User login

Sunless Tanning: An Alternative to Sun Exposure

iPLEDGE and Its Implementation in Dermatology Practices

Fillers: Past, Present, and Future

BEAM technology shines a light on drug resistance mutations in GIST

CHICAGO – A novel technique for ferreting out DNA mutations in circulating plasma appears to be more sensitive than is conventional pathology at detecting drug-resistant mutations in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, said an investigator at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Secondary KIT mutations associated with resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib (Gleevec) were detected in 47% of plasma samples using "BEAMing" (beads, emulsions, amplification, magnetics) technology, compared with only 12% of tissue biopsy specimens, said Dr. George D. Demetri, director of the center for sarcoma and bone oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

"We know that tumor cells are constantly turning over, apoptosing, dying, and releasing free DNA into the bloodstream. I want to emphasize that this is not looking at circulating tumor cells; this is looking at free circulating DNA in the plasma, and by looking at that circulating DNA, we may be able to get a more comprehensive assessment of all the mutations from across all tumor burden in any given patient," Dr. Demetri said.

The technique, which some investigators have dubbed "liquid biopsy," involves treating plasma with beads coated with DNA sequences that are complementary to target mutational sequences to create an emulsion polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR amplifies the circulating DNA, which can then be identified with flow cytometry. The test can detect one circulating DNA molecule per 10,000 in plasma, according to the American Association for Cancer Research.

Dr. Demetri and his colleagues used the technology to retrospectively study mutations from patient samples in the GRID (GIST-Regorafenib in Progressive Disease) phase III study. In that trial, regorafenib (Stivarga), a multikinase inhibitor, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.27; P less than .0001) in patients with metastatic GIST after failure of both standard and targeted therapies, including imatinib and sunitinib (Sutent).

The investigators looked for primary and secondary mutations in KIT in both plasma samples (available for 163 of 199 patients in GRID) and tumor tissue (from 102 patients), and found that BEAMing detected mutations in 58% of plasma samples, compared with 66% of tumor samples analyzed by the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

In addition, BEAMing detected mutations in PDGFRA in 1% of samples, and in KRAS in one of two samples, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, for sequencing. Neither analysis method detected any BRAF mutations, and the numbers of PDGFRA and KRAS mutations were too small for researchers to draw meaningful conclusions.

When it came to KIT, however, there was a high degree of concordance between the tests where both types of samples from individual patients were available, including 100% agreement for primary KIT exon 9 mutations, 79% for primary KIT exon 11 mutations, and 84% overall for primary KIT exon 9 and 11 mutations.

The BEAMing technology can help determine prognosis of patients with GIST, Dr. Demetri said, noting that in the GRID trial, patients in the placebo arm who had secondary KIT mutations had shorter PFS than did patients without KIT mutations (HR, 1.82; P = .05). Patients with KIT exon 9 mutations had received a shorter course of imatinib than did the rest of the study population (HR, 2.02; P = .002) and a longer course of sunitinib (HR, 0.54; P = .005).

BEAMing analysis also showed that patients with secondary KIT mutations who received regorafenib had significantly better PFS than did patients in the placebo arm (HR, 0.22; P less than .001).

The data Dr. Demetri presented were "very exciting," said invited discussant Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel, professor of sarcoma oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

"The important take-home messages are that there is some very good concordance between the tumor tissue analysis and the plasma analysis," and that regorafenib "appears to be totally agnostic to any of the mutational subsets and seems to equally benefit all patients," Dr. Patel said.

The study was supported in part by Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Demetri disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to the company. Dr. Patel reported having no disclosures relevant to the study.

CHICAGO – A novel technique for ferreting out DNA mutations in circulating plasma appears to be more sensitive than is conventional pathology at detecting drug-resistant mutations in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, said an investigator at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Secondary KIT mutations associated with resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib (Gleevec) were detected in 47% of plasma samples using "BEAMing" (beads, emulsions, amplification, magnetics) technology, compared with only 12% of tissue biopsy specimens, said Dr. George D. Demetri, director of the center for sarcoma and bone oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

"We know that tumor cells are constantly turning over, apoptosing, dying, and releasing free DNA into the bloodstream. I want to emphasize that this is not looking at circulating tumor cells; this is looking at free circulating DNA in the plasma, and by looking at that circulating DNA, we may be able to get a more comprehensive assessment of all the mutations from across all tumor burden in any given patient," Dr. Demetri said.

The technique, which some investigators have dubbed "liquid biopsy," involves treating plasma with beads coated with DNA sequences that are complementary to target mutational sequences to create an emulsion polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR amplifies the circulating DNA, which can then be identified with flow cytometry. The test can detect one circulating DNA molecule per 10,000 in plasma, according to the American Association for Cancer Research.

Dr. Demetri and his colleagues used the technology to retrospectively study mutations from patient samples in the GRID (GIST-Regorafenib in Progressive Disease) phase III study. In that trial, regorafenib (Stivarga), a multikinase inhibitor, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.27; P less than .0001) in patients with metastatic GIST after failure of both standard and targeted therapies, including imatinib and sunitinib (Sutent).

The investigators looked for primary and secondary mutations in KIT in both plasma samples (available for 163 of 199 patients in GRID) and tumor tissue (from 102 patients), and found that BEAMing detected mutations in 58% of plasma samples, compared with 66% of tumor samples analyzed by the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

In addition, BEAMing detected mutations in PDGFRA in 1% of samples, and in KRAS in one of two samples, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, for sequencing. Neither analysis method detected any BRAF mutations, and the numbers of PDGFRA and KRAS mutations were too small for researchers to draw meaningful conclusions.

When it came to KIT, however, there was a high degree of concordance between the tests where both types of samples from individual patients were available, including 100% agreement for primary KIT exon 9 mutations, 79% for primary KIT exon 11 mutations, and 84% overall for primary KIT exon 9 and 11 mutations.

The BEAMing technology can help determine prognosis of patients with GIST, Dr. Demetri said, noting that in the GRID trial, patients in the placebo arm who had secondary KIT mutations had shorter PFS than did patients without KIT mutations (HR, 1.82; P = .05). Patients with KIT exon 9 mutations had received a shorter course of imatinib than did the rest of the study population (HR, 2.02; P = .002) and a longer course of sunitinib (HR, 0.54; P = .005).

BEAMing analysis also showed that patients with secondary KIT mutations who received regorafenib had significantly better PFS than did patients in the placebo arm (HR, 0.22; P less than .001).

The data Dr. Demetri presented were "very exciting," said invited discussant Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel, professor of sarcoma oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

"The important take-home messages are that there is some very good concordance between the tumor tissue analysis and the plasma analysis," and that regorafenib "appears to be totally agnostic to any of the mutational subsets and seems to equally benefit all patients," Dr. Patel said.

The study was supported in part by Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Demetri disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to the company. Dr. Patel reported having no disclosures relevant to the study.

CHICAGO – A novel technique for ferreting out DNA mutations in circulating plasma appears to be more sensitive than is conventional pathology at detecting drug-resistant mutations in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, said an investigator at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Secondary KIT mutations associated with resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib (Gleevec) were detected in 47% of plasma samples using "BEAMing" (beads, emulsions, amplification, magnetics) technology, compared with only 12% of tissue biopsy specimens, said Dr. George D. Demetri, director of the center for sarcoma and bone oncology at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

"We know that tumor cells are constantly turning over, apoptosing, dying, and releasing free DNA into the bloodstream. I want to emphasize that this is not looking at circulating tumor cells; this is looking at free circulating DNA in the plasma, and by looking at that circulating DNA, we may be able to get a more comprehensive assessment of all the mutations from across all tumor burden in any given patient," Dr. Demetri said.

The technique, which some investigators have dubbed "liquid biopsy," involves treating plasma with beads coated with DNA sequences that are complementary to target mutational sequences to create an emulsion polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The PCR amplifies the circulating DNA, which can then be identified with flow cytometry. The test can detect one circulating DNA molecule per 10,000 in plasma, according to the American Association for Cancer Research.

Dr. Demetri and his colleagues used the technology to retrospectively study mutations from patient samples in the GRID (GIST-Regorafenib in Progressive Disease) phase III study. In that trial, regorafenib (Stivarga), a multikinase inhibitor, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) compared with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.27; P less than .0001) in patients with metastatic GIST after failure of both standard and targeted therapies, including imatinib and sunitinib (Sutent).

The investigators looked for primary and secondary mutations in KIT in both plasma samples (available for 163 of 199 patients in GRID) and tumor tissue (from 102 patients), and found that BEAMing detected mutations in 58% of plasma samples, compared with 66% of tumor samples analyzed by the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

In addition, BEAMing detected mutations in PDGFRA in 1% of samples, and in KRAS in one of two samples, compared with 3% and 1%, respectively, for sequencing. Neither analysis method detected any BRAF mutations, and the numbers of PDGFRA and KRAS mutations were too small for researchers to draw meaningful conclusions.

When it came to KIT, however, there was a high degree of concordance between the tests where both types of samples from individual patients were available, including 100% agreement for primary KIT exon 9 mutations, 79% for primary KIT exon 11 mutations, and 84% overall for primary KIT exon 9 and 11 mutations.

The BEAMing technology can help determine prognosis of patients with GIST, Dr. Demetri said, noting that in the GRID trial, patients in the placebo arm who had secondary KIT mutations had shorter PFS than did patients without KIT mutations (HR, 1.82; P = .05). Patients with KIT exon 9 mutations had received a shorter course of imatinib than did the rest of the study population (HR, 2.02; P = .002) and a longer course of sunitinib (HR, 0.54; P = .005).

BEAMing analysis also showed that patients with secondary KIT mutations who received regorafenib had significantly better PFS than did patients in the placebo arm (HR, 0.22; P less than .001).

The data Dr. Demetri presented were "very exciting," said invited discussant Dr. Shreyaskumar R. Patel, professor of sarcoma oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

"The important take-home messages are that there is some very good concordance between the tumor tissue analysis and the plasma analysis," and that regorafenib "appears to be totally agnostic to any of the mutational subsets and seems to equally benefit all patients," Dr. Patel said.

The study was supported in part by Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Demetri disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to the company. Dr. Patel reported having no disclosures relevant to the study.

AT THE ASCO ANNUAL MEETING 2013

Major finding: BEAMing plasma-analysis technology identified secondary KIT mutations in 47% of samples from patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), compared with 12% of tissue samples subjected to DNA sequencing.

Data source: Comparison study of mutational analysis techniques, a substudy of the GRID phase III trial in 199 patients with GIST.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Demetri disclosed serving as a scientific consultant to the company. Dr. Patel reported having no disclosures relevant to the study.

Including caregivers in patient care is an ethical imperative

Ms. Stout is a 58-year-old divorced mother of two. Her eldest son, Paul, aged 35, has cystic fibrosis and is the recipient of a lung transplant. He has several developmental delays, and his comprehension of medicolegal documents becomes quite limited when he is medically ill and on narcotics. His outpatient medical team is aware of this and includes his mother in all treatment decisions.

However, in the hospital, the medical teams do not appreciate his limitations. In the inpatient hospital setting, he does not retain information presented to him. They question his mother’s continual presence and see her as "overinvolved and enmeshed with her adult son." Ms. Stout says that she has to fight with each new physician team to get them to understand that they need to involve her in all her son’s health care decisions. The younger male physicians, especially, identify with Paul.

Paul presents as a well-adjusted young man. He is agreeable, open, and friendly with the staff. Paul has limited social contacts outside of the hospital. Because of his lengthy involvement in the hospital care system, he is comfortable in the hospital and especially enjoys his interaction with the female nurses. He understands basic procedures because they have been repeated so many times. However, he does not understand his complex health care needs. Unless his comprehension is specifically tested, his deficits go unrecognized.

His mother knows the details of his history and is a better resource than the chart. She insists on being present at all times, despite the demands of her other commitments. Each time her son is admitted, she faces scrutiny, and repeatedly has to explain herself and her son’s limitations to each new physician. She finds this situation exhausting and humiliating. She does not understand why her presence cannot be accepted as helpful.

The toll of caregiving

Family caregivers face many physical, emotional, and financial demands that make them vulnerable to stress-related conditions, both physical and psychological. Caregiving affects caregivers’ health, which, in turn, affects their ability to provide care. The Caregiver Health Effects Study demonstrated a strong link between caregiving and mortality risk, finding that elderly caregivers supporting disabled spouses at home were 63% more likely to die within 4 years than noncaregiving elderly spouses (JAMA 1999;282:2215-9). In addition, family caregivers often lack the time and energy to prepare their own meals, exercise, or engage in their own preventive medical care. Physicians must stress the importance of caregiver self-care for the benefit of both the caregiver and the patient, and identify appropriate sources of community support services, such as home health aides, respite, or adult day care.

In 2008, according to Suzanne Mintz, a cofounder of the National Family Caregivers Association, the estimated market value of the family caregivers’ services was $375 billion annually. Almost one-third of the U.S. population provides care for a chronically ill, disabled, or aged family member or friend during any given year and spends an average of 20 hours per week providing care for loved ones. Two-thirds of caregivers are women, and 13% of family caregivers are providing 40 hours of care a week or more.

The American Psychological Association has a "Caregiver Briefcase." The briefcase contains caregiving facts; a practice section with common caregiver problems and interventions; and sections on research, education, and advocacy. The website and its contents are useful for family members as well as professionals.

In addition, the American Psychological Association offers ways for family members to integrate into health care teams. For example, electronic medical records can allow family members access to portions such as the patient’s problem and medication lists and most recent laboratory findings. Family caregivers can provide ongoing, real-time observations about the patient through the portal, as well as share information about what it is like to be a family caregiver. Those secure messages become part of the patient’s permanent medical record.

Shifting patient decision making to family members is a delicate negotiation between the patient’s ability to make independent decisions and the family’s desire to protect the patient from potentially poor decisions. At critical times, the family has to step up and assume decision-making responsibility for the patient.

To help physicians understand the ethics of this process, the American College of Physicians offers guidelines to help the physician know how best to collaborate with the patient and the caregiver (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25:255-60). These guidelines are endorsed by 10 medical professional societies, including the Society of General Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Ethical guidelines for collaboration

When working with patients, making sure that six factors are met will help us do a better job of ensuring that the relationship with caregivers is productive for all three parties involved. Here is a listing:

• Respect the patient’s dignity, rights, and values in all patient-physician-caregiver interactions.

• Recognize that physician accessibility and excellent communication are fundamental to supporting the patient and family caregiver.

• Recognize the value of family caregivers as a source of continuity regarding the patient’s medical and psychosocial history.

• Facilitate end of life adjustments for the family.

• Ensure appropriate boundaries when the caregiver is a health care professional.

• Ensure the caregiver receives appropriate support, referrals, and services.

Our failure to use patient and family-centered care (PFCC) is tied to attitudinal, educational, and organizational barriers. The first attitudinal barrier is the expectation that families will be unreasonable. The second is that families will compromise confidentiality. The third is that physicians are largely unaware of research on the benefits of PFCC. Finally, physicians believe that PFCC is time consuming and costs too much.

Educational barriers include the lack of skills needed for collaboration among professionals, administrators, patients, and families.

Organizational barriers that get in the way of PFCC are the lack of guiding vision, the top-down approach with insufficient effort to build staff commitment; grassroots effort that lacks leadership, commitment, and support; scarce fiscal resources and competing priorities; and the absence of a funded coordinator.

Psychiatric illnesses are chronic medical illnesses. As more people have experiences as patients and caregivers, the pressure to involve family members such as Ms. Stout increases. Where does the resistance to involving family members in patient care come from? There is an unfounded, unspoken fear on the part of health professionals that families want something that the health care provider cannot guarantee – that their relative "will get well and everything will be fine." Health care providers might limit what they say to family members in order "not to upset them." If the family members perceive that they are being brushed off and dismissed, they can develop feelings of apprehension. A small upset or misunderstanding can then unleash repressed feelings, resulting in family members lashing out. When health care teams include the family and develop collaborative relationships with families, the likelihood of this kind of conflict is reduced.

Resistance also comes from the perception that family involvement is not necessary for patient care. Many of the consequences of isolating patients from their family are invisible, such as relationship strain, role changes, and caregiver burden. The reality is that, for patients such as Ms. Stout’s son, his mother’s involvement helps his medical team do a better job of managing his care.

It is time that psychiatry, and specifically the American Psychiatric Association, develop ethical guidelines outlining how to work with families of patients with chronic psychiatric illness. At the very least, we should sign on with other medical specialties by endorsing the American College of Physicians’ ethical guidelines described above. We have lagged behind the rest of medicine by failing to address this important issue.

This column, "Families in Psychiatry," appears regularly in Clinical Psychiatry News, a publication of IMNG Medical Media. Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Ms. Stout is a 58-year-old divorced mother of two. Her eldest son, Paul, aged 35, has cystic fibrosis and is the recipient of a lung transplant. He has several developmental delays, and his comprehension of medicolegal documents becomes quite limited when he is medically ill and on narcotics. His outpatient medical team is aware of this and includes his mother in all treatment decisions.

However, in the hospital, the medical teams do not appreciate his limitations. In the inpatient hospital setting, he does not retain information presented to him. They question his mother’s continual presence and see her as "overinvolved and enmeshed with her adult son." Ms. Stout says that she has to fight with each new physician team to get them to understand that they need to involve her in all her son’s health care decisions. The younger male physicians, especially, identify with Paul.

Paul presents as a well-adjusted young man. He is agreeable, open, and friendly with the staff. Paul has limited social contacts outside of the hospital. Because of his lengthy involvement in the hospital care system, he is comfortable in the hospital and especially enjoys his interaction with the female nurses. He understands basic procedures because they have been repeated so many times. However, he does not understand his complex health care needs. Unless his comprehension is specifically tested, his deficits go unrecognized.

His mother knows the details of his history and is a better resource than the chart. She insists on being present at all times, despite the demands of her other commitments. Each time her son is admitted, she faces scrutiny, and repeatedly has to explain herself and her son’s limitations to each new physician. She finds this situation exhausting and humiliating. She does not understand why her presence cannot be accepted as helpful.

The toll of caregiving

Family caregivers face many physical, emotional, and financial demands that make them vulnerable to stress-related conditions, both physical and psychological. Caregiving affects caregivers’ health, which, in turn, affects their ability to provide care. The Caregiver Health Effects Study demonstrated a strong link between caregiving and mortality risk, finding that elderly caregivers supporting disabled spouses at home were 63% more likely to die within 4 years than noncaregiving elderly spouses (JAMA 1999;282:2215-9). In addition, family caregivers often lack the time and energy to prepare their own meals, exercise, or engage in their own preventive medical care. Physicians must stress the importance of caregiver self-care for the benefit of both the caregiver and the patient, and identify appropriate sources of community support services, such as home health aides, respite, or adult day care.

In 2008, according to Suzanne Mintz, a cofounder of the National Family Caregivers Association, the estimated market value of the family caregivers’ services was $375 billion annually. Almost one-third of the U.S. population provides care for a chronically ill, disabled, or aged family member or friend during any given year and spends an average of 20 hours per week providing care for loved ones. Two-thirds of caregivers are women, and 13% of family caregivers are providing 40 hours of care a week or more.

The American Psychological Association has a "Caregiver Briefcase." The briefcase contains caregiving facts; a practice section with common caregiver problems and interventions; and sections on research, education, and advocacy. The website and its contents are useful for family members as well as professionals.

In addition, the American Psychological Association offers ways for family members to integrate into health care teams. For example, electronic medical records can allow family members access to portions such as the patient’s problem and medication lists and most recent laboratory findings. Family caregivers can provide ongoing, real-time observations about the patient through the portal, as well as share information about what it is like to be a family caregiver. Those secure messages become part of the patient’s permanent medical record.

Shifting patient decision making to family members is a delicate negotiation between the patient’s ability to make independent decisions and the family’s desire to protect the patient from potentially poor decisions. At critical times, the family has to step up and assume decision-making responsibility for the patient.

To help physicians understand the ethics of this process, the American College of Physicians offers guidelines to help the physician know how best to collaborate with the patient and the caregiver (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25:255-60). These guidelines are endorsed by 10 medical professional societies, including the Society of General Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Ethical guidelines for collaboration

When working with patients, making sure that six factors are met will help us do a better job of ensuring that the relationship with caregivers is productive for all three parties involved. Here is a listing:

• Respect the patient’s dignity, rights, and values in all patient-physician-caregiver interactions.

• Recognize that physician accessibility and excellent communication are fundamental to supporting the patient and family caregiver.

• Recognize the value of family caregivers as a source of continuity regarding the patient’s medical and psychosocial history.

• Facilitate end of life adjustments for the family.

• Ensure appropriate boundaries when the caregiver is a health care professional.

• Ensure the caregiver receives appropriate support, referrals, and services.

Our failure to use patient and family-centered care (PFCC) is tied to attitudinal, educational, and organizational barriers. The first attitudinal barrier is the expectation that families will be unreasonable. The second is that families will compromise confidentiality. The third is that physicians are largely unaware of research on the benefits of PFCC. Finally, physicians believe that PFCC is time consuming and costs too much.

Educational barriers include the lack of skills needed for collaboration among professionals, administrators, patients, and families.

Organizational barriers that get in the way of PFCC are the lack of guiding vision, the top-down approach with insufficient effort to build staff commitment; grassroots effort that lacks leadership, commitment, and support; scarce fiscal resources and competing priorities; and the absence of a funded coordinator.

Psychiatric illnesses are chronic medical illnesses. As more people have experiences as patients and caregivers, the pressure to involve family members such as Ms. Stout increases. Where does the resistance to involving family members in patient care come from? There is an unfounded, unspoken fear on the part of health professionals that families want something that the health care provider cannot guarantee – that their relative "will get well and everything will be fine." Health care providers might limit what they say to family members in order "not to upset them." If the family members perceive that they are being brushed off and dismissed, they can develop feelings of apprehension. A small upset or misunderstanding can then unleash repressed feelings, resulting in family members lashing out. When health care teams include the family and develop collaborative relationships with families, the likelihood of this kind of conflict is reduced.

Resistance also comes from the perception that family involvement is not necessary for patient care. Many of the consequences of isolating patients from their family are invisible, such as relationship strain, role changes, and caregiver burden. The reality is that, for patients such as Ms. Stout’s son, his mother’s involvement helps his medical team do a better job of managing his care.

It is time that psychiatry, and specifically the American Psychiatric Association, develop ethical guidelines outlining how to work with families of patients with chronic psychiatric illness. At the very least, we should sign on with other medical specialties by endorsing the American College of Physicians’ ethical guidelines described above. We have lagged behind the rest of medicine by failing to address this important issue.

This column, "Families in Psychiatry," appears regularly in Clinical Psychiatry News, a publication of IMNG Medical Media. Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Ms. Stout is a 58-year-old divorced mother of two. Her eldest son, Paul, aged 35, has cystic fibrosis and is the recipient of a lung transplant. He has several developmental delays, and his comprehension of medicolegal documents becomes quite limited when he is medically ill and on narcotics. His outpatient medical team is aware of this and includes his mother in all treatment decisions.

However, in the hospital, the medical teams do not appreciate his limitations. In the inpatient hospital setting, he does not retain information presented to him. They question his mother’s continual presence and see her as "overinvolved and enmeshed with her adult son." Ms. Stout says that she has to fight with each new physician team to get them to understand that they need to involve her in all her son’s health care decisions. The younger male physicians, especially, identify with Paul.

Paul presents as a well-adjusted young man. He is agreeable, open, and friendly with the staff. Paul has limited social contacts outside of the hospital. Because of his lengthy involvement in the hospital care system, he is comfortable in the hospital and especially enjoys his interaction with the female nurses. He understands basic procedures because they have been repeated so many times. However, he does not understand his complex health care needs. Unless his comprehension is specifically tested, his deficits go unrecognized.

His mother knows the details of his history and is a better resource than the chart. She insists on being present at all times, despite the demands of her other commitments. Each time her son is admitted, she faces scrutiny, and repeatedly has to explain herself and her son’s limitations to each new physician. She finds this situation exhausting and humiliating. She does not understand why her presence cannot be accepted as helpful.

The toll of caregiving

Family caregivers face many physical, emotional, and financial demands that make them vulnerable to stress-related conditions, both physical and psychological. Caregiving affects caregivers’ health, which, in turn, affects their ability to provide care. The Caregiver Health Effects Study demonstrated a strong link between caregiving and mortality risk, finding that elderly caregivers supporting disabled spouses at home were 63% more likely to die within 4 years than noncaregiving elderly spouses (JAMA 1999;282:2215-9). In addition, family caregivers often lack the time and energy to prepare their own meals, exercise, or engage in their own preventive medical care. Physicians must stress the importance of caregiver self-care for the benefit of both the caregiver and the patient, and identify appropriate sources of community support services, such as home health aides, respite, or adult day care.

In 2008, according to Suzanne Mintz, a cofounder of the National Family Caregivers Association, the estimated market value of the family caregivers’ services was $375 billion annually. Almost one-third of the U.S. population provides care for a chronically ill, disabled, or aged family member or friend during any given year and spends an average of 20 hours per week providing care for loved ones. Two-thirds of caregivers are women, and 13% of family caregivers are providing 40 hours of care a week or more.

The American Psychological Association has a "Caregiver Briefcase." The briefcase contains caregiving facts; a practice section with common caregiver problems and interventions; and sections on research, education, and advocacy. The website and its contents are useful for family members as well as professionals.

In addition, the American Psychological Association offers ways for family members to integrate into health care teams. For example, electronic medical records can allow family members access to portions such as the patient’s problem and medication lists and most recent laboratory findings. Family caregivers can provide ongoing, real-time observations about the patient through the portal, as well as share information about what it is like to be a family caregiver. Those secure messages become part of the patient’s permanent medical record.

Shifting patient decision making to family members is a delicate negotiation between the patient’s ability to make independent decisions and the family’s desire to protect the patient from potentially poor decisions. At critical times, the family has to step up and assume decision-making responsibility for the patient.

To help physicians understand the ethics of this process, the American College of Physicians offers guidelines to help the physician know how best to collaborate with the patient and the caregiver (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010;25:255-60). These guidelines are endorsed by 10 medical professional societies, including the Society of General Internal Medicine, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine.

Ethical guidelines for collaboration

When working with patients, making sure that six factors are met will help us do a better job of ensuring that the relationship with caregivers is productive for all three parties involved. Here is a listing:

• Respect the patient’s dignity, rights, and values in all patient-physician-caregiver interactions.

• Recognize that physician accessibility and excellent communication are fundamental to supporting the patient and family caregiver.

• Recognize the value of family caregivers as a source of continuity regarding the patient’s medical and psychosocial history.

• Facilitate end of life adjustments for the family.

• Ensure appropriate boundaries when the caregiver is a health care professional.

• Ensure the caregiver receives appropriate support, referrals, and services.

Our failure to use patient and family-centered care (PFCC) is tied to attitudinal, educational, and organizational barriers. The first attitudinal barrier is the expectation that families will be unreasonable. The second is that families will compromise confidentiality. The third is that physicians are largely unaware of research on the benefits of PFCC. Finally, physicians believe that PFCC is time consuming and costs too much.

Educational barriers include the lack of skills needed for collaboration among professionals, administrators, patients, and families.

Organizational barriers that get in the way of PFCC are the lack of guiding vision, the top-down approach with insufficient effort to build staff commitment; grassroots effort that lacks leadership, commitment, and support; scarce fiscal resources and competing priorities; and the absence of a funded coordinator.

Psychiatric illnesses are chronic medical illnesses. As more people have experiences as patients and caregivers, the pressure to involve family members such as Ms. Stout increases. Where does the resistance to involving family members in patient care come from? There is an unfounded, unspoken fear on the part of health professionals that families want something that the health care provider cannot guarantee – that their relative "will get well and everything will be fine." Health care providers might limit what they say to family members in order "not to upset them." If the family members perceive that they are being brushed off and dismissed, they can develop feelings of apprehension. A small upset or misunderstanding can then unleash repressed feelings, resulting in family members lashing out. When health care teams include the family and develop collaborative relationships with families, the likelihood of this kind of conflict is reduced.

Resistance also comes from the perception that family involvement is not necessary for patient care. Many of the consequences of isolating patients from their family are invisible, such as relationship strain, role changes, and caregiver burden. The reality is that, for patients such as Ms. Stout’s son, his mother’s involvement helps his medical team do a better job of managing his care.

It is time that psychiatry, and specifically the American Psychiatric Association, develop ethical guidelines outlining how to work with families of patients with chronic psychiatric illness. At the very least, we should sign on with other medical specialties by endorsing the American College of Physicians’ ethical guidelines described above. We have lagged behind the rest of medicine by failing to address this important issue.

This column, "Families in Psychiatry," appears regularly in Clinical Psychiatry News, a publication of IMNG Medical Media. Dr. Heru is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of the recently published book, "Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals" (New York: Routledge, 2013).

When health care has a tail

Is your hospital going to the dogs? Perhaps, that is, if your hospital administrators believe in AAT.

That’s not a new randomized placebo-controlled trial for a nifty new medication? Far less complex, it is the simple acronym for animal-assisted therapy, a novel therapeutic modality that is spreading across the country.

I was surprised the first time I saw a canine proudly strutting down the hall of a hospital like he belonged there, but it makes perfect sense. Numerous studies have shown the positive psychological, physical, and even survival benefits of pet ownership. For many, their pet is a beloved member of the family.

But does AAT really work? Apparently so.

Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights, Ill., utilizes AAT regularly to improve both the emotional and physical well-being of its patients. The renowned UCLA Medical Center has gone four-legged. The UCLA People-Animal Connection (PAC) is one of America’s most comprehensive animal-assisted therapy and activity programs. Even the Joint Commission uses PAC’s protocols to promote AAT, both here and abroad.

According to research published in the American Journal of Critical Care (2008;17:373-6), the benefits of AAT are primarily the result of "contact comfort," a tactile process during which unconditional attachment bonds form between humans and animals, leading to relaxation by reducing cardiovascular reactivity to stress. AAT was found to improve hemodynamics in patients with advanced heart failure by reducing right atrial pressure, both systolic and diastolic pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and neurohormone levels.

So the next time you see a dog and his owner stroll down the halls of your hospital, step aside. They have an important job to do as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a mobile app for iOS.

Is your hospital going to the dogs? Perhaps, that is, if your hospital administrators believe in AAT.

That’s not a new randomized placebo-controlled trial for a nifty new medication? Far less complex, it is the simple acronym for animal-assisted therapy, a novel therapeutic modality that is spreading across the country.

I was surprised the first time I saw a canine proudly strutting down the hall of a hospital like he belonged there, but it makes perfect sense. Numerous studies have shown the positive psychological, physical, and even survival benefits of pet ownership. For many, their pet is a beloved member of the family.

But does AAT really work? Apparently so.

Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights, Ill., utilizes AAT regularly to improve both the emotional and physical well-being of its patients. The renowned UCLA Medical Center has gone four-legged. The UCLA People-Animal Connection (PAC) is one of America’s most comprehensive animal-assisted therapy and activity programs. Even the Joint Commission uses PAC’s protocols to promote AAT, both here and abroad.

According to research published in the American Journal of Critical Care (2008;17:373-6), the benefits of AAT are primarily the result of "contact comfort," a tactile process during which unconditional attachment bonds form between humans and animals, leading to relaxation by reducing cardiovascular reactivity to stress. AAT was found to improve hemodynamics in patients with advanced heart failure by reducing right atrial pressure, both systolic and diastolic pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and neurohormone levels.

So the next time you see a dog and his owner stroll down the halls of your hospital, step aside. They have an important job to do as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a mobile app for iOS.

Is your hospital going to the dogs? Perhaps, that is, if your hospital administrators believe in AAT.

That’s not a new randomized placebo-controlled trial for a nifty new medication? Far less complex, it is the simple acronym for animal-assisted therapy, a novel therapeutic modality that is spreading across the country.

I was surprised the first time I saw a canine proudly strutting down the hall of a hospital like he belonged there, but it makes perfect sense. Numerous studies have shown the positive psychological, physical, and even survival benefits of pet ownership. For many, their pet is a beloved member of the family.

But does AAT really work? Apparently so.

Northwest Community Hospital in Arlington Heights, Ill., utilizes AAT regularly to improve both the emotional and physical well-being of its patients. The renowned UCLA Medical Center has gone four-legged. The UCLA People-Animal Connection (PAC) is one of America’s most comprehensive animal-assisted therapy and activity programs. Even the Joint Commission uses PAC’s protocols to promote AAT, both here and abroad.

According to research published in the American Journal of Critical Care (2008;17:373-6), the benefits of AAT are primarily the result of "contact comfort," a tactile process during which unconditional attachment bonds form between humans and animals, leading to relaxation by reducing cardiovascular reactivity to stress. AAT was found to improve hemodynamics in patients with advanced heart failure by reducing right atrial pressure, both systolic and diastolic pulmonary artery pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and neurohormone levels.

So the next time you see a dog and his owner stroll down the halls of your hospital, step aside. They have an important job to do as well.

Dr. Hester is a hospitalist with Baltimore-Washington Medical Center, Glen Burnie, Md., who has a passion for empowering patients to partner in their health care. She is the creator of the Patient Whiz, a mobile app for iOS.

Early Fibrinolysis Effective in STEMI but Causes More Strokes (STREAM)

Clinical question

Is early fibrinolysis followed by angiography an effective strategy for patients with STEMI presenting to hospitals without the capability to perform percutaneous coronary intervention?

Bottom line

Current guidelines recommend primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a door-to-balloon time of 90 minutes for patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, this can be difficult to achieve, especially in remote areas without prompt access to PCI. This study finds that early fibrinolysis plus adjunctive antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy followed by coronary angiography within 24 hours is effective in preventing adverse outcomes in patients presenting with recent onset symptoms of STEMI in whom PCI within 1 hour is not feasible. However, fibrinolysis therapy leads to a higher rate of ischemic strokes and intracranial bleeding, suggesting that timely PCI is still the optimal therapy for these patients. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Industry

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators randomized 1892 patients who presented within 3 hours after onset of symptoms of STEMI but could not undergo PCI within 1 hour to receive 1 of 2 interventions: immediate transfer to a PCI-capable facility, or initial fibrinolysis treatment with tenecteplase followed by angiography within 24 hours. The fibrinolysis group also received enoxaparin and clopidogrel as adjunctive therapy. The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, shock, congestive heart failure, or reinfarction at 30 days. Baseline characteristics were similar in the 2 groups, except for a higher frequency of previous congestive heart failure in the PCI group. Partway through the trial, the dose of tenecteplase was halved in patients 75 years or older because of a higher frequency of intracranial bleeds in this group. The median time from symptom onset to start of reperfusion therapy (either initiation of fibrinolysis or arterial sheath insertion for PCI) was shorter in the fibrinolysis group (100 minutes vs 178 minutes; P < .0001). However, one third of the patients in the fibrinolysis group required rescue PCI because of failed reperfusion. Overall, there were no significant differences detected between the 2 groups in either the primary endpoint or in the individual components of the endpoint. The fibrinolysis group had a higher rate of total hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes (1.6% vs 0.5%; P = .03).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Is early fibrinolysis followed by angiography an effective strategy for patients with STEMI presenting to hospitals without the capability to perform percutaneous coronary intervention?

Bottom line

Current guidelines recommend primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a door-to-balloon time of 90 minutes for patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, this can be difficult to achieve, especially in remote areas without prompt access to PCI. This study finds that early fibrinolysis plus adjunctive antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy followed by coronary angiography within 24 hours is effective in preventing adverse outcomes in patients presenting with recent onset symptoms of STEMI in whom PCI within 1 hour is not feasible. However, fibrinolysis therapy leads to a higher rate of ischemic strokes and intracranial bleeding, suggesting that timely PCI is still the optimal therapy for these patients. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Industry

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators randomized 1892 patients who presented within 3 hours after onset of symptoms of STEMI but could not undergo PCI within 1 hour to receive 1 of 2 interventions: immediate transfer to a PCI-capable facility, or initial fibrinolysis treatment with tenecteplase followed by angiography within 24 hours. The fibrinolysis group also received enoxaparin and clopidogrel as adjunctive therapy. The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, shock, congestive heart failure, or reinfarction at 30 days. Baseline characteristics were similar in the 2 groups, except for a higher frequency of previous congestive heart failure in the PCI group. Partway through the trial, the dose of tenecteplase was halved in patients 75 years or older because of a higher frequency of intracranial bleeds in this group. The median time from symptom onset to start of reperfusion therapy (either initiation of fibrinolysis or arterial sheath insertion for PCI) was shorter in the fibrinolysis group (100 minutes vs 178 minutes; P < .0001). However, one third of the patients in the fibrinolysis group required rescue PCI because of failed reperfusion. Overall, there were no significant differences detected between the 2 groups in either the primary endpoint or in the individual components of the endpoint. The fibrinolysis group had a higher rate of total hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes (1.6% vs 0.5%; P = .03).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Is early fibrinolysis followed by angiography an effective strategy for patients with STEMI presenting to hospitals without the capability to perform percutaneous coronary intervention?

Bottom line

Current guidelines recommend primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a door-to-balloon time of 90 minutes for patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, this can be difficult to achieve, especially in remote areas without prompt access to PCI. This study finds that early fibrinolysis plus adjunctive antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy followed by coronary angiography within 24 hours is effective in preventing adverse outcomes in patients presenting with recent onset symptoms of STEMI in whom PCI within 1 hour is not feasible. However, fibrinolysis therapy leads to a higher rate of ischemic strokes and intracranial bleeding, suggesting that timely PCI is still the optimal therapy for these patients. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Industry

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators randomized 1892 patients who presented within 3 hours after onset of symptoms of STEMI but could not undergo PCI within 1 hour to receive 1 of 2 interventions: immediate transfer to a PCI-capable facility, or initial fibrinolysis treatment with tenecteplase followed by angiography within 24 hours. The fibrinolysis group also received enoxaparin and clopidogrel as adjunctive therapy. The primary endpoint was the composite of all-cause mortality, shock, congestive heart failure, or reinfarction at 30 days. Baseline characteristics were similar in the 2 groups, except for a higher frequency of previous congestive heart failure in the PCI group. Partway through the trial, the dose of tenecteplase was halved in patients 75 years or older because of a higher frequency of intracranial bleeds in this group. The median time from symptom onset to start of reperfusion therapy (either initiation of fibrinolysis or arterial sheath insertion for PCI) was shorter in the fibrinolysis group (100 minutes vs 178 minutes; P < .0001). However, one third of the patients in the fibrinolysis group required rescue PCI because of failed reperfusion. Overall, there were no significant differences detected between the 2 groups in either the primary endpoint or in the individual components of the endpoint. The fibrinolysis group had a higher rate of total hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes (1.6% vs 0.5%; P = .03).

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

No Difference in Long-Term Outcomes with Full vs Trophic Feeding for Acute Lung Injury Patients

Clinical question

Does initial trophic feeding, as compared with full feeding, affect long-term outcomes in critically ill patients with acute lung injury?

Bottom line

There were no significant long-term differences in physical function, survival, psychological symptoms, or cognitive function in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding as compared with full enteral feeding. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Low-energy permissive underfeeding, or "trophic feeding," is one proposed nutritional strategy for mechanically ventilated patients. The previously published EDEN trial showed no significant differences in short-term mortality or ventilation-free days in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding versus full enteral feeding (Rice, et al. JAMA 2012;307(8):795-803). In this follow-up of the EDEN trial, investigators examined the long-term effects of this intervention. The patients included in the EDEN trial had acute lung injury primarily due to pneumonia or sepsis and had a mean age of 52 years. The patients were randomized to either full feeding (meeting 80% of the caloric goal) or trophic feeding (meeting 25% of the caloric goal) for up to 6 days. Of the 951 patients in the initial EDEN trial, 563 consented to this follow-up study. Research staff interviewed the surviving participants at 6 months (n = 514) and at 12 months (n = 487). Taken together, these patients had decreased physical and mental abilities as compared with population norms, impaired quality of life and return to work, and increased psychological symptoms. When comparing the full feeding cohort with the patients that received trophic feeding, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of physical function at 6 or 12 months as assessed by the Short-form Health Outcomes Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 mental health measures favored the trophic feeding group at 12 months, but the differences in scores were small. Overall, there were no differences in specific psychological symptoms -- such as anxiety or depression, 12-month survival, cognitive function, or employment status -- between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does initial trophic feeding, as compared with full feeding, affect long-term outcomes in critically ill patients with acute lung injury?

Bottom line

There were no significant long-term differences in physical function, survival, psychological symptoms, or cognitive function in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding as compared with full enteral feeding. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Low-energy permissive underfeeding, or "trophic feeding," is one proposed nutritional strategy for mechanically ventilated patients. The previously published EDEN trial showed no significant differences in short-term mortality or ventilation-free days in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding versus full enteral feeding (Rice, et al. JAMA 2012;307(8):795-803). In this follow-up of the EDEN trial, investigators examined the long-term effects of this intervention. The patients included in the EDEN trial had acute lung injury primarily due to pneumonia or sepsis and had a mean age of 52 years. The patients were randomized to either full feeding (meeting 80% of the caloric goal) or trophic feeding (meeting 25% of the caloric goal) for up to 6 days. Of the 951 patients in the initial EDEN trial, 563 consented to this follow-up study. Research staff interviewed the surviving participants at 6 months (n = 514) and at 12 months (n = 487). Taken together, these patients had decreased physical and mental abilities as compared with population norms, impaired quality of life and return to work, and increased psychological symptoms. When comparing the full feeding cohort with the patients that received trophic feeding, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of physical function at 6 or 12 months as assessed by the Short-form Health Outcomes Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 mental health measures favored the trophic feeding group at 12 months, but the differences in scores were small. Overall, there were no differences in specific psychological symptoms -- such as anxiety or depression, 12-month survival, cognitive function, or employment status -- between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does initial trophic feeding, as compared with full feeding, affect long-term outcomes in critically ill patients with acute lung injury?

Bottom line

There were no significant long-term differences in physical function, survival, psychological symptoms, or cognitive function in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding as compared with full enteral feeding. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Low-energy permissive underfeeding, or "trophic feeding," is one proposed nutritional strategy for mechanically ventilated patients. The previously published EDEN trial showed no significant differences in short-term mortality or ventilation-free days in patients with acute lung injury who received initial trophic feeding versus full enteral feeding (Rice, et al. JAMA 2012;307(8):795-803). In this follow-up of the EDEN trial, investigators examined the long-term effects of this intervention. The patients included in the EDEN trial had acute lung injury primarily due to pneumonia or sepsis and had a mean age of 52 years. The patients were randomized to either full feeding (meeting 80% of the caloric goal) or trophic feeding (meeting 25% of the caloric goal) for up to 6 days. Of the 951 patients in the initial EDEN trial, 563 consented to this follow-up study. Research staff interviewed the surviving participants at 6 months (n = 514) and at 12 months (n = 487). Taken together, these patients had decreased physical and mental abilities as compared with population norms, impaired quality of life and return to work, and increased psychological symptoms. When comparing the full feeding cohort with the patients that received trophic feeding, there was no significant difference in the primary outcome of physical function at 6 or 12 months as assessed by the Short-form Health Outcomes Survey (SF-36). The SF-36 mental health measures favored the trophic feeding group at 12 months, but the differences in scores were small. Overall, there were no differences in specific psychological symptoms -- such as anxiety or depression, 12-month survival, cognitive function, or employment status -- between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Kudos to our departing Medical Editor, Dr. George Andros

Dr. George Andros, departing Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist, was presented with a Presidential Citation Award by Dr. Peter Gloviczki in recognition of his exemplary service to the Society for Vascular Surgery for outstanding editorial leadership of Vascular Specialist. He received the award during the SVS Business Meeting May 31 at the Vascular Annual Meeting.

Dr. Andros succeeded Dr. K. Wayne Johnston as only the second medical editor of Vascular Specialist. Under his esteemed leadership over the past years, Vascular Specialist has widened its coverage of vascular surgery and entered the online world with online-only editions, e-newsletters, and a website.

He installed a stellar board of editorial advisors from across the United States and the world and inspired them to provide the insightful commentaries that have so enhanced our pages.

As managing editor, I would personally like to thank Dr. Andros for his commitment, professionalism, and friendship throughout this time.

Dr. Andros will be succeeded by Dr. Russell Samson, who will begin his medical editor duties with the August print edition of Vascular Specialist.

Mark Lesney

Managing Editor, Vascular Specialist

Dr. George Andros, departing Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist, was presented with a Presidential Citation Award by Dr. Peter Gloviczki in recognition of his exemplary service to the Society for Vascular Surgery for outstanding editorial leadership of Vascular Specialist. He received the award during the SVS Business Meeting May 31 at the Vascular Annual Meeting.

Dr. Andros succeeded Dr. K. Wayne Johnston as only the second medical editor of Vascular Specialist. Under his esteemed leadership over the past years, Vascular Specialist has widened its coverage of vascular surgery and entered the online world with online-only editions, e-newsletters, and a website.

He installed a stellar board of editorial advisors from across the United States and the world and inspired them to provide the insightful commentaries that have so enhanced our pages.

As managing editor, I would personally like to thank Dr. Andros for his commitment, professionalism, and friendship throughout this time.

Dr. Andros will be succeeded by Dr. Russell Samson, who will begin his medical editor duties with the August print edition of Vascular Specialist.

Mark Lesney

Managing Editor, Vascular Specialist

Dr. George Andros, departing Medical Editor of Vascular Specialist, was presented with a Presidential Citation Award by Dr. Peter Gloviczki in recognition of his exemplary service to the Society for Vascular Surgery for outstanding editorial leadership of Vascular Specialist. He received the award during the SVS Business Meeting May 31 at the Vascular Annual Meeting.

Dr. Andros succeeded Dr. K. Wayne Johnston as only the second medical editor of Vascular Specialist. Under his esteemed leadership over the past years, Vascular Specialist has widened its coverage of vascular surgery and entered the online world with online-only editions, e-newsletters, and a website.

He installed a stellar board of editorial advisors from across the United States and the world and inspired them to provide the insightful commentaries that have so enhanced our pages.

As managing editor, I would personally like to thank Dr. Andros for his commitment, professionalism, and friendship throughout this time.

Dr. Andros will be succeeded by Dr. Russell Samson, who will begin his medical editor duties with the August print edition of Vascular Specialist.

Mark Lesney

Managing Editor, Vascular Specialist

A teen who is wasting away

CASE: Weak and passive

Cassandra, age 17, recently was discharged from a medical rehabilitation facility with a diagnosis of conversion disorder. Her school performance and attendance had been steadily declining for the last 6 months as she lost strength and motivation to take care of herself. Cassandra lives with her father, who is her primary caretaker. Her parents are separated and her mother has fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome, which leaves her unable to care for her daughter or participate in appointments.

Now lethargic and wasting away physically, Cassandra is pushed in a wheelchair by her weary father into a child psychiatrist’s office. She does not look up or make eye contact. Her father says “the doctors didn’t know what they were doing. That needle test, a nerve conduction study they did, is what made her worse.” Although Cassandra moves her arms to adjust herself in the wheelchair, she does not move her legs or try to move the wheelchair.

Cassandra’s father states that she has “congenital neuromyopathy. Her mother gave it to her in utero. But nobody listens to me or orders the tests that will prove I am right.” He insists on obscure and specialized blood tests and immune function panels to prove that a congenital condition is causing his daughter’s deterioration and physical debility. He is unwilling to accept that there is any other cause of her condition.

Cassandra’s father is unemployed and has no social contacts or supports. He asserts that “the medical system” is against him, and he believes medical interventions are harming his daughter. He keeps Cassandra isolated from friends and other family members.

How would you proceed?

a) separate Cassandra from her father during the interview

b) contact Cassandra’s mother for collateral information

c) assure Cassandra that there is no medical cause for her physical condition

d) order the testing her father requests

EVALUATION: Demoralized, hopeless

Cassandra is uncooperative with the interview and answers questions with one-word answers. Her affect is irritable and her demeanor is frustrated. She does not seem concerned that she needs assistance with eating and toileting.

When outpatient treatment with her primary care physician did not stop her physical deterioration, she was referred to a tertiary care academic medical center for a complete medical and neurologic workup. The workup, including an MRI, electroencephalogram, nerve conduction studies, and full immunologic panels, was negative for any physical illness, including neuromuscular degenerative disease. A muscle biopsy was considered, but not ordered because Cassandra and her father resisted.

During this hospitalization, she was diagnosed with conversion disorder by the psychiatry consultation service, and transferred to a physical rehabilitation facility for further care. At the rehab facility, Cassandra’s father interfered with her care, arguing constantly with the medical team. Cassandra demonstrated no effort to work with physical or occupational therapy and was discharged after 2 weeks because of noncompliance with treatment. Cassandra and her father are resentful that no physical cause was found and feel that the medical workup and time at the rehabilitation facility made her condition worse. The rehabilitation hospital referred Cassandra to an outpatient child psychiatrist for follow-up.

During the intake evaluation and follow-up appointments with the child psychiatrist, her affect is negativistic and restrictive. She is resistant to talking about her condition and accepting psychotherapeutic interventions. She is quick to blame others for her lack of progress and unable to take responsibility for working on her treatment plan. Cassandra feels demoralized, depressed, and hopeless about her situation and prospects for recovery. She feels that no one is listening to her father and if “they did just the tests he wants, we will know what is wrong with me and that he is right.”

The author’s observations

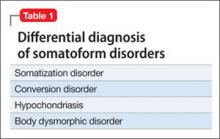

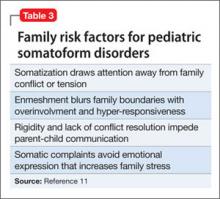

Table 1 lists conditions to consider in the differential diagnosis of conversion disorder. Although Cassandra’s conversion disorder diagnosis appears to be appropriate, it is important to consider 2 other possibilities: delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features, and Munchausen syndrome by proxy. An underlying depressive or anxiety disorder also should be considered and treated appropriately.

Conversion disorder has a challenging and often complex presentation in children and adolescents. Conversion disorders in children commonly are associated with stressful family situations including divorce, marital conflict, or loss of a close family member.1 An overbearing and conflict-prone parenting style also is associated with childhood conversion disorders.2 Common physical symptoms in conversion disorder are functional abdominal pain, partial paralysis, numbness, or seizures. Individuals such as Cassandra who are unable to express or verbalize their emotional distress are vulnerable to expressing their distress in somatic symptoms. Cassandra demonstrates La belle indifference, the characteristic attitude of not being overly concerned about what others would consider an alarming functional impairment.

Delusional disorder. A diagnosis of delusional disorder, somatic type with familial features was considered because Cassandra and her father shared persecutory and paranoid beliefs that her condition was brought on by some hidden, unrecognized medical condition. A delusional disorder with shared or “familial” features develops when a parent has strongly held delusional beliefs that are transferred to the child. Typically, it develops within the context of a close relationship with the parent, is similar in content to the parent’s belief, and is not preceded by psychosis or prodromal to schizophrenia.3

Because Cassandra’s father transferred his delusional system to his daughter, she clung to the belief that her physical symptoms and immobility were caused by medical misdiagnosis and failure to recognize her illness. Cassandra’s father strongly resisted and defended against accepting his role in her medical condition.

Munchausen by proxy. Because Cassandra and her father share a delusional system that prevented her from accepting and following treatment recommendations, it is possible that her father created her condition. Munchausen syndrome by proxy is a condition whereby illness-producing behavior in a child is exaggerated, fabricated, or induced by a parent or guardian.4 Separating Cassandra from her father and initiating antipsychotic treatment for him are critical considerations for her recovery.

How would you treat Cassandra?

a) call Child Protective Services (CPS) to remove Cassandra from her father’s custody

b) hospitalize Cassandra for intensive treatment of conversion disorder

c) start Cassandra on an atypical antipsychotic

d) begin cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and an antidepressant

Treatment approach

Treating a patient with a conversion disorder, somatic type starts with validating that the patient’s and parent’s distress is real to them (Table 2).5 The clinician acknowledges that no physical evidence of physiological dysfunction has been found, which can be reassuring to the patient and family. The clinician then states that the patient’s condition and the physical manifestation of the symptoms are real. A patient’s or parent’s resistance to this reassurance may indicate that they have a large investment in the symptoms and perpetuating the dysfunction.

Taking a mind-body approach—explaining that the child’s condition is created and perpetuated by a mind-body connection and is not under their voluntary control—often is well received by patients and parents. The treating clinician emphasizes that the condition is physically disabling and that careful, appropriate, and intensive treatment is necessary.

A rehabilitation model has power for patients with conversion disorder because it acknowledges the patient’s discomfort and loss of function while shifting the focus away from finding what is wrong. The goal is to actively engage patients in their own care to help them return to normal functioning.6

Cassandra was encouraged to participate in physical therapy, go to school, and take care of herself. Actively participating in her care and recovery meant that Cassandra had to leave the sick role behind, which was impossible for her father, who saw her as passive, helpless, and fragile.

TREATMENT: Pharmacotherapy, CBT

During psychiatric evaluation, it becomes clear that in addition to her physical debility, Cassandra has major depressive disorder, moderate without psychotic features. Her depression contributes to her hopelessness and lack of participation in treatment. After discussion with her family about how her depressive symptoms are preventing her recovery, Cassandra is started on escitalopram, 10 mg/d. CBT helps her manage her depressive symptoms, prevent further somatization, and correct misperceptions about her body function and disabilities.

For conversion disorder patients, physical therapy can be combined with incentives tied to improvements in functioning. Cassandra has overwhelming anxiety while attempting physical therapy, which interferes with her participation in the therapy. Lorazepam, 0.5 mg/d, is prescribed for her intense anxiety and panic attacks, which led her to avoid physical therapy.

Staff at the rehabilitation hospital calls CPS because Cassandra’s father interferes with her care and treatment plan. CPS continues to monitor Cassandra’s progress through outpatient care. An individualized education plan and psychoeducational testing help determine a school placement to meet Cassandra’s educational needs.

CPS directs Cassandra to stay with her mother for alternating weeks. While at her mother’s, Cassandra is more interested in taking care of herself. She helps with getting herself into bed and to the toilet. Upon returning to her father’s home, these gains are lost.

The author’s observations

Psychodynamic and unconscious motivators for conversion disorder operate on a deeper, hidden level. The underlying primary conflict in pseudoseizures—a more common conversion disorder—has been described as an inability to express negative emotions such as anger. Social problems, conflict with parents, learning disorders,7 or sexual abuse8 produce the negative emotions caused by the primary conflict. Cassandra yearned for a closer relationship with her mother, yet she remained enmeshed with poor intrapsychic boundaries with her father. The fact that he assisted his 17-year-old daughter with toileting raised the possibility of sexual abuse. Sexual abuse could have led to her depression and physical decline. Cassandra’s physical debility also may have been her way to foster dependency on her father and protect him from perceived persecution.

Conversion disorder may have been a result of Cassandra’s defense mechanisms against admitting abuse and protecting against abandonment. Establishing a therapeutic alliance with Cassandra is essential to allow a graceful exit from the conversion disorder symptoms and her father’s hold on her thinking about her illness. However, this alliance may seem to threaten the child’s special connection with the parent. A therapeutic alliance was elusive in Cassandra’s case and likely nearly impossible.

Both parents underwent court-ordered psychological testing as part of the CPS evaluation. Testing on Cassandra’s father indicated a rigid personality structure with long-standing paranoia and mistrust of authority. Because Cassandra endorsed his delusional system completely, it is likely that her father inculcated her into believing his beliefs and transmitted his delusions to her by their close proximity and time together. Based upon this delusional belief system, Cassandra gave up trying to move her legs and her muscles atrophied. Her legs were so weak that she stopped trying to walk or move, illustrating the power of the mind-body connection to produce functional and physiological changes.