User login

Letter to the Editor: Therapeutic hypothermia for newborns

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

“PROTECTING THE NEWBORN BRAIN—THE FINAL FRONTIER IN OBSTETRIC AND NEONATAL CARE”

ROBERT L. BARBIERI, MD (AUGUST 2016)

Therapeutic hypothermia

I practice in a small community hospital without a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). We have always paid attention to warming neonates. Although we cannot start neonatal therapeutic hypothermia, as Dr. Barbieri discusses in his August Editorial, would there be any benefit to avoiding purposefully warming infants who are depressed at birth? NICU care requires a pediatric transport team, which takes at least an hour to arrive.

Jane Dawson, MD

Maryville, Missouri

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Dawson for her observations and query. I agree that at a hospital without a NICU, pending the arrival of a pediatric transport team, clinicians should strive to prevent hyperthermia in a newborn with encephalopathy because hyperthermia might exacerbate the ischemic injury. It may make sense to avoid aggressive warming of the newborn to permit the core temperature to decrease in order to begin the hypothermia process.

Letters to the Editor: Managing impacted fetal head at cesarean

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

“STOP USING INSTRUMENTS TO ASSIST WITH DELIVERY OF THE HEAD AT CESAREAN; START DISENGAGING THE HEAD PRIOR TO SURGERY”

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD, MBA (AUGUST 2016)

Patient positioning helps in managing impacted fetal head

As a general practice ObGyn, I have seen an increasing incidence of difficult cesareans as a result of prolonged second stage of labor. Dr. Norwitz cites this increase in his article. I have found that trying to elevate the fetal head prior to the start of surgery has been remarkably ineffective. In my practice, I place all my patients with second-stage arrest in low lithotomy stirrups (“blue fins”); this allows the nurses easier access to the vagina to elevate the head at surgery while I am reaching down from above. Usually, this facilitates delivery. It also allows better assessment of blood loss through the vagina as the cesarean progresses, and it makes placement of a Bakri balloon easier if necessary. If stirrups are not available, the patient can be placed in frog leg positioning so that my assistant can reach down and elevate the head if necessary. I find that in a patient with a very small pelvis, it is hard to get my hand down to the baby’s head. I have not yet done a breech extraction, but I know it is possible. I would probably try nitroglycerin first.

I think that difficult cesarean delivery is much more common than difficult shoulder dystocia, and we should develop standard procedures for addressing the issue and use simulation models to practice. In my time-out prior to surgery, I discuss my concerns so that everyone is ready for it, including the anesthesiologist/CRNA, and we have nitroglycerin available to relax the uterus if necessary. I hope that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) will develop a committee opinion about this very important issue.

Marguerite P. Cohen, MD

Portland, Oregon

Assistant is key in disengaging fetal head

Disengaging the head by an assistant during a cesarean delivery is probably the most successful and useful method for managing an impacted fetal head at cesarean. The disengagement of the head prior to cesarean is practiced routinely in Europe, where forceps delivery is frequently performed. However, the disengagement should be done in the operating room (OR) just prior to or during the cesarean. To perform this in the delivery room, as suggested in Dr. Norwitz’s article, risks the associated fetal bradycardia due to head compression that might compromise an already compromised fetus. In addition, there is a risk of cord prolapse or release of excessive amniotic fluid resulting in cord compression. Also, in many hospitals in the United States, there is some delay to perform the cesarean because the OR is on a different floor from the labor and delivery room and the OR staff come from home.

Vacuum extraction can be safely used for the extraction of the head if it is not possible to deliver it manually. However, the head should be manually disimpacted and rotated to occiput anterior prior to application of the vacuum. But the presence of caput might pose some difficulty with proper application and traction.

It is important to remember that the risk factors for an impacted fetal head are also risk factors for postoperative infection. Therefore, vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution should be considered prior to cesarean delivery for all patients in labor.1

Raymond Michael, MD

Marshall, Minnesota

Reference

- Haas DM, Morgan Al Darei S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD007892.

Product Update: SureSound+ device; LILETTA single-handed inserter

PRECISE PREABLATION MEASUREMENT

The SureSound + device is designed to allow a physician to measure cavity length with one click, unlike traditional sounding methods that require multiple calculations, says Hologic. Hologic indicates that the device is inserted through the cervical canal, the Malecot anchor is deployed on the internal os, and the inner probe’s polyethylene tip is extended to the fundus to gauge uterine cavity length. The single-use device also may reduce the risk of contamination, says Hologic.

The manufacturer indicates the NovaSure procedure is appropriate for treating premenopausal women with heavy periods due to benign causes who have finished childbearing.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.novasure.com/hcp/suresound_plus

NEW LILETTA INSERTER

The companies indicate that the LILETTA IUD is for use by women wishing to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years regardless of parity or body mass index, with a cumulative 3-year efficacy rate of 99.45%. Approval of the new LILETTA single-handed inserter was based on the ACCESS IUS study that enrolled 1,751 US women and also led to LILETTA’s approval. Product marketing materials state that, during the ACCESS IUS study, the success rate for insertions with the new inserter was 99.2%. The original inserter requires a 2-handed technique.

According to Allergan and Medicines360, the new inserter includes: an ergonomic design allowing for single-handed insertion that can be used with either hand, a bendable tube to accommodate the anatomy of the patient during insertion, and the ability to reload the device if needed before insertion.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.liletta.com

PRECISE PREABLATION MEASUREMENT

The SureSound + device is designed to allow a physician to measure cavity length with one click, unlike traditional sounding methods that require multiple calculations, says Hologic. Hologic indicates that the device is inserted through the cervical canal, the Malecot anchor is deployed on the internal os, and the inner probe’s polyethylene tip is extended to the fundus to gauge uterine cavity length. The single-use device also may reduce the risk of contamination, says Hologic.

The manufacturer indicates the NovaSure procedure is appropriate for treating premenopausal women with heavy periods due to benign causes who have finished childbearing.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.novasure.com/hcp/suresound_plus

NEW LILETTA INSERTER

The companies indicate that the LILETTA IUD is for use by women wishing to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years regardless of parity or body mass index, with a cumulative 3-year efficacy rate of 99.45%. Approval of the new LILETTA single-handed inserter was based on the ACCESS IUS study that enrolled 1,751 US women and also led to LILETTA’s approval. Product marketing materials state that, during the ACCESS IUS study, the success rate for insertions with the new inserter was 99.2%. The original inserter requires a 2-handed technique.

According to Allergan and Medicines360, the new inserter includes: an ergonomic design allowing for single-handed insertion that can be used with either hand, a bendable tube to accommodate the anatomy of the patient during insertion, and the ability to reload the device if needed before insertion.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.liletta.com

PRECISE PREABLATION MEASUREMENT

The SureSound + device is designed to allow a physician to measure cavity length with one click, unlike traditional sounding methods that require multiple calculations, says Hologic. Hologic indicates that the device is inserted through the cervical canal, the Malecot anchor is deployed on the internal os, and the inner probe’s polyethylene tip is extended to the fundus to gauge uterine cavity length. The single-use device also may reduce the risk of contamination, says Hologic.

The manufacturer indicates the NovaSure procedure is appropriate for treating premenopausal women with heavy periods due to benign causes who have finished childbearing.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: http://www.novasure.com/hcp/suresound_plus

NEW LILETTA INSERTER

The companies indicate that the LILETTA IUD is for use by women wishing to prevent pregnancy for up to 3 years regardless of parity or body mass index, with a cumulative 3-year efficacy rate of 99.45%. Approval of the new LILETTA single-handed inserter was based on the ACCESS IUS study that enrolled 1,751 US women and also led to LILETTA’s approval. Product marketing materials state that, during the ACCESS IUS study, the success rate for insertions with the new inserter was 99.2%. The original inserter requires a 2-handed technique.

According to Allergan and Medicines360, the new inserter includes: an ergonomic design allowing for single-handed insertion that can be used with either hand, a bendable tube to accommodate the anatomy of the patient during insertion, and the ability to reload the device if needed before insertion.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT: https://www.liletta.com

FDA approves first automated insulin delivery system

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first automated insulin delivery device for patients aged 14 years and older with type 1 diabetes.

The MiniMed 670G by Medtronic – an “artificial pancreas” – is a hybrid closed-loop system designed to automatically monitor glucose and deliver appropriate basal insulin doses. The system was shown in a study of 123 individuals with type 1 diabetes to be safe for those aged 14 and older; no serious adverse events, diabetic ketoacidosis, or severe hypoglycemia occurred during a 3-month period when the system was used as frequently as possible by study subjects.

“This first-of-its-kind technology can provide people with type 1 diabetes greater freedom to live their lives without having to consistently and manually monitor baseline glucose levels and administer insulin,” Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press statement.

As part of its approval of the device, the FDA is requiring a postmarket study of its performance in real-world settings, and although the approved version of the device is unsafe for use in children aged 6 years and younger and in those who require fewer than eight units of insulin daily, Medtronic is currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of the device in children aged 7-13 years.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first automated insulin delivery device for patients aged 14 years and older with type 1 diabetes.

The MiniMed 670G by Medtronic – an “artificial pancreas” – is a hybrid closed-loop system designed to automatically monitor glucose and deliver appropriate basal insulin doses. The system was shown in a study of 123 individuals with type 1 diabetes to be safe for those aged 14 and older; no serious adverse events, diabetic ketoacidosis, or severe hypoglycemia occurred during a 3-month period when the system was used as frequently as possible by study subjects.

“This first-of-its-kind technology can provide people with type 1 diabetes greater freedom to live their lives without having to consistently and manually monitor baseline glucose levels and administer insulin,” Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press statement.

As part of its approval of the device, the FDA is requiring a postmarket study of its performance in real-world settings, and although the approved version of the device is unsafe for use in children aged 6 years and younger and in those who require fewer than eight units of insulin daily, Medtronic is currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of the device in children aged 7-13 years.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first automated insulin delivery device for patients aged 14 years and older with type 1 diabetes.

The MiniMed 670G by Medtronic – an “artificial pancreas” – is a hybrid closed-loop system designed to automatically monitor glucose and deliver appropriate basal insulin doses. The system was shown in a study of 123 individuals with type 1 diabetes to be safe for those aged 14 and older; no serious adverse events, diabetic ketoacidosis, or severe hypoglycemia occurred during a 3-month period when the system was used as frequently as possible by study subjects.

“This first-of-its-kind technology can provide people with type 1 diabetes greater freedom to live their lives without having to consistently and manually monitor baseline glucose levels and administer insulin,” Jeffrey Shuren, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press statement.

As part of its approval of the device, the FDA is requiring a postmarket study of its performance in real-world settings, and although the approved version of the device is unsafe for use in children aged 6 years and younger and in those who require fewer than eight units of insulin daily, Medtronic is currently evaluating the safety and efficacy of the device in children aged 7-13 years.

Long-term breast cancer studies yield encouraging data for recurrence, survival

Four pivotal breast cancer trials were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. The MA.17R trial, which was the plenary talk by Dr Paul Goss, looked at extending adjuvant aromatase inhibitors to 10 years or beyond in postmenopausal women; two presentations reported on mutations after progression in metastatic breast cancer, one on first-line AIs and the other on prior endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3); and results from the Z0011 trial showed that sentinel lymph node dissection without axillary lymph node dissection might show promising 10-year loco-regional control and survival outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Four pivotal breast cancer trials were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. The MA.17R trial, which was the plenary talk by Dr Paul Goss, looked at extending adjuvant aromatase inhibitors to 10 years or beyond in postmenopausal women; two presentations reported on mutations after progression in metastatic breast cancer, one on first-line AIs and the other on prior endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3); and results from the Z0011 trial showed that sentinel lymph node dissection without axillary lymph node dissection might show promising 10-year loco-regional control and survival outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Four pivotal breast cancer trials were presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology in Chicago. The MA.17R trial, which was the plenary talk by Dr Paul Goss, looked at extending adjuvant aromatase inhibitors to 10 years or beyond in postmenopausal women; two presentations reported on mutations after progression in metastatic breast cancer, one on first-line AIs and the other on prior endocrine therapy (PALOMA-3); and results from the Z0011 trial showed that sentinel lymph node dissection without axillary lymph node dissection might show promising 10-year loco-regional control and survival outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Anticipate, treat GI issues in scleroderma

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to GI symptoms in your scleroderma patients. Gut involvement in scleroderma, a result of vasculopathy and fibrosis affecting the GI tract, is common and can be debilitating, said Daniel Furst, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatologic Diseases presented by the Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Furst said that the progression often begins at the mouth and esophagus, and progresses through the digestive system, eventually reaching the rectum and anus.

“You think about motility issues early on, in the esophagus,” and early oral symptoms can include mouth dryness, said Dr. Furst, who is associated with the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Washington, Seattle, and the University of Florence (Italy).

As scleroderma begins to affect the midgut, Dr. Furst said that the secondary results of the decrease in motility are symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety.

“When you have a decrease in motility, then the normal ... housekeeping waves of the midgut and the colon are decreased,” he said. Bacteria from the colon can then invade the small bowel, causing overgrowth of the midgut by species not normally seen there. Not only gas, but also malnutrition can eventually result, he said.

When scleroderma affects the lower gut, patients can have bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, and finally, incontinence of the bowel, a condition with often devastating psychosocial consequences.

The choice of promotility agents depends on the area affected; erythromycin and metoclopramide help in the upper GI tract, while tegaserod can be helpful in the lower gut.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to GI symptoms in your scleroderma patients. Gut involvement in scleroderma, a result of vasculopathy and fibrosis affecting the GI tract, is common and can be debilitating, said Daniel Furst, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatologic Diseases presented by the Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Furst said that the progression often begins at the mouth and esophagus, and progresses through the digestive system, eventually reaching the rectum and anus.

“You think about motility issues early on, in the esophagus,” and early oral symptoms can include mouth dryness, said Dr. Furst, who is associated with the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Washington, Seattle, and the University of Florence (Italy).

As scleroderma begins to affect the midgut, Dr. Furst said that the secondary results of the decrease in motility are symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety.

“When you have a decrease in motility, then the normal ... housekeeping waves of the midgut and the colon are decreased,” he said. Bacteria from the colon can then invade the small bowel, causing overgrowth of the midgut by species not normally seen there. Not only gas, but also malnutrition can eventually result, he said.

When scleroderma affects the lower gut, patients can have bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, and finally, incontinence of the bowel, a condition with often devastating psychosocial consequences.

The choice of promotility agents depends on the area affected; erythromycin and metoclopramide help in the upper GI tract, while tegaserod can be helpful in the lower gut.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LAS VEGAS – Pay attention to GI symptoms in your scleroderma patients. Gut involvement in scleroderma, a result of vasculopathy and fibrosis affecting the GI tract, is common and can be debilitating, said Daniel Furst, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatologic Diseases presented by the Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Furst said that the progression often begins at the mouth and esophagus, and progresses through the digestive system, eventually reaching the rectum and anus.

“You think about motility issues early on, in the esophagus,” and early oral symptoms can include mouth dryness, said Dr. Furst, who is associated with the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Washington, Seattle, and the University of Florence (Italy).

As scleroderma begins to affect the midgut, Dr. Furst said that the secondary results of the decrease in motility are symptoms such as heartburn, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety.

“When you have a decrease in motility, then the normal ... housekeeping waves of the midgut and the colon are decreased,” he said. Bacteria from the colon can then invade the small bowel, causing overgrowth of the midgut by species not normally seen there. Not only gas, but also malnutrition can eventually result, he said.

When scleroderma affects the lower gut, patients can have bloating, diarrhea, and constipation, and finally, incontinence of the bowel, a condition with often devastating psychosocial consequences.

The choice of promotility agents depends on the area affected; erythromycin and metoclopramide help in the upper GI tract, while tegaserod can be helpful in the lower gut.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

On Twitter @karioakes

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL PERSPECTIVES IN RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Cannabis use after first-episode psychosis may raise relapse risk

Does habitual cannabis use trigger psychosis, or does a tendency toward psychosis predict increased cannabis use?

“[Our] results suggest that it is more likely than not that continued cannabis use after onset of psychosis is causally associated with increased risk of relapse of psychosis, resulting in psychiatric hospitalization,” reported the authors of a study published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Psychiatry.

It is well established that cannabis use after first-episode psychosis is associated with poor outcomes; what is not so well established is why. The three most prominent theories so far are that cannabis use and psychosis share inherent genetic and/or environmental vulnerabilities, impending psychosis impels increased cannabis use, and conversely, cannabis use has a causal effect on psychosis (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016:3[5]:401) and (Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;3[5]401-2).

After conducting a 10-year, prospective cohort investigation of 220 people who presented to psychiatric services at numerous sites in London between April 2002 and July 2013, Tabea Schoeler and her associates in the current study found that the odds of a relapse of psychosis during periods of cannabis use was increased by 1.13, compared with periods of no cannabis use (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.24) (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2427). Further, those who used cannabis continually after first-episode psychosis were found to have a 59.1% higher risk of relapsing psychosis in that 10-year period, compared with a 28.5% increased risk in those who quit using cannabis entirely (P less than .001).

The only true way to measure causality in this area would be to administer cannabis to participants in a randomized, clinically controlled trial, thus challenging the ethics of clinical study. Instead, Ms. Schoeler of the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London and her associates – including Sir Robin M. Murray, MD, a psychiatrist who has been a leading voice in favor of the view that cannabis use and psychotic episodes are often linked – used patient self-reports to assess changes in cannabis use over time. This allowed the investigators to more clearly differentiate between confounders that cannot be readily observed, and that are not likely to change over time, such as any shared genetic or environmental factors, and confounders that can be observed and that do have the potential to change, such as the change in cannabis use status over time, including nonuser vs. user status, and the pattern and frequency of use after onset of illness.

The data were collected in two separate assessments, one was conducted near the time of illness onset, and again at least 2 years after the first episode of psychosis. If interviews were not possible to complete in person, they were conducted over the phone. These data were combined with patient clinical records across the study period. Frequency of cannabis use was measured based on the Cannabis Experience Questionnaire. A patient was considered to have relapsed if he or she was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility for exacerbated symptoms of psychosis within 2 years of the first episode of psychosis.

As for the study population, 59.1% of whom were men with an average age of 29 years, there were no significant differences as to whether they had been diagnosed with either affective or nonaffective psychosis. However, there were significant differences between the risk of relapse and the frequency of cannabis use 2 years after onset of illness. In the nonuser group, 28.5% of patients relapsed. In the intermittent user group, 36% relapsed. In the continuous use group, 59.1% relapsed (P less than .001).

Differences also were found across the three groups in medication adherence rates. Among the nonusers, 47.7% reportedly complied with treatment. The rate was 32% among intermittent users and 20.5% among habitual users (P = .02). Illicit use of other drugs was also higher in the continuous cannabis use group: 27.3% vs. 4% in the cannabis nonuse group and 12% in the intermittent use group (P less than .001).

Also noteworthy was the age of psychosis onset across the groups. While the average age of onset across the study was 28.62 years, for habitual users the average age of illness onset was 25.44 years, compared with 29.52 in nonusers and 28.79 in intermittent users (P = .02).

These results should be viewed in light of their retrospective and self-reported nature – neither of which take into account either premorbid cannabis use or age of illness onset as either predictors or moderators – but the data suggest a dose-response relationship between cannabis use and psychosis, according to the investigators. If so, the implications of the data could reach beyond patient outcomes.

“Because cannabis use is a potentially modifiable risk factor that has an adverse influence on the risk of relapse of psychosis and hospitalization in a given individual, with limited efficacy of existing interventions, these results underscore the importance of developing novel intervention strategies and demand urgent attention from clinicians and health care policy makers,” the authors wrote.

Whether the study conclusively demonstrates that it is cannabis use – and not genetic liability or reverse causation – that drives relapse of psychosis is still not clear. By the investigators’ own admission, the effect of discontinuing cannabis use on patient outcomes has not been tested, leaving the question of a definite causal relationship between continual cannabis use and relapse of psychosis still open for debate.

Ms. Schoeler and the other investigators – with the exception of Dr. Murray – reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Murray reported that he has received honoraria from Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. The study was funded in large part by the U.K.’s National Institute for Health Research and by King’s College London.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Does habitual cannabis use trigger psychosis, or does a tendency toward psychosis predict increased cannabis use?

“[Our] results suggest that it is more likely than not that continued cannabis use after onset of psychosis is causally associated with increased risk of relapse of psychosis, resulting in psychiatric hospitalization,” reported the authors of a study published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Psychiatry.

It is well established that cannabis use after first-episode psychosis is associated with poor outcomes; what is not so well established is why. The three most prominent theories so far are that cannabis use and psychosis share inherent genetic and/or environmental vulnerabilities, impending psychosis impels increased cannabis use, and conversely, cannabis use has a causal effect on psychosis (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016:3[5]:401) and (Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;3[5]401-2).

After conducting a 10-year, prospective cohort investigation of 220 people who presented to psychiatric services at numerous sites in London between April 2002 and July 2013, Tabea Schoeler and her associates in the current study found that the odds of a relapse of psychosis during periods of cannabis use was increased by 1.13, compared with periods of no cannabis use (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.24) (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2427). Further, those who used cannabis continually after first-episode psychosis were found to have a 59.1% higher risk of relapsing psychosis in that 10-year period, compared with a 28.5% increased risk in those who quit using cannabis entirely (P less than .001).

The only true way to measure causality in this area would be to administer cannabis to participants in a randomized, clinically controlled trial, thus challenging the ethics of clinical study. Instead, Ms. Schoeler of the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London and her associates – including Sir Robin M. Murray, MD, a psychiatrist who has been a leading voice in favor of the view that cannabis use and psychotic episodes are often linked – used patient self-reports to assess changes in cannabis use over time. This allowed the investigators to more clearly differentiate between confounders that cannot be readily observed, and that are not likely to change over time, such as any shared genetic or environmental factors, and confounders that can be observed and that do have the potential to change, such as the change in cannabis use status over time, including nonuser vs. user status, and the pattern and frequency of use after onset of illness.

The data were collected in two separate assessments, one was conducted near the time of illness onset, and again at least 2 years after the first episode of psychosis. If interviews were not possible to complete in person, they were conducted over the phone. These data were combined with patient clinical records across the study period. Frequency of cannabis use was measured based on the Cannabis Experience Questionnaire. A patient was considered to have relapsed if he or she was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility for exacerbated symptoms of psychosis within 2 years of the first episode of psychosis.

As for the study population, 59.1% of whom were men with an average age of 29 years, there were no significant differences as to whether they had been diagnosed with either affective or nonaffective psychosis. However, there were significant differences between the risk of relapse and the frequency of cannabis use 2 years after onset of illness. In the nonuser group, 28.5% of patients relapsed. In the intermittent user group, 36% relapsed. In the continuous use group, 59.1% relapsed (P less than .001).

Differences also were found across the three groups in medication adherence rates. Among the nonusers, 47.7% reportedly complied with treatment. The rate was 32% among intermittent users and 20.5% among habitual users (P = .02). Illicit use of other drugs was also higher in the continuous cannabis use group: 27.3% vs. 4% in the cannabis nonuse group and 12% in the intermittent use group (P less than .001).

Also noteworthy was the age of psychosis onset across the groups. While the average age of onset across the study was 28.62 years, for habitual users the average age of illness onset was 25.44 years, compared with 29.52 in nonusers and 28.79 in intermittent users (P = .02).

These results should be viewed in light of their retrospective and self-reported nature – neither of which take into account either premorbid cannabis use or age of illness onset as either predictors or moderators – but the data suggest a dose-response relationship between cannabis use and psychosis, according to the investigators. If so, the implications of the data could reach beyond patient outcomes.

“Because cannabis use is a potentially modifiable risk factor that has an adverse influence on the risk of relapse of psychosis and hospitalization in a given individual, with limited efficacy of existing interventions, these results underscore the importance of developing novel intervention strategies and demand urgent attention from clinicians and health care policy makers,” the authors wrote.

Whether the study conclusively demonstrates that it is cannabis use – and not genetic liability or reverse causation – that drives relapse of psychosis is still not clear. By the investigators’ own admission, the effect of discontinuing cannabis use on patient outcomes has not been tested, leaving the question of a definite causal relationship between continual cannabis use and relapse of psychosis still open for debate.

Ms. Schoeler and the other investigators – with the exception of Dr. Murray – reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Murray reported that he has received honoraria from Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. The study was funded in large part by the U.K.’s National Institute for Health Research and by King’s College London.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Does habitual cannabis use trigger psychosis, or does a tendency toward psychosis predict increased cannabis use?

“[Our] results suggest that it is more likely than not that continued cannabis use after onset of psychosis is causally associated with increased risk of relapse of psychosis, resulting in psychiatric hospitalization,” reported the authors of a study published online Sept. 28 in JAMA Psychiatry.

It is well established that cannabis use after first-episode psychosis is associated with poor outcomes; what is not so well established is why. The three most prominent theories so far are that cannabis use and psychosis share inherent genetic and/or environmental vulnerabilities, impending psychosis impels increased cannabis use, and conversely, cannabis use has a causal effect on psychosis (Lancet Psychiatry. 2016:3[5]:401) and (Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;3[5]401-2).

After conducting a 10-year, prospective cohort investigation of 220 people who presented to psychiatric services at numerous sites in London between April 2002 and July 2013, Tabea Schoeler and her associates in the current study found that the odds of a relapse of psychosis during periods of cannabis use was increased by 1.13, compared with periods of no cannabis use (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.24) (JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Sep 28. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2427). Further, those who used cannabis continually after first-episode psychosis were found to have a 59.1% higher risk of relapsing psychosis in that 10-year period, compared with a 28.5% increased risk in those who quit using cannabis entirely (P less than .001).

The only true way to measure causality in this area would be to administer cannabis to participants in a randomized, clinically controlled trial, thus challenging the ethics of clinical study. Instead, Ms. Schoeler of the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neuroscience at King’s College London and her associates – including Sir Robin M. Murray, MD, a psychiatrist who has been a leading voice in favor of the view that cannabis use and psychotic episodes are often linked – used patient self-reports to assess changes in cannabis use over time. This allowed the investigators to more clearly differentiate between confounders that cannot be readily observed, and that are not likely to change over time, such as any shared genetic or environmental factors, and confounders that can be observed and that do have the potential to change, such as the change in cannabis use status over time, including nonuser vs. user status, and the pattern and frequency of use after onset of illness.

The data were collected in two separate assessments, one was conducted near the time of illness onset, and again at least 2 years after the first episode of psychosis. If interviews were not possible to complete in person, they were conducted over the phone. These data were combined with patient clinical records across the study period. Frequency of cannabis use was measured based on the Cannabis Experience Questionnaire. A patient was considered to have relapsed if he or she was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility for exacerbated symptoms of psychosis within 2 years of the first episode of psychosis.

As for the study population, 59.1% of whom were men with an average age of 29 years, there were no significant differences as to whether they had been diagnosed with either affective or nonaffective psychosis. However, there were significant differences between the risk of relapse and the frequency of cannabis use 2 years after onset of illness. In the nonuser group, 28.5% of patients relapsed. In the intermittent user group, 36% relapsed. In the continuous use group, 59.1% relapsed (P less than .001).

Differences also were found across the three groups in medication adherence rates. Among the nonusers, 47.7% reportedly complied with treatment. The rate was 32% among intermittent users and 20.5% among habitual users (P = .02). Illicit use of other drugs was also higher in the continuous cannabis use group: 27.3% vs. 4% in the cannabis nonuse group and 12% in the intermittent use group (P less than .001).

Also noteworthy was the age of psychosis onset across the groups. While the average age of onset across the study was 28.62 years, for habitual users the average age of illness onset was 25.44 years, compared with 29.52 in nonusers and 28.79 in intermittent users (P = .02).

These results should be viewed in light of their retrospective and self-reported nature – neither of which take into account either premorbid cannabis use or age of illness onset as either predictors or moderators – but the data suggest a dose-response relationship between cannabis use and psychosis, according to the investigators. If so, the implications of the data could reach beyond patient outcomes.

“Because cannabis use is a potentially modifiable risk factor that has an adverse influence on the risk of relapse of psychosis and hospitalization in a given individual, with limited efficacy of existing interventions, these results underscore the importance of developing novel intervention strategies and demand urgent attention from clinicians and health care policy makers,” the authors wrote.

Whether the study conclusively demonstrates that it is cannabis use – and not genetic liability or reverse causation – that drives relapse of psychosis is still not clear. By the investigators’ own admission, the effect of discontinuing cannabis use on patient outcomes has not been tested, leaving the question of a definite causal relationship between continual cannabis use and relapse of psychosis still open for debate.

Ms. Schoeler and the other investigators – with the exception of Dr. Murray – reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Murray reported that he has received honoraria from Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. The study was funded in large part by the U.K.’s National Institute for Health Research and by King’s College London.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: Frequent cannabis use in people with psychosis could lead to hospitalization for psychosis relapse.

Major finding: Continuing to use cannabis after first-episode psychosis was associated with 1.13 greater odds of psychosis relapse, compared with psychosis relapse rates during periods of no cannabis use (95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.24).

Data source: A prospective U.K. cohort study of 220 people who presented to psychiatric services with first-episode psychosis between 2002 and 2013.

Disclosures: Ms. Schoeler and the other investigators – with the exception of Dr. Murray – reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Murray reported that he has received honoraria from Janssen, Sunovion, Otsuka, and Lundbeck. The study was funded in large part by the U.K.’s National Institute for Health Research and by King’s College London.

Forget the myths and help your psychiatric patients quit smoking

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey1,2 (NAMCS) indicates that less than 1 out of 4 (23%) psychiatrists provide smoking cessation counseling to their patients, and even fewer prescribe medications.

What gives? How is it that so many psychiatrists endorse having recently helped a patient quit smoking when the data from large-scale surveys1,2 indicate they do not?

From the “glass is half-full” perspective, the discrepancy might indicate that psychiatrists finally have bought into the message put forth 20 years ago when the American Psychiatric Association first published its clinical practice guidelines for treating nicotine dependence.3 Because the figures I cited from NAMCS reflect data from 2006 to 2010, it is possible that in the last 5 years more psychiatrists have started to help their patients quit smoking. Such an hypothesis is further supported by the increasing number of research papers on smoking cessation in individuals with mental illness published over the past 8 years—a period that coincides with the release of the second edition of the Treating tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which highlighted the need for more research in this population of smokers.4

Regardless of the reason, the fact that my informal surveys indicate a likely uptick in activity among psychiatrists to help their patients quit smoking is welcome news. With nearly 1 out of 2 cigarettes sold in the United States being smoked by individuals with psychiatric and substance use disorders,5 psychiatrists and other mental health professionals play a vital role in addressing this epidemic. That our patients smoke at rates 2- to 4-times that of the general population and die decades earlier than their non-smoking, non-mentally ill counterparts6 are compelling reasons urging us to end our complacency and help our patients quit smoking.

EAGLES trial results help debunk the latest myth about smoking cessation

In an article that I wrote for

In addition to applying the “black-box” warning, the FDA issued a post-marketing requirement to the manufacturers of bupropion and varenicline to conduct a large randomized controlled trial—Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES)—the top-line results of which were published in The Lancet this spring.12

Key results of the EAGLES trial

The researchers found no significant increase in serious neuropsychiatric AEs—a composite measure assessing depression, anxiety, suicidality, and 13 other symptom clusters—attributable to varenicline or bupropion compared with placebo or the nicotine patch in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders. The study did detect a significant difference—approximately 4% (2% in non-psychiatric cohort vs 6% in psychiatric cohort)—in the rate of serious neuropsychiatric AEs regardless of treatment condition. In both cohorts, varenicline was more effective than bupropion, which had similar efficacy to the nicotine patch; all interventions were superior to placebo. Importantly, all 3 medications significantly improved quit rates in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders. Although the efficacy of medications in smokers with or without psychiatric disorders was similar in terms of odds ratios, overall, those with psychiatric disorders had 20% to 30% lower quit rates compared with non-psychiatrically ill smokers.

The EAGLES study results, when viewed in the context of findings from other clinical trials and large-scale observational studies, provide further evidence that smokers with stable mental illness can use bupropion and varenicline safely. It also demonstrates that moderate to severe neuropsychiatric AEs occur during a smoking cessation attempt regardless of the medication used, therefore, monitoring smokers—especially those with psychiatric disorders—is important, a role that psychiatrists are uniquely poised to play.

That all 3 smoking cessation medications are effective in patients with mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders is good news for our patients. Combined with the EAGLES safety findings, there is no better time to intervene in tobacco dependence

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

1. Rogers E, Sherman S. Tobacco use screening and treatment by outpatient psychiatrists before and after release of the American Psychiatric Association treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):90-95.

2. Himelhoch S, Daumit G. To whom do psychiatrists offer smoking-cessation counseling? Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(12):2228-2230.

3. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with nicotine dependence. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;53;153(suppl 10):1-31.

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Clinical practice guideline. http://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Published May 2008. Accessed September 12, 2016.

5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, et al. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107-1115.

6. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

7. Anthenelli RM. How—and why—to help psychiatric patients stop smoking. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):77-87.

8. Zyban [package insert]. Research Triangle Park, NC; GlaxoSmithKline; 2016.

9. Chantix [package insert]. New York, NY: Pfizer; 2016.

10. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking – 50 years of progress: a report of the surgeon general, 2014. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014.

11. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011: warning about the dangers of tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2011/en/index.html. Published 2011. Accessed December 1, 2015.

12. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;18;387(10037):2507-2520.

13. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002.

15. First M, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, et al. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1997.

16. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361-370.

17. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;168(12):1266-1277.

HPV vaccine and adolescents: What we say really does matter

It has been almost 10 years since the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended administration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for 11- to 12-year-old girls and young women up to 26 years of age. Routine administration in preteen boys and young adult males up to 21 years of age was recommended in 2011. An HPV series should be completed by 13 years. So how well are we protecting our patients?

Vaccine coverage

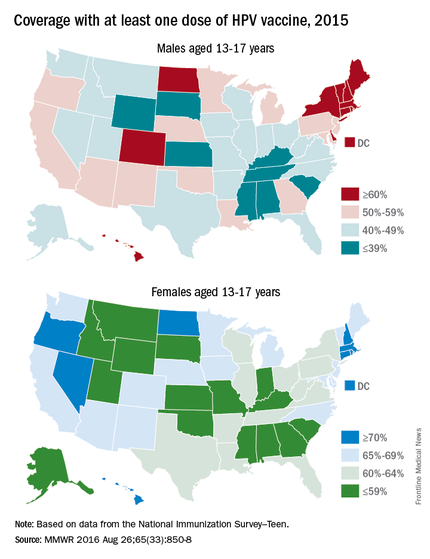

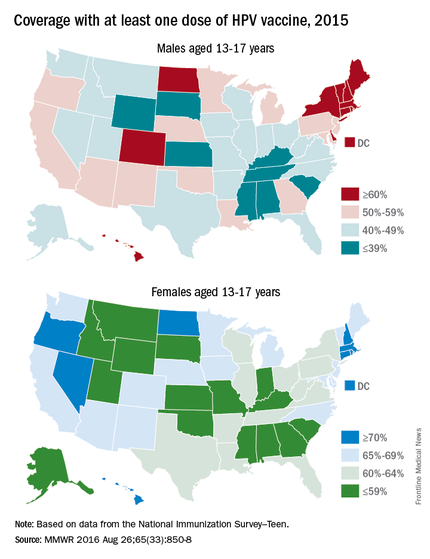

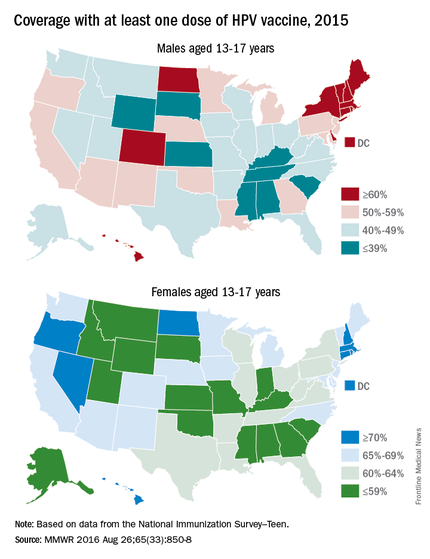

The National Immunization Survey–Teen (NIS-Teen) monitors vaccine coverage annually among adolescents 13-17 years. Data are obtained from individuals from the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and six major urban areas (MMWR. 2016 Aug 26;65[33]:850-8).

HPV vaccination continues to lag behind Tdap and the meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MCV), although each one is recommended to be administered at the 11- to 12-year visit. In 2015, coverage for receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine among females was almost 62.8 % and for at least three doses was 41.9%; among males, coverage with at least one dose was 49.8% and for at least three doses was 28.1%. Compared with 2014, coverage for at least one dose of HPV vaccine increased 2.8% in females and 8.1% in males. Males also had a 7.6% for receipt of at least two doses of HPV vaccine, compared with 2014. HPV vaccine coverage in females aged 13 and younger also was lower than for those aged 15 and older. Coverage did not differ for males based on age.

HPV vaccination coverage also differed by state. In 2015, 28 states reported increased coverage in males, but only 7 states had increased coverage in females. Among all adolescents, coverage with at least one dose of HPV vaccine was 56.1%, at least two doses was 45.4%, and at least three doses was 34.9%. In contrast, 86.4% of all adolescents received at least one dose of Tdap, and 81.3% received at least one dose of MCV.

HPV-associated cancers

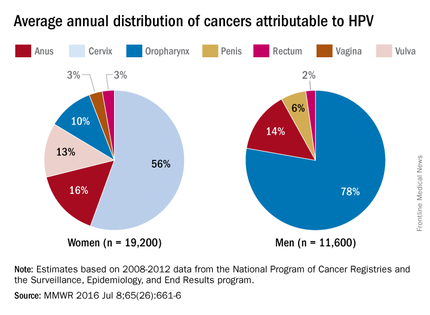

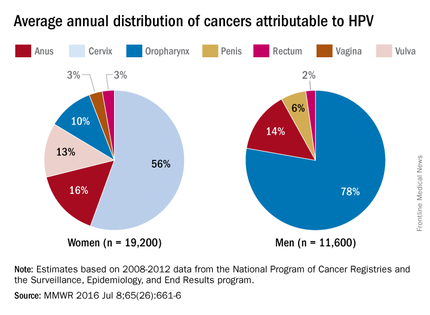

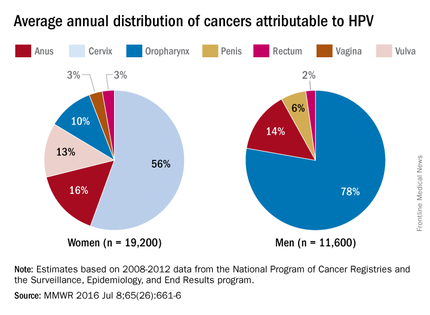

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in both men and women. It is estimated that 79 million Americans are infected and 14 million new infections occur annually, usually in teens and young adults. Although most infections are asymptomatic and clear spontaneously, persistent infection with oncogenic types can progress to cancer. Cervical and oropharyngeal cancer were the most common HPV-associated cancers in women and men, respectively, in 2008-2012 (MMWR 2016;65:661-6).

All three HPV vaccines protect against HPV types 16 and 18. These types are estimated to account for the majority of cervical and oropharyngeal cancers, 66% and 62%, respectively. The additional types in the 9-valent HPV will protect against HPV types that cause approximately 15% of cervical cancers.

The association between HPV and cancer is clear. So why isn’t this vaccine being embraced? HPV vaccine is all about cancer prevention. Isn’t it? What are the barriers to HPV vaccination? Are parental concerns the only barrier? Are we recommending this vaccine as strongly as others?

Vaccine safety and efficacy

Safety has been a concern voiced by some parents. Collectively, HPV vaccines were studied in more than 95,000 individuals prior to licensure. Almost 90 million doses of vaccine have been distributed in the United States and more than 183 million, worldwide. The federal government utilizes three systems to monitor vaccine safety once a vaccine is licensed: The Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), and the Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Network. Ongoing safety studies also are conducted by vaccine manufacturers. Since licensure, no serious safety concerns have been identified. Postvaccination syncope, first identified in the VAERS database in 2006, has declined since observation post injection was recommended by ACIP. Multiple studies in the United States and abroad have not demonstrated a causal association with HPV vaccine and any autoimmune and/or neurologic condition or increased risk for thromboembolism.

Mélanie Drolet, PhD, and her colleagues reviewed 20 studies in nine countries with at least 50% coverage in female adolescents aged 13-19 years. There was a 68% reduction in the prevalence of HPV types 16 and 18 and a 61% reduction in anal warts in the postvaccine era (Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 May;15[5]:565-80). Studies also indicate there is no indication of waning immunity.

Parental perceptions

Some parents feel the vaccine is not necessary because their child is not sexually active and/or is not at risk for acquiring a sexually transmitted infection. Others opt to delay initiation. NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) data from 2011 to 2014 revealed that among females aged 14-26 years whose age was known at the time of their first dose of HPV vaccine, 43% had reported having sex before or in the same year that they received their first dose.