User login

Respondeat superior: What are your responsibilities?

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

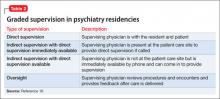

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman:

In my residency program, we cover the psychiatric emergency room (ER) overnight, and we admit, discharge, and make treatment recommendations without calling the attending psychiatrists about every decision. But if something goes wrong—eg, a discharged patient later commits suicide—I’ve heard that the faculty psychiatrist may be held liable despite never having met the patient. Should we awaken our attendings to discuss every major treatment decision?

Submitted by “Dr. R”

Postgraduate medical training programs in all specialties let interns and residents make judgments and decisions outside the direct supervision of board-certified faculty members. Medical education cannot occur unless doctors learn to take independent responsibility for patients. But if poor decisions by physicians-in-training lead to bad outcomes, might their teachers and training institutions share the blame—and the legal liability for damages?

The answer is “yes.” To understand why, and to learn about how Dr. R’s residency program should address this possibility, we’ll cover:

• the theory of respondeat superior

• factors affecting potential vicarious liability

• how postgraduate training balances supervision needs with letting residents get real-world treatment experience.

Vicarious liability

In general, if Person A injures Person B, Person B may initiate a tort action against Person A to seek monetary compensation. If the injury occurred while Person A was working for Person C, then under a legal doctrine called respondeat superior (Latin for “let the master answer”), courts may allow Person B to sue Person C, too, even if Person C wasn’t present when the injury occurred and did nothing that harmed Person B directly.

Respondeat superior imposes vicarious liability on an employer for negligent acts by employees who are “performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control.”1 The doctrine extends back to 17th-century English courts and originated under the theory that, during a servant’s employment, one may presume that the servant acted by his master’s authority.2

Modern authors state that the justification for imposing vicarious liability “is largely one of public or social policy under which it has been determined that, irrespective of fault, a party should be held to respond for the acts of another.”3 Employers usually have more resources to pay damages than their employees do,4 and “in hard fact, the reason for the employers’ liability is the damages are taken from a deep pocket.”5

Determining potential responsibility

In Dr. R’s scenario, an adverse event follows the actions of a psychiatry resident who is performing a training activity at a hospital ER. Whether an attorney acting on behalf of an injured client can bring a claim of respondeat superior against the hospital, the resident’s academic institution, or the attending psychiatrist will depend on the nature of the relationships among these parties. This often becomes a complex legal matter that involves examining the residency program’s educational arrangements, official training documents (eg, affiliation agreements between a university and a hospital), employment contracts, and supervisory policies. In addition, statutes and legal precedents governing vicarious liability vary from state to state. Although an initial malpractice filing may name several individuals and institutions as defendants, courts eventually must apply their jurisdictions’ rules governing vicarious liability to determine which parties can lawfully bear potential liability.

Some courts have held that a private hospital generally is not responsible for negligent actions by attending physicians because the hospital does not control patient care decisions and physicians are not the hospital’s employees.6-8 Physicians in training, however, usually are employees of hospitals or their training institutions. Residents and attending physicians in many psychiatry training programs work at hospitals where patients reasonably believe that the doctors function as part of the hospital’s larger service enterprise. In some jurisdictions, this makes the hospitals potentially liable for their doctors’ acts,9 even when the doctors, as public employees, may have statutory immunity from being sued as individuals.10

Reuter11 has suggested that other agency theories may allow a resident’s error to create liability for an attending physician or medical school. The resident may be viewed as a “borrowed servant” such that, although a hospital was the resident’s general employer, the attending physician still exercised sufficient control with respect to the faulty act in question. A medical school faculty physician also may be liable along with the hospital under a joint employment theory based upon the faculty member’s “right to control” how the resident cares for the attending’s patient.11

Taking into account recent cases and trends in public expectations, Kachalia and Studdert12 suggest that potential liability of attending physicians rests on 2 factors: whether the treatment context and structure of supervisory obligations establishes a patient-physician relationship between the attending physician and the injured patient, and whether the attending physician has provided adequate supervision. Details of these 2 factors appear in Table 1.12-14

Independence vs oversight

Potential malpractice liability is one of many factors that postgraduate psychiatry programs consider when titrating the amount and intensity of supervision against letting residents make independent decisions and take on clinical responsibility for patients. Patients deserve good care and protection from mistakes that inexperienced physicians may make. At the same time, society recognizes that educating future physicians requires allowing residents to get real-world experiences in evaluating and treating patients.

These ideas are expressed in the “Program Requirements” for psychiatry residencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).15 According to the ACGME, the “essential learning activity” that teaches physicians how to provide medical care is “interaction with patients under the guidance and supervision of faculty members” who let residents “exercise those skills with greater independence.”15

Psychiatry residencies must fashion learning experiences and supervisory schemes that give residents “graded and progressive responsibility” for providing care. Although each patient should have “an identifiable, appropriately-credentialed and privileged attending physician,” residents may provide substantial services under various levels of supervision described in Table 2.16

Deciding when and what kinds of patient care may be delegated to residents is the responsibility of residency program directors, who should base their judgments on explicit, prespecified criteria using information provided by supervising faculty members. Before letting first-year residents see patients on their own, psychiatry programs must determine that the residents can:

• take a history accurately

• do emergency psychiatric assessments

• present findings and data accurately to supervisors.

Physicians at all levels need to recognize when they should ask for help. The most important ACGME criterion for allowing a psychiatry resident to work under less stringent supervision is that the resident has demonstrated an “ability and willingness to ask for help when indicated.”16

Getting specifics

One way to respond Dr. R’s questions is to ask, “Do you know when you need help, and will you ask for it?” But her concerns deserve a more detailed (and more thoughtful) response that inquires about details of her training program and its specific educational experiences. Although it would be impossible to list everything to consider, some possible topics include:

• At what level of experience and training do residents assume this coverage responsibility?

• What kind of preparation do residents receive?

• What range of problems and conditions do the patients present?

• What level of clinical support is available on site—eg, experienced psychiatric nurses, other mental health staff, or other medical specialists?

• What has the program’s experience shown about residents’ actual readiness to handle these coverage duties?

• What guidelines have faculty members provided about when to call an attending physician or request a faculty member’s presence? Do these guidelines seem sound, given the above considerations?

Bottom Line

Psychiatry residents have supervisee relationships that create potential vicarious liability for institutions and faculty members. Residency training programs address these concerns by implementing adequate preparation for advanced responsibility, developing evaluative criteria and supervisory guidelines, and making sure that residents will ask for help when they need it.

Related Resources

- Regan JJ, Regan WM. Medical malpractice and respondeat superior. South Med J. 2002;95(5):545-548.

- Winrow B, Winrow AR. Personal protection: vicarious liability as applied to the various business structures. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53(2):146-149.

- Pozgar GD. Legal aspects of health care administration. 11th edition. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC; 2012.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Restatement of the law of agency. 3rd ed. §7.07(2). Philadelphia, PA: American Law Institute; 2006.

2. Baty T. Vicarious liability: a short history of the liability of employers, principals, partners, associations and trade-union members. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1916.

3. Dessauer v Memorial General Hosp, 628 P.2d 337 (N.M. 1981).

4. Firestone MH. Agency. In: Sandbar SS, Firestone MH, eds. Legal medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:43-47.

5. Dobbs D, Keeton RE, Owen DG. Prosser and Keaton on torts. 5th ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co; 1984.

6. Austin v Litvak, 682 P.2d 41 (Colo. 1984).

7. Kirk v Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, 513 N.E.2d 387 (Ill. 1987).

8. Gregg v National Medical Health Care Services, Inc., 499 P.2d 925 (Ariz. App. 1985).

9. Adamski v Tacoma General Hospital, 579 P.2d 970 (Wash. App. 1978).

10. Johnson v LeBonheur Children’s Medical Center, 74 S.W.3d 338 (Tenn. 2002).

11. Reuter SR. Professional liability in postgraduate medical education. Who is liable for resident negligence? J Leg Med. 1994;15(4):485-531.

12. Kachalia A, Studdert DM. Professional liability issues in graduate medical education. JAMA. 2004;292(9):1051-1056.

13. Lownsbury v VanBuren, 762 N.E.2d 354 (Ohio 2002).

14. Sterling v Johns Hopkins Hospital, 802 A.2d 440 (Md Ct Spec App 2002).

15. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Program and institutional guidelines. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/tabid/147/ProgramandInstitutional Guidelines/MedicalAccreditation/Psychiatry.aspx. Accessed April 8, 2013.

16. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in psychiatry. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/400_psychiatry_07012007_u04122008.pdf. Published July 1, 2007. Accessed April 8, 2013.

STOP performing dilation and curettage for the evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

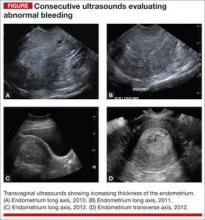

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

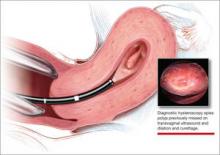

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

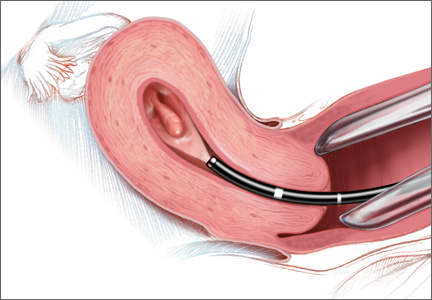

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

CASE: In-office hysteroscopy spies previously missed polyp

A 51-year-old woman with a history of breast cancer completed 5 years of tamoxifen. During her treatment she had a 3-year history of abnormal vaginal bleeding. Results from consecutive pelvic ultrasounds indicated that the patient had progressively thickening endometrium (from 1.4 cm to 2.5 cm to 4.7 cm). In-office biopsy was negative for endometrial pathology. An ultimate dilation and curettage (D&C) was performed with negative histologic diagnosis. The patient is seen in consultation, and the ultrasound images are reviewed (FIGURE).

These images show an increasing thickness of the ednometrium with definitive intracavitary pathology that was missed with the prevous clinical evaluation with enodmetrial biopsy and D&C. An in-office hysteroscopy is performed, and a large 5 x 4 x 7 cm cystic and fibrous polyp is identified with normal endometrium (VIDEO 1).

Hysteroscopy reveals massive polyp extending into a dilated lower uterine segment

Abnormal uterine bleeding

The evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding. (AUB), as described in this clinical scenario, is quite common. As a consequence, many patients have a missed or inaccurate diagnosis and undergo unnecessary invasive procedures under general anesthesia.

AUB is one of the primary indications for a gynecologic consultation, accounting for approximately 33% of all gynecology visits, and for 69% of visits among postmenopausal women.1 Confirming the etiology and planning appropriate intervention is important in the clinical management of AUB because accurate diagnosis may result in avoiding major gynecologic surgery in favor of minimally invasive hysteroscopic management.

Diagnostic hysteroscopy is proven in AUB evaluation

Drawbacks of other diagnostic tools. It is generally accepted that the initial evaluation of women with AUB is performed with noninvasive transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS).1-3 As illustrated by the opening case, however, the accuracy of TVUS is limited in the diagnosis of focal endometrial lesions, and further investigation of the uterine cavity is warranted.

Evaluation of the uterine cavity with sonohysterography (SH)—vaginal ultrasound with the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity—is more accurate than TVUS alone. Yet, diagnostic hysteroscopy (DH) has proven to be superior to either modality for the accurate evaluation of intracavitary pathology.1-3

Evidence of DH superiority. Farquhar and colleagues reported results of a systematic review of studies published from 1980 to July 2001 that examined TVUS versus SH and DH for the investigation of AUB in premenopausal women. The researchers found that TVUS had a higher rate of false negatives for detecting intrauterine pathology, compared with SH and DH. They also found that DH was superior to SH in diagnosing submucous myomas.2

In 2010, results of a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH for detecting endometrial pathology, showed that DH had a significantly better diagnostic performance than SH and TVUS and that hysteroscopy was significantly more precise in the diagnosis of intracavitary masses.3

Again, in 2012, a prospective comparison of TVUS, SH, and DH in the diagnosis of AUB revealed that hysteroscopy provided the most accurate diagnosis.1

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, van Dongen found the accuracy of DH to be estimated at 96.9%.4

Hysteroscopy is also considered to be more comfortable for patients than SH.2

blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

A procedure performed “blind” limits its usefulness in AUB evaluation

This statement is not a new realization. As far back as 1989, Loffer showed that blind D&C was less accurate for diagnosing AUB than was hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy. The sensitivity of diagnosing the etiology of AUB with D&C was 65%, compared to a sensitivity of 98% with hysteroscopy with directed biopsy. Hysteroscopy was shown to be better because blinded sampling missed intracavitary lesions such as polyps and myomas that accounted for bleeding abnormalities.5

The limitations of D&C are evident in the opening case, as the D&C performed in the operating room under general anesthesia, without visualization of the uterine cavity, failed to identify the patient’s intrauterine pathology. D&C is seldom necessary to evaluate AUB and has significant surgical risks beyond general anesthesia, including cervical or uterine trauma that can occur with cervical dilation and instrumentation of the uterus.

As with D&C, endometrial biopsy has limitations in diagnosing abnormalities within the uterine cavity. In a 2008 prospective comparative study of hysteroscopy versus blind biopsy with a suction biopsy curette, Angioni and colleagues showed a significant difference in the capability of these two procedures to accurately diagnose the etiology of bleeding for menopausal women. Blinded biopsy had a sensitivity for diagnosing polyps, myomas, and hyperplasia of 11%, 13%, and 25%, respectively. The sensitivity of hysteroscopy to diagnose the same intracavitary pathology was 89%, 100%, and 74%, respectively.6

This does not mean, however, that the endometrial biopsy is not beneficial in the evaluation of AUB. Several authors recommend that in a clinically relevant situation, endometrial biopsy with a small suction curette should be performed concomitantly with hysteroscopy to improve the sensitivity of the overall evaluation with histology.7,8 And, as Loffer showed, the hysteroscopic evaluation with a visually directed biopsy is extremely accurate (VIDEO 2, VIDEO 3).5

The bottom line for D&C use in AUB evaluation

Sometimes a D&C is needed. For instance, when more tissue is needed for histologic evaluation than can be obtained with small suction curette at endometrial biopsy. However, there are several shortcomings of D&C for the evaluation of AUB:

- Most clinicians perform D&C in the operating room under general anesthesia.

- It is often done without concomitant hysteroscopy.

- There is significant potential to miss pathology, such as polyps or myomas.

- There is risk of uterine perforation with cervical dilation and uterine instrumentation.

- Hysteroscopy with visually directed biopsy provides a method that offers a more accurate diagnosis, and the procedure can be performed in the office.

In-office AUB evaluation using hysteroscopy is possible and advantageous

Hysteroscopy not only has increased accuracy for identifying the etiology of AUB, compared with D&C, but also offers the possibility of in-office use. Newer hysteroscopes with small diameters and decreasing costs of hysteroscopic equipment allow gynecologists to perform hysteroscopy economically and safely in the office.

Office evaluation of the uterine cavity and preoperative decision-making before a patient is taken to the operating room (OR) improve the likelihood that the appropriate procedure will be performed. They also provide an opportunity for the patient to see inside her own uterine cavity and for the surgeon to discuss management options with her (VIDEO 4: Diagnostic hysteroscopy with fundal myoma, VIDEO 5: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with atypical hyperplasia, VIDEO 6: Diagnostic hysteroscopy in a menopausal patient with polyps). If pathology is noted, there is a potential to treat abnormalities such as endometrial polyps at the same time, thus avoiding the OR altogether (VIDEO 7).

The small diameter of the hysteroscope allows evaluation in most menopausal and nulliparous patients comfortably without first having to dilate or soften the cervix. Paracervical placement of local anesthetic can be used as needed for patient comfort (VIDEO 8).9 A vaginoscopic approach will eliminate the discomfort of having to place a speculum (VIDEO 9).

It offers:

- a familiar and comfortable environment for the procedure

- saved time for patient and physician

- saved money for the patient with a large deductible or coinsurance

- no requirement for general anesthesia

- local anesthesia can be used but is not necessary

- immediate visual affirmation for the patient and physician

- a see and treat possibility

- possibility of preoperative decision-making

- saved trip to the OR if significant precancer or cancer is identified

- use in menopausal and nulliparous patients with no cervical preparation necessary when a small-diameter hysteroscope or flexible hysteroscope is used

- minimized discomfort from a speculum with the vaginoscopic approach for awake patients

- possibility of cervical access when needed (VIDEO 10).

My clinical recommendation

Use office hysteroscopy with endometrial biopsy as needed with the opportunity to perform a directed biopsy.

Coding for in-office hysteroscopy

Some procedures now can be performed in the office setting. Among these is operative hysteroscopy, for things such as abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), foreign body removal, and tubal occlusion. When performing hysteroscopic evaluation of AUB, the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 58558 (Hysteroscopy, surgical; with sampling (biopsy) of endometrium and/or polypectomy, with or without D&C) should be reported. This code is reported whether polyp(s) are removed or a sampling of the uterine lining or a full D&C is performed.

Under the Resource-Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), used by the majority of payers for reimbursement, there is a payment differential for site of service. In other words, when performed in the office setting, reimbursement will be higher than in the hospital setting to offset the increased practice expenses incurred. In the office setting, 58558 has 11.93 relative value units. In comparison, a D&C performed without hysteroscopy has 7.75 relative value units in the office setting. Keep in mind, however, that all supplies used in performing this procedure are included in the reimbursement amount.

Some payers will reimburse separately for administering a regional anesthetic, but a local anesthetic is considered integral to the procedure. Under CPT rules, you may bill separately for regional anesthesia. When performing office hysteroscopy, the most common regional anesthesia would be a paracervical nerve block (CPT code 66435—Injection, anesthetic agent; paracervical [uterine] nerve). Under CPT rules, coding should go in as 58558-47, 64435-51. The modifier -47 lets the payer know that the physician performed the regional block, and the modifier -51 identifies the regional block as a multiple procedure.

Medicare, however, will never reimburse separately for regional anesthesia performed by the operating physician, and because of this, Medicare’s Correct Coding Initiative (CCI) permanently bundles 64435 when billed with 58558. Medicare will not permit a modifier to be used to bypass this bundling edit, and separate payment is never allowed. If your payer has adopted this Medicare policy, separate payment will also not be made.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

- Soguktas S, Cogendez E, Kayatas SE, Asoglu MR, Selcuk S, Ertekin A. Comparison of saline infusion sonohysterography and hysteroscopy in diagnosis of premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Repro Biol. 2012;161(1):66−70.

- Farquhar C, Ekeroma A, Furness S, Arroll B. A systematic review of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography and hysteroscopy for the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(6):493–504.

- Grimbizis GF, Tsolakidis D, Mikos T, et al. A prospective comparison of transvaginal ultrasound, saline infusion sonohysterography, and diagnostic hysteroscopy in the evaluation of endometrial pathology. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(7):2721−2725.

- van Dongen H, de Kroon CD, Jacobi CE, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Diagnostic hysteroscopy in abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2007;114(6):664–75.

- Loffer FD. Hysteroscopy with selective endometrial sampling compared with D & C for abnormal uterine bleeding: the value of a negative hysteroscopic view. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73(1):16–20.

- Angioni S, Loddo A, Milano F, Piras B, Minerba L, Melis GB. Detection of benign intracavitary lesions in postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding: a prospective comparative study on outpatient hysteroscopy and blind biopsy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):87–91.

- Lo KY, Yuen PM. The role of outpatient diagnostic hysteroscopy in identifying anatomic pathology and histopathology in the endometrial cavity. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7(3):381–385.

- Garuti G, Sambruni I, Colonneli M, Luerti M. Accuracy of hysteroscopy in predicting histopathology of endometrium in 1500 women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(2):207–213.

- Munro MG, Brooks PG. Use of local anesthesia for office diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(6):709–718.

Is Shared Decision-Making Bad for the Bottom Line?

A new study shows that hospitalized patients who were more engaged in their own care produced higher costs and longer lengths of stay (LOS).

The report, "Association of Patient Preferences for Participation in Decision Making With Length of Stay and Costs Among Hospitalized Patients," published in JAMA Internal Medicine, used a survey of 21,754 patients in one academic setting to determine their preferences on shared decision-making. The information was later linked to administrative data.

Patients who said they preferred to participate in decision-making with their physicians had a 0.26-day (95% CI, 0.06-0.47 day) longer LOS (P=0.01) and incurred an average of $865 (95% CI, $155-$1,575) in higher total hospitalization costs (P=0.02). Patients with higher education levels and private health insurance were more likely than others to want to participate in decision-making with doctors, the authors noted.

Lead author Hyo Jung Tak, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Chicago says that while the results don't mean that patient-centered care directly drives up costs, it is important not to accept at face value that engaged patients lead to reduced health-care-delivery costs.

“These days,” she adds, “many researchers and policymakers expect that patient-centered care could help to reduce medical utilization as it could prevent costly interventions that patients may not want, but I think people should be more careful in terms of how it really applies in the clinical setting.”

Dr. Tak cautions that many variables could affect how a similar study would work at other hospitals, including an institution’s payor mix and the socioeconomic status of its service area. She said a potentially larger issue is why some patients strongly disagree with the idea of leaving medical decisions up to their physicians.

“If we can find that answer, that could help to improve patient-centered care in the future,” Dr. Tak adds. “That could be the ultimate question in this study.”

Visit our website for more information on patient-centered care.

A new study shows that hospitalized patients who were more engaged in their own care produced higher costs and longer lengths of stay (LOS).

The report, "Association of Patient Preferences for Participation in Decision Making With Length of Stay and Costs Among Hospitalized Patients," published in JAMA Internal Medicine, used a survey of 21,754 patients in one academic setting to determine their preferences on shared decision-making. The information was later linked to administrative data.

Patients who said they preferred to participate in decision-making with their physicians had a 0.26-day (95% CI, 0.06-0.47 day) longer LOS (P=0.01) and incurred an average of $865 (95% CI, $155-$1,575) in higher total hospitalization costs (P=0.02). Patients with higher education levels and private health insurance were more likely than others to want to participate in decision-making with doctors, the authors noted.

Lead author Hyo Jung Tak, PhD, of the department of medicine at the University of Chicago says that while the results don't mean that patient-centered care directly drives up costs, it is important not to accept at face value that engaged patients lead to reduced health-care-delivery costs.

“These days,” she adds, “many researchers and policymakers expect that patient-centered care could help to reduce medical utilization as it could prevent costly interventions that patients may not want, but I think people should be more careful in terms of how it really applies in the clinical setting.”

Dr. Tak cautions that many variables could affect how a similar study would work at other hospitals, including an institution’s payor mix and the socioeconomic status of its service area. She said a potentially larger issue is why some patients strongly disagree with the idea of leaving medical decisions up to their physicians.