User login

Public speaking fundamentals. Presentation follow-up: What to do after the last slide is shown

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

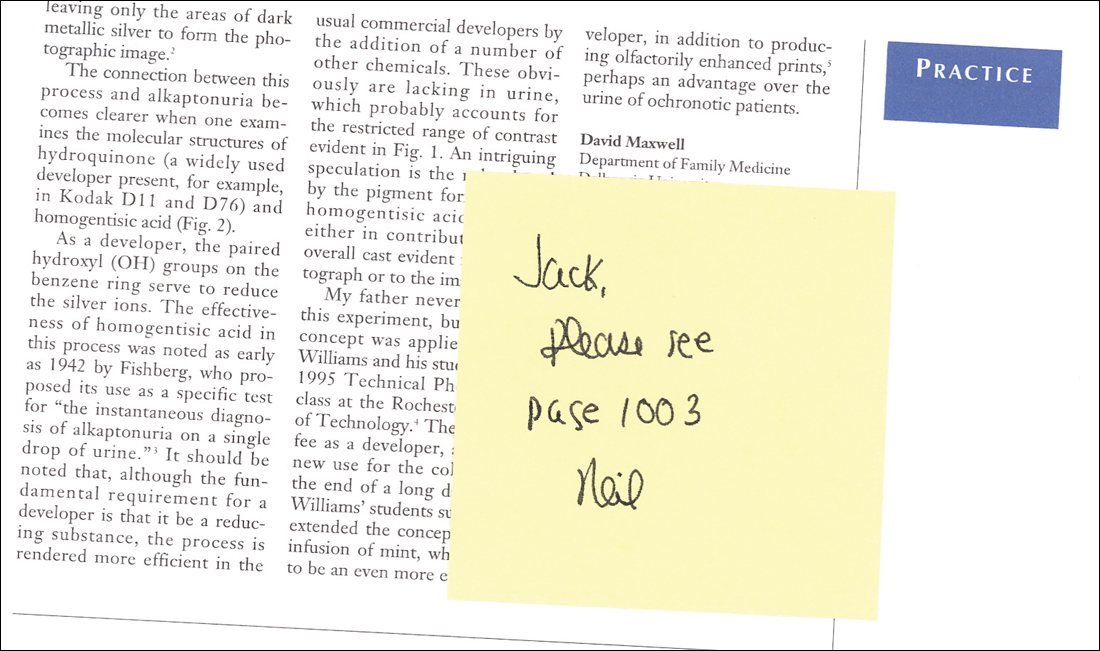

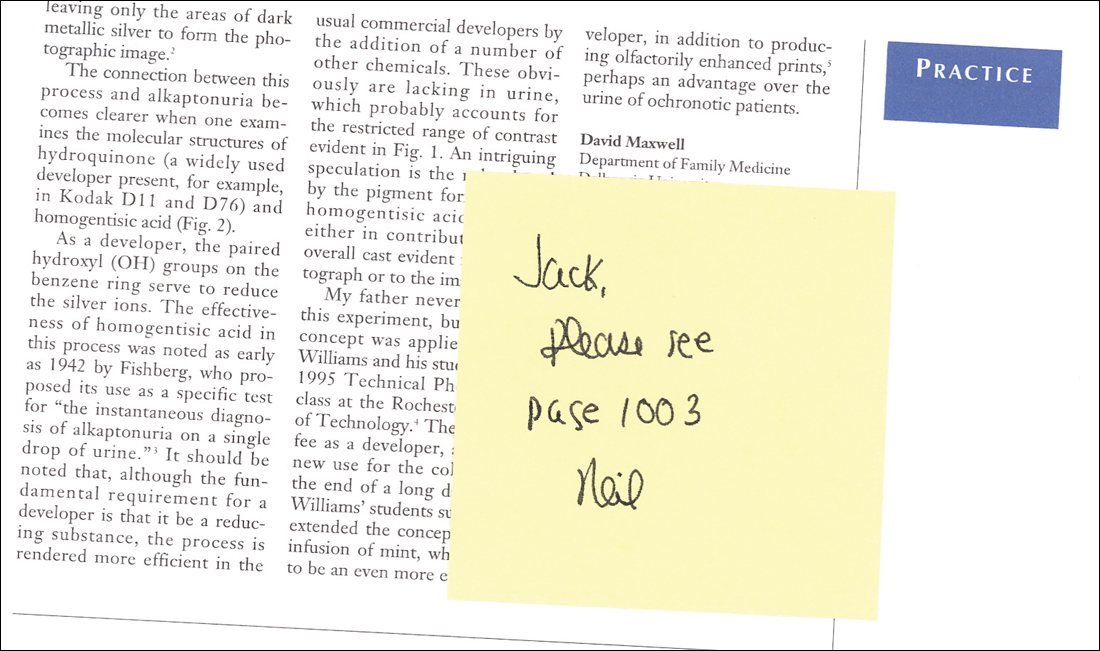

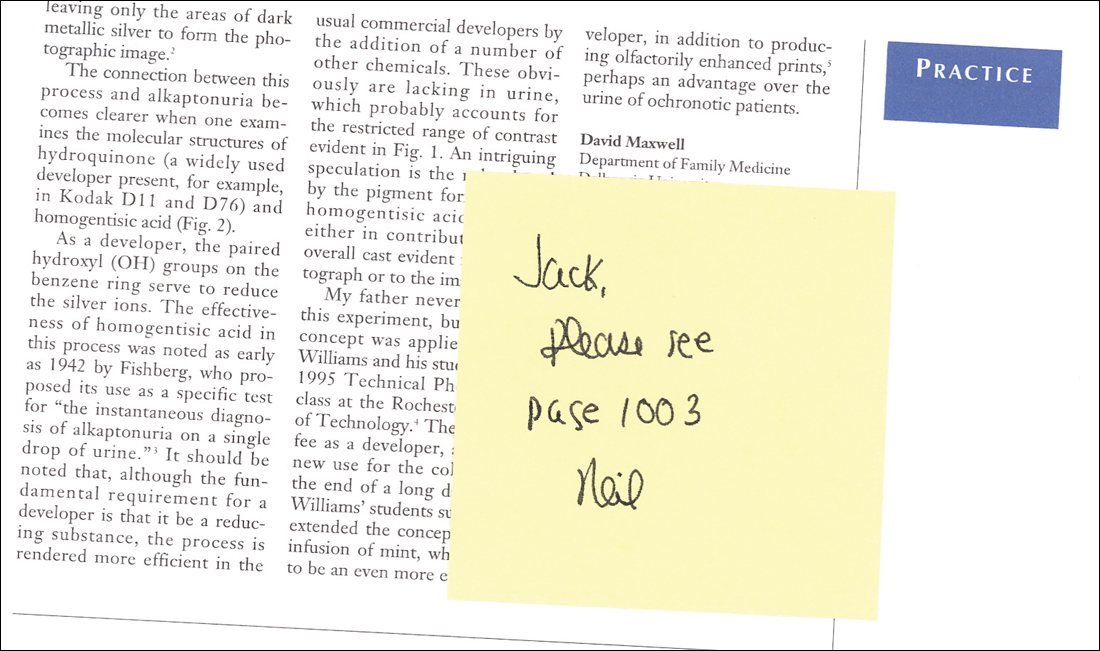

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This third article in a series on public speaking describes steps you can take immediately following the program to strengthen the impact of your diligent preparation (“Preparation: Tips that lead to a solid, engaging presentation.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[7]:31–36) and honed presentation (“The program: Key elements in capturing and holding audience attention.” OBG Manag. 2016;28[9]:46–50). Don’t overlook these details.

Find ways to stay in touch

You have concluded your talk. The audience response was enthusiastic and the brief Q&A session productive. But it is not over yet. Postpone putting away your computer and disconnecting the audiovisual equipment. Instead, mingle with the attendees—as you also did, we hope, before the program began. There is always more you can learn about your listeners. And, importantly, a few of them would undoubtedly like to ask you one-on-one about a case related to the topic you covered or about another problem in your area of expertise.

We suggest that, as part of your follow-up, you take the names of attendees you speak with. Make a note relevant to each one and plan to send a personal letter that perhaps includes an article you wrote or one published by a credible source. For example, if one of us (MK) gives a talk for a physician audience on a clinical topic, I will send the inquiring physician a note and an article on the topic, with the key sentences related to his or her question highlighted. A sticky note on the article’s front page directs the physician’s attention to the page containing the answer to his or her question (FIGURE). Using this simple technique can make you a value-added resource long after your presentation.

Alternatively, you could e-mail the article to a representative for the organization that you were speaking for. This makes you an asset to the representative, who will likely tell colleagues about your assistance, which could earn you a return speaking engagement.

Make sure, too, that you have an ample supply of business cards—the quickest and easiest way to give out your contact information.

You may also want to distribute a handout of your presentation. This could of course be a printout of your slide show presentation (assuming there are no copyright concerns). But we think it is better to distribute a single page with salient points you would like the audience to take away from your program. However you prepare your handout, be certain each page displays your name, address, phone numbers, and e-mail and website addresses.

Another suggestion: An unobtrusive way to obtain the names of those who attend your program is to collect their business cards in a container before the presentation and hold a drawing for a prize at the end of the program. We often give away a copy of one of our books, but any small gift would work.

Ask for feedback

If you are speaking on behalf of an organization or another sponsoring entity, it is helpful to ask the meeting planner what they thought of the program. Ask for constructive criticism and input on how you might improve the program. Also ask if you were able to get across your most important points.

Finally, send a note to the meeting planner or representative expressing your thanks for the invitation and offering to provide any additional information they might need or want.

Extend the reach of your message

If your talk would be appropriate for a broader audience, you could consider adapting it for publication. Be sure to understand the audience of the publication and review the selected journal’s guidance for authors.

If you do write an article, share it with your colleagues and perhaps your patients. You might also consider posting the article on your website. Yet another option would be to videotape your presentation, keeping it under 10 minutes, and upload it to the video-sharing website YouTube.

Bottom line. The payoff for your research and preparation need not end with the speaking engagement.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Analysis: CMS expects no MACRA pay cut for most small practices

Most small practices will see no change in their Medicare payments or perhaps even a bonus for participating in MACRA’s new Quality Payment Program (QPP) beginning in 2017.

Contrary to the initial proposed regulations from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, analysis of the final regulations shows that 90% of practices with one to nine clinicians should see no impact or even a pay increase in 2019 if they start participating in QPP next year, according to an agency analysis. The only way to fare worse would be to completely opt out of the program.

The sea change is based on two modifications to the proposed rule, according to Walter Gorski, director of regulatory affairs at the American College of Physicians. The first is the new flexibility for QPP participation for 2017. In September, CMS announced that any level of participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) – from reporting “some data” as a low-level test to full participation in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model – would result in no penalty or pay cut for physicians and other health care providers.

The second key is the higher threshold for exemption from reporting requirements. Under the proposed rule, providers who receive Medicare payments of more than $10,000 for 100 and see fewer Medicare patients had to participate; the final rule raises that to $30,000 or more or 100 or fewer Medicare patients. Mr. Gorski said this could result in 30% of physicians being exempt and therefore not having to face the penalties associated with the program.

In comparison, CMS expect 98.5% of practices with more than 100 clinicians to receive either a bonus payment or no bonus/penalty.

Most small practices will see no change in their Medicare payments or perhaps even a bonus for participating in MACRA’s new Quality Payment Program (QPP) beginning in 2017.

Contrary to the initial proposed regulations from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, analysis of the final regulations shows that 90% of practices with one to nine clinicians should see no impact or even a pay increase in 2019 if they start participating in QPP next year, according to an agency analysis. The only way to fare worse would be to completely opt out of the program.

The sea change is based on two modifications to the proposed rule, according to Walter Gorski, director of regulatory affairs at the American College of Physicians. The first is the new flexibility for QPP participation for 2017. In September, CMS announced that any level of participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) – from reporting “some data” as a low-level test to full participation in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model – would result in no penalty or pay cut for physicians and other health care providers.

The second key is the higher threshold for exemption from reporting requirements. Under the proposed rule, providers who receive Medicare payments of more than $10,000 for 100 and see fewer Medicare patients had to participate; the final rule raises that to $30,000 or more or 100 or fewer Medicare patients. Mr. Gorski said this could result in 30% of physicians being exempt and therefore not having to face the penalties associated with the program.

In comparison, CMS expect 98.5% of practices with more than 100 clinicians to receive either a bonus payment or no bonus/penalty.

Most small practices will see no change in their Medicare payments or perhaps even a bonus for participating in MACRA’s new Quality Payment Program (QPP) beginning in 2017.

Contrary to the initial proposed regulations from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, analysis of the final regulations shows that 90% of practices with one to nine clinicians should see no impact or even a pay increase in 2019 if they start participating in QPP next year, according to an agency analysis. The only way to fare worse would be to completely opt out of the program.

The sea change is based on two modifications to the proposed rule, according to Walter Gorski, director of regulatory affairs at the American College of Physicians. The first is the new flexibility for QPP participation for 2017. In September, CMS announced that any level of participation in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) – from reporting “some data” as a low-level test to full participation in an Advanced Alternative Payment Model – would result in no penalty or pay cut for physicians and other health care providers.

The second key is the higher threshold for exemption from reporting requirements. Under the proposed rule, providers who receive Medicare payments of more than $10,000 for 100 and see fewer Medicare patients had to participate; the final rule raises that to $30,000 or more or 100 or fewer Medicare patients. Mr. Gorski said this could result in 30% of physicians being exempt and therefore not having to face the penalties associated with the program.

In comparison, CMS expect 98.5% of practices with more than 100 clinicians to receive either a bonus payment or no bonus/penalty.

Access issues looming as more docs eye exit from clinical practice

Almost half (47.8%) of physicians surveyed are considering a change in how they practice medicine within the next 1-3 years, including cutting back on hours, retiring, switching to cash/concierge practice, working locum tenens, seeking a nonclinical health care job, seeking employment, or working part time.

That’s according to responses to the 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians Practice Patterns & Perspectives, a biennial survey commissioned by The Physicians Foundation and conducted by Merritt Hawkins. A total of 17,236 physicians responded to the survey.

The percentage looking to change is up from 43.6% in the 2014 survey, but down from the 50.2% of physicians who responded the same way in 2012.

Dr. Ray pointed to a number of findings in the survey that could be driving the growth in those looking to make a change.

“If you think about the last year, the clinical, administrative, and financial changes that have occurred have occurred at a whirlwind pace,” Dr. Ray said. “For instance, continued expansion of the Affordable Care Act has included as many as 20 million new people to the rolls at the same time we have a documented physician shortage where 80% of physicians say that they have all the patients that they can take care of. They are either at capacity or they are overextended.”

Other factors influencing physicians’ employment decisions include the transition to value-based payments under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), the transition to ICD-10, the growth of physician employment, the continued sale of private practices to hospitals and health systems, and the “businessification” of heath care.

“If any of these [changes] occurred in a period of time, it would be impactful,” he said. “But to have all occur simultaneously, we say now that to be a physician is to feel the ground shaking under your feet. This is the landscape in which the survey was taken.”

Given the volume of change, it is no surprise that physician morale is low, Dr. Ray said. “One of the first things that jumps out is morale. The question was ‘what best describes your professional morale about your current feelings and the current state of the medical profession?’ and 54% were somewhat or very negative; 46% were positive/somewhat positive/very positive. The very negatives were twice what the very positives were,” he noted.

Inadequate time to deliver quality care also was cited.

“Only 14% [of respondents] said that they have all the time that they need to provide the highest standards of care; 86% said that their time was either always limited, often limited, or sometimes limited,” Dr. Ray said.

Dr. Ray highlighted another question that provides insight into physicians’ dissatisfaction with their practice environment.

The survey asked, “To what degree is patient care in your practice adversely impacted by external factors such as third party authorizations, treatment protocols, EHR design, etc.”

“The critical term here is ‘adversely impacted,’ not just influenced, but adversely impacted,” Dr. Ray said. “Only 2.3% said not at all; 10% total said either not at all or a little bit. The rest said either somewhat, a good deal, or a great deal. In fact, 72% said a good deal or a great deal.”

All of this is leading to physician burnout, he said.

“I think it all bounces back to interference with the doctor/patient relationship and the fact that [physicians] feel like there are distractions within the practice of medicine due to the regulatory environment,” he said “They are not allowed to make decisions like they want to make in the best interest of their patients based on their training and their studying and their special experience with that patient. It creates this barrier with this professional satisfaction that they want to receive from taking care of patients.”

Almost half (47.8%) of physicians surveyed are considering a change in how they practice medicine within the next 1-3 years, including cutting back on hours, retiring, switching to cash/concierge practice, working locum tenens, seeking a nonclinical health care job, seeking employment, or working part time.

That’s according to responses to the 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians Practice Patterns & Perspectives, a biennial survey commissioned by The Physicians Foundation and conducted by Merritt Hawkins. A total of 17,236 physicians responded to the survey.

The percentage looking to change is up from 43.6% in the 2014 survey, but down from the 50.2% of physicians who responded the same way in 2012.

Dr. Ray pointed to a number of findings in the survey that could be driving the growth in those looking to make a change.

“If you think about the last year, the clinical, administrative, and financial changes that have occurred have occurred at a whirlwind pace,” Dr. Ray said. “For instance, continued expansion of the Affordable Care Act has included as many as 20 million new people to the rolls at the same time we have a documented physician shortage where 80% of physicians say that they have all the patients that they can take care of. They are either at capacity or they are overextended.”

Other factors influencing physicians’ employment decisions include the transition to value-based payments under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), the transition to ICD-10, the growth of physician employment, the continued sale of private practices to hospitals and health systems, and the “businessification” of heath care.

“If any of these [changes] occurred in a period of time, it would be impactful,” he said. “But to have all occur simultaneously, we say now that to be a physician is to feel the ground shaking under your feet. This is the landscape in which the survey was taken.”

Given the volume of change, it is no surprise that physician morale is low, Dr. Ray said. “One of the first things that jumps out is morale. The question was ‘what best describes your professional morale about your current feelings and the current state of the medical profession?’ and 54% were somewhat or very negative; 46% were positive/somewhat positive/very positive. The very negatives were twice what the very positives were,” he noted.

Inadequate time to deliver quality care also was cited.

“Only 14% [of respondents] said that they have all the time that they need to provide the highest standards of care; 86% said that their time was either always limited, often limited, or sometimes limited,” Dr. Ray said.

Dr. Ray highlighted another question that provides insight into physicians’ dissatisfaction with their practice environment.

The survey asked, “To what degree is patient care in your practice adversely impacted by external factors such as third party authorizations, treatment protocols, EHR design, etc.”

“The critical term here is ‘adversely impacted,’ not just influenced, but adversely impacted,” Dr. Ray said. “Only 2.3% said not at all; 10% total said either not at all or a little bit. The rest said either somewhat, a good deal, or a great deal. In fact, 72% said a good deal or a great deal.”

All of this is leading to physician burnout, he said.

“I think it all bounces back to interference with the doctor/patient relationship and the fact that [physicians] feel like there are distractions within the practice of medicine due to the regulatory environment,” he said “They are not allowed to make decisions like they want to make in the best interest of their patients based on their training and their studying and their special experience with that patient. It creates this barrier with this professional satisfaction that they want to receive from taking care of patients.”

Almost half (47.8%) of physicians surveyed are considering a change in how they practice medicine within the next 1-3 years, including cutting back on hours, retiring, switching to cash/concierge practice, working locum tenens, seeking a nonclinical health care job, seeking employment, or working part time.

That’s according to responses to the 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians Practice Patterns & Perspectives, a biennial survey commissioned by The Physicians Foundation and conducted by Merritt Hawkins. A total of 17,236 physicians responded to the survey.

The percentage looking to change is up from 43.6% in the 2014 survey, but down from the 50.2% of physicians who responded the same way in 2012.

Dr. Ray pointed to a number of findings in the survey that could be driving the growth in those looking to make a change.

“If you think about the last year, the clinical, administrative, and financial changes that have occurred have occurred at a whirlwind pace,” Dr. Ray said. “For instance, continued expansion of the Affordable Care Act has included as many as 20 million new people to the rolls at the same time we have a documented physician shortage where 80% of physicians say that they have all the patients that they can take care of. They are either at capacity or they are overextended.”

Other factors influencing physicians’ employment decisions include the transition to value-based payments under the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA), the transition to ICD-10, the growth of physician employment, the continued sale of private practices to hospitals and health systems, and the “businessification” of heath care.

“If any of these [changes] occurred in a period of time, it would be impactful,” he said. “But to have all occur simultaneously, we say now that to be a physician is to feel the ground shaking under your feet. This is the landscape in which the survey was taken.”

Given the volume of change, it is no surprise that physician morale is low, Dr. Ray said. “One of the first things that jumps out is morale. The question was ‘what best describes your professional morale about your current feelings and the current state of the medical profession?’ and 54% were somewhat or very negative; 46% were positive/somewhat positive/very positive. The very negatives were twice what the very positives were,” he noted.

Inadequate time to deliver quality care also was cited.

“Only 14% [of respondents] said that they have all the time that they need to provide the highest standards of care; 86% said that their time was either always limited, often limited, or sometimes limited,” Dr. Ray said.

Dr. Ray highlighted another question that provides insight into physicians’ dissatisfaction with their practice environment.

The survey asked, “To what degree is patient care in your practice adversely impacted by external factors such as third party authorizations, treatment protocols, EHR design, etc.”

“The critical term here is ‘adversely impacted,’ not just influenced, but adversely impacted,” Dr. Ray said. “Only 2.3% said not at all; 10% total said either not at all or a little bit. The rest said either somewhat, a good deal, or a great deal. In fact, 72% said a good deal or a great deal.”

All of this is leading to physician burnout, he said.

“I think it all bounces back to interference with the doctor/patient relationship and the fact that [physicians] feel like there are distractions within the practice of medicine due to the regulatory environment,” he said “They are not allowed to make decisions like they want to make in the best interest of their patients based on their training and their studying and their special experience with that patient. It creates this barrier with this professional satisfaction that they want to receive from taking care of patients.”

A tool to assess comportment and communication for hospitalists

With the rise of hospital medicine in the United States, the lion’s share of inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists. Both hospitals and hospitalist providers are committed to delivering excellent patient care, but to accomplish this goal, specific feedback is essential.

Patient satisfaction surveys that assess provider performance, such as Press Ganey (PG)1 and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS),2 do not truly provide feedback at the encounter level with valid attribution, and these data are not sent to providers in a timely manner.

In the analyses, the HMCCOT scores were moderately correlated with the hospitalists’ PG scores. Higher scores on the HMCCOT took an average of 13 minutes per patient encounter, giving further credence to the fact that excellent communication and comportment can be rapidly established at the bedside.

Patients’ complaints about doctors often relate to comportment and communication; the grievances are most commonly about feeling rushed, not being heard, and that information was not conveyed in a clear manner.4 Patient-centeredness has been shown to improve patient satisfaction as well as clinical outcomes, in part because they feel like partners in the mutually agreed upon treatment plans.5 Many of the components of the HMCCOT are at the heart of patient-centered care. While comportment may not be a frequently used term in patient care, respectful behaviors performed at the opening of any encounter [etiquette-based medicine which includes introducing oneself to patients and smiling] set the tone for the doctor-patient interaction.

Demonstrating genuine interest in the patient as a person is a core component of excellent patient care. Sir William Osler famously observed “It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.”6 A common method of “demonstrating interest in the patient as a person” recorded by the HMCCOT was physicians asking about patient’s personal history and of their interests. It is not difficult to fathom how knowing about patients’ personal interests and perspectives can help to most effectively engage them in establishing their goals of care and with therapeutic decisions.

Because hospitalists spend only a small proportion of their clinical time in direct patient care at the bedside, they need to make every moment count. HMCCOT allows for the identification of providers who are excellent in communication and comportment. Once identified, these exemplars can watch their peers and become the trainers to establish a culture of excellence.

Larger studies will be needed in the future to assess whether interventions that translate into improved comportment and communication among hospitalists will definitively augment patient satisfaction and ameliorate clinical outcomes.

1. Press Ganey. Accessed Dec. 15, 2015.

2. HCAHPS. Accessed Feb. 2, 2016.

3. Kotwal S, Khaliq W, Landis R, Wright S. Developing a comportment and communication tool for use in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2647.

4. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, Miller CS, Githens PB, Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994 Nov 23-30;272(20):1583-7.

5. Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, MD, 2007.

6. Taylor RB. White Coat Tales: Medicine’s Heroes, Heritage, and Misadventure. New York: Springer; 2007:126.

Susrutha Kotwal, MD, and Scott Wright, MD, are based in the department of medicine, division of hospital medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

With the rise of hospital medicine in the United States, the lion’s share of inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists. Both hospitals and hospitalist providers are committed to delivering excellent patient care, but to accomplish this goal, specific feedback is essential.

Patient satisfaction surveys that assess provider performance, such as Press Ganey (PG)1 and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS),2 do not truly provide feedback at the encounter level with valid attribution, and these data are not sent to providers in a timely manner.

In the analyses, the HMCCOT scores were moderately correlated with the hospitalists’ PG scores. Higher scores on the HMCCOT took an average of 13 minutes per patient encounter, giving further credence to the fact that excellent communication and comportment can be rapidly established at the bedside.

Patients’ complaints about doctors often relate to comportment and communication; the grievances are most commonly about feeling rushed, not being heard, and that information was not conveyed in a clear manner.4 Patient-centeredness has been shown to improve patient satisfaction as well as clinical outcomes, in part because they feel like partners in the mutually agreed upon treatment plans.5 Many of the components of the HMCCOT are at the heart of patient-centered care. While comportment may not be a frequently used term in patient care, respectful behaviors performed at the opening of any encounter [etiquette-based medicine which includes introducing oneself to patients and smiling] set the tone for the doctor-patient interaction.

Demonstrating genuine interest in the patient as a person is a core component of excellent patient care. Sir William Osler famously observed “It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.”6 A common method of “demonstrating interest in the patient as a person” recorded by the HMCCOT was physicians asking about patient’s personal history and of their interests. It is not difficult to fathom how knowing about patients’ personal interests and perspectives can help to most effectively engage them in establishing their goals of care and with therapeutic decisions.

Because hospitalists spend only a small proportion of their clinical time in direct patient care at the bedside, they need to make every moment count. HMCCOT allows for the identification of providers who are excellent in communication and comportment. Once identified, these exemplars can watch their peers and become the trainers to establish a culture of excellence.

Larger studies will be needed in the future to assess whether interventions that translate into improved comportment and communication among hospitalists will definitively augment patient satisfaction and ameliorate clinical outcomes.

1. Press Ganey. Accessed Dec. 15, 2015.

2. HCAHPS. Accessed Feb. 2, 2016.

3. Kotwal S, Khaliq W, Landis R, Wright S. Developing a comportment and communication tool for use in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2647.

4. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, Miller CS, Githens PB, Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994 Nov 23-30;272(20):1583-7.

5. Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, MD, 2007.

6. Taylor RB. White Coat Tales: Medicine’s Heroes, Heritage, and Misadventure. New York: Springer; 2007:126.

Susrutha Kotwal, MD, and Scott Wright, MD, are based in the department of medicine, division of hospital medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

With the rise of hospital medicine in the United States, the lion’s share of inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists. Both hospitals and hospitalist providers are committed to delivering excellent patient care, but to accomplish this goal, specific feedback is essential.

Patient satisfaction surveys that assess provider performance, such as Press Ganey (PG)1 and Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS),2 do not truly provide feedback at the encounter level with valid attribution, and these data are not sent to providers in a timely manner.

In the analyses, the HMCCOT scores were moderately correlated with the hospitalists’ PG scores. Higher scores on the HMCCOT took an average of 13 minutes per patient encounter, giving further credence to the fact that excellent communication and comportment can be rapidly established at the bedside.

Patients’ complaints about doctors often relate to comportment and communication; the grievances are most commonly about feeling rushed, not being heard, and that information was not conveyed in a clear manner.4 Patient-centeredness has been shown to improve patient satisfaction as well as clinical outcomes, in part because they feel like partners in the mutually agreed upon treatment plans.5 Many of the components of the HMCCOT are at the heart of patient-centered care. While comportment may not be a frequently used term in patient care, respectful behaviors performed at the opening of any encounter [etiquette-based medicine which includes introducing oneself to patients and smiling] set the tone for the doctor-patient interaction.

Demonstrating genuine interest in the patient as a person is a core component of excellent patient care. Sir William Osler famously observed “It is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has.”6 A common method of “demonstrating interest in the patient as a person” recorded by the HMCCOT was physicians asking about patient’s personal history and of their interests. It is not difficult to fathom how knowing about patients’ personal interests and perspectives can help to most effectively engage them in establishing their goals of care and with therapeutic decisions.

Because hospitalists spend only a small proportion of their clinical time in direct patient care at the bedside, they need to make every moment count. HMCCOT allows for the identification of providers who are excellent in communication and comportment. Once identified, these exemplars can watch their peers and become the trainers to establish a culture of excellence.

Larger studies will be needed in the future to assess whether interventions that translate into improved comportment and communication among hospitalists will definitively augment patient satisfaction and ameliorate clinical outcomes.

1. Press Ganey. Accessed Dec. 15, 2015.

2. HCAHPS. Accessed Feb. 2, 2016.

3. Kotwal S, Khaliq W, Landis R, Wright S. Developing a comportment and communication tool for use in hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2647.

4. Hickson GB, Clayton EW, Entman SS, Miller CS, Githens PB, Whetten-Goldstein K, Sloan FA. Obstetricians’ prior malpractice experience and patients’ satisfaction with care. JAMA. 1994 Nov 23-30;272(20):1583-7.

5. Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient-centered communication in cancer care: promoting healing and reducing suffering. National Cancer Institute, NIH Publication No. 07-6225. Bethesda, MD, 2007.

6. Taylor RB. White Coat Tales: Medicine’s Heroes, Heritage, and Misadventure. New York: Springer; 2007:126.

Susrutha Kotwal, MD, and Scott Wright, MD, are based in the department of medicine, division of hospital medicine, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center and Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Benefits of dental sealant programs for low-income children exceed costs

Cavities and fillings were approximately three times more likely among low-income children aged 7-11 years whose teeth were not treated with dental sealants, compared to those treated with sealants, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2011-2014.

Overall, 43% of children and 39% of low-income children in the United States were treated at least once with dental sealant.

Although sealant use in children increased overall from 31% to 44% in a comparison of 1999-2004 and 2011-2014 NHANES data, sealant use was less common among low-income children compared with high-income children (39% vs. 48%) in the 2011-2014 period after increases of 16% and 9%, respectively, during 2011-2014.

School-based programs to provide sealants could increase their use among low-income children, wrote Susan O. Griffin, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her associates. The researchers reviewed data from 1,371 low-income children aged 6-11 years, and found that 60% (approximately 6.5 million children), had not been treated with dental sealants. “The systematic review of economic evaluations of school-based sealant programs (SBSP) conducted for the Task Force found that SBSP became cost-saving within 2 years of placing sealants,” the researchers noted.

The data were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2016 Oct 21;65[41];1141-5).

Cavities and fillings were approximately three times more likely among low-income children aged 7-11 years whose teeth were not treated with dental sealants, compared to those treated with sealants, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2011-2014.

Overall, 43% of children and 39% of low-income children in the United States were treated at least once with dental sealant.

Although sealant use in children increased overall from 31% to 44% in a comparison of 1999-2004 and 2011-2014 NHANES data, sealant use was less common among low-income children compared with high-income children (39% vs. 48%) in the 2011-2014 period after increases of 16% and 9%, respectively, during 2011-2014.

School-based programs to provide sealants could increase their use among low-income children, wrote Susan O. Griffin, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her associates. The researchers reviewed data from 1,371 low-income children aged 6-11 years, and found that 60% (approximately 6.5 million children), had not been treated with dental sealants. “The systematic review of economic evaluations of school-based sealant programs (SBSP) conducted for the Task Force found that SBSP became cost-saving within 2 years of placing sealants,” the researchers noted.

The data were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2016 Oct 21;65[41];1141-5).

Cavities and fillings were approximately three times more likely among low-income children aged 7-11 years whose teeth were not treated with dental sealants, compared to those treated with sealants, based on data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2011-2014.

Overall, 43% of children and 39% of low-income children in the United States were treated at least once with dental sealant.

Although sealant use in children increased overall from 31% to 44% in a comparison of 1999-2004 and 2011-2014 NHANES data, sealant use was less common among low-income children compared with high-income children (39% vs. 48%) in the 2011-2014 period after increases of 16% and 9%, respectively, during 2011-2014.

School-based programs to provide sealants could increase their use among low-income children, wrote Susan O. Griffin, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and her associates. The researchers reviewed data from 1,371 low-income children aged 6-11 years, and found that 60% (approximately 6.5 million children), had not been treated with dental sealants. “The systematic review of economic evaluations of school-based sealant programs (SBSP) conducted for the Task Force found that SBSP became cost-saving within 2 years of placing sealants,” the researchers noted.

The data were published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2016 Oct 21;65[41];1141-5).

FROM MMWR

CMS offering educational webinars on MACRA

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is offering a pair of webinars aimed at helping physicians navigate the new regulation that operationalizes the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA).

The first webinar, scheduled for Oct. 26, will provide an overview of the two components of the Quality Payment Program – the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs).

The second webinar, scheduled for Nov. 15, is targeted to Medicare Part B fee-for-service clinicians, office managers and administrators, state and national associations that represent health care providers, and other stakeholders and will feature a question-and-answer session.

The webinars are part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to help educate practitioners on the provisions of the final MACRA regulation, which was issued on Oct. 14. CMS also recently launched a website to help in that regard.

Enhanced recovery pathways in gynecology

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Enhanced recovery surgical principles were first described in the 1990s.1 These principles postulate that the body’s stress response to surgical injury and deviation from normal physiology is the source of postoperative morbidity. Thus, enhanced recovery programs are designed around perioperative interventions that mitigate and help the body cope with the surgical stress response.

Many of these interventions run counter to traditional perioperative care paradigms. Enhanced recovery protocols are diverse but have common themes of avoiding preoperative fasting and bowel preparation, early oral intake, limiting use of drains and catheters, multimodal analgesia, early ambulation, and prioritizing euvolemia and normothermia. Individual interventions in these areas are combined to create a master protocol, which is implemented as a bundle to improve surgical outcomes.

Current components

Minimizing preoperative fasting, early postoperative refeeding, and preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks are all key aspects of enhanced recovery protocols. “NPO after midnight” has been a longstanding rule due to the risk of aspiration with intubation. However, a Cochrane review found no evidence that a shortened period of fasting was associated with an increased risk of aspiration or related morbidity. Currently, the American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends only a 6-hour fast for solid foods and 2 hours for clear liquids.2,3

Preoperative fasting causes depletion of glycogen stores leading to insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, which are both associated with postoperative complications and morbidity.4 Preoperative carbohydrate-loading drinks can reverse some of the effects of limited preoperative fasting including preventing insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.5

Postoperative fasting should also be avoided. Early enteral intake is very important to decrease time spent in a catabolic state and decrease insulin resistance. In gynecology patients, early refeeding is associated with a faster return of bowel function and a decreased length of stay without an increase in postoperative complications.6 Notably, patients undergoing early feeding consistently experience more nausea and vomiting, but this is not associated with complications.7

The fluid management goal in enhanced recovery is to maintain perioperative euvolemia, as both hypovolemia and hypervolemia have negative physiologic consequences. When studied, fluid protocols designed to minimize the use of postoperative fluids have resulted in decreased cardiopulmonary complications, decreased postoperative morbidity, faster return of bowel function, and shorter hospital stays.8 Given the morbidity associated with fluid overload, enhanced recovery protocols recommend that minimal fluids be given in the operating room and intravenous fluids be removed as quickly as possible, often with first oral intake or postoperative day 1 at the latest.

Engagement of the patient in their perioperative recovery with patient education materials and expectations for postoperative tasks, such as early refeeding, spirometry, and ambulation are all important components of enhanced recovery. Patients become partners in achieving postoperative milestones, and this results in improved outcomes such as decreased pain scores and shorter recoveries.

Evidence in gynecology

Enhanced recovery has been studied in many surgical disciplines including urology, colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, and gynecology. High-quality studies of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy patients have consistently found a decrease in length of stay with no difference in readmission or postoperative complication rates.9 An interesting study also found that an enhanced recovery program was associated with decreased nursing time required for patient care.10

For ovarian cancer patients, enhanced recovery is associated with decreased length of stay, decreased time to return of bowel function, and improved quality of life. Enhanced recovery is also cost saving, saving $257-$697 per vaginal hysterectomy patient and $5,410-$7,600 per ovarian cancer patient.11

Enhanced recovery protocols are safe, evidenced based, cost saving, and are increasingly being adopted as clinicians and health systems become aware of their benefits.

References

1. Br J Anaesth. 1997 May;78(5):606-17.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 Oct 20;(4):CD004423.

3. Anesthesiology. 1999 Mar;90(3):896-905.

4. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 Jan;214(1):68-80.

5. Clin Nutr. 1998 Apr;17(2):65-71.

6. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD004508.

7. Obstet Gynecol. 1998 Jul;92(1):94-7.

8. Br J Surg. 2009 Apr;96(4):331-41.

9. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Aug;122(2 Pt 1):319-28.

10. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009 Jun;18(3):236-40.

11. Gynecol Oncol. 2008 Feb;108(2):282-6.

Dr. Gehrig is professor and director of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Barber is a third-year fellow in gynecologic oncology at the university. They reported having no financial disclosures relevant to this column. Email them at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

FDA approves atezolizumab for advanced NSCLC

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blocking antibody atezolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy.

The FDA previously approved atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has progressed after platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval for treatment of NSCLC was based on results from the phase III OAK and phase II POPLAR trials that enrolled a total of 1,137 patients with NSCLC whose disease had progressed on platinum-containing chemotherapy. In OAK, median overall survival for patients assigned to atezolizumab was 13.8 months, compared with 9.6 months for patients assigned to docetaxel, as recently reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

In POPLAR, overall survival was 12.6 months for patients receiving atezolizumab versus 9.7 months for those assigned to docetaxel, as reported at the European Cancer Congress in 2015.

The most common (greater than or equal to 20%) adverse reactions in patients treated with atezolizumab were fatigue, decreased appetite, dyspnea, cough, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, and constipation, according to the FDA website. The most common (greater than or equal to 2%) grade 3-4 adverse events in patients treated with atezolizumab were dyspnea, pneumonia, hypoxia, hyponatremia, fatigue, anemia, musculoskeletal pain, AST increase, ALT increase, dysphagia, and arthralgia. Clinically significant immune-related adverse events for patients receiving atezolizumab have included pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis, and thyroid disease.

The recommended dose is 1,200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients with EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations should not receive atezolizumab before having disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these aberrations, the FDA said.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blocking antibody atezolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy.

The FDA previously approved atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has progressed after platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval for treatment of NSCLC was based on results from the phase III OAK and phase II POPLAR trials that enrolled a total of 1,137 patients with NSCLC whose disease had progressed on platinum-containing chemotherapy. In OAK, median overall survival for patients assigned to atezolizumab was 13.8 months, compared with 9.6 months for patients assigned to docetaxel, as recently reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

In POPLAR, overall survival was 12.6 months for patients receiving atezolizumab versus 9.7 months for those assigned to docetaxel, as reported at the European Cancer Congress in 2015.

The most common (greater than or equal to 20%) adverse reactions in patients treated with atezolizumab were fatigue, decreased appetite, dyspnea, cough, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, and constipation, according to the FDA website. The most common (greater than or equal to 2%) grade 3-4 adverse events in patients treated with atezolizumab were dyspnea, pneumonia, hypoxia, hyponatremia, fatigue, anemia, musculoskeletal pain, AST increase, ALT increase, dysphagia, and arthralgia. Clinically significant immune-related adverse events for patients receiving atezolizumab have included pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis, and thyroid disease.

The recommended dose is 1,200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients with EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations should not receive atezolizumab before having disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these aberrations, the FDA said.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) blocking antibody atezolizumab for the treatment of patients with metastatic non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) whose disease has progressed during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy.

The FDA previously approved atezolizumab (Tecentriq) for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma that has progressed after platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Approval for treatment of NSCLC was based on results from the phase III OAK and phase II POPLAR trials that enrolled a total of 1,137 patients with NSCLC whose disease had progressed on platinum-containing chemotherapy. In OAK, median overall survival for patients assigned to atezolizumab was 13.8 months, compared with 9.6 months for patients assigned to docetaxel, as recently reported at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress.

In POPLAR, overall survival was 12.6 months for patients receiving atezolizumab versus 9.7 months for those assigned to docetaxel, as reported at the European Cancer Congress in 2015.

The most common (greater than or equal to 20%) adverse reactions in patients treated with atezolizumab were fatigue, decreased appetite, dyspnea, cough, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, and constipation, according to the FDA website. The most common (greater than or equal to 2%) grade 3-4 adverse events in patients treated with atezolizumab were dyspnea, pneumonia, hypoxia, hyponatremia, fatigue, anemia, musculoskeletal pain, AST increase, ALT increase, dysphagia, and arthralgia. Clinically significant immune-related adverse events for patients receiving atezolizumab have included pneumonitis, hepatitis, colitis, and thyroid disease.

The recommended dose is 1,200 mg administered as an intravenous infusion over 60 minutes every 3 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Patients with EGFR or ALK genomic tumor aberrations should not receive atezolizumab before having disease progression on FDA-approved therapy for these aberrations, the FDA said.

Full prescribing information is available on the FDA website.

Psychological stress did not harm IVF outcomes

SALT LAKE CITY – Self-reported psychological distress and biological markers of stress did not affect the chances of pregnancy after in vitro fertilization, according to a single-center prospective cohort study of 186 women.

Rates of ultrasound-confirmed pregnancy were 36% among first-time IVF recipients and 30% among women undergoing their third round of IVF, and did not differ based on self-reported depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, or serum levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, or interleukin-6, Maria Costantini-Ferrando, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Nonetheless, IVF recipients reported more depressive symptoms than oocyte donors did, especially after a negative pregnancy test, reported Dr. Costantini-Ferrando, a reproductive endocrinologist in Englewood, N.J.

“Patients undergoing IVF do experience real psychological distress. The efficiency of IVF in controlling the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes may overshadow any deleterious effect of heightened stress, but it will not eliminate patients’ experience of it,” she said.

Patients need support and follow-up to help lessen the psychological burden of treatment and decrease drop-out, she said.

Women in the study were aged 22-44 years, and the IVF recipients had a mean age of 37 years. In all, 75 women (40%) were first-time IVF patients, 29% were undergoing their third cycle of IVF, and 31% were oocyte donors. Among the IVF recipients, 22% were in psychotherapy, and 4% were on psychotropic medications. None of the women had other medical comorbidities. Patients were assessed at baseline, time of oocyte retrieval, time of embryo transfer, and on the day of the pregnancy test.

Patients with infertility reported significantly worse depressive symptoms at baseline compared with oocyte donors, with average Beck Depression Inventory scores of 11, compared with 2.3 (P less than .01). This difference persisted at the time of vaginal oocyte retrieval. First-time and third-time IVF recipients tended to have similar Beck Depression Inventory scores until pregnancy testing, when the average scores of third-time recipients increased by about five additional points.

Scores on the daily stress questionnaire echoed these findings. Patients who were receiving IVF reported significantly more stress than did oocyte donors, with the highest increase at the time of the pregnancy test among patients with previous IVF failures. However, both recipients and donors reported mild to moderate anxiety based on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Dr. Costantini-Ferrando said.

All groups had low interleukin-6 levels when starting IVF, but donors had the highest levels of both ACTH and cortisol. Levels of these hormones dropped over time, and then rose at the time of pregnancy testing. That trend suggests that IVF was an acute “procedural” stressor for both recipients and donors, but that the magnitude of the stress response lessened somewhat over time with repeated exposure to the stressor, Dr. Costantini-Ferrando noted.

“The complexity of this interaction may explain why it is difficult to elucidate the true impact of stress on IVF outcome,” she said.

Ultimately, these findings support a shift in focus, she added. Instead of asking if stress decreases reproductive potential, clinicians and researchers can instead explore how to address psychological distress to maximize reproductive potential. “This is important to keep patients engaged in infertility treatment and facilitate the difficult process of decision making during treatment,” she added.

The paper won a prize from the ASRM Mental Health Professional Group.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding for the study. Dr. Costantini-Ferrando reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SALT LAKE CITY – Self-reported psychological distress and biological markers of stress did not affect the chances of pregnancy after in vitro fertilization, according to a single-center prospective cohort study of 186 women.

Rates of ultrasound-confirmed pregnancy were 36% among first-time IVF recipients and 30% among women undergoing their third round of IVF, and did not differ based on self-reported depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, or serum levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, or interleukin-6, Maria Costantini-Ferrando, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.

Nonetheless, IVF recipients reported more depressive symptoms than oocyte donors did, especially after a negative pregnancy test, reported Dr. Costantini-Ferrando, a reproductive endocrinologist in Englewood, N.J.

“Patients undergoing IVF do experience real psychological distress. The efficiency of IVF in controlling the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axes may overshadow any deleterious effect of heightened stress, but it will not eliminate patients’ experience of it,” she said.

Patients need support and follow-up to help lessen the psychological burden of treatment and decrease drop-out, she said.

Women in the study were aged 22-44 years, and the IVF recipients had a mean age of 37 years. In all, 75 women (40%) were first-time IVF patients, 29% were undergoing their third cycle of IVF, and 31% were oocyte donors. Among the IVF recipients, 22% were in psychotherapy, and 4% were on psychotropic medications. None of the women had other medical comorbidities. Patients were assessed at baseline, time of oocyte retrieval, time of embryo transfer, and on the day of the pregnancy test.

Patients with infertility reported significantly worse depressive symptoms at baseline compared with oocyte donors, with average Beck Depression Inventory scores of 11, compared with 2.3 (P less than .01). This difference persisted at the time of vaginal oocyte retrieval. First-time and third-time IVF recipients tended to have similar Beck Depression Inventory scores until pregnancy testing, when the average scores of third-time recipients increased by about five additional points.

Scores on the daily stress questionnaire echoed these findings. Patients who were receiving IVF reported significantly more stress than did oocyte donors, with the highest increase at the time of the pregnancy test among patients with previous IVF failures. However, both recipients and donors reported mild to moderate anxiety based on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Dr. Costantini-Ferrando said.

All groups had low interleukin-6 levels when starting IVF, but donors had the highest levels of both ACTH and cortisol. Levels of these hormones dropped over time, and then rose at the time of pregnancy testing. That trend suggests that IVF was an acute “procedural” stressor for both recipients and donors, but that the magnitude of the stress response lessened somewhat over time with repeated exposure to the stressor, Dr. Costantini-Ferrando noted.

“The complexity of this interaction may explain why it is difficult to elucidate the true impact of stress on IVF outcome,” she said.

Ultimately, these findings support a shift in focus, she added. Instead of asking if stress decreases reproductive potential, clinicians and researchers can instead explore how to address psychological distress to maximize reproductive potential. “This is important to keep patients engaged in infertility treatment and facilitate the difficult process of decision making during treatment,” she added.

The paper won a prize from the ASRM Mental Health Professional Group.

The National Institutes of Health provided funding for the study. Dr. Costantini-Ferrando reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SALT LAKE CITY – Self-reported psychological distress and biological markers of stress did not affect the chances of pregnancy after in vitro fertilization, according to a single-center prospective cohort study of 186 women.

Rates of ultrasound-confirmed pregnancy were 36% among first-time IVF recipients and 30% among women undergoing their third round of IVF, and did not differ based on self-reported depressive symptoms, stress, anxiety, or serum levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), cortisol, or interleukin-6, Maria Costantini-Ferrando, MD, PhD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine.