User login

ACL injury: How do the physical examination tests compare?

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

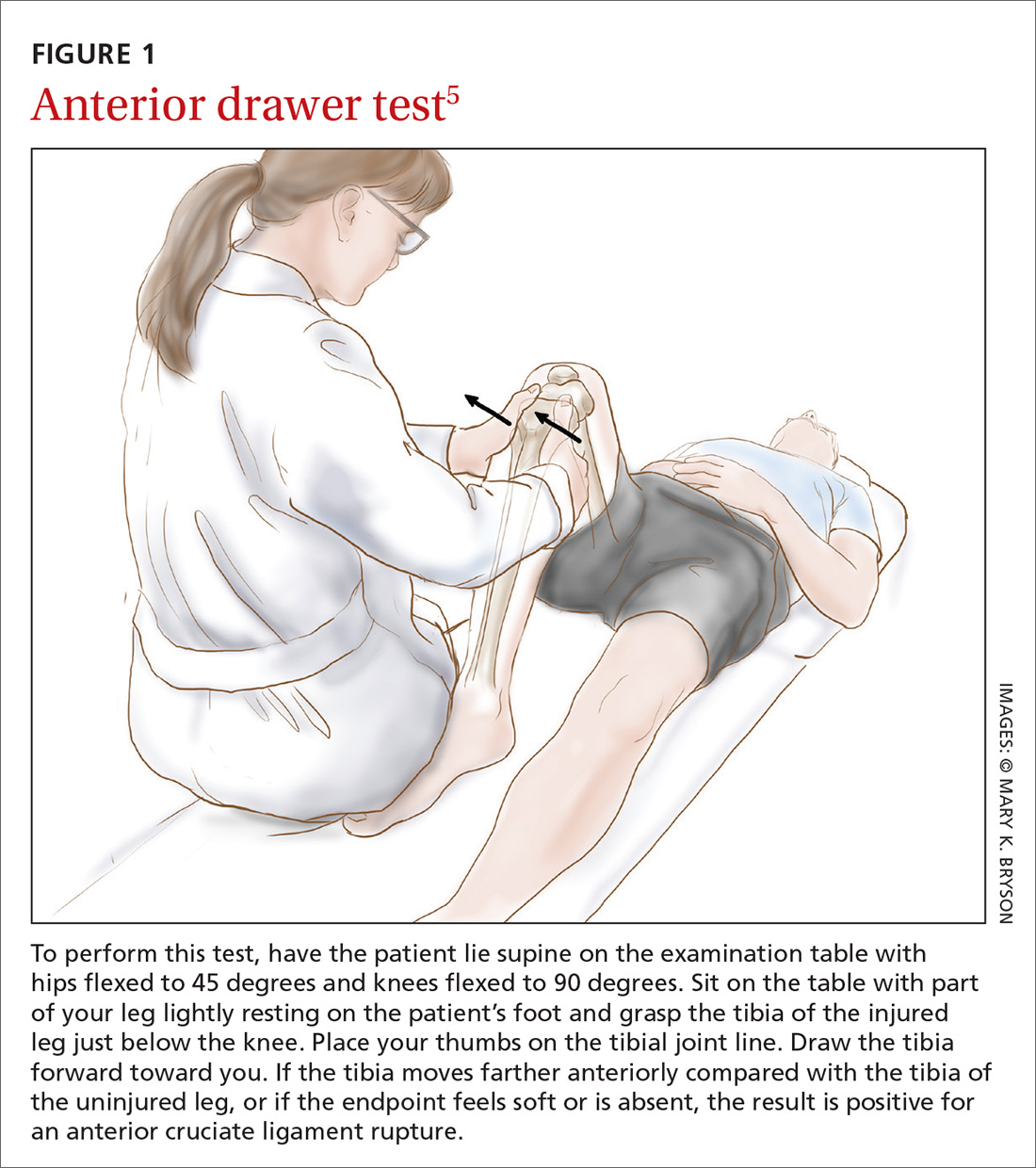

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

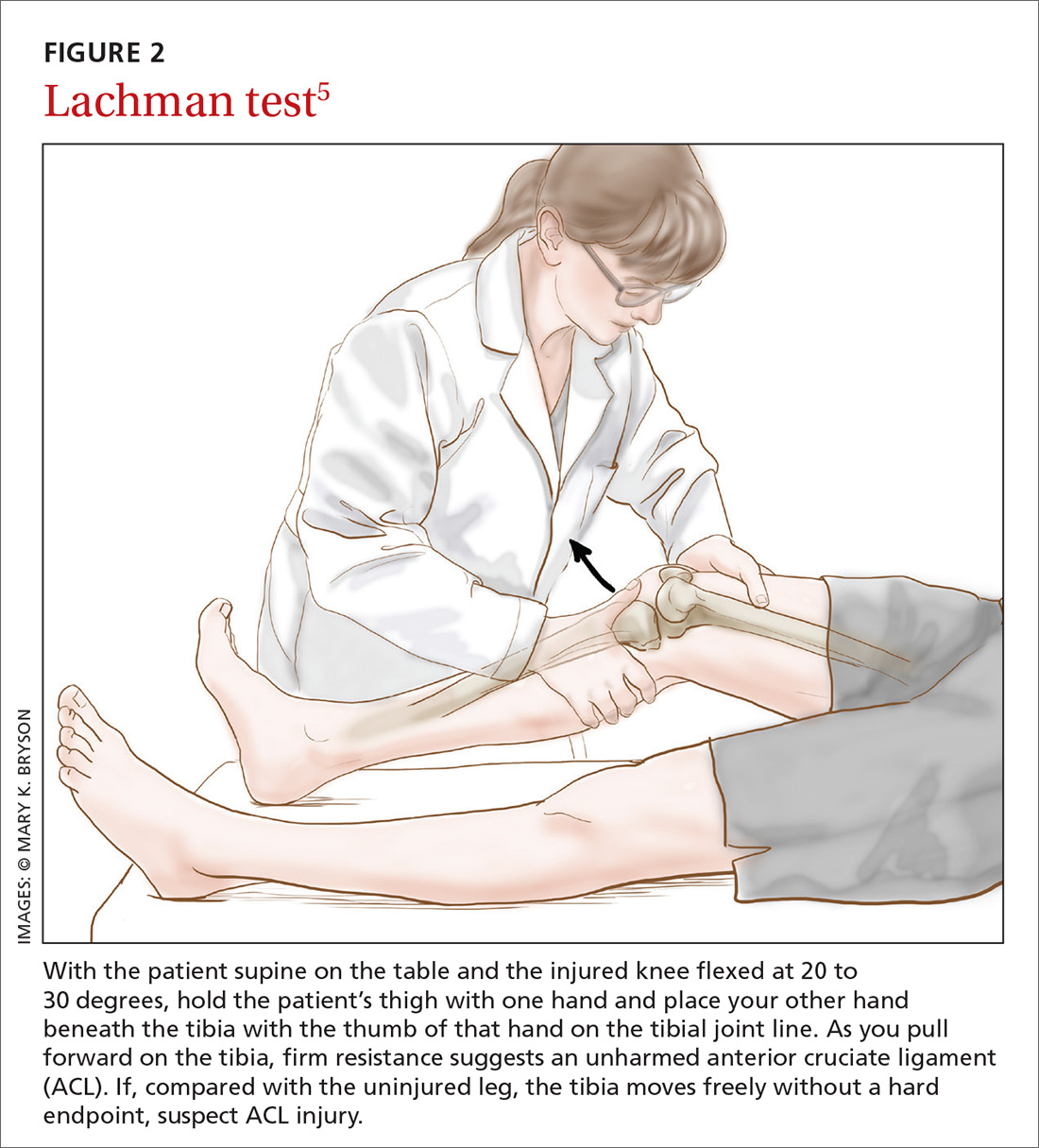

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

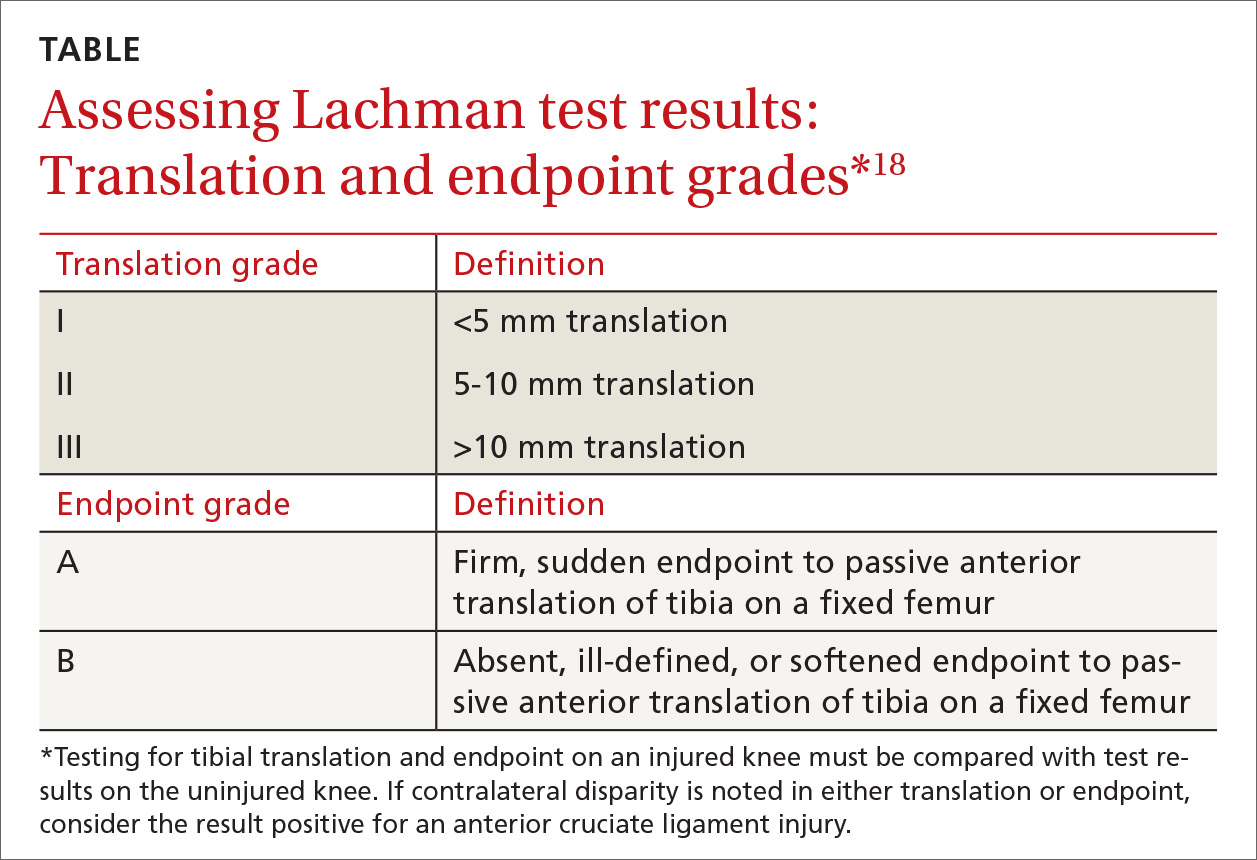

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

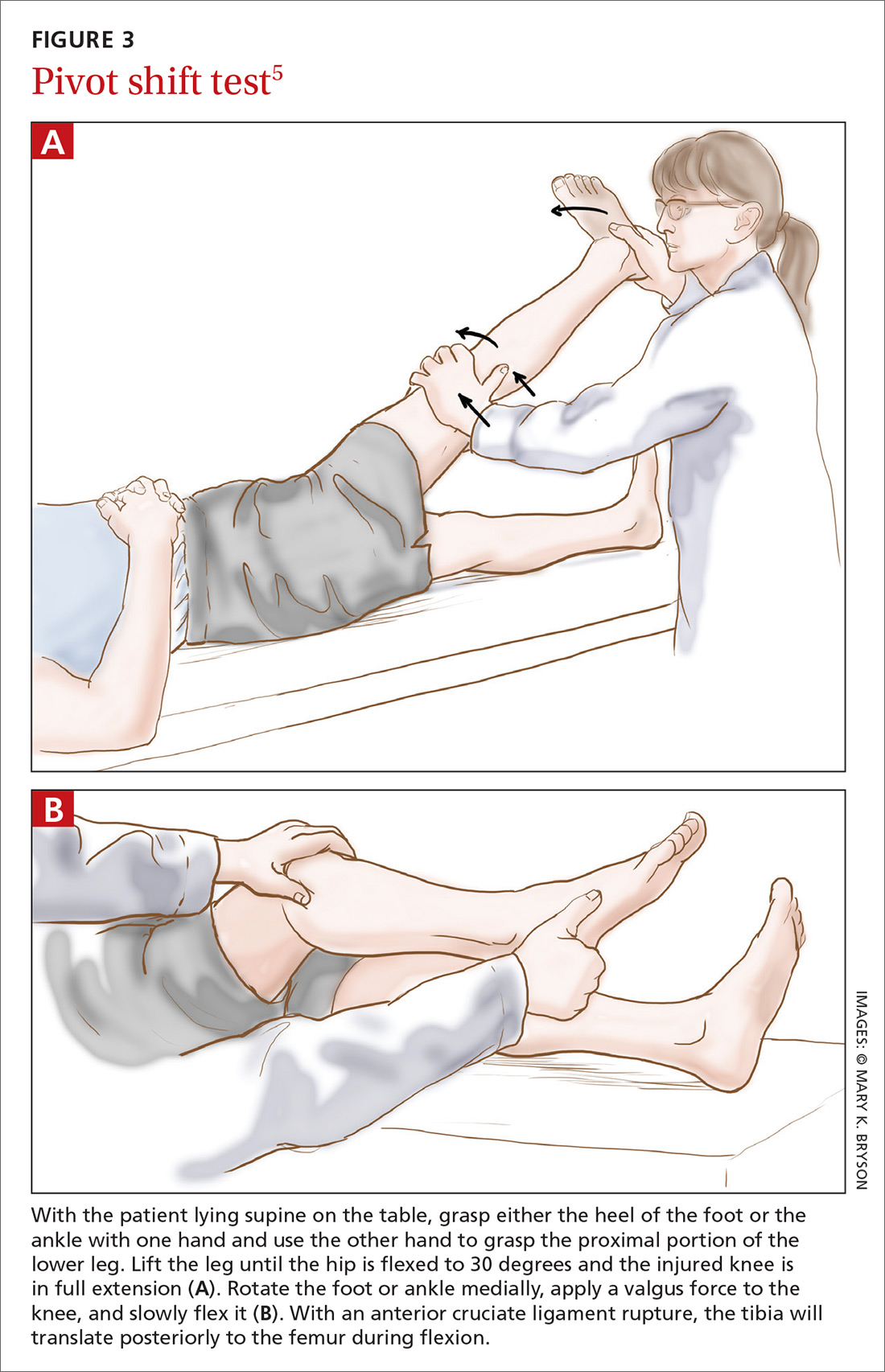

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

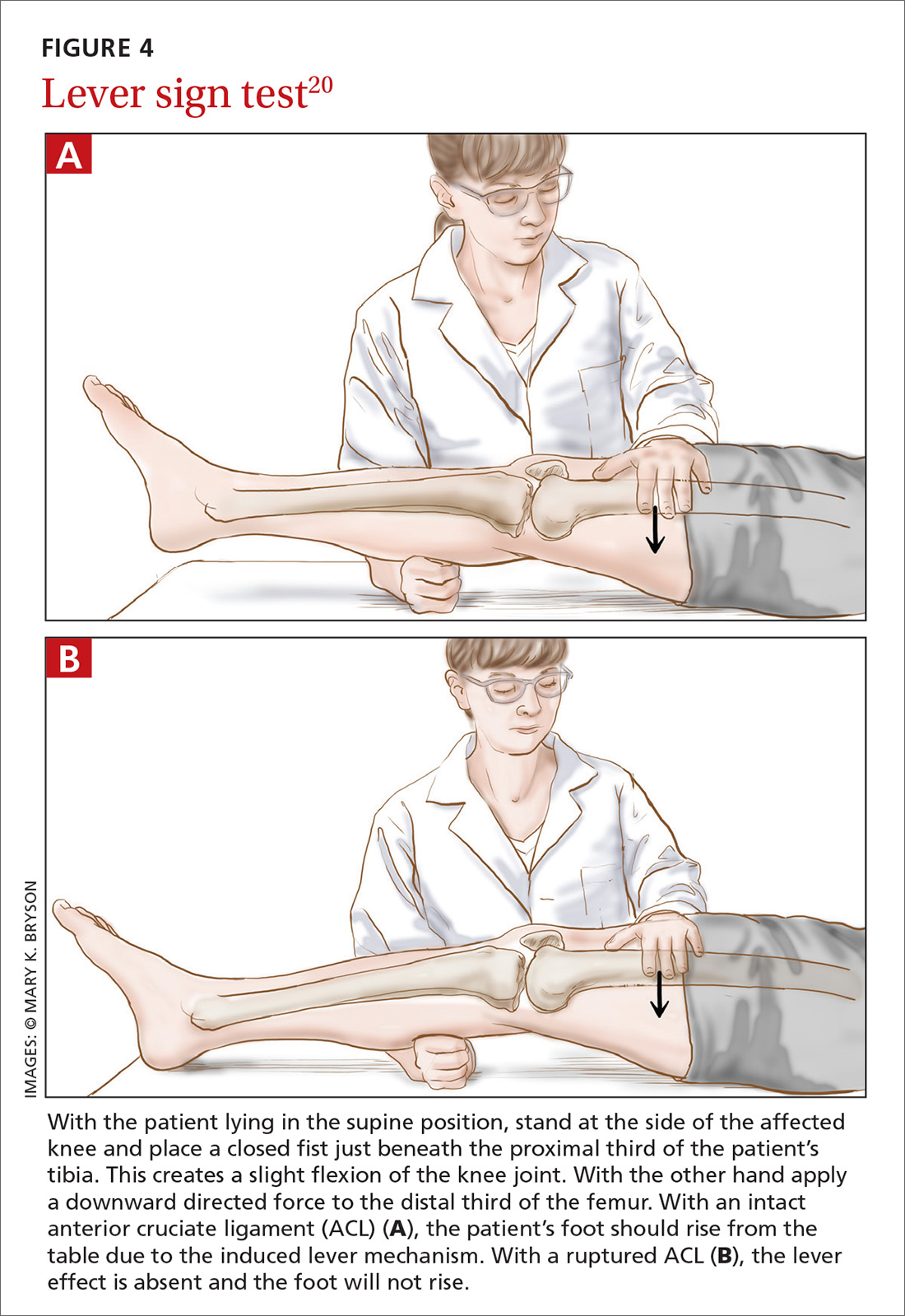

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; c.koster@vumc.nl.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; c.koster@vumc.nl.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

CASE An athletic 25-year-old woman presents to her family physician complaining of a painful and swollen knee. She says that she injured the knee the day before during a judo match. The injury occurred when her upper body suddenly changed direction while her foot remained planted and her knee rotated medially. A cruciate ligament injury immediately comes to mind, but other potential diagnoses include meniscal injury, collateral ligament injury, and patellar instability. The first step in determining an accurate diagnosis is to evaluate the stability of the knee by physical examination—often a difficult task immediately following an injury.

How would you proceed?

Rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), partial or complete, is a common injury, especially in athletes who hurt their knee in a pivoting movement.1 The number of patients who present with ACL injury is estimated at 252,000 per year.2 Cruciate ligament injury may lead to complaints of instability with subsequent inability to engage in sports activities. Cruciate ligament injury is also associated with premature development of osteoarthritis later in life.3 Operative treatment seems to be superior to conservative treatment in improving both subjective and objective measures of knee instability and in helping athletes return to their former level of activity.4

Because early detection is key to achieving the best clinical outcome, it is essential that the most accurate physical examination tests are performed during the acute phase. Primary care physicians, emergency room doctors, physical therapists, and athletic trainers are the ones who most often see these patients immediately following the injury, and they often have only the physical examination with which to assess ACL injury. Their task is to identify the patient with potential ACL injury and to refer the patient swiftly.

Three physical examination tests are most commonly used to evaluate cruciate ligament injury. The best known and most frequently used technique is the anterior drawer test. The other 2 tests, the Lachman test and the pivot shift test, are more difficult to perform and are used less often, especially by physicians untrained in their use. In addition, there is a relatively new diagnostic test: the lever sign test. The aim of our article is to provide a short, clinically relevant overview of the literature and to assess the diagnostic value of physical examination for the primary care physician.

Anterior drawer test

How it’s done. In this test, the patient lies supine on the examination table with hips flexed to 45 degrees and knees flexed to 90 degrees (FIGURE 1).5 The examiner sits on the table with a leg resting on the patient's foot, grasps the tibia of the injured leg just below the knee, and draws the tibia forward. If the tibia, compared with the tibia of the uninjured leg, moves farther anteriorly, or if the endpoint feels softened or is absent, the result is positive for an ACL injury.

The literature. Nine systematic reviews conclude that the anterior drawer test is inferior to the Lachman test,6-14 which we’ll describe in a moment. This is due, in part, to the anterior drawer test’s unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity in the clinical setting—especially during the acute phase.10 The most recent meta-analysis on the anterior drawer test reports a sensitivity of 38% and a specificity of 81%.9 In other words, out of 100 ruptured ligaments, only 38 will test positive with the anterior drawer test.

The literature offers possible explanations for findings on the test’s validity. First, rupture of the ACL is often accompanied by swelling of the knee caused by hemarthrosis and reactive synovitis that can prevent the patient from flexing the knee to 90 degrees. Second, the joint pain may induce a protective muscle action, also called guarding of the hamstrings, that creates a vector opposing the passive anterior translation.15

Apart from the matter of a test’s validity, it's also important to consider the test’s inter- and intra-rater reliability.16 Compared with the Lachman test, the anterior drawer test is inferior in reliability.7

Lachman test

How it’s done. The Lachman test is performed with the patient supine on the table and the injured knee flexed at 20 to 30 degrees (FIGURE 2).5 The examiner holds the patient’s thigh with one hand and places the other hand beneath the tibia with the thumb of that hand on the tibial joint line. As the tibia is pulled forward, firm resistance suggests an uninjured ACL. Free movement without a hard endpoint, compared with the uninjured knee, indicates ACL injury.

The literature. The Lachman test is the most accurate of the 3 diagnostic physical procedures. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 68% for partial ruptures and 96% for complete ACL ruptures.6 According to a recently published overview of systematic reviews, the Lachman test has high diagnostic value in confirming or ruling out an ACL injury.17

Two factors are important when assessing results of the Lachman test. The quantity of anterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur is as important as the quality of the endpoint of the anterior translation. Quantity of translation must always be compared with the unaffected knee. Quality of the endpoint in passive anterior translation should be assessed as “firm” or “sudden,” indicating an intact ACL, or as “absent, ill-defined, or softened,” indicating ACL pathology (TABLE).18

A drawback of the Lachman test is that it is challenging to perform correctly.19 The patient’s ability to relax the upper leg musculature is critically important. It is also essential to stabilize the distal femur, which can be problematic if the examiner has small hands relative to the size of the patient's leg musculature.10 These difficulties might be resolved by conducting the Lachman test with the patient in the prone position, known as the Prone Lachman.19 However, good evidence is not yet available to support this proposed solution. One systematic review, though, reports that the Prone Lachman test has the highest inter-rater reliability of all commonly used physical examination tests.7

The Lachman test is known as the test with highest validity on physical examination. When the outcome of a correctly performed Lachman test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is very unlikely.

Pivot shift test

How it’s done.

The literature. The pivot shift test is technically more challenging to perform than the other 2 tests and is, therefore, less practical in the primary care setting. However, when this test is done correctly, a positive result is highly specific for ACL injury.9,10 Reported sensitivity values are contradictory. The most recent meta-analysis reports a sensitivity of 85%.6 Two other studies cite much lower values: 24% and 28%.9,10 These data suggest that the pivot shift test, when carried out correctly, can be of use in confirming a possible ACL rupture. However, the test should not be used alone in ruling out a possible ACL injury.

New diagnostic test: Lever sign test

How it’s done. The lever sign test (FIGURE 4),20 introduced in the mid-2010s, is also performed with the patient lying in the supine position. The examiner stands at the side of the affected knee of the patient, places a closed fist just beneath the proximal third of the patient’s tibia, creating a slight flexion of the knee joint. With the other hand, the examiner applies a downward directed force to the distal third of the femur. With an intact ACL, the patient’s foot should rise from the table due to the induced lever mechanism. With a ruptured ACL, the lever effect is absent and the foot will not rise.

The literature. In the prospective clinical study that introduced the lever sign test, the sensitivity rate was reported at 100%—higher than that seen with the other commonly used tests.20 Another study has reported that the lever sign test was easily adopted in clinical practice and showed higher sensitivity than the Lachman test (94% vs 80% in pre-anesthesia assessment).21 However, a more recent study has shown a sensitivity of 77% for the lever sign.22 The lever sign test is relatively easy to perform and requires less examiner strength than does the Lachman test. These factors enhance applicability of the lever sign test in the primary care office and in other settings such as physical therapy centers and emergency departments.

Applying this information in primary care

Given the importance of physical examination in diagnosing ACL injury, how can the current evidence best be applied in primary care practice? Based on its good test properties and feasibility, the Lachman test is preferred in primary care. The anterior drawer test can be used, but its low accuracy must be considered in making an assessment. The pivot shift test, given its difficulty of execution, should not be used by physicians unacquainted with it.

If future research supports early reports of the lever sign test’s accuracy, it could be very helpful in family practice. Going forward, research should aim at developing a constructive strategy for applying these physical examination tests in both primary care and specialty settings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christiaan H. Koster, Department of Trauma Surgery, VU University Medical Centre, P.O. Box 7057, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands; c.koster@vumc.nl.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Frits Oosterveld, PhD, for critically reviewing the manuscript and Ralph de Vries for his assistance in the literature search.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

1. Griffin LY, Agel J, Albohm MJ, et al. Noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: risk factors and prevention strategies. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:141-50.

2. American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. 2014. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/ACLGuidelineFINAL.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2018.

3. Simon D, Mascarenhas R, Saltzman BM, et al. The relationship between anterior cruciate ligament injury and osteoarthritis of the knee. Adv Orthop. 2015;2015:928301. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410751/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

4. Hinterwimmer S, Engelschalk M, Sauerland S, et al. [Operative or conservative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a systematic review of the literature.] Unfallchirurg. 2003;106:374-379.

5. Brown JR, Trojian TH. Anterior and posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Prim Care. 2004;31:925-956.

6. Leblanc MC, Kowalczuk M, Andruszkiewicz N, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for anterior knee instability: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;10:2805-2813.

7. Lange T, Freiberg A, Dröge P, et al. The reliability of physical examination tests for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture – a systematic review. Man Ther. 2015;20:402-411.

8. Swain MS, Henschke N, Kamper SJ, et al. Accuracy of clinical tests in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:25. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4152763/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

9. van Eck CF, van den Bekerom MP, Fu FH, et al. Methods to diagnose acute anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis of physical examinations with and without anaesthesia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21:1895-1903.

10. Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, van der Schans CP. Clinical diagnosis of an anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:267-288.

11. Jackson J, O’Malley PG, Kroenke K. Evaluation of acute knee pain in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:575-588.

12. Malanga GA, Andrus S, Nadler SF, et al. Physical examination of the knee: a review of the original test description and scientific validity of common orthopedic tests. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:592-603.

13. Scholten RJ, Opstelten W, van der Plas CG, et al. Accuracy of physical diagnostic tests for assessing ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a meta-analysis. J Fam. Pract. 2003;52:689-694.

14. Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, et al. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001;286:1610-1620.

15. Gurtler RA, Stine R, Torg JS. Lachman test evaluated. Quantification of a clinical observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;216:141-150.

16. Atkinson G, Nevill AM. Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sports Med. 1998;26:217-238.

17. Décary S, Ouellet P, Vendittoli PA, et al. Diagnostic validity of physical examination tests for common knee disorders: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2017;23:143-155.

18. Mulligan EP, McGuffie DQ, Coyner K, et al. The reliability and diagnostic accuracy of assessing the translation endpoint during the Lachman test. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015;10:52-61.

19. Floyd RT, Peery DS, Andrews JR. Advantages of the prone Lachman versus the traditional Lachman. Orthopedics. 2008;31:671-675.

20. Lelli A, Di Turi RP, Spenciner DB, et al. The "Lever Sign": a new clinical test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:2794-2797.

21. Deveci A, Cankaya D, Yilmaz S, et al. The arthroscopical and radiological corelation of lever sign test for the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Springerplus. 2015;4:830. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695483/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

22. Jarbo KA, Hartigan DE, Scott KL, et al. Accuracy of the Lever Sign Test in the diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(10):2325967117729809. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5639970/. Accessed January 26, 2018.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Consider using the Lachman test, known to have higher validity than other anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) physical examination tests. When the outcome of a correctly performed test is negative, a rupture of the ACL is unlikely. A

› Use the pivot shift test to confirm a possible ACL rupture only if good execution is assured. Do not use the pivot shift test alone to rule out a possible ACL injury. A

› Familiarize yourself with the lever sign test, which is easy to perform but has yielded varying reports on sensitivity and specificity for ACL rupture. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

March 2018: Click for Credit

Here are 4 articles in the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety Linked to Hyperactivity in Offspring as Teenagers

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BLXsRs

Expires November 15, 2018

2. The Better Mammogram: Experts Explore Sensitivity of New Modalities

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2nQaJii

Expires November 14, 2018

3. Large Database Analysis Suggests Safety of Bariatric Surgery in Seniors

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2E3tcmJ

Expires November 14, 2018

4. Salivary Biomarker for Huntington Disease Identified

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BGQpJP

Expires November 13, 2018

Here are 4 articles in the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety Linked to Hyperactivity in Offspring as Teenagers

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BLXsRs

Expires November 15, 2018

2. The Better Mammogram: Experts Explore Sensitivity of New Modalities

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2nQaJii

Expires November 14, 2018

3. Large Database Analysis Suggests Safety of Bariatric Surgery in Seniors

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2E3tcmJ

Expires November 14, 2018

4. Salivary Biomarker for Huntington Disease Identified

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BGQpJP

Expires November 13, 2018

Here are 4 articles in the March issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Prenatal Maternal Anxiety Linked to Hyperactivity in Offspring as Teenagers

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BLXsRs

Expires November 15, 2018

2. The Better Mammogram: Experts Explore Sensitivity of New Modalities

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2nQaJii

Expires November 14, 2018

3. Large Database Analysis Suggests Safety of Bariatric Surgery in Seniors

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2E3tcmJ

Expires November 14, 2018

4. Salivary Biomarker for Huntington Disease Identified

To take the posttest, go to: http://bit.ly/2BGQpJP

Expires November 13, 2018

Mole on forehead

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

The FP recognized this as a probable intradermal nevus. (Even benign nevi can grow in early adulthood and not be malignant.)

The features that suggested that this was a benign intradermal nevus included that it was a raised symmetrical papule on the face without suspicious signs of melanoma. Intradermal nevi are frequently skin colored because the melanocytes are deep in the dermis. The nevi may show small amounts of color, but are not likely to be dark, as might be seen in a compound nevus or melanoma. The differential diagnosis for a slightly pearly lesion like this, with small visible blood vessels, includes a nodular basal cell carcinoma.

The patient wanted to have the nevus removed to ease her anxiety and because she didn’t like the way it looked. While many insurance companies would reject payment for a cosmetic procedure, they are unlikely to reject payment with a diagnosis of a changing nevus.

The FP reviewed the risks and benefits of a shave biopsy with the patient. A shave biopsy with a sterile razor blade was performed after anesthetizing the area with 1% lidocaine and epinephrine by injection. (See the Watch and Learn video on shave biopsy.) Hemostasis was easily achieved with aluminum chloride in water.

At the 2-week follow-up, the biopsy site was healing well and the patient was reassured that it was only a benign intradermal nevus.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Smith M, Usatine R. Benign nevi. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:945-952.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/.

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com.

Influenza update: A robust season but there's (some) good news

Resource

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: Summary of weekly Fluview report. February 9, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 12, 2018.

Resource

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: Summary of weekly Fluview report. February 9, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 12, 2018.

Resource

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Situation update: Summary of weekly Fluview report. February 9, 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/summary.htm. Accessed February 12, 2018.

HM18 plenaries explore future of hospital medicine

The plenary sessions bookending the Society of Hospital Medicine’s HM18 conference will provide insight into the current state of hospital medicine and a glimpse at the directions in which it is evolving.

Opening the conference will be Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“What I want people to understand is the evolution within our health care system from one where we pay for volume to paying for value, and the role that Medicare can play in that,” Dr. Goodrich said in an interview. “Medicare has traditionally been sort of a passive payer, if you will, a passive payer of claims without a great deal of emphasis on the cost of care and the quality of care. [Now there is] a groundswell of concern nationally, not just here at CMS but nationwide, around the rising cost of care, and our quality of care is not as good as it should be for the amount that we spend.”

Dr. Goodrich said her plenary talk will look at how “that came to be, and then what CMS and other payers in the country are trying to do about it.” She said the United States is in a “truly transformative era in our health care system in changing how we pay for care, in service of better outcomes for patients and lower costs. I would like to give attendees the larger picture, of how we got here and what’s happening both at CMS and nationally to try and reverse some of those trends.”

Closing HM18, as has become tradition at the annual meeting, will be Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, of the University of California San Francisco, who will focus on the broader changes that must happen as the role of the hospitalist continues to evolve.

“I am going to talk about the changes in the world of hospital care and the importance of the field to innovate,” Dr. Wachter said. “To me, there are gravitational forces in the health care world that are making … patients who are in hospitals sicker than they were before. More and more patients are going to be cared for in outpatient settings and at home. We are going start to ... see things like sensors and telemedicine to enable more care outside of the hospital.”

Dr. Wachter said hospital medicine must evolve and mature, to continue to prove that hospitalists are indispensable staff members within the hospital.

“That was why the field became the fastest-growing profession in medical history. We can’t sit on our laurels. We have to continue to innovate,” he said. “Even as the system changes around us, I am confident that we will innovate. My talk will be a pep talk and include reflections on how the world of health care is changing, and what those changes will mean to hospitalists.”

As value-based purchasing programs – and the push to pay for value over volume in Medicare and the private sector – continue to become the norm, the expected trend of sicker, more complex patients entering the hospital is already happening, Dr. Goodrich said. She is experiencing it in her own clinical work, which continues in addition to her role at CMS.

“I can confirm from my own personal experience [that] I have absolutely encountered that exact trend,” she said. “I feel like every time I go in the hospital, my patients are sicker and more complex. That is the population of patients that hospitalists are dealing with. That’s why we are actually in that practice. We enjoy taking care of those types of patients and the challenges they bring, both on a clinical level but I would say also even on a social and economic level.”

Dr. Goodrich said that trend will present one of the key challenges hospitalists face in the future, especially as paying for value entails more two-sided risk.

“In a value-based purchasing world, transitioning to payments based on quality and cost is harder because by nature the sicker patients cost more and it is harder to improve their outcomes. They come to you already quite sick,” she said. “That’s a dilemma that a lot of hospitalists face, wondering ‘How is this going to affect me if I am already seeing the sickest of the sick?’ ”

Dr. Wachter noted that the trend of steering less sick patients to the outpatient setting, as well as other economic factors, would change the nature of hospitalist practice.

“It will be more acuity, more intensity, more complex relationships with your own hospital and often with partner hospitals,” he said. “More of the work will be digitally enabled than it would have been five or ten years ago.”

Integration of data and technology innovation will be a key to better serving this sicker population, Dr. Wachter predicted. We need “to take much fuller advantage than we have so far of the fact that we are all dealing with digital records and the decision support, the data analytics, the artificial intelligence that we get from our computer systems is pretty puny,” he said. “That is partly why physicians don’t love their computers so much. They spend huge amounts of time entering data into computers and don’t get much useful information out of it.”

Dr. Goodrich agreed that this is a challenge.

“How do we make it usable for the average front-line nurse or doctor who didn’t go to school to learn how to code and analyze data?” she asked. “How do we get platforms and analytics that are developed using human-centered design principles to make it very understandable and actionable to the front-end clinician, but also to patients and consumers? What is really needed to truly drive improvement is not just access to the data but usability.” She added that this problem is directly related to the usability of electronic health records. “That is a significant focus right now for the Office of the National Coordinator [of Health Information Technology] – to move away from just [adopting] EHRs, to promoting interoperability and also the usability aspects that exactly gets to the problems we’ve identified.”

Dr. Wachter also warned that too much data could have a negative impact on the delivery of care.

“One of the challenges we face is continuing to stay alert, not turn our brains off, and become increasingly dependent on the computer to give us information,” he said. “How do we avoid the challenges we’ve already seen from things like alert and alarm fatigue as the computer becomes more robust as an information source. There is always the risk it is going to overwhelm us with too much information, and we are going to fall asleep at the switch. Or when the computer says something that really is not right for a patient, we will not be thinking clearly enough to catch it.”

Despite the looming challenges and industry consolidation that are expected, Dr. Wachter doesn’t believe there will be any shortage of demand for hospitalists.

“I think in most circumstances, [hospitalists are a protected] profession, given the complexity, the high variations, and the dependence that it still has on seeing the patient, talking to the patient, and talking to multiple consultants,” he said. “It’s a pretty hard thing to replace with technology. Overall, the job situation is pretty bright.”

The plenary sessions bookending the Society of Hospital Medicine’s HM18 conference will provide insight into the current state of hospital medicine and a glimpse at the directions in which it is evolving.

Opening the conference will be Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“What I want people to understand is the evolution within our health care system from one where we pay for volume to paying for value, and the role that Medicare can play in that,” Dr. Goodrich said in an interview. “Medicare has traditionally been sort of a passive payer, if you will, a passive payer of claims without a great deal of emphasis on the cost of care and the quality of care. [Now there is] a groundswell of concern nationally, not just here at CMS but nationwide, around the rising cost of care, and our quality of care is not as good as it should be for the amount that we spend.”

Dr. Goodrich said her plenary talk will look at how “that came to be, and then what CMS and other payers in the country are trying to do about it.” She said the United States is in a “truly transformative era in our health care system in changing how we pay for care, in service of better outcomes for patients and lower costs. I would like to give attendees the larger picture, of how we got here and what’s happening both at CMS and nationally to try and reverse some of those trends.”

Closing HM18, as has become tradition at the annual meeting, will be Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, of the University of California San Francisco, who will focus on the broader changes that must happen as the role of the hospitalist continues to evolve.

“I am going to talk about the changes in the world of hospital care and the importance of the field to innovate,” Dr. Wachter said. “To me, there are gravitational forces in the health care world that are making … patients who are in hospitals sicker than they were before. More and more patients are going to be cared for in outpatient settings and at home. We are going start to ... see things like sensors and telemedicine to enable more care outside of the hospital.”

Dr. Wachter said hospital medicine must evolve and mature, to continue to prove that hospitalists are indispensable staff members within the hospital.

“That was why the field became the fastest-growing profession in medical history. We can’t sit on our laurels. We have to continue to innovate,” he said. “Even as the system changes around us, I am confident that we will innovate. My talk will be a pep talk and include reflections on how the world of health care is changing, and what those changes will mean to hospitalists.”

As value-based purchasing programs – and the push to pay for value over volume in Medicare and the private sector – continue to become the norm, the expected trend of sicker, more complex patients entering the hospital is already happening, Dr. Goodrich said. She is experiencing it in her own clinical work, which continues in addition to her role at CMS.

“I can confirm from my own personal experience [that] I have absolutely encountered that exact trend,” she said. “I feel like every time I go in the hospital, my patients are sicker and more complex. That is the population of patients that hospitalists are dealing with. That’s why we are actually in that practice. We enjoy taking care of those types of patients and the challenges they bring, both on a clinical level but I would say also even on a social and economic level.”

Dr. Goodrich said that trend will present one of the key challenges hospitalists face in the future, especially as paying for value entails more two-sided risk.

“In a value-based purchasing world, transitioning to payments based on quality and cost is harder because by nature the sicker patients cost more and it is harder to improve their outcomes. They come to you already quite sick,” she said. “That’s a dilemma that a lot of hospitalists face, wondering ‘How is this going to affect me if I am already seeing the sickest of the sick?’ ”

Dr. Wachter noted that the trend of steering less sick patients to the outpatient setting, as well as other economic factors, would change the nature of hospitalist practice.

“It will be more acuity, more intensity, more complex relationships with your own hospital and often with partner hospitals,” he said. “More of the work will be digitally enabled than it would have been five or ten years ago.”

Integration of data and technology innovation will be a key to better serving this sicker population, Dr. Wachter predicted. We need “to take much fuller advantage than we have so far of the fact that we are all dealing with digital records and the decision support, the data analytics, the artificial intelligence that we get from our computer systems is pretty puny,” he said. “That is partly why physicians don’t love their computers so much. They spend huge amounts of time entering data into computers and don’t get much useful information out of it.”

Dr. Goodrich agreed that this is a challenge.

“How do we make it usable for the average front-line nurse or doctor who didn’t go to school to learn how to code and analyze data?” she asked. “How do we get platforms and analytics that are developed using human-centered design principles to make it very understandable and actionable to the front-end clinician, but also to patients and consumers? What is really needed to truly drive improvement is not just access to the data but usability.” She added that this problem is directly related to the usability of electronic health records. “That is a significant focus right now for the Office of the National Coordinator [of Health Information Technology] – to move away from just [adopting] EHRs, to promoting interoperability and also the usability aspects that exactly gets to the problems we’ve identified.”

Dr. Wachter also warned that too much data could have a negative impact on the delivery of care.

“One of the challenges we face is continuing to stay alert, not turn our brains off, and become increasingly dependent on the computer to give us information,” he said. “How do we avoid the challenges we’ve already seen from things like alert and alarm fatigue as the computer becomes more robust as an information source. There is always the risk it is going to overwhelm us with too much information, and we are going to fall asleep at the switch. Or when the computer says something that really is not right for a patient, we will not be thinking clearly enough to catch it.”

Despite the looming challenges and industry consolidation that are expected, Dr. Wachter doesn’t believe there will be any shortage of demand for hospitalists.

“I think in most circumstances, [hospitalists are a protected] profession, given the complexity, the high variations, and the dependence that it still has on seeing the patient, talking to the patient, and talking to multiple consultants,” he said. “It’s a pretty hard thing to replace with technology. Overall, the job situation is pretty bright.”

The plenary sessions bookending the Society of Hospital Medicine’s HM18 conference will provide insight into the current state of hospital medicine and a glimpse at the directions in which it is evolving.

Opening the conference will be Kate Goodrich, MD, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“What I want people to understand is the evolution within our health care system from one where we pay for volume to paying for value, and the role that Medicare can play in that,” Dr. Goodrich said in an interview. “Medicare has traditionally been sort of a passive payer, if you will, a passive payer of claims without a great deal of emphasis on the cost of care and the quality of care. [Now there is] a groundswell of concern nationally, not just here at CMS but nationwide, around the rising cost of care, and our quality of care is not as good as it should be for the amount that we spend.”

Dr. Goodrich said her plenary talk will look at how “that came to be, and then what CMS and other payers in the country are trying to do about it.” She said the United States is in a “truly transformative era in our health care system in changing how we pay for care, in service of better outcomes for patients and lower costs. I would like to give attendees the larger picture, of how we got here and what’s happening both at CMS and nationally to try and reverse some of those trends.”

Closing HM18, as has become tradition at the annual meeting, will be Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, of the University of California San Francisco, who will focus on the broader changes that must happen as the role of the hospitalist continues to evolve.

“I am going to talk about the changes in the world of hospital care and the importance of the field to innovate,” Dr. Wachter said. “To me, there are gravitational forces in the health care world that are making … patients who are in hospitals sicker than they were before. More and more patients are going to be cared for in outpatient settings and at home. We are going start to ... see things like sensors and telemedicine to enable more care outside of the hospital.”

Dr. Wachter said hospital medicine must evolve and mature, to continue to prove that hospitalists are indispensable staff members within the hospital.

“That was why the field became the fastest-growing profession in medical history. We can’t sit on our laurels. We have to continue to innovate,” he said. “Even as the system changes around us, I am confident that we will innovate. My talk will be a pep talk and include reflections on how the world of health care is changing, and what those changes will mean to hospitalists.”

As value-based purchasing programs – and the push to pay for value over volume in Medicare and the private sector – continue to become the norm, the expected trend of sicker, more complex patients entering the hospital is already happening, Dr. Goodrich said. She is experiencing it in her own clinical work, which continues in addition to her role at CMS.

“I can confirm from my own personal experience [that] I have absolutely encountered that exact trend,” she said. “I feel like every time I go in the hospital, my patients are sicker and more complex. That is the population of patients that hospitalists are dealing with. That’s why we are actually in that practice. We enjoy taking care of those types of patients and the challenges they bring, both on a clinical level but I would say also even on a social and economic level.”

Dr. Goodrich said that trend will present one of the key challenges hospitalists face in the future, especially as paying for value entails more two-sided risk.

“In a value-based purchasing world, transitioning to payments based on quality and cost is harder because by nature the sicker patients cost more and it is harder to improve their outcomes. They come to you already quite sick,” she said. “That’s a dilemma that a lot of hospitalists face, wondering ‘How is this going to affect me if I am already seeing the sickest of the sick?’ ”

Dr. Wachter noted that the trend of steering less sick patients to the outpatient setting, as well as other economic factors, would change the nature of hospitalist practice.

“It will be more acuity, more intensity, more complex relationships with your own hospital and often with partner hospitals,” he said. “More of the work will be digitally enabled than it would have been five or ten years ago.”

Integration of data and technology innovation will be a key to better serving this sicker population, Dr. Wachter predicted. We need “to take much fuller advantage than we have so far of the fact that we are all dealing with digital records and the decision support, the data analytics, the artificial intelligence that we get from our computer systems is pretty puny,” he said. “That is partly why physicians don’t love their computers so much. They spend huge amounts of time entering data into computers and don’t get much useful information out of it.”

Dr. Goodrich agreed that this is a challenge.

“How do we make it usable for the average front-line nurse or doctor who didn’t go to school to learn how to code and analyze data?” she asked. “How do we get platforms and analytics that are developed using human-centered design principles to make it very understandable and actionable to the front-end clinician, but also to patients and consumers? What is really needed to truly drive improvement is not just access to the data but usability.” She added that this problem is directly related to the usability of electronic health records. “That is a significant focus right now for the Office of the National Coordinator [of Health Information Technology] – to move away from just [adopting] EHRs, to promoting interoperability and also the usability aspects that exactly gets to the problems we’ve identified.”

Dr. Wachter also warned that too much data could have a negative impact on the delivery of care.

“One of the challenges we face is continuing to stay alert, not turn our brains off, and become increasingly dependent on the computer to give us information,” he said. “How do we avoid the challenges we’ve already seen from things like alert and alarm fatigue as the computer becomes more robust as an information source. There is always the risk it is going to overwhelm us with too much information, and we are going to fall asleep at the switch. Or when the computer says something that really is not right for a patient, we will not be thinking clearly enough to catch it.”

Despite the looming challenges and industry consolidation that are expected, Dr. Wachter doesn’t believe there will be any shortage of demand for hospitalists.

“I think in most circumstances, [hospitalists are a protected] profession, given the complexity, the high variations, and the dependence that it still has on seeing the patient, talking to the patient, and talking to multiple consultants,” he said. “It’s a pretty hard thing to replace with technology. Overall, the job situation is pretty bright.”

Make the Diagnosis - March 2018

Familial benign chronic pemphigus, also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, is an uncommon autosomal dominant genetic condition. A mutation in the calcium ATPase (ATP2C1) gene on chromosome 3q21 interferes with calcium signaling and results in a loss of keratinocyte adhesion. Generally, the onset of the condition is in the second or third decade. There are two clinical subtypes of the disease: segmental type 1 and segmental type 2.

Histology reveals groups of acantholytic cells that resemble a “dilapidated brick wall.” Direct immunofluorescence is negative, unlike pemphigus vulgaris.

As hyperhidrosis is a known aggravating factor, injection with botulinum toxin (this is off-label use not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration) in affected areas to decrease sweating has been reported to be effective.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Familial benign chronic pemphigus, also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, is an uncommon autosomal dominant genetic condition. A mutation in the calcium ATPase (ATP2C1) gene on chromosome 3q21 interferes with calcium signaling and results in a loss of keratinocyte adhesion. Generally, the onset of the condition is in the second or third decade. There are two clinical subtypes of the disease: segmental type 1 and segmental type 2.

Histology reveals groups of acantholytic cells that resemble a “dilapidated brick wall.” Direct immunofluorescence is negative, unlike pemphigus vulgaris.

As hyperhidrosis is a known aggravating factor, injection with botulinum toxin (this is off-label use not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration) in affected areas to decrease sweating has been reported to be effective.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Familial benign chronic pemphigus, also known as Hailey-Hailey disease, is an uncommon autosomal dominant genetic condition. A mutation in the calcium ATPase (ATP2C1) gene on chromosome 3q21 interferes with calcium signaling and results in a loss of keratinocyte adhesion. Generally, the onset of the condition is in the second or third decade. There are two clinical subtypes of the disease: segmental type 1 and segmental type 2.

Histology reveals groups of acantholytic cells that resemble a “dilapidated brick wall.” Direct immunofluorescence is negative, unlike pemphigus vulgaris.

As hyperhidrosis is a known aggravating factor, injection with botulinum toxin (this is off-label use not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration) in affected areas to decrease sweating has been reported to be effective.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

A 39-year-old healthy black woman presented with itchy, painful lesions in the bilateral axillae and groin. The lesions have come and gone for 15 years and flare when the patient perspires. Her mother and grandmother have the same condition.

VIDEO: Model supports endoscopic resection for some T1b esophageal adenocarcinomas

Endoscopic treatment of T1a esophageal adenocarcinoma outperformed esophagectomy across a range of ages and comorbidity levels in a Markov model.

Esophagectomy produced 0.16 more unadjusted life-years, but led to 0.27 fewer quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), in the hypothetical case of a 75-year-old man with T1aN0M0 esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) and a Charlson comorbidity index score of 0, reported Jacqueline N. Chu, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and her associates. “[We] believe QALYs are a more important endpoint because of the significant morbidity associated with esophagectomy,” they wrote in the March issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

In contrast, the model portrayed the management of T1b EAC as “an individualized decision” – esophagectomy was preferable in 60- to 70-year-old patients with T1b EAC, but serial endoscopic treatment was better when patients were older, with more comorbidities, the researchers said. “For the sickest patients, those aged 80 and older with comorbidity index of 2, endoscopic treatment not only provided more QALYs but more unadjusted life years as well.”

Treatment of T1a EAC is transitioning from esophagectomy to serial endoscopic resection, which physicians still tend to regard as too risky in T1b EAC. The Markov model evaluated the efficacy and cost efficacy of the two approaches in hypothetical T1a and T1b patients of various ages and comorbidities, using cancer death data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Medicare database and published cost data converted to 2017 U.S. dollars based on the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index.