User login

ACIP vaccine update

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

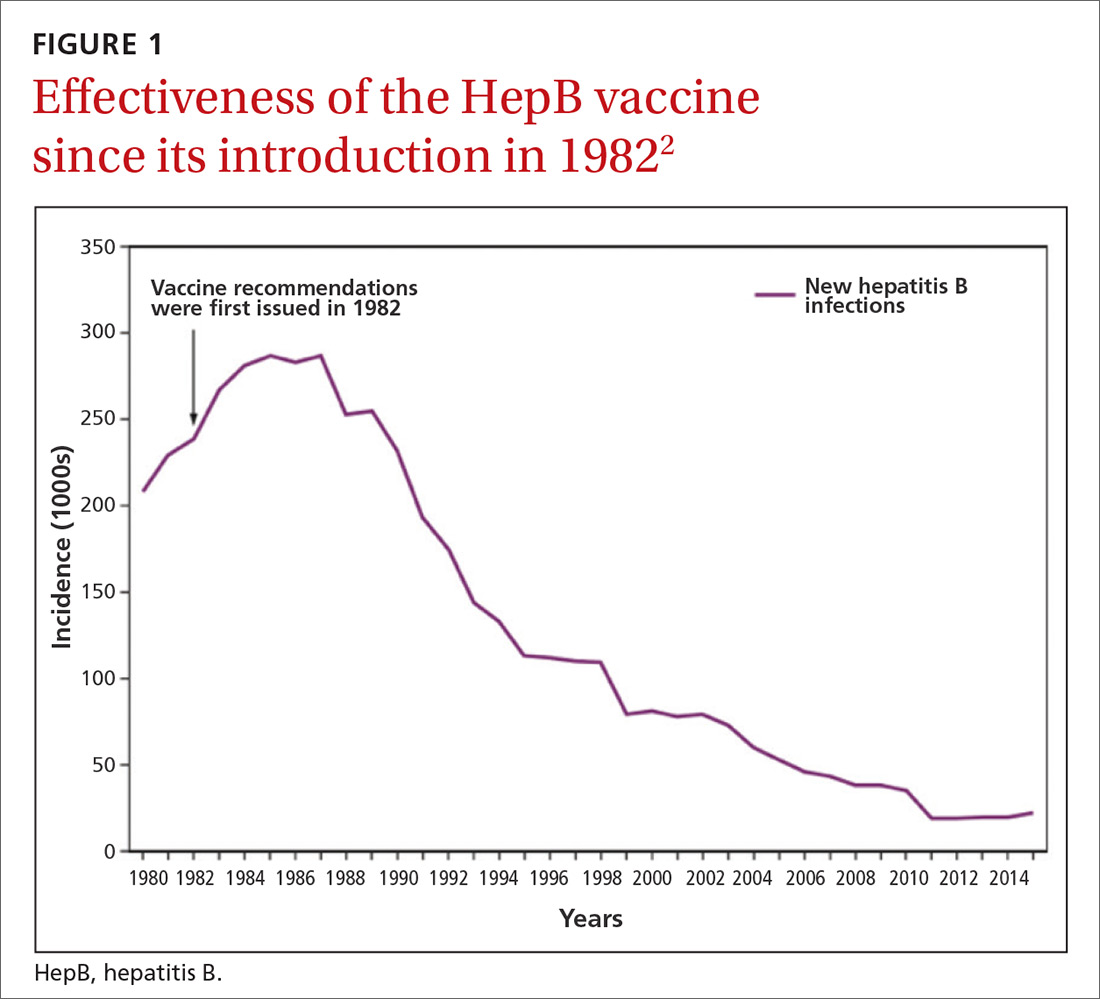

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

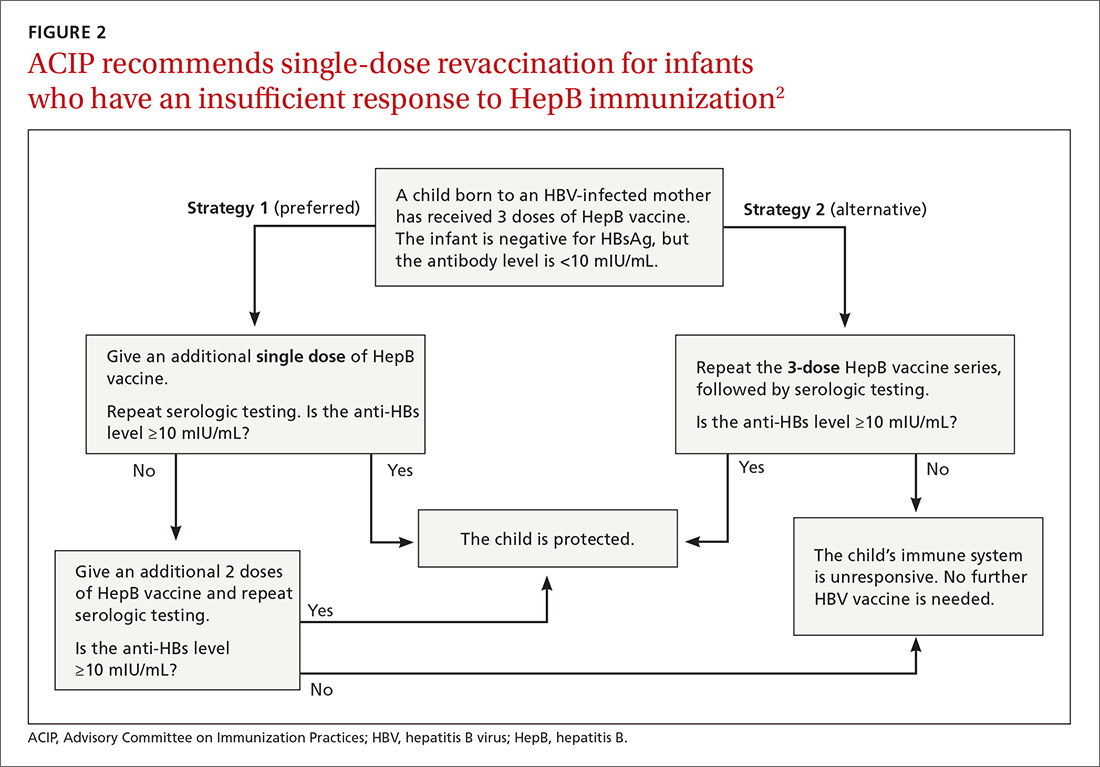

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.

6. Dooling KL. Considerations for the use of herpes zoster vaccines. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/zoster-04-dooling.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

8. Campos-Outcalt D. The new shingles vaccine: what PCPs need to know. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:audio. Available at: https://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/153168/vaccines/new-shingles-vaccine-what-pcps-need-know. Accessed January 19, 2018.

9. Marlow M. Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE): third dose of MMR vaccine. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/mumps-03-marlow-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. HEPLISAV-B [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technology Corporation; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM584762.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018.

11. Janssen R. HEPLISAV-B. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/hepatitis-02-janssen.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) made relatively few new vaccine recommendations in 2017. One pertained to prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in infants born to HBV-infected mothers. Another recommended a new vaccine to prevent shingles. A third advised considering an additional dose of mumps vaccine during an outbreak. This year’s recommendations pertaining to influenza vaccines were covered in a previous Practice Alert.1

Perinatal HBV prevention: New strategy if revaccination is required

Hepatitis B prevention programs in the United States have decreased the incidence of HBV infections from 9.6 cases per 100,000 population in 1982 (the year the hepatitis B [HepB] vaccine was first available) to 1.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 (FIGURE 1).2 One major route of HBV dissemination worldwide is perinatal transmission to infants by HBV-infected mothers. However, this route of infection has been greatly diminished in the United States because of widespread screening of pregnant women and because newborns of mothers with known active HBV infection receive prophylaxis with hepatitis B immune globulin and HBV vaccine.

Each year in the United States an estimated 25,000 infants are born to mothers who are positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg).3 Without post-exposure prophylaxis, 85% of these infants would develop HBV infection if the mother is also hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive; 30% would develop HBV infection if the mother is HBeAg negative.2 Eighty percent to 90% of infected infants develop chronic HBV infection and are at increased risk of chronic liver disease.2 Of all infants receiving the recommended post-exposure prophylaxis, only about 1% develop infection.2

Available HepB vaccines. HepB vaccine consists of HBsAg derived from yeast using recombinant DNA technology, which is then purified by biochemical separation techniques. Three vaccine products are available for newborns and infants in the United States. Two are single-antigen vaccines—Engerix-B (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) and Recombivax HB (Merck & Co.)—and both can be used starting at birth. One combination vaccine, Pediarix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals) is used for children ages 6 weeks to 6 years. It contains HBsAg as do the other 2 vaccines, as well as diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis adsorbed, and inactivated poliovirus (DTaP-HepB-IPV).

Until December 31, 2014, a vaccine combining HBsAg and haemophilus-B antigen, Comvax (Merck and Co.), was available for infants 6 weeks or older. Comvax is no longer produced.

Factors affecting the dosing schedule. For infants born to HBsAg-positive mothers, the final dose of the HepB series should be completed at age 6 months with either one of the monovalent HepB vaccines or the DTaP-HepB-IPV vaccine. When the now-discontinued Comvax was used to complete the series, the final dose was administered at 12 to 15 months. The timing of HepB vaccine at birth and at subsequent intervals, and a decision on whether to give hepatitis B immune globulin, depend on the baby’s birth weight, the mother’s HBsAg status, and type of vaccine used.2

Post-vaccination assessment. ACIP recommends that babies born to HBsAg-positive mothers and having received the final dose of the vaccine series be serologically tested for immunity to HBV at age 9 to 12 months; or if the series is delayed, at one to 2 months after the final dose.4 Infants without evidence of active infection (ie, HBsAg negative) and with levels of antibody to HBsAg ≥10 mIU/mL are considered protected and need no further vaccinations.4 Revaccination is advised for those with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL—who account for only about 2% of infants having received the recommended schedule.4

New revaccination strategy. The previous recommendation on revaccination advised a second 3-dose series with repeat serologic testing one to 2 months after the final dose of vaccine. Although this strategy is still acceptable, the new recommendation for infants with antibody levels <10 mIU/mL favors (for cost savings and convenience) administration of a single dose of HepB vaccine with retesting one to 2 months later.2

Several studies presented at the ACIP meeting in February 2017 showed that more than 90% of infants revaccinated with the single dose will develop a protective antibody level.4 Infants whose anti-HBs remain <10 mIU/mL following the single-dose re-vaccination should receive 2 additional doses of HepB vaccine, followed by testing one to 2 months after the last dose4 (FIGURE 22).

(A new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B [Dynavax Technologies Corp]), has been approved for use in adults. More on this in a bit.)

Herpes zoster vaccine: Data guidance on product selection

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new vaccine against shingles, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit (HZ/su) vaccine, Shingrix (GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals). It is now an alternative to the live attenuated virus (ZVL) vaccine, Zostavax (Merck & Co.), licensed in 2006. ZVL is approved for use in adults ages 50 to 59 years, but ACIP recommends it only for adults 60 and older.5 It is given as a single dose, while HZ/su is given as a 2-dose series at 0 and at 2 to 6 months. By ACIP’s analysis, HZ/su is more effective than ZVL. In a comparison model looking at health outcomes over a lifetime among one million patients 60 to 69 years of age, HZ/su would prevent 53,000 more cases of shingles and 4000 more cases of postherpetic neuralgia than would ZVL.6

Additional mumps vaccine is warranted in an outbreak

While use of mumps-containing vaccine in the United States has led to markedly lower disease incidence rates than existed in the pre-vaccine era, in recent years there have been large mumps outbreaks among young adults at universities and other close-knit communities. These groups have had relatively high rates of completion of 2 doses of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the cause of the outbreaks is not fully understood. Potential contributors include waning immunity following vaccination and antigenic differences between the virus strains circulating and those in the vaccine.

ACIP considered whether a third dose of MMR should be recommended to those fully vaccinated if they are at high risk due to an outbreak. Although the evidence to support the effectiveness of a third dose was scant and of very low quality, the evidence for vaccine safety was reassuring and ACIP voted to recommend the use of a third dose in outbreaks.9

One new vaccine and others on the horizon

ACIP is evaluating a new HepB vaccine, HEPLISAV-B, which was approved by the FDA in November 2017 for use in adults.10,11 The vaccine contains the same antigen as other available HepB vaccines but a different adjuvant. It is administered in 2 doses one month apart, which is preferable to the current 3-dose, 6-month schedule. There is, however, some indication that it causes increased rates of cardiovascular complications.10 ACIP is evaluating the relative effectiveness and safety of HEPLISAV-B and other HepB vaccines, and recommendations are expected this spring.

Other vaccines in various stages of development, but not ready for ACIP evaluation, include those against Zika virus, norovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, and dengue virus.

ACIP is also retrospectively assessing whether adding the 13 valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine to the schedule for those over the age of 65 has led to improved pneumonia outcomes. It will reconsider the previous recommendation based on the results of its assessment.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.

6. Dooling KL. Considerations for the use of herpes zoster vaccines. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/zoster-04-dooling.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

8. Campos-Outcalt D. The new shingles vaccine: what PCPs need to know. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:audio. Available at: https://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/153168/vaccines/new-shingles-vaccine-what-pcps-need-know. Accessed January 19, 2018.

9. Marlow M. Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE): third dose of MMR vaccine. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/mumps-03-marlow-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. HEPLISAV-B [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technology Corporation; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM584762.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018.

11. Janssen R. HEPLISAV-B. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/hepatitis-02-janssen.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. Latest recommendations for the 2017-2018 flu season. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:570-572.

2. Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1-31. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6701a1.htm. Accessed January 19, 2018.

3. CDC. Postvaccination serologic testing results for infants aged ≤24 months exposed to hepatitis B virus at birth: United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:768-771. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6138a4.htm. Accessed February 14, 2018.

4. Nelson N. Revaccination for infants born to hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected mothers. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. February 22, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-02/hepatitis-02-background-nelson.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2017.

5. Hales CM, Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez I, et al. Update on recommendations for use of herpes zoster vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:729-731. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6333a3.htm?s_cid=mm6333a3_w. Accessed January 23, 2018.

6. Dooling KL. Considerations for the use of herpes zoster vaccines. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/zoster-04-dooling.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

7. Dooling KL, Guo A, Patel M, et al. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of herpes zoster vaccines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:103-108.

8. Campos-Outcalt D. The new shingles vaccine: what PCPs need to know. J Fam Pract. 2017;66:audio. Available at: https://www.mdedge.com/jfponline/article/153168/vaccines/new-shingles-vaccine-what-pcps-need-know. Accessed January 19, 2018.

9. Marlow M. Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE): third dose of MMR vaccine. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/mumps-03-marlow-508.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

10. HEPLISAV-B [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technology Corporation; 2017. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM584762.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2018.

11. Janssen R. HEPLISAV-B. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. October 25, 2017; Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2017-10/hepatitis-02-janssen.pdf. Accessed January 19, 2018.

Depigmented plaques on vulva

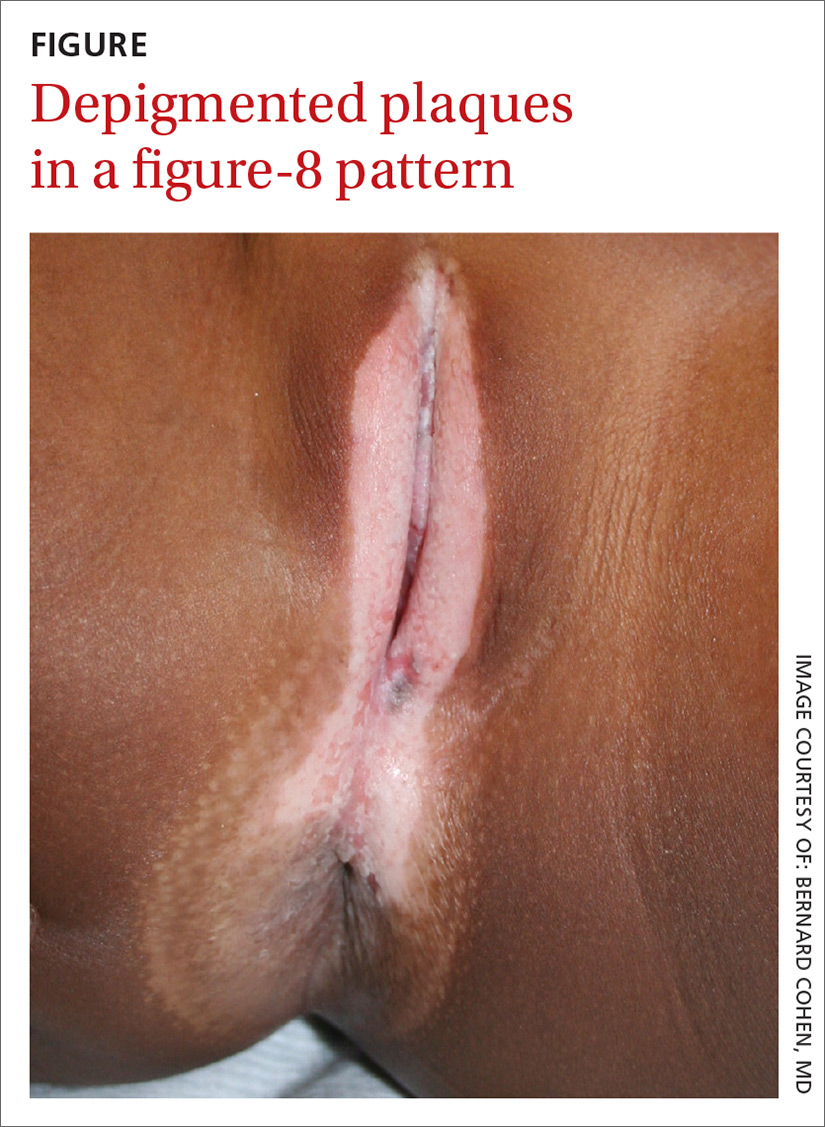

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

A mother brought her 8-year-old daughter to our office for evaluation of vitiligo “down there” (FIGURE). The skin eruption first appeared on her vulva a year earlier and was intermittently pruritic. The lesions were initially smaller and red, but had since lightened in color, coalesced, and had begun to spread to the perianal area. The patient’s mother had received a call from her daughter’s teacher who observed that her daughter was scratching the area and might be masturbating in class.

The mother reported that 6 months earlier, her daughter had experienced bloody spots in her underwear accompanied by dysuria. The mother brought her to the emergency department, where she was treated with antibiotics for a urinary tract infection.

Our physical examination revealed well-circumscribed, symmetric, depigmented, confluent, crinkled, parchment-like plaques with small hemorrhagic erosions on the medial labia majora and minora. The lesions had spread to the perianal area with depigmentation superiorly and hypopigmentation inferiorly, creating a figure-8 pattern.

A review of systems was negative for pruritus, pain, dysuria, dyschezia, constipation, and vaginal discharge. The patient denied sexual activity, depression, or anxiety. Her mother denied behavioral changes in her daughter and said that her daughter hadn’t had any one-on-one time alone with any adults besides herself. Her mother was concerned that the white spots might spread to the rest of her daughter’s body, which could affect her socially.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Lichen sclerosus

Based on the history and clinical findings, including the classic figure-8 pattern, we diagnosed childhood lichen sclerosus (LS) in this patient. LS is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder that primarily affects the genital mucosa. The disorder can present at any age, but is most common among postmenopausal women, with a prevalence estimated to be as high as one in 30.1-3 A second incidence peak is observed in prepubescent girls, with a prevalence of one in 900.3,4 LS is less common in men and boys, with a female-to-male ratio that can reach 10:1.5 The classic symptoms of LS are pruritus and pain, which may be intermittent or persistent.

In girls, initial manifestations may be constipation, dysuria, or even behavioral symptoms such as night fears, which can occur because children are less active at night and become more aware of urinary discomfort.1,2,6 Typical signs of LS are thin atrophic plaques that spare the vagina and cervix. The plaques can be ivory-white, erythematous, or violaceous. Some patients have perianal lesions as well, and can display the pathognomonic figure-8 pattern of porcelain plaques around the vulva and anus.5

With more advanced disease, erosions, lichenification, and even distortion of vulvar architecture may occur.2,4,7 In severe cases, labia resorption and clitoral phimosis may develop.5 Complications include secondary infection, dyspareunia, and psychosexual distress. The most worrisome sequela of LS is squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva (SCCV), which occurs in 5% of female patients with LS.4

In men and boys, LS typically involves the foreskin and the glans, while sparing the perianal region.5 Scarring of the foreskin can lead to phimosis, and patients may complain of painful erections and difficulty urinating. LS can also occur away from the genitalia in both males and females.

Autoimmune mechanisms, genetics, and hormones play a role

The exact pathogenesis of LS remains unknown, but multiple factors are likely at work.

Autoimmune mechanisms. Up to 60% of women with LS have an autoimmune disorder, which is most commonly vitiligo, alopecia areata, or thyroid disease.5 In addition, 67% of patients have autoantibodies against extracellular matrix protein 1, and 30% have them against bullous pemphigoid antigen 180.1,8

Genetics. LS is associated with certain human leukocyte antigen class II haplotypes (especially DQ7) and with polymorphisms at the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist gene locus.5,6,9

Hormones. The clear peaks of incidence during times of low estrogen, and a higher incidence in patients with Turner syndrome or kidney disease, suggest that low estrogen may play a role in the development of LS, as well.1,5,6

While it is generally accepted that trauma may trigger LS via the Koebner phenomenon (the appearance of lesions at the site of injury), there is debate as to whether microbes—especially Borrelia burgdorferi and human papillomavirus (HPV)—might play a role.1,5

Diagnosis is often delayed, misdiagnosis is common

The average delay from symptom onset to diagnosis of LS is 1.3 years, and up to 84% of childhood LS is misdiagnosed before referral.2,9 The differential diagnosis includes:

Sexual abuse. In prepubertal girls presenting with genital redness, the can’t-miss diagnosis is sexual abuse, which occurs in more than 25% of children in the United States.10 Initial manifestations may be regression in developmental milestones, such as new-onset bedwetting, or behavioral changes such as social withdrawal or declining academic performance.11

However, physicians must be conscientious about ruling out medical etiologies before prematurely diagnosing abuse. Fourteen percent of girls with LS are incorrectly diagnosed as having been sexually abused.2 A clinical pearl is that while LS may resemble abuse on exam, it rarely affects the hymenal structure.12 It is also important to keep in mind that the 2 entities are not incompatible, as sexual abuse leading to LS via Koebnerization is a well-described phenomenon.12

Lichen planus. LP, which is also an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder affecting the vulva, classically presents with the 6 Ps: pruritic, polygonal, planar, purple papules and plaques.4 LP is distinguished from LS by being rare in childhood, having a predilection for the flexor wrists, and involving the oral and vaginal mucosa.4

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is a chronic, circumscribed, pruritic, eczematous condition that becomes lichenified with thickened skin secondary to repeated scratching.13 Children with atopic dermatitis can develop LSC, but other children can also develop the scratch-itch cycle that results in the thickened plaques of LSC. Like LS, LSC can occur in areas other than the genitalia, including the neck and feet.14

Allergic contact dermatitis can occur in the genital area from diaper creams, soaps, and perfumes. Irritant contact dermatitis can occur from exposure to diarrhea, bedwetting, and other irritants. Contact dermatitis is less likely to have the classic figure-8 pattern seen in LS.

Psoriasis in the genital area can be confused with LS. However, psoriasis favors the groin creases in what is called inverse psoriasis. In addition, psoriasis tends to involve multiple areas, including the extensor surfaces of the elbows and knees, the nails, and the scalp.

Vitiligo can present on the genitals as circumscribed hypopigmented and depigmented patches that are flat. Vitiligo is asymptomatic, and the only pathology is the change in skin color. With LS, there is lichenification, atrophy, and sclerosis.4 Vitiligo often occurs with bilateral symmetric involvement in areas of trauma including the face, neck, scalp, elbows, wrists, hands, knees, ankles, and feet.

Treatment aims to improve symptoms

LS is usually diagnosed clinically (especially in children, as a biopsy is a great challenge to perform). However, when the clinical presentation is unclear, a skin biopsy will demonstrate the diagnostic findings of thinning of the epidermis, loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratosis, and dermal fibrosis with a T-lymphocyte-dominant inflammatory infiltrate.1,2,4,5

LS is a remitting and relapsing condition with no cure. The goals of treatment are to provide symptom relief and minimize scarring and atrophy,2 but it is unknown whether treatment reduces the risk of malignancy.9

First-line treatment for both genders and all ages is ultrapotent topical corticosteroids; clobetasol propionate 0.05% is most commonly used.1,6 Regimens vary, but the vast majority of patients improve within 3 months of once-daily treatment.4

For refractory LS, calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus may be used. Although it has a black box warning regarding a potential cancer risk, long-term studies of children using tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis have not demonstrated an increased risk of malignancy.6,9 Because of a considerable adverse effect profile, oral retinoids are limited to refractory cases in adults.6 Surgery is reserved for scarring and adhesions.4

Follow-up plays an important role in management

Historically, it was believed that pediatric LS had an excellent prognosis, with patients achieving complete resolution after puberty.1,4 Recent findings have shown mixed results, with LS persisting in many patients beyond puberty.2,4 Therefore, regular follow-up is recommended every 6 to 12 months.

For uncomplicated LS, specialist follow-up is not indicated. Female patients should regularly conduct self-examinations and, at a minimum, undergo annual examinations by their primary care physician. Those who require specialist follow-up include patients with difficult-to-control symptoms, hypertrophic lesions, a history of SCCV or differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (dVIN), or pathology showing possible dVIN.15

Our patient. We prescribed clobetasol propionate 0.05% ointment to be used once daily for 8 weeks. We stressed the importance of genital self-examinations using a mirror to monitor for any concerning changes such as skin thickening. We showed the patient and her mother photos of normal female genitalia to help normalize the genital exam, and taught the patient how to find her plaques in the mirror. We set expectations by emphasizing the chronic nature of LS and the likelihood of recurrence. We also encouraged HPV vaccination in the upcoming years to prevent both cervical cancer and HPV-related SCCV.

CORRESPONDENCE

Somya Abubucker, MD, University of Hawaii, 1356 Lusitana Street, 7th floor, Honolulu, HI 96813; sabubuck@hawaii.edu.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

1. Murphy R. Lichen sclerosus. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:707-715.

2. Dendrinos ML, Quint EH. Lichen sclerosus in children and adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25:370-374.

3. Eva LJ. Screening and follow up of vulval skin disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;26:175-188.

4. Focseneanu MA, Gupta M, Squires KC, et al. The course of lichen sclerosus diagnosed prior to puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:153-155.

5. Funaro D. Lichen sclerosus: a review and practical approach. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:28-37.

6. Heymann WR. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:683-684.

7. Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

8. Lagerstedt M, Karvinen K, Joki-Erkkilä M, et al. Childhood lichen sclerosus—a challenge for clinicians. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:444-450.

9. Keith PJ, Wolz MM, Peters MS. Eosinophils in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:693-698.

10. National Sexual Violence Resource Center. Child sexual abuse prevention. 2011. Available at: https://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/Publications_NSVRC_Overview_Child-sexual-abuse-prevention_0.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

11. Dubowitz H, Lane WG. Abused and neglected children. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:236-249.

12. Powell J, Wojnarowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: an increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:803-806.

13. Reamy BV, Bunt CW, Fletcher S. A diagnostic approach to pruritus. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:195-202.

14. Warshaw E, Hook K. Dermatitis. In: Soutor C, Hordinsky MK, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

15. Jones RW, Scurry J, Neill S, et al. Guidelines for the follow-up of women with vulvar lichen sclerosus in specialist clinics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:496.e1-e3.

Does exercise relieve vasomotor menopausal symptoms?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 733 patients examined the effectiveness of any type of exercise in decreasing vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The studies compared exercise—defined as structured exercise or physical activity through active living—with no active treatment, yoga, or hormone therapy (HT) over a 3- to 24-month follow-up period.

Three trials of 454 women that compared exercise with no active treatment found no difference between groups in frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms (standard mean difference [SMD]= -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.33 to 0.13).

Two trials with 279 women that compared exercise with yoga didn’t find a difference in reported frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms between the groups (SMD= -0.03; 95% CI, -0.45 to 0.38).

One small trial (14 women) of exercise and HT found that HT patients reported decreased frequency of flushes over 24 hours compared with the exercise group (mean difference [MD]=5.8; 95% CI, 3.17-8.43).

Overall, the evidence was of low quality because of heterogeneity in study design.1

Two exercise interventions fail to reduce symptoms

A 2014 RCT, published after the Cochrane search date, investigated exercise as a treatment for VMS in 261 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women ages 48 to 57 years.2 Patients had a history of at least 5 hot flashes or night sweats per day and hadn’t taken HT in the previous 3 months.

The women were randomized to one of 2 exercise interventions or a control group. The exercise interventions both entailed 2 one-on-one consultations with a physical activity facilitator and use of a pedometer. Patients were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 3 days a week during Weeks 1 through 12, then increase the frequency to 3 to 5 days a week during Weeks 13 through 24. In one intervention arm, the women also received an informational DVD and 5 educational leaflets.

In the other arm, they were invited to attend 3 exercise support groups in their local community. The control group was offered an opportunity for exercise consultation and given a pedometer at the end of the study.

At the end of the 6-month intervention, neither exercise intervention significantly decreased self-reported hot flashes/night sweats per week compared with the control group (DVD exercise arm vs control: MD= -8.9; 95% CI, -20 to 2.2; social support exercise arm vs control: MD= -5.2; 95% CI, -16.7 to 6.3). The study also found no difference in hot flashes/night sweats per week at 12-month follow-up between the DVD exercise arm and controls (MD= -3.2; 95% CI, -12.7 to 6.4) and the social-support group and controls (MD= -3.5; 95% CI, -13.2 to 6.1).

Drug therapy relieves symptoms, but other methods—not so much

An analysis of pooled individual data from 3 RCTs compared exercise with 5 other interventions for VMS in 899 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 Patients had at least 14 bothersome symptoms per week.

The 6 interventions ranged from nonpharmacologic therapies, such as aerobic exercise and yoga, to pharmacologic treatments, including escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/d, venlafaxine 75 mg/d, oral estradiol (E2) 0.5 mg/d, and omega-3 supplementation 1.8 g/d. The primary outcome was a change in VMS frequency and bother as assessed by a symptom diary over the 4- to 12-week follow-up.

The analysis found a significant 6-week reduction in daily VMS frequency relative to placebo for escitalopram (MD= -1.4; 95% CI, -2.7 to -0.2), low-dose E2 (MD= -1.9; 95% CI, -2.9 to -0.9), and venlafaxine (MD= -1.3; 95% CI, -2.3 to -0.3). However, no difference in VMS frequency or bother was found with exercise (MD= -0.4; 95% CI, -1.1 to 0.3), yoga (MD= -0.6; 95% CI, -1.3 to 0.1), or omega-3 supplementation (MD= 0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) doesn’t offer specific recommendations regarding exercise as a treatment for symptoms of menopause. The 2014 ACOG guidelines for managing symptoms report that data don’t support phytoestrogens, supplements, or lifestyle modifications (Level B, based on limited or inconsistent evidence). ACOG recommends basic palliative measures such as drinking cool drinks and decreasing layers of clothing (Level B).4

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ recommendations don’t mention exercise as a menopause therapy.5

The North American Menopause Society’s 2015 statement regarding the nonhormonal treatment of menopause symptoms doesn’t recommend exercise as an effective therapy because of insufficient or inconclusive data.6

1. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Thomas A, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD006108.

2. Daley AJ, Thomas A, Roalfe AK, et al. The effectiveness of exercise as treatment for vasomotor menopausal symptoms: randomized controlled trial. BJOG. 2015;122:565-575.

3. Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Ensrud KE, et al. Pooled analysis of six pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:413-422.

4. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

5. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Ginzburg SB, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:949-954.

6. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:1155-1172.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 733 patients examined the effectiveness of any type of exercise in decreasing vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The studies compared exercise—defined as structured exercise or physical activity through active living—with no active treatment, yoga, or hormone therapy (HT) over a 3- to 24-month follow-up period.

Three trials of 454 women that compared exercise with no active treatment found no difference between groups in frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms (standard mean difference [SMD]= -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.33 to 0.13).

Two trials with 279 women that compared exercise with yoga didn’t find a difference in reported frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms between the groups (SMD= -0.03; 95% CI, -0.45 to 0.38).

One small trial (14 women) of exercise and HT found that HT patients reported decreased frequency of flushes over 24 hours compared with the exercise group (mean difference [MD]=5.8; 95% CI, 3.17-8.43).

Overall, the evidence was of low quality because of heterogeneity in study design.1

Two exercise interventions fail to reduce symptoms

A 2014 RCT, published after the Cochrane search date, investigated exercise as a treatment for VMS in 261 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women ages 48 to 57 years.2 Patients had a history of at least 5 hot flashes or night sweats per day and hadn’t taken HT in the previous 3 months.

The women were randomized to one of 2 exercise interventions or a control group. The exercise interventions both entailed 2 one-on-one consultations with a physical activity facilitator and use of a pedometer. Patients were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 3 days a week during Weeks 1 through 12, then increase the frequency to 3 to 5 days a week during Weeks 13 through 24. In one intervention arm, the women also received an informational DVD and 5 educational leaflets.

In the other arm, they were invited to attend 3 exercise support groups in their local community. The control group was offered an opportunity for exercise consultation and given a pedometer at the end of the study.

At the end of the 6-month intervention, neither exercise intervention significantly decreased self-reported hot flashes/night sweats per week compared with the control group (DVD exercise arm vs control: MD= -8.9; 95% CI, -20 to 2.2; social support exercise arm vs control: MD= -5.2; 95% CI, -16.7 to 6.3). The study also found no difference in hot flashes/night sweats per week at 12-month follow-up between the DVD exercise arm and controls (MD= -3.2; 95% CI, -12.7 to 6.4) and the social-support group and controls (MD= -3.5; 95% CI, -13.2 to 6.1).

Drug therapy relieves symptoms, but other methods—not so much

An analysis of pooled individual data from 3 RCTs compared exercise with 5 other interventions for VMS in 899 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 Patients had at least 14 bothersome symptoms per week.

The 6 interventions ranged from nonpharmacologic therapies, such as aerobic exercise and yoga, to pharmacologic treatments, including escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/d, venlafaxine 75 mg/d, oral estradiol (E2) 0.5 mg/d, and omega-3 supplementation 1.8 g/d. The primary outcome was a change in VMS frequency and bother as assessed by a symptom diary over the 4- to 12-week follow-up.

The analysis found a significant 6-week reduction in daily VMS frequency relative to placebo for escitalopram (MD= -1.4; 95% CI, -2.7 to -0.2), low-dose E2 (MD= -1.9; 95% CI, -2.9 to -0.9), and venlafaxine (MD= -1.3; 95% CI, -2.3 to -0.3). However, no difference in VMS frequency or bother was found with exercise (MD= -0.4; 95% CI, -1.1 to 0.3), yoga (MD= -0.6; 95% CI, -1.3 to 0.1), or omega-3 supplementation (MD= 0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) doesn’t offer specific recommendations regarding exercise as a treatment for symptoms of menopause. The 2014 ACOG guidelines for managing symptoms report that data don’t support phytoestrogens, supplements, or lifestyle modifications (Level B, based on limited or inconsistent evidence). ACOG recommends basic palliative measures such as drinking cool drinks and decreasing layers of clothing (Level B).4

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ recommendations don’t mention exercise as a menopause therapy.5

The North American Menopause Society’s 2015 statement regarding the nonhormonal treatment of menopause symptoms doesn’t recommend exercise as an effective therapy because of insufficient or inconclusive data.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY