User login

Gemtuzumab ozogamycin heightens risk for toxicities with no survival benefit in de novo AML

Key clinical point: The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamycin (GO) to standard chemotherapy (SC) did not improve survival in younger patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and intermediate-risk (IR) cytogenetics but was associated with significantly higher toxicities.

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 35 months, event-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .116) and overall survival (HR, 1.35; P = .146) were not different in patients receiving GO+SC vs. SC alone. Duration of neutropenia (P = .03) and thrombopenia (P less than .001) and grade 3/4 liver toxicities (P = .03) were significantly higher in patients receiving GO vs. SC alone.

Study details: Phase 3 AML 2006-IR trial included 238 younger patients (age, 18-60 years) with de novo AML and IR cytogenetics randomly assigned to receive cytarabine and daunorubicin with or without GO. GO arm was prematurely closed after 254 inclusions because of toxicity and early deaths.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the French government PHRC 2006 and PFIZER group. Some investigators reported being on advisory boards, receiving research and travel funding, honoraria, and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

Source: Bouvier A et al. Eur J Haematol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13626.

Key clinical point: The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamycin (GO) to standard chemotherapy (SC) did not improve survival in younger patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and intermediate-risk (IR) cytogenetics but was associated with significantly higher toxicities.

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 35 months, event-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .116) and overall survival (HR, 1.35; P = .146) were not different in patients receiving GO+SC vs. SC alone. Duration of neutropenia (P = .03) and thrombopenia (P less than .001) and grade 3/4 liver toxicities (P = .03) were significantly higher in patients receiving GO vs. SC alone.

Study details: Phase 3 AML 2006-IR trial included 238 younger patients (age, 18-60 years) with de novo AML and IR cytogenetics randomly assigned to receive cytarabine and daunorubicin with or without GO. GO arm was prematurely closed after 254 inclusions because of toxicity and early deaths.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the French government PHRC 2006 and PFIZER group. Some investigators reported being on advisory boards, receiving research and travel funding, honoraria, and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

Source: Bouvier A et al. Eur J Haematol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13626.

Key clinical point: The addition of gemtuzumab ozogamycin (GO) to standard chemotherapy (SC) did not improve survival in younger patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and intermediate-risk (IR) cytogenetics but was associated with significantly higher toxicities.

Major finding: During a median follow-up of 35 months, event-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; P = .116) and overall survival (HR, 1.35; P = .146) were not different in patients receiving GO+SC vs. SC alone. Duration of neutropenia (P = .03) and thrombopenia (P less than .001) and grade 3/4 liver toxicities (P = .03) were significantly higher in patients receiving GO vs. SC alone.

Study details: Phase 3 AML 2006-IR trial included 238 younger patients (age, 18-60 years) with de novo AML and IR cytogenetics randomly assigned to receive cytarabine and daunorubicin with or without GO. GO arm was prematurely closed after 254 inclusions because of toxicity and early deaths.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the French government PHRC 2006 and PFIZER group. Some investigators reported being on advisory boards, receiving research and travel funding, honoraria, and personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

Source: Bouvier A et al. Eur J Haematol. 2021 Mar 25. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13626.

Does depth of clinical response pre-HCT affect posttransplant survival in AML?

Key clinical point: In patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), incomplete count recovery (CRi) or presence of measurable residual disease (MRD) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) was associated with inferior posttransplant outcomes vs. those in complete remission (CR) or without MRD.

Major finding: Patients in CRi vs. CR were at a higher risk for death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.27; P less than .001) and nonrelapse mortality (HR, 1.33; P = .002). Additionally, presence vs. absence of MRD was associated with shorter overall survival (HR, 1.52; P less than .001) and increased relapse (HR, 1.78; P less than .001).

Study details: This observational study included 2,492 adult patients with AML (CR, n=1,799; CRi, n=693) from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (CIBMTR) registry, who underwent first allo-HCT between 2007 and 2015.

Disclosures: CIBMTR is primarily supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Office of Naval Research. The lead author had no disclosures. Some coinvestigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Percival ME et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01261-6.

Key clinical point: In patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), incomplete count recovery (CRi) or presence of measurable residual disease (MRD) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) was associated with inferior posttransplant outcomes vs. those in complete remission (CR) or without MRD.

Major finding: Patients in CRi vs. CR were at a higher risk for death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.27; P less than .001) and nonrelapse mortality (HR, 1.33; P = .002). Additionally, presence vs. absence of MRD was associated with shorter overall survival (HR, 1.52; P less than .001) and increased relapse (HR, 1.78; P less than .001).

Study details: This observational study included 2,492 adult patients with AML (CR, n=1,799; CRi, n=693) from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (CIBMTR) registry, who underwent first allo-HCT between 2007 and 2015.

Disclosures: CIBMTR is primarily supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Office of Naval Research. The lead author had no disclosures. Some coinvestigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Percival ME et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01261-6.

Key clinical point: In patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), incomplete count recovery (CRi) or presence of measurable residual disease (MRD) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) was associated with inferior posttransplant outcomes vs. those in complete remission (CR) or without MRD.

Major finding: Patients in CRi vs. CR were at a higher risk for death (hazard ratio [HR], 1.27; P less than .001) and nonrelapse mortality (HR, 1.33; P = .002). Additionally, presence vs. absence of MRD was associated with shorter overall survival (HR, 1.52; P less than .001) and increased relapse (HR, 1.78; P less than .001).

Study details: This observational study included 2,492 adult patients with AML (CR, n=1,799; CRi, n=693) from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (CIBMTR) registry, who underwent first allo-HCT between 2007 and 2015.

Disclosures: CIBMTR is primarily supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Office of Naval Research. The lead author had no disclosures. Some coinvestigators reported ties with various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Percival ME et al. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021 Apr 16. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01261-6.

Pediatric AML: Gemtuzumab ozogamicin prior to allo-HCT increases risk for veno-occlusive disease

Key clinical point: Prior treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) increased risk for veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS) but did not affect survival.

Major finding: Compared with nonexposure, exposure to GO was associated with increased risk for VOD/SOS at 100 days (odds ratio, 2.26; P = .004). However, posttransplant overall survival (P = .43), disease-free survival (P = .20), relapse (P = .32), and nonrelapse mortality (P = .51) did not differ in patients with or without prior GO treatment.

Study details: Findings are from retrospective assessment of pediatric patients with AML who received myeloablative allo-HCT between 2008 and 2011 with (n=148) or without (n=348) prior GO treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer. D Chirnomas, CJ Hoang, and FR Loberiza Jr declared being current/former employees of and/or had equity ownership in Pfizer. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Duncan C et al. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021 Apr 19. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29067.

Key clinical point: Prior treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) increased risk for veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS) but did not affect survival.

Major finding: Compared with nonexposure, exposure to GO was associated with increased risk for VOD/SOS at 100 days (odds ratio, 2.26; P = .004). However, posttransplant overall survival (P = .43), disease-free survival (P = .20), relapse (P = .32), and nonrelapse mortality (P = .51) did not differ in patients with or without prior GO treatment.

Study details: Findings are from retrospective assessment of pediatric patients with AML who received myeloablative allo-HCT between 2008 and 2011 with (n=148) or without (n=348) prior GO treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer. D Chirnomas, CJ Hoang, and FR Loberiza Jr declared being current/former employees of and/or had equity ownership in Pfizer. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Duncan C et al. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021 Apr 19. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29067.

Key clinical point: Prior treatment with gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO) before allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) increased risk for veno-occlusive disease/sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (VOD/SOS) but did not affect survival.

Major finding: Compared with nonexposure, exposure to GO was associated with increased risk for VOD/SOS at 100 days (odds ratio, 2.26; P = .004). However, posttransplant overall survival (P = .43), disease-free survival (P = .20), relapse (P = .32), and nonrelapse mortality (P = .51) did not differ in patients with or without prior GO treatment.

Study details: Findings are from retrospective assessment of pediatric patients with AML who received myeloablative allo-HCT between 2008 and 2011 with (n=148) or without (n=348) prior GO treatment.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer. D Chirnomas, CJ Hoang, and FR Loberiza Jr declared being current/former employees of and/or had equity ownership in Pfizer. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Duncan C et al. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021 Apr 19. doi: 10.1002/pbc.29067.

De novo AML: Data spanning 4 decades show significant improvement in outcomes

Key clinical point: Survival outcomes have improved significantly in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) over a 4-decade period from 1980 to 2017; however, least improvement was observed in patients aged 70 years or older.

Major finding: Overall, 5-year survival increased from 9% during 1980-1989 to 15% in 1990-1999, 22% in 2000-2009, and 28% in 2010-2017 (all P less than .001). However, improvement in 5-year survival was poorest in patients aged 70 years or older with 1% in 1980-1989 to 5% in 2010-2017.

Study details: Findings are from a U.S. population-based study that evaluated 29,107 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, who were diagnosed with de novo AML between 1980 and 2017.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. Some investigators including the lead author reported personal fees, research funding, honoraria, or other support from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Sasaki K et al. Cancer. 2021 Apr 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33458.

Key clinical point: Survival outcomes have improved significantly in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) over a 4-decade period from 1980 to 2017; however, least improvement was observed in patients aged 70 years or older.

Major finding: Overall, 5-year survival increased from 9% during 1980-1989 to 15% in 1990-1999, 22% in 2000-2009, and 28% in 2010-2017 (all P less than .001). However, improvement in 5-year survival was poorest in patients aged 70 years or older with 1% in 1980-1989 to 5% in 2010-2017.

Study details: Findings are from a U.S. population-based study that evaluated 29,107 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, who were diagnosed with de novo AML between 1980 and 2017.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. Some investigators including the lead author reported personal fees, research funding, honoraria, or other support from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Sasaki K et al. Cancer. 2021 Apr 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33458.

Key clinical point: Survival outcomes have improved significantly in patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML) over a 4-decade period from 1980 to 2017; however, least improvement was observed in patients aged 70 years or older.

Major finding: Overall, 5-year survival increased from 9% during 1980-1989 to 15% in 1990-1999, 22% in 2000-2009, and 28% in 2010-2017 (all P less than .001). However, improvement in 5-year survival was poorest in patients aged 70 years or older with 1% in 1980-1989 to 5% in 2010-2017.

Study details: Findings are from a U.S. population-based study that evaluated 29,107 patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registries, who were diagnosed with de novo AML between 1980 and 2017.

Disclosures: No funding source was identified. Some investigators including the lead author reported personal fees, research funding, honoraria, or other support from various pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Sasaki K et al. Cancer. 2021 Apr 5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33458.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: AML May 2021

Two recently published studies added to our knowledge on the clinical benefit of gemtuzumab in patients with AML. The first study by Bouvier A et al demonstrated no survival benefit with the addition of gemtuzumab in patients with intermediate risk AML. The second study by Duncan et al was a retrospective study by the CIBMTR. That study demonstrated increased risk of VOD in pediatric patients who received gemtuzmab. However, overall survival and event free survival was similar in both groups. These results highlight the need for increased awareness post-transplant for the possibility of VOD, and also reduces concern regarding overall survival for patients receiving gemtuzumab.

Another study by the EBMT (Debaja et al) evaluated factors affecting the outcome of patients with AML receiving a second allogeneic HCT. Outcome was worse for patients not in CR and those with a short time from allo-HCT. Overall survival was similar for patients receiving a MUD or haploidentical donor. Two year overall survival was 31% vs. 29% for patients receiving MUD vs. haploidentical allo-HCT. This study clearly expands options for patients receiving a second allo-HCT. In addition, a prior study by EBMT demonstrated no difference in overall survival between patients receiving same vs. different vs. haplo donor.

Finally, a large study by the CIBMTR (Percival et al) demonstrated that in AML patients, achieving CRi and having persistent MRD prior to transplantation were associated with worse outcome compared to CR with no evidence of MRD. The adjusted 5 year survival for patient with CR/MRD-ve, CR/MRD+ve, CRi/MRD-ve and CRi/MRD+ve was 52%, 37%, 44% and 34% respectively.

Two recently published studies added to our knowledge on the clinical benefit of gemtuzumab in patients with AML. The first study by Bouvier A et al demonstrated no survival benefit with the addition of gemtuzumab in patients with intermediate risk AML. The second study by Duncan et al was a retrospective study by the CIBMTR. That study demonstrated increased risk of VOD in pediatric patients who received gemtuzmab. However, overall survival and event free survival was similar in both groups. These results highlight the need for increased awareness post-transplant for the possibility of VOD, and also reduces concern regarding overall survival for patients receiving gemtuzumab.

Another study by the EBMT (Debaja et al) evaluated factors affecting the outcome of patients with AML receiving a second allogeneic HCT. Outcome was worse for patients not in CR and those with a short time from allo-HCT. Overall survival was similar for patients receiving a MUD or haploidentical donor. Two year overall survival was 31% vs. 29% for patients receiving MUD vs. haploidentical allo-HCT. This study clearly expands options for patients receiving a second allo-HCT. In addition, a prior study by EBMT demonstrated no difference in overall survival between patients receiving same vs. different vs. haplo donor.

Finally, a large study by the CIBMTR (Percival et al) demonstrated that in AML patients, achieving CRi and having persistent MRD prior to transplantation were associated with worse outcome compared to CR with no evidence of MRD. The adjusted 5 year survival for patient with CR/MRD-ve, CR/MRD+ve, CRi/MRD-ve and CRi/MRD+ve was 52%, 37%, 44% and 34% respectively.

Two recently published studies added to our knowledge on the clinical benefit of gemtuzumab in patients with AML. The first study by Bouvier A et al demonstrated no survival benefit with the addition of gemtuzumab in patients with intermediate risk AML. The second study by Duncan et al was a retrospective study by the CIBMTR. That study demonstrated increased risk of VOD in pediatric patients who received gemtuzmab. However, overall survival and event free survival was similar in both groups. These results highlight the need for increased awareness post-transplant for the possibility of VOD, and also reduces concern regarding overall survival for patients receiving gemtuzumab.

Another study by the EBMT (Debaja et al) evaluated factors affecting the outcome of patients with AML receiving a second allogeneic HCT. Outcome was worse for patients not in CR and those with a short time from allo-HCT. Overall survival was similar for patients receiving a MUD or haploidentical donor. Two year overall survival was 31% vs. 29% for patients receiving MUD vs. haploidentical allo-HCT. This study clearly expands options for patients receiving a second allo-HCT. In addition, a prior study by EBMT demonstrated no difference in overall survival between patients receiving same vs. different vs. haplo donor.

Finally, a large study by the CIBMTR (Percival et al) demonstrated that in AML patients, achieving CRi and having persistent MRD prior to transplantation were associated with worse outcome compared to CR with no evidence of MRD. The adjusted 5 year survival for patient with CR/MRD-ve, CR/MRD+ve, CRi/MRD-ve and CRi/MRD+ve was 52%, 37%, 44% and 34% respectively.

Clinical Use of a Diagnostic Gene Expression Signature for Melanocytic Neoplasms

According to National Institutes of Health estimates, more than 90,000 new cases of melanoma were diagnosed in 2018.1 Overall 5-year survival for patients with melanoma exceeds 90%, but individual survival estimates are highly dependent on stage at diagnosis, and survival decreases markedly with metastasis. Therefore, early and accurate diagnosis is critical.

Diagnosis of melanocytic neoplasms usually is performed by dermatopathologists through microscopic examination of stained tissue biopsy sections, a technically simple and effective method that enables a definitive diagnosis of benign nevus or malignant melanoma to be made in most cases. However, approximately 15% of all biopsied melanocytic lesions will exhibit some degree of histopathologic ambiguity,2-4 meaning that some of their microscopic features will be characteristic of a benign nevus while others will suggest the possibility of malignant melanoma. Diagnostic interpretations often vary in these cases, even among experts, and a definitive diagnosis of benign or malignant may be difficult to achieve by microscopy alone.2-4 Because of the marked reduction in survival once a melanoma has metastasized, these diagnostically ambiguous lesions often are treated as possible malignant melanomas with complete surgical excision (or re-excision). However, some experts suggest that many histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms are, in fact, benign,5 a notion supported by epidemiologic evidence.6,7 Therefore, excision of many ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms might be avoided if definitive diagnosis could be achieved.

A gene expression signature was developed and validated for use as an adjunct to traditional methods of differentiating malignant melanocytic neoplasms from their benign counterparts.8-11 This test quantifies the RNA transcripts produced by 14 genes known to be overexpressed in malignant melanomas by comparison to benign nevi. These values are then combined algorithmically with measurements of 9 reference genes to produce an objective numerical score that is classified as benign, malignant, or indeterminate. When used by board-certified dermatopathologists and dermatologists confronting ambiguous melanocytic lesions, the test produces substantial increases in definitive diagnoses and prompts changes in treatment recommendations.12,13 However, the long-term consequences of foregoing surgical excision of melanocytic neoplasms that are diagnostically ambiguous but classified as benign by this test have not yet been formally assessed. In the current study, prospectively tested patients whose ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms were classified as benign by the gene expression signature were followed for up to 4.5 years to evaluate the long-term safety of treatment decisions aligned with benign test results.

Methods

Study Population

As part of a prior study,12 US-based dermatopathologists submitted tissue sections from biopsied melanocytic neoplasms determined to be diagnostically ambiguous by histopathology for analysis with the gene expression signature (Myriad Genetics, Inc). Diagnostically ambiguous lesions were those lesions that were described as ambiguous, uncertain, equivocal, indeterminate, or other synonymous terms by the submitting dermatopathologist and therefore lacked a confident diagnosis of benign or malignant prior to testing. Patients initially were tested between May 2014 and August 2014, with samples submitted through a prospective clinical experience study designed to assess the impact of the test on diagnosis and treatment decisions. This study was performed under an institutional review board waiver of consent (Quorum #33403/1).

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the current study if their biopsy specimens (1) had an uncertain preliminary diagnosis according to the submitting dermatopathologist (pretest diagnosis of indeterminate); (2) received a negative (benign) score from the gene expression test; (3) were treated as benign by the dermatologist(s) involved in follow-up care; and (4) were submitted by a single site (St. Joseph Medical Center, Houston, Texas). Although a single dermatopathology site was used for this study, multiple dermatologists were involved in the final treatment of these patients. Patients with benign scores who received additional intervention were excluded, as they may have a lower rate of adverse events (ie, metastasis) than those who did not receive intervention and would therefore skew the analysis population. A total of 25 patients from the prior study met these inclusion criteria. The previously collected12 pretest and posttest de-identified data were compiled from the commercial laboratory databases, and the patients were followed from the time of testing via medical record review performed by the dermatology providers at participating sites. Clinical follow-up data were collected using study-specific case report forms (CRFs) that captured the following: (1) the dates and results of clinical follow-up visits; (2) the type(s) of treatment and interventions (if any) performed at those visits; (3) the specific indication for any intervention performed; (4) any evidence of persistent, locally recurrent, and/or distant melanocytic neoplasia (whether definitively attributable to the tested lesion or not); and (5) death from any cause. The CRF assigned interventions to 1 of 5 categories: excision, excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, referral to dermatologic or other surgeon, examination only (without surgical intervention), and other. Selection of other required a free-text description of the treatment and indications. Pertinent information not otherwise captured by the CRF also was recordable as free text.

Gene Expression Testing

Gene expression testing was carried out at the time of specimen submission in the prior study12 as described previously.14 Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, unstained tissue sections and/or tissue blocks were submitted for testing along with a single hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide used to identify and designate the representative portion(s) of the lesion to be tested. These areas were macrodissected from unstained tissue sections and pooled for RNA extraction. Expression of 14 biomarker genes and 9 reference genes was measured via

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and other baseline characteristics of the patient population were summarized. Follow-up time was calculated as the interval between the date a patient’s gene expression test result was first issued to the provider and the date of the patient’s last recorded visit during the study period. All patient dermatology office visits within the designated follow-up period were documented, with a nonstandard number of visits and follow-up time across all study patients. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc), R software version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and IBM SPSS Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25).

Results

Patient Sample

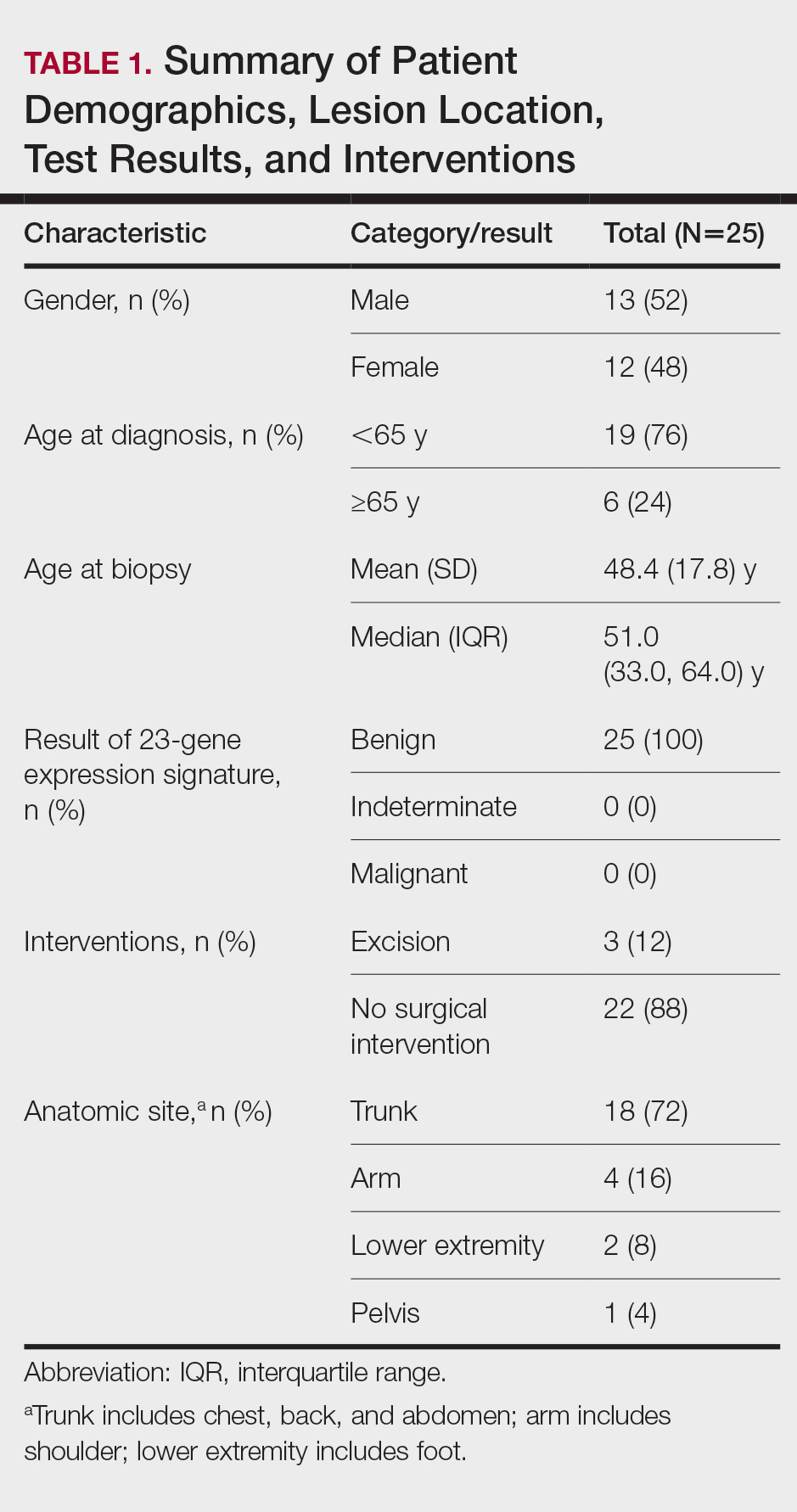

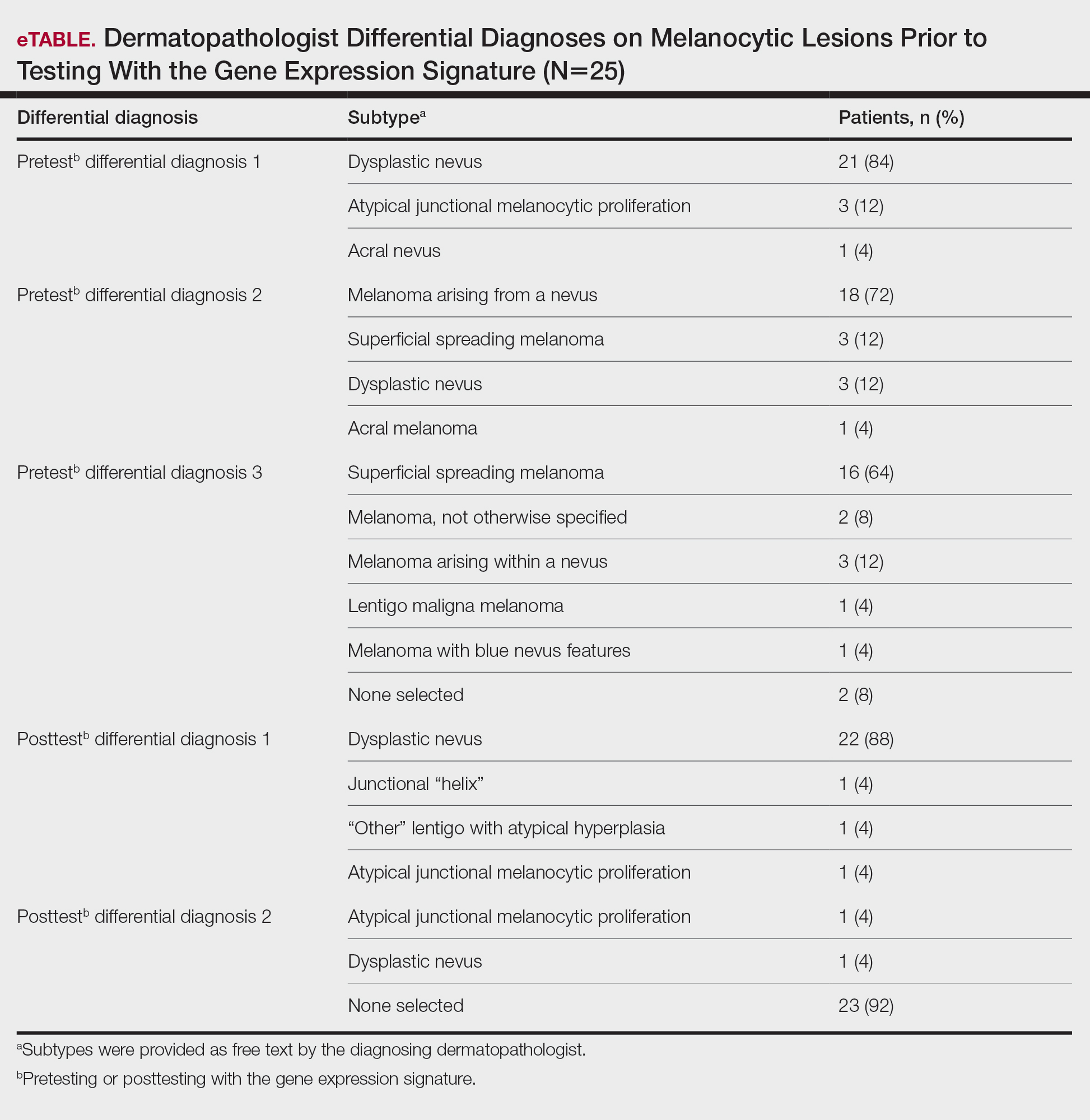

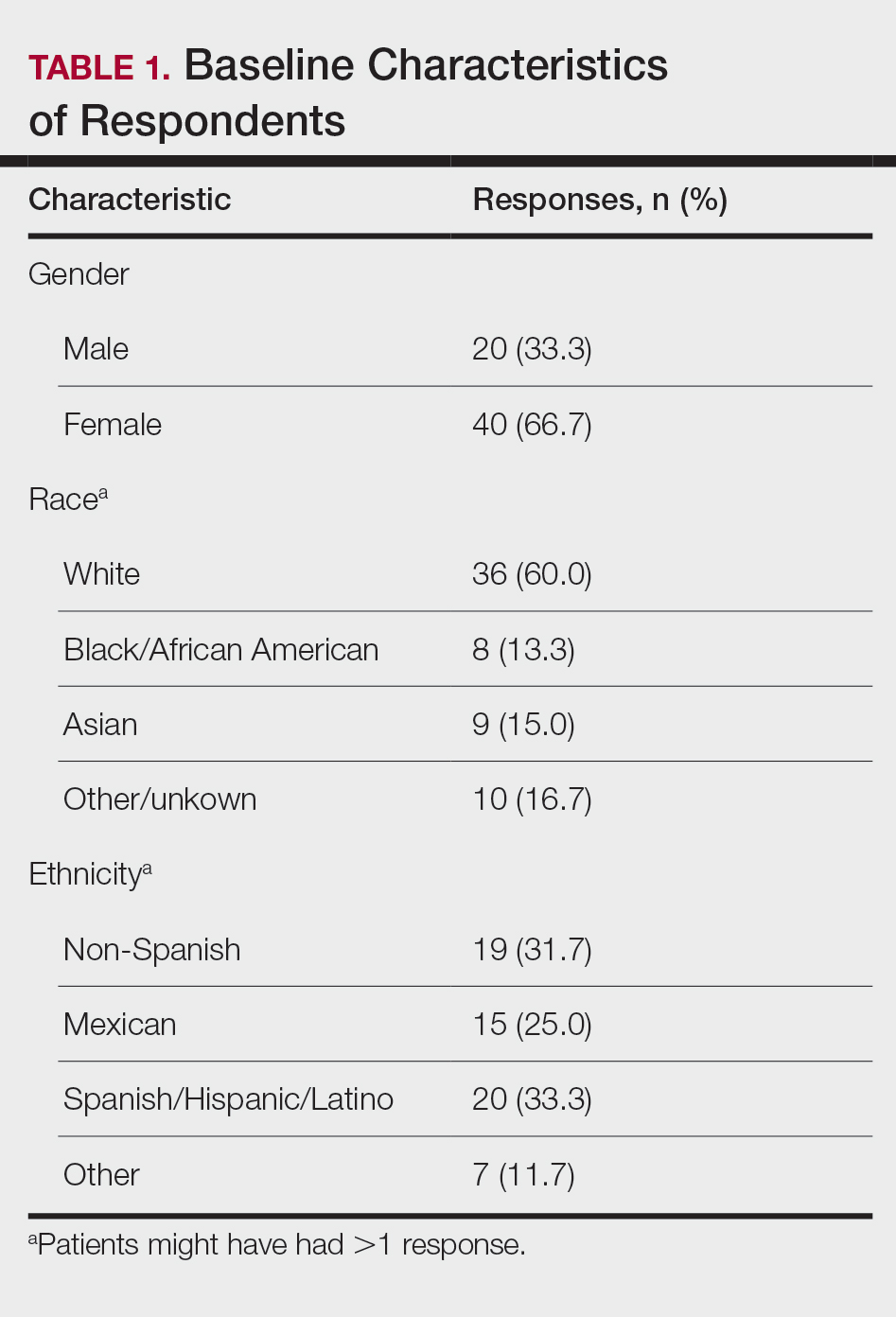

A total of 25 ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms from 25 patients met the study inclusion criteria of a benign gene expression result with subsequent treatment as a benign neoplasm during follow-up. The patient sample statistics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients were younger than 65 years, with an average age at the time of biopsy of 48.4 years. All 25 neoplasms produced negative (benign) gene expression signature scores, all were diagnosed as benign nevi posttest by the submitting dermatopathologist, and all patients were initially treated in accordance with the benign diagnosis by the dermatologist(s) involved in clinical follow-up care. Prior to testing with the gene expression signature, most of these histopathologically indeterminate lesions received differential diagnoses, the most common of which were dysplastic nevus (84%), melanoma arising from a nevus (72%), and superficial spreading melanoma (64%; eTable). After testing with the gene expression signature and receiving a benign score, most lesions received a single differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus (88%).

Follow-up and Survival

Clinical follow-up time ranged from 0.6 to 53.3 months, with a mean duration (SD) of 38.5 (16.6) months, and patients attended an average of 4 postbiopsy dermatology appointments (mean [SD], 4.6 [3.6]). According to the participating dermatology care providers, none of the 25 patients developed any indication during follow-up that the diagnosis of benign nevus was inaccurate. No patient had evidence of locally recurrent or metastatic melanoma, and none died during the study period.

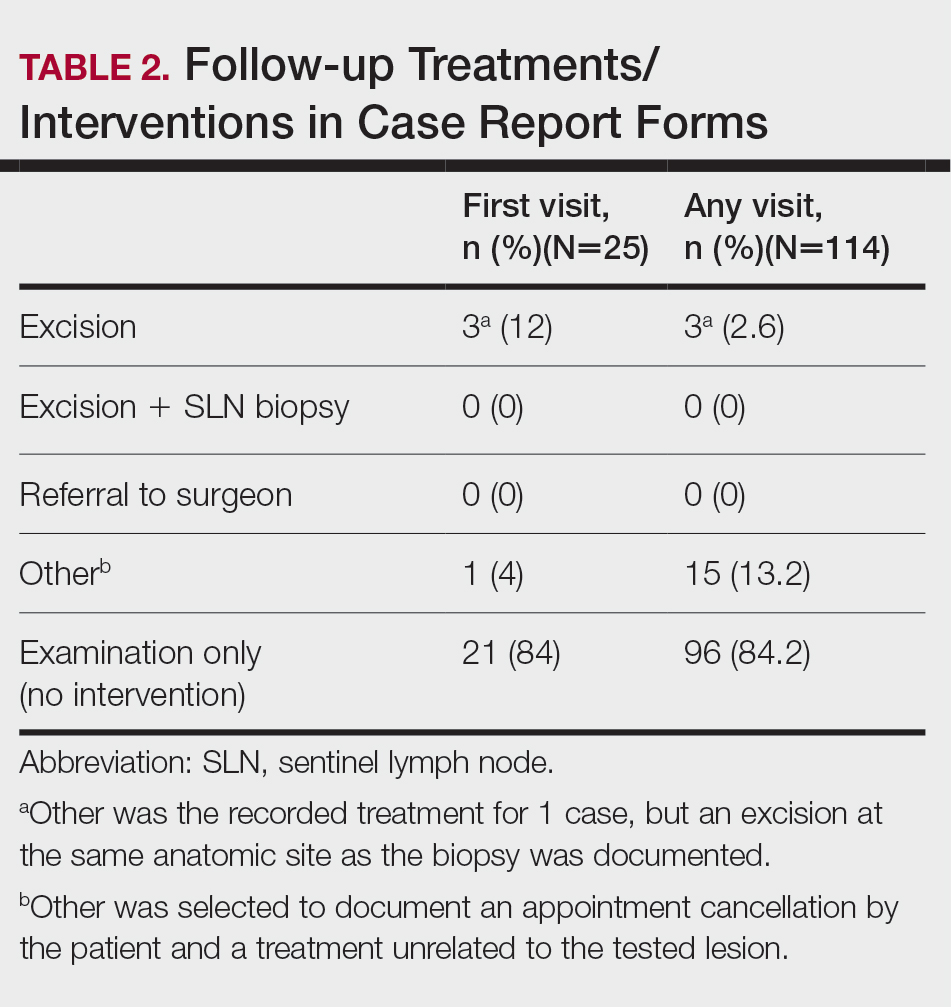

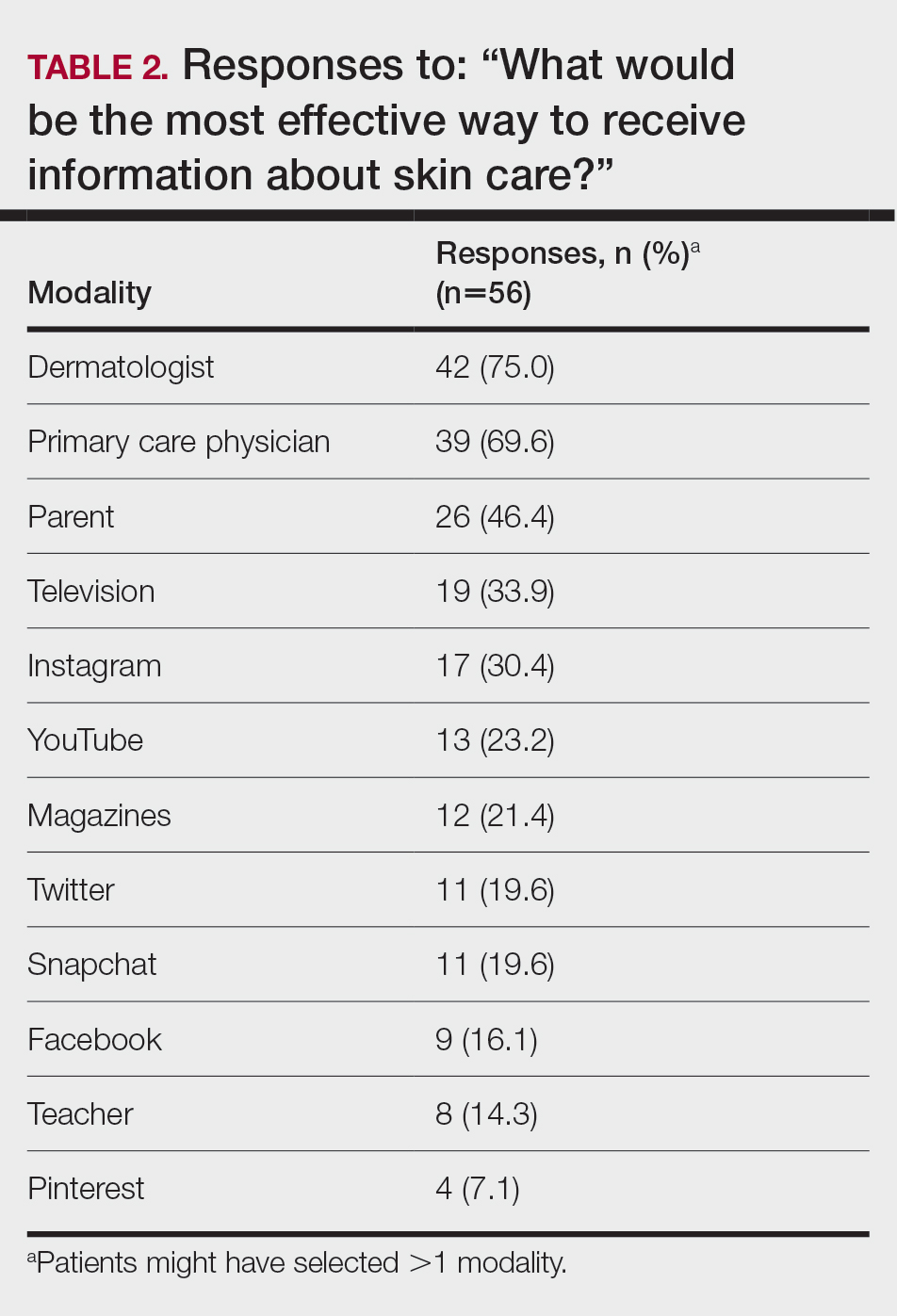

Treatment/Interventions

The treatment recorded in the CRF was examination only for 21 of 25 patients, excision for 3, and other for 1 (Table 2). Because the explanation for the selection of other in this case described an excision performed at the same anatomic location as the biopsy, this treatment also was considered an excision for purposes of the study analyses. The 3 excisions all occurred at the first postbiopsy dermatology encounter. Across all follow-up visits, no additional surgical interventions occurred (Table 2).

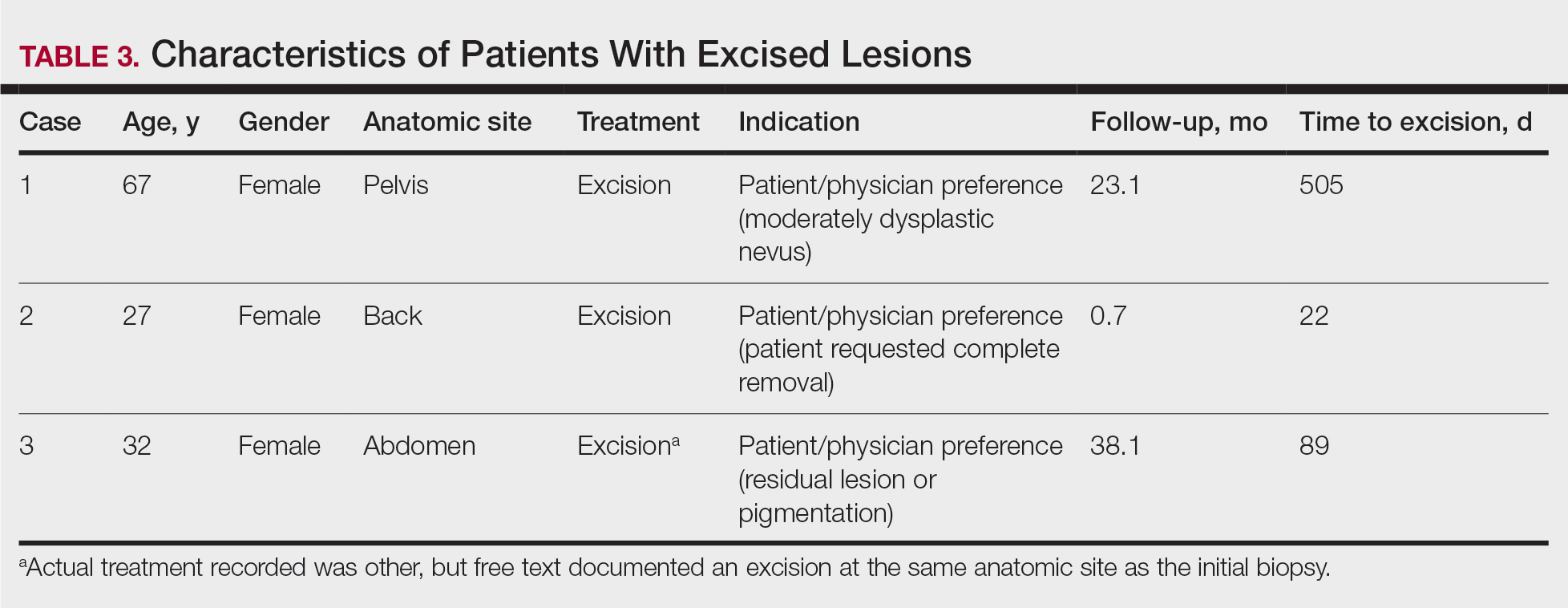

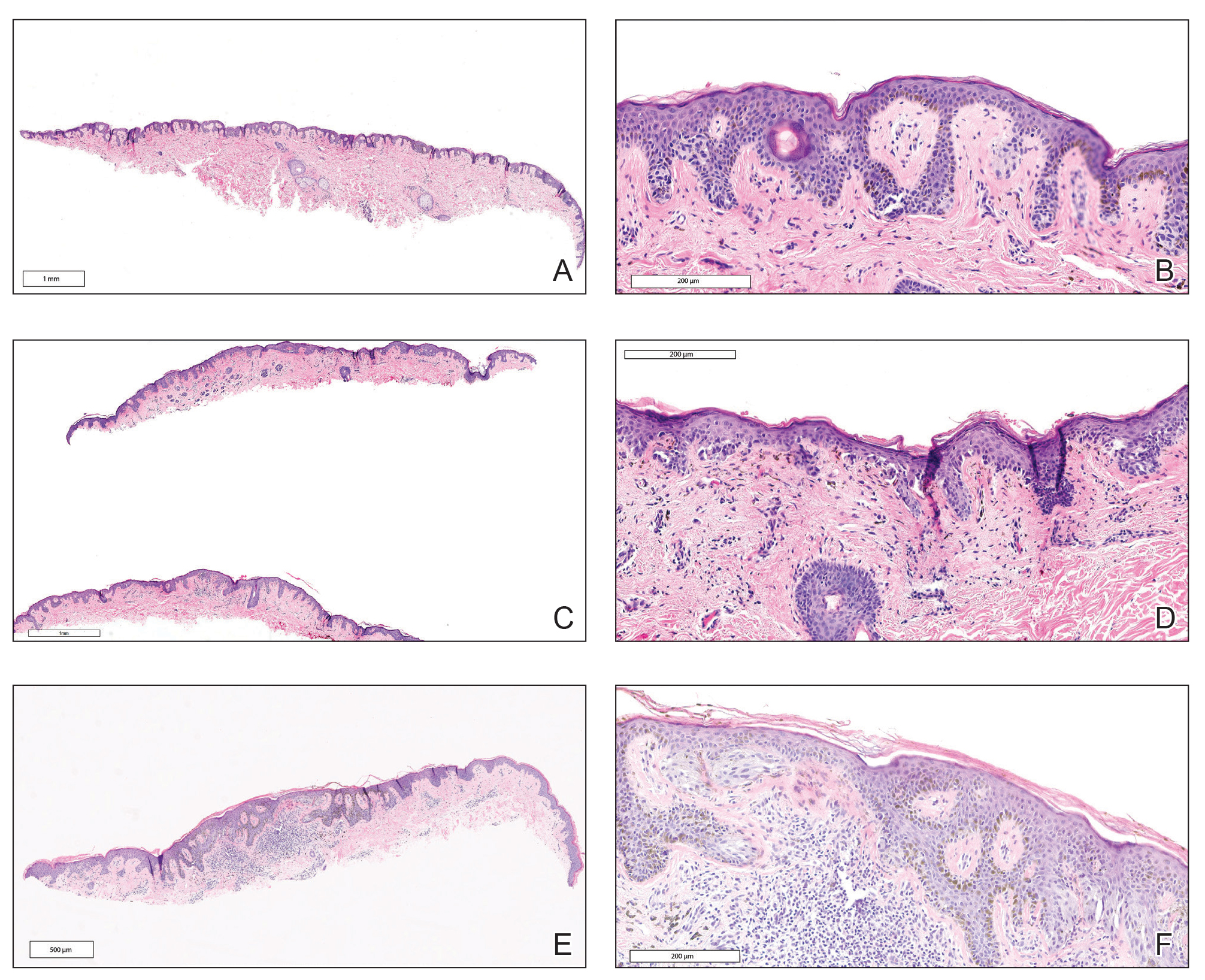

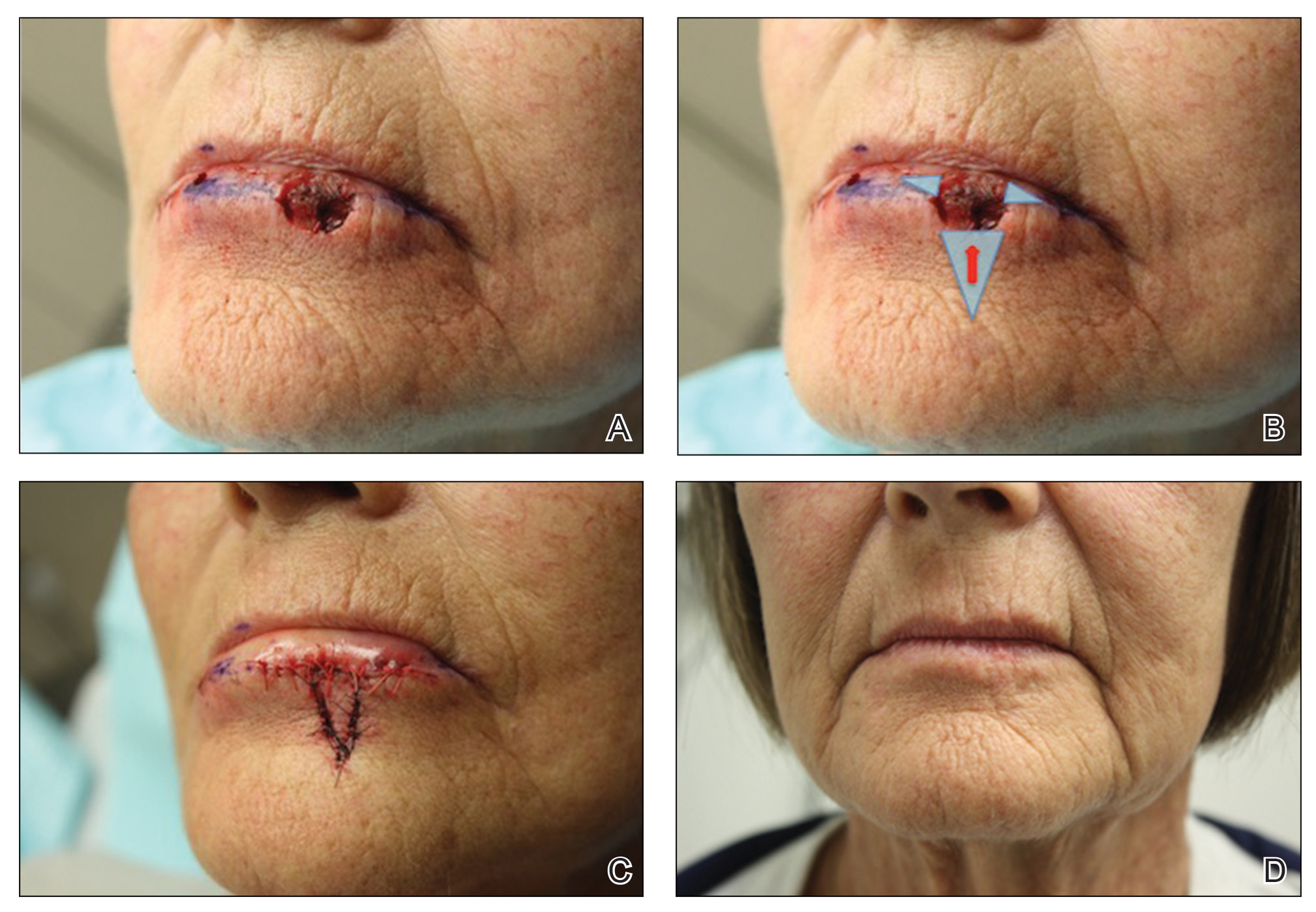

The first excision (case 1) involved a 67-year-old woman with a lesion on the mid pubic region described clinically as an atypical nevus that generated a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis including dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a nevus (Table 3; Figure, A and B). The gene expression test result was benign (score, −5.4), and the final pathology report diagnosis was nevus with junctional dysplasia, moderate. Surgical excision was performed at the patient’s first return visit, 505 days after initial diagnosis, with moderately dysplastic nevus as the recorded indication for removal. No repigmentation or other evidence of local recurrence or progression was detected, and the treating dermatologist indicated no suspicion that the original diagnosis of benign nevus was incorrect during the 23-month follow-up period.

The second excision (case 2) involved a 27-year-old woman with a pigmented neoplasm on the mid upper back (Figure, C and D) biopsied to rule out dysplastic nevus that resulted in a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus vs superficial spreading melanoma or melanoma arising within a nevus. The gene expression test result classified the lesion as benign (score, −2.9), and the final pathology diagnosis was nevus, compound, with moderate dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, residual neoplasm (or pigmentation) at the biopsy site prompted the patient to request excision at her first postbiopsy visit, 22 days after testing (Table 3). The CRF completed by the dermatologist reported no indication that the benign diagnosis was inaccurate, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

The third excision (case 3) involved a 32-year-old woman with a pigmented lesion on the abdomen (Table 3; Figure, E and F). The clinical description was irregular-appearing black papule, nevus with atypia, and the histopathologic differential diagnosis again included dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a preexisting nevus. The gene expression signature result was benign (score, −7.2), and the final diagnosis issued within the accompanying pathology report was nevus with moderate junctional dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, excision was performed 89 days after test result availability, with apparent residual pigmentation as the specified indication. As with the other 2 cases, the treating dermatologist confirmed that neither clinical features nor follow-up events suggested malignancy.

Comment

This study followed a cohort of 25 patients with histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms that were classified as benign by a diagnostic gene expression test with the intent of determining the outcomes of patients whose treatment aligned with their benign test result. All patients initially were managed according to their test result. During an average posttest clinical follow-up time of more than 3 years (38.5 months), the 25 biopsied lesions, most of which received a differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus, were regarded as benign nevi by their dermatologists, and the vast majority (88%) received no further surgical intervention. Three patients underwent subsequent excision of the biopsied lesion, with patient or physician preference as the indication in each instance. None of the 25 patients developed evidence of local recurrence, metastasis, or other findings that prompted doubt of the benign diagnosis. The absence of adverse events during clinical follow-up, particularly given that most lesions were not subjected to further intervention, supports use of the gene expression test as a safe and effective adjunct to the diagnosis and treatment of ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms by dermatologists and dermatopathologists.

Ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms evaluated without the aid of molecular adjuncts often result in equivocal or less-than-definitive diagnoses, and further surgical intervention is commonly undertaken to mitigate against the possibility of a missed melanoma.13 In this study, treatment that was aligned with the benign test result allowed most patients to avoid further surgical intervention, which suggests that adjunctive use of the gene signature can contribute to reductions in the physical and economic burdens imposed by unnecessary surgical interventions.15,16 Moreover, any means of increasing accurate and definitive diagnoses may produce an immediate impact on health outcomes by reducing the anxiety that uncertainty often provokes in patients and health care providers alike.

Study Limitations

This study must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Obtaining meaningful patient outcome data is a common challenge in health care research due to the requisite length of follow-up and sometimes the lack of definitive evidence of adverse events. This is particularly difficult for melanocytic neoplasms because of an apparent inclination for patients with benign diagnoses to abandon follow-up and an increasing tendency for even minimal diagnostic uncertainty to prompt complete excision. Additionally, the only definitive clinical outcome for melanocytic neoplasms is distant metastasis, which (fortunately for patients) is relatively rare. Not surprisingly, studies documenting clinical outcomes of patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms tested prospectively with diagnostic adjuncts are scarce, and this study’s sample size and clinical follow-up compare favorably with the few that exist.17,18 Although most melanomas declare themselves through recurrence or metastasis within several years of initial biopsy,1,19 some are clinically dormant for as long as 10 years after initial detection.20,21 This may be particularly true for the small or early-stage lesions that now comprise the majority of biopsied neoplasms, and such events would go undetected by this study and many others. It also must be recognized that uneventful follow-up, regardless of duration, cannot prove that a biopsied melanocytic neoplasm was benign. Although only 5 patients had a follow-up time of less than 2 years (the time frame in which most recurrence or metastasis will occur), it cannot be definitively proven that a minimum of 2 years recurrence- or metastasis-free survival indicates a benign lesion. Many early-stage malignant melanomas are eradicated by complete excision or even by the initial biopsy if margins are uninvolved.

Because these limitations are intrinsic to melanocytic neoplasms and current management strategies, they pertain to all investigations seeking insights into biological potential through clinical outcomes. Similarly, all current diagnostic tools and procedures have the potential for sampling error, including histopathology. The rarity of adverse outcomes (recurrence and metastasis) in patients with benign test results within this cohort indicates that false-negative results are uncommon, which is further evidenced by a similar rarity of adverse events in prior studies of the gene expression signature.8-10,22 A particular strength of this study is that most of the ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms followed did not undergo excision after the initial biopsy, an increasingly uncommon situation that may increase their likelihood to be informative.

It must be emphasized that the gene expression test, similar to other diagnostic adjuncts, is neither a replacement for histopathologic interpretation nor a substitute for judgment. As with all tests, it can produce false-positive and false-negative results. Therefore, it should always be interpreted within the constellation of the many other data points that must be considered when making a distinction between benign nevus and malignant melanoma, including but not limited to patient age, family and personal history of melanoma, anatomic location, clinical features, and histopathologic findings. As is the case for many diseases, careful consideration of all relevant input is necessary to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis that might occur should any single data point prove inaccurate, including the results of adjunctive molecular tests.

Conclusion

Ancillary methods are emerging as useful tools for the diagnostic evaluation of melanocytic neoplasms that cannot be assigned definitive diagnoses using traditional techniques alone. This study suggests that patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms may benefit from diagnoses and treatment decisions aligned with the results of a gene expression test, and that for those with a benign result, simple observation may be a safe alternative to surgical excision. This expands upon prior observations of the test’s influence on diagnoses and treatment decisions and supports its role as part of dermatopathologists’ and dermatologists’ decision-making process for histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic lesions.

- Noone AM, Howlander N, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015. National Cancer Institute website. Updated September 10, 2018. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/

- Shoo BA, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:751-756.

- Veenhuizen KC, De Wit PE, Mooi WJ, et al. Quality assessment by expert opinion in melanoma pathology: experience of the pathology panel of the Dutch Melanoma Working Party. J Pathol. 1997;182:266-272.

- Elmore JG, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, et al. Pathologists’ diagnosis of invasive melanoma and melanocytic proliferations: observer accuracy and reproducibility study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2813. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2813

- Glusac EJ. The melanoma ‘epidemic’, a dermatopathologist’s perspective. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:264-267.

- Welch HG, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Skin biopsy rates and incidence of melanoma: population based ecological study. BMJ. 2005;331:481.

- Swerlick RA, Chen S. The melanoma epidemic. Is increased surveillance the solution or the problem? Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:881-884.

- Ko JS, Matharoo-Ball B, Billings SD, et al. Diagnostic distinction of malignant melanoma and benign nevi by a gene expression signature and correlation to clinical outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1107-1113.

- Clarke LE, Flake DD 2nd, Busam K, et al. An independent validation of a gene expression signature to differentiate malignant melanoma from benign melanocytic nevi. Cancer. 2017;123:617-628.

- Clarke LE, Warf BM, Flake DD 2nd, et al. Clinical validation of a gene expression signature that differentiates benign nevi from malignant melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:244-252.

- Minca EC, Al-Rohil RN, Wang M, et al. Comparison between melanoma gene expression score and fluorescence in situ hybridization for the classification of melanocytic lesions. Mod Pathol. 2016;29:832-843.

- Cockerell CJ, Tschen J, Evans B, et al. The influence of a gene expression signature on the diagnosis and recommended treatment of melanocytic tumors by dermatopathologists. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4887. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004887

- Cockerell C, Tschen J, Billings SD, et al. The influence of a gene-expression signature on the treatment of diagnostically challenging melanocytic lesions. Per Med. 2017;14:123-130.

- Warf MB, Flake DD 2nd, Adams D, et al. Analytical validation of a melanoma diagnostic gene signature using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded melanocytic lesions. Biomark Med. 2015;9:407-416.

- Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, Tangka FK, et al. Melanoma treatment costs: a systematic review of the literature, 1990-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:537-545.

- Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the U.S., 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48:183-187.

- Egnatios GL, Ferringer TC. Clinical follow-up of atypical spitzoid tumors analyzed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:289-296.

- Fischer AS, High WA. The difficulty in interpreting gene expression profiling in BAP-negative melanocytic tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:659-666. doi:10.1111/cup.13277

- Vollmer RT. The dynamics of death in melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:1075-1082.

- Osella-Abate S, Ribero S, Sanlorenzo M, et al. Risk factors related to late metastases in 1,372 melanoma patients disease free more than 10 years. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:2453-2457.

- Faries MB, Steen S, Ye X, et al. Late recurrence in melanoma: clinical implications of lost dormancy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:27-34.

- Ko JS, Clarke LE, Minca EC, et al. Correlation of melanoma gene expression score with clinical outcomes on a series of melanocytic lesions. Hum Pathol. 2019;86:213-221.

According to National Institutes of Health estimates, more than 90,000 new cases of melanoma were diagnosed in 2018.1 Overall 5-year survival for patients with melanoma exceeds 90%, but individual survival estimates are highly dependent on stage at diagnosis, and survival decreases markedly with metastasis. Therefore, early and accurate diagnosis is critical.

Diagnosis of melanocytic neoplasms usually is performed by dermatopathologists through microscopic examination of stained tissue biopsy sections, a technically simple and effective method that enables a definitive diagnosis of benign nevus or malignant melanoma to be made in most cases. However, approximately 15% of all biopsied melanocytic lesions will exhibit some degree of histopathologic ambiguity,2-4 meaning that some of their microscopic features will be characteristic of a benign nevus while others will suggest the possibility of malignant melanoma. Diagnostic interpretations often vary in these cases, even among experts, and a definitive diagnosis of benign or malignant may be difficult to achieve by microscopy alone.2-4 Because of the marked reduction in survival once a melanoma has metastasized, these diagnostically ambiguous lesions often are treated as possible malignant melanomas with complete surgical excision (or re-excision). However, some experts suggest that many histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms are, in fact, benign,5 a notion supported by epidemiologic evidence.6,7 Therefore, excision of many ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms might be avoided if definitive diagnosis could be achieved.

A gene expression signature was developed and validated for use as an adjunct to traditional methods of differentiating malignant melanocytic neoplasms from their benign counterparts.8-11 This test quantifies the RNA transcripts produced by 14 genes known to be overexpressed in malignant melanomas by comparison to benign nevi. These values are then combined algorithmically with measurements of 9 reference genes to produce an objective numerical score that is classified as benign, malignant, or indeterminate. When used by board-certified dermatopathologists and dermatologists confronting ambiguous melanocytic lesions, the test produces substantial increases in definitive diagnoses and prompts changes in treatment recommendations.12,13 However, the long-term consequences of foregoing surgical excision of melanocytic neoplasms that are diagnostically ambiguous but classified as benign by this test have not yet been formally assessed. In the current study, prospectively tested patients whose ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms were classified as benign by the gene expression signature were followed for up to 4.5 years to evaluate the long-term safety of treatment decisions aligned with benign test results.

Methods

Study Population

As part of a prior study,12 US-based dermatopathologists submitted tissue sections from biopsied melanocytic neoplasms determined to be diagnostically ambiguous by histopathology for analysis with the gene expression signature (Myriad Genetics, Inc). Diagnostically ambiguous lesions were those lesions that were described as ambiguous, uncertain, equivocal, indeterminate, or other synonymous terms by the submitting dermatopathologist and therefore lacked a confident diagnosis of benign or malignant prior to testing. Patients initially were tested between May 2014 and August 2014, with samples submitted through a prospective clinical experience study designed to assess the impact of the test on diagnosis and treatment decisions. This study was performed under an institutional review board waiver of consent (Quorum #33403/1).

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the current study if their biopsy specimens (1) had an uncertain preliminary diagnosis according to the submitting dermatopathologist (pretest diagnosis of indeterminate); (2) received a negative (benign) score from the gene expression test; (3) were treated as benign by the dermatologist(s) involved in follow-up care; and (4) were submitted by a single site (St. Joseph Medical Center, Houston, Texas). Although a single dermatopathology site was used for this study, multiple dermatologists were involved in the final treatment of these patients. Patients with benign scores who received additional intervention were excluded, as they may have a lower rate of adverse events (ie, metastasis) than those who did not receive intervention and would therefore skew the analysis population. A total of 25 patients from the prior study met these inclusion criteria. The previously collected12 pretest and posttest de-identified data were compiled from the commercial laboratory databases, and the patients were followed from the time of testing via medical record review performed by the dermatology providers at participating sites. Clinical follow-up data were collected using study-specific case report forms (CRFs) that captured the following: (1) the dates and results of clinical follow-up visits; (2) the type(s) of treatment and interventions (if any) performed at those visits; (3) the specific indication for any intervention performed; (4) any evidence of persistent, locally recurrent, and/or distant melanocytic neoplasia (whether definitively attributable to the tested lesion or not); and (5) death from any cause. The CRF assigned interventions to 1 of 5 categories: excision, excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, referral to dermatologic or other surgeon, examination only (without surgical intervention), and other. Selection of other required a free-text description of the treatment and indications. Pertinent information not otherwise captured by the CRF also was recordable as free text.

Gene Expression Testing

Gene expression testing was carried out at the time of specimen submission in the prior study12 as described previously.14 Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, unstained tissue sections and/or tissue blocks were submitted for testing along with a single hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide used to identify and designate the representative portion(s) of the lesion to be tested. These areas were macrodissected from unstained tissue sections and pooled for RNA extraction. Expression of 14 biomarker genes and 9 reference genes was measured via

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and other baseline characteristics of the patient population were summarized. Follow-up time was calculated as the interval between the date a patient’s gene expression test result was first issued to the provider and the date of the patient’s last recorded visit during the study period. All patient dermatology office visits within the designated follow-up period were documented, with a nonstandard number of visits and follow-up time across all study patients. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc), R software version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and IBM SPSS Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25).

Results

Patient Sample

A total of 25 ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms from 25 patients met the study inclusion criteria of a benign gene expression result with subsequent treatment as a benign neoplasm during follow-up. The patient sample statistics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients were younger than 65 years, with an average age at the time of biopsy of 48.4 years. All 25 neoplasms produced negative (benign) gene expression signature scores, all were diagnosed as benign nevi posttest by the submitting dermatopathologist, and all patients were initially treated in accordance with the benign diagnosis by the dermatologist(s) involved in clinical follow-up care. Prior to testing with the gene expression signature, most of these histopathologically indeterminate lesions received differential diagnoses, the most common of which were dysplastic nevus (84%), melanoma arising from a nevus (72%), and superficial spreading melanoma (64%; eTable). After testing with the gene expression signature and receiving a benign score, most lesions received a single differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus (88%).

Follow-up and Survival

Clinical follow-up time ranged from 0.6 to 53.3 months, with a mean duration (SD) of 38.5 (16.6) months, and patients attended an average of 4 postbiopsy dermatology appointments (mean [SD], 4.6 [3.6]). According to the participating dermatology care providers, none of the 25 patients developed any indication during follow-up that the diagnosis of benign nevus was inaccurate. No patient had evidence of locally recurrent or metastatic melanoma, and none died during the study period.

Treatment/Interventions

The treatment recorded in the CRF was examination only for 21 of 25 patients, excision for 3, and other for 1 (Table 2). Because the explanation for the selection of other in this case described an excision performed at the same anatomic location as the biopsy, this treatment also was considered an excision for purposes of the study analyses. The 3 excisions all occurred at the first postbiopsy dermatology encounter. Across all follow-up visits, no additional surgical interventions occurred (Table 2).

The first excision (case 1) involved a 67-year-old woman with a lesion on the mid pubic region described clinically as an atypical nevus that generated a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis including dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a nevus (Table 3; Figure, A and B). The gene expression test result was benign (score, −5.4), and the final pathology report diagnosis was nevus with junctional dysplasia, moderate. Surgical excision was performed at the patient’s first return visit, 505 days after initial diagnosis, with moderately dysplastic nevus as the recorded indication for removal. No repigmentation or other evidence of local recurrence or progression was detected, and the treating dermatologist indicated no suspicion that the original diagnosis of benign nevus was incorrect during the 23-month follow-up period.

The second excision (case 2) involved a 27-year-old woman with a pigmented neoplasm on the mid upper back (Figure, C and D) biopsied to rule out dysplastic nevus that resulted in a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus vs superficial spreading melanoma or melanoma arising within a nevus. The gene expression test result classified the lesion as benign (score, −2.9), and the final pathology diagnosis was nevus, compound, with moderate dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, residual neoplasm (or pigmentation) at the biopsy site prompted the patient to request excision at her first postbiopsy visit, 22 days after testing (Table 3). The CRF completed by the dermatologist reported no indication that the benign diagnosis was inaccurate, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

The third excision (case 3) involved a 32-year-old woman with a pigmented lesion on the abdomen (Table 3; Figure, E and F). The clinical description was irregular-appearing black papule, nevus with atypia, and the histopathologic differential diagnosis again included dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a preexisting nevus. The gene expression signature result was benign (score, −7.2), and the final diagnosis issued within the accompanying pathology report was nevus with moderate junctional dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, excision was performed 89 days after test result availability, with apparent residual pigmentation as the specified indication. As with the other 2 cases, the treating dermatologist confirmed that neither clinical features nor follow-up events suggested malignancy.

Comment

This study followed a cohort of 25 patients with histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms that were classified as benign by a diagnostic gene expression test with the intent of determining the outcomes of patients whose treatment aligned with their benign test result. All patients initially were managed according to their test result. During an average posttest clinical follow-up time of more than 3 years (38.5 months), the 25 biopsied lesions, most of which received a differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus, were regarded as benign nevi by their dermatologists, and the vast majority (88%) received no further surgical intervention. Three patients underwent subsequent excision of the biopsied lesion, with patient or physician preference as the indication in each instance. None of the 25 patients developed evidence of local recurrence, metastasis, or other findings that prompted doubt of the benign diagnosis. The absence of adverse events during clinical follow-up, particularly given that most lesions were not subjected to further intervention, supports use of the gene expression test as a safe and effective adjunct to the diagnosis and treatment of ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms by dermatologists and dermatopathologists.

Ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms evaluated without the aid of molecular adjuncts often result in equivocal or less-than-definitive diagnoses, and further surgical intervention is commonly undertaken to mitigate against the possibility of a missed melanoma.13 In this study, treatment that was aligned with the benign test result allowed most patients to avoid further surgical intervention, which suggests that adjunctive use of the gene signature can contribute to reductions in the physical and economic burdens imposed by unnecessary surgical interventions.15,16 Moreover, any means of increasing accurate and definitive diagnoses may produce an immediate impact on health outcomes by reducing the anxiety that uncertainty often provokes in patients and health care providers alike.

Study Limitations

This study must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Obtaining meaningful patient outcome data is a common challenge in health care research due to the requisite length of follow-up and sometimes the lack of definitive evidence of adverse events. This is particularly difficult for melanocytic neoplasms because of an apparent inclination for patients with benign diagnoses to abandon follow-up and an increasing tendency for even minimal diagnostic uncertainty to prompt complete excision. Additionally, the only definitive clinical outcome for melanocytic neoplasms is distant metastasis, which (fortunately for patients) is relatively rare. Not surprisingly, studies documenting clinical outcomes of patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms tested prospectively with diagnostic adjuncts are scarce, and this study’s sample size and clinical follow-up compare favorably with the few that exist.17,18 Although most melanomas declare themselves through recurrence or metastasis within several years of initial biopsy,1,19 some are clinically dormant for as long as 10 years after initial detection.20,21 This may be particularly true for the small or early-stage lesions that now comprise the majority of biopsied neoplasms, and such events would go undetected by this study and many others. It also must be recognized that uneventful follow-up, regardless of duration, cannot prove that a biopsied melanocytic neoplasm was benign. Although only 5 patients had a follow-up time of less than 2 years (the time frame in which most recurrence or metastasis will occur), it cannot be definitively proven that a minimum of 2 years recurrence- or metastasis-free survival indicates a benign lesion. Many early-stage malignant melanomas are eradicated by complete excision or even by the initial biopsy if margins are uninvolved.

Because these limitations are intrinsic to melanocytic neoplasms and current management strategies, they pertain to all investigations seeking insights into biological potential through clinical outcomes. Similarly, all current diagnostic tools and procedures have the potential for sampling error, including histopathology. The rarity of adverse outcomes (recurrence and metastasis) in patients with benign test results within this cohort indicates that false-negative results are uncommon, which is further evidenced by a similar rarity of adverse events in prior studies of the gene expression signature.8-10,22 A particular strength of this study is that most of the ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms followed did not undergo excision after the initial biopsy, an increasingly uncommon situation that may increase their likelihood to be informative.

It must be emphasized that the gene expression test, similar to other diagnostic adjuncts, is neither a replacement for histopathologic interpretation nor a substitute for judgment. As with all tests, it can produce false-positive and false-negative results. Therefore, it should always be interpreted within the constellation of the many other data points that must be considered when making a distinction between benign nevus and malignant melanoma, including but not limited to patient age, family and personal history of melanoma, anatomic location, clinical features, and histopathologic findings. As is the case for many diseases, careful consideration of all relevant input is necessary to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis that might occur should any single data point prove inaccurate, including the results of adjunctive molecular tests.

Conclusion

Ancillary methods are emerging as useful tools for the diagnostic evaluation of melanocytic neoplasms that cannot be assigned definitive diagnoses using traditional techniques alone. This study suggests that patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms may benefit from diagnoses and treatment decisions aligned with the results of a gene expression test, and that for those with a benign result, simple observation may be a safe alternative to surgical excision. This expands upon prior observations of the test’s influence on diagnoses and treatment decisions and supports its role as part of dermatopathologists’ and dermatologists’ decision-making process for histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic lesions.

According to National Institutes of Health estimates, more than 90,000 new cases of melanoma were diagnosed in 2018.1 Overall 5-year survival for patients with melanoma exceeds 90%, but individual survival estimates are highly dependent on stage at diagnosis, and survival decreases markedly with metastasis. Therefore, early and accurate diagnosis is critical.

Diagnosis of melanocytic neoplasms usually is performed by dermatopathologists through microscopic examination of stained tissue biopsy sections, a technically simple and effective method that enables a definitive diagnosis of benign nevus or malignant melanoma to be made in most cases. However, approximately 15% of all biopsied melanocytic lesions will exhibit some degree of histopathologic ambiguity,2-4 meaning that some of their microscopic features will be characteristic of a benign nevus while others will suggest the possibility of malignant melanoma. Diagnostic interpretations often vary in these cases, even among experts, and a definitive diagnosis of benign or malignant may be difficult to achieve by microscopy alone.2-4 Because of the marked reduction in survival once a melanoma has metastasized, these diagnostically ambiguous lesions often are treated as possible malignant melanomas with complete surgical excision (or re-excision). However, some experts suggest that many histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms are, in fact, benign,5 a notion supported by epidemiologic evidence.6,7 Therefore, excision of many ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms might be avoided if definitive diagnosis could be achieved.

A gene expression signature was developed and validated for use as an adjunct to traditional methods of differentiating malignant melanocytic neoplasms from their benign counterparts.8-11 This test quantifies the RNA transcripts produced by 14 genes known to be overexpressed in malignant melanomas by comparison to benign nevi. These values are then combined algorithmically with measurements of 9 reference genes to produce an objective numerical score that is classified as benign, malignant, or indeterminate. When used by board-certified dermatopathologists and dermatologists confronting ambiguous melanocytic lesions, the test produces substantial increases in definitive diagnoses and prompts changes in treatment recommendations.12,13 However, the long-term consequences of foregoing surgical excision of melanocytic neoplasms that are diagnostically ambiguous but classified as benign by this test have not yet been formally assessed. In the current study, prospectively tested patients whose ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms were classified as benign by the gene expression signature were followed for up to 4.5 years to evaluate the long-term safety of treatment decisions aligned with benign test results.

Methods

Study Population

As part of a prior study,12 US-based dermatopathologists submitted tissue sections from biopsied melanocytic neoplasms determined to be diagnostically ambiguous by histopathology for analysis with the gene expression signature (Myriad Genetics, Inc). Diagnostically ambiguous lesions were those lesions that were described as ambiguous, uncertain, equivocal, indeterminate, or other synonymous terms by the submitting dermatopathologist and therefore lacked a confident diagnosis of benign or malignant prior to testing. Patients initially were tested between May 2014 and August 2014, with samples submitted through a prospective clinical experience study designed to assess the impact of the test on diagnosis and treatment decisions. This study was performed under an institutional review board waiver of consent (Quorum #33403/1).

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the current study if their biopsy specimens (1) had an uncertain preliminary diagnosis according to the submitting dermatopathologist (pretest diagnosis of indeterminate); (2) received a negative (benign) score from the gene expression test; (3) were treated as benign by the dermatologist(s) involved in follow-up care; and (4) were submitted by a single site (St. Joseph Medical Center, Houston, Texas). Although a single dermatopathology site was used for this study, multiple dermatologists were involved in the final treatment of these patients. Patients with benign scores who received additional intervention were excluded, as they may have a lower rate of adverse events (ie, metastasis) than those who did not receive intervention and would therefore skew the analysis population. A total of 25 patients from the prior study met these inclusion criteria. The previously collected12 pretest and posttest de-identified data were compiled from the commercial laboratory databases, and the patients were followed from the time of testing via medical record review performed by the dermatology providers at participating sites. Clinical follow-up data were collected using study-specific case report forms (CRFs) that captured the following: (1) the dates and results of clinical follow-up visits; (2) the type(s) of treatment and interventions (if any) performed at those visits; (3) the specific indication for any intervention performed; (4) any evidence of persistent, locally recurrent, and/or distant melanocytic neoplasia (whether definitively attributable to the tested lesion or not); and (5) death from any cause. The CRF assigned interventions to 1 of 5 categories: excision, excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy, referral to dermatologic or other surgeon, examination only (without surgical intervention), and other. Selection of other required a free-text description of the treatment and indications. Pertinent information not otherwise captured by the CRF also was recordable as free text.

Gene Expression Testing

Gene expression testing was carried out at the time of specimen submission in the prior study12 as described previously.14 Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, unstained tissue sections and/or tissue blocks were submitted for testing along with a single hematoxylin and eosin–stained slide used to identify and designate the representative portion(s) of the lesion to be tested. These areas were macrodissected from unstained tissue sections and pooled for RNA extraction. Expression of 14 biomarker genes and 9 reference genes was measured via

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and other baseline characteristics of the patient population were summarized. Follow-up time was calculated as the interval between the date a patient’s gene expression test result was first issued to the provider and the date of the patient’s last recorded visit during the study period. All patient dermatology office visits within the designated follow-up period were documented, with a nonstandard number of visits and follow-up time across all study patients. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc), R software version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), and IBM SPSS Statistics software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25).

Results

Patient Sample

A total of 25 ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms from 25 patients met the study inclusion criteria of a benign gene expression result with subsequent treatment as a benign neoplasm during follow-up. The patient sample statistics are summarized in Table 1. Most patients were younger than 65 years, with an average age at the time of biopsy of 48.4 years. All 25 neoplasms produced negative (benign) gene expression signature scores, all were diagnosed as benign nevi posttest by the submitting dermatopathologist, and all patients were initially treated in accordance with the benign diagnosis by the dermatologist(s) involved in clinical follow-up care. Prior to testing with the gene expression signature, most of these histopathologically indeterminate lesions received differential diagnoses, the most common of which were dysplastic nevus (84%), melanoma arising from a nevus (72%), and superficial spreading melanoma (64%; eTable). After testing with the gene expression signature and receiving a benign score, most lesions received a single differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus (88%).

Follow-up and Survival

Clinical follow-up time ranged from 0.6 to 53.3 months, with a mean duration (SD) of 38.5 (16.6) months, and patients attended an average of 4 postbiopsy dermatology appointments (mean [SD], 4.6 [3.6]). According to the participating dermatology care providers, none of the 25 patients developed any indication during follow-up that the diagnosis of benign nevus was inaccurate. No patient had evidence of locally recurrent or metastatic melanoma, and none died during the study period.

Treatment/Interventions

The treatment recorded in the CRF was examination only for 21 of 25 patients, excision for 3, and other for 1 (Table 2). Because the explanation for the selection of other in this case described an excision performed at the same anatomic location as the biopsy, this treatment also was considered an excision for purposes of the study analyses. The 3 excisions all occurred at the first postbiopsy dermatology encounter. Across all follow-up visits, no additional surgical interventions occurred (Table 2).

The first excision (case 1) involved a 67-year-old woman with a lesion on the mid pubic region described clinically as an atypical nevus that generated a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis including dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a nevus (Table 3; Figure, A and B). The gene expression test result was benign (score, −5.4), and the final pathology report diagnosis was nevus with junctional dysplasia, moderate. Surgical excision was performed at the patient’s first return visit, 505 days after initial diagnosis, with moderately dysplastic nevus as the recorded indication for removal. No repigmentation or other evidence of local recurrence or progression was detected, and the treating dermatologist indicated no suspicion that the original diagnosis of benign nevus was incorrect during the 23-month follow-up period.

The second excision (case 2) involved a 27-year-old woman with a pigmented neoplasm on the mid upper back (Figure, C and D) biopsied to rule out dysplastic nevus that resulted in a pretest histopathologic differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus vs superficial spreading melanoma or melanoma arising within a nevus. The gene expression test result classified the lesion as benign (score, −2.9), and the final pathology diagnosis was nevus, compound, with moderate dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, residual neoplasm (or pigmentation) at the biopsy site prompted the patient to request excision at her first postbiopsy visit, 22 days after testing (Table 3). The CRF completed by the dermatologist reported no indication that the benign diagnosis was inaccurate, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

The third excision (case 3) involved a 32-year-old woman with a pigmented lesion on the abdomen (Table 3; Figure, E and F). The clinical description was irregular-appearing black papule, nevus with atypia, and the histopathologic differential diagnosis again included dysplastic nevus, superficial spreading melanoma, and melanoma arising within a preexisting nevus. The gene expression signature result was benign (score, −7.2), and the final diagnosis issued within the accompanying pathology report was nevus with moderate junctional dysplasia. Despite the benign diagnosis, excision was performed 89 days after test result availability, with apparent residual pigmentation as the specified indication. As with the other 2 cases, the treating dermatologist confirmed that neither clinical features nor follow-up events suggested malignancy.

Comment

This study followed a cohort of 25 patients with histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms that were classified as benign by a diagnostic gene expression test with the intent of determining the outcomes of patients whose treatment aligned with their benign test result. All patients initially were managed according to their test result. During an average posttest clinical follow-up time of more than 3 years (38.5 months), the 25 biopsied lesions, most of which received a differential diagnosis of dysplastic nevus, were regarded as benign nevi by their dermatologists, and the vast majority (88%) received no further surgical intervention. Three patients underwent subsequent excision of the biopsied lesion, with patient or physician preference as the indication in each instance. None of the 25 patients developed evidence of local recurrence, metastasis, or other findings that prompted doubt of the benign diagnosis. The absence of adverse events during clinical follow-up, particularly given that most lesions were not subjected to further intervention, supports use of the gene expression test as a safe and effective adjunct to the diagnosis and treatment of ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms by dermatologists and dermatopathologists.

Ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms evaluated without the aid of molecular adjuncts often result in equivocal or less-than-definitive diagnoses, and further surgical intervention is commonly undertaken to mitigate against the possibility of a missed melanoma.13 In this study, treatment that was aligned with the benign test result allowed most patients to avoid further surgical intervention, which suggests that adjunctive use of the gene signature can contribute to reductions in the physical and economic burdens imposed by unnecessary surgical interventions.15,16 Moreover, any means of increasing accurate and definitive diagnoses may produce an immediate impact on health outcomes by reducing the anxiety that uncertainty often provokes in patients and health care providers alike.

Study Limitations

This study must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. Obtaining meaningful patient outcome data is a common challenge in health care research due to the requisite length of follow-up and sometimes the lack of definitive evidence of adverse events. This is particularly difficult for melanocytic neoplasms because of an apparent inclination for patients with benign diagnoses to abandon follow-up and an increasing tendency for even minimal diagnostic uncertainty to prompt complete excision. Additionally, the only definitive clinical outcome for melanocytic neoplasms is distant metastasis, which (fortunately for patients) is relatively rare. Not surprisingly, studies documenting clinical outcomes of patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms tested prospectively with diagnostic adjuncts are scarce, and this study’s sample size and clinical follow-up compare favorably with the few that exist.17,18 Although most melanomas declare themselves through recurrence or metastasis within several years of initial biopsy,1,19 some are clinically dormant for as long as 10 years after initial detection.20,21 This may be particularly true for the small or early-stage lesions that now comprise the majority of biopsied neoplasms, and such events would go undetected by this study and many others. It also must be recognized that uneventful follow-up, regardless of duration, cannot prove that a biopsied melanocytic neoplasm was benign. Although only 5 patients had a follow-up time of less than 2 years (the time frame in which most recurrence or metastasis will occur), it cannot be definitively proven that a minimum of 2 years recurrence- or metastasis-free survival indicates a benign lesion. Many early-stage malignant melanomas are eradicated by complete excision or even by the initial biopsy if margins are uninvolved.

Because these limitations are intrinsic to melanocytic neoplasms and current management strategies, they pertain to all investigations seeking insights into biological potential through clinical outcomes. Similarly, all current diagnostic tools and procedures have the potential for sampling error, including histopathology. The rarity of adverse outcomes (recurrence and metastasis) in patients with benign test results within this cohort indicates that false-negative results are uncommon, which is further evidenced by a similar rarity of adverse events in prior studies of the gene expression signature.8-10,22 A particular strength of this study is that most of the ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms followed did not undergo excision after the initial biopsy, an increasingly uncommon situation that may increase their likelihood to be informative.

It must be emphasized that the gene expression test, similar to other diagnostic adjuncts, is neither a replacement for histopathologic interpretation nor a substitute for judgment. As with all tests, it can produce false-positive and false-negative results. Therefore, it should always be interpreted within the constellation of the many other data points that must be considered when making a distinction between benign nevus and malignant melanoma, including but not limited to patient age, family and personal history of melanoma, anatomic location, clinical features, and histopathologic findings. As is the case for many diseases, careful consideration of all relevant input is necessary to minimize the risk of misdiagnosis that might occur should any single data point prove inaccurate, including the results of adjunctive molecular tests.

Conclusion

Ancillary methods are emerging as useful tools for the diagnostic evaluation of melanocytic neoplasms that cannot be assigned definitive diagnoses using traditional techniques alone. This study suggests that patients with ambiguous melanocytic neoplasms may benefit from diagnoses and treatment decisions aligned with the results of a gene expression test, and that for those with a benign result, simple observation may be a safe alternative to surgical excision. This expands upon prior observations of the test’s influence on diagnoses and treatment decisions and supports its role as part of dermatopathologists’ and dermatologists’ decision-making process for histopathologically ambiguous melanocytic lesions.

- Noone AM, Howlander N, Krapcho M, et al, eds. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015. National Cancer Institute website. Updated September 10, 2018. Accessed April 21, 2021. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2015/

- Shoo BA, Sagebiel RW, Kashani-Sabet M. Discordance in the histopathologic diagnosis of melanoma at a melanoma referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:751-756.

- Veenhuizen KC, De Wit PE, Mooi WJ, et al. Quality assessment by expert opinion in melanoma pathology: experience of the pathology panel of the Dutch Melanoma Working Party. J Pathol. 1997;182:266-272.

- Elmore JG, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, et al. Pathologists’ diagnosis of invasive melanoma and melanocytic proliferations: observer accuracy and reproducibility study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2813. doi:10.1136/bmj.j2813