User login

Bedside Ultrasound for Pulsatile Hand Mass

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

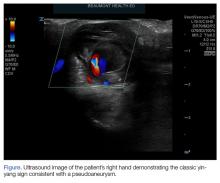

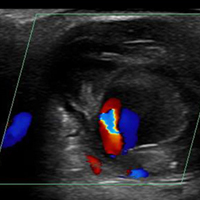

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

Case

A 23-year-old man presented to an outside hospital’s ED for evaluation of a wound on his right hand, which he sustained after he accidentally stabbed himself with a steak knife. At presentation, the patient’s vital signs were: heart rate, 90 beats/min; respiratory rate, 16 breaths/min; blood pressure, 150/92 mm Hg; and temperature, 98.1°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air. Examination revealed a laceration on the patient’s right hand measuring 2 cm in length. The emergency physician (EP) closed the wound using four nylon sutures and administered a Boostrix shot. The patient was discharged home with a prescription for cephalexin capsule 500 mg to be taken four times daily for 5 days. He was instructed to return in 10 days for suture removal, but failed to follow-up.

The patient presented to our ED two months after the initial injury for evaluation of a 1.5-cm round pulsatile mass on his right palm, at the base of the middle finger, from which exuded a small amount of sanguineous fluid. The patient complained of numbness and difficulty extending his right index and middle fingers.

Discussion

Palmar Pseudoaneurysms

A pseudoaneurysm, also referred to as a traumatic aneurysm, develops when a tear of the vessel wall and hemorrhage is contained by a thin-walled capsule, typically following traumatic perforation of the arterial wall. Unlike a true aneurysm, a pseudoaneurysm does not contain all three layers of intima, media, and adventitia. Thin walls lead to inevitable expansion over time; in some cases, a patient will present with a soft-tissue mass years after the initial injury. Compression of nearby structures can cause neuropathy, peripheral edema, venous thrombosis, arterial occlusion or emboli, and even bone erosion.1,2

Hand pseudoaneurysms are more likely to occur on the palmar surface, involving the superficial palmar arch,3 and are due to a penetrating injury or repetitive microtrauma. Hypothenar hammer syndrome occurs when repetitive microtrauma is applied to the ulnar artery as it passes under the hook of the hamate bone into the hand. This condition is also referred to as “hammer hand syndrome” because it frequently occurs in laborers such as mechanics, carpenters, and machinists as a result of repetitive palm trauma. Cases have also been reported in baseball players and cooks who also expose their hands to repetitive trauma.3 Likewise, elderly patients who use walking canes can also present with bilateral hammer hand syndrome,3 and patients who need crutches for a prolonged period of time may also develop axillary artery aneurysms.1,2

Although rare, there have also been cases of spontaneous hand pseudoaneurysms in patients on anticoagulation therapy;4,5 however, pseudoaneurysms are not an absolute contraindication to initiating or continuing use of anticoagulants.

Evaluation

Physical Examination. The patient’s mass in this case was clearly pulsatile on examination, but physical examination alone is not a reliable indicator of pseudoaneurysm, as patients may present only with soft-tissue swelling, pain, erythema, or neurological symptoms.3,6,7

Ultrasound Imaging. In the emergency setting, POC ultrasound should be performed to evaluate any soft-tissue hand mass, especially in the context of trauma or any neurovascular findings, since palmar pseudoaneurysms can easily be confused with an abscess, foreign body, cyst, or even a tendon tear.6 Ultrasound studies using the linear vascular probe should always be done before any attempt to incise and drain the mass.

Three ultrasound characteristics of pseudoaneurysms include expansile pulsatility, turbulent flow with a classic yin-yang sign on Doppler, and a hematoma with variable echogenicity. Variable echogenicity may represent separate episodes of bleeding and rebleeding.8 A “to-and-fro” spectral waveform is pathognomonic for palmar pseudoaneurysms.8

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Definitive imaging for operative management includes computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography to assess for the exact location and presence of collateral circulation.

Treatment

Treatment of pseudoaneurysms includes conservative compression therapy, surgical excision, or anastomosis, and more recently, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection (UGTI).

Compression Therapy. Compression therapy is often used for femoral artery pseudoaneurysms that develop after iatrogenic injury. However, this technique is time consuming, is uncomfortable for patients, is not effective in treating large pseudoaneurysms, and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation therapy. Compression therapy also has a high-failure rate of resolving pseudoaneurysms. Traditionally, surgical excision or anastomosis has been the definitive treatment for palmar pseudoaneurysms.

Ultrasound-Guided Thrombin Injection. A more recent treatment option is UGTI, which is usually performed by an interventional radiologist. Although there is no consensus on exact dose of thrombin for this procedure, the literature describes UGTI to treat both the radial and ulnar arteries.9,10 One study of 83 pseudoaneurysms demonstrated a relationship between the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm and the number of thrombin injections required to resolve it. Depending on the size of the palmar pseudoaneurysm, the effective thrombin doses ranged from 200 to 2,500 U. Regarding adverse effects and events from treatment, this study reported one case of transient distal ischemia.11

Intravascular balloon occlusion of the pseudoaneurysm neck has also been recommended for UGTI in the femoral artery if the neck is greater than 1 mm, but there is currently nothing in the literature describing its use in palmar pseudoaneurysms.12

Complications

There are more descriptions of palmar, radial, and ulnar pseudoaneurysms in critical care patients due to the frequent, but necessary, use of invasive lines. Emergency physicians frequently place radial or femoral arterial lines for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients. However, the incidence of pseudoaneurysms and its sequelae from these lines are not usually observed in the ED setting.

Radial arterial lines may cause thrombosis in 19% to 57% of cases, and local infection in 1% to 18% of cases.10 In a study of 12,500 patients with radial artery catheters, the rate of radial pseudoaneurysm was only 0.05%.11 Although this is a small complication rate, pseudoaneurysms can lead to significant loss of function. To decrease the number of attempts and penetrating injuries to the arteries, ultrasound guidance for these procedures in the ED is strongly recommended. In addition to decreasing the risk of developing a pseudoaneurysm, ultrasound-guidance decreases the discomfort level of the patient and reduces the risk of bleeding, hematoma formation, and infection. Arterial line placement in the ED using ultrasound guidance decreases the risk of developing pseudoaneurysms and their sequelae, such as distal embolization.

Case Conclusion

The patient in this case underwent an arterial duplex study, which found a partially thrombosed right superficial palmar arch pseudoaneurysm measuring 1.91 cm x 2.08 cm, with an active flow area measuring 0.58 cm x 0.68 cm. The flow to the index finger medial artery and middle finger lateral artery was also diminished. The patient was discharged home with a bulky soft dressing and underwent excision and repair by hand surgery 3 days later. At the 1-month postoperative follow-up visit, the patient had full sensation but mildly decreased range of motion in his fingers.

Summary

Hand pseudoaneurysms are often associated with penetrating injuries—as demonstrated in our case—or repetitive microtrauma. Hand pseudoaneurysms can present with minimal findings such as isolated soft-tissue swelling, pain, or neuropathy. The EP should consider vascular pathology in the differential for patients who present with posttraumatic neuropathy. Regarding imaging studies, ultrasound is the best imaging modality to assess for pseudoaneurysms, and EPs should have a low threshold for its use at bedside—especially prior to attempting any invasive procedure. Patients with a confirmed pseudoaneurysm should be referred to a hand or vascular surgeon for surgical repair, or to an interventional radiologist for UGTI.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

1. Newton EJ, Arora S. Peripheral vascular injury. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:502.

2. Aufderheide TP. Peripheral arteriovascular disease. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, et al, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. Vol 1. 8th ed. 2014:1147-1149.

3. Anderson SE, De Monaco D, Buechler U, et al. Imaging features of pseudoaneurysms of the hand in children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(3):659-664. doi:10.2214/ajr.180.3.1800659.

4. Shah S, Powell-Brett S, Garnham A. Pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of post-traumatic hand swelling. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015. pii: bcr2014208750. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-208750.

5. Kitamura A, Mukohara N. Spontaneous pseudoaneurysm of the hand. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(3):739.e1-e3. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2013.04.033.

6. Huang SW, Wei TS, Liu SY, Wang WT. Spontaneous totally thrombosed pseudoaneurysm mimicking a tendon tear of the wrist. Orthopedics. 2010;33(10):776. doi:10.3928/01477447-20100826-23.

7. Belyayev L, Rich NM, McKay P, Nesti L, Wind G. Traumatic ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm following a grenade blast: report of a case. Mil Med. 2015;180(6):e725-e727. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00400.

8. Pero T, Herrick J. Pseudoaneurysm of the radial artery diagnosed by bedside ultrasound. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10(2):89-91.

9. Bosman A, Veger HTC, Doornink F, Hedeman Joosten PPA. A pseudoaneurysm of the deep palmar arch after penetrating trauma to the hand: successful exclusion by ultrasound guided percutaneous thrombin injection. EJVES Short Rep. 2016;31:9-11. doi:10.1016/j.ejvssr.2016.03.002.

10. Komorowska-Timek E, Teruya TH, Abou-Zamzam AM Jr, Papa D, Ballard JL. Treatment of radial and ulnar artery pseudoaneurysms using percutaneous thrombin injection. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A(5):936-942. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2004.05.009.

11. Falk PS, Scuderi PE, Sherertz RJ, Motsinger SM. Infected radial artery pseudoaneurysms occurring after percutaneous cannulation. Chest. 1992;101(2):490-495.

12. Kang SS, Labropoulos N, Mansour MA, et al. Expanded indications for ultrasound-guided thrombin injection of pseudoaneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31(2):289-298.

Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for CTEPH improves heart failure symptoms

WASHINGTON – Balloon pulmonary angioplasty provides meaningful improvements in functional capacity for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) who are not candidates for surgical pulmonary thromboendarterectomy, according to a single-center experience with 15 consecutive patients that was presented at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

The treatment of choice for CTEPH is pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), but “a huge percentage of the population with CTEPH” is not eligible or does not undergo surgical treatment, which was the impetus to initiate this intervention, reported Riyaz Bashir, MD, director of vascular and endovascular medicine at Temple University Hospital and professor of medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

There have now been 15 CTEPH patients treated with BPA by Dr. Bashir and his team at Temple University. He reported 6-month outcome data on the first 13 patients, all of whom had a history of pulmonary embolism. Three of the patients had a prior PTE.

The primary outcome of interest in this series was functional improvement. Unlike PTE, immediate improvement in hemodynamics is not typically observed immediately after the procedure, but these measures do improve incrementally over time, Dr. Bashir reported. This is reflected in progressive improvements in the 6-minute walk test and in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class.

Of the 13 patients treated so far, 6 (46%) were in NYHA class IV and only 2 (15%) were in NYHA class II prior to BPA. Six months after BPA, the proportions had reversed. At that point, seven patients (54%) were in class II and two (15%) in class IV. The remaining patients at both time points were in NYHA class III. Similar improvements were seen in the 6-minute walk test, which typically tracks with NYHA class.

Describing the first case, performed about 2 years ago, Dr. Bashir explained that a tight stenosis in the right lower pulmonary artery of a 44-year-old woman was reached with a multipurpose guiding catheter through femoral access. A 5-mm balloon was used to dilate the stenosis and create a pulsatile flow.

“The goal is not to raise the mean arterial pressure above 35 mm Hg, because this has been associated with significant peripheral edema,” Dr. Bashir explained.

In this patient, progressive improvements in pulmonary pressure, cardiac index, and other hemodynamics were associated with progressive shrinking of the right ventricle over 6 months of follow-up. The walk test improved from 216 m prior to BPA to 421 m at her most recent evaluation.

The average age in the 13 patients treated so far was 55 years, and 75% are males. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 55%. According to Dr. Bashir, most patients required at least two treatment sessions and some have required up to four.

There have been two complications – one patient developed hemoptysis that required a brief intubation and the other involved perfusion edema – and no deaths in this series so far, he said.

The outcomes so far, which Dr. Bashir characterized as “an early experience,” provide evidence that BPA is “safe and feasible” for patients with CTEPH who are not surgical candidates. At Dr. Bashir’s institution, where PTE is commonly performed in patients with CTEPH (Dr. Bashir reported that 134 cases were performed over the period of time in which these 15 cases of BPA were performed), there is a plan to compare functional outcomes in CTEPH patients managed with these two different approaches.

Dr. Bashir reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Bashir R. CRT 2018

WASHINGTON – Balloon pulmonary angioplasty provides meaningful improvements in functional capacity for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) who are not candidates for surgical pulmonary thromboendarterectomy, according to a single-center experience with 15 consecutive patients that was presented at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

The treatment of choice for CTEPH is pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), but “a huge percentage of the population with CTEPH” is not eligible or does not undergo surgical treatment, which was the impetus to initiate this intervention, reported Riyaz Bashir, MD, director of vascular and endovascular medicine at Temple University Hospital and professor of medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

There have now been 15 CTEPH patients treated with BPA by Dr. Bashir and his team at Temple University. He reported 6-month outcome data on the first 13 patients, all of whom had a history of pulmonary embolism. Three of the patients had a prior PTE.

The primary outcome of interest in this series was functional improvement. Unlike PTE, immediate improvement in hemodynamics is not typically observed immediately after the procedure, but these measures do improve incrementally over time, Dr. Bashir reported. This is reflected in progressive improvements in the 6-minute walk test and in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class.

Of the 13 patients treated so far, 6 (46%) were in NYHA class IV and only 2 (15%) were in NYHA class II prior to BPA. Six months after BPA, the proportions had reversed. At that point, seven patients (54%) were in class II and two (15%) in class IV. The remaining patients at both time points were in NYHA class III. Similar improvements were seen in the 6-minute walk test, which typically tracks with NYHA class.

Describing the first case, performed about 2 years ago, Dr. Bashir explained that a tight stenosis in the right lower pulmonary artery of a 44-year-old woman was reached with a multipurpose guiding catheter through femoral access. A 5-mm balloon was used to dilate the stenosis and create a pulsatile flow.

“The goal is not to raise the mean arterial pressure above 35 mm Hg, because this has been associated with significant peripheral edema,” Dr. Bashir explained.

In this patient, progressive improvements in pulmonary pressure, cardiac index, and other hemodynamics were associated with progressive shrinking of the right ventricle over 6 months of follow-up. The walk test improved from 216 m prior to BPA to 421 m at her most recent evaluation.

The average age in the 13 patients treated so far was 55 years, and 75% are males. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 55%. According to Dr. Bashir, most patients required at least two treatment sessions and some have required up to four.

There have been two complications – one patient developed hemoptysis that required a brief intubation and the other involved perfusion edema – and no deaths in this series so far, he said.

The outcomes so far, which Dr. Bashir characterized as “an early experience,” provide evidence that BPA is “safe and feasible” for patients with CTEPH who are not surgical candidates. At Dr. Bashir’s institution, where PTE is commonly performed in patients with CTEPH (Dr. Bashir reported that 134 cases were performed over the period of time in which these 15 cases of BPA were performed), there is a plan to compare functional outcomes in CTEPH patients managed with these two different approaches.

Dr. Bashir reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Bashir R. CRT 2018

WASHINGTON – Balloon pulmonary angioplasty provides meaningful improvements in functional capacity for patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) who are not candidates for surgical pulmonary thromboendarterectomy, according to a single-center experience with 15 consecutive patients that was presented at CRT 2018 sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

The treatment of choice for CTEPH is pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (PTE), but “a huge percentage of the population with CTEPH” is not eligible or does not undergo surgical treatment, which was the impetus to initiate this intervention, reported Riyaz Bashir, MD, director of vascular and endovascular medicine at Temple University Hospital and professor of medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia.

There have now been 15 CTEPH patients treated with BPA by Dr. Bashir and his team at Temple University. He reported 6-month outcome data on the first 13 patients, all of whom had a history of pulmonary embolism. Three of the patients had a prior PTE.

The primary outcome of interest in this series was functional improvement. Unlike PTE, immediate improvement in hemodynamics is not typically observed immediately after the procedure, but these measures do improve incrementally over time, Dr. Bashir reported. This is reflected in progressive improvements in the 6-minute walk test and in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class.

Of the 13 patients treated so far, 6 (46%) were in NYHA class IV and only 2 (15%) were in NYHA class II prior to BPA. Six months after BPA, the proportions had reversed. At that point, seven patients (54%) were in class II and two (15%) in class IV. The remaining patients at both time points were in NYHA class III. Similar improvements were seen in the 6-minute walk test, which typically tracks with NYHA class.

Describing the first case, performed about 2 years ago, Dr. Bashir explained that a tight stenosis in the right lower pulmonary artery of a 44-year-old woman was reached with a multipurpose guiding catheter through femoral access. A 5-mm balloon was used to dilate the stenosis and create a pulsatile flow.

“The goal is not to raise the mean arterial pressure above 35 mm Hg, because this has been associated with significant peripheral edema,” Dr. Bashir explained.

In this patient, progressive improvements in pulmonary pressure, cardiac index, and other hemodynamics were associated with progressive shrinking of the right ventricle over 6 months of follow-up. The walk test improved from 216 m prior to BPA to 421 m at her most recent evaluation.

The average age in the 13 patients treated so far was 55 years, and 75% are males. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 55%. According to Dr. Bashir, most patients required at least two treatment sessions and some have required up to four.

There have been two complications – one patient developed hemoptysis that required a brief intubation and the other involved perfusion edema – and no deaths in this series so far, he said.

The outcomes so far, which Dr. Bashir characterized as “an early experience,” provide evidence that BPA is “safe and feasible” for patients with CTEPH who are not surgical candidates. At Dr. Bashir’s institution, where PTE is commonly performed in patients with CTEPH (Dr. Bashir reported that 134 cases were performed over the period of time in which these 15 cases of BPA were performed), there is a plan to compare functional outcomes in CTEPH patients managed with these two different approaches.

Dr. Bashir reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Bashir R. CRT 2018

REPORTING FROM CRT 2018

Key clinical point: Balloon pulmonary angioplasty has clinical benefits in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) patients not candidates for surgery.

Major finding: At baseline, only 30% of CTEPH patients were at or below NYHA class II, rising to 65% 6 months after balloon pulmonary angioplasty.

Data source: Single-center review of 15 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Bashir reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Source: Bashir R. CRT 2018

Failure to find cancer earlier; patient dies: $4.69M verdict

Failure to find cancer earlier; patient dies: $4.69M verdict

On July 19, a 26-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with abnormal vaginal bleeding 3 months after giving birth. She was found to have endometrial thickening and an elevated ß human chorionic gonadotropin level. An ObGyn (Dr. A) assumed that the patient was having a miscarriage and sent her home.

On July 30, when the patient returned to the ED with continued bleeding, lesions on her cervix and urethra were discovered. A second ObGyn, Dr. B, addressed the bleeding, removed the lesion, and ordered testing. On August 17, the patient saw a third ObGyn (Dr. C), who did not conduct an examination.

Days later, the patient suffered a brain hemorrhage that was suspicious for hemorrhagic metastasis. After that, stage IV choriocarcinoma was identified. Although she underwent chemotherapy, the patient died 18 months later.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: All 3 ObGyns failed to take a proper history, conduct adequate examinations, and order appropriate testing. Even at stage IV, 75% of patients with choriocarcinoma survive past 5 years. The stroke rendered chemotherapy less effective and substantially contributed to the patient's death. Failure to diagnose the cancer before the stroke allowed the disease to progress beyond the point at which the patient's life could be saved.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The ObGyns and hospital claimed that appropriate care was provided and that they were not negligent in failing to consider the diagnosis of a very rare form of cancer.

VERDICT: A $4.69 million New Jersey verdict was returned, with all 3 physicians held partially liable.

Hot speculum burns patient: $547,090 award

A 54-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy performed at a government-operated hospital. After she was anesthetized and unconscious, a second-year resident took a speculum that had been placed in the sterile field by a nurse, and inserted it in the patient's vagina.

When the patient awoke from surgery, she discovered significant burns to her vaginal area, perineum, anus, and buttocks.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The speculum had just been removed from the autoclave and was very hot. The patient incurred substantial medical bills to treat her injuries and was unable to work for several months. She sued the hospital and resident, alleging error by the nurse in placing the hot speculum in the sterile field without cooling it or advising the resident that it was still hot. The resident was blamed for using the speculum without confirming that it was hot.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The resident claimed that she reasonably relied on the nurse to not place a hot instrument in the surgical field without first cooling it. The hospital, representing the nurse, denied fault, blaming the resident for not checking the speculum.

VERDICT: A $547,090 Louisiana verdict was awarded by a judge against the resident and the hospital, but it was halved by comparative fault to $273,545.

Surgeon's breast exam insufficient: $375,000 verdict

After a woman in her early 40s found a lump in her left breast, she underwent a radiographic study, which a radiologist interpreted as showing a 3-mm cyst. Without performing additional tests, a general surgeon immediately scheduled her for surgery.

On May 17, the radiologist performed an ultrasound-guided needle-localized biopsy and found a nodule. The patient was immediately sent to the operating room where the surgeon performed a segmental resection of the nodule.

On May 24, the patient presented to the surgeon's office for a postoperative visit. She told the nurse that the palpable mass was still there. The nurse examined the mass, told the patient that the incision was healing nicely, and suggested follow-up in a month.

Four months later, the patient sought a second opinion. On September 15, she underwent a diagnostic mammogram, ultrasound, and biopsy. The biopsy was positive for invasive ductal carcinoma. On September 30, magnetic resonance imaging and a second biopsy further confirmed the diagnosis. On November 2, she underwent a segmental mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. The pathology report noted a 3-cm invasive ductal carcinoma with necrosis. The patient underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She sued the general surgeon, radiologist, and surgical center, alleging that her breast cancer went undiagnosed. Prior to trial, the radiologist and surgical center were dismissed from the case.

The surgeon failed to perform a thorough physical examination and nodal evaluation of the left breast and axilla. His substandard methods to diagnose and treat the patient's breast cancer delayed proper treatment and significantly altered the outcome.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: The surgeon's treatment met the standard of care. The outcome and treatment were not significantly changed by the delay.

VERDICT: A $375,000 Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Failure to find cancer earlier; patient dies: $4.69M verdict

On July 19, a 26-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with abnormal vaginal bleeding 3 months after giving birth. She was found to have endometrial thickening and an elevated ß human chorionic gonadotropin level. An ObGyn (Dr. A) assumed that the patient was having a miscarriage and sent her home.

On July 30, when the patient returned to the ED with continued bleeding, lesions on her cervix and urethra were discovered. A second ObGyn, Dr. B, addressed the bleeding, removed the lesion, and ordered testing. On August 17, the patient saw a third ObGyn (Dr. C), who did not conduct an examination.

Days later, the patient suffered a brain hemorrhage that was suspicious for hemorrhagic metastasis. After that, stage IV choriocarcinoma was identified. Although she underwent chemotherapy, the patient died 18 months later.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: All 3 ObGyns failed to take a proper history, conduct adequate examinations, and order appropriate testing. Even at stage IV, 75% of patients with choriocarcinoma survive past 5 years. The stroke rendered chemotherapy less effective and substantially contributed to the patient's death. Failure to diagnose the cancer before the stroke allowed the disease to progress beyond the point at which the patient's life could be saved.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The ObGyns and hospital claimed that appropriate care was provided and that they were not negligent in failing to consider the diagnosis of a very rare form of cancer.

VERDICT: A $4.69 million New Jersey verdict was returned, with all 3 physicians held partially liable.

Hot speculum burns patient: $547,090 award

A 54-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy performed at a government-operated hospital. After she was anesthetized and unconscious, a second-year resident took a speculum that had been placed in the sterile field by a nurse, and inserted it in the patient's vagina.

When the patient awoke from surgery, she discovered significant burns to her vaginal area, perineum, anus, and buttocks.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The speculum had just been removed from the autoclave and was very hot. The patient incurred substantial medical bills to treat her injuries and was unable to work for several months. She sued the hospital and resident, alleging error by the nurse in placing the hot speculum in the sterile field without cooling it or advising the resident that it was still hot. The resident was blamed for using the speculum without confirming that it was hot.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The resident claimed that she reasonably relied on the nurse to not place a hot instrument in the surgical field without first cooling it. The hospital, representing the nurse, denied fault, blaming the resident for not checking the speculum.

VERDICT: A $547,090 Louisiana verdict was awarded by a judge against the resident and the hospital, but it was halved by comparative fault to $273,545.

Surgeon's breast exam insufficient: $375,000 verdict

After a woman in her early 40s found a lump in her left breast, she underwent a radiographic study, which a radiologist interpreted as showing a 3-mm cyst. Without performing additional tests, a general surgeon immediately scheduled her for surgery.

On May 17, the radiologist performed an ultrasound-guided needle-localized biopsy and found a nodule. The patient was immediately sent to the operating room where the surgeon performed a segmental resection of the nodule.

On May 24, the patient presented to the surgeon's office for a postoperative visit. She told the nurse that the palpable mass was still there. The nurse examined the mass, told the patient that the incision was healing nicely, and suggested follow-up in a month.

Four months later, the patient sought a second opinion. On September 15, she underwent a diagnostic mammogram, ultrasound, and biopsy. The biopsy was positive for invasive ductal carcinoma. On September 30, magnetic resonance imaging and a second biopsy further confirmed the diagnosis. On November 2, she underwent a segmental mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. The pathology report noted a 3-cm invasive ductal carcinoma with necrosis. The patient underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She sued the general surgeon, radiologist, and surgical center, alleging that her breast cancer went undiagnosed. Prior to trial, the radiologist and surgical center were dismissed from the case.

The surgeon failed to perform a thorough physical examination and nodal evaluation of the left breast and axilla. His substandard methods to diagnose and treat the patient's breast cancer delayed proper treatment and significantly altered the outcome.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: The surgeon's treatment met the standard of care. The outcome and treatment were not significantly changed by the delay.

VERDICT: A $375,000 Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Failure to find cancer earlier; patient dies: $4.69M verdict

On July 19, a 26-year-old woman presented to the emergency department (ED) with abnormal vaginal bleeding 3 months after giving birth. She was found to have endometrial thickening and an elevated ß human chorionic gonadotropin level. An ObGyn (Dr. A) assumed that the patient was having a miscarriage and sent her home.

On July 30, when the patient returned to the ED with continued bleeding, lesions on her cervix and urethra were discovered. A second ObGyn, Dr. B, addressed the bleeding, removed the lesion, and ordered testing. On August 17, the patient saw a third ObGyn (Dr. C), who did not conduct an examination.

Days later, the patient suffered a brain hemorrhage that was suspicious for hemorrhagic metastasis. After that, stage IV choriocarcinoma was identified. Although she underwent chemotherapy, the patient died 18 months later.

ESTATE'S CLAIM: All 3 ObGyns failed to take a proper history, conduct adequate examinations, and order appropriate testing. Even at stage IV, 75% of patients with choriocarcinoma survive past 5 years. The stroke rendered chemotherapy less effective and substantially contributed to the patient's death. Failure to diagnose the cancer before the stroke allowed the disease to progress beyond the point at which the patient's life could be saved.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The ObGyns and hospital claimed that appropriate care was provided and that they were not negligent in failing to consider the diagnosis of a very rare form of cancer.

VERDICT: A $4.69 million New Jersey verdict was returned, with all 3 physicians held partially liable.

Hot speculum burns patient: $547,090 award

A 54-year-old woman underwent a hysterectomy performed at a government-operated hospital. After she was anesthetized and unconscious, a second-year resident took a speculum that had been placed in the sterile field by a nurse, and inserted it in the patient's vagina.

When the patient awoke from surgery, she discovered significant burns to her vaginal area, perineum, anus, and buttocks.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: The speculum had just been removed from the autoclave and was very hot. The patient incurred substantial medical bills to treat her injuries and was unable to work for several months. She sued the hospital and resident, alleging error by the nurse in placing the hot speculum in the sterile field without cooling it or advising the resident that it was still hot. The resident was blamed for using the speculum without confirming that it was hot.

DEFENDANTS' DEFENSE: The resident claimed that she reasonably relied on the nurse to not place a hot instrument in the surgical field without first cooling it. The hospital, representing the nurse, denied fault, blaming the resident for not checking the speculum.

VERDICT: A $547,090 Louisiana verdict was awarded by a judge against the resident and the hospital, but it was halved by comparative fault to $273,545.

Surgeon's breast exam insufficient: $375,000 verdict

After a woman in her early 40s found a lump in her left breast, she underwent a radiographic study, which a radiologist interpreted as showing a 3-mm cyst. Without performing additional tests, a general surgeon immediately scheduled her for surgery.

On May 17, the radiologist performed an ultrasound-guided needle-localized biopsy and found a nodule. The patient was immediately sent to the operating room where the surgeon performed a segmental resection of the nodule.

On May 24, the patient presented to the surgeon's office for a postoperative visit. She told the nurse that the palpable mass was still there. The nurse examined the mass, told the patient that the incision was healing nicely, and suggested follow-up in a month.

Four months later, the patient sought a second opinion. On September 15, she underwent a diagnostic mammogram, ultrasound, and biopsy. The biopsy was positive for invasive ductal carcinoma. On September 30, magnetic resonance imaging and a second biopsy further confirmed the diagnosis. On November 2, she underwent a segmental mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy. The pathology report noted a 3-cm invasive ductal carcinoma with necrosis. The patient underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

PATIENT'S CLAIM: She sued the general surgeon, radiologist, and surgical center, alleging that her breast cancer went undiagnosed. Prior to trial, the radiologist and surgical center were dismissed from the case.

The surgeon failed to perform a thorough physical examination and nodal evaluation of the left breast and axilla. His substandard methods to diagnose and treat the patient's breast cancer delayed proper treatment and significantly altered the outcome.

PHYSICIAN'S CLAIM: The surgeon's treatment met the standard of care. The outcome and treatment were not significantly changed by the delay.

VERDICT: A $375,000 Pennsylvania verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Checkpoint inhibition less toxic than antiangiogenic therapy in NSCLC

ORLANDO – , a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests.

In 16,810 patients from 37 trials included in the analysis, first-line treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, compared with first-line sorafenib plus platinum doublets, for example, was associated with less combined direct and indirect toxicity (odds ratios, 0.08 and 0.12, respectively), Chin-Chuan Hung, MD, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

For subsequent therapy, nivolumab showed lower risk than most antiangiogenic therapies, particularly combination ramucirumab and docetaxel (OR, 0.06), said Dr. Hung of China Medical University Hospital in Taichung, Taiwan.

The findings are notable because tolerability is an essential selection criterion for patients with advanced stage disease, and while checkpoint inhibitors – including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and atezolizumab – and antiangiogenic agents – including bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and nintedanib – have become the treatments of choice, direct comparisons with respect to tolerability are lacking, she noted.

The investigators performed a systematic review using Bayesian-model network meta-analysis of studies conducted through July 2017 comparing first-line and subsequent regimens containing chemotherapy, antiangiogenic therapy, and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chemotherapy agents studied included cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed; antiangiogenic agents included bevacizumab, aflibercept, ramucirumab, nintedanib, axitinib, sorafenib, vandetanib, and sunitinib; and immune checkpoint inhibitors included ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab.

Direct and indirect data for all grade 3-5 adverse events were combined using random-effects network meta-analysis.

“The results indicated that [checkpoint] inhibitors can be preferred choices for less toxicity to treat advanced stage NSCLC compared with antiangiogenic therapies in first-line and subsequent settings,” Dr. Hung and her associates concluded.

This study was supported by the China Medical University Beigang Hospital.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Hsu C et al. NCCN poster 13

ORLANDO – , a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests.

In 16,810 patients from 37 trials included in the analysis, first-line treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, compared with first-line sorafenib plus platinum doublets, for example, was associated with less combined direct and indirect toxicity (odds ratios, 0.08 and 0.12, respectively), Chin-Chuan Hung, MD, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

For subsequent therapy, nivolumab showed lower risk than most antiangiogenic therapies, particularly combination ramucirumab and docetaxel (OR, 0.06), said Dr. Hung of China Medical University Hospital in Taichung, Taiwan.

The findings are notable because tolerability is an essential selection criterion for patients with advanced stage disease, and while checkpoint inhibitors – including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and atezolizumab – and antiangiogenic agents – including bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and nintedanib – have become the treatments of choice, direct comparisons with respect to tolerability are lacking, she noted.

The investigators performed a systematic review using Bayesian-model network meta-analysis of studies conducted through July 2017 comparing first-line and subsequent regimens containing chemotherapy, antiangiogenic therapy, and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chemotherapy agents studied included cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed; antiangiogenic agents included bevacizumab, aflibercept, ramucirumab, nintedanib, axitinib, sorafenib, vandetanib, and sunitinib; and immune checkpoint inhibitors included ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab.

Direct and indirect data for all grade 3-5 adverse events were combined using random-effects network meta-analysis.

“The results indicated that [checkpoint] inhibitors can be preferred choices for less toxicity to treat advanced stage NSCLC compared with antiangiogenic therapies in first-line and subsequent settings,” Dr. Hung and her associates concluded.

This study was supported by the China Medical University Beigang Hospital.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Hsu C et al. NCCN poster 13

ORLANDO – , a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests.

In 16,810 patients from 37 trials included in the analysis, first-line treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, compared with first-line sorafenib plus platinum doublets, for example, was associated with less combined direct and indirect toxicity (odds ratios, 0.08 and 0.12, respectively), Chin-Chuan Hung, MD, and her colleagues reported in a poster at the annual conference of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

For subsequent therapy, nivolumab showed lower risk than most antiangiogenic therapies, particularly combination ramucirumab and docetaxel (OR, 0.06), said Dr. Hung of China Medical University Hospital in Taichung, Taiwan.

The findings are notable because tolerability is an essential selection criterion for patients with advanced stage disease, and while checkpoint inhibitors – including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and atezolizumab – and antiangiogenic agents – including bevacizumab, ramucirumab, and nintedanib – have become the treatments of choice, direct comparisons with respect to tolerability are lacking, she noted.

The investigators performed a systematic review using Bayesian-model network meta-analysis of studies conducted through July 2017 comparing first-line and subsequent regimens containing chemotherapy, antiangiogenic therapy, and/or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Chemotherapy agents studied included cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, and pemetrexed; antiangiogenic agents included bevacizumab, aflibercept, ramucirumab, nintedanib, axitinib, sorafenib, vandetanib, and sunitinib; and immune checkpoint inhibitors included ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab.

Direct and indirect data for all grade 3-5 adverse events were combined using random-effects network meta-analysis.

“The results indicated that [checkpoint] inhibitors can be preferred choices for less toxicity to treat advanced stage NSCLC compared with antiangiogenic therapies in first-line and subsequent settings,” Dr. Hung and her associates concluded.

This study was supported by the China Medical University Beigang Hospital.

sworcester@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Hsu C et al. NCCN poster 13

REPORTING FROM THE NCCN ANNUAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Checkpoint blockade appears less toxic than antiangiogenic therapies in advanced NSCLC

Major finding: Less toxicity was seen with first-line nivolumab or pembrolizumab vs. sorafenib + platinum doublets (odds ratios, 0.08 and 0.12, respectively).

Study details: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 37 trials involving 16,810 patients.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the China Medical University Beigang Hospital.

Source: Hsu C et al. NCCN poster 13.

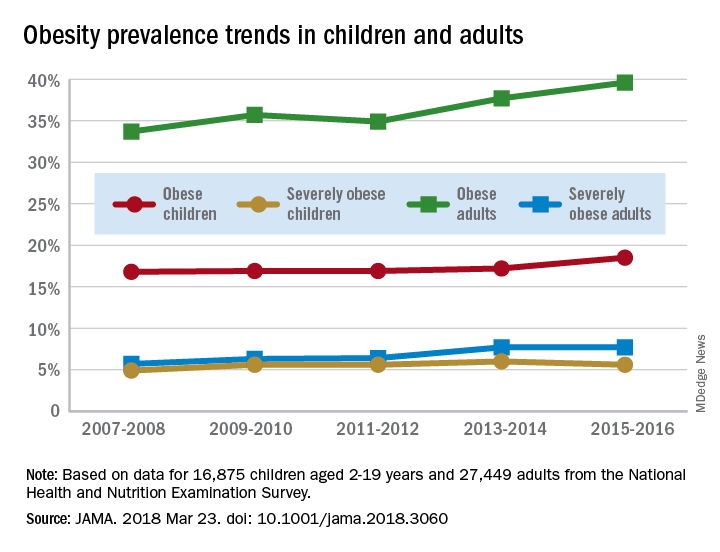

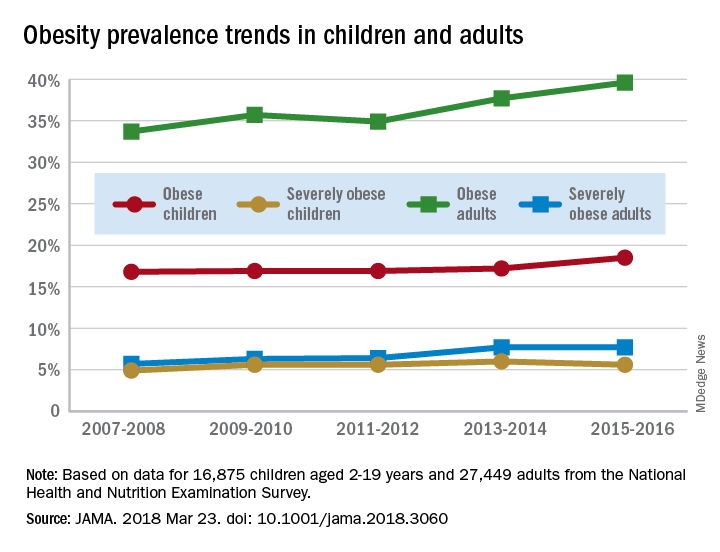

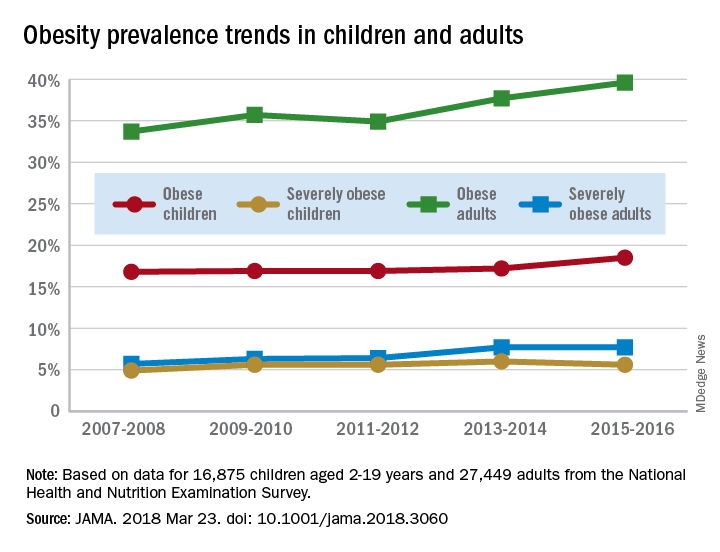

Obesity in adults continues to rise

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

AGA patient education materials can help your patients better understand how to manage and discuss obesity, including lifestyle, pharmacological and endoscopic treatment options. Learn more at www.gastro.org/patientInfo/topic/obesity.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

AGA patient education materials can help your patients better understand how to manage and discuss obesity, including lifestyle, pharmacological and endoscopic treatment options. Learn more at www.gastro.org/patientInfo/topic/obesity.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

AGA patient education materials can help your patients better understand how to manage and discuss obesity, including lifestyle, pharmacological and endoscopic treatment options. Learn more at www.gastro.org/patientInfo/topic/obesity.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

FROM JAMA

Greater Occipital Nerve Block Proves Effective

Greater occipital nerve (GON) block seems to be an effective option for acute management of migraine headache, with promising reductions in pain scores, a recent study found. This retrospective cohort study was undertaken between January 2009 and August 2014 and included patients who underwent at least 1 GON block and attended at least 1 follow-up appointment. Change in the 11-point numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) was used to assess the response to GON block. A total of 562 patients met inclusion criteria; 423 were women (75%); mean age was 58.6 ± 16.7 years. Response was defined as “minimal” (less than 30% NPRS point reduction), “moderate” (31% to 50% NPRS point reduction), or “significant” ( greater than 50% NPRS point reduction). Researchers found:

- Of total patients, 459 (82%) rated their response to GON block as moderate or significant.

- No statistically significant relationship existed between previous treatment regimens and response to GON block.

- GON block was equally effective across the different age and sex groups.

Greater occipital nerve block for acute treatment of migraine headache: A large retrospective cohort study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):211-218. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170188.

Greater occipital nerve (GON) block seems to be an effective option for acute management of migraine headache, with promising reductions in pain scores, a recent study found. This retrospective cohort study was undertaken between January 2009 and August 2014 and included patients who underwent at least 1 GON block and attended at least 1 follow-up appointment. Change in the 11-point numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) was used to assess the response to GON block. A total of 562 patients met inclusion criteria; 423 were women (75%); mean age was 58.6 ± 16.7 years. Response was defined as “minimal” (less than 30% NPRS point reduction), “moderate” (31% to 50% NPRS point reduction), or “significant” ( greater than 50% NPRS point reduction). Researchers found:

- Of total patients, 459 (82%) rated their response to GON block as moderate or significant.

- No statistically significant relationship existed between previous treatment regimens and response to GON block.

- GON block was equally effective across the different age and sex groups.

Greater occipital nerve block for acute treatment of migraine headache: A large retrospective cohort study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):211-218. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170188.

Greater occipital nerve (GON) block seems to be an effective option for acute management of migraine headache, with promising reductions in pain scores, a recent study found. This retrospective cohort study was undertaken between January 2009 and August 2014 and included patients who underwent at least 1 GON block and attended at least 1 follow-up appointment. Change in the 11-point numeric pain rating scale (NPRS) was used to assess the response to GON block. A total of 562 patients met inclusion criteria; 423 were women (75%); mean age was 58.6 ± 16.7 years. Response was defined as “minimal” (less than 30% NPRS point reduction), “moderate” (31% to 50% NPRS point reduction), or “significant” ( greater than 50% NPRS point reduction). Researchers found:

- Of total patients, 459 (82%) rated their response to GON block as moderate or significant.

- No statistically significant relationship existed between previous treatment regimens and response to GON block.

- GON block was equally effective across the different age and sex groups.

Greater occipital nerve block for acute treatment of migraine headache: A large retrospective cohort study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):211-218. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170188.

Brain Diffusion Abnormalities in Children Examined

A recent study identifies early cerebral diffusion changes in children with tension-type and migraine-type headaches compared with controls. The hypothesized mechanisms of nociception in migraine-type and tension-type headaches may explain the findings as a precursor to structural changes seen in adult patients with chronic headache. Patients evaluated for tension-type or migraine-type headache without aura from May 2014 to July 2016 in a single center were retrospectively reviewed. Thirty-two patients with tension-type headache and 23 with migraine-type headache at an average of 4 months after diagnosis were enrolled. All patients underwent diffusion weighted imaging at 3T before the start of pharmacotherapy. Researchers found:

- There were no significant differences in regional brain volumes between the groups.

- Patients with tension-type and migraine-type headaches showed significantly increased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in the hippocampus and brain stem compared with controls.

- Additionally, only patients with migraine-type headache showed significantly increased ADC in the thalamus and a trend toward increased ADC in the amygdala compared with controls.