User login

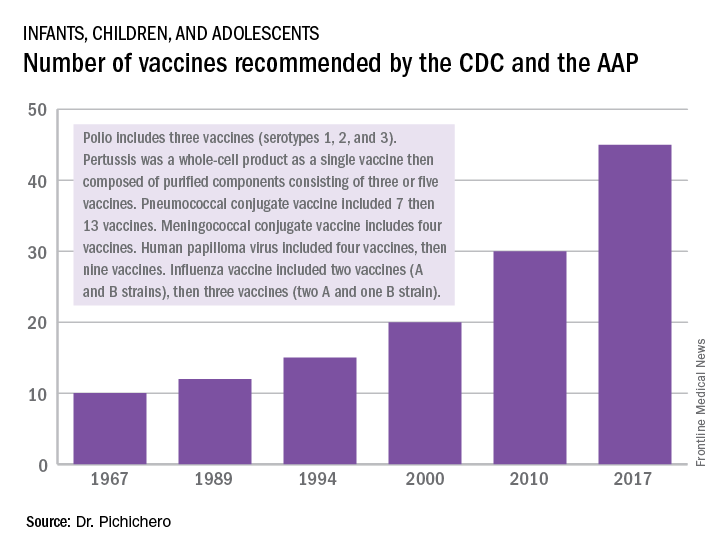

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

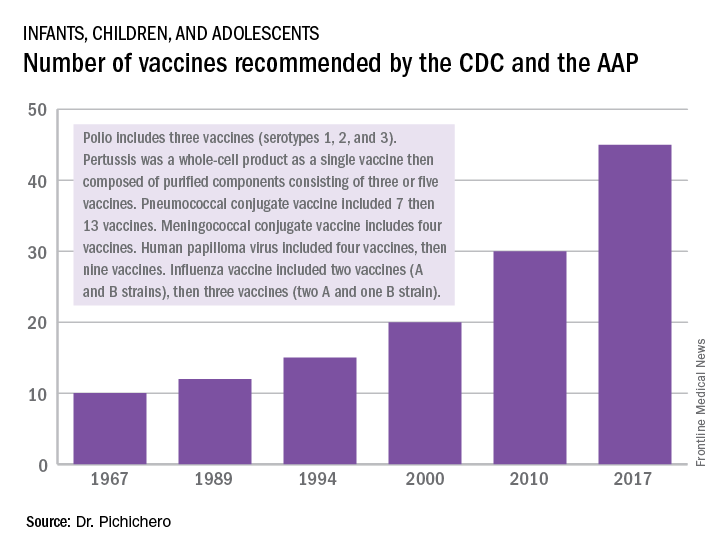

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

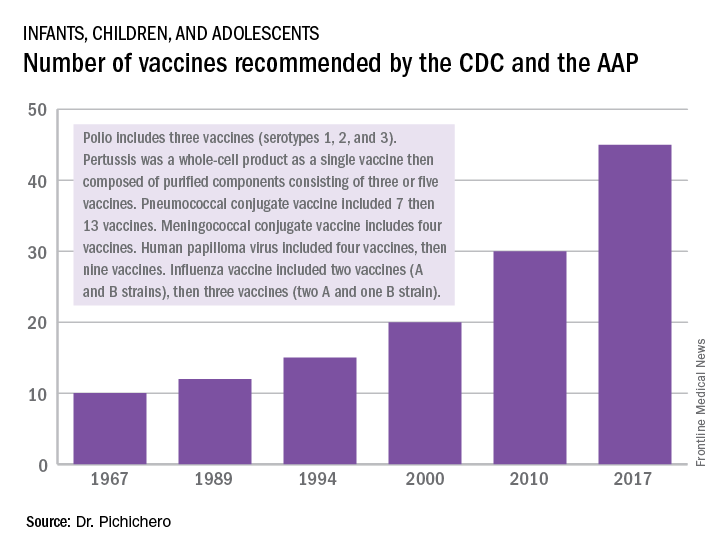

In 1967, pediatric patients were vaccinated routinely against eight diseases with 10 vaccines: smallpox; diphtheria; tetanus and pertussis; polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3; measles; rubella; and mumps. Then in 1989, vaccine discovery took a dramatic upward trend. For the physicians and scientists involved in vaccine discovery, the driving force may have been a passion for scientific discovery and a humanitarian motivation, but what drove this major change in pediatric infectious diseases was economics.

I believe The hiatus of more than 20 years between the introduction of the mumps vaccine in 1967 and that of the Hib vaccine in 1989 in my view was because the economic incentives to develop vaccines were absent. In fact, in the 1970s and early 1980s, vaccine manufacturers were drawing back from making vaccines because they were losing money selling them at a few dollars per dose.

A trailblazing path had been created, and more and more vaccines have been discovered and come to market since then. Combination vaccines and vaccines for adolescents and adults have followed. The biggest blockbuster is Prevnar13 (actually 13 vaccines contained in a single combination), now with annual sales in excess of $7 billion worldwide and growing. Other vaccines with sales of a billion dollars or more are also on the market; anything in excess of $1 billion is considered a blockbuster in the pharmaceutical industry and gets the attention of CEOs (and investors) in a big way.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has received funding awarded to his institution for vaccine research from GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur. Email him at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.