User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Challenges of Treating Primary Psychiatric Disease in Dermatology

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

Resident Pearl

- Patients often present to dermatology with primary psychologic disorders such as delusional infestation or trichotillomania. Treatment of such conditions with antidepressants and antipsychotics can be highly effective and is within our scope of practice. Increased emphasis on psychopharmacotherapy in dermatology training would increase access to appropriate care for this patient population.

Bimatoprost-Induced Iris Hyperpigmentation: Beauty in the Darkened Eye of the Beholder

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

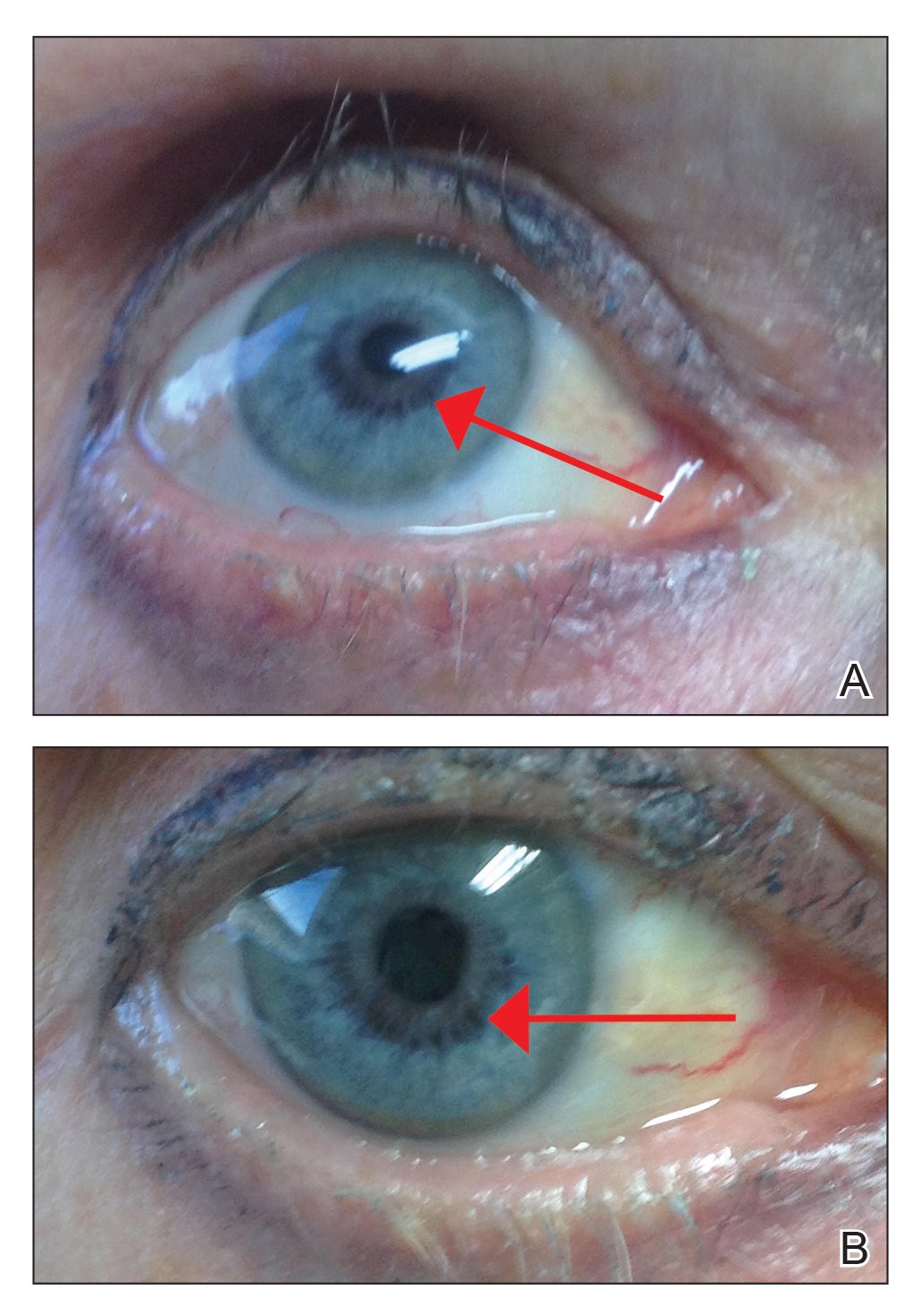

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

To the Editor:

Long, dark, and thick eyelashes have been a focal point of society’s perception of beauty for thousands of years,1 and the use of makeup products such as mascaras, eyeliners, and eye shadows has further increased the perception of attractiveness of the eyes.2 Many eyelash enhancement methods have been developed or in some instances have been serendipitously discovered. Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% originally was developed as an eye drop that was approved by the US Food and Drug Association (FDA) in 2001 for the reduction of elevated intraocular pressure in patients with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension. An unexpected side effect of this product was eyelash hypertrichosis.3,4 As a result, the FDA approved

Because all follicular development occurs during embryogenesis, the number of eyelash follicles does not increase over time.6 Bitmatoprost eyelash solution works by prolonging the anagen (growth) phase of the eyelashes and stimulating the transition from the telogen (dormant) phase to the anagen phase. It also has been shown to increase the hair bulb diameter of follicles undergoing the anagen phase, resulting in thicker eyelashes.7 Although many patients have enjoyed this unexpected indication, prostaglandin (PG) analogues such as bimatoprost and latanoprost have a well-documented history of ocular side effects when applied directly to the eye. The most common adverse reactions include eye pruritus, conjunctival hyperemia, and eyelid pigmentation.3 The product safety information indicates that eyelid pigmentation typically is reversible.3,5 Iris pigmentation is perhaps the least desirable side effect of PG analogues and was first noted in latanoprost studies on primates.8 The underlying mechanism appears to be due to an increase in melanogenesis that results in an increase in melanin granules without concomitant proliferation of melanocytes, cellular atypia, or evidence of inflammatory reaction. Unfortunately, this pigmentation typically is permanent.3,5,9

Studies have shown that

An otherwise healthy 63-year-old woman presented to our clinic for an annual skin examination. She noted that she had worsening dark pigmentation of the bilateral irises. The patient did not have any personal or family history of melanoma or ocular nevi, and there were no associated symptoms of eye tearing, pruritus, burning, or discharge. No prior surgical procedures had been performed on or around the eyes, and the patient never used contact lenses. She had been intermittently using bimatoprost eyelash solution prescribed by an outside physician for approximately 3 years to enhance her eyelashes. Although she never applied the product directly into her eyes, she noted that she often was unmethodical in application of the product and that runoff from the product may have occasionally leaked into the eyes. Physical examination revealed bilateral blue irises with ink spot–like, grayish black patches encircling the bilateral pupils (Figure).

The patient was advised to stop using the product, but no improvement of the iris hyperpigmentation was appreciated at 6-month follow-up. The patient declined referral to ophthalmology for evaluation to confirm a diagnosis and discuss treatment because the hyperpigmentation did not bother her.

There have been several studies of iris hyperpigmentation with use of PG analogues in the treatment of glaucoma. In a phase 3 clinical trial of the safety and efficacy of latanoprost for treatment of ocular hypertension, it was noted that 24 (12%) of 198 patients experienced iris hyperpigmentation and that patients with heterogeneous pigmentation (ie, hazel irises and mixed coloring) were at an increased risk.11 Other studies also have shown an increased risk of iris hyperpigmentation due to heterogeneous phenotype12 as well as older age.13

Reports of bimatoprost eye drops used for treatment of glaucoma have shown a high incidence of iris hyperpigmentation with long-term use. A prospective study conducted in 2012 investigated the adverse events of bimatoprost eye drops in 52 Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clinical photographs of the irises, eyelids, and eyelashes were taken at baseline and after 6 months of treatment. It was noted that 50% (26/52) of participants experienced iris hyperpigmentation upon completion of treatment.10

In our patient, bimatoprost eyelash solution was applied to the top eyelid margins using an applicator; our patient did not use the eye drop formulation, which is directed for use in ocular hypertension or glaucoma. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bimatoprost and iris hyperpigmentation yielded no published peer-reviewed studies or case reports of iris hyperpigmentation caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution for treatment of eyelid hypotrichosis, which makes this case report novel. With that said, the package insert states iris hyperpigmentation as a side effect in the prescribing information for both a bimatoprost eye drop formulation used to treat ocular hypertension3 as well as a formulation for topical application on the eyelids/eyelashes.5 A 2014 retrospective review of long-term safety with bimatoprost eyelash solution for eyelash hypotrichosis reported 4 instances (0.7%) of documented adverse events after 12 months of use in 585 patients, including dry eye, eyelid erythema, ocular pruritus, and low ocular pressure. Iris hyperpigmentation was not reported.14

The method of bimatoprost application likely is a determining factor in the number of reported adverse events. Studies with similar treatment periods have demonstrated more adverse events associated with bimatoprost eye drops vs eyelash solution.15,16 When bimatoprost is used in the eye drop formulation for treatment of glaucoma, iris hyperpigmentation has been estimated to occur in 1.5%4 to 50%9 of cases. To our knowledge, there are no documented cases when bimatoprost eyelash solution is applied with a dermal applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.15,17 These results may be explained using an ocular splash test. In one study using lissamine green dye, decreased delivery of bimatoprost eyelash solution with the dermal applicator was noted vs eye drop application. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that approximately 5% (based on weight) of a one-drop dose of bimatoprost eyelash solution applied to the dermal applicator is actually delivered to the patient.18 The rest of the solution remains on the applicator.

It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information (eg, clean the face, remove makeup and contact lenses prior to applying the product). The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye. One drop of bimatoprost eyelash solution should be applied to the applicator supplied by the manufacturer and distributed evenly along the skin of the upper eyelid margin at the base of the eyelashes. It is important to blot any excess solution runoff outside the upper eyelid margin.5 Of note, our patient admitted to not always doing this step, which may have contributed to her susceptibility to this rare side effect.

Prostaglandin analogues have been observed to cause iris hyperpigmentation when applied directly to the eye for use in the treatment of glaucoma.19 Theoretically, the same side-effect profile should apply in their use as a dermal application on the eyelids. For this reason, one manufacturer includes iris hyperpigmentation as an adverse side effect in the prescribing information.5 It is important for physicians who prescribe bimatoprost eyelash solution to inform patients of this rare yet possible side effect and to instruct patients on proper application to minimize hyperpigmentation.

Our literature review did not demonstrate previous cases of iris hyperpigmentation associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution. One study suggested that 2 patients experienced hypopigmentation; however, this was not clinically significant and was not consistent with the proposed iris pigmentation thought to be caused by bimatoprost eyelash solution.20

Potential future applications and off-label uses of bimatoprost include treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis on the lower eyelid margin and eyebrow hypertrichosis, as well as androgenic alopecia, alopecia areata, chemotherapy-induced alopecia, vitiligo, and hypopigmented scarring.21 Currently, investigational studies are looking at bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for chemotherapy-induced eyelash hypotrichosis with positive results.22 In the future, bimatoprost may be used for other off-label and possibly FDA-approved uses.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

- Draelos ZD. Special considerations in eye cosmetics. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19:424-430.

- Mulhern R, Fieldman G, Hussey T, et al. Do cosmetics enhance female Caucasian facial attractiveness? Int J Cosmet Sci. 2003;25:199-205.

- Lumigan [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2012.

- Higginbotham EJ, Schuman JS, Goldberg I, et al; Bimatoprost Study Groups 1 and 2. one-year, randomized study comparing bimatoprost and timolol in glaucoma and ocular hypertension. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1286-1293.

- Latisse [package insert]. Irvine, CA: Allergan, Inc; 2014.

- Hair diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Company; 2003. 7. Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Selen G, Stjernschantz J, Resul B. Prostaglandin-induced iridial pigmentation in primates. Surv Opthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S125-128.

- Stjernschantz JW, Albert DM, Hu D-N, et al. Mechanism and clinical significance of prostaglandin-induced iris pigmentation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(suppl 1):162S-S175S.

- Inoue K, Shiokawa M, Sugahara M, et al. Iris and periocular adverse reactions to bimatoprost in Japanese patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:111-116.

- Alm A, Camras C, Watson P. Phase III latanoprost studies in Scandinavia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S105-S110.

- Wistrand PJ, Stjernschantz J, Olsson K. The incidence and time-course of latanoprost-induced iridial pigmentation as a function of eye color. Surv Ophthalmol. 1997;41(suppl 2):S129-S138.

- Arranz-Marquez E, Teus MA. Effect of age on the development of a latanoprost-induced increase in iris pigmentation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1255-1258.

- Yoelin S, Fagien S, Cox S, et al. A retrospective review and observational study of outcomes and safety of bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% for treating eyelash hypotrichosis. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1118-1124.

- Brandt JD, VanDenburgh AM, Chen K, et al; Bimatoprost Study Group. Comparison of once- or twice-daily bimatoprost with twice-daily timolol in patients with elevated IOP: a 3-month clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1023-1031; discussion 1032.

- Fagien S, Walt JG, Carruthers J, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of bimatoprost for eyelash growth: results from a randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled, parallel-group study. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:789-798.

- Yoelin S, Walt JG, Earl M. Safety, effectiveness, and subjective experience with topical bimatoprost 0.03% for eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:638-649.

- Fagien S. Management of hypotrichosis of the eyelashes: focus on bimatoprost. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2010;2:29-48.

- Rodríguez-Agramonte F, Jiménez JC, Montes JR. Periorbital changes associated with topical prostaglandins analogues in a Hispanic population. P R Health Sci J. 2017;36:218-222.

- Wirta D, Baumann L, Bruce S, et al. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost for eyelash growth in postchemotherapy subjects. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:11-20.

- Choi YM, Diehl J, Levins PC. Promising alternative clinical uses of prostaglandin F2α analogs: beyond the eyelashes [published online January 16, 2015]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:712-716.

- Ahluwalia GS. Safety and efficacy of bimatoprost solution 0.03% topical application in patients with chemotherapy-induced eyelash loss. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S73-S76.

Practice Points

- Bimatoprost ophthalmic solution 0.03% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2008 as an eyelash solution with an eyelid applicator for treatment of eyelash hypotrichosis.

- Iris hyperpigmentation can occur when bimatoprost eye drops are applied to the eyes for treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma, but reports associated with bimatoprost eyelash solution are rare.

- It is important that patients use bimatoprost eyelash solution as instructed in the prescribing information to avoid potential adverse events. The eyelid should not be rinsed after application, which limits the possibility of the bimatoprost solution from contacting or pooling in the eye.

Erythematous Papules and Pustules on the Nose

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

The Diagnosis: Granulosis Rubra Nasi

A history of prominent nasal sweating was later elicited and the patient was subsequently diagnosed with granulosis rubra nasi. She was instructed to continue daily use of topical pimecrolimus with the addition of topical atropine, resulting in complete resolution of the eruption at 6-week follow-up (Figure, A). She was then maintained on topical atropine monotherapy, only noting recurrence with cessation of the atropine (Figure, B).

Other successful treatment regimens of granulosis rubra nasi include injection of botulinum toxin into the nose,1 monotherapy with topical tacrolimus,2 topical indomethacin, steroids, and cryotherapy, among other modalities.1 Topical atropine and pimecrolimus were selected as first-line agents for treating our pediatric patient due to tolerability and their anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic properties.

Granulosis rubra nasi is a form of focal hyperhidrosis that presents as erythematous papules, pustules, and vesicles of the midface, especially the nose.3 It is a fairly rare condition that can mimic many other common clinical entities, including comedonal acne, nevus comedonicus, periorificial dermatitis, and tinea faciei, but is resistant to treatments aimed at these disorders. It was first described as a "peculiar disease of the skin of the nose in children" in a case report by Jadassohn4 in 1901. It is most common in children aged 7 to 12 years and typically resolves at puberty; adults rarely are affected. Although the etiology has not yet been elucidated, autosomal-dominant transmission has been described, and the cutaneous changes are hypothesized to be secondary to hyperhidrosis.5 This postulation is further corroborated by a case report of a pheochromocytoma-associated granulosis rubra nasi that resolved with surgical excision of the pheochromocytoma.6 It is not uncommon for patients to have concomitant palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and acrocyanosis.5 Histopathologic examination is not necessary for diagnosis, but when performed, it discloses a mononuclear cellular infiltrate surrounding eccrine sweat ducts, blood vessels, and lymphatics without other abnormalities of the epidermis or pilosebaceous unit.1-3,7

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

- Grazziotin TC, Buffon RB, Da Silva Manzoni AP, et al. Treatment of granulosis rubra nasi with botulinum toxin. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1298-1299.

- Kumar P, Gosai A, Mondal AK, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi: a rare condition treated successfully with topical tacrolimus. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:E5.

- Sargunam C, Thomas J, Ahmed NA. Granulosis rubra nasi. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2013;4:208-209.

- Jadassohn J. Ueber eine eigenartige erkrankung der nasenhaut bei kindern. Arch Derm Syph. 1901;58:145-158.

- Hellier FF. Granulosis rubra nasi in a mother and daughter. Br Med J. 1937;2:1068.

- Heid E, Samain F, Jelen G, et al. Granulosis rubra nasi and pheochromocytoma. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1996;123:106-108.

- Akhdari N. Granulosis rubra nasi. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:396.

A healthy 9-year-old girl presented with a 2-year history of erythematous papules and pustules on the nose. There was no involvement of the rest of the face or body. At the time of presentation, she had been treated with several topical therapies including steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, antibiotics, and retinoids without improvement. A potassium hydroxide preparation from a pustule was performed and revealed only normal keratinocytes.

Monitoring Acne Patients on Oral Therapy: Survey of the Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Boards answered 5 questions on monitoring acne patients on oral therapy. Here’s what we found.

Do you check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne?

Half of dermatologists surveyed never check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne. For those who do check levels, 8% do it at baseline only, 8% at baseline and every 6 months, 23% at baseline and yearly, and 13% at baseline and for dosing changes.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Although some dermatologists are still checking for potassium levels in patients taking spironolactone for acne, there is a clear trend toward foregoing laboratory monitoring. This change was likely spurred by a retrospective study of healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne that found a hyperkalemia rate of 0.72%, which is practically equivalent to the 0.76% baseline rate of hyperkalemia in this age group. Furthermore, since repeat testing in 6 of 13 patients showed normal values, the original potassium measurements may have been erroneous. Based on this study, routine potassium monitoring is likely unnecessary for healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne (Plovanich et al). In another retrospective study of women aged 18 to 65 years taking spironolactone for acne, women aged 46 to 65 years had a significantly higher rate of hyperkalemia with spironolactone compared with women aged 18 to 45 years (2/12 women [16.7%] vs 1/112 women [<1%]; P=.0245). Based on this study, potassium monitoring may be indicated for women older than 45 years taking spironolactone for acne (Thiede et al).

Next page: Cholesterol levels

Do you monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

Almost two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that they monitor all cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, including low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, but almost one-third monitor triglycerides only. Five percent do not monitor cholesterol levels.

Do you routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 80% of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, with almost half (45%) at baseline and every 2 to 3 months. Eight percent check levels at baseline only, 28% at baseline and monthly, and 3% at baseline and end of therapy. Eighteen percent indicated they do not routinely monitor cholesterol levels.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)