User login

ACIP approves new hepatitis A vaccine draft recommendations

, including a focus on catch-up vaccines for adolescents and those over age 40 years.

While hepatitis A cases have dropped significantly since the vaccine’s debut – with the number of reported cases in 2015 dropping to 1,390, compared with 9,606 in 1971 – previous recommendations regarding catch-up vaccinations suggested patients should consider treatment, as opposed to catch-up vaccination.

Adult catch-up vaccines now are recommended to be considered in areas with increasing disease risks, an addition that was not part of the current recommendations but has been changed because of evidence that patients over 40 years old are more vulnerable to the virus and more likely to be hospitalized if infected, said Noele Nelson, MD, PhD, of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the CDC.

“Increasing proportions of adults in the United States are susceptible to hepatitis A ... due to reduced exposure to virus early in life and significant serum prevalence in older adults greater and equal to 40 years,” said Dr. Nelson. “In addition, there is low two-dose vaccination coverage among adults, including high risk adults, and morbidity and mortality increases with age.”

Recommendations for pregnant women also have been updated with a more definitive message. Previous recommendations advised pregnant women to weigh the options of acquiring hepatitis A against possible adverse effects of the vaccine. But, new evidence was presented at the meeting: in a study of 139 pregnant women vaccinated between 1996 and 2015 who experienced adverse effects, only seven of the effects were considered serious, and no maternal or infant deaths were apparent. In light of this, the ACIP approved the recommendation change to advise all pregnant women to be vaccinated, if they have not already been so before pregnancy.

Updates also included recommendations for patients with chronic liver disease, who are considered to be members of a high-risk population. Newly approved recommendations include a section on epidemiology, which states that, while those with chronic liver disease are not at increased risk for hepatitis A virus infection unless they experience fecal-oral exposure to the virus, those with acute hepatitis A may be more at risk to develop more severe liver disease. Recommendations for those with chronic liver disease also include a statement advising patients to seek immunoglobulin, as well as a hepatitis A, vaccination as soon as possible after exposure.

The ACIP also approved a change in recommendations to advise all residents and caretakers of those living in a group home, specifically those caring for developmentally disabled patients, to be vaccinated because of the historically high endemic nature of such institutions.

Committee members hope these new recommendations will help the United States reach its goal of a national hepatitis A case ratio of 0.3/100,000 people and a hepatitis A vaccination rate of 85%.

If these recommendations are approved by the director of the CDC and the U.S. Health Department, as they usually are, they will be published in the CDC’s Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report.

Members of the committee reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

, including a focus on catch-up vaccines for adolescents and those over age 40 years.

While hepatitis A cases have dropped significantly since the vaccine’s debut – with the number of reported cases in 2015 dropping to 1,390, compared with 9,606 in 1971 – previous recommendations regarding catch-up vaccinations suggested patients should consider treatment, as opposed to catch-up vaccination.

Adult catch-up vaccines now are recommended to be considered in areas with increasing disease risks, an addition that was not part of the current recommendations but has been changed because of evidence that patients over 40 years old are more vulnerable to the virus and more likely to be hospitalized if infected, said Noele Nelson, MD, PhD, of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the CDC.

“Increasing proportions of adults in the United States are susceptible to hepatitis A ... due to reduced exposure to virus early in life and significant serum prevalence in older adults greater and equal to 40 years,” said Dr. Nelson. “In addition, there is low two-dose vaccination coverage among adults, including high risk adults, and morbidity and mortality increases with age.”

Recommendations for pregnant women also have been updated with a more definitive message. Previous recommendations advised pregnant women to weigh the options of acquiring hepatitis A against possible adverse effects of the vaccine. But, new evidence was presented at the meeting: in a study of 139 pregnant women vaccinated between 1996 and 2015 who experienced adverse effects, only seven of the effects were considered serious, and no maternal or infant deaths were apparent. In light of this, the ACIP approved the recommendation change to advise all pregnant women to be vaccinated, if they have not already been so before pregnancy.

Updates also included recommendations for patients with chronic liver disease, who are considered to be members of a high-risk population. Newly approved recommendations include a section on epidemiology, which states that, while those with chronic liver disease are not at increased risk for hepatitis A virus infection unless they experience fecal-oral exposure to the virus, those with acute hepatitis A may be more at risk to develop more severe liver disease. Recommendations for those with chronic liver disease also include a statement advising patients to seek immunoglobulin, as well as a hepatitis A, vaccination as soon as possible after exposure.

The ACIP also approved a change in recommendations to advise all residents and caretakers of those living in a group home, specifically those caring for developmentally disabled patients, to be vaccinated because of the historically high endemic nature of such institutions.

Committee members hope these new recommendations will help the United States reach its goal of a national hepatitis A case ratio of 0.3/100,000 people and a hepatitis A vaccination rate of 85%.

If these recommendations are approved by the director of the CDC and the U.S. Health Department, as they usually are, they will be published in the CDC’s Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report.

Members of the committee reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

, including a focus on catch-up vaccines for adolescents and those over age 40 years.

While hepatitis A cases have dropped significantly since the vaccine’s debut – with the number of reported cases in 2015 dropping to 1,390, compared with 9,606 in 1971 – previous recommendations regarding catch-up vaccinations suggested patients should consider treatment, as opposed to catch-up vaccination.

Adult catch-up vaccines now are recommended to be considered in areas with increasing disease risks, an addition that was not part of the current recommendations but has been changed because of evidence that patients over 40 years old are more vulnerable to the virus and more likely to be hospitalized if infected, said Noele Nelson, MD, PhD, of the Division of Viral Hepatitis at the CDC.

“Increasing proportions of adults in the United States are susceptible to hepatitis A ... due to reduced exposure to virus early in life and significant serum prevalence in older adults greater and equal to 40 years,” said Dr. Nelson. “In addition, there is low two-dose vaccination coverage among adults, including high risk adults, and morbidity and mortality increases with age.”

Recommendations for pregnant women also have been updated with a more definitive message. Previous recommendations advised pregnant women to weigh the options of acquiring hepatitis A against possible adverse effects of the vaccine. But, new evidence was presented at the meeting: in a study of 139 pregnant women vaccinated between 1996 and 2015 who experienced adverse effects, only seven of the effects were considered serious, and no maternal or infant deaths were apparent. In light of this, the ACIP approved the recommendation change to advise all pregnant women to be vaccinated, if they have not already been so before pregnancy.

Updates also included recommendations for patients with chronic liver disease, who are considered to be members of a high-risk population. Newly approved recommendations include a section on epidemiology, which states that, while those with chronic liver disease are not at increased risk for hepatitis A virus infection unless they experience fecal-oral exposure to the virus, those with acute hepatitis A may be more at risk to develop more severe liver disease. Recommendations for those with chronic liver disease also include a statement advising patients to seek immunoglobulin, as well as a hepatitis A, vaccination as soon as possible after exposure.

The ACIP also approved a change in recommendations to advise all residents and caretakers of those living in a group home, specifically those caring for developmentally disabled patients, to be vaccinated because of the historically high endemic nature of such institutions.

Committee members hope these new recommendations will help the United States reach its goal of a national hepatitis A case ratio of 0.3/100,000 people and a hepatitis A vaccination rate of 85%.

If these recommendations are approved by the director of the CDC and the U.S. Health Department, as they usually are, they will be published in the CDC’s Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report.

Members of the committee reported no relevant financial disclosures.

ezimmerman@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @eaztweets

FROM ACIP MEETING

Bendamustine plus rituximab may have edge for treating indolent NHL, MCL

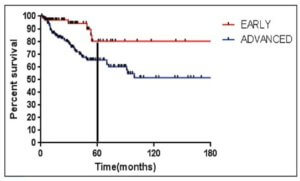

CHICAGO – Overall survival was comparable at 5 years of follow up for three regimens in treatment-naive patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), based on long-term results from the BRIGHT study.

While progression-free survival, event-free survival, and duration of response were significantly better with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), overall survival at 5 years did not significantly differ in patients given this regimen and compared to patients given rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R-CVP), Ian Flinn, MD, of Tennessee Oncology, Nashville, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Quality of life was somewhat better for the patients given BR, but those patients were also at higher risk for secondary malignancies (42 vs. 24), most of which were squamous cell carcinomas, observed Dr. Kahl, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

In BRIGHT, 224 treatment-naive patients with indolent NHL or MCL were randomized to receive BR and were compared to 223 similar patients who received either R-CHOP (104 patients) or R-CVP (119 patients). At least six cycles of therapy were completed by 203 patients in the BR group and by 196 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group. Rituximab maintenance therapy was given to 43% of the BR group and to 45% of the R-CHOP/R-CVP group.

For BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the 5-year progression-free survival rate was 65.5% (95% CI, 58.5-71.6) and 55.8% (95% CI, 48.4-62.5), respectively. The overall survival rate for the entire patient group was 81.7% (75.7-86.3) and 85% (79.3-89.3) respectively. Comparing BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the hazard ratio (95% CI) for progression-free survival was 0.61 (0.45-0.85; P = .0025), the HR for event-free survival was 0.63 (0.46-0.84; P = .0020), the HR for duration of response was 0.66 (0.47-0.92; P = .0134), and the HR for overall survival was 1.15 (0.72-1.84; P = .5461).

Similar results were found in indolent NHL (progression-free survival 0.70 [0.49-1.01; P = .0582]) and MCL (progression-free survival 0.40 [0.21-0.75; P = .0035]), with the strongest effect in MCL, Dr. Flinn said.

Dr. Kahl noted that the advantages for the BR regimen include that it is not associated with alopecia, neuropathy, or steroid issues, and that it may extend progression-free survival and time to next treatment. On the other hand, R-CHOP is associated with less GI toxicity, rash, opportunistic infections, and prolonged cytopenia. Also, the BR regimen was associated with a higher risk of secondary cancers, primarily squamous cell carcinomas.

There were 42 secondary malignancies in the BR group and 24 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group, Dr. Flinn reported.

It is theoretically possible that BR equals R-CHOP plus maintenance therapy from an efficacy perspective, Dr. Kahl said.

As virtually all excess adverse event fatalities occurred during maintenance therapy, it is possible that maintenance therapy after BR “does more harm than good.” This high priority issue “should be evaluated in the BRIGHT data set,” Dr. Kahl recommended.

Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D sponsored the study. Dr. Flinn had no relationships to disclose; two of his fellow researchers are Teva employees. Dr. Kahl disclosed serving as an adviser or consultant to Abbvie, Acerta Pharma, Celgene, Cell Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Incyte, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Juno Therapeutics, Millennium, Pharmacyclics, Sandoz, and Seattle Genetics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Overall survival was comparable at 5 years of follow up for three regimens in treatment-naive patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), based on long-term results from the BRIGHT study.

While progression-free survival, event-free survival, and duration of response were significantly better with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), overall survival at 5 years did not significantly differ in patients given this regimen and compared to patients given rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R-CVP), Ian Flinn, MD, of Tennessee Oncology, Nashville, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Quality of life was somewhat better for the patients given BR, but those patients were also at higher risk for secondary malignancies (42 vs. 24), most of which were squamous cell carcinomas, observed Dr. Kahl, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

In BRIGHT, 224 treatment-naive patients with indolent NHL or MCL were randomized to receive BR and were compared to 223 similar patients who received either R-CHOP (104 patients) or R-CVP (119 patients). At least six cycles of therapy were completed by 203 patients in the BR group and by 196 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group. Rituximab maintenance therapy was given to 43% of the BR group and to 45% of the R-CHOP/R-CVP group.

For BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the 5-year progression-free survival rate was 65.5% (95% CI, 58.5-71.6) and 55.8% (95% CI, 48.4-62.5), respectively. The overall survival rate for the entire patient group was 81.7% (75.7-86.3) and 85% (79.3-89.3) respectively. Comparing BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the hazard ratio (95% CI) for progression-free survival was 0.61 (0.45-0.85; P = .0025), the HR for event-free survival was 0.63 (0.46-0.84; P = .0020), the HR for duration of response was 0.66 (0.47-0.92; P = .0134), and the HR for overall survival was 1.15 (0.72-1.84; P = .5461).

Similar results were found in indolent NHL (progression-free survival 0.70 [0.49-1.01; P = .0582]) and MCL (progression-free survival 0.40 [0.21-0.75; P = .0035]), with the strongest effect in MCL, Dr. Flinn said.

Dr. Kahl noted that the advantages for the BR regimen include that it is not associated with alopecia, neuropathy, or steroid issues, and that it may extend progression-free survival and time to next treatment. On the other hand, R-CHOP is associated with less GI toxicity, rash, opportunistic infections, and prolonged cytopenia. Also, the BR regimen was associated with a higher risk of secondary cancers, primarily squamous cell carcinomas.

There were 42 secondary malignancies in the BR group and 24 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group, Dr. Flinn reported.

It is theoretically possible that BR equals R-CHOP plus maintenance therapy from an efficacy perspective, Dr. Kahl said.

As virtually all excess adverse event fatalities occurred during maintenance therapy, it is possible that maintenance therapy after BR “does more harm than good.” This high priority issue “should be evaluated in the BRIGHT data set,” Dr. Kahl recommended.

Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D sponsored the study. Dr. Flinn had no relationships to disclose; two of his fellow researchers are Teva employees. Dr. Kahl disclosed serving as an adviser or consultant to Abbvie, Acerta Pharma, Celgene, Cell Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Incyte, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Juno Therapeutics, Millennium, Pharmacyclics, Sandoz, and Seattle Genetics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

CHICAGO – Overall survival was comparable at 5 years of follow up for three regimens in treatment-naive patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), based on long-term results from the BRIGHT study.

While progression-free survival, event-free survival, and duration of response were significantly better with bendamustine plus rituximab (BR), overall survival at 5 years did not significantly differ in patients given this regimen and compared to patients given rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) or rituximab with cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone (R-CVP), Ian Flinn, MD, of Tennessee Oncology, Nashville, reported at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Quality of life was somewhat better for the patients given BR, but those patients were also at higher risk for secondary malignancies (42 vs. 24), most of which were squamous cell carcinomas, observed Dr. Kahl, professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

In BRIGHT, 224 treatment-naive patients with indolent NHL or MCL were randomized to receive BR and were compared to 223 similar patients who received either R-CHOP (104 patients) or R-CVP (119 patients). At least six cycles of therapy were completed by 203 patients in the BR group and by 196 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group. Rituximab maintenance therapy was given to 43% of the BR group and to 45% of the R-CHOP/R-CVP group.

For BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the 5-year progression-free survival rate was 65.5% (95% CI, 58.5-71.6) and 55.8% (95% CI, 48.4-62.5), respectively. The overall survival rate for the entire patient group was 81.7% (75.7-86.3) and 85% (79.3-89.3) respectively. Comparing BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the hazard ratio (95% CI) for progression-free survival was 0.61 (0.45-0.85; P = .0025), the HR for event-free survival was 0.63 (0.46-0.84; P = .0020), the HR for duration of response was 0.66 (0.47-0.92; P = .0134), and the HR for overall survival was 1.15 (0.72-1.84; P = .5461).

Similar results were found in indolent NHL (progression-free survival 0.70 [0.49-1.01; P = .0582]) and MCL (progression-free survival 0.40 [0.21-0.75; P = .0035]), with the strongest effect in MCL, Dr. Flinn said.

Dr. Kahl noted that the advantages for the BR regimen include that it is not associated with alopecia, neuropathy, or steroid issues, and that it may extend progression-free survival and time to next treatment. On the other hand, R-CHOP is associated with less GI toxicity, rash, opportunistic infections, and prolonged cytopenia. Also, the BR regimen was associated with a higher risk of secondary cancers, primarily squamous cell carcinomas.

There were 42 secondary malignancies in the BR group and 24 in the R-CHOP/R-CVP group, Dr. Flinn reported.

It is theoretically possible that BR equals R-CHOP plus maintenance therapy from an efficacy perspective, Dr. Kahl said.

As virtually all excess adverse event fatalities occurred during maintenance therapy, it is possible that maintenance therapy after BR “does more harm than good.” This high priority issue “should be evaluated in the BRIGHT data set,” Dr. Kahl recommended.

Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D sponsored the study. Dr. Flinn had no relationships to disclose; two of his fellow researchers are Teva employees. Dr. Kahl disclosed serving as an adviser or consultant to Abbvie, Acerta Pharma, Celgene, Cell Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Incyte, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Juno Therapeutics, Millennium, Pharmacyclics, Sandoz, and Seattle Genetics.

mdales@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryjodales

AT ASCO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For BR and R-CHOP/R-CVP, the 5-year progression-free survival rate was 65.5% (95% CI, 58.5-71.6) and 55.8% (95% CI, 48.4-62.5), respectively.

Data source: In BRIGHT, 224 treatment-naive patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma or mantle cell lymphoma were randomized to receive BR and were compared to 223 similar patients who received either R-CHOP (104 patients) or R-CVP (119 patients).

Disclosures: Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D sponsored the study. Dr. Flinn had no relationships to disclose; two of his fellow researchers are Teva employees. Dr. Kahl disclosed serving as an adviser or consultant to Abbvie, Acerta Pharma, Celgene, Cell Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Incyte, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Juno Therapeutics, Millennium, Pharmacyclics, Sandoz, and Seattle Genetics.

Hospitalist meta-leader: Your new mission has arrived

If you are a hospitalist and leader in your health care organization, the ongoing controversies surrounding the Affordable Care Act repeal and replace campaign are unsettling. No matter your politics, Washington’s political drama and gamesmanship pose a genuine threat to the solvency of your hospital’s budget, services, workforce, and patients.

Health care has devolved into a political football, tossed from skirmish to skirmish. Political leaders warn of the implosion of the health care system as a political tactic, not an outcome that could cost and ruin lives. Both Democrats and Republicans hope that if or when that happens, it does so in ways that allow them to blame the other side. For them, this is a game of partisan advantage that wagers the well-being of your health care system.

For you, the situation remains predictably unpredictable. The future directives from Washington are unknowable. This makes your strategic planning – and health care leadership itself – a complex and puzzling task. Your job now is not simply leading your organization for today. Your more important mission is preparing your organization to perform in this unpredictable and perplexing future.

Forecasting is the life blood of leadership: Craft a vision and the work to achieve it; be mindful of the range of obstacles and opportunities; and know and coalesce your followers. The problem is that today’s prospects are loaded with puzzling twists and turns. The viability of both the private insurance market and public dollars are – maybe! – in future jeopardy. Patients and the workforce are understandably jittery. What is a hospitalist leader to do?

It is time to refresh your thinking, to take a big picture view of what is happening and to assess what can be done about it. There is a tendency for leaders to look at problems and then wonder how to fit solutions into their established organizational framework. In other words, solutions are cast into the mold of retaining what you have, ignoring larger options and innovative possibilities. Solutions are expected to adapt to the organization rather than the organization adapting to the solutions.

The hospitalist movement grew as early leaders – true innovators – recognized the problems of costly, inefficient and uncoordinated care. Rather than tinkering with what was, hospitalist leaders introduced a new and proactive model to provide care. It had to first prove itself and once it did, a once revolutionary idea evolved into an institutionalized solution.

No matter what emerges from the current policy debate, the national pressures on the health care system persist: rising expectations for access; decreasing patience for spending; increasing appetite for breakthrough technology; shifting workforce requirements; all combined with a population that is aging and more in need of care. These are meta-trends that will redefine how the health system operates and what it will achieve. What is a health care leader to do?

Think and act like a “meta-leader.” This framework, developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, guides leaders facing complex and transformational problem solving. The prefix “meta-” encourages expansive analysis directed toward a wide range of options and opportunities. In keeping with the strategies employed by hospitalist pioneers, rather than building solutions around “what already is,” meta-leaders pursue “what could be.” In this way, solutions are designed and constructed to fit the problems they are intended to overcome.

There are three critical dimensions to the thinking and practices of meta-leadership.

The first is the Person of the meta-leader. This is who you are, your priorities and values. This is how other people regard your leadership, translated into the respect, trust, and “followership” you garner. Be a role model. This involves building your own confidence for the task at hand so that you gain and then foster the confidence of those you lead. As a meta-leader, you shape your mindset and that of others for innovation, sharpening the curiosity necessary for fostering discovery and exploration of new ideas. Be ready to take appropriate risks.

The second dimension of meta-leadership practice is the Situation. This is what is happening and what can be done about it. You did not create the complex circumstances that derive from the political showdown in Washington. However, it is your job to understand them and to develop effective strategies and operations in response. This is where the “think big” of meta-leadership comes into play. You distinguish the chasm between the adversarial policy confrontation in Washington and the collaborative solution building needed in your home institution. You want to set the stage to meaningfully coalesce the thinking, resources, and people in your organization. The invigorated shared mission is a health care system that leads into the future.

The third dimension of meta-leadership practice is about building the Connectivity needed to make that happen. This involves developing the communication, coordination, and cooperation necessary for constructing something new. Many of your answers lie within the walls of your organization, even the most innovative among them. This is where you sow adaptability and flexibility. It translates into necessary change and transformation. This is reorienting what you and others do and how you go about doing it, from shifts and adjustments to, when necessary, disruptive innovation.

A recent Harvard Business School and Harvard Medical School forum on health care innovation identified five imperatives for meeting innovation challenges in health care: 1) Creating value is the key aim for innovation and it requires a combination of care coordination along with communication; 2) Seek opportunities for process improvement that allows new ideas to be tested, accepting that failure is a step on the road to discovery; 3) Adopt a consumerism strategy for service organization that engages and involves active patients; 4) Decentralize problem solving to encourage field innovation and collaboration; and 5) Integrate new models into established institutions, introducing fresh thinking to replace outdated practices.

Meta-leadership is not a formula for an easy fix. While much remains unpredictable, an impending economic squeeze is a likely scenario. There is nothing easy about a shortage of dollars to serve more and more people in need of clinical care. This may very well be the prompt – today – that encourages the sort of innovative thinking and disruptive solution development that the future requires. Will you and your organization get ahead of this curve?

Your mission as a hospitalist meta-leader is in forging this process of discovery. Perceive what is going on through a wide lens. Orient yourself to emerging trends. Predict what is likely to emerge from this unpredictable policy environment. Take decisions and operationalize them in ways responsive to the circumstances at hand. And then communicate with your constituencies, not only to inform them of direction but also to learn from them what is working and what not. And then you start the process again, trying on ideas and practices, learning from them and through this continuous process, finding solutions that fit your situation at hand.

Health care meta-leaders today must keep both eyes firmly on their feet, to know that current operations are achieving necessary success. At the same time, they must also keep both eyes focused on the horizon, to ensure that when conditions change, their organizations are ready to adaptively innovate and transform.

Leonard J. Marcus, Ph.D. is coauthor of Renegotiating Health Care: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration, Second Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2011) and is director of the program for health care negotiation and conflict resolution, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Marcus teaches regularly in the SHM Leadership Academy. He can be reached at ljmarcus@hsph.harvard.edu

If you are a hospitalist and leader in your health care organization, the ongoing controversies surrounding the Affordable Care Act repeal and replace campaign are unsettling. No matter your politics, Washington’s political drama and gamesmanship pose a genuine threat to the solvency of your hospital’s budget, services, workforce, and patients.

Health care has devolved into a political football, tossed from skirmish to skirmish. Political leaders warn of the implosion of the health care system as a political tactic, not an outcome that could cost and ruin lives. Both Democrats and Republicans hope that if or when that happens, it does so in ways that allow them to blame the other side. For them, this is a game of partisan advantage that wagers the well-being of your health care system.

For you, the situation remains predictably unpredictable. The future directives from Washington are unknowable. This makes your strategic planning – and health care leadership itself – a complex and puzzling task. Your job now is not simply leading your organization for today. Your more important mission is preparing your organization to perform in this unpredictable and perplexing future.

Forecasting is the life blood of leadership: Craft a vision and the work to achieve it; be mindful of the range of obstacles and opportunities; and know and coalesce your followers. The problem is that today’s prospects are loaded with puzzling twists and turns. The viability of both the private insurance market and public dollars are – maybe! – in future jeopardy. Patients and the workforce are understandably jittery. What is a hospitalist leader to do?

It is time to refresh your thinking, to take a big picture view of what is happening and to assess what can be done about it. There is a tendency for leaders to look at problems and then wonder how to fit solutions into their established organizational framework. In other words, solutions are cast into the mold of retaining what you have, ignoring larger options and innovative possibilities. Solutions are expected to adapt to the organization rather than the organization adapting to the solutions.

The hospitalist movement grew as early leaders – true innovators – recognized the problems of costly, inefficient and uncoordinated care. Rather than tinkering with what was, hospitalist leaders introduced a new and proactive model to provide care. It had to first prove itself and once it did, a once revolutionary idea evolved into an institutionalized solution.

No matter what emerges from the current policy debate, the national pressures on the health care system persist: rising expectations for access; decreasing patience for spending; increasing appetite for breakthrough technology; shifting workforce requirements; all combined with a population that is aging and more in need of care. These are meta-trends that will redefine how the health system operates and what it will achieve. What is a health care leader to do?

Think and act like a “meta-leader.” This framework, developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, guides leaders facing complex and transformational problem solving. The prefix “meta-” encourages expansive analysis directed toward a wide range of options and opportunities. In keeping with the strategies employed by hospitalist pioneers, rather than building solutions around “what already is,” meta-leaders pursue “what could be.” In this way, solutions are designed and constructed to fit the problems they are intended to overcome.

There are three critical dimensions to the thinking and practices of meta-leadership.

The first is the Person of the meta-leader. This is who you are, your priorities and values. This is how other people regard your leadership, translated into the respect, trust, and “followership” you garner. Be a role model. This involves building your own confidence for the task at hand so that you gain and then foster the confidence of those you lead. As a meta-leader, you shape your mindset and that of others for innovation, sharpening the curiosity necessary for fostering discovery and exploration of new ideas. Be ready to take appropriate risks.

The second dimension of meta-leadership practice is the Situation. This is what is happening and what can be done about it. You did not create the complex circumstances that derive from the political showdown in Washington. However, it is your job to understand them and to develop effective strategies and operations in response. This is where the “think big” of meta-leadership comes into play. You distinguish the chasm between the adversarial policy confrontation in Washington and the collaborative solution building needed in your home institution. You want to set the stage to meaningfully coalesce the thinking, resources, and people in your organization. The invigorated shared mission is a health care system that leads into the future.

The third dimension of meta-leadership practice is about building the Connectivity needed to make that happen. This involves developing the communication, coordination, and cooperation necessary for constructing something new. Many of your answers lie within the walls of your organization, even the most innovative among them. This is where you sow adaptability and flexibility. It translates into necessary change and transformation. This is reorienting what you and others do and how you go about doing it, from shifts and adjustments to, when necessary, disruptive innovation.

A recent Harvard Business School and Harvard Medical School forum on health care innovation identified five imperatives for meeting innovation challenges in health care: 1) Creating value is the key aim for innovation and it requires a combination of care coordination along with communication; 2) Seek opportunities for process improvement that allows new ideas to be tested, accepting that failure is a step on the road to discovery; 3) Adopt a consumerism strategy for service organization that engages and involves active patients; 4) Decentralize problem solving to encourage field innovation and collaboration; and 5) Integrate new models into established institutions, introducing fresh thinking to replace outdated practices.

Meta-leadership is not a formula for an easy fix. While much remains unpredictable, an impending economic squeeze is a likely scenario. There is nothing easy about a shortage of dollars to serve more and more people in need of clinical care. This may very well be the prompt – today – that encourages the sort of innovative thinking and disruptive solution development that the future requires. Will you and your organization get ahead of this curve?

Your mission as a hospitalist meta-leader is in forging this process of discovery. Perceive what is going on through a wide lens. Orient yourself to emerging trends. Predict what is likely to emerge from this unpredictable policy environment. Take decisions and operationalize them in ways responsive to the circumstances at hand. And then communicate with your constituencies, not only to inform them of direction but also to learn from them what is working and what not. And then you start the process again, trying on ideas and practices, learning from them and through this continuous process, finding solutions that fit your situation at hand.

Health care meta-leaders today must keep both eyes firmly on their feet, to know that current operations are achieving necessary success. At the same time, they must also keep both eyes focused on the horizon, to ensure that when conditions change, their organizations are ready to adaptively innovate and transform.

Leonard J. Marcus, Ph.D. is coauthor of Renegotiating Health Care: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration, Second Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2011) and is director of the program for health care negotiation and conflict resolution, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Marcus teaches regularly in the SHM Leadership Academy. He can be reached at ljmarcus@hsph.harvard.edu

If you are a hospitalist and leader in your health care organization, the ongoing controversies surrounding the Affordable Care Act repeal and replace campaign are unsettling. No matter your politics, Washington’s political drama and gamesmanship pose a genuine threat to the solvency of your hospital’s budget, services, workforce, and patients.

Health care has devolved into a political football, tossed from skirmish to skirmish. Political leaders warn of the implosion of the health care system as a political tactic, not an outcome that could cost and ruin lives. Both Democrats and Republicans hope that if or when that happens, it does so in ways that allow them to blame the other side. For them, this is a game of partisan advantage that wagers the well-being of your health care system.

For you, the situation remains predictably unpredictable. The future directives from Washington are unknowable. This makes your strategic planning – and health care leadership itself – a complex and puzzling task. Your job now is not simply leading your organization for today. Your more important mission is preparing your organization to perform in this unpredictable and perplexing future.

Forecasting is the life blood of leadership: Craft a vision and the work to achieve it; be mindful of the range of obstacles and opportunities; and know and coalesce your followers. The problem is that today’s prospects are loaded with puzzling twists and turns. The viability of both the private insurance market and public dollars are – maybe! – in future jeopardy. Patients and the workforce are understandably jittery. What is a hospitalist leader to do?

It is time to refresh your thinking, to take a big picture view of what is happening and to assess what can be done about it. There is a tendency for leaders to look at problems and then wonder how to fit solutions into their established organizational framework. In other words, solutions are cast into the mold of retaining what you have, ignoring larger options and innovative possibilities. Solutions are expected to adapt to the organization rather than the organization adapting to the solutions.

The hospitalist movement grew as early leaders – true innovators – recognized the problems of costly, inefficient and uncoordinated care. Rather than tinkering with what was, hospitalist leaders introduced a new and proactive model to provide care. It had to first prove itself and once it did, a once revolutionary idea evolved into an institutionalized solution.

No matter what emerges from the current policy debate, the national pressures on the health care system persist: rising expectations for access; decreasing patience for spending; increasing appetite for breakthrough technology; shifting workforce requirements; all combined with a population that is aging and more in need of care. These are meta-trends that will redefine how the health system operates and what it will achieve. What is a health care leader to do?

Think and act like a “meta-leader.” This framework, developed at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, guides leaders facing complex and transformational problem solving. The prefix “meta-” encourages expansive analysis directed toward a wide range of options and opportunities. In keeping with the strategies employed by hospitalist pioneers, rather than building solutions around “what already is,” meta-leaders pursue “what could be.” In this way, solutions are designed and constructed to fit the problems they are intended to overcome.

There are three critical dimensions to the thinking and practices of meta-leadership.

The first is the Person of the meta-leader. This is who you are, your priorities and values. This is how other people regard your leadership, translated into the respect, trust, and “followership” you garner. Be a role model. This involves building your own confidence for the task at hand so that you gain and then foster the confidence of those you lead. As a meta-leader, you shape your mindset and that of others for innovation, sharpening the curiosity necessary for fostering discovery and exploration of new ideas. Be ready to take appropriate risks.

The second dimension of meta-leadership practice is the Situation. This is what is happening and what can be done about it. You did not create the complex circumstances that derive from the political showdown in Washington. However, it is your job to understand them and to develop effective strategies and operations in response. This is where the “think big” of meta-leadership comes into play. You distinguish the chasm between the adversarial policy confrontation in Washington and the collaborative solution building needed in your home institution. You want to set the stage to meaningfully coalesce the thinking, resources, and people in your organization. The invigorated shared mission is a health care system that leads into the future.

The third dimension of meta-leadership practice is about building the Connectivity needed to make that happen. This involves developing the communication, coordination, and cooperation necessary for constructing something new. Many of your answers lie within the walls of your organization, even the most innovative among them. This is where you sow adaptability and flexibility. It translates into necessary change and transformation. This is reorienting what you and others do and how you go about doing it, from shifts and adjustments to, when necessary, disruptive innovation.

A recent Harvard Business School and Harvard Medical School forum on health care innovation identified five imperatives for meeting innovation challenges in health care: 1) Creating value is the key aim for innovation and it requires a combination of care coordination along with communication; 2) Seek opportunities for process improvement that allows new ideas to be tested, accepting that failure is a step on the road to discovery; 3) Adopt a consumerism strategy for service organization that engages and involves active patients; 4) Decentralize problem solving to encourage field innovation and collaboration; and 5) Integrate new models into established institutions, introducing fresh thinking to replace outdated practices.

Meta-leadership is not a formula for an easy fix. While much remains unpredictable, an impending economic squeeze is a likely scenario. There is nothing easy about a shortage of dollars to serve more and more people in need of clinical care. This may very well be the prompt – today – that encourages the sort of innovative thinking and disruptive solution development that the future requires. Will you and your organization get ahead of this curve?

Your mission as a hospitalist meta-leader is in forging this process of discovery. Perceive what is going on through a wide lens. Orient yourself to emerging trends. Predict what is likely to emerge from this unpredictable policy environment. Take decisions and operationalize them in ways responsive to the circumstances at hand. And then communicate with your constituencies, not only to inform them of direction but also to learn from them what is working and what not. And then you start the process again, trying on ideas and practices, learning from them and through this continuous process, finding solutions that fit your situation at hand.

Health care meta-leaders today must keep both eyes firmly on their feet, to know that current operations are achieving necessary success. At the same time, they must also keep both eyes focused on the horizon, to ensure that when conditions change, their organizations are ready to adaptively innovate and transform.

Leonard J. Marcus, Ph.D. is coauthor of Renegotiating Health Care: Resolving Conflict to Build Collaboration, Second Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 2011) and is director of the program for health care negotiation and conflict resolution, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Dr. Marcus teaches regularly in the SHM Leadership Academy. He can be reached at ljmarcus@hsph.harvard.edu

Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21

There are no reported studies exploring the efficacy of psychotherapy or psychotropic medications for patients with ON. However, several treatments have been proposed given the symptom overlap with AN. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive traits.18 However, patients with ON may refuse medications as unnatural substances.18

Cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial to address perfectionism and cognitive distortions, and exposure and response prevention may reduce obsessive-compulsive behaviors.11 Relaxation therapy may reduce mealtime anxiety. Psychoeducation may correct inaccurate beliefs about food groups, purity, and preparation, but it may induce emotional stress for the patient with ON.11

Conclusion

Orthorexia nervosa is perhaps best summarized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors. However, the attempt to attain optimum health through attention to diet may lead to malnourishment, loss of relationships, and poor quality of life.11 It is a little-understood disorder with uncertain etiology, imprecise assessment tools, and no formal diagnostic criteria or classification. Orthorexic characteristics vary from normal to pathologic in degree, and making a diagnosis remains a clinical judgment.22 Further research is needed to develop valid diagnostic tools and determining whether ON should be classified as a unique illness or a variation of other eating or anxiety disorders. Further research also may identify the etiology of ON, thus enabling targeted multidisciplinary treatment.

1. Bratman S. Health food junkie. Yoga J. 1997;136:42-50.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Feeding and eating disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:329-354.

3. Varga M, Dukay-Szabó S, Túry F, van Furth EF. Evidence and gaps in the literature on orthorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;18(2):103-111.

4. Donini LM, Marsili D, Graziani MP, Imbriale M, Cannella C. Orthorexia nervosa: validation of a diagnosis questionnaire. Eat Weight Disord. 2005;10(2):e28-e32.

5. Dunn TM, Gibbs J, Whitney N, Starosta A. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa is less than 1 %: data from a US sample. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;22(1):185-192.

6. Bundros J, Clifford D, Silliman K, Neyman Morris M. Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman’s test and associated tendencies. Appetite. 2016;101:86-94.

7. Vandereycken W. Media hype, diagnostic fad or genuine disorder? Professionals’ opinions about night eating syndrome, orthorexia, muscle dysmorphia, and emetophobia. Eat Disord. 2011;19(2):145-155.

8. Dell’Osso L, Abelli M, Carpita B, et al. Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive-compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1651-1660.

9. Bratman S. Orthorexia: an update. http://www.orthorexia.com/orthorexia-an-update. Updated October 5, 2015. Accessed April 18, 2017.

10. Dunn TM, Bratman S. On orthorexia nervosa: a review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eat Behav. 2016;21:11-17.

11. Koven NS, Abry AW. The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:385-394.

12. Saddichha S, Babu GN, Chandra P. Orthorexia nervosa presenting as prodrome of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):110.

13. Koven NS, Senbonmatsu R. A neuropsychological evaluation of orthorexia nervosa. Open J Psychiatry. 2013;3(2):214-222.

14. Gorwood P, Blanchet-Collet C, Chartrel N, et al. New insights in anorexia nervosa. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:256.

15. Milad MR, Rauch SL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16(1):43-51.

16. Tang W, Zhu Q, Gong X, Zhu C, Wang Y, Chen S. Cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuit abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A voxel-based morphometric and fMRI study of the whole brain. Behav Brain Res. 2016;313:17-22.

17. Barnes MA, Caltabiano ML. The interrelationship between orthorexia nervosa, perfectionism, body image and attachment style. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22(1):177-184.

18. Mathieu J. What is orthorexia? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105(10):1510-1512.

19. Catalina Zamora ML, Bote Bonaechea B, García Sánchez F, Ríos Rial B. Orthorexia nervosa. A new eating behavior disorder? [in Spanish]. Actas Esp Psiquiatr. 2005;33(1):66-68.

20. Moroze RM, Dunn TM, Craig Holland J, Yager J, Weintraub P. Microthinking about micronutrients: a case of transition from obsessions about healthy eating to near-fatal “orthorexia nervosa” and proposed diagnostic criteria. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(4):397-403.

21. Park SW, Kim JY, Go GJ, Jeon ES, Pyo HJ, Kwon YJ. Orthorexia nervosa with hyponatremia, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastimum, pneumothorax, and pancytopenia. Electrolyte Blood Press. 2011;9(1):32-37.

22. Mogallapu RNG, Aynampudi AR, Scarff JR, Lippmann S. Orthorexia nervosa. The Kentucky Psychiatrist. 2012;22(3):3-6.

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21

There are no reported studies exploring the efficacy of psychotherapy or psychotropic medications for patients with ON. However, several treatments have been proposed given the symptom overlap with AN. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be beneficial for anxiety and obsessive-compulsive traits.18 However, patients with ON may refuse medications as unnatural substances.18

Cognitive behavioral therapy may be beneficial to address perfectionism and cognitive distortions, and exposure and response prevention may reduce obsessive-compulsive behaviors.11 Relaxation therapy may reduce mealtime anxiety. Psychoeducation may correct inaccurate beliefs about food groups, purity, and preparation, but it may induce emotional stress for the patient with ON.11

Conclusion

Orthorexia nervosa is perhaps best summarized as an obsession with healthy eating with associated restrictive behaviors. However, the attempt to attain optimum health through attention to diet may lead to malnourishment, loss of relationships, and poor quality of life.11 It is a little-understood disorder with uncertain etiology, imprecise assessment tools, and no formal diagnostic criteria or classification. Orthorexic characteristics vary from normal to pathologic in degree, and making a diagnosis remains a clinical judgment.22 Further research is needed to develop valid diagnostic tools and determining whether ON should be classified as a unique illness or a variation of other eating or anxiety disorders. Further research also may identify the etiology of ON, thus enabling targeted multidisciplinary treatment.

First named by Steven Bratman in 1997, orthorexia nervosa (ON) from the Greek ortho, meaning correct, and orexi, meaning appetite, is classified as an unspecified feeding and eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5).1,2

Hypothetical Case

Mr. P is a 30-year-old male who presented to the mental health clinic with his wife. The patient recounted that he had wanted to “be healthy” since childhood and has focused on exercise and proper diet, but anxiety about diet and food intake have steadily increased. Two years ago, he adopted a vegetarian diet by progressively eliminating several foods and food groups from his diet. He now feels “proud” to eat certain organically grown fruits, vegetables, nuts, beans, and drink only fruit or vegetable juice.

His wife stated that he spent between 3 and 5 hours daily preparing food or talking to friends and family about “correct foods to eat.” He also believed that errors in dietary habits caused physical or mental illnesses. He reported significant guilt and shame whenever he “slips up” on his dietary regimen and eats anything containing seafood, beef, or pork products, which he corrects by a day of fasting. His wife was frustrated because he refused to go to restaurants and started declining offers from friends to eat dinner at their homes unless he could bring his prepared food. He describes feeling “annoyed” when he sees other people eating fast food or meat.

Mr. P reported no significant medical or surgical history. His family history was significant for anxiety in his mother. He used to drink alcohol socially but ceased a few years ago due to its carbohydrate content. He never smoked or used illicit drugs.

A mental status exam revealed a thin male who appeared his stated age. He was cooperative, casually dressed, and made fair eye contact. He spoke clearly with an anxious tone and appropriate rate and volume. His affect was congruent with stated anxious mood. He was alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He reported no paranoia, auditory or visual hallucinations, and suicidal or homicidal ideation.

A physical exam revealed a thin male in no distress who measured 5 feet 10 inches tall and weighed 145 pounds, which yielded a body mass index of 20.8. His vitals included temperature of 98° F, blood pressure 115/76, pulse 74, and oxygen saturation 98% on room air. The remaining physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A complete blood count, thyroid function, urinalysis, and urine drug screens were within normal limits. Comprehensive metabolic profile revealed decreased sodium of 130 meq/L. Electrocardiogram revealed bradycardia.

An ON diagnosis is made primarily through a clinical interview. Collateral information from individuals familiar with the patient can be helpful. Experts have proposed and recently revised criteria for ON (Table). Although the ORTO-15 assessment tool may assist with diagnosis, the tool does not substitute for the clinical interview.

Discussion

There is no reliable measure of prevalence of ON, though Varga and colleagues initially estimated ON to occur in 6.9% of the general population, and ON may occur more frequently in health care professionals and performance artists.3 However, these may be overestimates, as the assessment tool used in the study does not adequately separate people with healthy eating habits from those with ON.4,5

Most prevalence studies were conducted in Europe and Turkey, and prevalence of ON may differ in the U.S. population. A recent assessment determined a prevalence of about 1%, similar to that of other eating disorders.5 No study has reported a correlation between ON and gender, but a survey of 448 college students in the U.S. (mean age 22 years) reported highest ON tendencies in Hispanic/Latino and overweight/obese students.6

Relationship to Other Illnesses

There is significant debate whether ON is a single syndrome, a variance of other syndromes, or a behavioral and culturally influenced attitude.7,8 Although ON may lead to or be comorbid with anorexia nervosa (AN) or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), subtle differences exist between ON and these conditions.

To meet DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for AN, patients must weigh below minimally normal weight for their height and age, have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, and have a disturbed experience of their weight or body shape or cannot recognize the severity of the low weight.2 In contrast, an individual with ON may possess normal or low-normal weight. Patients with AN focus on food quantity, while patients with ON tend to focus on food quality. As summarized by Bratman, “People are ashamed of their anorexia, but they actively evangelize their orthorexia. People with anorexia skip meals; people with orthorexia do not (unless they are fasting). Those with anorexia focus only on avoiding foods, while those with orthorexia both avoid foods they think are bad and embrace foods they think are super-healthy.”9

Similarities between ON and OCD include anxiety, a need to exert control, and perfectionism. However, patients with OCD tend to report distress from compulsive behavior and a desire to change, thus exhibiting insight into their illness.8,10 Similarities between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and ON include perfectionism, rigid thinking, excessive devotion, hypermorality, and a preoccupation with details and perceived rules.11

While no studies have yet described ON as a feature of somatoform disorders, some experts have hypothesized that preoccupation with illness in a patient with somatization disorder may engender a preoccupation with food and diet as a way to combat either real or perceived illness.11 Finally, there is a report of ON associated with the prodromal phase of schizophrenia, and the development of ON may increase risk for future psychotic disorders.11,12

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of ON is unknown, though it is likely multifactorial. Individuals with ON have neurocognitive deficits similar to those seen in patients with AN and OCD, including impairments in set-shifting (flexible problem solving), external attention, and working memory.11,13 Given these cognitive deficits as well as similar symptomatology, there may be analogous brain dysfunction in patients with ON and AN or OCD. Neuroimaging studies of patients with AN have revealed dysregulation of dopamine transmission in the reward circuitry of the ventral striatum and the food regulatory mechanism in the hypothalamus.14

Dysmorphology of and dysfunction in neural circuitry, particularly the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical pathway, have been implicated in OCD.15 Neuroimaging studies have revealed increased volume and activation of the orbitofrontal cortex, which may be associated with obsessions and difficulty with extinction recall.14,15 In contrast, decreased volume and activity of the thalamus may impair its ability to inhibit the orbitofrontal cortex.15,16 Decreased volume and activity of the cingulate gyrus may be associated with difficulty in error monitoring and fear conditioning, while overactivation of the parietal lobe and cerebellum may be associated with compulsive behaviors.15,16

Risk Factors

Factors that contribute to the development of AN and possibly ON include development of food preferences, inherited differences in taste perception, food neophobia or pickiness, being premorbidly overweight or obese, parental feeding practices, and a history of parental eating disorders.14 One survey associated orthorexic tendencies with perfectionism, appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, self-classified weight, and fearful and dismissing attachment styles.17 Significant predictors of ON included overweight preoccupation, appearance orientation, and a history of an eating disorder.17

Treatment

In contrast to patients with AN, patients with ON may be easily amenable to treatment, given their pursuit of and emphasis on wellness.18 Experts recommend a multidisciplinary team approach that includes physicians, psychotherapists, and dieticians.11 Treatment may be undertaken in an outpatient setting, but hospitalization for refeeding is recommended in cases with significant weight loss or malnourishment.11 Physical examination and laboratory studies are warranted, as excessive dietary restrictions can lead to weight loss and medical complications similar to those seen in AN, including osteopenia, anemia, hyponatremia, pancytopenia, bradycardia, and even pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum.19-21