User login

Weight loss by obese women linked to perinatal improvements

SAN DIEGO – Among obese women, weight loss, stable weight, or weight gain below Institute of Medicine guidelines may result in more favorable or similar perinatal outcomes, compared with weight gain within IOM guidelines, but not for small for gestational age, results from a retrospective cohort study showed.

“This study adds to the limited body of evidence regarding associations of low weight gain and perinatal outcomes among obese women,” Emilia G. Wilkins, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “This is the first study that uses data collected after the 2009 IOM guidelines were published. Although there have been some studies published after that time, they used older cohorts. We have a large, diverse cohort and had access to robust electronic health records, which allowed for inclusion of multiple relevant covariates.”

Dr. Wilkins, a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported that 59% of obese women gained weight above the IOM guidelines and that gestational weight gain above the IOM guidelines was consistently associated with worse perinatal outcomes.

Among class III obese women (BMI of 40 or greater), gestational weight gain below –2 kg, compared with gestational weight gain within IOM guidelines, was associated with lower odds of large-for-gestational-age infants (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3–0.7), preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9), cesarean section (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7), NICU admission (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–1.1), and length of stay greater than 3 days (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.8), but higher odds of small for gestational age (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.11–6.20). Findings were similar for other obesity classes.

“It is surprising that the protective associations for weight loss were so strong,” Dr. Wilkins said. “At least 50% lower odds of adverse outcomes [were seen], including large for gestational age, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and extended neonatal hospital stay – all of which are clinically significant and could have a major implications for maternal and child health. The degree of increased odds (2- to 2.7-fold higher) of small for gestational age was also a surprising finding and indicates the need to further assess whether the health of the small-for-gestational-age babies differed across the gestational weight gain categories.”

One surprise was that, although the weight loss group had higher odds of delivering a small for gestational age infant, there was no association with increased NICU admission or increased neonatal hospital stay,” Dr. Wilkins added.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that approximately 10% of the prepregnancy weights were self-measured. Additionally, there was low statistical power to evaluate NICU and length of stay data, and maternal conditions associated with prior weight loss such as bariatric surgery were not evaluated.

Dr. Wilkins reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Among obese women, weight loss, stable weight, or weight gain below Institute of Medicine guidelines may result in more favorable or similar perinatal outcomes, compared with weight gain within IOM guidelines, but not for small for gestational age, results from a retrospective cohort study showed.

“This study adds to the limited body of evidence regarding associations of low weight gain and perinatal outcomes among obese women,” Emilia G. Wilkins, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “This is the first study that uses data collected after the 2009 IOM guidelines were published. Although there have been some studies published after that time, they used older cohorts. We have a large, diverse cohort and had access to robust electronic health records, which allowed for inclusion of multiple relevant covariates.”

Dr. Wilkins, a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported that 59% of obese women gained weight above the IOM guidelines and that gestational weight gain above the IOM guidelines was consistently associated with worse perinatal outcomes.

Among class III obese women (BMI of 40 or greater), gestational weight gain below –2 kg, compared with gestational weight gain within IOM guidelines, was associated with lower odds of large-for-gestational-age infants (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3–0.7), preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9), cesarean section (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7), NICU admission (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–1.1), and length of stay greater than 3 days (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.8), but higher odds of small for gestational age (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.11–6.20). Findings were similar for other obesity classes.

“It is surprising that the protective associations for weight loss were so strong,” Dr. Wilkins said. “At least 50% lower odds of adverse outcomes [were seen], including large for gestational age, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and extended neonatal hospital stay – all of which are clinically significant and could have a major implications for maternal and child health. The degree of increased odds (2- to 2.7-fold higher) of small for gestational age was also a surprising finding and indicates the need to further assess whether the health of the small-for-gestational-age babies differed across the gestational weight gain categories.”

One surprise was that, although the weight loss group had higher odds of delivering a small for gestational age infant, there was no association with increased NICU admission or increased neonatal hospital stay,” Dr. Wilkins added.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that approximately 10% of the prepregnancy weights were self-measured. Additionally, there was low statistical power to evaluate NICU and length of stay data, and maternal conditions associated with prior weight loss such as bariatric surgery were not evaluated.

Dr. Wilkins reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Among obese women, weight loss, stable weight, or weight gain below Institute of Medicine guidelines may result in more favorable or similar perinatal outcomes, compared with weight gain within IOM guidelines, but not for small for gestational age, results from a retrospective cohort study showed.

“This study adds to the limited body of evidence regarding associations of low weight gain and perinatal outcomes among obese women,” Emilia G. Wilkins, MD, the lead study author, said in an interview prior to the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. “This is the first study that uses data collected after the 2009 IOM guidelines were published. Although there have been some studies published after that time, they used older cohorts. We have a large, diverse cohort and had access to robust electronic health records, which allowed for inclusion of multiple relevant covariates.”

Dr. Wilkins, a fourth-year ob.gyn. resident at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif., reported that 59% of obese women gained weight above the IOM guidelines and that gestational weight gain above the IOM guidelines was consistently associated with worse perinatal outcomes.

Among class III obese women (BMI of 40 or greater), gestational weight gain below –2 kg, compared with gestational weight gain within IOM guidelines, was associated with lower odds of large-for-gestational-age infants (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3–0.7), preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9), cesarean section (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7), NICU admission (OR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–1.1), and length of stay greater than 3 days (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.8), but higher odds of small for gestational age (OR, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.11–6.20). Findings were similar for other obesity classes.

“It is surprising that the protective associations for weight loss were so strong,” Dr. Wilkins said. “At least 50% lower odds of adverse outcomes [were seen], including large for gestational age, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia/eclampsia, and extended neonatal hospital stay – all of which are clinically significant and could have a major implications for maternal and child health. The degree of increased odds (2- to 2.7-fold higher) of small for gestational age was also a surprising finding and indicates the need to further assess whether the health of the small-for-gestational-age babies differed across the gestational weight gain categories.”

One surprise was that, although the weight loss group had higher odds of delivering a small for gestational age infant, there was no association with increased NICU admission or increased neonatal hospital stay,” Dr. Wilkins added.

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that approximately 10% of the prepregnancy weights were self-measured. Additionally, there was low statistical power to evaluate NICU and length of stay data, and maternal conditions associated with prior weight loss such as bariatric surgery were not evaluated.

Dr. Wilkins reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ACOG 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among class III obese women, gestational weight gain below –2 kg, compared with gestational weight gain within IOM guidelines, was associated with lower odds of large-for-gestational-age infants (OR, 0.4), preeclampsia/eclampsia (OR, 0.5), cesarean section (OR, 0.5), NICU admission (OR, 0.7), and length of stay greater than 3 days (OR, 0.5), but higher odds of small for gestational age (OR, 2.61).

Data source: A retrospective cohort analysis of 19,810 obese women who delivered singleton, live births greater than 35 weeks between 2009 and 2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Wilkins reported having no financial disclosures.

What PCP-Related Factors Contribute to Successful Weight Loss Among Positive Deviant Low-Income African-American Women?

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate factors related to interactions with primary care physicians (PCPs) that may contribute to successful weight loss and maintenance among low-income, African-American women.

Design. Mixed methods, positive deviance framework.

Setting and participants. Participants were African-American women aged 18–64 years from an urban university-based family medicine practice who received Medicaid, resided in Philadelphia, and had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30kg/m2. From among these, “positive deviant” cases were identified as patients with EMR-confirmed weight loss of at least 10% of patient’s maximum weight between 2007–2012 and maintenance of this loss for at least 6 months. Controls were defined as patients who had not lost a significant amount of weight during this time period. Patients were excluded if they were an amputee or wheelchair-bound; had bariatric surgery, severe illness during weight loss, EMR-documented unintended weight loss, pregnancy at time of weight loss, a psychiatric disorder or were taking antipsychotic medication; had an intellectual disability; or could not give consent to participate.

Main outcomes measures. PCP- and patient-reported weight variables were collected through the EMR (documentation of dietary counseling by PCP, documentation of a weight-related problem, diagnosis of overweight, obesity, or morbid obesity on the problem list), surveys (additional predicters of positive deviant membership, including patient-reported weight-related diagnosis or discussion of weight with PCP or health professional), and interviews. Logistic regression was used to determine whether a priori-identified EMR and survey variables could predict positive deviant group membership, adjusting for demographic variables significantly associated with the outcome of interest or hypothesized to be confounders of the associations between predictors and outcomes (results were adjusted for age in the EMR analysis and for employment status and education level in the survey analysis). Once thematic saturation was reached, interviews were analyzed by a 4-member coding panel using a modified approach to grounded theory to identify themes.

Main results. For the EMR analysis, data from 161 positive deviant cases and 602 controls were analyzed. For the survey analysis, data from 35 positive deviant cases and 36 controls matched for age and maximum BMI were analyzed. For in-depth interviews, thematic saturation was reached after collecting data from 20 positive deviant participants. In the EMR analyses, documentation of dietary counseling and a weight-related diagnosis were significant predictors of positive deviant membership after adjusting for age (P < 0.001 and P = 0.011, respectively). However, documentation of obesity on the problem list was predictive of control group membership (P = 0.032). In the survey analysis, neither patient-reported weight-related diagnosis nor discussion of weight with a medical provider were predictors of positive deviant membership (P = 0.890 and P = 0.373, respectively). In the qualitative analysis of interviews with positive deviant participants, 5 themes emerged: (1) framing the problem of obesity in the context of other health problems provided motivation; (2) having a full discussion around weight management was important; (3) an ongoing conversation and relationship was valuable; (4) celebrating small successes was beneficial for ongoing motivation; and (5) advice was helpful but self-motivation was required in order to make a change.

Conclusions. PCP counseling may be an important factor in promoting weight loss in low-income, African-American women, a population at high risk for obesity. Patients may benefit from their PCPs drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions and enhancing intrinsic motivation for weight loss.

Commentary

The increasing prevalence and clinical consequences of having obesity are well-documented, with low-income minorities disproportionately burdened by this condition [1,2]. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) recommends that all patients be screened for obesity and offered intensive lifestyle counseling [3], yet evidence-based guidelines for best approaches to incorporate this into practice are few and unclear, and even fewer are specific to high-risk patient populations [4–9].

This study adds to the literature by using a positive deviance approach to identify PCP-related factors that predict successful weight loss among low-income African-American women. This approach has rarely been used in the obesity literature. In a few childhood obesity studies, this approach was used to identify motivations used by child “positive outliers” to improve their BMI [10], characterize variations of feeding and activity practices by parents of healthy children normally at high risk for obesity [11], and explore successful health and BMI reduction strategies used among positive outlier families [12]. Positive deviance has also been used to characterize and change nutritional behavior and understand successful weight-control practices among adults [13–15]. One study has suggested that studying “positive deviant” physicians that regularly provide weight counseling may help to provide practice methods to increase these practices in the primary care settings [16].

Thus, the study approach in using a positive deviance framework is an important and unique strength. Addi-tionally, the authors used a mixed-methods approach, analyzing EMR, survey, and interview data to assess PCP- and patient-reported weight-related factors that predict successful weight loss. As the authors describe, their results confirm findings from previous studies looking at counseling preferences among ethnic minority women and PCP attitudes and practices related to weight management.

They acknowledge important limitations of their study design, primarily the generalizability of findings only to urban, low-income, African-American women, the small sample size in the survey analysis, and the use of EMR data to collect data on PCP counseling (as opposed to interviews, for example). It important to also acknowledge that this study was conducted at a family medicine practice, and physician behavior and practices likely do not generalize to other PCPs and specialists. Additionally, while their intention was to use a positive deviance framework, conducting interviews among a subset of their control cases may have provided useful information regarding negative or ineffective PCP interactions regarding weight loss and management.

Applications for Clinical Practice

As the authors emphasize, the outcomes of this study are especially relevant for PCPs and other health practitioners, as the identified themes can help guide weight counseling that incorporates patient preferences and promotes successful weight loss. Importantly, these findings underscore that the role of the physician is important in promoting weight loss, yet it does not require in-depth knowledge and training in evidence-based weight loss strategies. While dietary counseling is still helpful, patients with successful weight loss value the supportive relationship with their physician, their physician drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions, and their physician enhancing intrinsic motivations for weight loss.

1. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284.

2. Williams EP, Mesidor M, Winters K, et al. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Curr Obes Rep 2015;4:363–70.

3. Moyer VA. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:373–8.

4. Ogunleye AA, Osunlana A, Asselin J, et al. The 5As team intervention: bridging the knowledge gap in obesity management among primary care practitioners. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:810.

5. Jay MR, Gillespie CC, Schlair SL, et al. The impact of primary care resident physician training on patient weight loss at 12 months. Obesity 2013;21:45–50.

6. Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2492–500.

7. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

8. Ossolinski G, Jiwa M, McManus A. Weight management practices and evidence for weight loss through primary care: a brief review. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:2011–20.

9. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1969–79.

10. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman RE, et al. Engaging children in the development of obesity interventions: Exploring outcomes that matter most among obesity positive outliers. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1393–401.

11. Foster BA, Farragher J, Parker P, Hale DE. A positive deviance approach to early childhood obesity: cross-sectional characterization of positive outliers. Child Obes 2015;11:281–8.

12. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman R, et al. Exploring innovative approaches and patient-centered outcomes from positive outliers in childhood obesity. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:646–55.

13. Stuckey HL, Boan J, Kraschnewski JL, et al. Using positive deviance for determining successful weight-control practices. Qual Health Res 2011;21:563–79.

14. Marty L, Dubois C, Gaubard MS, et al. Higher nutritional quality at no additional cost among low-income households: insights from food purchases of positive deviants. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:190–8.

15. Machado JC, Cotta RMM, Silva LS da. [The positive deviance approach to change nutrition behavior: a systematic review]. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2014;36:134–40.

16. Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Pollak KI, et al. The epidemiology of weight counseling for adults in the United States: a case of positive deviance. Int J Obes 2013;37:751–3.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate factors related to interactions with primary care physicians (PCPs) that may contribute to successful weight loss and maintenance among low-income, African-American women.

Design. Mixed methods, positive deviance framework.

Setting and participants. Participants were African-American women aged 18–64 years from an urban university-based family medicine practice who received Medicaid, resided in Philadelphia, and had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30kg/m2. From among these, “positive deviant” cases were identified as patients with EMR-confirmed weight loss of at least 10% of patient’s maximum weight between 2007–2012 and maintenance of this loss for at least 6 months. Controls were defined as patients who had not lost a significant amount of weight during this time period. Patients were excluded if they were an amputee or wheelchair-bound; had bariatric surgery, severe illness during weight loss, EMR-documented unintended weight loss, pregnancy at time of weight loss, a psychiatric disorder or were taking antipsychotic medication; had an intellectual disability; or could not give consent to participate.

Main outcomes measures. PCP- and patient-reported weight variables were collected through the EMR (documentation of dietary counseling by PCP, documentation of a weight-related problem, diagnosis of overweight, obesity, or morbid obesity on the problem list), surveys (additional predicters of positive deviant membership, including patient-reported weight-related diagnosis or discussion of weight with PCP or health professional), and interviews. Logistic regression was used to determine whether a priori-identified EMR and survey variables could predict positive deviant group membership, adjusting for demographic variables significantly associated with the outcome of interest or hypothesized to be confounders of the associations between predictors and outcomes (results were adjusted for age in the EMR analysis and for employment status and education level in the survey analysis). Once thematic saturation was reached, interviews were analyzed by a 4-member coding panel using a modified approach to grounded theory to identify themes.

Main results. For the EMR analysis, data from 161 positive deviant cases and 602 controls were analyzed. For the survey analysis, data from 35 positive deviant cases and 36 controls matched for age and maximum BMI were analyzed. For in-depth interviews, thematic saturation was reached after collecting data from 20 positive deviant participants. In the EMR analyses, documentation of dietary counseling and a weight-related diagnosis were significant predictors of positive deviant membership after adjusting for age (P < 0.001 and P = 0.011, respectively). However, documentation of obesity on the problem list was predictive of control group membership (P = 0.032). In the survey analysis, neither patient-reported weight-related diagnosis nor discussion of weight with a medical provider were predictors of positive deviant membership (P = 0.890 and P = 0.373, respectively). In the qualitative analysis of interviews with positive deviant participants, 5 themes emerged: (1) framing the problem of obesity in the context of other health problems provided motivation; (2) having a full discussion around weight management was important; (3) an ongoing conversation and relationship was valuable; (4) celebrating small successes was beneficial for ongoing motivation; and (5) advice was helpful but self-motivation was required in order to make a change.

Conclusions. PCP counseling may be an important factor in promoting weight loss in low-income, African-American women, a population at high risk for obesity. Patients may benefit from their PCPs drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions and enhancing intrinsic motivation for weight loss.

Commentary

The increasing prevalence and clinical consequences of having obesity are well-documented, with low-income minorities disproportionately burdened by this condition [1,2]. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) recommends that all patients be screened for obesity and offered intensive lifestyle counseling [3], yet evidence-based guidelines for best approaches to incorporate this into practice are few and unclear, and even fewer are specific to high-risk patient populations [4–9].

This study adds to the literature by using a positive deviance approach to identify PCP-related factors that predict successful weight loss among low-income African-American women. This approach has rarely been used in the obesity literature. In a few childhood obesity studies, this approach was used to identify motivations used by child “positive outliers” to improve their BMI [10], characterize variations of feeding and activity practices by parents of healthy children normally at high risk for obesity [11], and explore successful health and BMI reduction strategies used among positive outlier families [12]. Positive deviance has also been used to characterize and change nutritional behavior and understand successful weight-control practices among adults [13–15]. One study has suggested that studying “positive deviant” physicians that regularly provide weight counseling may help to provide practice methods to increase these practices in the primary care settings [16].

Thus, the study approach in using a positive deviance framework is an important and unique strength. Addi-tionally, the authors used a mixed-methods approach, analyzing EMR, survey, and interview data to assess PCP- and patient-reported weight-related factors that predict successful weight loss. As the authors describe, their results confirm findings from previous studies looking at counseling preferences among ethnic minority women and PCP attitudes and practices related to weight management.

They acknowledge important limitations of their study design, primarily the generalizability of findings only to urban, low-income, African-American women, the small sample size in the survey analysis, and the use of EMR data to collect data on PCP counseling (as opposed to interviews, for example). It important to also acknowledge that this study was conducted at a family medicine practice, and physician behavior and practices likely do not generalize to other PCPs and specialists. Additionally, while their intention was to use a positive deviance framework, conducting interviews among a subset of their control cases may have provided useful information regarding negative or ineffective PCP interactions regarding weight loss and management.

Applications for Clinical Practice

As the authors emphasize, the outcomes of this study are especially relevant for PCPs and other health practitioners, as the identified themes can help guide weight counseling that incorporates patient preferences and promotes successful weight loss. Importantly, these findings underscore that the role of the physician is important in promoting weight loss, yet it does not require in-depth knowledge and training in evidence-based weight loss strategies. While dietary counseling is still helpful, patients with successful weight loss value the supportive relationship with their physician, their physician drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions, and their physician enhancing intrinsic motivations for weight loss.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate factors related to interactions with primary care physicians (PCPs) that may contribute to successful weight loss and maintenance among low-income, African-American women.

Design. Mixed methods, positive deviance framework.

Setting and participants. Participants were African-American women aged 18–64 years from an urban university-based family medicine practice who received Medicaid, resided in Philadelphia, and had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30kg/m2. From among these, “positive deviant” cases were identified as patients with EMR-confirmed weight loss of at least 10% of patient’s maximum weight between 2007–2012 and maintenance of this loss for at least 6 months. Controls were defined as patients who had not lost a significant amount of weight during this time period. Patients were excluded if they were an amputee or wheelchair-bound; had bariatric surgery, severe illness during weight loss, EMR-documented unintended weight loss, pregnancy at time of weight loss, a psychiatric disorder or were taking antipsychotic medication; had an intellectual disability; or could not give consent to participate.

Main outcomes measures. PCP- and patient-reported weight variables were collected through the EMR (documentation of dietary counseling by PCP, documentation of a weight-related problem, diagnosis of overweight, obesity, or morbid obesity on the problem list), surveys (additional predicters of positive deviant membership, including patient-reported weight-related diagnosis or discussion of weight with PCP or health professional), and interviews. Logistic regression was used to determine whether a priori-identified EMR and survey variables could predict positive deviant group membership, adjusting for demographic variables significantly associated with the outcome of interest or hypothesized to be confounders of the associations between predictors and outcomes (results were adjusted for age in the EMR analysis and for employment status and education level in the survey analysis). Once thematic saturation was reached, interviews were analyzed by a 4-member coding panel using a modified approach to grounded theory to identify themes.

Main results. For the EMR analysis, data from 161 positive deviant cases and 602 controls were analyzed. For the survey analysis, data from 35 positive deviant cases and 36 controls matched for age and maximum BMI were analyzed. For in-depth interviews, thematic saturation was reached after collecting data from 20 positive deviant participants. In the EMR analyses, documentation of dietary counseling and a weight-related diagnosis were significant predictors of positive deviant membership after adjusting for age (P < 0.001 and P = 0.011, respectively). However, documentation of obesity on the problem list was predictive of control group membership (P = 0.032). In the survey analysis, neither patient-reported weight-related diagnosis nor discussion of weight with a medical provider were predictors of positive deviant membership (P = 0.890 and P = 0.373, respectively). In the qualitative analysis of interviews with positive deviant participants, 5 themes emerged: (1) framing the problem of obesity in the context of other health problems provided motivation; (2) having a full discussion around weight management was important; (3) an ongoing conversation and relationship was valuable; (4) celebrating small successes was beneficial for ongoing motivation; and (5) advice was helpful but self-motivation was required in order to make a change.

Conclusions. PCP counseling may be an important factor in promoting weight loss in low-income, African-American women, a population at high risk for obesity. Patients may benefit from their PCPs drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions and enhancing intrinsic motivation for weight loss.

Commentary

The increasing prevalence and clinical consequences of having obesity are well-documented, with low-income minorities disproportionately burdened by this condition [1,2]. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPTF) recommends that all patients be screened for obesity and offered intensive lifestyle counseling [3], yet evidence-based guidelines for best approaches to incorporate this into practice are few and unclear, and even fewer are specific to high-risk patient populations [4–9].

This study adds to the literature by using a positive deviance approach to identify PCP-related factors that predict successful weight loss among low-income African-American women. This approach has rarely been used in the obesity literature. In a few childhood obesity studies, this approach was used to identify motivations used by child “positive outliers” to improve their BMI [10], characterize variations of feeding and activity practices by parents of healthy children normally at high risk for obesity [11], and explore successful health and BMI reduction strategies used among positive outlier families [12]. Positive deviance has also been used to characterize and change nutritional behavior and understand successful weight-control practices among adults [13–15]. One study has suggested that studying “positive deviant” physicians that regularly provide weight counseling may help to provide practice methods to increase these practices in the primary care settings [16].

Thus, the study approach in using a positive deviance framework is an important and unique strength. Addi-tionally, the authors used a mixed-methods approach, analyzing EMR, survey, and interview data to assess PCP- and patient-reported weight-related factors that predict successful weight loss. As the authors describe, their results confirm findings from previous studies looking at counseling preferences among ethnic minority women and PCP attitudes and practices related to weight management.

They acknowledge important limitations of their study design, primarily the generalizability of findings only to urban, low-income, African-American women, the small sample size in the survey analysis, and the use of EMR data to collect data on PCP counseling (as opposed to interviews, for example). It important to also acknowledge that this study was conducted at a family medicine practice, and physician behavior and practices likely do not generalize to other PCPs and specialists. Additionally, while their intention was to use a positive deviance framework, conducting interviews among a subset of their control cases may have provided useful information regarding negative or ineffective PCP interactions regarding weight loss and management.

Applications for Clinical Practice

As the authors emphasize, the outcomes of this study are especially relevant for PCPs and other health practitioners, as the identified themes can help guide weight counseling that incorporates patient preferences and promotes successful weight loss. Importantly, these findings underscore that the role of the physician is important in promoting weight loss, yet it does not require in-depth knowledge and training in evidence-based weight loss strategies. While dietary counseling is still helpful, patients with successful weight loss value the supportive relationship with their physician, their physician drawing connections between obesity and weight-related medical conditions, and their physician enhancing intrinsic motivations for weight loss.

1. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284.

2. Williams EP, Mesidor M, Winters K, et al. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Curr Obes Rep 2015;4:363–70.

3. Moyer VA. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:373–8.

4. Ogunleye AA, Osunlana A, Asselin J, et al. The 5As team intervention: bridging the knowledge gap in obesity management among primary care practitioners. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:810.

5. Jay MR, Gillespie CC, Schlair SL, et al. The impact of primary care resident physician training on patient weight loss at 12 months. Obesity 2013;21:45–50.

6. Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2492–500.

7. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

8. Ossolinski G, Jiwa M, McManus A. Weight management practices and evidence for weight loss through primary care: a brief review. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:2011–20.

9. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1969–79.

10. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman RE, et al. Engaging children in the development of obesity interventions: Exploring outcomes that matter most among obesity positive outliers. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1393–401.

11. Foster BA, Farragher J, Parker P, Hale DE. A positive deviance approach to early childhood obesity: cross-sectional characterization of positive outliers. Child Obes 2015;11:281–8.

12. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman R, et al. Exploring innovative approaches and patient-centered outcomes from positive outliers in childhood obesity. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:646–55.

13. Stuckey HL, Boan J, Kraschnewski JL, et al. Using positive deviance for determining successful weight-control practices. Qual Health Res 2011;21:563–79.

14. Marty L, Dubois C, Gaubard MS, et al. Higher nutritional quality at no additional cost among low-income households: insights from food purchases of positive deviants. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:190–8.

15. Machado JC, Cotta RMM, Silva LS da. [The positive deviance approach to change nutrition behavior: a systematic review]. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2014;36:134–40.

16. Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Pollak KI, et al. The epidemiology of weight counseling for adults in the United States: a case of positive deviance. Int J Obes 2013;37:751–3.

1. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284.

2. Williams EP, Mesidor M, Winters K, et al. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Curr Obes Rep 2015;4:363–70.

3. Moyer VA. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:373–8.

4. Ogunleye AA, Osunlana A, Asselin J, et al. The 5As team intervention: bridging the knowledge gap in obesity management among primary care practitioners. BMC Res Notes 2015;8:810.

5. Jay MR, Gillespie CC, Schlair SL, et al. The impact of primary care resident physician training on patient weight loss at 12 months. Obesity 2013;21:45–50.

6. Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet 2016;388:2492–500.

7. Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocr Pract 2016;22(Suppl 3):1–203.

8. Ossolinski G, Jiwa M, McManus A. Weight management practices and evidence for weight loss through primary care: a brief review. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:2011–20.

9. Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer DB, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1969–79.

10. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman RE, et al. Engaging children in the development of obesity interventions: Exploring outcomes that matter most among obesity positive outliers. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:1393–401.

11. Foster BA, Farragher J, Parker P, Hale DE. A positive deviance approach to early childhood obesity: cross-sectional characterization of positive outliers. Child Obes 2015;11:281–8.

12. Sharifi M, Marshall G, Goldman R, et al. Exploring innovative approaches and patient-centered outcomes from positive outliers in childhood obesity. Acad Pediatr 2014;14:646–55.

13. Stuckey HL, Boan J, Kraschnewski JL, et al. Using positive deviance for determining successful weight-control practices. Qual Health Res 2011;21:563–79.

14. Marty L, Dubois C, Gaubard MS, et al. Higher nutritional quality at no additional cost among low-income households: insights from food purchases of positive deviants. Am J Clin Nutr 2015;102:190–8.

15. Machado JC, Cotta RMM, Silva LS da. [The positive deviance approach to change nutrition behavior: a systematic review]. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2014;36:134–40.

16. Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Pollak KI, et al. The epidemiology of weight counseling for adults in the United States: a case of positive deviance. Int J Obes 2013;37:751–3.

Nontraditional med student hopes to bridge common understanding gaps in health care

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ryan Gamlin, a nontraditional student at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Ryan was chosen to present his scientific abstract at SHM’s annual meeting in 2016, and encourages medical students to utilize SHM’s resources.

Tell TH about your unique pathway to medical school. How did you become an SHM member?

After 10 years working for and consulting to large health insurance companies, I was increasingly disillusioned with my work and the insurance industry and began feeling restless. When I considered possible avenues to help improve health and the health care delivery system, nothing held more intellectual or professional appeal than working on problems from the inside as a physician.

This effort to bridge these constituencies was my introduction to SHM. I was fortunate enough to be selected for the Health Innovations Scholars Program (HISP), an incredible quality improvement (QI) and leadership development program run by the hospital medicine group at University of Colorado. Conceived by Jeff Glasheen, MD, and now led by Read Pierce, MD, and Emily Gottenborg, MD, among many others, HISP brings eight medical students together to grow their QI toolkit and build leadership skills while providing the opportunity to design and run a meaningful QI project at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz medical campus. Many involved with this program – and others within the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado – are leaders within SHM. With their encouragement, I submitted an abstract based on our HISP project and had the good fortune to share our work as a podium presentation at Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Describe your experience at your first annual meeting. Why would you encourage medical students to attend?

Hospital Medicine 2016 inspired me. As someone interested in the intersection of clinical care and the care system itself, I was amazed at the depth and breadth of forward-looking programming and the amount of similarly-inclined people!

I wish that every medical student – irrespective of their intended specialty – could attend an SHM meeting to witness firsthand how a progressive, thriving professional society integrates members at all levels (student, resident, early-career faculty, and beyond) into their work of improving health care.

As a medical student, why is SHM beneficial to your professional growth as a future physician?

I see SHM as a “big tent” professional society that values insights and expertise from all types of physicians, with tangible commitments to support them in the types of system-improving work that are important to me in my career. SHM’s member resources and commitment to students’ and residents’ professional development are incomparable.

What are the biggest opportunities you see for yourself and other future physicians in the changing health care landscape?

The days when a physician’s job was limited to doctoring are over. Our generation of physicians must be great clinicians and work to heal a sick health care system. Now more than ever, physicians must be systems thinkers, designers, and fixers, equipped with the tools of quality improvement, design thinking, finance, and health policy.

Opportunities for meaningful improvement exist at every level, from care teams to health systems, the health care industry, and policy at every level. I would encourage those at any stage of their careers to find an area that they’re excited about or interested in. Seek out information and mentors in that area at their institutions or within SHM, and just start working on something.

There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty in health care; reimbursement paradigms are changing, clinical expectations only grow, and the forces competing for every doctor’s limited time seem unlimited. Uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it also means opportunity. I’m excited to see the commitment to leadership from SHM and so many of its members. It has never been more necessary.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ryan Gamlin, a nontraditional student at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Ryan was chosen to present his scientific abstract at SHM’s annual meeting in 2016, and encourages medical students to utilize SHM’s resources.

Tell TH about your unique pathway to medical school. How did you become an SHM member?

After 10 years working for and consulting to large health insurance companies, I was increasingly disillusioned with my work and the insurance industry and began feeling restless. When I considered possible avenues to help improve health and the health care delivery system, nothing held more intellectual or professional appeal than working on problems from the inside as a physician.

This effort to bridge these constituencies was my introduction to SHM. I was fortunate enough to be selected for the Health Innovations Scholars Program (HISP), an incredible quality improvement (QI) and leadership development program run by the hospital medicine group at University of Colorado. Conceived by Jeff Glasheen, MD, and now led by Read Pierce, MD, and Emily Gottenborg, MD, among many others, HISP brings eight medical students together to grow their QI toolkit and build leadership skills while providing the opportunity to design and run a meaningful QI project at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz medical campus. Many involved with this program – and others within the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado – are leaders within SHM. With their encouragement, I submitted an abstract based on our HISP project and had the good fortune to share our work as a podium presentation at Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Describe your experience at your first annual meeting. Why would you encourage medical students to attend?

Hospital Medicine 2016 inspired me. As someone interested in the intersection of clinical care and the care system itself, I was amazed at the depth and breadth of forward-looking programming and the amount of similarly-inclined people!

I wish that every medical student – irrespective of their intended specialty – could attend an SHM meeting to witness firsthand how a progressive, thriving professional society integrates members at all levels (student, resident, early-career faculty, and beyond) into their work of improving health care.

As a medical student, why is SHM beneficial to your professional growth as a future physician?

I see SHM as a “big tent” professional society that values insights and expertise from all types of physicians, with tangible commitments to support them in the types of system-improving work that are important to me in my career. SHM’s member resources and commitment to students’ and residents’ professional development are incomparable.

What are the biggest opportunities you see for yourself and other future physicians in the changing health care landscape?

The days when a physician’s job was limited to doctoring are over. Our generation of physicians must be great clinicians and work to heal a sick health care system. Now more than ever, physicians must be systems thinkers, designers, and fixers, equipped with the tools of quality improvement, design thinking, finance, and health policy.

Opportunities for meaningful improvement exist at every level, from care teams to health systems, the health care industry, and policy at every level. I would encourage those at any stage of their careers to find an area that they’re excited about or interested in. Seek out information and mentors in that area at their institutions or within SHM, and just start working on something.

There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty in health care; reimbursement paradigms are changing, clinical expectations only grow, and the forces competing for every doctor’s limited time seem unlimited. Uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it also means opportunity. I’m excited to see the commitment to leadership from SHM and so many of its members. It has never been more necessary.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Editor’s note: Each month, SHM puts the spotlight on some of our most active members who are making substantial contributions to hospital medicine. Log on to www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved for more information on how you can lend your expertise to help SHM improve the care of hospitalized patients.

This month, The Hospitalist spotlights Ryan Gamlin, a nontraditional student at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Ryan was chosen to present his scientific abstract at SHM’s annual meeting in 2016, and encourages medical students to utilize SHM’s resources.

Tell TH about your unique pathway to medical school. How did you become an SHM member?

After 10 years working for and consulting to large health insurance companies, I was increasingly disillusioned with my work and the insurance industry and began feeling restless. When I considered possible avenues to help improve health and the health care delivery system, nothing held more intellectual or professional appeal than working on problems from the inside as a physician.

This effort to bridge these constituencies was my introduction to SHM. I was fortunate enough to be selected for the Health Innovations Scholars Program (HISP), an incredible quality improvement (QI) and leadership development program run by the hospital medicine group at University of Colorado. Conceived by Jeff Glasheen, MD, and now led by Read Pierce, MD, and Emily Gottenborg, MD, among many others, HISP brings eight medical students together to grow their QI toolkit and build leadership skills while providing the opportunity to design and run a meaningful QI project at the University of Colorado’s Anschutz medical campus. Many involved with this program – and others within the hospital medicine group at the University of Colorado – are leaders within SHM. With their encouragement, I submitted an abstract based on our HISP project and had the good fortune to share our work as a podium presentation at Hospital Medicine 2016 in San Diego.

Describe your experience at your first annual meeting. Why would you encourage medical students to attend?

Hospital Medicine 2016 inspired me. As someone interested in the intersection of clinical care and the care system itself, I was amazed at the depth and breadth of forward-looking programming and the amount of similarly-inclined people!

I wish that every medical student – irrespective of their intended specialty – could attend an SHM meeting to witness firsthand how a progressive, thriving professional society integrates members at all levels (student, resident, early-career faculty, and beyond) into their work of improving health care.

As a medical student, why is SHM beneficial to your professional growth as a future physician?

I see SHM as a “big tent” professional society that values insights and expertise from all types of physicians, with tangible commitments to support them in the types of system-improving work that are important to me in my career. SHM’s member resources and commitment to students’ and residents’ professional development are incomparable.

What are the biggest opportunities you see for yourself and other future physicians in the changing health care landscape?

The days when a physician’s job was limited to doctoring are over. Our generation of physicians must be great clinicians and work to heal a sick health care system. Now more than ever, physicians must be systems thinkers, designers, and fixers, equipped with the tools of quality improvement, design thinking, finance, and health policy.

Opportunities for meaningful improvement exist at every level, from care teams to health systems, the health care industry, and policy at every level. I would encourage those at any stage of their careers to find an area that they’re excited about or interested in. Seek out information and mentors in that area at their institutions or within SHM, and just start working on something.

There is a tremendous amount of uncertainty in health care; reimbursement paradigms are changing, clinical expectations only grow, and the forces competing for every doctor’s limited time seem unlimited. Uncertainty is uncomfortable, but it also means opportunity. I’m excited to see the commitment to leadership from SHM and so many of its members. It has never been more necessary.

Felicia Steele is SHM’s communications coordinator.

Parenting style linked to toddler sensory adaptation, behavior

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Children of parents who have a permissive parenting style were more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation at age 1 year and increased behavior difficulties at 2 years, compared to children exposed to other parenting styles, in a new, unpublished study.

Toddlers with permissive parents had more than double the risk of internalizing behaviors and triple the risk of externalizing behaviors compared to peers whose parents used an authoritative or authoritarian parenting style, reported Mary Lauren Neel, MD, a fellow in pediatrics at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. This association appeared stronger among preterm infants, but without a statistically significant increased effect.

Dr. Neel’s study tested whether children’s sensory adaptation differed according to parenting styles, as defined by the validated Baumrind’s framework of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting (Genet Psychol Monogr. 1967 Feb;75[1]:43-88). These styles are based on parents’ demandingness (whether they have developmentally appropriate expectations of their child) and responsivity (how sensitively parents perceive and respond to children’s needs), Dr. Neel explained. The majority of the children’s parents (61%) had an authoritative style, while 18% had an authoritarian style, and 11% had a permissive style.

Previous research has identified a link between abnormal sensory interactions with the environment and early behavioral problems, and preterm infants are already more likely to experience both behavioral difficulties and atypical sensory adaption than are children born at term. Dr. Neel’s research, therefore, compared 52 term infants and 51 preterm infants. The median gestational age at birth was 35 weeks, and 29% of the cohort were very preterm, born at 32 weeks or earlier. Almost all (97%) of the mothers had at least a high school education.

The researchers assessed the infants at 12 months with the Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile and at 24 months with the Child Behavior Checklist. At 12 months, after adjustment for gestational age at birth, infants of authoritative parents had greater oral sensation seeking (P = .01) and decreased sensory sensitivity (P = .02), those of authoritarian parents had increased sensation seeking (P = .04), and those of permissive parents had decreased attention to children’s visual surroundings (P = .03).

One in five (21%) of the children had an atypical neurologic threshold at 1 year, but no statistically significant association was seen between an atypical threshold and authoritarian and authoritative parenting. Neither parenting style was associated with externalizing or internalizing behaviors.

Permissive parents’ children, however, were 2.6 times more likely to have atypical sensory adaptation. Further, at 2 years, these children were 2.2 times more likely to have internalizing behaviors and 3 times more likely to have externalizing behaviors, Dr. Neel reported.

“The association between permissive parenting and abnormal sensory neurological threshold in the home environment may explain the increased risk for behavior problems in children of permissive parents at 2 years,” she said. The results were consistent among term and preterm infants with a trend toward increasing significance preterm infants.

“It’s possible that prematurity augments these dynamics, but we would need a larger sample size,” she said, adding that the potential underlying mechanisms for that association are something that future research would need to tease out.

After an audience member asked about the possibility that children’s sensory capabilities might be driving parenting style, Dr. Neel acknowledged the bidirectional relationship between parent and child but noted that most psychology research suggest parenting style has more to do with the parents than with their children.

Limitations of the study include its small size and lack of data on other potential confounding factors, such as parental mental health.

The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

AT PAS 17

Key clinical point: A permissive parenting style is associated with greater behavioral problems in children at age 2 years.

Major finding: Children of permissive parents had 2.2 times greater likelihood of internalizing behaviors and 3 times greater risk of externalizing behaviors at age 2, compared to children of parents with other styles.

Data source: A prospective observational study of 103 infants assessed at 12 and 24 months.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as well as a private grant. Dr. Neel reported having no disclosures.

Enlarging Mass on the Lateral Neck

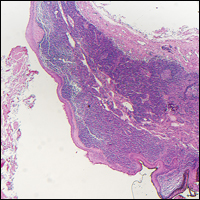

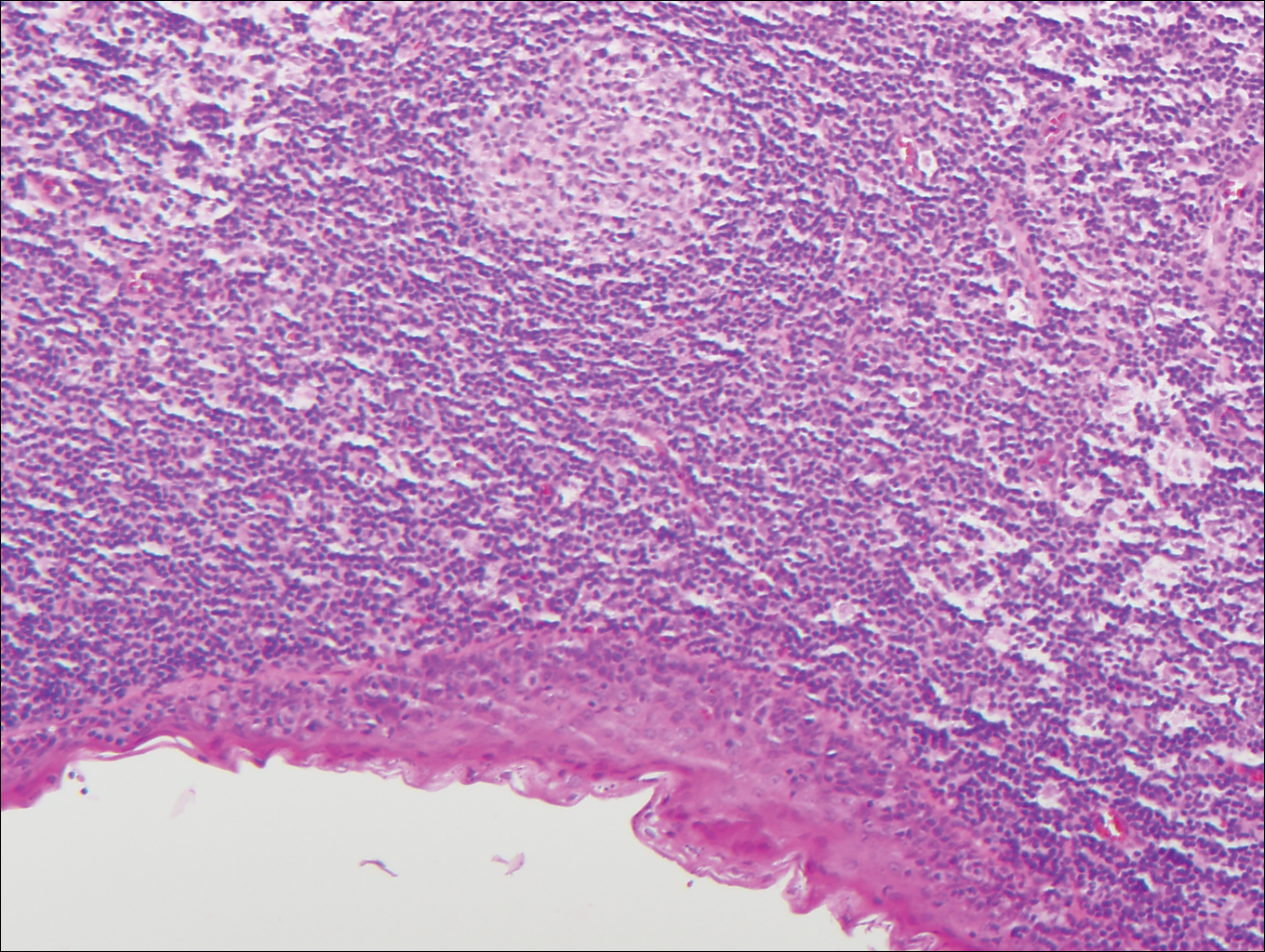

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

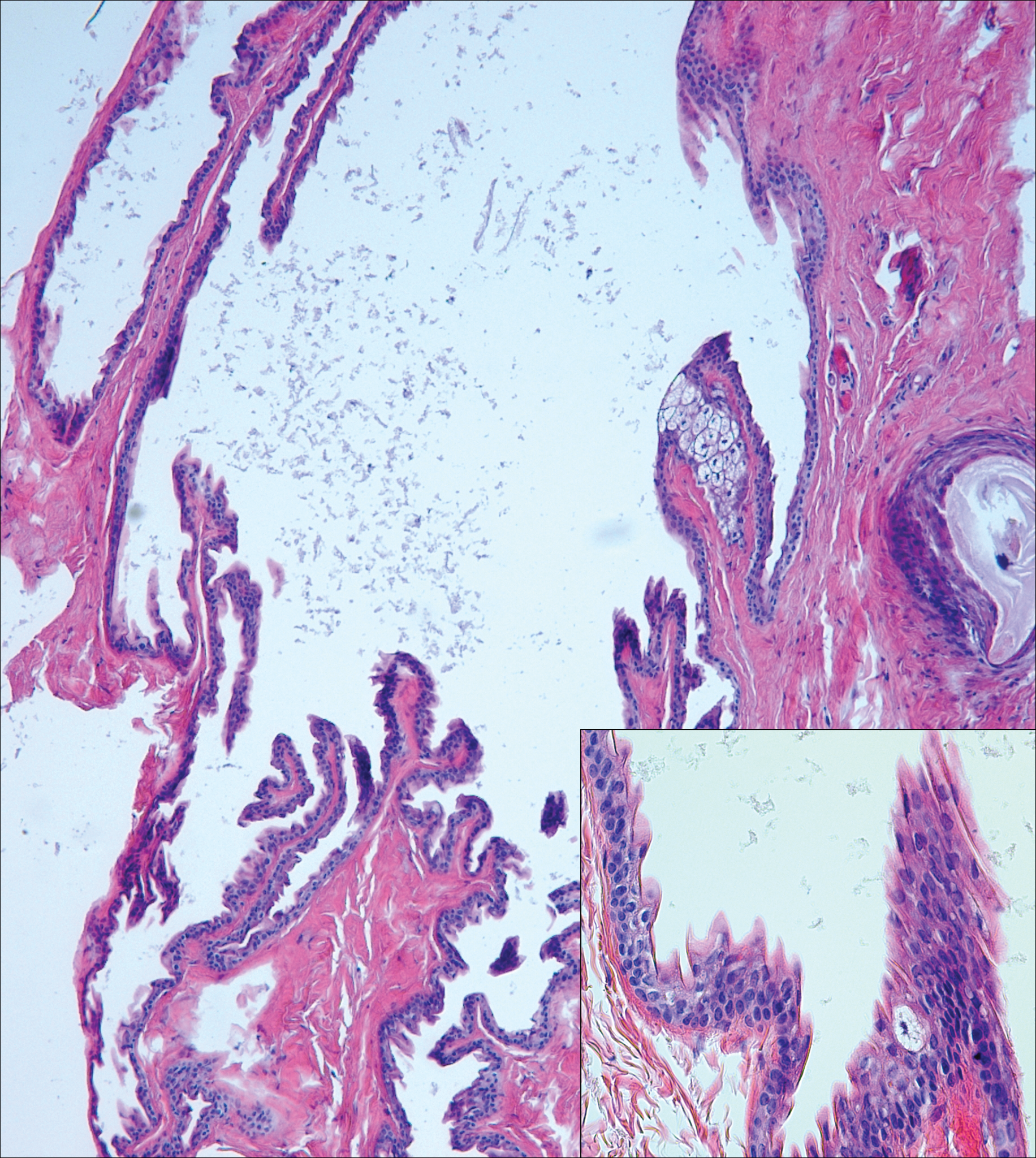

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

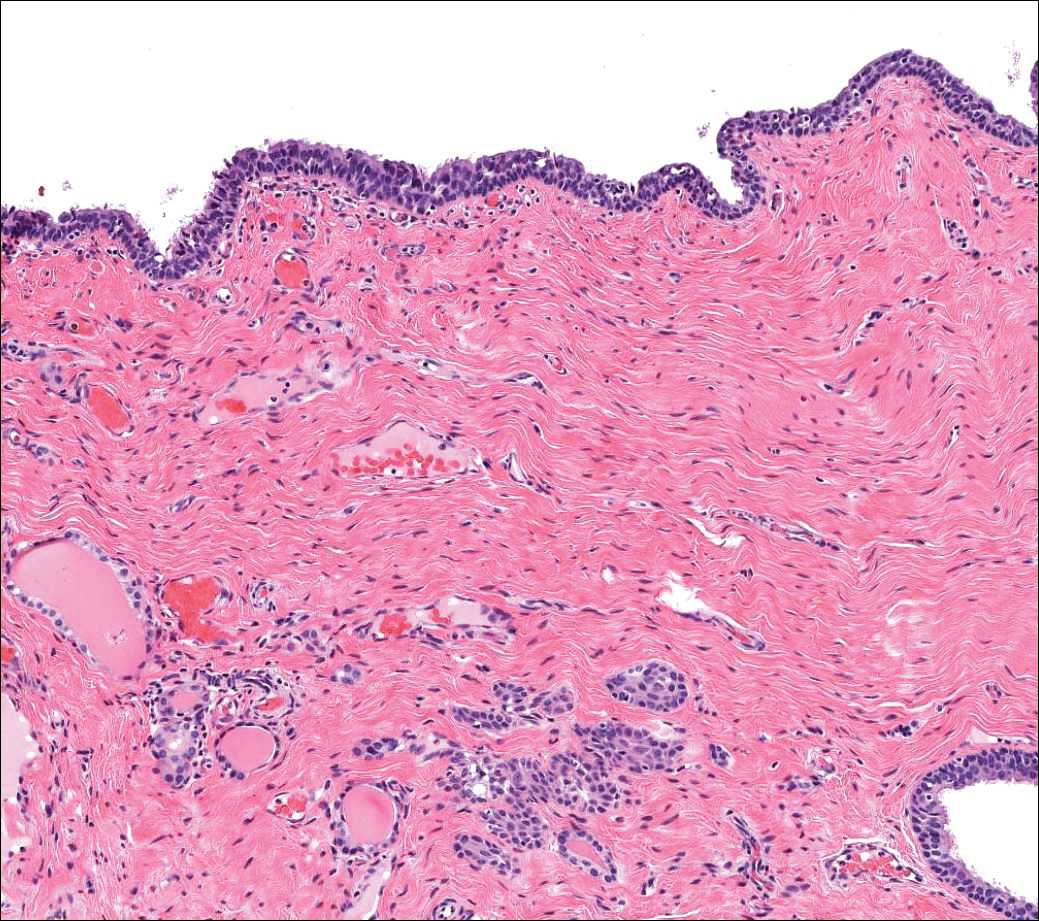

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

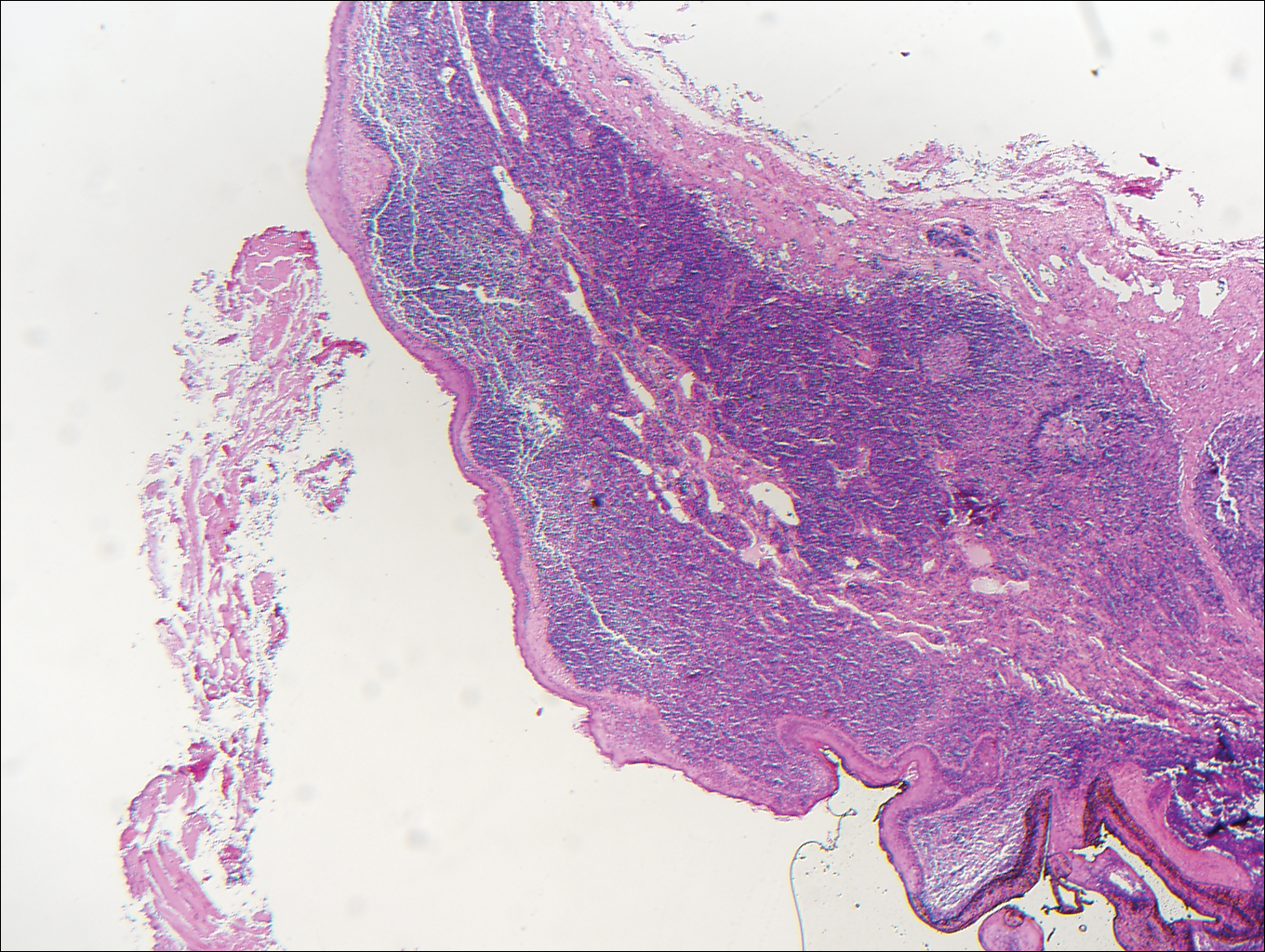

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.

- Kirkham N, Aljefri K. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Rosenbach M, et al, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:969-1024.

- Elston DM. Benign tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2014:49-55.

- Hsu CG, Heller M, Johnston GS, et al. An unusual cause of airway compromise in the emergency department: mediastinal bronchogenic cyst [published online December 13, 2016]. J Emerg Med. 2017;52:E91-E93.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

Branchial Cleft Cyst

Cystic lesions present in a myriad of ways and often require histopathologic examination for definitive diagnosis. Correct identification of the cells comprising the lining of the cyst and the composition of the surrounding tissue are utilized to classify these lesions.

Branchial cleft cysts (quiz image, Figure 1) most commonly present as a soft tissue swelling of the lateral neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid; they also can present in the preauricular or mandibular region.1,2 Although the cyst is present at birth, it typically is not clinically apparent until the second or third decades of life. The origin of branchial cleft cysts is subject to some debate; however, the prevailing theory is that they result from failure of obliteration of the second branchial arch during development.1 Histopathologically, branchial cleft cysts are characterized by a stratified squamous epithelial lining and abundant lymphoid tissue with germinal centers.3,4 Infection is a common reason for presentation and excision is curative.

Bronchogenic cysts (Figure 2) present as midline lesions in the suprasternal notch and can present clinically due to compression of the airway.5 They develop as anomalies of the primitive foregut, budding off of the tracheobronchial tree. Similar to respiratory tissue, they are lined with a ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and contain goblet cells. Concentric smooth muscle often surrounds the cyst and cartilage may be present.4 Excision is curative and recommended if the cyst encroaches on vital structures.

Median raphe cysts occur most commonly on the ventral surface of the penis on or near the glans (Figure 3). These cysts are thought to result from anomalous budding from the urethral epithelium, though they do not maintain contact with the urethra.3 The lining varies in thickness from 1 to 4 cell layers and mimics the transitional epithelium of the urethra. Amorphous debris often is seen within the cyst, and surrounding genital tissue can be appreciated by identification of delicate collagen, smooth muscle, and numerous small nerves and vessels.3,4 Excision is curative and often is sought when the cyst becomes irritated or cosmetically bothersome.

Steatocystomas can present as solitary (steatocystoma simplex) or multiple lesions (steatocystoma multiplex)(Figure 4). They present as small, well-defined, yellow cystic papules most commonly on the chest, axilla, or groin.2 Their lining is composed of a stratified squamous epithelium that lacks a granular layer and contains a distinct overlying corrugated "shark tooth" eosinophilic cuticle. Sebaceous lobules are characteristically present along or within the cyst wall.3,4 Excision is curative and treatment often is sought for cosmetic purposes.

Similar to bronchogenic cysts, thyroglossal duct cysts (Figure 5) present on the midline neck, though they characteristically move with swallowing. The thyroglossal duct develops as the thyroid migrates from the floor of the pharynx to the anterior neck. Remnants of this duct result in the thyroglossal duct cyst.2 These cysts contain a respiratory-type epithelial lining and are distinguished by distinct thyroid follicles and lymphoid aggregates surrounding the cyst wall. Unlike bronchogenic cysts, they do not contain smooth muscle.3,4 Excision is curative.

- Chavan S, Deshmukh R, Karande P, et al. Branchial cleft cyst: a case report and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:150.

- Stone MS. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012:1817-1828.