User login

The confused binge drinker

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

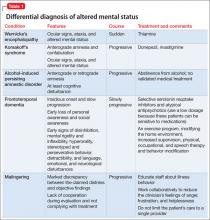

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.

Are the people we serve ‘patients’ or ‘customers’?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice

Neuropsychological evaluation, consisting of a thorough examination of cognitive and behavioral functioning, can make an invaluable contribution to the care of psychiatric patients. Through the vehicle of standardized measures of abilities, patients’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses can be elucidated—revealing potential areas for further interventions or to explain impediments to treatment. A licensed clinical psychologist provides this service.

You, as a consumer of reported findings, can use the results to inform your diagnosis and treatment plan. Recommendations from the neuropsychologist often address dispositional planning, cognitive intervention, psychiatric intervention, and work and school accommodations.

Probing the brain−behavior relationship

Neuropsychology is a subspecialty of clinical psychology that is focused on understanding the brain–behavior relationship. Drawing information from multiple disciplines, including psychiatry and neurology, neuropsychology seeks to uncover the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional difficulties that can result from known or suspected brain dysfunction. Increasingly, to protect the public and referral sources, clinical psychologists who perform neuropsychological testing demonstrate their competence through board certification (eg, the American Board of Clinical Neuropsychology).

How is testing conducted? Evaluations comprise measures that are standardized, scored objectively, and have established psychometric properties. Testing can performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis; the duration of testing depends on the question for which the referring practitioner seeks an answer.

Measures typically are administered by paper and pencil, although computer-based

assessments are increasingly being employed. Because of the influence of demographic variables (age, sex, years of education, race), scores are compared with normative samples that resemble those of the patient’s background as closely as possible.

A thorough clinical interview with the patient, a collateral interview with caregivers

and family, and review of relevant medical records are crucial parts of the assessment. Multiple areas of cognition are assessed:

• intelligence

• academic functioning

• attention

• working memory

• speed of processing

• learning and memory

• visual spatial skills

• fine motor skills

• executive functioning.

Essentially, the evaluation speaks to a patient’s neurocognitive functioning and cerebral integrity.

How are results scored? Interpretation of test scores is contingent on expectations of how a patient should perform in the absence of neurologic or psychiatric illness (ie, based on normative data and performancebased estimates of premorbid functioning).1 The overall pattern of intact scores and deficit scores can be used to form specific impressions about a diagnosis, cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and strategies for intervention.

Personality testing. In addition to the cognitive aspect of the evaluation, personality measures are incorporated when relevant to the referral question or presenting concern.

Personality tests can be broadly divided into objective and projective measures.

Objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory-Second Edition, require the examinee to respond to a set of items as

true or false or on a Likert-type scale from strongly agree to disagree. Responses are then scored in standardized fashion, making comparisons to normative data, which are then analyzed to determine the extent to which the examinee experiences psychiatric symptoms.

As part of testing, patients’ responses to ambiguous or unstructured standard

stimuli—such as a series of drawings, abstract patterns, or incomplete sentences—

are analyzed to determine underlying personality traits, feelings, and attitudes.

Classic examples of these measures include the Rorschach Test and the Thematic

Apperception Test.

Personality measures and psychiatric testing are designed to answer questions

related to patients’ emotional status. These measures assess psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses, whereas neuropsychological measures provide an understanding of patients’ cognitive assets and limitations.

7 Common questions about neuropsychological testing

1 Will my patient’s insurance cover these assessments? The question is common from practitioners who are considering requesting an assessment for a patient. The short answer is “Yes.”

Most payers follow Medicare guidelines for reimbursement of neuropsychological

testing; if testing is determined to be medically necessary, insurance companies often cover the assessment. Medicaid also pays for psychometric testing services. Neuropsychologists who have a hospital-based practice typically include patients

with all types of insurance coverage. For example, 40% of patients seen in a hospital are covered by Medicare or Medicaid.2

A caveat: Local intermediaries interpret policies and procedures in different ways,

so there is variability in coverage by geographic region. That is why it is crucial

for neuropsychologists to obtain preauthorization, as would be the case with other medical procedures and services sought by referral.

Last, insurance companies do not pay for assessment of a learning disability. The

rationale typically offered for this lack of coverage? The assessment is for academic, not medical, purposes. In such a situation, patients and their families are offered a private-pay option.

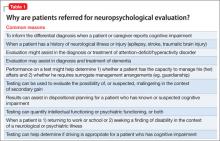

2 What are the indications for neuropsychological assessment? Psychiatric practitioners are one of the top medical specialties that refer their patients for neuropsychological testing.3 This is because many patients with a psychiatric or

neurologic disorder experience changes in cognition, mood, and personality. Such

changes can range in severity from subtle to dramatic, and might reflect an underlying disease state or a side effect of medication or other treatment. Whatever the nature of a patient’s problem, careful assessment might help elucidate specific areas with which he (she) is struggling—so that you can better target your interventions. Table 1 lists common reasons for referring a patient for neuropsychological evaluation. Throughout this discussion, we describe examples of clinical situations in which neuropsychological testing is useful for establishing a differential diagnosis and dispositional planning.