User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Localized Acanthosis Nigricans at the Site of Repetitive Insulin Injections

To the Editor:

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by asymptomatic, hyperpigmented, velvety plaques that can occur anywhere on the body but most often present on the skin of the neck, axillae, groin, and other body folds.1-12 Although there are 5 subtypes, benign AN is the most common and is related to insulin resistance.1-4 Insulin can bind to insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) on keratinocytes, stimulating their proliferation. In type 2 diabetes mellitus, endogenous insulin levels are high enough to bind IGF-1 and activate keratinocytes, leading to the development of AN. Insulin injections have been associated with cutaneous side effects including lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3 Acanthosis nigricans at insulin injection sites is a rare clinical condition.

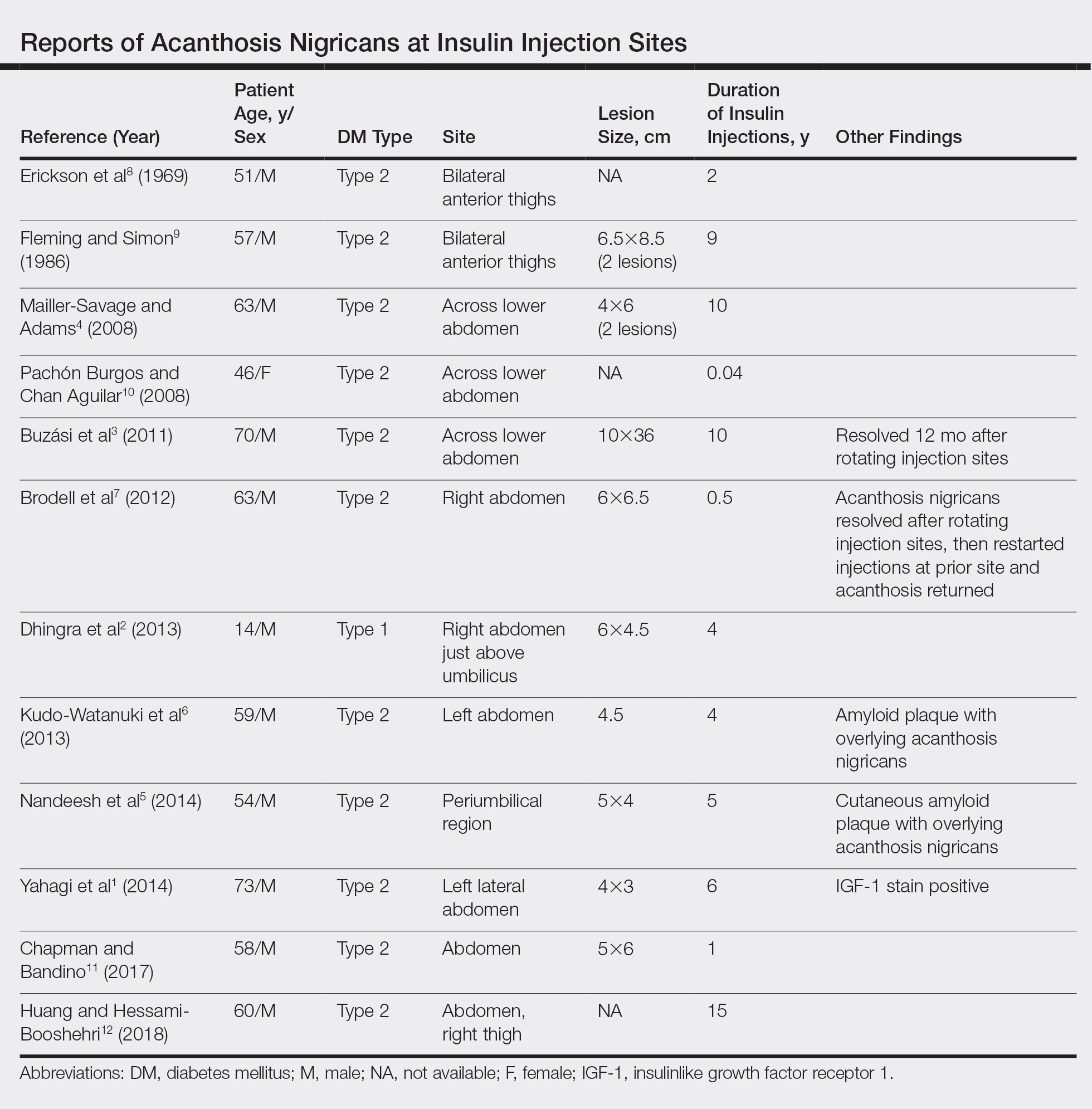

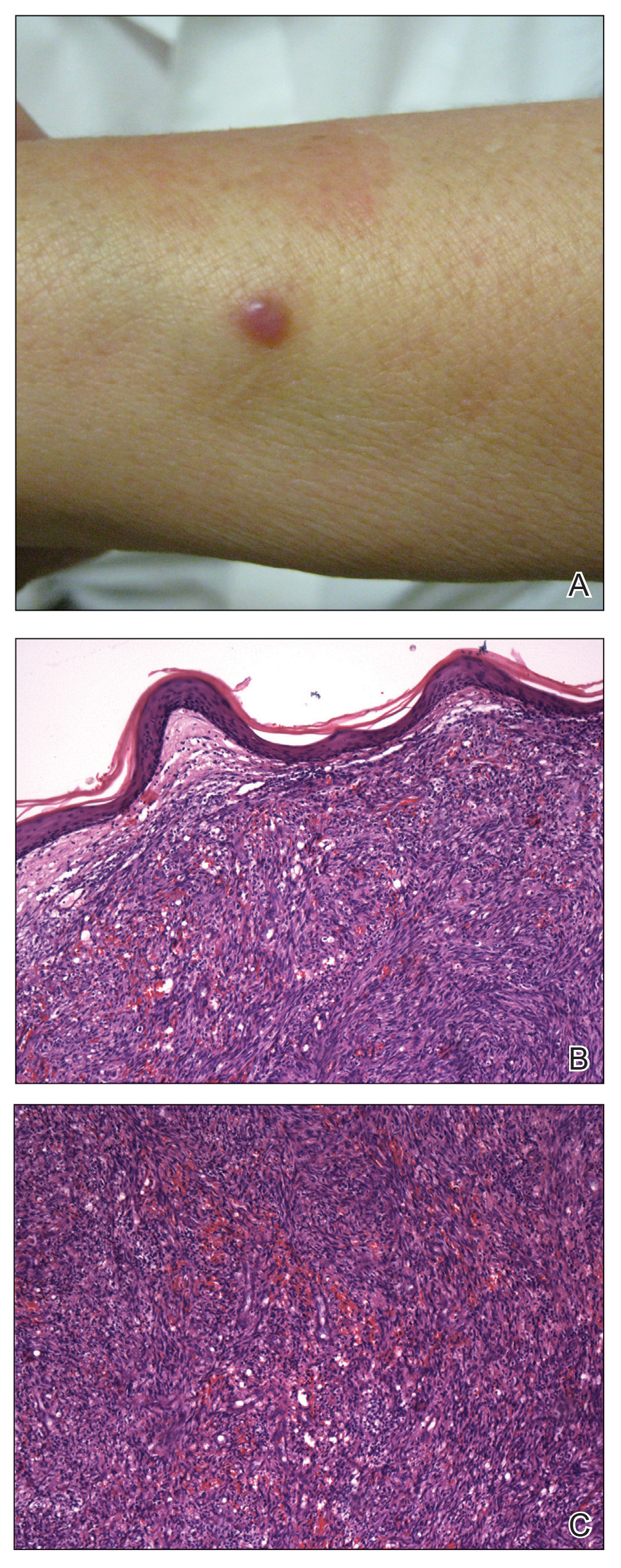

A 64-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growing asymptomatic lesion on the abdomen of 6 years’ duration. He had a 17-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin injections for 14 years after failing oral hypoglycemic agents. The patient reported injecting at the same site on the abdomen for the last 14 years. Physical examination revealed a lichenified, hyperpigmented, verrucous plaque on the lower abdomen under the umbilicus (Figure 1). No similar skin lesions were observed elsewhere on the body. A punch biopsy of the plaque showed hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperpigmentation, which was consistent with AN (Figure 2). The patient was instructed to rotate injection sites and avoid the affected area. Over-the-counter ammonium lactate cream applied twice daily to the affected site also was recommended. After 2 months of treatment with this regimen, the patient reported softening and lightening of the lesion on the abdomen.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE for all English-language studies with human participants using the terms acanthosis nigricans and insulin injections yielded 20 results. Of them, 13 discussed localized AN at insulin injection sites: 12 case reports (Table)1-12 and 1 observational study in a group of diabetic patients.13

In the observational study, 500 diabetic patients were examined for insulin injection-site dermatoses and only 2 had localized injection-site AN. No other information was provided for these 2 patients.13 In the 12 published case reports,1-12 all patients did not rotate sites for their insulin injections and repeatedly injected into the affected area. The abdomen was the most commonly affected site, seen in 83% (10/12) of cases, while 25% (3/12) involved the thighs. All but 1 patient had type 2 diabetes mellitus. In 2 patients, “amyloid” was noted on the biopsy report in addition to changes consistent with AN. At least 2 patients had clearance after rotating injection sites.3,12

It has been suggested that localized AN at insulin injection sites develops through similar mechanisms as benign AN. Contributing factors to the development of benign AN may be IGF-1, fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor.1-3 Insulin is similar in structure to IGF-1 and can bind to IGF-1 receptors at high enough concentrations. Insulinlike growth factor 1 receptors are present on keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which proliferate upon activation, leading to the development of AN.1-3 Localized AN is thought to occur when repetitive insulin at the injection site saturates IGF-1 receptors on local keratinocytes.

Based on our patient and prior reports in the literature, localized AN is an uncommon cutaneous complication of insulin injections. Physicians should ask about repetitive insulin injections in the same site when localized AN occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy. They also should discuss the importance of rotating sites for insulin adminstration to prevent the development of cutaneous complications including AN.

- Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39:5-9.

- Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, et al. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:9.

- Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:E34-E36.

- Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:126-127.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E85-E87.

- Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, et al. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209:934-935.

- Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1054-1056.

- Pachon Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:514.

- Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E163.

- Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190:E1390.

- Sawatkar GU, Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, et al. Spectrum of cutaneous manifestations of type 1 diabetes mellitus in 500 South Asian patients. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1402-1406.

To the Editor:

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by asymptomatic, hyperpigmented, velvety plaques that can occur anywhere on the body but most often present on the skin of the neck, axillae, groin, and other body folds.1-12 Although there are 5 subtypes, benign AN is the most common and is related to insulin resistance.1-4 Insulin can bind to insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) on keratinocytes, stimulating their proliferation. In type 2 diabetes mellitus, endogenous insulin levels are high enough to bind IGF-1 and activate keratinocytes, leading to the development of AN. Insulin injections have been associated with cutaneous side effects including lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3 Acanthosis nigricans at insulin injection sites is a rare clinical condition.

A 64-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growing asymptomatic lesion on the abdomen of 6 years’ duration. He had a 17-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin injections for 14 years after failing oral hypoglycemic agents. The patient reported injecting at the same site on the abdomen for the last 14 years. Physical examination revealed a lichenified, hyperpigmented, verrucous plaque on the lower abdomen under the umbilicus (Figure 1). No similar skin lesions were observed elsewhere on the body. A punch biopsy of the plaque showed hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperpigmentation, which was consistent with AN (Figure 2). The patient was instructed to rotate injection sites and avoid the affected area. Over-the-counter ammonium lactate cream applied twice daily to the affected site also was recommended. After 2 months of treatment with this regimen, the patient reported softening and lightening of the lesion on the abdomen.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE for all English-language studies with human participants using the terms acanthosis nigricans and insulin injections yielded 20 results. Of them, 13 discussed localized AN at insulin injection sites: 12 case reports (Table)1-12 and 1 observational study in a group of diabetic patients.13

In the observational study, 500 diabetic patients were examined for insulin injection-site dermatoses and only 2 had localized injection-site AN. No other information was provided for these 2 patients.13 In the 12 published case reports,1-12 all patients did not rotate sites for their insulin injections and repeatedly injected into the affected area. The abdomen was the most commonly affected site, seen in 83% (10/12) of cases, while 25% (3/12) involved the thighs. All but 1 patient had type 2 diabetes mellitus. In 2 patients, “amyloid” was noted on the biopsy report in addition to changes consistent with AN. At least 2 patients had clearance after rotating injection sites.3,12

It has been suggested that localized AN at insulin injection sites develops through similar mechanisms as benign AN. Contributing factors to the development of benign AN may be IGF-1, fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor.1-3 Insulin is similar in structure to IGF-1 and can bind to IGF-1 receptors at high enough concentrations. Insulinlike growth factor 1 receptors are present on keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which proliferate upon activation, leading to the development of AN.1-3 Localized AN is thought to occur when repetitive insulin at the injection site saturates IGF-1 receptors on local keratinocytes.

Based on our patient and prior reports in the literature, localized AN is an uncommon cutaneous complication of insulin injections. Physicians should ask about repetitive insulin injections in the same site when localized AN occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy. They also should discuss the importance of rotating sites for insulin adminstration to prevent the development of cutaneous complications including AN.

To the Editor:

Acanthosis nigricans (AN) is characterized by asymptomatic, hyperpigmented, velvety plaques that can occur anywhere on the body but most often present on the skin of the neck, axillae, groin, and other body folds.1-12 Although there are 5 subtypes, benign AN is the most common and is related to insulin resistance.1-4 Insulin can bind to insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) on keratinocytes, stimulating their proliferation. In type 2 diabetes mellitus, endogenous insulin levels are high enough to bind IGF-1 and activate keratinocytes, leading to the development of AN. Insulin injections have been associated with cutaneous side effects including lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.3 Acanthosis nigricans at insulin injection sites is a rare clinical condition.

A 64-year-old man presented for evaluation of a growing asymptomatic lesion on the abdomen of 6 years’ duration. He had a 17-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin injections for 14 years after failing oral hypoglycemic agents. The patient reported injecting at the same site on the abdomen for the last 14 years. Physical examination revealed a lichenified, hyperpigmented, verrucous plaque on the lower abdomen under the umbilicus (Figure 1). No similar skin lesions were observed elsewhere on the body. A punch biopsy of the plaque showed hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, acanthosis, and hyperpigmentation, which was consistent with AN (Figure 2). The patient was instructed to rotate injection sites and avoid the affected area. Over-the-counter ammonium lactate cream applied twice daily to the affected site also was recommended. After 2 months of treatment with this regimen, the patient reported softening and lightening of the lesion on the abdomen.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE for all English-language studies with human participants using the terms acanthosis nigricans and insulin injections yielded 20 results. Of them, 13 discussed localized AN at insulin injection sites: 12 case reports (Table)1-12 and 1 observational study in a group of diabetic patients.13

In the observational study, 500 diabetic patients were examined for insulin injection-site dermatoses and only 2 had localized injection-site AN. No other information was provided for these 2 patients.13 In the 12 published case reports,1-12 all patients did not rotate sites for their insulin injections and repeatedly injected into the affected area. The abdomen was the most commonly affected site, seen in 83% (10/12) of cases, while 25% (3/12) involved the thighs. All but 1 patient had type 2 diabetes mellitus. In 2 patients, “amyloid” was noted on the biopsy report in addition to changes consistent with AN. At least 2 patients had clearance after rotating injection sites.3,12

It has been suggested that localized AN at insulin injection sites develops through similar mechanisms as benign AN. Contributing factors to the development of benign AN may be IGF-1, fibroblast growth factor, and epidermal growth factor.1-3 Insulin is similar in structure to IGF-1 and can bind to IGF-1 receptors at high enough concentrations. Insulinlike growth factor 1 receptors are present on keratinocytes and fibroblasts, which proliferate upon activation, leading to the development of AN.1-3 Localized AN is thought to occur when repetitive insulin at the injection site saturates IGF-1 receptors on local keratinocytes.

Based on our patient and prior reports in the literature, localized AN is an uncommon cutaneous complication of insulin injections. Physicians should ask about repetitive insulin injections in the same site when localized AN occurs in patients with diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy. They also should discuss the importance of rotating sites for insulin adminstration to prevent the development of cutaneous complications including AN.

- Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39:5-9.

- Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, et al. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:9.

- Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:E34-E36.

- Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:126-127.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E85-E87.

- Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, et al. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209:934-935.

- Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1054-1056.

- Pachon Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:514.

- Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E163.

- Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190:E1390.

- Sawatkar GU, Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, et al. Spectrum of cutaneous manifestations of type 1 diabetes mellitus in 500 South Asian patients. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1402-1406.

- Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39:5-9.

- Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, et al. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:9.

- Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94:E34-E36.

- Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:126-127.

- Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57:127-129.

- Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, et al. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:25-29.

- Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:E85-E87.

- Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, et al. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209:934-935.

- Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1054-1056.

- Pachon Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:514.

- Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:E163.

- Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190:E1390.

- Sawatkar GU, Kanwar AJ, Dogra S, et al. Spectrum of cutaneous manifestations of type 1 diabetes mellitus in 500 South Asian patients. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1402-1406.

Practice Points

- Benign acanthosis nigricans (AN) is most often related to insulin resistance and presents as asymptomatic, hyperpigmented, velvety plaques on the neck, axillae, groin, and other body folds.

- Benign AN related to insulin resistance occurs when insulin binds to insulinlike growth factor 1 on keratinocytes and stimulates proliferations.

- Although insulin injections have been associated with several cutaneous side effects, including lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, localized AN is an uncommonly reported cutaneous adverse effect.

Not So Classic, Classic Kaposi Sarcoma

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

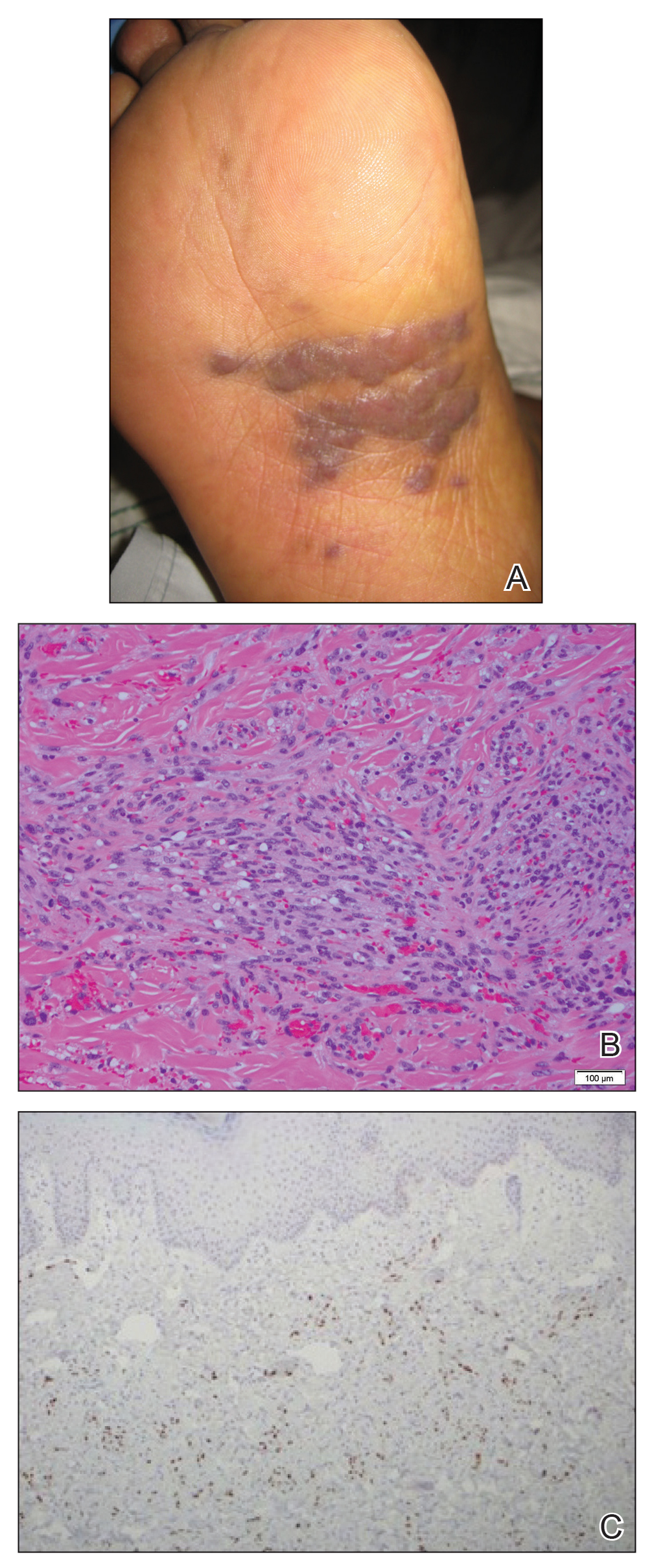

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

To the Editor:

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a lymphatic endothelial cell neoplasm that frequently presents as multiple vascular cutaneous and mucosal nodules.1 The classic KS variant typically is described as the presentation of KS in otherwise healthy elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.2 We present 2 cases of classic KS presenting in Mexican women living in Los Angeles County, California, with atypical clinical features.

A 65-year-old woman of Mexican descent presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of an asymptomatic growth on the right ventral forearm of 4 months’ duration. Biopsy of the lesion demonstrated a spindle cell proliferation suspicious for KS. Physical examination several months following the initial biopsy revealed a mildly indurated scar on the right ventral forearm with an adjacent faintly erythematous papule (Figure 1A). Repeat biopsy revealed a dermal spindle cell proliferation suggestive of KS (Figures 1B and 1C). S-100 and cytokeratin stains were negative, but a latent nuclear antigen 1 stain for human herpesvirus 8 was positive. Human immunodeficiency virus screening also was negative. Given the isolated findings, the oncology service determined that observation alone was the most appropriate management. Over time, the patient developed several similar scattered erythematous papules, and treatment with imiquimod cream 5% was initiated for 1 month without improvement. She was subsequently given a trial of alitretinoin ointment 0.1% twice daily. The lesions improved, and she continues to be well controlled on this topical therapy alone.

A 62-year-old woman of Mexican descent with end-stage cryptogenic cirrhosis was admitted to the hospital for evaluation of transplant candidacy. Dermatology was consulted to assess a 5×3-cm, asymptomatic, solitary, violaceous plaque on the right plantar foot (Figure 2A) with no palpable lymph nodes. Biopsy revealed a dermal proliferation of slit-like vascular channels infiltrating through the collagen and surrounding preexisting vascular spaces and adnexal structures (Figure 2B). Extravasation of erythrocytes and plasma cells also was appreciated. Latent nuclear antigen 1 staining showed strong nuclear positivity consistent with KS (Figure 2C), and a human immunodeficiency virus test and workup for underlying immunosuppression were negative. The patient had no history of treatment with immunosuppressive medications. Further workup revealed involvement of the lymphatic system. The patient was removed from the transplant list and was not a candidate for chemotherapy due to liver failure.

Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm associated with human herpesvirus 8. It typically presents as erythematous to violaceous papules and plaques on the extremities.1 At least 10 morphologic variants of KS have been identified.3 The indolent classic variant of KS most commonly is found in immunocompetent individuals and has been reported to primarily affect elderly men of Jewish or Mediterranean descent.

Epidemiologic analyses of this disease in the South American population are rare. More than 250 cases have been published from South American countries with the largest series published from patients in Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.4 The incidence of classic KS in Peru is 2.54 per 10,000 individuals,5 and the disease has been diagnosed in 1 of 1000 malignant neoplasms at the National Cancer Institute of Colombia.6

A search of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Soft Tissue Pathology registry for classic KS patients (1980-2000) showed that 18% of 438 cases of classic KS were diagnosed in South American Hispanics,7 a percentage that nearly approximates the proportion of patients with KS of Mediterranean descent. Interestingly, in an analysis conducted within Los Angeles County, classic KS was most frequently diagnosed in Jewish, Eastern European–born men who were 55 years or older, followed by European-born women. In this study, white, Spanish, and black populations were diagnosed with classic KS with equal frequency.8

Our 2 cases of classic KS from Los Angeles County had several notable features. Both patients were women from Mexico, a demographic not previously associated with classic KS,8 and they did not have risk factors commonly associated with classic KS. We emphasize that classic KS likely is underreported and understudied in the Mexican and South American populations with need for further epidemiological and clinical analyses.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

- Kaposi M. Idiopathisches multiples Pigmentsarkom der Haut. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1872;4:265-272.

- Akasbi Y, Awada A, Arifi S, et al. Non-HIV Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and therapeutic perspectives. Bull Cancer. 2012;99:92-99.

- Schwartz RA. Kaposi’s sarcoma: an update. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:146-151.

- Mohanna S, Maco V, Bravo F, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma, seroprevalence, and variants of human herpesvirus 8 in South America: a critical review of an old disease. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:2392-2350.

- Mohanna S, Ferrufino JC, Sanchez J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of classic Kaposi’s sarcoma in Peru. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:435-441.

- García A, Olivella F, Valderrama S, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Colombia. Cancer. 1989;64:2393-2398.

- Hiatt KM, Nelson AM, Lichy JH, et al. Classic Kaposi Sarcoma in the United States over the last two decades: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 438 non-HIV related Kaposi Sarcoma patients with comparison to HIV-related Kaposi Sarcoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:572-582.

- Ross RK, Casagrande JT, Dworsky RL, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma in Los Angeles, California. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1985;75:1011-1015.

Practice Points

- Classic Kaposi sarcoma is an indolent neoplasm that can be diagnosed in immunocompetent females of Mexican descent.

- Common diagnoses appearing in skin of color may appear morphologically disparate, and a high index of suspicion is needed for correct diagnosis.

Chronic Diarrhea in an Adolescent Girl With a Genetic Skin Condition

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by a clinical triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa; atopic diathesis; and hair shaft abnormalities, most classically trichorrhexis invaginata.1 Netherton syndrome is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal-type gene, SPINK5, which encodes LEKTI proteins and is found in all stratified epithelia as well as the thymus.2 A lack of functional LEKTI leads to the activation of a cascade of allergy and inflammation as well as uncontrolled proteolytic activity in the stratum corneum, which causes increased desquamation.1

Netherton syndrome presents with serpiginous or circinate scaling plaques with double-edged scale referred to as ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (quiz image). Skin plaques are intensely pruritic and migratory with fluctuating severity. Alternately, patients may have a generalized scaling erythroderma. Infants are at an especially high risk for recurrent infections, sepsis, hypernatremic dehydration, and failure to thrive.2

Netherton syndrome often gradually improves over time, though adults with NS usually have intensely pruritic, localized patches of redness, scaling, or ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. Lichenification and eczematous plaques of the popliteal and antecubital fossae also are common.1 Therapeutic options for NS include emollients, topical steroids, phototherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin for severe cases.3 Because there is skin barrier dysfunction in NS, supratherapeutic serum levels of tacrolimus following topical application have been reported.4 Topical pimecrolimus has been demonstrated as an effective and safer application.5 Trichorrhexis invaginata (also known as bamboo hair) of the hair and eyebrows is a pathognomonic finding in NS, involving invagination of the distal hair shaft into the proximal shaft on light microscopy examination.1

Histopathology is variable and nonspecific with psoriasiform hyperplasia as the most frequent finding. Other histologic findings include incomplete keratinization of the epidermis, incomplete cornification with a severely reduced granular layer, and mild to moderate inflammatory dermal infiltrate.6 LEKTI immunostaining is confirmatory and shows the reduction or complete absence of LEKTI in the granular layer and inner root sheath of follicles.1 Patchy LEKTI staining would be suggestive of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis instead of NS.2

Atopic manifestations include angioedema, urticaria, and anaphylaxis, as well as chronic diarrhea or vomiting due to food allergies.1 Elevated IgE levels for staple foods (eg, milk, wheat), elevated total serum IgE, and eosinophilia frequently are seen.7 Biopsy of the esophagus and colon likely would show mucosal eosinophilia.7,8 Elimination of major food triggers through specific serum IgE testing and oral allergen desensitization can lead to the reduction of digestive symptoms.9 Cisapride and omeprazole are effective treatments for gastroesophageal reflux and poor feeding.8 Biopsy of the intestines in this patient likely would not have shown total villous atrophy, which is rare and primarily reported in infants with NS who have failure to thrive.10 There is a limited association between NS and intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and bacterial overgrowth.

The primary morphology of dyskeratosis follicularis includes keratotic papules developing in sebaceous areas of the skin rather than scaly serpiginous plaques as seen in NS. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a perforating disorder seen in the context of several genetic conditions. It has a serpiginous appearance but, unlike NS, tends to be localized and features keratotic papules rather than patches with scale. Erythema marginatum is an uncommon feature of rheumatic fever and appears as pink annular macules and tends not to be pruritic. Subacute cutaneous lupus does feature scaly annular and serpiginous plaques but features trailing scale without the double-edge appearance of NS and is acquired rather than genetic.

- Hovnanian A. Netherton syndrome: skin inflammation and allergy by loss of protease inhibition. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351:289-300.

- Bitoun E, Micheloni A, Lamant L, et al. LEKTI proteolytic processing in human primary keratinocytes, tissue distribution and defective expression in Netherton syndrome. Human Mol Genet. 2003;12:2417-2430.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Shah KN, Yan AC. Low but detectable serum levels of tacrolimus seen with the use of very dilute, extemporaneously compounded formulations of tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of patients with Netherton syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1362-1363.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Bodemer C, Furio L, et al. Skin biopsy in Netherton syndrome: a histological review of a large series and new findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:83-91.

- Pauluel-Marmont C, Bellon N, Barbet P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis and colonic mucosal eosinophilia in Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:2003-2005.e1.

- Hannula-Jouppi K, Laasanen SL, Heikkila H, et al. IgE allergen component-based profiling and atopic manifestations in patients with Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:985-988.

- Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097-1102.

- Judge MR, Morgan G , Harper JI. A clinical and immunological study of Netherton's syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:615-21.

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by a clinical triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa; atopic diathesis; and hair shaft abnormalities, most classically trichorrhexis invaginata.1 Netherton syndrome is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal-type gene, SPINK5, which encodes LEKTI proteins and is found in all stratified epithelia as well as the thymus.2 A lack of functional LEKTI leads to the activation of a cascade of allergy and inflammation as well as uncontrolled proteolytic activity in the stratum corneum, which causes increased desquamation.1

Netherton syndrome presents with serpiginous or circinate scaling plaques with double-edged scale referred to as ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (quiz image). Skin plaques are intensely pruritic and migratory with fluctuating severity. Alternately, patients may have a generalized scaling erythroderma. Infants are at an especially high risk for recurrent infections, sepsis, hypernatremic dehydration, and failure to thrive.2

Netherton syndrome often gradually improves over time, though adults with NS usually have intensely pruritic, localized patches of redness, scaling, or ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. Lichenification and eczematous plaques of the popliteal and antecubital fossae also are common.1 Therapeutic options for NS include emollients, topical steroids, phototherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin for severe cases.3 Because there is skin barrier dysfunction in NS, supratherapeutic serum levels of tacrolimus following topical application have been reported.4 Topical pimecrolimus has been demonstrated as an effective and safer application.5 Trichorrhexis invaginata (also known as bamboo hair) of the hair and eyebrows is a pathognomonic finding in NS, involving invagination of the distal hair shaft into the proximal shaft on light microscopy examination.1

Histopathology is variable and nonspecific with psoriasiform hyperplasia as the most frequent finding. Other histologic findings include incomplete keratinization of the epidermis, incomplete cornification with a severely reduced granular layer, and mild to moderate inflammatory dermal infiltrate.6 LEKTI immunostaining is confirmatory and shows the reduction or complete absence of LEKTI in the granular layer and inner root sheath of follicles.1 Patchy LEKTI staining would be suggestive of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis instead of NS.2

Atopic manifestations include angioedema, urticaria, and anaphylaxis, as well as chronic diarrhea or vomiting due to food allergies.1 Elevated IgE levels for staple foods (eg, milk, wheat), elevated total serum IgE, and eosinophilia frequently are seen.7 Biopsy of the esophagus and colon likely would show mucosal eosinophilia.7,8 Elimination of major food triggers through specific serum IgE testing and oral allergen desensitization can lead to the reduction of digestive symptoms.9 Cisapride and omeprazole are effective treatments for gastroesophageal reflux and poor feeding.8 Biopsy of the intestines in this patient likely would not have shown total villous atrophy, which is rare and primarily reported in infants with NS who have failure to thrive.10 There is a limited association between NS and intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and bacterial overgrowth.

The primary morphology of dyskeratosis follicularis includes keratotic papules developing in sebaceous areas of the skin rather than scaly serpiginous plaques as seen in NS. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a perforating disorder seen in the context of several genetic conditions. It has a serpiginous appearance but, unlike NS, tends to be localized and features keratotic papules rather than patches with scale. Erythema marginatum is an uncommon feature of rheumatic fever and appears as pink annular macules and tends not to be pruritic. Subacute cutaneous lupus does feature scaly annular and serpiginous plaques but features trailing scale without the double-edge appearance of NS and is acquired rather than genetic.

The Diagnosis: Netherton Syndrome

Netherton syndrome (NS) is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder characterized by a clinical triad of ichthyosis linearis circumflexa; atopic diathesis; and hair shaft abnormalities, most classically trichorrhexis invaginata.1 Netherton syndrome is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the serine peptidase inhibitor Kazal-type gene, SPINK5, which encodes LEKTI proteins and is found in all stratified epithelia as well as the thymus.2 A lack of functional LEKTI leads to the activation of a cascade of allergy and inflammation as well as uncontrolled proteolytic activity in the stratum corneum, which causes increased desquamation.1

Netherton syndrome presents with serpiginous or circinate scaling plaques with double-edged scale referred to as ichthyosis linearis circumflexa (quiz image). Skin plaques are intensely pruritic and migratory with fluctuating severity. Alternately, patients may have a generalized scaling erythroderma. Infants are at an especially high risk for recurrent infections, sepsis, hypernatremic dehydration, and failure to thrive.2

Netherton syndrome often gradually improves over time, though adults with NS usually have intensely pruritic, localized patches of redness, scaling, or ichthyosis linearis circumflexa. Lichenification and eczematous plaques of the popliteal and antecubital fossae also are common.1 Therapeutic options for NS include emollients, topical steroids, phototherapy, and intravenous immunoglobulin for severe cases.3 Because there is skin barrier dysfunction in NS, supratherapeutic serum levels of tacrolimus following topical application have been reported.4 Topical pimecrolimus has been demonstrated as an effective and safer application.5 Trichorrhexis invaginata (also known as bamboo hair) of the hair and eyebrows is a pathognomonic finding in NS, involving invagination of the distal hair shaft into the proximal shaft on light microscopy examination.1

Histopathology is variable and nonspecific with psoriasiform hyperplasia as the most frequent finding. Other histologic findings include incomplete keratinization of the epidermis, incomplete cornification with a severely reduced granular layer, and mild to moderate inflammatory dermal infiltrate.6 LEKTI immunostaining is confirmatory and shows the reduction or complete absence of LEKTI in the granular layer and inner root sheath of follicles.1 Patchy LEKTI staining would be suggestive of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis instead of NS.2

Atopic manifestations include angioedema, urticaria, and anaphylaxis, as well as chronic diarrhea or vomiting due to food allergies.1 Elevated IgE levels for staple foods (eg, milk, wheat), elevated total serum IgE, and eosinophilia frequently are seen.7 Biopsy of the esophagus and colon likely would show mucosal eosinophilia.7,8 Elimination of major food triggers through specific serum IgE testing and oral allergen desensitization can lead to the reduction of digestive symptoms.9 Cisapride and omeprazole are effective treatments for gastroesophageal reflux and poor feeding.8 Biopsy of the intestines in this patient likely would not have shown total villous atrophy, which is rare and primarily reported in infants with NS who have failure to thrive.10 There is a limited association between NS and intestinal metaplasia, intraepithelial lymphocytes, and bacterial overgrowth.

The primary morphology of dyskeratosis follicularis includes keratotic papules developing in sebaceous areas of the skin rather than scaly serpiginous plaques as seen in NS. Elastosis perforans serpiginosa is a perforating disorder seen in the context of several genetic conditions. It has a serpiginous appearance but, unlike NS, tends to be localized and features keratotic papules rather than patches with scale. Erythema marginatum is an uncommon feature of rheumatic fever and appears as pink annular macules and tends not to be pruritic. Subacute cutaneous lupus does feature scaly annular and serpiginous plaques but features trailing scale without the double-edge appearance of NS and is acquired rather than genetic.

- Hovnanian A. Netherton syndrome: skin inflammation and allergy by loss of protease inhibition. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351:289-300.

- Bitoun E, Micheloni A, Lamant L, et al. LEKTI proteolytic processing in human primary keratinocytes, tissue distribution and defective expression in Netherton syndrome. Human Mol Genet. 2003;12:2417-2430.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Shah KN, Yan AC. Low but detectable serum levels of tacrolimus seen with the use of very dilute, extemporaneously compounded formulations of tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of patients with Netherton syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1362-1363.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Bodemer C, Furio L, et al. Skin biopsy in Netherton syndrome: a histological review of a large series and new findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:83-91.

- Pauluel-Marmont C, Bellon N, Barbet P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis and colonic mucosal eosinophilia in Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:2003-2005.e1.

- Hannula-Jouppi K, Laasanen SL, Heikkila H, et al. IgE allergen component-based profiling and atopic manifestations in patients with Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:985-988.

- Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097-1102.

- Judge MR, Morgan G , Harper JI. A clinical and immunological study of Netherton's syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:615-21.

- Hovnanian A. Netherton syndrome: skin inflammation and allergy by loss of protease inhibition. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;351:289-300.

- Bitoun E, Micheloni A, Lamant L, et al. LEKTI proteolytic processing in human primary keratinocytes, tissue distribution and defective expression in Netherton syndrome. Human Mol Genet. 2003;12:2417-2430.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Shah KN, Yan AC. Low but detectable serum levels of tacrolimus seen with the use of very dilute, extemporaneously compounded formulations of tacrolimus ointment in the treatment of patients with Netherton syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1362-1363.

- Yan AC, Honig PJ, Ming ME, et al. The safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus, 1%, cream for the treatment of Netherton syndrome: results from an exploratory study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:57-62.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Bodemer C, Furio L, et al. Skin biopsy in Netherton syndrome: a histological review of a large series and new findings. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:83-91.

- Pauluel-Marmont C, Bellon N, Barbet P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis and colonic mucosal eosinophilia in Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:2003-2005.e1.

- Hannula-Jouppi K, Laasanen SL, Heikkila H, et al. IgE allergen component-based profiling and atopic manifestations in patients with Netherton syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:985-988.

- Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1097-1102.

- Judge MR, Morgan G , Harper JI. A clinical and immunological study of Netherton's syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:615-21.

A 17-year-old adolescent girl visited our clinic to establish care for her genetic skin condition. She exhibited red scaly plaques and patches over much of the body surface area consistent with atopic dermatitis but also had areas on the trunk with serpiginous red plaques with scale on the leading and trailing edges. She also noted fragile hair with sparse eyebrows. The patient reported that she had experienced chronic diarrhea and abdominal pain since childhood. She asked if it could be related to her genetic condition.

Unilateral Vesicular Eruption in a Neonate

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

The Diagnosis: Incontinentia Pigmenti

The patient was diagnosed clinically with the vesicular stage of incontinentia pigmenti (IP), a rare, X-linked dominant neuroectodermal dysplasia that usually is lethal in males. The genetic mutation has been identified in the IKBKG gene (inhibitor of nuclear factor κB; formally NEMO), which leads to a truncated and defective nuclear factor κB. Female infants survive and display characteristic findings on examination due to X-inactivation leading to mosaicism.1 Worldwide, there are approximately 27.6 new cases of IP per year. Although it is heritable, the majority (65%-75%) of cases are due to sporadic mutations, with the remaining minority (25%-35%) representing familial disease.1

Cutaneous findings of IP classically progress through 4 stages, though individual patients often do not develop the characteristic lesions of each of the 4 stages. The vesicular stage (stage 1) presented in our patient (quiz image). This stage presents within 2 weeks of birth in 90% of patients and typically disappears when the patient is approximately 4 months of age.1-3 Although the clinical presentation is striking, it is essential to rule out herpes simplex virus infection, which can mimic vesicular IP. Localized herpes simplex virus is most commonly seen in clusters on the scalp and often is not present at birth. Alternatively, IP is most often seen on the extremities in bands or whorls of distribution along Blaschko lines,4 as in this patient.

Stage 2 (the verrucous stage) presents with verrucous papules or pustules in a similar blaschkoid distribution. Areas previously involved in stage 1 are not always the same areas affected in stage 2. Approximately 70% of patients develop stage 2 lesions, usually at 2 to 6 weeks of age.1-3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum presents in the first week of life with pustules often on the trunk or extremities, but these lesions are not confined to Blaschko lines, differentiating it from IP.4

The third stage (hyperpigmented stage) lends the disease its name and occurs in 90% to 95% of patients with IP. Linear and whorled hyperpigmentation develops in early infancy and can either persist or fade by adolescence.1 Pustules and hyperpigmentation in transient neonatal pustular melanosis may be similar to this stage of IP, but the distribution is more variable and progression to other lesions is not seen.5

The fourth and final stage is the hypopigmented stage, whereby blaschkoid linear and whorled lines of hypopigmentation with or without both atrophy and alopecia develop in 75% of patients. This is the last finding, beginning in adolescence and often persisting into adulthood.1 Goltz syndrome is another X-linked dominant disorder with features similar to IP. Verrucous and atrophic lesions along Blaschko lines are reminiscent of the second and fourth stages of IP but are differentiated in Goltz syndrome because they present concurrently rather than in sequential stages such as IP. Similar extracutaneous organs are affected such as the eyes, teeth, and nails; however, Goltz syndrome may be associated with more distinguishing systemic signs such as sweating and skeletal abnormalities.6

Given its unique appearance, physicians usually diagnose IP clinically after identification of characteristic linear lesions along the lines of Blaschko in an infant or neonate. Skin biopsy is confirmatory, which would differ depending on the stage of disease biopsied. The vesicular stage is characterized by eosinophilic spongiosis and is differentiated from other items on the histologic differential diagnosis by the presence of dyskeratosis.7 Genetic testing is available and should be performed along with a physical examination of the mother for counseling purposes.1

Proper diagnosis is critical because of the potential multisystem nature of the disease with implications for longitudinal care and prognosis in patients. As in other neurocutaneous disease, IP can affect the hair, nails, teeth, central nervous system, and eyes. All IP patients receive a referral to ophthalmology at the time of diagnosis for a dilated fundus examination, with repeat examinations every several months initially--every 3 months for a year, every 6 months from 1 to 3 years of age--and annually thereafter. Dental evaluation should occur at 6 months of age or whenever the first tooth erupts.1 Mental retardation, seizures, and developmental delay can occur and usually are evident in the first year of life. Patients should have developmental milestones closely monitored and be referred to appropriate specialists if signs or symptoms develop consistent with neurologic involvement.1

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

- Greene-Roethke C. Incontinentia pigmenti: a summary review of this rare ectodermal dysplasia with neurologic manifestations, including treatment protocols. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:e45-e52.

- Shah KN. Incontinentia pigmenti clinical presentation. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1114205-clinical. Updated March 5, 2019. Accessed August 2, 2019.

- Poziomczyk CS, Recuero JK, Bringhenti L, et al. Incontinentia pigmenti. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:23-36.

- Mathes E, Howard RM. Vesicular, pustular, and bullous lesions in the newborn and infant. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/vesicular-pustular-and-bullous-lesions-in-the-newborn-and-infant. Updated December 3, 2018. Accessed February 20, 2020.

- Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211.

- Temple IK, MacDowall P, Baraitser M, et al. Focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz syndrome). J Med Genet. 1990;27:180-187.

- Ferringer T. Genodermatoses. In: Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al, eds. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:208-213.

A 4-day-old female neonate presented to the dermatology clinic with a vesicular eruption on the left leg of 1 day's duration. The eruption was asymptomatic without any extracutaneous findings. This term infant was born without complication, and the mother denied any symptoms consistent with herpes simplex virus infection. Physical examination revealed yellow-red vesicles on an erythematous base in a blaschkoid distribution on the left leg. The rest of the examination was unremarkable. Herpes simplex virus polymerase chain reaction testing was negative.

CUTIS Celebrates 55 Years

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

Bleeding Hand Mass in an Older Man

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Angiosarcoma

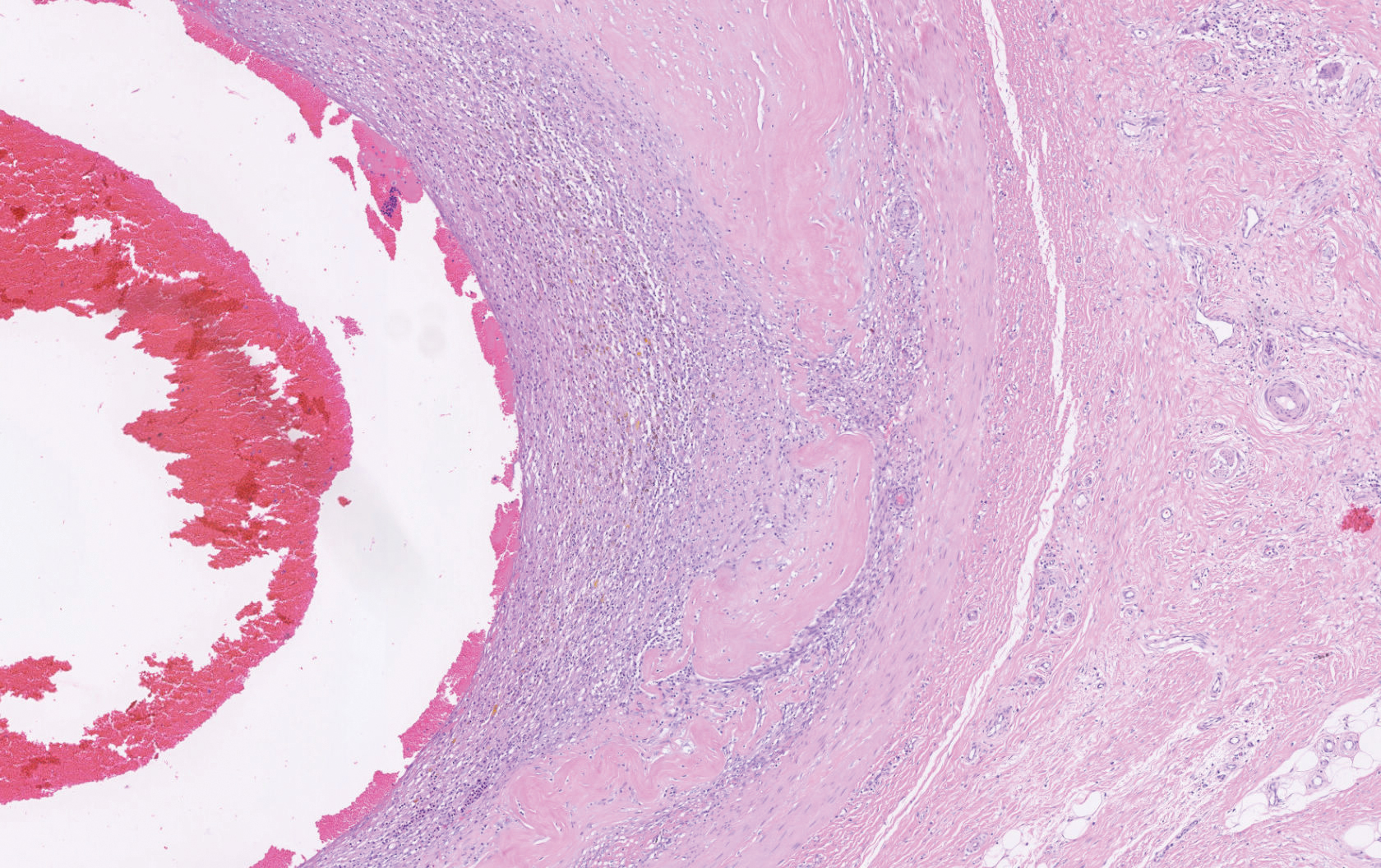

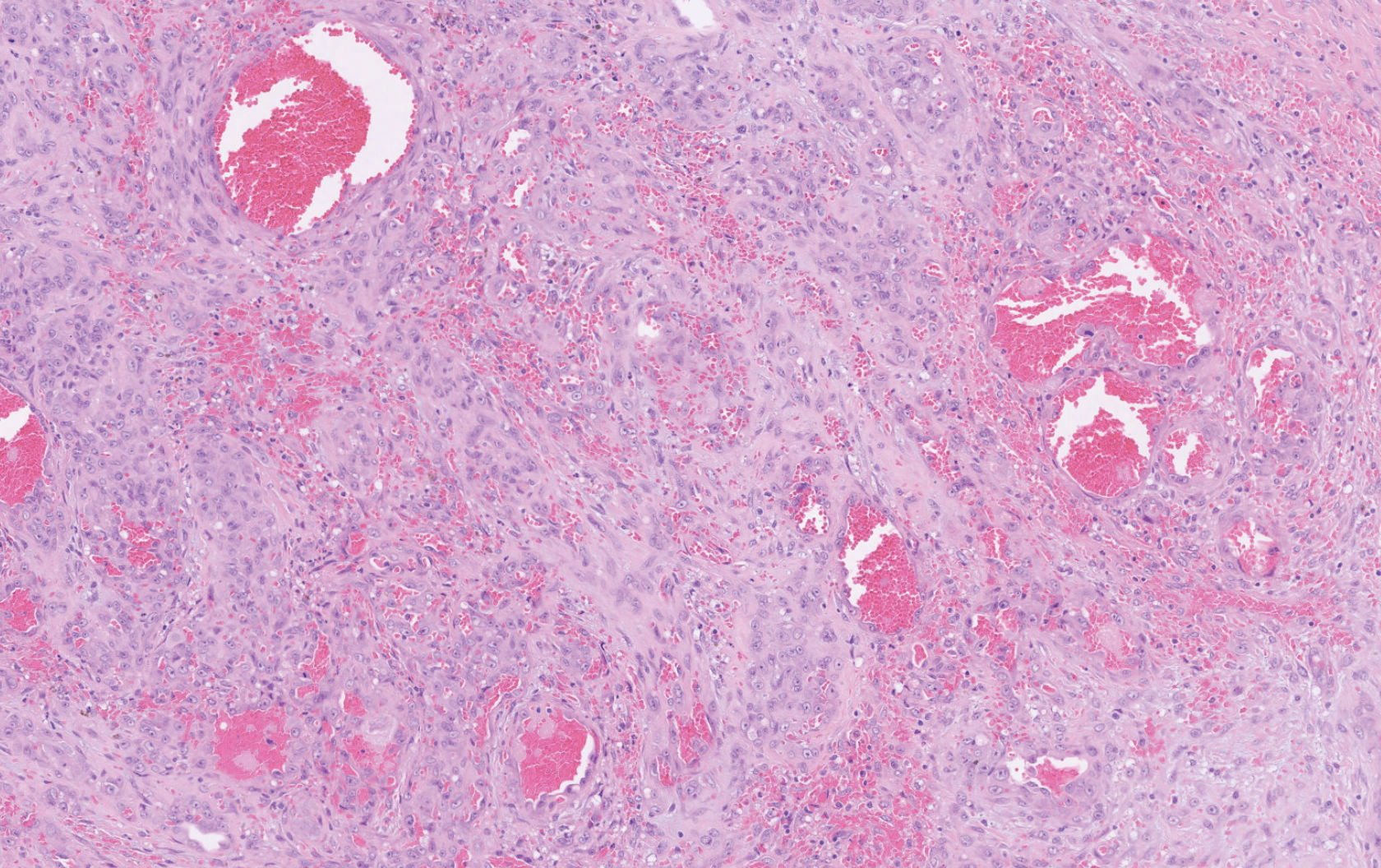

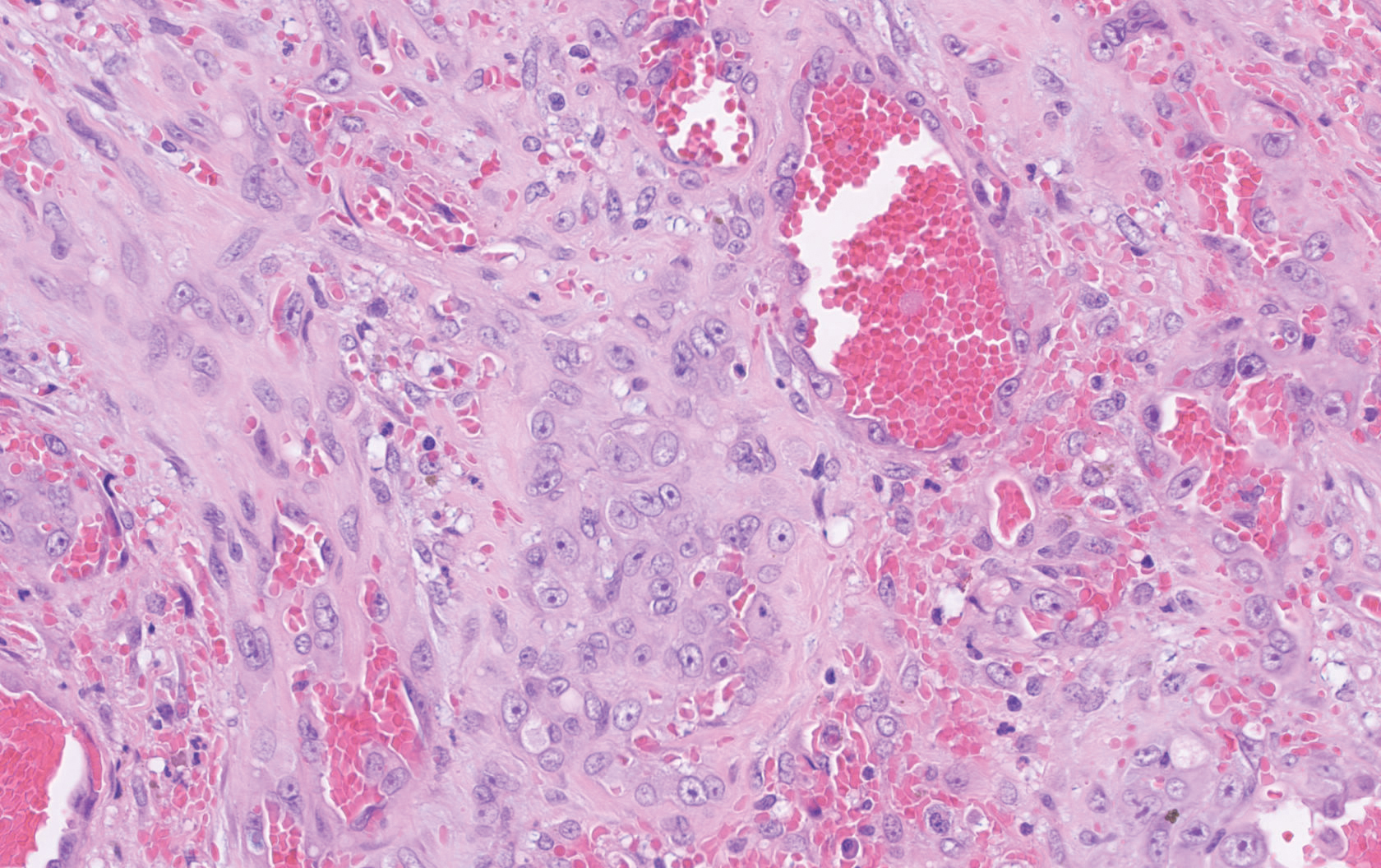

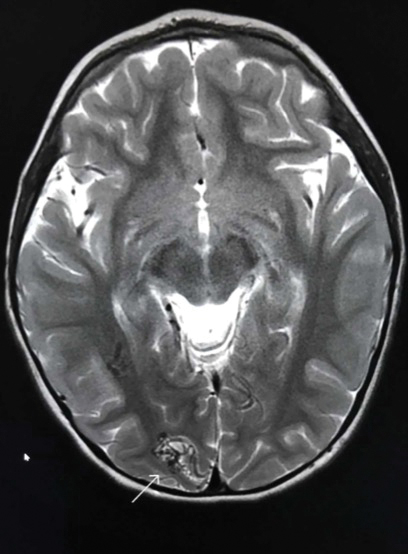

Histopathology showed a large soft-tissue neoplasm with extensive hemorrhage (Figure 1). The epithelioid angiosarcoma (EA) consisted mostly of irregular slit-shaped vessels lined by sheets of atypical endothelial cells (Figure 2). At higher-power magnification, the cellular atypia was prominent and diffuse (Figure 3). Immunostaining of the tumor cells showed positive uptake for CD31, confirming vascular origin (Figure 4). Other vascular markers, including CD34 and factor VIII, as well as nuclear positivity for the erythroblast transformation-specific transcription factor gene, ERG, can be demonstrated by EA. Irregular, smooth muscle actin-positive spindle cells are distributed around some of the vessels. The human herpesvirus 8 stain is negative.

Compared to classic angiosarcomas, EAs have a predilection for the extremities rather than the head and scalp. Histopathologically, the cells are epithelioid and are strongly positive for vimentin and CD31, in addition to factor VIII, friend leukemia integration 1 transcription factor, and CD34.1,2 In contrast, epithelioid sarcomas more typically are seen in younger adults and less likely to be CD31 positive.3 An epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is more focal in cellular atypia and forms small nests and trabeculae rather than sheets of atypical cells. Melanoma cells stain positive for human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, and S-100 but not for CD31.3 Glomangiosarcomas typically stain positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin.4

Epithelioid angiosarcomas are rare and aggressive malignancies of endothelial origin.3 They are more prevalent in men and have a peak incidence in the seventh decade of life. They most commonly occur in the deep soft tissues of the extremities but have been reported to form in a variety of primary sites, including the skin, bones, thyroid, and adrenal glands.3