User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Multiple Subcutaneous Dermoid Cysts

To the Editor:

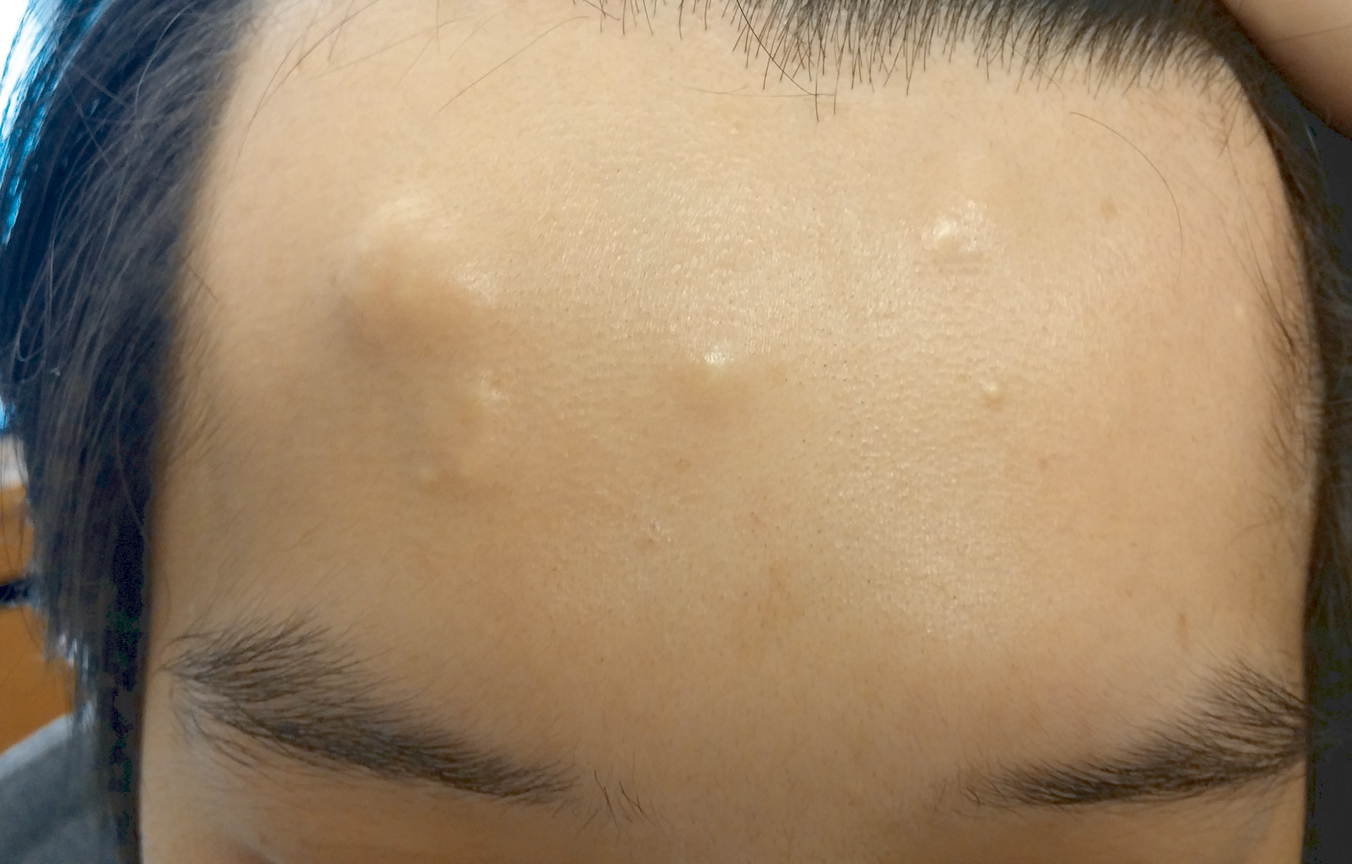

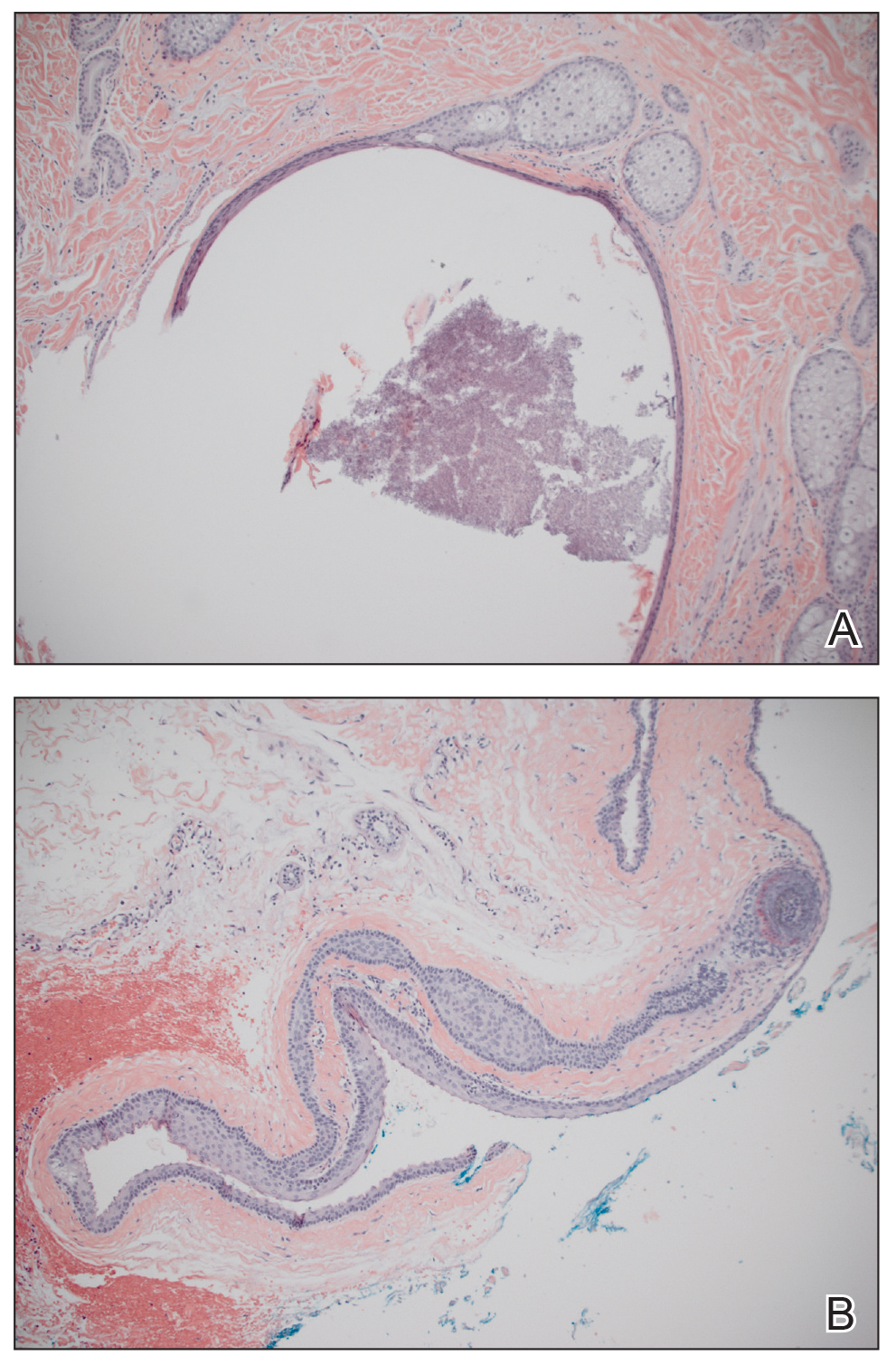

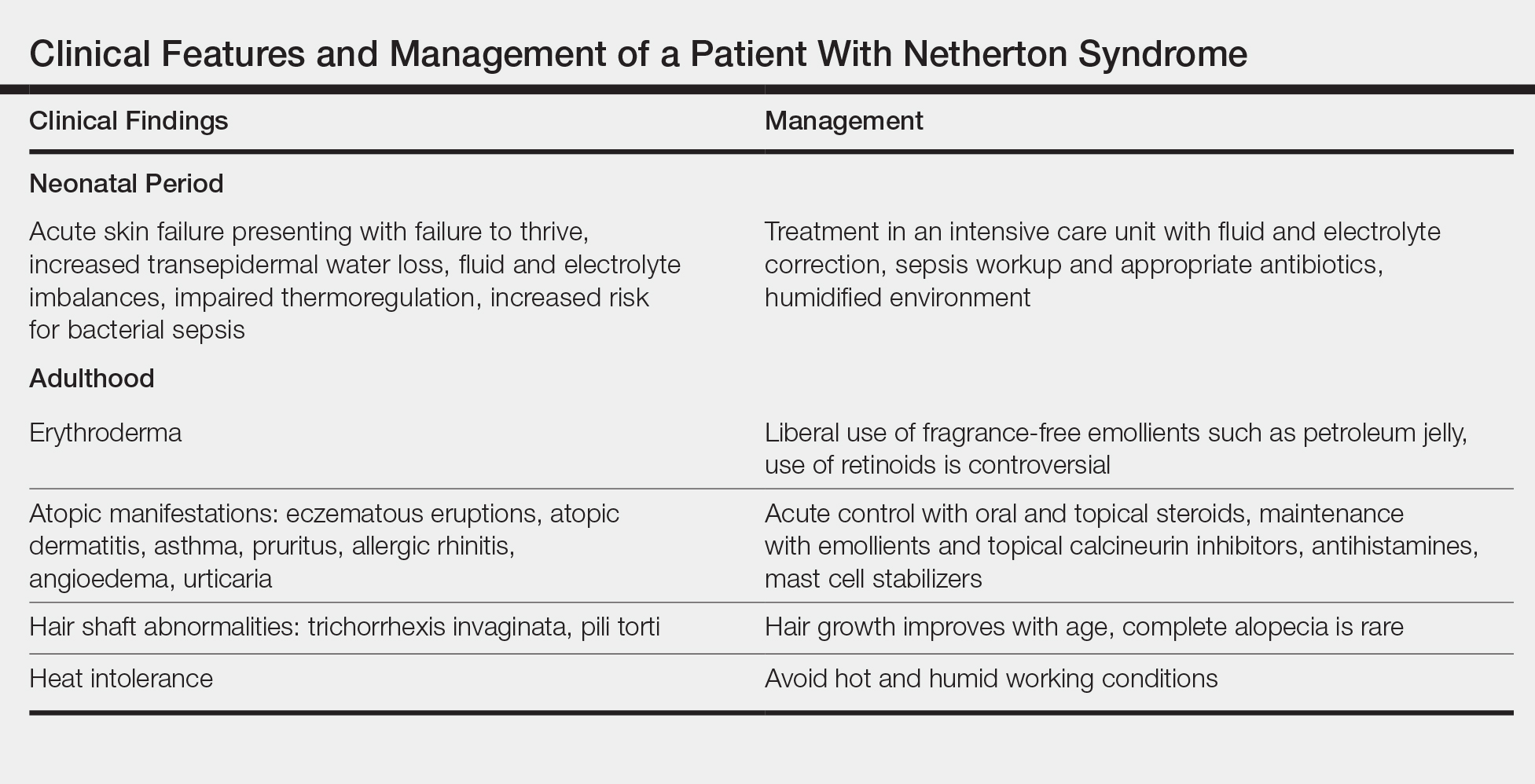

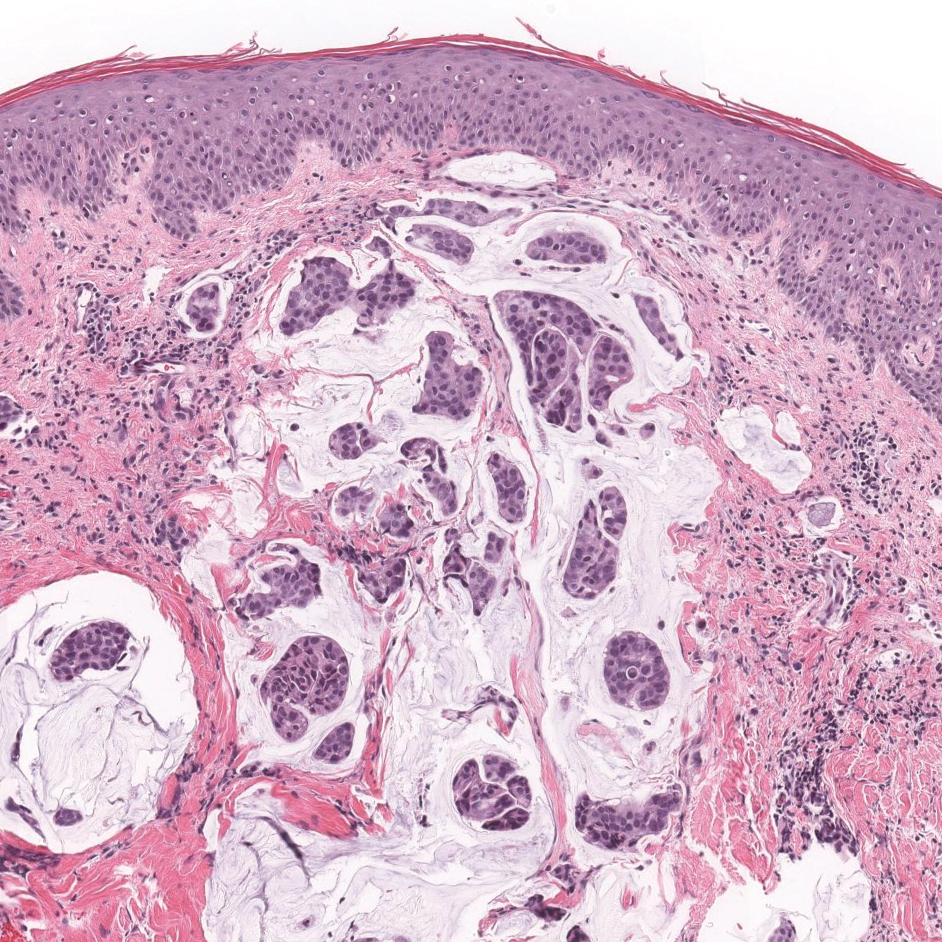

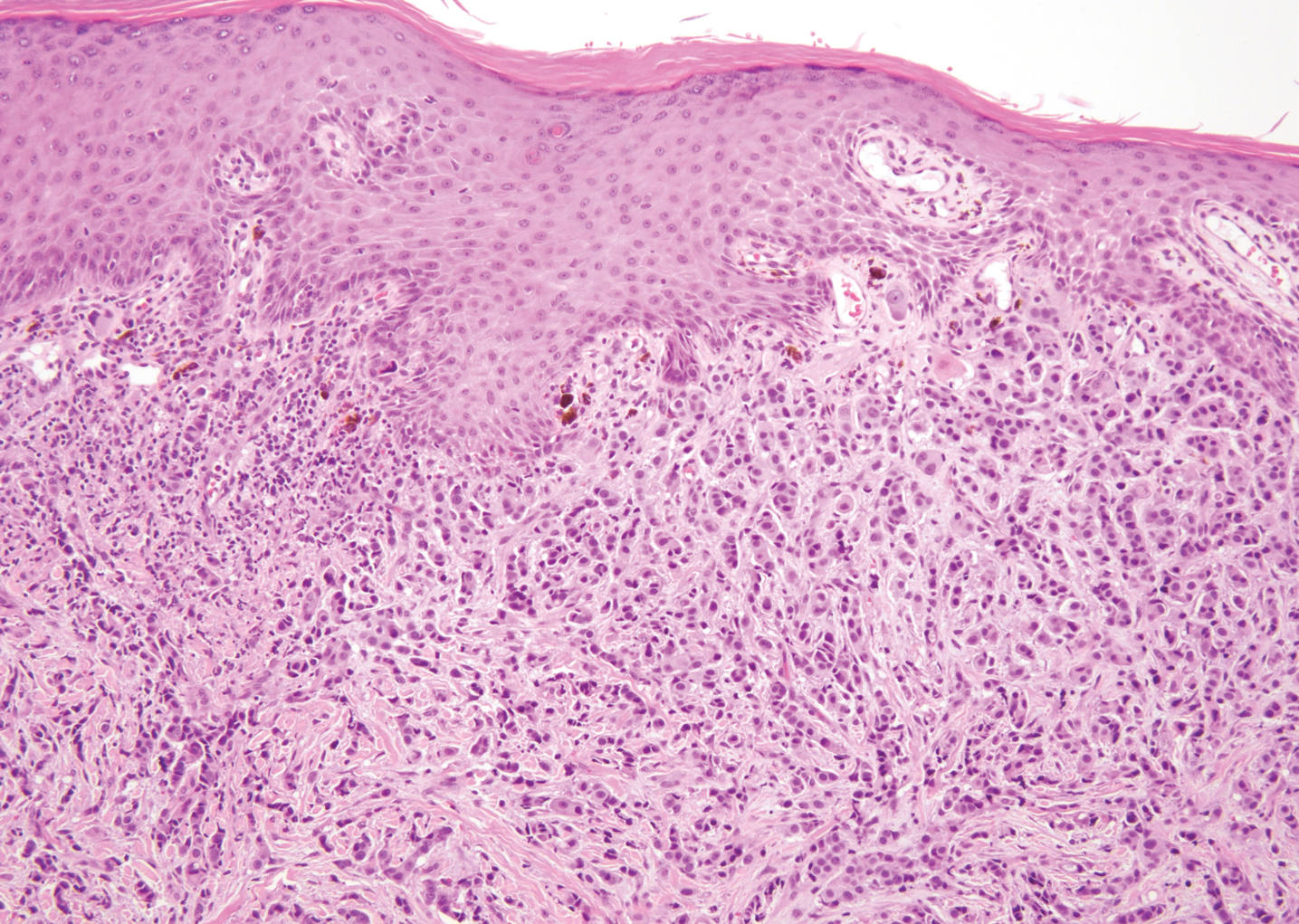

A 30-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with multiple subcutaneous nodules on the forehead of 5 years’ duration. He reported no history of forehead trauma or manipulation of the lesions, and there was no accompanying pruritis, pain, erythema, or purulent discharge. There was no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors. On physical examination, the patient had 5 firm, flesh-colored to yellow nodules measuring approximately 0.2 to 1.5 cm in diameter without central punctae scattered over the central forehead (Figure 1). Due to cosmetic concerns, the patient elected to pursue surgical excision of the lesions, which occurred over several office visits. During surgical excision, the lesions were found to be smooth, encapsulated, and mobile, and they were excised without surgical complication. Histopathologic examination showed subcutaneous cysts lined by squamous epithelium with associated sebaceous glands (Figure 2A) and hair follicles in the cyst lumen (Figure 2B). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of multiple subcutaneous dermoid cysts.

Dermoid cysts are relatively uncommon, benign tumors consisting of tissue derived from ectodermal and mesodermal germ cell layers. Dermoid cysts may be distinguished from teratomas, which may contain tissues derived from all 3 germ cell layers and typically consist of types of tissues foreign to the site of origin, such as dental, thyroid, gastrointestinal, or neural tissue.1,2 The majority of dermoid cysts are congenitally developed along the lines of embryologic fusion due to an error in the division of the ectoderm and mesoderm3,4; however, some dermoid cysts may be acquired from epidermal elements being traumatically implanted into the dermis.5

Our patient’s presentation with multiple dermoid cysts was atypical, as dermoid cysts are almost always solitary tumors. A similar case was reported in a 41-year-old man who developed multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead over a 20-year period.This patient also was otherwise healthy, denied prior trauma to the forehead, and reported no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors.5

Another unusual feature in our case was the location of the dermoid cysts on the central forehead. The most common location for dermoid cysts is the lateral third of the eyebrows (47%–70% of cases).1,4,6-10 These cysts occur because of sequestration of the surface ectoderm during fusion along the naso-optic groove.2 Dermoid cysts also have been noted in other anatomical areas such as the scalp, nose, anterior neck, and trunk.6

Dermoid cysts tend to be small, round, smooth, and slowly growing until sudden enlargement prompts surgical evaluation.4,6 During surgical excision, they often are fixed to the underlying bone but also may be freely mobile, as in our patient.6 Histopathologic examination reveals a stratified squamous epithelium with associated adnexal structures such as sebaceous glands or hair follicles.1 Smooth muscle fibers, prominent vascular stroma, small nerves, and collagen and elastic fibers also may be found within the lumen of dermoid cysts.2

In some cases, dermoid cysts may be invasive and carry the risk of bony erosion, intracranial extension, osteomyelitis, meningitis, or cerebral abscess. Imaging studies sometimes are needed to rule out intracranial or intraspinal extension, particularly for midline dermoid cysts.6 The standard of treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical excision and complete enucleation without disruption of the cyst wall; however, invasive dermoid cysts may require endoscopic excision, orbitotomy, or craniotomy.4,6

- Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Subcutaneous dermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:237-239.

- Smirniotopoulos JG, Chiechi MV. Teratomas, dermoids, and epidermoids of the head and neck. Radiographics. 1995;15:1437-1455.

- Pryor SG, Lewis JE, Weaver AL, et al. Pediatric dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:938-942.

- Yamaki T, Higuchi R, Sasaki K, et al. Multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead. case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30:321-324.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Al-Khateeb TH, Al-Masri NM, Al-Zoubi F. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:52-57.

- McAvoy JM, Zuckerbraun L. Dermoid cysts of the head and neck in children. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:529-531.

- Taylor BW, Erich JB, Dockerty MB. Dermoids of the head and neck. Minnesota Med. 1966;49:1535-1540.

- Golden BA, Zide MF. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1613-1619.

To the Editor:

A 30-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with multiple subcutaneous nodules on the forehead of 5 years’ duration. He reported no history of forehead trauma or manipulation of the lesions, and there was no accompanying pruritis, pain, erythema, or purulent discharge. There was no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors. On physical examination, the patient had 5 firm, flesh-colored to yellow nodules measuring approximately 0.2 to 1.5 cm in diameter without central punctae scattered over the central forehead (Figure 1). Due to cosmetic concerns, the patient elected to pursue surgical excision of the lesions, which occurred over several office visits. During surgical excision, the lesions were found to be smooth, encapsulated, and mobile, and they were excised without surgical complication. Histopathologic examination showed subcutaneous cysts lined by squamous epithelium with associated sebaceous glands (Figure 2A) and hair follicles in the cyst lumen (Figure 2B). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of multiple subcutaneous dermoid cysts.

Dermoid cysts are relatively uncommon, benign tumors consisting of tissue derived from ectodermal and mesodermal germ cell layers. Dermoid cysts may be distinguished from teratomas, which may contain tissues derived from all 3 germ cell layers and typically consist of types of tissues foreign to the site of origin, such as dental, thyroid, gastrointestinal, or neural tissue.1,2 The majority of dermoid cysts are congenitally developed along the lines of embryologic fusion due to an error in the division of the ectoderm and mesoderm3,4; however, some dermoid cysts may be acquired from epidermal elements being traumatically implanted into the dermis.5

Our patient’s presentation with multiple dermoid cysts was atypical, as dermoid cysts are almost always solitary tumors. A similar case was reported in a 41-year-old man who developed multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead over a 20-year period.This patient also was otherwise healthy, denied prior trauma to the forehead, and reported no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors.5

Another unusual feature in our case was the location of the dermoid cysts on the central forehead. The most common location for dermoid cysts is the lateral third of the eyebrows (47%–70% of cases).1,4,6-10 These cysts occur because of sequestration of the surface ectoderm during fusion along the naso-optic groove.2 Dermoid cysts also have been noted in other anatomical areas such as the scalp, nose, anterior neck, and trunk.6

Dermoid cysts tend to be small, round, smooth, and slowly growing until sudden enlargement prompts surgical evaluation.4,6 During surgical excision, they often are fixed to the underlying bone but also may be freely mobile, as in our patient.6 Histopathologic examination reveals a stratified squamous epithelium with associated adnexal structures such as sebaceous glands or hair follicles.1 Smooth muscle fibers, prominent vascular stroma, small nerves, and collagen and elastic fibers also may be found within the lumen of dermoid cysts.2

In some cases, dermoid cysts may be invasive and carry the risk of bony erosion, intracranial extension, osteomyelitis, meningitis, or cerebral abscess. Imaging studies sometimes are needed to rule out intracranial or intraspinal extension, particularly for midline dermoid cysts.6 The standard of treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical excision and complete enucleation without disruption of the cyst wall; however, invasive dermoid cysts may require endoscopic excision, orbitotomy, or craniotomy.4,6

To the Editor:

A 30-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with multiple subcutaneous nodules on the forehead of 5 years’ duration. He reported no history of forehead trauma or manipulation of the lesions, and there was no accompanying pruritis, pain, erythema, or purulent discharge. There was no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors. On physical examination, the patient had 5 firm, flesh-colored to yellow nodules measuring approximately 0.2 to 1.5 cm in diameter without central punctae scattered over the central forehead (Figure 1). Due to cosmetic concerns, the patient elected to pursue surgical excision of the lesions, which occurred over several office visits. During surgical excision, the lesions were found to be smooth, encapsulated, and mobile, and they were excised without surgical complication. Histopathologic examination showed subcutaneous cysts lined by squamous epithelium with associated sebaceous glands (Figure 2A) and hair follicles in the cyst lumen (Figure 2B). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of multiple subcutaneous dermoid cysts.

Dermoid cysts are relatively uncommon, benign tumors consisting of tissue derived from ectodermal and mesodermal germ cell layers. Dermoid cysts may be distinguished from teratomas, which may contain tissues derived from all 3 germ cell layers and typically consist of types of tissues foreign to the site of origin, such as dental, thyroid, gastrointestinal, or neural tissue.1,2 The majority of dermoid cysts are congenitally developed along the lines of embryologic fusion due to an error in the division of the ectoderm and mesoderm3,4; however, some dermoid cysts may be acquired from epidermal elements being traumatically implanted into the dermis.5

Our patient’s presentation with multiple dermoid cysts was atypical, as dermoid cysts are almost always solitary tumors. A similar case was reported in a 41-year-old man who developed multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead over a 20-year period.This patient also was otherwise healthy, denied prior trauma to the forehead, and reported no family history of skin or gastrointestinal tract tumors.5

Another unusual feature in our case was the location of the dermoid cysts on the central forehead. The most common location for dermoid cysts is the lateral third of the eyebrows (47%–70% of cases).1,4,6-10 These cysts occur because of sequestration of the surface ectoderm during fusion along the naso-optic groove.2 Dermoid cysts also have been noted in other anatomical areas such as the scalp, nose, anterior neck, and trunk.6

Dermoid cysts tend to be small, round, smooth, and slowly growing until sudden enlargement prompts surgical evaluation.4,6 During surgical excision, they often are fixed to the underlying bone but also may be freely mobile, as in our patient.6 Histopathologic examination reveals a stratified squamous epithelium with associated adnexal structures such as sebaceous glands or hair follicles.1 Smooth muscle fibers, prominent vascular stroma, small nerves, and collagen and elastic fibers also may be found within the lumen of dermoid cysts.2

In some cases, dermoid cysts may be invasive and carry the risk of bony erosion, intracranial extension, osteomyelitis, meningitis, or cerebral abscess. Imaging studies sometimes are needed to rule out intracranial or intraspinal extension, particularly for midline dermoid cysts.6 The standard of treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical excision and complete enucleation without disruption of the cyst wall; however, invasive dermoid cysts may require endoscopic excision, orbitotomy, or craniotomy.4,6

- Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Subcutaneous dermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:237-239.

- Smirniotopoulos JG, Chiechi MV. Teratomas, dermoids, and epidermoids of the head and neck. Radiographics. 1995;15:1437-1455.

- Pryor SG, Lewis JE, Weaver AL, et al. Pediatric dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:938-942.

- Yamaki T, Higuchi R, Sasaki K, et al. Multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead. case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30:321-324.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Al-Khateeb TH, Al-Masri NM, Al-Zoubi F. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:52-57.

- McAvoy JM, Zuckerbraun L. Dermoid cysts of the head and neck in children. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:529-531.

- Taylor BW, Erich JB, Dockerty MB. Dermoids of the head and neck. Minnesota Med. 1966;49:1535-1540.

- Golden BA, Zide MF. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1613-1619.

- Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Subcutaneous dermoid cysts. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:237-239.

- Smirniotopoulos JG, Chiechi MV. Teratomas, dermoids, and epidermoids of the head and neck. Radiographics. 1995;15:1437-1455.

- Pryor SG, Lewis JE, Weaver AL, et al. Pediatric dermoid cysts of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:938-942.

- Yamaki T, Higuchi R, Sasaki K, et al. Multiple dermoid cysts on the forehead. case report. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1996;30:321-324.

- Prior A, Anania P, Pacetti M, et al. Dermoid and epidermoid cysts of scalp: case series of 234 consecutive patients. World Neurosurg. 2018;120:119-124.

- Orozco-Covarrubias L, Lara-Carpio R, Saez-De-Ocariz M, et al. Dermoid cysts: a report of 75 pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:706-711.

- Al-Khateeb TH, Al-Masri NM, Al-Zoubi F. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:52-57.

- McAvoy JM, Zuckerbraun L. Dermoid cysts of the head and neck in children. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:529-531.

- Taylor BW, Erich JB, Dockerty MB. Dermoids of the head and neck. Minnesota Med. 1966;49:1535-1540.

- Golden BA, Zide MF. Cutaneous cysts of the head and neck. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1613-1619.

Practice Points

- The majority of dermoid cysts are congenital; however, they may be acquired from traumatic implantation of epidermal elements into the dermis.

- The most common location for dermoid cysts is the lateral third of the eyebrows; however, they also may occur on the mid forehead, scalp, nose, anterior neck, and trunk.

- Imaging studies may be needed to rule out intracranial or intraspinal extension of dermoid cysts, particularly for those presenting in the midline.

Violaceous Nodules on the Hard Palate

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

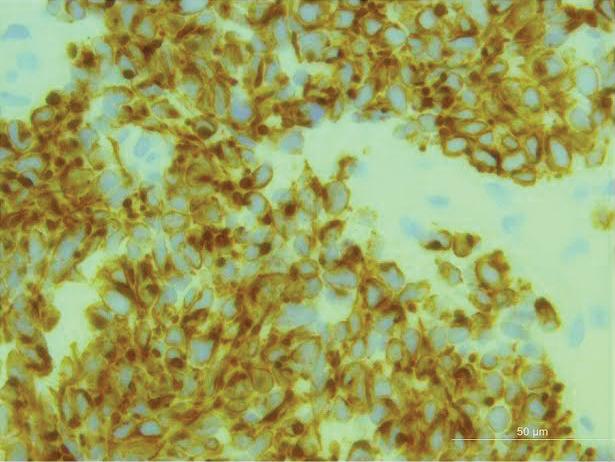

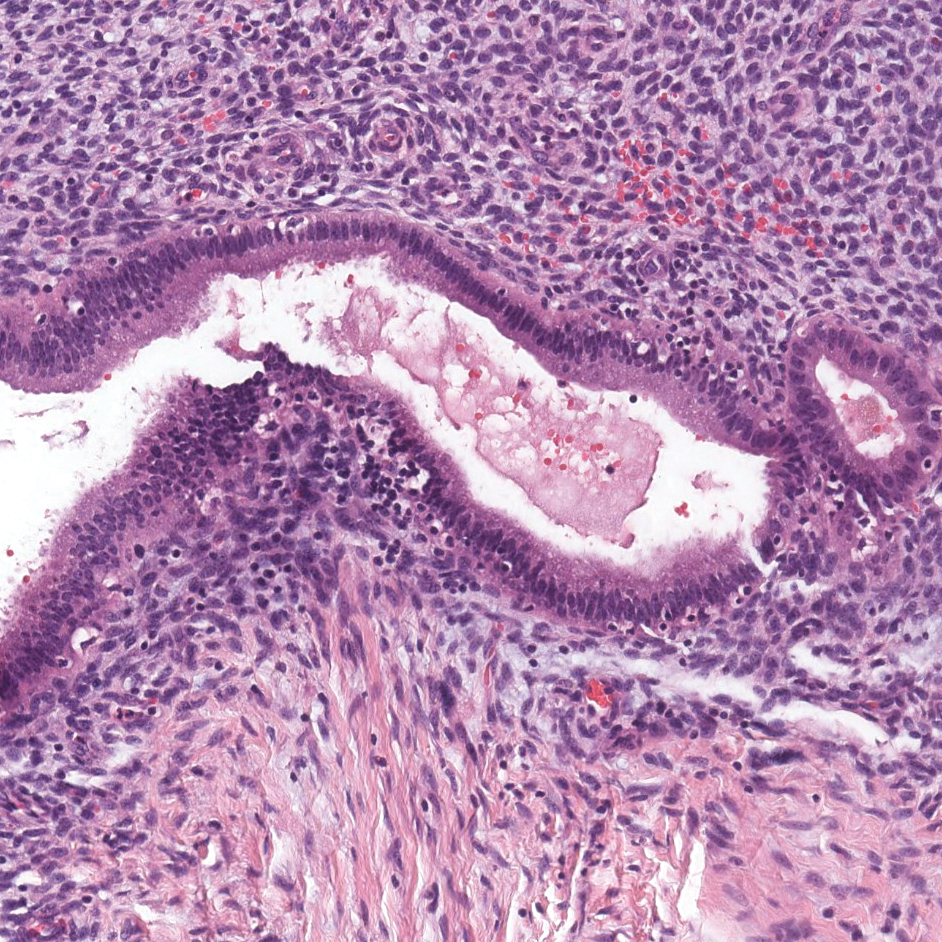

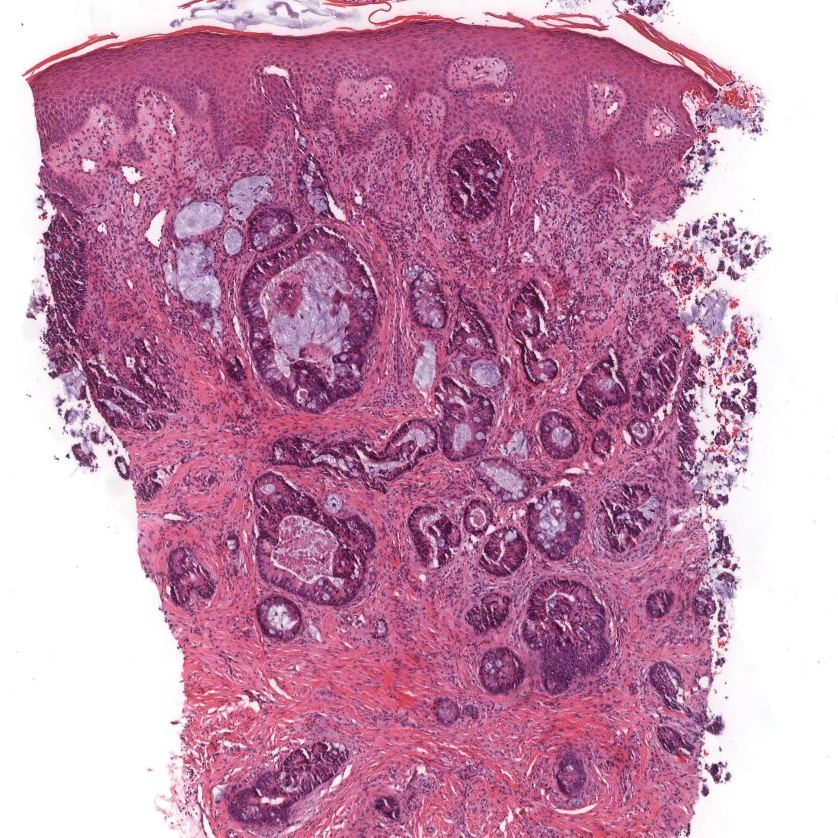

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A 4-mm punch biopsy from the border of an ulcerated nodular lesion on the hard palate demonstrated diffusely distributed spindle cells, cleftlike microvascularity with extravasated erythrocytes, and widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity on histopathology (Figure 1). Serologic tests were positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; HIV RNA was 14,584 IU/mL and the CD4 count was 254/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) and referred to the infectious disease department for initiation of antiviral therapy. Marked regression was detected after 6 months of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) without any additional treatment (Figure 2).

widespread human herpesvirus 8 immunoreactivity (H&E, original magnification ×4).

Kaposi sarcoma is a human herpesvirus 8-associated angioproliferative disorder with low-grade malignant potential. There are 4 well-known clinical types: classic, endemic, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated.1 Involvement of the oral cavity may be seen in all types but mostly is associated with the AIDS-associated type, which also could be a signal for undiagnosed asymptomatic HIV infection.2 Oral KS most often affects the hard and soft palate, gingiva, and dorsal tongue, with plaques or tumors ranging from nonpigmented to brownish red or violaceous. AIDS-associated KS is known to be related to cytokine expression, which is induced by HIV infection causing immune dysregulation by altering the expression of cytokines, including IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.1 An in vitro study showed that cytokines secrete a number of angiogenic growth factors that, along with HIV proteins, induce and proliferate cells to become sarcoma cells. Integrins and the apoptosis process also are important in proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) is a rare manifestation of infection caused by Bartonella species, which leads to vasoproliferative lesions of the skin and other organs. Bacillary angiomatosis affects individuals with advanced HIV or other immunocompromised individuals and may clinically mimic KS, which is similarly characterized by red-purple papules, nodules, or plaques. Differentiating BA from KS largely depends on histopathologic examination, with BA demonstrating protuberant endothelial cells surrounded by clumps of bacilli that are visible on Warthin-Starry silver stain.

Lymphangioma is a benign hamartomatous hyperplasia of the lymphatic vessels. The majority of lymphangiomas are superficial, but a few may extend deeply into the connective tissue. Intraoral lymphangiomas occur more frequently on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. They may be differentiated with their soft quality, pebblelike surface, and translucent vesicles.

Malignant tumors of the oral cavity are rare, representing only 5% of tumors occurring in the body.4 Among malignant tumors of the oral cavity, squamous cell carcinomas are the most frequent type (90%-98%), and lymphomas and melanoma are the most outstanding among the remaining 2% to 10%. Both for lymphoma and mucosal melanoma, the most common sites of involvement are the soft tissues of the oral cavity, palatal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, cheeks, floor of the mouth, and lips.4 Although mucosal melanoma lesions usually are characterized by pigmented and ulcerated lesions, amelanotic variants also should be kept in mind. Histopathologic examination is mandatory for diagnosis.

Intralesional chemotherapy with vinblastine or bleomycin, radiotherapy, electrochemotherapy, systemic antiretroviral therapy (ie, HAART), and chemotherapy with daunorubicin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin are the main treatment options.5,6 The immune system activator role of HAART leads to an increased CD4 count and reduces HIV proteins, which helps induction of the proliferation and neovascularization of KS tumor cells.3 This effect may help resolution of KS with localized involvement and allows physicians to utilize HAART without any other additional local and systemic chemotherapy treatment.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

- Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Oral Kaposi's sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:666-672.

- Martorano LM, Cannella JD, Lloyd JR. Mucocutaneous presentation of Kaposi sarcoma in an asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-positive man. Cutis. 2015;95:E19-E22.

- Stebbing J, Portsmouth S, Gazzard B. How does HAART lead to the resolution of Kaposi's sarcoma? J Antimicrobial Chemother. 2003;51:1095-1098.

- Guevara-Canales JO, Morales-Vadillo R, Sacsaquispe-Contreras SJ, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the oral cavity and the maxillofacial region: overall survivalprognostic factors. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2013;18:E619-E626.

- Donato V, Guarnaccia R, Dognini J, et al. Radiation therapy in the treatment of HIV-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2153-2157.

- Gbabe OF, Okwundu CI, Dedicoat M, et al. Treatment of severe or progressive Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003256.

A 30-year-old man presented to our outpatient clinic with rapidly growing, ulcerated, violaceous lesions on the hard palate of 4 months' duration. Physical examination revealed approximately 2.0×1.5-cm, centrally ulcerated, violaceous, nodular lesions on the hard palate, as well as a 4-mm pinkish papular lesion on the soft palate.

Multiple Eruptive Syringomas on the Penis

To the Editor:

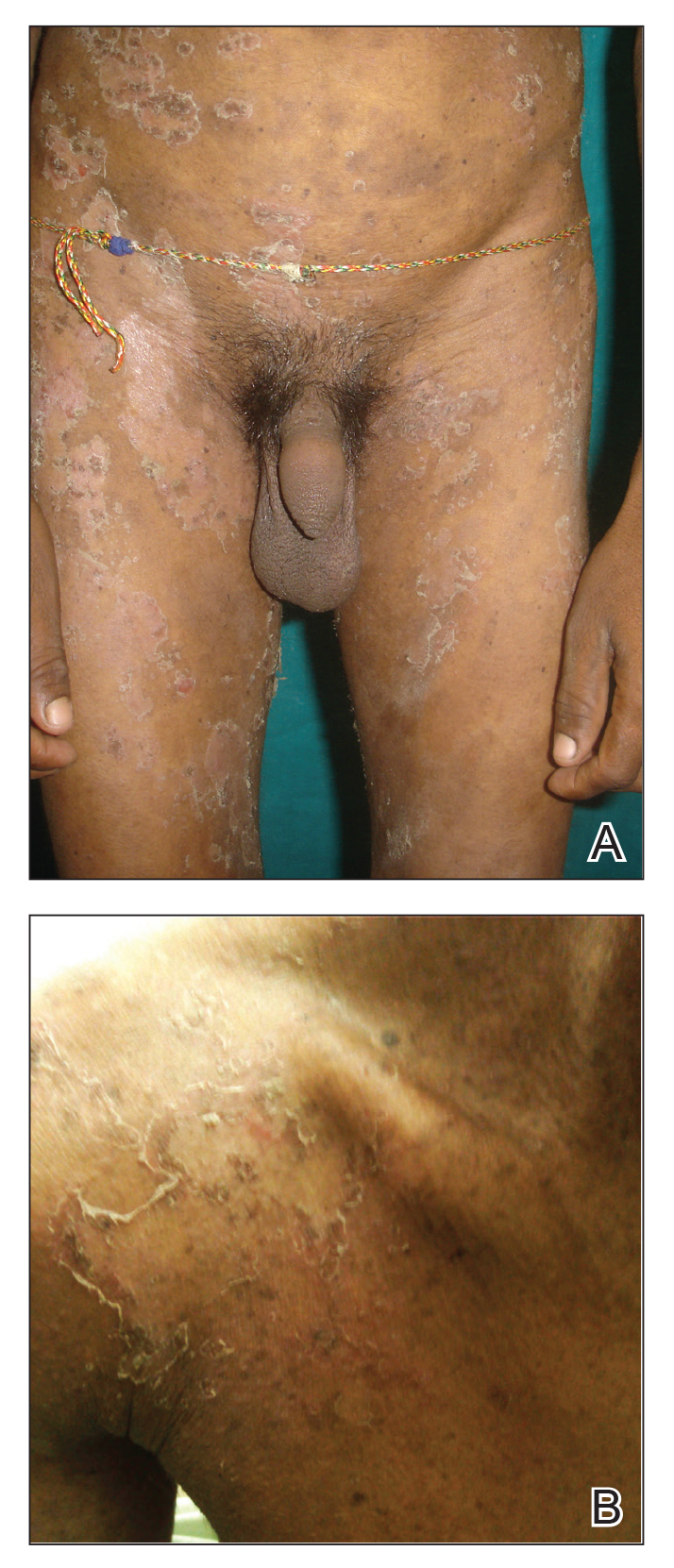

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

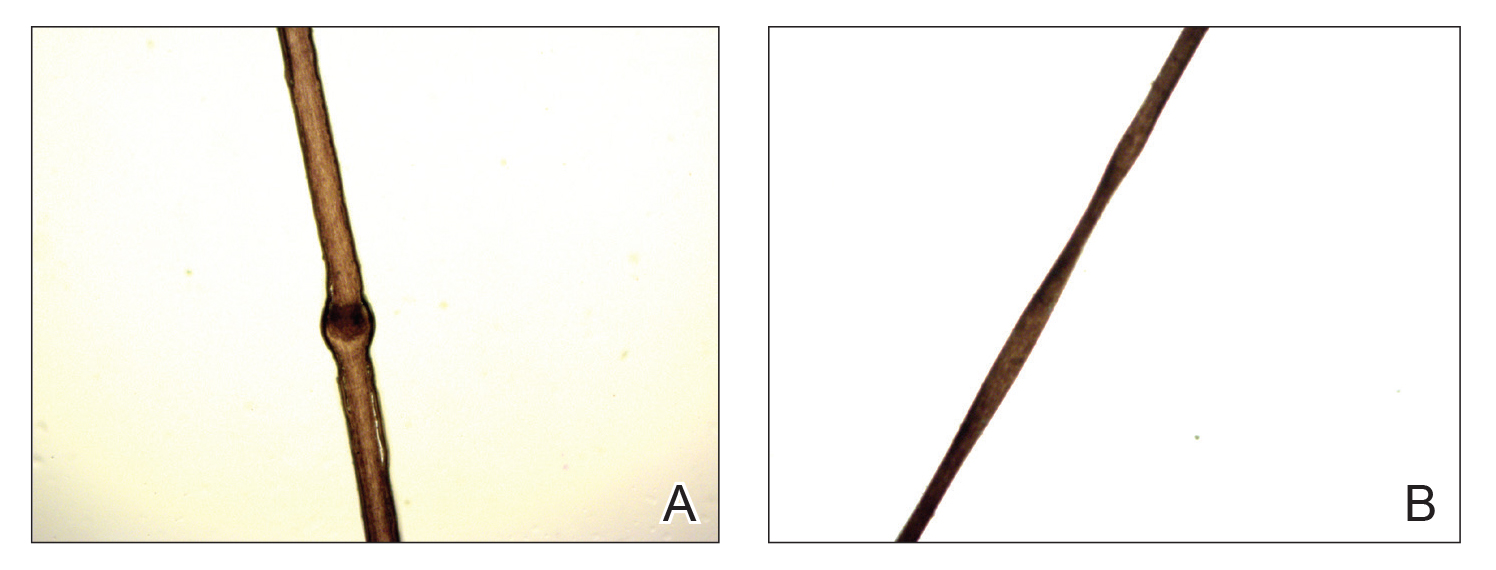

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are small, benign, asymptomatic eccrine or apocrine tumors that present as multiple discrete flesh-colored papules. They are more common in females than males.1 The etiology of eruptive syringomas is unclear, though an inflammatory process has been implicated in the abnormal proliferation of sweat glands.2 However, a minority of tumors have been known to have an autosomal-dominant mode of transmission. Multiple or eruptive syringomas are associated with Down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Blau syndrome.3 The clear cell variant has been found to be associated with diabetes mellitus.4 Syringomas most commonly appear on the lower eyelids, upper cheeks, neck, and upper chest; presentation on the penis is rare.5 We report a case of multiple eruptive syringomas located exclusively on the penis mimicking a sexually transmitted condition.

A 53-year-old man who was otherwise healthy presented with multiple flesh-colored papules on the penis that initially began to develop 30 years prior, but increased crops of lesions appeared 4 to 6 weeks prior to presentation. The patient described the lesions as rashlike, nonpruritic, and sensitive to the touch. He denied any discharge, oozing, crusting, or bleeding from the lesions. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors and stated that he was in a monogamous relationship with his wife. He had a medical history of molluscum contagiosum that was diagnosed and treated with cryotherapy 30 years prior; however, he did not have a history of any other sexually transmitted diseases. He also did not have a history of diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease.

Physical examination revealed multiple pink papules on the dorsal and ventral shaft of the penis, measuring 2 to 4 mm in diameter, with koebnerization (Figure 1). Based on clinical examination, the differential included condyloma, inflamed seborrheic keratosis, bowenoid papulosis, atypical molluscum contagiosum, or lichen planus. Consequently, a punch biopsy of the penile shaft was performed and histopathologic examination revealed proliferation of ducts focally that were tadpole shaped and embedded in a sclerotic stroma. The lining of the ducts was composed of cuboidal cells, some with clear cell change. The microscopic findings were consistent with penile syringomas (Figure 2). Laboratory results revealed the patient was negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and syphilis. The patient was given topical hydrocortisone butyrate and tacrolimus for symptomatic treatment. He declined further aggressive treatment.

Due to the rarity of syringomas on the penis, presentation of these benign eccrine tumors can be commonly mistaken for lichen planus, molluscum contagiosum, genital warts, or bowenoid papulosis.5 The characteristic histopathology of syringomas consists of multiple, small, tadpole or paisley tie–shaped ducts within an eosinophilic stroma. Often, the findings can be histologically confused with desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma. Although the histopathology of our patient’s biopsy showed clear cell change, the patient did not report a history of diabetes mellitus, which is a disease that can be associated with the clear cell variant of syringoma. Because syringomas are benign tumors, treatment is not medically necessary unless the lesions are symptomatic. Treatment often is regarded as challenging, as lesions often recur and scarring is a consideration. Possible treatments for removal of the benign papules include surgical excision, electrodesiccation and curettage, shave removal, chemical peels, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, and CO2 laser vaporization.6

To prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment, it is important to have syringomas as part of the differential diagnosis when patients present with multiple small flesh-colored papules on the penis. The lesions should be biopsied for accurate diagnosis and to provide reassurance to patients who usually come in for evaluation for fear of having acquired a sexually transmitted disease.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

- Yalisove B, Stolar EEH, Williams CM. Multiple penile papules. syringoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1391-1396.

- Cohen PR, Tschen JA, Rapini RP. Penile syringoma: reports and review of patients with syringoma located on the penis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-42.

- Yoshimi N, Kurokawa I, Kakuno A, et al. Case of generalized eruptive clear cell syringoma with diabetes mellitus. J Dermatol. 2012;39:744-745.

- Petersson F, Mjornberg PA, Kazakov DV, et al. Eruptive syringoma of the penis. a report of 2 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:436-438.

- Wu CY. Multifocal penile syringoma masquerading as genital warts. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e290-e291.

- Lipshutz RL, Kantor GR, Vonderheid EC. Multiple penile syringomas mimicking verrucae. Int J Dermatol. 1991;30:69.

Practice Points

- Penile syringoma can mimic sexually transmitted disease such as condyloma acuminatum or molluscum contagiosum.

- Penile syringomas can be long-standing and require biopsy to differentiate from other conditions.

Infographic: Hyperhidrosis Survey Results

"Doctor, Do I Need a Skin Check?"

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

What does your patient need to know at the first visit?

A patient may be scheduled for a total-body skin examination (TBSE) through several routes: primary care referral, continued cancer screening for an at-risk patient or patient transfer, or patient-directed scheduling for general screening regardless of risk factors. At the patient's first visit, it is imperative that the course of the appointment is smooth and predictable for patient comfort and for a thorough and effective examination. The nurse initially solicits salient medical history, particularly personal and family history of skin cancer, current medications, and any acute concerns. The nurse then prepares the patient for the logistics of the TBSE, namely to undress, don a gown that ties and opens in the back, and be seated on the examination table. When I enter the room, the conversation commences with me seated across from the patient, reviewing specifics about his/her history and risk factors. Then the TBSE is executed from head to toe.

Do you broadly recommend TBSE?

Firstly, TBSE is a safe clinical tool, supported by data outlining a lack of notable patient morbidity during the examination, including psychosocial factors, and it is generally well-received by patients (Risica et al). In 2016, the US Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) outlined its recommendations regarding screening for skin cancer, concluding that there is insufficient evidence to broadly recommend TBSE. Unfortunately, USPSTF findings amassed data from all types of screenings, including those by nondermatologists, and did not extract specialty-specific benefits and risks to patients. The recommendation also did not outline the influence of TBSE on morbidity and mortality for at-risk groups. The guidelines target primary care practice trends; therefore, specialty societies such as the American Academy of Dermatology issued statements following the USPSTF recommendation outlining these salient clarifications, namely that TBSE detects melanoma and keratinocyte carcinomas earlier than in patients who are not screened. Randomized controlled trials to prove this observation are lacking, particularly because of the ethics of withholding screening from a prospective study group. However, in 2017, Johnson et al outlined the best available survival data in concert with the USPSTF statement to arrive at the most beneficial screening recommendations for patients, specifically targeting risk groups--those with a history of skin cancer, immunosuppression, indoor tanning and/or many blistering sunburns, and several other genetic parameters--for at least annual TBSE.

The technique and reproducibility of TBSE also are not standardized, though they seem to have been endearingly apprenticed but variably implemented through generations of dermatology residents going forward into practice. As it is, depending on patient body surface area, mobility, willingness to disrobe, and adornments (eg, tattoos, hair appliances), multiple factors can restrict full view of a patient's skin. Recently, Helm et al proposed standardizing the TBSE sequence to minimize omitted areas of the body, which may become an imperative tool for streamlined resident teaching and optimal screening encounters.

How do you keep patients compliant with TBSE?

During and following TBSE, I typically outline any lesions of concern and plan for further testing, screening, and behavioral prevention strategies. Frequency of TBSE and importance of compliance are discussed during the visit and reinforced at checkout where the appointment templates are established a year in advance for those with skin cancer. Further, for those with melanoma, their appointment slots are given priority status so that any cancellations or delays are rescheduled preferentially. Particularly during the discussion about TBSE frequency, I emphasize the comparison and importance of this visit akin to other recommended screenings, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, and that we, as dermatologists, are part of their cancer surveillance team.

What do you do if patients refuse your recommendations?

Some patients refuse a gown or removal of certain clothing items (eg, undergarments, socks, wigs). Some patients defer a yearly TBSE upon checkout and schedule an appointment only when a lesion of concern arises. My advice is not to shame patients and to take advantage of as much as the patient is able and comfortable to show us and be present for, welcoming that we have the opportunity to take care of them and screen for cancer in any capacity. In underserved or limited budget practice regions, lesion-directed examination vs TBSE may be the only screening method utilized and may even attract more patients to a screening facility (Hoorens et al).

In the opposite corner are those patients who deem the recommended TBSE interval as too infrequent, which poses a delicate dilemma. In my opinion, these situations present another cohort of risks. Namely, the patient may become (or continue to be) overly fixated on the small details of every skin lesion, and in my experience, they tend to develop the habit of expecting at least 1 biopsy at each visit, typically of a lesion of their choosing. Depending on the validity of this expectation vs my clinical examination, it can lead to a difficult discussion with the patient about oversampling lesions and the potential for many scars, copious reexcisions for ambiguous lesion pathology, and a trend away from prudent clinical care. In addition, multiple visits incur more patient co-pays and time away from school, work, or home. To ease the patient's mind, I advise to call our office for a more acute visit if there is a lesion of concern; I additionally recommend taking a smartphone photograph of a concerning lesion and monitoring it for changes or sending the photograph to our patient portal messaging system so we can evaluate its acuity.

What take-home advice do you give to patients?

As the visit ends, I further explain that home self-examination or examination by a partner between visits is intuitively a valuable screening adjunct for skin cancer. In 2018, the USPSTF recommended behavioral skin cancer prevention counseling and self-examination only for younger-age cohorts with fair skin (6 months to 24 years), but its utility in specialty practice must be qualified. The American Academy of Dermatology Association subsequently issued a statement to support safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions, as earlier detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from these neoplasms.

Resources for Patients

American Academy of Dermatology's SPOT Skin Cancer

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: What Screening Tests Are There?

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

Suggested Readings

AAD statement on USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer screening. Schaumburg, IL: American Academy of Dermatology; July 26, 2016. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/aad-statement-on-uspstf. Accessed April 26, 2019.

AADA responds to USPSTF recommendation on skin cancer prevention counseling. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Dermatology Association; March 20, 2018. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/skin-cancer-prevention-counseling. Accessed April 26, 2019.

Helm MF, Hallock KK, Bisbee E, et al. Optimizing the total body skin exam: an observational cohort study [published online February 15, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.028.

Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, et al. Total-body examination vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:27-34.

Johnson MM, Leachman SA, Aspinwall LG, et al. Skin cancer screening: recommendations for data-driven screening guidelines and a review of the US Preventive Services Task Force controversy. Melanoma Manag. 2017;4:13-37.

Risica PM, Matthews NH, Dionne L, et al. Psychosocial consequences of skin cancer screening. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:310-316.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al. Screening for skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;316:429-435.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, et al. Behavioral counseling to prevent skin cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;319:1134-1142.

Cystic Scalp Lesion

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

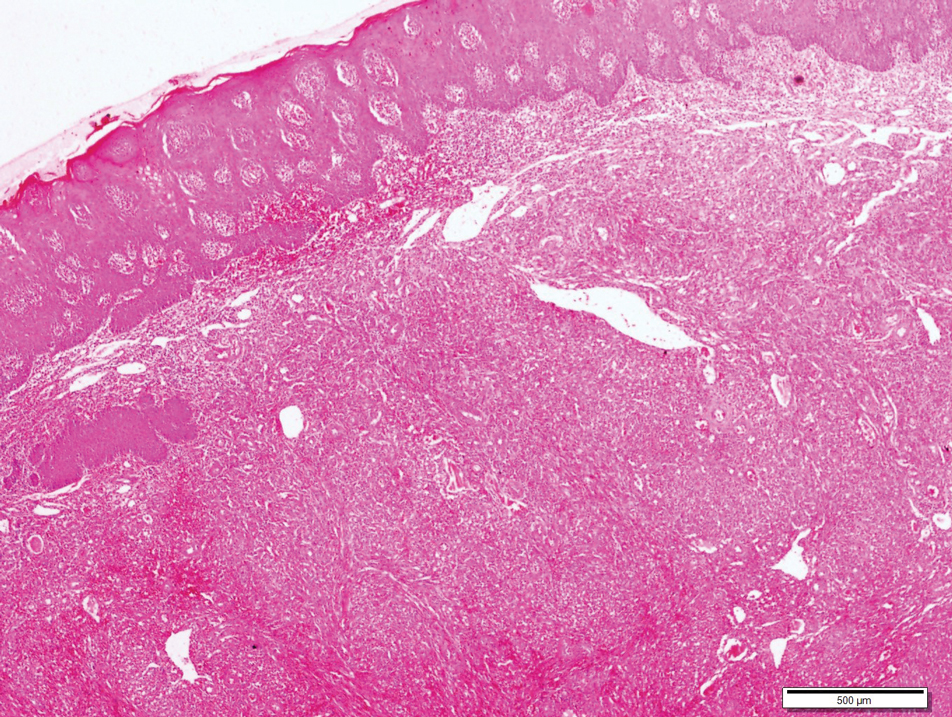

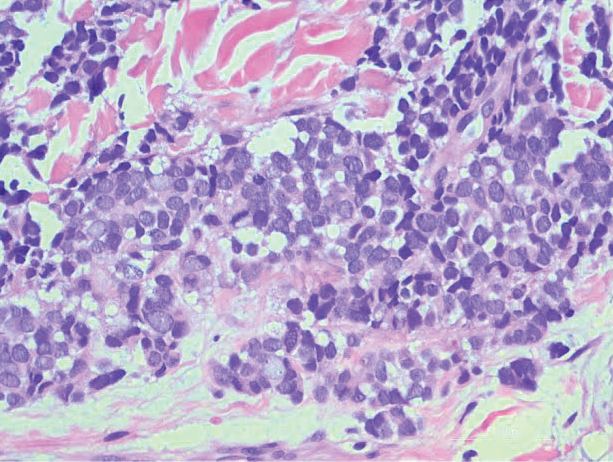

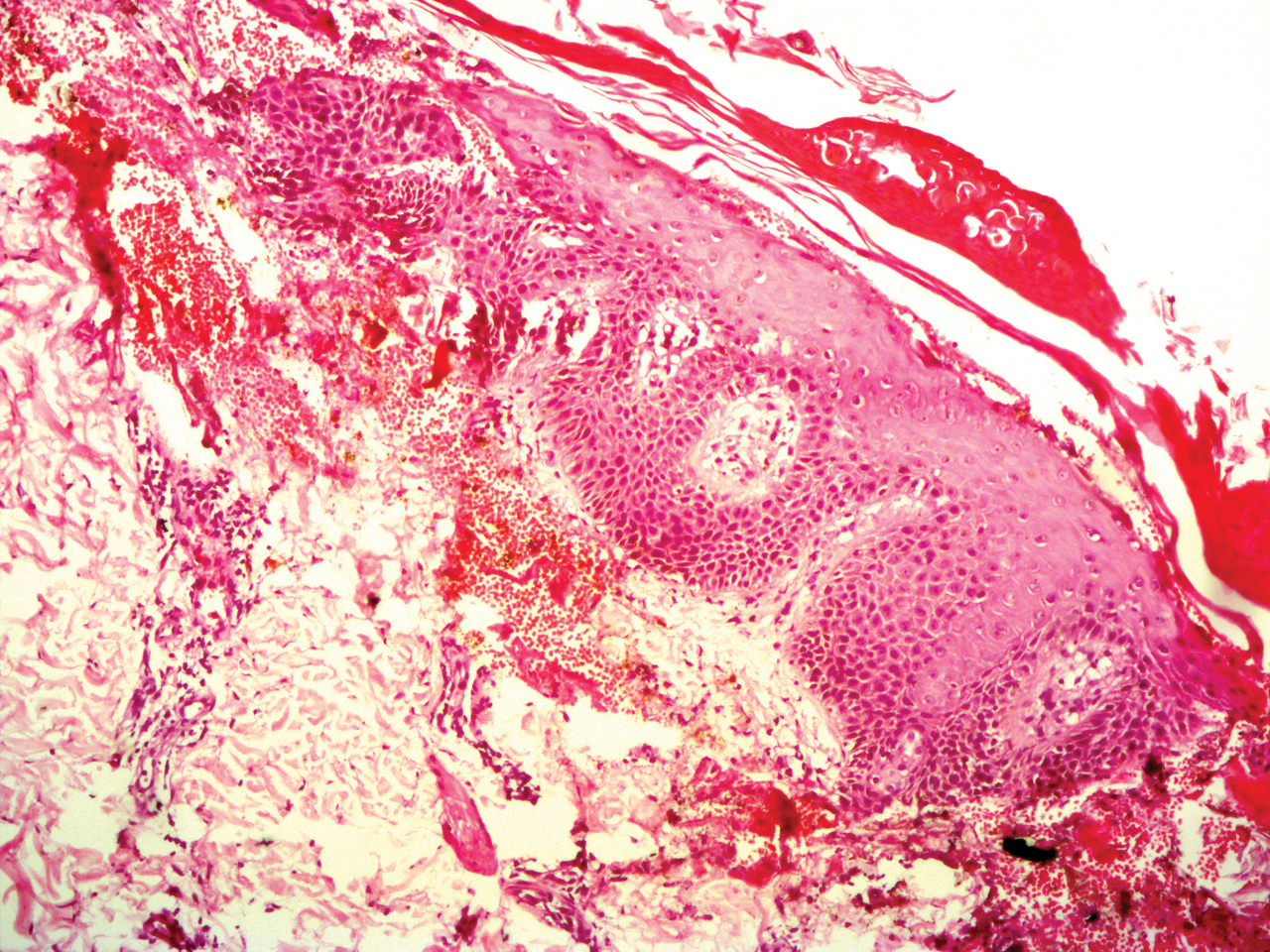

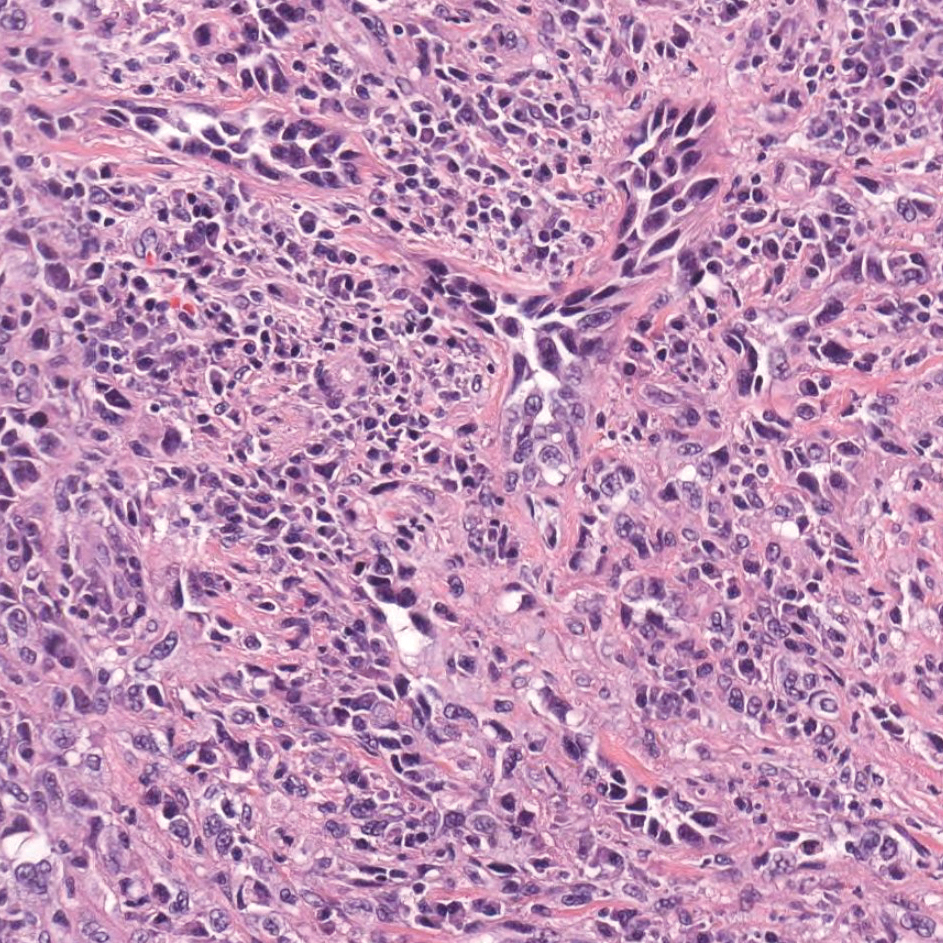

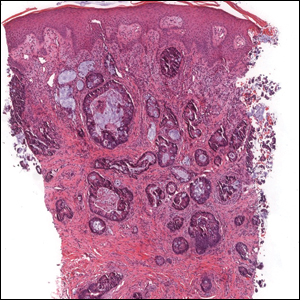

An excisional biopsy revealed that the dermis was mostly replaced by a malignant neoplastic infiltrate morphologically resembling small cell carcinoma (Figure 1). The cells had uniform hyperchromatic nuclei with fairly even chromatin and generally inconspicuous nucleoli. There was a tendency for smudgy artifacts at the periphery of the infiltrate, and the cells had relatively scant cytoplasm with slight streaming. Occasional apoptotic forms were present. Immunohistochemistry showed strong dotlike staining with cytokeratin 20 and moderate positivity with synaptophysin and chromogranin A (Figure 2). Unusually, there also was weak staining in a few tumor cells with thyroid transcription factor 1, a marker usually indicative of small cell carcinoma of the lungs that typically is negative in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). A second thyroid transcription factor 1 monoclonal antibody used in a double immunostain for lung adenocarcinomas was completely negative. This second antibody is more specific but less sensitive than the stand-alone version. The skin biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of MCC. Given the patient's frailty and comorbidities, wide local excision was not performed and the patient was referred to radiation oncology. He died several months later from metastatic MCC.

dermis was mostly replaced by a malignant neoplastic infiltrate morphologically resembling small cell carcinoma. The cells had uniform hyperchromatic nuclei with fairly even chromatin and generally inconspicuous nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×200).

Merkel cell carcinoma (original magnification ×200).

Merkel cell carcinoma is an uncommon skin malignancy that can be easily mistaken for other conditions if the clinician is not familiar with its typical presentation. It most commonly is found on the head and neck in elderly individuals, most often aged 60 to 80 years,1 with a notable history of sun exposure and/or immunosuppression. It is an aggressive skin cancer that originally was thought to be due to pathogenic changes of Merkel cells,2 which are specialized touch receptors located at the dermoepidermal junction of the skin; however, newer evidence has suggested that MCC arises from malignant changes to skin stem cells.3 It shares more characteristics with extracutaneous neuroendocrine tumors and is more aptly labeled by pathologists as a primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin.4

The frequency of MCC is highest in Australia, likely due to intense sun exposure, where the age-adjusted incidence rate reported in Queensland was 1.6 per 100,000 individuals from 2006 to 2010.5 The lowest incidence rates were reported in Finland (0.11 and 0.12 per 100,000 males and females, respectively)6 and Denmark (2.2 cases per million person-years).7 The clinical features of MCC are summarized by the mnemonic AEIOU: asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin.8 In a 2008 study of 195 patients, 89% of primary MCC lesions met 3 or more criteria, 32% met 4 or more criteria, and 7% met all 5 criteria.8

The classic presentation of MCC is a pink-red to violaceous nodule on the head or neck in an elderly patient, but there is a need to maintain suspicion of malignancy when examining a presumed infected cystic lesion, especially when a round of antibiotics has not ameliorated the symptoms. According to Heath et al,8 of 106 patients treated for MCC, 56% of first clinical impressions were benign. A PubMed and Scopus search was performed with the MeSH headings Merkel cell carcinoma +/- presentation to uncover similar unusual presentations between 1970 and the present day. Merkel cell carcinoma has been misdiagnosed as seemingly benign lesions including lipoma,9 allergic contact dermatitis,10 and atheroma.11 The differential diagnosis of MCC also includes cysts, amelanotic melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, squamous cell carcinoma, fungal kerion, leiomyosarcoma, neurothekeoma, abscesses, and cutaneous lymphoma.

Merkel cell polyomavirus has been implicated in the malignant transformation of MCC. It is a small, human, nonenveloped, double-stranded DNA virus1 and is found in approximately 70% to 80% of MCC cases.12 Merkel cell polyomavirus is a respiratory tract pathogen that is acquired by immunocompetent infants; it integrates itself into the host's genome and then enters a long latency period to later reactivate in immunocompromised adults.13

Wide local excision down to fascia is the mainstay of treatment of MCC, with recommended margins of 1 to 2 cm.14 Mohs micrographic surgery also can be considered.15 Similar to other neuroendocrine tumors, MCC is considered a radiosensitive tumor; radiation likely improves local control and is recommended in early-stage disease.16,17 It also has been described as the sole treatment modality in patients who are not candidates for surgery. The role of chemotherapy is more controversial, as responses do not appear to be long-lasting but should be considered in patients with advanced disease.14,18 There have been major advances in immunotherapy with the recent approvals of avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 inhibitor,19 and pembrolizumab,20 an anti-PD-1 inhibitor, for metastatic MCC. Clinical trials for MCC using kinase inhibitors and somatostatin analogues currently are ongoing.21

Several studies have demonstrated high rates of occult nodal disease in clinically node-negative patients, which has led to widespread use of sentinel lymph node biopsies.22,23 A sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended at the time of surgery to aid with treatment decisions and prognosis.24