User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

NORD and Other Patient Organizations Oppose Short-Term, Limited-Duration Health Plans

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

NORD has joined several other patient organizations in voicing opposition to proposed expansion of short-term, limited-duration health plans. NORD and its advocacy partners believe that expanding these plans would destabilize the insurance marketplace and increase premiums for those who are in the greatest need of care. For information, view the coalition letter to Congress here and letter to the Administration here.

Medical Nutrition Equity Act Capitol Hill Day Planned for June 1

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

As part of the Patients and Providers for Medical Nutrition Equity Coalition, NORD will participate in an advocacy day on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC, on Friday, June 1, 2018, in support of the Medical Nutrition Equity Act (H.R.2587, S.1194). This legislation would require the coverage of medical nutrition in Medicaid, Medicare, the Federal Employee Health Benefit Plan, and certain private insurance. For information on the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, view the coalition letter here.

More Than 100 Patient Organizations Join NORD in Supporting the RARE Act

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

NORD has sent a letter to Congress, signed by more than 100 patient advocacy organizations, in support of the Rare disease Advancement, Research, and Education Act of 2018 (H.R.5115) or the “RARE Act of 2018.” Read NORD’s letter to see how this proposed legislation would help patients and families affected by rare diseases, medical researchers, and clinicians seeking to provide optimal care for their patients.

RFPs Available for the Study of Three Rare Diseases

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

NORD’s Research Grant Program is still accepting proposals for the study of three rare diseases: cat eye syndrome, malonic aciduria, and post-orgasmic illness syndrome. All interested US and international researchers are encouraged to apply. Learn more.

2018 Marks 35th Anniversary of NORD and the Orphan Drug Act

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

In January of 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed the Orphan Drug Act, launching a new era of hope for the millions of Americans with diseases so rare that no pharmaceutical company was pursuing development of treatments. A few months later, the patient advocates who had worked together to get that law enacted formally announced their collaboration as the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), to provide advocacy, education, research, and patient services on behalf of all people affected by rare diseases. Throughout 2018, NORD and others in the rare disease community will be celebrating this 35th anniversary year. While only a dozen rare disease treatments had been developed by industry in the decade before 1983, more than 500 have been approved by FDA since then and many more are in the pipeline. Many of these are breakthrough therapies that have been life-saving, or have significantly improved quality of life, for patients who previously had no therapy. View archived video from 30th anniversary about the role of patient advocates in enactment of the Orphan Drug Act.

Register Now for NORD’s Rare Impact Awards Celebration

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

On Thursday, May 17, 2018, NORD will honor clinicians, researchers, patient advocates, and others who have made outstanding contributions to improving the lives of people with rare diseases. This will take place at the Rare Impact Awards event, which takes place each year at this time in Washington, DC. This year, the venue will be the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium. Individuals being honored include Robert Campbell, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who is receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award; Richard Pazdur, MD, of the FDA, who is receiving the Public Health Leadership Award; and Elisabeth Dykens, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, who is being honored for her research related to rare genetic syndromes. Read about all the honorees.

The Rare Impact Awards Celebration is open to the public. Registration is open now on the NORD website.

Plantar Ulcerative Lichen Planus: Rapid Improvement With a Novel Triple-Therapy Approach

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

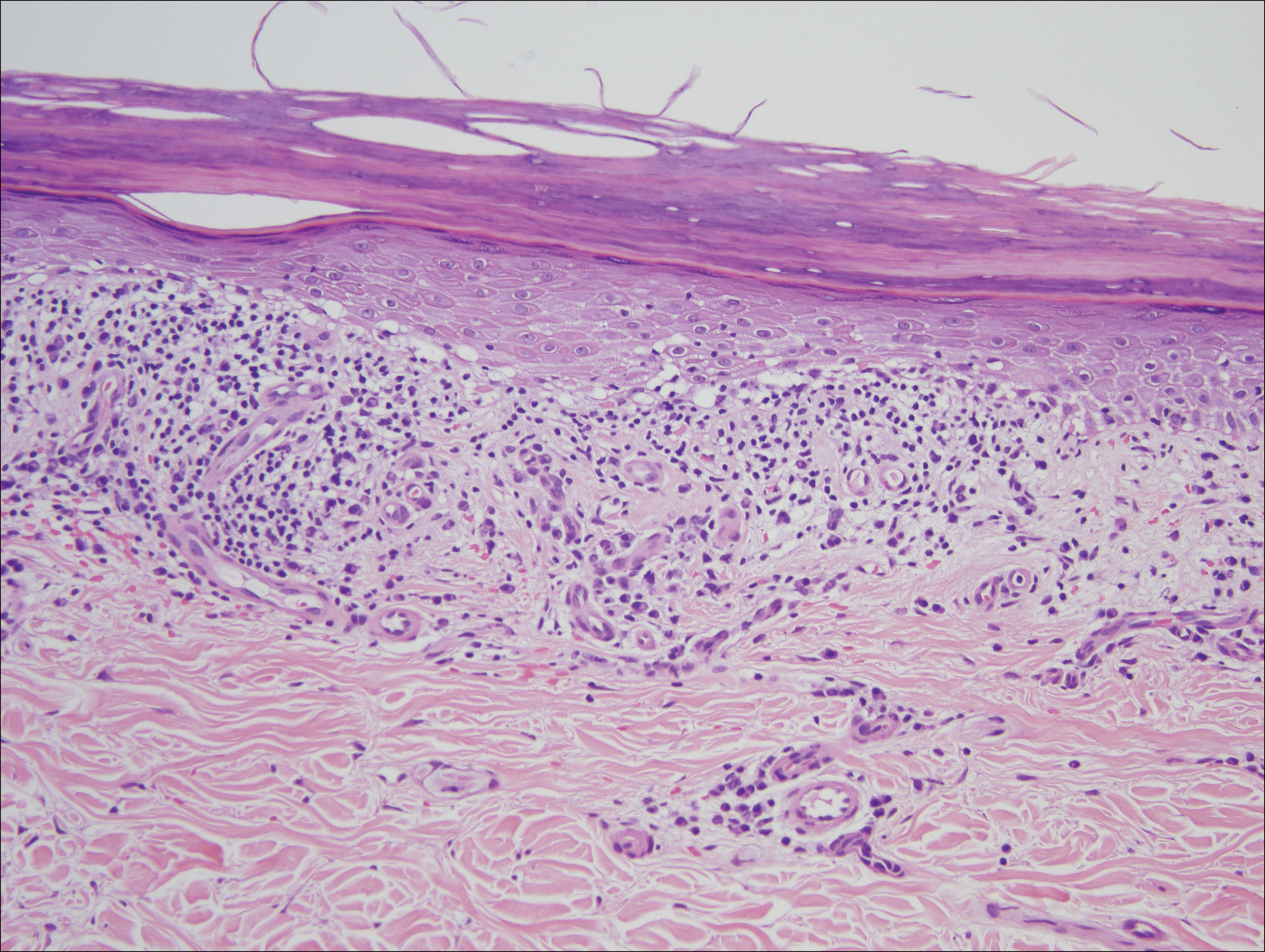

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

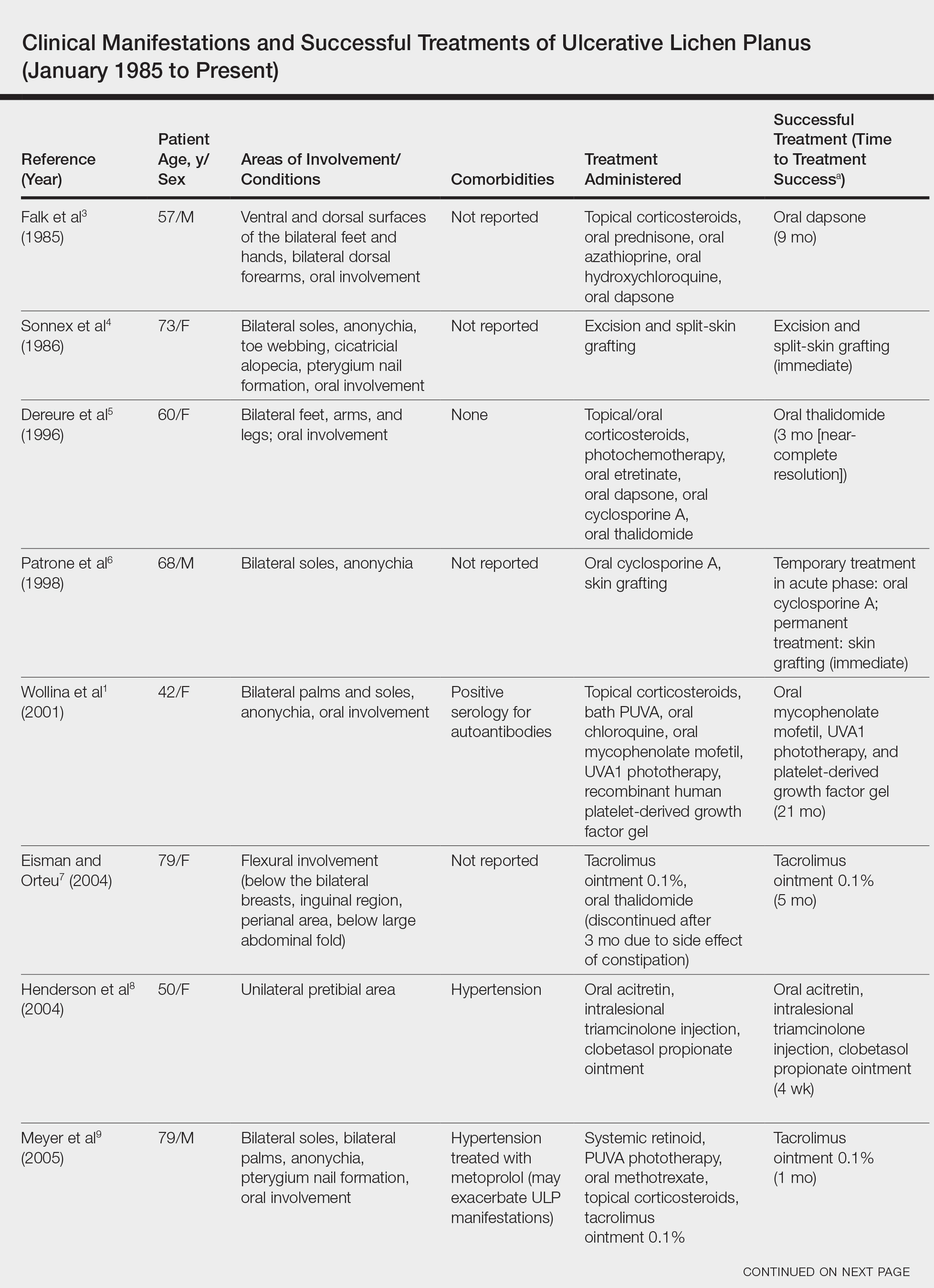

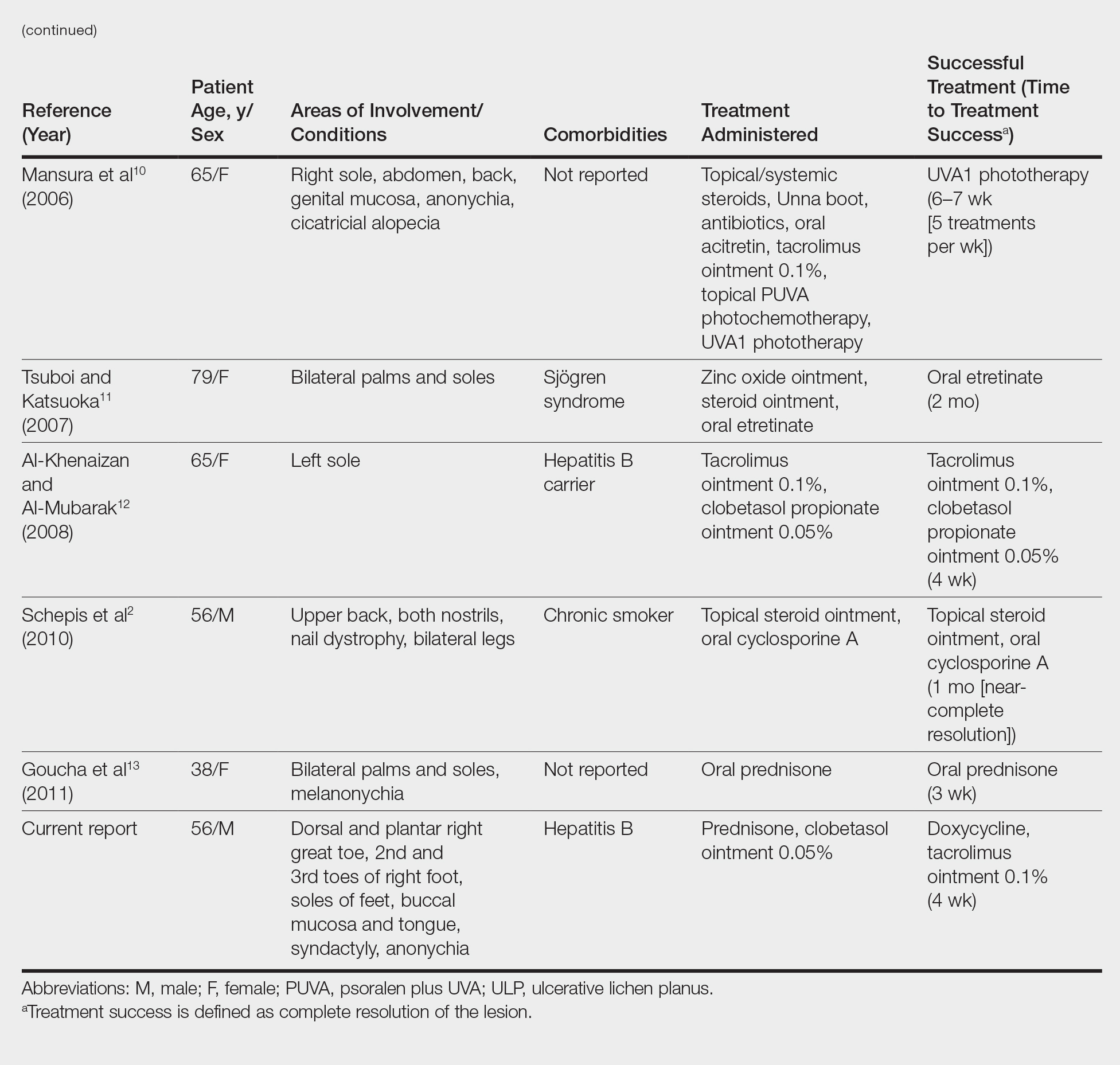

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

Ulcerative lichen planus (ULP)(also called erosive) is a rare variant of lichen planus. Similar to classic lichen planus, the cause of ULP is largely unknown. Ulcerative lichen planus typically involves the oral mucosa or genitalia but rarely may present as ulcerations on the palms and soles. Clinical presentation usually involves a history of chronic ulcers that often have been previously misdiagnosed and resistant to treatment. Ulcerations on the plantar surfaces frequently cause severe pain and disability. Few cases have been reported and successful treatment is rare.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man was referred by podiatry to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of painful ulcerations involving the dorsal and plantar surfaces of the right great toe as well as the second to third digits. The ulcers had been ongoing for 8 years, treated mostly with local wound care without clinical improvement. His medical and family history was considered noncontributory as a possible etiology of the ulcers; however, he had been taking ibuprofen intermittently for years for general aches and pains, which raised the suspicion of a drug-induced etiology. Laboratory evaluation revealed positive hepatitis B serology but was otherwise unremarkable, including normal liver function tests and negative wound cultures.

Physical examination revealed a beefy red, glazed ulceration involving the entire right great toe with extension onto the second and third toes. There was considerable scarring with syndactyly of the second and third toes and complete toenail loss of the right foot (Figure 1). On the insteps of the bilateral soles were a few scattered, pale, atrophic, violaceous papules with overlying thin lacy white streaks that were reflective of Wickham striae. Early dorsal pterygium formation also was noted on the bilateral third fingernails. Oral mucosal examination revealed lacy white plaques on the bilateral buccal mucosa with a large ulcer of the left lateral tongue (Figure 2). No genital or scalp lesions were present.

Histologic examination of a papule on the instep of the right sole demonstrated a dense lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate in the papillary dermis with basal vacuolar degeneration and early focal Max-Joseph space formation. Additionally, there was epidermal atrophy with mild hypergranulosis and scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 3). A similar histologic picture was noted on a biopsy of the buccal mucosa overlying the right molar, albeit with epithelial acanthosis rather than atrophy.

Based on initial clinical suspicion for ULP, we suggested that our patient discontinue ibuprofen and started him on a regimen of oral prednisone 40 mg once daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration, both for 2 weeks. Dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 weeks of treatment. This regimen was then switched to oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily combined with tacrolimus ointment 0.1% applied twice daily to the plantar ulceration to avoid side effects of prolonged steroid use. Topical therapies were not used for the mucosal lesions. At 4-week follow-up, the patient continued to demonstrate notable clinical response with a greater than 70% physician-assessed improvement in ulcer severity (Figure 4) and near-complete resolution of the oral mucosal lesions. Our patient also reported almost complete resolution of pain. By 4-month follow-up, complete reepithelialization and resolution of the ulcers was noted (Figure 5). This improvement was sustained at additional follow-up 1 year after the initial presentation.

Comment

Ulcerative (or erosive) lichen planus is a rare form of lichen planus. Ulcerative lichen planus most commonly presents as erosive lesions of the oral and genital mucosae but rarely can involve other sites. The palms and soles are the most common sites of cutaneous involvement, with lesions frequently characterized by severe pain and limited mobility.2

We conducted a review of the Ovid MEDLINE database using the search terms ulcerative lichen planus and erosive lichen planus for articles from the last 30 years, focusing specifically on articles that reported cases of cutaneous involvement of ULP and successful therapeutic modalities. The Table provides a detailed summary of the cases from 1985 to present, representing a spectrum of clinical manifestations and successful treatments of ULP.1-13

Hepatitis C is a comorbidity commonly associated with classic lichen planus, while hepatitis B immunization has a well-described association with classic and oral ULP.12,14 Although hepatitis C was negative in our patient, we did find a chronic inactive carrier state for hepatitis B infection. Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported the only other known case of ULP of the sole associated with positive serology for hepatitis B surface antigen.

Ulcerative lichen planus of the soles can be difficult to diagnose, especially when it is an isolated finding. It should be differentiated from localized bullous pemphigoid, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, ulcerative lupus erythematosus, and dermatitis artefacta.13 The characteristic associated clinical features of plantar ULP in our patient and lack of diagnostic immunofluorescence helped us to rule out these alternative diagnoses.4 Long-standing ulcerations of ULP also pose an increased risk for neoplastic transformation. Eisen15 noted a 0.4% to 5% frequency of malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma in those with oral ULP. Therefore, it is important to monitor previously ulcerated lesions long-term for such development.

Plantar ULP is difficult to treat and often is unresponsive to systemic and local treatment. Historically, surgical grafting of the affected areas was the treatment of choice, as reported by Patrone et al.6 Goucha et al13 reported complete healing of ulcerations within 3 weeks of starting oral prednisone 1 mg/kg once daily followed by a maintenance dosage of 5 mg once daily. Tacrolimus is a macrolide immunosuppressant that inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK506 binding protein in the cytoplasm of T cells that binds and inhibits calcineurin dephosphorylation of nuclear factor of activated T cells.12 Al-Khenaizan and Al-Mubarak12 reported resolution of plantar ULP ulcerations after 4 weeks of treatment with topical tacrolimus. Eisman and Orteu7 also achieved complete healing of ulcerations of plantar ULP using tacrolimus ointment 0.1%.

In our patient, doxycycline also was started at the time of initiating the topical tacrolimus. We chose this treatment to take advantage of its systemic anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antibacterial properties. Our case represents rapid and successful treatment of plantar ULP utilizing this specific combination of oral doxycycline and topical tacrolimus.

Conclusion

Ulcerative lichen planus is an uncommon variant of lichen planus, with cutaneous involvement only rarely reported in the literature. Physicians should be aware of this entity and should consider it in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with chronic ulcers on the soles, especially when lesions have been unresponsive to appropriate wound care and antibiotic treatment or when cultures have been persistently negative for microbial growth. The possibility of drug-induced lichen planus also should not be overlooked, and one should consider discontinuation of all nonessential medications that could be potential culprits. In our patient ibuprofen was discontinued, but we can only speculate that it was contributory to his healing and only time will tell if resumption of this nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug causes a relapse in symptoms.

In our patient, a combination of systemic and topical steroids, topical tacrolimus, and oral doxycycline successfully treated his plantar ULP. Our findings provide further support for the use of topical tacrolimus as a steroid-sparing anti-inflammatory agent for the treatment of plantar ULP. We also introduce the combination of topical tacrolimus and oral doxycycline as a novel therapeutic combination and relatively safer alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term systemic anti-inflammatory effects.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

- Wollina U, Konrad H, Graefe T. Ulcerative lichen planus: a case responding to recombinant platelet-derived growth factor BB and immunosuppression. Acta Derm Venereol. 2001;81:364-383.

- Schepis C, Lentini M, Siragusa M. Erosive lichen planus on an atypical site mimicking a factitial dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:185-186.

- Falk DK, Latour DL, King EL. Dapsone in the treatment of erosive lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:567-570.

- Sonnex TS, Eady RA, Sparrow GP, et al. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with webbing of the toes. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:363-365.

- Dereure O, Basset-Sequin N, Guilhou JJ. Erosive lichen planus: dramatic response to thalidomide. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:1392-1393.

- Patrone P, Stinco G, La Pia E, et al. Surgery and cyclosporine A in the treatment of erosive lichen planus of the feet. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:243-244.

- Eisman S, Orteu C. Recalcitrant erosive flexural lichen planus: successful treatment with a combination of thalidomide and 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:268-270.

- Henderson RL Jr, Williford PM, Molnar JA. Cutaneous ulcerative lichen planus exhibiting pathergy, response to acitretin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:191-192.

- Meyer S, Burgdorf T, Szeimies R, et al. Management of erosive lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and recurrence secondary to metoprolol. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:236-239.

- Mansura A, Alkalay R, Slodownik D, et al. Ultraviolet A-1 as a treatment for ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Pathomed. 2006;22:164-165.

- Tsuboi H, Katsuoka K. Ulcerative lichen planus associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. J Dermatol. 2007;34:131-134.

- Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Mubarak L. Ulcerative lichen planus of the sole: excellent response to topical tacrolimus. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:626-628.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Rammeh S, et al. Erosive lichen planus of the soles: effective response to prednisone. Dermatol Ther. 2011;1:20-24.

- Binesh F, Parichehr K. Erosive lichen planus of the scalp and hepatitis C infection. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2013;23:169.

- Eisen D. The clinical features, malignant potential, and systemic associations of oral lichen planus: a study of 723 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:207-214.

Practice Points

- Consider ulcerative lichen planus (ULP) for chronic wounds on the soles.

- Topical therapeutic options may present a rapidly effective and relatively safe alternative to conventional immunosuppressive agents for long-term management of plantar ULP.

Impact of Provider Attire on Patient Satisfaction in an Outpatient Dermatology Clinic

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

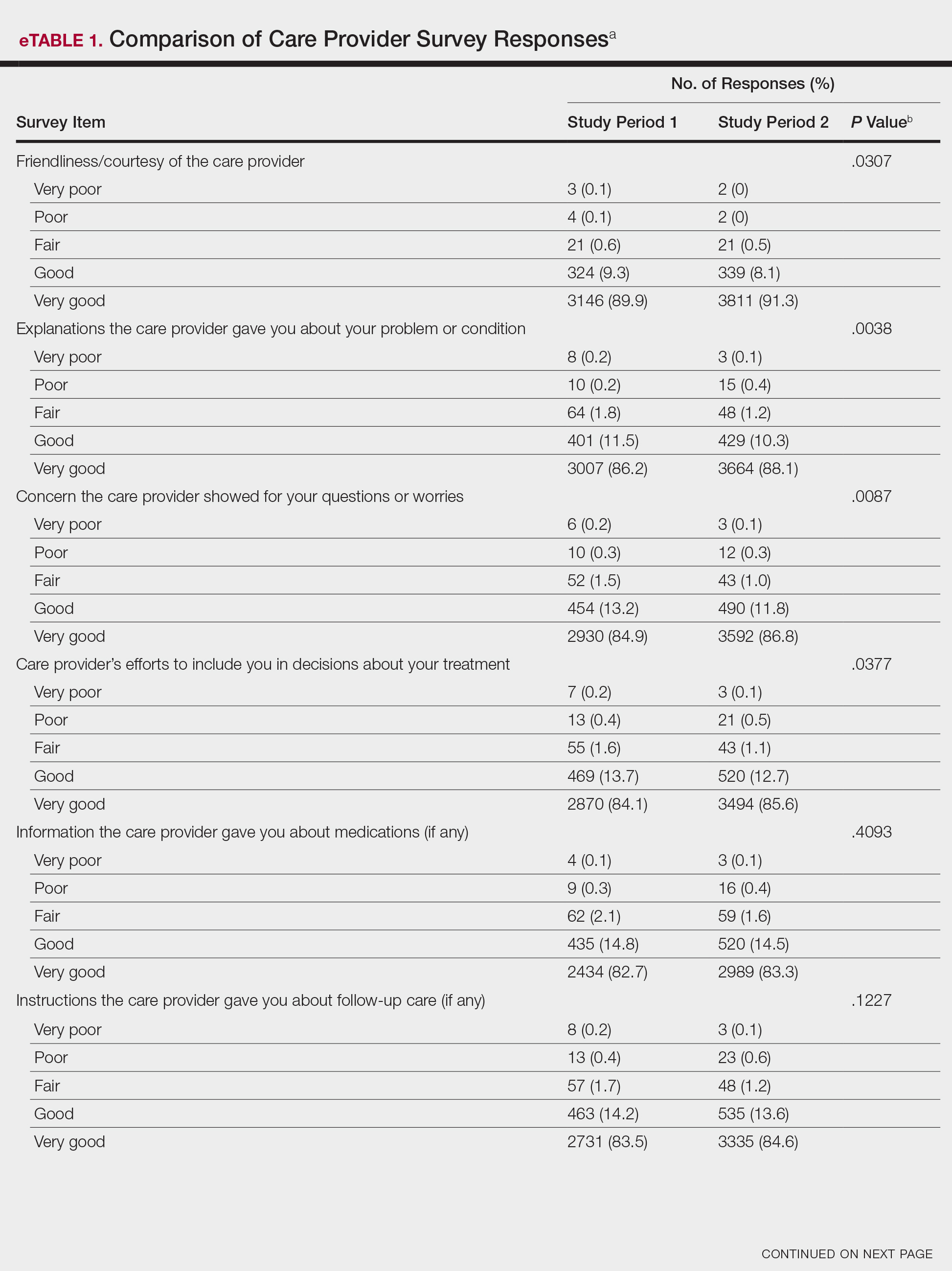

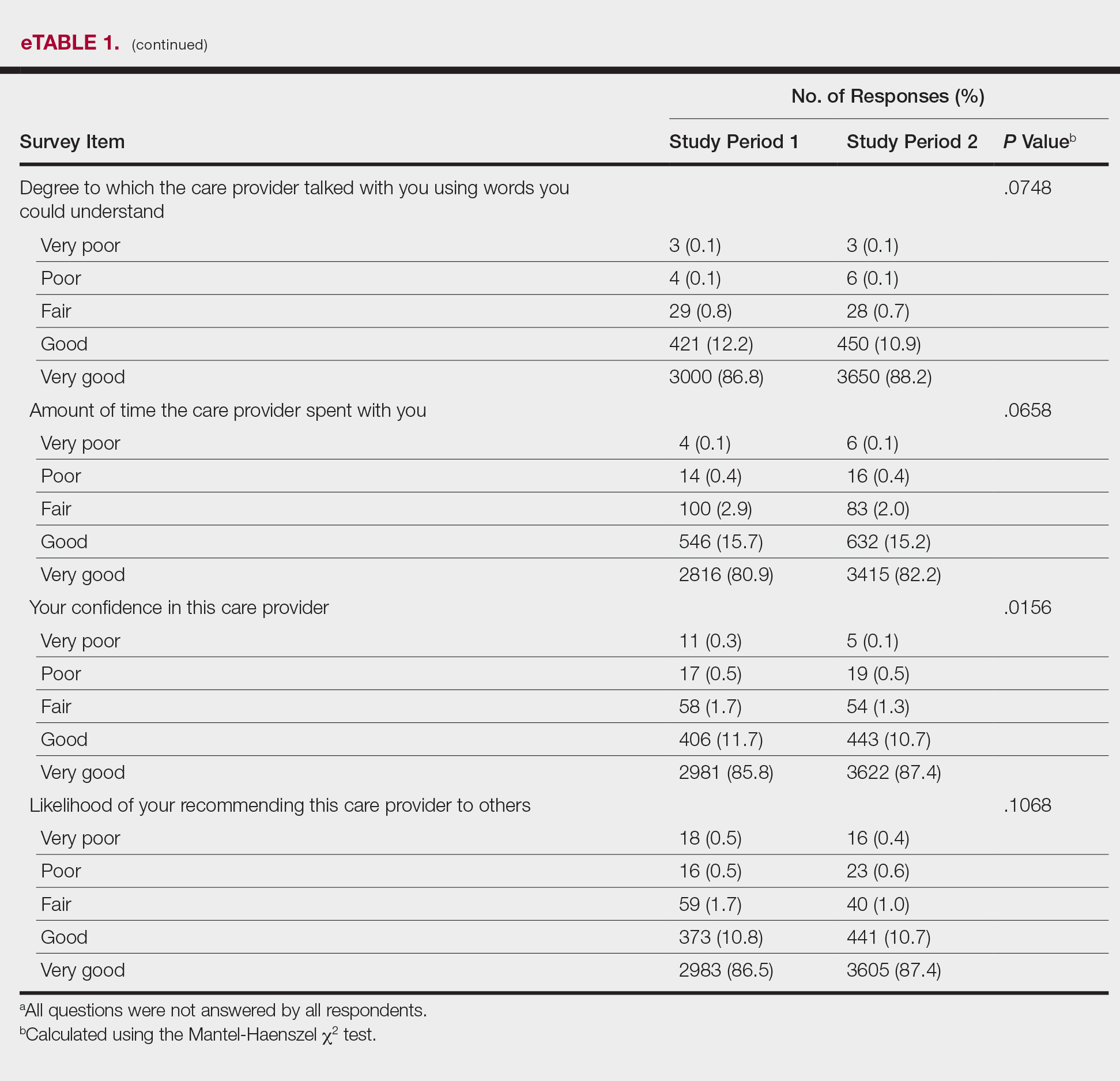

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic

Anecdotally, most providers in our department were enthusiastic and supportive of the change to fitted scrubs. It is possible that provider happiness is reflected in improved patient satisfaction scores. Provider satisfaction has been shown to correlate with patient satisfaction.7

Limitations include possible other unmeasured variables that had a more substantial impact on patient satisfaction survey results. We also recognize that the survey used in this study contained no questions that directly asked patients about their satisfaction with provider attire; however, bias or any preconception patients may have had regarding attire may have been avoided in the process. We also were not able to separate patient surveys based on age or other demographics. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other settings where patient perceptions may be different from those of central Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

Transitioning from formal provider attire to fitted scrubs did not have a strong impact on overall patient satisfaction scores in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Providers and institutions should consider this information when developing dress code policies.

- Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, et al. Expert guidance: healthcare personnel attire in non-operating room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:107-121.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Maruani A, Léger J, Giraudeau B, et al. Effect of physician dress style on patient confidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E333-E337.

- Guadagnino C. Patient satisfaction critical to hospital value-based purchasing program. The Hospitalist. Published October 2012. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/article/patient-satisfaction-critical-to-hospital-value-based-purchasing-program/. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, et al. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:201-203.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122-128.

- Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL, et al. Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:186.e1-186.e5.

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic

Anecdotally, most providers in our department were enthusiastic and supportive of the change to fitted scrubs. It is possible that provider happiness is reflected in improved patient satisfaction scores. Provider satisfaction has been shown to correlate with patient satisfaction.7

Limitations include possible other unmeasured variables that had a more substantial impact on patient satisfaction survey results. We also recognize that the survey used in this study contained no questions that directly asked patients about their satisfaction with provider attire; however, bias or any preconception patients may have had regarding attire may have been avoided in the process. We also were not able to separate patient surveys based on age or other demographics. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other settings where patient perceptions may be different from those of central Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

Transitioning from formal provider attire to fitted scrubs did not have a strong impact on overall patient satisfaction scores in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Providers and institutions should consider this information when developing dress code policies.

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic