User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Wound Healing: Cellular Review With Specific Attention to Postamputation Care

Restoring skin integrity and balance after injury is vital for survival, serving as a crucial defense mechanism against potential infections by preventing the entry of harmful pathogens. Moreover, proper healing is essential for restoring normal tissue function, allowing damaged tissues to repair and, in an ideal scenario, regenerate. Timely healing helps reduce the risk for complications, such as chronic wounds, which could lead to more severe issues if left untreated. Additionally, pain relief often is associated with effective wound healing as inflammatory responses diminish during the repair process.

The immune system plays a pivotal role in wound healing, influencing various repair mechanisms and ultimately determining the extent of scarring. Although inflammation is present throughout the repair response, recent studies have challenged the conventional belief of an inverse correlation between the intensity of inflammation and regenerative capacity. Inflammatory signals were found to be crucial for timely repair and fundamental processes in regeneration, possibly presenting a paradigm shift in the understanding of immunology.1-4 The complexities of wound healing are exemplified when evaluating and treating postamputation wounds. To address such a task, one needs a firm understanding of the science behind healing wounds and what can go wrong along the way.

Phases of Wound Healing

Wound healing is a complex process that involves a series of sequential yet overlapping phases, including hemostasis/inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.

Hemostasis/Inflammation—The initial stage of wound healing involves hemostasis, in which the primary objective is to prevent blood loss and initiate inflammation. Platelets arrive at the wound site, forming a provisional clot that is crucial for subsequent healing phases.4-6 Platelets halt bleeding as well as act as a medium for cell migration and adhesion; they also are a source of growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines that herald the inflammatory response.4-7

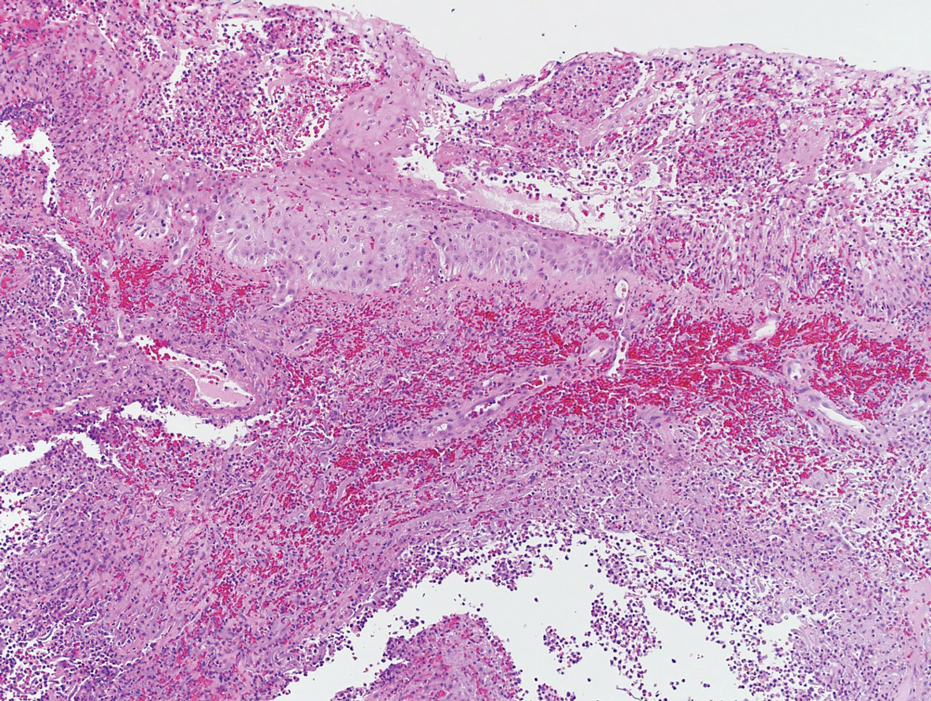

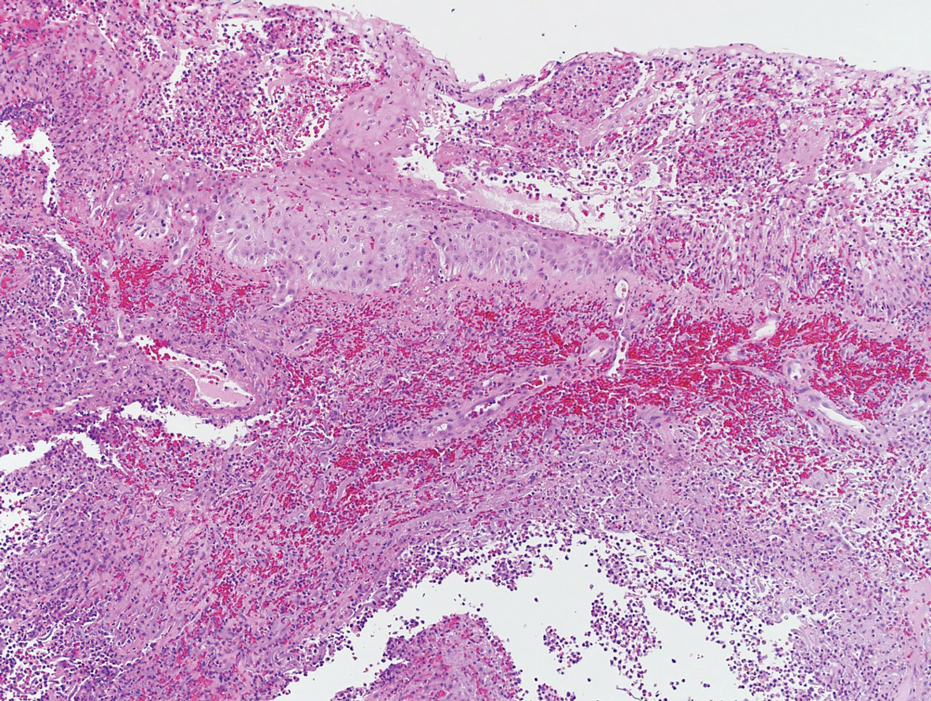

Inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of immune cells, particularly neutrophils and macrophages. Neutrophils act as the first line of defense, clearing debris and preventing infection. Macrophages follow, phagocytizing apoptotic cells and releasing growth factors such as tumor necrosis factor α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloprotease 9, which stimulate the next phase.4-6,8 Typically, the hemostasis and inflammatory phase starts approximately 6 to 8 hours after wound origin and lasts 3 to 4 days.4,6,7

Proliferation—Following hemostasis and inflammation, the wound transitions into the proliferation phase, which is marked by the development of granulation tissue—a dynamic amalgamation of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells.1,4-8 Fibroblasts play a central role in synthesizing collagen, the primary structural protein in connective tissue. They also orchestrate synthesis of vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrin, and tenascin.4-6,8 Simultaneously, angiogenesis takes place, involving the creation of new blood vessels to supply essential nutrients and oxygen to the healing tissue.4,7,9 Growth factors such as transforming growth factor β and vascular endothelial growth factor coordinate cellular activities and foster tissue repair.4-6,8 The proliferation phase extends over days to weeks, laying the groundwork for subsequent tissue restructuring.

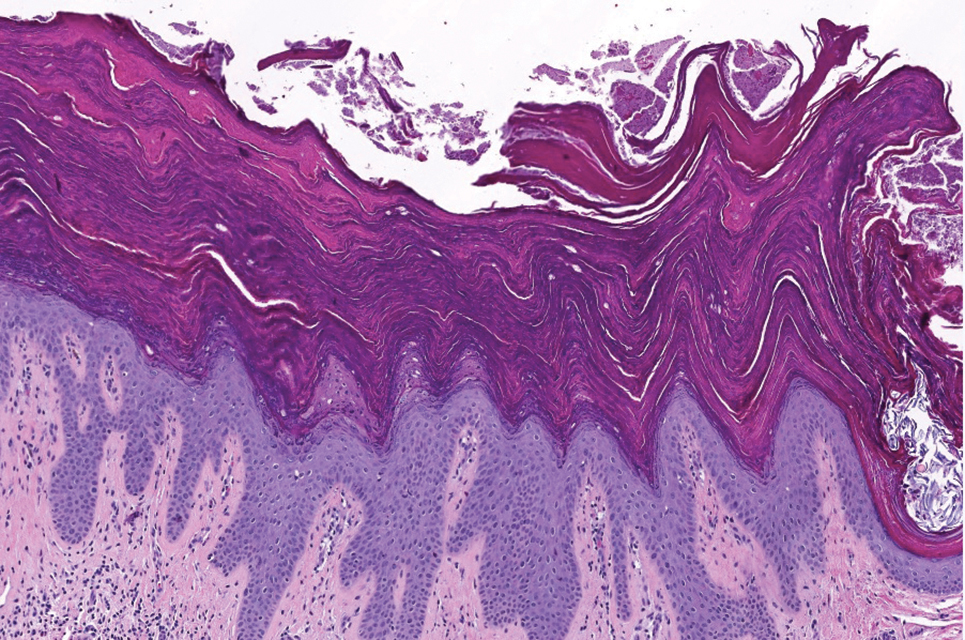

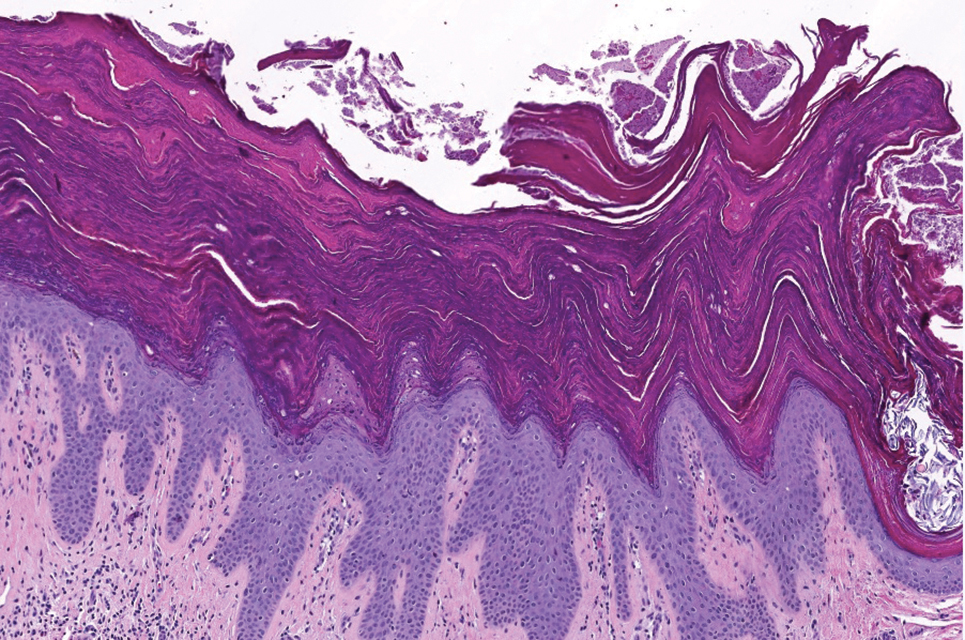

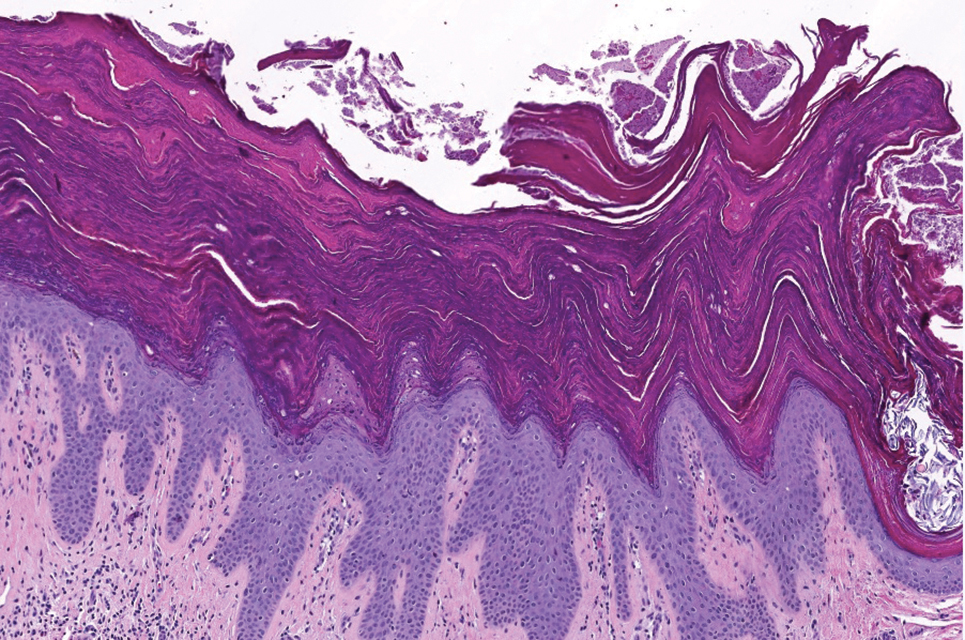

Remodeling—The final stage of wound healing is remodeling, an extended process that may persist for several months or, in some cases, years. Throughout this phase, the initially deposited collagen, predominantly type III collagen, undergoes transformation into mature type I collagen.4-6,8 This transformation is critical for reinstating the tissue’s strength and functionality. The balance between collagen synthesis and degradation is delicate, regulated by matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitors of metalloproteinases.4-8 Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and other cells coordinate this intricate process of tissue reorganization.4-7

The eventual outcome of the remodeling phase determines the appearance and functionality of the healed tissue. Any disruption in this phase can lead to complications, such as chronic wounds and hypertrophic scars/keloids.4-6 These abnormal healing processes are characterized by localized inflammation, heightened fibroblast function, and excessive accumulation of the extracellular matrix.4-8

Molecular Mechanisms

Comprehensive investigations—both in vivo and in vitro—have explored the intricate molecular mechanisms involved in heightened wound healing. Transforming growth factor β takes center stage as a crucial factor, prompting the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and contributing to the deposition of extracellular matrix.2,4-8,10 Transforming growth factor β activates non-Smad signaling pathways, such as MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), influencing processes associated with fibrosis.5,11 Furthermore, microRNAs play a pivotal role in posttranscriptional regulation, influencing both transforming growth factor β signaling and fibroblast behavior.12-16

The involvement of prostaglandins is crucial in wound healing. Prostaglandin E2 plays a notable role and is positively correlated with the rate of wound healing.5 The cyclooxygenase pathway, pivotal for prostaglandin synthesis, becomes a target for inflammation control.4,5,10 Although aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs commonly are employed, their impact on wound healing remains controversial, as inhibition of cyclooxygenase may disrupt normal repair processes.5,17,18

Wound healing exhibits variations depending on age. Fetal skin regeneration is marked by the restoration of normal dermal architecture, including adnexal structures, nerves, vessels, and muscle.4-6 The distinctive characteristics of fetal wound healing include a unique profile of growth factors, a diminished inflammatory response, reduced biomechanical stress, and a distinct extracellular matrix composition.19 These factors contribute to a lower propensity for scar formation compared to the healing processes observed in adults. Fetal and adult wound healing differ fundamentally in their extracellular matrix composition, inflammatory cells, and cytokine levels.4-6,19 Adult wounds feature myofibroblasts, which are absent in fetal wounds, contributing to heightened mechanical tension.5 Delving deeper into the biochemical basis of fetal wound healing holds promise for mitigating scar formation in adults.

Takeaways From Other Species

Much of the biochemical knowledge of wound healing, especially regenerative wound healing, is known from other species. Geckos provide a unique model for studying regenerative repair in tails and nonregenerative healing in limbs after amputation. Scar-free wound healing is characterized by rapid wound closure, delayed blood vessel development, and collagen deposition, which contrasts with the hypervascular granulation tissue seen in scarring wounds.20 Scar-free wound healing and regeneration are intrinsic properties of the lizard tail and are unaffected by the location or method of detachment.21

Compared to amphibians with extraordinary regenerative capacity, data suggest the lack of regenerative capacity in mammals may come from a desynchronization of the fine-tuned interplay of progenitor cells such as blastema and differentiated cells.22,23 In mice, the response to amputation is specific to the level: cutting through the distal third of the terminal phalanx elicits a regeneration response, yielding a new digit tip resembling the lost one, while an amputation through the distal third of the intermediate phalanx triggers a wound healing and scarring response.24

Wound Healing Following Limb Amputation

Limb amputation represents a profound change in an individual’s life, impacting daily activities and overall well-being. There are many causes of amputation, but the most common include cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and trauma.25-27 Trauma represents a relatively common cause within the US Military due to the overall young population as well as inherent risks of uniformed service.25,27 Advances in protective gear and combat casualty care have led to an increased number of individuals surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation, particularly among younger service members, with a subgroup experiencing multiple amputations.27-29

Numerous factors play a crucial role in the healing and function of postamputation wounds. The level of amputation is a key determinant influencing both functional outcomes and the healing process. Achieving a balance between preserving function and removing damaged tissue is essential. A study investigating cardiac function and oxygen consumption in 25 patients with peripheral vascular disease found higher-level amputations resulted in decreased walking speed and cadence, along with increased oxygen consumption per meter walked.30

Selecting the appropriate amputation level is vital to optimize functional outcomes without compromising wound healing. Successful prosthetic limb fitting depends largely on the length of the residual stump to support the body load and suspend the prosthesis. For long bone amputations, maintaining at least 12-cm clearance above the knee joint in transfemoral amputees and 10-cm below the knee joint in transtibial amputees is critical for maximizing functional outcomes.31

Surgical technique also is paramount. The goal is to minimize the risk for pressure ulcers by avoiding bony spurs and muscle imbalances. Shaping the muscle and residual limb is essential for proper prosthesis fitting. Attention to neurovascular structures, such as burying nerve ends to prevent neuropathic pain during prosthesis wear, is crucial.32 In extremity amputations, surgeons often resort to free flap transfer techniques for stump reconstruction. In a study of 31 patients with severe lower extremity injuries undergoing various amputations, the use of latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps, alone or in combination with serratus anterior muscle flaps, resulted in fewer instances of deep ulceration and allowed for earlier prosthesis wear.33

Addressing Barriers to Wound Healing

Multiple barriers to successful wound healing are encountered in the amputee population. Amputations from trauma have a less-controlled initiation, which carries with it a higher risk for infection, poor wound healing, and other complications.

Infection—Infection often is one of the first hurdles encountered in postamputation wound healing. Critical first steps in infection prevention include thorough cleaning of soiled traumatic wounds and appropriate tissue debridement coupled with scrupulous sterile technique and postoperative monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection.

In a retrospective study of 223 combat-related major lower extremity amputations (initial and revision) between 2009 and 2015, the use of intrawound antibiotic powder at the time of closure demonstrated a 13% absolute risk reduction in deep infection rates, which was particularly notable in revision amputations, with a number needed to treat of 8 for initial amputations and 4 for revision amputations on previously infected limbs.34 Intra-operative antibiotic powder may represent a cheap and easy consideration for this special population of amputees. Postamputation antibiotic prophylaxis for infection prevention is an area of controversy. For nontraumatic infections, data suggest antibiotic prophylaxis may not decrease infection rates in these patients.35,36

Interestingly, a study by Azarbal et al37 aimed to investigate the correlation between nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization and other patient factors with wound occurrence following major lower extremity amputation. The study found MRSA colonization was associated with higher rates of overall wound occurrence as well as wound occurrence due to wound infection. These data suggest nasal MRSA eradication may improve postoperative wound outcomes after major lower extremity amputation.37

Dressing Choice—The dressing chosen for a residual limb also is of paramount importance following amputation. The personalized and dynamic management of postamputation wounds and skin involves achieving optimal healing through a dressing that sustains appropriate moisture levels, addresses edema, helps prevent contractures, and safeguards the limb.38 From the start, using negative pressure wound dressings after surgical amputation can decrease wound-related complications.39

Topical oxygen therapy following amputation also shows promise. In a retrospective case series by Kalliainen et al,40 topical oxygen therapy applied to 58 wounds in 32 patients over 9 months demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting wound healing, with 38 wounds (66%) healing completely with the use of topical oxygen. Minimal complications and no detrimental effects were observed.40

Current recommendations suggest that non–weight-bearing removable rigid dressings are the superior postoperative management for transtibial amputations compared to soft dressings, offering benefits such as faster healing, reduced limb edema, earlier ambulation, preparatory shaping for prosthetic use, and prevention of knee flexion contractures.41-46 Similarly, adding a silicone liner following amputation significantly reduced the duration of prosthetic rehabilitation compared with a conventional soft dressing program in one study (P<.05).47

Specifically targeting wound edema, a case series by Hoskins et al48 investigated the impact of prostheses with vacuum-assisted suspension on the size of residual limb wounds in individuals with transtibial amputation. Well-fitting sockets with vacuum-assisted suspension did not impede wound healing, and the results suggest the potential for continued prosthesis use during the healing process.48 However, a study by Johannesson et al49 compared the outcomes of transtibial amputation patients using a vacuum-formed rigid dressing and a conventional rigid plaster dressing, finding no significant differences in wound healing, time to prosthetic fitting, or functional outcomes with the prosthesis between the 2 groups. When comparing elastic bandaging, pneumatic prosthesis, and temporary prosthesis on postoperative stump management, temporary prosthesis led to a decrease in stump volume, quicker transition to a permanent prosthesis, and improved quality of life compared with elastic bandaging and pneumatic prosthetics.50

The type of material in dressings may contribute to utility in amputation wounds. Keratin-based wound dressings show promise for wound healing, especially in recalcitrant vascular wounds.51 There also are numerous proprietary wound dressings available for patients, at least one of which has particularly thorough data. In a retrospective study of more than 2 million lower extremity wounds across 644 institutions, a proprietary bioactive human skin allograft (TheraSkin [LifeNet Health]) demonstrated higher healing rates, greater percentage area reductions, lower amputations, reduced recidivism, higher treatment completion, and fewer medical transfers compared with standard of care alone.52

Postamputation Dermatologic Concerns

After the postamputation wound heals, a notable concern is the prevalence of skin diseases affecting residual limbs. The stump site in amputees, marked by a delicate cutaneous landscape vulnerable to skin diseases, faces challenges arising from amputation-induced damage to various structures.53

When integrated into a prosthesis socket, the altered skin must acclimate to a humid environment and endure forces for which it is not well suited, especially during movement.53 Amputation remarkably alters normal tissue perfusion, which can lead to aberrant blood and lymphatic circulation in residual limbs.27,53 This compromised skin, often associated with a history of vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or malignancy, becomes immunocompromised, heightening the risk for dermatologic issues such as inflammation, infection, and malignancies.53 Unlike the resilient volar skin on palms and soles, stump skin lacks adaptation to withstand the compressive forces generated during ambulation, sometimes leading to skin disease and pain that result in abandonment of the prosthesis.53,54 Mechanical forces on the skin, especially in active patients eager to resume pre-injury lifestyles, contribute to skin breakdown. The dynamic nature of the residual limb, including muscle atrophy, gait changes, and weight fluctuations, complicates the prosthetic fitting process. Prosthesis abandonment remains a challenge, despite modern technologic advancements.

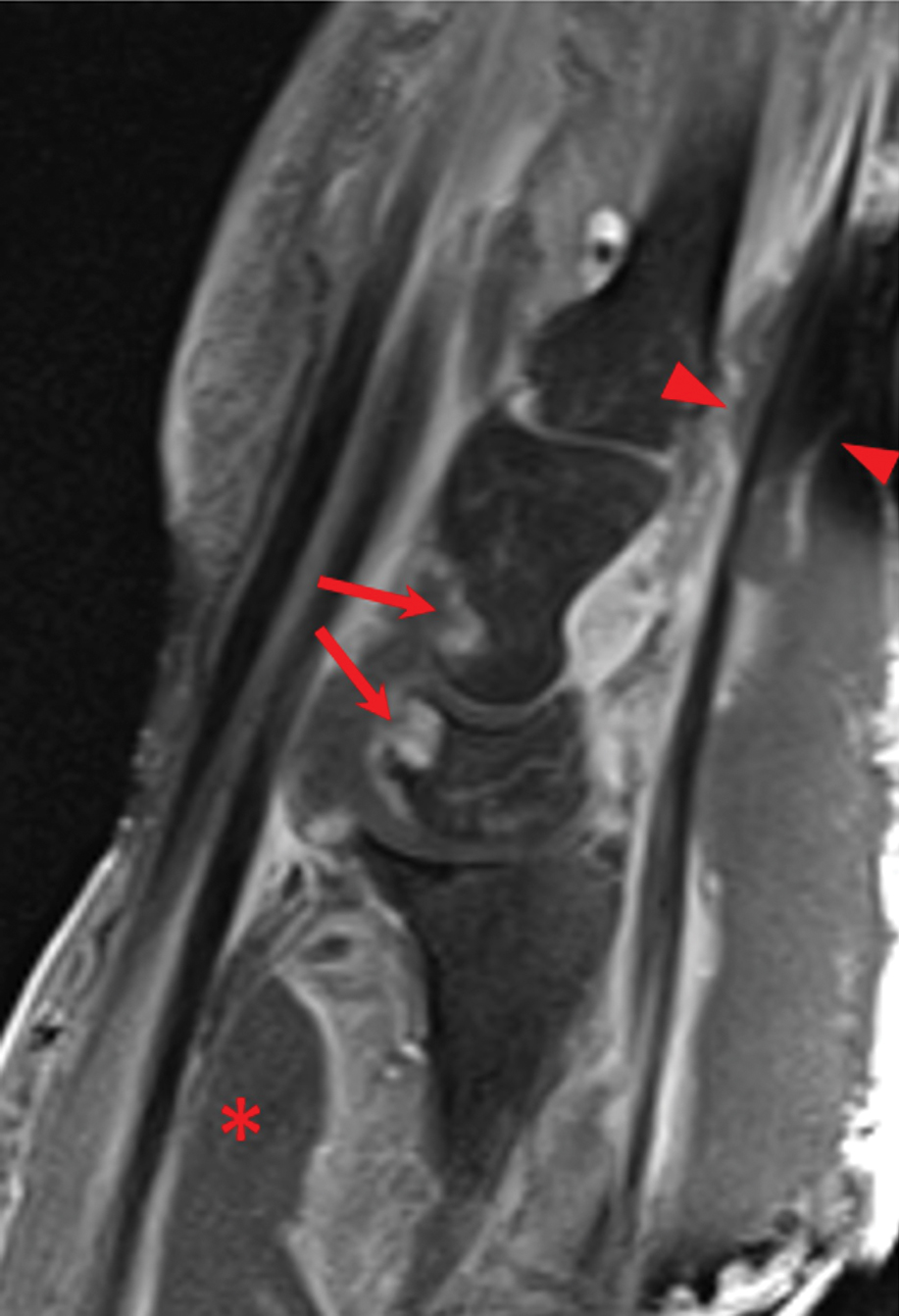

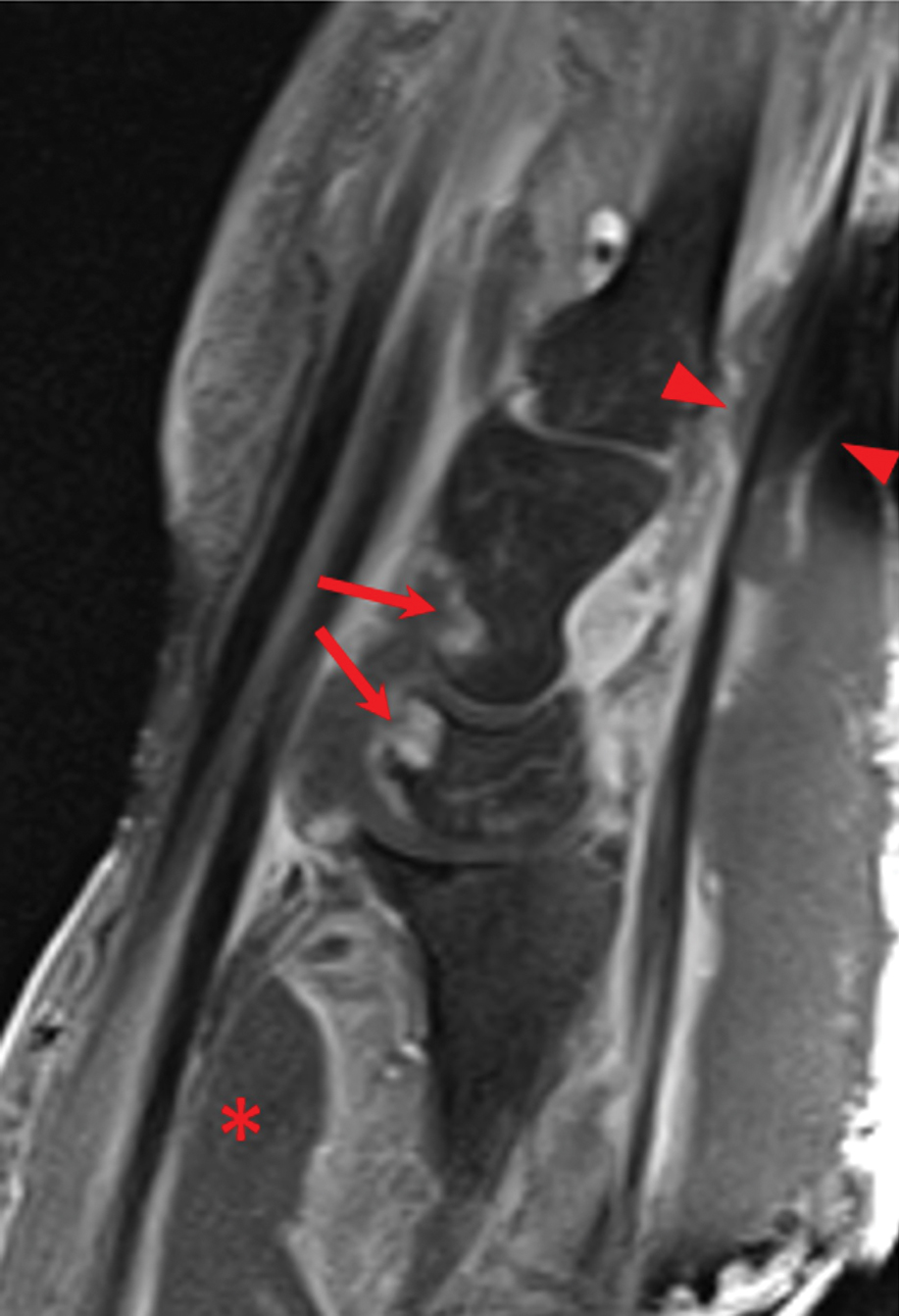

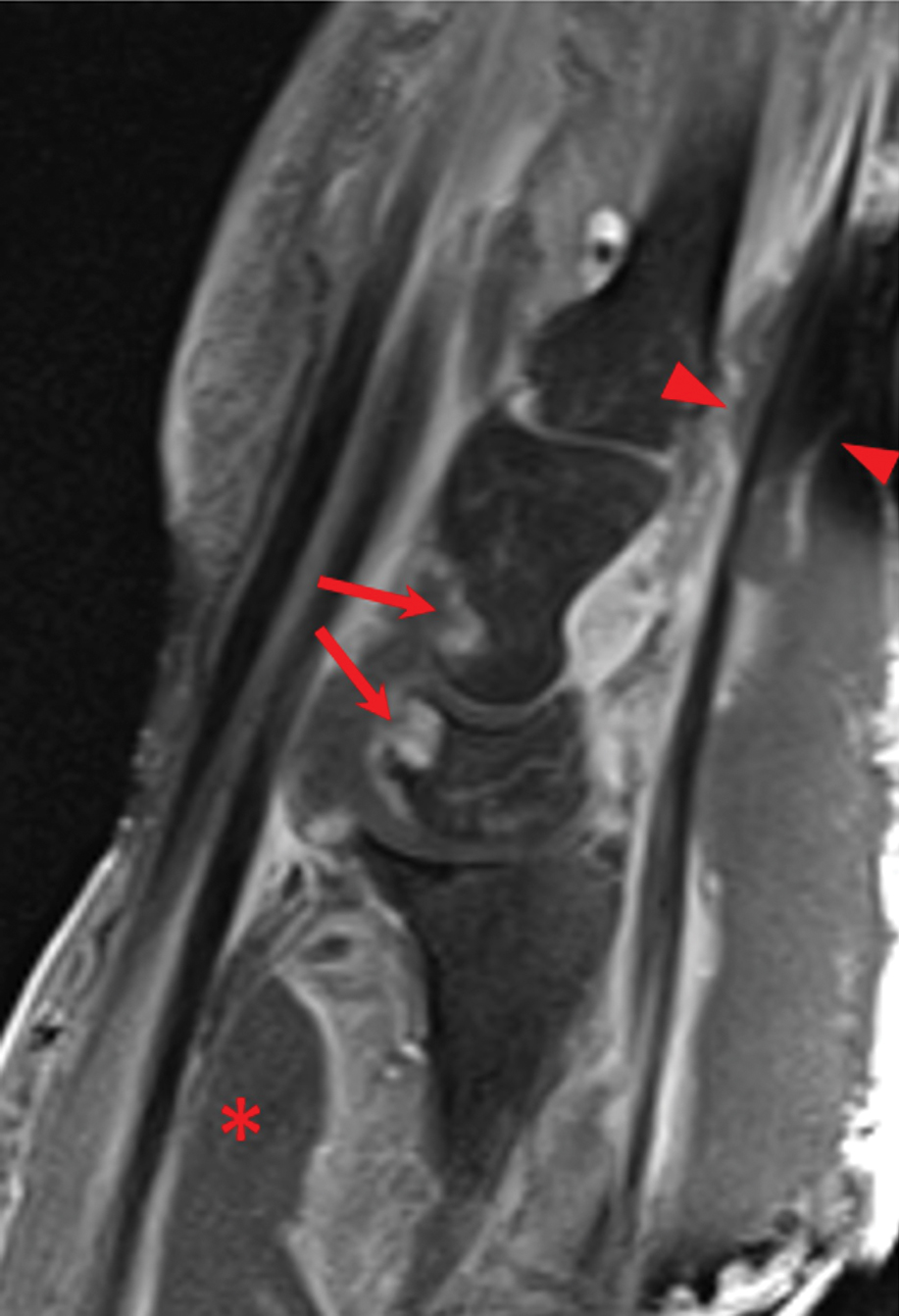

The occurrence of heterotopic ossification (extraskeletal bone formation) is another notable issue in military amputees.27,55-57 Poor prosthetic fit can lead to skin degradation, necessitating further surgery to address mispositioned bone formations. Orthopedic monitoring supplemented by appropriate imaging studies can benefit postamputation patients by detecting and preventing heterotopic ossification in its early stages.

Dermatologic issues, especially among lower limb amputees, are noteworthy, with a substantial percentage experiencing complications related to socket prosthetics, such as heat, sweating, sores, and skin irritation. Up to 41% of patients are seen regularly for a secondary skin disorder following amputation.58 As one might expect, persistent wounds, blisters, ulcers, and abscesses are some of the most typical cutaneous abnormalities affecting residual limbs with prostheses.27,58 More rare skin conditions also are documented in residual limbs, including cutaneous granuloma, verrucous carcinoma, bullous pemphigoid, and angiodermatitis.27,59-61

Treatments offered in the dermatology clinic often are similar to patients who have not had an amputation. For instance, hyperhidrosis can be treated with prescription antiperspirant, topical aluminum chloride, topical glycopyrronium, botulinum toxin, and iontophoresis, which can greatly decrease skin irritation and malodor. Subcutaneous neurotoxins such as botulinum toxin are especially useful for hyperhidrosis following amputation because a single treatment can last 3 to 6 months, whereas topicals must be applied multiple times per day and can be inherently irritating to the skin.27,62 Furthermore, ablative fractional resurfacing lasers also can help stimulate new collagen growth, increase skin mobility on residual limbs, smooth jagged scars, and aid prosthetic fitting.27,63 Perforated prosthetic liners also may be useful to address issues such as excessive sweating, demonstrating improvements in skin health, reduced sweating problems, and potential avoidance of surgical interventions.64

When comorbid skin conditions are at bay, preventive measures for excessive wound healing necessitate early recognition and timely intervention for residual limbs. Preventive techniques encompass the use of silicone gel sheeting, hypoallergenic microporous tape, and intralesional steroid injections.

Psychological Concerns—An overarching issue following amputation is the psychological toll the process imposes on the patient. Psychological concerns, including anxiety and depression, present additional challenges impacting residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance. Chronic wounds are devastating to patients. These patients consistently express feeling ostracized from their community and anxious about unemployment, leaking fluid, or odor from the wound, as well as other social stigmata.62 Depression and anxiety can hinder a patient’s ability to care for their wound and make them more susceptible to the myriad issues that can ensue.

Recent Developments in Wound Healing

Wound healing is ripe for innovation that could assuage ailments that impact patients following amputation. A 2022 study by Abu El Hawa et al65 illustrated advanced progression in wound healing for patients taking statins, even though the statin group had increased age and number of comorbidities compared with patients not taking statins.

Nasseri and Sharifi66 showed the potential of antimicrobial peptides—small proteins with cationic charges and amphipathic structures exhibiting electrostatic interaction with microbial cell membranes—in promoting wound healing, particularly defensins and cathelicidin LL-37.They also discussed innovative delivery systems, such as nanoparticles and electrospun fibrous scaffolds, highlighting their potential as possibly more effective therapeutics than antibiotics, especially in the context of diabetic wound closure.66 Aimed at increased angiogenesis in the proliferative phase, there is evidence that N-acetylcysteine can increase amputation stump perfusion with the goal of better long-term wound healing and more efficient scar formation.67

Stem cell therapy, particularly employing cells from the human amniotic membrane, represents an auspicious avenue for antifibrotic treatment. Amniotic epithelial cells and amniotic mesenchymal cells, with their self-renewal and multilineage differentiation capabilities, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties.4,5 A study by Dong et al68 aimed to assess the efficacy of cell therapy, particularly differentiated progenitor cell–based graft transplantation or autologous stem cell injection, in treating refractory skin injuries such as nonrevascularizable critical limb ischemic ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and diabetic lower limb ulcers. The findings demonstrated cell therapy effectively reduced the size of ulcers, improved wound closure rates, and decreased major amputation rates compared with standard therapy. Of note, cell therapy had limited impact on alleviating pain in patients with critical limb ischemia-related cutaneous ulcers.68

Final Thoughts

Wound care following amputation is a multidisciplinary endeavor, necessitating collaboration between many health care professionals. Dermatologists play a crucial role in providing routine care as well as addressing wound healing and related skin issues among amputation patients. As the field progresses, dermatologists are well positioned to make notable contributions and ensure enhanced outcomes, resulting in a better quality of life for patients facing the challenges of limb amputation and prosthetic use.

- Brockes JP, Kumar A. Comparative aspects of animal regeneration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:525-549. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175336

- Eming SA, Hammerschmidt M, Krieg T, et al. Interrelation of immunity and tissue repair or regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:517-527. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.04.009

- Eming SA. Evolution of immune pathways in regeneration and repair: recent concepts and translational perspectives. Semin Immunol. 2014;26:275-276. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.001

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JJ, Schaffer JV, et al. Dermatology. 4th edition. Elsevier; 2018.

- Wang PH, Huang BS, Horng HC, et al. Wound healing. J Chin Med Assoc JCMA. 2018;81:94-101. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2017.11.002

- Velnar T, Bailey T, Smrkolj V. The wound healing process: an overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:1528-1542. doi:10.1177/147323000903700531

- Gurtner GC, Werner S, Barrandon Y, et al. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453:314-321. doi:10.1038/nature07039

- Eming SA, Martin P, Tomic-Canic M. Wound repair and regeneration: mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:265sr6. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3009337

- Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, et al. Regulation of angiogenesis: wound healing as a model. Prog Histochem Cytochem. 2007;42:115-170. doi:10.1016/j.proghi.2007.06.001

- Janis JE, Harrison B. Wound healing: part I. basic science. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3 suppl):9S-17S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002773

- Profyris C, Tziotzios C, Do Vale I. Cutaneous scarring: pathophysiology, molecular mechanisms, and scar reduction therapeutics. part I: the molecular basis of scar formation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:1-10; quiz 11-12. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.05.055

- Kwan P, Ding J, Tredget EE. MicroRNA 181b regulates decorin production by dermal fibroblasts and may be a potential therapy for hypertrophic scar. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123054. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123054

- Ben W, Yang Y, Yuan J, et al. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 modulates the expression of host microRNAs in cervical cancer. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;54:364-370. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2014.06.007

- Yu EH, Tu HF, Wu CH, et al. MicroRNA-21 promotes perineural invasion and impacts survival in patients with oral carcinoma. J Chin Med Assoc JCMA. 2017;80:383-388. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2017.01.003

- Wen KC, Sung PL, Yen MS, et al. MicroRNAs regulate several functions of normal tissues and malignancies. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52:465-469. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.10.002

- Babalola O, Mamalis A, Lev-Tov H, et al. The role of microRNAs in skin fibrosis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2013;305:763-776. doi:10.1007/s00403-013-1410-1

- Hofer M, Hoferová Z, Falk M. Pharmacological modulation of radiation damage. does it exist a chance for other substances than hematopoietic growth factors and cytokines? Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1385. doi:10.3390/ijms18071385

- Darby IA, Weller CD. Aspirin treatment for chronic wounds: potential beneficial and inhibitory effects. Wound Repair Regen. 2017;25:7-12. doi:10.1111/wrr.12502

- Khalid KA, Nawi AFM, Zulkifli N, et al. Aging and wound healing of the skin: a review of clinical and pathophysiological hallmarks. Life. 2022;12:2142. doi:10.3390/life12122142

- Peacock HM, Gilbert EAB, Vickaryous MK. Scar‐free cutaneous wound healing in the leopard gecko, Eublepharis macularius. J Anat. 2015;227:596-610. doi:10.1111/joa.12368

- Delorme SL, Lungu IM, Vickaryous MK. Scar‐free wound healing and regeneration following tail loss in the leopard gecko, Eublepharis macularius. Anat Rec. 2012;295:1575-1595. doi:10.1002/ar.22490

- Brunauer R, Xia IG, Asrar SN, et al. Aging delays epimorphic regeneration in mice. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2021;76:1726-1733. doi:10.1093/gerona/glab131

- Dolan CP, Yang TJ, Zimmel K, et al. Epimorphic regeneration of the mouse digit tip is finite. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:62. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02741-2

- Simkin J, Han M, Yu L, et al. The mouse digit tip: from wound healing to regeneration. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2013;1037:419-435. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-505-7_24

- Ziegler-Graham K, MacKenzie EJ, Ephraim PL, et al. Estimating the prevalence of limb loss in the United States: 2005 to 2050. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:422-429. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.11.005

- Dudek NL, Marks MB, Marshall SC, et al. Dermatologic conditions associated with use of a lower-extremity prosthesis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:659-663. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2004.09.003

- Lannan FM, Meyerle JH. The dermatologist’s role in amputee skin care. Cutis. 2019;103:86-90.

- Dougherty AL, Mohrle CR, Galarneau MR, et al. Battlefield extremity injuries in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Injury. 2009;40:772-777. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.02.014

- Epstein RA, Heinemann AW, McFarland LV. Quality of life for veterans and servicemembers with major traumatic limb loss from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47:373-385. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.03.0023

- Pinzur MS, Gold J, Schwartz D, et al. Energy demands for walking in dysvascular amputees as related to the level of amputation. Orthopedics. 1992;15:1033-1036; discussion 1036-1037. doi:10.3928/0147-7447-19920901-07

- Robinson V, Sansam K, Hirst L, et al. Major lower limb amputation–what, why and how to achieve the best results. Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:276-285. doi:10.1016/j.mporth.2010.03.017

- Lu S, Wang C, Zhong W, et al. Amputation stump revision using a free sural neurocutaneous perforator flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:83-87. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000211

- Kim SW, Jeon SB, Hwang KT, et al. Coverage of amputation stumps using a latissimus dorsi flap with a serratus anterior muscle flap: a comparative study. Ann Plast Surg. 2016;76:88-93. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000000220

- Pavey GJ, Formby PM, Hoyt BW, et al. Intrawound antibiotic powder decreases frequency of deep infection and severity of heterotopic ossification in combat lower extremity amputations. Clin Orthop. 2019;477:802-810. doi:10.1007/s11999.0000000000000090

- Dunkel N, Belaieff W, Assal M, et al. Wound dehiscence and stump infection after lower limb amputation: risk factors and association with antibiotic use. J Orthop Sci Off J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 2012;17:588-594. doi:10.1007/s00776-012-0245-5

- Rubin G, Orbach H, Rinott M, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics in treatment of fingertip amputation: a randomized prospective trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:645-647. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.02.002

- Azarbal AF, Harris S, Mitchell EL, et al. Nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization is associated with increased wound occurrence after major lower extremity amputation. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:401-405. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2015.02.052

- Kwasniewski M, Mitchel D. Post amputation skin and wound care. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2022;33:857-870. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2022.06.010

- Chang H, Maldonado TS, Rockman CB, et al. Closed incision negative pressure wound therapy may decrease wound complications in major lower extremity amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73:1041-1047. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.07.061

- Kalliainen LK, Gordillo GM, Schlanger R, et al. Topical oxygen as an adjunct to wound healing: a clinical case series. Pathophysiol Off J Int Soc Pathophysiol. 2003;9:81-87. doi:10.1016/s0928-4680(02)00079-2

- Reichmann JP, Stevens PM, Rheinstein J, et al. Removable rigid dressings for postoperative management of transtibial amputations: a review of published evidence. PM R. 2018;10:516-523. doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.10.002

- MacLean N, Fick GH. The effect of semirigid dressings on below-knee amputations. Phys Ther. 1994;74:668-673. doi:10.1093/ptj/74.7.668

- Koonalinthip N, Sukthongsa A, Janchai S. Comparison of removable rigid dressing and elastic bandage for residual limb maturation in transtibial amputees: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:1683-1688. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2020.05.009

- Taylor L, Cavenett S, Stepien JM, et al. Removable rigid dressings: a retrospective case-note audit to determine the validity of post-amputation application. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2008;32:223-230. doi:10.1080/03093640802016795

- Sumpio B, Shine SR, Mahler D, et al. A comparison of immediate postoperative rigid and soft dressings for below-knee amputations. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:774-780. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.03.007

- van Velzen AD, Nederhand MJ, Emmelot CH, et al. Early treatment of trans-tibial amputees: retrospective analysis of early fitting and elastic bandaging. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2005;29:3-12. doi:10.1080/17461550500069588

- Chin T, Toda M. Results of prosthetic rehabilitation on managing transtibial vascular amputation with silicone liner after wound closure. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:957-967. doi:10.1177/0300060516647554

- Hoskins RD, Sutton EE, Kinor D, et al. Using vacuum-assisted suspension to manage residual limb wounds in persons with transtibial amputation: a case series. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2014;38:68-74. doi:10.1177/0309364613487547

- Johannesson A, Larsson GU, Oberg T, et al. Comparison of vacuum-formed removable rigid dressing with conventional rigid dressing after transtibial amputation: similar outcome in a randomized controlled trial involving 27 patients. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:361-369. doi:10.1080/17453670710015265

- Alsancak S, Köse SK, Altınkaynak H. Effect of elastic bandaging and prosthesis on the decrease in stump volume. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2011;45:14-22. doi:10.3944/AOTT.2011.2365

- Than MP, Smith RA, Hammond C, et al. Keratin-based wound care products for treatment of resistant vascular wounds. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2012;5:31-35.

- Gurtner GC, Garcia AD, Bakewell K, et al. A retrospective matched‐cohort study of 3994 lower extremity wounds of multiple etiologies across 644 institutions comparing a bioactive human skin allograft, TheraSkin, plus standard of care, to standard of care alone. Int Wound J. 2020;17:55-64. doi:10.1111/iwj.13231

- Buikema KES, Meyerle JH. Amputation stump: privileged harbor for infections, tumors, and immune disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:670-677. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.04.015

- Yang NB, Garza LA, Foote CE, et al. High prevalence of stump dermatoses 38 years or more after amputation. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1283-1286. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2012.3004

- Potter BK, Burns TC, Lacap AP, et al. Heterotopic ossification following traumatic and combat-related amputations. Prevalence, risk factors, and preliminary results of excision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:476-486. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00412

- Edwards DS, Kuhn KM, Potter BK, et al. Heterotopic ossification: a review of current understanding, treatment, and future. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30(suppl 3):S27-S30. doi:10.1097/BOT.0000000000000666

- Tintle SM, Shawen SB, Forsberg JA, et al. Reoperation after combat-related major lower extremity amputations. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28:232-237. doi:10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182a53130

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Turan H, Bas¸kan EB, Adim SB, et al. Acroangiodermatitis in a below-knee amputation stump. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:560-561. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04037.x

- Lin CH, Ma H, Chung MT, et al. Granulomatous cutaneous lesions associated with risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in an amputated upper limb. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:75-78. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04906.x

- Schwartz RA, Bagley MP, Janniger CK, et al. Verrucous carcinoma of a leg amputation stump. Dermatologica. 1991;182:193-195. doi:10.1159/000247782

- Campanati A, Diotallevi F, Radi G, et al. Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin B in focal hyperhidrosis: a narrative review. Toxins. 2023;15:147. doi:10.3390/toxins15020147

- Anderson RR, Donelan MB, Hivnor C, et al. Laser treatment of traumatic scars with an emphasis on ablative fractional laser resurfacing: consensus report. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:187-193. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7761

- McGrath M, McCarthy J, Gallego A, et al. The influence of perforated prosthetic liners on residual limb wound healing: a case report. Can Prosthet Orthot J. 2019;2:32723. doi:10.33137/cpoj.v2i1.32723

- Abu El Hawa AA, Klein D, Bekeny JC, et al. The impact of statins on wound healing: an ally in treating the highly comorbid patient. J Wound Care. 2022;31(suppl 2):S36-S41. doi:10.12968/jowc.2022.31.Sup2.S36

- Nasseri S, Sharifi M. Therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides for wound healing. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2022;28:38. doi:10.1007/s10989-021-10350-5

- Lee JV, Engel C, Tay S, et al. N-Acetyl-Cysteine treatment after lower extremity amputation improves areas of perfusion defect and wound healing outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73:39-40. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2020.12.025

- Dong Y, Yang Q, Sun X. Comprehensive analysis of cell therapy on chronic skin wound healing: a meta-analysis. Hum Gene Ther. 2021;32:787-795. doi:10.1089/hum.2020.275

Restoring skin integrity and balance after injury is vital for survival, serving as a crucial defense mechanism against potential infections by preventing the entry of harmful pathogens. Moreover, proper healing is essential for restoring normal tissue function, allowing damaged tissues to repair and, in an ideal scenario, regenerate. Timely healing helps reduce the risk for complications, such as chronic wounds, which could lead to more severe issues if left untreated. Additionally, pain relief often is associated with effective wound healing as inflammatory responses diminish during the repair process.

The immune system plays a pivotal role in wound healing, influencing various repair mechanisms and ultimately determining the extent of scarring. Although inflammation is present throughout the repair response, recent studies have challenged the conventional belief of an inverse correlation between the intensity of inflammation and regenerative capacity. Inflammatory signals were found to be crucial for timely repair and fundamental processes in regeneration, possibly presenting a paradigm shift in the understanding of immunology.1-4 The complexities of wound healing are exemplified when evaluating and treating postamputation wounds. To address such a task, one needs a firm understanding of the science behind healing wounds and what can go wrong along the way.

Phases of Wound Healing

Wound healing is a complex process that involves a series of sequential yet overlapping phases, including hemostasis/inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.

Hemostasis/Inflammation—The initial stage of wound healing involves hemostasis, in which the primary objective is to prevent blood loss and initiate inflammation. Platelets arrive at the wound site, forming a provisional clot that is crucial for subsequent healing phases.4-6 Platelets halt bleeding as well as act as a medium for cell migration and adhesion; they also are a source of growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines that herald the inflammatory response.4-7

Inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of immune cells, particularly neutrophils and macrophages. Neutrophils act as the first line of defense, clearing debris and preventing infection. Macrophages follow, phagocytizing apoptotic cells and releasing growth factors such as tumor necrosis factor α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloprotease 9, which stimulate the next phase.4-6,8 Typically, the hemostasis and inflammatory phase starts approximately 6 to 8 hours after wound origin and lasts 3 to 4 days.4,6,7

Proliferation—Following hemostasis and inflammation, the wound transitions into the proliferation phase, which is marked by the development of granulation tissue—a dynamic amalgamation of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells.1,4-8 Fibroblasts play a central role in synthesizing collagen, the primary structural protein in connective tissue. They also orchestrate synthesis of vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrin, and tenascin.4-6,8 Simultaneously, angiogenesis takes place, involving the creation of new blood vessels to supply essential nutrients and oxygen to the healing tissue.4,7,9 Growth factors such as transforming growth factor β and vascular endothelial growth factor coordinate cellular activities and foster tissue repair.4-6,8 The proliferation phase extends over days to weeks, laying the groundwork for subsequent tissue restructuring.

Remodeling—The final stage of wound healing is remodeling, an extended process that may persist for several months or, in some cases, years. Throughout this phase, the initially deposited collagen, predominantly type III collagen, undergoes transformation into mature type I collagen.4-6,8 This transformation is critical for reinstating the tissue’s strength and functionality. The balance between collagen synthesis and degradation is delicate, regulated by matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitors of metalloproteinases.4-8 Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and other cells coordinate this intricate process of tissue reorganization.4-7

The eventual outcome of the remodeling phase determines the appearance and functionality of the healed tissue. Any disruption in this phase can lead to complications, such as chronic wounds and hypertrophic scars/keloids.4-6 These abnormal healing processes are characterized by localized inflammation, heightened fibroblast function, and excessive accumulation of the extracellular matrix.4-8

Molecular Mechanisms

Comprehensive investigations—both in vivo and in vitro—have explored the intricate molecular mechanisms involved in heightened wound healing. Transforming growth factor β takes center stage as a crucial factor, prompting the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and contributing to the deposition of extracellular matrix.2,4-8,10 Transforming growth factor β activates non-Smad signaling pathways, such as MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), influencing processes associated with fibrosis.5,11 Furthermore, microRNAs play a pivotal role in posttranscriptional regulation, influencing both transforming growth factor β signaling and fibroblast behavior.12-16

The involvement of prostaglandins is crucial in wound healing. Prostaglandin E2 plays a notable role and is positively correlated with the rate of wound healing.5 The cyclooxygenase pathway, pivotal for prostaglandin synthesis, becomes a target for inflammation control.4,5,10 Although aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs commonly are employed, their impact on wound healing remains controversial, as inhibition of cyclooxygenase may disrupt normal repair processes.5,17,18

Wound healing exhibits variations depending on age. Fetal skin regeneration is marked by the restoration of normal dermal architecture, including adnexal structures, nerves, vessels, and muscle.4-6 The distinctive characteristics of fetal wound healing include a unique profile of growth factors, a diminished inflammatory response, reduced biomechanical stress, and a distinct extracellular matrix composition.19 These factors contribute to a lower propensity for scar formation compared to the healing processes observed in adults. Fetal and adult wound healing differ fundamentally in their extracellular matrix composition, inflammatory cells, and cytokine levels.4-6,19 Adult wounds feature myofibroblasts, which are absent in fetal wounds, contributing to heightened mechanical tension.5 Delving deeper into the biochemical basis of fetal wound healing holds promise for mitigating scar formation in adults.

Takeaways From Other Species

Much of the biochemical knowledge of wound healing, especially regenerative wound healing, is known from other species. Geckos provide a unique model for studying regenerative repair in tails and nonregenerative healing in limbs after amputation. Scar-free wound healing is characterized by rapid wound closure, delayed blood vessel development, and collagen deposition, which contrasts with the hypervascular granulation tissue seen in scarring wounds.20 Scar-free wound healing and regeneration are intrinsic properties of the lizard tail and are unaffected by the location or method of detachment.21

Compared to amphibians with extraordinary regenerative capacity, data suggest the lack of regenerative capacity in mammals may come from a desynchronization of the fine-tuned interplay of progenitor cells such as blastema and differentiated cells.22,23 In mice, the response to amputation is specific to the level: cutting through the distal third of the terminal phalanx elicits a regeneration response, yielding a new digit tip resembling the lost one, while an amputation through the distal third of the intermediate phalanx triggers a wound healing and scarring response.24

Wound Healing Following Limb Amputation

Limb amputation represents a profound change in an individual’s life, impacting daily activities and overall well-being. There are many causes of amputation, but the most common include cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and trauma.25-27 Trauma represents a relatively common cause within the US Military due to the overall young population as well as inherent risks of uniformed service.25,27 Advances in protective gear and combat casualty care have led to an increased number of individuals surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation, particularly among younger service members, with a subgroup experiencing multiple amputations.27-29

Numerous factors play a crucial role in the healing and function of postamputation wounds. The level of amputation is a key determinant influencing both functional outcomes and the healing process. Achieving a balance between preserving function and removing damaged tissue is essential. A study investigating cardiac function and oxygen consumption in 25 patients with peripheral vascular disease found higher-level amputations resulted in decreased walking speed and cadence, along with increased oxygen consumption per meter walked.30

Selecting the appropriate amputation level is vital to optimize functional outcomes without compromising wound healing. Successful prosthetic limb fitting depends largely on the length of the residual stump to support the body load and suspend the prosthesis. For long bone amputations, maintaining at least 12-cm clearance above the knee joint in transfemoral amputees and 10-cm below the knee joint in transtibial amputees is critical for maximizing functional outcomes.31

Surgical technique also is paramount. The goal is to minimize the risk for pressure ulcers by avoiding bony spurs and muscle imbalances. Shaping the muscle and residual limb is essential for proper prosthesis fitting. Attention to neurovascular structures, such as burying nerve ends to prevent neuropathic pain during prosthesis wear, is crucial.32 In extremity amputations, surgeons often resort to free flap transfer techniques for stump reconstruction. In a study of 31 patients with severe lower extremity injuries undergoing various amputations, the use of latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps, alone or in combination with serratus anterior muscle flaps, resulted in fewer instances of deep ulceration and allowed for earlier prosthesis wear.33

Addressing Barriers to Wound Healing

Multiple barriers to successful wound healing are encountered in the amputee population. Amputations from trauma have a less-controlled initiation, which carries with it a higher risk for infection, poor wound healing, and other complications.

Infection—Infection often is one of the first hurdles encountered in postamputation wound healing. Critical first steps in infection prevention include thorough cleaning of soiled traumatic wounds and appropriate tissue debridement coupled with scrupulous sterile technique and postoperative monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection.

In a retrospective study of 223 combat-related major lower extremity amputations (initial and revision) between 2009 and 2015, the use of intrawound antibiotic powder at the time of closure demonstrated a 13% absolute risk reduction in deep infection rates, which was particularly notable in revision amputations, with a number needed to treat of 8 for initial amputations and 4 for revision amputations on previously infected limbs.34 Intra-operative antibiotic powder may represent a cheap and easy consideration for this special population of amputees. Postamputation antibiotic prophylaxis for infection prevention is an area of controversy. For nontraumatic infections, data suggest antibiotic prophylaxis may not decrease infection rates in these patients.35,36

Interestingly, a study by Azarbal et al37 aimed to investigate the correlation between nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization and other patient factors with wound occurrence following major lower extremity amputation. The study found MRSA colonization was associated with higher rates of overall wound occurrence as well as wound occurrence due to wound infection. These data suggest nasal MRSA eradication may improve postoperative wound outcomes after major lower extremity amputation.37

Dressing Choice—The dressing chosen for a residual limb also is of paramount importance following amputation. The personalized and dynamic management of postamputation wounds and skin involves achieving optimal healing through a dressing that sustains appropriate moisture levels, addresses edema, helps prevent contractures, and safeguards the limb.38 From the start, using negative pressure wound dressings after surgical amputation can decrease wound-related complications.39

Topical oxygen therapy following amputation also shows promise. In a retrospective case series by Kalliainen et al,40 topical oxygen therapy applied to 58 wounds in 32 patients over 9 months demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting wound healing, with 38 wounds (66%) healing completely with the use of topical oxygen. Minimal complications and no detrimental effects were observed.40

Current recommendations suggest that non–weight-bearing removable rigid dressings are the superior postoperative management for transtibial amputations compared to soft dressings, offering benefits such as faster healing, reduced limb edema, earlier ambulation, preparatory shaping for prosthetic use, and prevention of knee flexion contractures.41-46 Similarly, adding a silicone liner following amputation significantly reduced the duration of prosthetic rehabilitation compared with a conventional soft dressing program in one study (P<.05).47

Specifically targeting wound edema, a case series by Hoskins et al48 investigated the impact of prostheses with vacuum-assisted suspension on the size of residual limb wounds in individuals with transtibial amputation. Well-fitting sockets with vacuum-assisted suspension did not impede wound healing, and the results suggest the potential for continued prosthesis use during the healing process.48 However, a study by Johannesson et al49 compared the outcomes of transtibial amputation patients using a vacuum-formed rigid dressing and a conventional rigid plaster dressing, finding no significant differences in wound healing, time to prosthetic fitting, or functional outcomes with the prosthesis between the 2 groups. When comparing elastic bandaging, pneumatic prosthesis, and temporary prosthesis on postoperative stump management, temporary prosthesis led to a decrease in stump volume, quicker transition to a permanent prosthesis, and improved quality of life compared with elastic bandaging and pneumatic prosthetics.50

The type of material in dressings may contribute to utility in amputation wounds. Keratin-based wound dressings show promise for wound healing, especially in recalcitrant vascular wounds.51 There also are numerous proprietary wound dressings available for patients, at least one of which has particularly thorough data. In a retrospective study of more than 2 million lower extremity wounds across 644 institutions, a proprietary bioactive human skin allograft (TheraSkin [LifeNet Health]) demonstrated higher healing rates, greater percentage area reductions, lower amputations, reduced recidivism, higher treatment completion, and fewer medical transfers compared with standard of care alone.52

Postamputation Dermatologic Concerns

After the postamputation wound heals, a notable concern is the prevalence of skin diseases affecting residual limbs. The stump site in amputees, marked by a delicate cutaneous landscape vulnerable to skin diseases, faces challenges arising from amputation-induced damage to various structures.53

When integrated into a prosthesis socket, the altered skin must acclimate to a humid environment and endure forces for which it is not well suited, especially during movement.53 Amputation remarkably alters normal tissue perfusion, which can lead to aberrant blood and lymphatic circulation in residual limbs.27,53 This compromised skin, often associated with a history of vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or malignancy, becomes immunocompromised, heightening the risk for dermatologic issues such as inflammation, infection, and malignancies.53 Unlike the resilient volar skin on palms and soles, stump skin lacks adaptation to withstand the compressive forces generated during ambulation, sometimes leading to skin disease and pain that result in abandonment of the prosthesis.53,54 Mechanical forces on the skin, especially in active patients eager to resume pre-injury lifestyles, contribute to skin breakdown. The dynamic nature of the residual limb, including muscle atrophy, gait changes, and weight fluctuations, complicates the prosthetic fitting process. Prosthesis abandonment remains a challenge, despite modern technologic advancements.

The occurrence of heterotopic ossification (extraskeletal bone formation) is another notable issue in military amputees.27,55-57 Poor prosthetic fit can lead to skin degradation, necessitating further surgery to address mispositioned bone formations. Orthopedic monitoring supplemented by appropriate imaging studies can benefit postamputation patients by detecting and preventing heterotopic ossification in its early stages.

Dermatologic issues, especially among lower limb amputees, are noteworthy, with a substantial percentage experiencing complications related to socket prosthetics, such as heat, sweating, sores, and skin irritation. Up to 41% of patients are seen regularly for a secondary skin disorder following amputation.58 As one might expect, persistent wounds, blisters, ulcers, and abscesses are some of the most typical cutaneous abnormalities affecting residual limbs with prostheses.27,58 More rare skin conditions also are documented in residual limbs, including cutaneous granuloma, verrucous carcinoma, bullous pemphigoid, and angiodermatitis.27,59-61

Treatments offered in the dermatology clinic often are similar to patients who have not had an amputation. For instance, hyperhidrosis can be treated with prescription antiperspirant, topical aluminum chloride, topical glycopyrronium, botulinum toxin, and iontophoresis, which can greatly decrease skin irritation and malodor. Subcutaneous neurotoxins such as botulinum toxin are especially useful for hyperhidrosis following amputation because a single treatment can last 3 to 6 months, whereas topicals must be applied multiple times per day and can be inherently irritating to the skin.27,62 Furthermore, ablative fractional resurfacing lasers also can help stimulate new collagen growth, increase skin mobility on residual limbs, smooth jagged scars, and aid prosthetic fitting.27,63 Perforated prosthetic liners also may be useful to address issues such as excessive sweating, demonstrating improvements in skin health, reduced sweating problems, and potential avoidance of surgical interventions.64

When comorbid skin conditions are at bay, preventive measures for excessive wound healing necessitate early recognition and timely intervention for residual limbs. Preventive techniques encompass the use of silicone gel sheeting, hypoallergenic microporous tape, and intralesional steroid injections.

Psychological Concerns—An overarching issue following amputation is the psychological toll the process imposes on the patient. Psychological concerns, including anxiety and depression, present additional challenges impacting residual limb hygiene and prosthetic maintenance. Chronic wounds are devastating to patients. These patients consistently express feeling ostracized from their community and anxious about unemployment, leaking fluid, or odor from the wound, as well as other social stigmata.62 Depression and anxiety can hinder a patient’s ability to care for their wound and make them more susceptible to the myriad issues that can ensue.

Recent Developments in Wound Healing

Wound healing is ripe for innovation that could assuage ailments that impact patients following amputation. A 2022 study by Abu El Hawa et al65 illustrated advanced progression in wound healing for patients taking statins, even though the statin group had increased age and number of comorbidities compared with patients not taking statins.

Nasseri and Sharifi66 showed the potential of antimicrobial peptides—small proteins with cationic charges and amphipathic structures exhibiting electrostatic interaction with microbial cell membranes—in promoting wound healing, particularly defensins and cathelicidin LL-37.They also discussed innovative delivery systems, such as nanoparticles and electrospun fibrous scaffolds, highlighting their potential as possibly more effective therapeutics than antibiotics, especially in the context of diabetic wound closure.66 Aimed at increased angiogenesis in the proliferative phase, there is evidence that N-acetylcysteine can increase amputation stump perfusion with the goal of better long-term wound healing and more efficient scar formation.67

Stem cell therapy, particularly employing cells from the human amniotic membrane, represents an auspicious avenue for antifibrotic treatment. Amniotic epithelial cells and amniotic mesenchymal cells, with their self-renewal and multilineage differentiation capabilities, exhibit anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties.4,5 A study by Dong et al68 aimed to assess the efficacy of cell therapy, particularly differentiated progenitor cell–based graft transplantation or autologous stem cell injection, in treating refractory skin injuries such as nonrevascularizable critical limb ischemic ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and diabetic lower limb ulcers. The findings demonstrated cell therapy effectively reduced the size of ulcers, improved wound closure rates, and decreased major amputation rates compared with standard therapy. Of note, cell therapy had limited impact on alleviating pain in patients with critical limb ischemia-related cutaneous ulcers.68

Final Thoughts

Wound care following amputation is a multidisciplinary endeavor, necessitating collaboration between many health care professionals. Dermatologists play a crucial role in providing routine care as well as addressing wound healing and related skin issues among amputation patients. As the field progresses, dermatologists are well positioned to make notable contributions and ensure enhanced outcomes, resulting in a better quality of life for patients facing the challenges of limb amputation and prosthetic use.

Restoring skin integrity and balance after injury is vital for survival, serving as a crucial defense mechanism against potential infections by preventing the entry of harmful pathogens. Moreover, proper healing is essential for restoring normal tissue function, allowing damaged tissues to repair and, in an ideal scenario, regenerate. Timely healing helps reduce the risk for complications, such as chronic wounds, which could lead to more severe issues if left untreated. Additionally, pain relief often is associated with effective wound healing as inflammatory responses diminish during the repair process.

The immune system plays a pivotal role in wound healing, influencing various repair mechanisms and ultimately determining the extent of scarring. Although inflammation is present throughout the repair response, recent studies have challenged the conventional belief of an inverse correlation between the intensity of inflammation and regenerative capacity. Inflammatory signals were found to be crucial for timely repair and fundamental processes in regeneration, possibly presenting a paradigm shift in the understanding of immunology.1-4 The complexities of wound healing are exemplified when evaluating and treating postamputation wounds. To address such a task, one needs a firm understanding of the science behind healing wounds and what can go wrong along the way.

Phases of Wound Healing

Wound healing is a complex process that involves a series of sequential yet overlapping phases, including hemostasis/inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling.

Hemostasis/Inflammation—The initial stage of wound healing involves hemostasis, in which the primary objective is to prevent blood loss and initiate inflammation. Platelets arrive at the wound site, forming a provisional clot that is crucial for subsequent healing phases.4-6 Platelets halt bleeding as well as act as a medium for cell migration and adhesion; they also are a source of growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines that herald the inflammatory response.4-7

Inflammation is characterized by the infiltration of immune cells, particularly neutrophils and macrophages. Neutrophils act as the first line of defense, clearing debris and preventing infection. Macrophages follow, phagocytizing apoptotic cells and releasing growth factors such as tumor necrosis factor α, vascular endothelial growth factor, and matrix metalloprotease 9, which stimulate the next phase.4-6,8 Typically, the hemostasis and inflammatory phase starts approximately 6 to 8 hours after wound origin and lasts 3 to 4 days.4,6,7

Proliferation—Following hemostasis and inflammation, the wound transitions into the proliferation phase, which is marked by the development of granulation tissue—a dynamic amalgamation of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells.1,4-8 Fibroblasts play a central role in synthesizing collagen, the primary structural protein in connective tissue. They also orchestrate synthesis of vitronectin, fibronectin, fibrin, and tenascin.4-6,8 Simultaneously, angiogenesis takes place, involving the creation of new blood vessels to supply essential nutrients and oxygen to the healing tissue.4,7,9 Growth factors such as transforming growth factor β and vascular endothelial growth factor coordinate cellular activities and foster tissue repair.4-6,8 The proliferation phase extends over days to weeks, laying the groundwork for subsequent tissue restructuring.

Remodeling—The final stage of wound healing is remodeling, an extended process that may persist for several months or, in some cases, years. Throughout this phase, the initially deposited collagen, predominantly type III collagen, undergoes transformation into mature type I collagen.4-6,8 This transformation is critical for reinstating the tissue’s strength and functionality. The balance between collagen synthesis and degradation is delicate, regulated by matrix metalloproteinases and inhibitors of metalloproteinases.4-8 Fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and other cells coordinate this intricate process of tissue reorganization.4-7

The eventual outcome of the remodeling phase determines the appearance and functionality of the healed tissue. Any disruption in this phase can lead to complications, such as chronic wounds and hypertrophic scars/keloids.4-6 These abnormal healing processes are characterized by localized inflammation, heightened fibroblast function, and excessive accumulation of the extracellular matrix.4-8

Molecular Mechanisms

Comprehensive investigations—both in vivo and in vitro—have explored the intricate molecular mechanisms involved in heightened wound healing. Transforming growth factor β takes center stage as a crucial factor, prompting the transformation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts and contributing to the deposition of extracellular matrix.2,4-8,10 Transforming growth factor β activates non-Smad signaling pathways, such as MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), influencing processes associated with fibrosis.5,11 Furthermore, microRNAs play a pivotal role in posttranscriptional regulation, influencing both transforming growth factor β signaling and fibroblast behavior.12-16

The involvement of prostaglandins is crucial in wound healing. Prostaglandin E2 plays a notable role and is positively correlated with the rate of wound healing.5 The cyclooxygenase pathway, pivotal for prostaglandin synthesis, becomes a target for inflammation control.4,5,10 Although aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs commonly are employed, their impact on wound healing remains controversial, as inhibition of cyclooxygenase may disrupt normal repair processes.5,17,18

Wound healing exhibits variations depending on age. Fetal skin regeneration is marked by the restoration of normal dermal architecture, including adnexal structures, nerves, vessels, and muscle.4-6 The distinctive characteristics of fetal wound healing include a unique profile of growth factors, a diminished inflammatory response, reduced biomechanical stress, and a distinct extracellular matrix composition.19 These factors contribute to a lower propensity for scar formation compared to the healing processes observed in adults. Fetal and adult wound healing differ fundamentally in their extracellular matrix composition, inflammatory cells, and cytokine levels.4-6,19 Adult wounds feature myofibroblasts, which are absent in fetal wounds, contributing to heightened mechanical tension.5 Delving deeper into the biochemical basis of fetal wound healing holds promise for mitigating scar formation in adults.

Takeaways From Other Species

Much of the biochemical knowledge of wound healing, especially regenerative wound healing, is known from other species. Geckos provide a unique model for studying regenerative repair in tails and nonregenerative healing in limbs after amputation. Scar-free wound healing is characterized by rapid wound closure, delayed blood vessel development, and collagen deposition, which contrasts with the hypervascular granulation tissue seen in scarring wounds.20 Scar-free wound healing and regeneration are intrinsic properties of the lizard tail and are unaffected by the location or method of detachment.21

Compared to amphibians with extraordinary regenerative capacity, data suggest the lack of regenerative capacity in mammals may come from a desynchronization of the fine-tuned interplay of progenitor cells such as blastema and differentiated cells.22,23 In mice, the response to amputation is specific to the level: cutting through the distal third of the terminal phalanx elicits a regeneration response, yielding a new digit tip resembling the lost one, while an amputation through the distal third of the intermediate phalanx triggers a wound healing and scarring response.24

Wound Healing Following Limb Amputation

Limb amputation represents a profound change in an individual’s life, impacting daily activities and overall well-being. There are many causes of amputation, but the most common include cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and trauma.25-27 Trauma represents a relatively common cause within the US Military due to the overall young population as well as inherent risks of uniformed service.25,27 Advances in protective gear and combat casualty care have led to an increased number of individuals surviving with extremity injuries requiring amputation, particularly among younger service members, with a subgroup experiencing multiple amputations.27-29

Numerous factors play a crucial role in the healing and function of postamputation wounds. The level of amputation is a key determinant influencing both functional outcomes and the healing process. Achieving a balance between preserving function and removing damaged tissue is essential. A study investigating cardiac function and oxygen consumption in 25 patients with peripheral vascular disease found higher-level amputations resulted in decreased walking speed and cadence, along with increased oxygen consumption per meter walked.30

Selecting the appropriate amputation level is vital to optimize functional outcomes without compromising wound healing. Successful prosthetic limb fitting depends largely on the length of the residual stump to support the body load and suspend the prosthesis. For long bone amputations, maintaining at least 12-cm clearance above the knee joint in transfemoral amputees and 10-cm below the knee joint in transtibial amputees is critical for maximizing functional outcomes.31

Surgical technique also is paramount. The goal is to minimize the risk for pressure ulcers by avoiding bony spurs and muscle imbalances. Shaping the muscle and residual limb is essential for proper prosthesis fitting. Attention to neurovascular structures, such as burying nerve ends to prevent neuropathic pain during prosthesis wear, is crucial.32 In extremity amputations, surgeons often resort to free flap transfer techniques for stump reconstruction. In a study of 31 patients with severe lower extremity injuries undergoing various amputations, the use of latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps, alone or in combination with serratus anterior muscle flaps, resulted in fewer instances of deep ulceration and allowed for earlier prosthesis wear.33

Addressing Barriers to Wound Healing

Multiple barriers to successful wound healing are encountered in the amputee population. Amputations from trauma have a less-controlled initiation, which carries with it a higher risk for infection, poor wound healing, and other complications.

Infection—Infection often is one of the first hurdles encountered in postamputation wound healing. Critical first steps in infection prevention include thorough cleaning of soiled traumatic wounds and appropriate tissue debridement coupled with scrupulous sterile technique and postoperative monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection.

In a retrospective study of 223 combat-related major lower extremity amputations (initial and revision) between 2009 and 2015, the use of intrawound antibiotic powder at the time of closure demonstrated a 13% absolute risk reduction in deep infection rates, which was particularly notable in revision amputations, with a number needed to treat of 8 for initial amputations and 4 for revision amputations on previously infected limbs.34 Intra-operative antibiotic powder may represent a cheap and easy consideration for this special population of amputees. Postamputation antibiotic prophylaxis for infection prevention is an area of controversy. For nontraumatic infections, data suggest antibiotic prophylaxis may not decrease infection rates in these patients.35,36

Interestingly, a study by Azarbal et al37 aimed to investigate the correlation between nasal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization and other patient factors with wound occurrence following major lower extremity amputation. The study found MRSA colonization was associated with higher rates of overall wound occurrence as well as wound occurrence due to wound infection. These data suggest nasal MRSA eradication may improve postoperative wound outcomes after major lower extremity amputation.37

Dressing Choice—The dressing chosen for a residual limb also is of paramount importance following amputation. The personalized and dynamic management of postamputation wounds and skin involves achieving optimal healing through a dressing that sustains appropriate moisture levels, addresses edema, helps prevent contractures, and safeguards the limb.38 From the start, using negative pressure wound dressings after surgical amputation can decrease wound-related complications.39

Topical oxygen therapy following amputation also shows promise. In a retrospective case series by Kalliainen et al,40 topical oxygen therapy applied to 58 wounds in 32 patients over 9 months demonstrated positive outcomes in promoting wound healing, with 38 wounds (66%) healing completely with the use of topical oxygen. Minimal complications and no detrimental effects were observed.40

Current recommendations suggest that non–weight-bearing removable rigid dressings are the superior postoperative management for transtibial amputations compared to soft dressings, offering benefits such as faster healing, reduced limb edema, earlier ambulation, preparatory shaping for prosthetic use, and prevention of knee flexion contractures.41-46 Similarly, adding a silicone liner following amputation significantly reduced the duration of prosthetic rehabilitation compared with a conventional soft dressing program in one study (P<.05).47

Specifically targeting wound edema, a case series by Hoskins et al48 investigated the impact of prostheses with vacuum-assisted suspension on the size of residual limb wounds in individuals with transtibial amputation. Well-fitting sockets with vacuum-assisted suspension did not impede wound healing, and the results suggest the potential for continued prosthesis use during the healing process.48 However, a study by Johannesson et al49 compared the outcomes of transtibial amputation patients using a vacuum-formed rigid dressing and a conventional rigid plaster dressing, finding no significant differences in wound healing, time to prosthetic fitting, or functional outcomes with the prosthesis between the 2 groups. When comparing elastic bandaging, pneumatic prosthesis, and temporary prosthesis on postoperative stump management, temporary prosthesis led to a decrease in stump volume, quicker transition to a permanent prosthesis, and improved quality of life compared with elastic bandaging and pneumatic prosthetics.50

The type of material in dressings may contribute to utility in amputation wounds. Keratin-based wound dressings show promise for wound healing, especially in recalcitrant vascular wounds.51 There also are numerous proprietary wound dressings available for patients, at least one of which has particularly thorough data. In a retrospective study of more than 2 million lower extremity wounds across 644 institutions, a proprietary bioactive human skin allograft (TheraSkin [LifeNet Health]) demonstrated higher healing rates, greater percentage area reductions, lower amputations, reduced recidivism, higher treatment completion, and fewer medical transfers compared with standard of care alone.52

Postamputation Dermatologic Concerns

After the postamputation wound heals, a notable concern is the prevalence of skin diseases affecting residual limbs. The stump site in amputees, marked by a delicate cutaneous landscape vulnerable to skin diseases, faces challenges arising from amputation-induced damage to various structures.53

When integrated into a prosthesis socket, the altered skin must acclimate to a humid environment and endure forces for which it is not well suited, especially during movement.53 Amputation remarkably alters normal tissue perfusion, which can lead to aberrant blood and lymphatic circulation in residual limbs.27,53 This compromised skin, often associated with a history of vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, or malignancy, becomes immunocompromised, heightening the risk for dermatologic issues such as inflammation, infection, and malignancies.53 Unlike the resilient volar skin on palms and soles, stump skin lacks adaptation to withstand the compressive forces generated during ambulation, sometimes leading to skin disease and pain that result in abandonment of the prosthesis.53,54 Mechanical forces on the skin, especially in active patients eager to resume pre-injury lifestyles, contribute to skin breakdown. The dynamic nature of the residual limb, including muscle atrophy, gait changes, and weight fluctuations, complicates the prosthetic fitting process. Prosthesis abandonment remains a challenge, despite modern technologic advancements.

The occurrence of heterotopic ossification (extraskeletal bone formation) is another notable issue in military amputees.27,55-57 Poor prosthetic fit can lead to skin degradation, necessitating further surgery to address mispositioned bone formations. Orthopedic monitoring supplemented by appropriate imaging studies can benefit postamputation patients by detecting and preventing heterotopic ossification in its early stages.

Dermatologic issues, especially among lower limb amputees, are noteworthy, with a substantial percentage experiencing complications related to socket prosthetics, such as heat, sweating, sores, and skin irritation. Up to 41% of patients are seen regularly for a secondary skin disorder following amputation.58 As one might expect, persistent wounds, blisters, ulcers, and abscesses are some of the most typical cutaneous abnormalities affecting residual limbs with prostheses.27,58 More rare skin conditions also are documented in residual limbs, including cutaneous granuloma, verrucous carcinoma, bullous pemphigoid, and angiodermatitis.27,59-61

Treatments offered in the dermatology clinic often are similar to patients who have not had an amputation. For instance, hyperhidrosis can be treated with prescription antiperspirant, topical aluminum chloride, topical glycopyrronium, botulinum toxin, and iontophoresis, which can greatly decrease skin irritation and malodor. Subcutaneous neurotoxins such as botulinum toxin are especially useful for hyperhidrosis following amputation because a single treatment can last 3 to 6 months, whereas topicals must be applied multiple times per day and can be inherently irritating to the skin.27,62 Furthermore, ablative fractional resurfacing lasers also can help stimulate new collagen growth, increase skin mobility on residual limbs, smooth jagged scars, and aid prosthetic fitting.27,63 Perforated prosthetic liners also may be useful to address issues such as excessive sweating, demonstrating improvements in skin health, reduced sweating problems, and potential avoidance of surgical interventions.64

When comorbid skin conditions are at bay, preventive measures for excessive wound healing necessitate early recognition and timely intervention for residual limbs. Preventive techniques encompass the use of silicone gel sheeting, hypoallergenic microporous tape, and intralesional steroid injections.