User login

Burden of cancer varies by cancer type, race

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests that leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) are among the top 10 cancers with the greatest burden (most years of healthy life lost) in the US.

The research also showed that the burden of different cancer types varied between patients belonging to different racial/ethnic groups.

For example, the contribution of leukemia to the overall cancer burden was twice as high in Hispanics as it was in non-Hispanic blacks. The same was true for NHL.

Joannie Lortet-Tieulent, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The researchers calculated the burden of cancer in the US in 2011 for 24 cancer types. They calculated burden using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which combine cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and quality of life into a summary indicator.

The results suggested the burden of cancer in 2011 was over 9.8 million DALYs, which was equally shared between men and women—4.9 million DALYs for each sex.

DALYs lost to cancer were mostly related to premature death due to cancer (91%). The remaining 9% were related to impaired quality of life because of the disease or its treatment, or other disease-related issues.

Top 10 contributors

The researchers calculated the proportion of DALYs lost for each of the cancer types. And they found that lung cancer was the largest contributor to the loss of healthy years, accounting for 24% of the burden (2.4 million DALYs).

The second biggest contributor to the loss of healthy years was breast cancer (10%), followed by colorectal cancer (9%), pancreatic cancer (6%), prostate cancer (5%), leukemia (4%), liver cancer (4%), brain cancer (3%), NHL (3%), and ovarian cancer (3%).

The researchers also calculated the proportion of DALYs lost from the top 10 cancer types according to race/ethnicity.

They found the contribution of leukemia to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (6%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (5%), non-Hispanic whites (4%), and non-Hispanic blacks (3%).

The contribution of NHL to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (4%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians/non-Hispanic whites (3% for both), and non-Hispanic blacks (2%).

DALYs by race/ethnicity

The researchers found that, overall, the cancer burden was highest in non-Hispanic blacks, followed by non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Asians. However, this pattern was not consistent across the different cancer types.

Age-standardized DALYs lost (per 100,000 individuals) were as follows:

All cancers combined

3588 for non-Hispanic blacks

2898 for non-Hispanic whites

1978 for Hispanics

1798 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Leukemia

115 for non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites

98 for Hispanics

82 for non-Hispanic Asians.

NHL

93 for non-Hispanic whites

86 for non-Hispanic blacks

78 for Hispanics

60 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Hodgkin lymphoma

11 for non-Hispanic blacks

10 for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics

3 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Myeloma

93 for non-Hispanic blacks

43 for non-Hispanic whites

42 for Hispanics

26 for non-Hispanic Asians.

The researchers noted that, despite these differences, the cancer burden in all races/ethnicities was driven by years of life lost. They said this highlights the need to prevent deaths by improving prevention, early detection, and treatment of cancers. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests that leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) are among the top 10 cancers with the greatest burden (most years of healthy life lost) in the US.

The research also showed that the burden of different cancer types varied between patients belonging to different racial/ethnic groups.

For example, the contribution of leukemia to the overall cancer burden was twice as high in Hispanics as it was in non-Hispanic blacks. The same was true for NHL.

Joannie Lortet-Tieulent, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The researchers calculated the burden of cancer in the US in 2011 for 24 cancer types. They calculated burden using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which combine cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and quality of life into a summary indicator.

The results suggested the burden of cancer in 2011 was over 9.8 million DALYs, which was equally shared between men and women—4.9 million DALYs for each sex.

DALYs lost to cancer were mostly related to premature death due to cancer (91%). The remaining 9% were related to impaired quality of life because of the disease or its treatment, or other disease-related issues.

Top 10 contributors

The researchers calculated the proportion of DALYs lost for each of the cancer types. And they found that lung cancer was the largest contributor to the loss of healthy years, accounting for 24% of the burden (2.4 million DALYs).

The second biggest contributor to the loss of healthy years was breast cancer (10%), followed by colorectal cancer (9%), pancreatic cancer (6%), prostate cancer (5%), leukemia (4%), liver cancer (4%), brain cancer (3%), NHL (3%), and ovarian cancer (3%).

The researchers also calculated the proportion of DALYs lost from the top 10 cancer types according to race/ethnicity.

They found the contribution of leukemia to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (6%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (5%), non-Hispanic whites (4%), and non-Hispanic blacks (3%).

The contribution of NHL to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (4%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians/non-Hispanic whites (3% for both), and non-Hispanic blacks (2%).

DALYs by race/ethnicity

The researchers found that, overall, the cancer burden was highest in non-Hispanic blacks, followed by non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Asians. However, this pattern was not consistent across the different cancer types.

Age-standardized DALYs lost (per 100,000 individuals) were as follows:

All cancers combined

3588 for non-Hispanic blacks

2898 for non-Hispanic whites

1978 for Hispanics

1798 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Leukemia

115 for non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites

98 for Hispanics

82 for non-Hispanic Asians.

NHL

93 for non-Hispanic whites

86 for non-Hispanic blacks

78 for Hispanics

60 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Hodgkin lymphoma

11 for non-Hispanic blacks

10 for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics

3 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Myeloma

93 for non-Hispanic blacks

43 for non-Hispanic whites

42 for Hispanics

26 for non-Hispanic Asians.

The researchers noted that, despite these differences, the cancer burden in all races/ethnicities was driven by years of life lost. They said this highlights the need to prevent deaths by improving prevention, early detection, and treatment of cancers. ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests that leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) are among the top 10 cancers with the greatest burden (most years of healthy life lost) in the US.

The research also showed that the burden of different cancer types varied between patients belonging to different racial/ethnic groups.

For example, the contribution of leukemia to the overall cancer burden was twice as high in Hispanics as it was in non-Hispanic blacks. The same was true for NHL.

Joannie Lortet-Tieulent, of the American Cancer Society in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues conducted this study and reported the results in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

The researchers calculated the burden of cancer in the US in 2011 for 24 cancer types. They calculated burden using disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which combine cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and quality of life into a summary indicator.

The results suggested the burden of cancer in 2011 was over 9.8 million DALYs, which was equally shared between men and women—4.9 million DALYs for each sex.

DALYs lost to cancer were mostly related to premature death due to cancer (91%). The remaining 9% were related to impaired quality of life because of the disease or its treatment, or other disease-related issues.

Top 10 contributors

The researchers calculated the proportion of DALYs lost for each of the cancer types. And they found that lung cancer was the largest contributor to the loss of healthy years, accounting for 24% of the burden (2.4 million DALYs).

The second biggest contributor to the loss of healthy years was breast cancer (10%), followed by colorectal cancer (9%), pancreatic cancer (6%), prostate cancer (5%), leukemia (4%), liver cancer (4%), brain cancer (3%), NHL (3%), and ovarian cancer (3%).

The researchers also calculated the proportion of DALYs lost from the top 10 cancer types according to race/ethnicity.

They found the contribution of leukemia to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (6%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians (5%), non-Hispanic whites (4%), and non-Hispanic blacks (3%).

The contribution of NHL to the loss of healthy years was greatest for Hispanics (4%), followed by non-Hispanic Asians/non-Hispanic whites (3% for both), and non-Hispanic blacks (2%).

DALYs by race/ethnicity

The researchers found that, overall, the cancer burden was highest in non-Hispanic blacks, followed by non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic Asians. However, this pattern was not consistent across the different cancer types.

Age-standardized DALYs lost (per 100,000 individuals) were as follows:

All cancers combined

3588 for non-Hispanic blacks

2898 for non-Hispanic whites

1978 for Hispanics

1798 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Leukemia

115 for non-Hispanic blacks and non-Hispanic whites

98 for Hispanics

82 for non-Hispanic Asians.

NHL

93 for non-Hispanic whites

86 for non-Hispanic blacks

78 for Hispanics

60 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Hodgkin lymphoma

11 for non-Hispanic blacks

10 for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics

3 for non-Hispanic Asians.

Myeloma

93 for non-Hispanic blacks

43 for non-Hispanic whites

42 for Hispanics

26 for non-Hispanic Asians.

The researchers noted that, despite these differences, the cancer burden in all races/ethnicities was driven by years of life lost. They said this highlights the need to prevent deaths by improving prevention, early detection, and treatment of cancers. ![]()

Single-cell findings could inform CLL treatment

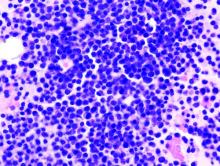

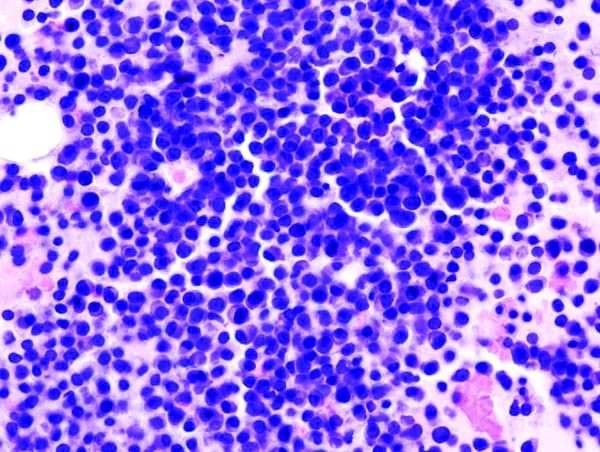

Researchers say they have found a better way to examine individual cells, and this tool provided insight that could inform the treatment of leukemia.

The team used a technique called microarrayed single-cell sequencing (MASC-seq) to examine individual cells in samples from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

This revealed a number of CLL subclones within each sample that exhibited different gene expression.

“With this new, highly cost-effective technology, we can now get a whole new view of this complexity within the blood cancer sample,” said study author Joakim Lundeberg, PhD, of KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Molecular resolution of single cells is likely to become a more widely used therapy option.”

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

The researchers said current methods of single-cell analysis don’t allow for the combination of cell imaging and transcriptome profiling, exhibit low-throughput by analyzing a single cell at a time, or require expensive droplet instrumentation for high-throughput analysis.

MASC-seq, on the other hand, can image cells to provide information on morphology and profile the expression of thousands of single cells per day at a cost of $0.13 USD per cell.

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues tested MASC-seq by analyzing samples from 3 patients with different subtypes of CLL.

The team found clear differences in the average gene expression levels of cells from the different CLL subtypes, but they also found subtle differences between single cells within each of the subtypes.

The researchers therefore concluded that MASC-seq has the potential to accelerate the study of subtle clonal dynamics and help provide insight into the development of CLL and other diseases. ![]()

Researchers say they have found a better way to examine individual cells, and this tool provided insight that could inform the treatment of leukemia.

The team used a technique called microarrayed single-cell sequencing (MASC-seq) to examine individual cells in samples from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

This revealed a number of CLL subclones within each sample that exhibited different gene expression.

“With this new, highly cost-effective technology, we can now get a whole new view of this complexity within the blood cancer sample,” said study author Joakim Lundeberg, PhD, of KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Molecular resolution of single cells is likely to become a more widely used therapy option.”

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

The researchers said current methods of single-cell analysis don’t allow for the combination of cell imaging and transcriptome profiling, exhibit low-throughput by analyzing a single cell at a time, or require expensive droplet instrumentation for high-throughput analysis.

MASC-seq, on the other hand, can image cells to provide information on morphology and profile the expression of thousands of single cells per day at a cost of $0.13 USD per cell.

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues tested MASC-seq by analyzing samples from 3 patients with different subtypes of CLL.

The team found clear differences in the average gene expression levels of cells from the different CLL subtypes, but they also found subtle differences between single cells within each of the subtypes.

The researchers therefore concluded that MASC-seq has the potential to accelerate the study of subtle clonal dynamics and help provide insight into the development of CLL and other diseases. ![]()

Researchers say they have found a better way to examine individual cells, and this tool provided insight that could inform the treatment of leukemia.

The team used a technique called microarrayed single-cell sequencing (MASC-seq) to examine individual cells in samples from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

This revealed a number of CLL subclones within each sample that exhibited different gene expression.

“With this new, highly cost-effective technology, we can now get a whole new view of this complexity within the blood cancer sample,” said study author Joakim Lundeberg, PhD, of KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden.

“Molecular resolution of single cells is likely to become a more widely used therapy option.”

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues described this work in Nature Communications.

The researchers said current methods of single-cell analysis don’t allow for the combination of cell imaging and transcriptome profiling, exhibit low-throughput by analyzing a single cell at a time, or require expensive droplet instrumentation for high-throughput analysis.

MASC-seq, on the other hand, can image cells to provide information on morphology and profile the expression of thousands of single cells per day at a cost of $0.13 USD per cell.

Dr Lundeberg and his colleagues tested MASC-seq by analyzing samples from 3 patients with different subtypes of CLL.

The team found clear differences in the average gene expression levels of cells from the different CLL subtypes, but they also found subtle differences between single cells within each of the subtypes.

The researchers therefore concluded that MASC-seq has the potential to accelerate the study of subtle clonal dynamics and help provide insight into the development of CLL and other diseases. ![]()

Combo produces CR/CRis in FLT3-ITD AML

Photo by Bill Branson

A 2-drug combination has shown promise for treating patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers found that omacetaxine mepesuccinate (formerly known as homoharringtonine) exhibits preferential antileukemic activity against FLT3-ITD AML.

Subsequent preclinical experiments revealed that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors.

So researchers tested omacetaxine in combination with sorafenib in a phase 2 trial of patients with FLT3-ITD AML.

The combination produced complete responses (CRs) or CRs with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRis) in a majority of patients, and researchers said the treatment was well-tolerated.

Anskar Y. H. Leung, MD, PhD, of The University of Hong Kong, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team first performed an in vitro screen on AML patient samples to determine their responses to various drugs.

One of the compounds tested, the protein translation inhibitor omacetaxine mepesuccinate, showed strong antileukemic effects against FLT3-ITD AML. In fact, omacetaxine preferentially inhibited the growth of FLT3-ITD cell lines.

The researchers then found that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors to suppress leukemia growth in FLT3-ITD AML cell lines.

Omacetaxine and sorafenib in combination also prolonged survival in mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML (mice transplanted with MV4-11 or MOLM-13 cells).

Phase 2 trial

The researchers went on to test omacetaxine and sorafenib in a phase 2 trial. The trial enrolled 24 patients with FLT3-ITD AML and a median age of 50 (range, 21-76).

Most of the patients had relapsed or refractory disease, but 2 were unsuitable for induction chemotherapy because of advanced age and comorbidities.

The patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib continuously until intolerance, disease progression, or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Twenty patients (83.3%) achieved a CR or CRi at a median of 22 days (range, 18-55). Three patients did not respond, and 1 patient experienced a near-CRi—a reduction of blasts without complete clearance.

Fifteen of the responders relapsed, but 3 of these patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib again and achieved a CRi. One patient received re-treatment and failed to achieve a response.

Seven patients proceeded to HSCT after receiving omacetaxine and sorafenib.

At a median follow-up of 7.1 months (range, 2.2 to 20.5), 4 patients were still in CR/CRi (3 patients after HSCT), and 1 patient who had relapsed was still alive.

The remaining 19 patients had died—14 due to relapse, 4 due to non-response (1 after re-treatment), and 1 due to HSCT.

The median leukemia-free survival was 88 days (range, 9-510), and the median overall survival was 228 days (range, 53 to 615).

Adverse events occurring after treatment with omacetaxine and sorafenib included fever (n=14), rash (n=8), hand-foot-skin reactions (n=6), pneumonia (n=2), neutropenic fever (n=1), and bacteremia (n=1).

The researchers said this study validated the principle and clinical relevance of in vitro drug testing and identified a drug combination that might improve the treatment of FLT3-ITD AML. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A 2-drug combination has shown promise for treating patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers found that omacetaxine mepesuccinate (formerly known as homoharringtonine) exhibits preferential antileukemic activity against FLT3-ITD AML.

Subsequent preclinical experiments revealed that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors.

So researchers tested omacetaxine in combination with sorafenib in a phase 2 trial of patients with FLT3-ITD AML.

The combination produced complete responses (CRs) or CRs with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRis) in a majority of patients, and researchers said the treatment was well-tolerated.

Anskar Y. H. Leung, MD, PhD, of The University of Hong Kong, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team first performed an in vitro screen on AML patient samples to determine their responses to various drugs.

One of the compounds tested, the protein translation inhibitor omacetaxine mepesuccinate, showed strong antileukemic effects against FLT3-ITD AML. In fact, omacetaxine preferentially inhibited the growth of FLT3-ITD cell lines.

The researchers then found that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors to suppress leukemia growth in FLT3-ITD AML cell lines.

Omacetaxine and sorafenib in combination also prolonged survival in mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML (mice transplanted with MV4-11 or MOLM-13 cells).

Phase 2 trial

The researchers went on to test omacetaxine and sorafenib in a phase 2 trial. The trial enrolled 24 patients with FLT3-ITD AML and a median age of 50 (range, 21-76).

Most of the patients had relapsed or refractory disease, but 2 were unsuitable for induction chemotherapy because of advanced age and comorbidities.

The patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib continuously until intolerance, disease progression, or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Twenty patients (83.3%) achieved a CR or CRi at a median of 22 days (range, 18-55). Three patients did not respond, and 1 patient experienced a near-CRi—a reduction of blasts without complete clearance.

Fifteen of the responders relapsed, but 3 of these patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib again and achieved a CRi. One patient received re-treatment and failed to achieve a response.

Seven patients proceeded to HSCT after receiving omacetaxine and sorafenib.

At a median follow-up of 7.1 months (range, 2.2 to 20.5), 4 patients were still in CR/CRi (3 patients after HSCT), and 1 patient who had relapsed was still alive.

The remaining 19 patients had died—14 due to relapse, 4 due to non-response (1 after re-treatment), and 1 due to HSCT.

The median leukemia-free survival was 88 days (range, 9-510), and the median overall survival was 228 days (range, 53 to 615).

Adverse events occurring after treatment with omacetaxine and sorafenib included fever (n=14), rash (n=8), hand-foot-skin reactions (n=6), pneumonia (n=2), neutropenic fever (n=1), and bacteremia (n=1).

The researchers said this study validated the principle and clinical relevance of in vitro drug testing and identified a drug combination that might improve the treatment of FLT3-ITD AML. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

A 2-drug combination has shown promise for treating patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Science Translational Medicine.

Researchers found that omacetaxine mepesuccinate (formerly known as homoharringtonine) exhibits preferential antileukemic activity against FLT3-ITD AML.

Subsequent preclinical experiments revealed that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors.

So researchers tested omacetaxine in combination with sorafenib in a phase 2 trial of patients with FLT3-ITD AML.

The combination produced complete responses (CRs) or CRs with incomplete hematologic recovery (CRis) in a majority of patients, and researchers said the treatment was well-tolerated.

Anskar Y. H. Leung, MD, PhD, of The University of Hong Kong, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team first performed an in vitro screen on AML patient samples to determine their responses to various drugs.

One of the compounds tested, the protein translation inhibitor omacetaxine mepesuccinate, showed strong antileukemic effects against FLT3-ITD AML. In fact, omacetaxine preferentially inhibited the growth of FLT3-ITD cell lines.

The researchers then found that omacetaxine synergizes with sorafenib and other FLT3 inhibitors to suppress leukemia growth in FLT3-ITD AML cell lines.

Omacetaxine and sorafenib in combination also prolonged survival in mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML (mice transplanted with MV4-11 or MOLM-13 cells).

Phase 2 trial

The researchers went on to test omacetaxine and sorafenib in a phase 2 trial. The trial enrolled 24 patients with FLT3-ITD AML and a median age of 50 (range, 21-76).

Most of the patients had relapsed or refractory disease, but 2 were unsuitable for induction chemotherapy because of advanced age and comorbidities.

The patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib continuously until intolerance, disease progression, or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Twenty patients (83.3%) achieved a CR or CRi at a median of 22 days (range, 18-55). Three patients did not respond, and 1 patient experienced a near-CRi—a reduction of blasts without complete clearance.

Fifteen of the responders relapsed, but 3 of these patients received omacetaxine and sorafenib again and achieved a CRi. One patient received re-treatment and failed to achieve a response.

Seven patients proceeded to HSCT after receiving omacetaxine and sorafenib.

At a median follow-up of 7.1 months (range, 2.2 to 20.5), 4 patients were still in CR/CRi (3 patients after HSCT), and 1 patient who had relapsed was still alive.

The remaining 19 patients had died—14 due to relapse, 4 due to non-response (1 after re-treatment), and 1 due to HSCT.

The median leukemia-free survival was 88 days (range, 9-510), and the median overall survival was 228 days (range, 53 to 615).

Adverse events occurring after treatment with omacetaxine and sorafenib included fever (n=14), rash (n=8), hand-foot-skin reactions (n=6), pneumonia (n=2), neutropenic fever (n=1), and bacteremia (n=1).

The researchers said this study validated the principle and clinical relevance of in vitro drug testing and identified a drug combination that might improve the treatment of FLT3-ITD AML. ![]()

‘Shared Learning’ Supports Pharmacist Program

Primary care physicians (PCPs) often don’t have the time to manage the complex medication needs of patients with chronic conditions. PCPs working in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) while caring for low-income at-risk patients also face “particularly large barriers,” according to the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ). But that lack of time can contribute to low patient adherence to medication regimens.

While clinical pharmacists can help, they may not be available to FQHCs, PCP offices, and other primary care settings. To address this, innovators in Ohio established a statewide consortium or “shared learning community” that provides the resources for FQHCs to offer pharmacist-led medication therapy management (MTM) services to patients with diabetes or hypertension. The collaborating organizations include the Ohio Association for Community Health Centers, the Health Services Advisory Group, and 6 Ohio-based colleges of pharmacy.

Related: Best Practices: Utilization of Oncology Pharmacists in the VA

The program developers, Jennifer Rodis, PharmD, BCPS, FAPhA, Assistant Dean for Outreach and Engagement at Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Barbara Pryor, MS, RD, LD, manager, Chronic Disease Section, Ohio Department of Health, reported on the consortium’s program and successes in AHRQ’s Health Care Innovations Exchange.

Program leaders meet with participating pharmacists to orient them; those pharmacists then introduce the program to clinicians and staff at their respective practice sites. Every month, the participating pharmacists check in with program leaders from the Ohio Department of Health, the Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Ohio Association of Community Health Centers to give status updates and get guidance and troubleshooting advice.

Related: VA Treats Patients’ Impatience With Clinical Pharmacists

The consortium has markedly increased the number of FQHCs offering pharmacist-led MTM services, as well as boosting awareness and interest in MTM. When the program began in 2013, very few of the 41 FQCHs in Ohio had pharmacist-led MTM programs, the AHRQ report says. Nine FQHCs now participate in the consortium.

During the first year, the 3 participating sites enrolled nearly 400 eligible patients with out-of-control hypertension or diabetes. By the end of that year, 68% of hypertensive patients had controlled their blood pressure and 45% of patients with diabetes were controlling their hemoglobin A1c. What’s more, the pharmacists providing MTM addressed 75 adverse drug events and remedied 145 potential events.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) often don’t have the time to manage the complex medication needs of patients with chronic conditions. PCPs working in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) while caring for low-income at-risk patients also face “particularly large barriers,” according to the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ). But that lack of time can contribute to low patient adherence to medication regimens.

While clinical pharmacists can help, they may not be available to FQHCs, PCP offices, and other primary care settings. To address this, innovators in Ohio established a statewide consortium or “shared learning community” that provides the resources for FQHCs to offer pharmacist-led medication therapy management (MTM) services to patients with diabetes or hypertension. The collaborating organizations include the Ohio Association for Community Health Centers, the Health Services Advisory Group, and 6 Ohio-based colleges of pharmacy.

Related: Best Practices: Utilization of Oncology Pharmacists in the VA

The program developers, Jennifer Rodis, PharmD, BCPS, FAPhA, Assistant Dean for Outreach and Engagement at Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Barbara Pryor, MS, RD, LD, manager, Chronic Disease Section, Ohio Department of Health, reported on the consortium’s program and successes in AHRQ’s Health Care Innovations Exchange.

Program leaders meet with participating pharmacists to orient them; those pharmacists then introduce the program to clinicians and staff at their respective practice sites. Every month, the participating pharmacists check in with program leaders from the Ohio Department of Health, the Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Ohio Association of Community Health Centers to give status updates and get guidance and troubleshooting advice.

Related: VA Treats Patients’ Impatience With Clinical Pharmacists

The consortium has markedly increased the number of FQHCs offering pharmacist-led MTM services, as well as boosting awareness and interest in MTM. When the program began in 2013, very few of the 41 FQCHs in Ohio had pharmacist-led MTM programs, the AHRQ report says. Nine FQHCs now participate in the consortium.

During the first year, the 3 participating sites enrolled nearly 400 eligible patients with out-of-control hypertension or diabetes. By the end of that year, 68% of hypertensive patients had controlled their blood pressure and 45% of patients with diabetes were controlling their hemoglobin A1c. What’s more, the pharmacists providing MTM addressed 75 adverse drug events and remedied 145 potential events.

Primary care physicians (PCPs) often don’t have the time to manage the complex medication needs of patients with chronic conditions. PCPs working in federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) while caring for low-income at-risk patients also face “particularly large barriers,” according to the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ). But that lack of time can contribute to low patient adherence to medication regimens.

While clinical pharmacists can help, they may not be available to FQHCs, PCP offices, and other primary care settings. To address this, innovators in Ohio established a statewide consortium or “shared learning community” that provides the resources for FQHCs to offer pharmacist-led medication therapy management (MTM) services to patients with diabetes or hypertension. The collaborating organizations include the Ohio Association for Community Health Centers, the Health Services Advisory Group, and 6 Ohio-based colleges of pharmacy.

Related: Best Practices: Utilization of Oncology Pharmacists in the VA

The program developers, Jennifer Rodis, PharmD, BCPS, FAPhA, Assistant Dean for Outreach and Engagement at Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Barbara Pryor, MS, RD, LD, manager, Chronic Disease Section, Ohio Department of Health, reported on the consortium’s program and successes in AHRQ’s Health Care Innovations Exchange.

Program leaders meet with participating pharmacists to orient them; those pharmacists then introduce the program to clinicians and staff at their respective practice sites. Every month, the participating pharmacists check in with program leaders from the Ohio Department of Health, the Ohio State University College of Pharmacy, and Ohio Association of Community Health Centers to give status updates and get guidance and troubleshooting advice.

Related: VA Treats Patients’ Impatience With Clinical Pharmacists

The consortium has markedly increased the number of FQHCs offering pharmacist-led MTM services, as well as boosting awareness and interest in MTM. When the program began in 2013, very few of the 41 FQCHs in Ohio had pharmacist-led MTM programs, the AHRQ report says. Nine FQHCs now participate in the consortium.

During the first year, the 3 participating sites enrolled nearly 400 eligible patients with out-of-control hypertension or diabetes. By the end of that year, 68% of hypertensive patients had controlled their blood pressure and 45% of patients with diabetes were controlling their hemoglobin A1c. What’s more, the pharmacists providing MTM addressed 75 adverse drug events and remedied 145 potential events.

Dark rash on chest

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP suspected tinea incognito (fungus caused by steroids because of a misdiagnosis) and wanted to perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation. (See video on how to perform a KOH preparation here.)

Unfortunately, the FP’s health system had removed microscopes from all of the offices because of regulatory issues from The Joint Commission. So the physician did the next best thing: He scraped the outer edge of the rash and put the scale in a sterile urine cup to send to the lab for fungal stain and culture. He recommended that the patient stop using the triamcinolone cream and start using a topical terbinafine (now an over-the-counter antifungal cream). He also made a mental note that most topical steroids only need to be used twice daily, even when the electronic medical record populates 3 times a day as the default setting.

The FP set up an appointment to see the patient the following week, hoping to have some answers from the laboratory. Two days later, the KOH with Calcofluor white fungal stain was positive for fungal elements. When the patient returned, the culture was growing Trichophyton rubrum. The patient noted that the rash had improved a little, but wondered if there was something stronger to help her.

Now that the diagnosis of tinea incognito was finalized, the FP offered her oral terbinafine. The patient did not have any liver disease and rarely drank alcohol, so the FP prescribed terbinafine 250 mg/d for 3 weeks. One month later, the patient was pleased that the itching, scaling, and raised areas had resolved. However, she asked if the dark area on her chest would remain that way forever. The FP told her that the postinflammatory hyperpigmentation would likely fade over time, but might not ever return to her normal skin color. The patient was upset, as she’d been wearing different clothes to hide the dark mark, and was hoping it would go away completely.

The FP suggested that she return in 2 months to see how her skin was doing. He told her about the use of an over-the-counter 3% hydroquinone cream, but warned her that it sometimes darkened skin rather than lightening it. He also suggested keeping the area protected from the sun and told her to stop using the bleaching cream if it caused irritation or darkened her skin.

This case is a dramatic example of how treating an unknown rash with topical steroids can have potentially permanent consequences for the patient. Even FPs who don't have microscopes or don't know how to create a KOH preparation can do what this doctor did (send a specimen to the laboratory). It’s always better to have a diagnosis before treatment, as topical steroids are not the answer to all pruritic rashes.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R, Jimenez A. Tinea corporis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:788-794.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Vedolizumab shows safety, efficacy for pediatric IBD

MONTREAL – Vedolizumab, 2 years out from its entry onto the U.S. market as an option for treating adults with inflammatory bowel disease, also has shown early safety and efficacy in 52 pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Retrospective review of a patients series assembled from three U.S. centers showed 13 (76%) ulcerative colitis patients in remission among 17 treated and followed for 14 weeks, the study’s primary outcome. Among 24 Crohn’s disease patients treated and followed for 14 weeks, 10 (42%) had remissions, Namita Singh, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

Treatment with vedolizumab (Entyvio), an anti-integrin with highly gut-specific activity that limits its systemic effects, was especially potent for the five patients in the series who were naive to treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent. All five patients were in remission at 14 weeks, said Dr. Singh, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“From this and other data it seems like there is a potential role for vedolizumab as first-line treatment” for selected patients, Dr. Singh said in an interview. “The attraction of vedolizumab is its gut selectivity.”

The American Gastroenterological Association lists vedolizumab as an equal alternative to an anti-TNF agent in its recommended algorithm for treating ulcerative colitis, but vedolizumab is not mentioned in the association’s posted guidance for treating Crohn’s disease. ”Prospective studies are needed” to generate more definitive evidence on how to use vedolizumab, she acknowledged, but added that pediatric gastroenterological societies “need to come up with guidelines on where to place vedolizumab.”Dr. Singh said she discusses with patients and their families the potential risks and benefits of the various treatment options available when inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) doesn’t respond to mesalamine: an anti-TNF agent, an immunomodulator like methotrexate or azathioprine, or vedolizumab. One important issue when deciding which drug class to try first is the cost of treatment and whether it will be covered by insurance.

The combined series included pediatric IBD patients less than 18 years old, with an actual median age of just under 15 years. They had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease for a median of 3 years. The 30 Crohn’s disease patients had received a median of two anti-TNF agents prior to starting vedolizumab, while the ulcerative colitis patients had received a median of one anti-TNF drug before vedolizumab. Three-quarters of the patients received the adult dose of 300 mg per infusion. A fifth of the patients received a dosage of 6 mg/kg, and the remaining patients received 5 mg/kg.

Although the 24 Crohn’s disease patients followed through 14 weeks of therapy had a 42% remission rate, the remission rate jumped sharply to more than 70% among the 11 patients followed to 30 weeks.

One limitation to vedolizumab is its relatively slow onset of action, slower than anti-TNF agents, which makes vedolizumab less suitable for patients with acute, severe colitis, although short-term improvement of acute colitis can be achieved with a corticosteroid when starting a patient on vedolizumab, Dr. Singh said. A trial currently underway is collecting prospective data on vedolizumab in pediatric IBD patients that could result in pediatric labeling for the drug, she added.

Until those data are available, current experience suggests vedolizumab “is good for ulcerative colitis patients,” she said. “Our data encourage us to continue” offering vedolizumab to selected pediatric IBD patients.

Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Janssen and Prometheus and received grant support from Janssen.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – Vedolizumab, 2 years out from its entry onto the U.S. market as an option for treating adults with inflammatory bowel disease, also has shown early safety and efficacy in 52 pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Retrospective review of a patients series assembled from three U.S. centers showed 13 (76%) ulcerative colitis patients in remission among 17 treated and followed for 14 weeks, the study’s primary outcome. Among 24 Crohn’s disease patients treated and followed for 14 weeks, 10 (42%) had remissions, Namita Singh, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

Treatment with vedolizumab (Entyvio), an anti-integrin with highly gut-specific activity that limits its systemic effects, was especially potent for the five patients in the series who were naive to treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent. All five patients were in remission at 14 weeks, said Dr. Singh, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“From this and other data it seems like there is a potential role for vedolizumab as first-line treatment” for selected patients, Dr. Singh said in an interview. “The attraction of vedolizumab is its gut selectivity.”

The American Gastroenterological Association lists vedolizumab as an equal alternative to an anti-TNF agent in its recommended algorithm for treating ulcerative colitis, but vedolizumab is not mentioned in the association’s posted guidance for treating Crohn’s disease. ”Prospective studies are needed” to generate more definitive evidence on how to use vedolizumab, she acknowledged, but added that pediatric gastroenterological societies “need to come up with guidelines on where to place vedolizumab.”Dr. Singh said she discusses with patients and their families the potential risks and benefits of the various treatment options available when inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) doesn’t respond to mesalamine: an anti-TNF agent, an immunomodulator like methotrexate or azathioprine, or vedolizumab. One important issue when deciding which drug class to try first is the cost of treatment and whether it will be covered by insurance.

The combined series included pediatric IBD patients less than 18 years old, with an actual median age of just under 15 years. They had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease for a median of 3 years. The 30 Crohn’s disease patients had received a median of two anti-TNF agents prior to starting vedolizumab, while the ulcerative colitis patients had received a median of one anti-TNF drug before vedolizumab. Three-quarters of the patients received the adult dose of 300 mg per infusion. A fifth of the patients received a dosage of 6 mg/kg, and the remaining patients received 5 mg/kg.

Although the 24 Crohn’s disease patients followed through 14 weeks of therapy had a 42% remission rate, the remission rate jumped sharply to more than 70% among the 11 patients followed to 30 weeks.

One limitation to vedolizumab is its relatively slow onset of action, slower than anti-TNF agents, which makes vedolizumab less suitable for patients with acute, severe colitis, although short-term improvement of acute colitis can be achieved with a corticosteroid when starting a patient on vedolizumab, Dr. Singh said. A trial currently underway is collecting prospective data on vedolizumab in pediatric IBD patients that could result in pediatric labeling for the drug, she added.

Until those data are available, current experience suggests vedolizumab “is good for ulcerative colitis patients,” she said. “Our data encourage us to continue” offering vedolizumab to selected pediatric IBD patients.

Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Janssen and Prometheus and received grant support from Janssen.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

MONTREAL – Vedolizumab, 2 years out from its entry onto the U.S. market as an option for treating adults with inflammatory bowel disease, also has shown early safety and efficacy in 52 pediatric patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Retrospective review of a patients series assembled from three U.S. centers showed 13 (76%) ulcerative colitis patients in remission among 17 treated and followed for 14 weeks, the study’s primary outcome. Among 24 Crohn’s disease patients treated and followed for 14 weeks, 10 (42%) had remissions, Namita Singh, MD, said at the World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition.

Treatment with vedolizumab (Entyvio), an anti-integrin with highly gut-specific activity that limits its systemic effects, was especially potent for the five patients in the series who were naive to treatment with an anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agent. All five patients were in remission at 14 weeks, said Dr. Singh, a pediatric gastroenterologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.

“From this and other data it seems like there is a potential role for vedolizumab as first-line treatment” for selected patients, Dr. Singh said in an interview. “The attraction of vedolizumab is its gut selectivity.”

The American Gastroenterological Association lists vedolizumab as an equal alternative to an anti-TNF agent in its recommended algorithm for treating ulcerative colitis, but vedolizumab is not mentioned in the association’s posted guidance for treating Crohn’s disease. ”Prospective studies are needed” to generate more definitive evidence on how to use vedolizumab, she acknowledged, but added that pediatric gastroenterological societies “need to come up with guidelines on where to place vedolizumab.”Dr. Singh said she discusses with patients and their families the potential risks and benefits of the various treatment options available when inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) doesn’t respond to mesalamine: an anti-TNF agent, an immunomodulator like methotrexate or azathioprine, or vedolizumab. One important issue when deciding which drug class to try first is the cost of treatment and whether it will be covered by insurance.

The combined series included pediatric IBD patients less than 18 years old, with an actual median age of just under 15 years. They had been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease for a median of 3 years. The 30 Crohn’s disease patients had received a median of two anti-TNF agents prior to starting vedolizumab, while the ulcerative colitis patients had received a median of one anti-TNF drug before vedolizumab. Three-quarters of the patients received the adult dose of 300 mg per infusion. A fifth of the patients received a dosage of 6 mg/kg, and the remaining patients received 5 mg/kg.

Although the 24 Crohn’s disease patients followed through 14 weeks of therapy had a 42% remission rate, the remission rate jumped sharply to more than 70% among the 11 patients followed to 30 weeks.

One limitation to vedolizumab is its relatively slow onset of action, slower than anti-TNF agents, which makes vedolizumab less suitable for patients with acute, severe colitis, although short-term improvement of acute colitis can be achieved with a corticosteroid when starting a patient on vedolizumab, Dr. Singh said. A trial currently underway is collecting prospective data on vedolizumab in pediatric IBD patients that could result in pediatric labeling for the drug, she added.

Until those data are available, current experience suggests vedolizumab “is good for ulcerative colitis patients,” she said. “Our data encourage us to continue” offering vedolizumab to selected pediatric IBD patients.

Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Janssen and Prometheus and received grant support from Janssen.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT WCPGHAN 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Fourteen weeks of treatment with vedolizumab produced remission in 76% of ulcerative colitis patients and 42% of Crohn’s disease patients.

Data source: Retrospective review of 52 pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease at seen at any of three U.S. centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Singh has been a consultant to Janssen and Prometheus and received grant support from Janssen.

‘Achilles heels’ open doors to myeloma advances

NEW YORK – Three “Achilles heels” of multiple myeloma offer exciting promise for additional advances that will begin to see therapeutic payoffs within the next year, according to Kenneth C. Anderson, MD.

The three targets – excess protein production, immune suppression, and genomic abnormalities – can be addressed by focusing on protein degradation, restoring anti–multiple myeloma immunity, and targeting and overcoming genomic abnormalities, respectively, Dr. Anderson of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston said at Imedex: Lymphoma & Myeloma, an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“So if you block those so-called DUBs, you block this same pathway upstream of the proteasome,” he said.

One DUB inhibitor (P5091) was shown in a preclinical trial to overcome bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma, as was another novel, more user-friendly agent (b-AP15) that blocks USP14/UCHL5 and can be active with immunomodulatory drugs. A clinical trial of b-AP15 is ongoing, Dr. Anderson said.

In contrast to the conventional approach of inhibiting proteins and signaling pathways needed for the survival of the cancer cells, a new technology called “degronimids” turns on the cereblon gene and delivers protein-degrading machinery to targeted proteins. Cereblon, a protein-degrading enzyme that forms part of the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, tags proteins in the cell for destruction, he noted.

As for immune suppression, he said, the selective plasma cell antigen BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen) is “probably a better target than either CD38 or SLAMF7,” and has already been targeted with an auristatin immunotoxin that induced strong anti–multiple myeloma effects.

“Excitingly, there is this concept of BCMA-BiTEs (B-cell maturation antigen–bispecific T-cell engagers) where we have one linkage of BCMA to the myeloma cell and CD3 attracting a local immune response,” he said.

Other promising new approaches with respect to immune suppression involve checkpoint inhibitors, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, he added.

Genomic abnormalities represent another potential vulnerability, and venetoclax (Venclexta) could prove to be the first precision medicine for multiple myeloma, he suggested.

In myeloma, “we are trying to treat the abnormality, but what about treating the genetic consequences of this abnormality,” he said, adding that clinical trials that target the consequences of genomic heterogeneity or instability are on the horizon.

Dr. Anderson reported serving as a consultant for, or receiving other financial support from Acetylon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, C4 Therapeutics, Celgene, Gilead, Millennium, and OncoPep.

NEW YORK – Three “Achilles heels” of multiple myeloma offer exciting promise for additional advances that will begin to see therapeutic payoffs within the next year, according to Kenneth C. Anderson, MD.

The three targets – excess protein production, immune suppression, and genomic abnormalities – can be addressed by focusing on protein degradation, restoring anti–multiple myeloma immunity, and targeting and overcoming genomic abnormalities, respectively, Dr. Anderson of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston said at Imedex: Lymphoma & Myeloma, an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“So if you block those so-called DUBs, you block this same pathway upstream of the proteasome,” he said.

One DUB inhibitor (P5091) was shown in a preclinical trial to overcome bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma, as was another novel, more user-friendly agent (b-AP15) that blocks USP14/UCHL5 and can be active with immunomodulatory drugs. A clinical trial of b-AP15 is ongoing, Dr. Anderson said.

In contrast to the conventional approach of inhibiting proteins and signaling pathways needed for the survival of the cancer cells, a new technology called “degronimids” turns on the cereblon gene and delivers protein-degrading machinery to targeted proteins. Cereblon, a protein-degrading enzyme that forms part of the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, tags proteins in the cell for destruction, he noted.

As for immune suppression, he said, the selective plasma cell antigen BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen) is “probably a better target than either CD38 or SLAMF7,” and has already been targeted with an auristatin immunotoxin that induced strong anti–multiple myeloma effects.

“Excitingly, there is this concept of BCMA-BiTEs (B-cell maturation antigen–bispecific T-cell engagers) where we have one linkage of BCMA to the myeloma cell and CD3 attracting a local immune response,” he said.

Other promising new approaches with respect to immune suppression involve checkpoint inhibitors, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, he added.

Genomic abnormalities represent another potential vulnerability, and venetoclax (Venclexta) could prove to be the first precision medicine for multiple myeloma, he suggested.

In myeloma, “we are trying to treat the abnormality, but what about treating the genetic consequences of this abnormality,” he said, adding that clinical trials that target the consequences of genomic heterogeneity or instability are on the horizon.

Dr. Anderson reported serving as a consultant for, or receiving other financial support from Acetylon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, C4 Therapeutics, Celgene, Gilead, Millennium, and OncoPep.

NEW YORK – Three “Achilles heels” of multiple myeloma offer exciting promise for additional advances that will begin to see therapeutic payoffs within the next year, according to Kenneth C. Anderson, MD.

The three targets – excess protein production, immune suppression, and genomic abnormalities – can be addressed by focusing on protein degradation, restoring anti–multiple myeloma immunity, and targeting and overcoming genomic abnormalities, respectively, Dr. Anderson of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston said at Imedex: Lymphoma & Myeloma, an international congress on hematologic malignancies.

“So if you block those so-called DUBs, you block this same pathway upstream of the proteasome,” he said.

One DUB inhibitor (P5091) was shown in a preclinical trial to overcome bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma, as was another novel, more user-friendly agent (b-AP15) that blocks USP14/UCHL5 and can be active with immunomodulatory drugs. A clinical trial of b-AP15 is ongoing, Dr. Anderson said.

In contrast to the conventional approach of inhibiting proteins and signaling pathways needed for the survival of the cancer cells, a new technology called “degronimids” turns on the cereblon gene and delivers protein-degrading machinery to targeted proteins. Cereblon, a protein-degrading enzyme that forms part of the ubiquitin E3 ligase complex, tags proteins in the cell for destruction, he noted.

As for immune suppression, he said, the selective plasma cell antigen BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen) is “probably a better target than either CD38 or SLAMF7,” and has already been targeted with an auristatin immunotoxin that induced strong anti–multiple myeloma effects.

“Excitingly, there is this concept of BCMA-BiTEs (B-cell maturation antigen–bispecific T-cell engagers) where we have one linkage of BCMA to the myeloma cell and CD3 attracting a local immune response,” he said.

Other promising new approaches with respect to immune suppression involve checkpoint inhibitors, histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, and chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, he added.

Genomic abnormalities represent another potential vulnerability, and venetoclax (Venclexta) could prove to be the first precision medicine for multiple myeloma, he suggested.

In myeloma, “we are trying to treat the abnormality, but what about treating the genetic consequences of this abnormality,” he said, adding that clinical trials that target the consequences of genomic heterogeneity or instability are on the horizon.

Dr. Anderson reported serving as a consultant for, or receiving other financial support from Acetylon, Bristol-Myers Squibb, C4 Therapeutics, Celgene, Gilead, Millennium, and OncoPep.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IMEDEX: LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA

Pulmonary embolism common in patients hospitalized for syncope

When specifically looked for, pulmonary embolism was identified in approximately 17% of adults hospitalized for a first episode of syncope, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most medical textbooks include pulmonary embolism (PE) in the differential diagnosis of syncope, but “current international guidelines, including those from the European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, pay little attention to establishing a diagnostic workup for PE in these patients. Hence, when a patient is admitted to a hospital for an episode of syncope, PE – a potentially fatal disease that can be effectively treated – is rarely considered as a possible cause,” said Paolo Prandoni, MD, PhD, of the vascular medicine unit, University of Padua (Italy), and his associates in the PESY (Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism in Patients With Syncope) trial.

The investigators used a systematic diagnostic work-up to determine the prevalence of PE in a cross-sectional study involving 560 adults hospitalized for syncope at 11 medical centers across Italy during a 2.5-year period. Most of these patients were elderly (mean age, 76 years), and most had clinical evidence indicating that a factor other than PE had caused their fainting. For this study, syncope was defined as a transient loss of consciousness with rapid onset, short duration (less than 1 minute), and spontaneous resolution, with obvious causes ruled out (such as epileptic seizure, stroke, or head trauma).

The “unexpectedly high” prevalence of PE was 17.3% overall, and it was consistent, ranging from 15% to 20%, across all 11 hospitals. The prevalence was even higher, at 25.4%, in the subgroup of 205 patients who had syncope of undetermined origin, as well as in 12.7% of the subgroup of 355 patients considered to have an alternative explanation for the disorder, Dr. Prandoni and his associates wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602172).

The researchers noted that this study likely underestimates the actual prevalence of PE among patients with syncope because it did not include patients who were not hospitalized, such as those who received only ambulatory care and those who presented to an emergency department but were not admitted.

The study was supported by the University of Padua. Dr. Prandoni and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

When specifically looked for, pulmonary embolism was identified in approximately 17% of adults hospitalized for a first episode of syncope, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most medical textbooks include pulmonary embolism (PE) in the differential diagnosis of syncope, but “current international guidelines, including those from the European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, pay little attention to establishing a diagnostic workup for PE in these patients. Hence, when a patient is admitted to a hospital for an episode of syncope, PE – a potentially fatal disease that can be effectively treated – is rarely considered as a possible cause,” said Paolo Prandoni, MD, PhD, of the vascular medicine unit, University of Padua (Italy), and his associates in the PESY (Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism in Patients With Syncope) trial.

The investigators used a systematic diagnostic work-up to determine the prevalence of PE in a cross-sectional study involving 560 adults hospitalized for syncope at 11 medical centers across Italy during a 2.5-year period. Most of these patients were elderly (mean age, 76 years), and most had clinical evidence indicating that a factor other than PE had caused their fainting. For this study, syncope was defined as a transient loss of consciousness with rapid onset, short duration (less than 1 minute), and spontaneous resolution, with obvious causes ruled out (such as epileptic seizure, stroke, or head trauma).

The “unexpectedly high” prevalence of PE was 17.3% overall, and it was consistent, ranging from 15% to 20%, across all 11 hospitals. The prevalence was even higher, at 25.4%, in the subgroup of 205 patients who had syncope of undetermined origin, as well as in 12.7% of the subgroup of 355 patients considered to have an alternative explanation for the disorder, Dr. Prandoni and his associates wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602172).

The researchers noted that this study likely underestimates the actual prevalence of PE among patients with syncope because it did not include patients who were not hospitalized, such as those who received only ambulatory care and those who presented to an emergency department but were not admitted.

The study was supported by the University of Padua. Dr. Prandoni and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

When specifically looked for, pulmonary embolism was identified in approximately 17% of adults hospitalized for a first episode of syncope, according to a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Most medical textbooks include pulmonary embolism (PE) in the differential diagnosis of syncope, but “current international guidelines, including those from the European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, pay little attention to establishing a diagnostic workup for PE in these patients. Hence, when a patient is admitted to a hospital for an episode of syncope, PE – a potentially fatal disease that can be effectively treated – is rarely considered as a possible cause,” said Paolo Prandoni, MD, PhD, of the vascular medicine unit, University of Padua (Italy), and his associates in the PESY (Prevalence of Pulmonary Embolism in Patients With Syncope) trial.

The investigators used a systematic diagnostic work-up to determine the prevalence of PE in a cross-sectional study involving 560 adults hospitalized for syncope at 11 medical centers across Italy during a 2.5-year period. Most of these patients were elderly (mean age, 76 years), and most had clinical evidence indicating that a factor other than PE had caused their fainting. For this study, syncope was defined as a transient loss of consciousness with rapid onset, short duration (less than 1 minute), and spontaneous resolution, with obvious causes ruled out (such as epileptic seizure, stroke, or head trauma).

The “unexpectedly high” prevalence of PE was 17.3% overall, and it was consistent, ranging from 15% to 20%, across all 11 hospitals. The prevalence was even higher, at 25.4%, in the subgroup of 205 patients who had syncope of undetermined origin, as well as in 12.7% of the subgroup of 355 patients considered to have an alternative explanation for the disorder, Dr. Prandoni and his associates wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602172).

The researchers noted that this study likely underestimates the actual prevalence of PE among patients with syncope because it did not include patients who were not hospitalized, such as those who received only ambulatory care and those who presented to an emergency department but were not admitted.

The study was supported by the University of Padua. Dr. Prandoni and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: When specifically looked for, pulmonary embolism was identified in approximately 17% of adults hospitalized for a first episode of syncope.

Major finding: The “unexpectedly high” prevalence of PE was 17.3% overall, and it was consistent, ranging from 15% to 20%, across all 11 hospitals in the study.

Data source: A cross-sectional study involving 560 adults hospitalized for syncope at 11 Italian medical centers during a 2.5 year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the University of Padua (Italy). Dr. Prandoni and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Older adults with active, remitted MDD may miss positive facial expressions

Older adults with both active and remitted major depressive disorder (MDD) may have a tougher time processing happy faces than do their counterparts without depression, a cross-sectional study of 59 veterans suggests.

“Sensitivity recognition of moderately intense happy expression appears to reflect a perceptual bias in major depression among older adults,” report Paulo R. Shiroma, MD, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and his associates.

The researchers recruited the subjects from October 2011 to September 2013, from primary care practices. The participants were divided into three groups – one with active major depressive disorder, another with MDD in remission, and one with no history of depression. Most of the veterans were white and married, and all were aged 55 years and older. Only veterans who were free of antidepressants or other psychotropic medications for at least 2 weeks were included in the study. They were compensated monetarily for participating in the study, reported Dr. Shiroma (Psychiatry Res. 2016 Sep 30:243;287-91).

Dr. Shiroma and his associates assessed the participants using several scales, including the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17). The veterans also were asked to complete a facial emotional recognition task, which involved looking at facial images depicting 12 neutral expressions and 48 happy expressions on a computer in a quiet room. Among other things, the participants were asked to respond as quickly as possible to the question: “Do you see a happy face?”

The researchers found a significant correlation between GDS-15 (P = .02) and HDRS-17 (P = .05) scores, and emotion recognition. Specifically, they found that the mean sensitivity among the never-depressed patients was 83.9%, compared with a mean sensitivity of 75.5% among the participants with active MDD and 75.4% among those with MDD that was in remission. No significant different differences were found in reaction time.

They cited several limitations. Veterans made up the entire study sample, and the results might not be generalizable. In addition, the prevalence of MDD in VA populations is 12%, compared with 7% in the general U.S. population, Dr. Shiroma and his associates wrote. Also, studies suggest that women may be more accurate in recognizing subtle facial displays of emotion.

Previous studies suggest that reducing “emotion-related negative bias” is associated with an improvement in depressive symptoms after 3 months of treatment with antidepressants. A recent trial analyzed the impact of emotion recognition training on mood among people with depressive symptoms using technology such as computers and smartphones (Trials. 2013 Jun 1;14:161). In light of those findings, Dr. Shiroma and his associates wrote, “similar intervention within the specific social and psychological aspects of the aging process could also be attempted.”

Dr. Shiroma reported having no conflicts of interest.

Older adults with both active and remitted major depressive disorder (MDD) may have a tougher time processing happy faces than do their counterparts without depression, a cross-sectional study of 59 veterans suggests.

“Sensitivity recognition of moderately intense happy expression appears to reflect a perceptual bias in major depression among older adults,” report Paulo R. Shiroma, MD, of the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and his associates.

The researchers recruited the subjects from October 2011 to September 2013, from primary care practices. The participants were divided into three groups – one with active major depressive disorder, another with MDD in remission, and one with no history of depression. Most of the veterans were white and married, and all were aged 55 years and older. Only veterans who were free of antidepressants or other psychotropic medications for at least 2 weeks were included in the study. They were compensated monetarily for participating in the study, reported Dr. Shiroma (Psychiatry Res. 2016 Sep 30:243;287-91).

Dr. Shiroma and his associates assessed the participants using several scales, including the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17). The veterans also were asked to complete a facial emotional recognition task, which involved looking at facial images depicting 12 neutral expressions and 48 happy expressions on a computer in a quiet room. Among other things, the participants were asked to respond as quickly as possible to the question: “Do you see a happy face?”

The researchers found a significant correlation between GDS-15 (P = .02) and HDRS-17 (P = .05) scores, and emotion recognition. Specifically, they found that the mean sensitivity among the never-depressed patients was 83.9%, compared with a mean sensitivity of 75.5% among the participants with active MDD and 75.4% among those with MDD that was in remission. No significant different differences were found in reaction time.

They cited several limitations. Veterans made up the entire study sample, and the results might not be generalizable. In addition, the prevalence of MDD in VA populations is 12%, compared with 7% in the general U.S. population, Dr. Shiroma and his associates wrote. Also, studies suggest that women may be more accurate in recognizing subtle facial displays of emotion.

Previous studies suggest that reducing “emotion-related negative bias” is associated with an improvement in depressive symptoms after 3 months of treatment with antidepressants. A recent trial analyzed the impact of emotion recognition training on mood among people with depressive symptoms using technology such as computers and smartphones (Trials. 2013 Jun 1;14:161). In light of those findings, Dr. Shiroma and his associates wrote, “similar intervention within the specific social and psychological aspects of the aging process could also be attempted.”

Dr. Shiroma reported having no conflicts of interest.