User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Solar Urticaria Treated With Omalizumab

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

To the Editor:

First documented in 1904,1 solar urticaria is an IgE-induced condition that predominantly occurs in women aged 20 to 50 years. Worldwide prevalence and incidence information is lacking, but it is known to occur in up to 0.4% of urticaria cases.2 Solar urticaria is characterized by pruritus of the skin with erythematous wheals and flares in reaction to sunlight exposure, even despite partial protection by barriers such as glass or clothing.2,3 It can have an acute or chronic presentation caused by visible or UV light wavelengths. Solar urticaria can lead to debilitating symptoms and psychological stressors that can severely impact a patient’s well-being and also may be accompanied by conditions such as polymorphous light eruption, angioedema, or vasculitis.4 Standard treatments include first- and second-generation antihistamines, which are efficacious approximately 50% of the time, as well as phototherapy, which can be time consuming and a burden on patients who work or go to school full time.2 Other possible treatment modalities include plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids, cyclosporine, and anti-IgE recombinant monoclonal antibody injections.5,6 We present the case of a patient who was successfully treated with subcutaneous injections of omalizumab every 3 weeks to add to the growing number of case reports of treatment of solar urticaria.

A 30-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type III and a 9-year history of solar urticaria was referred to the Department of Allergy and Immunology by her primary care physician. The patient reported that redness, swelling, and itching would occur on sun-exposed areas of the skin after approximately 10 minutes of exposure despite daily sunscreen application. She had been successfully treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg once daily after her first formal evaluation by dermatology 4 years prior to the current presentation. She subsequently self-discontinued treatment after 8 months of treatment due to resolution of symptoms. She noted the symptoms had returned upon relocating to Hawaii after living in the continental United States and Italy. Initially she was restarted on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg once daily and 4-times the recommended daily dose of second-generation antihistamines without relief. The hydroxychloroquine dosage subsequently was increased to 400 mg once daily, but her symptoms did not resolve.

On physical examination, sun-exposed areas of the skin showed marked macular erythema with discrete erythematous lines of demarcation observed between exposed and unexposed skin. The patient also reported concomitant pruritus, which antihistamines did not alleviate. A maximum 1-year course of cyclosporine 300 mg once daily initially was planned but was discontinued due to immediate onset of severe nausea and emesis after the first dose as well as continued outbreaks of urticaria for 1 month after incrementally increasing by 100 mg from a starting dose of 100 mg.

After discussion with the dermatology department, a trial of omalizumab was started because the daily impact of a UV light sensitization course was not feasible with her work schedule, and serum IgE blood level was 560.4 µg/L (reference range, 0–1500 µg/L). The patient was started on a regimen of omalizumab 300 mg (subcutaneous injections) every 2 weeks with noted improvement after the third dose, with no urticarial symptoms after sun exposure. After 2 months, the dosage interval was increased to every 4 weeks given her level of improvement, but her symptoms recurred. The treatment regimen was then changed to every 3 weeks. The patient was symptom free for a period of 10 months on this regimen, followed by only 1 outbreak of erythema and urticaria, which occurred 1 day prior to a scheduled omalizumab injection. Symptoms have otherwise been well controlled to date on omalizumab.

Solar urticaria is a poorly understood phenomenon that has no clear prognostic indicators; therefore, diagnosis often is made based on the patient’s history and physical examination. Further testing to confirm the diagnosis can be performed using specific wavelengths of UV light to determine which band of light affects patients most; however, the wavelength can change over time, leading to less clinical significance, and may decrease efficacy of phototherapy.2 Solar urticaria has no clear predisposing factors, and treatments to date have been moderately successful. Exposure to sunlight is thought to initiate an alteration in a skin or serum chromophore or photoallergen, which then causes subsequent cross-linking and IgE-dependent release of histamine as well as other mediators such as cytokines, eicosanoids, and proteases with mast cell degranulation.7

Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody targeting the methylated IgE Cε3 domain that initially was marketed toward controlling IgE-mediated moderate to severe asthma recalcitrant to standard treatments. It has since received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria after first being noticed to serendipitously treat a patient with cold urticaria and asthma in 2006.4,7,8 It was then first documented to successfully treat solar urticaria in 2008.6 The safety profile of omalizumab makes it a more favorable choice when compared to other immunomodulating treatments, with the most serious adverse reaction being anaphylaxis, occurring in 0.2% of patients in a postmarketing study.9 It functions through binding to free IgE at a region necessary for IgE to bind at low- and high-affinity receptors but not to immunoglobulins already bound to cells, thus theoretically preventing activation of mast cells or basophils.10 It also has been suggested that low steady-state values are needed to see continued benefit from the drug,10 which may have been seen in our patient after having an outbreak just prior to receiving an injection; however, prior reports have shown benefit unrelated to total IgE levels, with improvement after days to 4 months.4,10,11 One case report showed no response after 4 doses; it is unknown if this patient was tested for clinical improvement to omalizumab through further immunoglobulin analysis, but treatment response is important to consider when deciding on whether to use this drug in future patients.12 It is unknown why some patients will respond to omalizumab, others will partially respond, and others will not respond, which can be ascertained either through quality-of-life improvement or lack thereof.

In our experience, omalizumab is a viable option to consider in patients with solar urticaria that is recalcitrant to standard treatments and elevated IgE levels for whom other treatments are either too time consuming or have side-effect profiles that are not tolerable to the patient. If the patient has concomitant asthma, there may be additional therapeutic benefit. Further research is needed with regard to a cost-benefit analysis of omalizumab and whether using such a costly drug outweighs the cost associated with time and resources utilized with repeat clinic visits if other standard treatments are not effective.13

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

- Merkin P. Pratique Dermatologique. Paris, France: Masso; 1904.

- Beattie PE, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of idiopathic solar urticaria: a cohort of 87 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1149-1154.

- Kaplan AP. Therapy of chronic urticaria: a simple, modern approach. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112:419-425.

- Metz M, Maurer M. Omalizumab in chronic urticaria. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:406-410.

- Aubin F, Porcher R, Jeanmougin M, et al. Severe and refractory solar urticaria treated with intravenous immunoglobulins: a phase II multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:948-953.e1.

- Güzelbey O, Ardelean E, Magerl M, et al. Successful treatment of solar urticaria with anti-immunoglobulin E therapy. Allergy. 2008;63:1563-1565.

- Wu K, Jabbar-Lopez Z. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE mAb, receives approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic/spontaneous urticaria. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:13-15.

- Boyce JA. Successful treatment of cold-induced urticaria/anaphylaxis with anti-IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117:1415-1418.

- Corren J, Casale TB, Lanier B, et al. Safety and tolerability of omalizumab. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:788-797.

- Wu K, Long H. Omalizumab for chronic urticaria. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2527-2528.

- Morgado-Carrasco D, Giacaman-Von der Weth M, Fusta-Novell X, et al. Clinical response and long-term follow-up of 20 patients with refractory solar urticarial under treatment with omalizumab [published online May 28, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.05.070.

- Duchini G, Bäumler W, Bircher AJ, et al. Failure of omalizumab (Xolair®) in the treatment of a case of solar urticaria caused by ultraviolet A and visible light. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2011;27:336-337.

- Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1270-1277.

Practice Points

- Recurrent solar urticaria can be recalcitrant to treatment.

- Omalizumab may be an effective treatment option for solar urticaria, especially in patients with a concomitant asthma diagnosis.

Painless Purple Streaks on the Arms and Chest

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

The Diagnosis: Factitial Purpura

Factitial dermatologic disorders are characterized by skin findings triggered by deliberate manipulation of the skin with objects to create lesions and feign signs of a dermatologic condition to seek emotional and psychological benefit.1 The etiology of the lesions is unclear, and the patient's history of the injury is hollow.2 Most often, there is sudden onset of the lesions without any warning or symptoms. When giving the history, the patient may appear unemotional, does not report pain, and denies self-infliction.1

In factitial purpura, the purple patches are clearly demarcated from uninvolved skin and have an unusual angular or geometric shape. The pattern typically takes the shape of the object used to create the purpura and lacks the features of recognizable dermatoses.2 In our patient and those with similar linear purpuric streaks, we use the term penny purpura to indicate that the lesions resulted from rubbing with a penny or other blunt object, similar to coining. The lesions occur in areas that are easily accessible and visible such as the arms, chest, or chin. It is suggested that the child unconsciously wants the lesions to be seen. Histologic findings in factitial purpura include disruption of collagen fiber bundles and extravasated red blood cells in the dermis.3 Unfortunately, evolving lesions may give nonspecific histologic findings; when the clinical lesions are typical, skin biopsy usually is unnecessary and may be misleading. Laboratory test results such as complete blood cell count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time usually are within reference range, as in our patient.

When evaluating these patients, confrontation is not recommended. More than two-thirds of affected patients have a history of trauma such as sexual/physical abuse or neglect, and the lesions typically arise during times of stress.1,3 Thus, treatment includes nonaccusatory measures and referral for psychologic evaluation. The purpura will rapidly heal when covered with an occlusive dressing.2

The differential diagnosis for penny purpura includes lesions that evolve from cupping and coining. Cupping is a type of complementary and alternative medicine that acts by correcting imbalances in the internal biofield and restoring the flow of qi, which determines the state of one's health and life span.4 Cupping is performed by placing a glass cup over a painful body part. A partial vacuum is created by flaming, mechanical withdrawal, or thermal cooling of the entrapped air under the cup. When the flame exhausts the supply of oxygen, the skin is sucked into the mouth of the glass, and the skin is bruised painlessly.4

The differential also includes child maltreatment syndrome and other disorders that would potentiate bruising. Intravascular etiologies include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, leukemia, coagulation disorders, and other causes of thrombocytopenia or platelet dysfunction.3 Extravascular etiologies include hereditary collagen vascular disease (eg, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), malnutrition, and other disorders associated with a decrease in collagen and other tissues that support cutaneous vessels. Vascular etiologies include infectious (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, meningococcemia) and noninfectious vasculitis (eg, Henoch-Schönlein purpura), leaky capillary syndrome, drug reactions, and other disorders associated with a loss of vascular integrity.3

It is important to be able to differentiate self-inflicted lesions in a person who repeatedly acts as if he/she has a physical disorder from those that are created during the practices of cupping or any other cultural healing practice. Vascular disorders, malnutrition, and child abuse also should be excluded.3

For our patient with factitial purpura, we gently encouraged the family to work with the child's pediatrician and a pediatric psychologist to deal with stress related to the recurrent rash and asked them to think of the rash as a result of an external cause; however, we were careful not to blame anyone for the rash.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

- Harth W, Taube KM, Gieler U. Facticious disorders in dermatology. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:361-372; quiz 373.

- Al Hawsawi K, Pope E. Pediatric psychocutaneous disorders: a review of primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:247-257.

- Ring HC, Miller IM, Benfeldt E, et al. Artefactual skin lesions in children and adolescents: review of the literature and two cases of factitious purpura. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:E27-E32.

- Mehta P, Dhapte V. Cupping therapy: a prudent remedy for a plethora of medical ailments. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015;5:127-134.

A 10-year-old boy presented with painless purple streaks on the arms and chest of 2 months' duration. The rash recurred several times per month and cleared without treatment in 3 to 5 days. There was no history of trauma or medication exposure, and he was growing and developing normally.

Scrotal Ulceration: A Complication of Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy and Subsequent Treatment With Dimethyl Sulfoxide

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

To the Editor:

A 54-year-old man with a history of stage IV appendiceal carcinoid adenocarcinoma treated approximately 3 months prior with intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) presented to our clinic with scrotal pain of 5 days’ duration. He had no history of genital herpes, topical contactants, other cutaneous lesions on the body, fever, or chills. On physical examination the patient had an erythematous, purpuric, indurated, tender plaque on the left anterolateral and anterior midline of the scrotum (Figure 1). No other areas of acral purpura or livedoid cutaneous changes were identified. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Biopsy was performed for histologic examination as well as tissue culture. Histology demonstrated epidermal necrosis without evidence of vasculitis. Tissue culture was unremarkable.

Two days after clinic evaluation, the patient presented to the emergency department with progression of the lesions, and he was admitted to the hospital for pain control. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed bilateral hydroceles without evidence of abscess. Ultrasonography showed scrotal thickening without abscess or fluid collection. On day 5 in the hospital, a regimen of topical 60% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was applied every 8 hours to the affected area. The patient experienced notable pain relief and a decrease in erythema within 7 hours of application (Figure 2). This regimen was continued for 7 days with improvement in surrounding erythema and pain; however, the patient’s pain persisted in the areas of necrosis. Fourteen days following completion of therapy (27 days following presentation), the patient underwent debridement and partial scrotal resection for eschar removal. Histologic examination of the debrided scrotal tissue showed necrosis extending into the dermis and no evidence of vasculitis.

Our case demonstrates a unique presentation of scrotal necrosis secondary to mitomycin C (MitC) extravasation subsequently managed with DMSO. Imaging and biopsy findings effectively ruled out infection or vasculitis and led us to consider extravasation reactions that typically occur at peripheral intravenous (IV) infusion sites. Suspected cases of scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC have been reported in the literature, along with hypothesized pathophysiology.1-3

In consideration of the proposed pathophysiology, individuals with hydroceles may be more likely to experience this complication due to an abnormal but not uncommon communication between the intraperitoneal cavity and the scrotum via a patent processus vaginalis. The location of necrosis on the anterior scrotum remains unexplained. It may be a consequence of the anatomic location of the hydrocele, a collection of fluid within the tunica vaginalis. The tunica vaginalis is composed of an inner visceral and outer parietal layer, enveloping the testis at the anterior border but not the superior or posterior border. Thus, sequestration of MitC in a hydrocele would correlate anatomically to necrosis of the anterior wall of the scrotum.

Akhavan et al1 proposed the testes are unaffected because of the presence of the tough fibrous coat of the tunica albuginea that directly adheres to the testes, in addition to the adjacent visceral layer of the tunica vaginalis. These 2 layers separating the testes and the hydrocele may provide a double barrier of protection for the testes.1

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms scrotal or cutaneous, pain or ulceration, and HIPEC or hyperthermic in

Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy involves installation of high-concentration chemotherapeutics into the peritoneal cavity at the conclusion of surgical cytoreductive therapy. Cell cycle–nonspecific agents such as MitC commonly are used for this procedure.4 It is classified as a vesicant, which is the designation given to drugs known to produce the most severe extravasation reactions of skin ulceration and necrosis.5,6 Symptoms typically include an early area of localized edema, erythema, and severe pain that progresses to superficial soft tissue and skin necrosis.7 Unfortunately, no well-studied antidote exists for MitC, though empirical guidelines suggest therapeutic management with DMSO and ice packs.6,8

Dimethyl sulfoxide is thought to work as a free radical scavenger as well as a solvent that facilitates diffusion of chemotherapeutics through tissues and thus down a concentration gradient, ideal in the circumstance of an extravasation reaction.8 Topical DMSO has been studied as a nonsurgical treatment in a small number of patients to prevent progression to necrosis following MitC extravasation.5,7 However, these cases only report extravasation reactions from IV infiltration.5,7,9 Dimethyl sulfoxide is rapidly absorbed and acts as a theoretical carrier for MitC as well as other topical substances.5,10,11 Caution is advised when using topical lidocaine or steroids in combination with DMSO, as they will be rapidly absorbed systemically. Patients also should be informed about a mild local burning sensation after DMSO application and a garliclike odor of the breath, which have occurred in 5.5% and 27.5% of patients, respectively (N=144).5 Dimethyl sulfoxide has no known toxic side effects but can cause erythema, pruritus, and very rarely allergic contact dermatitis.5,12 Abdul Aziz et al2 postulated that DMSO might be used as a method to prevent the progression of necrosis in symptomatic patients following HIPEC with MitC. Reports of its use on the scrotum are absent in the current available literature.

Treatment with DMSO was attempted in our patient with limited success secondary to delayed recognition and lack of supporting literature for DMSO treatment of scrotal necrosis. Treatment was delayed by 11 days after the onset of symptoms, which is far beyond the recommendation of starting within 10 minutes.8 Irreversible tissue necrosis had already occurred as evidenced by the presence of eschar. However, it seems apparent that DMSO provided some benefit given the clear improvement in erythema and pain 7 hours after application (Figure 2). It is unknown to what extent the necrosis would have progressed if not treated with DMSO.

Scrotal necrosis following HIPEC with MitC is a rare and incompletely understood but important chemotherapy reaction. The presentation is fairly specific with the presence of intractable and constant scrotal pain along with erythema and induration progressing to eschar. Although DMSO has been found to be effective for certain vesicant extravasation reactions at IV sites, it is not well studied for MitC, and no reports exist regarding its use on the scrotum. The presented characterization and explanation of the pathophysiology of this entity will aid in early recognition and timely institution of topical mitigating agents such as DMSO, which may prevent progression to scrotal necrosis and need for surgical debridement. More effective strategies may be geared toward prevention with thorough washout following HIPEC, preprocedural radiologic imaging or intraoperative visualization of the patent processus vaginalis, internal inguinal canal plugs, and patient education with anticipatory guidance should a reaction occur.2

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

- Akhavan A, Yin M, Benoit R. Scrotal ulcer after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy. Urology. 2007;69:778.E9-E10.

- Abdul Aziz NH, Wang W, Teo MC. Scrotal pain and ulceration post HIPEC: a case report. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:60-63.

- Silva F, Avancini J, Criado P, et al. Scrotum ulcer developed after intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy with mitomycin-C [published October 21, 2012]. Bjui International. doi:10.1002/BJUIw-2012-019-web.

- González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G.Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;15:68-75.

- Bertelli G, Gozza A, Forno GB, et al. Topical dimethyl sulfoxide for the prevention of soft tissue injury after extravasation of vesicant cytotoxic drugs: a prospective clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2851-2855.

- Bertelli G. Prevention and management of extravasation of cytotoxic drugs. Drug Saf. 1995;12:245-255.

- Alberts DS, Dorr RT. Case report: topical DMSO for mitomycin-C-induced skin ulceration. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1991;18:693-695.

- Pérez Fidalgo JA, García Fabregat L, Cervantes A, et al; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Management of chemotherapy extravasation: ESMO-EONS Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(suppl 5):167-173.

- Ludwig CU, Stoll HR, Obrist R, et al. Prevention of cytotoxic drug induced skin ulcers with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and alpha-tocopherole. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1987;23:327-329.

- Groel JT. Dimethyl sulfoxide as a vehicle for corticosteroids. a comparison with the occlusive dressing technique. Arch Dermatol. 1968;97:110-114.

- Simon LS, Grierson LM, Naseer Z. Efficacy and safety of topical diclofenac containing dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) compared with those of topical placebo, DMSO vehicle and oral diclofenac for knee osteoarthritis [published online April 19, 2009]. Pain. 2009;143:238-245.

- Nishimura M, Takano Y, Toshitani S. Systemic contact dermatitis medicamentosa occurring after intravesical dimethyl sulfoxide treatment for interstitial cystitis. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:182-183.

Practice Points

- Scrotal ulceration following hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy has been reported only a few times in the literature and is likely underreported. The presentation in all reported cases was similar, with a delay in symptom onset of weeks to months, involvement of the anterior scrotum, and pain.

- Dimethyl sulfoxide, used in other vesicant reactions, may have a role in mitigating tissue damage. Alternatively, methods to prevent sequestration of vesicants in the potential space of the tunica vaginalis layers can be employed.

Ill-Defined Macule on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Microvenular Hemangioma

Microvenular hemangioma is an acquired benign vascular neoplasm that was described by Hunt et al1 in 1991, though Bantel et al2 reported a similar entity termed micropapillary angioma in 1989. Microvenular hemangioma typically presents as a solitary, slowly enlarging, red to violaceous, asymptomatic papule, plaque, or nodule measuring 5 to 20 mm in diameter. It usually is located on the trunk, arms, or legs of young adults without any gender predilection. Microvenular hemangioma is rare.3 The etiology has not been elucidated, though a relationship with hormonal factors such as pregnancy or hormonal contraceptives has been described.2

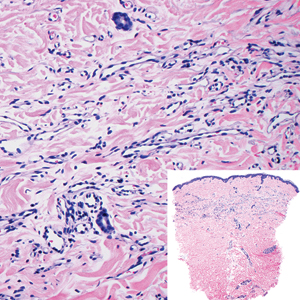

Histopathologically, microvenular hemangioma has a characteristic morphology. It is comprised of a well-circumscribed collection of thin-walled blood vessels with narrow lumens (quiz image).4 The blood vessels tend to infiltrate the superficial and deep dermis and are surrounded by a collagenous or desmoplastic stroma. The endothelial cells are normal in size without atypia, mitotic figures, or pleomorphism. A mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate sometimes is present. Microvenular hemangioma expresses many vascular markers confirming its endothelial origin, including CD34, CD31, WT1, factor VIII-related antigen, and von Willebrand factor.3 Moreover, WT1 staining suggests the lesion is a vascular proliferative growth, as it usually is negative in vascular malformations due to errors of endothelial development.5 In addition, it lacks expression of podoplanin (D2-40), which also supports a vascular as opposed to a lymphatic origin.4

Cutaneous angiosarcoma is a rare and highly aggressive malignant neoplasm of the vascular endothelium with a predilection for the skin and superficial soft tissue. Clinical presentation is variable, as it can arise sporadically, commonly on the scalp and face of elderly patients, in areas of chronic radiation therapy, or in association with chronic lymphedema (Stewart-Treves syndrome).6 Sporadic neoplasms appear clinically as purpuric macules, plaques, or nodules and are more common in elderly men than women. They are aggressive tumors that tend to recur and metastasize despite aggressive therapy and therefore carry a poor prognosis.7 Histopathologically, well-differentiated tumors are characterized by irregular dissecting vessels lined with crowded inconspicuous endothelial cells (Figure 1). Cutaneous angiosarcoma is poorly circumscribed with marked cytologic atypia, and the vessels can take on a sinusoidal growth pattern.8

Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a virally induced lymphoangioproliferative disease, with human herpesvirus 8 as the implicated agent. There are 4 principal clinical variants of KS: epidemic or AIDS-associated KS, endemic or African KS, KS due to iatrogenic immunosuppression, and Mediterranean or classic KS.9 Cutaneous lesions vary from pink patches to dark purple plaques or nodules that commonly occur on the lower legs10; however, the clinical appearance of KS varies depending on the clinical variant and stage. Histopathologically, early lesions of KS exhibit a superficial dermal proliferation of small angulated and jagged vessels that tend to separate into collagen bundles and are surrounded by a lymphoplasmacytic perivascular infiltrate. These native vascular structures often are surrounded by more ectatic neoplastic channels with plump endothelial cells, known as the promontory sign (Figure 2).11 With more advanced lesions, the proliferation of slitlike vessels becomes more cellular and extends deeper into the dermis and subcutis. Although the histopathologic features vary with the stage of the lesion, they do not notably vary between clinical subtypes.

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma, also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a small, benign, vascular tumor that usually affects the trunk, arms, and legs in young to middle-aged adults without a gender predilection. Clinically, it appears as a small, solitary, red to purple papule or macule that typically is surrounded by a pale thin area and a peripheral ecchymotic ring, creating a targetoid appearance, thus the term targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma.12 Histopathologically, there is a prominent dermal vascular proliferation. In the papillary dermis, there are dilated superficial vessels lined with a single layer of endothelial cells characterized by a plump, hobnail-like appearance that protrude into the lumen (Figure 3). In the deeper dermis, the vascular spaces are angulated and slitlike and appear to dissect through collagen bundles. Hemosiderin, thrombi, extravasated erythrocytes, and a lymphocytic infiltrate also are often seen.13

Tufted angioma is a rare benign vascular lesion that usually presents as an acquired lesion in children and young adults, though it may be congenital. It is commonly localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Clinically, the lesions appear as red to purple patches and plaques that typically are located on the neck or trunk. More than 50% of cases present during the first year of life and slowly spread to involve large areas before stabilizing in size.14 Partial spontaneous regression may occur, but complete regression is rare.15 Lesions usually are asymptomatic but may be painful during periods of platelet trapping (Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon), which may develop in congenital cases. Tufted angioma is named for its characteristic histopathologic appearance, which consists of multiple discrete lobules or tufts of tightly packed capillaries in a cannonball-like appearance throughout the dermis and subcutis (Figure 4).14,15

- Hunt SJ, Santa Cruz DJ, Barr RJ. Microvenular hemangioma. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:235-240.

- Bantel E, Grosshans E, Ortonne JP. Understanding microcapillary angioma, observations in pregnant patients and in females treated with hormonal contraceptives [in German]. Z Hautkr. 1989;64:1071-1074.

- Mansur AT, Demirci GT, Ozbal Koc E, et al. An unusual lesion on the nose: microvenular hemangioma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2018;8:7-11.

- Napekoski KM, Fernandez AP, Billings SD. Microvenular hemangioma: a clinicopathologic review of 13 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:816-822.

- Trinidade F, Tellechea O, Torrelo A, et al. Wilms tumor 1 expression in vascular neoplasms and vascular malformations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:569-572.