User login

Diabetes Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving options for treating and preventing Type 2 Diabetes in at-risk patients. The Diabetes Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

A quarter of hypertensive Medicare enrollees are nonadherent

Over 26% of Medicare part D enrollees aged 65 years and over are not taking their antihypertensive drugs properly, according to a report published online Sept. 13 in MMWR.

An analysis of 2014 data showed that 4.9 million hypertensive Medicare patients were taking an incorrect dose of their medication or were not taking it at all, reported Matthew Ritchey, DPT of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division for heart disease and stroke prevention, and his associates (MMWR. 2016 Sep 13:65).

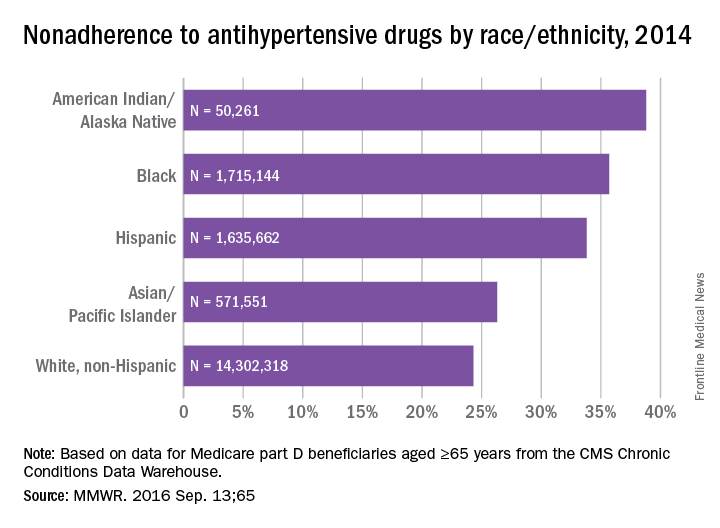

Nonadherence rates varied considerably by race and ethnicity, with American Indians/Alaska Natives the highest at 39%, followed by blacks at 36%, Hispanics at 34%, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 26%, and white non-Hispanics at 24%, the investigators noted.

The analysis included 18.5 million part D beneficiaries who filled two or more antihypertensive prescriptions in the same therapeutic class on different dates within a period of more than 90 days in 2014.

Over 26% of Medicare part D enrollees aged 65 years and over are not taking their antihypertensive drugs properly, according to a report published online Sept. 13 in MMWR.

An analysis of 2014 data showed that 4.9 million hypertensive Medicare patients were taking an incorrect dose of their medication or were not taking it at all, reported Matthew Ritchey, DPT of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division for heart disease and stroke prevention, and his associates (MMWR. 2016 Sep 13:65).

Nonadherence rates varied considerably by race and ethnicity, with American Indians/Alaska Natives the highest at 39%, followed by blacks at 36%, Hispanics at 34%, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 26%, and white non-Hispanics at 24%, the investigators noted.

The analysis included 18.5 million part D beneficiaries who filled two or more antihypertensive prescriptions in the same therapeutic class on different dates within a period of more than 90 days in 2014.

Over 26% of Medicare part D enrollees aged 65 years and over are not taking their antihypertensive drugs properly, according to a report published online Sept. 13 in MMWR.

An analysis of 2014 data showed that 4.9 million hypertensive Medicare patients were taking an incorrect dose of their medication or were not taking it at all, reported Matthew Ritchey, DPT of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s division for heart disease and stroke prevention, and his associates (MMWR. 2016 Sep 13:65).

Nonadherence rates varied considerably by race and ethnicity, with American Indians/Alaska Natives the highest at 39%, followed by blacks at 36%, Hispanics at 34%, Asian/Pacific Islanders at 26%, and white non-Hispanics at 24%, the investigators noted.

The analysis included 18.5 million part D beneficiaries who filled two or more antihypertensive prescriptions in the same therapeutic class on different dates within a period of more than 90 days in 2014.

FROM MMWR

Many patients with diabetic foot infections get unnecessary MRSA treatment

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

Many patients with diabetic foot infections receive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus antibiotics unnecessarily, according to Kelly Reveles, PharmD, and her associates.

Among the 318 patients with diabetic foot infections (DFIs) in the study, S. aureus was the most common pathogen, accounting for 146 cases. MRSA accounted for 47 of S. aureus cases, and 15% of overall cases. Although MRSA accounted for a relatively small number of cases, MRSA antibiotics were administered to 86% of all patients, resulting in 71% of all patients receiving the treatment unnecessarily.

Independent risk factors for MRSA DFI were male sex and bone involvement. Other risk factors included previous MRSA infection, more severe infection, and a higher white cell count. The most common comorbidities of DFI were hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity.

“The improper use of antibiotics unnecessarily exposes the patient to potential complications of the therapy. Furthermore, the overuse of antibiotics drives antimicrobial resistance and is likely to increase the health care burden,” the investigators wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS One (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161658).

FROM PLOS ONE

Type 2 diabetes peer-led intervention in primary care tied to improved depression symptoms

BETHESDA, MD. – A novel, peer- and nurse-led intervention in a primary care setting for type 2 diabetes in people with serious mental illness was associated with improvements in depression symptoms, global psychopathology, and overall health, a study has shown.

“The intervention really is patient self-management. It could be a nice complement to team-based, multidisciplinary care,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data in a poster at a National Institute of Mental Health conference on mental health services research. Dr. Sajatovic is the Willard W. Brown Chair and director of the Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center at University Hospitals Neurological Institute in Cleveland.

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a significantly higher risk of premature death than do those in the general population, in part because this cohort experiences higher rates of metabolic disease, often exacerbated by higher rates of smoking, poor diet, substance abuse, and lack of exercise. However, in a 60-week randomized controlled trial of 200 people with SMI and comorbid type 2 diabetes, which was conducted in a primary care setting, those who were taught better self-care fared better than did those who received treatment as usual.

The group-based, psychosocial intervention – called “targeted training in illness” – blended psychoeducation, problem identification, goal setting, behavioral modeling, and care coordination around SMI and diabetes. In the first 12 weeks, groups of 6-10 people met in weekly, hour-long sessions co-led by a peer and nurse educator. Group discussions focused on self-management of diabetes through proper eating habits, regular exercise, tobacco cessation, and other forms of behavior modification.

Meeting as a group helped to “combat some of the social isolation that you see in this population,” Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. “The peer leadership is really critical, too, because it empowers [the participants]. I believe peer support gives resilience ... and helps [the group] see you don’t have to be perfect to make progress.” In the study, the 3 months of group sessions were followed by weekly telephone maintenance sessions with either the peer or nurse educator for 48 weeks.

Half of the study’s participants – two-thirds of whom were women, and just over half of whom were black – had had a diagnosis of diabetes for at least 10 years; half of all participants used insulin. All had either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder. Baseline rates of depression were high, and psychotic symptoms were minimal.

After assessments at baseline, 13, 30, and 60 weeks, the study arm was found to have improvements in depression, global psychopathology, and functional status, which Dr. Sajatovic said could be attributable to the group’s significantly improved knowledge about diabetes (P less than .01).

Glycemic control improved generally, a surprising finding that Dr. Sajatovic said could have been tied to the expansion of Medicaid in Ohio, where the study was done, and a “real concerted effort” to provide treatment by medical homes at this time.

While no significant difference between the groups was found overall, a post hoc analysis showed a difference in the 53% of the entire sample who had good to fair glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c equal to or less than 7.5) at baseline: At 60 weeks, those in the treatment arm achieved stable, long-term control compared with controls, whose values had worsened slightly (P = .024). Those people tended to be older, more likely to have schizophrenia, and less likely to be on insulin, and to have a shorter history of diabetes, said Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Compared with controls, the study arm had greater improvement at 60 weeks in Clinical Global Impression scores (P = .0008); Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores (P = .0156); Global Assessment of Functioning scores (P = .0031); and knowledge of diabetes (P less than .0002), as well as an improvement trend in Sheehan Disability Scale scores (P = .0863). There was no difference between the groups on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Short Form–36 or HbA1c values. By study’s end, Dr. Sajatovic said about a quarter had been lost to follow-up.

The intervention meets three important criteria, she said. “First, people need to know what to do. Then, they need to have confidence, or self-efficacy. The third thing is that the person has to believe in a given outcome based on a given behavior.”

Dr. Sajatovic did not have any relevant disclosures. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BETHESDA, MD. – A novel, peer- and nurse-led intervention in a primary care setting for type 2 diabetes in people with serious mental illness was associated with improvements in depression symptoms, global psychopathology, and overall health, a study has shown.

“The intervention really is patient self-management. It could be a nice complement to team-based, multidisciplinary care,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data in a poster at a National Institute of Mental Health conference on mental health services research. Dr. Sajatovic is the Willard W. Brown Chair and director of the Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center at University Hospitals Neurological Institute in Cleveland.

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a significantly higher risk of premature death than do those in the general population, in part because this cohort experiences higher rates of metabolic disease, often exacerbated by higher rates of smoking, poor diet, substance abuse, and lack of exercise. However, in a 60-week randomized controlled trial of 200 people with SMI and comorbid type 2 diabetes, which was conducted in a primary care setting, those who were taught better self-care fared better than did those who received treatment as usual.

The group-based, psychosocial intervention – called “targeted training in illness” – blended psychoeducation, problem identification, goal setting, behavioral modeling, and care coordination around SMI and diabetes. In the first 12 weeks, groups of 6-10 people met in weekly, hour-long sessions co-led by a peer and nurse educator. Group discussions focused on self-management of diabetes through proper eating habits, regular exercise, tobacco cessation, and other forms of behavior modification.

Meeting as a group helped to “combat some of the social isolation that you see in this population,” Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. “The peer leadership is really critical, too, because it empowers [the participants]. I believe peer support gives resilience ... and helps [the group] see you don’t have to be perfect to make progress.” In the study, the 3 months of group sessions were followed by weekly telephone maintenance sessions with either the peer or nurse educator for 48 weeks.

Half of the study’s participants – two-thirds of whom were women, and just over half of whom were black – had had a diagnosis of diabetes for at least 10 years; half of all participants used insulin. All had either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder. Baseline rates of depression were high, and psychotic symptoms were minimal.

After assessments at baseline, 13, 30, and 60 weeks, the study arm was found to have improvements in depression, global psychopathology, and functional status, which Dr. Sajatovic said could be attributable to the group’s significantly improved knowledge about diabetes (P less than .01).

Glycemic control improved generally, a surprising finding that Dr. Sajatovic said could have been tied to the expansion of Medicaid in Ohio, where the study was done, and a “real concerted effort” to provide treatment by medical homes at this time.

While no significant difference between the groups was found overall, a post hoc analysis showed a difference in the 53% of the entire sample who had good to fair glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c equal to or less than 7.5) at baseline: At 60 weeks, those in the treatment arm achieved stable, long-term control compared with controls, whose values had worsened slightly (P = .024). Those people tended to be older, more likely to have schizophrenia, and less likely to be on insulin, and to have a shorter history of diabetes, said Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Compared with controls, the study arm had greater improvement at 60 weeks in Clinical Global Impression scores (P = .0008); Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores (P = .0156); Global Assessment of Functioning scores (P = .0031); and knowledge of diabetes (P less than .0002), as well as an improvement trend in Sheehan Disability Scale scores (P = .0863). There was no difference between the groups on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Short Form–36 or HbA1c values. By study’s end, Dr. Sajatovic said about a quarter had been lost to follow-up.

The intervention meets three important criteria, she said. “First, people need to know what to do. Then, they need to have confidence, or self-efficacy. The third thing is that the person has to believe in a given outcome based on a given behavior.”

Dr. Sajatovic did not have any relevant disclosures. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BETHESDA, MD. – A novel, peer- and nurse-led intervention in a primary care setting for type 2 diabetes in people with serious mental illness was associated with improvements in depression symptoms, global psychopathology, and overall health, a study has shown.

“The intervention really is patient self-management. It could be a nice complement to team-based, multidisciplinary care,” said Martha Sajatovic, MD, who presented the data in a poster at a National Institute of Mental Health conference on mental health services research. Dr. Sajatovic is the Willard W. Brown Chair and director of the Neurological & Behavioral Outcomes Center at University Hospitals Neurological Institute in Cleveland.

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have a significantly higher risk of premature death than do those in the general population, in part because this cohort experiences higher rates of metabolic disease, often exacerbated by higher rates of smoking, poor diet, substance abuse, and lack of exercise. However, in a 60-week randomized controlled trial of 200 people with SMI and comorbid type 2 diabetes, which was conducted in a primary care setting, those who were taught better self-care fared better than did those who received treatment as usual.

The group-based, psychosocial intervention – called “targeted training in illness” – blended psychoeducation, problem identification, goal setting, behavioral modeling, and care coordination around SMI and diabetes. In the first 12 weeks, groups of 6-10 people met in weekly, hour-long sessions co-led by a peer and nurse educator. Group discussions focused on self-management of diabetes through proper eating habits, regular exercise, tobacco cessation, and other forms of behavior modification.

Meeting as a group helped to “combat some of the social isolation that you see in this population,” Dr. Sajatovic said in an interview. “The peer leadership is really critical, too, because it empowers [the participants]. I believe peer support gives resilience ... and helps [the group] see you don’t have to be perfect to make progress.” In the study, the 3 months of group sessions were followed by weekly telephone maintenance sessions with either the peer or nurse educator for 48 weeks.

Half of the study’s participants – two-thirds of whom were women, and just over half of whom were black – had had a diagnosis of diabetes for at least 10 years; half of all participants used insulin. All had either schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder. Baseline rates of depression were high, and psychotic symptoms were minimal.

After assessments at baseline, 13, 30, and 60 weeks, the study arm was found to have improvements in depression, global psychopathology, and functional status, which Dr. Sajatovic said could be attributable to the group’s significantly improved knowledge about diabetes (P less than .01).

Glycemic control improved generally, a surprising finding that Dr. Sajatovic said could have been tied to the expansion of Medicaid in Ohio, where the study was done, and a “real concerted effort” to provide treatment by medical homes at this time.

While no significant difference between the groups was found overall, a post hoc analysis showed a difference in the 53% of the entire sample who had good to fair glycemic control (hemoglobin A1c equal to or less than 7.5) at baseline: At 60 weeks, those in the treatment arm achieved stable, long-term control compared with controls, whose values had worsened slightly (P = .024). Those people tended to be older, more likely to have schizophrenia, and less likely to be on insulin, and to have a shorter history of diabetes, said Dr. Sajatovic, professor of psychiatry and of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland.

Compared with controls, the study arm had greater improvement at 60 weeks in Clinical Global Impression scores (P = .0008); Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores (P = .0156); Global Assessment of Functioning scores (P = .0031); and knowledge of diabetes (P less than .0002), as well as an improvement trend in Sheehan Disability Scale scores (P = .0863). There was no difference between the groups on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, the Short Form–36 or HbA1c values. By study’s end, Dr. Sajatovic said about a quarter had been lost to follow-up.

The intervention meets three important criteria, she said. “First, people need to know what to do. Then, they need to have confidence, or self-efficacy. The third thing is that the person has to believe in a given outcome based on a given behavior.”

Dr. Sajatovic did not have any relevant disclosures. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT AN NIMH CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Targeted training in illness management effectively improves overall health outcomes in people with serious mental illness and comorbid type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: Compared with treatment as usual, peer-led intervention improved depression, overall health, and knowledge of diabetes at 60 weeks.

Data source: Randomized, controlled study of 200 people with serious mental illness and comorbid type 2 diabetes seen in primary care.

Disclosures: Dr. Sajatovic did not have any relevant disclosures. The National Institutes of Health funded the study.

Is an SGLT2 inhibitor right for your patient with type 2 diabetes?

› Consider sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line agents in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who need mild hemoglobin A1c reductions (≤1%) and who would benefit from mild to modest weight and blood pressure reductions. A

› Avoid using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with a history of recurrent genital mycotic or urinary tract infections. B

› Use SGLT2 inhibitors with caution in patients at risk for volume-related adverse effects (dizziness and hypotension), such as the elderly, those with moderate renal dysfunction, and those taking concomitant diuretic therapy. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Joe S is a 41-year-old African-American man who comes to your clinic after his employee health screening revealed elevated triglycerides. The patient has a 3-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); he also has a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obstructive sleep apnea. Mr. S tells you he takes metformin 1000 mg twice daily, but stopped taking his glipizide because he didn’t think it was helping his blood sugar. His last hemoglobin (Hb) A1c result was 8.8%, and he is very resistant to starting insulin therapy.

The patient’s other medications include enalapril 10 mg/d, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and omeprazole 20 mg/d. Mr. S weighs 255.6 lbs (body mass index=34.7), his BP is 140/88 mm Hg, and his heart rate is 82 beats per minute. Laboratory values include: serum creatinine, 1.01 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >100 mL/min/1.73 m2; potassium (K), 4.3 mmol/L; serum phosphorous (Phos), 2.8 mg/dL; magnesium (Mg), 1.9 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 167 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 78 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 38 mg/dL; and triglycerides, 256 mg/dL.

CASE 2 › Susan R, a 68-year-old Caucasian woman, returns to your clinic for a follow-up visit 3 months after you prescribed dapagliflozin 10 mg/d for her T2DM. Her glucose levels have improved, but she complains of vaginal pruritus and is worried that she has a yeast infection.

You diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis in this patient and prescribe a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg. After reviewing her laboratory test results, you notice that since starting the dapagliflozin, her HbA1c level has improved slightly from 9.8% to 9.3%, but is still not where it needs to be. Her eGFR is 49 mL/min/1.73 m2.

What would you recommend to improve control of these patients’ blood glucose levels?

When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor

Consider therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors in adult patients with T2DM who:3-9,13-15,17-24

- have an HbA1c between 7% and 9%

- would benefit from weight and/or blood pressure reductions

- have metabolic syndrome

- have adequate means to pay for the medication (ie, prescription coverage or the ability to afford it).

In addition, consider an SGLT2 inhibitor as initial monotherapy if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated, or as add-on therapy to metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, or insulin.

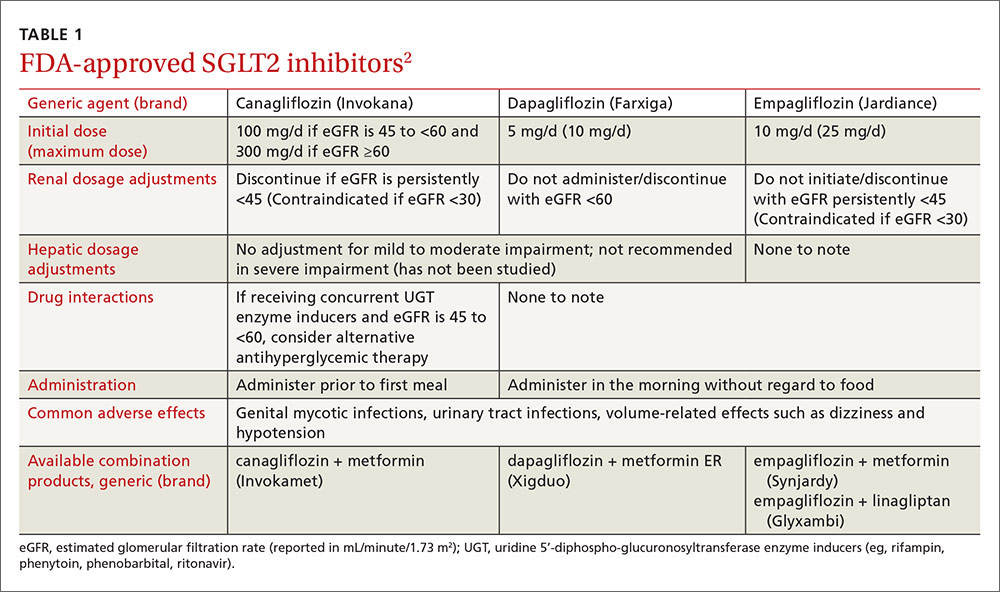

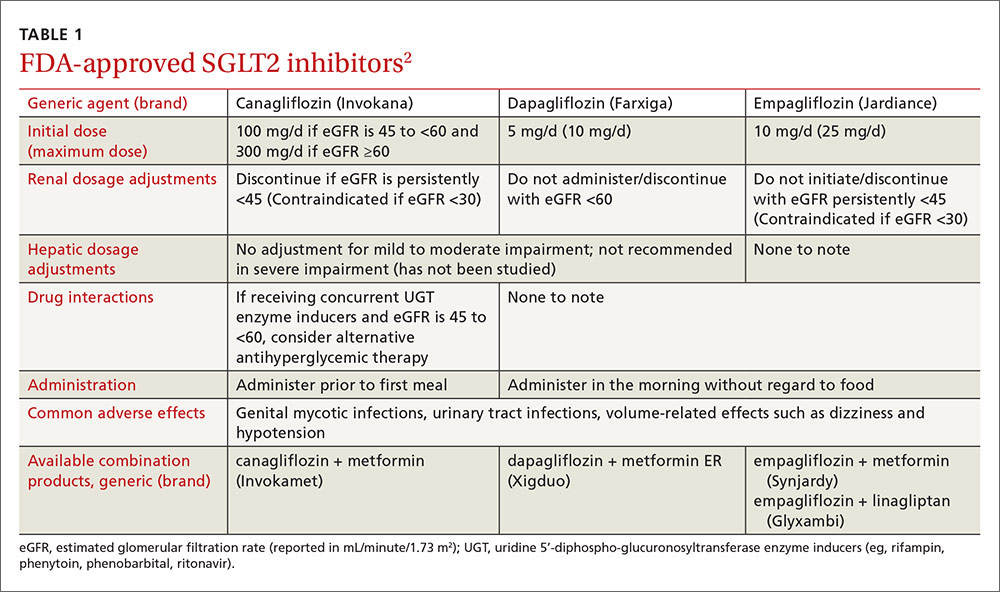

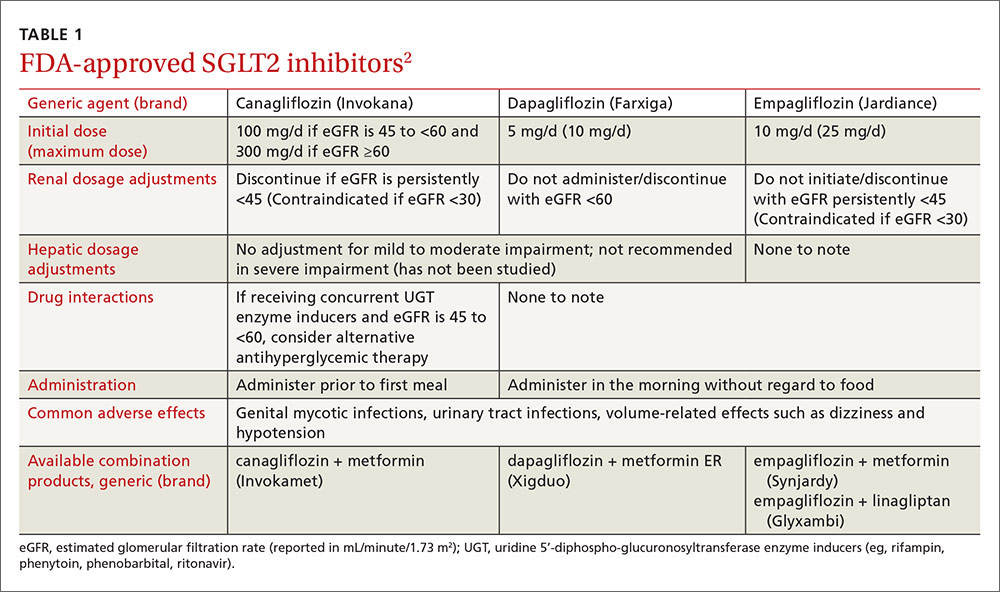

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are the newest class of agents to enter the T2DM management arena. They act in the proximal renal tubules to decrease the reabsorption of glucose by targeting the SGLT2 transmembrane protein, which reabsorbs about 90% of the body’s glucose.1,2 The class is currently made up of 3 agents—canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin—all of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of T2DM (TABLE 1).2

The American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes published updated guidelines for T2DM management in 2015.1 In addition to lifestyle modifications, the guidelines recommend the use of metformin as first-line therapy unless it is contraindicated or patients are unable to tolerate it (eg, because of gastrointestinal adverse effects). They recommend other pharmacologic therapies as second-line options based on specific patient characteristics. Thus, SGLT2 inhibitors may be used as add-on therapy after metformin, or as a first-line option if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Because the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors is independent of insulin secretion, these agents may be used at any stage of the diabetes continuum.

SGLT2 agents as monotherapy, or as add-on therapy

All SGLT2 agents have been studied as monotherapy accompanied by diet and exercise and shown to produce HbA1c reductions of 0.34% to 1.11%.3-6 In trials, the effect was similar regardless of study duration (18-104 weeks); generally, higher doses corresponded with larger HbA1c reductions.3-6

SGLT2 inhibitors have also been studied as add-on therapy to several oral agents including metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), and the combination of metformin plus sulfonylureas or TZDs or dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors.1 When used in any of these combinations, each SGLT2 agent demonstrated a consistent HbA1c lowering effect of 0.62% to 1.19%.7-14

Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors have been studied in combination with insulin therapy (median or mean daily doses >60 units), which yielded further reductions in HbA1c of 0.58% to 1.02% without significant insulin adjustments or an increase in major hypoglycemia events.15-17 Patients receiving insulin and an SGLT2 inhibitor had lower insulin doses and more weight loss compared to placebo groups.

SGLT2 inhibitors offer additional benefits

Secondary analyses of most studies of SGLT2 inhibitors include changes in BP and weight from baseline as well as minor changes (some positive, some not) in several lipid parameters.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 In general, these effects do not appear to be dose-dependent (with the exception of canagliflozin and its associated lipid effects25) and are similar among the 3 medications.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 (For more on who would benefit from these agents, see “When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor” above.)

BP reduction. Although the mean baseline BP was controlled in most studies, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to significantly reduce BP. Reductions in BP with all 3 SGLT2 medications range from approximately 2 to 5 mm Hg systolic and 0.5 to 2.5 mm Hg diastolic, which may be due to weight loss and diuresis.4-8,10-16,20-23 While the reductions were modest at best, one study involving empagliflozin reported that more than one-quarter of patients with uncontrolled BP at baseline achieved a BP <130/80 mm Hg 24 weeks later.5 While these agents should not be used solely for their BP lowering effects, they may help a small number of patients with mildly elevated BP achieve their goal without an additional antihypertensive agent.

Weight reduction. Modest weight loss, likely due to the loss of calories through urine, was seen with SGLT2 inhibitors in most studies, with reductions persisting beyond one year of use. In most studies, including those involving obese patients on insulin therapy,15,17,21 patients’ body weights were reduced by approximately 2 to 4 kg from baseline.3-16,18,21-23,26

Lipid effects. Although the mechanism is unclear, use of SGLT2 inhibitors can have varying effects on lipid panels. In most studies, total and LDL cholesterol levels were increased with elevations ranging from 0.7 to 10 mg/dL.3,7,8,18,19,22,23 Conversely, at least one study demonstrated mild reductions in total and LDL cholesterol levels with higher doses of empagliflozin.13 Additionally, modest reductions in triglycerides and increases in HDL across all doses of canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin have been seen.8,9,13,15,19 While the clinical relevance of these lipid changes is unknown, monitoring is recommended.2

These agents are well tolerated

SGLT2 inhibitors were generally well tolerated in studies. The most common adverse effects include mycotic infections (2.4%-21.6%) and urinary tract infections (UTIs) (4.0%-19.6%) (both with higher incidences in females); volume-related effects such as dizziness and hypotension (0.3%-8.3%); and nasopharyngitis (5.4%-18.3%).4-14,16-23,26-28 Hypoglycemia was observed more often when an SGLT2 inhibitor was used in combination with a sulfonylurea or insulin therapy.4-14,16-23,26-28 The number of times adverse events led to discontinuation was low and similar to that in control groups.4-14,16-23,26-28

Mycotic and urinary infections should be diagnosed and treated according to current standards of care and do not require discontinuation of the SGLT2 inhibitor. Canagli-flozin therapy was associated with electrolyte abnormalities including hyperkalemia, hypermagnesemia, and hyperphosphatemia.25 Thus, levels should be monitored periodically, especially in patients predisposed to elevations due to other conditions or medications.25

Two additional warnings are worth noting

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) has been reported with all 3 agents, and bone fractures have been reported with canagliflozin.

The FDA issued a warning in May 2015 regarding the increased risk of DKA with the use of SGLT2 inhibitor single and combination products.29 This warning was prompted by several case reports of DKA with uncharacteristically mild to moderate glucose elevations in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and T2DM who were taking an SGLT2 inhibitor. The absence of significant hyperglycemia delayed diagnosis in many cases. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of DKA, as well as when to seek medical attention.

Patients with diabetes and symptoms of ketoacidosis (eg, difficulty breathing, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, confusion, and fatigue) should be evaluated regardless of current blood glucose levels, and SGLT2 inhibitors should be discontinued if acidosis is confirmed. Identified potential triggers include illness, reduced food and fluid intake, reduced insulin dose, and history of alcohol intake. Use of SGLT2 inhibitors should be avoided in patients with T1DM until safety and efficacy are established in large randomized controlled trials. The European Medicines Agency announced that a thorough review of all currently approved SGLT2 agents is underway to evaluate the risk for DKA.30

In addition, the FDA called for a revision of the label of canagliflozin to reflect a strengthened warning about an increased risk of bone fractures and decreased bone mineral density (BMD).31 Fractures can occur as early as 12 weeks after initiating treatment and with only minor trauma.31

Over a 2-year period, canagliflozin also significantly decreased BMD in the hip and lower spine compared to placebo.31 Patients should be evaluated for additional risk factors for fracture before taking canagliflozin.31 The FDA is continuing to evaluate whether the other approved SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with an increased risk for fractures.

Drug interactions: Proceed carefully with diuretics

The number of drugs that interact with SGLT2 inhibitors is minimal. Because these agents can cause volume-related effects such as hypotension, dizziness, and osmotic diuresis, patients—particularly the elderly and those with renal impairment—taking concomitant diuretics, especially loop diuretics, may be at increased risk for these effects and should be monitored accordingly.2,25

Canagliflozin is primarily metabolized via glucuronidation by the uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes. Therefore, UGT enzyme inducers (eg, rifampin, phenytoin, phenobarbital, ritonavir) decrease canagliflozin’s serum concentration. If a patient has an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and is tolerating a dose of 100 mg/d, consider increasing the dose to 300 mg/d during concomitant treatment.

In addition, researchers have found that canagliflozin increases serum levels of digoxin by between 20% and 36%.25 Experts suspect this occurs because canagliflozin inhibits P-glycoprotein efflux of digoxin. Although monitoring of digoxin levels is recommended, this interaction is considered to be minor.25

Cost consideration: SGLT2 inhibitors are more expensive

The SGLT2 inhibitors are available only as brand name products and are more expensive than agents that have generic options (eg, metformin, sulfonylureas, TZDs). The average wholesale cost is approximately $400 for a 30-day supply of all SGLT2 agents.32 When considering an SGLT2 inhibitor, the patient should ideally have medication prescription coverage. Depending on the specific insurance plan, these agents are classified as tier 2 to 4, which is comparable to other oral brand name options.

Research looks at CV outcomes and cancer risk

Cardiovascular (CV) risk reduction. To date, only one study evaluating the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on CV outcomes is complete.33 Two large randomized controlled trials involving canagliflozin and dapagliflozin designed to evaluate treatment effects on major CV endpoints are ongoing.34,35

In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial,33 researchers found that empagliflozin had beneficial effects on CV outcomes, making it one of the only antidiabetic agents on the market to have such benefits. The study, which involved more than 7000 patients with a history of T2DM and existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), found that 10.5% of patients in the empagliflozin group vs 12.1% in the placebo group died from a CV cause or experienced a nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke over a median of 3.1 years. Results were similar with both doses (10 mg vs 25 mg) of empagliflozin. The mechanisms behind the CV benefits are likely multifactorial and may be related to reductions in weight and BP,33 but additional research is needed to fully elucidate the role of empagliflozin in this population.

Canagliflozin is being evaluated in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) for its effect on major CV events—CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke—in patients with either a history of CVD or who are at increased risk of CVD and have uncontrolled diabetes.34 The trial is expected to wrap up in June 2017.

And dapagliflozin is being studied in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial (the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events) in patients with T2DM and either known CVD or at least 2 risk factors for CVD.35 The study is designed to assess dapagliflozin’s effect on the incidence of CV death, myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke and has an estimated completion date of April 2019, which will provide a median follow-up of 4.5 years.

Cancer. All 3 agents have been examined for any possible carcinogenic links. In 2011, the FDA issued a request for further investigation surrounding the risk of cancer associated with dapagliflozin.36 As of November 2013, 10 of 6045 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed bladder cancer compared to 1 of 3512 controls.36 Furthermore, 9 of 2223 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed breast cancer compared to 1 of 1053 controls.36

Although the trials were not designed to detect an increase in risk, the number of observed cases warranted further investigation. No official warning for breast cancer exists since the characteristics of the malignancies led the FDA to believe dapagliflozin was unlikely the cause.36

Given what we know to date, it appears to be prudent to avoid prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with active bladder cancer, and to use them with caution in those with a history of the disease.2

Other studies. Initially, animal studies suggested an increased risk of various malignancies associated with canagliflozin use in rats,37 but consistent results were not seen in human studies. Similarly, at least one study found that empagliflozin was associated with lung cancer and melanoma, but closer examination found that most patients who developed these cancers had risk factors.38 Large, long-term studies of these agents in various populations are needed to thoroughly investigate possible carcinogenicity.

Additional considerations: Kidney function, age, and pregnancy

Consider avoiding SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with moderate kidney dysfunction (eGFR 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2). Studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors are not as effective at lowering blood glucose in those with reduced eGFR, although adverse events were similar to those in placebo groups.24,39,40 Dapagliflozin is not recommended in patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 due to lack of efficacy.2,24 Empagliflozin does not require dose adjustments if eGFR is ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2. A lower dose of canagliflozin (ie, 100 mg/d) is recommended in those with an eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2.2 All agents are contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Older patients are at higher risk for dehydration, hypotension, and falls; therefore, SGLT2 inhibitors should be used with caution in this population. Similarly, they should not be used in patients with T1DM and should be avoided in those with active, or a history of, DKA.

There are no data on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in pregnancy; thus, these agents should be avoided unless the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks to the unborn fetus.2

CASE 1 › An SGLT2 inhibitor is an acceptable option for Mr. S. Because he is resistant to starting insulin therapy and his HbA1c is <9%, an additional oral medication is reasonable. Adding an SGLT2 inhibitor may reduce his HbA1c up to ~1%, and education on lifestyle modifications may help bring him to goal. An SGLT2 inhibitor may also benefit his BP and weight, both of which could be improved.

Given the drugs he’s taking, drug interactions should not be an issue, and his renal function and pertinent labs (K, Phos, Mg) are within normal limits. Nevertheless, monitor these labs periodically and monitor Mr. S for adverse effects, such as UTIs, although these are more common in women. Canagliflozin is the preferred SGLT2 inhibitor on his insurance formulary, so you could initiate therapy at 100 mg/d, administered prior to the first meal, and increase to 300 mg/d if needed. As an alternative, consider prescribing the metformin/canagliflozin combination agent.

CASE 2 › Ms. R is likely experiencing a yeast infection as an adverse effect of the dapagliflozin. Although one yeast infection is insufficient grounds for discontinuation of the drug, recurrent infections should prompt a risk-to-benefit analysis to determine whether it’s worth continuing the medication. Her recent eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) is, however, a contraindication to dapagliflozin, and therapy should be discontinued. Canagliflozin and empagliflozin may be considered since her eGFR is >45 mL/min/1.73 m2, but given her current HbA1c and recent adverse drug event, alternative therapies, such as basal insulin, are more appropriate treatment choices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katelin M. Lisenby, PharmD, BCPS, University of Alabama College of Community Health Sciences, University Medical Center, Box 870374, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; kmh0003@auburn.edu.

1. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140-149.

2. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin. Lexicomp, Inc. (Lexi-Drugs®). Accessed October 12, 2015.

3. Stenlöf K, Cefalu WT, Kim KA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of canagliflozin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with diet and exercise: findings from the 52-week CANTATA-M study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:163-175.

4. Ferrannini E, Ramos SJ, Salsali A, et al. Dapagliflozin monotherapy in type 2 diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control by diet and exercise: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Diabetes Care. 2010:33:2217-2224.

5. Roden M, Weng J, Eilbracht J, et al. Empagliflozin monotherapy with sitagliptin as an active comparator in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:208-219.

6. Ferrannini E, Berk A, Hantel S, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of empagliflozin, sitagliptin, and metformin: an active-controlled, parallel-group, randomized, 78-week open-label extension study in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:4015-4021.

7. Wilding JPH, Charpentier G, Hollander P, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus inadequately controlled with metformin and sulphonylurea: a randomised trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:1267-1282.

8. Forst T, Guthrie R, Goldenberg R, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin over 52 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes on background metformin and pioglitazone. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:467-477.

9. Schernthaner G, Gross JL, Rosenstock J, et al. Canagliflozin compared with sitagliptin for patients with type 2 diabetes who do not have adequate glycemic control with metformin plus sulfonylurea: a 52-week randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2508-2515.

10. Bristol-Myers Squibb [press release]. New phase III data showed dapagliflozin significantly reduced HbA1c compared to placebo at 24 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with the combination of metformin plus sulfonylurea. Available at: http://news.bms.com/press-release/rd-news/new-phase-iii-data-showed-dapagliflozin-significantly-reduced-hba1c-compared-p&t=635156160653787526. Accessed September 17, 2015.

11. Jabbour SA, Hardy E, Sugg J, et al. Dapagliflozin is effective as add-on therapy to sitagliptin with or without metformin: a 24- week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:740-750.

12. DeFronzo RA, Lewin A, Patel S, et al. Combination of empagliflozin and linagliptin as second-line therapy in subjects with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:384-393.

13. Kovacs CS, Seshiah V, Merker L, et al. Empagliflozin as add-on therapy to pioglitazone with or without metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2015;37:1773-1788.

14. Haring HU, Merker L, Seewaldt-Becker E, et al. Empagliflozin as add-on to metformin plus sulfonylurea in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 24-week, randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:3396-3404.

15. Neal B, Percovik V, de Zeeuw D, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin, an inhibitor of sodium–glucose cotransporter 2, when used in conjunction with insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:403-411.

16. Wilding JPH, Woo V, Soler NG, et al. Long-term efficacy of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus receiving high doses of insulin: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:405-415.

17. Rosenstock J, Jelaska A, Frappin G, et al. Improved glucose control with weight loss, lower insulin doses, and no increased hypoglycemia with empagliflozin added to titrated multiple daily injections of insulin in obese inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1815-1823.

18. Cefalu WT, Leiter LA, Yoon KH, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin (CANTATA-SU): 52 week results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;382:941-950.

19. Bailey CJ, Gross JL, Pieters A, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control with metformin: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2010:375:2223-2233.

20. Bailey CJ, Gross JL, Hennicken D, et al. Dapagliflozin add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 102-week trial. BMC Med. 2013;11:43.

21. Rosenstock J, Vico M, Wei L, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, on HbA(1c), body weight, and hypoglycemia risk in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on pioglitazone monotherapy. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1473-1478.

22. Merker L, Häring HU, Christiansen AV, et al. Empagliflozin as add-on to metformin in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1555-1567.

23. Ridderstråle M, Anderson KR, Zeller C, et al. Comparison of empagliflozin and glimepiride as add-on to metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 104-week randomised, active-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:691-700.

24. Kohan DE, Fioretto P, Tang W, et al. Long-term study of patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment shows that dapagliflozin reduces weight and blood pressure but does not improve glycemic control. Kidney Int. 2014;85:962-971.

25. Invokana (canagliflozin) tablets [product information]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc. Available at: https://www.invokana.com. Accessed March 15, 2013.

26. Lavalle-González FJ, Januszewicz A, Davidson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin compared with placebo and sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes on background metformin monotherapy: a randomised trial. Diabetologia. 2013;56:2582-2592.

27. Strojek K, Yoon KH, Hruba V, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control with glimepiride: a randomized, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:928-938.

28. Leiter LA, Yoon KH, Arias P, et al. Canagliflozin provides durable glycemic improvements and body weight reduction over 104 weeks versus glimepiride in patients with type 2 diabetes on metformin: a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:355-364.

29. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA warns that SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes may result in a serious condition of too much acid in the blood. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm446845.htm. Accessed July 11, 2016.

30. Rosenstock J, Ferrannini E. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a predictable, detectable, and preventable safety concern with SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1638-1642.

31. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA revises label of diabetes drug canagliflozin (Invokana, Invokamet) to include updates on bone fracture risk and new information on decreased bone mineral density. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm461449.htm. Acces-sed July 11, 2016.

32. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin. In: RED BOOK [AUHSOP intranet database]. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics; [updated daily]. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/ND_T/evidencexpert/ND_PR/evidencexpert/CS/BB1644/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/FAF693/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/PFActionId/redbook.ShowProductSearchResults?SearchTerm=JARDIANCE&searchType=redbookProductName&searchTermId=42798&searchContent=%24searchContent&searchFilterAD=filterADActive&searchFilterRepackager=filterExcludeRepackager&searchPattern=%5Ejard. Accessed March 15, 2016.

33. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2117-2128.

34. CANagliflozin cardioVascular Assessment Study (CANVAS). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01032629. Accessed October 12, 2015.

35. Multicenter trial to evaluate the effect of dapagliflozin on the incidence of cardiovascular events (DECLARE-TIMI 58). Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01730534. Accessed October 12, 2015.

36. FDA background document. BMS-512148 NDA 202293. In: Proceedings of the US Food and Drug Administration Endocrinologic & Metabolic Drug Advisory Committee Meeting, 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/endocrinologicandmetabolicdrugsadvisorycommittee/ucm378079.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2015.

37. Lin HW, Tseng CH. A review of the relationship between SGLT2 inhibitors and cancer. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:719578.

38. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Risk assessment and risk mitigation review(s). July 28, 2014. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/ 204629Orig1s000RiskR.pdf. Accessed September 21, 2015.

39. Yale JF, Bakris G, Cariou B, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin over 52 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:1016-1027.

40. Barnett AH, Mithal A, Manassie J, et al. Efficacy and safety of empagliflozin added to existing antidiabetes treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2: 369-384.

› Consider sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line agents in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who need mild hemoglobin A1c reductions (≤1%) and who would benefit from mild to modest weight and blood pressure reductions. A

› Avoid using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with a history of recurrent genital mycotic or urinary tract infections. B

› Use SGLT2 inhibitors with caution in patients at risk for volume-related adverse effects (dizziness and hypotension), such as the elderly, those with moderate renal dysfunction, and those taking concomitant diuretic therapy. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Joe S is a 41-year-old African-American man who comes to your clinic after his employee health screening revealed elevated triglycerides. The patient has a 3-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); he also has a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obstructive sleep apnea. Mr. S tells you he takes metformin 1000 mg twice daily, but stopped taking his glipizide because he didn’t think it was helping his blood sugar. His last hemoglobin (Hb) A1c result was 8.8%, and he is very resistant to starting insulin therapy.

The patient’s other medications include enalapril 10 mg/d, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and omeprazole 20 mg/d. Mr. S weighs 255.6 lbs (body mass index=34.7), his BP is 140/88 mm Hg, and his heart rate is 82 beats per minute. Laboratory values include: serum creatinine, 1.01 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >100 mL/min/1.73 m2; potassium (K), 4.3 mmol/L; serum phosphorous (Phos), 2.8 mg/dL; magnesium (Mg), 1.9 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 167 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 78 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 38 mg/dL; and triglycerides, 256 mg/dL.

CASE 2 › Susan R, a 68-year-old Caucasian woman, returns to your clinic for a follow-up visit 3 months after you prescribed dapagliflozin 10 mg/d for her T2DM. Her glucose levels have improved, but she complains of vaginal pruritus and is worried that she has a yeast infection.

You diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis in this patient and prescribe a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg. After reviewing her laboratory test results, you notice that since starting the dapagliflozin, her HbA1c level has improved slightly from 9.8% to 9.3%, but is still not where it needs to be. Her eGFR is 49 mL/min/1.73 m2.

What would you recommend to improve control of these patients’ blood glucose levels?

When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor

Consider therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors in adult patients with T2DM who:3-9,13-15,17-24

- have an HbA1c between 7% and 9%

- would benefit from weight and/or blood pressure reductions

- have metabolic syndrome

- have adequate means to pay for the medication (ie, prescription coverage or the ability to afford it).

In addition, consider an SGLT2 inhibitor as initial monotherapy if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated, or as add-on therapy to metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, or insulin.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are the newest class of agents to enter the T2DM management arena. They act in the proximal renal tubules to decrease the reabsorption of glucose by targeting the SGLT2 transmembrane protein, which reabsorbs about 90% of the body’s glucose.1,2 The class is currently made up of 3 agents—canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin—all of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of T2DM (TABLE 1).2

The American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes published updated guidelines for T2DM management in 2015.1 In addition to lifestyle modifications, the guidelines recommend the use of metformin as first-line therapy unless it is contraindicated or patients are unable to tolerate it (eg, because of gastrointestinal adverse effects). They recommend other pharmacologic therapies as second-line options based on specific patient characteristics. Thus, SGLT2 inhibitors may be used as add-on therapy after metformin, or as a first-line option if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Because the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors is independent of insulin secretion, these agents may be used at any stage of the diabetes continuum.

SGLT2 agents as monotherapy, or as add-on therapy

All SGLT2 agents have been studied as monotherapy accompanied by diet and exercise and shown to produce HbA1c reductions of 0.34% to 1.11%.3-6 In trials, the effect was similar regardless of study duration (18-104 weeks); generally, higher doses corresponded with larger HbA1c reductions.3-6

SGLT2 inhibitors have also been studied as add-on therapy to several oral agents including metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), and the combination of metformin plus sulfonylureas or TZDs or dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors.1 When used in any of these combinations, each SGLT2 agent demonstrated a consistent HbA1c lowering effect of 0.62% to 1.19%.7-14

Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors have been studied in combination with insulin therapy (median or mean daily doses >60 units), which yielded further reductions in HbA1c of 0.58% to 1.02% without significant insulin adjustments or an increase in major hypoglycemia events.15-17 Patients receiving insulin and an SGLT2 inhibitor had lower insulin doses and more weight loss compared to placebo groups.

SGLT2 inhibitors offer additional benefits

Secondary analyses of most studies of SGLT2 inhibitors include changes in BP and weight from baseline as well as minor changes (some positive, some not) in several lipid parameters.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 In general, these effects do not appear to be dose-dependent (with the exception of canagliflozin and its associated lipid effects25) and are similar among the 3 medications.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 (For more on who would benefit from these agents, see “When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor” above.)

BP reduction. Although the mean baseline BP was controlled in most studies, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to significantly reduce BP. Reductions in BP with all 3 SGLT2 medications range from approximately 2 to 5 mm Hg systolic and 0.5 to 2.5 mm Hg diastolic, which may be due to weight loss and diuresis.4-8,10-16,20-23 While the reductions were modest at best, one study involving empagliflozin reported that more than one-quarter of patients with uncontrolled BP at baseline achieved a BP <130/80 mm Hg 24 weeks later.5 While these agents should not be used solely for their BP lowering effects, they may help a small number of patients with mildly elevated BP achieve their goal without an additional antihypertensive agent.

Weight reduction. Modest weight loss, likely due to the loss of calories through urine, was seen with SGLT2 inhibitors in most studies, with reductions persisting beyond one year of use. In most studies, including those involving obese patients on insulin therapy,15,17,21 patients’ body weights were reduced by approximately 2 to 4 kg from baseline.3-16,18,21-23,26

Lipid effects. Although the mechanism is unclear, use of SGLT2 inhibitors can have varying effects on lipid panels. In most studies, total and LDL cholesterol levels were increased with elevations ranging from 0.7 to 10 mg/dL.3,7,8,18,19,22,23 Conversely, at least one study demonstrated mild reductions in total and LDL cholesterol levels with higher doses of empagliflozin.13 Additionally, modest reductions in triglycerides and increases in HDL across all doses of canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin have been seen.8,9,13,15,19 While the clinical relevance of these lipid changes is unknown, monitoring is recommended.2

These agents are well tolerated

SGLT2 inhibitors were generally well tolerated in studies. The most common adverse effects include mycotic infections (2.4%-21.6%) and urinary tract infections (UTIs) (4.0%-19.6%) (both with higher incidences in females); volume-related effects such as dizziness and hypotension (0.3%-8.3%); and nasopharyngitis (5.4%-18.3%).4-14,16-23,26-28 Hypoglycemia was observed more often when an SGLT2 inhibitor was used in combination with a sulfonylurea or insulin therapy.4-14,16-23,26-28 The number of times adverse events led to discontinuation was low and similar to that in control groups.4-14,16-23,26-28

Mycotic and urinary infections should be diagnosed and treated according to current standards of care and do not require discontinuation of the SGLT2 inhibitor. Canagli-flozin therapy was associated with electrolyte abnormalities including hyperkalemia, hypermagnesemia, and hyperphosphatemia.25 Thus, levels should be monitored periodically, especially in patients predisposed to elevations due to other conditions or medications.25

Two additional warnings are worth noting

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) has been reported with all 3 agents, and bone fractures have been reported with canagliflozin.

The FDA issued a warning in May 2015 regarding the increased risk of DKA with the use of SGLT2 inhibitor single and combination products.29 This warning was prompted by several case reports of DKA with uncharacteristically mild to moderate glucose elevations in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and T2DM who were taking an SGLT2 inhibitor. The absence of significant hyperglycemia delayed diagnosis in many cases. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of DKA, as well as when to seek medical attention.

Patients with diabetes and symptoms of ketoacidosis (eg, difficulty breathing, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, confusion, and fatigue) should be evaluated regardless of current blood glucose levels, and SGLT2 inhibitors should be discontinued if acidosis is confirmed. Identified potential triggers include illness, reduced food and fluid intake, reduced insulin dose, and history of alcohol intake. Use of SGLT2 inhibitors should be avoided in patients with T1DM until safety and efficacy are established in large randomized controlled trials. The European Medicines Agency announced that a thorough review of all currently approved SGLT2 agents is underway to evaluate the risk for DKA.30

In addition, the FDA called for a revision of the label of canagliflozin to reflect a strengthened warning about an increased risk of bone fractures and decreased bone mineral density (BMD).31 Fractures can occur as early as 12 weeks after initiating treatment and with only minor trauma.31

Over a 2-year period, canagliflozin also significantly decreased BMD in the hip and lower spine compared to placebo.31 Patients should be evaluated for additional risk factors for fracture before taking canagliflozin.31 The FDA is continuing to evaluate whether the other approved SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with an increased risk for fractures.

Drug interactions: Proceed carefully with diuretics

The number of drugs that interact with SGLT2 inhibitors is minimal. Because these agents can cause volume-related effects such as hypotension, dizziness, and osmotic diuresis, patients—particularly the elderly and those with renal impairment—taking concomitant diuretics, especially loop diuretics, may be at increased risk for these effects and should be monitored accordingly.2,25

Canagliflozin is primarily metabolized via glucuronidation by the uridine 5'-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes. Therefore, UGT enzyme inducers (eg, rifampin, phenytoin, phenobarbital, ritonavir) decrease canagliflozin’s serum concentration. If a patient has an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and is tolerating a dose of 100 mg/d, consider increasing the dose to 300 mg/d during concomitant treatment.

In addition, researchers have found that canagliflozin increases serum levels of digoxin by between 20% and 36%.25 Experts suspect this occurs because canagliflozin inhibits P-glycoprotein efflux of digoxin. Although monitoring of digoxin levels is recommended, this interaction is considered to be minor.25

Cost consideration: SGLT2 inhibitors are more expensive

The SGLT2 inhibitors are available only as brand name products and are more expensive than agents that have generic options (eg, metformin, sulfonylureas, TZDs). The average wholesale cost is approximately $400 for a 30-day supply of all SGLT2 agents.32 When considering an SGLT2 inhibitor, the patient should ideally have medication prescription coverage. Depending on the specific insurance plan, these agents are classified as tier 2 to 4, which is comparable to other oral brand name options.

Research looks at CV outcomes and cancer risk

Cardiovascular (CV) risk reduction. To date, only one study evaluating the effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on CV outcomes is complete.33 Two large randomized controlled trials involving canagliflozin and dapagliflozin designed to evaluate treatment effects on major CV endpoints are ongoing.34,35

In the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial,33 researchers found that empagliflozin had beneficial effects on CV outcomes, making it one of the only antidiabetic agents on the market to have such benefits. The study, which involved more than 7000 patients with a history of T2DM and existing cardiovascular disease (CVD), found that 10.5% of patients in the empagliflozin group vs 12.1% in the placebo group died from a CV cause or experienced a nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke over a median of 3.1 years. Results were similar with both doses (10 mg vs 25 mg) of empagliflozin. The mechanisms behind the CV benefits are likely multifactorial and may be related to reductions in weight and BP,33 but additional research is needed to fully elucidate the role of empagliflozin in this population.

Canagliflozin is being evaluated in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) for its effect on major CV events—CV death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke—in patients with either a history of CVD or who are at increased risk of CVD and have uncontrolled diabetes.34 The trial is expected to wrap up in June 2017.

And dapagliflozin is being studied in the DECLARE-TIMI 58 trial (the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events) in patients with T2DM and either known CVD or at least 2 risk factors for CVD.35 The study is designed to assess dapagliflozin’s effect on the incidence of CV death, myocardial infarction, and ischemic stroke and has an estimated completion date of April 2019, which will provide a median follow-up of 4.5 years.

Cancer. All 3 agents have been examined for any possible carcinogenic links. In 2011, the FDA issued a request for further investigation surrounding the risk of cancer associated with dapagliflozin.36 As of November 2013, 10 of 6045 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed bladder cancer compared to 1 of 3512 controls.36 Furthermore, 9 of 2223 patients treated with dapagliflozin developed breast cancer compared to 1 of 1053 controls.36

Although the trials were not designed to detect an increase in risk, the number of observed cases warranted further investigation. No official warning for breast cancer exists since the characteristics of the malignancies led the FDA to believe dapagliflozin was unlikely the cause.36

Given what we know to date, it appears to be prudent to avoid prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with active bladder cancer, and to use them with caution in those with a history of the disease.2

Other studies. Initially, animal studies suggested an increased risk of various malignancies associated with canagliflozin use in rats,37 but consistent results were not seen in human studies. Similarly, at least one study found that empagliflozin was associated with lung cancer and melanoma, but closer examination found that most patients who developed these cancers had risk factors.38 Large, long-term studies of these agents in various populations are needed to thoroughly investigate possible carcinogenicity.

Additional considerations: Kidney function, age, and pregnancy

Consider avoiding SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with moderate kidney dysfunction (eGFR 30-59 mL/min/1.73 m2). Studies have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors are not as effective at lowering blood glucose in those with reduced eGFR, although adverse events were similar to those in placebo groups.24,39,40 Dapagliflozin is not recommended in patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 due to lack of efficacy.2,24 Empagliflozin does not require dose adjustments if eGFR is ≥45 mL/min/1.73 m2. A lower dose of canagliflozin (ie, 100 mg/d) is recommended in those with an eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2.2 All agents are contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment (eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Older patients are at higher risk for dehydration, hypotension, and falls; therefore, SGLT2 inhibitors should be used with caution in this population. Similarly, they should not be used in patients with T1DM and should be avoided in those with active, or a history of, DKA.

There are no data on the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in pregnancy; thus, these agents should be avoided unless the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks to the unborn fetus.2

CASE 1 › An SGLT2 inhibitor is an acceptable option for Mr. S. Because he is resistant to starting insulin therapy and his HbA1c is <9%, an additional oral medication is reasonable. Adding an SGLT2 inhibitor may reduce his HbA1c up to ~1%, and education on lifestyle modifications may help bring him to goal. An SGLT2 inhibitor may also benefit his BP and weight, both of which could be improved.

Given the drugs he’s taking, drug interactions should not be an issue, and his renal function and pertinent labs (K, Phos, Mg) are within normal limits. Nevertheless, monitor these labs periodically and monitor Mr. S for adverse effects, such as UTIs, although these are more common in women. Canagliflozin is the preferred SGLT2 inhibitor on his insurance formulary, so you could initiate therapy at 100 mg/d, administered prior to the first meal, and increase to 300 mg/d if needed. As an alternative, consider prescribing the metformin/canagliflozin combination agent.

CASE 2 › Ms. R is likely experiencing a yeast infection as an adverse effect of the dapagliflozin. Although one yeast infection is insufficient grounds for discontinuation of the drug, recurrent infections should prompt a risk-to-benefit analysis to determine whether it’s worth continuing the medication. Her recent eGFR (<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) is, however, a contraindication to dapagliflozin, and therapy should be discontinued. Canagliflozin and empagliflozin may be considered since her eGFR is >45 mL/min/1.73 m2, but given her current HbA1c and recent adverse drug event, alternative therapies, such as basal insulin, are more appropriate treatment choices.

CORRESPONDENCE

Katelin M. Lisenby, PharmD, BCPS, University of Alabama College of Community Health Sciences, University Medical Center, Box 870374, Tuscaloosa, AL 35487; kmh0003@auburn.edu.

› Consider sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line agents in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who need mild hemoglobin A1c reductions (≤1%) and who would benefit from mild to modest weight and blood pressure reductions. A

› Avoid using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with a history of recurrent genital mycotic or urinary tract infections. B

› Use SGLT2 inhibitors with caution in patients at risk for volume-related adverse effects (dizziness and hypotension), such as the elderly, those with moderate renal dysfunction, and those taking concomitant diuretic therapy. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE 1 › Joe S is a 41-year-old African-American man who comes to your clinic after his employee health screening revealed elevated triglycerides. The patient has a 3-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM); he also has a history of hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obstructive sleep apnea. Mr. S tells you he takes metformin 1000 mg twice daily, but stopped taking his glipizide because he didn’t think it was helping his blood sugar. His last hemoglobin (Hb) A1c result was 8.8%, and he is very resistant to starting insulin therapy.

The patient’s other medications include enalapril 10 mg/d, atorvastatin 10 mg/d, and omeprazole 20 mg/d. Mr. S weighs 255.6 lbs (body mass index=34.7), his BP is 140/88 mm Hg, and his heart rate is 82 beats per minute. Laboratory values include: serum creatinine, 1.01 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) >100 mL/min/1.73 m2; potassium (K), 4.3 mmol/L; serum phosphorous (Phos), 2.8 mg/dL; magnesium (Mg), 1.9 mg/dL; total cholesterol, 167 mg/dL; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 78 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 38 mg/dL; and triglycerides, 256 mg/dL.

CASE 2 › Susan R, a 68-year-old Caucasian woman, returns to your clinic for a follow-up visit 3 months after you prescribed dapagliflozin 10 mg/d for her T2DM. Her glucose levels have improved, but she complains of vaginal pruritus and is worried that she has a yeast infection.

You diagnose vulvovaginal candidiasis in this patient and prescribe a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg. After reviewing her laboratory test results, you notice that since starting the dapagliflozin, her HbA1c level has improved slightly from 9.8% to 9.3%, but is still not where it needs to be. Her eGFR is 49 mL/min/1.73 m2.

What would you recommend to improve control of these patients’ blood glucose levels?

When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor

Consider therapy with SGLT2 inhibitors in adult patients with T2DM who:3-9,13-15,17-24

- have an HbA1c between 7% and 9%

- would benefit from weight and/or blood pressure reductions

- have metabolic syndrome

- have adequate means to pay for the medication (ie, prescription coverage or the ability to afford it).

In addition, consider an SGLT2 inhibitor as initial monotherapy if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated, or as add-on therapy to metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, or insulin.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are the newest class of agents to enter the T2DM management arena. They act in the proximal renal tubules to decrease the reabsorption of glucose by targeting the SGLT2 transmembrane protein, which reabsorbs about 90% of the body’s glucose.1,2 The class is currently made up of 3 agents—canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin—all of which are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of T2DM (TABLE 1).2

The American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes published updated guidelines for T2DM management in 2015.1 In addition to lifestyle modifications, the guidelines recommend the use of metformin as first-line therapy unless it is contraindicated or patients are unable to tolerate it (eg, because of gastrointestinal adverse effects). They recommend other pharmacologic therapies as second-line options based on specific patient characteristics. Thus, SGLT2 inhibitors may be used as add-on therapy after metformin, or as a first-line option if metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Because the mechanism of action of SGLT2 inhibitors is independent of insulin secretion, these agents may be used at any stage of the diabetes continuum.

SGLT2 agents as monotherapy, or as add-on therapy

All SGLT2 agents have been studied as monotherapy accompanied by diet and exercise and shown to produce HbA1c reductions of 0.34% to 1.11%.3-6 In trials, the effect was similar regardless of study duration (18-104 weeks); generally, higher doses corresponded with larger HbA1c reductions.3-6

SGLT2 inhibitors have also been studied as add-on therapy to several oral agents including metformin, sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), and the combination of metformin plus sulfonylureas or TZDs or dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors.1 When used in any of these combinations, each SGLT2 agent demonstrated a consistent HbA1c lowering effect of 0.62% to 1.19%.7-14

Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors have been studied in combination with insulin therapy (median or mean daily doses >60 units), which yielded further reductions in HbA1c of 0.58% to 1.02% without significant insulin adjustments or an increase in major hypoglycemia events.15-17 Patients receiving insulin and an SGLT2 inhibitor had lower insulin doses and more weight loss compared to placebo groups.

SGLT2 inhibitors offer additional benefits

Secondary analyses of most studies of SGLT2 inhibitors include changes in BP and weight from baseline as well as minor changes (some positive, some not) in several lipid parameters.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 In general, these effects do not appear to be dose-dependent (with the exception of canagliflozin and its associated lipid effects25) and are similar among the 3 medications.3-5,7-9,13-15,17-24 (For more on who would benefit from these agents, see “When to consider an SGLT2 inhibitor” above.)

BP reduction. Although the mean baseline BP was controlled in most studies, SGLT2 inhibitors have been shown to significantly reduce BP. Reductions in BP with all 3 SGLT2 medications range from approximately 2 to 5 mm Hg systolic and 0.5 to 2.5 mm Hg diastolic, which may be due to weight loss and diuresis.4-8,10-16,20-23 While the reductions were modest at best, one study involving empagliflozin reported that more than one-quarter of patients with uncontrolled BP at baseline achieved a BP <130/80 mm Hg 24 weeks later.5 While these agents should not be used solely for their BP lowering effects, they may help a small number of patients with mildly elevated BP achieve their goal without an additional antihypertensive agent.

Weight reduction. Modest weight loss, likely due to the loss of calories through urine, was seen with SGLT2 inhibitors in most studies, with reductions persisting beyond one year of use. In most studies, including those involving obese patients on insulin therapy,15,17,21 patients’ body weights were reduced by approximately 2 to 4 kg from baseline.3-16,18,21-23,26

Lipid effects. Although the mechanism is unclear, use of SGLT2 inhibitors can have varying effects on lipid panels. In most studies, total and LDL cholesterol levels were increased with elevations ranging from 0.7 to 10 mg/dL.3,7,8,18,19,22,23 Conversely, at least one study demonstrated mild reductions in total and LDL cholesterol levels with higher doses of empagliflozin.13 Additionally, modest reductions in triglycerides and increases in HDL across all doses of canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin have been seen.8,9,13,15,19 While the clinical relevance of these lipid changes is unknown, monitoring is recommended.2

These agents are well tolerated