User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Solitary Papule on the Leg

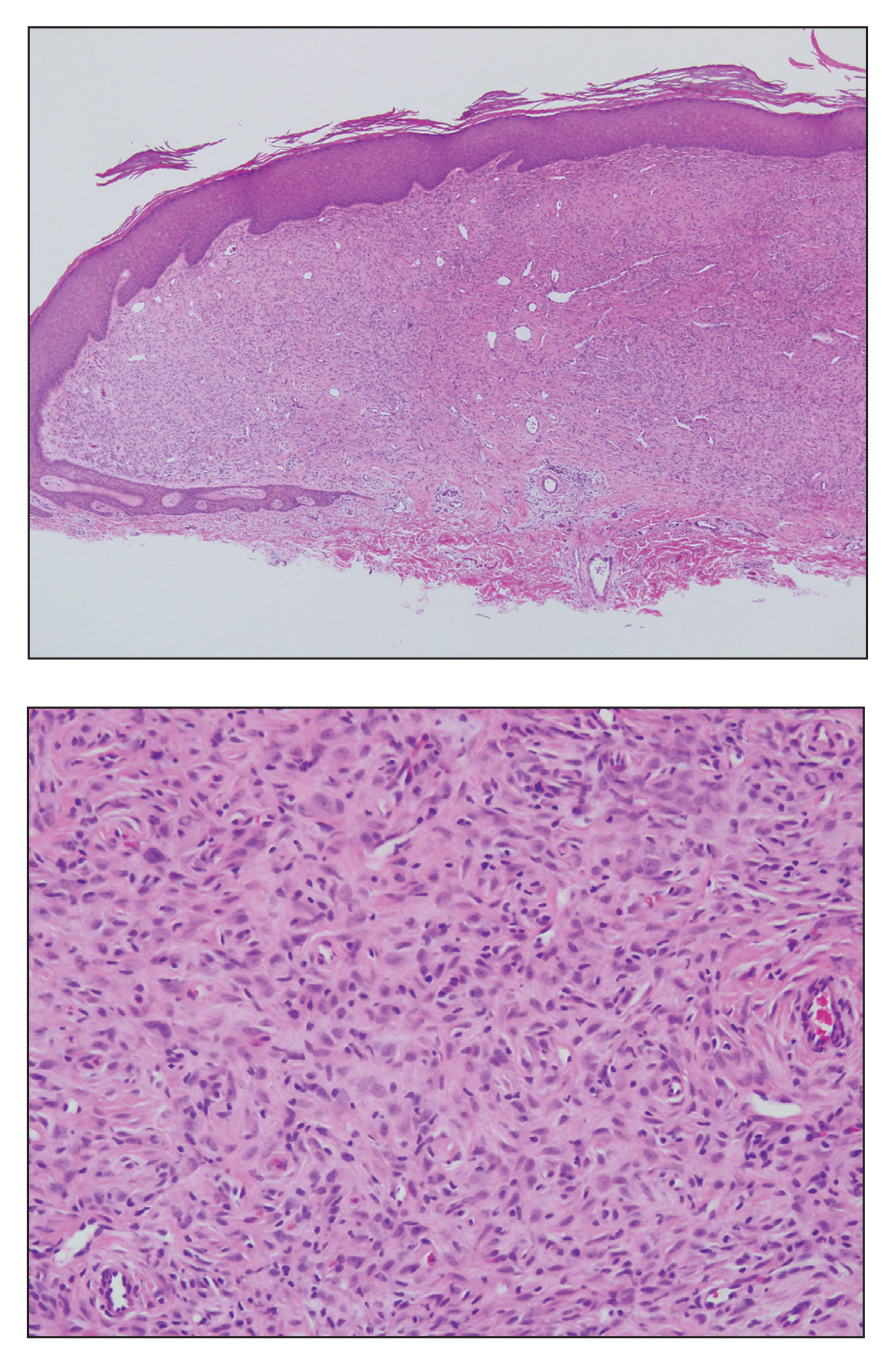

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

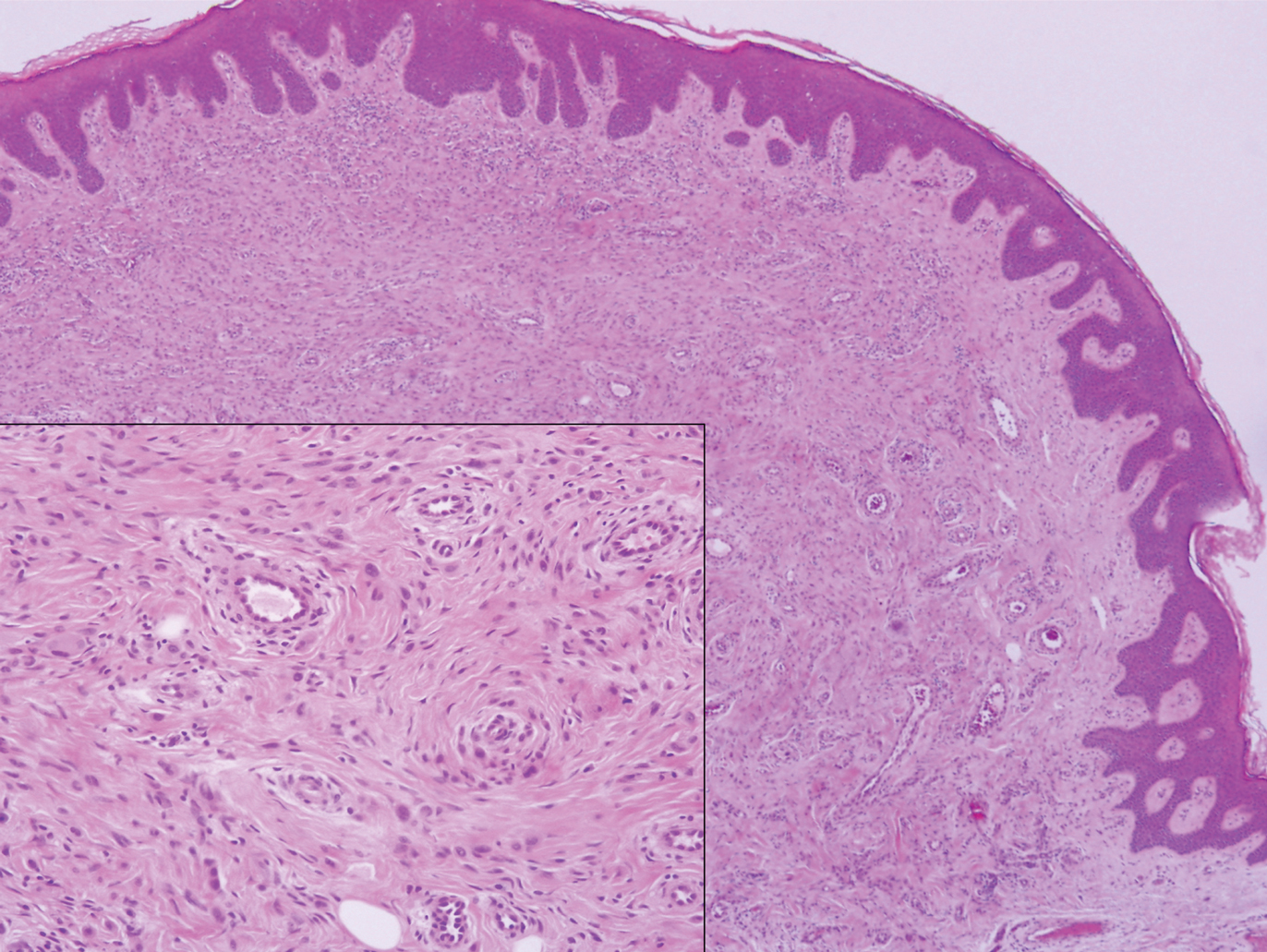

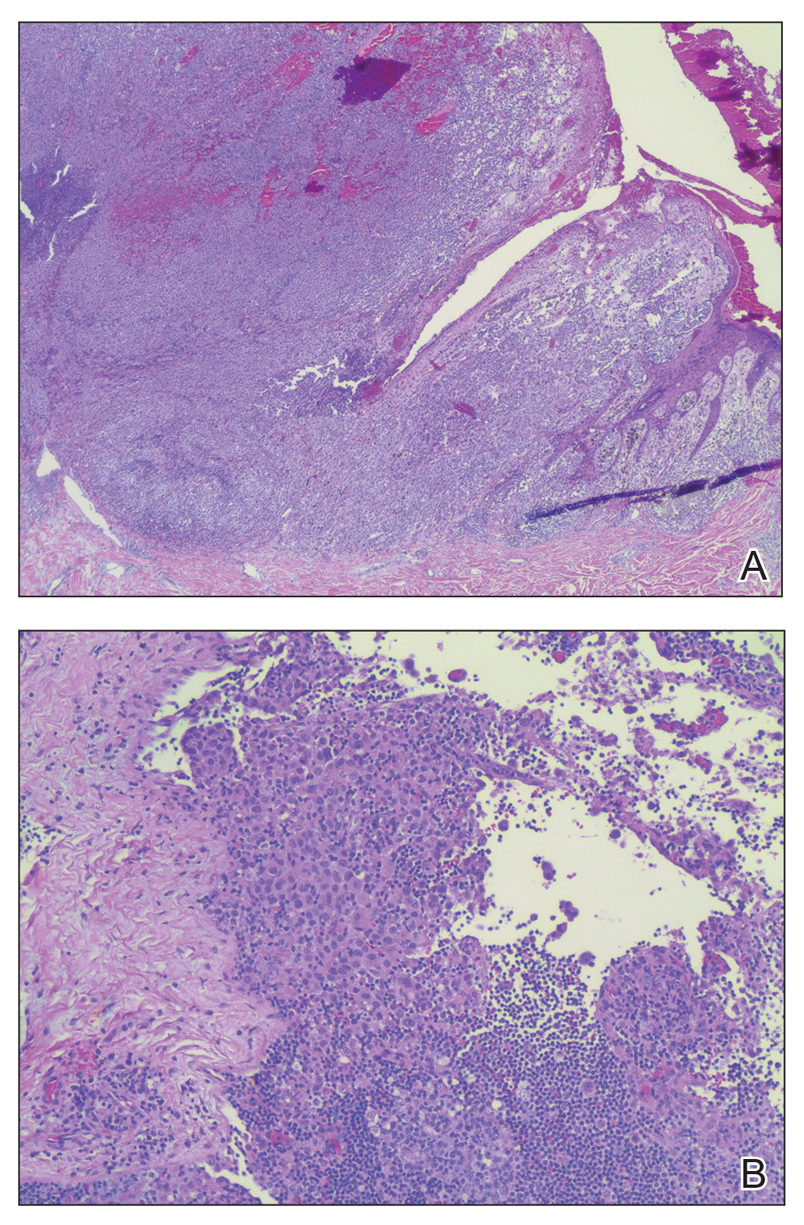

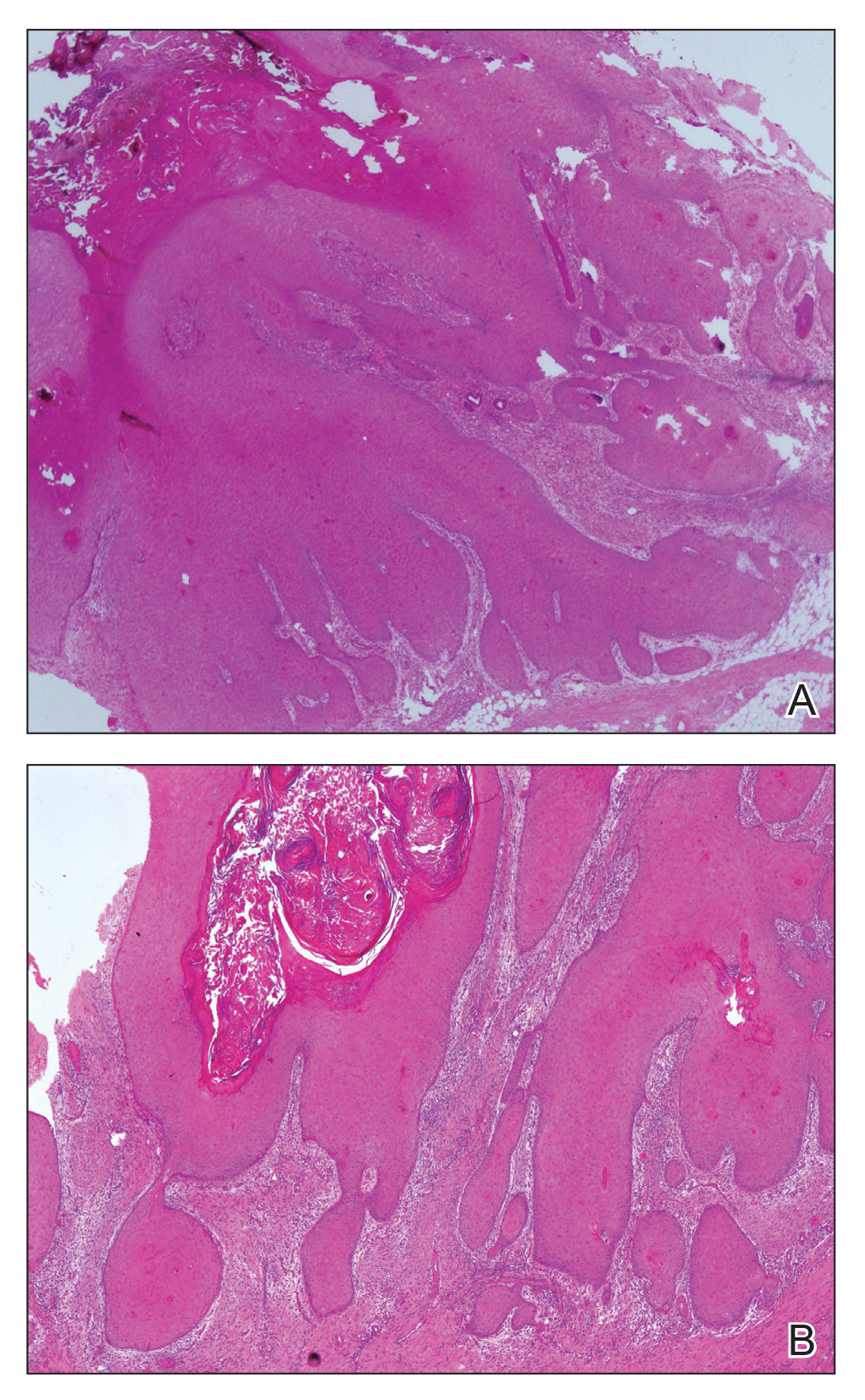

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

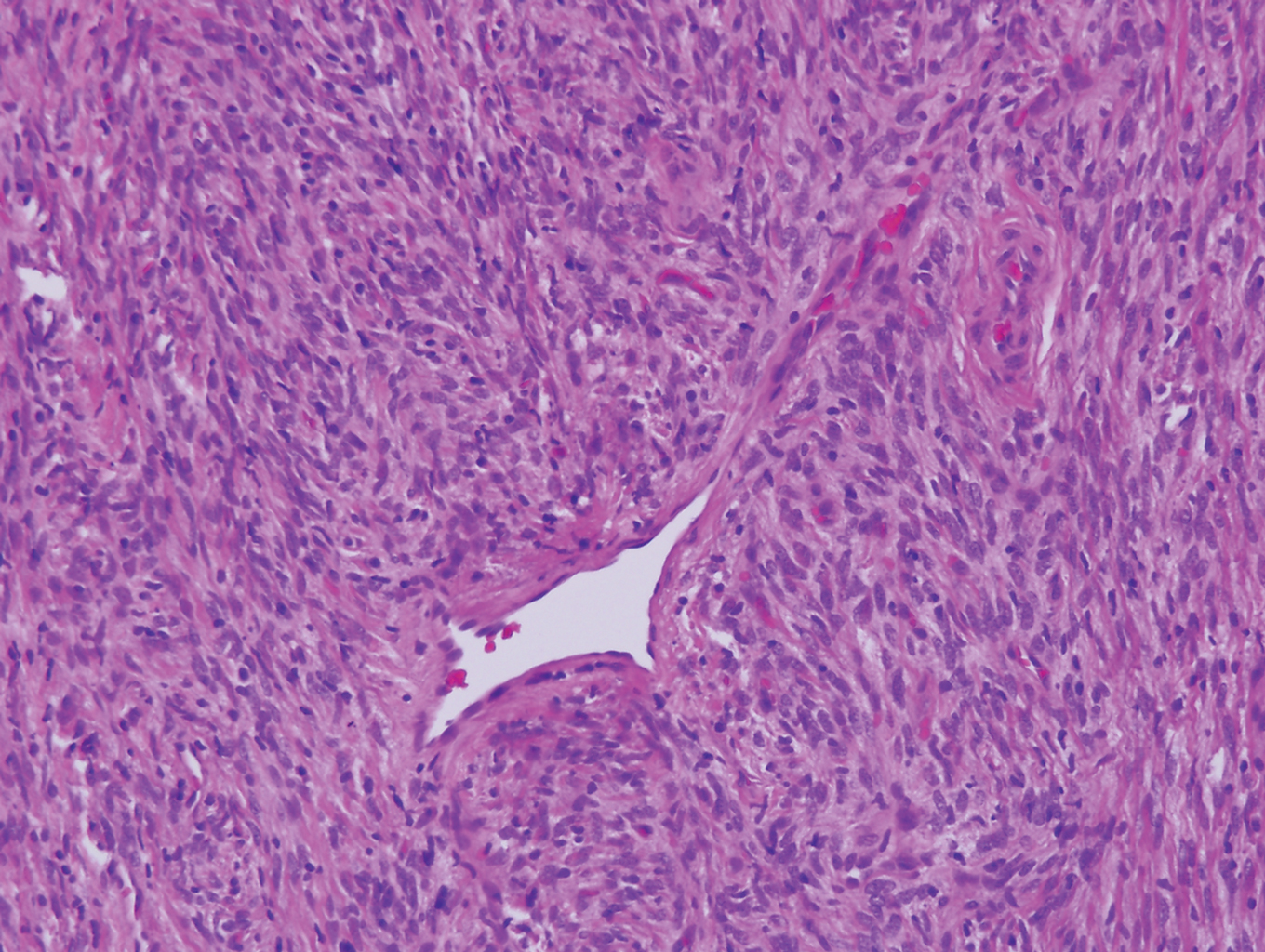

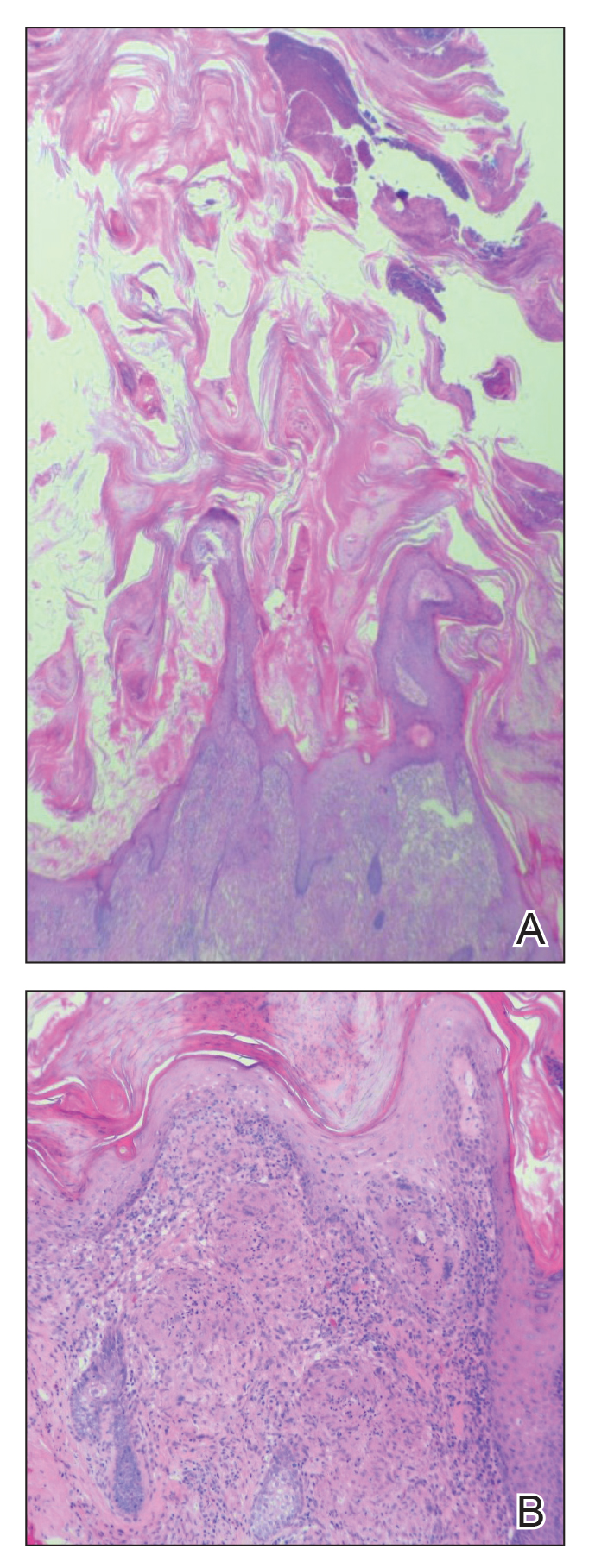

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

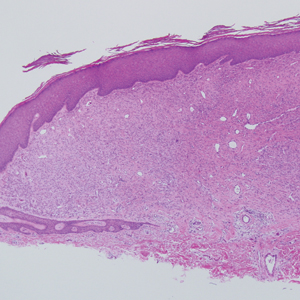

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

The Diagnosis: Epithelioid Histiocytoma

Epithelioid histiocytoma (EH), also known as epithelioid cell histiocytoma or epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma, is a rare benign fibrohistiocytic tumor first described in 1989.1 Epithelioid histiocytoma commonly presents in middle-aged adults with a slight predilection for males.2 The most frequently affected site is the lower extremity. The arms, trunk, head and neck, groin, and tongue also can be involved.3,4 It usually presents as a solitary asymptomatic papule or nodule, though cases with multiple lesions have been reported.5 Anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement and overexpression have been confirmed and suggest that EH is distinct from conventional cutaneous fibrous histiocytoma.5

Histologically, EH appears as an exophytic, symmetric, and well-demarcated dermal nodule with a classic epidermal collarette. Prominent vascularity with perivascular accentuation of the epithelioid tumor cells is common. Older lesions may be hyalinized and sclerotic. Epithelioid cells commonly account for more than 50% of the tumor and are characterized by eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and small eosinophilic nucleoli. A small population of lymphocytes and mast cells are variably present (quiz image, bottom).1-3,7 A predominantly spindle cell variant has been reported.8 Other histopathologic variants include granular cell,9 cellular,10 and EH with perineuriomalike growth.11 Immunohistochemical staining shows anaplastic lymphoma kinase positivity in most cases, and more than half of cases stain positive for factor XIIIa and epithelial membrane antigen. Tumor cells consistently are negative for desmin and cytokeratins.6,10,12 Excision is curative.8

Polypoid Spitz nevus (PSN) is a benign nevus with a conspicuous polypoid or papillary exophytic architecture. The term was coined in 2000 by Fabrizi and Massi.13 Spitz nevus is a benign acquired melanocytic tumor that typically presents in children and adolescents and has a wide histologic spectrum.14 There is some debate on this entity, as some authors do not regard PSN as a distinct histologic variant; thus, it seems underreported in the literature.15 In a review of 349 cases of Spitz nevi, the authors found 7 cases of PSN.16 In another review of 74 cases of intradermal Spitz nevi, 14 cases of PSN were identified.14 This polypoid variant is easily mistaken for a polypoid melanoma because it can show cytologic atypia with large nuclei. Polypoid Spitz nevus usually lacks mitoses, notable pleomorphism, and sheetlike growth, unlike melanoma (Figure 1).13,14

Myopericytoma is an uncommon benign mesenchymal neoplasm that typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging and painless nodule with a predilection for the lower extremities, usually in adult males.17-20 Histologically, it consists of a well-circumscribed nodule with numerous thin-walled vessels and a proliferation of ovoid to spindled myopericytes exhibiting a concentric perivascular growth pattern (Figure 2). Myopericytoma usually is positive for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon but is negative or only focally positive for desmin. The prognosis is good with rare recurrence, despite incomplete excision.17,18

Solitary reticulohistiocytoma is a rare benign form of non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis.21,22 Unlike its multicentric counterpart, solitary reticulohistiocytoma rarely is associated with systemic disease. It presents as a small, dome-shaped, painless papule or nodule that can affect any part of the body.22,23 Solitary reticulohistiocytoma characteristically demonstrates cells with a ground glass-like appearance and 2-toned cytoplasm. A mixed inflammatory infiltrate including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes commonly is present (Figure 3). The epithelioid histiocytes are positive for vimentin and histiocytic markers including CD68 and CD163.22

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is an uncommon mesenchymal fibroblastic neoplasm that can arise at almost any anatomic site.24 Cutaneous SFTs are more common in women, most often involve the head, and appear to behave in an indolent manner.25 Solitary fibrous tumors are translocation-associated neoplasms with a NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion.26 The classic histology of SFT is a spindled fibroblastic proliferation arranged in a "patternless pattern" with interspersed stag horn-like, thin-walled blood vessels (Figure 4). Tumor cells usually are positive for CD34, CD99, and Bcl-2.27 In addition, STAT6 immunoreactivity is useful in diagnosis of SFT.25

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

- Jones EW, Cerio R, Smith NP. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma: a new entity. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:185-195.

- Singh Gomez C, Calonje E, Fletcher CD. Epithelioid benign fibrous histiocytoma of skin: clinico-pathological analysis of 20 cases of a poorly known variant. Histopathology. 1994;24:123-129.

- Felty CC, Linos K. Epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a concise review [published online October 4, 2018]. Am J Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001272.

- Rawal YB, Kalmar JR, Shumway B, et al. Presentation of an epithelioid cell histiocytoma on the ventral tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:75-83.

- Cangelosi JJ, Prieto VG, Baker GF, et al. Unusual presentation of multiple epithelioid cell histiocytomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:373-376.

- Doyle LA, Marino-Enriquez A, Fletcher CD, et al. ALK rearrangement and overexpression in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:904-912.

- Silverman JS, Glusac EJ. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma--histogenetic and kinetics analysis of dermal microvascular unit dendritic cell subpopulations. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:415-422.

- Murigu T, Bhatt N, Miller K, et al. Spindle cell-predominant epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:1233-1236.

- Rabkin MS, Vukmer T. Granular cell variant of epithelioid cell histiocytoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:766-769.

- Glusac EJ, Barr RJ, Everett MA, et al. Epithelioid cell histiocytoma. a report of 10 cases including a new cellular variant. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:583-590.

- Creytens D, Ferdinande L, Van Dorpe J. ALK Rearrangement and overexpression in an unusual cutaneous epithelioid tumor with a peculiar whorled "perineurioma-like" growth pattern: epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:E46-E48.

- Doyle LA, Fletcher CD. EMA positivity in epithelioid fibrous histiocytoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:697-703.

- Fabrizi G, Massi G. Polypoid Spitz naevus: the benign counterpart of polypoid malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:128-132.

- Plaza JA, De Stefano D, Suster S, et al. Intradermal Spitz nevi: a rare subtype of Spitz nevi analyzed in a clinicopathologic study of 74 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:283-294; quiz 295-287.

- Menezes FD, Mooi WJ. Spitz tumors of the skin. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:281-298.

- Requena C, Requena L, Kutzner H, et al. Spitz nevus: a clinicopathological study of 349 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:107-116.

- Mentzel T, Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, et al. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104-113.

- Aung PP, Goldberg LJ, Mahalingam M, et al. Cutaneous myopericytoma: a report of 3 cases and review of the literature. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2015;2:9-14.

- Morzycki A, Joukhadar N, Murphy A, et al. Digital myopericytoma: a case report and systematic literature review. J Hand Microsurg. 2017;9:32-36.

- LeBlanc RE, Taube J. Myofibroma, myopericytoma, myoepithelioma, and myofibroblastoma of skin and soft tissue. Surg Pathol Clin. 2011;4:745-759.

- Chisolm SS, Schulman JM, Fox LP. Adult xanthogranuloma, reticulohistiocytosis, and Rosai-Dorfman disease. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:465-472; discussion 473.

- Miettinen M, Fetsch JF. Reticulohistiocytoma (solitary epithelioid histiocytoma): a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:521-528.

- Cohen PR, Lee RA. Adult-onset reticulohistiocytoma presenting as a solitary asymptomatic red knee nodule: report and review of clinical presentations and immunohistochemistry staining features of reticulohistiocytosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014. pii:doj_21725.

- Soldano AC, Meehan SA. Cutaneous solitary fibrous tumor: a report of 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:54-58.

- Feasel P, Al-Ibraheemi A, Fritchie K, et al. Superficial solitary fibrous tumor: a series of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:778-785.

- Thway K, Ng W, Noujaim J, et al. The current status of solitary fibrous tumor: diagnostic features, variants, and genetics. Int J Surg Pathol. 2016;24:281-292.

- Erdag G, Qureshi HS, Patterson JW, et al. Solitary fibrous tumors of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:844-850.

A 28-year-old man presented with a growing asymptomatic papule on the right leg.

Severe Pretibial Myxedema Refractory to Systemic Immunosuppressants

To the Editor:

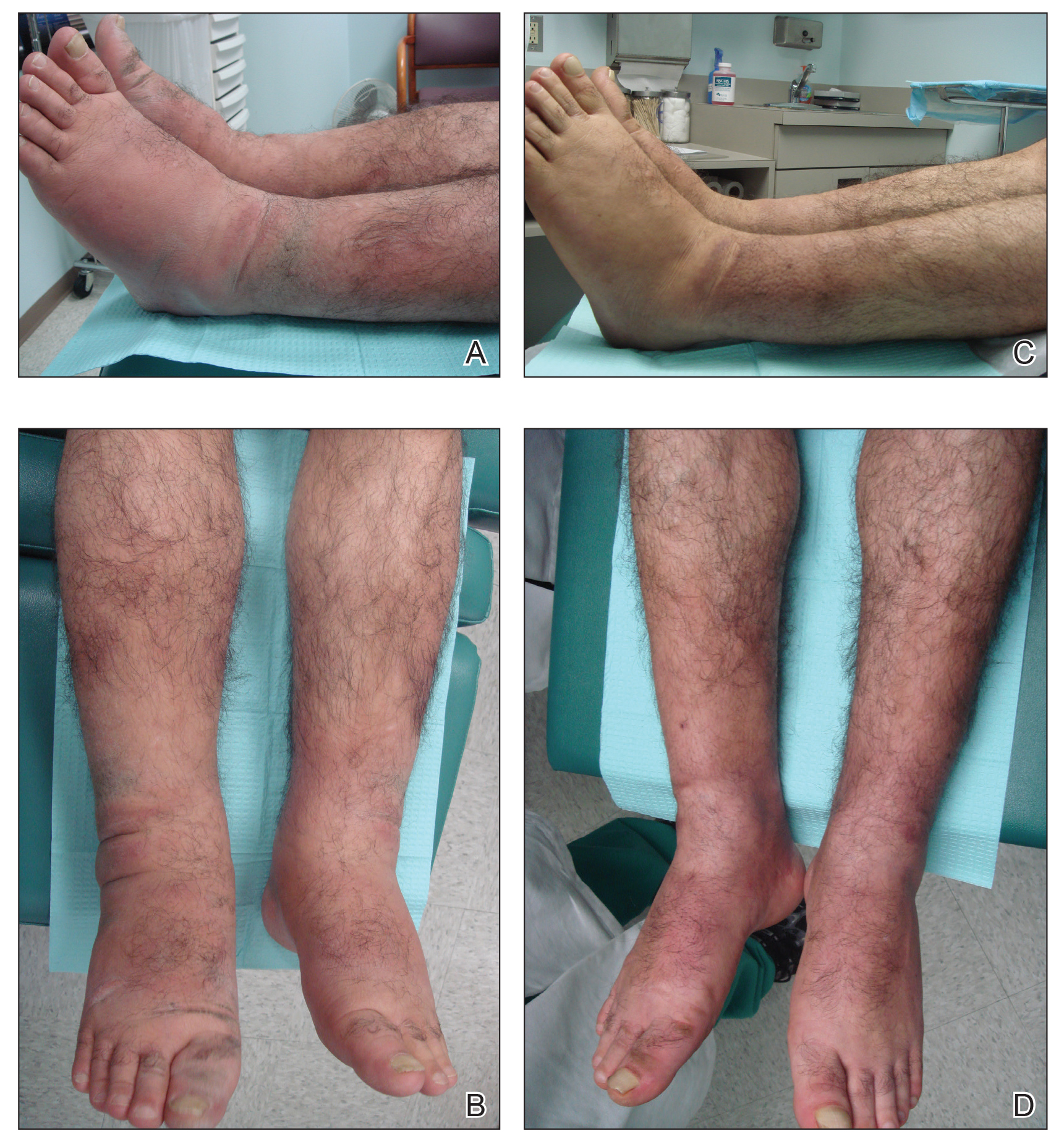

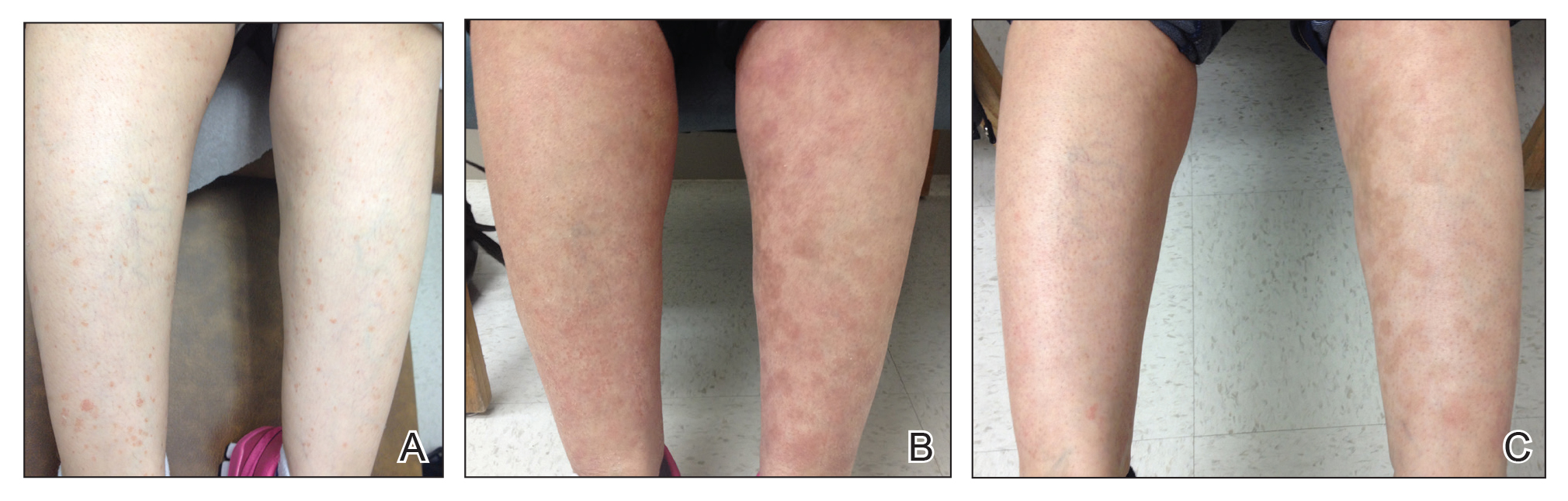

A 55-year-old man with a history of Graves disease treated with radioactive iodine and Graves ophthalmopathy was referred to our dermatology clinic by his endocrinologist with a 2-year history of severe pretibial myxedema (PM) that had failed treatment with systemic immunosuppressants after diagnosis by an outside dermatologist in the United Kingdom approximately 2 years prior. In addition to burning pain and difficulty walking associated with progressive “enlarging” of the lower legs and feet (Figure, A and B), the patient reported that he consistently had to find larger shoes (size 13 at the current presentation). His medications included gabapentin for foot pain and levothyroxine for hypothyroidism.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, waxy, indurated, flesh-colored and erythematous plaques and nodules with a peau d’orange appearance on the dorsal feet, ankles, and lower legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin level of 617% (reference range, <140%) and mild anemia. His thyroid stimulating hormone and free T4 levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were all within reference range.

Treatment with oral, intravenous, and intralesional steroids; cyclosporine; and azathioprine were tried prior to presentation to our clinic with no improvement. The patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily), intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 mg/mL every 3–4 weeks), clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion twice daily, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings (20–30 mm Hg). The baseline circumference of the extremities also were measured (right ankle, 12 in; left ankle, 11.5 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 12 in).

At 3-week follow-up, the lesions had flattened with softening of the skin. The patient reported his legs were smaller and he had bought a new pair of shoes at size 8.5 (Figure, C). He noted less pain and difficulty with walking. The circumference of the extremities was measured again (right ankle, 10.2 in; left ankle, 10 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 10.5 in). The patient continued treatment and was followed for 3 months. At each visit, clinical improvement was noted as well as report of decreased pain while walking (Figure, D).

Pretibial myxedema is a known manifestation of Graves disease that almost always occurs in the presence of Graves ophthalmopathy. Pretibial myxedema occurs in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves disease and variably manifests as diffuse nonpitting edema or localized, waxy, indurated plaques or nodules.1,2

The proposed pathogenesis of PM is that autoantibodies directed against the thyroid receptors cross-react with the fibroblasts of the skin,2,3 which stimulates the fibroblasts to produce high amounts of glycosaminoglycans, especially hyaluronic acid, in the dermis and subcutis of the pretibial area. It is not known why there is a predilection for the anterior shins, but mechanical factors and dependent position (ie, leg position is lower than the level of the heart) may be involved.4

The mainstay of treatment for PM is topical and intralesional corticosteroids, which may have a benefit in mild to moderate disease; however, in cases of severe disease that is refractory to intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, more aggressive treatment is required. Systemic immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, and corticosteroids have proven useful in some but not all cases.5,6

Our patient did not respond to treatment with systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or azathioprine before he presented to our clinic; however, the lesions were dramatically improved after 3 weeks of treatment with pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings.

Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves ophthalmology and PM.7 It has been shown to reduce thickness of skin lesions when used in combination with topical or intralesional steroids.3,8 Corticosteroids are thought to block fibroblast-mediated glycosaminoglycan production.3,9 The deposition of mucin, which is comprised of glycosaminoglycans, expands the dermal tissue and causes fluid to accumulate; it also causes compression of dermal lymphatics, worsening the dermal edema. Because fluid accumulates, the use of short-stretch bandages and compression stockings may provide additional benefit, as was seen in our patient, whose shoe size decreased from a 13 to an 8.5 within 3 weeks of treatment.

In conclusion, the combination of pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression garments can cause substantial improvement in severe PM refractory to systemic immunosuppressants.

- Susser WS, Heermans AG, Chapman MS, et al. Elephantiasic pretibial myxedema: a novel treatment for an uncommon disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:723-726.

- Kriss J. Pathogenesis and treatment of pretibial myxedema. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16:409-415.

- Pineda AM, Tianco EA, Tan JB, et al. Oral pentoxifylline and topical clobetasol propionate ointment in the treatment of pretibial myxoedema, with concomitant improvement of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:1441-1443.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Benoit FL, Greenspan FS. Corticoid therapy for pretibial myxedema: observations on the long-acting thyroid stimulator. Ann Intern Med. 1967;66:711-720.

- Hanke CW, Bergfeld WF, Guirguis MN, et al. Pretibial myxedema (elephantiasis form): treatment with cytotoxic therapy. Cleve Clin Q. 1983;50:183-188.

- Chang CC, Chang TC, Kao SC, et al. Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxoedema. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993;129:322-327.

- Engin B, Gümüs¸el M, Ozdemir M, et al. Successful combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treatment of severe pretibial myxedema. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:16.

- Lang PG, Sisson JC, Lynch PJ. Intralesional triamcinolone therapy for pretibial myxedema. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:197-202.

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man with a history of Graves disease treated with radioactive iodine and Graves ophthalmopathy was referred to our dermatology clinic by his endocrinologist with a 2-year history of severe pretibial myxedema (PM) that had failed treatment with systemic immunosuppressants after diagnosis by an outside dermatologist in the United Kingdom approximately 2 years prior. In addition to burning pain and difficulty walking associated with progressive “enlarging” of the lower legs and feet (Figure, A and B), the patient reported that he consistently had to find larger shoes (size 13 at the current presentation). His medications included gabapentin for foot pain and levothyroxine for hypothyroidism.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, waxy, indurated, flesh-colored and erythematous plaques and nodules with a peau d’orange appearance on the dorsal feet, ankles, and lower legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin level of 617% (reference range, <140%) and mild anemia. His thyroid stimulating hormone and free T4 levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were all within reference range.

Treatment with oral, intravenous, and intralesional steroids; cyclosporine; and azathioprine were tried prior to presentation to our clinic with no improvement. The patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily), intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 mg/mL every 3–4 weeks), clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion twice daily, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings (20–30 mm Hg). The baseline circumference of the extremities also were measured (right ankle, 12 in; left ankle, 11.5 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 12 in).

At 3-week follow-up, the lesions had flattened with softening of the skin. The patient reported his legs were smaller and he had bought a new pair of shoes at size 8.5 (Figure, C). He noted less pain and difficulty with walking. The circumference of the extremities was measured again (right ankle, 10.2 in; left ankle, 10 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 10.5 in). The patient continued treatment and was followed for 3 months. At each visit, clinical improvement was noted as well as report of decreased pain while walking (Figure, D).

Pretibial myxedema is a known manifestation of Graves disease that almost always occurs in the presence of Graves ophthalmopathy. Pretibial myxedema occurs in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves disease and variably manifests as diffuse nonpitting edema or localized, waxy, indurated plaques or nodules.1,2

The proposed pathogenesis of PM is that autoantibodies directed against the thyroid receptors cross-react with the fibroblasts of the skin,2,3 which stimulates the fibroblasts to produce high amounts of glycosaminoglycans, especially hyaluronic acid, in the dermis and subcutis of the pretibial area. It is not known why there is a predilection for the anterior shins, but mechanical factors and dependent position (ie, leg position is lower than the level of the heart) may be involved.4

The mainstay of treatment for PM is topical and intralesional corticosteroids, which may have a benefit in mild to moderate disease; however, in cases of severe disease that is refractory to intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, more aggressive treatment is required. Systemic immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, and corticosteroids have proven useful in some but not all cases.5,6

Our patient did not respond to treatment with systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or azathioprine before he presented to our clinic; however, the lesions were dramatically improved after 3 weeks of treatment with pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings.

Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves ophthalmology and PM.7 It has been shown to reduce thickness of skin lesions when used in combination with topical or intralesional steroids.3,8 Corticosteroids are thought to block fibroblast-mediated glycosaminoglycan production.3,9 The deposition of mucin, which is comprised of glycosaminoglycans, expands the dermal tissue and causes fluid to accumulate; it also causes compression of dermal lymphatics, worsening the dermal edema. Because fluid accumulates, the use of short-stretch bandages and compression stockings may provide additional benefit, as was seen in our patient, whose shoe size decreased from a 13 to an 8.5 within 3 weeks of treatment.

In conclusion, the combination of pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression garments can cause substantial improvement in severe PM refractory to systemic immunosuppressants.

To the Editor:

A 55-year-old man with a history of Graves disease treated with radioactive iodine and Graves ophthalmopathy was referred to our dermatology clinic by his endocrinologist with a 2-year history of severe pretibial myxedema (PM) that had failed treatment with systemic immunosuppressants after diagnosis by an outside dermatologist in the United Kingdom approximately 2 years prior. In addition to burning pain and difficulty walking associated with progressive “enlarging” of the lower legs and feet (Figure, A and B), the patient reported that he consistently had to find larger shoes (size 13 at the current presentation). His medications included gabapentin for foot pain and levothyroxine for hypothyroidism.

Physical examination revealed diffuse, waxy, indurated, flesh-colored and erythematous plaques and nodules with a peau d’orange appearance on the dorsal feet, ankles, and lower legs. Laboratory evaluation revealed a thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin level of 617% (reference range, <140%) and mild anemia. His thyroid stimulating hormone and free T4 levels, a comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipid panel were all within reference range.

Treatment with oral, intravenous, and intralesional steroids; cyclosporine; and azathioprine were tried prior to presentation to our clinic with no improvement. The patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily), intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (5 mg/mL every 3–4 weeks), clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% under occlusion twice daily, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings (20–30 mm Hg). The baseline circumference of the extremities also were measured (right ankle, 12 in; left ankle, 11.5 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 12 in).

At 3-week follow-up, the lesions had flattened with softening of the skin. The patient reported his legs were smaller and he had bought a new pair of shoes at size 8.5 (Figure, C). He noted less pain and difficulty with walking. The circumference of the extremities was measured again (right ankle, 10.2 in; left ankle, 10 in; right and left mid-plantar feet, 10.5 in). The patient continued treatment and was followed for 3 months. At each visit, clinical improvement was noted as well as report of decreased pain while walking (Figure, D).

Pretibial myxedema is a known manifestation of Graves disease that almost always occurs in the presence of Graves ophthalmopathy. Pretibial myxedema occurs in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves disease and variably manifests as diffuse nonpitting edema or localized, waxy, indurated plaques or nodules.1,2

The proposed pathogenesis of PM is that autoantibodies directed against the thyroid receptors cross-react with the fibroblasts of the skin,2,3 which stimulates the fibroblasts to produce high amounts of glycosaminoglycans, especially hyaluronic acid, in the dermis and subcutis of the pretibial area. It is not known why there is a predilection for the anterior shins, but mechanical factors and dependent position (ie, leg position is lower than the level of the heart) may be involved.4

The mainstay of treatment for PM is topical and intralesional corticosteroids, which may have a benefit in mild to moderate disease; however, in cases of severe disease that is refractory to intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, more aggressive treatment is required. Systemic immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, and corticosteroids have proven useful in some but not all cases.5,6

Our patient did not respond to treatment with systemic and intralesional corticosteroids, cyclosporine, or azathioprine before he presented to our clinic; however, the lesions were dramatically improved after 3 weeks of treatment with pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression stockings.

Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves ophthalmology and PM.7 It has been shown to reduce thickness of skin lesions when used in combination with topical or intralesional steroids.3,8 Corticosteroids are thought to block fibroblast-mediated glycosaminoglycan production.3,9 The deposition of mucin, which is comprised of glycosaminoglycans, expands the dermal tissue and causes fluid to accumulate; it also causes compression of dermal lymphatics, worsening the dermal edema. Because fluid accumulates, the use of short-stretch bandages and compression stockings may provide additional benefit, as was seen in our patient, whose shoe size decreased from a 13 to an 8.5 within 3 weeks of treatment.

In conclusion, the combination of pentoxifylline, intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, short-stretch bandages, and compression garments can cause substantial improvement in severe PM refractory to systemic immunosuppressants.

- Susser WS, Heermans AG, Chapman MS, et al. Elephantiasic pretibial myxedema: a novel treatment for an uncommon disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:723-726.

- Kriss J. Pathogenesis and treatment of pretibial myxedema. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16:409-415.

- Pineda AM, Tianco EA, Tan JB, et al. Oral pentoxifylline and topical clobetasol propionate ointment in the treatment of pretibial myxoedema, with concomitant improvement of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:1441-1443.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Benoit FL, Greenspan FS. Corticoid therapy for pretibial myxedema: observations on the long-acting thyroid stimulator. Ann Intern Med. 1967;66:711-720.

- Hanke CW, Bergfeld WF, Guirguis MN, et al. Pretibial myxedema (elephantiasis form): treatment with cytotoxic therapy. Cleve Clin Q. 1983;50:183-188.

- Chang CC, Chang TC, Kao SC, et al. Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxoedema. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993;129:322-327.

- Engin B, Gümüs¸el M, Ozdemir M, et al. Successful combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treatment of severe pretibial myxedema. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:16.

- Lang PG, Sisson JC, Lynch PJ. Intralesional triamcinolone therapy for pretibial myxedema. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:197-202.

- Susser WS, Heermans AG, Chapman MS, et al. Elephantiasic pretibial myxedema: a novel treatment for an uncommon disorder. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:723-726.

- Kriss J. Pathogenesis and treatment of pretibial myxedema. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16:409-415.

- Pineda AM, Tianco EA, Tan JB, et al. Oral pentoxifylline and topical clobetasol propionate ointment in the treatment of pretibial myxoedema, with concomitant improvement of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21:1441-1443.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Benoit FL, Greenspan FS. Corticoid therapy for pretibial myxedema: observations on the long-acting thyroid stimulator. Ann Intern Med. 1967;66:711-720.

- Hanke CW, Bergfeld WF, Guirguis MN, et al. Pretibial myxedema (elephantiasis form): treatment with cytotoxic therapy. Cleve Clin Q. 1983;50:183-188.

- Chang CC, Chang TC, Kao SC, et al. Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of cultured fibroblasts derived from patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy and pretibial myxoedema. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1993;129:322-327.

- Engin B, Gümüs¸el M, Ozdemir M, et al. Successful combined pentoxifylline and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide treatment of severe pretibial myxedema. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:16.

- Lang PG, Sisson JC, Lynch PJ. Intralesional triamcinolone therapy for pretibial myxedema. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:197-202.

Practice Points

- Pretibial myxedema (PM) is a known manifestation of Graves disease that almost always occurs in the presence of Graves ophthalmopathy.

- The proposed pathogenesis of PM is cross-reaction of autoantibodies directed against the thyroid receptors with the fibroblasts of the skin. It is not known why there is a predilection for the anterior shins, but mechanical factors and dependent position may be involved.

- The mainstay of treatment for PM is topical and intralesional corticosteroids, which may have a benefit in mild to moderate disease; however, in cases of severe disease that is refractory to intralesional and topical corticosteroids under occlusion, more aggressive treatment is required.

Painful and Pruritic Erosions on the Back

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

The Diagnosis: Bullous Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (BSLE) is a rare blistering disease that affects patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Our patient had a several-year history of SLE and was being managed by a rheumatologist. She was taking hydroxychloroquine at the time of the flare. Although BSLE tends to present in those with SLE that has already been diagnosed, BSLE has been reported as a possible initial manifestation of SLE.1

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus is estimated to occur in less than 5% of patients with SLE and is more common in black women between the second and third decades of life,2 though it also can be seen in the pediatric population.3 The lesions of BSLE usually present as subepidermal blisters often located on the face, neck, and arms on an erythematous or possibly urticarial base. Although non-BSLE vesiculobullous eruptions may be seen in patients with SLE, BSLE is differentiated from these other eruptions by its appearance on sun-exposed and non-sun-exposed areas of the body, while other vesiculobullous eruptions associated with SLE typically are limited to sun-exposed sites.4

Due to its clinical presentation overlapping with several vesiculobullous conditions, a set of diagnostic criteria have been suggested for BSLE, including the following: (1) fulfillment of the American Rheumatism Association's criteria for SLE5; (2) a new-onset vesiculobullous eruption, primarily on sun-exposed skin; (3) histology showing a subepidermal blister with a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate; (4) presence of IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3 at the basement membrane zone; (5) evidence of antibodies to type VII collagen; and (6) immunoelectron microscopy showing codistribution of immunoglobulin deposits with anchoring fibrils/type VII collagen. To meet the diagnosis of type I BSLE, all 6 criteria must be satisfied. To meet the diagnosis of type II BSLE, only criteria 1 to 4 need to be satisfied.6

Patients with BSLE may be presumed to have a different but clinically similar vesiculobullous condition (eg, bullous pemphigoid, cutaneous manifestations of SLE) and may be started on systemic corticosteroids. However, BSLE patients often do not show great improvement while on corticosteroids and may even flare shortly after beginning systemic corticosteroid treatment. The current treatment of choice for BSLE is dapsone, a sulfa drug that is thought to exhibit its anti-inflammatory properties via the inhibition of the alternative pathway of the complement system and through the inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions.7 A response to dapsone helps differentiate BSLE from histopathologically and immunopathologically identical conditions such as epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.4 Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus can be differentiated from dermatitis herpetiformis with the presence of antigliadin and antitissue transglutaminase antibodies, which are found in the latter. Additionally, BSLE may show the presence of IgG and IgM deposition in addition to IgA deposition, as opposed to dermatitis herpetiformis where only IgA is found.8 The presence of these additional antibody depositions also help differentiate BSLE from linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD), as LABD will only have IgA depositions and often presents with an annular, crown of jewels-like appearance. Finally, there is a well-described phenomenon of LABD being drug induced, particularly after a course of vancomycin,9 and such an association with vancomycin has not been documented for BSLE.

Our patient was diagnosed with BSLE following the flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. She had been started on dapsone 75 mg daily at that time and was taking 75 mg at the time of presentation. She was admitted and treated as an inpatient with high-dose (1 mg/kg) intravenous prednisone due to the extensive current flare.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

- Fujimoto W, Hamada T, Yamada J, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus as an initial manifestation of SLE. J Dermatol. 2005;32:1021-1027.

- Miziara ID, Mahmoud A, Chagury AA, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: case report. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;17:344-346.

- Tincopa M, Puttgen KB, Sule S, et al. Bullous lupus: an unusual initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus in an adolescent girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27:373-376.

- Grover C, Khurana A, Sharma S, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:492.

- Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of RheumatologyClassification Criteria for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus [published online August 6, 2019]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412.

- Gammon WR, Briggaman RA. Bullous SLE: a phenotypically distinctive but immunologically heterogeneous bullous disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:28S-34S.

- Duan L, Chen L, Zhong S, et al. Treatment of bullous systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015:6.

- Barbosa WS, Rodarte CM, Guerra JG, et al. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: differential diagnosis with dermatitis herpetiformis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(4 suppl 1):S92-S95.

- Yordanova I, Valtchev V, Gospodinov D, et al. IgA linear bullous dermatosis in childhood. J IMAB. 2015;21:1012-1014.

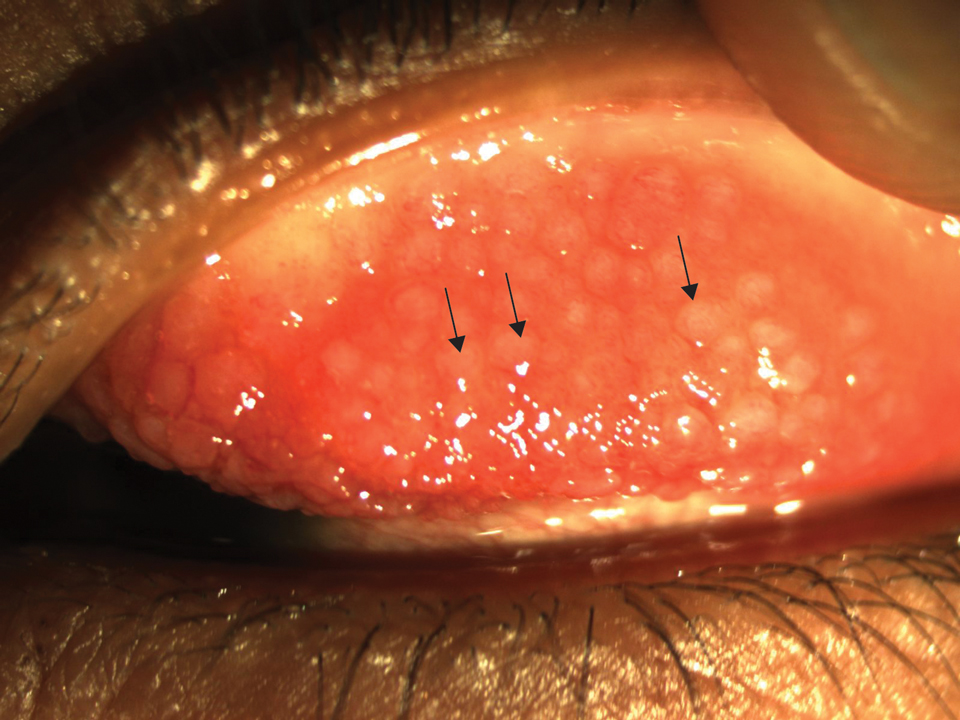

A 51-year-old black woman presented to the dermatology clinic with painful and pruritic erosions on the back, abdomen, neck, and arms of approximately 2 months' duration. The lesions started on the back and spread in a cephalocaudal manner. The patient denied any new changes in medication. Physical examination revealed large erosions with mild weeping of serosanguineous fluid on the back, abdomen, neck, and upper extremities. A few tense bullae were present on the dorsal aspect of the right hand. She had experienced a similar flare approximately 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. At that time, 2 shave biopsies from vesiculobullous lesions on the right side of the neck were sent for hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence. Biopsy results showed a subepidermal blister that extended along the course of the hair follicle and was associated with an infiltrate of neutrophilic granulocytes that also extended along the course of the hair follicle. Direct immunofluorescence showed IgG and C3 deposition in the basement membrane zone extending along the floor of the blister where the epidermis was separated from the dermis.

Sniffing Out Malignant Melanoma: A Case of Canine Olfactory Detection

To the Editor:

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

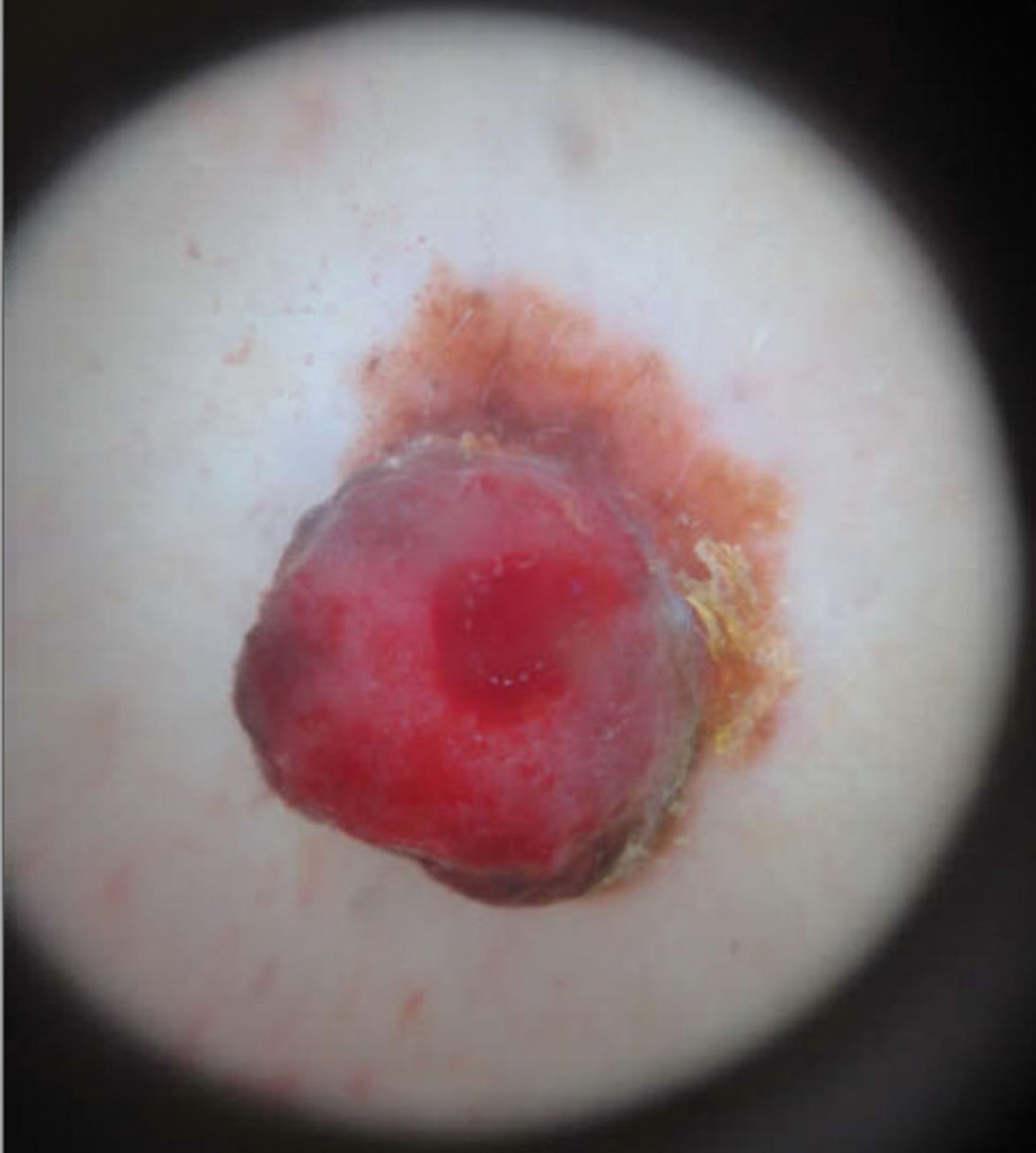

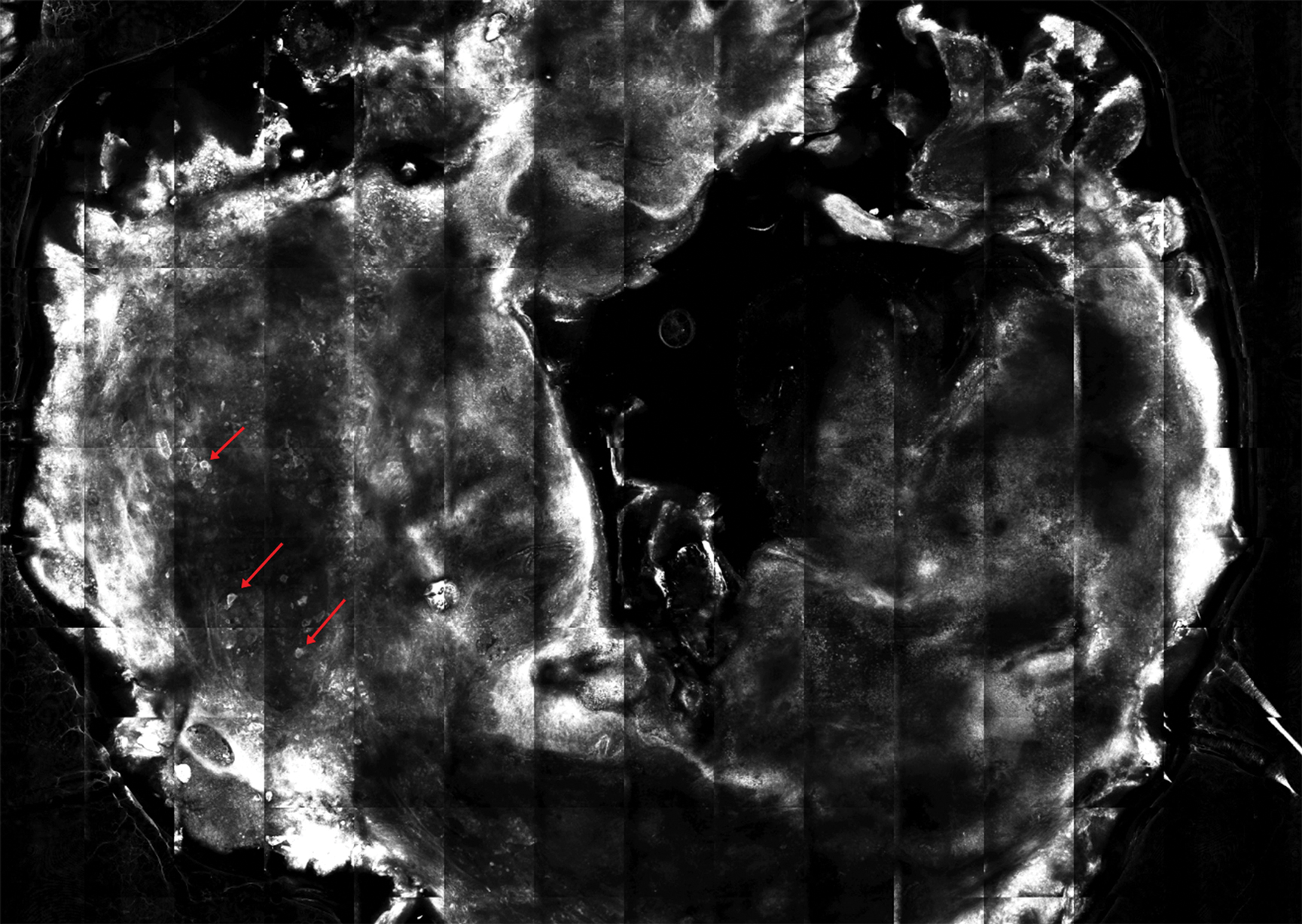

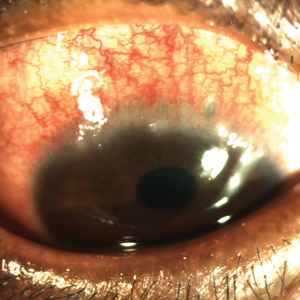

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1

Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide compounds have been identified in malignant melanoma, and these compounds are not produced by normal melanocytes.7 Furthermore, malignant melanoma produces differing quantities of these compounds as compared to normal melanocytes, including isovaleric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), and 2-methyl-1-butanol, resulting in a distinct odorant profile that previously has been detected via canine olfaction.7 Canine olfaction can identify odorant molecules at up to 1 part per trillion (a magnitude more sensitive than the currently available gas chromatography–mass spectrometry technologies) and can detect the production of new VOCs or altered VOC ratios due to pathologic processes.1 Systematic studies with dogs that are trained to detect cancers in humans have shown that canine olfaction correctly identified malignant melanomas against healthy skin, benign nevi, and even basal cell carcinomas at higher rates than what would have been expected by chance alone.2,3

Canine olfaction can identify new or altered ratios of odorant VOCs associated with pathologic metabolic processes, and canines can be trained to target odor profiles associated with specific diseases.1 Canine olfaction for melanoma screening and diagnosis may seem appealing, as it provides an easily transportable, real-time, low-cost method compared to other techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.1 Although preliminary results have shown that canine olfaction detects melanoma at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone, these findings have not approached clinical utility for the widespread use of canine olfaction as a screening method for melanoma.2,3,9 Further studies are needed to understand the role of canine olfaction in melanoma screening and diagnosis as well as to explore methods to optimize sensitivity and specificity. Until then, patients and dermatologists should not ignore the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Dogs may be beneficial in the detection of melanoma and help save lives, as was seen in our case.

- Angle C, Waggoner LP, Ferrando A, et al. Canine detection of the volatilome: a review of implications for pathogen and disease detection. Front Vet Sci. 2016;3:47.

- Pickel D, Mauncy GP, Walker DB, et al. Evidence for canine olfactory detection of melanoma. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2004;89:107-116.

- Willis CM, Britton LE, Swindells MA, et al. Invasive melanoma in vivo can be distinguished from basal cell carcinoma, benign naevi and healthy skin by canine olfaction: a proof‐of‐principle study of differential volatile organic compound emission. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1020-1029.

- Jezierski T, Walczak M, Ligor T, et al. Study of the art: canine olfaction used for cancer detection on the basis of breath odour. perspectives and limitations. J Breath Res. 2015;9:027001.

- Williams H, Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;1:734.

- Campbell LF, Farmery L, George SM, et al. Canine olfactory detection of malignant melanoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008566.

- Kwak J, Gallagher M, Ozdener MH, et al. Volatile biomarkers from human melanoma cells. J Chromotogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2013;931:90-96.

- D’Amico A, Bono R, Pennazza G, et al. Identification of melanoma with a gas sensor array. Skin Res Technol. 2008;14:226-236.

- Elliker KR, Williams HC. Detection of skin cancer odours using dogs: a step forward in melanoma detection training and research methodologies. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:851-852.

To the Editor:

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.

She reported no personal history of melanoma or nonmelanoma skin cancer, tanning booth exposure, blistering sunburns, or use of immunosuppressant medications. Her family history was remarkable for basal cell carcinoma in her father but no family history of melanoma. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×1.5-cm brown patch along with a 1×1-cm ulcerated nodule on the lower aspect of the lesion (Figure 1). Dermoscopy showed a blue-white veil and an irregular vascular pattern (Figure 2). No cervical, axillary, or inguinal lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. Reflectance confocal microscopy showed pagetoid spread of atypical round melanocytes as well as melanocytes in the stratum corneum (Figure 3).

The patient was referred to a surgical oncologist for wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Pathology showed a 4-mm-thick melanoma with numerous positive lymph nodes (Figure 4). The patient subsequently underwent a right axillary lymphadenectomy and was diagnosed with stage IIIB malignant melanoma. After surgery, the patient reported that her dog would now sniff her back and calmly rest his head in her lap.

She was treated with ipilimumab but subsequently developed panhypopituitarism, so she was taken off the ipilimumab. Currently, the patient is doing well. She follows up annually for full-body skin examinations and has not had any recurrence in the last 7 years. The patient credits her dog for prompting her to see a dermatologist and saving her life.

Both anecdotal and systematic evidence have emerged on the role of canine olfaction in the detection of lung, breast, colorectal, ovarian, prostate, and skin cancers, including malignant melanoma.1-6 A 1989 case report described a woman who was prompted to seek dermatologic evaluation of a pigmented lesion because her dog consistently targeted the lesion. Excision and subsequent histopathologic examination of the lesion revealed that it was malignant melanoma.5 Another case report described a patient whose dog, which was not trained to detect cancers in humans, persistently licked a lesion behind the patient’s ear that eventually was found to be malignant melanoma.6 These reports have inspired considerable research interest regarding canine olfaction as a potential method to noninvasively screen for and even diagnose malignant melanomas in humans.

Both physiologic and pathologic metabolic processes result in the production of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), or small odorant molecules that evaporate at normal temperatures and pressures.1 Individual cells release VOCs in extremely low concentrations into the blood, urine, feces, and breath, as well as onto the skin’s surface, but there are methods for detecting these VOCs, including gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and canine olfaction.7,8 Pathologic processes, such as infection and malignancy, result in irregular protein synthesis and metabolism, producing new VOCs or differing concentrations of VOCs as compared to normal processes.1

Dimethyl disulfide and dimethyl trisulfide compounds have been identified in malignant melanoma, and these compounds are not produced by normal melanocytes.7 Furthermore, malignant melanoma produces differing quantities of these compounds as compared to normal melanocytes, including isovaleric acid, 2-methylbutyric acid, isoamyl alcohol (3-methyl-1-butanol), and 2-methyl-1-butanol, resulting in a distinct odorant profile that previously has been detected via canine olfaction.7 Canine olfaction can identify odorant molecules at up to 1 part per trillion (a magnitude more sensitive than the currently available gas chromatography–mass spectrometry technologies) and can detect the production of new VOCs or altered VOC ratios due to pathologic processes.1 Systematic studies with dogs that are trained to detect cancers in humans have shown that canine olfaction correctly identified malignant melanomas against healthy skin, benign nevi, and even basal cell carcinomas at higher rates than what would have been expected by chance alone.2,3

Canine olfaction can identify new or altered ratios of odorant VOCs associated with pathologic metabolic processes, and canines can be trained to target odor profiles associated with specific diseases.1 Canine olfaction for melanoma screening and diagnosis may seem appealing, as it provides an easily transportable, real-time, low-cost method compared to other techniques such as gas chromatography–mass spectrometry.1 Although preliminary results have shown that canine olfaction detects melanoma at higher rates than would be expected by chance alone, these findings have not approached clinical utility for the widespread use of canine olfaction as a screening method for melanoma.2,3,9 Further studies are needed to understand the role of canine olfaction in melanoma screening and diagnosis as well as to explore methods to optimize sensitivity and specificity. Until then, patients and dermatologists should not ignore the behavior of dogs toward skin lesions. Dogs may be beneficial in the detection of melanoma and help save lives, as was seen in our case.

To the Editor:

A 43-year-old woman presented with a mole on the central back that had been present since childhood and had changed and grown over the last few years. The patient reported that her 2-year-old rescue dog frequently sniffed the mole and would subsequently get agitated and try to scratch and bite the lesion. This behavior prompted the patient to visit a dermatologist.