User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

80% of Americans research recommendations post-visit

Confusion over health information and doctor advice is even higher among people who care for patients than among those who don’t provide care to their loved ones, the nationally representative survey from the AHIMA Foundation found.

The survey also shows that 80% of Americans – and an even higher portion of caregivers – are likely to research medical recommendations online after a doctor’s visit. But 1 in 4 people don’t know how to access their own medical records or find it difficult to do so.

The findings reflect the same low level of health literacy in the U.S. population that earlier surveys did. The results also indicate that little has changed since the Department of Health and Human Services released a National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy in 2010.

That plan emphasized the need to develop and share accurate health information that helps people make decisions; to promote changes in the health care system that improve health information, communication, informed decision-making, and access to health services; and to increase the sharing and use of evidence-based health literacy practices.

According to the AHIMA Foundation report, 62% of Americans are not sure they understand their doctor’s advice and the health information discussed during a visit. Twenty-four percent say they don’t comprehend any of it, and 31% can’t remember what was said during the visit. Fifteen percent of those surveyed said they were more confused about their health than they were before the encounter with their doctor.

Caregivers have special issues

Forty-three percent of Americans are caregivers, the report notes, and 91% of those play an active role in managing someone else’s health. Millennials (65%) and Gen Xers (50%) are significantly more likely than Gen Zers (39%) and Boomers (20%) to be a caregiver.

Most caregivers have concerns about their loved ones’ ability to manage their own health. Most of them believe that doctors provide enough information, but 38% don’t believe a doctor can communicate effectively with the patient if the caregiver is not present.

Forty-three percent of caretakers don’t think their loved ones can understand medical information on their own. On the other hand, caregivers are more likely than people who don’t provide care to say the doctor confused them and to research the doctor’s advice after an appointment.

For many patients and caregivers, communications break down when they are with their health care provider. Twenty-two percent of Americans say they do not feel comfortable asking their doctor certain health questions. This inability to have a satisfactory dialogue with their doctor means that many patients leave their appointments without getting clear answers to their questions (24%) or without having an opportunity to ask any questions at all (17%).

This is not surprising, considering that a 2018 study found that doctors spend only 11 seconds, on average, listening to patients before interrupting them.

Depending on the internet

Overall, the AHIMA survey found, 42% of Americans research their doctor’s recommendations after an appointment. A higher percentage of caregivers than noncaregiver peers do so (47% vs. 38%). Eighty percent of respondents say they are “likely” to research their doctor’s advice online after a visit.

When they have a medical problem or a question about their condition, just as many Americans (59%) turn to the internet for an answer as contact their doctor directly, the survey found. Twenty-nine percent of the respondents consult friends, family, or colleagues; 23% look up medical records if they’re easily accessible; 19% ask pharmacists for advice; and 6% call an unspecified 800 number.

Americans feel secure in the health information they find on the internet. Among those who go online to look up information, 86% are confident that it is credible. And 42% report feeling relieved that they can find a lot of information about their health concerns. Respondents also say that the information they gather allows them to feel more confident in their doctor’s recommendations (35%) and that they feel better after having learned more on the internet than their doctor had told them (39%). Men are more likely than women to say that their confidence in their doctor’s recommendations increased after doing online research (40% vs. 30%).

Access to health records

Access to medical records would help people better understand their condition or diagnosis. But nearly half of Americans (48%) admit they don’t usually review their medical records until long after an appointment, and 52% say they rarely access their records at all.

One in four Americans say that they don’t know where to go to access their health information or that they didn’t find the process easy. More than half of those who have never had to find their records think the process would be difficult if they had to try.

Eighty-one percent of Americans use an online platform or portal to access their medical records or health information. Two-thirds of Americans who use an online portal trust that their medical information is kept safe and not shared with other people or organizations.

Four in five respondents agree that if they had access to all of their health information, including medical records, recommendations, conditions, and test results, they’d see an improvement in their health management. Fifty-nine percent of them believe they’d also be more confident about understanding their health, and 47% say they’d have greater trust in their doctor’s recommendations. Higher percentages of caregivers than noncaregivers say the same.

Younger people, those with a high school degree or less, and those who earn less than $50,000 are less likely than older, better educated, and more affluent people to understand their doctor’s health information and to ask questions of their providers.

People of color struggle with their relationships with doctors, are less satisfied than white people with the information they receive during visits, and are more likely than white peers to feel that if they had access to all their health information, they’d manage their health better and be more confident in their doctors’ recommendations, the survey found.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Confusion over health information and doctor advice is even higher among people who care for patients than among those who don’t provide care to their loved ones, the nationally representative survey from the AHIMA Foundation found.

The survey also shows that 80% of Americans – and an even higher portion of caregivers – are likely to research medical recommendations online after a doctor’s visit. But 1 in 4 people don’t know how to access their own medical records or find it difficult to do so.

The findings reflect the same low level of health literacy in the U.S. population that earlier surveys did. The results also indicate that little has changed since the Department of Health and Human Services released a National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy in 2010.

That plan emphasized the need to develop and share accurate health information that helps people make decisions; to promote changes in the health care system that improve health information, communication, informed decision-making, and access to health services; and to increase the sharing and use of evidence-based health literacy practices.

According to the AHIMA Foundation report, 62% of Americans are not sure they understand their doctor’s advice and the health information discussed during a visit. Twenty-four percent say they don’t comprehend any of it, and 31% can’t remember what was said during the visit. Fifteen percent of those surveyed said they were more confused about their health than they were before the encounter with their doctor.

Caregivers have special issues

Forty-three percent of Americans are caregivers, the report notes, and 91% of those play an active role in managing someone else’s health. Millennials (65%) and Gen Xers (50%) are significantly more likely than Gen Zers (39%) and Boomers (20%) to be a caregiver.

Most caregivers have concerns about their loved ones’ ability to manage their own health. Most of them believe that doctors provide enough information, but 38% don’t believe a doctor can communicate effectively with the patient if the caregiver is not present.

Forty-three percent of caretakers don’t think their loved ones can understand medical information on their own. On the other hand, caregivers are more likely than people who don’t provide care to say the doctor confused them and to research the doctor’s advice after an appointment.

For many patients and caregivers, communications break down when they are with their health care provider. Twenty-two percent of Americans say they do not feel comfortable asking their doctor certain health questions. This inability to have a satisfactory dialogue with their doctor means that many patients leave their appointments without getting clear answers to their questions (24%) or without having an opportunity to ask any questions at all (17%).

This is not surprising, considering that a 2018 study found that doctors spend only 11 seconds, on average, listening to patients before interrupting them.

Depending on the internet

Overall, the AHIMA survey found, 42% of Americans research their doctor’s recommendations after an appointment. A higher percentage of caregivers than noncaregiver peers do so (47% vs. 38%). Eighty percent of respondents say they are “likely” to research their doctor’s advice online after a visit.

When they have a medical problem or a question about their condition, just as many Americans (59%) turn to the internet for an answer as contact their doctor directly, the survey found. Twenty-nine percent of the respondents consult friends, family, or colleagues; 23% look up medical records if they’re easily accessible; 19% ask pharmacists for advice; and 6% call an unspecified 800 number.

Americans feel secure in the health information they find on the internet. Among those who go online to look up information, 86% are confident that it is credible. And 42% report feeling relieved that they can find a lot of information about their health concerns. Respondents also say that the information they gather allows them to feel more confident in their doctor’s recommendations (35%) and that they feel better after having learned more on the internet than their doctor had told them (39%). Men are more likely than women to say that their confidence in their doctor’s recommendations increased after doing online research (40% vs. 30%).

Access to health records

Access to medical records would help people better understand their condition or diagnosis. But nearly half of Americans (48%) admit they don’t usually review their medical records until long after an appointment, and 52% say they rarely access their records at all.

One in four Americans say that they don’t know where to go to access their health information or that they didn’t find the process easy. More than half of those who have never had to find their records think the process would be difficult if they had to try.

Eighty-one percent of Americans use an online platform or portal to access their medical records or health information. Two-thirds of Americans who use an online portal trust that their medical information is kept safe and not shared with other people or organizations.

Four in five respondents agree that if they had access to all of their health information, including medical records, recommendations, conditions, and test results, they’d see an improvement in their health management. Fifty-nine percent of them believe they’d also be more confident about understanding their health, and 47% say they’d have greater trust in their doctor’s recommendations. Higher percentages of caregivers than noncaregivers say the same.

Younger people, those with a high school degree or less, and those who earn less than $50,000 are less likely than older, better educated, and more affluent people to understand their doctor’s health information and to ask questions of their providers.

People of color struggle with their relationships with doctors, are less satisfied than white people with the information they receive during visits, and are more likely than white peers to feel that if they had access to all their health information, they’d manage their health better and be more confident in their doctors’ recommendations, the survey found.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Confusion over health information and doctor advice is even higher among people who care for patients than among those who don’t provide care to their loved ones, the nationally representative survey from the AHIMA Foundation found.

The survey also shows that 80% of Americans – and an even higher portion of caregivers – are likely to research medical recommendations online after a doctor’s visit. But 1 in 4 people don’t know how to access their own medical records or find it difficult to do so.

The findings reflect the same low level of health literacy in the U.S. population that earlier surveys did. The results also indicate that little has changed since the Department of Health and Human Services released a National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy in 2010.

That plan emphasized the need to develop and share accurate health information that helps people make decisions; to promote changes in the health care system that improve health information, communication, informed decision-making, and access to health services; and to increase the sharing and use of evidence-based health literacy practices.

According to the AHIMA Foundation report, 62% of Americans are not sure they understand their doctor’s advice and the health information discussed during a visit. Twenty-four percent say they don’t comprehend any of it, and 31% can’t remember what was said during the visit. Fifteen percent of those surveyed said they were more confused about their health than they were before the encounter with their doctor.

Caregivers have special issues

Forty-three percent of Americans are caregivers, the report notes, and 91% of those play an active role in managing someone else’s health. Millennials (65%) and Gen Xers (50%) are significantly more likely than Gen Zers (39%) and Boomers (20%) to be a caregiver.

Most caregivers have concerns about their loved ones’ ability to manage their own health. Most of them believe that doctors provide enough information, but 38% don’t believe a doctor can communicate effectively with the patient if the caregiver is not present.

Forty-three percent of caretakers don’t think their loved ones can understand medical information on their own. On the other hand, caregivers are more likely than people who don’t provide care to say the doctor confused them and to research the doctor’s advice after an appointment.

For many patients and caregivers, communications break down when they are with their health care provider. Twenty-two percent of Americans say they do not feel comfortable asking their doctor certain health questions. This inability to have a satisfactory dialogue with their doctor means that many patients leave their appointments without getting clear answers to their questions (24%) or without having an opportunity to ask any questions at all (17%).

This is not surprising, considering that a 2018 study found that doctors spend only 11 seconds, on average, listening to patients before interrupting them.

Depending on the internet

Overall, the AHIMA survey found, 42% of Americans research their doctor’s recommendations after an appointment. A higher percentage of caregivers than noncaregiver peers do so (47% vs. 38%). Eighty percent of respondents say they are “likely” to research their doctor’s advice online after a visit.

When they have a medical problem or a question about their condition, just as many Americans (59%) turn to the internet for an answer as contact their doctor directly, the survey found. Twenty-nine percent of the respondents consult friends, family, or colleagues; 23% look up medical records if they’re easily accessible; 19% ask pharmacists for advice; and 6% call an unspecified 800 number.

Americans feel secure in the health information they find on the internet. Among those who go online to look up information, 86% are confident that it is credible. And 42% report feeling relieved that they can find a lot of information about their health concerns. Respondents also say that the information they gather allows them to feel more confident in their doctor’s recommendations (35%) and that they feel better after having learned more on the internet than their doctor had told them (39%). Men are more likely than women to say that their confidence in their doctor’s recommendations increased after doing online research (40% vs. 30%).

Access to health records

Access to medical records would help people better understand their condition or diagnosis. But nearly half of Americans (48%) admit they don’t usually review their medical records until long after an appointment, and 52% say they rarely access their records at all.

One in four Americans say that they don’t know where to go to access their health information or that they didn’t find the process easy. More than half of those who have never had to find their records think the process would be difficult if they had to try.

Eighty-one percent of Americans use an online platform or portal to access their medical records or health information. Two-thirds of Americans who use an online portal trust that their medical information is kept safe and not shared with other people or organizations.

Four in five respondents agree that if they had access to all of their health information, including medical records, recommendations, conditions, and test results, they’d see an improvement in their health management. Fifty-nine percent of them believe they’d also be more confident about understanding their health, and 47% say they’d have greater trust in their doctor’s recommendations. Higher percentages of caregivers than noncaregivers say the same.

Younger people, those with a high school degree or less, and those who earn less than $50,000 are less likely than older, better educated, and more affluent people to understand their doctor’s health information and to ask questions of their providers.

People of color struggle with their relationships with doctors, are less satisfied than white people with the information they receive during visits, and are more likely than white peers to feel that if they had access to all their health information, they’d manage their health better and be more confident in their doctors’ recommendations, the survey found.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Antidepressant may cut COVID-19–related hospitalization, mortality: TOGETHER

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant fluvoxamine (Luvox) may prevent hospitalization and death in outpatients with COVID-19, new research suggests.

Results from the placebo-controlled, multisite, phase 3 TOGETHER trial showed that in COVID-19 outpatients at high risk for complications, hospitalizations were cut by 66% and deaths were reduced by 91% in those who tolerated fluvoxamine.

“Our trial has found that fluvoxamine, an inexpensive existing drug, reduces the need for advanced disease care in this high-risk population,” wrote the investigators, led by Gilmar Reis, MD, PhD, research division, Cardresearch, Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

The findings were published online Oct. 27 in The Lancet Global Health.

Alternative mechanisms

Fluvoxamine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is an antidepressant commonly prescribed for obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Besides its known effects on serotonin, the drug acts in other molecular pathways to dampen the production of inflammatory cytokines. Those alternative mechanisms are the ones believed to help patients with COVID-19, said coinvestigator Angela Reiersen, MD, child psychiatrist at Washington University, St. Louis.

Based on cell culture and mouse studies showing effects of the molecule’s binding to the sigma-1 receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum, Dr. Reiersen came up with the idea of testing if fluvoxamine could keep COVID-19 from progressing in newly infected patients.

Dr. Reiersen and psychiatrist Eric Lenze, MD, also from Washington University, led the phase 2 trial that initially suggested fluvoxamine’s promise as an outpatient medication. They are coinvestigators on the new phase 3 adaptive platform trial called TOGETHER, which was conducted by an international team of investigators in Brazil, Canada, and the United States.

For this latest study, researchers at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., partnered with the research clinic Cardresearch in Brazil to recruit unvaccinated, high-risk adults within 7 days of developing flu-like symptoms from COVID-19. They analyzed 1,497 newly symptomatic COVID-19 patients at 11 clinical sites in Brazil.

Patients entered the trial between January and August 2021 and were assigned to receive 100 mg fluvoxamine or placebo pills twice a day for 10 days. Investigators monitored participants through 28 days post treatment, noting whether complications developed requiring hospitalization or more than 6 hours of emergency care.

In the placebo group, 119 of 756 patients (15.7%) worsened to this extent. In comparison, 79 of 741 (10.7%) fluvoxamine-treated patients met these primary criteria. This represented a 32% reduction in hospitalizations and emergency visits.

Additional analysis requested

As Lancet Global Health reviewed these findings from the submitted manuscript, journal reviewers requested an additional “pre-protocol analysis” that was not specified in the trial’s original protocol. The request was to examine the subgroup of patients with good adherence (74% of treated group, 82% of placebo group).

Among these three quarters of patients who took at least 80% of their doses, benefits were better.

Fluvoxamine cut serious complications in this group by 66% and reduced mortality by 91%. In the placebo group, 12 people died compared with one who received the study drug.

from complications of the infection.

However, clinicians should note that the drug can cause side effects such as nausea, dizziness, and insomnia, she added. In addition, because it prevents the body from metabolizing caffeine, patients should limit their daily intake to half of a small cup of coffee or one can of soda or one tea while taking the drug.

Previous research has shown that fluvoxamine affects the metabolism of some drugs, such as theophylline, clozapine, olanzapine, and tizanidine.

Despite huge challenges with studying generic drugs as early COVID-19 treatment, the TOGETHER trial shows it is possible to produce quality evidence during a pandemic on a shoestring budget, noted co-principal investigator Edward Mills, PhD, professor in the department of health research methods, evidence, and impact at McMaster University.

To screen more than 12,000 patients and enroll 4,000 to test nine interventions, “our total budget was less than $8 million,” Dr. Mills said. The trial was funded by Fast Grants and the Rainwater Charitable Foundation.

‘A $10 medicine’

Commenting on the findings, David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease physician-researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, noted fluvoxamine is “a $10 medicine that’s available and has a very good safety record.”

By comparison, a 5-day course of Merck’s antiviral molnupiravir, another oral drug that the company says can cut hospitalizations in COVID-19 outpatients, costs $700. However, the data have not been peer reviewed – and molnupiravir is not currently available and has unknown long-term safety implications, Dr. Boulware said.

Pharmaceutical companies typically spend tens of thousands of dollars on a trial evaluating a single drug, he noted.

In addition, the National Institutes of Health’s ACTIV-6 study, a nationwide trial on the effect of fluvoxamine and other repurposed generic drugs on thousands of COVID-19 outpatients, is a $110 million effort, according to Dr. Boulware, who cochairs its steering committee.

ACTIV-6 is currently enrolling outpatients with COVID-19 to test a lower dose of fluvoxamine, at 50 mg twice daily instead of the 100-mg dose used in the TOGETHER trial, as well as ivermectin and inhaled fluticasone. The COVID-OUT trial is also recruiting newly diagnosed COVID-19 patients to test various combinations of fluvoxamine, ivermectin, and the diabetes drug metformin.

Unanswered safety, efficacy questions

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet Global Health, Otavio Berwanger, MD, cardiologist and clinical trialist, Academic Research Organization, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, commends the investigators for rapidly generating evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite the important findings, “some questions related to efficacy and safety of fluvoxamine for patients with COVID-19 remain open,” Dr. Berwanger wrote.

The effects of the drug on reducing both mortality and hospitalizations also “still need addressing,” he noted.

“In addition, it remains to be established whether fluvoxamine has an additive effect to other therapies such as monoclonal antibodies and budesonide, and what is the optimal fluvoxamine therapeutic scheme,” wrote Dr. Berwanger.

In an interview, he noted that 74% of the Brazil population have currently received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and 52% have received two doses. In addition, deaths have gone down from 4,000 per day during the March-April second wave to about 400 per day. “That is still unfortunate and far from ideal,” he said. In total, they have had about 600,000 deaths because of COVID-19.

Asked whether public health authorities are now recommending fluvoxamine as an early treatment for COVID-19 based on the TOGETHER trial data, Dr. Berwanger answered, “Not yet.

“I believe medical and scientific societies will need to critically appraise the manuscript in order to inform their decisions and recommendations. This interesting trial adds another important piece of information in this regard,” he said.

Dr. Reiersen and Dr. Lenze are inventors on a patent application related to methods for treating COVID-19, which was filed by Washington University. Dr. Mills reports no relevant financial relationships, as does Dr. Boulware – except that the TOGETHER trial funders are also funding the University of Minnesota COVID-OUT trial. Dr. Berwanger reports having received research grants outside of the submitted work that were paid to his institution by AstraZeneca, Bayer, Amgen, Servier, Novartis, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians underprescribe behavior therapy for preschool ADHD

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

The majority of families of preschool children with a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were not offered behavior therapy as a first-line treatment, according to data from nearly 200 children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ current clinical practice guidelines recommend parent training in behavior management (PTBM) as a first-line treatment for children aged 4-5 years diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or symptoms of ADHD such as hyperactivity or impulsivity, but data on how well primary care providers follow this recommendation in practice are lacking, wrote Yair Bannett, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues.

To investigate the rates of PTBM recommendations, the researchers reviewed electronic health records for 22,714 children aged 48-71 months who had at least two visits to any 1 of 10 primary care practices in a California pediatric health network between Oct. 1, 2015, and Dec. 31, 2019. Children with an autism diagnosis were excluded; ADHD-related visits were identified via ADHD diagnosis codes or symptom-level diagnosis codes.

In the study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, 192 children (1%) had either an ADHD diagnosis or ADHD symptoms; of these, 21 (11%) received referrals for PTBM during ADHD-related primary care visits. Records showed an additional 55 patients (29%) had a mention of counseling on PTBM by a primary care provider, including handouts.

PCPs prescribed ADHD medications for 32 children; 9 of these had documented PTBM recommendations, and in 4 cases, the PCPs recommended PTBM before prescribing a first medication.

A majority (73%) of the children were male, 64% were privately insured, 56% had subspecialists involved in their care, and 17% were prescribed ADHD medications (88% of which were stimulants).

In a multivariate analysis, children with public insurance were significantly less likely to receive a PTBM recommendation than were those with private insurance (adjusted relative risk 0.87).

The most common recommendation overall was routine/habit modifications (for 79 children), such as reducing sugar or adding supplements to the diet; improving sleep hygiene; and limiting screen time.

The low rates of PTBM among publicly insured patients in particular highlight the need to identify factors behind disparities in recommended treatments, the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the reliance on primary care provider documentation during the study period and the inclusion only of medical record reviews with diagnostic codes for ADHD, the researchers noted. Further studies beyond a single health care system are needed to assess generalizability, they added.

However, the results present an opportunity for primary care providers to improve adherence to clinical practice guidelines and establish behavioral treatment at an early age to mitigate long-term morbidity, they concluded.

Low rates highlight barriers and opportunities

“We were surprised to find very low rates of documented recommendations for behavioral treatment mentioned by PCPs,” Dr. Bannett said in an interview. The researchers were surprised that recommendations for changes in daily routines and habits, such as reduced sugar intake, regular exercise, better sleep, and reduced screen time, were the most common recommendations for families of children presenting with symptoms of ADHD. “Though these are good recommendations that can support the general health of any young child, there is no evidence to support their benefit in alleviating symptoms of ADHD,” he said.

Dr. Bannett acknowledged the challenge for pediatricians to stay current on where and how families can access this type of behavioral treatment, but the evidence supports behavior therapy over medication in preschool children, he said.

“I think that it is important for primary care clinicians to know that there are options for parent training in behavioral management for both privately and publicly insured patients,” said Dr. Bannett. “In California, for example, parent training programs are offered through county mental health services. In some counties, there are other organizations that offer parent training for underserved populations and those with public insurance,” he said.

Dr. Bannett noted that online treatments, including behavioral treatments, may be possible for some families.

He cited Triple P, an evidence-based curriculum for parent training in behavior management, which offers an online course for parents at triplep-parenting.com, and an online parent training course offered through the CHADD website (chadd.org/parent-to-parent/).

Dr. Bannett noted that the researchers are planning a follow-up study to investigate the reasons behind the low referral rates for PTBM. “A known barrier is the limited availability of therapists who can provide this type of therapy,” Dr. Bannett said. “Research is needed on the effectiveness of online versions of parent training, which can overcome some of the access barriers many families experience,” he added.

“Additionally, since behavioral treatment requires a significant effort on the part of the parents and caregivers, who often are not able to complete the therapy, there is a need for research on ways to enhance parent and family engagement and participation in these important evidence-based treatments,” as well as a need to research ways to increase adherence to evidence-based practices, said Dr. Bannett. “We are currently planning intervention studies that will enhance primary care clinicians’ knowledge and clinical practice; for example, decision support tools in the electronic health record, and up-to-date information about available resources and behavioral therapists in their community that they can share with families,” he said.

Barriers make it difficult to adhere to guidelines

The study authors missed a significant element of the AAP guidelines by failing to acknowledge the extensive accompanying section on barriers to adoption, which details why most pediatricians in clinical practice do not prescribe PTBM, Herschel Lessin, MD, of Children’s Medical Group, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., said in an interview.

“Academically, it is a wonderful article,” said Dr. Lessin, who was a member of the authoring committee of the AAP guidelines and a major contributor to the section on barriers. The AAP guidelines recommend PTBM because it is evidence based, but the barrier section is essential to understanding that this evidence-based recommendation is nearly impossible to follow in real-world clinical practice, he emphasized.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ “Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents,” published in October of 2019 in Pediatrics, included a full subsection on barriers as to why the guidelines might not be followed in many cases in a real-world setting, and the study authors failed to acknowledge this section and its implications, said Dr. Lessin. Notably, the barriers section was originally published in Pediatrics under a Supplemental Data tab that might easily be overlooked by someone reviewing the main practice guideline recommendations, he said.

In most areas of the country, PTBM is simply unavailable, Dr. Lessin said.

There is a dearth of mental health providers in the United States in general, and “a monstrous shortage of mental health practitioners for young children,” he said. Children in underserved areas barely have access to a medical home, let alone mental health subspecialists, he added.

Even in areas where specialized behavior therapy may be available, it can be prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patients, Dr. Lessin noted. Insurance does not cover this type of behavior therapy, and most mental health professionals don’t accept Medicaid, nor commercial insurance, he said.

“I don’t even bother with those referrals, because they are not available,” said Dr. Lessin. The take-home message is that most community-based pediatricians are not following the guidelines because the barriers are so enormous, he said.

The study was supported by a research grant from the Society of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics and salary support through the Instructor Support Program at the department of pediatrics, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, to Dr. Bannett. The researchers had no other financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Lessin had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the editorial advisory board of Pediatric News.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

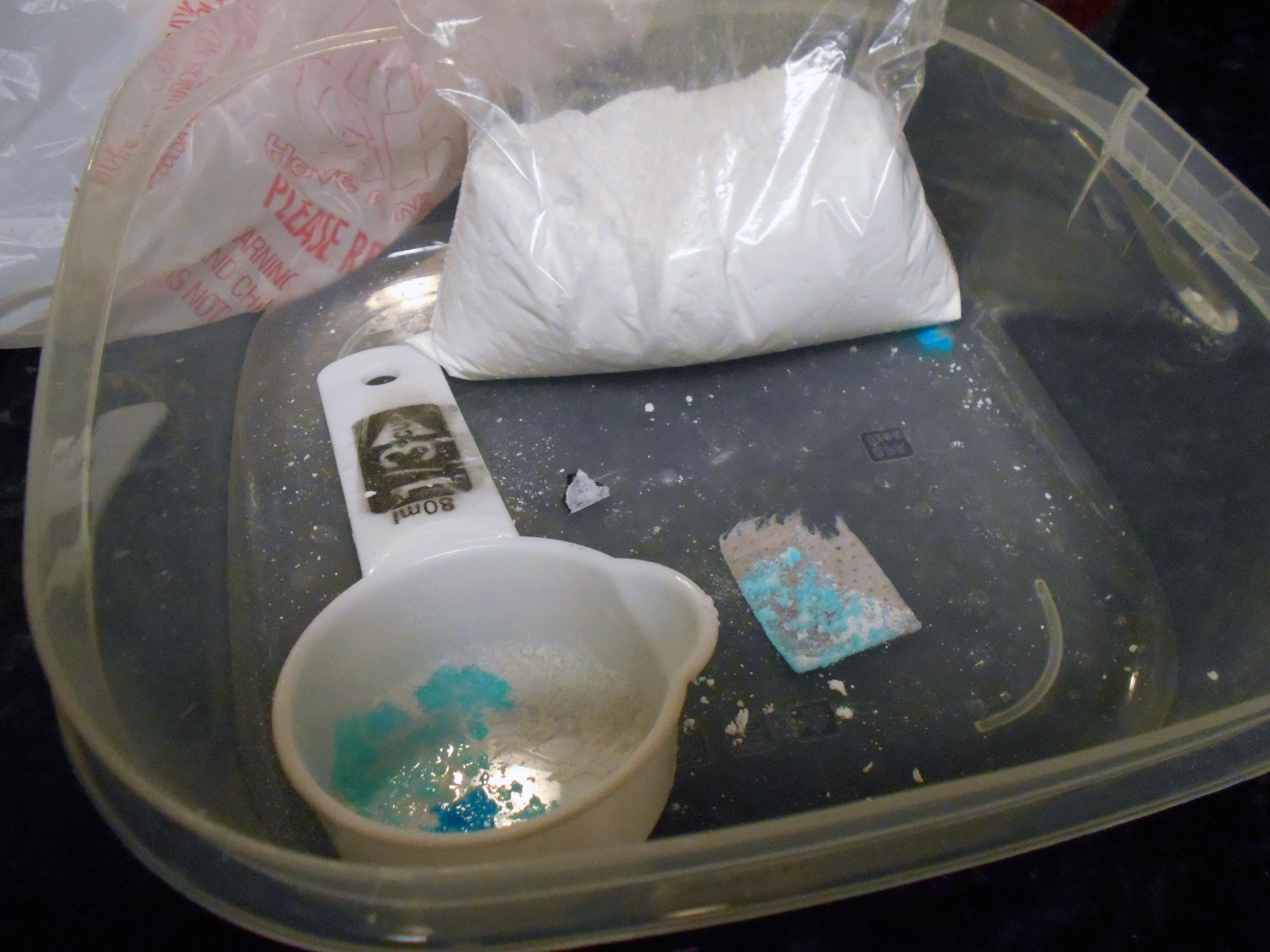

Warn patients about illicit drugs doctored with fentanyl

Fentanyl is now threatening overdoses in patients exposed to essentially any of the full array of recreational drugs – not just opioids – that are being sold illicitly, according to an overview of the problem presented at the virtual Psychopharmacology Update presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

“Fentanyl can now be found in cocaine and methamphetamine. At this point, there is really no way to predict what is in a [street] drug,” Edwin A. Salsitz, MD, said at the meeting, sponsored by Medscape Live. He is associate clinical professor of medicine who works in the division of chemical dependency at Mount Sinai Beth Israel Medical Center in New York.

As proof of the frequency with which fentanyl is now being used as an additive, most patients with a drug use disorder, regardless of their drug of choice, are testing positive for fentanyl at Dr. Salsitz’s center. Many of those with positive fentanyl tests are unaware that their drugs had been doctored with this agent.

Relative to drugs sold as an opioid, such as heroin or oxycodone, the fentanyl dose in nonopioid drugs is typically more modest, but Dr. Salsitz pointed out that those expecting cocaine or methamphetamine often “have no heroin tolerance, so they are more vulnerable” to the adverse effects of fentanyl, including an overdose.

Although opioid tolerance might improve the chances for surviving a fentanyl overdose, the toxicology of fentanyl is not the same as other opioids. Death from heroin is typically a result of respiratory depression, but the onset is relatively slow, providing a greater opportunity to administer a reversal agent, such as naloxone.

Fentanyl not only produces respiratory depression but skeletal muscle rigidity. The rapid onset of “wooden chest syndrome” can occur within minutes, making the opportunity for intervention much smaller, Dr. Salsitz said.

To illustrate the phenomenon, Dr. Salsitz recounted a case.

After an argument with his mother, a 26-year-old male with a long history of intravenous drug use went to his bedroom. His mother, responding to the sound of a loud thud, rushed to the bedroom to find her son on the floor with a needle still in his arm. Resuscitation efforts by the mother and by the emergency responders, who arrived quickly, failed.

“The speed of his death made it clear that it was fentanyl related, and the postmortem toxicology confirmed that the exposure involved both heroin and fentanyl,” Dr. Salsitz said.

After the first wave of deaths in the opioid epidemic, which was attributed to inappropriate use of prescription opioids, the second wave was driven by heroin. In that wave, patients who became addicted to prescription opioids but were having more difficulty gaining access to them, turned to far cheaper and readily available street heroin. The third wave, driven by fentanyl, began several years ago when sellers of heroin began adding this synthetic opioid, which is relatively cheap, to intensify the high.

It is not expected to end quickly. The fentanyl added to heroin was never a prescription version. Rather, Dr. Salsitz said, it is synthesized in laboratories in China, Mexico, and the United States. It is relatively easy to produce and compact, which makes it easy to transport.

Exacerbating the risks that fentanyl poses when added to street drugs, even more potent versions, such as carfentanil, are also being added to cocaine, methamphetamines, and other nonopioid illicit drugs. When compared on a per-milligram basis, fentanyl is about 100 times more potent than heroin, but carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl, according to Dr. Salsitz.

When the third wave of deaths in the opioid epidemic began around 2013, prescriptions of fentanyl, like many other opioid-type therapies were declining. The “perfect storm” that initiated the opioid epidemic was a product of intense focus on pain control and a misperception that prescription opioids posed a low risk of abuse potential, Dr. Salsitz said. By the time fentanyl was driving opioid deaths, the risks of opioids were widely appreciated and their use for prescription analgesia was declining.

Citing several cases, Dr. Salsitz noted that only 20 years after clinicians were being successfully sued for not offering enough analgesia, they were now going to jail for prescribing these drugs too liberally.

According to Dr. Salsitz, While psychiatrists might not have a role in this issue, Dr. Salsitz did see a role for these specialists in protecting patients from the adverse consequences of using illicit drugs doctored with fentanyl.

Noting that individuals with psychiatric disorders are more likely than the general population to self-medicate with drugs purchased illegally, Dr. Salsitz encouraged psychiatrists “to get involved” in asking about drug use and counseling patients on the risks of fentanyl substitution or additives.

“The message is that no one knows what are in these drugs, anymore,” he said.

In addition to making patients aware that many street drugs are now contaminated with fentanyl, Dr. Salsitz provided some safety tips. He suggested instructing patients to take a low dose of any newly acquired drug to gauge its effect, to avoid taking drugs alone, and to avoid mixing drugs. He also recommended using rapid fentanyl test strips in order to detect fentanyl contamination.

Even for the many psychiatrists who do not feel comfortable managing addiction, Dr. Salsitz recommended a proactive approach to address the current threat.

Test strips as an intervention

The seriousness of fentanyl contamination of illicit drugs, including cocaine and methamphetamine, was corroborated by two investigators at the School of Public Health and the Albert Einstein Medical School of Brown University, Providence, R.I. Brandon D.L. Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology in the School of Public Health, called fentanyl-contaminated cannabis “extremely rare,” but he said that it is being found in counterfeit prescription pills as well as in crystal methamphetamine and in both crack and powder cocaine.

He also advocated the use of fentanyl test strips.

“Test strips are an efficient, inexpensive, and effective way to determine whether fentanyl or related analogs are present in illicit drugs,” he said, noting that he is involved in a trial designed to determine whether fentanyl test strips can reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal overdoses.

In a pilot study conducted in Baltimore, 69% of the 103 participants engaged in harm reduction behavior after using a fentanyl test strip and receiving a positive result (Addict Behav. 2020;110:106529). It is notable that 86% of the participants had a least one positive result when using the strips. More than half were surprised by the result.

One of the findings from this study was “that the lasting benefit of fentanyl test strip distribution is the opportunity to engage in discussions around safety and relationship building with historically underserved communities,” said the lead author, Ju Nyeong Park, PhD, assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at Brown University. She moved to Brown after performing this work at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.