User login

E-Consults in Dermatology: A Retrospective Analysis

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

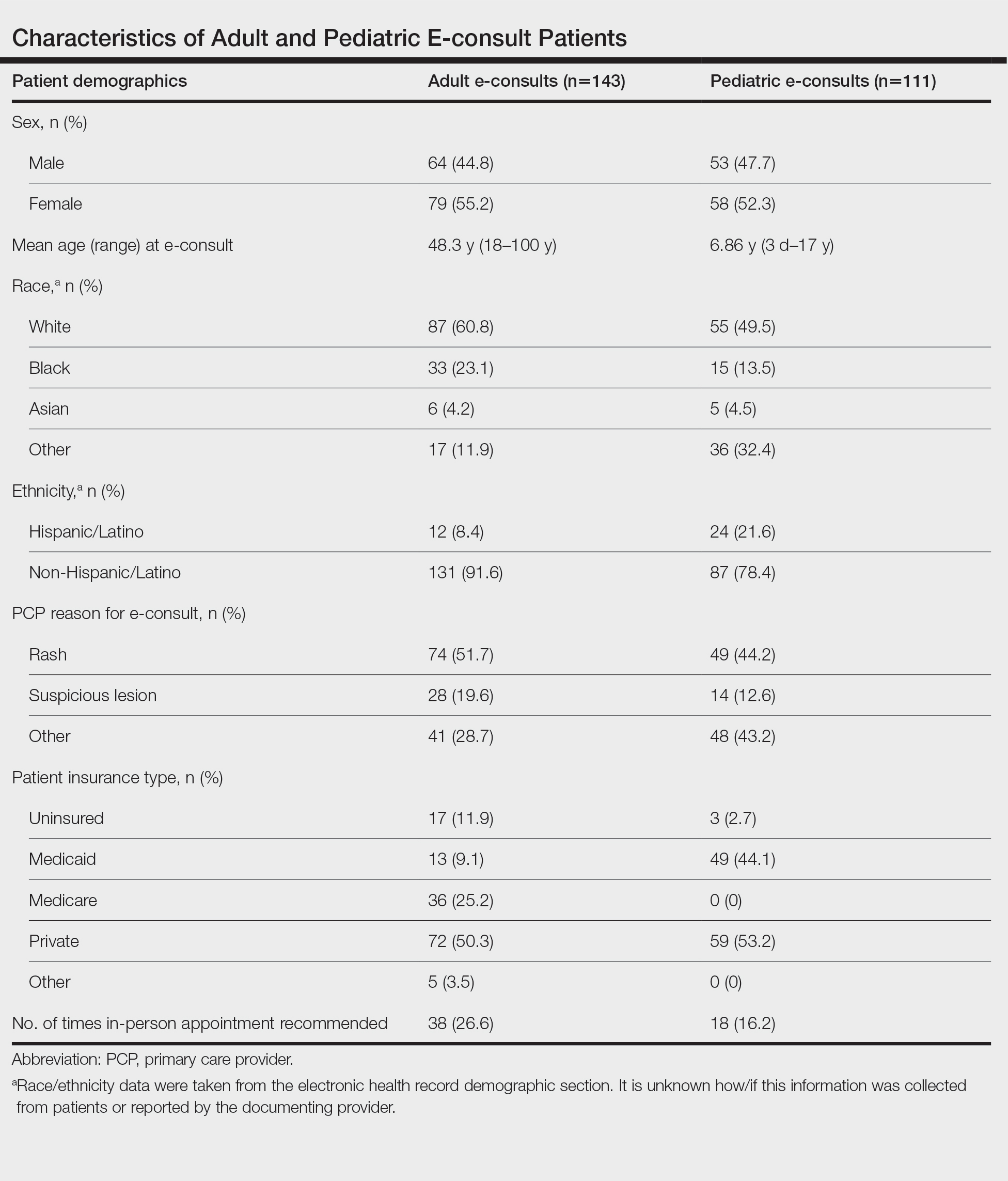

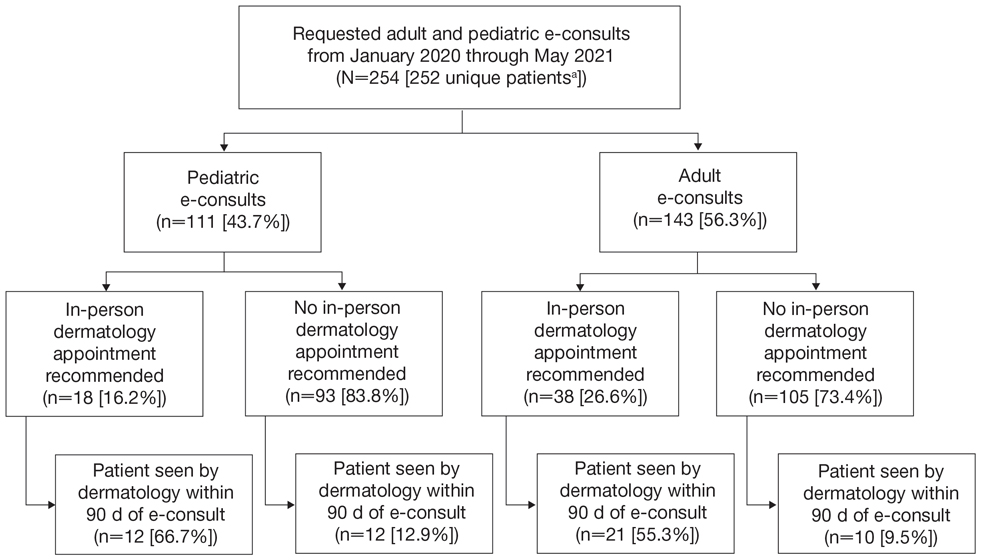

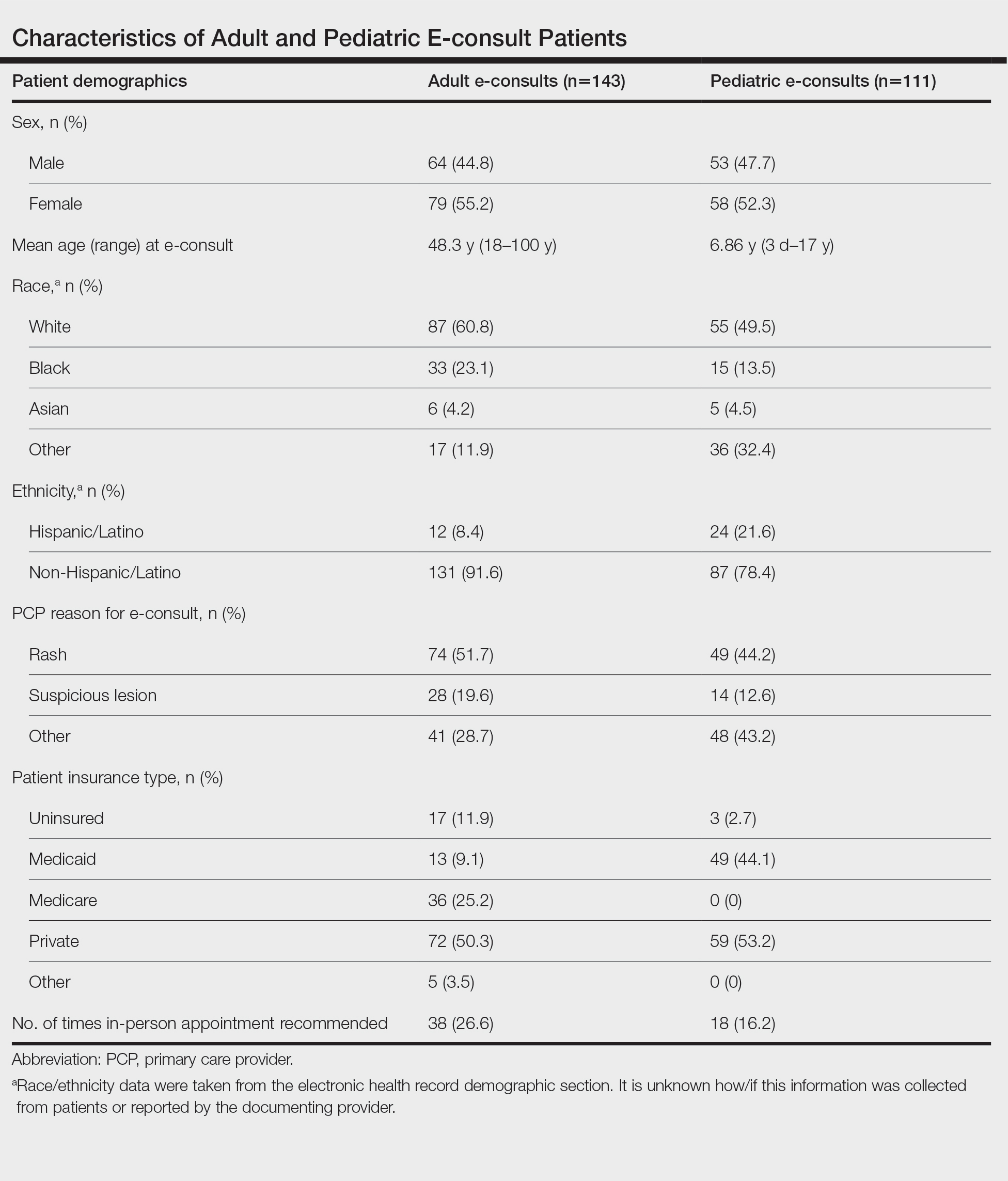

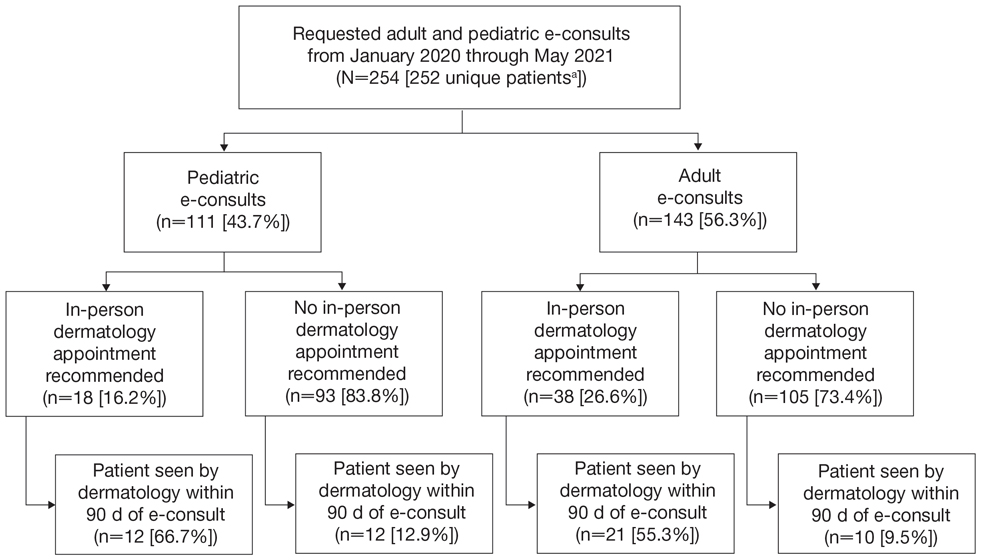

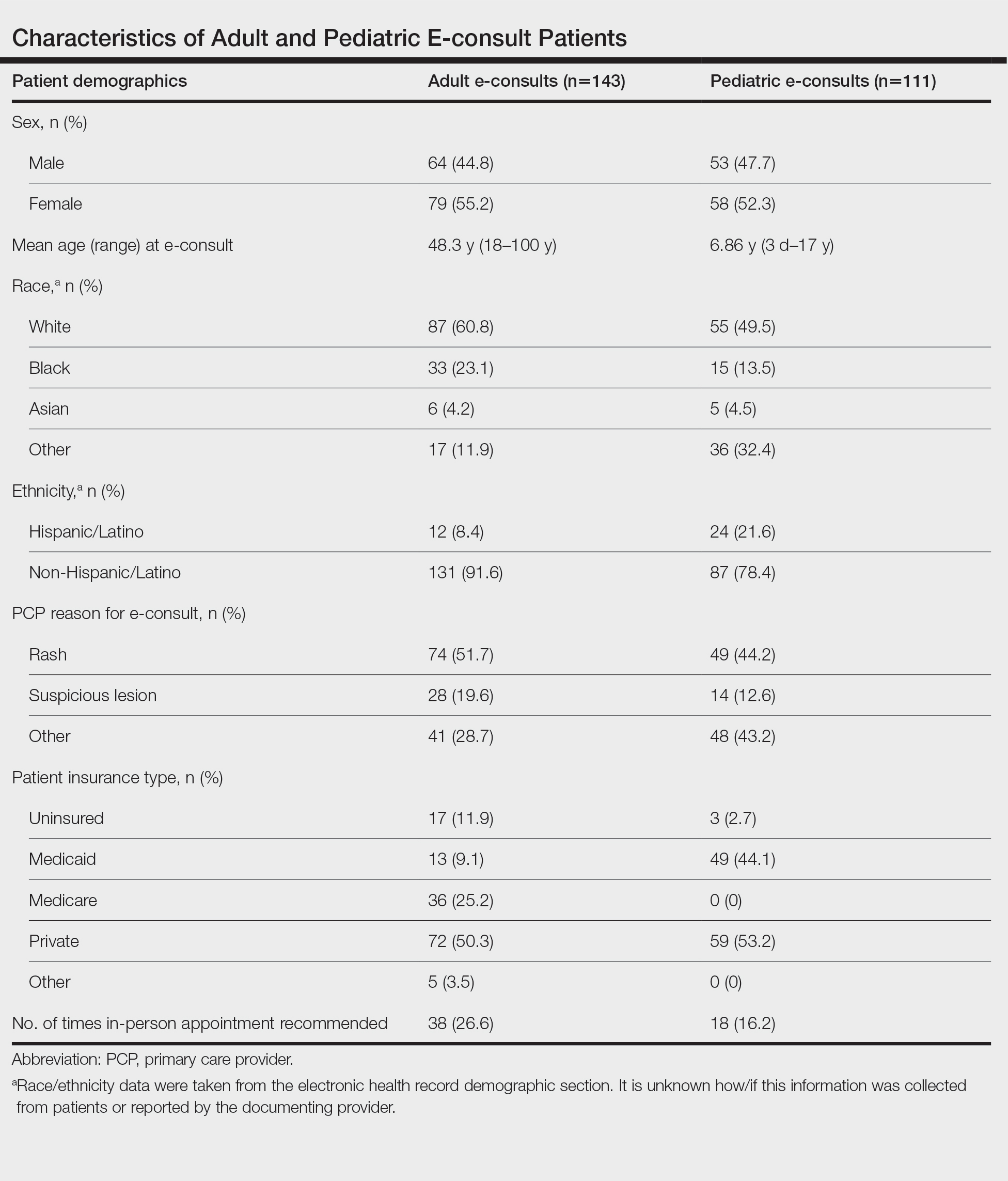

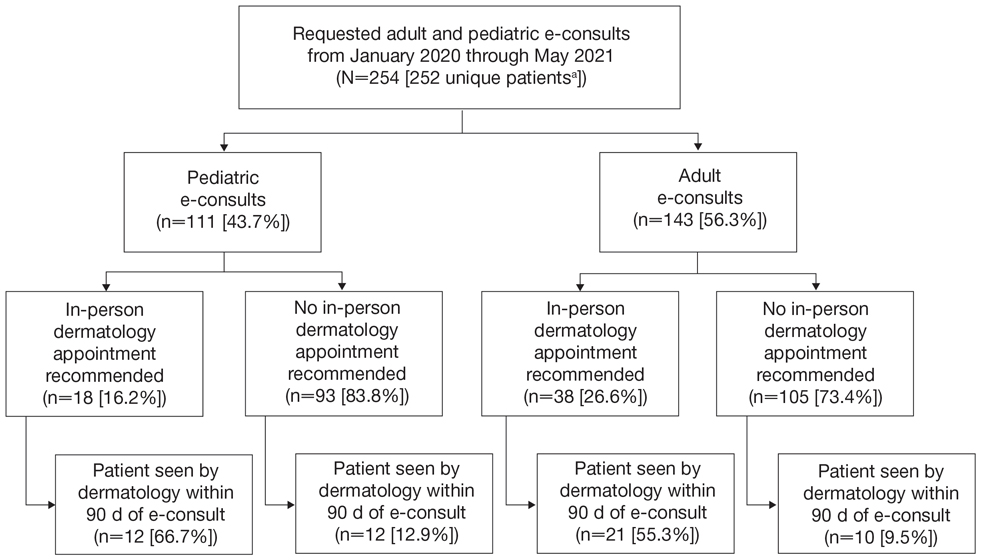

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.

Conclusion

E-consults are an effective telehealth modality that can increase patients’ access to dermatologic specialty care.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Department of Medical Education and Department of Dermatology (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their contributions to this research study as well as the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their help extracting EHR data.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Naka F, Lu J, Porto A, et al. Impact of dermatology econsults on access to care and skin cancer screening in underserved populations: a model for teledermatology services in community health centers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:293-302.

- Mulcahy A, Mehrotra A, Edison K, et al. Variation in dermatologist visits by sociodemographic characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:918-924.

- Yang X, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL. Cost analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system in Philadelphia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:758-764.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an econsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1633-1638.

- Lee KJ, Finnane A, Soyer HP. Recent trends in teledermatology and teledermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:214-223.

- Parikh PJ, Mowrey C, Gallimore J, et al. Evaluating e-consultation implementations based on use and time-line across various specialties. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108:42-48.

- Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Kalwani N, et al. Longer-term impact of cardiology e-consults. Am Heart J. 2016;173:86-93.

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: North Carolina; United States. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NC,US/PST045222

- Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander Horst A, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

- Seiger K, Hawryluk EB, Kroshinsky D, et al. Pediatric dermatology econsults: reduced wait times and dermatology office visits. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:804-810.

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.

Conclusion

E-consults are an effective telehealth modality that can increase patients’ access to dermatologic specialty care.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Department of Medical Education and Department of Dermatology (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their contributions to this research study as well as the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their help extracting EHR data.

Dermatologic conditions affect approximately one-third of individuals in the United States.1,2 Nearly 1 in 4 physician office visits in the United States are for skin conditions, and less than one-third of these visits are with dermatologists. Although many of these patients may prefer to see a dermatologist for their concerns, they may not be able to access specialist care.3 The limited supply and urban-focused distribution of dermatologists along with reduced acceptance of state-funded insurance plans and long appointment wait times all pose considerable challenges to individuals seeking dermatologic care.2 Electronic consultations (e-consults) have emerged as a promising solution to overcoming these barriers while providing high-quality dermatologic care to a large diverse patient population.2,4 Although e-consults can be of service to all dermatology patients, this modality may be especially beneficial to underserved populations, such as the uninsured and Medicaid patients—groups that historically have experienced limited access to dermatology care due to the low reimbursement rates and high administrative burdens accompanying care delivery.4 This limited access leads to inequity in care, as timely access to dermatology is associated with improved diagnostic accuracy and disease outcomes.3 E-consult implementation can facilitate timely access for these underserved populations and bypass additional barriers to care such as lack of transportation or time off work. Prior e-consult studies have demonstrated relatively high numbers of Medicaid patients utilizing e-consult services.3,5

Although in-person visits remain the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of dermatologic conditions, e-consults placed by primary care providers (PCPs) can improve access and help triage patients who require in-person dermatology visits.6 In this study, we conducted a retrospective chart review to characterize the e-consults requested of the dermatology department at a large tertiary care medical center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

Methods

The electronic health record (EHR) of Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) was screened for eligible patients from January 1, 2020, to May 31, 2021. Patients—both adult (aged ≥18 years) and pediatric (aged <18 years)—were included if they underwent a dermatology e-consult within this time frame. Provider notes in the medical records were reviewed to determine the nature of the lesion, how long the dermatologist took to complete the e-consult, whether an in-person appointment was recommended, and whether the patient was seen by dermatology within 90 days of the e-consult. Institutional review board approval was obtained.

For each e-consult, the PCP obtained clinical photographs of the lesion in question either through the EHR mobile application or by having patients upload their own photographs directly to their medical records. The referring PCP then completed a brief template regarding the patient’s clinical question and medical history and then sent the completed information to the consulting dermatologist’s EHR inbox. From there, the dermatologist could view the clinical question, documented photographs, and patient medical record to create a brief consult note with recommendations. The note was then sent back via EHR to the PCP to follow up with the patient. Patients were not charged for the e-consult.

Results

Two hundred fifty-four dermatology e-consults were requested by providers at the study center (eTable), which included 252 unique patients (2 patients had 2 separate e-consults regarding different clinical questions). The median time for completion of the e-consult—from submission of the PCP’s e-consult request to dermatologist completion—was 0.37 days. Fifty-six patients (22.0%) were recommended for an in-person appointment (Figure), 33 (58.9%) of whom ultimately scheduled the in-person appointment, and the median length of time between the completion of the e-consult and the in-person appointment was 16.5 days. The remaining 198 patients (78.0%) were not triaged to receive an in-person appointment following the e-consult,but 2 patients (8.7%) were ultimately seen in-person anyway via other referral pathways, with a median length of 33 days between e-consult completion and the in-person appointment. One hundred seventy-six patients (69.8%) avoided an in-person dermatology visit, although 38 (21.6%) of those patients were fewer than 90 days out from their e-consults at the time of data collection. The 254 e-consults included patients from 50 different zip codes, 49 (98.0%) of which were in North Carolina.

Comment

An e-consult is an asynchronous telehealth modality through which PCPs can request specialty evaluation to provide diagnostic and therapeutic guidance, facilitate PCP-specialist coordination of care, and increase access to specialty care with reduced wait times.7,8 Increased care access is especially important, as specialty referral can decrease overall health care expenditure; however, the demand for specialists often exceeds the availability.8 Our e-consult program drastically reduced the time from patients’ initial presentation at their PCP’s office to dermatologist recommendations for treatment or need for in-person dermatology follow-up.

In our analysis, patients were of different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds and lived across a variety of zip codes, predominantly in central and western North Carolina. Almost three-quarters of the patients resided in zip codes where the average income was less than the North Carolina median household income ($66,196).9 Additionally, 82 patients (32.3%) were uninsured or on Medicaid (eTable). These economically disadvantaged patient populations historically have had limited access to dermatologic care.4 One study showed that privately insured individuals were accepted as new patients by dermatologists 91% of the time compared to a 29.8% acceptance rate for publicly insured individuals.10 Uninsured and Medicaid patients also have to wait 34% longer for an appointment compared to individuals with Medicare or private insurance.2 Considering these patients may already be at an economic disadvantage when it comes to seeing and paying for dermatologic services, e-consults may reduce patient travel and appointment expenses while increasing access to specialty care. Based on a 2020 study, each e-consult generates an estimated savings of $80 out-of-pocket per patient per avoided in-person visit.11

In our study, the most common condition for an e-consult in both adult and pediatric patients was rash, which is consistent with prior e-consult studies.5,11 We found that most e-consult patients were not recommended for an in-person dermatology visit, and for those who were recommended to have an in-person visit, the wait time was reduced (Figure). These results corroborate that e-consults may be used as an important triage tool for determining whether a specialist appointment is indicated as well as a public health tool, as timely evaluation is associated with better dermatologic health care outcomes.3 However, the number of patients who did not present for an in-person appointment in our study may be overestimated, as 38 patients’ (21.6%) e-consults were conducted fewer than 90 days before our data collection. Although none of these patients had been seen in person, it is possible they requested an in-person visit after their medical records were reviewed for this study. Additionally, it is possible patients sought care from outside providers not documented in the EHR.

With regard to the payment model for the e-consult program, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist initially piloted the e-consult system through a partnership with the American Academy of Medical Colleges’ Project CORE: Coordinating Optimal Referral Experiences (https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/health-care/project-core). Grant funding through Project CORE allowed both the referring PCP and the specialist completing the e-consult to each receive approximately 0.5 relative value units in payment for each consult completed. Based on early adoption successes, the institution has created additional internal funding to support the continued expansion of the e-consult system and is incentivized to continue funding, as proper utilization of e-consults improves patient access to timely specialist care, avoids no-shows or last-minute cancellations for specialist appointments, and decreases back-door access to specialist care through the emergency department and urgent care facilities.5 Although 0.5 relative value units is not equivalent compensation to an in-person office visit, our study showed that e-consults can be completed much more quickly and efficiently and do not utilize nursing staff or other office resources.

Conclusion

E-consults are an effective telehealth modality that can increase patients’ access to dermatologic specialty care.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank the Wake Forest University School of Medicine Department of Medical Education and Department of Dermatology (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their contributions to this research study as well as the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) for their help extracting EHR data.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Naka F, Lu J, Porto A, et al. Impact of dermatology econsults on access to care and skin cancer screening in underserved populations: a model for teledermatology services in community health centers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:293-302.

- Mulcahy A, Mehrotra A, Edison K, et al. Variation in dermatologist visits by sociodemographic characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:918-924.

- Yang X, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL. Cost analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system in Philadelphia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:758-764.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an econsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1633-1638.

- Lee KJ, Finnane A, Soyer HP. Recent trends in teledermatology and teledermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:214-223.

- Parikh PJ, Mowrey C, Gallimore J, et al. Evaluating e-consultation implementations based on use and time-line across various specialties. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108:42-48.

- Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Kalwani N, et al. Longer-term impact of cardiology e-consults. Am Heart J. 2016;173:86-93.

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: North Carolina; United States. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NC,US/PST045222

- Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander Horst A, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

- Seiger K, Hawryluk EB, Kroshinsky D, et al. Pediatric dermatology econsults: reduced wait times and dermatology office visits. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:804-810.

- Hay RJ, Johns NE, Williams HC, et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: an analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1527-1534.

- Naka F, Lu J, Porto A, et al. Impact of dermatology econsults on access to care and skin cancer screening in underserved populations: a model for teledermatology services in community health centers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:293-302.

- Mulcahy A, Mehrotra A, Edison K, et al. Variation in dermatologist visits by sociodemographic characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:918-924.

- Yang X, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL. Cost analysis of a store-and-forward teledermatology consult system in Philadelphia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:758-764.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an econsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1633-1638.

- Lee KJ, Finnane A, Soyer HP. Recent trends in teledermatology and teledermoscopy. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:214-223.

- Parikh PJ, Mowrey C, Gallimore J, et al. Evaluating e-consultation implementations based on use and time-line across various specialties. Int J Med Inform. 2017;108:42-48.

- Wasfy JH, Rao SK, Kalwani N, et al. Longer-term impact of cardiology e-consults. Am Heart J. 2016;173:86-93.

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts: North Carolina; United States. Accessed February 26, 2024. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NC,US/PST045222

- Alghothani L, Jacks SK, Vander Horst A, et al. Disparities in access to dermatologic care according to insurance type. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:956-957.

- Seiger K, Hawryluk EB, Kroshinsky D, et al. Pediatric dermatology econsults: reduced wait times and dermatology office visits. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:804-810.

Practice Points

- Most electronic consult patients may be able to avoid in-person dermatology appointments.

- E-consults can increase patient access to dermatologic specialty care.

Commentary: PPI Dosing, Biomarkers, and Eating Behaviors in Patients With EoE, March 2024

This study provides compelling evidence that a twice-daily dosing regimen of moderate-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is superior to a once-daily regimen for inducing histologic remission in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). This finding suggests a significant paradigm shift in EoE management, challenging the current standard treatment guideline that recommends a PPI trial of 20-40 mg twice daily. The limited data on various dosing regimens for EoE treatment underscores the importance of this research. Dr Muftah and colleagues from Brigham and Women's Hospital have conducted a novel retrospective cohort study to address the question: Does a twice-daily PPI dose induce a higher remission rate in EoE than a once-daily regimen does regardless of the total daily dose?

The study enrolled adult patients with newly-diagnosed treatment-naive EoE at a tertiary care center, dividing participants into four groups on the basis of their treatment regimen: once-daily standard dose (20 mg omeprazole), once-daily moderate dose (40 mg), twice-daily moderate dose (20 mg), and twice-daily high dose (40 mg). Patients underwent endoscopy 8-12 weeks after initiating PPI treatment, with the primary outcome being the histologic response to PPI, defined as fewer than 15 eosinophils/high power field in repeat esophageal biopsies.

Out of 305 patients (54.6% men, mean age 44.7 ± 16.7 years), 42.3% achieved a histologic response to PPI treatment. Patients receiving the standard PPI dose (20 mg omeprazole once daily) vs those on twice-daily moderate and high doses showed significantly higher histologic response rates (52.8% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; and 54.3% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; respectively). Multivariable analysis revealed that twice-daily moderate and high doses were significantly more effective (adjusted odds ration [aOR] 6.75; CI 2.53-18.0, P = .0008; and aOR 12.8, CI 4.69-34.8, P < .001; respectively).

However, the study's retrospective design limits its ability to establish causality and may introduce selection bias. In addition, the lack of specified adjustments for PPI dosing based on diet and lifestyle factors across the cohort could influence treatment response and outcomes. Last, as a single-center study, the results may not generalize across diverse patient populations, particularly those with different demographics or disease severities.

This research heralds a shift toward a more effective treatment strategy in EoE management, suggesting that a twice-daily PPI regimen may be more beneficial than once-daily dosing is for inducing histologic remission, especially in patients inadequately responding to once-daily PPI treatment. It advocates for a personalized treatment approach, considering factors such as symptom severity, previous PPI response, and potential for adherence to a twice-daily regimen.

Distinguishing between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–induced eosinophilia and EoE poses a significant challenge for clinicians. Given that the incidence of EoE is 3-5 times higher in patients with IBD compared with the general population, there is a pressing need for new biomarkers to differentiate between these two conditions. In response to this need, Dr Butzke and colleagues at Nemours Children's Health in Wilmington, Delaware, conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the roles of Major Basic Protein (MBP) and interleukin (IL)-13 in distinguishing these diseases. The study included participants who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with esophageal biopsies for IBD workup or suspicion of EoE. It comprised 27 patients with EoE-IBD, 39 with EoE, 29 with IBD eosinophilia, 30 with IBD only, and 30 control patients. The biopsies were stained with MBP and IL-13 antibodies, and the results (percent staining/total tissue area), demographic, and clinical findings were compared among the groups.

The study revealed that MBP staining levels among patients with EoE-IBD were 3.8 units, which is significantly lower than those in the EoE group at 52.8 units and higher than those with IBD eosinophilia at 0.2 units (P < .001). IL-13 expression was significantly higher only compared with the IBD and control groups and not with EoE-IBD or IBD eosinophilia. MBP predicted EoE with 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity, whereas IL-13 demonstrated 83% sensitivity and 90% specificity using a cutoff point from the cohort of patients without EoE-IBD. Based on the MBP cutoff point of 3.49 units that distinguished between EoE and non-EoE cases, 100% of patients with EoE were MBP-positive compared with 3% of patients with IBD-associated eosinophilia (P < .05).

To implement this new biomarker into clinical practice, guidelines for interpreting MBP staining results should be developed and established, including defining cutoff points for positive and negative results. However, this study faces several limitations, such as not evaluating the differences in MBP results based on EoE-IBD type and disease activity. The retrospective nature of the study and its small sample size limit its power. In addition, the study did not assess how different treatments and disease activity affect MBP levels nor did it address the lack of longitudinal evaluation in assessing MBP levels.

Despite these limitations, the study presents a compelling case for the use of MBP as a biomarker to distinguish true EoE from EoE-IBD. This differentiation is crucial because it can guide therapeutic approaches, influencing medication choices and dietary interventions. MBP shows promise as an excellent biomarker for distinguishing true EoE from eosinophilia caused by IBD. When combined with endoscopic and histologic changes, MBP can assist with the diagnosis of EoE in IBD patients, thereby reducing the possibility of misdiagnosis.

Being diagnosed with EoE poses a challenging and life-altering experience for patients and their families. They face numerous challenges, from undergoing diagnostic procedures and treatments to adapting daily diets. Limited information is available on the eating habits of patients diagnosed with EoE. In this study, Dr Kennedy and colleagues explored how a diagnosis of EoE affects eating behaviors among pediatric patients.

The researchers conducted a prospective study involving 27 patients diagnosed with EoE and compared their eating behaviors to those of 25 healthy control participants. The participants were evaluated on the basis of their responses to four food textures (puree, soft solid, chewable, and hard solid), focusing on the number of chews per bite, sips of fluid per food, and consumption time.

The study found that, on average, patients with EoE (63.5% boys, mean age 11 years) required more chews per bite across several food textures (soft solid P = .031; chewable P = .047; and hard solid P = .037) and demonstrated increased consumption time for soft solid (P = .002), chewable (P = .005), and hard solid foods (P = .034) compared to healthy controls. In addition, endoscopic reference scores positively correlated with consumption time (r = 0.53; P = .008) and the number of chews (r = 0.45; P = .027) for chewable foods as well as with the number of chews (r = 0.44; P = .043) for hard solid foods. Increased consumption time also correlated with increased eosinophil counts (r = 0.42; P = .050) and decreased esophageal distensibility (r = -0.82; P < .0001).

Though these findings open promising avenues for the noninvasive assessment and personalized management of EoE, further research with larger, longitudinal studies is essential to validate these behaviors as reliable clinical biomarkers. Increasing the sample size would enhance the study's power and broaden the generalizability of its findings to a wider pediatric EoE population. The study's cross-sectional nature limits the ability to assess how eating behaviors change over time with treatment or disease progression.

This study underscores the potential of eating behaviors as clinical markers for pediatric patients with EoE, enabling early identification through increased chewing and consumption times, especially with harder textures. Such markers could prompt diagnostic evaluations in settings where endoscopy and biopsy are gold standards for diagnosing EoE. Moreover, eating patterns could assist in monitoring disease activity and progression, offering a noninvasive means of assessing disease status and response to therapy, thus allowing for more frequent assessments of disease status without the need for invasive procedures. Understanding these behaviors allows healthcare providers to tailor dietary advice and interventions, potentially enhancing treatment compliance and improving the quality of life for pediatric patients with EoE.

This study provides compelling evidence that a twice-daily dosing regimen of moderate-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is superior to a once-daily regimen for inducing histologic remission in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). This finding suggests a significant paradigm shift in EoE management, challenging the current standard treatment guideline that recommends a PPI trial of 20-40 mg twice daily. The limited data on various dosing regimens for EoE treatment underscores the importance of this research. Dr Muftah and colleagues from Brigham and Women's Hospital have conducted a novel retrospective cohort study to address the question: Does a twice-daily PPI dose induce a higher remission rate in EoE than a once-daily regimen does regardless of the total daily dose?

The study enrolled adult patients with newly-diagnosed treatment-naive EoE at a tertiary care center, dividing participants into four groups on the basis of their treatment regimen: once-daily standard dose (20 mg omeprazole), once-daily moderate dose (40 mg), twice-daily moderate dose (20 mg), and twice-daily high dose (40 mg). Patients underwent endoscopy 8-12 weeks after initiating PPI treatment, with the primary outcome being the histologic response to PPI, defined as fewer than 15 eosinophils/high power field in repeat esophageal biopsies.

Out of 305 patients (54.6% men, mean age 44.7 ± 16.7 years), 42.3% achieved a histologic response to PPI treatment. Patients receiving the standard PPI dose (20 mg omeprazole once daily) vs those on twice-daily moderate and high doses showed significantly higher histologic response rates (52.8% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; and 54.3% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; respectively). Multivariable analysis revealed that twice-daily moderate and high doses were significantly more effective (adjusted odds ration [aOR] 6.75; CI 2.53-18.0, P = .0008; and aOR 12.8, CI 4.69-34.8, P < .001; respectively).

However, the study's retrospective design limits its ability to establish causality and may introduce selection bias. In addition, the lack of specified adjustments for PPI dosing based on diet and lifestyle factors across the cohort could influence treatment response and outcomes. Last, as a single-center study, the results may not generalize across diverse patient populations, particularly those with different demographics or disease severities.

This research heralds a shift toward a more effective treatment strategy in EoE management, suggesting that a twice-daily PPI regimen may be more beneficial than once-daily dosing is for inducing histologic remission, especially in patients inadequately responding to once-daily PPI treatment. It advocates for a personalized treatment approach, considering factors such as symptom severity, previous PPI response, and potential for adherence to a twice-daily regimen.

Distinguishing between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–induced eosinophilia and EoE poses a significant challenge for clinicians. Given that the incidence of EoE is 3-5 times higher in patients with IBD compared with the general population, there is a pressing need for new biomarkers to differentiate between these two conditions. In response to this need, Dr Butzke and colleagues at Nemours Children's Health in Wilmington, Delaware, conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the roles of Major Basic Protein (MBP) and interleukin (IL)-13 in distinguishing these diseases. The study included participants who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with esophageal biopsies for IBD workup or suspicion of EoE. It comprised 27 patients with EoE-IBD, 39 with EoE, 29 with IBD eosinophilia, 30 with IBD only, and 30 control patients. The biopsies were stained with MBP and IL-13 antibodies, and the results (percent staining/total tissue area), demographic, and clinical findings were compared among the groups.

The study revealed that MBP staining levels among patients with EoE-IBD were 3.8 units, which is significantly lower than those in the EoE group at 52.8 units and higher than those with IBD eosinophilia at 0.2 units (P < .001). IL-13 expression was significantly higher only compared with the IBD and control groups and not with EoE-IBD or IBD eosinophilia. MBP predicted EoE with 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity, whereas IL-13 demonstrated 83% sensitivity and 90% specificity using a cutoff point from the cohort of patients without EoE-IBD. Based on the MBP cutoff point of 3.49 units that distinguished between EoE and non-EoE cases, 100% of patients with EoE were MBP-positive compared with 3% of patients with IBD-associated eosinophilia (P < .05).

To implement this new biomarker into clinical practice, guidelines for interpreting MBP staining results should be developed and established, including defining cutoff points for positive and negative results. However, this study faces several limitations, such as not evaluating the differences in MBP results based on EoE-IBD type and disease activity. The retrospective nature of the study and its small sample size limit its power. In addition, the study did not assess how different treatments and disease activity affect MBP levels nor did it address the lack of longitudinal evaluation in assessing MBP levels.

Despite these limitations, the study presents a compelling case for the use of MBP as a biomarker to distinguish true EoE from EoE-IBD. This differentiation is crucial because it can guide therapeutic approaches, influencing medication choices and dietary interventions. MBP shows promise as an excellent biomarker for distinguishing true EoE from eosinophilia caused by IBD. When combined with endoscopic and histologic changes, MBP can assist with the diagnosis of EoE in IBD patients, thereby reducing the possibility of misdiagnosis.

Being diagnosed with EoE poses a challenging and life-altering experience for patients and their families. They face numerous challenges, from undergoing diagnostic procedures and treatments to adapting daily diets. Limited information is available on the eating habits of patients diagnosed with EoE. In this study, Dr Kennedy and colleagues explored how a diagnosis of EoE affects eating behaviors among pediatric patients.

The researchers conducted a prospective study involving 27 patients diagnosed with EoE and compared their eating behaviors to those of 25 healthy control participants. The participants were evaluated on the basis of their responses to four food textures (puree, soft solid, chewable, and hard solid), focusing on the number of chews per bite, sips of fluid per food, and consumption time.

The study found that, on average, patients with EoE (63.5% boys, mean age 11 years) required more chews per bite across several food textures (soft solid P = .031; chewable P = .047; and hard solid P = .037) and demonstrated increased consumption time for soft solid (P = .002), chewable (P = .005), and hard solid foods (P = .034) compared to healthy controls. In addition, endoscopic reference scores positively correlated with consumption time (r = 0.53; P = .008) and the number of chews (r = 0.45; P = .027) for chewable foods as well as with the number of chews (r = 0.44; P = .043) for hard solid foods. Increased consumption time also correlated with increased eosinophil counts (r = 0.42; P = .050) and decreased esophageal distensibility (r = -0.82; P < .0001).

Though these findings open promising avenues for the noninvasive assessment and personalized management of EoE, further research with larger, longitudinal studies is essential to validate these behaviors as reliable clinical biomarkers. Increasing the sample size would enhance the study's power and broaden the generalizability of its findings to a wider pediatric EoE population. The study's cross-sectional nature limits the ability to assess how eating behaviors change over time with treatment or disease progression.

This study underscores the potential of eating behaviors as clinical markers for pediatric patients with EoE, enabling early identification through increased chewing and consumption times, especially with harder textures. Such markers could prompt diagnostic evaluations in settings where endoscopy and biopsy are gold standards for diagnosing EoE. Moreover, eating patterns could assist in monitoring disease activity and progression, offering a noninvasive means of assessing disease status and response to therapy, thus allowing for more frequent assessments of disease status without the need for invasive procedures. Understanding these behaviors allows healthcare providers to tailor dietary advice and interventions, potentially enhancing treatment compliance and improving the quality of life for pediatric patients with EoE.

This study provides compelling evidence that a twice-daily dosing regimen of moderate-dose proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is superior to a once-daily regimen for inducing histologic remission in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). This finding suggests a significant paradigm shift in EoE management, challenging the current standard treatment guideline that recommends a PPI trial of 20-40 mg twice daily. The limited data on various dosing regimens for EoE treatment underscores the importance of this research. Dr Muftah and colleagues from Brigham and Women's Hospital have conducted a novel retrospective cohort study to address the question: Does a twice-daily PPI dose induce a higher remission rate in EoE than a once-daily regimen does regardless of the total daily dose?

The study enrolled adult patients with newly-diagnosed treatment-naive EoE at a tertiary care center, dividing participants into four groups on the basis of their treatment regimen: once-daily standard dose (20 mg omeprazole), once-daily moderate dose (40 mg), twice-daily moderate dose (20 mg), and twice-daily high dose (40 mg). Patients underwent endoscopy 8-12 weeks after initiating PPI treatment, with the primary outcome being the histologic response to PPI, defined as fewer than 15 eosinophils/high power field in repeat esophageal biopsies.

Out of 305 patients (54.6% men, mean age 44.7 ± 16.7 years), 42.3% achieved a histologic response to PPI treatment. Patients receiving the standard PPI dose (20 mg omeprazole once daily) vs those on twice-daily moderate and high doses showed significantly higher histologic response rates (52.8% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; and 54.3% vs 11.8%, P < .0001; respectively). Multivariable analysis revealed that twice-daily moderate and high doses were significantly more effective (adjusted odds ration [aOR] 6.75; CI 2.53-18.0, P = .0008; and aOR 12.8, CI 4.69-34.8, P < .001; respectively).

However, the study's retrospective design limits its ability to establish causality and may introduce selection bias. In addition, the lack of specified adjustments for PPI dosing based on diet and lifestyle factors across the cohort could influence treatment response and outcomes. Last, as a single-center study, the results may not generalize across diverse patient populations, particularly those with different demographics or disease severities.

This research heralds a shift toward a more effective treatment strategy in EoE management, suggesting that a twice-daily PPI regimen may be more beneficial than once-daily dosing is for inducing histologic remission, especially in patients inadequately responding to once-daily PPI treatment. It advocates for a personalized treatment approach, considering factors such as symptom severity, previous PPI response, and potential for adherence to a twice-daily regimen.

Distinguishing between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)–induced eosinophilia and EoE poses a significant challenge for clinicians. Given that the incidence of EoE is 3-5 times higher in patients with IBD compared with the general population, there is a pressing need for new biomarkers to differentiate between these two conditions. In response to this need, Dr Butzke and colleagues at Nemours Children's Health in Wilmington, Delaware, conducted a retrospective study to evaluate the roles of Major Basic Protein (MBP) and interleukin (IL)-13 in distinguishing these diseases. The study included participants who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy with esophageal biopsies for IBD workup or suspicion of EoE. It comprised 27 patients with EoE-IBD, 39 with EoE, 29 with IBD eosinophilia, 30 with IBD only, and 30 control patients. The biopsies were stained with MBP and IL-13 antibodies, and the results (percent staining/total tissue area), demographic, and clinical findings were compared among the groups.

The study revealed that MBP staining levels among patients with EoE-IBD were 3.8 units, which is significantly lower than those in the EoE group at 52.8 units and higher than those with IBD eosinophilia at 0.2 units (P < .001). IL-13 expression was significantly higher only compared with the IBD and control groups and not with EoE-IBD or IBD eosinophilia. MBP predicted EoE with 100% sensitivity and 99% specificity, whereas IL-13 demonstrated 83% sensitivity and 90% specificity using a cutoff point from the cohort of patients without EoE-IBD. Based on the MBP cutoff point of 3.49 units that distinguished between EoE and non-EoE cases, 100% of patients with EoE were MBP-positive compared with 3% of patients with IBD-associated eosinophilia (P < .05).

To implement this new biomarker into clinical practice, guidelines for interpreting MBP staining results should be developed and established, including defining cutoff points for positive and negative results. However, this study faces several limitations, such as not evaluating the differences in MBP results based on EoE-IBD type and disease activity. The retrospective nature of the study and its small sample size limit its power. In addition, the study did not assess how different treatments and disease activity affect MBP levels nor did it address the lack of longitudinal evaluation in assessing MBP levels.

Despite these limitations, the study presents a compelling case for the use of MBP as a biomarker to distinguish true EoE from EoE-IBD. This differentiation is crucial because it can guide therapeutic approaches, influencing medication choices and dietary interventions. MBP shows promise as an excellent biomarker for distinguishing true EoE from eosinophilia caused by IBD. When combined with endoscopic and histologic changes, MBP can assist with the diagnosis of EoE in IBD patients, thereby reducing the possibility of misdiagnosis.

Being diagnosed with EoE poses a challenging and life-altering experience for patients and their families. They face numerous challenges, from undergoing diagnostic procedures and treatments to adapting daily diets. Limited information is available on the eating habits of patients diagnosed with EoE. In this study, Dr Kennedy and colleagues explored how a diagnosis of EoE affects eating behaviors among pediatric patients.

The researchers conducted a prospective study involving 27 patients diagnosed with EoE and compared their eating behaviors to those of 25 healthy control participants. The participants were evaluated on the basis of their responses to four food textures (puree, soft solid, chewable, and hard solid), focusing on the number of chews per bite, sips of fluid per food, and consumption time.

The study found that, on average, patients with EoE (63.5% boys, mean age 11 years) required more chews per bite across several food textures (soft solid P = .031; chewable P = .047; and hard solid P = .037) and demonstrated increased consumption time for soft solid (P = .002), chewable (P = .005), and hard solid foods (P = .034) compared to healthy controls. In addition, endoscopic reference scores positively correlated with consumption time (r = 0.53; P = .008) and the number of chews (r = 0.45; P = .027) for chewable foods as well as with the number of chews (r = 0.44; P = .043) for hard solid foods. Increased consumption time also correlated with increased eosinophil counts (r = 0.42; P = .050) and decreased esophageal distensibility (r = -0.82; P < .0001).

Though these findings open promising avenues for the noninvasive assessment and personalized management of EoE, further research with larger, longitudinal studies is essential to validate these behaviors as reliable clinical biomarkers. Increasing the sample size would enhance the study's power and broaden the generalizability of its findings to a wider pediatric EoE population. The study's cross-sectional nature limits the ability to assess how eating behaviors change over time with treatment or disease progression.

This study underscores the potential of eating behaviors as clinical markers for pediatric patients with EoE, enabling early identification through increased chewing and consumption times, especially with harder textures. Such markers could prompt diagnostic evaluations in settings where endoscopy and biopsy are gold standards for diagnosing EoE. Moreover, eating patterns could assist in monitoring disease activity and progression, offering a noninvasive means of assessing disease status and response to therapy, thus allowing for more frequent assessments of disease status without the need for invasive procedures. Understanding these behaviors allows healthcare providers to tailor dietary advice and interventions, potentially enhancing treatment compliance and improving the quality of life for pediatric patients with EoE.

Commentary: New Research on BC Chemotherapies, March 2024

The phase 3 KEYNOTE-355 trial established the role of chemotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab in the first-line setting for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive advanced triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Patients unselected for PD-L1 status in this trial who received platinum- or taxane-based chemotherapy with placebo had a median progression-free survival of 5.6 months.[3] Strategies to improve upon efficacy and tolerability are desired in this space, and various trials have evaluated "switch maintenance" that involves receipt of an intensive induction regimen followed by a switch to an alternative/more tolerable regimen after response is achieved.[4] The phase II DORA trial randomized 45 patients with advanced TNBC and ongoing stable disease or complete or partial response from first- or second-line platinum-based chemotherapy to a maintenance regimen of olaparib (300 mg orally twice daily) with or without durvalumab (1500 mg on day 1 and every 4 weeks) (Tan et al). At a median follow-up of 9.8 months, median progression-free survival was 4.0 months (95% CI 2.6-6.1) with olaparib and 6.1 months (95% CI 3.7-10.1) with the combination; both were significantly longer than the historical control of continued platinum-based therapy (P = .0023 and P < .0001, respectively). Durable disease control appeared more pronounced in patients with complete or partial response to prior platinum therapy, and no new safety signals were observed. Future efforts to study this approach include the phase 2/3 KEYLYNK-009 trial, which is evaluating olaparib plus pembrolizumab maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab for TNBC.[5]

TNBC is a heterogenous subtype, characterized by aggressive biology, and it benefits from chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatment approaches. Presently, the management of early-stage TNBC often involves neoadjuvant systemic therapy; however, a proportion of patients receive treatment in the postoperative setting, highlighting the relevance of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy as well.[6] Various prior studies have showed that delayed administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for EBC can lead to adverse survival outcomes. Furthermore, this effect is subtype-dependent, with more aggressive tumors (luminal B, triple-negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]-positive) exhibiting inferior outcomes with delayed chemotherapy.[7] A retrospective cohort study that included 245 patients with early TNBC who received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery evaluated the impact of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy in this population (Hatzipanagiotou et al). Superior survival outcomes were observed for the group receiving systemic therapy 22-28 days after surgery (median overall survival 10.2 years) compared with those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy at later time points (29-35 days, 36-42 days, and >6 weeks after surgery; median overall survival 8.3 years, 7.8 years, and 6.9 years, respectively). Patients receiving chemotherapy 22-28 days after surgery had significantly better survival than those receiving chemotherapy 29-35 days (P = .043) and >6 weeks (P = 0.033) postoperatively. This study emphasizes the importance of timely administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for early TNBC, and efforts aimed to identify potential challenges and propose solutions to optimize outcomes in this space are valuable.

Additional References

- Gnant M, Frantal S, Pfeiler G, et al, for the Austrian Breast & Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Long-term outcomes of adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200162. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200162 Source

- Fassio A, Idolazzi L, Rossini M, et al. The obesity paradox and osteoporosis. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2018;23:293-30 doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0505-2 Source

- Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al, for the KEYNOTE-355 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1817-1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9 Source

- Bachelot T, Filleron T, Bieche I, et al. Durvalumab compared to maintenance chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: The randomized phase II SAFIR02-BREAST IMMUNO trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:250-255. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01189-2 Source

- Saji S, Cussac AL, Andre F, et al. 68TiP KEYLYNK-009: a phase II/III, open-label, randomized study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + olaparib (ola) vs pembro + chemotherapy after induction with first-line (1L) pembro + chemo in patients (pts) with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC (abstract). Ann Oncol. 2020;31(Suppl 6):S1268. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.088 Source

- Ortmann O, Blohmer JU, Sibert NT, et al for 55 breast cancer centers certified by the German Cancer Society. Current clinical practice and outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: Analysis of individual data from 94,638 patients treated in 55 breast cancer centers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:1195-1209. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-03938-x Source

- Yu KD, Fan L, Qiu LX, et al. Influence of delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer survival is subtype-dependent. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46549-46556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10551 Source

The phase 3 KEYNOTE-355 trial established the role of chemotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab in the first-line setting for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive advanced triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Patients unselected for PD-L1 status in this trial who received platinum- or taxane-based chemotherapy with placebo had a median progression-free survival of 5.6 months.[3] Strategies to improve upon efficacy and tolerability are desired in this space, and various trials have evaluated "switch maintenance" that involves receipt of an intensive induction regimen followed by a switch to an alternative/more tolerable regimen after response is achieved.[4] The phase II DORA trial randomized 45 patients with advanced TNBC and ongoing stable disease or complete or partial response from first- or second-line platinum-based chemotherapy to a maintenance regimen of olaparib (300 mg orally twice daily) with or without durvalumab (1500 mg on day 1 and every 4 weeks) (Tan et al). At a median follow-up of 9.8 months, median progression-free survival was 4.0 months (95% CI 2.6-6.1) with olaparib and 6.1 months (95% CI 3.7-10.1) with the combination; both were significantly longer than the historical control of continued platinum-based therapy (P = .0023 and P < .0001, respectively). Durable disease control appeared more pronounced in patients with complete or partial response to prior platinum therapy, and no new safety signals were observed. Future efforts to study this approach include the phase 2/3 KEYLYNK-009 trial, which is evaluating olaparib plus pembrolizumab maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab for TNBC.[5]

TNBC is a heterogenous subtype, characterized by aggressive biology, and it benefits from chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatment approaches. Presently, the management of early-stage TNBC often involves neoadjuvant systemic therapy; however, a proportion of patients receive treatment in the postoperative setting, highlighting the relevance of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy as well.[6] Various prior studies have showed that delayed administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for EBC can lead to adverse survival outcomes. Furthermore, this effect is subtype-dependent, with more aggressive tumors (luminal B, triple-negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]-positive) exhibiting inferior outcomes with delayed chemotherapy.[7] A retrospective cohort study that included 245 patients with early TNBC who received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery evaluated the impact of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy in this population (Hatzipanagiotou et al). Superior survival outcomes were observed for the group receiving systemic therapy 22-28 days after surgery (median overall survival 10.2 years) compared with those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy at later time points (29-35 days, 36-42 days, and >6 weeks after surgery; median overall survival 8.3 years, 7.8 years, and 6.9 years, respectively). Patients receiving chemotherapy 22-28 days after surgery had significantly better survival than those receiving chemotherapy 29-35 days (P = .043) and >6 weeks (P = 0.033) postoperatively. This study emphasizes the importance of timely administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for early TNBC, and efforts aimed to identify potential challenges and propose solutions to optimize outcomes in this space are valuable.

Additional References

- Gnant M, Frantal S, Pfeiler G, et al, for the Austrian Breast & Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Long-term outcomes of adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200162. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200162 Source

- Fassio A, Idolazzi L, Rossini M, et al. The obesity paradox and osteoporosis. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2018;23:293-30 doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0505-2 Source

- Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al, for the KEYNOTE-355 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1817-1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9 Source

- Bachelot T, Filleron T, Bieche I, et al. Durvalumab compared to maintenance chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: The randomized phase II SAFIR02-BREAST IMMUNO trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:250-255. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01189-2 Source

- Saji S, Cussac AL, Andre F, et al. 68TiP KEYLYNK-009: a phase II/III, open-label, randomized study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + olaparib (ola) vs pembro + chemotherapy after induction with first-line (1L) pembro + chemo in patients (pts) with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC (abstract). Ann Oncol. 2020;31(Suppl 6):S1268. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.088 Source

- Ortmann O, Blohmer JU, Sibert NT, et al for 55 breast cancer centers certified by the German Cancer Society. Current clinical practice and outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: Analysis of individual data from 94,638 patients treated in 55 breast cancer centers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:1195-1209. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-03938-x Source

- Yu KD, Fan L, Qiu LX, et al. Influence of delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer survival is subtype-dependent. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46549-46556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10551 Source

The phase 3 KEYNOTE-355 trial established the role of chemotherapy in combination with pembrolizumab in the first-line setting for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive advanced triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Patients unselected for PD-L1 status in this trial who received platinum- or taxane-based chemotherapy with placebo had a median progression-free survival of 5.6 months.[3] Strategies to improve upon efficacy and tolerability are desired in this space, and various trials have evaluated "switch maintenance" that involves receipt of an intensive induction regimen followed by a switch to an alternative/more tolerable regimen after response is achieved.[4] The phase II DORA trial randomized 45 patients with advanced TNBC and ongoing stable disease or complete or partial response from first- or second-line platinum-based chemotherapy to a maintenance regimen of olaparib (300 mg orally twice daily) with or without durvalumab (1500 mg on day 1 and every 4 weeks) (Tan et al). At a median follow-up of 9.8 months, median progression-free survival was 4.0 months (95% CI 2.6-6.1) with olaparib and 6.1 months (95% CI 3.7-10.1) with the combination; both were significantly longer than the historical control of continued platinum-based therapy (P = .0023 and P < .0001, respectively). Durable disease control appeared more pronounced in patients with complete or partial response to prior platinum therapy, and no new safety signals were observed. Future efforts to study this approach include the phase 2/3 KEYLYNK-009 trial, which is evaluating olaparib plus pembrolizumab maintenance therapy after first-line chemotherapy plus pembrolizumab for TNBC.[5]

TNBC is a heterogenous subtype, characterized by aggressive biology, and it benefits from chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatment approaches. Presently, the management of early-stage TNBC often involves neoadjuvant systemic therapy; however, a proportion of patients receive treatment in the postoperative setting, highlighting the relevance of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy as well.[6] Various prior studies have showed that delayed administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for EBC can lead to adverse survival outcomes. Furthermore, this effect is subtype-dependent, with more aggressive tumors (luminal B, triple-negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]-positive) exhibiting inferior outcomes with delayed chemotherapy.[7] A retrospective cohort study that included 245 patients with early TNBC who received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery evaluated the impact of time to initiation of adjuvant therapy in this population (Hatzipanagiotou et al). Superior survival outcomes were observed for the group receiving systemic therapy 22-28 days after surgery (median overall survival 10.2 years) compared with those receiving adjuvant chemotherapy at later time points (29-35 days, 36-42 days, and >6 weeks after surgery; median overall survival 8.3 years, 7.8 years, and 6.9 years, respectively). Patients receiving chemotherapy 22-28 days after surgery had significantly better survival than those receiving chemotherapy 29-35 days (P = .043) and >6 weeks (P = 0.033) postoperatively. This study emphasizes the importance of timely administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for early TNBC, and efforts aimed to identify potential challenges and propose solutions to optimize outcomes in this space are valuable.

Additional References

- Gnant M, Frantal S, Pfeiler G, et al, for the Austrian Breast & Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Long-term outcomes of adjuvant denosumab in breast cancer. NEJM Evid. 2022;1:EVIDoa2200162. doi: 10.1056/EVIDoa2200162 Source

- Fassio A, Idolazzi L, Rossini M, et al. The obesity paradox and osteoporosis. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity. 2018;23:293-30 doi: 10.1007/s40519-018-0505-2 Source

- Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, et al, for the KEYNOTE-355 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1817-1828. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32531-9 Source

- Bachelot T, Filleron T, Bieche I, et al. Durvalumab compared to maintenance chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer: The randomized phase II SAFIR02-BREAST IMMUNO trial. Nat Med. 2021;27:250-255. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01189-2 Source

- Saji S, Cussac AL, Andre F, et al. 68TiP KEYLYNK-009: a phase II/III, open-label, randomized study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + olaparib (ola) vs pembro + chemotherapy after induction with first-line (1L) pembro + chemo in patients (pts) with locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic TNBC (abstract). Ann Oncol. 2020;31(Suppl 6):S1268. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.10.088 Source

- Ortmann O, Blohmer JU, Sibert NT, et al for 55 breast cancer centers certified by the German Cancer Society. Current clinical practice and outcome of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer: Analysis of individual data from 94,638 patients treated in 55 breast cancer centers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:1195-1209. doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-03938-x Source

- Yu KD, Fan L, Qiu LX, et al. Influence of delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy on breast cancer survival is subtype-dependent. Oncotarget. 2017;8:46549-46556. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10551 Source

Commentary: Medication Timing and Other Dupilumab Concerns, March 2024

When skin diseases affect the palm or sole, they can have a disproportionately large negative effect on patients' lives. Hand and foot dermatitis can be disabling. Simpson and colleagues find that dupilumab is an effective treatment for AD of the hands and feet. Having safe and effective treatment for hand and foot dermatitis will be life-changing for many of our patients.

Patients often do very well with biologic treatment. When they do, they often wonder, Do I need to continue taking the medication? Lasheras-Pérez and colleagues found that the great majority of patients doing well taking dupilumab for AD could stretch out their dosing interval. I suspect a lot of our patients are doing this already. I used to worry that stretching out the dosing interval might lead to antidrug antibodies and loss of activity. Such loss of activity doesn't appear common. Because we also have multiple alternative treatments for severe AD, I think it may be quite reasonable for patients to try spreading out their doses after their disease has been well controlled for a good long time.

Superficial skin infections aren't rare in children, particularly children with AD. Paller and colleagues' study is informative about the safety of dupilumab in children. The drug, which blocks a pathway of the immune system, was associated with fewer infections. This is good news. The reduction in infections could be through restoring "immune balance" (whatever that means) or by improving skin barrier function. Perhaps the low rate of infection explains why dupilumab is not considered immunosuppressive.

I love studies of drug survival because I think that knowing the percentage of patients who stay with drug treatment is a good measure of overall safety and efficacy. Pezzolo and colleagues found — perhaps not surprisingly given the extraordinary efficacy of upadacitinib for AD — that almost no one discontinued the drug over 1.5 years due to lack of efficacy. There were patients who discontinued due to adverse events (and additional patients lost to follow-up who perhaps also discontinued the drug), but 80% of patients were still in the study at the end of 1.5 years. Three patients who weren't vaccinated for shingles developed shingles; encouraging patients to get the shingles vaccine may be a prudent measure when starting patients taking upadacitinib.