User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Reducing the Cost of Dermatology Residency Applications: An Applicant’s Perspective

Another Match Day is approaching. Students find themselves paying more each year to apply to one of the most competitive fields, while program directors struggle to sort through hundreds of stellar applications to invite a handful of candidates for interviews. Estimates place the cost of the application process at $5 million in total for all medical school seniors, or roughly $10,000 per applicant.1 Approximately 60% of these costs occur during the interview process.1,2 In an era in which students routinely graduate medical school with hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, these costs must be addressed as soon as possible.

This problem is not unique to dermatology; otolaryngology, another especially competitive field, has considered various changes to the match process based on applicants’ feedback.3 As an applicant during the 2018-2019 match cycle for dermatology, I offer 2 solutions that are a starting point aimed at streamlining the application process for both applicants and program directors: regional interview coordination and a cap on the number of residency applications.

Regional Interview Coordination

Regional interview coordination would reduce travel costs and facilitate greater predictability in scheduling clinical rotations. In the current climate, it is not uncommon for applicants to make multiple cross-country round trips in the same week, especially given that the interview season for dermatology, including interviews for preliminary programs, now ranges from mid-October to early February. Although affluent applicants may not be concerned with financial costs of frequent travel, all applicants face travel inconveniences that could be mitigated through regional coordination. For example, an applicant invited to multiple interviews in the New York City area could reserve a room in a single hotel over a period of several days. During each interview day, he/she could travel back and forth from that accommodation to each institution without needing to bring luggage, worrying about reaching the airport on time, or missing a pre-interview dinner at a program in a faraway city.

Given the amount of coordination required among programs, it may lead to more positive working relationships among regional dermatology programs. One limitation of this approach is that competitive programs may be unwilling to cooperate. If even one program deviates from the interview time frame, it reduces the incentive for others to participate. Programs must be willing to sacrifice short-term autonomy in interview scheduling for their long-term shared interest in reducing the application burden for students, which is known as a commitment problem in game theory, and could be addressed through joint decision-making that incorporates the time frame preferences of all programs as well as binding commitments on interview dates that are decided before the process begins.4 Another limitation is that inclement weather could affect all regional programs simultaneously. In this case, offering interviews via video conference for affected students may be a solution.

Capping the Number of Applications

A second method of reducing interview costs would be capping the number of applications. Although matched seniors applied to a median of 72 programs, the Association of American Medical Colleges suggests that dermatology applicants can maximize their return on investment (ie, ratio of interviews to applications) by sending 35 to 55 applications depending on US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Attending more than 10 interviews does not meaningfully improve the chance of matching.5,6

Programs have limited capacity for interviews and must judiciously allocate invitations based solely on the information provided through the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). Given the competitiveness of dermatology, applicants usually will accept every interview invitation. Therefore, applicants who are not genuinely interested in a program may crowd out others who are interested. In a survey of otolaryngology applicants (N=150), 90.6% of respondents admitted applying to programs in which they had no specific interest, simply to increase their chance of matching.3 Capping application numbers would force students to apply more selectively and enable residencies to gauge students’ true interest more effectively. In contrast to regional interview coordination, this policy change would be easy to enforce. It also may be popular; nearly two-thirds of otolaryngology applicants agreed to a hypothetical cap on residency applications to reduce the burden on students and programs.3

An alternative to a hard cap on applications could be restructuring the ERAS application fee to incentivize students to apply to fewer programs. For example, a flat fee might cover application numbers up to the point of diminishing returns, after which the price per application could increase exponentially. This approach would have a similar effect of a hard cap and cause many students to apply to fewer programs; however, one notable drawback is that highly affluent applicants would simply absorb the extra cost and still gain a competitive advantage in applying to more programs, which might further decrease the number of lower-income individuals successfully matching into dermatology.

A benefit of decreased application numbers to program directors would be giving them more time to conduct a holistic review of applicants, rather than attempting to weed out candidates through arbitrary cutoffs for US Medical Licensing Examination scores or Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership. The ERAS could allow applicants the option of stating preferences for geographic regions, desired fellowships, areas of research interest, and other intangible metrics. Selection committees could filter their candidate search by different variables and then look at each candidate holistically.

Limitations of capping application numbers include the risk that such a cap would harm less-competitive applicants while failing to address the primary cost drivers (ie, travel costs). The specific cap number would be controversial and may need to be adjusted higher for special cases such as couples matching and international applicants, thus making a cap seem arbitrary.

Final Thoughts

The dermatology residency match can be streamlined to the benefit of both applicants and selection committees. Regional interview coordination would reduce both financial and logistical barriers for applicants but may be difficult to enforce without cooperation from multiple programs. Capping the number of applications, either through a hard cap or an increased financial barrier, would be relatively easy to enforce and might empower selection committees to conduct more detailed, holistic reviews of applicants; however, certain types of applicants may find the application limits detrimental to their chances of matching. These policy recommendations are meant to be a starting point for discussion. Streamlining the application process is critical to improving the diversity of dermatology residencies.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

- Tichy AL, Peng DH, Lane AT. Applying for dermatology residency is difficult and expensive. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:696-697.

- Ward M, Pingree C, Laury AM, et al. Applicant perspectives on the otolaryngology residency application process. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:782-787.

- North DC. Institutions and credible commitment. J Inst Theor Econ. 1993;149:11-23.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Apply smart: data to consider when applying to residency. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/filteredresult/apply-smart-data-consider-when-applying-residency/. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of U.S. Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2018 Main Residency Match. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; July 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2019.

Another Match Day is approaching. Students find themselves paying more each year to apply to one of the most competitive fields, while program directors struggle to sort through hundreds of stellar applications to invite a handful of candidates for interviews. Estimates place the cost of the application process at $5 million in total for all medical school seniors, or roughly $10,000 per applicant.1 Approximately 60% of these costs occur during the interview process.1,2 In an era in which students routinely graduate medical school with hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, these costs must be addressed as soon as possible.

This problem is not unique to dermatology; otolaryngology, another especially competitive field, has considered various changes to the match process based on applicants’ feedback.3 As an applicant during the 2018-2019 match cycle for dermatology, I offer 2 solutions that are a starting point aimed at streamlining the application process for both applicants and program directors: regional interview coordination and a cap on the number of residency applications.

Regional Interview Coordination

Regional interview coordination would reduce travel costs and facilitate greater predictability in scheduling clinical rotations. In the current climate, it is not uncommon for applicants to make multiple cross-country round trips in the same week, especially given that the interview season for dermatology, including interviews for preliminary programs, now ranges from mid-October to early February. Although affluent applicants may not be concerned with financial costs of frequent travel, all applicants face travel inconveniences that could be mitigated through regional coordination. For example, an applicant invited to multiple interviews in the New York City area could reserve a room in a single hotel over a period of several days. During each interview day, he/she could travel back and forth from that accommodation to each institution without needing to bring luggage, worrying about reaching the airport on time, or missing a pre-interview dinner at a program in a faraway city.

Given the amount of coordination required among programs, it may lead to more positive working relationships among regional dermatology programs. One limitation of this approach is that competitive programs may be unwilling to cooperate. If even one program deviates from the interview time frame, it reduces the incentive for others to participate. Programs must be willing to sacrifice short-term autonomy in interview scheduling for their long-term shared interest in reducing the application burden for students, which is known as a commitment problem in game theory, and could be addressed through joint decision-making that incorporates the time frame preferences of all programs as well as binding commitments on interview dates that are decided before the process begins.4 Another limitation is that inclement weather could affect all regional programs simultaneously. In this case, offering interviews via video conference for affected students may be a solution.

Capping the Number of Applications

A second method of reducing interview costs would be capping the number of applications. Although matched seniors applied to a median of 72 programs, the Association of American Medical Colleges suggests that dermatology applicants can maximize their return on investment (ie, ratio of interviews to applications) by sending 35 to 55 applications depending on US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Attending more than 10 interviews does not meaningfully improve the chance of matching.5,6

Programs have limited capacity for interviews and must judiciously allocate invitations based solely on the information provided through the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). Given the competitiveness of dermatology, applicants usually will accept every interview invitation. Therefore, applicants who are not genuinely interested in a program may crowd out others who are interested. In a survey of otolaryngology applicants (N=150), 90.6% of respondents admitted applying to programs in which they had no specific interest, simply to increase their chance of matching.3 Capping application numbers would force students to apply more selectively and enable residencies to gauge students’ true interest more effectively. In contrast to regional interview coordination, this policy change would be easy to enforce. It also may be popular; nearly two-thirds of otolaryngology applicants agreed to a hypothetical cap on residency applications to reduce the burden on students and programs.3

An alternative to a hard cap on applications could be restructuring the ERAS application fee to incentivize students to apply to fewer programs. For example, a flat fee might cover application numbers up to the point of diminishing returns, after which the price per application could increase exponentially. This approach would have a similar effect of a hard cap and cause many students to apply to fewer programs; however, one notable drawback is that highly affluent applicants would simply absorb the extra cost and still gain a competitive advantage in applying to more programs, which might further decrease the number of lower-income individuals successfully matching into dermatology.

A benefit of decreased application numbers to program directors would be giving them more time to conduct a holistic review of applicants, rather than attempting to weed out candidates through arbitrary cutoffs for US Medical Licensing Examination scores or Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership. The ERAS could allow applicants the option of stating preferences for geographic regions, desired fellowships, areas of research interest, and other intangible metrics. Selection committees could filter their candidate search by different variables and then look at each candidate holistically.

Limitations of capping application numbers include the risk that such a cap would harm less-competitive applicants while failing to address the primary cost drivers (ie, travel costs). The specific cap number would be controversial and may need to be adjusted higher for special cases such as couples matching and international applicants, thus making a cap seem arbitrary.

Final Thoughts

The dermatology residency match can be streamlined to the benefit of both applicants and selection committees. Regional interview coordination would reduce both financial and logistical barriers for applicants but may be difficult to enforce without cooperation from multiple programs. Capping the number of applications, either through a hard cap or an increased financial barrier, would be relatively easy to enforce and might empower selection committees to conduct more detailed, holistic reviews of applicants; however, certain types of applicants may find the application limits detrimental to their chances of matching. These policy recommendations are meant to be a starting point for discussion. Streamlining the application process is critical to improving the diversity of dermatology residencies.

Another Match Day is approaching. Students find themselves paying more each year to apply to one of the most competitive fields, while program directors struggle to sort through hundreds of stellar applications to invite a handful of candidates for interviews. Estimates place the cost of the application process at $5 million in total for all medical school seniors, or roughly $10,000 per applicant.1 Approximately 60% of these costs occur during the interview process.1,2 In an era in which students routinely graduate medical school with hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt, these costs must be addressed as soon as possible.

This problem is not unique to dermatology; otolaryngology, another especially competitive field, has considered various changes to the match process based on applicants’ feedback.3 As an applicant during the 2018-2019 match cycle for dermatology, I offer 2 solutions that are a starting point aimed at streamlining the application process for both applicants and program directors: regional interview coordination and a cap on the number of residency applications.

Regional Interview Coordination

Regional interview coordination would reduce travel costs and facilitate greater predictability in scheduling clinical rotations. In the current climate, it is not uncommon for applicants to make multiple cross-country round trips in the same week, especially given that the interview season for dermatology, including interviews for preliminary programs, now ranges from mid-October to early February. Although affluent applicants may not be concerned with financial costs of frequent travel, all applicants face travel inconveniences that could be mitigated through regional coordination. For example, an applicant invited to multiple interviews in the New York City area could reserve a room in a single hotel over a period of several days. During each interview day, he/she could travel back and forth from that accommodation to each institution without needing to bring luggage, worrying about reaching the airport on time, or missing a pre-interview dinner at a program in a faraway city.

Given the amount of coordination required among programs, it may lead to more positive working relationships among regional dermatology programs. One limitation of this approach is that competitive programs may be unwilling to cooperate. If even one program deviates from the interview time frame, it reduces the incentive for others to participate. Programs must be willing to sacrifice short-term autonomy in interview scheduling for their long-term shared interest in reducing the application burden for students, which is known as a commitment problem in game theory, and could be addressed through joint decision-making that incorporates the time frame preferences of all programs as well as binding commitments on interview dates that are decided before the process begins.4 Another limitation is that inclement weather could affect all regional programs simultaneously. In this case, offering interviews via video conference for affected students may be a solution.

Capping the Number of Applications

A second method of reducing interview costs would be capping the number of applications. Although matched seniors applied to a median of 72 programs, the Association of American Medical Colleges suggests that dermatology applicants can maximize their return on investment (ie, ratio of interviews to applications) by sending 35 to 55 applications depending on US Medical Licensing Examination scores. Attending more than 10 interviews does not meaningfully improve the chance of matching.5,6

Programs have limited capacity for interviews and must judiciously allocate invitations based solely on the information provided through the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS). Given the competitiveness of dermatology, applicants usually will accept every interview invitation. Therefore, applicants who are not genuinely interested in a program may crowd out others who are interested. In a survey of otolaryngology applicants (N=150), 90.6% of respondents admitted applying to programs in which they had no specific interest, simply to increase their chance of matching.3 Capping application numbers would force students to apply more selectively and enable residencies to gauge students’ true interest more effectively. In contrast to regional interview coordination, this policy change would be easy to enforce. It also may be popular; nearly two-thirds of otolaryngology applicants agreed to a hypothetical cap on residency applications to reduce the burden on students and programs.3

An alternative to a hard cap on applications could be restructuring the ERAS application fee to incentivize students to apply to fewer programs. For example, a flat fee might cover application numbers up to the point of diminishing returns, after which the price per application could increase exponentially. This approach would have a similar effect of a hard cap and cause many students to apply to fewer programs; however, one notable drawback is that highly affluent applicants would simply absorb the extra cost and still gain a competitive advantage in applying to more programs, which might further decrease the number of lower-income individuals successfully matching into dermatology.

A benefit of decreased application numbers to program directors would be giving them more time to conduct a holistic review of applicants, rather than attempting to weed out candidates through arbitrary cutoffs for US Medical Licensing Examination scores or Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society membership. The ERAS could allow applicants the option of stating preferences for geographic regions, desired fellowships, areas of research interest, and other intangible metrics. Selection committees could filter their candidate search by different variables and then look at each candidate holistically.

Limitations of capping application numbers include the risk that such a cap would harm less-competitive applicants while failing to address the primary cost drivers (ie, travel costs). The specific cap number would be controversial and may need to be adjusted higher for special cases such as couples matching and international applicants, thus making a cap seem arbitrary.

Final Thoughts

The dermatology residency match can be streamlined to the benefit of both applicants and selection committees. Regional interview coordination would reduce both financial and logistical barriers for applicants but may be difficult to enforce without cooperation from multiple programs. Capping the number of applications, either through a hard cap or an increased financial barrier, would be relatively easy to enforce and might empower selection committees to conduct more detailed, holistic reviews of applicants; however, certain types of applicants may find the application limits detrimental to their chances of matching. These policy recommendations are meant to be a starting point for discussion. Streamlining the application process is critical to improving the diversity of dermatology residencies.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

- Tichy AL, Peng DH, Lane AT. Applying for dermatology residency is difficult and expensive. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:696-697.

- Ward M, Pingree C, Laury AM, et al. Applicant perspectives on the otolaryngology residency application process. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:782-787.

- North DC. Institutions and credible commitment. J Inst Theor Econ. 1993;149:11-23.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Apply smart: data to consider when applying to residency. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/filteredresult/apply-smart-data-consider-when-applying-residency/. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of U.S. Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2018 Main Residency Match. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; July 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2019.

- Mansouri B, Walker GD, Mitchell J, et al. The cost of applying to dermatology residency: 2014 data estimates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:754-756.

- Tichy AL, Peng DH, Lane AT. Applying for dermatology residency is difficult and expensive. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:696-697.

- Ward M, Pingree C, Laury AM, et al. Applicant perspectives on the otolaryngology residency application process. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:782-787.

- North DC. Institutions and credible commitment. J Inst Theor Econ. 1993;149:11-23.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Apply smart: data to consider when applying to residency. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-residency/filteredresult/apply-smart-data-consider-when-applying-residency/. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Charting Outcomes in the Match: Characteristics of U.S. Allopathic Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2018 Main Residency Match. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; July 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2019.

Pyoderma Gangrenosum Developing After Chest Tube Placement in a Patient With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

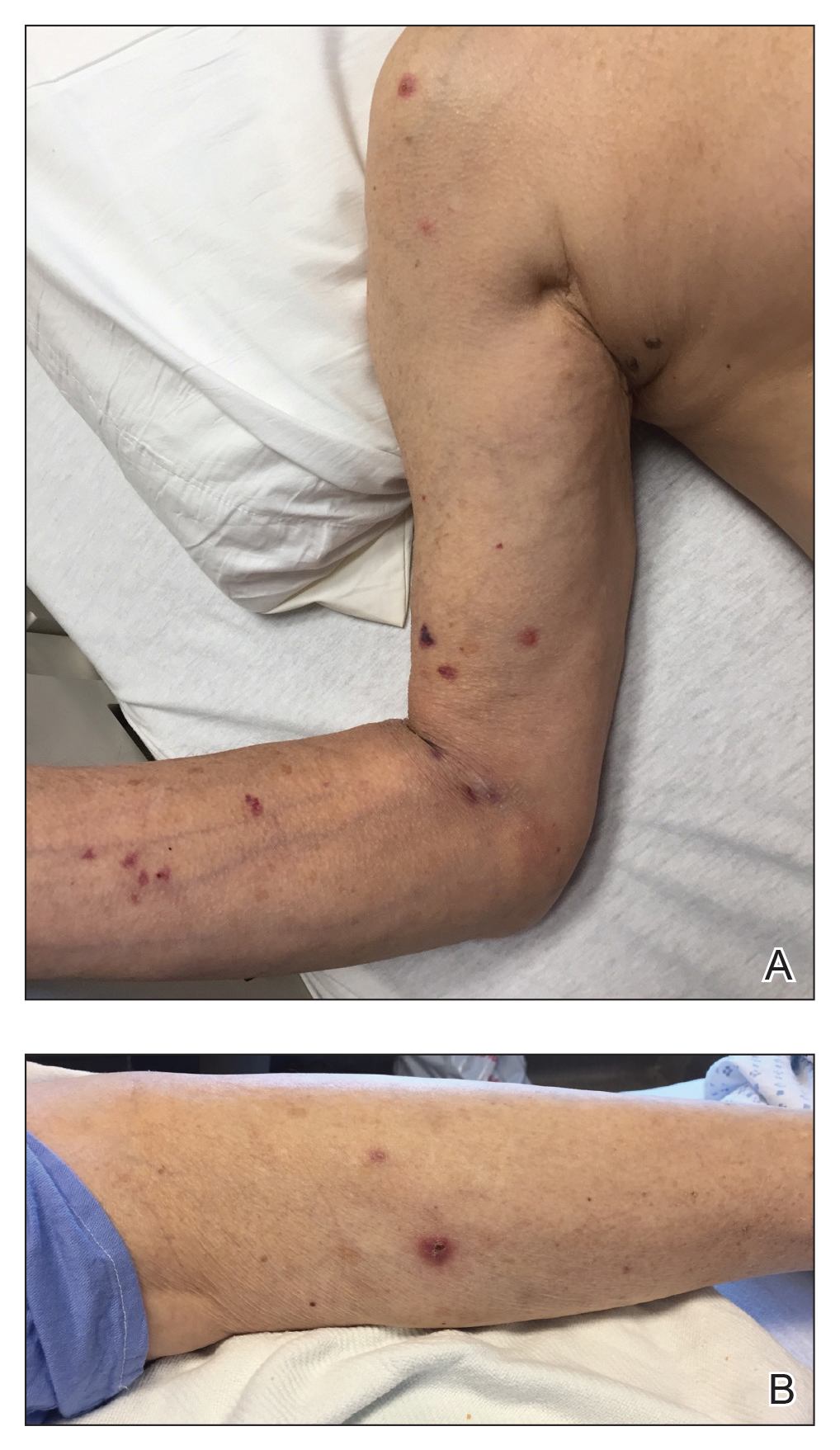

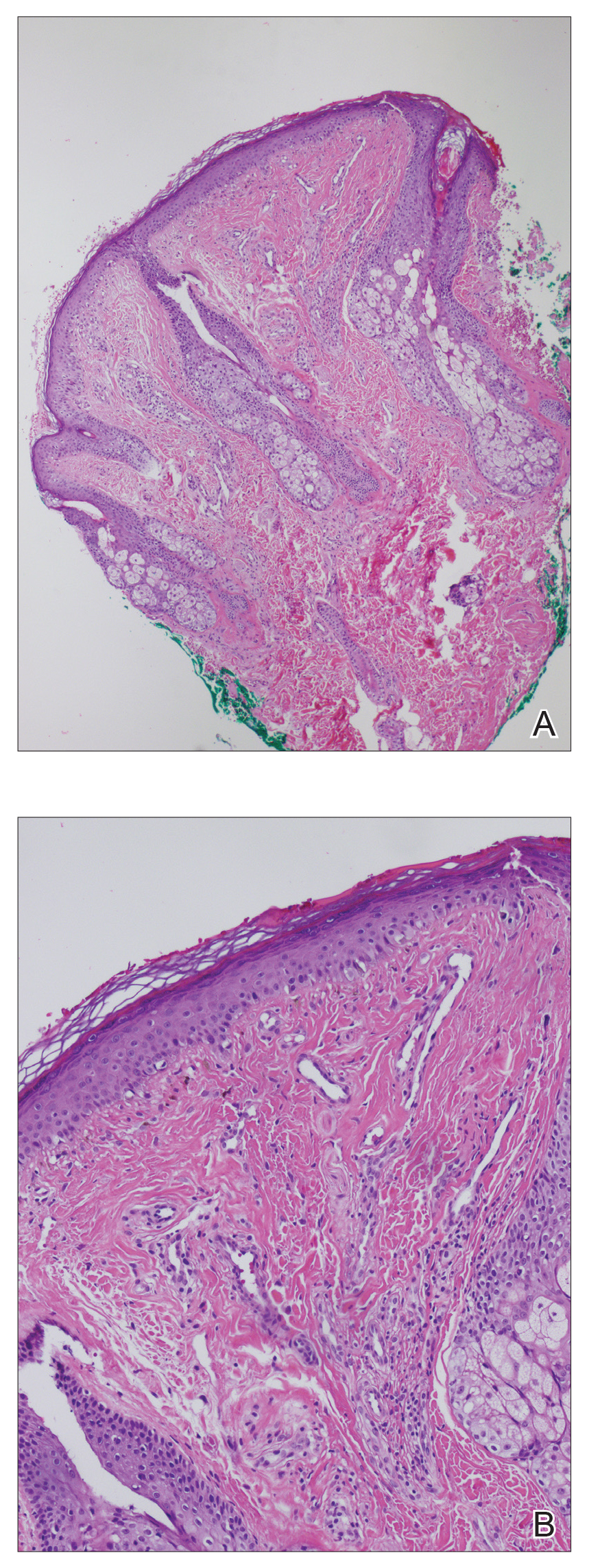

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

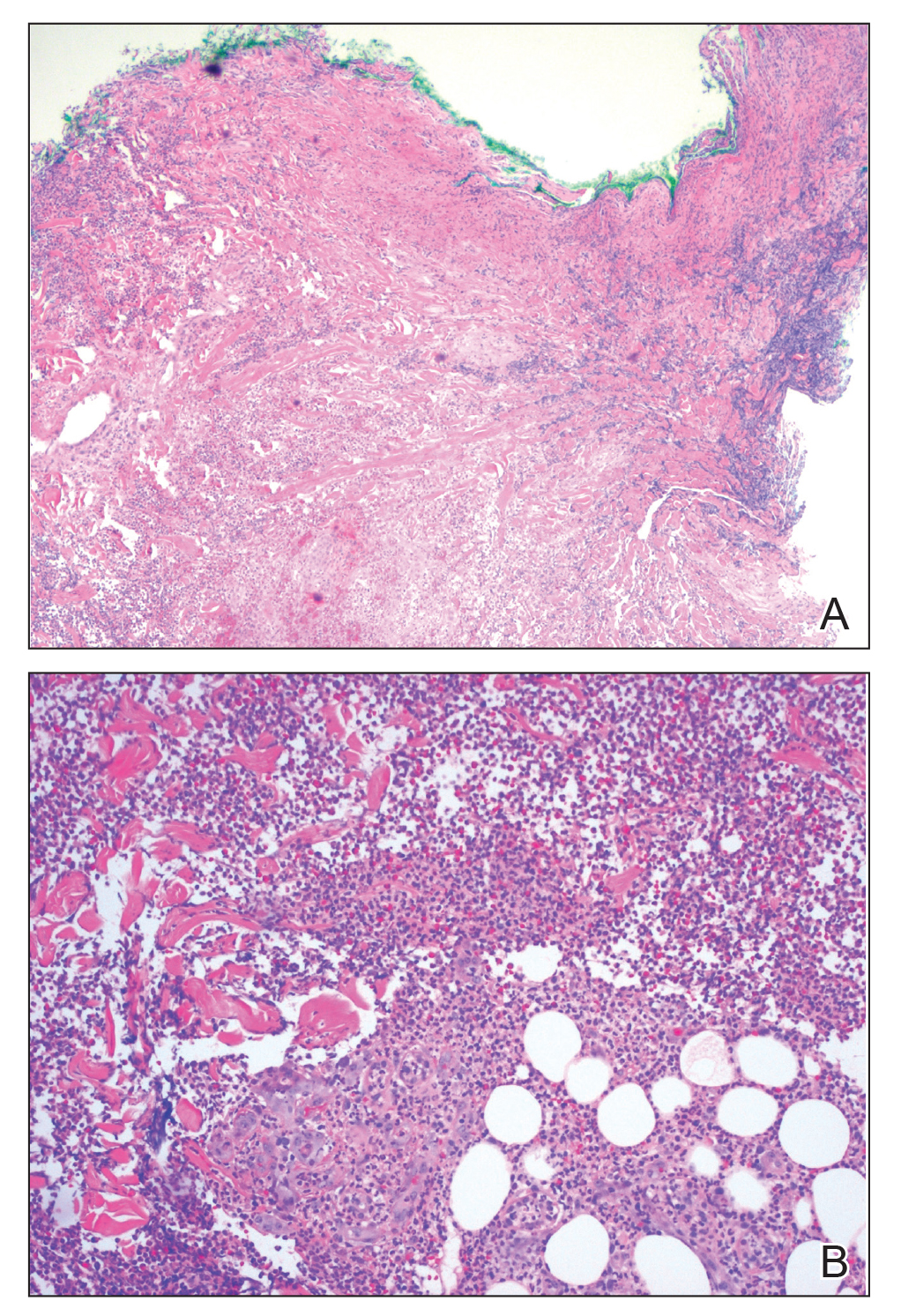

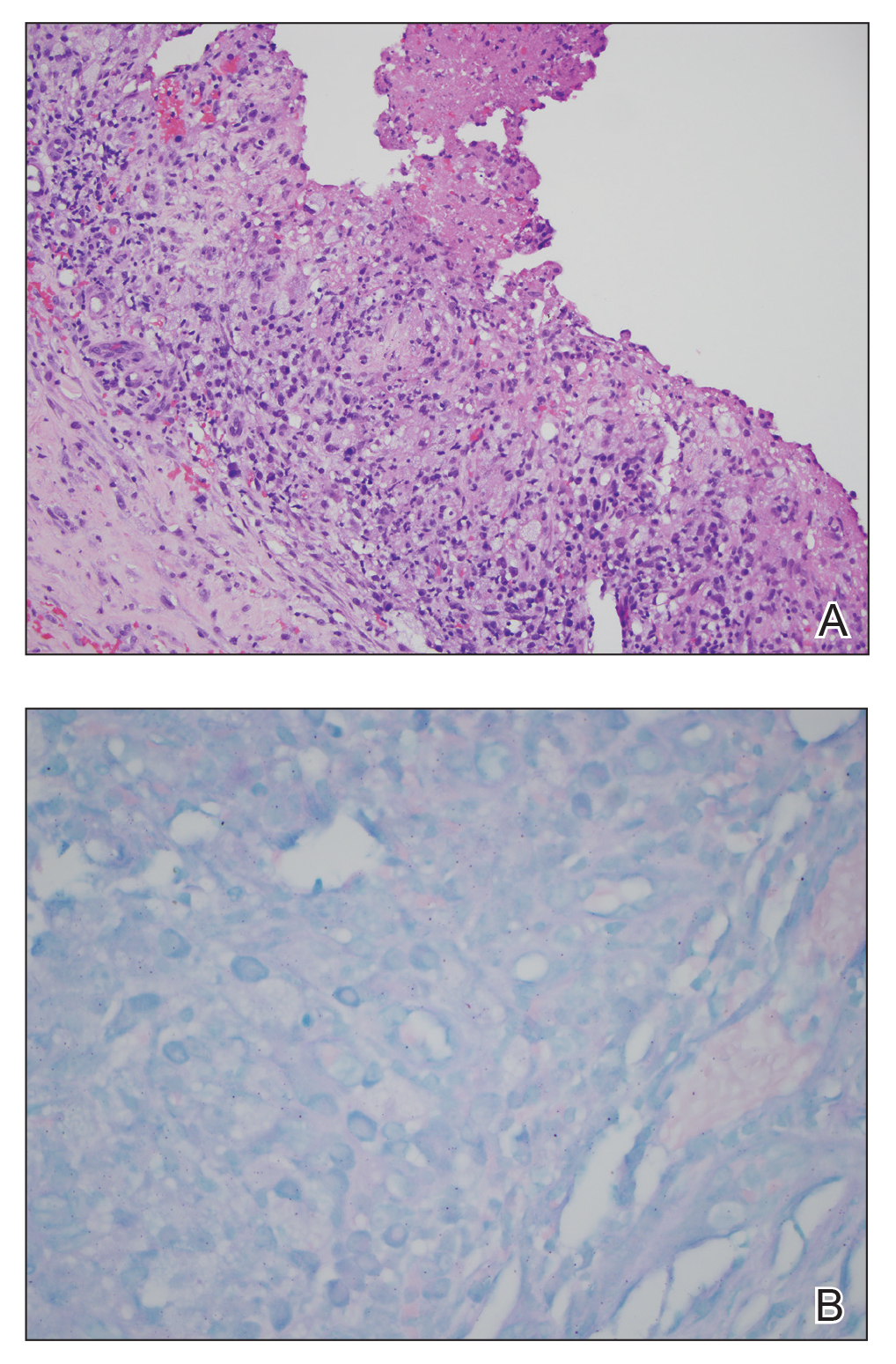

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

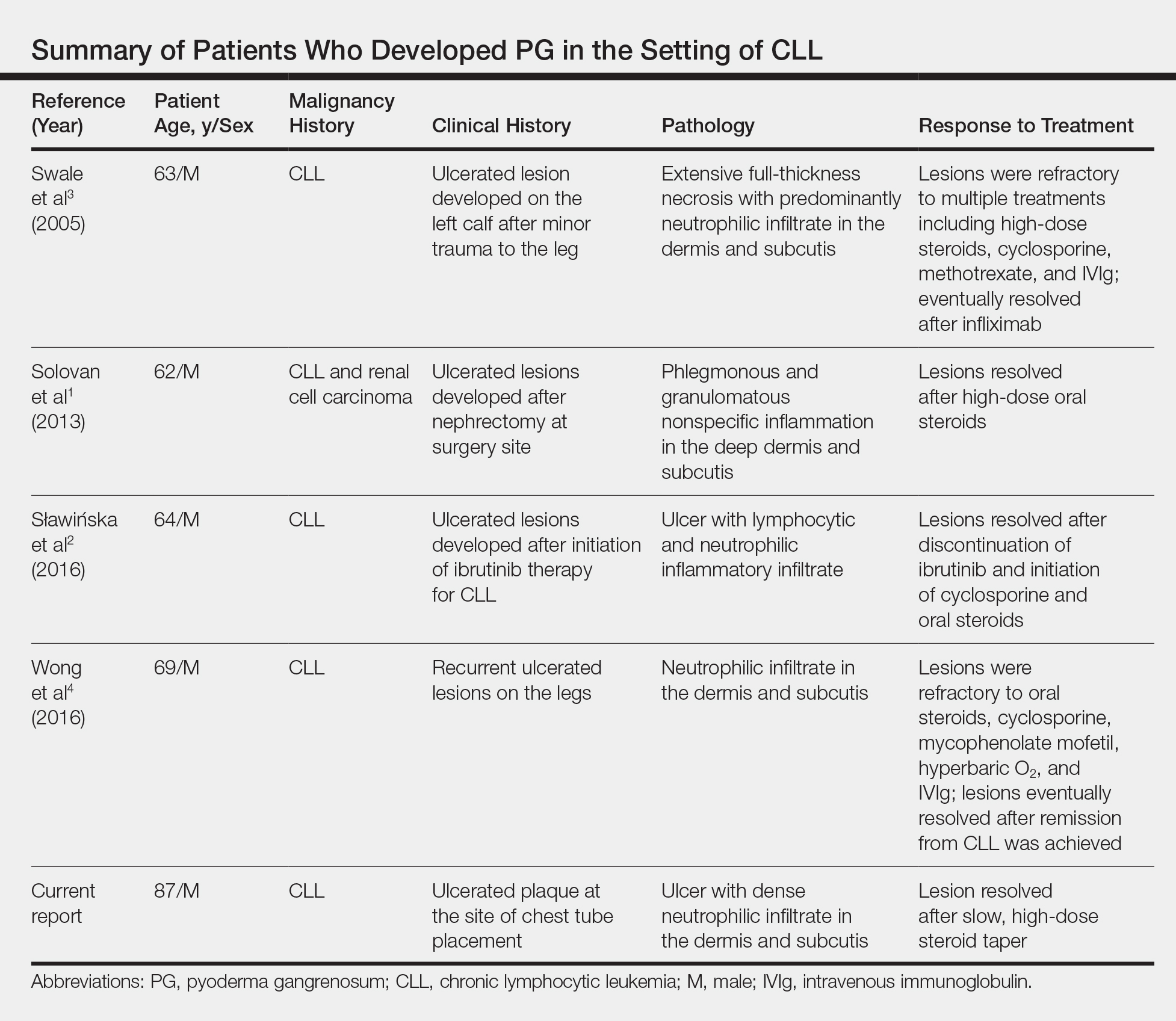

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

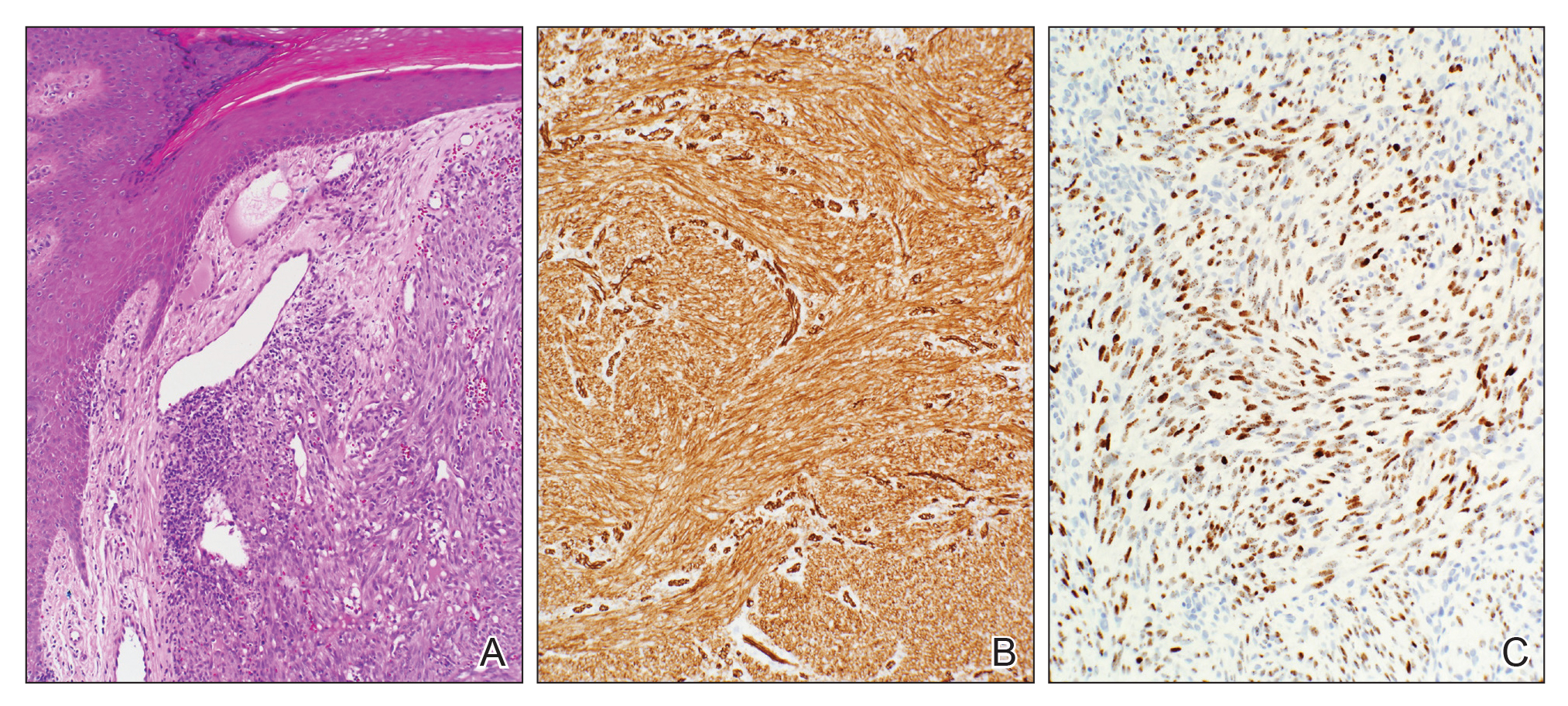

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

Diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis, such as pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), often is challenging at onset because it can be impossible to distinguish clinically and histopathologically from acute infection in an immunosuppressed patient, necessitating a detailed history as well as correlation pathology with microbial tissue cultures. The dermatologist’s ability to distinguish a neutrophilic dermatosis from active infection is of paramount importance because the decision to treat with surgical debridement, in addition to an antibiotic regimen, can have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic dermatosis histologically characterized by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. It is classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease or an underlying hematologic malignancy. Pyoderma gangrenosum in the setting of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is rare, with as few as 4 cases having been described in the literature and only 1 case of PG developing after a surgical procedure.1-4 We present a case of PG occurring at a chest tube site in a patient with CLL. We highlight the challenges and therapeutic importance of arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Case Report

An 87-year-old man with a history of refractory CLL was admitted to the hospital with pneumonia and pleural effusion requiring chest tube placement (left). His most recent therapeutic regimen for CLL was rituximab and bendamustine, which was administered 9 days prior to admission. After removal of the chest tube, an erythematous plaque with central necrosis surrounding the chest tube site developed (Figure 1A). During this time period, the patient had documented intermittent fevers, leukopenia, and neutropenia. Serial blood cultures yielded no growth. Because the patient was on broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, dermatology was consulted for possible angioinvasive fungal infection.

Physical examination revealed an indurated, erythematous-violaceous, targetoid, well-defined, ulcerated plaque with central necrosis on the left side of the chest. Notably, we observed an isolated bulla with an erythematous base within the right antecubital fossa at the site of intravenous placement, suggesting pathergy.

Multiple punch biopsies revealed an ulcer with an underlying dense neutrophilic infiltrate within the dermis and subcutaneous tissues (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, periodic acid–Schiff, and acid-fast bacillus stains were all negative for organisms. Tissue cultures for bacterial, fungal, and acid-fast bacilli revealed no growth. Due to the rapidly expanding nature of the plaque and the possibility of infection despite negative microbial stains and cultures, the patient was scheduled for surgical debridement by the surgical team.

Opportunely, after thoughtful consideration of the clinical history, histopathology, and negative tissue cultures, we made a diagnosis of PG, a condition that would have been further exacerbated by debridement and unimproved with antibiotics. Based on our recommendation, the patient received immunosuppressive treatment with prednisone 60 mg/d and triamcinolone ointment 0.1%. He experienced immediate clinical improvement, allowing him to be discharged to the care of dermatology as an outpatient. He continued to receive a monthly rituximab infusion. We intentionally tapered the patient’s prednisone dosage slowly over 4 months and photodocumented steady improvement with eventual resolution of the PG (Figure 1B).

Comment

Pathogenesis of PG

Pyoderma gangrenosum lies in the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses, which are characterized histologically by a pandermal neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of an infectious cause or true vasculitis. Clinically, PG typically presents as a steadily expanding ulceration with an undermined or slightly raised border, and often is associated with the pathergy phenomenon. Historically, PG is classically linked to inflammatory bowel disease; however, association with underlying malignancy, including acute myelogenous leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, myeloma, and myeloid metaplasia, also has been described.5

Pathogenesis of CLL

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia represents the most prevalent form of leukemia in US adults, with the second highest annual incidence.6 Cutaneous findings are seen in 25% of patients with CLL, varying from leukemia cutis to secondary findings such as vasculitis, purpura, generalized pruritus, exfoliative erythroderma, paraneoplastic pemphigus, infections, and rarely neutrophilic dermatoses.7 According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term pyoderma gangrenosum in CLL, only 4 cases of PG occurring in the setting of CLL exist in the literature, with 1 case demonstrating development after a surgical procedure, making ours the second such case (Table).1-4

Diagnosis

Making the diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG or Sweet syndrome (SS) in the hospital setting is not only difficult but also imperative, considering that the counterdiagnosis more often is an infectious process. The distinction between individual neutrophilic dermatoses is less crucial at the onset because the initial treatment is the same.

Sweet syndrome is classically the most challenging entity within the spectrum to differentiate from PG. However, our case outlines several key distinguishing features:

• The lesion in classic PG is a rapidly expanding ulceration with undermined borders, whereas SS is less commonly associated with ulceration and instead classically presents with multiple edematous papules that progress to juicy plaques.8

• The pathergy phenomenon has been reported in SS, though it is more commonly associated with PG.9

• In reported cases of SS that were related to cutaneous trauma, lesions developed outside the area of trauma and there was documented leukocytosis and neutrophilia.10-14

• Although leukocytosis is part of the minor diagnostic criteria for SS, it is not required for the diagnosis of PG. Considering that our patient had ulcerated lesions, lesions only at the site of trauma, and leukopenia with intermittent neutropenia, the diagnosis was consistent with PG.

The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of PG lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process, which can be challenging in an immunosuppressed patient with an underlying hematologic malignancy.

Conclusion

This case report represents our experience in arriving at the correct diagnosis of PG in a febrile neutrophilic patient with CLL. In the case of PG in a complicated patient, it is critical to initiate appropriate treatment and avoid inappropriate therapies. Aggressive surgical debridement could have resulted in a fatal outcome for our patient, highlighting the need for dermatologists to raise physician awareness of this challenging disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Shalin, MD, PhD; Nikhil Meena, MD; and Aditya Chada, MD (all from Little Rock, Arkansas), for excellent patient care.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

- Solovan C, Smiszek R, Wickenhauser C, et al. Postoperative pyoderma gangrenosum in association with renal cell carcinoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Infect Dis Ther. 2013;2:75-80.

- Sławińska M, Barańska-Rybak W, Sobjanek M, et al. Ibrutinib-induced pyoderma gangrenosum. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:710-711.

- Swale VJ, Saha M, Kapur N, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum outside the context of inflammatory bowel disease treated successfully with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:134-136.

- Wong SM, McComish J, Douglass J, et al. Rare skin manifestations successfully treated with primary B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia treatment. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:552-555.

- Jockenhöfer F, Herberger K, Schaller J, et al. Tricenter analysis of cofactors and comorbidity in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:1023-1030.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30. 7.

- Robak E, Robak T. Skin lesions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:855-865.

- Beasley JM, Sluzevich JC. A recurrent vesiculobullous eruption on the head, trunk, and extremities. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:149-150.

- Awan F, Hamadani M, Devine S. Paraneoplastic Sweet’s syndrome and the pathergy phenomenon. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:613-614.

- de Moya MA, Wong JT, Kroshinsky D, et al. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 28-2012. A 30-year-old woman with shock and abdominal-wall necrosis after cesarean section. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1046-1057.

- Minocha R, Sebaratnam DF, Choi JY. Sweet’s syndrome following surgery: cutaneous trauma as a possible aetiological co-factor in neutrophilic dermatoses. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:

e74-e76. - Phua YS, Al-Ani SA, She RB, et al. Sweet’s syndrome triggered by scalding: a case study and review of the literature. Burns. 2010;36:e49-e52.

- Schwarz RE, Quinn MA, Molina A. Acute postoperative dermatosis at the site of the electrocautery pad: sweet diagnosis of a burning issue. Surg Today. 2000;30:207-209.

- Tan AW, Tan HH, Lim PL. Bullous Sweet’s syndrome following influenza vaccination in a HIV-infected patient. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1254-1255.

Practice Points

- The primary value of early recognition and diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) lies in the physician’s ability to distinguish PG from an infectious process.

- Surgical debridement would further exacerbate PG, making proper diagnosis of a neutrophilic dermatosis of paramount importance to avoid treatments that could have grave consequences in the misdiagnosed patient.

- Cutaneous findings are seen in one-quarter of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum is commonly associated with inflammatory bowel disease but also can be seen in many hematologic malignancies. Physicians should be aware of this association to ensure these patients are diagnosed properly.

Don’t Forget These 5 Things When Treating Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a common and debilitating inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit that presents with recurrent scarring inflammatory nodules and sinus tracts in the intertriginous folds of the body. It is a complex condition that requires multimodal management to address the medical, surgical, and psychosocial needs of affected patients. However, it can be difficult to coordinate all that goes into HS management beyond the standard therapeutic ladder of topical and oral antimicrobials, intralesional corticosteroids, biologics, and surgery. In this article, I will outline 5 important aspects of HS treatment that often are overlooked.

Talk About Pathophysiology

Patients with HS often have limited understanding of their condition. One common misperception is that HS is an infectious disease and that disease activity is associated with poor hygiene.1 Dispelling this myth may help patients avoid unnecessary hygiene practices, decrease perceived stigma, and enhance your therapeutic alliance.

The current model of HS pathophysiology implicates an aberrant inflammatory response to the cutaneous bacterial microbiome, which leads to follicular occlusion and then rupture of debris and bacteria into the surrounding dermis. Immune cells and inflammatory mediators such as nuclear factor κB and tumor necrosis factor α respond to the disruption. Chronic lesions develop due to tissue repair with scarring and re-epithelialization.2,3 Although most patients probably are not interested in the esoteric details, I typically make a point of explaining to patients that HS is a chronic inflammatory disease and provide reassurance that it is not a sign of poor hygiene.

Counsel on Smoking Cessation

Most HS patients use tobacco. As many as 75% of HS patients are active smokers and another 10% to 15% are former smokers. Although there is mixed evidence that disease activity correlates with smoking status, the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation in the United States and Canada concluded in the 2019 North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa that due to the overall health risks of smoking, we should recommend cessation to our patients.4

Laser Hair Removal Works

Don’t forget about laser hair removal! Evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the use of the Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of HS. Treat the entire affected anatomic area and use stacked double pulses on active nodules (typical settings: 10-mm spot size; 10-millisecond pulse duration and 35–50 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I–III; 20-millisecond pulse duration and 25–40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).4 Especially if it is covered by your patient’s insurance, Nd:YAG is a great adjunctive treatment to consider. The guidelines also recommend long-pulsed alexandrite and diode lasers as well as intense pulsed light, all of which result in follicular destruction, though these treatments have less supporting evidence.4

Have a Plan for Flares

Intralesional injection of triamcinolone is a mainstay of HS treatment and provides patients with rapid relief of symptoms during a flare.5 One case series found that there was a notable decrease in pain, size, and drainage after just 1 day of treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL (0.2–2.0 mL).6

Intralesional steroid injection is a great tool for quieting an active disease flare while simultaneously instating ongoing treatment for preventive management. However, even when disease control is optimized, patients may still experience intermittent flares of disease. For some patients, it may be appropriate to have a plan in place for a return to clinic during the beginning of a flare to obtain intralesional steroids. The ability to come in on short notice may help avoid visits to the emergency department and urgent care where your patients may receive treatments such as short courses of antibiotics or incision and drainage that may deviate from your overall treatment plan.

Consider Childbearing Status

Don’t forget to consider childbearing plans and childbearing potential when treating female patients with HS. Pregnancy is a frequent consideration in HS patients, as HS affects 3 to 4 times more women than men and typically presents after puberty (second or third decades of life). Many of the medications in the HS armamentarium are contraindicated in pregnancy including tetracyclines, retinoids, and hormonal agents. Surgery should be avoided in pregnant patients whenever possible, particularly in the first trimester. Relatively safe options include topical antibiotics such as clindamycin and metronidazole, as well as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, which are classified as category B in pregnancy.5

Before making treatment decisions in pregnant and breastfeeding patients, consult the US Food and Drug Administration recommendations. Perng et al7 reviewed current management strategies for HS in pregnant and breastfeeding women, and their review article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology is an excellent resource.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive management of HS may include a combination of medication and procedures, lifestyle modification, management of comorbidities, and social support. Formulating a good treatment plan may be a challenge but can drastically improve your patient’s quality of life.

- What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation website. https://www.hs-foundation.org/what-is-hs. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Topical, systemic and biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenic insights by examining therapeutic mechanisms. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319830646. doi:10.1177/2040622319830646

- Lacarrubba F, Musumeci ML, Nasca MR, et al. Double-ended pseudocomedones in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological correlation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:763-764.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Riis PT, Boer J, Prens EP, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1151-1155.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a common and debilitating inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit that presents with recurrent scarring inflammatory nodules and sinus tracts in the intertriginous folds of the body. It is a complex condition that requires multimodal management to address the medical, surgical, and psychosocial needs of affected patients. However, it can be difficult to coordinate all that goes into HS management beyond the standard therapeutic ladder of topical and oral antimicrobials, intralesional corticosteroids, biologics, and surgery. In this article, I will outline 5 important aspects of HS treatment that often are overlooked.

Talk About Pathophysiology

Patients with HS often have limited understanding of their condition. One common misperception is that HS is an infectious disease and that disease activity is associated with poor hygiene.1 Dispelling this myth may help patients avoid unnecessary hygiene practices, decrease perceived stigma, and enhance your therapeutic alliance.

The current model of HS pathophysiology implicates an aberrant inflammatory response to the cutaneous bacterial microbiome, which leads to follicular occlusion and then rupture of debris and bacteria into the surrounding dermis. Immune cells and inflammatory mediators such as nuclear factor κB and tumor necrosis factor α respond to the disruption. Chronic lesions develop due to tissue repair with scarring and re-epithelialization.2,3 Although most patients probably are not interested in the esoteric details, I typically make a point of explaining to patients that HS is a chronic inflammatory disease and provide reassurance that it is not a sign of poor hygiene.

Counsel on Smoking Cessation

Most HS patients use tobacco. As many as 75% of HS patients are active smokers and another 10% to 15% are former smokers. Although there is mixed evidence that disease activity correlates with smoking status, the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation in the United States and Canada concluded in the 2019 North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa that due to the overall health risks of smoking, we should recommend cessation to our patients.4

Laser Hair Removal Works

Don’t forget about laser hair removal! Evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the use of the Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of HS. Treat the entire affected anatomic area and use stacked double pulses on active nodules (typical settings: 10-mm spot size; 10-millisecond pulse duration and 35–50 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I–III; 20-millisecond pulse duration and 25–40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).4 Especially if it is covered by your patient’s insurance, Nd:YAG is a great adjunctive treatment to consider. The guidelines also recommend long-pulsed alexandrite and diode lasers as well as intense pulsed light, all of which result in follicular destruction, though these treatments have less supporting evidence.4

Have a Plan for Flares

Intralesional injection of triamcinolone is a mainstay of HS treatment and provides patients with rapid relief of symptoms during a flare.5 One case series found that there was a notable decrease in pain, size, and drainage after just 1 day of treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL (0.2–2.0 mL).6

Intralesional steroid injection is a great tool for quieting an active disease flare while simultaneously instating ongoing treatment for preventive management. However, even when disease control is optimized, patients may still experience intermittent flares of disease. For some patients, it may be appropriate to have a plan in place for a return to clinic during the beginning of a flare to obtain intralesional steroids. The ability to come in on short notice may help avoid visits to the emergency department and urgent care where your patients may receive treatments such as short courses of antibiotics or incision and drainage that may deviate from your overall treatment plan.

Consider Childbearing Status

Don’t forget to consider childbearing plans and childbearing potential when treating female patients with HS. Pregnancy is a frequent consideration in HS patients, as HS affects 3 to 4 times more women than men and typically presents after puberty (second or third decades of life). Many of the medications in the HS armamentarium are contraindicated in pregnancy including tetracyclines, retinoids, and hormonal agents. Surgery should be avoided in pregnant patients whenever possible, particularly in the first trimester. Relatively safe options include topical antibiotics such as clindamycin and metronidazole, as well as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, which are classified as category B in pregnancy.5

Before making treatment decisions in pregnant and breastfeeding patients, consult the US Food and Drug Administration recommendations. Perng et al7 reviewed current management strategies for HS in pregnant and breastfeeding women, and their review article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology is an excellent resource.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive management of HS may include a combination of medication and procedures, lifestyle modification, management of comorbidities, and social support. Formulating a good treatment plan may be a challenge but can drastically improve your patient’s quality of life.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a common and debilitating inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous unit that presents with recurrent scarring inflammatory nodules and sinus tracts in the intertriginous folds of the body. It is a complex condition that requires multimodal management to address the medical, surgical, and psychosocial needs of affected patients. However, it can be difficult to coordinate all that goes into HS management beyond the standard therapeutic ladder of topical and oral antimicrobials, intralesional corticosteroids, biologics, and surgery. In this article, I will outline 5 important aspects of HS treatment that often are overlooked.

Talk About Pathophysiology

Patients with HS often have limited understanding of their condition. One common misperception is that HS is an infectious disease and that disease activity is associated with poor hygiene.1 Dispelling this myth may help patients avoid unnecessary hygiene practices, decrease perceived stigma, and enhance your therapeutic alliance.

The current model of HS pathophysiology implicates an aberrant inflammatory response to the cutaneous bacterial microbiome, which leads to follicular occlusion and then rupture of debris and bacteria into the surrounding dermis. Immune cells and inflammatory mediators such as nuclear factor κB and tumor necrosis factor α respond to the disruption. Chronic lesions develop due to tissue repair with scarring and re-epithelialization.2,3 Although most patients probably are not interested in the esoteric details, I typically make a point of explaining to patients that HS is a chronic inflammatory disease and provide reassurance that it is not a sign of poor hygiene.

Counsel on Smoking Cessation

Most HS patients use tobacco. As many as 75% of HS patients are active smokers and another 10% to 15% are former smokers. Although there is mixed evidence that disease activity correlates with smoking status, the Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation in the United States and Canada concluded in the 2019 North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa that due to the overall health risks of smoking, we should recommend cessation to our patients.4

Laser Hair Removal Works

Don’t forget about laser hair removal! Evidence from randomized controlled trials supports the use of the Nd:YAG laser in the treatment of HS. Treat the entire affected anatomic area and use stacked double pulses on active nodules (typical settings: 10-mm spot size; 10-millisecond pulse duration and 35–50 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types I–III; 20-millisecond pulse duration and 25–40 J/cm2 in Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI).4 Especially if it is covered by your patient’s insurance, Nd:YAG is a great adjunctive treatment to consider. The guidelines also recommend long-pulsed alexandrite and diode lasers as well as intense pulsed light, all of which result in follicular destruction, though these treatments have less supporting evidence.4

Have a Plan for Flares

Intralesional injection of triamcinolone is a mainstay of HS treatment and provides patients with rapid relief of symptoms during a flare.5 One case series found that there was a notable decrease in pain, size, and drainage after just 1 day of treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL (0.2–2.0 mL).6

Intralesional steroid injection is a great tool for quieting an active disease flare while simultaneously instating ongoing treatment for preventive management. However, even when disease control is optimized, patients may still experience intermittent flares of disease. For some patients, it may be appropriate to have a plan in place for a return to clinic during the beginning of a flare to obtain intralesional steroids. The ability to come in on short notice may help avoid visits to the emergency department and urgent care where your patients may receive treatments such as short courses of antibiotics or incision and drainage that may deviate from your overall treatment plan.

Consider Childbearing Status

Don’t forget to consider childbearing plans and childbearing potential when treating female patients with HS. Pregnancy is a frequent consideration in HS patients, as HS affects 3 to 4 times more women than men and typically presents after puberty (second or third decades of life). Many of the medications in the HS armamentarium are contraindicated in pregnancy including tetracyclines, retinoids, and hormonal agents. Surgery should be avoided in pregnant patients whenever possible, particularly in the first trimester. Relatively safe options include topical antibiotics such as clindamycin and metronidazole, as well as tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, which are classified as category B in pregnancy.5

Before making treatment decisions in pregnant and breastfeeding patients, consult the US Food and Drug Administration recommendations. Perng et al7 reviewed current management strategies for HS in pregnant and breastfeeding women, and their review article in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology is an excellent resource.

Final Thoughts

Comprehensive management of HS may include a combination of medication and procedures, lifestyle modification, management of comorbidities, and social support. Formulating a good treatment plan may be a challenge but can drastically improve your patient’s quality of life.

- What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation website. https://www.hs-foundation.org/what-is-hs. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Topical, systemic and biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenic insights by examining therapeutic mechanisms. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319830646. doi:10.1177/2040622319830646

- Lacarrubba F, Musumeci ML, Nasca MR, et al. Double-ended pseudocomedones in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological correlation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:763-764.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Riis PT, Boer J, Prens EP, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1151-1155.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989.

- What is hidradenitis suppurativa? Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundation website. https://www.hs-foundation.org/what-is-hs. Accessed October 9, 2019.

- Frew JW, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Topical, systemic and biologic therapies in hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenic insights by examining therapeutic mechanisms. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:2040622319830646. doi:10.1177/2040622319830646

- Lacarrubba F, Musumeci ML, Nasca MR, et al. Double-ended pseudocomedones in hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical, dermoscopic, and histopathological correlation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:763-764.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part I: diagnosis, evaluation, and the use of complementary and procedural management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:76-90.

- Alikhan A, Sayed C, Alavi A, et al. North American Clinical Management Guidelines for Hidradenitis Suppurativa: a publication from the United States and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. part II: topical, intralesional, and systemic medical management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:91-101.

- Riis PT, Boer J, Prens EP, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone for flares of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1151-1155.

- Perng P, Zampella JG, Okoye GA. Management of hidradenitis suppurativa in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:979-989.

Resident Pearls

- Medical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) can be relatively straightforward, but optimal comprehensive management is multifaceted.

- Educate patients about pathophysiology, counsel on smoking cessation, remember laser hair removal, consider an ongoing plan for addressing flares, and think about childbearing status when treating HS patients.

Kaposi Sarcoma in a Patient With Postpolio Syndrome

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a low-grade vascular tumor that is rare among the general US population, with an incidence rate of less than 1 per 100,000.1 The tumor is more common among certain groups of individuals due to geographic differences in the prevalence of KS-associated herpesvirus (also referred to as human herpesvirus 8) as well as host immune factors.2 Kaposi sarcoma often is defined by the patient's predisposing characteristics yielding the following distinct epidemiologic subtypes: (1) classic KS is a rare disease affecting older men of Mediterranean descent; (2) African KS is an endemic cancer with male predominance in sub-Saharan Africa; (3) AIDS-associated KS is an often aggressive AIDS-defining illness; and (4) iatrogenic KS occurs in patients on immunosuppressive therapy.3 When evaluating a patient without any of these risk factors, the clinical suspicion for KS may be low. We report a patient with postpolio syndrome (PPS) who presented with KS of the right leg, ankle, and foot.

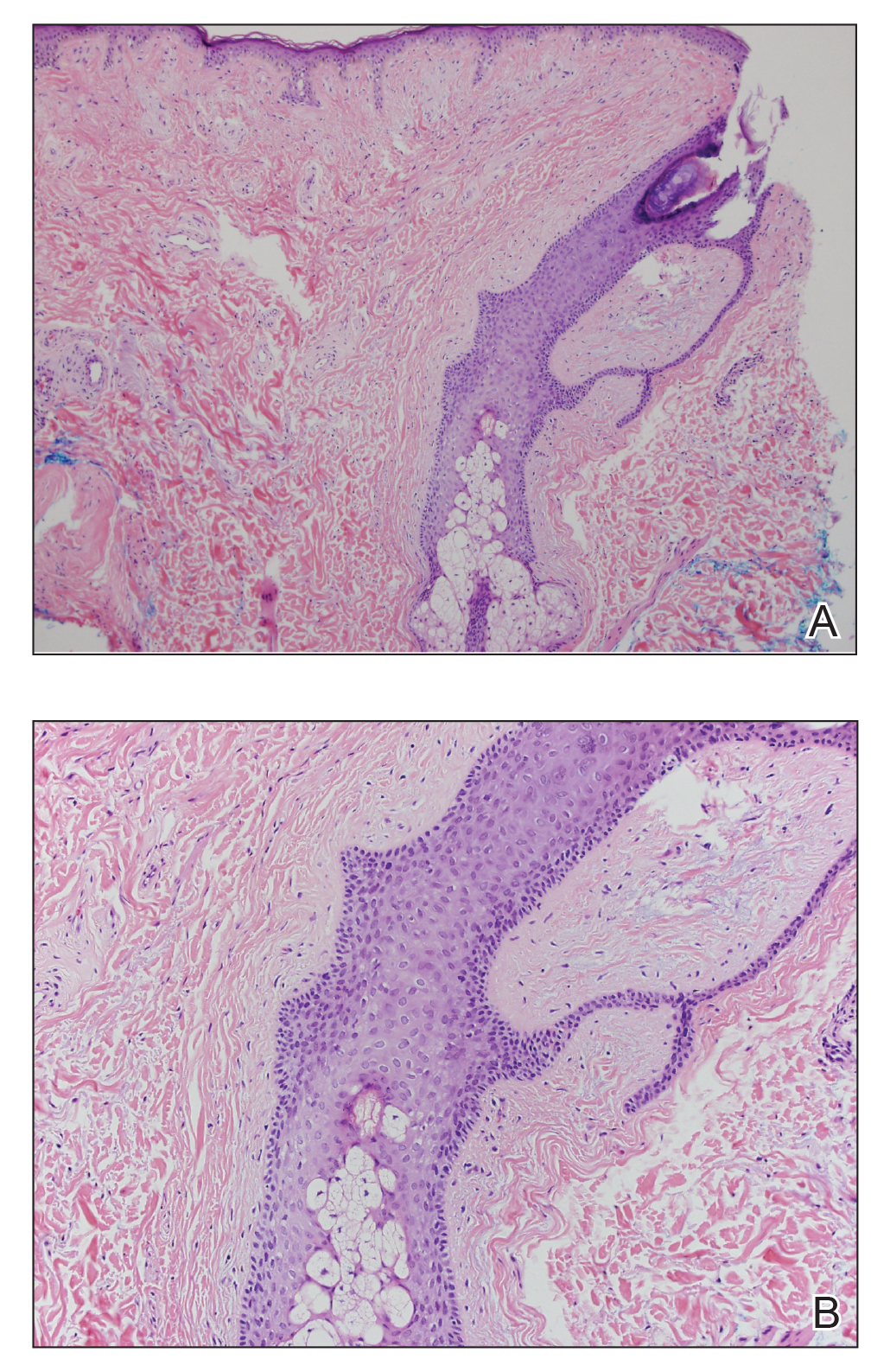

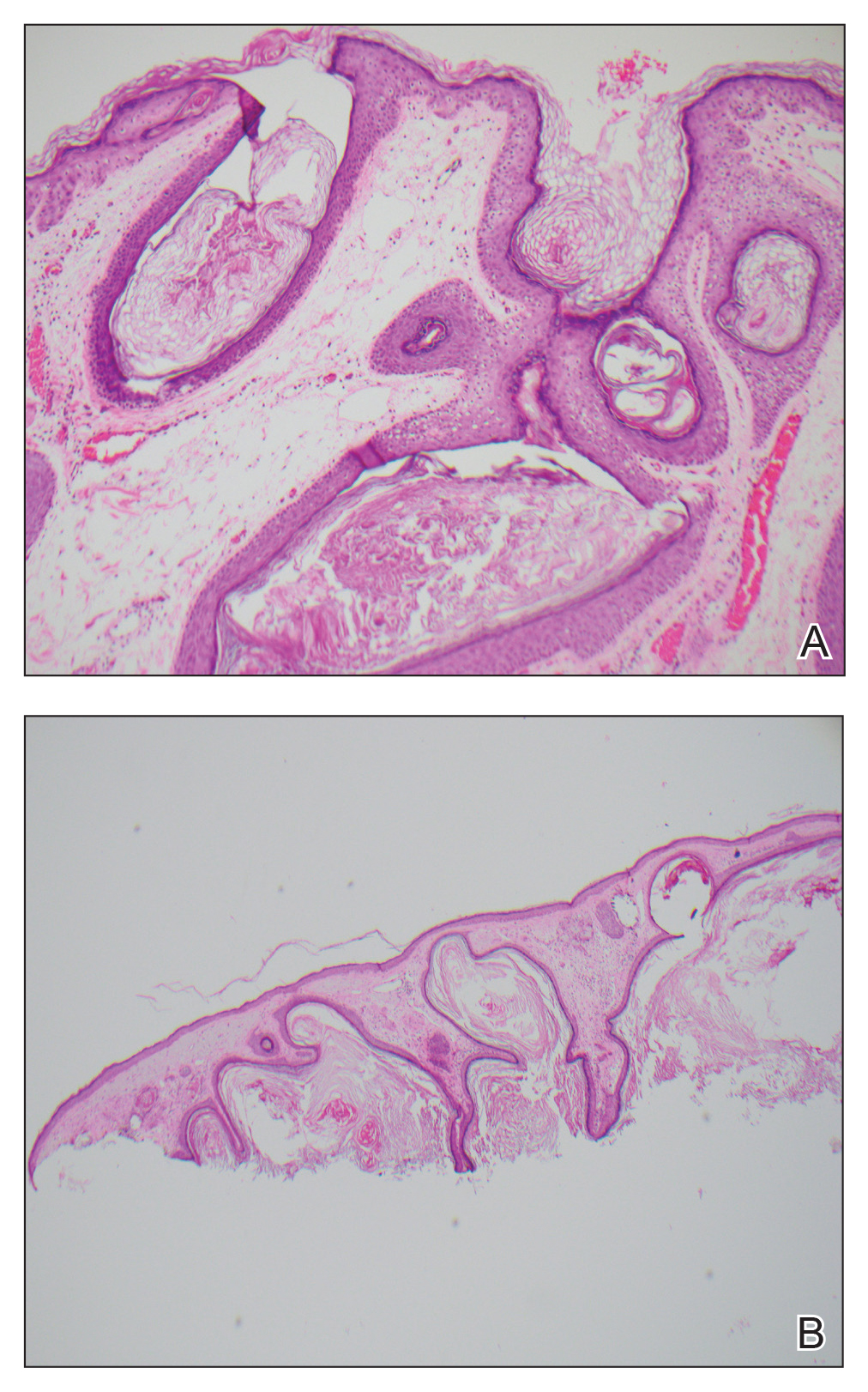

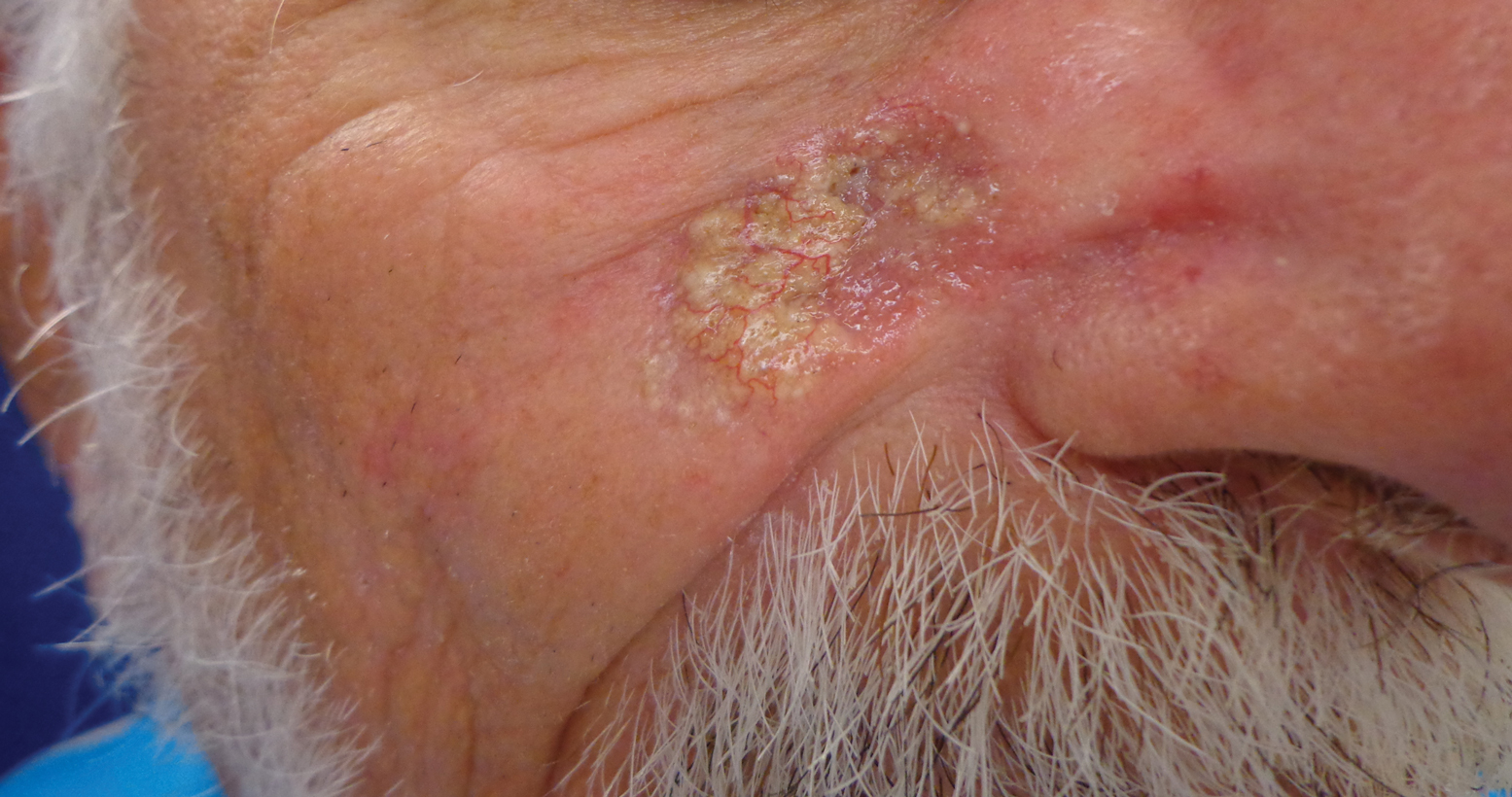

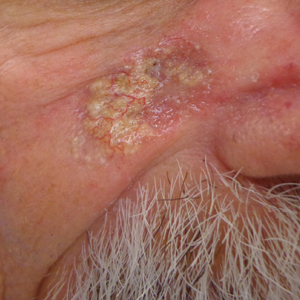

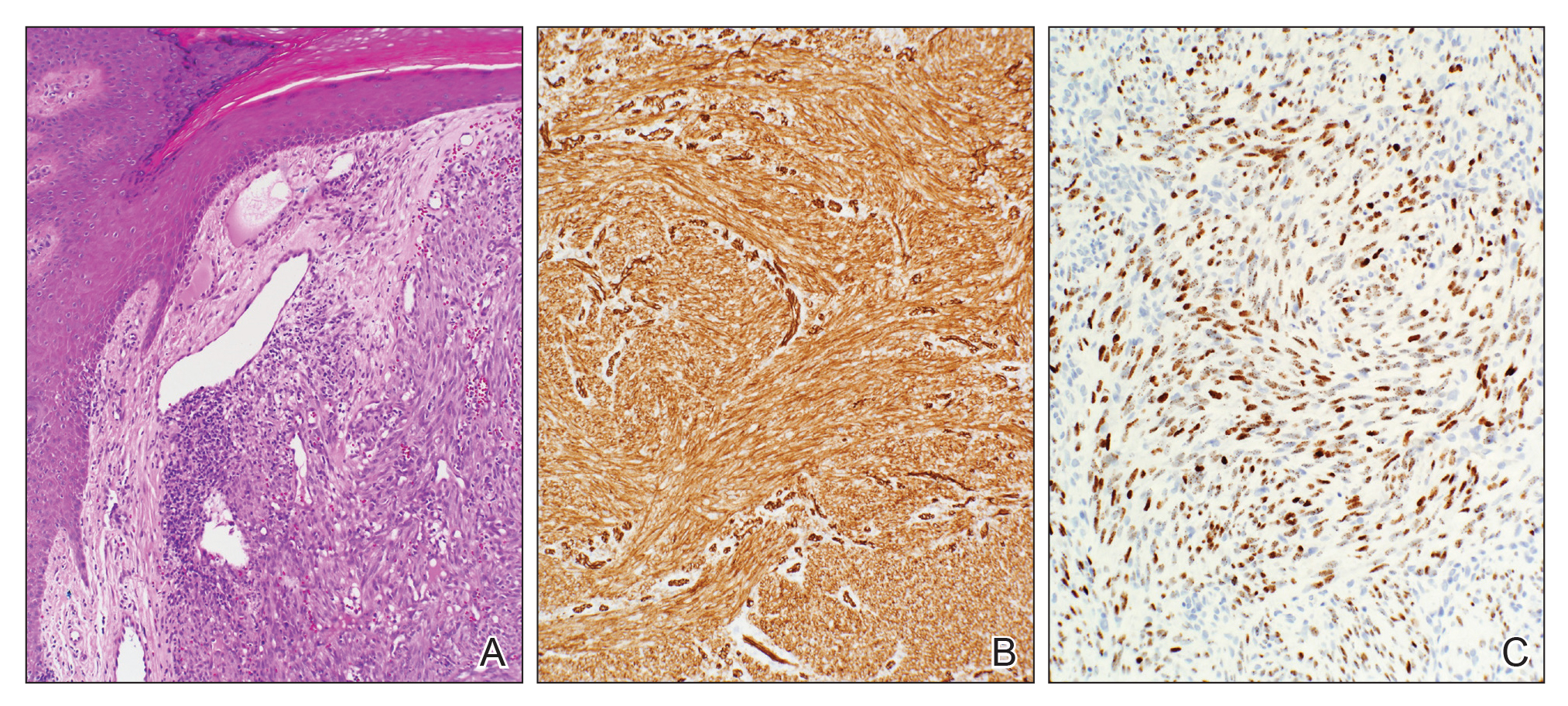

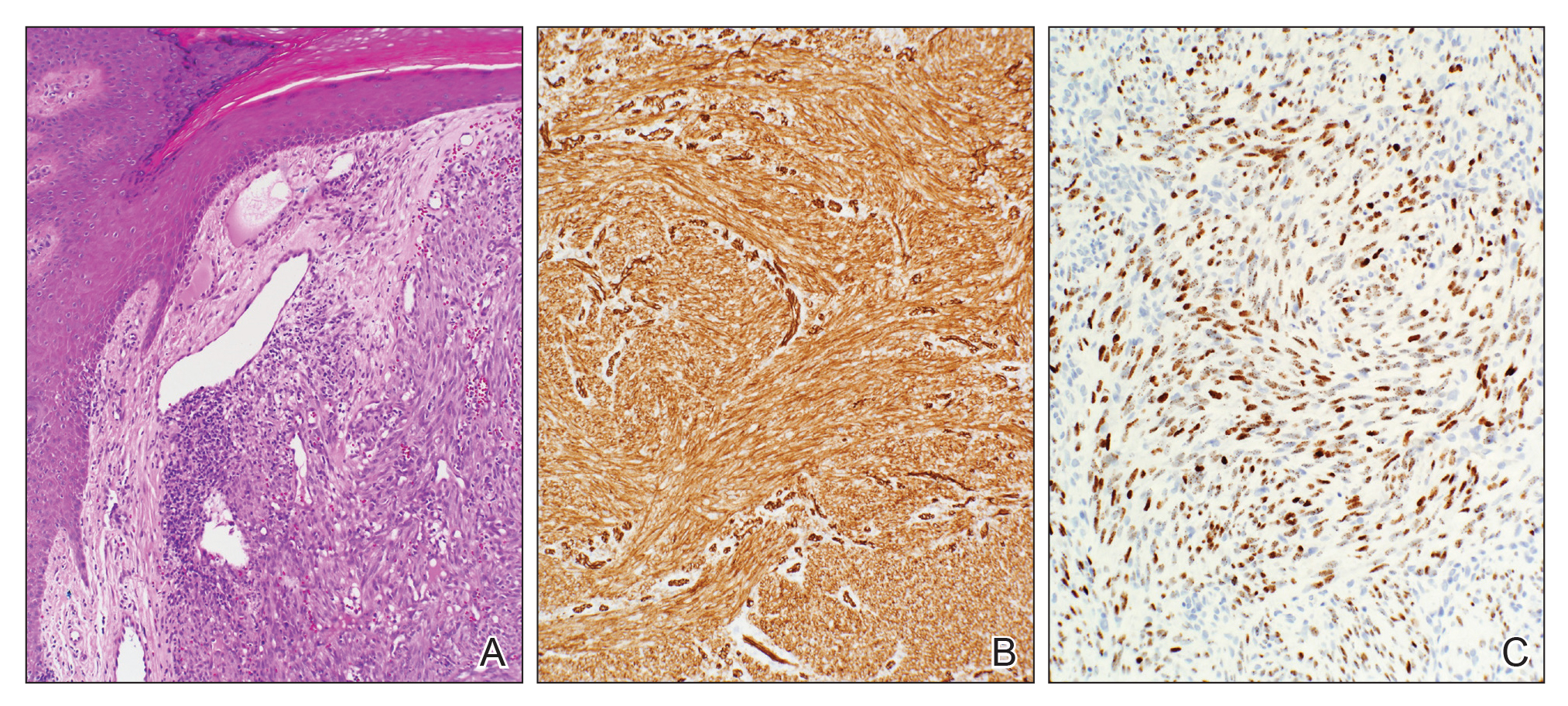

A 77-year-old man with a distant history of paralytic poliomyelitis presented for an annual skin examination with concern for a new lesion on the right ankle. The patient had a history of PPS primarily affecting the right leg. Physical examination revealed residual weakness in an atrophic right lower extremity with a mottled appearance and mild pitting edema to the knee. Two red, dome-shaped, vascular papules were appreciated on the medial aspect of the right ankle (Figure 1), and a shave biopsy of the larger papule was performed. Microscopic examination of the biopsy specimen was consistent with KS (Figure 2). This patient had no history of human immunodeficiency virus or immunosuppressive therapy and was not of Mediterranean descent.