User login

Poop Doesn’t Lie: What Fecal ‘Forensics’ Tells Us About Diet

A lightbulb moment hit as Lawrence David was chatting one day with an ecologist who studies the microbiomes and diets of large herbivores in the African savanna. David was envious. He’d been studying the human microbiome, and this ecologist had tons of animal statistics that were way more specific than what David had obtained from people.

“How on earth do you get all these dietary data?” David recalled asking. “Obviously, he didn’t ask the animals what they ate.”

All those specific statistics came from DNA sequencing of animal scat scooped up from the savanna.

Indeed.

Depending on when you read this, you may have the DNA of more than a dozen plant species, plus another three or four animal species, gurgling through your gut. That’s the straight poop taken straight from, well, poop.

Diet, DNA, and Feces

Everything we eat (except vitamins, minerals, and salt) came from something that was living, and all living things have genomes.

“A decent fraction of that DNA” goes undigested and is then excreted, said David, a PhD and associate professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

“We are using DNA sequencing to reconstruct what people eat,” David said. “We try to see if there are patterns in what people eat and how we can measure them by DNA, or kind of genetic forensics.” Then they connect that data to health outcomes like obesity.

A typical person’s excrement probably contains the DNA of 10-20 plant species and three or four types of animal DNA. “And that’s the average person. Some people may have more like 40 types at any given time,” David said.

Studying DNA in human feces has potential applications in research and in clinical settings. For instance, it could help design personalized nutrition strategies for patients, something that’s already being tested. He hopes that DNA information will help “connect patterns in what people eat to their microbiomes.”

One big advantage: Feces don’t lie. In reconstructing someone’s diet, people either forget what they ate, fudge the truth, or can’t be bothered to keep track.

“Patients report the fruit they ate yesterday but not the M&Ms,” said Neil Stollman, MD, chief of the division of gastroenterology at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, California.

Some people can’t write it all down because they’re too old or too young — the very people at highest risk of nutrition-associated disease, said David.

Fetching and Figuring Out Feces

It’s a lot of work to collect and analyze fecal matter, for ethical, legal, and logistical reasons. “And then there’s sort of an ick factor to this kind of work,” David said.

To get samples, people place a plastic collection cup under the toilet seat to catch the stool. The person then swabs or scoops some of that into a tube, seals the top, and either brings it in or mails it to the lab.

In the lab, David said, “if the DNA is still inside the plant cells, we crack the cells open using a variety of methods. We use what’s called ‘a stomacher,’ which is like two big paddles, and we load the poop [which is in a plastic bag] into it and then squash it — mash it up. We also sometimes load small particles of what is basically glass into it and then shake really hard — it is another way you can physically break open the plant cells. This can also be done with chemicals. It’s like a chemistry lab,” he said, noting that this process takes about half a day to do.

There is much more bacterial DNA in stool than there is food DNA, and even a little human DNA and sometimes fungi, said David. “The concentration of bacteria in stool is amongst the highest concentrations of bacteria on the planet,” he said, but his lab focuses on the plant DNA they find.

They use a molecular process called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that amplifies and selectively copies DNA from plants. (The scientists who invented this “ingenious” process won a Nobel Prize, David noted.) Like a COVID PCR test, the process only matches up for certain kinds of DNA and can be designed to be more specific or less specific. In David’s lab, they shoot for a middle ground of specificity, where the PCR process is targeting chloroplasts in plants.

Once they’ve detected all the different sequences of food species, they need to find the DNA code, a time-consuming step. His colleague Briana Petrone compiled a reference database of specific sequences of DNA that correspond to different species of plants. This work took more than a year, said David, noting that only a handful of other labs around the country are sequencing DNA in feces, most of them looking at it in animals, not humans.

There are 200,000 to 300,000 species of edible plants estimated to be on the planet, he said. “I think historically, humans have eaten about 7000 of them. We’re kind of like a walking repository of all this genetic material.”

What Scientists Learn from Fecal DNA

Tracking DNA in digested food can provide valuable data to researchers — information that could have a major impact on nutritional guidance for people with obesity and digestive diseases and other gastrointestinal and nutrition-related issues.

David and Petrone’s 2023 study analyzing DNA in stool samples, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), showed what — and roughly how much — people ate.

They noticed that kids with obesity had a higher diversity of plants in them than kids without obesity. Sounds backward — wouldn’t a child who eats more plants be a healthier weight? “The more I dug into it, it turns out that foods that are more processed often tend to have more ingredients. So, a Big Mac and fries and a coffee have 19 different plant species,” said David.

Going forward, he said, researchers may have to be “more specific about how we think about dietary diversity. Maybe not all plant species count toward health in the same way.”

David’s work provides an innovative way to conduct nutrition research, said Jotham Suez, PhD, an assistant professor in the department of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“We need to have some means of tracking what people actually ate during a study, whether it’s an intervention where we provide them with the food or an observational study where we let people eat their habitual diet and track it themselves,” said Suez, who studies the gut microbiome.

“Recall bias” makes food questionnaires and apps unreliable. And research suggests that some participants may underreport food intake, possibly because they don’t want to be judged or they misestimate how much they actually consumed.

“There’s huge promise” with a tool like the one described in the PNAS study for making connections between diet and disease, Suez said. But access may be an issue for many researchers. He expects techniques to improve and costs to go down, but there will be challenges. “This method is also almost exclusively looking at plant DNA material, Suez added, “and our diets contain multiple components that are not plants.”

And even if a person just eats an apple or a single cucumber, that food may be degraded somewhere else in the gut, and it may be digested differently in different people’s guts. “Metabolism, of course, can be different between people,” Suez said, so the amounts of data will vary. “In their study, the qualitative data is convincing. The quantitative is TBD [to be determined].”

But he said it might be “a perfect tool” for scientists who want to study indigestible fiber, which is an important area of science, too.

“I totally buy it as a potentially better way to do dietary analytics for disease associations,” said Stollman, an expert in fecal transplant and diverticulitis and a trustee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Stollman sees many patients with diverticular disease who could benefit.

“One of the core questions in the diverticular world is, what causes diverticular disease, so we can ideally prevent it? For decades, the theory has been that a low fiber diet contributes to it,” said Stollman, but testing DNA in patients’ stools could help researchers explore the question in a new and potentially more nuanced and accurate way. Findings might allow scientists to learn, “Do people who eat X get polyps? Is this diet a risk factor for X, Y, or Z disease?” said Stollman.

Future Clinical Applications

Brenda Davy, PhD, is a registered dietitian and professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Tech. She conducts research investigating the role of diet in the prevention and treatment of obesity and related conditions such as type 2 diabetes. She also develops dietary assessment methods. More than a decade ago, she developed one of the first rapid assessment tools for quantifying beverage intake — the Beverage Intake Questionnaire — an assessment that is still used today.

“Dietary assessment is necessary in both research and clinical settings,” Davy said. “If a physician diagnoses a patient with a certain condition, information about the patient’s usual dietary habits can help him or her prescribe dietary changes that may help treat that condition.”

Biospecimens, like fecal and urine samples, can be a safe, accurate way to collect that data, she said. Samples can be obtained easily and noninvasively “in a wide variety of populations such as children or older adults” and in clinical settings.

Davy and her team use David’s technology in their work — in particular, a tool called FoodSeq that applies DNA metabarcoding to human stool to collect information about food taxa consumed. Their two labs are now collaborating on a project investigating how ultraprocessed foods might impact type 2 diabetes risk and cardiovascular health.

There are many directions David’s lab would like to take their research, possibly partnering with epidemiologists on global studies that would help them expand their DNA database and better understand how, for example, climate change may be affecting diet diversity and to learn more about diet across different populations.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A lightbulb moment hit as Lawrence David was chatting one day with an ecologist who studies the microbiomes and diets of large herbivores in the African savanna. David was envious. He’d been studying the human microbiome, and this ecologist had tons of animal statistics that were way more specific than what David had obtained from people.

“How on earth do you get all these dietary data?” David recalled asking. “Obviously, he didn’t ask the animals what they ate.”

All those specific statistics came from DNA sequencing of animal scat scooped up from the savanna.

Indeed.

Depending on when you read this, you may have the DNA of more than a dozen plant species, plus another three or four animal species, gurgling through your gut. That’s the straight poop taken straight from, well, poop.

Diet, DNA, and Feces

Everything we eat (except vitamins, minerals, and salt) came from something that was living, and all living things have genomes.

“A decent fraction of that DNA” goes undigested and is then excreted, said David, a PhD and associate professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

“We are using DNA sequencing to reconstruct what people eat,” David said. “We try to see if there are patterns in what people eat and how we can measure them by DNA, or kind of genetic forensics.” Then they connect that data to health outcomes like obesity.

A typical person’s excrement probably contains the DNA of 10-20 plant species and three or four types of animal DNA. “And that’s the average person. Some people may have more like 40 types at any given time,” David said.

Studying DNA in human feces has potential applications in research and in clinical settings. For instance, it could help design personalized nutrition strategies for patients, something that’s already being tested. He hopes that DNA information will help “connect patterns in what people eat to their microbiomes.”

One big advantage: Feces don’t lie. In reconstructing someone’s diet, people either forget what they ate, fudge the truth, or can’t be bothered to keep track.

“Patients report the fruit they ate yesterday but not the M&Ms,” said Neil Stollman, MD, chief of the division of gastroenterology at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, California.

Some people can’t write it all down because they’re too old or too young — the very people at highest risk of nutrition-associated disease, said David.

Fetching and Figuring Out Feces

It’s a lot of work to collect and analyze fecal matter, for ethical, legal, and logistical reasons. “And then there’s sort of an ick factor to this kind of work,” David said.

To get samples, people place a plastic collection cup under the toilet seat to catch the stool. The person then swabs or scoops some of that into a tube, seals the top, and either brings it in or mails it to the lab.

In the lab, David said, “if the DNA is still inside the plant cells, we crack the cells open using a variety of methods. We use what’s called ‘a stomacher,’ which is like two big paddles, and we load the poop [which is in a plastic bag] into it and then squash it — mash it up. We also sometimes load small particles of what is basically glass into it and then shake really hard — it is another way you can physically break open the plant cells. This can also be done with chemicals. It’s like a chemistry lab,” he said, noting that this process takes about half a day to do.

There is much more bacterial DNA in stool than there is food DNA, and even a little human DNA and sometimes fungi, said David. “The concentration of bacteria in stool is amongst the highest concentrations of bacteria on the planet,” he said, but his lab focuses on the plant DNA they find.

They use a molecular process called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that amplifies and selectively copies DNA from plants. (The scientists who invented this “ingenious” process won a Nobel Prize, David noted.) Like a COVID PCR test, the process only matches up for certain kinds of DNA and can be designed to be more specific or less specific. In David’s lab, they shoot for a middle ground of specificity, where the PCR process is targeting chloroplasts in plants.

Once they’ve detected all the different sequences of food species, they need to find the DNA code, a time-consuming step. His colleague Briana Petrone compiled a reference database of specific sequences of DNA that correspond to different species of plants. This work took more than a year, said David, noting that only a handful of other labs around the country are sequencing DNA in feces, most of them looking at it in animals, not humans.

There are 200,000 to 300,000 species of edible plants estimated to be on the planet, he said. “I think historically, humans have eaten about 7000 of them. We’re kind of like a walking repository of all this genetic material.”

What Scientists Learn from Fecal DNA

Tracking DNA in digested food can provide valuable data to researchers — information that could have a major impact on nutritional guidance for people with obesity and digestive diseases and other gastrointestinal and nutrition-related issues.

David and Petrone’s 2023 study analyzing DNA in stool samples, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), showed what — and roughly how much — people ate.

They noticed that kids with obesity had a higher diversity of plants in them than kids without obesity. Sounds backward — wouldn’t a child who eats more plants be a healthier weight? “The more I dug into it, it turns out that foods that are more processed often tend to have more ingredients. So, a Big Mac and fries and a coffee have 19 different plant species,” said David.

Going forward, he said, researchers may have to be “more specific about how we think about dietary diversity. Maybe not all plant species count toward health in the same way.”

David’s work provides an innovative way to conduct nutrition research, said Jotham Suez, PhD, an assistant professor in the department of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“We need to have some means of tracking what people actually ate during a study, whether it’s an intervention where we provide them with the food or an observational study where we let people eat their habitual diet and track it themselves,” said Suez, who studies the gut microbiome.

“Recall bias” makes food questionnaires and apps unreliable. And research suggests that some participants may underreport food intake, possibly because they don’t want to be judged or they misestimate how much they actually consumed.

“There’s huge promise” with a tool like the one described in the PNAS study for making connections between diet and disease, Suez said. But access may be an issue for many researchers. He expects techniques to improve and costs to go down, but there will be challenges. “This method is also almost exclusively looking at plant DNA material, Suez added, “and our diets contain multiple components that are not plants.”

And even if a person just eats an apple or a single cucumber, that food may be degraded somewhere else in the gut, and it may be digested differently in different people’s guts. “Metabolism, of course, can be different between people,” Suez said, so the amounts of data will vary. “In their study, the qualitative data is convincing. The quantitative is TBD [to be determined].”

But he said it might be “a perfect tool” for scientists who want to study indigestible fiber, which is an important area of science, too.

“I totally buy it as a potentially better way to do dietary analytics for disease associations,” said Stollman, an expert in fecal transplant and diverticulitis and a trustee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Stollman sees many patients with diverticular disease who could benefit.

“One of the core questions in the diverticular world is, what causes diverticular disease, so we can ideally prevent it? For decades, the theory has been that a low fiber diet contributes to it,” said Stollman, but testing DNA in patients’ stools could help researchers explore the question in a new and potentially more nuanced and accurate way. Findings might allow scientists to learn, “Do people who eat X get polyps? Is this diet a risk factor for X, Y, or Z disease?” said Stollman.

Future Clinical Applications

Brenda Davy, PhD, is a registered dietitian and professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Tech. She conducts research investigating the role of diet in the prevention and treatment of obesity and related conditions such as type 2 diabetes. She also develops dietary assessment methods. More than a decade ago, she developed one of the first rapid assessment tools for quantifying beverage intake — the Beverage Intake Questionnaire — an assessment that is still used today.

“Dietary assessment is necessary in both research and clinical settings,” Davy said. “If a physician diagnoses a patient with a certain condition, information about the patient’s usual dietary habits can help him or her prescribe dietary changes that may help treat that condition.”

Biospecimens, like fecal and urine samples, can be a safe, accurate way to collect that data, she said. Samples can be obtained easily and noninvasively “in a wide variety of populations such as children or older adults” and in clinical settings.

Davy and her team use David’s technology in their work — in particular, a tool called FoodSeq that applies DNA metabarcoding to human stool to collect information about food taxa consumed. Their two labs are now collaborating on a project investigating how ultraprocessed foods might impact type 2 diabetes risk and cardiovascular health.

There are many directions David’s lab would like to take their research, possibly partnering with epidemiologists on global studies that would help them expand their DNA database and better understand how, for example, climate change may be affecting diet diversity and to learn more about diet across different populations.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A lightbulb moment hit as Lawrence David was chatting one day with an ecologist who studies the microbiomes and diets of large herbivores in the African savanna. David was envious. He’d been studying the human microbiome, and this ecologist had tons of animal statistics that were way more specific than what David had obtained from people.

“How on earth do you get all these dietary data?” David recalled asking. “Obviously, he didn’t ask the animals what they ate.”

All those specific statistics came from DNA sequencing of animal scat scooped up from the savanna.

Indeed.

Depending on when you read this, you may have the DNA of more than a dozen plant species, plus another three or four animal species, gurgling through your gut. That’s the straight poop taken straight from, well, poop.

Diet, DNA, and Feces

Everything we eat (except vitamins, minerals, and salt) came from something that was living, and all living things have genomes.

“A decent fraction of that DNA” goes undigested and is then excreted, said David, a PhD and associate professor of molecular genetics and microbiology at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

“We are using DNA sequencing to reconstruct what people eat,” David said. “We try to see if there are patterns in what people eat and how we can measure them by DNA, or kind of genetic forensics.” Then they connect that data to health outcomes like obesity.

A typical person’s excrement probably contains the DNA of 10-20 plant species and three or four types of animal DNA. “And that’s the average person. Some people may have more like 40 types at any given time,” David said.

Studying DNA in human feces has potential applications in research and in clinical settings. For instance, it could help design personalized nutrition strategies for patients, something that’s already being tested. He hopes that DNA information will help “connect patterns in what people eat to their microbiomes.”

One big advantage: Feces don’t lie. In reconstructing someone’s diet, people either forget what they ate, fudge the truth, or can’t be bothered to keep track.

“Patients report the fruit they ate yesterday but not the M&Ms,” said Neil Stollman, MD, chief of the division of gastroenterology at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Oakland, California.

Some people can’t write it all down because they’re too old or too young — the very people at highest risk of nutrition-associated disease, said David.

Fetching and Figuring Out Feces

It’s a lot of work to collect and analyze fecal matter, for ethical, legal, and logistical reasons. “And then there’s sort of an ick factor to this kind of work,” David said.

To get samples, people place a plastic collection cup under the toilet seat to catch the stool. The person then swabs or scoops some of that into a tube, seals the top, and either brings it in or mails it to the lab.

In the lab, David said, “if the DNA is still inside the plant cells, we crack the cells open using a variety of methods. We use what’s called ‘a stomacher,’ which is like two big paddles, and we load the poop [which is in a plastic bag] into it and then squash it — mash it up. We also sometimes load small particles of what is basically glass into it and then shake really hard — it is another way you can physically break open the plant cells. This can also be done with chemicals. It’s like a chemistry lab,” he said, noting that this process takes about half a day to do.

There is much more bacterial DNA in stool than there is food DNA, and even a little human DNA and sometimes fungi, said David. “The concentration of bacteria in stool is amongst the highest concentrations of bacteria on the planet,” he said, but his lab focuses on the plant DNA they find.

They use a molecular process called polymerase chain reaction (PCR) that amplifies and selectively copies DNA from plants. (The scientists who invented this “ingenious” process won a Nobel Prize, David noted.) Like a COVID PCR test, the process only matches up for certain kinds of DNA and can be designed to be more specific or less specific. In David’s lab, they shoot for a middle ground of specificity, where the PCR process is targeting chloroplasts in plants.

Once they’ve detected all the different sequences of food species, they need to find the DNA code, a time-consuming step. His colleague Briana Petrone compiled a reference database of specific sequences of DNA that correspond to different species of plants. This work took more than a year, said David, noting that only a handful of other labs around the country are sequencing DNA in feces, most of them looking at it in animals, not humans.

There are 200,000 to 300,000 species of edible plants estimated to be on the planet, he said. “I think historically, humans have eaten about 7000 of them. We’re kind of like a walking repository of all this genetic material.”

What Scientists Learn from Fecal DNA

Tracking DNA in digested food can provide valuable data to researchers — information that could have a major impact on nutritional guidance for people with obesity and digestive diseases and other gastrointestinal and nutrition-related issues.

David and Petrone’s 2023 study analyzing DNA in stool samples, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), showed what — and roughly how much — people ate.

They noticed that kids with obesity had a higher diversity of plants in them than kids without obesity. Sounds backward — wouldn’t a child who eats more plants be a healthier weight? “The more I dug into it, it turns out that foods that are more processed often tend to have more ingredients. So, a Big Mac and fries and a coffee have 19 different plant species,” said David.

Going forward, he said, researchers may have to be “more specific about how we think about dietary diversity. Maybe not all plant species count toward health in the same way.”

David’s work provides an innovative way to conduct nutrition research, said Jotham Suez, PhD, an assistant professor in the department of molecular microbiology and immunology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“We need to have some means of tracking what people actually ate during a study, whether it’s an intervention where we provide them with the food or an observational study where we let people eat their habitual diet and track it themselves,” said Suez, who studies the gut microbiome.

“Recall bias” makes food questionnaires and apps unreliable. And research suggests that some participants may underreport food intake, possibly because they don’t want to be judged or they misestimate how much they actually consumed.

“There’s huge promise” with a tool like the one described in the PNAS study for making connections between diet and disease, Suez said. But access may be an issue for many researchers. He expects techniques to improve and costs to go down, but there will be challenges. “This method is also almost exclusively looking at plant DNA material, Suez added, “and our diets contain multiple components that are not plants.”

And even if a person just eats an apple or a single cucumber, that food may be degraded somewhere else in the gut, and it may be digested differently in different people’s guts. “Metabolism, of course, can be different between people,” Suez said, so the amounts of data will vary. “In their study, the qualitative data is convincing. The quantitative is TBD [to be determined].”

But he said it might be “a perfect tool” for scientists who want to study indigestible fiber, which is an important area of science, too.

“I totally buy it as a potentially better way to do dietary analytics for disease associations,” said Stollman, an expert in fecal transplant and diverticulitis and a trustee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Stollman sees many patients with diverticular disease who could benefit.

“One of the core questions in the diverticular world is, what causes diverticular disease, so we can ideally prevent it? For decades, the theory has been that a low fiber diet contributes to it,” said Stollman, but testing DNA in patients’ stools could help researchers explore the question in a new and potentially more nuanced and accurate way. Findings might allow scientists to learn, “Do people who eat X get polyps? Is this diet a risk factor for X, Y, or Z disease?” said Stollman.

Future Clinical Applications

Brenda Davy, PhD, is a registered dietitian and professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Tech. She conducts research investigating the role of diet in the prevention and treatment of obesity and related conditions such as type 2 diabetes. She also develops dietary assessment methods. More than a decade ago, she developed one of the first rapid assessment tools for quantifying beverage intake — the Beverage Intake Questionnaire — an assessment that is still used today.

“Dietary assessment is necessary in both research and clinical settings,” Davy said. “If a physician diagnoses a patient with a certain condition, information about the patient’s usual dietary habits can help him or her prescribe dietary changes that may help treat that condition.”

Biospecimens, like fecal and urine samples, can be a safe, accurate way to collect that data, she said. Samples can be obtained easily and noninvasively “in a wide variety of populations such as children or older adults” and in clinical settings.

Davy and her team use David’s technology in their work — in particular, a tool called FoodSeq that applies DNA metabarcoding to human stool to collect information about food taxa consumed. Their two labs are now collaborating on a project investigating how ultraprocessed foods might impact type 2 diabetes risk and cardiovascular health.

There are many directions David’s lab would like to take their research, possibly partnering with epidemiologists on global studies that would help them expand their DNA database and better understand how, for example, climate change may be affecting diet diversity and to learn more about diet across different populations.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Do Adults With Obesity Feel Pain More Intensely?

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Adults with excess weight or obesity tend to experience higher levels of pain intensity than those with a normal weight, highlighting the importance of addressing obesity as part of pain management strategies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Recent studies suggest that obesity may change pain perception and worsen existing painful conditions.

- To examine the association between overweight or obesity and self-perceived pain intensities, researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 22 studies that included 31,210 adults older than 18 years and from diverse international cohorts.

- The participants were categorized by body mass index (BMI) as being normal weight (18.5-24.9), overweight (25.0-29.9), and obese (≥ 30). A BMI ≥ 25 was considered excess weight.

- Pain intensity was assessed by self-report using the Visual Analog Scale, Numerical Rating Scale, and Numerical Pain Rating Scale, with the lowest value indicating “no pain” and the highest value representing “pain as bad as it could be.”

- Researchers compared pain intensity between these patient BMI groups: Normal weight vs overweight plus obesity, normal weight vs overweight, normal weight vs obesity, and overweight vs obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- Compared with people with normal weight, people with excess weight (overweight or obesity; standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.15; P = .0052) or with obesity (SMD, −0.22; P = .0008) reported higher pain intensities, with a small effect size.

- The comparison of self-report pain in people who had normal weight and overweight did not show any statistically significant difference.

IN PRACTICE:

“These findings encourage the treatment of obesity and the control of body mass index (weight loss) as key complementary interventions for pain management,” wrote the authors.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Miguel M. Garcia, Department of Basic Health Sciences, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Unidad Asociada de I+D+i al Instituto de Química Médica CSIC-URJC, Alcorcón, Spain. It was published online in Frontiers in Endocrinology.

LIMITATIONS:

The analysis did not include individuals who were underweight, potentially overlooking the associations between physical pain and malnutrition. BMI may misclassify individuals with high muscularity, as it doesn’t accurately reflect adiposity and cannot distinguish between two people with similar BMIs and different body compositions. Furthermore, the study did not consider gender-based differences while evaluating pain outcomes.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no specific funding from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers Seek to Block Use of FDA-Approved OUD-Risk Test

A group of researchers urged US regulators to revoke the approval of a test marketed for predicting risk for opioid addiction and said government health plans should not pay for the product.

The focus of the request is AdvertD (SOLVD Health), which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in December as the first test to use DNA to evaluate if people have an elevated risk for opioid use disorder (OUD). A sample obtained through a cheek swab is meant to help guide decisions about opioid prescriptions for patients not previously treated with these drugs, such as someone undergoing a planned surgery, the FDA said.

But Michael T. Abrams, MPH, PhD, senior health researcher for Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, and 30 other physicians and researchers sent an April 4 letter to the Food and Drug Administration calling on the government to reconsider.

Dr. Abrams and fellow signers of the letters, including longtime opioid watchdog Andrew Kolodny, MD, of Brandeis University, said the algorithm used in creating AvertD “fell into known pitfalls of genetic prediction that give the appearance of predicting genetic risk, without being a true measure of genetic risk.”

The letter adds that false-positive test results may result in harmful consequences, with clinicians refraining from prescribing needed opioids, a problem that may be magnified in minority populations.

Among the signers of the letter is Alexander Hatoum, PhD, of Washington University, who conducted an independent evaluation of AdvertD, which he and his colleagues published in 2021 in Drug and Alcohol Dependency.

Dr. Hatoum said many patients may not fully understand the limit of genetic testing in predicting conditions like risk for OUD, where many factors are at play. The availability of a test may lend the impression that a single DNA trait makes the difference, as happens with conditions like Huntington’s disease and cystic fibrosis, he said.

“But it’s just not reality for most diseases,” Dr. Hatoum told this news organization.

The FDA declined to comment on the letter and said its approval of the test was “another step forward” in efforts to prevent new cases of OUD.

In 2021, a little more than three quarters of people who died by overdose in the United States involved opioids, or more than 80,000 people, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This figure includes prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl.

While deaths from overdoses with prescription opioids peaked in 2017 at 17,029 people, that figure has decreased steadily. Meanwhile, synthetic opioids other than methadone — primarily fentanyl — were the main driver of drug overdose deaths with a nearly 7.5-fold increase from 2015 to 2021.

The FDA agency said it had “a reasonable assurance of AvertD’s safety and effectiveness, taking into consideration available alternatives, patients’ perspectives, the public health need and the ability to address uncertainty through the collection of post-market data.”

Slow Rollout

In a separate letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dr. Abrams, Dr. Kolodny, Dr. Hatoum, and the other signers repeated their arguments against the use of AdvertD and asked that the government not use federal funds to pay for the test.

SOLVD is not yet selling AdvertD in the United States, and it has not yet set a price for the product. The Carlsbad, California-based company told this news organization in an email exchange that it is working with both Medicare and private insurers on questions of future coverage.

AvertD correctly identified an elevated risk for OUD in about 82.8% of cases, equating to a false-negative rate of 18.2% of patients, the FDA said in its summary of on the data supporting the application. This measure is known as sensitivity, meaning it shows how often an individual has the condition addressed in the test.

Meanwhile, the false positive rate was 20.8%, the FDA said.

SOLVD published similar study results in 2021.

The company failed to impress the FDA’s Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Panel, which in October 2022, said the probable risks of the test likely outweighed its benefits.

Then, in November 2022, the FDA and National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a public workshop meeting to consider the challenges and possibilities in developing tools to predict the risk of developing OUD. At that meeting, Keri Donaldson, MD, MSCE, the chief executive officer of SOLVD, said the company planned to conduct a controlled rollout of AdvertD on FDA approval.

Dr. Donaldson said a “defined set” of clinicians would first access the test, allowing the company to understand how results would be used in clinical practice.

“Once a test gets into practice, you have to be very purposeful and thoughtful about how it’s used,” he said.

The FDA approved the test in December 2023, saying it had worked with the company on modifications to its test. It also said that the advisory committee’s feedback helped in the evaluation and ultimate approval of AdvertD.

Even beyond the debate about the predictive ability of genetic tests for OUD are larger questions that physicians need time to ask patients in assessing their potential risk for addiction when prescribing narcotic painkillers, said Maya Hambright, MD, a physician in New York’s Hudson Valley who has been working mainly in addiction in response to the overdose crisis.

Genetics are just one of many factors at play in causing people to become addicted to opioids, Dr. Hambright said.

Physicians must also consider the lasting effects of emotional and physical trauma experienced at any age, but particularly in childhood, as well as what kind of social support a patient has in facing the illness or injury that may require opioids for pain, she said.

“There is a time and place for narcotic medications to be prescribed appropriately, which means we have to do our due diligence,” Dr. Hambright told this news organization. “Regardless of the strides we make in research and development, we still must connect and communicate safely and effectively and compassionately with our patients.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A group of researchers urged US regulators to revoke the approval of a test marketed for predicting risk for opioid addiction and said government health plans should not pay for the product.

The focus of the request is AdvertD (SOLVD Health), which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in December as the first test to use DNA to evaluate if people have an elevated risk for opioid use disorder (OUD). A sample obtained through a cheek swab is meant to help guide decisions about opioid prescriptions for patients not previously treated with these drugs, such as someone undergoing a planned surgery, the FDA said.

But Michael T. Abrams, MPH, PhD, senior health researcher for Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, and 30 other physicians and researchers sent an April 4 letter to the Food and Drug Administration calling on the government to reconsider.

Dr. Abrams and fellow signers of the letters, including longtime opioid watchdog Andrew Kolodny, MD, of Brandeis University, said the algorithm used in creating AvertD “fell into known pitfalls of genetic prediction that give the appearance of predicting genetic risk, without being a true measure of genetic risk.”

The letter adds that false-positive test results may result in harmful consequences, with clinicians refraining from prescribing needed opioids, a problem that may be magnified in minority populations.

Among the signers of the letter is Alexander Hatoum, PhD, of Washington University, who conducted an independent evaluation of AdvertD, which he and his colleagues published in 2021 in Drug and Alcohol Dependency.

Dr. Hatoum said many patients may not fully understand the limit of genetic testing in predicting conditions like risk for OUD, where many factors are at play. The availability of a test may lend the impression that a single DNA trait makes the difference, as happens with conditions like Huntington’s disease and cystic fibrosis, he said.

“But it’s just not reality for most diseases,” Dr. Hatoum told this news organization.

The FDA declined to comment on the letter and said its approval of the test was “another step forward” in efforts to prevent new cases of OUD.

In 2021, a little more than three quarters of people who died by overdose in the United States involved opioids, or more than 80,000 people, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This figure includes prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl.

While deaths from overdoses with prescription opioids peaked in 2017 at 17,029 people, that figure has decreased steadily. Meanwhile, synthetic opioids other than methadone — primarily fentanyl — were the main driver of drug overdose deaths with a nearly 7.5-fold increase from 2015 to 2021.

The FDA agency said it had “a reasonable assurance of AvertD’s safety and effectiveness, taking into consideration available alternatives, patients’ perspectives, the public health need and the ability to address uncertainty through the collection of post-market data.”

Slow Rollout

In a separate letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dr. Abrams, Dr. Kolodny, Dr. Hatoum, and the other signers repeated their arguments against the use of AdvertD and asked that the government not use federal funds to pay for the test.

SOLVD is not yet selling AdvertD in the United States, and it has not yet set a price for the product. The Carlsbad, California-based company told this news organization in an email exchange that it is working with both Medicare and private insurers on questions of future coverage.

AvertD correctly identified an elevated risk for OUD in about 82.8% of cases, equating to a false-negative rate of 18.2% of patients, the FDA said in its summary of on the data supporting the application. This measure is known as sensitivity, meaning it shows how often an individual has the condition addressed in the test.

Meanwhile, the false positive rate was 20.8%, the FDA said.

SOLVD published similar study results in 2021.

The company failed to impress the FDA’s Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Panel, which in October 2022, said the probable risks of the test likely outweighed its benefits.

Then, in November 2022, the FDA and National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a public workshop meeting to consider the challenges and possibilities in developing tools to predict the risk of developing OUD. At that meeting, Keri Donaldson, MD, MSCE, the chief executive officer of SOLVD, said the company planned to conduct a controlled rollout of AdvertD on FDA approval.

Dr. Donaldson said a “defined set” of clinicians would first access the test, allowing the company to understand how results would be used in clinical practice.

“Once a test gets into practice, you have to be very purposeful and thoughtful about how it’s used,” he said.

The FDA approved the test in December 2023, saying it had worked with the company on modifications to its test. It also said that the advisory committee’s feedback helped in the evaluation and ultimate approval of AdvertD.

Even beyond the debate about the predictive ability of genetic tests for OUD are larger questions that physicians need time to ask patients in assessing their potential risk for addiction when prescribing narcotic painkillers, said Maya Hambright, MD, a physician in New York’s Hudson Valley who has been working mainly in addiction in response to the overdose crisis.

Genetics are just one of many factors at play in causing people to become addicted to opioids, Dr. Hambright said.

Physicians must also consider the lasting effects of emotional and physical trauma experienced at any age, but particularly in childhood, as well as what kind of social support a patient has in facing the illness or injury that may require opioids for pain, she said.

“There is a time and place for narcotic medications to be prescribed appropriately, which means we have to do our due diligence,” Dr. Hambright told this news organization. “Regardless of the strides we make in research and development, we still must connect and communicate safely and effectively and compassionately with our patients.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A group of researchers urged US regulators to revoke the approval of a test marketed for predicting risk for opioid addiction and said government health plans should not pay for the product.

The focus of the request is AdvertD (SOLVD Health), which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in December as the first test to use DNA to evaluate if people have an elevated risk for opioid use disorder (OUD). A sample obtained through a cheek swab is meant to help guide decisions about opioid prescriptions for patients not previously treated with these drugs, such as someone undergoing a planned surgery, the FDA said.

But Michael T. Abrams, MPH, PhD, senior health researcher for Public Citizen’s Health Research Group, and 30 other physicians and researchers sent an April 4 letter to the Food and Drug Administration calling on the government to reconsider.

Dr. Abrams and fellow signers of the letters, including longtime opioid watchdog Andrew Kolodny, MD, of Brandeis University, said the algorithm used in creating AvertD “fell into known pitfalls of genetic prediction that give the appearance of predicting genetic risk, without being a true measure of genetic risk.”

The letter adds that false-positive test results may result in harmful consequences, with clinicians refraining from prescribing needed opioids, a problem that may be magnified in minority populations.

Among the signers of the letter is Alexander Hatoum, PhD, of Washington University, who conducted an independent evaluation of AdvertD, which he and his colleagues published in 2021 in Drug and Alcohol Dependency.

Dr. Hatoum said many patients may not fully understand the limit of genetic testing in predicting conditions like risk for OUD, where many factors are at play. The availability of a test may lend the impression that a single DNA trait makes the difference, as happens with conditions like Huntington’s disease and cystic fibrosis, he said.

“But it’s just not reality for most diseases,” Dr. Hatoum told this news organization.

The FDA declined to comment on the letter and said its approval of the test was “another step forward” in efforts to prevent new cases of OUD.

In 2021, a little more than three quarters of people who died by overdose in the United States involved opioids, or more than 80,000 people, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This figure includes prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl.

While deaths from overdoses with prescription opioids peaked in 2017 at 17,029 people, that figure has decreased steadily. Meanwhile, synthetic opioids other than methadone — primarily fentanyl — were the main driver of drug overdose deaths with a nearly 7.5-fold increase from 2015 to 2021.

The FDA agency said it had “a reasonable assurance of AvertD’s safety and effectiveness, taking into consideration available alternatives, patients’ perspectives, the public health need and the ability to address uncertainty through the collection of post-market data.”

Slow Rollout

In a separate letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dr. Abrams, Dr. Kolodny, Dr. Hatoum, and the other signers repeated their arguments against the use of AdvertD and asked that the government not use federal funds to pay for the test.

SOLVD is not yet selling AdvertD in the United States, and it has not yet set a price for the product. The Carlsbad, California-based company told this news organization in an email exchange that it is working with both Medicare and private insurers on questions of future coverage.

AvertD correctly identified an elevated risk for OUD in about 82.8% of cases, equating to a false-negative rate of 18.2% of patients, the FDA said in its summary of on the data supporting the application. This measure is known as sensitivity, meaning it shows how often an individual has the condition addressed in the test.

Meanwhile, the false positive rate was 20.8%, the FDA said.

SOLVD published similar study results in 2021.

The company failed to impress the FDA’s Clinical Chemistry and Clinical Toxicology Devices Panel, which in October 2022, said the probable risks of the test likely outweighed its benefits.

Then, in November 2022, the FDA and National Institutes of Health (NIH) held a public workshop meeting to consider the challenges and possibilities in developing tools to predict the risk of developing OUD. At that meeting, Keri Donaldson, MD, MSCE, the chief executive officer of SOLVD, said the company planned to conduct a controlled rollout of AdvertD on FDA approval.

Dr. Donaldson said a “defined set” of clinicians would first access the test, allowing the company to understand how results would be used in clinical practice.

“Once a test gets into practice, you have to be very purposeful and thoughtful about how it’s used,” he said.

The FDA approved the test in December 2023, saying it had worked with the company on modifications to its test. It also said that the advisory committee’s feedback helped in the evaluation and ultimate approval of AdvertD.

Even beyond the debate about the predictive ability of genetic tests for OUD are larger questions that physicians need time to ask patients in assessing their potential risk for addiction when prescribing narcotic painkillers, said Maya Hambright, MD, a physician in New York’s Hudson Valley who has been working mainly in addiction in response to the overdose crisis.

Genetics are just one of many factors at play in causing people to become addicted to opioids, Dr. Hambright said.

Physicians must also consider the lasting effects of emotional and physical trauma experienced at any age, but particularly in childhood, as well as what kind of social support a patient has in facing the illness or injury that may require opioids for pain, she said.

“There is a time and place for narcotic medications to be prescribed appropriately, which means we have to do our due diligence,” Dr. Hambright told this news organization. “Regardless of the strides we make in research and development, we still must connect and communicate safely and effectively and compassionately with our patients.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA Expands Enhertu Indication to HER2-Positive Solid Tumors

The agent had already been approved for several cancer types, including certain patients with unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer as well as adults with locally advanced or metastatic HER2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma who had received a prior trastuzumab-based regimen.

The current accelerated approval is the first tumor-agnostic approval of a HER2-directed therapy and antibody drug conjugate.

“Until approval of trastuzumab deruxtecan, patients with metastatic HER2-positive tumors have had limited treatment options,” Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of investigational cancer therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an AstraZeneca press statement. “Based on the clinically meaningful response rates across clinical trials, this tumor-agnostic approval means that patients may now be treated with a HER2-directed medicine.”

Approval was based on findings in 192 patients enrolled in either the DESTINY-PanTumor02 trial, the DESTINY-Lung01 trial, or the DESTINY-CRC02 trial. Patients in the multicenter trials underwent treatment until disease progression, death, withdrawal of consent or unacceptable toxicity.

Confirmed objective response rates were 51.4%, 52.9%, and 46.9% in the three studies, respectively. Median duration of response was 19.4, 6.9, and 5.5 months, respectively.

The most common adverse reactions occurring in at least 20% of patients included decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin, lymphocyte count, and neutrophil count, as well as nausea, fatigue, platelet count, vomiting, alopecia, diarrhea, stomatitis, and upper respiratory tract infection.

Full prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risk for interstitial lung disease and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dosage is 5.4 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion one every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The agent had already been approved for several cancer types, including certain patients with unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer as well as adults with locally advanced or metastatic HER2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma who had received a prior trastuzumab-based regimen.

The current accelerated approval is the first tumor-agnostic approval of a HER2-directed therapy and antibody drug conjugate.

“Until approval of trastuzumab deruxtecan, patients with metastatic HER2-positive tumors have had limited treatment options,” Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of investigational cancer therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an AstraZeneca press statement. “Based on the clinically meaningful response rates across clinical trials, this tumor-agnostic approval means that patients may now be treated with a HER2-directed medicine.”

Approval was based on findings in 192 patients enrolled in either the DESTINY-PanTumor02 trial, the DESTINY-Lung01 trial, or the DESTINY-CRC02 trial. Patients in the multicenter trials underwent treatment until disease progression, death, withdrawal of consent or unacceptable toxicity.

Confirmed objective response rates were 51.4%, 52.9%, and 46.9% in the three studies, respectively. Median duration of response was 19.4, 6.9, and 5.5 months, respectively.

The most common adverse reactions occurring in at least 20% of patients included decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin, lymphocyte count, and neutrophil count, as well as nausea, fatigue, platelet count, vomiting, alopecia, diarrhea, stomatitis, and upper respiratory tract infection.

Full prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risk for interstitial lung disease and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dosage is 5.4 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion one every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The agent had already been approved for several cancer types, including certain patients with unresectable or metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer as well as adults with locally advanced or metastatic HER2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma who had received a prior trastuzumab-based regimen.

The current accelerated approval is the first tumor-agnostic approval of a HER2-directed therapy and antibody drug conjugate.

“Until approval of trastuzumab deruxtecan, patients with metastatic HER2-positive tumors have had limited treatment options,” Funda Meric-Bernstam, MD, chair of investigational cancer therapeutics at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in an AstraZeneca press statement. “Based on the clinically meaningful response rates across clinical trials, this tumor-agnostic approval means that patients may now be treated with a HER2-directed medicine.”

Approval was based on findings in 192 patients enrolled in either the DESTINY-PanTumor02 trial, the DESTINY-Lung01 trial, or the DESTINY-CRC02 trial. Patients in the multicenter trials underwent treatment until disease progression, death, withdrawal of consent or unacceptable toxicity.

Confirmed objective response rates were 51.4%, 52.9%, and 46.9% in the three studies, respectively. Median duration of response was 19.4, 6.9, and 5.5 months, respectively.

The most common adverse reactions occurring in at least 20% of patients included decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin, lymphocyte count, and neutrophil count, as well as nausea, fatigue, platelet count, vomiting, alopecia, diarrhea, stomatitis, and upper respiratory tract infection.

Full prescribing information includes a boxed warning about the risk for interstitial lung disease and embryo-fetal toxicity.

The recommended dosage is 5.4 mg/kg given as an intravenous infusion one every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

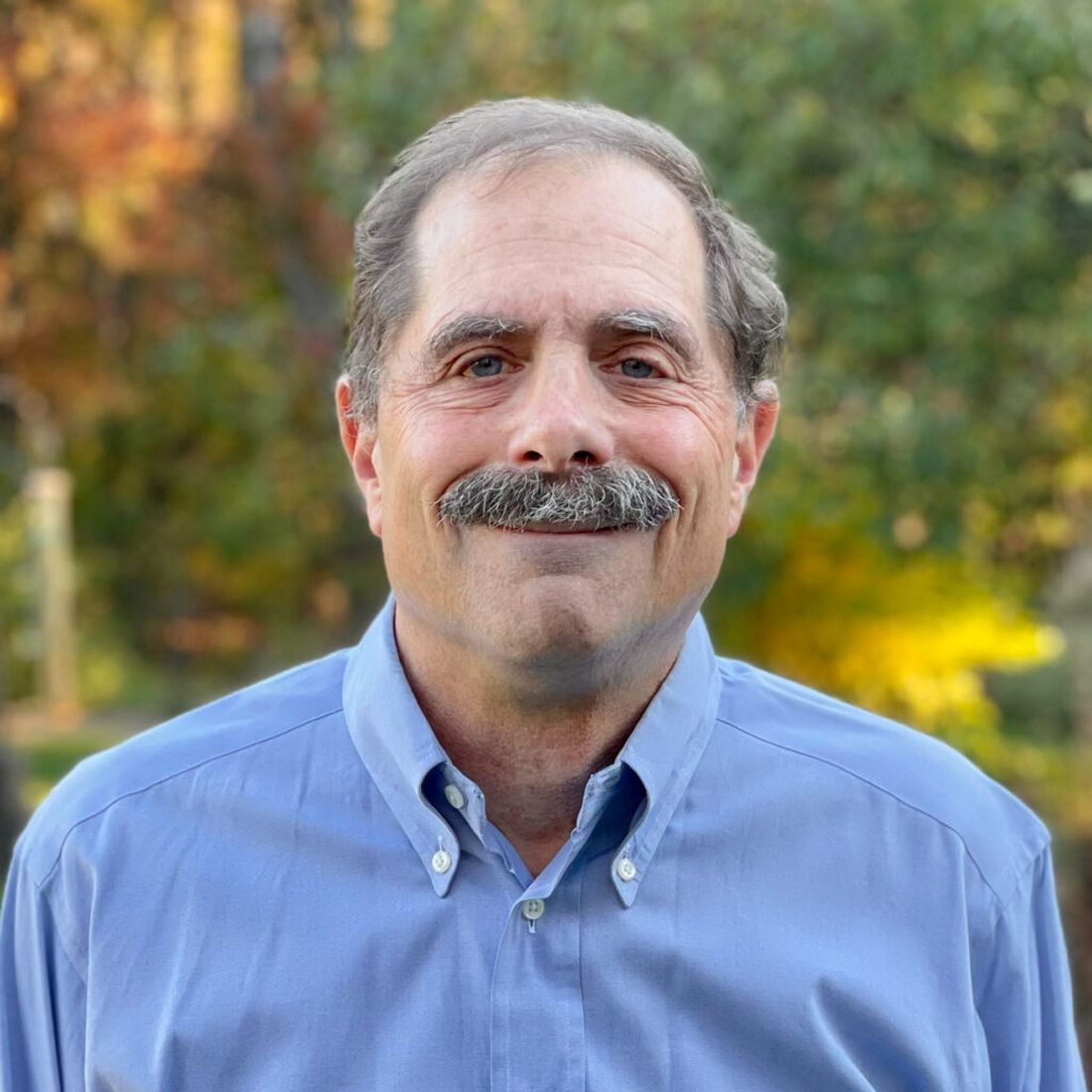

New Insight Into ‘Demon’ Facial Visual Perception Disorder

Images generated by photographic computer software are the first to depict accurate images of facial distortions experienced by patients with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO), a rare visual disorder that is often mistaken for mental illness.

PMO is a rare, often misdiagnosed, visual disorder in which human faces appear distorted in shape, texture, position, or color. Most patients with PMO see these distorted facial features all the time, whether they are looking at a face in person, on a screen, or paper.

Unlike most cases of PMO, the patient reported seeing the distortions only when encountering someone in person but not on a screen or on paper.

This allowed researchers to use editing software to create an image on a computer screen that matched the patient’s distorted view.

“This new information should help healthcare professionals grasp the intensity of facial distortions experienced by people with PMO,” study investigator Brad Duchaine, PhD, professor, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, told this news organization.

“A substantial number of people we have worked with have been misdiagnosed, often with schizophrenia or some sort of psychotic episode, and some have been put on antipsychotics despite the fact they’ve just had some little tweak in their visual system,” he added.

The report was published online on March 23 in The Lancet.

Prevalence Underestimated?

Although fewer than 100 cases of PMO have been reported in the literature, Dr. Duchaine said this is likely an underestimate. Based on a response to a website his team created to recruit affected patients, he said he believes “there are far more cases out there that we realize.”

PMO might be caused by a neurologic event that leads to a lesion in the right temporal lobe, near areas of facial processing, but in many cases, the cause is unclear.

PMO can occur in the context of head trauma, as well as cerebral infarction, epilepsy, migraine, and hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder, researchers noted. The condition can also manifest without detectable structural brain changes.

“We’re hearing from a lot of people through our website who haven’t had, or aren’t aware of having had, a neurologic event that coincided with the onset of face distortions,” Dr. Duchaine noted.

The patient in this study had a significant head injury at age 43 that led to hospitalization. He was exposed to high levels of carbon monoxide about 4 months before his symptoms began, but it’s not clear if the PMO and the incident are related.

He was not prescribed any medications and reported no history of illicit substance use.

The patient also had a history of bipolar affective disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. His visions of distorted faces were not accompanied by delusional beliefs about the people he encountered, the investigators reported.

Neuropsychological tests were normal, and there were no deficits of visual acuity or color vision. Computer-based face perception tests indicated mild impairment in recognition of facial identity but normal recognition of facial expression.

The patient did not typically see distortions when looking at objects, such as a coffee mug or computer. However, said Dr. Duchaine, “if you get enough text together, the text will start to swirl for him.”

Eye-Opening Findings

The patient described the visual facial distortions as “severely stretched features, with deep grooves on the forehead, cheeks, and chin.” Even though these faces were distorted, he was able to recognize the people he saw.

Because the patient reported no distortion when viewing facial images on a screen, researchers asked him to compare what he saw when he looked at the face of a person in the room to a photograph of the same person on a computer screen.

The patient alternated between observing the in-person face, which he perceived as distorted, and the photo on the screen, which he perceived as normal.

Researchers used real-time feedback from the patient and photo-editing software to manipulate the photo on the screen until the photo and the patient’s visual perception of the person in the room matched.

“This is the first time we have actually been able to have a visualization where we are really confident that that’s what someone with PMO is experiencing,” said Dr. Duchaine. “If he were a typical PMO case, he would look at the face in real life and look at the face on the screen and the face on the screen would be distorting as well.”

The researchers discovered that the patient’s distortions are influenced by color; if he looks at faces through a red filter, the distortions are greatly intensified, but if he looks at them through a green filter, the distortions are greatly reduced. He now wears green-filtered glasses in certain situations.

Dr. Duchaine hopes this case will open the eyes of clinicians. “These sorts of visual distortions that your patient is telling you about are probably real, and they’re not a sign of broader mental illness; it’s a problem limited to the visual system,” he said.

The research was funded by the Hitchcock Foundation. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Images generated by photographic computer software are the first to depict accurate images of facial distortions experienced by patients with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO), a rare visual disorder that is often mistaken for mental illness.

PMO is a rare, often misdiagnosed, visual disorder in which human faces appear distorted in shape, texture, position, or color. Most patients with PMO see these distorted facial features all the time, whether they are looking at a face in person, on a screen, or paper.

Unlike most cases of PMO, the patient reported seeing the distortions only when encountering someone in person but not on a screen or on paper.

This allowed researchers to use editing software to create an image on a computer screen that matched the patient’s distorted view.

“This new information should help healthcare professionals grasp the intensity of facial distortions experienced by people with PMO,” study investigator Brad Duchaine, PhD, professor, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, told this news organization.

“A substantial number of people we have worked with have been misdiagnosed, often with schizophrenia or some sort of psychotic episode, and some have been put on antipsychotics despite the fact they’ve just had some little tweak in their visual system,” he added.

The report was published online on March 23 in The Lancet.

Prevalence Underestimated?

Although fewer than 100 cases of PMO have been reported in the literature, Dr. Duchaine said this is likely an underestimate. Based on a response to a website his team created to recruit affected patients, he said he believes “there are far more cases out there that we realize.”

PMO might be caused by a neurologic event that leads to a lesion in the right temporal lobe, near areas of facial processing, but in many cases, the cause is unclear.

PMO can occur in the context of head trauma, as well as cerebral infarction, epilepsy, migraine, and hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder, researchers noted. The condition can also manifest without detectable structural brain changes.

“We’re hearing from a lot of people through our website who haven’t had, or aren’t aware of having had, a neurologic event that coincided with the onset of face distortions,” Dr. Duchaine noted.

The patient in this study had a significant head injury at age 43 that led to hospitalization. He was exposed to high levels of carbon monoxide about 4 months before his symptoms began, but it’s not clear if the PMO and the incident are related.

He was not prescribed any medications and reported no history of illicit substance use.

The patient also had a history of bipolar affective disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. His visions of distorted faces were not accompanied by delusional beliefs about the people he encountered, the investigators reported.

Neuropsychological tests were normal, and there were no deficits of visual acuity or color vision. Computer-based face perception tests indicated mild impairment in recognition of facial identity but normal recognition of facial expression.

The patient did not typically see distortions when looking at objects, such as a coffee mug or computer. However, said Dr. Duchaine, “if you get enough text together, the text will start to swirl for him.”

Eye-Opening Findings

The patient described the visual facial distortions as “severely stretched features, with deep grooves on the forehead, cheeks, and chin.” Even though these faces were distorted, he was able to recognize the people he saw.

Because the patient reported no distortion when viewing facial images on a screen, researchers asked him to compare what he saw when he looked at the face of a person in the room to a photograph of the same person on a computer screen.

The patient alternated between observing the in-person face, which he perceived as distorted, and the photo on the screen, which he perceived as normal.

Researchers used real-time feedback from the patient and photo-editing software to manipulate the photo on the screen until the photo and the patient’s visual perception of the person in the room matched.

“This is the first time we have actually been able to have a visualization where we are really confident that that’s what someone with PMO is experiencing,” said Dr. Duchaine. “If he were a typical PMO case, he would look at the face in real life and look at the face on the screen and the face on the screen would be distorting as well.”

The researchers discovered that the patient’s distortions are influenced by color; if he looks at faces through a red filter, the distortions are greatly intensified, but if he looks at them through a green filter, the distortions are greatly reduced. He now wears green-filtered glasses in certain situations.

Dr. Duchaine hopes this case will open the eyes of clinicians. “These sorts of visual distortions that your patient is telling you about are probably real, and they’re not a sign of broader mental illness; it’s a problem limited to the visual system,” he said.

The research was funded by the Hitchcock Foundation. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Images generated by photographic computer software are the first to depict accurate images of facial distortions experienced by patients with prosopometamorphopsia (PMO), a rare visual disorder that is often mistaken for mental illness.

PMO is a rare, often misdiagnosed, visual disorder in which human faces appear distorted in shape, texture, position, or color. Most patients with PMO see these distorted facial features all the time, whether they are looking at a face in person, on a screen, or paper.

Unlike most cases of PMO, the patient reported seeing the distortions only when encountering someone in person but not on a screen or on paper.

This allowed researchers to use editing software to create an image on a computer screen that matched the patient’s distorted view.

“This new information should help healthcare professionals grasp the intensity of facial distortions experienced by people with PMO,” study investigator Brad Duchaine, PhD, professor, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, told this news organization.

“A substantial number of people we have worked with have been misdiagnosed, often with schizophrenia or some sort of psychotic episode, and some have been put on antipsychotics despite the fact they’ve just had some little tweak in their visual system,” he added.

The report was published online on March 23 in The Lancet.

Prevalence Underestimated?

Although fewer than 100 cases of PMO have been reported in the literature, Dr. Duchaine said this is likely an underestimate. Based on a response to a website his team created to recruit affected patients, he said he believes “there are far more cases out there that we realize.”

PMO might be caused by a neurologic event that leads to a lesion in the right temporal lobe, near areas of facial processing, but in many cases, the cause is unclear.

PMO can occur in the context of head trauma, as well as cerebral infarction, epilepsy, migraine, and hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder, researchers noted. The condition can also manifest without detectable structural brain changes.

“We’re hearing from a lot of people through our website who haven’t had, or aren’t aware of having had, a neurologic event that coincided with the onset of face distortions,” Dr. Duchaine noted.

The patient in this study had a significant head injury at age 43 that led to hospitalization. He was exposed to high levels of carbon monoxide about 4 months before his symptoms began, but it’s not clear if the PMO and the incident are related.

He was not prescribed any medications and reported no history of illicit substance use.

The patient also had a history of bipolar affective disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. His visions of distorted faces were not accompanied by delusional beliefs about the people he encountered, the investigators reported.

Neuropsychological tests were normal, and there were no deficits of visual acuity or color vision. Computer-based face perception tests indicated mild impairment in recognition of facial identity but normal recognition of facial expression.

The patient did not typically see distortions when looking at objects, such as a coffee mug or computer. However, said Dr. Duchaine, “if you get enough text together, the text will start to swirl for him.”

Eye-Opening Findings

The patient described the visual facial distortions as “severely stretched features, with deep grooves on the forehead, cheeks, and chin.” Even though these faces were distorted, he was able to recognize the people he saw.

Because the patient reported no distortion when viewing facial images on a screen, researchers asked him to compare what he saw when he looked at the face of a person in the room to a photograph of the same person on a computer screen.

The patient alternated between observing the in-person face, which he perceived as distorted, and the photo on the screen, which he perceived as normal.