example, a pharmacist teaches patients how to use a glucometer and a blood pressure cuff. Other staff teach them how to use smartphone apps that track blood pressure or glucose.

She usually sees patients in person before offering telehealth as an option, ensuring the person has “enough digital literacy to utilize them and that the patient can see and hear the visit.”

If technological limitations impede a telehealth appointment, clinicians can help patients navigate their computer screen. Patel recounted the story of an older woman who was unable to come to the clinic in person, so had a telehealth visit instead.

“She had trouble hearing me, so I asked her to share her screen with me. I walked her through how to do that. Then I showed her where the ‘volume’ button was located. It turns out her volume was at zero,” Patel said. “Once that was adjusted, we were able to proceed with the appointment.”

Educating older adults on how to use health technology does not have to fall upon clinicians and their staff, according to Wehry. She routinely refers her patients to community resources to help them develop digital skills.

Local libraries and community centers often offer digital education. Some retirement communities and assisted living facilities also have tech support personnel or classes available to residents.

Wehry refers some of her patients to the National Digital Equity Center which teaches older adults how to hold a telehealth visit.

Roughly 90% of Patel’s patients are signed up for the patient portal, but they may not be operating the technology, she said. She advises these patients to ask their children or caregivers for help as appropriate.

Teaching patients to use the communication technology early on can also be helpful in other ways. If patients who have been technologically proficient start having difficulty, “it’s a clue there may be cognitive changes, and we follow up on those,” Patel said.

Additional resources to help older adults develop digital competence include Cyber Seniors, Older Adults Technology Services, AARP, AARP Find Digital Courses, Area Agencies on Aging, and Senior Navigator.

Human Touch

Some older adults may simply want a more traditional means of communicating with their clinician. A review of 29 papers, encompassing over 6200 adults older than 60 years, identified several domains affecting the adoption of healthcare technology, two of which were resistance to new technology and having family or friends that could help with.

Wehry said many older adults “don’t resist this technology because they’re unable to figure out how to use it. Instead, they see the technology as too impersonal.”

One study found many older adults fear technologies may end up replacing face-to-face contact.

“I’m beginning to encourage primary care providers to take a step back and refocus on the doctor-patient relationship. When communication is limited to the technological approach, it can erode trust in that relationship,” Wehry said.

The American Medical Association recommends clinicians “provide a method other than electronic communication for patients who are without technological proficiency or access.”

Some busy clinicians might be concerned phone calls will be too time-consuming, Wehry said. Patients should be informed of hours of phone availability, how much time is allotted to calls, and how many days or hours a response may take. Clinicians might also use tools that allow patients to use their cell phone to text their practice with medical questions.

Cavanaugh ended up finding technological help from a professional organizer whom she hired to help rearrange her closets.

“She’s knowledgeable and patient, and she’s helping me with the portal,” she said. “If I hadn’t serendipitously found the organizer, I’d still be struggling and unable to access proper medical care.”

Wehry and Patel disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Beth Cavanaugh, 79, was starting a new medication when she ran into a modern hurdle: Her doctor’s office required all follow–up questions, even those about side effects of the drug, to go through the patient portal.

Cavanaugh said she did not know how to set up or use the system.

“I tried to explain that, but the receptionist said that was the only way to contact the doctor. I felt lost,” said Cavanaugh, a retired psychotherapist near Albany, New York.

Cavanaugh is far from alone. Many older people balk at the idea of communicating with their physicians over the internet. They may have limited digital skills, have physical challenges, or simply prefer human connection.

As medicine leans harder on electronic portals and telehealth, these patients are finding themselves shut out of their own care. Experts warn this approach deepens inequities in access to care and can worsen health outcomes.

Clinicians should “offer options for various types of communication, such as phone calls or texts, because whenever an older adult — or anyone, for that matter — is given a choice, they feel more empowered and more committed to their care,” said Susan Wehry, MD, associate clinical professor at the University of New England College of Osteopathic Medicine in Biddeford, Maine.

Tech Support

Use of medical communication tools varies among older adults. One study in JAMA Network Open found nearly two thirds of those older than 65 years who filled out surveys via phone or internet had used a patient portal, while a little under half used telehealth, and only 44% used a medical health application.

Older patients tend to fall into two camps, said Neela Patel, MD, MPH, CMD, chief of the Division of Geriatrics and Supportive Care at the UT Health San Antonio.

Her patients “are at two extremes of the spectrum — some technologically savvy and others with limited digital literacy or limited or no access to the Internet,” Patel, who is also the vice chair of the Health Systems Innovations and Technology Committee of the American Geriatric Society, said.

Patel’s practice has dedicated staff to help patients master certain technologies. For example, a pharmacist teaches patients how to use a glucometer and a blood pressure cuff. Other staff teach them how to use smartphone apps that track blood pressure or glucose.

She usually sees patients in person before offering telehealth as an option, ensuring the person has “enough digital literacy to utilize them and that the patient can see and hear the visit.”

If technological limitations impede a telehealth appointment, clinicians can help patients navigate their computer screen. Patel recounted the story of an older woman who was unable to come to the clinic in person, so had a telehealth visit instead.

“She had trouble hearing me, so I asked her to share her screen with me. I walked her through how to do that. Then I showed her where the ‘volume’ button was located. It turns out her volume was at zero,” Patel said. “Once that was adjusted, we were able to proceed with the appointment.”

Educating older adults on how to use health technology does not have to fall upon clinicians and their staff, according to Wehry. She routinely refers her patients to community resources to help them develop digital skills.

Local libraries and community centers often offer digital education. Some retirement communities and assisted living facilities also have tech support personnel or classes available to residents.

Wehry refers some of her patients to the National Digital Equity Center which teaches older adults how to hold a telehealth visit.

Roughly 90% of Patel’s patients are signed up for the patient portal, but they may not be operating the technology, she said. She advises these patients to ask their children or caregivers for help as appropriate.

Teaching patients to use the communication technology early on can also be helpful in other ways. If patients who have been technologically proficient start having difficulty, “it’s a clue there may be cognitive changes, and we follow up on those,” Patel said.

Additional resources to help older adults develop digital competence include Cyber Seniors, Older Adults Technology Services, AARP, AARP Find Digital Courses, Area Agencies on Aging, and Senior Navigator.

Human Touch

Some older adults may simply want a more traditional means of communicating with their clinician. A review of 29 papers, encompassing over 6200 adults older than 60 years, identified several domains affecting the adoption of healthcare technology, two of which were resistance to new technology and having family or friends that could help with.

Wehry said many older adults “don’t resist this technology because they’re unable to figure out how to use it. Instead, they see the technology as too impersonal.”

One study found many older adults fear technologies may end up replacing face-to-face contact.

“I’m beginning to encourage primary care providers to take a step back and refocus on the doctor-patient relationship. When communication is limited to the technological approach, it can erode trust in that relationship,” Wehry said.

The American Medical Association recommends clinicians “provide a method other than electronic communication for patients who are without technological proficiency or access.”

Some busy clinicians might be concerned phone calls will be too time-consuming, Wehry said. Patients should be informed of hours of phone availability, how much time is allotted to calls, and how many days or hours a response may take. Clinicians might also use tools that allow patients to use their cell phone to text their practice with medical questions.

Cavanaugh ended up finding technological help from a professional organizer whom she hired to help rearrange her closets.

“She’s knowledgeable and patient, and she’s helping me with the portal,” she said. “If I hadn’t serendipitously found the organizer, I’d still be struggling and unable to access proper medical care.”

Wehry and Patel disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Nutrition, Drugs, or Bariatric Surgery: What’s the Best Approach for Sustained Weight Loss?

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

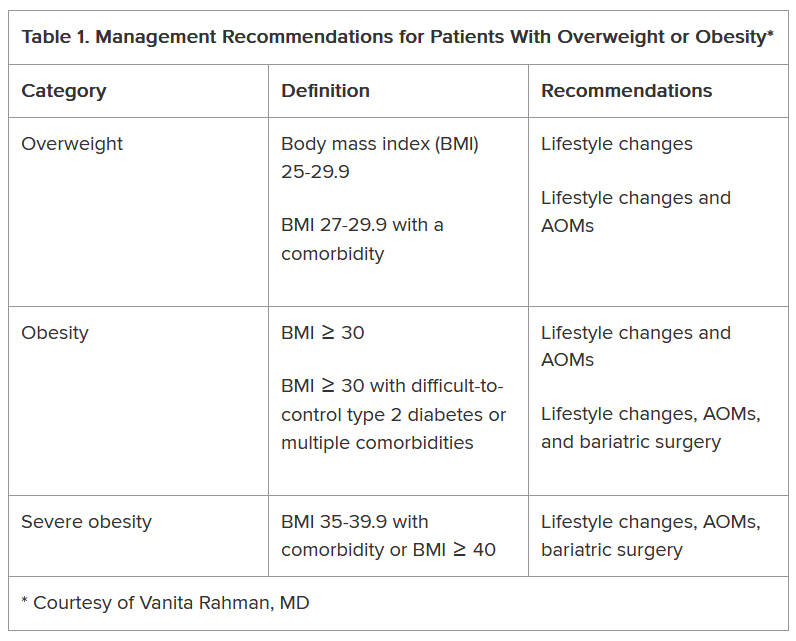

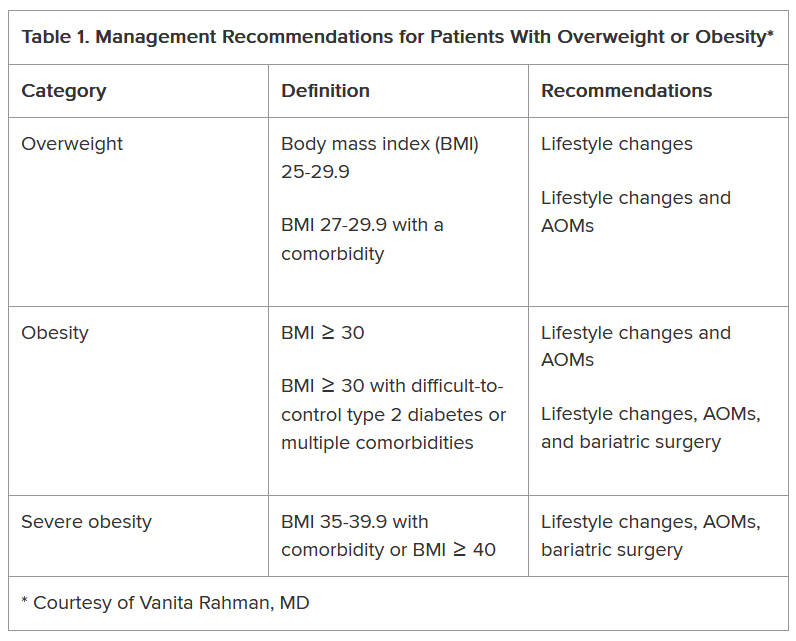

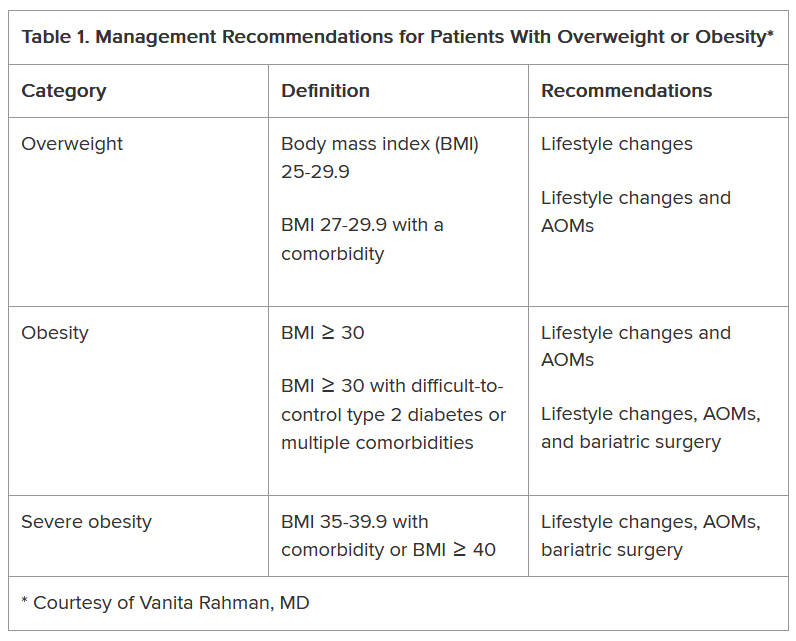

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

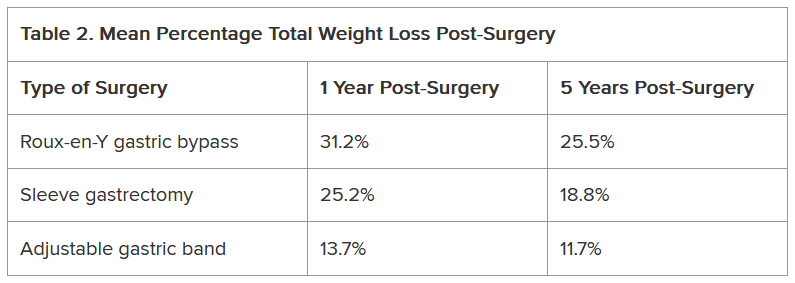

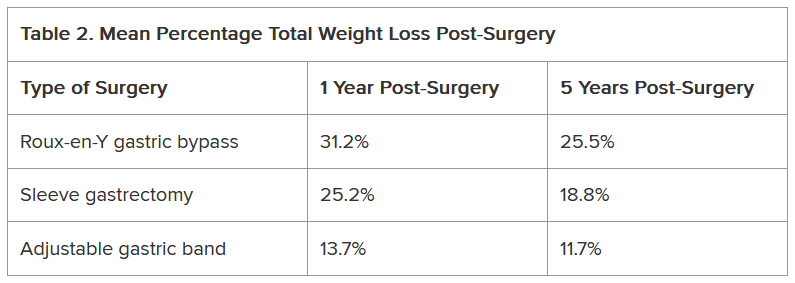

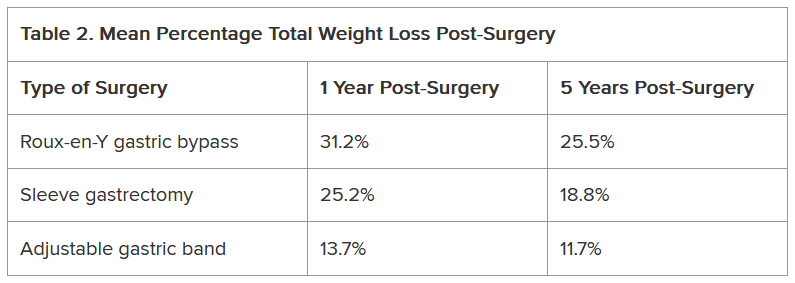

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Given that more than 100 million US adults have obesity, including 22 million with severe obesity, physicians regularly see patients with the condition in their practices.

Fortunately, doctors have more tools than ever to help their patients. But the question remains: Which method is the safest and most effective? Is it diet and lifestyle changes, one of the recently approved anti-obesity medications (AOMs), bariatric surgery, or a combination approach?

There are no head-to-head trials comparing these three approaches, said Vanita Rahman, MD, clinic director of the Barnard Medical Center, Washington, DC, at the International Conference on Nutrition in Medicine, sponsored by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Instead, doctors must evaluate the merits and drawbacks of each intervention and decide with their patients which treatment is best for them, she told Medscape Medical News. When she sees patients, Rahman shares the pertinent research with them, so they are able to make an informed choice.

Looking at the Options

In her presentation at the conference, Rahman summarized the guidelines issued by the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology/The Obesity Society for Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines For Medical Care of Patients with Obesity, including lifestyle changes, AOMs, and bariatric surgery (Table 1).

As shown, the current clinical guidelines offer recommendations that consider such factors as the patient’s BMI and presence of one or more comorbidities. Generally, they begin with lifestyle changes for people with overweight, the possibility of an AOM for those with obesity, and bariatric surgery as an option for those with severe obesity-related complications.

“In obesity, we traditionally thought the process was ‘either-or’ — either lifestyle or surgery or medication — and somehow lifestyle is better,” Sheethal Reddy, PhD, a psychologist at the Bariatric Center at Emory University Hospital Midtown, Atlanta, told Medscape Medical News.

Now physicians often use a combination of methods, but lifestyle is foundational to all of them, she said.

“If you don’t make lifestyle changes, none of the approaches will ultimately be effective,” said Reddy, who also is an assistant professor in the Division of General and GI Surgery at Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta.

Lifestyle changes don’t just involve diet and nutrition but include physical exercise.

“Being sedentary affects everything — sleep quality, appetite regulation, and metabolism. Without sufficient exercise, the body isn’t functioning well enough to have a healthy metabolism,” Reddy said.

How Durable Are the Interventions?

Although bariatric surgery has demonstrated effectiveness in helping patients lose weight, many of them regain some or most of it, Rahman said.

A systematic review and meta-analysis found weight regain in 49% of patients who underwent bariatric surgery patients, with the highest prevalence after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Another study of approximately 45,000 patients who underwent bariatric surgery found differences not only in the percentage of total weight loss among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric band procedures but also in how much of that weight stayed off between 1 and 5 years following the procedure (Table 2).

Weight regain also is a risk with AOMs, if they’re discontinued.

The STEP 1 trial tested the effectiveness of semaglutide — a glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist — as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention for weight loss in patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity but not diabetes. Mean weight loss with semaglutide was 17.3% but that figure dropped 11.6 percentage points after treatment was discontinued.

Other studies also have found that patients regain weight after GLP-1 discontinuation.

Tirzepatide, a GLP-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) combination, has shown efficacy with weight reduction, but patients experienced some weight regain upon discontinuation. In one study, patients experienced a mean weight loss of 20.9% after 36 weeks of tirzepatide. In the study’s subsequent 52-week double-blind, placebo-controlled period, patients who stopped taking the medication experienced a weight regain of 14%, whereas those who remained on the medication lost an additional 5.5% of weight.

GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications do not address the factors that contribute to overweight and obesity, Rahman said. “They simply suppress the appetite; therefore, weight gain occurs after stopping them.”

Patients may stop taking anti-obesity drugs for a variety of reasons, including side effects. Rahman noted that the common side effects include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, whereas rare side effects include gastroparesis, gallbladder and biliary disease, thyroid cancer, and suicidal thoughts. GLP-1 and GLP-1/GIP medications also carry a risk for non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, she said.

Moreover, health insurance does not always cover these medications, which likely affects patient access to the drugs and compliance rates.

“Given the side effects and frequent lack of insurance coverage, significant questions remain about long-term safety and feasibility of these agents,” Rahman said.

What About Nutritional Approaches?

The lifestyle interventions in the semaglutide and tirzepatide studies included 500 kcal/d deficit diets, which is difficult for people to maintain, noted Rahman, who is the author of the book Simply Plant Based: Fabulous Food for a Healthy Life.

Additionally, bariatric surgery has been associated with long-term micronutrient deficiencies, including deficiencies in vitamins A, D, E, K, B1, and B12, as well as folate, iron, zinc, copper, selenium, and calcium, she said.

The best approach to food from a patient compliance standpoint and to avoid nutrient deficiencies is a whole-food, plant-based diet, Rahman said. She advocates this nutritional approach, along with physical activity, for patients regardless of whether they’ve selected lifestyle intervention alone or combined with an AOM or bariatric surgery to address obesity.

Rahman cited a 5-year heart disease study comparing an intensive lifestyle program involving a vegetarian diet, aerobic exercise, stress management training, smoking cessation, and group psychosocial support to treatment as usual. Patients in the lifestyle group lost 10.9 kg at 1 year and sustained weight loss of 5.8 kg at 5 years, whereas weight in the control group remained relatively unchanged from baseline.

She also pointed to the findings of a study of patients with obesity or with overweight and at least one comorbidity that compared standard care with a low-fat, whole-food, plant-based diet with vitamin B12 supplementation. At 6 months, mean BMI reduction was greater in the intervention group than the standard care group (−4.4 vs −0.4).

In her practice, Rahman has seen the benefits of a whole-food, plant-based diet for patients with obesity.

If people are committed to this type of dietary approach and are given the tools and resources to do it effectively, “their thinking changes, their taste buds change, and they grow to enjoy this new way of eating,” she said. “They see results, and it’s a lifestyle that can be sustained long-term.”

Addressing Drivers of Weight Gain

Patients also need help addressing the various factors that may contribute to overweight and obesity, including overconsumption of ultra-processed foods, substandard nutritional quality of restaurant foods, increasing portion sizes, distraction during eating, emotional eating, late-night eating, and cultural/traditional values surrounding food, Rahman noted.

Supatra Tovar, PsyD, RD, a clinical psychologist with a practice in Pasadena, California, agreed that identifying the reasons for weight gain is critical for treatment.

“If you’re not addressing underlying issues, such as a person’s relationship with food, behaviors around food, the tendency to mindlessly eat or emotionally eat or eat to seek comfort, the person’s weight problems won’t ultimately be fully solved by any of the three approaches — dieting, medications, or bariatric surgery,” she said.

Some of her patients “engage in extreme dieting and deprivation, and many who use medications or have had bariatric surgery hardly eat and often develop nutritional deficiencies,” said Tovar, author of the book Deprogram Diet Culture: Rethink Your Relationship with Food, Heal Your Mind, and Live a Diet-Free Life.

The key to healthy and sustained weight loss is to “become attuned to the body’s signals, learn how to honor hunger, stop eating when satisfied, and eat more healthful foods, such as fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins — especially plant-based proteins — and the body gives signals that this is what it wants,” she said.

Tovar doesn’t give her clients a specific diet or set of portions.

“I teach them to listen to their bodies,” she said. “They’ve lost significant amounts of weight and continued to keep it off because they’ve done this kind of work.”

When Lifestyle Changes Aren’t Enough

For many patients, lifestyle interventions are insufficient to address the degree of overweight and obesity and common comorbidities, said W. Timothy Garvey, MD, associate director and professor, Department of Nutrition Sciences, School of Health Professions, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

“Of course, nutritional approaches are very important, not only for weight but also for general health-related reasons,” said Garvey, lead author of the 2016 American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists obesity guidelines. “We’ve seen that the Mediterranean and some plant-based diets can prevent progression from prediabetes to diabetes and improve other parameters that reflect metabolic health.”

However, it’s “not common that patients can follow these diets, lose weight, and keep it off,” Garvey cautioned. Up to 50% of weight that’s lost through lifestyle changes is typically regained by 1-year follow-up, with almost all remaining lost weight subsequently regained in the majority of individuals because the person “has to fight against pathophysiological process that drive weight regain,” he noted.

Weight-loss medications can address these pathophysiologic processes by “addressing interactions of satiety hormones with feeding centers in the brain, suppressing the appetite, and making it easier for patients to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet.”

Garvey views the weight-loss medications in the same light as drugs for diabetes and hypertension, in that people need to keep taking them to sustain the benefit.

There’s still a role for bariatric surgery because not everyone can tolerate the AOMs or achieve sufficient weight loss.

“Patients with very high BMI who have trouble ambulating might benefit from a combination of bariatric surgery and medication,” Garvey said.

While some side effects are associated with AOMs, being an “alarmist” about them can be detrimental to patients, he warned.

Rahman and Tovar are authors of books about weight loss. Reddy reported no relevant financial relationships. Garvey is a consultant on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Fractyl Health, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Inogen, Zealand, Allurion, Carmot/Roche, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine, Keros Therapeutics, and Regeneron. He is the site principal investigator for multi-centered clinical trials sponsored by his university and funded by Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Epitomee, Neurovalens, and Pfizer. He serves as a consultant on the advisory board for the nonprofit Milken Foundation and is a member of the Data Monitoring Committee for phase 3 clinical trials conducted by Boehringer-Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Are Patients On GLP-1s Getting the Right Nutrients?

As the use of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) continues to exponentially expand obesity treatment, concerns have arisen regarding their impact on nutrition in people who take them.

While the medications’ dampening effects on appetite result in an average weight reduction ≥ 15%, they also pose a risk for malnutrition.

“It’s important to eat a balanced diet when taking these medications,” Deena Adimoolam, MD, an endocrinologist based in New York City and a member of the national advisory committees for the Endocrine Society and the American Diabetes Association, said in an interview.

The decreased caloric intake resulting from the use of GLP-1 RAs makes it essential for patients to consume nutrient-dense foods. Clinicians can help patients achieve a healthy diet by anticipating nutrition problems, advising them on recommended target ranges of nutrient intake, and referring them for appropriate counseling.

Where to Begin

The task begins with “setting the right expectations before the patient starts treatment,” said Scott Isaacs, MD, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

To that end, it’s important to explain to patients how the medications affect appetite and how to adapt. GLP-1 RAs don’t completely turn off the appetite, and the effect at the beginning will likely be very mild, Isaacs said in an interview.

Some patients don’t notice a change for 2-3 months, although others see an effect sooner.

“Typically, people will notice that the main impact is on satiation, meaning they’ll fill up more quickly,” said Isaacs, who is an adjunct associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. “It’s important to tell them to stop eating when they feel full because eating when full can increase the side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.”

A review article, written by lead author Jaime Almandoz, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, in Obesity offers a “5 A’s model” as a guide on how to begin discussing overweight or obesity with patients. This involves asking for permission to discuss weight and asking about food and vitamin/supplement intake; assessing the patient’s medical history and root causes of obesity, and conducting a physical examination; advising the patient regarding treatment options and reasonable expectations; agreeing on treatment and lifestyle goals; and assisting the patient to address challenges, referring them as needed to for additional support (eg, a dietitian), as well as arranging for follow-up.

Impact of GLP-1 RAs on Food Preferences

Besides reducing hunger and increasing satiety, GLP-1 RAs may affect food preferences, according to a research review published in The International Journal of Obesity. It cites a 2014 study that found that people taking GLP-1 RAs displayed decreased neuronal responses to images of food measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in the areas of brain associated with appetite and reward. This might affect taste preferences and food intake.

Additionally, a 2023 study suggested that during the weight-loss phase of treatment (as opposed to the maintenance phase), patients may experience reduced cravings for dairy and starchy food, less desire to eat salty or spicy foods, and less difficulty controlling eating and resisting cravings.

“Altered food preferences, decreased food cravings, and reduced food intake may contribute to long-term weight loss,” according to the research review. Tailored treatments focusing on the weight maintenance phase are needed, the authors wrote.

Are Patients Vulnerable to Malnutrition?

A recent review found that total caloric intake was reduced by 16%-39% in patients taking a GLP-1 RA or dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA, but few studies evaluated the composition of these patients’ diets. Research that examines the qualitative changes in macronutrient and micronutrient intake of patients on these medications is needed, the authors wrote.

They outlined several nutritional concerns, including whether GLP-1 RA or GIP/ GLP-1 RA use could result in protein intake insufficient for maintaining muscle strength, mass, and function or in inadequate dietary quality (ie, poor intake of micronutrients, fiber, and fluid).

“Although we don’t necessarily see ‘malnutrition’ in our practice, we do see patients who lose too much weight after months and months of treatment, patients who aren’t hungry and don’t eat all day and have one big meal at the end of the day because they don’t feel like eating, and people who continue to eat unhealthy foods,” Isaacs said.

Some patients, however, have medical histories placing them at a greater risk for malnutrition. “Identification of these individuals may help prevent more serious nutritional and medical complications that might occur with decreased food intake associated with AOMs [anti-obesity medications],” Almandoz and colleagues noted in their review.

What Should Patients Eat?

Nutritional needs vary based on the patient’s age, sex, body weight, physical activity, and other factors, Almandoz and colleagues wrote. For this reason, energy intake during weight loss should be “personalized.”

The authors also recommended specific sources of the various dietary components and noted red flags signaling potential deficiencies

Nutritional needs vary based on the degree of appetite suppression in the patient, Adimoolam said. “I recommend at least two servings of fruits and vegetables daily, and drinking plenty of water throughout the day,” she added.

Protein in particular is a “key macronutrient,” and insufficient intake can lead to a variety of adverse effects, including sarcopenia — which is already a concern in individuals being treated with GLP-1 RAs. Meal replacement products (eg, shakes or bars) can supplement diets to help meet protein needs, especially if appetite is significantly reduced.

“There are definitely concerns for sarcopenia, so we have our patients taking these drugs try to eat healthy lean proteins – 100 g/d — and exercise,” Isaacs said. Exercise, including resistance training, not only improves muscle mass but also potentiates the effects of the GLP-1 RAs in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Adequate hydration is essential for patients taking GLP-1 RAs. “One of the commonly described side effects is fatigue, but there’s no biological reason why these medications should cause fatigue. My opinion is that these patients are dehydrated, and that may be causing the fatigue,” Isaacs said.

Some patients taking GLP-1 RAs lose interest in food. Isaacs regarded this as an “adverse reaction to the medication, which necessitates either stopping it altogether, changing the dose, or adjusting the diet.” There are “many different solutions, and one size doesn’t fit all,” he said.

Dietary and Behavioral Counseling

The drugs don’t necessarily motivate a person to eat healthier food, only to eat less food, Isaacs noted.

“The person might be eating low-volume but high-calorie food, such as bag of chips or a cookie instead of an apple,” Isaacs said. Patients who are losing weight “may not realize that weight loss isn’t the only important outcome. Because they’re losing weight, they think it’s okay to eat junk food.”

Patients need education and guidance about how to eat while on these medications. Most patients find counseling about meal planning helpful, he said.

Isaacs gives nutritional guidance to his patients when he prescribes a weight loss medication. “But most physicians don’t have time to offer that type of specific counseling on an ongoing basis,” he said. Isaacs refers patients requiring more detailed and long-term guidance to a dietitian.

Patients with monotonous diets of poor quality are at increased risk for nutrition deficiencies, and counseling by a registered dietitian could help improve their dietary quality.

Registered dietitians can develop a multifaceted approach not only focusing on medication management but also on customizing the patient’s diet, assisting with lifestyle adjustments, and addressing the mental health issues surrounding obesity and its management.

People seeking obesity treatment often have psychiatric conditions, psychological distress, or disordered eating patterns, and questions and concerns have emerged about how GLP-1 RA use might affect existing mental health problems. For example, if the medication suppresses the feeling of gratification a person once got from eating high-energy dense foods, that individual may “seek rewards or pleasure elsewhere, and possibly from unhealthy sources.”

Psychological issues also may emerge as a result of weight loss, so it’s helpful to take a multidisciplinary approach that includes mental health practitioners to support patients who are being treated with GLP-1 RAs. Patients taking these agents should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of psychiatric conditions, such as depression and suicidal ideation.

Achieving significant weight loss may lead to “unexpected changes” in the dynamics of patients’ relationship with others, “which can be distressing.” Clinicians should be “sensitive to patients’ social and emotional needs” and provide support or refer patients for help with coping strategies.

GLP-1 RAs have enormous potential to improve health outcomes in patients with obesity. Careful patient selection, close monitoring, and support for patients with nutrition and other lifestyle issues can increase the chances that these agents will fulfill their potential.

Isaacs declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As the use of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) continues to exponentially expand obesity treatment, concerns have arisen regarding their impact on nutrition in people who take them.

While the medications’ dampening effects on appetite result in an average weight reduction ≥ 15%, they also pose a risk for malnutrition.

“It’s important to eat a balanced diet when taking these medications,” Deena Adimoolam, MD, an endocrinologist based in New York City and a member of the national advisory committees for the Endocrine Society and the American Diabetes Association, said in an interview.

The decreased caloric intake resulting from the use of GLP-1 RAs makes it essential for patients to consume nutrient-dense foods. Clinicians can help patients achieve a healthy diet by anticipating nutrition problems, advising them on recommended target ranges of nutrient intake, and referring them for appropriate counseling.

Where to Begin

The task begins with “setting the right expectations before the patient starts treatment,” said Scott Isaacs, MD, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

To that end, it’s important to explain to patients how the medications affect appetite and how to adapt. GLP-1 RAs don’t completely turn off the appetite, and the effect at the beginning will likely be very mild, Isaacs said in an interview.

Some patients don’t notice a change for 2-3 months, although others see an effect sooner.

“Typically, people will notice that the main impact is on satiation, meaning they’ll fill up more quickly,” said Isaacs, who is an adjunct associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. “It’s important to tell them to stop eating when they feel full because eating when full can increase the side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.”

A review article, written by lead author Jaime Almandoz, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, in Obesity offers a “5 A’s model” as a guide on how to begin discussing overweight or obesity with patients. This involves asking for permission to discuss weight and asking about food and vitamin/supplement intake; assessing the patient’s medical history and root causes of obesity, and conducting a physical examination; advising the patient regarding treatment options and reasonable expectations; agreeing on treatment and lifestyle goals; and assisting the patient to address challenges, referring them as needed to for additional support (eg, a dietitian), as well as arranging for follow-up.

Impact of GLP-1 RAs on Food Preferences

Besides reducing hunger and increasing satiety, GLP-1 RAs may affect food preferences, according to a research review published in The International Journal of Obesity. It cites a 2014 study that found that people taking GLP-1 RAs displayed decreased neuronal responses to images of food measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in the areas of brain associated with appetite and reward. This might affect taste preferences and food intake.

Additionally, a 2023 study suggested that during the weight-loss phase of treatment (as opposed to the maintenance phase), patients may experience reduced cravings for dairy and starchy food, less desire to eat salty or spicy foods, and less difficulty controlling eating and resisting cravings.

“Altered food preferences, decreased food cravings, and reduced food intake may contribute to long-term weight loss,” according to the research review. Tailored treatments focusing on the weight maintenance phase are needed, the authors wrote.

Are Patients Vulnerable to Malnutrition?

A recent review found that total caloric intake was reduced by 16%-39% in patients taking a GLP-1 RA or dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA, but few studies evaluated the composition of these patients’ diets. Research that examines the qualitative changes in macronutrient and micronutrient intake of patients on these medications is needed, the authors wrote.

They outlined several nutritional concerns, including whether GLP-1 RA or GIP/ GLP-1 RA use could result in protein intake insufficient for maintaining muscle strength, mass, and function or in inadequate dietary quality (ie, poor intake of micronutrients, fiber, and fluid).

“Although we don’t necessarily see ‘malnutrition’ in our practice, we do see patients who lose too much weight after months and months of treatment, patients who aren’t hungry and don’t eat all day and have one big meal at the end of the day because they don’t feel like eating, and people who continue to eat unhealthy foods,” Isaacs said.

Some patients, however, have medical histories placing them at a greater risk for malnutrition. “Identification of these individuals may help prevent more serious nutritional and medical complications that might occur with decreased food intake associated with AOMs [anti-obesity medications],” Almandoz and colleagues noted in their review.

What Should Patients Eat?

Nutritional needs vary based on the patient’s age, sex, body weight, physical activity, and other factors, Almandoz and colleagues wrote. For this reason, energy intake during weight loss should be “personalized.”

The authors also recommended specific sources of the various dietary components and noted red flags signaling potential deficiencies

Nutritional needs vary based on the degree of appetite suppression in the patient, Adimoolam said. “I recommend at least two servings of fruits and vegetables daily, and drinking plenty of water throughout the day,” she added.

Protein in particular is a “key macronutrient,” and insufficient intake can lead to a variety of adverse effects, including sarcopenia — which is already a concern in individuals being treated with GLP-1 RAs. Meal replacement products (eg, shakes or bars) can supplement diets to help meet protein needs, especially if appetite is significantly reduced.

“There are definitely concerns for sarcopenia, so we have our patients taking these drugs try to eat healthy lean proteins – 100 g/d — and exercise,” Isaacs said. Exercise, including resistance training, not only improves muscle mass but also potentiates the effects of the GLP-1 RAs in patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Adequate hydration is essential for patients taking GLP-1 RAs. “One of the commonly described side effects is fatigue, but there’s no biological reason why these medications should cause fatigue. My opinion is that these patients are dehydrated, and that may be causing the fatigue,” Isaacs said.

Some patients taking GLP-1 RAs lose interest in food. Isaacs regarded this as an “adverse reaction to the medication, which necessitates either stopping it altogether, changing the dose, or adjusting the diet.” There are “many different solutions, and one size doesn’t fit all,” he said.

Dietary and Behavioral Counseling

The drugs don’t necessarily motivate a person to eat healthier food, only to eat less food, Isaacs noted.

“The person might be eating low-volume but high-calorie food, such as bag of chips or a cookie instead of an apple,” Isaacs said. Patients who are losing weight “may not realize that weight loss isn’t the only important outcome. Because they’re losing weight, they think it’s okay to eat junk food.”

Patients need education and guidance about how to eat while on these medications. Most patients find counseling about meal planning helpful, he said.

Isaacs gives nutritional guidance to his patients when he prescribes a weight loss medication. “But most physicians don’t have time to offer that type of specific counseling on an ongoing basis,” he said. Isaacs refers patients requiring more detailed and long-term guidance to a dietitian.

Patients with monotonous diets of poor quality are at increased risk for nutrition deficiencies, and counseling by a registered dietitian could help improve their dietary quality.

Registered dietitians can develop a multifaceted approach not only focusing on medication management but also on customizing the patient’s diet, assisting with lifestyle adjustments, and addressing the mental health issues surrounding obesity and its management.

People seeking obesity treatment often have psychiatric conditions, psychological distress, or disordered eating patterns, and questions and concerns have emerged about how GLP-1 RA use might affect existing mental health problems. For example, if the medication suppresses the feeling of gratification a person once got from eating high-energy dense foods, that individual may “seek rewards or pleasure elsewhere, and possibly from unhealthy sources.”

Psychological issues also may emerge as a result of weight loss, so it’s helpful to take a multidisciplinary approach that includes mental health practitioners to support patients who are being treated with GLP-1 RAs. Patients taking these agents should be monitored for the emergence or worsening of psychiatric conditions, such as depression and suicidal ideation.

Achieving significant weight loss may lead to “unexpected changes” in the dynamics of patients’ relationship with others, “which can be distressing.” Clinicians should be “sensitive to patients’ social and emotional needs” and provide support or refer patients for help with coping strategies.

GLP-1 RAs have enormous potential to improve health outcomes in patients with obesity. Careful patient selection, close monitoring, and support for patients with nutrition and other lifestyle issues can increase the chances that these agents will fulfill their potential.

Isaacs declared no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

As the use of glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) continues to exponentially expand obesity treatment, concerns have arisen regarding their impact on nutrition in people who take them.

While the medications’ dampening effects on appetite result in an average weight reduction ≥ 15%, they also pose a risk for malnutrition.

“It’s important to eat a balanced diet when taking these medications,” Deena Adimoolam, MD, an endocrinologist based in New York City and a member of the national advisory committees for the Endocrine Society and the American Diabetes Association, said in an interview.

The decreased caloric intake resulting from the use of GLP-1 RAs makes it essential for patients to consume nutrient-dense foods. Clinicians can help patients achieve a healthy diet by anticipating nutrition problems, advising them on recommended target ranges of nutrient intake, and referring them for appropriate counseling.

Where to Begin

The task begins with “setting the right expectations before the patient starts treatment,” said Scott Isaacs, MD, president-elect of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology.

To that end, it’s important to explain to patients how the medications affect appetite and how to adapt. GLP-1 RAs don’t completely turn off the appetite, and the effect at the beginning will likely be very mild, Isaacs said in an interview.

Some patients don’t notice a change for 2-3 months, although others see an effect sooner.

“Typically, people will notice that the main impact is on satiation, meaning they’ll fill up more quickly,” said Isaacs, who is an adjunct associate professor at Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. “It’s important to tell them to stop eating when they feel full because eating when full can increase the side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation.”

A review article, written by lead author Jaime Almandoz, MD, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, in Obesity offers a “5 A’s model” as a guide on how to begin discussing overweight or obesity with patients. This involves asking for permission to discuss weight and asking about food and vitamin/supplement intake; assessing the patient’s medical history and root causes of obesity, and conducting a physical examination; advising the patient regarding treatment options and reasonable expectations; agreeing on treatment and lifestyle goals; and assisting the patient to address challenges, referring them as needed to for additional support (eg, a dietitian), as well as arranging for follow-up.

Impact of GLP-1 RAs on Food Preferences

Besides reducing hunger and increasing satiety, GLP-1 RAs may affect food preferences, according to a research review published in The International Journal of Obesity. It cites a 2014 study that found that people taking GLP-1 RAs displayed decreased neuronal responses to images of food measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging in the areas of brain associated with appetite and reward. This might affect taste preferences and food intake.

Additionally, a 2023 study suggested that during the weight-loss phase of treatment (as opposed to the maintenance phase), patients may experience reduced cravings for dairy and starchy food, less desire to eat salty or spicy foods, and less difficulty controlling eating and resisting cravings.

“Altered food preferences, decreased food cravings, and reduced food intake may contribute to long-term weight loss,” according to the research review. Tailored treatments focusing on the weight maintenance phase are needed, the authors wrote.

Are Patients Vulnerable to Malnutrition?

A recent review found that total caloric intake was reduced by 16%-39% in patients taking a GLP-1 RA or dual glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RA, but few studies evaluated the composition of these patients’ diets. Research that examines the qualitative changes in macronutrient and micronutrient intake of patients on these medications is needed, the authors wrote.