User login

Myeloproliferative neoplasms increase risk for arterial and venous thrombosis

Clinical question: What are the risks for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)?

Background: Myeloproliferative neoplasms include polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis. Prior studies have investigated the incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms, but the actual magnitude of thrombosis risk relative to the general population is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective matched-cohort study.

Setting: Sweden, using the Swedish Inpatient and Cancer Registers.

Synopsis: Using data from 1987 to 2009, 9,429 patients with MPNs were compared with 35,820 control participants to determine hazard ratios for arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, and any thrombosis. The highest hazard ratios were seen within 3 months of MPN diagnosis, with hazard ratios of 4.0 (95% confidence interval, 3.6-4.4) for any thrombosis, 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis, and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis. Risk decreased but remained significantly elevated through follow-up out to 20 years after diagnosis. This decrease was thought to be caused by effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN.

This study demonstrates significantly elevated risk for thrombosis in patients with MPNs, highest shortly after diagnosis. It suggests the importance of timely diagnosis and treatment of MPNs to decrease early thrombosis risk.

Bottom line: Patients with MPNs have increased rates of arterial and venous thrombosis, with the highest rates within 3 months of diagnosis.

Citation: Hultcrantz M et al. Risk for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Mar 6;168(5):317-25.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: What are the risks for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)?

Background: Myeloproliferative neoplasms include polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis. Prior studies have investigated the incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms, but the actual magnitude of thrombosis risk relative to the general population is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective matched-cohort study.

Setting: Sweden, using the Swedish Inpatient and Cancer Registers.

Synopsis: Using data from 1987 to 2009, 9,429 patients with MPNs were compared with 35,820 control participants to determine hazard ratios for arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, and any thrombosis. The highest hazard ratios were seen within 3 months of MPN diagnosis, with hazard ratios of 4.0 (95% confidence interval, 3.6-4.4) for any thrombosis, 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis, and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis. Risk decreased but remained significantly elevated through follow-up out to 20 years after diagnosis. This decrease was thought to be caused by effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN.

This study demonstrates significantly elevated risk for thrombosis in patients with MPNs, highest shortly after diagnosis. It suggests the importance of timely diagnosis and treatment of MPNs to decrease early thrombosis risk.

Bottom line: Patients with MPNs have increased rates of arterial and venous thrombosis, with the highest rates within 3 months of diagnosis.

Citation: Hultcrantz M et al. Risk for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Mar 6;168(5):317-25.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: What are the risks for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs)?

Background: Myeloproliferative neoplasms include polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and primary myelofibrosis. Prior studies have investigated the incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms, but the actual magnitude of thrombosis risk relative to the general population is unknown.

Study design: Retrospective matched-cohort study.

Setting: Sweden, using the Swedish Inpatient and Cancer Registers.

Synopsis: Using data from 1987 to 2009, 9,429 patients with MPNs were compared with 35,820 control participants to determine hazard ratios for arterial thrombosis, venous thrombosis, and any thrombosis. The highest hazard ratios were seen within 3 months of MPN diagnosis, with hazard ratios of 4.0 (95% confidence interval, 3.6-4.4) for any thrombosis, 3.0 (95% CI, 2.7-3.4) for arterial thrombosis, and 9.7 (95% CI, 7.8-12.0) for venous thrombosis. Risk decreased but remained significantly elevated through follow-up out to 20 years after diagnosis. This decrease was thought to be caused by effective thromboprophylactic and cytoreductive treatment of the MPN.

This study demonstrates significantly elevated risk for thrombosis in patients with MPNs, highest shortly after diagnosis. It suggests the importance of timely diagnosis and treatment of MPNs to decrease early thrombosis risk.

Bottom line: Patients with MPNs have increased rates of arterial and venous thrombosis, with the highest rates within 3 months of diagnosis.

Citation: Hultcrantz M et al. Risk for arterial and venous thrombosis in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Mar 6;168(5):317-25.

Dr. Komsoukaniants is a hospitalist at UC San Diego Health and an assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego.

Steroids do not reduce mortality in patients with septic shock

Clinical question: Among patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation, does hydrocortisone reduce 90-day mortality?

Background: Septic shock is associated with a significant mortality risk, and there is no proven pharmacologic treatment other than fluids, vasopressors, and antimicrobials. Prior randomized, controlled trials have resulted in mixed outcomes, and meta-analyses and clinical practice guidelines also have not provided consistent guidance.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial.

Setting: Medical centers in Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Over a 4-year period from 2013 to 2017, 3,658 patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation were randomized to receive either a continuous infusion of 200 mg/day of hydrocortisone for 7 days or placebo. The primary outcome, death within 90 days, occurred in 511 patients (27.9%) in the hydrocortisone group and in 526 patients (28.8%) in the placebo group (P = .50).

In secondary outcome analyses, patients in the hydrocortisone group had faster resolution of shock (3 vs. 4 days; P less than .001) and a shorter duration of initial mechanical ventilation (6 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and fewer patients received blood transfusions (37.0% vs. 41.7%; P = .004). There was no difference in mortality at 28 days, recurrence of shock, number of days alive out of the ICU and hospital, recurrence of mechanical ventilation, rate of renal replacement therapy, and incidence of new-onset bacteremia or fungemia.

Bottom line: Administering hydrocortisone in patients with septic shock who are undergoing mechanical ventilation does not reduce 90-day mortality.

Citation: Venkatesh B et al. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: Among patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation, does hydrocortisone reduce 90-day mortality?

Background: Septic shock is associated with a significant mortality risk, and there is no proven pharmacologic treatment other than fluids, vasopressors, and antimicrobials. Prior randomized, controlled trials have resulted in mixed outcomes, and meta-analyses and clinical practice guidelines also have not provided consistent guidance.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial.

Setting: Medical centers in Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Over a 4-year period from 2013 to 2017, 3,658 patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation were randomized to receive either a continuous infusion of 200 mg/day of hydrocortisone for 7 days or placebo. The primary outcome, death within 90 days, occurred in 511 patients (27.9%) in the hydrocortisone group and in 526 patients (28.8%) in the placebo group (P = .50).

In secondary outcome analyses, patients in the hydrocortisone group had faster resolution of shock (3 vs. 4 days; P less than .001) and a shorter duration of initial mechanical ventilation (6 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and fewer patients received blood transfusions (37.0% vs. 41.7%; P = .004). There was no difference in mortality at 28 days, recurrence of shock, number of days alive out of the ICU and hospital, recurrence of mechanical ventilation, rate of renal replacement therapy, and incidence of new-onset bacteremia or fungemia.

Bottom line: Administering hydrocortisone in patients with septic shock who are undergoing mechanical ventilation does not reduce 90-day mortality.

Citation: Venkatesh B et al. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: Among patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation, does hydrocortisone reduce 90-day mortality?

Background: Septic shock is associated with a significant mortality risk, and there is no proven pharmacologic treatment other than fluids, vasopressors, and antimicrobials. Prior randomized, controlled trials have resulted in mixed outcomes, and meta-analyses and clinical practice guidelines also have not provided consistent guidance.

Study design: Randomized, controlled, double-blinded trial.

Setting: Medical centers in Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, and the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Over a 4-year period from 2013 to 2017, 3,658 patients with septic shock undergoing mechanical ventilation were randomized to receive either a continuous infusion of 200 mg/day of hydrocortisone for 7 days or placebo. The primary outcome, death within 90 days, occurred in 511 patients (27.9%) in the hydrocortisone group and in 526 patients (28.8%) in the placebo group (P = .50).

In secondary outcome analyses, patients in the hydrocortisone group had faster resolution of shock (3 vs. 4 days; P less than .001) and a shorter duration of initial mechanical ventilation (6 vs. 7 days; P less than .001), and fewer patients received blood transfusions (37.0% vs. 41.7%; P = .004). There was no difference in mortality at 28 days, recurrence of shock, number of days alive out of the ICU and hospital, recurrence of mechanical ventilation, rate of renal replacement therapy, and incidence of new-onset bacteremia or fungemia.

Bottom line: Administering hydrocortisone in patients with septic shock who are undergoing mechanical ventilation does not reduce 90-day mortality.

Citation: Venkatesh B et al. Adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Prompting during rounds decreases lab utilization in patients nearing discharge

Clinical question: Does prompting hospitalists during interdisciplinary rounds to discontinue lab orders on patients nearing discharge result in a decrease in lab testing?

Background: The Society of Hospital Medicine, as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign, has recommended against “repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.” Repeated phlebotomy has been shown to increase iatrogenic anemia and patient discomfort. While past interventions have been effective in decreasing lab testing, this study focused on identifying and intervening on patients who were clinically stable and nearing discharge.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: Tertiary care teaching hospital in New York.

Synopsis: As part of structured, bedside, interdisciplinary rounds, over the course of a year, this study incorporated an inquiry to identify patients who were likely to be discharged in the next 24-48 hours; the unit medical director or nurse manager then prompted staff to discontinue labs for these patients when appropriate. This was supplemented by education of clinicians and regular review of lab utilization data with hospitalists.

The percentage of patients with labs ordered in the 24 hours prior to discharge decreased from 50.1% in the preintervention period to 34.5% in the postintervention period (P = .004). The number of labs ordered per patient-day dropped from 1.96 to 1.83 (P = .01).

Bottom line: An intervention with prompting during structured interdisciplinary rounds decreased the frequency of labs ordered for patients nearing hospital discharge.

Citation: Tsega S et al. Bedside assessment of the necessity of daily lab testing for patients nearing discharge. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):38-40.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: Does prompting hospitalists during interdisciplinary rounds to discontinue lab orders on patients nearing discharge result in a decrease in lab testing?

Background: The Society of Hospital Medicine, as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign, has recommended against “repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.” Repeated phlebotomy has been shown to increase iatrogenic anemia and patient discomfort. While past interventions have been effective in decreasing lab testing, this study focused on identifying and intervening on patients who were clinically stable and nearing discharge.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: Tertiary care teaching hospital in New York.

Synopsis: As part of structured, bedside, interdisciplinary rounds, over the course of a year, this study incorporated an inquiry to identify patients who were likely to be discharged in the next 24-48 hours; the unit medical director or nurse manager then prompted staff to discontinue labs for these patients when appropriate. This was supplemented by education of clinicians and regular review of lab utilization data with hospitalists.

The percentage of patients with labs ordered in the 24 hours prior to discharge decreased from 50.1% in the preintervention period to 34.5% in the postintervention period (P = .004). The number of labs ordered per patient-day dropped from 1.96 to 1.83 (P = .01).

Bottom line: An intervention with prompting during structured interdisciplinary rounds decreased the frequency of labs ordered for patients nearing hospital discharge.

Citation: Tsega S et al. Bedside assessment of the necessity of daily lab testing for patients nearing discharge. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):38-40.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Clinical question: Does prompting hospitalists during interdisciplinary rounds to discontinue lab orders on patients nearing discharge result in a decrease in lab testing?

Background: The Society of Hospital Medicine, as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign, has recommended against “repetitive complete blood count and chemistry testing in the face of clinical and lab stability.” Repeated phlebotomy has been shown to increase iatrogenic anemia and patient discomfort. While past interventions have been effective in decreasing lab testing, this study focused on identifying and intervening on patients who were clinically stable and nearing discharge.

Study design: Prospective, observational study.

Setting: Tertiary care teaching hospital in New York.

Synopsis: As part of structured, bedside, interdisciplinary rounds, over the course of a year, this study incorporated an inquiry to identify patients who were likely to be discharged in the next 24-48 hours; the unit medical director or nurse manager then prompted staff to discontinue labs for these patients when appropriate. This was supplemented by education of clinicians and regular review of lab utilization data with hospitalists.

The percentage of patients with labs ordered in the 24 hours prior to discharge decreased from 50.1% in the preintervention period to 34.5% in the postintervention period (P = .004). The number of labs ordered per patient-day dropped from 1.96 to 1.83 (P = .01).

Bottom line: An intervention with prompting during structured interdisciplinary rounds decreased the frequency of labs ordered for patients nearing hospital discharge.

Citation: Tsega S et al. Bedside assessment of the necessity of daily lab testing for patients nearing discharge. J Hosp Med. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):38-40.

Dr. Huang is associate chief of the division of hospital medicine at UC San Diego Health and an associate professor of medicine at the University of California, San Diego.

Strategies to Improve Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Veterans With Hepatitis B Infection (FULL)

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is rising in the U.S., with an estimated 8,500 to 11,500 new cases occurring annually, representing the ninth leading cause of U.S. cancer deaths.1,2 An important risk factor for HCC is infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), an oncogenic virus. Patients with HBV infection have an associated 5- to 15-fold increased risk of HCC, compared with that of the general population.3 Despite clinician awareness of major risk factors for HCC, the disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage when patients have developed a high tumor burden or metastatic disease and have few treatment options.4

It is well recognized that U.S. veterans are disproportionately affected by hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, which also places them at risk for HCC. In contrast, the prevalence of HBV infection, which has shared routes of transmission with HCV, and its associated complications among U.S. veterans has not been fully characterized. A recent national study showed that 1% of > 2 million veterans tested for HBV infection had a positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), indicating active HBV infection.5

Routine surveillance for HCC among high-risk patients, such as those with chronic HBV infection, can lead to HCC detection at earlier stages, allowing curative treatments to be pursued more successfully.6-9 Furthermore, HBV infection can promote development of HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.10,11 Therefore, according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines, HCC screening with abdominal ultrasound is recommended every 6 to 12 months for patients with chronic HBV infection who have additional risk factors for HCC, including those aged ≥ 40 years, and patients with cirrhosis or elevated alanine aminotransferase levels (ALTs).10

Overall adherence to HCC screening recommendations in the U.S. has been low, although rates have varied depending on the underlying risk factor for HCC, provider type, patient characteristics, and practice setting.12-20 In a 2012 systematic review, the pooled HCC surveillance rate was 18.4%, but nonwhite race, low socioeconomic status, and follow-up in primary care (rather than in subspecialty clinics) were all associated with lower surveillance rates.18 Low rates of HCC screening also have been seen among veterans with cirrhosis and chronic HCV infection, and a national survey of VHA providers suggested that provider- and facility-specific factors likely contribute to variation in HCC surveillance rates.14

There are few data on HCC incidence and surveillance practices specifically among veterans with chronic HBV infection. Furthermore, the reasons for low HCC surveillance rates or potential interventions to improve adherence have not been previously explored, although recent research using national VA data showed that HCC surveillance rates did not differ significantly between patients with HBV infection and patients with HCV infection.14

Considering that veterans may be at increased risk for chronic HBV infection and subsequently for HCC and that early HCC detection can improve survival, there is a need to assess adherence to HCC screening in VA settings and to identify modifiable factors associated with the failure to pursue HCC surveillance. Understanding barriers to HCC surveillance at the patient, provider, and facility level can enable VA health care providers (HCPs) to develop strategies to improve HCC screening rates in the veteran population.

Methods

The authors conducted a mixed-methods study at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC (CMCVAMC) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected to evaluate current HCC screening practices for patients with HBV infection and to identify barriers to adherence to nationally recommended screening guidelines. The CMCVAMC Institutional Review Board approved all study activities.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were included in the quantitative study if they had ≥ 1 positive HBsAg test documented between September 1, 2003 and August 31, 2008; and ≥ 2 visits to a CMCVAMC provider within 6 months during the study period. Patients who had negative results on repeat HBsAg testing in the absence of antiviral therapy were excluded. From September 1, 2003 to December 31, 2014, the authors reviewed the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) medical records of eligible patients. Patients were assigned to a HCP group (ie, infectious disease [ID], gastroenterology [GI], or primary care) identified as being primarily responsible for management of their HBV infection.

Focus Group Implementation

Separate focus group discussions were held for primary care (2 focus groups), ID (1 focus group), and GI (1 focus group) providers, for a total of 4 focus groups. The focus group discussions were facilitated by 1 study team member (who previously had worked but had no affiliation with CMCVAMC at the time of the study). All CMCVAMC HCPs involved in the care of patients with chronic HBV infection were sent a letter that outlined the study goals and requested interested HCPs to contact the study team. The authors developed a focus group interview guide that was used to prompt discussion on specific topics, including awareness of HCC screening guidelines, self-reported practice, reasons behind nonadherence to screening, and potential interventions to improve adherence. No incentives were given to HCPs for their participation.

HCC Screening Guidelines

The main study endpoint was adherence to HCC screening guidelines for patients with HBV infection, as recommended by the AASLD.9 Specifically, AASLD guidelines recommend that patients with HBV infection at high risk for HCC should be screened using abdominal or liver ultrasound examination every 6 to 12 months. High risk for HCC was defined as: (1) presence of cirrhosis; (2) aged > 40 years and ALT elevation and/or high HBV DNA level > 2,000 IU/mL; (3) family history of HCC; (4) African Americans aged > 20 years; or (5) Asian men aged > 40 years and Asian women aged > 50 years.10

Cirrhosis was defined by documented cirrhosis diagnosis on liver biopsy or by aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) ≥ 2, which accurately identifies cirrhosis (METAVIR stage F4) in patients with chronic HBV.21 For each patient qualifying for HCC screening, the annual number of abdominal ultrasounds performed during the study period was determined, and adherence was defined as having an annual testing frequency of ≥ 1 ultrasound per year.

Providers may not have obtained a screening ultrasound if another type of abdominal imaging (eg, computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) had been performed for a separate indication and could be reviewed to evaluate for possible HCC. Therefore, the annual number of all abdominal imaging tests, including ultrasound, CT, and MRI, also was determined. Adherence, in this case defined as having ≥ 1 abdominal imaging test per year, was evaluated as a secondary endpoint.

To evaluate whether providers were recommending HCC screening, CPRS records were reviewed using the following search terms: “HCC,” “ultrasound,”

“u/s,” “hepatitis B,” and “HBV.” Patients whose CPRS records did not document their HBV infection status or mention HCC screening were identified.

HCC Diagnoses

Incident HCC diagnoses were identified during the study period, and the diagnostic evaluation was further characterized. An HCC diagnosis was considered definite if the study participant had an ICD-9 code recorded for HCC (ICD-9 155.0) or histologic diagnosis of HCC by liver biopsy. The use of an ICD-9 code for HCC diagnosis had been validated previously in a retrospective chart review of VA data.22 An HCC diagnosis was considered possible if the participant did not meet the aforementioned definition but had radiographic and clinical findings suggestive of HCC.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with HBV infection seen by primary care, GI, and ID providers were assessed using chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categoric data and analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate, for continuous data. The

proportion and 95% confidence interval (CI) of patients with adherence to HCC screening guidelines were determined by provider type. Differences in outcomes by provider group were evaluated using chi-square tests. The proportions of patients whose CPRS records did not mention their HBV infection status or address HCC screening were determined. Last, HCC incidence (diagnoses/person-years) was determined by dividing the number of definite or possible HCC cases by the total follow-up time in person-years among those with and without cirrhosis (defined earlier) as well as in those who met criteria for HCC surveillance.

For the qualitative work, all focus group discussions were recorded, and transcripts were reviewed by 3 members of the study team to categorize responses into themes, using an iterative process. Discrepancies in coding of themes were resolved by mutual agreement among the reviewers. Analysis focused on highlighting the similarities and differences among the different specialties and identifying strategies to improve provider adherence to HCC screening guidelines.

Results

Among 215 patients with a positive HBsAg test between September 1, 2003 and August 31, 2008, 14 patients were excluded because they had either a negative HBsAg test on follow-up without antiviral treatment or were not retained in care. The final study population included 201 patients with a median follow-up of 7.5 years. Forty (20%) had their HBV infection managed by primary care, while 114 (57%) had GI, and 47 (23%) had ID providers. There were 15 patients who had no documentation in the CPRS of being chronically infected with HBV despite having a positive HBsAg test during the study period.

Patients with HBV infection seen by the different provider groups were fairly similar with respect to sex, race, and some medical comorbidities (Table 1). All but 1 of the patients co-infected with HIV/HBV was seen by ID providers and were younger and more likely to receive anti-HBV therapy than were patients who were HBV mono-infected. Patients with cirrhosis or other risk factors that placed them at increased risk for HCC were more likely to be followed by GI providers.

According to AASLD recommendations, 99/201 (49.3%) of the cohort qualified for HCC screening (Figure 1). Overall adherence to HCC screening was low, with only 15/99 (15%) having ≥ 1 annual abdomen ultrasound. Twenty-seven patients (27%) had ≥ 1 type of abdominal imaging test (including ultrasound, CT, and MRI scans) performed annually. Although primary care HCPs had lower adherence rates compared with that of the other provider groups, these differences were not statistically significant (P > .1 for all comparisons).

During the study period, 5 definite and 3 possible HCC cases were identified (Table 2). Routine screening for HCC led to 5 diagnoses, and the remaining 3 cases were identified during a workup for abnormal examination findings or another suspected malignancy. Among the 8 patients with a definite or a possible diagnosis, 5 were managed by GI providers and 6 had cirrhosis by the time of HCC diagnosis. All but 2 of these patients died during the study period from HCC or related complications. Incidence of HCC was 2.8 and 0.45 cases per 100 person-years in those with and without cirrhosis, respectively. Among those meeting criteria for HCC surveillance, the incidence of HCC was 0.88 cases per 100 person-years overall.

Barriers to Guideline Adherence

Nineteen providers participated in the focus group discussions (9 primary care, 5 GI, and 5 ID). Physicians and nurse practitioners (n = 18; 95%) comprised the majority of participants. Health care providers had varying years of clinical experience at the CMCVAMC, ranging from < 1 year to > 20 years.

The authors identified 3 categories of major barriers contributing to nonadherence to HCC screening guidelines: (1) knowledge barriers, including

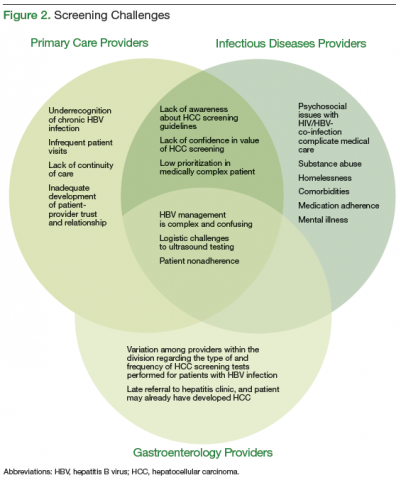

underrecognition of chronic HBV infection and lack of awareness about HCC screening guidelines; (2) motivational barriers to recommending HCC screening; and (3) technical/logistic challenges. Additional time was spent in the focus groups devising strategies to address identified barriers. An overlap in barriers to screening adherence was identified by the different HCPs (Figure 2).

Underrecognition of Chronic HBV Infection

For patients to receive appropriate HCC screening, HCPs first must be aware of their patients’ HBV infection status. However, in all the focus groups, providers indicated that chronic HBV infection likely is underdiagnosed in the veteran population because veterans at risk for HBV acquisition might not be tested, HBV serologic tests may be misinterpreted, and there may be failure to communicate positive test results during provider transitions, such as from the inpatient to outpatient setting. Typically, new HBV diagnoses are identified by CMCVAMC primary care and ID physicians, the latter serving as primary care providers (PCPs) for patients with HIV infection. All primary care and ID providers routinely obtained viral hepatitis screening in patients new to their practice, but they stated that they may be less likely to pursue HCC screening for at-risk patients.

Providers suggested implementing HBV-specific educational campaigns throughout the year to highlight the need for ongoing screening and to provide refreshers on interpretation of HBV screening serologies. They advised that, to increase appeal across providers, education should be made available in different formats, including seminars, clinic handouts, or online training modules.

An important gap in test result communication was identified during the focus group discussions. Veterans hospitalized in the psychiatric ward undergo HBV and HCV screenings (ie, testing for HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody, and HCV antibody) on admission, but no clear protocol ensured that positive screening tests were followed up in the outpatient setting. The majority of providers indicated that all newly identified diagnoses of HBV infection should receive at least an initial evaluation by a GI provider. Therefore, during discussion with the GI providers, it was proposed that the laboratory automatically notify the viral hepatitis clinic about all positive test results and the clinic designate a triage nurse to coordinate appropriate follow-up and GI referral as needed.

Unaware of HCC Screening Guidelines

Both primary care and ID providers reported that a lack of familiarity with HCC screening guidelines likely contributed to low screening rates at the CMCVAMC. Most discussants were aware that patients with HBV infection should be screened for HCC, but they did not know which test to perform, which patients to screen, and how often. Further, providers reported that chronic HBV infection was seen less frequently than was chronic HCV infection, contributing to reduced familiarity and comfort level with managing patients with HBV infection. Several participants from both primary care and ID provider groups stated they extrapolated guidelines from chronic HCV management in which HCC screening is recommended only for patients with cirrhosis and applied them to patients with HBV infection.23 In contrast, GI providers reported that they were knowledgeable about HCC screening recommendations and routinely incorporated AASLD guidelines into their practice.

To address this varying lack of awareness, all providers reiterated their support for the development of educational campaigns to be made available in different formats about HBV-related topics, including ongoing screening and interpretation of HBV screening serologies. In addition, primary care and GI providers agreed that all newly identified cases of HBV infection should receive an initial assessment by a GI provider who could outline an appropriate management strategy and determine whether GI or primary care follow-up was appropriate. In contrast, the ID providers did not endorse automatic referral to the GI clinic of new HBV diagnoses in their patients with HIV infection. Instead, ID providers stated that they were confident they could manage chronic HBV infection in their patients with HIV infection independently and refer patients as needed.

Motivational Barriers

Lack of confidence in the value of HCC screening for patients with chronic HBV infection was prevalent among primary care and ID physicians and led to reduced motivation to pursue screening tests. One provider noted that HCC is a “rare enough event that the utility of screening for this in our patient population is unclear.” Both sets of providers contrasted their different approaches to colon cancer and HCC screening: Colon cancer screening “has become more normalized and [we] have good data that early detection improves survival.” Another provider said, “There is lack of awareness about the potential benefit of HCC screening.”

Acknowledging that most patients have multiple comorbidities and often require several tests or interventions, providers in both primary care and the ID focus groups reported that it was difficult to prioritize HCC screening. Among ID physicians who primarily see patients who are co-infected with HIV/HBV, adherence to antiretroviral therapy (along with social issues, including homelessness and active substance use) often predominates clinical visits. Consequently, one participant stated, “Cancer screening goes down on the list of priorities.”

Technical Challenges

All providers identified health system and patientspecific factors that prevent successful adherence to HCC screening guidelines. At the study site, to obtain an ultrasound, the provider completes a requisition that goes directly to the radiology department, which is then responsible for contacting the patient and scheduling the ultrasound test. Ultrasound requisitions can go uncompleted for various reasons, including (1) inability to contact patients because of inaccurate contact information in the medical records; (2) long delays in test scheduling, leading to forgotten or missed appointments; and (3) lack of protocol for rescheduling missed appointments.

All providers agreed that difficulty in getting their patients to follow through on ordered tests is a major impediment to successful HCC surveillance. All providers described patient-specific factors that contribute to low HCC surveillance rates, poor medication adherence, and challenges to the overall care of these patients. These factors included active substance use, economic difficulties, and comorbidities. In addition, providers reported that alternative screening tests that could be administered at the time of the clinic visit, such as blood draws or fecal occult blood test cards, were more likely to be completed successfully in their individual practices.

Furthermore, there was variation in the way providers described the test rationale to patients, which they agreed may influence a patient’s likelihood of obtaining the test. Some providers informed their patients that the ultrasound test was intended to screen specifically for liver cancer, and they believed that concern about possible malignancy motivated patients to follow through with this testing. One of the GI providers noted that his

patients obtained recommended HCC screening because they had faced other serious consequences of HBV infection and were motivated to avoid further complications. However, other providers expressed concern that mentioning cancer might generate undue patient anxiety and instead described the test to patients as a way of evaluating general liver health. They acknowledged that placing less importance on the ultrasound test may lead to lower patient adherence.

Primary care and ID providers suggested that educational campaigns developed especially for patients may help address some of these patient specific factors. Referring to the success of public service announcements about colon cancer screening or direct-to-consumer advertising of medications, providers felt that similar approaches would be valuable for educating high-risk patients about the potential benefits of HCC surveillance and early detection.

Discussion

In this study, an extremely low HCC surveillance rate was observed among veterans with chronic HBV infection, despite HCC incidence rates that were comparable with those observed among patients in Europe and North America.24 Importantly, the incidence rate among those who met HCC surveillance criteria in this study was 0.88 cases per 100 person-years, which exceeded the 0.2 theoretical threshold incidence for efficacy of surveillance.4 This study adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating poor adherence to HCC surveillance among high-risk groups, including those with cirrhosis and chronic HCV and HBV infections.5,14,25 Because of the missed opportunities for HCC surveillance in veterans with HBV infection, the authors explored important barriers and potential strategies to improve adherence to HCC screening. Through focus groups with an open-ended discussion format, the authors were able to more comprehensively assess barriers to screening and discuss possible interventions, which had not been possible in prior studies that relied primarily on surveys.

Barriers to Screening

Underrecognition of HBV infection was recognized as a major barrier to HCC screening and likely contributed to the low HCC surveillance rates seen in this study, particularly among PCPs, who generally represent a patient’s initial encounter with the health care system. Among veterans with positive HBsAg testing during the study period, 7% had no chart documentation of being chronically infected with HBV. Through focus group discussions, it became clear that these missed cases were most frequently due to misinterpretation of HBV serologies or incomplete handoff of test results.

To prevent these errors, an automated notification process was proposed and is being developed at the CMCVAMC, whereby GI providers evaluate all positive HBsAg tests received by the laboratory to determine the appropriate follow-up. Another approach previously shown to be successful in increasing disease recognition and follow-up is the integration of hepatitis care services into other clinics (eg, substance use disorder) that serve veterans who have a high prevalence of viral hepatitis and/or risk factors.26 Proper identification of all chronic HBV patients who may need screening for HCC is the first step toward improving HCC surveillance rates.

Lack of information about HCC screening guidelines and evidence supporting screening recommendations was a recurring theme in all the focus groups and may help explain varying rates of screening adherence among the providers. Despite acknowledging the lack of awareness about screening guidelines, ID specialists were less likely than were PCPs to endorse a need for GI referral for all patients with HBV infection.

Infectious disease providers emphasized motivational barriers to HCC surveillance, which were driven by their lack of confidence in the sensitivity of the screening test and lack of awareness of improved survival with earlier HCC diagnosis. Within the past few years, studies have challenged the quality of existing evidence to support routine HCC surveillance, which possibly fueled these providers’ uncertainty about its relevance for their patients with HBV infection.27,28 Nonetheless, there seems to be limited feasibility for obtaining additional high-quality data to clarify this issue, possibly through randomized controlled trials, because of sufficient existing patient and provider preference for conducting HCC surveillance.29

The GI providers who routinely treat HCC are likely to have a different perspective from PCPs about the frequency of HCC occurrence in chronic HBV infection and the demonstrable survival benefit with early detection and thus may have greater motivation to pursue screening. Similarly, providers observed that patients who understood that the abdominal ultrasound was for the early detection of liver cancer seemed to be more likely to be adherent with providers’ ultrasound recommendations. In the absence of a clear understanding of the potential benefits of HCC screening tests, providers may be more reluctant to recommend the tests and patients may be less likely to complete them.

Education

To address these knowledge and motivational barriers, providers emphasized the need for educational opportunities designed to close these knowledge gaps and provide resources for additional information. Given the differing levels of training and experience among providers, educational programs should be multifaceted and encompass different modalities, such as in-person seminars, online training modules, and clinic-based reminders, to reach all HCPs.

Additionally, providers advocated implementing educational efforts aimed at high-risk patients to raise awareness about liver cancer. Because such programs can provide more information than can be conveyed during a brief clinic visit, they may help quell patient anxiety that is induced by the idea of liver cancer screening—an important concern expressed by various providers.

Adherence to any recommended test or medication regimen has been shown to be inversely linked to the technical or logistic complexity of the recommendation.30 At CMCVAMC an unwieldy process for obtaining abdominal or liver ultrasounds—the recommended HCC screening test—contributed to low rates of HCC surveillance. Providers noted anecdotally that screening tests that could be given during the clinic visit, such as blood draws or even fecal occult blood test cards, were more likely to be successfully completed than tests that required additional outside visits. There is no standard approach for scheduling screening sonography across the VA system, but studying screening adherence at various facilities could help identify best practices that warrant national implementation. Proposing changes to the process for ordering and obtaining an ultrasound were outside the scope of this study, given that it did not involve additional relevant staff such as radiologists and ultrasound technicians. However, this area represents future investigation that is needed to achieve substantial improvements to HCC surveillance rates within the VA health system.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. The retrospective study design limited the authors to the existing CPRS data. However, chart review primarily focused on abstracting objective data, such as the number of abdominal imaging studies performed, to arrive at a quantitative measure of HCC surveillance that likely was subject to less bias. The findings of the study, conducted at a single VA facility in Philadelphia, may not be generalizable beyond a veteran population in an urban setting. In addition, providers in the focus groups were self-motivated to participate and might not represent the experiences of other providers. Last, the relatively small number of patients seen by the different HCPs in this study may have precluded having sufficient power to detect differences in adherence rates at the provider level.

Conclusion

An extremely low HCC surveillance rate was observed among veterans with chronic HBV infection in this study. Health care providers at the CMCVAMC identified multiple challenges to ensuring routine HCC surveillance in high-risk HBV-infected patients that likely have contributed to the extremely low rates of HCC observed over the past decade.

In this qualitative study, although broad themes and areas of agreement emerged across the different HCP groups involved in caring for patients with HBV infection, there were notable differences between groups in their approaches to HCC surveillance. Engaging with HCPs about proposed interventions based on the challenges identified in the study focus groups resulted in a better understanding of their relative importance and the development of interventions more likely to be successful.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatocellular carcinoma—United States 2001—2006. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(17):517-520. Updated May 7, 2010. Accessed April 4, 2017.

2. El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5)(suppl 1):S27-S34.

3. El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(7):2557-2576.

4. Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020-1022.

5. Serper M, Choi G, Forde KA, Kaplan DE. Care delivery and outcomes among US

veterans with hepatitis B: a national cohort study. Hepatology. 2016;63(6):1774-1782.

6. El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: in whom and how? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011;4(1):5-10.

7. Singal A, Volk ML, Waljee A, et al. Meta-analysis: surveillance with ultrasound for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(1):37-47.

8. Stravitz RT, Heuman DM, Chand N, et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis improves outcome. Am J Med. 2008;121(12):119-126.

9. Tong MJ, Blatt LM, Kao VW. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic viral hepatitis in the United States of America. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16(5):553-559.

10. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50(3):661-662.

11. Trépo C, Chan HL-Y, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. The Lancet. 2014;384(9959):2053-2063.

12. Bharadwaj S, Gohel TD. Perspectives of physicians regarding screening patients at risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;4(3):237-240.

13. Chalasani N, Said A, Ness R, Hoen H, Lumeng L. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis in the United States: results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2224-2229.

14. El-Serag HB, Alsarraj A, Richardson P, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening practices in the Department of Veterans Affairs: findings from a national facility survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(11):3117-3126.

15. Khalili M, Guy J, Yu A, et al. Hepatitis B and hepatocellular carcinoma screening among Asian Americans: survey of safety net healthcare providers. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(5):1516-1523.

16. Leake I. Hepatitis B: AASLD guidelines not being followed. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(6):331.

17. Patwardhan V, Paul S, Corey KE, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma screening rates vary by etiology of cirrhosis and involvement of gastrointestinal sub-specialist. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(11):3316-3322.

18. Singal AG, Yopp A, Skinner SC, Packer M, Lee WM, Tiro JA. Utilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(7):861-867.

19. Wong CR, Garcia RT, Trinh HN, et al. Adherence to screening for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B in a community setting. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(12):2712-2721.

20. Wu Y, Johnson KB, Roccaro G, et al. Poor adherence to AASLD guidelines for chronic hepatitis B management and treatment in a large academic medical center. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(6):867-875.

21. Kim BK, Kim DY, Park JY, et al. Validation of FIB-4 and comparison with other simple noninvasive indices for predicting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Liver Int. 2010;30(4):546-553.

22. Kramer JR, Giordano TP, Souchek J, Richardson P, Hwang LY, El-Serag HB. The effect of HIV coinfection on the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in U.S. veterans with hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(1):56-63.

23. Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1335-1374.

24. El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(6):1264-1273.e1.

25. Davila JA, Henderson L, Kramer JR, et al. Utilization of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among hepatitis C virus-infected veterans in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(2):85-93.

26. Hagedorn H, Dieperink E, Dingmann D, et al. Integrating hepatitis prevention services into a substance use disorder clinic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(4):391-398.

27. Kansagara D, Papak J, Pasha AS, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):261-269.

28. Lederle FA, Pocha C. Screening for liver cancer: the rush to judgment. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):387-389.

29. Poustchi H, Farrell GC, Strasser SI, Lee AU, McCaughan GW, George J. Feasibility of conducting a randomized control trial for liver cancer screening: is a randomized controlled trial for liver cancer screening feasible or still needed? Hepatology. 2011;54(6):1998-2004.

30. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence.

Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):189-199.

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is rising in the U.S., with an estimated 8,500 to 11,500 new cases occurring annually, representing the ninth leading cause of U.S. cancer deaths.1,2 An important risk factor for HCC is infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), an oncogenic virus. Patients with HBV infection have an associated 5- to 15-fold increased risk of HCC, compared with that of the general population.3 Despite clinician awareness of major risk factors for HCC, the disease is often diagnosed at an advanced stage when patients have developed a high tumor burden or metastatic disease and have few treatment options.4

It is well recognized that U.S. veterans are disproportionately affected by hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, which also places them at risk for HCC. In contrast, the prevalence of HBV infection, which has shared routes of transmission with HCV, and its associated complications among U.S. veterans has not been fully characterized. A recent national study showed that 1% of > 2 million veterans tested for HBV infection had a positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), indicating active HBV infection.5

Routine surveillance for HCC among high-risk patients, such as those with chronic HBV infection, can lead to HCC detection at earlier stages, allowing curative treatments to be pursued more successfully.6-9 Furthermore, HBV infection can promote development of HCC even in the absence of cirrhosis.10,11 Therefore, according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines, HCC screening with abdominal ultrasound is recommended every 6 to 12 months for patients with chronic HBV infection who have additional risk factors for HCC, including those aged ≥ 40 years, and patients with cirrhosis or elevated alanine aminotransferase levels (ALTs).10

Overall adherence to HCC screening recommendations in the U.S. has been low, although rates have varied depending on the underlying risk factor for HCC, provider type, patient characteristics, and practice setting.12-20 In a 2012 systematic review, the pooled HCC surveillance rate was 18.4%, but nonwhite race, low socioeconomic status, and follow-up in primary care (rather than in subspecialty clinics) were all associated with lower surveillance rates.18 Low rates of HCC screening also have been seen among veterans with cirrhosis and chronic HCV infection, and a national survey of VHA providers suggested that provider- and facility-specific factors likely contribute to variation in HCC surveillance rates.14

There are few data on HCC incidence and surveillance practices specifically among veterans with chronic HBV infection. Furthermore, the reasons for low HCC surveillance rates or potential interventions to improve adherence have not been previously explored, although recent research using national VA data showed that HCC surveillance rates did not differ significantly between patients with HBV infection and patients with HCV infection.14

Considering that veterans may be at increased risk for chronic HBV infection and subsequently for HCC and that early HCC detection can improve survival, there is a need to assess adherence to HCC screening in VA settings and to identify modifiable factors associated with the failure to pursue HCC surveillance. Understanding barriers to HCC surveillance at the patient, provider, and facility level can enable VA health care providers (HCPs) to develop strategies to improve HCC screening rates in the veteran population.

Methods

The authors conducted a mixed-methods study at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC (CMCVAMC) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected to evaluate current HCC screening practices for patients with HBV infection and to identify barriers to adherence to nationally recommended screening guidelines. The CMCVAMC Institutional Review Board approved all study activities.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were included in the quantitative study if they had ≥ 1 positive HBsAg test documented between September 1, 2003 and August 31, 2008; and ≥ 2 visits to a CMCVAMC provider within 6 months during the study period. Patients who had negative results on repeat HBsAg testing in the absence of antiviral therapy were excluded. From September 1, 2003 to December 31, 2014, the authors reviewed the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) medical records of eligible patients. Patients were assigned to a HCP group (ie, infectious disease [ID], gastroenterology [GI], or primary care) identified as being primarily responsible for management of their HBV infection.

Focus Group Implementation

Separate focus group discussions were held for primary care (2 focus groups), ID (1 focus group), and GI (1 focus group) providers, for a total of 4 focus groups. The focus group discussions were facilitated by 1 study team member (who previously had worked but had no affiliation with CMCVAMC at the time of the study). All CMCVAMC HCPs involved in the care of patients with chronic HBV infection were sent a letter that outlined the study goals and requested interested HCPs to contact the study team. The authors developed a focus group interview guide that was used to prompt discussion on specific topics, including awareness of HCC screening guidelines, self-reported practice, reasons behind nonadherence to screening, and potential interventions to improve adherence. No incentives were given to HCPs for their participation.

HCC Screening Guidelines

The main study endpoint was adherence to HCC screening guidelines for patients with HBV infection, as recommended by the AASLD.9 Specifically, AASLD guidelines recommend that patients with HBV infection at high risk for HCC should be screened using abdominal or liver ultrasound examination every 6 to 12 months. High risk for HCC was defined as: (1) presence of cirrhosis; (2) aged > 40 years and ALT elevation and/or high HBV DNA level > 2,000 IU/mL; (3) family history of HCC; (4) African Americans aged > 20 years; or (5) Asian men aged > 40 years and Asian women aged > 50 years.10

Cirrhosis was defined by documented cirrhosis diagnosis on liver biopsy or by aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) ≥ 2, which accurately identifies cirrhosis (METAVIR stage F4) in patients with chronic HBV.21 For each patient qualifying for HCC screening, the annual number of abdominal ultrasounds performed during the study period was determined, and adherence was defined as having an annual testing frequency of ≥ 1 ultrasound per year.

Providers may not have obtained a screening ultrasound if another type of abdominal imaging (eg, computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) had been performed for a separate indication and could be reviewed to evaluate for possible HCC. Therefore, the annual number of all abdominal imaging tests, including ultrasound, CT, and MRI, also was determined. Adherence, in this case defined as having ≥ 1 abdominal imaging test per year, was evaluated as a secondary endpoint.

To evaluate whether providers were recommending HCC screening, CPRS records were reviewed using the following search terms: “HCC,” “ultrasound,”

“u/s,” “hepatitis B,” and “HBV.” Patients whose CPRS records did not document their HBV infection status or mention HCC screening were identified.

HCC Diagnoses

Incident HCC diagnoses were identified during the study period, and the diagnostic evaluation was further characterized. An HCC diagnosis was considered definite if the study participant had an ICD-9 code recorded for HCC (ICD-9 155.0) or histologic diagnosis of HCC by liver biopsy. The use of an ICD-9 code for HCC diagnosis had been validated previously in a retrospective chart review of VA data.22 An HCC diagnosis was considered possible if the participant did not meet the aforementioned definition but had radiographic and clinical findings suggestive of HCC.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with HBV infection seen by primary care, GI, and ID providers were assessed using chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categoric data and analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate, for continuous data. The

proportion and 95% confidence interval (CI) of patients with adherence to HCC screening guidelines were determined by provider type. Differences in outcomes by provider group were evaluated using chi-square tests. The proportions of patients whose CPRS records did not mention their HBV infection status or address HCC screening were determined. Last, HCC incidence (diagnoses/person-years) was determined by dividing the number of definite or possible HCC cases by the total follow-up time in person-years among those with and without cirrhosis (defined earlier) as well as in those who met criteria for HCC surveillance.

For the qualitative work, all focus group discussions were recorded, and transcripts were reviewed by 3 members of the study team to categorize responses into themes, using an iterative process. Discrepancies in coding of themes were resolved by mutual agreement among the reviewers. Analysis focused on highlighting the similarities and differences among the different specialties and identifying strategies to improve provider adherence to HCC screening guidelines.

Results

Among 215 patients with a positive HBsAg test between September 1, 2003 and August 31, 2008, 14 patients were excluded because they had either a negative HBsAg test on follow-up without antiviral treatment or were not retained in care. The final study population included 201 patients with a median follow-up of 7.5 years. Forty (20%) had their HBV infection managed by primary care, while 114 (57%) had GI, and 47 (23%) had ID providers. There were 15 patients who had no documentation in the CPRS of being chronically infected with HBV despite having a positive HBsAg test during the study period.

Patients with HBV infection seen by the different provider groups were fairly similar with respect to sex, race, and some medical comorbidities (Table 1). All but 1 of the patients co-infected with HIV/HBV was seen by ID providers and were younger and more likely to receive anti-HBV therapy than were patients who were HBV mono-infected. Patients with cirrhosis or other risk factors that placed them at increased risk for HCC were more likely to be followed by GI providers.

According to AASLD recommendations, 99/201 (49.3%) of the cohort qualified for HCC screening (Figure 1). Overall adherence to HCC screening was low, with only 15/99 (15%) having ≥ 1 annual abdomen ultrasound. Twenty-seven patients (27%) had ≥ 1 type of abdominal imaging test (including ultrasound, CT, and MRI scans) performed annually. Although primary care HCPs had lower adherence rates compared with that of the other provider groups, these differences were not statistically significant (P > .1 for all comparisons).

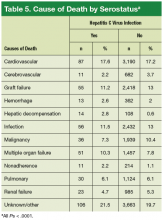

During the study period, 5 definite and 3 possible HCC cases were identified (Table 2). Routine screening for HCC led to 5 diagnoses, and the remaining 3 cases were identified during a workup for abnormal examination findings or another suspected malignancy. Among the 8 patients with a definite or a possible diagnosis, 5 were managed by GI providers and 6 had cirrhosis by the time of HCC diagnosis. All but 2 of these patients died during the study period from HCC or related complications. Incidence of HCC was 2.8 and 0.45 cases per 100 person-years in those with and without cirrhosis, respectively. Among those meeting criteria for HCC surveillance, the incidence of HCC was 0.88 cases per 100 person-years overall.

Barriers to Guideline Adherence

Nineteen providers participated in the focus group discussions (9 primary care, 5 GI, and 5 ID). Physicians and nurse practitioners (n = 18; 95%) comprised the majority of participants. Health care providers had varying years of clinical experience at the CMCVAMC, ranging from < 1 year to > 20 years.

The authors identified 3 categories of major barriers contributing to nonadherence to HCC screening guidelines: (1) knowledge barriers, including

underrecognition of chronic HBV infection and lack of awareness about HCC screening guidelines; (2) motivational barriers to recommending HCC screening; and (3) technical/logistic challenges. Additional time was spent in the focus groups devising strategies to address identified barriers. An overlap in barriers to screening adherence was identified by the different HCPs (Figure 2).

Underrecognition of Chronic HBV Infection

For patients to receive appropriate HCC screening, HCPs first must be aware of their patients’ HBV infection status. However, in all the focus groups, providers indicated that chronic HBV infection likely is underdiagnosed in the veteran population because veterans at risk for HBV acquisition might not be tested, HBV serologic tests may be misinterpreted, and there may be failure to communicate positive test results during provider transitions, such as from the inpatient to outpatient setting. Typically, new HBV diagnoses are identified by CMCVAMC primary care and ID physicians, the latter serving as primary care providers (PCPs) for patients with HIV infection. All primary care and ID providers routinely obtained viral hepatitis screening in patients new to their practice, but they stated that they may be less likely to pursue HCC screening for at-risk patients.

Providers suggested implementing HBV-specific educational campaigns throughout the year to highlight the need for ongoing screening and to provide refreshers on interpretation of HBV screening serologies. They advised that, to increase appeal across providers, education should be made available in different formats, including seminars, clinic handouts, or online training modules.

An important gap in test result communication was identified during the focus group discussions. Veterans hospitalized in the psychiatric ward undergo HBV and HCV screenings (ie, testing for HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody, and HCV antibody) on admission, but no clear protocol ensured that positive screening tests were followed up in the outpatient setting. The majority of providers indicated that all newly identified diagnoses of HBV infection should receive at least an initial evaluation by a GI provider. Therefore, during discussion with the GI providers, it was proposed that the laboratory automatically notify the viral hepatitis clinic about all positive test results and the clinic designate a triage nurse to coordinate appropriate follow-up and GI referral as needed.

Unaware of HCC Screening Guidelines

Both primary care and ID providers reported that a lack of familiarity with HCC screening guidelines likely contributed to low screening rates at the CMCVAMC. Most discussants were aware that patients with HBV infection should be screened for HCC, but they did not know which test to perform, which patients to screen, and how often. Further, providers reported that chronic HBV infection was seen less frequently than was chronic HCV infection, contributing to reduced familiarity and comfort level with managing patients with HBV infection. Several participants from both primary care and ID provider groups stated they extrapolated guidelines from chronic HCV management in which HCC screening is recommended only for patients with cirrhosis and applied them to patients with HBV infection.23 In contrast, GI providers reported that they were knowledgeable about HCC screening recommendations and routinely incorporated AASLD guidelines into their practice.

To address this varying lack of awareness, all providers reiterated their support for the development of educational campaigns to be made available in different formats about HBV-related topics, including ongoing screening and interpretation of HBV screening serologies. In addition, primary care and GI providers agreed that all newly identified cases of HBV infection should receive an initial assessment by a GI provider who could outline an appropriate management strategy and determine whether GI or primary care follow-up was appropriate. In contrast, the ID providers did not endorse automatic referral to the GI clinic of new HBV diagnoses in their patients with HIV infection. Instead, ID providers stated that they were confident they could manage chronic HBV infection in their patients with HIV infection independently and refer patients as needed.

Motivational Barriers

Lack of confidence in the value of HCC screening for patients with chronic HBV infection was prevalent among primary care and ID physicians and led to reduced motivation to pursue screening tests. One provider noted that HCC is a “rare enough event that the utility of screening for this in our patient population is unclear.” Both sets of providers contrasted their different approaches to colon cancer and HCC screening: Colon cancer screening “has become more normalized and [we] have good data that early detection improves survival.” Another provider said, “There is lack of awareness about the potential benefit of HCC screening.”

Acknowledging that most patients have multiple comorbidities and often require several tests or interventions, providers in both primary care and the ID focus groups reported that it was difficult to prioritize HCC screening. Among ID physicians who primarily see patients who are co-infected with HIV/HBV, adherence to antiretroviral therapy (along with social issues, including homelessness and active substance use) often predominates clinical visits. Consequently, one participant stated, “Cancer screening goes down on the list of priorities.”

Technical Challenges

All providers identified health system and patientspecific factors that prevent successful adherence to HCC screening guidelines. At the study site, to obtain an ultrasound, the provider completes a requisition that goes directly to the radiology department, which is then responsible for contacting the patient and scheduling the ultrasound test. Ultrasound requisitions can go uncompleted for various reasons, including (1) inability to contact patients because of inaccurate contact information in the medical records; (2) long delays in test scheduling, leading to forgotten or missed appointments; and (3) lack of protocol for rescheduling missed appointments.

All providers agreed that difficulty in getting their patients to follow through on ordered tests is a major impediment to successful HCC surveillance. All providers described patient-specific factors that contribute to low HCC surveillance rates, poor medication adherence, and challenges to the overall care of these patients. These factors included active substance use, economic difficulties, and comorbidities. In addition, providers reported that alternative screening tests that could be administered at the time of the clinic visit, such as blood draws or fecal occult blood test cards, were more likely to be completed successfully in their individual practices.

Furthermore, there was variation in the way providers described the test rationale to patients, which they agreed may influence a patient’s likelihood of obtaining the test. Some providers informed their patients that the ultrasound test was intended to screen specifically for liver cancer, and they believed that concern about possible malignancy motivated patients to follow through with this testing. One of the GI providers noted that his

patients obtained recommended HCC screening because they had faced other serious consequences of HBV infection and were motivated to avoid further complications. However, other providers expressed concern that mentioning cancer might generate undue patient anxiety and instead described the test to patients as a way of evaluating general liver health. They acknowledged that placing less importance on the ultrasound test may lead to lower patient adherence.

Primary care and ID providers suggested that educational campaigns developed especially for patients may help address some of these patient specific factors. Referring to the success of public service announcements about colon cancer screening or direct-to-consumer advertising of medications, providers felt that similar approaches would be valuable for educating high-risk patients about the potential benefits of HCC surveillance and early detection.

Discussion

In this study, an extremely low HCC surveillance rate was observed among veterans with chronic HBV infection, despite HCC incidence rates that were comparable with those observed among patients in Europe and North America.24 Importantly, the incidence rate among those who met HCC surveillance criteria in this study was 0.88 cases per 100 person-years, which exceeded the 0.2 theoretical threshold incidence for efficacy of surveillance.4 This study adds to the growing body of literature demonstrating poor adherence to HCC surveillance among high-risk groups, including those with cirrhosis and chronic HCV and HBV infections.5,14,25 Because of the missed opportunities for HCC surveillance in veterans with HBV infection, the authors explored important barriers and potential strategies to improve adherence to HCC screening. Through focus groups with an open-ended discussion format, the authors were able to more comprehensively assess barriers to screening and discuss possible interventions, which had not been possible in prior studies that relied primarily on surveys.

Barriers to Screening

Underrecognition of HBV infection was recognized as a major barrier to HCC screening and likely contributed to the low HCC surveillance rates seen in this study, particularly among PCPs, who generally represent a patient’s initial encounter with the health care system. Among veterans with positive HBsAg testing during the study period, 7% had no chart documentation of being chronically infected with HBV. Through focus group discussions, it became clear that these missed cases were most frequently due to misinterpretation of HBV serologies or incomplete handoff of test results.

To prevent these errors, an automated notification process was proposed and is being developed at the CMCVAMC, whereby GI providers evaluate all positive HBsAg tests received by the laboratory to determine the appropriate follow-up. Another approach previously shown to be successful in increasing disease recognition and follow-up is the integration of hepatitis care services into other clinics (eg, substance use disorder) that serve veterans who have a high prevalence of viral hepatitis and/or risk factors.26 Proper identification of all chronic HBV patients who may need screening for HCC is the first step toward improving HCC surveillance rates.

Lack of information about HCC screening guidelines and evidence supporting screening recommendations was a recurring theme in all the focus groups and may help explain varying rates of screening adherence among the providers. Despite acknowledging the lack of awareness about screening guidelines, ID specialists were less likely than were PCPs to endorse a need for GI referral for all patients with HBV infection.

Infectious disease providers emphasized motivational barriers to HCC surveillance, which were driven by their lack of confidence in the sensitivity of the screening test and lack of awareness of improved survival with earlier HCC diagnosis. Within the past few years, studies have challenged the quality of existing evidence to support routine HCC surveillance, which possibly fueled these providers’ uncertainty about its relevance for their patients with HBV infection.27,28 Nonetheless, there seems to be limited feasibility for obtaining additional high-quality data to clarify this issue, possibly through randomized controlled trials, because of sufficient existing patient and provider preference for conducting HCC surveillance.29

The GI providers who routinely treat HCC are likely to have a different perspective from PCPs about the frequency of HCC occurrence in chronic HBV infection and the demonstrable survival benefit with early detection and thus may have greater motivation to pursue screening. Similarly, providers observed that patients who understood that the abdominal ultrasound was for the early detection of liver cancer seemed to be more likely to be adherent with providers’ ultrasound recommendations. In the absence of a clear understanding of the potential benefits of HCC screening tests, providers may be more reluctant to recommend the tests and patients may be less likely to complete them.

Education

To address these knowledge and motivational barriers, providers emphasized the need for educational opportunities designed to close these knowledge gaps and provide resources for additional information. Given the differing levels of training and experience among providers, educational programs should be multifaceted and encompass different modalities, such as in-person seminars, online training modules, and clinic-based reminders, to reach all HCPs.

Additionally, providers advocated implementing educational efforts aimed at high-risk patients to raise awareness about liver cancer. Because such programs can provide more information than can be conveyed during a brief clinic visit, they may help quell patient anxiety that is induced by the idea of liver cancer screening—an important concern expressed by various providers.

Adherence to any recommended test or medication regimen has been shown to be inversely linked to the technical or logistic complexity of the recommendation.30 At CMCVAMC an unwieldy process for obtaining abdominal or liver ultrasounds—the recommended HCC screening test—contributed to low rates of HCC surveillance. Providers noted anecdotally that screening tests that could be given during the clinic visit, such as blood draws or even fecal occult blood test cards, were more likely to be successfully completed than tests that required additional outside visits. There is no standard approach for scheduling screening sonography across the VA system, but studying screening adherence at various facilities could help identify best practices that warrant national implementation. Proposing changes to the process for ordering and obtaining an ultrasound were outside the scope of this study, given that it did not involve additional relevant staff such as radiologists and ultrasound technicians. However, this area represents future investigation that is needed to achieve substantial improvements to HCC surveillance rates within the VA health system.

Limitations