User login

Endoscopic weight loss surgery cuts costs, side effects

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

FROM DDW

Key clinical point: Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a viable option for patients seeking weight loss but wishing to avoid major surgery.

Major finding: After 1 year, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 9% of laparoscopic band placement patients.

Data source: A randomized trial of 278 obese adults who underwent one of three weight loss procedures.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

2017 Update on cervical disease

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

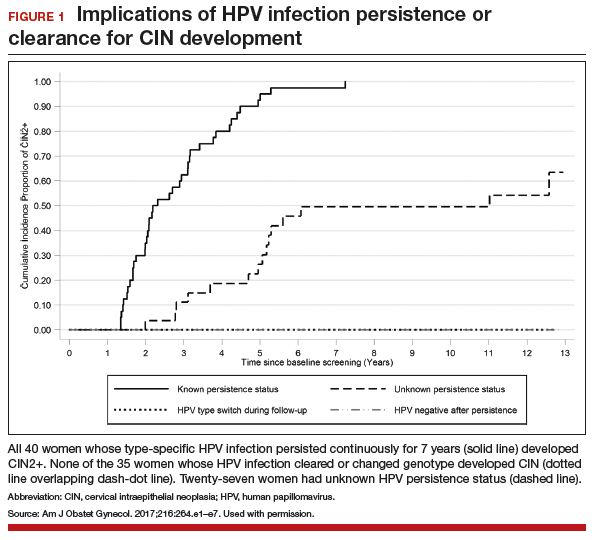

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

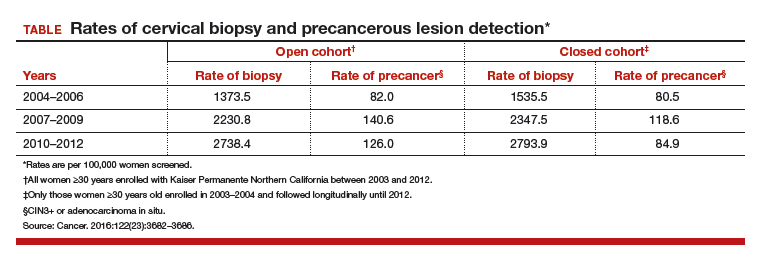

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

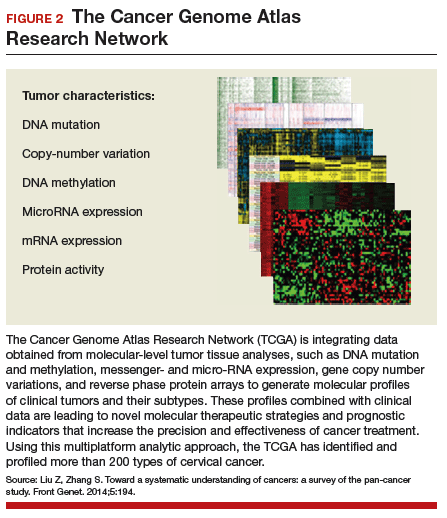

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.

The integration of data from multiple layers of analysis (FIGURE 2) is helping investigators identify variations in cancers. DNA methylation, for instance, is a means by which cells control gene expression. An analysis of this process in cervical tumor tissue has revealed additional cancer subgroups in which messenger RNA increases the transition of epithelial cells to invasive mesenchymal cells. Targeting that process in these subgroups would likely enhance the effectiveness of novel small-molecule inhibitors and some standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542.

- Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, DeFrancesco M, Thomas Cox J, Huh W. Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):311–315.

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.

The integration of data from multiple layers of analysis (FIGURE 2) is helping investigators identify variations in cancers. DNA methylation, for instance, is a means by which cells control gene expression. An analysis of this process in cervical tumor tissue has revealed additional cancer subgroups in which messenger RNA increases the transition of epithelial cells to invasive mesenchymal cells. Targeting that process in these subgroups would likely enhance the effectiveness of novel small-molecule inhibitors and some standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and periodic cervical screening have significantly decreased the incidence of invasive cervical cancer. But cancers still exist despite the availability of these useful clinical tools, especially in women of reproductive age in developing regions of the world. In the 2016 update on cervical disease, I reviewed studies on 2 promising and novel immunotherapies for cervical cancer: HPV therapeutic vaccine and adoptive T-cell therapy. This year the focus is on remarkable advances in the field of genomics and related studies that are rapidly expanding our understanding of the molecular characteristics of cervical cancer. Rewards of this research already being explored include novel immunotherapeutic agents as well as the repurposed use of existing drugs.

But first, with regard to cervical screening and follow-up, 2 recent large studies have yielded findings that have important implications for patient management. One pertains to the monitoring of women who have persistent infection with high-risk HPV but cytology results that are negative. Its conclusion was unequivocal and very useful in the management of our patients. The other study tracked HPV screening performed every 3 years and reported on the diagnostic efficiency of this shorter interval screening strategy.

Read about persistent HPV infection and CIN

Persistent HPV infection has a higher risk than most clinicians might think

Elfgren K, Elfström KM, Naucler P, Arnheim-Dahlström L, Dillner J. Management of women with human papillomavirus persistence: long-term follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):264.e1-e7.

It is well known that most cases of cervical cancer arise from persistent HPV infection, with the highest percentage of cancers caused by high-risk types 16 or 18. What has been uncertain, however, is the actual degree of risk that persistent infection confers over time for the development of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or worse when a woman's repeated cytology reports are negative. In an analysis of a long-term double-blind, randomized, controlled screening study, Elfgren and colleagues showed that all women whose HPV infection persisted up to 7 years developed CIN grade 2 (CIN2+), while those whose infection cleared in that period, or changed genotype, had no precancerous lesions out to 13 years of follow-up.

Related Article:

It is time for HPV vaccination to be considered part of routine preventive health care

Details of the study

Between 1997 and 2000, 12,527 Swedish women between the ages of 32 and 38 years who were undergoing organized cervical cancer screening agreed to participate in a 1:1-randomized prospective trial to determine the benefit of screening with HPV and cytology (intervention group) compared with cytology screening alone (control group). However, brush sampling for HPV was performed even on women in the control group, with the samples frozen for later testing. All participants were identified in the Swedish National Cervical Screening Registry.

Women in the intervention group who initially tested positive for HPV but whose cytology test results were negative (n = 341) were invited to return a year later for repeat HPV testing; 270 women returned and 119 had type-specific HPV persistence. Of those with persistent infection, 100 agreed to undergo colposcopy; 111 women from the control group were randomly selected to undergo sham HPV testing and colposcopy, and 95 attended. Women with evident cytologic abnormalities received treatment per protocol. Those with negative cytology results were offered annual HPV testing thereafter, and each follow-up with documented type-specific HPV persistence led to repeat colposcopy. A comparable number of women from the control group had repeat colposcopies.

Although some women were lost to clinical follow-up throughout the trial, all 195 who attended the first colposcopy were followed for at least 5 years in the Swedish registry, and 191 were followed in the registry for 13 years. Of 102 women with known HPV persistence at baseline (100 in the treatment group; 2 in the randomly selected control group), 31 became HPV negative, 4 evidenced a switch in HPV type but cleared the initial infection, 27 had unknown persistence status due to missed HPV tests, and 40 had continuously type-specific persistence. Of note, persistent HPV16 infection seemed to impart a higher risk of CIN development than did persistent HPV18 infection.

All 40 participants with clinically verified continuously persistent HPV infection developed CIN2+ within 7 years of baseline documentation of persistence (FIGURE 1). Among the 27 women with unknown persistence status, risk of CIN2+ occurrence within 7 years was 50%. None of the 35 women who cleared their infection or switched HPV type developed CIN2+.

Read about HPV-cytology cotesting

HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years lowers population rates of cervical precancer and cancer

Silver MI, Schiffman M, Fetterman B, et al. The population impact of human papillomavirus/cytology cervical cotesting at 3-year intervals: reduced cervical cancer risk and decreased yield of precancer per screen. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3682−3686.

Current guidelines on screening for cervical cancer in women 30 to 65 years of age advise the preferred strategy of using cytology alone every 3 years or combining HPV testing and cytology every 5 years.1 These guidelines, based on data available at the time they were written, were meant to offer a reasonable balance between timely detection of abnormalities and avoidance of potential harms from screening too frequently. However, many patients are reluctant to postpone repeat testing to the extent recommended. Several authorities have in fact asked that screening intervals be revisited, perhaps allowing for a range of strategies, contending that the level of protection once provided by annual screening should be the benchmark by which evolving strategies are judged.2 Today, they point out, the risk of cancer doubles in the 3 years following an initial negative cytology result, and it also increases by lengthening the cotesting interval from 3 to 5 years. They additionally question the validity of using frequency of colposcopies as a surrogate to measure harms of screening, and suggest that many women would willingly accept the procedure's minimal discomfort and inconvenience to gain peace of mind.

The study by Silver and colleagues gives credence to considering a shorter cotesting interval. Since 2003, Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) has implemented 3-year cotesting. To determine actual clinical outcomes of cotesting at this interval, KPNC analyzed data on more than 1 million women in its care between 2003 and 2012. Although investigators expected that they might see decreasing efficiency in cotesting over time, they instead found an increased detection rate of precancerous lesions per woman screened in the larger of 2 study cohorts.

Related Article:

Women’s Preventive Services Initiative Guidelines provide consensus for practicing ObGyns

Details of the study

Included were all women 30 years of age or older enrolled in this study at KPNC between 2003 and 2012 who underwent HPV−cytology cotesting every 3 years. The population in its entirety (1,065,273 women) was deemed the "open cohort" and represented KPNC's total annual experience. A subset of this population, the "closed cohort," was designed to gauge the effect of repeated screening on a fixed population and comprised only those women enrolled and initially screened between 2003 and 2004 and then followed longitudinally until 2012.

For each cohort, investigators calculated the ratios of precancer and cancer diagnoses to the total number of cotests performed on the cohort's population. The 3-year testing periods were 2004−2006, 2007−2009, and 2010−2012. Also calculated in these periods were the ratios of colposcopic biopsies to cotests and the rates of precancer diagnoses (TABLE).

In the open cohort, the biopsy rate nearly doubled over the course of the study. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 71.5% between the first and second testing periods (P = .001) and then eased off by 10% in the third period (P<.001). These corresponding increases throughout the study yielded a stable number of biopsies (16 to 22) needed to detect precancer.

In the closed long-term cohort, the biopsy rate rose, but not as much as in the open cohort. Precancer diagnoses per number of cotests rose by 47% between the first and second periods (P≤.001), but in the third period fell back by 28% (P<.001) to a level just above the first period results. The number of biopsies needed to detect a precancerous lesion in the closed cohort rose from 19 to 33 over the course of the study, suggesting there may have been some loss of screening efficiency in the fixed group.

Read about molecular profiling of cervical cancer

Molecular profiling of cervical cancer is revolutionizing treatment

The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integratedgenomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. 2017;543(7645):378−384.

Effective treatments for cervical cancer could be close at hand, thanks to a recent explosion of knowledge at the molecular level about how specific cancers arise and what drives them other than HPV. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (TCGA) recently published the results of its genomic and proteomic analyses, which yielded distinct profiles for 178 cervical cancers with important patterns common to other cancers, such as uterine and breast cancer. These recently published findings on cervical cancer highlight areas of gene and protein dysfunction it shares with these other cancers, which could open the doors for new targets for treatments already developed or in the pipeline.

Related Article:

2016 Update on cervical disease

How molecular profiling is paying off for cervical cancer

Cancers develop in any given tissue through the altered function of different genes and signaling pathways in the tissue's cells. The latest extensive investigation conducted by the TCGA network has identified significant mutations in 5 genes previously unrecognized in association with cervical cancer, bringing the total now to 14.

Several highlights are featured in the TCGA's recently published work. One discovery is the amplification of genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2, which are involved with the expression of 2 cytolytic effector genes and are therefore likely targets for immunotherapeutic strategies. Another line of exploration, whole-genome sequencing, has detected an aberration in some cervical cancer tissue with the potential for immediate application. Duplication and copy number gain of BCAR4, a noncoding RNA, facilitates cell proliferation through the HER2/HER3 pathway, a target of the tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, lapatinib, which is currently used to treat breast cancer.

The integration of data from multiple layers of analysis (FIGURE 2) is helping investigators identify variations in cancers. DNA methylation, for instance, is a means by which cells control gene expression. An analysis of this process in cervical tumor tissue has revealed additional cancer subgroups in which messenger RNA increases the transition of epithelial cells to invasive mesenchymal cells. Targeting that process in these subgroups would likely enhance the effectiveness of novel small-molecule inhibitors and some standard cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542.

- Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, DeFrancesco M, Thomas Cox J, Huh W. Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):311–315.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society; American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology; American Society for Clinical Pathology. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542.

- Kinney W, Wright TC, Dinkelspiel HE, DeFrancesco M, Thomas Cox J, Huh W. Increased cervical cancer risk associated with screening at longer intervals. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):311–315.

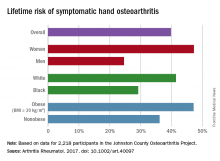

Lifetime risk of hand OA comes close to 40%

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

Almost 40% of Americans can expect to develop hand osteoarthritis (OA) in their lifetimes, according to an analysis involving participants from an ongoing population-based, prospective cohort study.

The overall risk, 39.8%, is based on data from 2,218 eligible subjects in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, but there is significant variation among various subgroups, said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and her associates (Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017 May 4. doi: 10.1002/art.40097).

This report is the first to estimate the lifetime risk of symptomatic hand OA, they noted, and “given the aging population and increasing life expectancy in the United States, it is reasonable to expect that more Americans will be affected by this painful and debilitating condition in the years to come.”

The study was funded by the CDC and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The investigators did not include any disclosures in the report.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

FDA approves first new drug for ALS in decades

The Food and Drug Administration approved the antioxidant drug edaravone on May 5 for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, making it only the second drug ever to be approved by the agency for the motor neuron disease.

The FDA granted approval for edaravone, to be marketed by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America under the brand name Radicava, through its orphan drug pathway, which is meant for drugs used to treat rare diseases or conditions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) affects 12,000-15,000 Americans.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America demonstrated the efficacy of edaravone in a 6-month trial of 137 Japanese ALS patients. At 24 weeks, individuals who received edaravone had less decline on a clinical assessment of daily functioning, the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R), compared with those who received a placebo. The difference in decline between the two groups was 33%, or a total of 2.49 points, on the ALSFRS-R. Most of the patients in the study also received the only other drug approved for ALS, riluzole (Rilutek).

Edaravone is thought to confer neuroprotection in part through its free radical–scavenging activity.

The adverse events most often reported by clinical trial participants who took edaravone included bruising and gait disturbance. The FDA also warned that edaravone is associated with hives, swelling, or shortness of breath, and allergic reactions to an ingredient in the drug, sodium bisulfite, which may cause anaphylactic symptoms that can be life-threatening in people with sulfite sensitivity.

The drug is administered via intravenous infusion with an initial treatment cycle of daily dosing for 14 days, followed by a 14-day drug-free period. Subsequent treatment cycles consist of dosing on 10 of 14 days, followed by 14 days drug-free.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America said in a statement that it has created a patient access program called Searchlight Support for people with ALS who are prescribed the drug. The program provides personal case management, reimbursement support, and 24/7 clinical support.

In 2015, edaravone was approved for use as a treatment for ALS in Japan and South Korea.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the antioxidant drug edaravone on May 5 for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, making it only the second drug ever to be approved by the agency for the motor neuron disease.

The FDA granted approval for edaravone, to be marketed by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America under the brand name Radicava, through its orphan drug pathway, which is meant for drugs used to treat rare diseases or conditions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) affects 12,000-15,000 Americans.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America demonstrated the efficacy of edaravone in a 6-month trial of 137 Japanese ALS patients. At 24 weeks, individuals who received edaravone had less decline on a clinical assessment of daily functioning, the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R), compared with those who received a placebo. The difference in decline between the two groups was 33%, or a total of 2.49 points, on the ALSFRS-R. Most of the patients in the study also received the only other drug approved for ALS, riluzole (Rilutek).

Edaravone is thought to confer neuroprotection in part through its free radical–scavenging activity.

The adverse events most often reported by clinical trial participants who took edaravone included bruising and gait disturbance. The FDA also warned that edaravone is associated with hives, swelling, or shortness of breath, and allergic reactions to an ingredient in the drug, sodium bisulfite, which may cause anaphylactic symptoms that can be life-threatening in people with sulfite sensitivity.

The drug is administered via intravenous infusion with an initial treatment cycle of daily dosing for 14 days, followed by a 14-day drug-free period. Subsequent treatment cycles consist of dosing on 10 of 14 days, followed by 14 days drug-free.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America said in a statement that it has created a patient access program called Searchlight Support for people with ALS who are prescribed the drug. The program provides personal case management, reimbursement support, and 24/7 clinical support.

In 2015, edaravone was approved for use as a treatment for ALS in Japan and South Korea.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the antioxidant drug edaravone on May 5 for the treatment of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, making it only the second drug ever to be approved by the agency for the motor neuron disease.

The FDA granted approval for edaravone, to be marketed by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America under the brand name Radicava, through its orphan drug pathway, which is meant for drugs used to treat rare diseases or conditions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) affects 12,000-15,000 Americans.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America demonstrated the efficacy of edaravone in a 6-month trial of 137 Japanese ALS patients. At 24 weeks, individuals who received edaravone had less decline on a clinical assessment of daily functioning, the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R), compared with those who received a placebo. The difference in decline between the two groups was 33%, or a total of 2.49 points, on the ALSFRS-R. Most of the patients in the study also received the only other drug approved for ALS, riluzole (Rilutek).

Edaravone is thought to confer neuroprotection in part through its free radical–scavenging activity.

The adverse events most often reported by clinical trial participants who took edaravone included bruising and gait disturbance. The FDA also warned that edaravone is associated with hives, swelling, or shortness of breath, and allergic reactions to an ingredient in the drug, sodium bisulfite, which may cause anaphylactic symptoms that can be life-threatening in people with sulfite sensitivity.

The drug is administered via intravenous infusion with an initial treatment cycle of daily dosing for 14 days, followed by a 14-day drug-free period. Subsequent treatment cycles consist of dosing on 10 of 14 days, followed by 14 days drug-free.

Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma America said in a statement that it has created a patient access program called Searchlight Support for people with ALS who are prescribed the drug. The program provides personal case management, reimbursement support, and 24/7 clinical support.

In 2015, edaravone was approved for use as a treatment for ALS in Japan and South Korea.

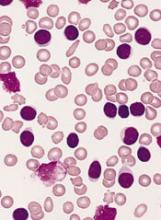

BTK inhibitor staves off progression in CLL

Long-term follow-up of a phase 1 study suggests the BTK inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 can stave off progression in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Roughly 60% of the patients studied were progression-free and still taking ONO/GS-4059 at last follow-up, with the longest time on treatment exceeding 3 years.

In addition, researchers said the extended follow-up revealed no new safety concerns, and the maximum tolerated dose of ONO/GS-4059 has not been reached.

Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester in the UK, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

The research was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., and ONO Pharmaceuticals helped with data analysis.

The study enrolled 90 patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies, 28 of whom had CLL. Dr Dyer and his colleagues reported follow-up results in CLL patients only.

The patients’ median number of prior treatments was 4 (range, 2-9), and 11 patients were refractory to their last line of therapy. None had received prior treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

The patients received ONO/GS-4059 at varying doses, from 20 mg once daily (QD) to 600 mg QD and a twice-daily (BID) regimen of 300 mg. Six patients were also taking anticoagulant therapy while on study.

Patients were allowed to continue treatment with ONO/GS-4059 if they responded to the drug or maintained stable disease.

Initially, 25 patients were evaluable for response, and 24 of them responded to ONO/GS-4059, for an overall response rate of 96%.

At last follow-up on June 8, 2016, 17 patients were still receiving ONO/GS-4059, and all had a very good partial response.

Dr Dyer said the responses have been similar to those seen with other irreversible BTK inhibitors. Most have involved rapid and almost complete resolution of lymph node masses and rapid improvement in hematological indexes.

“It is clear . . . that the major responses occur rapidly, within the first 3 months of drug, and that, thereafter, improvement occurs at a much slower rate,” Dr Dyer said. “It will be of interest, I think, to look at the remaining patients on study to assess whether responses deepen with time on drug.”

The duration of treatment for these patients ranged from 302 days to 1160 days at last follow-up. They were receiving ONO/GS-4059 at doses ranging from 40 mg QD to 600 mg QD or 300 mg BID, and no maximum tolerated dose had been identified.

Eleven patients (39.3%) discontinued ONO/GS-4059 due to death (n=3), disease progression (n=4), adverse events (AEs, n=3), and sponsor decision due to extended drug interruption (n=1). One of the patients included in the AE group also had concurrent disease progression.

The median progression-free survival was 38.5 months, and the median overall survival was 44.9 months. The median time on study was 32.5 months.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were bruising (35.7%), neutropenia (35.7%), anemia (32.1%), nasopharyngitis (32.1%), fall (32.1%), cough (28.6%), arthralgia (28.6%), and basal cell carcinoma (28.6%).

The most common grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (25%), thrombocytopenia (14.3%), lower respiratory tract infection (14.3%), and anemia (10.7%).

“Our long-term follow-up shows maintained efficacy without toxicity,” Dr Dyer said. “This study is the first report of long-term follow-up of a selective BTK inhibitor, and it is excellent news for patients. We are now doing studies of ONO/GS-4059 in combination with other precision medicines to assess whether these results can be enhanced in patients with CLL and other B-cell malignancies.” ![]()

Long-term follow-up of a phase 1 study suggests the BTK inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 can stave off progression in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Roughly 60% of the patients studied were progression-free and still taking ONO/GS-4059 at last follow-up, with the longest time on treatment exceeding 3 years.

In addition, researchers said the extended follow-up revealed no new safety concerns, and the maximum tolerated dose of ONO/GS-4059 has not been reached.

Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester in the UK, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

The research was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., and ONO Pharmaceuticals helped with data analysis.

The study enrolled 90 patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies, 28 of whom had CLL. Dr Dyer and his colleagues reported follow-up results in CLL patients only.

The patients’ median number of prior treatments was 4 (range, 2-9), and 11 patients were refractory to their last line of therapy. None had received prior treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

The patients received ONO/GS-4059 at varying doses, from 20 mg once daily (QD) to 600 mg QD and a twice-daily (BID) regimen of 300 mg. Six patients were also taking anticoagulant therapy while on study.

Patients were allowed to continue treatment with ONO/GS-4059 if they responded to the drug or maintained stable disease.

Initially, 25 patients were evaluable for response, and 24 of them responded to ONO/GS-4059, for an overall response rate of 96%.

At last follow-up on June 8, 2016, 17 patients were still receiving ONO/GS-4059, and all had a very good partial response.

Dr Dyer said the responses have been similar to those seen with other irreversible BTK inhibitors. Most have involved rapid and almost complete resolution of lymph node masses and rapid improvement in hematological indexes.

“It is clear . . . that the major responses occur rapidly, within the first 3 months of drug, and that, thereafter, improvement occurs at a much slower rate,” Dr Dyer said. “It will be of interest, I think, to look at the remaining patients on study to assess whether responses deepen with time on drug.”

The duration of treatment for these patients ranged from 302 days to 1160 days at last follow-up. They were receiving ONO/GS-4059 at doses ranging from 40 mg QD to 600 mg QD or 300 mg BID, and no maximum tolerated dose had been identified.

Eleven patients (39.3%) discontinued ONO/GS-4059 due to death (n=3), disease progression (n=4), adverse events (AEs, n=3), and sponsor decision due to extended drug interruption (n=1). One of the patients included in the AE group also had concurrent disease progression.

The median progression-free survival was 38.5 months, and the median overall survival was 44.9 months. The median time on study was 32.5 months.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were bruising (35.7%), neutropenia (35.7%), anemia (32.1%), nasopharyngitis (32.1%), fall (32.1%), cough (28.6%), arthralgia (28.6%), and basal cell carcinoma (28.6%).

The most common grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (25%), thrombocytopenia (14.3%), lower respiratory tract infection (14.3%), and anemia (10.7%).

“Our long-term follow-up shows maintained efficacy without toxicity,” Dr Dyer said. “This study is the first report of long-term follow-up of a selective BTK inhibitor, and it is excellent news for patients. We are now doing studies of ONO/GS-4059 in combination with other precision medicines to assess whether these results can be enhanced in patients with CLL and other B-cell malignancies.” ![]()

Long-term follow-up of a phase 1 study suggests the BTK inhibitor ONO/GS-4059 can stave off progression in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Roughly 60% of the patients studied were progression-free and still taking ONO/GS-4059 at last follow-up, with the longest time on treatment exceeding 3 years.

In addition, researchers said the extended follow-up revealed no new safety concerns, and the maximum tolerated dose of ONO/GS-4059 has not been reached.

Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester in the UK, and his colleagues reported these results in Blood.

The research was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc., and ONO Pharmaceuticals helped with data analysis.

The study enrolled 90 patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies, 28 of whom had CLL. Dr Dyer and his colleagues reported follow-up results in CLL patients only.

The patients’ median number of prior treatments was 4 (range, 2-9), and 11 patients were refractory to their last line of therapy. None had received prior treatment with a BTK inhibitor.

The patients received ONO/GS-4059 at varying doses, from 20 mg once daily (QD) to 600 mg QD and a twice-daily (BID) regimen of 300 mg. Six patients were also taking anticoagulant therapy while on study.

Patients were allowed to continue treatment with ONO/GS-4059 if they responded to the drug or maintained stable disease.

Initially, 25 patients were evaluable for response, and 24 of them responded to ONO/GS-4059, for an overall response rate of 96%.

At last follow-up on June 8, 2016, 17 patients were still receiving ONO/GS-4059, and all had a very good partial response.

Dr Dyer said the responses have been similar to those seen with other irreversible BTK inhibitors. Most have involved rapid and almost complete resolution of lymph node masses and rapid improvement in hematological indexes.

“It is clear . . . that the major responses occur rapidly, within the first 3 months of drug, and that, thereafter, improvement occurs at a much slower rate,” Dr Dyer said. “It will be of interest, I think, to look at the remaining patients on study to assess whether responses deepen with time on drug.”

The duration of treatment for these patients ranged from 302 days to 1160 days at last follow-up. They were receiving ONO/GS-4059 at doses ranging from 40 mg QD to 600 mg QD or 300 mg BID, and no maximum tolerated dose had been identified.

Eleven patients (39.3%) discontinued ONO/GS-4059 due to death (n=3), disease progression (n=4), adverse events (AEs, n=3), and sponsor decision due to extended drug interruption (n=1). One of the patients included in the AE group also had concurrent disease progression.

The median progression-free survival was 38.5 months, and the median overall survival was 44.9 months. The median time on study was 32.5 months.

The most common treatment-emergent AEs were bruising (35.7%), neutropenia (35.7%), anemia (32.1%), nasopharyngitis (32.1%), fall (32.1%), cough (28.6%), arthralgia (28.6%), and basal cell carcinoma (28.6%).

The most common grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (25%), thrombocytopenia (14.3%), lower respiratory tract infection (14.3%), and anemia (10.7%).

“Our long-term follow-up shows maintained efficacy without toxicity,” Dr Dyer said. “This study is the first report of long-term follow-up of a selective BTK inhibitor, and it is excellent news for patients. We are now doing studies of ONO/GS-4059 in combination with other precision medicines to assess whether these results can be enhanced in patients with CLL and other B-cell malignancies.” ![]()

Psychological account of Robert Lowell’s life is magnificent

Robert Lowell knew civic valor. Sixteen times and more he had been down on his knees in madness, he said. Sixteen times and more he had gotten up. He had gone back to his work, entered back into life. He had faced down uncertainty and madness, had created new forms when pushed to stay with the old, had brought back imaginative order from chaos. It was a different kind of courage, this civic courage, and the rules of engagement were unclear. Lowell’s life, as his daughter observed, was a messy one, difficult for him and for those who knew him. But it was lived with iron, and often with grace. He kept always in the front of his mind what he thought he ought to be, even when he couldn’t be it; he believed in what his country could be, even if it wasn’t. He worked hard at his art.

–Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, in “Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017).

Lowell, who lived from 1917 to 1977, was a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, deemed to be the greatest American poet of his time. He studied the classics and was obsessed with Napoleon as a child, and he drew on the work of other great poets and classicists as influences for his own work. I must confess, I came to this psychological study having never read the work of Robert Lowell. My only familiarity with the poet came directly from the author. I heard Dr. Jamison, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, speak several years ago at the Johns Hopkins Annual Mood Disorders Symposium about her then work-in-progress as she was researching this book. What I heard was intriguing enough that I was eager to read and review a long and solid book about a great poet whose work I had never read.

As I began “Setting The River On Fire,” my first thought was that the writing itself was astounding. Dr. Jamison’s words flow, her metaphors never fall flat or feel artificial, the ride itself is lovely. I looked for a few lines to quote as an example, and I was left at a standstill. One line was more gracious than the next. I finally settled on the quote I used at the beginning of this piece, benignly chosen from page 403 because it encapsulated not just the beautiful writing but a synopsis of who Lowell was and what he had achieved, set in the context of attempted differentiation between the man, the madness, and the interplay of the two.

Dr. Jamison’s research on Lowell’s life is nothing short of astounding and was clearly a labor that took both sustained passion and years of her time. Dr. Jamison quoted the poet at length. She is an expert on his many volumes of poetry and prose, as well as his life and loves – three marriages and many intimate friendships – documented through letters and conversations. In addition, she quoted many other poets as examples of how their work influenced Lowell. Beyond the literature and correspondence, Dr. Jamison interviewed those who knew Lowell well. She unearthed his medical and psychiatric records, and she plotted out the course of his life in an uncanny way, linking so much of his work to the ebbs and flows of his illness. My only “criticism” of the book would be in how extensive it is. She sometimes makes a point by quoting several sources, each of whom drive at the same idea. It makes for very strong rhetoric.

His second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, had a striking understanding of his illness as a biological disorder beyond his control. Her sympathy for his behavior as a product of illness allowed her to tolerate actions that many people would not, even with our current day emphasis on disease states, including sexual indiscretions. His friends, too, saw the uncharacteristic chaos of his manias as the result of a state of illness, and, as such, as forgivable. These were often not subtle indiscretions: Jamison describes intense delusional states, combative behavior, police with straightjackets, often at very public and professional events worldwide. If psychoanalytic thinking weighed in on an understanding of Lowell’s motivations, Dr. Jamison did not include it in her study of Lowell, and she makes a point at the end of saying that she focused on his illness and did not include the content of psychotherapy notes. Still, I was struck by the understanding of his depressions and manias as a state of illness by lay people in his life and thought that, given the time period, it was noteworthy.

On a similar vein, I wondered if Lowell could live his life now as he lived his life then. A crucial arena for his career was Harvard College, where he returned over and over to teach. Dr. Jamison says that Lowell lectured in an acutely psychotic and disorganized state. She says that, while students clamored to take his classes, so, too, they were afraid of him. I cannot quite imagine that, in our world of “trigger warnings,” microaggressions, and college safe spaces, we might ever allow an openly ill genius to reign in a classroom of students. I am never certain if we are aimed forward or backward in our struggle against stigma, and “Setting The River On Fire” may be one more example in which we have lost ground in a quest for tolerance.

Once again, Dr. Jamison pulled me into her world. “Setting The River On Fire” is no one’s version of a light or happy read, it is a serious study of an intensely brilliant and often desperately ill poet – and it does not disappoint.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Robert Lowell knew civic valor. Sixteen times and more he had been down on his knees in madness, he said. Sixteen times and more he had gotten up. He had gone back to his work, entered back into life. He had faced down uncertainty and madness, had created new forms when pushed to stay with the old, had brought back imaginative order from chaos. It was a different kind of courage, this civic courage, and the rules of engagement were unclear. Lowell’s life, as his daughter observed, was a messy one, difficult for him and for those who knew him. But it was lived with iron, and often with grace. He kept always in the front of his mind what he thought he ought to be, even when he couldn’t be it; he believed in what his country could be, even if it wasn’t. He worked hard at his art.

–Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, in “Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017).

Lowell, who lived from 1917 to 1977, was a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, deemed to be the greatest American poet of his time. He studied the classics and was obsessed with Napoleon as a child, and he drew on the work of other great poets and classicists as influences for his own work. I must confess, I came to this psychological study having never read the work of Robert Lowell. My only familiarity with the poet came directly from the author. I heard Dr. Jamison, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, speak several years ago at the Johns Hopkins Annual Mood Disorders Symposium about her then work-in-progress as she was researching this book. What I heard was intriguing enough that I was eager to read and review a long and solid book about a great poet whose work I had never read.

As I began “Setting The River On Fire,” my first thought was that the writing itself was astounding. Dr. Jamison’s words flow, her metaphors never fall flat or feel artificial, the ride itself is lovely. I looked for a few lines to quote as an example, and I was left at a standstill. One line was more gracious than the next. I finally settled on the quote I used at the beginning of this piece, benignly chosen from page 403 because it encapsulated not just the beautiful writing but a synopsis of who Lowell was and what he had achieved, set in the context of attempted differentiation between the man, the madness, and the interplay of the two.

Dr. Jamison’s research on Lowell’s life is nothing short of astounding and was clearly a labor that took both sustained passion and years of her time. Dr. Jamison quoted the poet at length. She is an expert on his many volumes of poetry and prose, as well as his life and loves – three marriages and many intimate friendships – documented through letters and conversations. In addition, she quoted many other poets as examples of how their work influenced Lowell. Beyond the literature and correspondence, Dr. Jamison interviewed those who knew Lowell well. She unearthed his medical and psychiatric records, and she plotted out the course of his life in an uncanny way, linking so much of his work to the ebbs and flows of his illness. My only “criticism” of the book would be in how extensive it is. She sometimes makes a point by quoting several sources, each of whom drive at the same idea. It makes for very strong rhetoric.

His second wife, Elizabeth Hardwick, had a striking understanding of his illness as a biological disorder beyond his control. Her sympathy for his behavior as a product of illness allowed her to tolerate actions that many people would not, even with our current day emphasis on disease states, including sexual indiscretions. His friends, too, saw the uncharacteristic chaos of his manias as the result of a state of illness, and, as such, as forgivable. These were often not subtle indiscretions: Jamison describes intense delusional states, combative behavior, police with straightjackets, often at very public and professional events worldwide. If psychoanalytic thinking weighed in on an understanding of Lowell’s motivations, Dr. Jamison did not include it in her study of Lowell, and she makes a point at the end of saying that she focused on his illness and did not include the content of psychotherapy notes. Still, I was struck by the understanding of his depressions and manias as a state of illness by lay people in his life and thought that, given the time period, it was noteworthy.

On a similar vein, I wondered if Lowell could live his life now as he lived his life then. A crucial arena for his career was Harvard College, where he returned over and over to teach. Dr. Jamison says that Lowell lectured in an acutely psychotic and disorganized state. She says that, while students clamored to take his classes, so, too, they were afraid of him. I cannot quite imagine that, in our world of “trigger warnings,” microaggressions, and college safe spaces, we might ever allow an openly ill genius to reign in a classroom of students. I am never certain if we are aimed forward or backward in our struggle against stigma, and “Setting The River On Fire” may be one more example in which we have lost ground in a quest for tolerance.

Once again, Dr. Jamison pulled me into her world. “Setting The River On Fire” is no one’s version of a light or happy read, it is a serious study of an intensely brilliant and often desperately ill poet – and it does not disappoint.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Robert Lowell knew civic valor. Sixteen times and more he had been down on his knees in madness, he said. Sixteen times and more he had gotten up. He had gone back to his work, entered back into life. He had faced down uncertainty and madness, had created new forms when pushed to stay with the old, had brought back imaginative order from chaos. It was a different kind of courage, this civic courage, and the rules of engagement were unclear. Lowell’s life, as his daughter observed, was a messy one, difficult for him and for those who knew him. But it was lived with iron, and often with grace. He kept always in the front of his mind what he thought he ought to be, even when he couldn’t be it; he believed in what his country could be, even if it wasn’t. He worked hard at his art.

–Kay Redfield Jamison, PhD, in “Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character” (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2017).