User login

Nodule on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

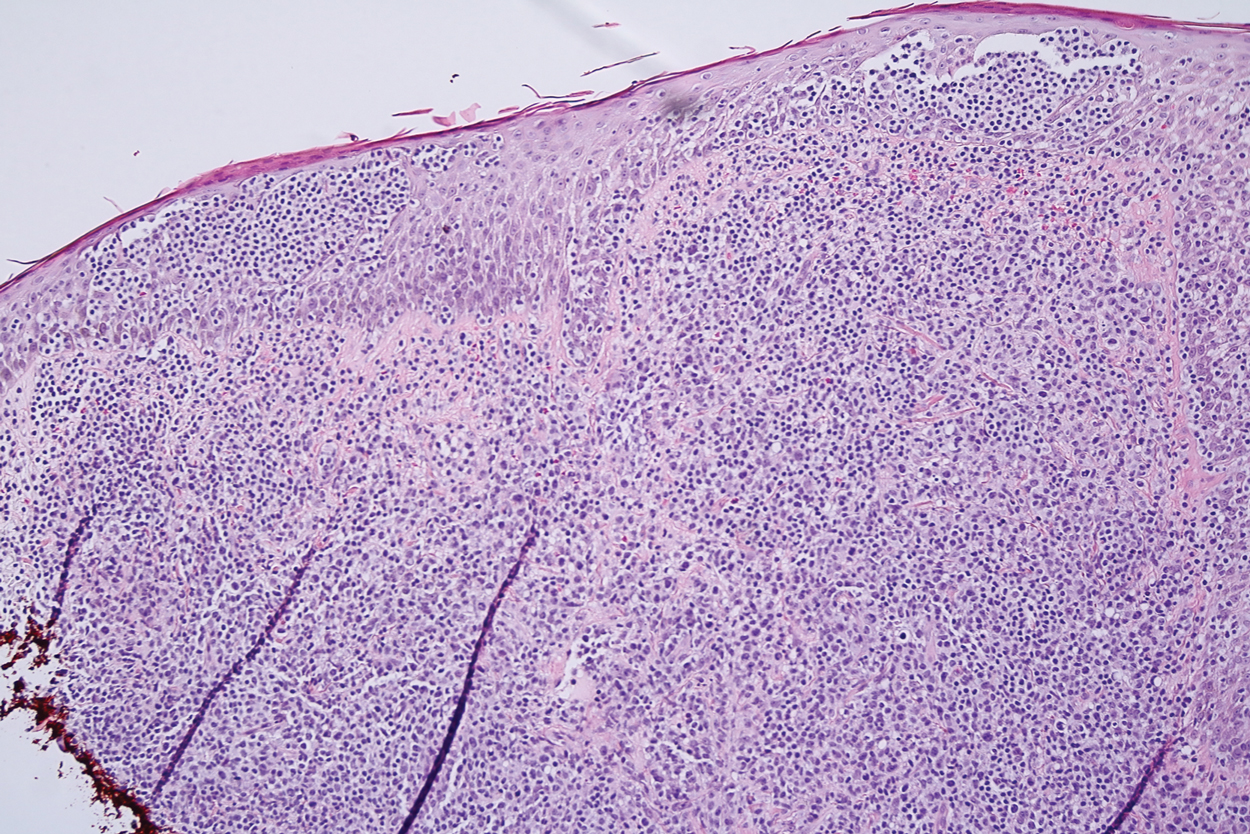

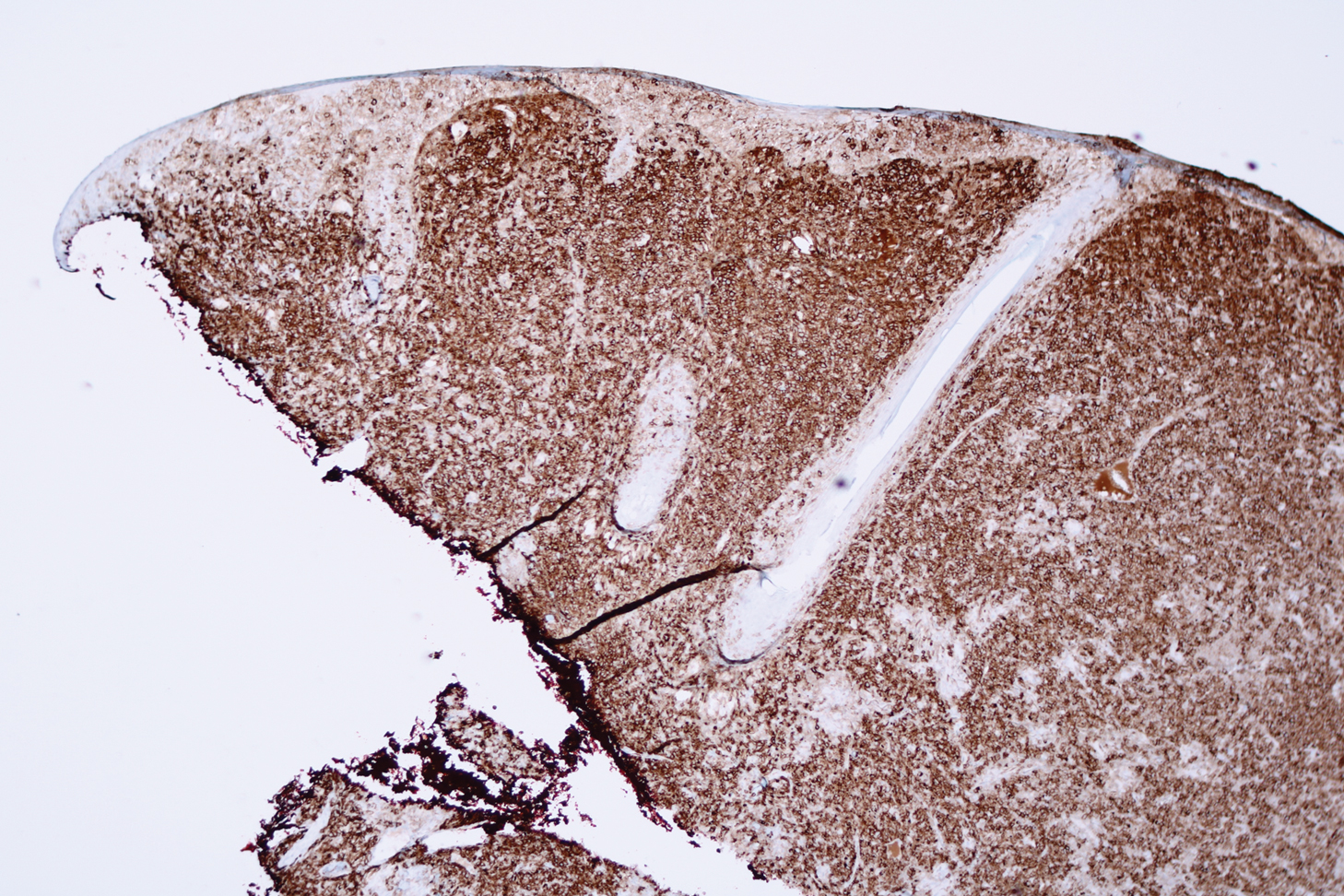

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Brown RA, Fernandez-Pol S, Kim J. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:570-577.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-17.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2015:475-489.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Microscopic analysis showed a dense proliferation of mononuclear cells filling and expanding the dermis with focal epidermotropism (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated strong and diffuse staining for CD3, CD4, and CD30 (Figure 2) and lack of staining for anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Workup to exclude systemic disease was initiated and included unremarkable computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis along with no abnormal cells on bone marrow biopsy. Complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and lactate dehydrogenase were within reference range. Given the lack of evidence for systemic involvement, a diagnosis of primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma (PC-ALCL) was made. The treatment plan for our patient with a solitary lesion was localized radiation therapy.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders encompass a spectrum of conditions, with premalignant lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP) at one extreme and the malignant PC-ALCL on the other.1 The diagnosis of PC-ALCL is made by clinicopathologic correlation, and lesions typically present abruptly as solitary or grouped nodules with a tendency to ulcerate over time. Spontaneous regression has been reported, but relapse in the skin is frequent.2

A representative, typically excisional, biopsy should be performed if the clinician suspects PC-ALCL. Histologic criteria include a dense dermal infiltrate of large pleomorphic cells and the expression of CD30 in at least 75% of tumor cells.3 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma typically lacks the ALK gene translocation with the nucleophosmin gene, NPM, that is common in systemic disease; however, a small subset of PC-ALCL may be ALK positive and indicate a higher chance of transformation into systemic disease.2

The extent of the lymphoma should be staged to exclude the possibility of systemic disease. This assessment includes a complete physical examination; laboratory investigation, including complete blood cell count with differential and blood chemistries; and radiography. A positron emission tomography-CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, or a whole-body integrated positron emission tomography-CT are sufficient for the radiographic examination.3

The initial choice of treatment for solitary or localized PC-ALCL is localized radiation therapy or low-dose methotrexate. Targeted therapy such as brentuximab has been shown to be effective for those with multifocal systemic involvement or refractory disease.2 Cure rates from radiation therapy alone approach 95%.3 It is important to highlight radiation therapy as the initial management plan to increase awareness and to avoid inappropriate treatment of PC-ALCL with traditional chemotherapy.

Large lesions of LyP may appear similar to PC-ALCL on histopathology, making the two entities difficult to distinguish. However, in contrast to PC-ALCL, LyP classically has a different clinical course characterized by waxing and waning crops of lesions that typically are smaller (<1 cm) than those of PC-ALCL.2 Large cell transformation of mycosis fungoides is another entity to consider, but these patients usually have a known history of mycosis fungoides.4

Keratoacanthomas, considered to be a variant of a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, present as rapidly enlarging crateriform nodules with a keratotic core. They usually are found on the head and neck or sun-exposed areas of the extremities and may regress spontaneously.5 Histology will show atypical, highly differentiated squamous epithelia. Merkel cell carcinoma also has a predilection for the head and neck in older patients and may present as a rapidly growing nodule. However, histology will show an aggressive tumor with small round blue cells, and immunohistochemistry will show the characteristic paranuclear dot staining for CK20 along with staining for various neuroendocrine markers. Similarly, atypical fibroxanthoma is a low-grade sarcoma that also presents on the head and neck of elderly sun-damaged patients.5 Histology will show dermal proliferation of spindle cells that often extend up against the epidermis along with pleomorphism and atypical mitoses. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor that can present on the head and neck in sun-damaged patients. Nodular basal cell carcinomas can enlarge and ulcerate, but growth is seen over years rather than weeks.5 Histology characteristically will show tumor islands composed of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and clefting between the tumor islands and the stroma.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Brown RA, Fernandez-Pol S, Kim J. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:570-577.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-17.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2015:475-489.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127:2375-2390.

- Brown RA, Fernandez-Pol S, Kim J. Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:570-577.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al. EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118:4024-4035.

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part II. prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:223.e1-17.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Saunders Elsevier; 2015:475-489.

An 80-year-old man presented to our clinic with a large lesion on the right upper neck of approximately 4 weeks’ duration. He reported that it was rapidly increasing in size and had bled on several occasions. No treatments were attempted prior to the initial visit. He denied any constitutional symptoms. The patient had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers but no other chronic medical problems. Physical examination revealed a large, 35×40-mm, erythematous nodule with central ulceration and overlying hyperkeratosis on the right upper neck. No palpable cervical, supraclavicular, or axillary lymphadenopathy was observed. An excisional biopsy of the lesion was obtained.

A tumultuous and unforgettable year

SHM president bids farewell

As my SHM presidency wraps up, it is a good time to reflect on the past year in hospital medicine. Dominated by COVID-19 preparedness, mitigation, and (now) recovery efforts, the impacts of COVID-19 throughout the medical industry have been profound. For hospital medicine, although we have endured work and home stress unlike anything in recent memory, fortunately a few notably good changes have come about as a result of COVID-19.

Hospitalists have proven that we are extremely capable of adapting to rapidly changing evidence-based practice. The old adage of evidence taking 7 years to become mainstream clinical practice certainly has not been the paradigm during COVID-19. In many cases, clinical care pathways were changing by the week, or even by the day. Usage of SHM’s website, HMX, and educational platforms rose exponentially to keep pace with the changing landscape. Information exchange between and among hospital medicine groups was efficient and effective. This is exactly how it should be, with SHM serving as the catalyst for such information exchange.

Hospitalists were able to shift to telehealth care as the need arose. The use of telehealth is now becoming a core competency for hospitalists around the country, and we are leading the way for other specialists in adoption. COVID-19 enabled not only rapid transformation, but also better payer coverage for the use of all types of telehealth services. SHM will remain a source of training and education in telehealth best practices going forward.

Related, hospitalists also found their programs were being asked to become purveyors for remote monitoring and hospital-at-home programs. Because CMS has allowed some reimbursement for these programs, at least during the public health emergency, hospital medicine programs can more feasibly pursue building and sustaining such programs, and SHM can serve as the hub for best practice exchanges in the field.

The pandemic also created a sizable shift in the mindset of the need and enthusiasm for mainstream maintenance of certification. Although there were already questions about the value of high-stakes exams before the pandemic, both within and outside the medical industry, the pandemic created an immediate need to shift away from such exams. Now, the entire pipeline is questioning the value of these high-stakes exams, such as SATs and ACTs for college admissions, Step 1 exams for medical students, and certification exams for physicians. The pandemic has made us question these milestone exams with more scrutiny and has created a sense of urgency for a change to more adult-learner–focused alternatives. SHM will continue to be at the centerpiece of the discussion, as well as the leader in cultivating educational venues for continuous learning.

So where do we go from here?

I am confident that SHM will continue to pay deep attention to the activities that bring value to hospitalists and support changing practice patterns such as telehealth and hospital-at-home work. Not only will SHM serve as a center for best practices and a conduit for networking and information sharing at the national level – there will be significantly more focus on the support and growth of local chapters. SHM realizes that local chapters are a vital source of networking, education, and pipeline development and will continue to increase the resources to make the chapter programs dynamic and inviting for everyone interested in hospital medicine.

While this presidency year was far different than expected, I have continuously been amazed and delighted with the resiliency and endurance of our hospitalists around the country. We stood out at the front lines of the pandemic, with a mission toward service and a relentless commitment to our patients. Although we still have a long way to go before the pandemic is behind us, I firmly believe we are emerging from the haze stronger and more agile than ever. Thank you for allowing me to serve this incredible organization during such a tumultuous and unforgettable year.

Yours in service.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing president of SHM.

SHM president bids farewell

SHM president bids farewell

As my SHM presidency wraps up, it is a good time to reflect on the past year in hospital medicine. Dominated by COVID-19 preparedness, mitigation, and (now) recovery efforts, the impacts of COVID-19 throughout the medical industry have been profound. For hospital medicine, although we have endured work and home stress unlike anything in recent memory, fortunately a few notably good changes have come about as a result of COVID-19.

Hospitalists have proven that we are extremely capable of adapting to rapidly changing evidence-based practice. The old adage of evidence taking 7 years to become mainstream clinical practice certainly has not been the paradigm during COVID-19. In many cases, clinical care pathways were changing by the week, or even by the day. Usage of SHM’s website, HMX, and educational platforms rose exponentially to keep pace with the changing landscape. Information exchange between and among hospital medicine groups was efficient and effective. This is exactly how it should be, with SHM serving as the catalyst for such information exchange.

Hospitalists were able to shift to telehealth care as the need arose. The use of telehealth is now becoming a core competency for hospitalists around the country, and we are leading the way for other specialists in adoption. COVID-19 enabled not only rapid transformation, but also better payer coverage for the use of all types of telehealth services. SHM will remain a source of training and education in telehealth best practices going forward.

Related, hospitalists also found their programs were being asked to become purveyors for remote monitoring and hospital-at-home programs. Because CMS has allowed some reimbursement for these programs, at least during the public health emergency, hospital medicine programs can more feasibly pursue building and sustaining such programs, and SHM can serve as the hub for best practice exchanges in the field.

The pandemic also created a sizable shift in the mindset of the need and enthusiasm for mainstream maintenance of certification. Although there were already questions about the value of high-stakes exams before the pandemic, both within and outside the medical industry, the pandemic created an immediate need to shift away from such exams. Now, the entire pipeline is questioning the value of these high-stakes exams, such as SATs and ACTs for college admissions, Step 1 exams for medical students, and certification exams for physicians. The pandemic has made us question these milestone exams with more scrutiny and has created a sense of urgency for a change to more adult-learner–focused alternatives. SHM will continue to be at the centerpiece of the discussion, as well as the leader in cultivating educational venues for continuous learning.

So where do we go from here?

I am confident that SHM will continue to pay deep attention to the activities that bring value to hospitalists and support changing practice patterns such as telehealth and hospital-at-home work. Not only will SHM serve as a center for best practices and a conduit for networking and information sharing at the national level – there will be significantly more focus on the support and growth of local chapters. SHM realizes that local chapters are a vital source of networking, education, and pipeline development and will continue to increase the resources to make the chapter programs dynamic and inviting for everyone interested in hospital medicine.

While this presidency year was far different than expected, I have continuously been amazed and delighted with the resiliency and endurance of our hospitalists around the country. We stood out at the front lines of the pandemic, with a mission toward service and a relentless commitment to our patients. Although we still have a long way to go before the pandemic is behind us, I firmly believe we are emerging from the haze stronger and more agile than ever. Thank you for allowing me to serve this incredible organization during such a tumultuous and unforgettable year.

Yours in service.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing president of SHM.

As my SHM presidency wraps up, it is a good time to reflect on the past year in hospital medicine. Dominated by COVID-19 preparedness, mitigation, and (now) recovery efforts, the impacts of COVID-19 throughout the medical industry have been profound. For hospital medicine, although we have endured work and home stress unlike anything in recent memory, fortunately a few notably good changes have come about as a result of COVID-19.

Hospitalists have proven that we are extremely capable of adapting to rapidly changing evidence-based practice. The old adage of evidence taking 7 years to become mainstream clinical practice certainly has not been the paradigm during COVID-19. In many cases, clinical care pathways were changing by the week, or even by the day. Usage of SHM’s website, HMX, and educational platforms rose exponentially to keep pace with the changing landscape. Information exchange between and among hospital medicine groups was efficient and effective. This is exactly how it should be, with SHM serving as the catalyst for such information exchange.

Hospitalists were able to shift to telehealth care as the need arose. The use of telehealth is now becoming a core competency for hospitalists around the country, and we are leading the way for other specialists in adoption. COVID-19 enabled not only rapid transformation, but also better payer coverage for the use of all types of telehealth services. SHM will remain a source of training and education in telehealth best practices going forward.

Related, hospitalists also found their programs were being asked to become purveyors for remote monitoring and hospital-at-home programs. Because CMS has allowed some reimbursement for these programs, at least during the public health emergency, hospital medicine programs can more feasibly pursue building and sustaining such programs, and SHM can serve as the hub for best practice exchanges in the field.

The pandemic also created a sizable shift in the mindset of the need and enthusiasm for mainstream maintenance of certification. Although there were already questions about the value of high-stakes exams before the pandemic, both within and outside the medical industry, the pandemic created an immediate need to shift away from such exams. Now, the entire pipeline is questioning the value of these high-stakes exams, such as SATs and ACTs for college admissions, Step 1 exams for medical students, and certification exams for physicians. The pandemic has made us question these milestone exams with more scrutiny and has created a sense of urgency for a change to more adult-learner–focused alternatives. SHM will continue to be at the centerpiece of the discussion, as well as the leader in cultivating educational venues for continuous learning.

So where do we go from here?

I am confident that SHM will continue to pay deep attention to the activities that bring value to hospitalists and support changing practice patterns such as telehealth and hospital-at-home work. Not only will SHM serve as a center for best practices and a conduit for networking and information sharing at the national level – there will be significantly more focus on the support and growth of local chapters. SHM realizes that local chapters are a vital source of networking, education, and pipeline development and will continue to increase the resources to make the chapter programs dynamic and inviting for everyone interested in hospital medicine.

While this presidency year was far different than expected, I have continuously been amazed and delighted with the resiliency and endurance of our hospitalists around the country. We stood out at the front lines of the pandemic, with a mission toward service and a relentless commitment to our patients. Although we still have a long way to go before the pandemic is behind us, I firmly believe we are emerging from the haze stronger and more agile than ever. Thank you for allowing me to serve this incredible organization during such a tumultuous and unforgettable year.

Yours in service.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer, MUSC Health System, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is the outgoing president of SHM.

A ‘mess’ of a diagnosis: Is it type 2 MI or a nonischemic imposter?

Survival gains in the management of acute myocardial infarction in recent decades don’t apply to one increasingly common category of MI.

Type 2 MI, triggered by a surge in myocardial oxygen demand or a drop in its supply, is on the rise and might be more prognostically serious than the “classic” atherothrombotic type 1 form, for which there have been such impressive strides in therapy.

Strategies for assessing and treating type 2 MI and another condition it can resemble clinically – nonischemic myocardial injury – have been less rigorously explored and are far less settled.

That could be partly because recent iterations of the consensus-based universal definition of MI define type 1 MI primarily by the atherothrombotic process, whereas “demand” type 2 MI is characterized as secondary to other disorders. The list of potential primary conditions, cardiac and noncardiac, is long.

As a result, patients with type 1 MI are clinically well defined, but those with type 2 MI have so far defied efforts to be clinically characterized in a consistent way. However, recent efforts might change that, given growing appreciation that all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality outcomes are actually worse for patients with type 2 MI.

“That’s because we have lots of treatments for type 1 MI. Type 2 and myocardial injury? We don’t know how to treat them,” David E. Newby, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, said in an interview.

Dr. Newby pointed to a widely cited 2018 publication, of which he is a coauthor, documenting 5-year outcomes of 2,122 patients with type 1 MI, type 2 MI, or nonischemic myocardial injury per the newly minted fourth universal definition.

Risk-factor profiles for patients with the latter two conditions contrasted with those of patients with type 1 MI, he observed. They were “a lot older,” were less likely to be smokers, had more hypertension and previous stroke, and a less prominent CV family history.

“So they’re a different beast,” Dr. Newby said. And their prognosis tended to be worse: all-cause mortality was about 62% for patients with type 2 MI and 72% with nonischemic myocardial injury, but only 37% for patients with type 1 MI. The difference between the two types of infarction was driven by an excess of noncardiovascular death after type 2 MI.

Mortality in patients with type 2 MI is “quite high, but it may well be a marker of the fact that you’ve got other serious diseases on board that are associated with poorer outcome,” he said.

Risk varies

The degree of risk in type 2 MI seems to vary with the underlying condition, a recent cohort study suggests. In about 3,800 patients with cardiac troponin (cTn) elevations qualifying as MI – a younger group; most were in their 30s and 40s – mortality at 10 years was 12% for those with type 1 MI, but 34% for those with type 2 MI and 46% for the remainder with nonischemic myocardial injury.

Underlying precipitating conditions varied widely among the patients with type 2 MI or nonischemic myocardial injury, and there was broad variation in mortality by etiology among those with type 2 MI. Sepsis and anemia entailed some of the highest risk, and hypertension and arrhythmias some of the lowest.

A prospective, community-based study of 5,460 patients with type 1 MI or type 2 MI reached a similar conclusion, but with a twist. Five-year all-cause mortality contrasted significantly between types of MI at 31% and 52%, respectively, but CV mortality rates were similar in this study.

Mortality in type 2 MI again varied by the precipitating etiology, suggesting that patients can be risk stratified according to pathophysiological mechanism behind their demand infarction, the authors concluded, “underscoring that type 2 MI is not a single entity, rather a group of phenotypic clusters.”

The usually high comorbidity burden and CV risk in patients with type 2 MI, one of those authors said in an interview, suggest there are “opportunities to see whether we can reduce that risk.”

Formal recommendations consistently say that, in patients with type 2 MI, “your first and foremost target should be to treat the underlying trigger and cause,” said Yader Sandoval, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. That means such opportunities for further CV risk reduction tend to be “underappreciated.”

“In principle, treating the inciting cause of type 2 MI or the injury is important,” said James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, in an interview, “but I feel quite strongly that there must be more that we can do for these folks.”

Dr. Januzzi is senior author on a recent analysis based on more than 200,000 admissions across the United States that saw a 43% lower risk for in-hospital death and 54% lower risk for 30-day MI readmission for patients with type 2 MI than those with type 1, adjusted for risk factors and comorbidities.

But, “it is important to emphasize that type 2 MI patients had a substantial risk for adverse outcome, nonetheless, and lack a clear management approach,” Dr. Januzzi and colleagues stated in their publication, as reported by this news organization.

“Due to the high rates of long-term cardiovascular events experienced by the frequently encountered type 2 MI patients,” they wrote, “identifying evidence-based therapies represents a major unmet need.”

That such patients tend to be sick with multiple comorbidities and have not yet been clinically well characterized, Dr. Januzzi said, “has stymied our ability to develop a treatment strategy.”

Role of the universal definitions

That challenge might in some ways be complicated by the universal definition, especially version 4, in which the definitions for type 1 MI, type 2 MI, and nonischemic myocardial injury are unified biochemically.

This version, published in 2018 in the European Heart Journal and Circulation, introduced a formal definition of myocardial injury, which was hailed as an innovation: cTn elevation to the 99th percentile of the upper limit of normal in a reference population.

It differentiates type 1 MI from type 2 MI by the separate pathophysiology of the ischemia – plaque rupture with intracoronary thrombosis and myocardial oxygen supply–demand mismatch, respectively. In both cases, however, there must be symptoms or objective evidence of ischemia. Absent signs of ischemia, the determination would be nonischemic myocardial injury.

Yet clinically and prognostically, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury in some ways are more similar to each other than either is to type 1 MI. Both occur secondary to other conditions across diverse clinical settings and can be a challenge to tell apart.

The universal definition’s perspective of the three events – so heavily dependent on cTn levels and myocardial ischemia – fails to account for the myriad complexities of individual patients in practice, some say, and so can muddle the process of risk assessment and therapy.

“Abnormal troponin identifies injury, but it doesn’t identify mechanism. Type 2 MI is highly prevalent, but there are other things that cause abnormal troponins,” Dr. Januzzi said. That’s why it’s important to explore and map out the clinical variables associated with the two conditions, to “understand who has a type 2 MI and who has cardiac injury. And believe it or not, it’s actually harder than it sounds to sort that out.”

“Practically speaking, the differentiation between these events is clinical,” Dr. Sandoval agreed. “There’s not always perfect agreement on what we’re calling what.”

Consequently, the universal definitions might categorize some events in ways that seem inconsistent from a management perspective. For example, they make a sharp distinction between coronary atherothrombotic and coronary nonatherothrombotic MI etiologies. Some clinicians would group MI caused by coronary spasm, coronary embolism, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection along with MI from coronary plaque rupture and thrombosis. But, Dr. Sandoval said, “even though these are coronary issues, they would fall into the type 2 bin.”

Also, about half of cases identified as type 2 MI are caused by tachyarrhythmias, which can elevate troponin and cause ECG changes and possibly symptoms resembling angina, Dr. Newby observed. “But that is completely different from other types of myocardial infarction, which are much more serious.”

So, “it’s a real mess of a diagnosis – acute myocardial injury, type 2 and type 1 MI – and it can be quite difficult to disentangle,” he said. “I think that the definition certainly has let us down.”

The diversity of type 2 MI clinical settings might also be a challenge. Myocardial injury according to cTn, with or without ischemia, occurs widely during critical illnesses and acute conditions, including respiratory distress, sepsis, internal bleeding, stroke, and pulmonary embolism.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, much was made of elevated troponin levels and myocarditis as an apparently frequent complication among hospitalized patients. “I raised my hand and said, we’ve been seeing abnormal troponins in people with influenza for 20 years,” Dr. Januzzi said. “Critical illness, infection, toxicity from drugs, from chemotherapy, from alcohol – there are all sorts of potential triggers of myocardial injury.”

Troponin ‘overdependence’

With many clinical settings in common and the presence or absence of myocardial ischemia to primarily distinguish them, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury both can be mistaken for the other. That can send management decisions in inappropriate directions.

A 2019 study looked at 633 cases that had been coded as type 2 MI at a major center and readjudicated them according to the fourth universal definition. Only 57% met all the type 2 criteria, 42% were reclassified as nonischemic myocardial injury, and a few were determined to have unstable angina.

“There’s overdependence on the easiest tool in the universal definition,” said Dr. Januzzi, a coauthor on that study. “Frequently people get seduced by the rise in a troponin value and immediately call it a myocardial infarction, lacking the other components of the universal definition that require evidence for coronary ischemia. That happens every day, where someone with an abnormal troponin is incorrectly branded as having an MI.”

It may not help that the current ICD-10-CM system features a diagnostic code for type 2 MI but not for myocardial injury.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” wrote Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, in a recent editorial. They caution against “using this code for myocardial injury because it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading,” thereby worsening the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

That potential suggests there could be a growing population of patients who have been told they had an MI, which then becomes part of their medical record, when, actually, they experienced nonischemic myocardial injury.

“Having seen this occur,” Dr. Januzzi explained, “it affects people emotionally to think they’ve had an MI. Precision in diagnosis is important, which is why the universal definition is so valuable. If people would adhere to it more assiduously, we could reduce the frequency of people getting a misdiagnosis of MI when in fact they had injury.”

Still, he added, “if someone has an illness severe enough to cause myocardial injury, they’re at risk for a bad outcome regardless of whether they did or didn’t have an MI.”

The uncertain role of angiography

Angiography isn’t ordered nearly as often for patients ultimately diagnosed with type 2 MI or myocardial injury as for those with type 1 MI. Type 2 MI can hit some patients who have remained symptom free despite possibly unrecognized obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) when myocardial demand is pushed past supply by a critical illness, tachyarrhythmia, or other acute conditions.

In such cases, “it’s reasonable to hypothesize that revascularization, something that really is not done in the vast majority of patients with type 2 MI, might actually be of benefit,” Dr. Januzzi said.

Whether these patients should routinely have angiography remains an open question. Without intervention, any newly identified obstructive CAD would continue to lurk in the background as a potential threat.

In efforts to differentiate type 2 MI from nonischemic injury, it can be “incredibly hard to know whether or not there’s actual ischemia in the mix. And that’s the only thing that defines the difference before taking an angiogram,” Derek P. Chew, MBBS, MPH, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, Australia, said in an interview.

Dr. Chew is principal investigator for the ongoing ACT-2 trial that is enrolling hospitalized, hemodynamically stable patients with cTn elevations but no suspicion of type 1 MI and “an unequivocal acute intercurrent diagnosis.” Qualifying diagnoses are prespecified on a list that includes sepsis, pneumonia, septicemia, a systemic inflammatory response, anemia, atrial tachycardia, acute kidney injury, and recent noncardiac surgery.

The patients are randomly assigned to a strategy of routine, usually invasive coronary angiography with discretionary revascularization, or to conservative care with noninvasive functional testing as appropriate. The sicker the patient, the greater the competing risk from other conditions and the less revascularization is likely to improve outcomes, Dr. Chew observed. Importantly, therefore, outcomes in the trial will be stratified by patient risk from comorbidities, measured with baseline GRACE and APACHE III scores.

Dr. Chew said the study aims to determine whether routine angiography is of benefit in patients at some identifiable level of risk, if not the whole range. One possible result, he said, is that there could be a risk-profile “sweet spot” associated with better outcomes in those assigned to angiography.

Enrollment in the trial started about 3 years ago, but “the process has been slow,” he said, because many potentially referring clinicians have a “bias on one side or another,” with about half of them preferring the angiography approach and the other half conservative management.

The unsettled role of drug therapy

With their often-complicated clinical profile, patients with type 2 MI or nonischemic myocardial injury tend to be medically undertreated, yet there is observational evidence they can benefit from familiar drug therapies.

In the previously noted cohort study of 3,800 younger patients with one of the three forms of myocardial injury, less than half of patients with type 2 MI received any form of CAD secondary prevention therapy at discharge, the researchers, with first author Avinainder Singh, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn, wrote.

The finding, consistent with Dr. Newby’s study from 2018, suggests that “categorizing the type of MI in young subjects might inform long-term cardiovascular prognosis,” and “emphasizes the need to identify and implement secondary prevention strategies to mitigate the high rate of cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 MI,” they concluded.

Further, outcomes varied with the number of discharge CV meds in an older cohort of patients with myocardial injury. Those with type 2 MI or acute or chronic nonischemic myocardial injury were far less likely than patients with type 1 MI to be prescribed guideline-based drugs. Survival was greater for those on two or three classes of CV medications, compared with one or none, in patients with acute or chronic nonischemic injury.

The investigators urged that patients with nonischemic myocardial injury or type 2 MI “be treated with cardiovascular medication to a larger degree than what is done today.”

When there is documented CAD in patients with type 2 MI, “it would be reasonable to suggest that preventative secondary prevention approaches, such as such lipid-reduction therapy or aspirin, would be beneficial,” Dr. Sandoval said. “But the reality is, there are no randomized trials, there are no prospective studies. ACT-2 is one of the few and early studies that’s really trying to address this.”

“The great majority of these people are not going to the cath lab, but when they do, there seems to be a signal of potential benefit,” Dr. Januzzi said. “For someone with a type 2 MI, it’s quite possible revascularization might help. Then more long-term treatment with medications that are proven in randomized trials to reduce risk would be a very plausible intervention.”

“We’ve actually proposed a number of potential therapeutic interventions to explore, both in people with type 2 MI and in people with injury without MI,” he said. “They might include sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. They might include antithrombotic therapy or more aggressive lipid lowering, possibly for the pleiotropic effects rather than the effects on atherosclerosis.”

Any such therapies that prove successful in well-designed trials could well earn both type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury, neglected as disorders in their own right, the kind of respect in clinical care pathways that they likely deserve.

Dr. Newby has disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Eli Lilly, Roche, Toshiba, Jansen, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, CellProthera, and Oncoarendi; and conducting research or receiving grants from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Inositec. Sandoval reports serving on an advisory board and as a speaker for Abbott Diagnostics and on an advisory board for Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Januzzi has disclosed receiving grant support from Novartis, Applied Therapeutics, and Innolife; consulting for Abbott Diagnostics, Janssen, Novartis, Quidel, and Roche Diagnostics; and serving on endpoint committees or data safety monitoring boards for trials supported by Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, CVRx, Janssen, MyoKardia, and Takeda. Dr. Chew has reported receiving grants from AstraZeneca and Edwards Life Sciences. ACT-2 is sponsored by the National Medical and Health Research Council of Australia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Survival gains in the management of acute myocardial infarction in recent decades don’t apply to one increasingly common category of MI.

Type 2 MI, triggered by a surge in myocardial oxygen demand or a drop in its supply, is on the rise and might be more prognostically serious than the “classic” atherothrombotic type 1 form, for which there have been such impressive strides in therapy.

Strategies for assessing and treating type 2 MI and another condition it can resemble clinically – nonischemic myocardial injury – have been less rigorously explored and are far less settled.

That could be partly because recent iterations of the consensus-based universal definition of MI define type 1 MI primarily by the atherothrombotic process, whereas “demand” type 2 MI is characterized as secondary to other disorders. The list of potential primary conditions, cardiac and noncardiac, is long.

As a result, patients with type 1 MI are clinically well defined, but those with type 2 MI have so far defied efforts to be clinically characterized in a consistent way. However, recent efforts might change that, given growing appreciation that all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality outcomes are actually worse for patients with type 2 MI.

“That’s because we have lots of treatments for type 1 MI. Type 2 and myocardial injury? We don’t know how to treat them,” David E. Newby, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, said in an interview.

Dr. Newby pointed to a widely cited 2018 publication, of which he is a coauthor, documenting 5-year outcomes of 2,122 patients with type 1 MI, type 2 MI, or nonischemic myocardial injury per the newly minted fourth universal definition.

Risk-factor profiles for patients with the latter two conditions contrasted with those of patients with type 1 MI, he observed. They were “a lot older,” were less likely to be smokers, had more hypertension and previous stroke, and a less prominent CV family history.

“So they’re a different beast,” Dr. Newby said. And their prognosis tended to be worse: all-cause mortality was about 62% for patients with type 2 MI and 72% with nonischemic myocardial injury, but only 37% for patients with type 1 MI. The difference between the two types of infarction was driven by an excess of noncardiovascular death after type 2 MI.

Mortality in patients with type 2 MI is “quite high, but it may well be a marker of the fact that you’ve got other serious diseases on board that are associated with poorer outcome,” he said.

Risk varies

The degree of risk in type 2 MI seems to vary with the underlying condition, a recent cohort study suggests. In about 3,800 patients with cardiac troponin (cTn) elevations qualifying as MI – a younger group; most were in their 30s and 40s – mortality at 10 years was 12% for those with type 1 MI, but 34% for those with type 2 MI and 46% for the remainder with nonischemic myocardial injury.

Underlying precipitating conditions varied widely among the patients with type 2 MI or nonischemic myocardial injury, and there was broad variation in mortality by etiology among those with type 2 MI. Sepsis and anemia entailed some of the highest risk, and hypertension and arrhythmias some of the lowest.

A prospective, community-based study of 5,460 patients with type 1 MI or type 2 MI reached a similar conclusion, but with a twist. Five-year all-cause mortality contrasted significantly between types of MI at 31% and 52%, respectively, but CV mortality rates were similar in this study.

Mortality in type 2 MI again varied by the precipitating etiology, suggesting that patients can be risk stratified according to pathophysiological mechanism behind their demand infarction, the authors concluded, “underscoring that type 2 MI is not a single entity, rather a group of phenotypic clusters.”

The usually high comorbidity burden and CV risk in patients with type 2 MI, one of those authors said in an interview, suggest there are “opportunities to see whether we can reduce that risk.”

Formal recommendations consistently say that, in patients with type 2 MI, “your first and foremost target should be to treat the underlying trigger and cause,” said Yader Sandoval, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. That means such opportunities for further CV risk reduction tend to be “underappreciated.”

“In principle, treating the inciting cause of type 2 MI or the injury is important,” said James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, in an interview, “but I feel quite strongly that there must be more that we can do for these folks.”

Dr. Januzzi is senior author on a recent analysis based on more than 200,000 admissions across the United States that saw a 43% lower risk for in-hospital death and 54% lower risk for 30-day MI readmission for patients with type 2 MI than those with type 1, adjusted for risk factors and comorbidities.

But, “it is important to emphasize that type 2 MI patients had a substantial risk for adverse outcome, nonetheless, and lack a clear management approach,” Dr. Januzzi and colleagues stated in their publication, as reported by this news organization.

“Due to the high rates of long-term cardiovascular events experienced by the frequently encountered type 2 MI patients,” they wrote, “identifying evidence-based therapies represents a major unmet need.”

That such patients tend to be sick with multiple comorbidities and have not yet been clinically well characterized, Dr. Januzzi said, “has stymied our ability to develop a treatment strategy.”

Role of the universal definitions

That challenge might in some ways be complicated by the universal definition, especially version 4, in which the definitions for type 1 MI, type 2 MI, and nonischemic myocardial injury are unified biochemically.

This version, published in 2018 in the European Heart Journal and Circulation, introduced a formal definition of myocardial injury, which was hailed as an innovation: cTn elevation to the 99th percentile of the upper limit of normal in a reference population.

It differentiates type 1 MI from type 2 MI by the separate pathophysiology of the ischemia – plaque rupture with intracoronary thrombosis and myocardial oxygen supply–demand mismatch, respectively. In both cases, however, there must be symptoms or objective evidence of ischemia. Absent signs of ischemia, the determination would be nonischemic myocardial injury.

Yet clinically and prognostically, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury in some ways are more similar to each other than either is to type 1 MI. Both occur secondary to other conditions across diverse clinical settings and can be a challenge to tell apart.

The universal definition’s perspective of the three events – so heavily dependent on cTn levels and myocardial ischemia – fails to account for the myriad complexities of individual patients in practice, some say, and so can muddle the process of risk assessment and therapy.

“Abnormal troponin identifies injury, but it doesn’t identify mechanism. Type 2 MI is highly prevalent, but there are other things that cause abnormal troponins,” Dr. Januzzi said. That’s why it’s important to explore and map out the clinical variables associated with the two conditions, to “understand who has a type 2 MI and who has cardiac injury. And believe it or not, it’s actually harder than it sounds to sort that out.”

“Practically speaking, the differentiation between these events is clinical,” Dr. Sandoval agreed. “There’s not always perfect agreement on what we’re calling what.”

Consequently, the universal definitions might categorize some events in ways that seem inconsistent from a management perspective. For example, they make a sharp distinction between coronary atherothrombotic and coronary nonatherothrombotic MI etiologies. Some clinicians would group MI caused by coronary spasm, coronary embolism, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection along with MI from coronary plaque rupture and thrombosis. But, Dr. Sandoval said, “even though these are coronary issues, they would fall into the type 2 bin.”

Also, about half of cases identified as type 2 MI are caused by tachyarrhythmias, which can elevate troponin and cause ECG changes and possibly symptoms resembling angina, Dr. Newby observed. “But that is completely different from other types of myocardial infarction, which are much more serious.”

So, “it’s a real mess of a diagnosis – acute myocardial injury, type 2 and type 1 MI – and it can be quite difficult to disentangle,” he said. “I think that the definition certainly has let us down.”

The diversity of type 2 MI clinical settings might also be a challenge. Myocardial injury according to cTn, with or without ischemia, occurs widely during critical illnesses and acute conditions, including respiratory distress, sepsis, internal bleeding, stroke, and pulmonary embolism.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, much was made of elevated troponin levels and myocarditis as an apparently frequent complication among hospitalized patients. “I raised my hand and said, we’ve been seeing abnormal troponins in people with influenza for 20 years,” Dr. Januzzi said. “Critical illness, infection, toxicity from drugs, from chemotherapy, from alcohol – there are all sorts of potential triggers of myocardial injury.”

Troponin ‘overdependence’

With many clinical settings in common and the presence or absence of myocardial ischemia to primarily distinguish them, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury both can be mistaken for the other. That can send management decisions in inappropriate directions.

A 2019 study looked at 633 cases that had been coded as type 2 MI at a major center and readjudicated them according to the fourth universal definition. Only 57% met all the type 2 criteria, 42% were reclassified as nonischemic myocardial injury, and a few were determined to have unstable angina.

“There’s overdependence on the easiest tool in the universal definition,” said Dr. Januzzi, a coauthor on that study. “Frequently people get seduced by the rise in a troponin value and immediately call it a myocardial infarction, lacking the other components of the universal definition that require evidence for coronary ischemia. That happens every day, where someone with an abnormal troponin is incorrectly branded as having an MI.”

It may not help that the current ICD-10-CM system features a diagnostic code for type 2 MI but not for myocardial injury.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” wrote Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, in a recent editorial. They caution against “using this code for myocardial injury because it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading,” thereby worsening the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

That potential suggests there could be a growing population of patients who have been told they had an MI, which then becomes part of their medical record, when, actually, they experienced nonischemic myocardial injury.

“Having seen this occur,” Dr. Januzzi explained, “it affects people emotionally to think they’ve had an MI. Precision in diagnosis is important, which is why the universal definition is so valuable. If people would adhere to it more assiduously, we could reduce the frequency of people getting a misdiagnosis of MI when in fact they had injury.”

Still, he added, “if someone has an illness severe enough to cause myocardial injury, they’re at risk for a bad outcome regardless of whether they did or didn’t have an MI.”

The uncertain role of angiography

Angiography isn’t ordered nearly as often for patients ultimately diagnosed with type 2 MI or myocardial injury as for those with type 1 MI. Type 2 MI can hit some patients who have remained symptom free despite possibly unrecognized obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) when myocardial demand is pushed past supply by a critical illness, tachyarrhythmia, or other acute conditions.

In such cases, “it’s reasonable to hypothesize that revascularization, something that really is not done in the vast majority of patients with type 2 MI, might actually be of benefit,” Dr. Januzzi said.

Whether these patients should routinely have angiography remains an open question. Without intervention, any newly identified obstructive CAD would continue to lurk in the background as a potential threat.

In efforts to differentiate type 2 MI from nonischemic injury, it can be “incredibly hard to know whether or not there’s actual ischemia in the mix. And that’s the only thing that defines the difference before taking an angiogram,” Derek P. Chew, MBBS, MPH, Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, Australia, said in an interview.

Dr. Chew is principal investigator for the ongoing ACT-2 trial that is enrolling hospitalized, hemodynamically stable patients with cTn elevations but no suspicion of type 1 MI and “an unequivocal acute intercurrent diagnosis.” Qualifying diagnoses are prespecified on a list that includes sepsis, pneumonia, septicemia, a systemic inflammatory response, anemia, atrial tachycardia, acute kidney injury, and recent noncardiac surgery.

The patients are randomly assigned to a strategy of routine, usually invasive coronary angiography with discretionary revascularization, or to conservative care with noninvasive functional testing as appropriate. The sicker the patient, the greater the competing risk from other conditions and the less revascularization is likely to improve outcomes, Dr. Chew observed. Importantly, therefore, outcomes in the trial will be stratified by patient risk from comorbidities, measured with baseline GRACE and APACHE III scores.

Dr. Chew said the study aims to determine whether routine angiography is of benefit in patients at some identifiable level of risk, if not the whole range. One possible result, he said, is that there could be a risk-profile “sweet spot” associated with better outcomes in those assigned to angiography.

Enrollment in the trial started about 3 years ago, but “the process has been slow,” he said, because many potentially referring clinicians have a “bias on one side or another,” with about half of them preferring the angiography approach and the other half conservative management.

The unsettled role of drug therapy

With their often-complicated clinical profile, patients with type 2 MI or nonischemic myocardial injury tend to be medically undertreated, yet there is observational evidence they can benefit from familiar drug therapies.

In the previously noted cohort study of 3,800 younger patients with one of the three forms of myocardial injury, less than half of patients with type 2 MI received any form of CAD secondary prevention therapy at discharge, the researchers, with first author Avinainder Singh, MD, from Yale University, New Haven, Conn, wrote.

The finding, consistent with Dr. Newby’s study from 2018, suggests that “categorizing the type of MI in young subjects might inform long-term cardiovascular prognosis,” and “emphasizes the need to identify and implement secondary prevention strategies to mitigate the high rate of cardiovascular death in patients with type 2 MI,” they concluded.

Further, outcomes varied with the number of discharge CV meds in an older cohort of patients with myocardial injury. Those with type 2 MI or acute or chronic nonischemic myocardial injury were far less likely than patients with type 1 MI to be prescribed guideline-based drugs. Survival was greater for those on two or three classes of CV medications, compared with one or none, in patients with acute or chronic nonischemic injury.

The investigators urged that patients with nonischemic myocardial injury or type 2 MI “be treated with cardiovascular medication to a larger degree than what is done today.”

When there is documented CAD in patients with type 2 MI, “it would be reasonable to suggest that preventative secondary prevention approaches, such as such lipid-reduction therapy or aspirin, would be beneficial,” Dr. Sandoval said. “But the reality is, there are no randomized trials, there are no prospective studies. ACT-2 is one of the few and early studies that’s really trying to address this.”

“The great majority of these people are not going to the cath lab, but when they do, there seems to be a signal of potential benefit,” Dr. Januzzi said. “For someone with a type 2 MI, it’s quite possible revascularization might help. Then more long-term treatment with medications that are proven in randomized trials to reduce risk would be a very plausible intervention.”

“We’ve actually proposed a number of potential therapeutic interventions to explore, both in people with type 2 MI and in people with injury without MI,” he said. “They might include sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. They might include antithrombotic therapy or more aggressive lipid lowering, possibly for the pleiotropic effects rather than the effects on atherosclerosis.”

Any such therapies that prove successful in well-designed trials could well earn both type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury, neglected as disorders in their own right, the kind of respect in clinical care pathways that they likely deserve.

Dr. Newby has disclosed receiving consulting fees or honoraria from Eli Lilly, Roche, Toshiba, Jansen, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, CellProthera, and Oncoarendi; and conducting research or receiving grants from Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Inositec. Sandoval reports serving on an advisory board and as a speaker for Abbott Diagnostics and on an advisory board for Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Januzzi has disclosed receiving grant support from Novartis, Applied Therapeutics, and Innolife; consulting for Abbott Diagnostics, Janssen, Novartis, Quidel, and Roche Diagnostics; and serving on endpoint committees or data safety monitoring boards for trials supported by Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, CVRx, Janssen, MyoKardia, and Takeda. Dr. Chew has reported receiving grants from AstraZeneca and Edwards Life Sciences. ACT-2 is sponsored by the National Medical and Health Research Council of Australia.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Survival gains in the management of acute myocardial infarction in recent decades don’t apply to one increasingly common category of MI.

Type 2 MI, triggered by a surge in myocardial oxygen demand or a drop in its supply, is on the rise and might be more prognostically serious than the “classic” atherothrombotic type 1 form, for which there have been such impressive strides in therapy.

Strategies for assessing and treating type 2 MI and another condition it can resemble clinically – nonischemic myocardial injury – have been less rigorously explored and are far less settled.

That could be partly because recent iterations of the consensus-based universal definition of MI define type 1 MI primarily by the atherothrombotic process, whereas “demand” type 2 MI is characterized as secondary to other disorders. The list of potential primary conditions, cardiac and noncardiac, is long.

As a result, patients with type 1 MI are clinically well defined, but those with type 2 MI have so far defied efforts to be clinically characterized in a consistent way. However, recent efforts might change that, given growing appreciation that all-cause and cardiovascular (CV) mortality outcomes are actually worse for patients with type 2 MI.

“That’s because we have lots of treatments for type 1 MI. Type 2 and myocardial injury? We don’t know how to treat them,” David E. Newby, MD, PhD, University of Edinburgh, said in an interview.

Dr. Newby pointed to a widely cited 2018 publication, of which he is a coauthor, documenting 5-year outcomes of 2,122 patients with type 1 MI, type 2 MI, or nonischemic myocardial injury per the newly minted fourth universal definition.

Risk-factor profiles for patients with the latter two conditions contrasted with those of patients with type 1 MI, he observed. They were “a lot older,” were less likely to be smokers, had more hypertension and previous stroke, and a less prominent CV family history.

“So they’re a different beast,” Dr. Newby said. And their prognosis tended to be worse: all-cause mortality was about 62% for patients with type 2 MI and 72% with nonischemic myocardial injury, but only 37% for patients with type 1 MI. The difference between the two types of infarction was driven by an excess of noncardiovascular death after type 2 MI.

Mortality in patients with type 2 MI is “quite high, but it may well be a marker of the fact that you’ve got other serious diseases on board that are associated with poorer outcome,” he said.

Risk varies

The degree of risk in type 2 MI seems to vary with the underlying condition, a recent cohort study suggests. In about 3,800 patients with cardiac troponin (cTn) elevations qualifying as MI – a younger group; most were in their 30s and 40s – mortality at 10 years was 12% for those with type 1 MI, but 34% for those with type 2 MI and 46% for the remainder with nonischemic myocardial injury.

Underlying precipitating conditions varied widely among the patients with type 2 MI or nonischemic myocardial injury, and there was broad variation in mortality by etiology among those with type 2 MI. Sepsis and anemia entailed some of the highest risk, and hypertension and arrhythmias some of the lowest.

A prospective, community-based study of 5,460 patients with type 1 MI or type 2 MI reached a similar conclusion, but with a twist. Five-year all-cause mortality contrasted significantly between types of MI at 31% and 52%, respectively, but CV mortality rates were similar in this study.

Mortality in type 2 MI again varied by the precipitating etiology, suggesting that patients can be risk stratified according to pathophysiological mechanism behind their demand infarction, the authors concluded, “underscoring that type 2 MI is not a single entity, rather a group of phenotypic clusters.”

The usually high comorbidity burden and CV risk in patients with type 2 MI, one of those authors said in an interview, suggest there are “opportunities to see whether we can reduce that risk.”

Formal recommendations consistently say that, in patients with type 2 MI, “your first and foremost target should be to treat the underlying trigger and cause,” said Yader Sandoval, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. That means such opportunities for further CV risk reduction tend to be “underappreciated.”

“In principle, treating the inciting cause of type 2 MI or the injury is important,” said James L. Januzzi, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, in an interview, “but I feel quite strongly that there must be more that we can do for these folks.”

Dr. Januzzi is senior author on a recent analysis based on more than 200,000 admissions across the United States that saw a 43% lower risk for in-hospital death and 54% lower risk for 30-day MI readmission for patients with type 2 MI than those with type 1, adjusted for risk factors and comorbidities.

But, “it is important to emphasize that type 2 MI patients had a substantial risk for adverse outcome, nonetheless, and lack a clear management approach,” Dr. Januzzi and colleagues stated in their publication, as reported by this news organization.

“Due to the high rates of long-term cardiovascular events experienced by the frequently encountered type 2 MI patients,” they wrote, “identifying evidence-based therapies represents a major unmet need.”

That such patients tend to be sick with multiple comorbidities and have not yet been clinically well characterized, Dr. Januzzi said, “has stymied our ability to develop a treatment strategy.”

Role of the universal definitions

That challenge might in some ways be complicated by the universal definition, especially version 4, in which the definitions for type 1 MI, type 2 MI, and nonischemic myocardial injury are unified biochemically.

This version, published in 2018 in the European Heart Journal and Circulation, introduced a formal definition of myocardial injury, which was hailed as an innovation: cTn elevation to the 99th percentile of the upper limit of normal in a reference population.

It differentiates type 1 MI from type 2 MI by the separate pathophysiology of the ischemia – plaque rupture with intracoronary thrombosis and myocardial oxygen supply–demand mismatch, respectively. In both cases, however, there must be symptoms or objective evidence of ischemia. Absent signs of ischemia, the determination would be nonischemic myocardial injury.

Yet clinically and prognostically, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury in some ways are more similar to each other than either is to type 1 MI. Both occur secondary to other conditions across diverse clinical settings and can be a challenge to tell apart.

The universal definition’s perspective of the three events – so heavily dependent on cTn levels and myocardial ischemia – fails to account for the myriad complexities of individual patients in practice, some say, and so can muddle the process of risk assessment and therapy.

“Abnormal troponin identifies injury, but it doesn’t identify mechanism. Type 2 MI is highly prevalent, but there are other things that cause abnormal troponins,” Dr. Januzzi said. That’s why it’s important to explore and map out the clinical variables associated with the two conditions, to “understand who has a type 2 MI and who has cardiac injury. And believe it or not, it’s actually harder than it sounds to sort that out.”

“Practically speaking, the differentiation between these events is clinical,” Dr. Sandoval agreed. “There’s not always perfect agreement on what we’re calling what.”

Consequently, the universal definitions might categorize some events in ways that seem inconsistent from a management perspective. For example, they make a sharp distinction between coronary atherothrombotic and coronary nonatherothrombotic MI etiologies. Some clinicians would group MI caused by coronary spasm, coronary embolism, or spontaneous coronary artery dissection along with MI from coronary plaque rupture and thrombosis. But, Dr. Sandoval said, “even though these are coronary issues, they would fall into the type 2 bin.”

Also, about half of cases identified as type 2 MI are caused by tachyarrhythmias, which can elevate troponin and cause ECG changes and possibly symptoms resembling angina, Dr. Newby observed. “But that is completely different from other types of myocardial infarction, which are much more serious.”

So, “it’s a real mess of a diagnosis – acute myocardial injury, type 2 and type 1 MI – and it can be quite difficult to disentangle,” he said. “I think that the definition certainly has let us down.”

The diversity of type 2 MI clinical settings might also be a challenge. Myocardial injury according to cTn, with or without ischemia, occurs widely during critical illnesses and acute conditions, including respiratory distress, sepsis, internal bleeding, stroke, and pulmonary embolism.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, much was made of elevated troponin levels and myocarditis as an apparently frequent complication among hospitalized patients. “I raised my hand and said, we’ve been seeing abnormal troponins in people with influenza for 20 years,” Dr. Januzzi said. “Critical illness, infection, toxicity from drugs, from chemotherapy, from alcohol – there are all sorts of potential triggers of myocardial injury.”

Troponin ‘overdependence’

With many clinical settings in common and the presence or absence of myocardial ischemia to primarily distinguish them, type 2 MI and nonischemic myocardial injury both can be mistaken for the other. That can send management decisions in inappropriate directions.

A 2019 study looked at 633 cases that had been coded as type 2 MI at a major center and readjudicated them according to the fourth universal definition. Only 57% met all the type 2 criteria, 42% were reclassified as nonischemic myocardial injury, and a few were determined to have unstable angina.

“There’s overdependence on the easiest tool in the universal definition,” said Dr. Januzzi, a coauthor on that study. “Frequently people get seduced by the rise in a troponin value and immediately call it a myocardial infarction, lacking the other components of the universal definition that require evidence for coronary ischemia. That happens every day, where someone with an abnormal troponin is incorrectly branded as having an MI.”

It may not help that the current ICD-10-CM system features a diagnostic code for type 2 MI but not for myocardial injury.

“Instead, the new ICD-10-CM coding includes a proxy called ‘non-MI troponin elevation due to an underlying cause,’ ” wrote Kristian Thygesen, MD, DSc, and Allan S. Jaffe, MD, in a recent editorial. They caution against “using this code for myocardial injury because it is not specific for an elevated cTn value and could represent any abnormal laboratory measurements.” The code could be “misleading,” thereby worsening the potential for miscoding and “misattribution of MI diagnoses.”

That potential suggests there could be a growing population of patients who have been told they had an MI, which then becomes part of their medical record, when, actually, they experienced nonischemic myocardial injury.

“Having seen this occur,” Dr. Januzzi explained, “it affects people emotionally to think they’ve had an MI. Precision in diagnosis is important, which is why the universal definition is so valuable. If people would adhere to it more assiduously, we could reduce the frequency of people getting a misdiagnosis of MI when in fact they had injury.”

Still, he added, “if someone has an illness severe enough to cause myocardial injury, they’re at risk for a bad outcome regardless of whether they did or didn’t have an MI.”

The uncertain role of angiography