User login

AGA Gives Guidance on Subepithelial Lesions

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

The new guidance document, authored by Lionel S. D’Souza, MD, of Stony Brook University Hospital, Stony Brook, New York, and colleagues, offers a framework for deciding between various EFTR techniques based on lesion histology, size, and location.

“EFTR has emerged as a novel treatment option for select SELs,” the update panelists wrote in Gastroenterology. “In this commentary, we reviewed the different techniques and uses of EFTR for the management of SELs.”

They noted that all patients with SELs should first undergo multidisciplinary evaluation in accordance with a separate AGA guidance document on SELs.

The present update focuses specifically on EFTR, first by distinguishing between exposed and nonexposed techniques. While the former involves resection of the mucosa and all other layers of the wall, the latter relies upon a ‘close first, then cut’ method to prevent perforation, or preservation of an overlying flap of mucosa.

The new guidance calls for a nonexposed technique unless the exposed approach is necessary.

“In our opinion, the exposed EFTR technique should be considered for lesions in which other methods (i.e., endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal dissection, and nonexposed EFTR) cannot reliably and completely excise SELs due to larger size or difficult location of the lesion,” the update panelists wrote. “The exposed EFTR technique may be best suited for gastric lesions and as an alternative to other endoscopic approaches for SELs in the rectum. The exposed technique should be avoided in the esophagus and duodenum, as the clinical consequences of a leak can be devastating and endoscopic closure is notoriously challenging.”

Dr. D’Souza and colleagues went on to discuss various nonexposed techniques, including submucosal tunneling and endoscopic resection and peroral endoscopic tunnel resection (STER/POET), device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, and full-thickness resection with an over-the-scope clip with integrated snare (FTRD).

They highlighted how STER/POET encourages traction on the lesion and scope stability while limiting extravasation of luminal contents, and closure tends to be easier than with exposed EFTR. This approach should be reserved for tumors smaller than approximately 3-4 cm, however, with the update noting that lesions larger than 2 cm may present increased risk of incomplete resection. Similarly, device-assisted endoscopic full-thickness resection, which involves pulling or suctioning the lesion into the device, is also limited by lesion size, although fewer data are available to guide size thresholds.

FTRD, which involves “a 23-mm deep cap with a specially designed over-the-scope clip and integrated cautery snare,” also lacks a broad evidence base.

“Although there has been reasonable clinical success reported in most case series, several factors should be considered with the use of the FTRD for SELs,” the update cautions.

Specifically, a recent Dutch and German registry study of FTRD had an adverse event rate of 11.3%, with an approximate 1% perforation rate. More than half of the perforations were due to technical or procedural issues.

“This adverse event rate may improve as individual experience with the device is gained; however, data on this are lacking,” the panelists wrote, also noting that lesions 1.5 cm or larger may carry a higher risk of incomplete resection.

Ultimately, the clinical practice update calls for a personalized approach to EFTR decision-making that considers factors extending beyond the lesion.

“The ‘ideal’ technique will depend on various patient and lesion characteristics, as well as the endoscopist’s preference and available expertise,” Dr. D’Souza and colleagues concluded. “Further research into the efficacy of these resection techniques and the long-term outcomes in patients after endoscopic resection of SELs will be essential in standardizing appropriate resection algorithms.”

This clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by AGA Institute. The investigators disclosed relationships with Olympus, Fujifilm, Apollo Endosurgery, and others.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Telephone Best for Switching Patients to New Colonoscopy Intervals

In an article published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, a group led by Jeffrey K. Lee, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco, reported the following 60-day response rates for the three contact methods in potentially transitioning more than 600 post-polypectomy patients to the new interval:

- Telephone: 64.5%

- Secure messaging: 51.7%

- Mailed letter: 31.3%

Compared with letter outreach, overall rate differences were significant for telephone (18.1%) and secure message outreach (13.1%).

Such interventions are widely used, the authors noted , but have not been compared for efficacy terms of communicating updated colonoscopy intervals.

The trial’s aim was to inform low-risk patients of the recommended interval update from 5 years — used since the 1990s — to 7-10 years. Given a choice, more patients opted to transition to the 10-year surveillance interval in the telephone (37%) and secure messaging arms (32.%) compared with mailed-letter arm (18.9%).

In addition to telephone and secure messaging outreach, factors positively associated with adoption of the 10-year interval were a positive fecal immunochemical test–based index colonoscopy and increasing age. Patients with these characteristics may be biased toward avoiding colonoscopy if not medically necessary, the authors conjectured.

Inversely associated factors included Asian or Pacific Islander race (odds ratio .58), Hispanic ethnicity (OR .40), and a higher Charlson comorbidity score of 2 vs 0 (OR .43).

Possible explanations for the race and ethnicity associations include gaps in culturally component care, lack of engagement with the English-based outreach approaches, and medical mistrust, the authors said.

“In this study, we gave all our patients an option to either extend their surveillance interval to current guideline recommendations or continue with their old interval, and some chose to do that,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Patients really appreciated having a choice and to be informed about the latest guideline changes.”

“A critical challenge to health systems is how to effectively de-implement outdated surveillance recommendations for low-risk patients who have a 5-year follow-up interval and potentially transition them to the recommended 7- to 10-year interval,” Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

More than 5 million surveillance colonoscopies are performed annually in US patients with a history of adenomas, the main precursor lesion for colorectal cancer, the authors noted.

With the recent guidelines issued in 2020 by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer lengthening the follow-up interval to 7-10 years , physicians are being advised to reevaluate low-risk patients previously scheduled with 5-year surveillance and provide an updated recommendation for follow-up.

Study Details

The three-arm pragmatic randomized trial was conducted in low-risk patients 54-70 years of age with one or two small (< 10 mm) tubular adenomas at baseline colonoscopy. Participants due for 5-year surveillance in 2022 were randomly assigned to one of three outreach arms: telephone (n = 200], secure messaging (n = 203), and mailed letter (n = 201). Stratified by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, participants could change their assigned interval to 10 years or continue with their previously scheduled 5-year interval.

As to economic considerations, the authors said that telephone may be the costliest form of outreach in terms of staffing resources. “We don’t know because we did not conduct a formal cost-effectiveness analysis,” Dr. Lee said. “However, we do know phone outreach requires a lot of personnel effort, which is why we also explored the less costly option of secure messaging/email.”

But based on the findings, telephone outreach would be a reasonable approach to update patients on post-polypectomy surveillance guideline changes if secure messaging or text messaging isn’t available, he added.

Downsides to Retroactive Changes?

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Nabil M. Mansour, MD, an assistant professor and director of the McNair General GI Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that unlike Kaiser Permanente, his center decided against an overall effort to switch patients colonoscopied before the release of the new guidelines over to the new interval.

“Several of our physicians may have chosen to recommend a 5-year interval specifically for a variety of reasons and we felt going back, and making a blanket change to everyone’s interval retrospectively might create confusion and frustration and might actually delay the colonoscopies of some patients for which their doctors had a very good, legitimate reason to recommend a 5-year interval,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Mansour added that no difficulties were encountered in getting patients to agree to a 10-year interval. In his view telephone communication or in-person clinic visits are likely the most effective ways but both are more labor-intensive than automated patient portal messages. “I do not think traditional snail mail is effective.” His clinic uses automatic EMR reminders.

Offering another perspective on the study, Aditya Sreenivasan, MD, a gastroenterologist at Northwell Health in New York City, said his center has not reached out to correct the old intervals. “When I see a patient who previously had a colonoscopy with another physician, I always follow the previous recommendation for when the next colonoscopy should be, regardless of whether or not it technically meets guideline recommendations,” he told this news organization. “I do this because I was not there during the procedure and am not aware of any circumstances that would require a shorter interval that may not be apparent from the report.”

While he agrees with the new guidelines, Dr. Sreenivasan is “not sure if retroactively changing intervals is beneficial to patients, as the presence of guidelines may subconsciously influence the behavior of the endoscopist at the time of the procedure. For example, if a patient has a technically challenging colonoscopy and the endoscopist is running late, the endoscopist may drop their guard once they find a polyp and miss 1-2 additional small polyps that they would have spent more time looking for if they knew their next one would be in 10 years instead of 5.”

As for notification method, despite the logistical downside of taking dedicated staff time to make telephone calls, Dr. Sreenivasan said, “I think having a conversation with the patient directly is a much better way to communicate this information as it allows the patient to ask and answer questions. Things like tone of voice can provide reassurance that one cannot get via email.” Looking to the future, the study authors acknowledged that combinations of initial and reminder outreach approaches — for example, a mailed letter followed by secure message or telephone call — could potentially yield higher response rates and/or adoption rates than they observed. And a longer follow-up period with additional reminders may have produced higher yields. Additional studies are needed to optimize outreach approaches and to understand patient barriers to adopting the new guideline recommendations in different healthcare settings.

The study was supported by a Delivery Science grant from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Mansour and Dr. Sreenivasan disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to their comments.

In an article published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, a group led by Jeffrey K. Lee, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco, reported the following 60-day response rates for the three contact methods in potentially transitioning more than 600 post-polypectomy patients to the new interval:

- Telephone: 64.5%

- Secure messaging: 51.7%

- Mailed letter: 31.3%

Compared with letter outreach, overall rate differences were significant for telephone (18.1%) and secure message outreach (13.1%).

Such interventions are widely used, the authors noted , but have not been compared for efficacy terms of communicating updated colonoscopy intervals.

The trial’s aim was to inform low-risk patients of the recommended interval update from 5 years — used since the 1990s — to 7-10 years. Given a choice, more patients opted to transition to the 10-year surveillance interval in the telephone (37%) and secure messaging arms (32.%) compared with mailed-letter arm (18.9%).

In addition to telephone and secure messaging outreach, factors positively associated with adoption of the 10-year interval were a positive fecal immunochemical test–based index colonoscopy and increasing age. Patients with these characteristics may be biased toward avoiding colonoscopy if not medically necessary, the authors conjectured.

Inversely associated factors included Asian or Pacific Islander race (odds ratio .58), Hispanic ethnicity (OR .40), and a higher Charlson comorbidity score of 2 vs 0 (OR .43).

Possible explanations for the race and ethnicity associations include gaps in culturally component care, lack of engagement with the English-based outreach approaches, and medical mistrust, the authors said.

“In this study, we gave all our patients an option to either extend their surveillance interval to current guideline recommendations or continue with their old interval, and some chose to do that,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Patients really appreciated having a choice and to be informed about the latest guideline changes.”

“A critical challenge to health systems is how to effectively de-implement outdated surveillance recommendations for low-risk patients who have a 5-year follow-up interval and potentially transition them to the recommended 7- to 10-year interval,” Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

More than 5 million surveillance colonoscopies are performed annually in US patients with a history of adenomas, the main precursor lesion for colorectal cancer, the authors noted.

With the recent guidelines issued in 2020 by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer lengthening the follow-up interval to 7-10 years , physicians are being advised to reevaluate low-risk patients previously scheduled with 5-year surveillance and provide an updated recommendation for follow-up.

Study Details

The three-arm pragmatic randomized trial was conducted in low-risk patients 54-70 years of age with one or two small (< 10 mm) tubular adenomas at baseline colonoscopy. Participants due for 5-year surveillance in 2022 were randomly assigned to one of three outreach arms: telephone (n = 200], secure messaging (n = 203), and mailed letter (n = 201). Stratified by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, participants could change their assigned interval to 10 years or continue with their previously scheduled 5-year interval.

As to economic considerations, the authors said that telephone may be the costliest form of outreach in terms of staffing resources. “We don’t know because we did not conduct a formal cost-effectiveness analysis,” Dr. Lee said. “However, we do know phone outreach requires a lot of personnel effort, which is why we also explored the less costly option of secure messaging/email.”

But based on the findings, telephone outreach would be a reasonable approach to update patients on post-polypectomy surveillance guideline changes if secure messaging or text messaging isn’t available, he added.

Downsides to Retroactive Changes?

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Nabil M. Mansour, MD, an assistant professor and director of the McNair General GI Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that unlike Kaiser Permanente, his center decided against an overall effort to switch patients colonoscopied before the release of the new guidelines over to the new interval.

“Several of our physicians may have chosen to recommend a 5-year interval specifically for a variety of reasons and we felt going back, and making a blanket change to everyone’s interval retrospectively might create confusion and frustration and might actually delay the colonoscopies of some patients for which their doctors had a very good, legitimate reason to recommend a 5-year interval,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Mansour added that no difficulties were encountered in getting patients to agree to a 10-year interval. In his view telephone communication or in-person clinic visits are likely the most effective ways but both are more labor-intensive than automated patient portal messages. “I do not think traditional snail mail is effective.” His clinic uses automatic EMR reminders.

Offering another perspective on the study, Aditya Sreenivasan, MD, a gastroenterologist at Northwell Health in New York City, said his center has not reached out to correct the old intervals. “When I see a patient who previously had a colonoscopy with another physician, I always follow the previous recommendation for when the next colonoscopy should be, regardless of whether or not it technically meets guideline recommendations,” he told this news organization. “I do this because I was not there during the procedure and am not aware of any circumstances that would require a shorter interval that may not be apparent from the report.”

While he agrees with the new guidelines, Dr. Sreenivasan is “not sure if retroactively changing intervals is beneficial to patients, as the presence of guidelines may subconsciously influence the behavior of the endoscopist at the time of the procedure. For example, if a patient has a technically challenging colonoscopy and the endoscopist is running late, the endoscopist may drop their guard once they find a polyp and miss 1-2 additional small polyps that they would have spent more time looking for if they knew their next one would be in 10 years instead of 5.”

As for notification method, despite the logistical downside of taking dedicated staff time to make telephone calls, Dr. Sreenivasan said, “I think having a conversation with the patient directly is a much better way to communicate this information as it allows the patient to ask and answer questions. Things like tone of voice can provide reassurance that one cannot get via email.” Looking to the future, the study authors acknowledged that combinations of initial and reminder outreach approaches — for example, a mailed letter followed by secure message or telephone call — could potentially yield higher response rates and/or adoption rates than they observed. And a longer follow-up period with additional reminders may have produced higher yields. Additional studies are needed to optimize outreach approaches and to understand patient barriers to adopting the new guideline recommendations in different healthcare settings.

The study was supported by a Delivery Science grant from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Mansour and Dr. Sreenivasan disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to their comments.

In an article published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, a group led by Jeffrey K. Lee, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center in San Francisco, reported the following 60-day response rates for the three contact methods in potentially transitioning more than 600 post-polypectomy patients to the new interval:

- Telephone: 64.5%

- Secure messaging: 51.7%

- Mailed letter: 31.3%

Compared with letter outreach, overall rate differences were significant for telephone (18.1%) and secure message outreach (13.1%).

Such interventions are widely used, the authors noted , but have not been compared for efficacy terms of communicating updated colonoscopy intervals.

The trial’s aim was to inform low-risk patients of the recommended interval update from 5 years — used since the 1990s — to 7-10 years. Given a choice, more patients opted to transition to the 10-year surveillance interval in the telephone (37%) and secure messaging arms (32.%) compared with mailed-letter arm (18.9%).

In addition to telephone and secure messaging outreach, factors positively associated with adoption of the 10-year interval were a positive fecal immunochemical test–based index colonoscopy and increasing age. Patients with these characteristics may be biased toward avoiding colonoscopy if not medically necessary, the authors conjectured.

Inversely associated factors included Asian or Pacific Islander race (odds ratio .58), Hispanic ethnicity (OR .40), and a higher Charlson comorbidity score of 2 vs 0 (OR .43).

Possible explanations for the race and ethnicity associations include gaps in culturally component care, lack of engagement with the English-based outreach approaches, and medical mistrust, the authors said.

“In this study, we gave all our patients an option to either extend their surveillance interval to current guideline recommendations or continue with their old interval, and some chose to do that,” Dr. Lee said in an interview. “Patients really appreciated having a choice and to be informed about the latest guideline changes.”

“A critical challenge to health systems is how to effectively de-implement outdated surveillance recommendations for low-risk patients who have a 5-year follow-up interval and potentially transition them to the recommended 7- to 10-year interval,” Dr. Lee and colleagues wrote.

More than 5 million surveillance colonoscopies are performed annually in US patients with a history of adenomas, the main precursor lesion for colorectal cancer, the authors noted.

With the recent guidelines issued in 2020 by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer lengthening the follow-up interval to 7-10 years , physicians are being advised to reevaluate low-risk patients previously scheduled with 5-year surveillance and provide an updated recommendation for follow-up.

Study Details

The three-arm pragmatic randomized trial was conducted in low-risk patients 54-70 years of age with one or two small (< 10 mm) tubular adenomas at baseline colonoscopy. Participants due for 5-year surveillance in 2022 were randomly assigned to one of three outreach arms: telephone (n = 200], secure messaging (n = 203), and mailed letter (n = 201). Stratified by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, participants could change their assigned interval to 10 years or continue with their previously scheduled 5-year interval.

As to economic considerations, the authors said that telephone may be the costliest form of outreach in terms of staffing resources. “We don’t know because we did not conduct a formal cost-effectiveness analysis,” Dr. Lee said. “However, we do know phone outreach requires a lot of personnel effort, which is why we also explored the less costly option of secure messaging/email.”

But based on the findings, telephone outreach would be a reasonable approach to update patients on post-polypectomy surveillance guideline changes if secure messaging or text messaging isn’t available, he added.

Downsides to Retroactive Changes?

Commenting on the study but not involved in it, Nabil M. Mansour, MD, an assistant professor and director of the McNair General GI Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, noted that unlike Kaiser Permanente, his center decided against an overall effort to switch patients colonoscopied before the release of the new guidelines over to the new interval.

“Several of our physicians may have chosen to recommend a 5-year interval specifically for a variety of reasons and we felt going back, and making a blanket change to everyone’s interval retrospectively might create confusion and frustration and might actually delay the colonoscopies of some patients for which their doctors had a very good, legitimate reason to recommend a 5-year interval,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Mansour added that no difficulties were encountered in getting patients to agree to a 10-year interval. In his view telephone communication or in-person clinic visits are likely the most effective ways but both are more labor-intensive than automated patient portal messages. “I do not think traditional snail mail is effective.” His clinic uses automatic EMR reminders.

Offering another perspective on the study, Aditya Sreenivasan, MD, a gastroenterologist at Northwell Health in New York City, said his center has not reached out to correct the old intervals. “When I see a patient who previously had a colonoscopy with another physician, I always follow the previous recommendation for when the next colonoscopy should be, regardless of whether or not it technically meets guideline recommendations,” he told this news organization. “I do this because I was not there during the procedure and am not aware of any circumstances that would require a shorter interval that may not be apparent from the report.”

While he agrees with the new guidelines, Dr. Sreenivasan is “not sure if retroactively changing intervals is beneficial to patients, as the presence of guidelines may subconsciously influence the behavior of the endoscopist at the time of the procedure. For example, if a patient has a technically challenging colonoscopy and the endoscopist is running late, the endoscopist may drop their guard once they find a polyp and miss 1-2 additional small polyps that they would have spent more time looking for if they knew their next one would be in 10 years instead of 5.”

As for notification method, despite the logistical downside of taking dedicated staff time to make telephone calls, Dr. Sreenivasan said, “I think having a conversation with the patient directly is a much better way to communicate this information as it allows the patient to ask and answer questions. Things like tone of voice can provide reassurance that one cannot get via email.” Looking to the future, the study authors acknowledged that combinations of initial and reminder outreach approaches — for example, a mailed letter followed by secure message or telephone call — could potentially yield higher response rates and/or adoption rates than they observed. And a longer follow-up period with additional reminders may have produced higher yields. Additional studies are needed to optimize outreach approaches and to understand patient barriers to adopting the new guideline recommendations in different healthcare settings.

The study was supported by a Delivery Science grant from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Mansour and Dr. Sreenivasan disclosed no conflicts of interest relevant to their comments.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Obesity and lung disease in the era of GLP-1 agonists

Now is the time for pulmonary clinicians to become comfortable counseling patients about and treating obesity. By 2030, half of the US population will have obesity, a quarter of which will be severe (Ward et al. NEJM. 2019;2440-2450).

Many pulmonary diseases, including asthma, COPD, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) are linked to and made worse by obesity with increased exacerbations, patient-reported decreased quality of life, and resistance to therapy (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). Asthma is even recognized as an obesity-related comorbid condition by both the American Society Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) when considering indications for early or more aggressive treatment of obesity (Eisenberg et al. Obesity Surg. 2023;3-14) (Garvey et al. Endocr Pract. 2016;1-203).

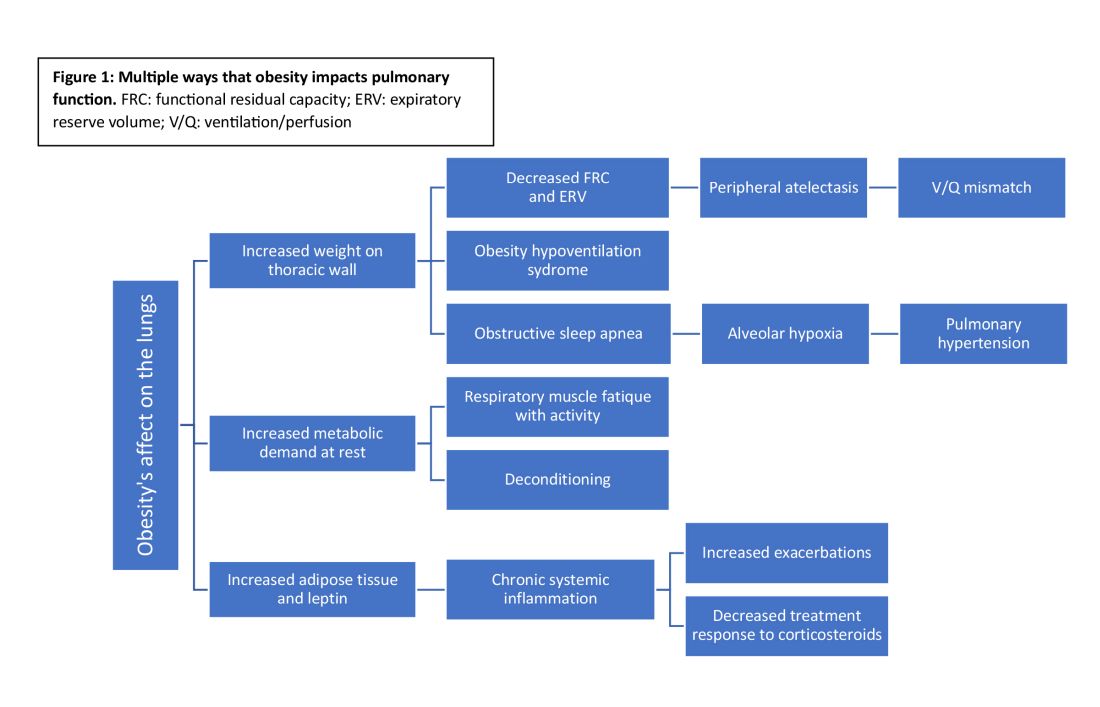

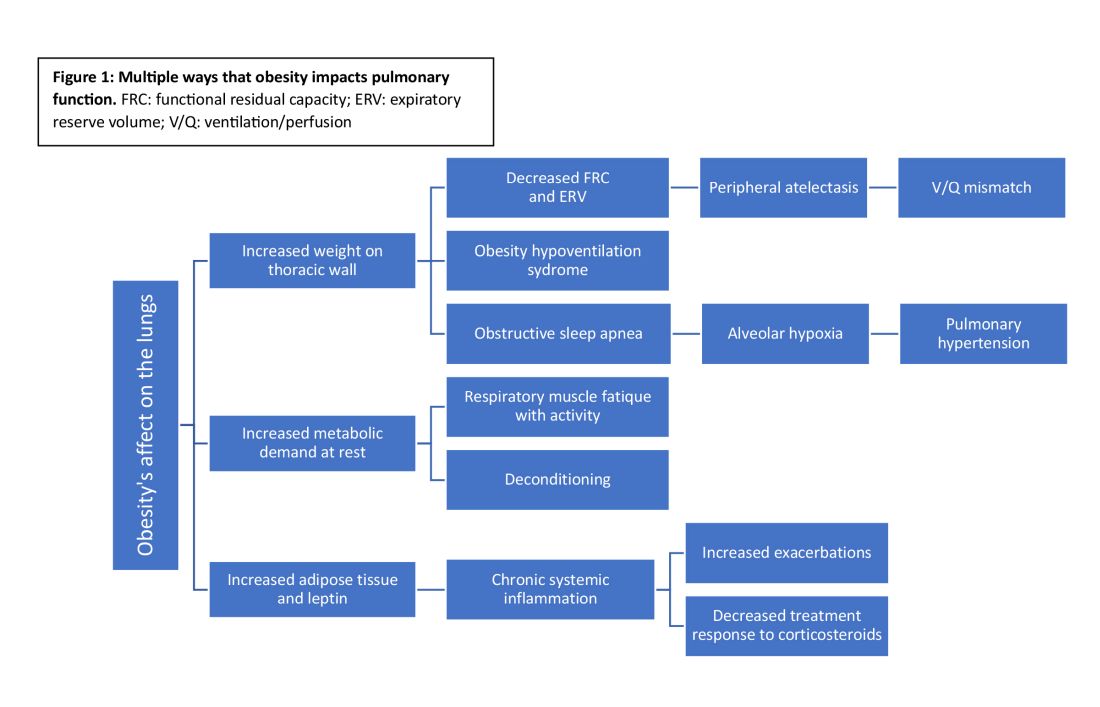

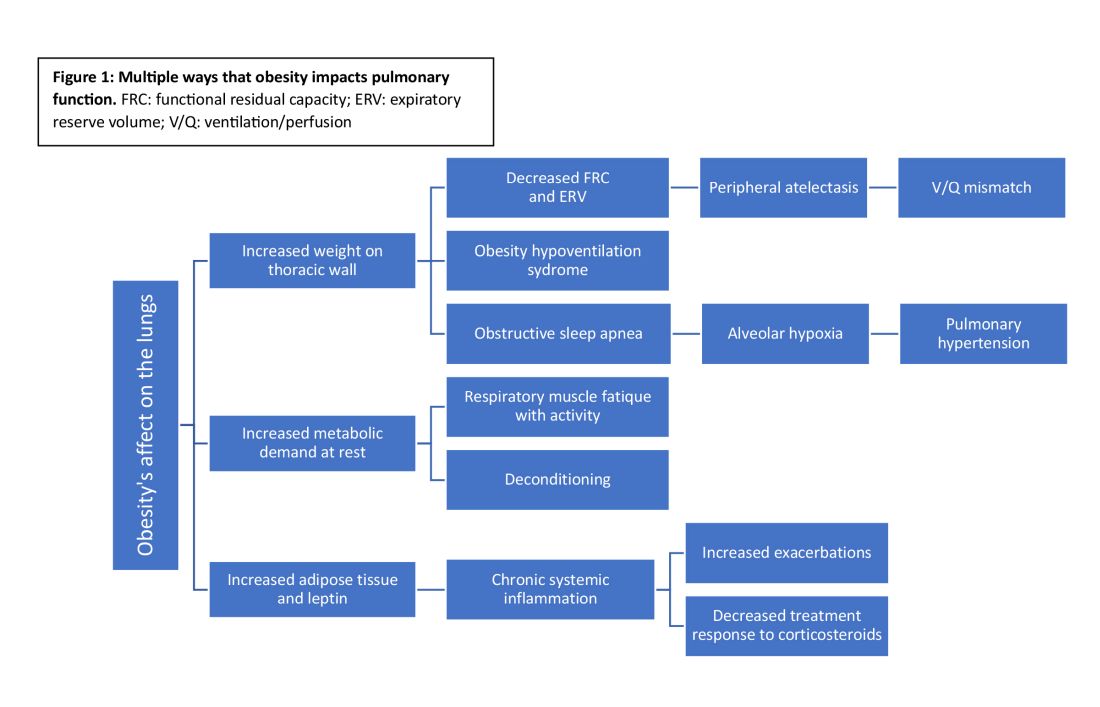

Obesity has multiple negative effects on pulmonary function due to the physical forces of extra weight on the lungs and inflammation related to adipose tissue (see Figure 1) (Zerah et al. Chest. 1993;1470-6).

Obesity-related respiratory changes include reduced lung compliance, functional residual capacity (FRC), and expiratory reserve volume (ERV). These changes lead to peripheral atelectasis and V/Q mismatch and increased metabolic demands placed on the respiratory system (Parameswaran et al. Can Respir J. 2006;203-10). The increased weight supported by the thoracic cage alters the equilibrium between the chest wall and lung tissue decreasing FRC and ERV. This reduces lung compliance and increases stiffness by promoting areas of atelectasis and increased alveolar surface tension (Dixon et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;755-67).

Another biomechanical cost of obesity on respiratory function is the increased consumption of oxygen to sustain ventilation at rest (Koenig SM, Am J Med Sci. 2001;249-79). This can lead to early respiratory muscle fatigue when respiratory rate and tidal volume increase with activity. Patients with obesity are more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. The resulting alveolar hypoxemia is thought to contribute to the increase in pulmonary hypertension observed in patients with obesity (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]). In addition to the biomechanical consequences of obesity, increased adipose tissue can lead to chronic, systemic inflammation that can exacerbate or unmask underlying respiratory disease. Increased leptin and downregulation of adiponectin have been shown to increase systemic cytokine production (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). This inflammatory process contributes to increased airway resistance and an altered response to corticosteroids (inhaled or systemic) in obese patients treated for bronchial hyperresponsiveness. This perhaps reflects the Th2-low phenotype seen in patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome-related asthma (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]) (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812).

Multiple studies have demonstrated weight loss through lifestyle changes, medical therapy, and obesity surgery result benefits pulmonary disease (Forno et al. PloS One. 2019;14[4]) (Ardila-Gatas et al. Surg Endosc. 2019;1952-8). Benefits include decreased exacerbation frequency, improved functional testing, and improved patient-reported quality of life. Pulmonary clinicians should be empowered to address obesity as a comorbid condition and treat with appropriate referrals for obesity surgery and initiation of medications when indicated.

GLP-1 receptor agonists

In the past year, glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have garnered attention in the medical literature and popular news outlets. GLP-1RAs, including semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, are currently FDA approved for the treatment of obesity in patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 or a BMI greater than or equal to 27 in the setting of an obesity-related comorbidity, including asthma.

This class of medications acts by increasing the physiologic insulin response to a glucose load, delaying gastric emptying, and reducing production of glucagon. In a phase III study, semaglutide resulted in greater than 15% weight reduction from baseline (Wadden et al. JAMA. 2021;1403-13). In clinical trials, these medications have not only resulted in significant, sustained weight loss but also improved lipid profiles, decreased A1c, and reduced major cardiovascular events (Lincoff et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389[23]:2221-32) (Verma et al. Circulation. 2018;138[25]:2884-94).

GLP-1RAs and lung disease

GLP-1RAs are associated with ranges of weight loss that lead to symptom improvement. Beyond the anticipated benefits for pulmonary health, there is interest in whether GLP-1RAs may improve specific lung diseases. GLP-1 receptors are found throughout the body (eg, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and heart) with the largest proportion located in the lungs (Wu AY and Peebles RS. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;1053-7). In addition to their known effect on insulin response, GLP-1RAs are hypothesized to reduce proinflammatory cytokine signaling and alter surfactant production potentially improving both airway resistance and lung compliance (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Animal models suggest an antifibrotic effect with delay in the endothelial-mesenchymal transition. If further substantiated, this could impact both acute and chronic lung injury.

Early clinical studies of GLP-1RAs in patients with respiratory diseases have demonstrated improved symptoms and pulmonary function (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Even modest weight loss (2.5 kg in a year) with GLP-1RAs leads to improved symptoms and a reduction in asthma exacerbations. Other asthma literature shows GLP-1RAs improve symptoms and reduce exacerbations independent of changes in weight, supporting the hypothesis that the benefit of GLP-1RAs may be more than biomechanical improvement from weight loss alone (Foer et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;831-40).

GLP-1RAs reduce the proinflammatory cytokine signaling in both TH2-high and TH2-low asthma phenotypes and alter surfactant production, airway resistance, and perhaps even pulmonary vascular resistance (Altintas Dogan et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022,405-14). GATA-3 is an ongoing clinical trial examining whether GLP-1RAs reduce airway inflammation via direct effects on of the respiratory tract (NCT05254314).

Drugs developed to treat one condition are often found to impact others during validation studies or postmarketing observation. Some examples are aspirin, sildenafil, minoxidil, hydroxychloroquine, and SGLT-2 inhibitors. Will GLP-1RAs be the latest medication to affect a broad array of physiologic process and end up improving not just metabolic but also lung health?

Now is the time for pulmonary clinicians to become comfortable counseling patients about and treating obesity. By 2030, half of the US population will have obesity, a quarter of which will be severe (Ward et al. NEJM. 2019;2440-2450).

Many pulmonary diseases, including asthma, COPD, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) are linked to and made worse by obesity with increased exacerbations, patient-reported decreased quality of life, and resistance to therapy (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). Asthma is even recognized as an obesity-related comorbid condition by both the American Society Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) when considering indications for early or more aggressive treatment of obesity (Eisenberg et al. Obesity Surg. 2023;3-14) (Garvey et al. Endocr Pract. 2016;1-203).

Obesity has multiple negative effects on pulmonary function due to the physical forces of extra weight on the lungs and inflammation related to adipose tissue (see Figure 1) (Zerah et al. Chest. 1993;1470-6).

Obesity-related respiratory changes include reduced lung compliance, functional residual capacity (FRC), and expiratory reserve volume (ERV). These changes lead to peripheral atelectasis and V/Q mismatch and increased metabolic demands placed on the respiratory system (Parameswaran et al. Can Respir J. 2006;203-10). The increased weight supported by the thoracic cage alters the equilibrium between the chest wall and lung tissue decreasing FRC and ERV. This reduces lung compliance and increases stiffness by promoting areas of atelectasis and increased alveolar surface tension (Dixon et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;755-67).

Another biomechanical cost of obesity on respiratory function is the increased consumption of oxygen to sustain ventilation at rest (Koenig SM, Am J Med Sci. 2001;249-79). This can lead to early respiratory muscle fatigue when respiratory rate and tidal volume increase with activity. Patients with obesity are more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. The resulting alveolar hypoxemia is thought to contribute to the increase in pulmonary hypertension observed in patients with obesity (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]). In addition to the biomechanical consequences of obesity, increased adipose tissue can lead to chronic, systemic inflammation that can exacerbate or unmask underlying respiratory disease. Increased leptin and downregulation of adiponectin have been shown to increase systemic cytokine production (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). This inflammatory process contributes to increased airway resistance and an altered response to corticosteroids (inhaled or systemic) in obese patients treated for bronchial hyperresponsiveness. This perhaps reflects the Th2-low phenotype seen in patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome-related asthma (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]) (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812).

Multiple studies have demonstrated weight loss through lifestyle changes, medical therapy, and obesity surgery result benefits pulmonary disease (Forno et al. PloS One. 2019;14[4]) (Ardila-Gatas et al. Surg Endosc. 2019;1952-8). Benefits include decreased exacerbation frequency, improved functional testing, and improved patient-reported quality of life. Pulmonary clinicians should be empowered to address obesity as a comorbid condition and treat with appropriate referrals for obesity surgery and initiation of medications when indicated.

GLP-1 receptor agonists

In the past year, glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have garnered attention in the medical literature and popular news outlets. GLP-1RAs, including semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, are currently FDA approved for the treatment of obesity in patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 or a BMI greater than or equal to 27 in the setting of an obesity-related comorbidity, including asthma.

This class of medications acts by increasing the physiologic insulin response to a glucose load, delaying gastric emptying, and reducing production of glucagon. In a phase III study, semaglutide resulted in greater than 15% weight reduction from baseline (Wadden et al. JAMA. 2021;1403-13). In clinical trials, these medications have not only resulted in significant, sustained weight loss but also improved lipid profiles, decreased A1c, and reduced major cardiovascular events (Lincoff et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389[23]:2221-32) (Verma et al. Circulation. 2018;138[25]:2884-94).

GLP-1RAs and lung disease

GLP-1RAs are associated with ranges of weight loss that lead to symptom improvement. Beyond the anticipated benefits for pulmonary health, there is interest in whether GLP-1RAs may improve specific lung diseases. GLP-1 receptors are found throughout the body (eg, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and heart) with the largest proportion located in the lungs (Wu AY and Peebles RS. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;1053-7). In addition to their known effect on insulin response, GLP-1RAs are hypothesized to reduce proinflammatory cytokine signaling and alter surfactant production potentially improving both airway resistance and lung compliance (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Animal models suggest an antifibrotic effect with delay in the endothelial-mesenchymal transition. If further substantiated, this could impact both acute and chronic lung injury.

Early clinical studies of GLP-1RAs in patients with respiratory diseases have demonstrated improved symptoms and pulmonary function (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Even modest weight loss (2.5 kg in a year) with GLP-1RAs leads to improved symptoms and a reduction in asthma exacerbations. Other asthma literature shows GLP-1RAs improve symptoms and reduce exacerbations independent of changes in weight, supporting the hypothesis that the benefit of GLP-1RAs may be more than biomechanical improvement from weight loss alone (Foer et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;831-40).

GLP-1RAs reduce the proinflammatory cytokine signaling in both TH2-high and TH2-low asthma phenotypes and alter surfactant production, airway resistance, and perhaps even pulmonary vascular resistance (Altintas Dogan et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022,405-14). GATA-3 is an ongoing clinical trial examining whether GLP-1RAs reduce airway inflammation via direct effects on of the respiratory tract (NCT05254314).

Drugs developed to treat one condition are often found to impact others during validation studies or postmarketing observation. Some examples are aspirin, sildenafil, minoxidil, hydroxychloroquine, and SGLT-2 inhibitors. Will GLP-1RAs be the latest medication to affect a broad array of physiologic process and end up improving not just metabolic but also lung health?

Now is the time for pulmonary clinicians to become comfortable counseling patients about and treating obesity. By 2030, half of the US population will have obesity, a quarter of which will be severe (Ward et al. NEJM. 2019;2440-2450).

Many pulmonary diseases, including asthma, COPD, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) are linked to and made worse by obesity with increased exacerbations, patient-reported decreased quality of life, and resistance to therapy (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). Asthma is even recognized as an obesity-related comorbid condition by both the American Society Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) when considering indications for early or more aggressive treatment of obesity (Eisenberg et al. Obesity Surg. 2023;3-14) (Garvey et al. Endocr Pract. 2016;1-203).

Obesity has multiple negative effects on pulmonary function due to the physical forces of extra weight on the lungs and inflammation related to adipose tissue (see Figure 1) (Zerah et al. Chest. 1993;1470-6).

Obesity-related respiratory changes include reduced lung compliance, functional residual capacity (FRC), and expiratory reserve volume (ERV). These changes lead to peripheral atelectasis and V/Q mismatch and increased metabolic demands placed on the respiratory system (Parameswaran et al. Can Respir J. 2006;203-10). The increased weight supported by the thoracic cage alters the equilibrium between the chest wall and lung tissue decreasing FRC and ERV. This reduces lung compliance and increases stiffness by promoting areas of atelectasis and increased alveolar surface tension (Dixon et al. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2018;755-67).

Another biomechanical cost of obesity on respiratory function is the increased consumption of oxygen to sustain ventilation at rest (Koenig SM, Am J Med Sci. 2001;249-79). This can lead to early respiratory muscle fatigue when respiratory rate and tidal volume increase with activity. Patients with obesity are more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome. The resulting alveolar hypoxemia is thought to contribute to the increase in pulmonary hypertension observed in patients with obesity (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]). In addition to the biomechanical consequences of obesity, increased adipose tissue can lead to chronic, systemic inflammation that can exacerbate or unmask underlying respiratory disease. Increased leptin and downregulation of adiponectin have been shown to increase systemic cytokine production (Ray et al. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;501-6). This inflammatory process contributes to increased airway resistance and an altered response to corticosteroids (inhaled or systemic) in obese patients treated for bronchial hyperresponsiveness. This perhaps reflects the Th2-low phenotype seen in patients with obesity and metabolic syndrome-related asthma (Shah et al. Breathe. 2023;19[1]) (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812).

Multiple studies have demonstrated weight loss through lifestyle changes, medical therapy, and obesity surgery result benefits pulmonary disease (Forno et al. PloS One. 2019;14[4]) (Ardila-Gatas et al. Surg Endosc. 2019;1952-8). Benefits include decreased exacerbation frequency, improved functional testing, and improved patient-reported quality of life. Pulmonary clinicians should be empowered to address obesity as a comorbid condition and treat with appropriate referrals for obesity surgery and initiation of medications when indicated.

GLP-1 receptor agonists

In the past year, glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) have garnered attention in the medical literature and popular news outlets. GLP-1RAs, including semaglutide, liraglutide, and tirzepatide, are currently FDA approved for the treatment of obesity in patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 or a BMI greater than or equal to 27 in the setting of an obesity-related comorbidity, including asthma.

This class of medications acts by increasing the physiologic insulin response to a glucose load, delaying gastric emptying, and reducing production of glucagon. In a phase III study, semaglutide resulted in greater than 15% weight reduction from baseline (Wadden et al. JAMA. 2021;1403-13). In clinical trials, these medications have not only resulted in significant, sustained weight loss but also improved lipid profiles, decreased A1c, and reduced major cardiovascular events (Lincoff et al. N Engl J Med. 2023;389[23]:2221-32) (Verma et al. Circulation. 2018;138[25]:2884-94).

GLP-1RAs and lung disease

GLP-1RAs are associated with ranges of weight loss that lead to symptom improvement. Beyond the anticipated benefits for pulmonary health, there is interest in whether GLP-1RAs may improve specific lung diseases. GLP-1 receptors are found throughout the body (eg, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and heart) with the largest proportion located in the lungs (Wu AY and Peebles RS. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;1053-7). In addition to their known effect on insulin response, GLP-1RAs are hypothesized to reduce proinflammatory cytokine signaling and alter surfactant production potentially improving both airway resistance and lung compliance (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Animal models suggest an antifibrotic effect with delay in the endothelial-mesenchymal transition. If further substantiated, this could impact both acute and chronic lung injury.

Early clinical studies of GLP-1RAs in patients with respiratory diseases have demonstrated improved symptoms and pulmonary function (Kanwar et al. Cureus. 2022 Oct 28. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30812). Even modest weight loss (2.5 kg in a year) with GLP-1RAs leads to improved symptoms and a reduction in asthma exacerbations. Other asthma literature shows GLP-1RAs improve symptoms and reduce exacerbations independent of changes in weight, supporting the hypothesis that the benefit of GLP-1RAs may be more than biomechanical improvement from weight loss alone (Foer et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;831-40).

GLP-1RAs reduce the proinflammatory cytokine signaling in both TH2-high and TH2-low asthma phenotypes and alter surfactant production, airway resistance, and perhaps even pulmonary vascular resistance (Altintas Dogan et al. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022,405-14). GATA-3 is an ongoing clinical trial examining whether GLP-1RAs reduce airway inflammation via direct effects on of the respiratory tract (NCT05254314).

Drugs developed to treat one condition are often found to impact others during validation studies or postmarketing observation. Some examples are aspirin, sildenafil, minoxidil, hydroxychloroquine, and SGLT-2 inhibitors. Will GLP-1RAs be the latest medication to affect a broad array of physiologic process and end up improving not just metabolic but also lung health?

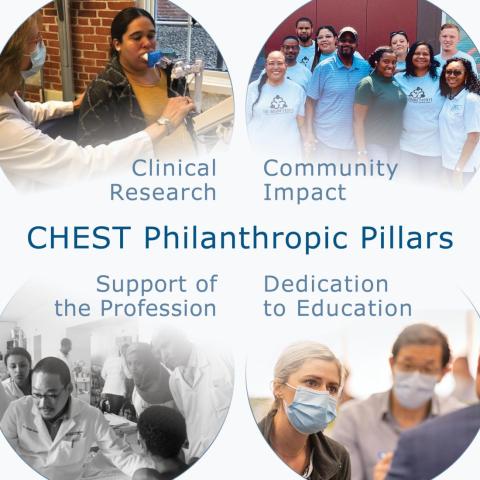

New age of CHEST philanthropy to focus on education, impact, community

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

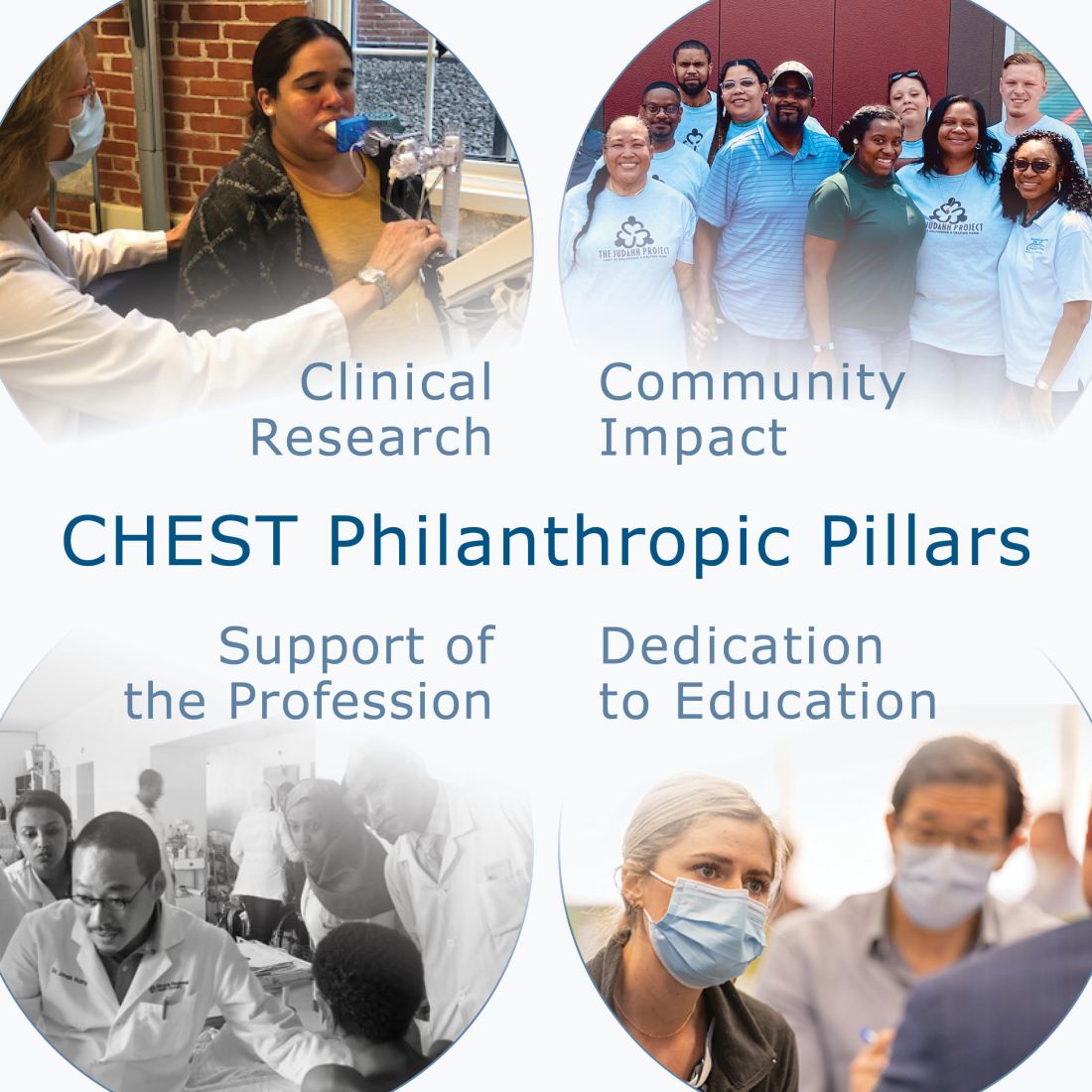

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

In a time echoing with the constant call for transformation, CHEST delved deep into its essence, questioning its potential for impact. This pivotal introspection led to a crucial inquiry…

Are we harnessing every opportunity to make a difference?

It’s a familiar question, yet its resonance urged a deeper evaluation.

Philanthropy has long been entwined in CHEST’s identity. Commemorating 25 years of the CHEST Foundation at CHEST 2022 spotlighted our history of generosity. Stories of transformative community initiatives and pivotal clinical research grants narrated a tale of empowered change and fostering healthier communities worldwide.

However, amid these achievements, more pressing inquiries surfaced:

- What unique role can CHEST play?

- Where do unmet needs persist?

- Which causes deeply resonate within our community?

CHEST’s leadership and dedicated staff embarked on a comprehensive review, scrutinizing past triumphs, donor commitments, and the evolving aspirations of our members. Themes of social responsibility, professional diversity, community impact, and expanded partnerships emerged as pivotal points. This extensive process, spanning nearly a year, resembled a reflective pause amid the rapid cadence of change.

Achieving these aspirations meant reimagining our approach, thereby streamlining efforts for maximal impact by…

- Integrating philanthropy as an integral facet of our mission, and amplifying the culture of giving within CHEST

- Consolidating philanthropic initiatives under CHEST to maximize resources for direct, substantial impact

- Defining clear avenues for giving that deeply resonate with our members

With endorsement from the Board of Regents, the CHEST Foundation seamlessly merged into CHEST, inaugurating a new chapter in our philanthropic endeavors.

Central to this transformative shift is the crystallization of our giving strategy, fortified by four pillars: Clinical Research, Community Impact, Support to the Profession, and Dedication to Education. These pillars encapsulate our commitment to nurturing clinicians, supporting trainees, and enhancing patient care.

Clinical Research emerges as the cornerstone, transcending boundaries to empower researchers in their pursuit of groundbreaking insights. Through strategic grants, we embolden early career investigators to delve into uncharted territories, unraveling mysteries that underpin advancements in chest medicine. The ripple effect extends beyond labs; it traverses communities, amplifying equitable health care solutions and bridging disparities in patient care. Our commitment to nurturing this pillar springs from the belief that every breakthrough, regardless of scale, is a catalyst for transformative change.

Community Impact extends CHEST’s reach far beyond clinical settings, fostering alliances with local organizations. Together, we forge a tapestry of collaboration, weaving essential services and imparting knowledge on crucial lung health issues into the fabric of diverse communities. This engagement not only elevates awareness but also empowers individuals and communities to take charge of their respiratory well-being. It’s the grassroots unity that amplifies our impact, creating enduring shifts in local landscapes.

Support of the Profession epitomizes our dedication to fortifying the backbone of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine. By offering unparalleled clinical education and mentorship, we empower emerging clinicians from diverse backgrounds with the latest knowledge and resources. Fueling their professional growth is pivotal to nurturing a robust and inclusive cadre of health care professionals, ensuring comprehensive and culturally sensitive care for patients worldwide.

Dedication to Education isn’t just a commitment—it’s a bridge spanning the gap between knowledge and application, patient and clinician. Strengthening this connection involves equipping clinicians with tools for effective communication and partnering with patient-centered organizations. Our focus transcends textbooks; it embodies a relentless pursuit to refine patient-clinician interactions, enhancing patient understanding and, ultimately, elevating their quality of life.

CHEST’s philanthropic evolution signifies not just growth but a resolute commitment to effecting tangible change in chest medicine and patient care. These pillars stand as guiding beacons, steering us toward a future that mirrors our mission, vision, and values. Each pillar represents a pathway to meaningful, enduring change within chest medicine, ensuring a lasting impact on patient well-being.

Biomarker checklist seeks to expedite NSCLC diagnoses

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Drs. Tamer Said Ahmed and Adam Fox receive funding for quality improvement projects in biomarker testing

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Establishing a systematic biomarker testing program for patients with suspected non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) takes both time and collaboration across specialties. To standardize this process, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) created two clinician checklists for use in practice.

The case-by-case checklist helps guide physicians to ensure timely and comprehensive biomarker testing for individual patients, and the programmatic/institutional checklist is for multidisciplinary teams to enable clear expectations and processes across hand-offs to aid in the testing process.

To substantiate best practices for ordering biomarker tests using the checklists, CHEST issued quality improvement demonstration grants for implementation at two institutions. This year, Tamer Said Ahmed, MD, FCCP, pulmonary and sleep physician at Toledo Hospital (ProMedica Health System) and Assistant Professor at the University of Toledo, and Adam Fox, MD, MS, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, will begin projects to improve biomarker testing.

“Biomarker testing allows for tailored treatment plans that drastically impact the progression of lung cancer, but every hospital system and practice is following a different procedure for testing,” Dr. Said Ahmed said. “To best serve the patient, our project aims to streamline the approach to biomarker testing to bridge health care inconsistencies. Given the intense progression of some forms of lung cancer where every week matters, the more streamlined we can make the biomarker testing process, the earlier we will get to an accurate diagnosis, begin treatment, and likely extend the life of a patient.”

Discrepancies in the testing process stem from existing silos between specialties, including pathology, oncology, interventional radiology, and more. Care is fragmented, leading to delays like repeat biopsies because a large enough sample was not taken the first time.

This is the exact problem that checklist implementation will seek to solve.

“By intent, these checklists help to provide a systematic approach to timely and comprehensive biomarker testing,” said Dr. Fox, who was also part of the team that developed the checklists. “What we need now is to implement them into clinical practice to gain metrics that can be studied, identified, and will lead to the process being widely accepted. To truly impact practice, we need to be able to provide strong evidence for interventions that work for clinicians to implement.”

To learn more and download the checklists, visit CHEST’s Thoracic Oncology Topic Collection onlineThis project is supported in part by AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Pfizer.

Examining the past and looking toward the future: The need for quality data in interventional pulmonology

THORACIC ONCOLOGY AND CHEST PROCEDURES NETWORK

Interventional Procedures Section