User login

Tackling a Delicate Subject With Heart Failure Patients

New and Noteworthy Information—January

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) disease activity have a higher rate of thinning of the ganglion cell/inner plexiform (GCIP) layer of the eye, researchers reported in the January 1 Neurology. Annual rates of GCIP thinning may be highest among patients with new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, new T2 lesions, and disease duration of less than five years. The investigators performed spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scans every six months on 164 patients with MS and 59 healthy controls. The mean follow-up time was 21.1 months. Annual GCIP thinning occurred 42% faster in patients with relapses, 54% faster in patients with new gadolinium-enhanced lesions, and 36% faster in patients with new T2 lesions.

Vaccination with a monovalent AS03 adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of epileptic seizures, according to research published in the December 28, 2012, BMJ. Researchers studied 373,398 people with and without epilepsy who had received the vaccine. The primary end point was admission to a hospital or outpatient hospital care with epileptic seizures. The investigators found no increased risk of seizures in patients with epilepsy and a nonsignificantly decreased risk of seizures in persons without epilepsy during the initial seven-day risk period. During the subsequent 23-day risk period, people without epilepsy had a nonsignificantly increased risk of seizures, but patients with epilepsy had no increase in risk of seizures.

Variations in some genes associated with risk for psychiatric disorders may be observed as differences in brain structure in neonates, according to a study published in the January 2 online Cerebral Cortex. Investigators performed automated region-of-interest volumetry and tensor-based morphometry on 272 newborns who had had high-resolution MRI scans. The group found that estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799) predicted intracranial volume. Polymorphisms in estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799), as well as in disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1, rs821616), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), neuregulin 1, apolipoprotein E, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, were significantly associated with local variation in gray matter volume. “The results highlight the importance of prenatal brain development in mediating psychiatric risk,” noted the authors.

Four months after mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), white matter abnormalities may persist in children, even if cognitive symptoms have resolved, according to research published in the December 12, 2012, Journal of Neuroscience. The magnitude and duration of these abnormalities also appear to be greater in children with mild TBI than in adults with mild TBI. Researchers performed fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity on 15 children with semiacute mild TBI and 15 matched controls. Post-TBI cognitive dysfunction was observed in the domains of attention and processing speed. Increased anisotropy identified patients with pediatric mild TBI with 90% accuracy but was not associated with neuropsychologic deficits. Anisotropic diffusion may provide an objective biomarker of pediatric mild TBI.

The FDA has approved Eliquis (apixaban) for reducing the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. In a phase III clinical trial, Eliquis, an oral anticoagulant, reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism by 21%, compared with warfarin. The drug primarily reduced the risk of hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke that converted to hemorrhagic stroke, and it also decreased the risks of major bleeding and all-cause mortality, compared with warfarin. Eliquis inhibits Factor Xa, a blood-clotting protein, thus decreasing thrombin generation and blood clots. The recommended dose is 5 mg twice daily. For patients age 80 or older and those who weigh 60 kg or less, the recommended dose is 2.5 mg twice daily. Eliquis is manufactured by Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York City) and comarketed with Pfizer (New York City).

Intermittent fasting, together with a ketogenic diet, may reduce seizures in children with epilepsy to a greater extent than the ketogenic diet alone, investigators reported in the November 30, 2012, online Epilepsy Research. The researchers placed six children with an incomplete response to a ketogenic diet on an intermittent fasting regimen. The children, ages 2 to 7, fasted on alternate days. Four children had transient improvement in seizure control, but they also had hunger-related adverse reactions. Three patients adhered to the combined intermittent fasting and ketogenic diet regimen for two months. The ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting may not share the same anticonvulsant mechanisms, noted the authors.

The available evidence does not support the use of cannabis extract to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a review published in the December 2012 Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Researchers concluded that the trial data for nabiximols, a mouth spray for patients with MS containing dronabinol and cannabidiol, were limited. In the trials, which were the basis for the drug’s approval, symptoms decreased in a slightly higher number of patients taking nabiximols, compared with patients taking placebo. The drug was used for relatively short periods (ie, six weeks to four months) in many of these studies, however, and no study compared nabiximols with another active ingredient. One properly designed trial with a sufficient number of patients showed no difference in symptom relief between participants who took nabiximols and those who did not.

Baseline depression was associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia in individuals 65 or older, researchers reported in the December 31, 2012, Archives of Neurology. Depression may coincide with cognitive impairment, but may not precede it, the study authors noted. The investigators studied 2,160 community-dwelling Medicare recipients in New York City. The team defined depression as a score of 4 or more on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale. MCI, dementia, and progression from MCI to dementia were the study’s main outcome measures. Baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of incident dementia, but not with incident MCI. Participants with MCI and comorbid depression at baseline had a higher risk of progression to dementia, but not Alzheimer’s disease.

Consumption of fructose resulted in a smaller increase in systemic glucose, insulin, and glucagon-like polypeptide 1 levels than consumption of glucose, according to research published in the January 2 JAMA. Glucose ingestion was associated with a significantly greater reduction in hypothalamic cerebral blood flow than fructose ingestion. Researchers performed MRIs of 20 healthy adults at baseline and after ingestion of a glucose or fructose drink. The blinded study had a random-order crossover design. Compared with baseline, glucose ingestion increased functional connectivity between the hypothalamus and the thalamus and striatum. Fructose increased connectivity between the hypothalamus and thalamus, but not the striatum. Fructose reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the thalamus, hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, fusiform, and visual cortex.

Research published in the January 7 online Epilepsia provides evidence for a shared genetic susceptibility to epilespsy and migraine with aura. Compared with migraine without aura, the prevalence of migraine with aura was significantly increased among patients with epilepsy who have two or more first-degree relatives with epilepsy. Investigators studied the prevalence of a history of migraine in 730 participants in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project. Eligible participants were 12 or older, had nonacquired focal epilepsy or generalized epilepsy, and had one or more relative epilepsy of unknown cause. The researchers collected information on migraine with and without aura using an instrument validated for individuals 12 and older. The team also interviewed participants about the history of seizure disorders in nonenrolled family members.

Higher exposure to benomyl is associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease, according to an epidemiologic study published in the December 24, 2012, online Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In primary mesencephalic neurons, benomyl exposure inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and alters dopamine homeostasis. Investigators tested the effects of benomyl in cell cultures and confirmed that the chemical damaged or destroyed dopaminergic neurons. The researchers also found that benomyl caused the loss of dopaminergic neurons in zebrafish. The ALDH model for Parkinson’s disease etiology may help explain the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons and describe the mechanism through which environmental toxicants contribute to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis, the authors theorized.

Patients with a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and loss of consciousness may have an increased risk for future TBI and loss of consciousness, according to a study published in the November 21, 2012, online Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. Researchers are conducting an ongoing study of 4,225 nondemented adults age 65 and older. Participants are seen every two years, and 14% have reported a lifetime history of TBI and loss of consciousness. Individuals reporting a first injury before age 25 had an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.54 for TBI and loss of consciousness, compared with a hazard ratio of 3.79 for adults with first injury after age 55.

—Erik Greb

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) disease activity have a higher rate of thinning of the ganglion cell/inner plexiform (GCIP) layer of the eye, researchers reported in the January 1 Neurology. Annual rates of GCIP thinning may be highest among patients with new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, new T2 lesions, and disease duration of less than five years. The investigators performed spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scans every six months on 164 patients with MS and 59 healthy controls. The mean follow-up time was 21.1 months. Annual GCIP thinning occurred 42% faster in patients with relapses, 54% faster in patients with new gadolinium-enhanced lesions, and 36% faster in patients with new T2 lesions.

Vaccination with a monovalent AS03 adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of epileptic seizures, according to research published in the December 28, 2012, BMJ. Researchers studied 373,398 people with and without epilepsy who had received the vaccine. The primary end point was admission to a hospital or outpatient hospital care with epileptic seizures. The investigators found no increased risk of seizures in patients with epilepsy and a nonsignificantly decreased risk of seizures in persons without epilepsy during the initial seven-day risk period. During the subsequent 23-day risk period, people without epilepsy had a nonsignificantly increased risk of seizures, but patients with epilepsy had no increase in risk of seizures.

Variations in some genes associated with risk for psychiatric disorders may be observed as differences in brain structure in neonates, according to a study published in the January 2 online Cerebral Cortex. Investigators performed automated region-of-interest volumetry and tensor-based morphometry on 272 newborns who had had high-resolution MRI scans. The group found that estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799) predicted intracranial volume. Polymorphisms in estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799), as well as in disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1, rs821616), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), neuregulin 1, apolipoprotein E, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, were significantly associated with local variation in gray matter volume. “The results highlight the importance of prenatal brain development in mediating psychiatric risk,” noted the authors.

Four months after mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), white matter abnormalities may persist in children, even if cognitive symptoms have resolved, according to research published in the December 12, 2012, Journal of Neuroscience. The magnitude and duration of these abnormalities also appear to be greater in children with mild TBI than in adults with mild TBI. Researchers performed fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity on 15 children with semiacute mild TBI and 15 matched controls. Post-TBI cognitive dysfunction was observed in the domains of attention and processing speed. Increased anisotropy identified patients with pediatric mild TBI with 90% accuracy but was not associated with neuropsychologic deficits. Anisotropic diffusion may provide an objective biomarker of pediatric mild TBI.

The FDA has approved Eliquis (apixaban) for reducing the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. In a phase III clinical trial, Eliquis, an oral anticoagulant, reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism by 21%, compared with warfarin. The drug primarily reduced the risk of hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke that converted to hemorrhagic stroke, and it also decreased the risks of major bleeding and all-cause mortality, compared with warfarin. Eliquis inhibits Factor Xa, a blood-clotting protein, thus decreasing thrombin generation and blood clots. The recommended dose is 5 mg twice daily. For patients age 80 or older and those who weigh 60 kg or less, the recommended dose is 2.5 mg twice daily. Eliquis is manufactured by Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York City) and comarketed with Pfizer (New York City).

Intermittent fasting, together with a ketogenic diet, may reduce seizures in children with epilepsy to a greater extent than the ketogenic diet alone, investigators reported in the November 30, 2012, online Epilepsy Research. The researchers placed six children with an incomplete response to a ketogenic diet on an intermittent fasting regimen. The children, ages 2 to 7, fasted on alternate days. Four children had transient improvement in seizure control, but they also had hunger-related adverse reactions. Three patients adhered to the combined intermittent fasting and ketogenic diet regimen for two months. The ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting may not share the same anticonvulsant mechanisms, noted the authors.

The available evidence does not support the use of cannabis extract to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a review published in the December 2012 Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Researchers concluded that the trial data for nabiximols, a mouth spray for patients with MS containing dronabinol and cannabidiol, were limited. In the trials, which were the basis for the drug’s approval, symptoms decreased in a slightly higher number of patients taking nabiximols, compared with patients taking placebo. The drug was used for relatively short periods (ie, six weeks to four months) in many of these studies, however, and no study compared nabiximols with another active ingredient. One properly designed trial with a sufficient number of patients showed no difference in symptom relief between participants who took nabiximols and those who did not.

Baseline depression was associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia in individuals 65 or older, researchers reported in the December 31, 2012, Archives of Neurology. Depression may coincide with cognitive impairment, but may not precede it, the study authors noted. The investigators studied 2,160 community-dwelling Medicare recipients in New York City. The team defined depression as a score of 4 or more on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale. MCI, dementia, and progression from MCI to dementia were the study’s main outcome measures. Baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of incident dementia, but not with incident MCI. Participants with MCI and comorbid depression at baseline had a higher risk of progression to dementia, but not Alzheimer’s disease.

Consumption of fructose resulted in a smaller increase in systemic glucose, insulin, and glucagon-like polypeptide 1 levels than consumption of glucose, according to research published in the January 2 JAMA. Glucose ingestion was associated with a significantly greater reduction in hypothalamic cerebral blood flow than fructose ingestion. Researchers performed MRIs of 20 healthy adults at baseline and after ingestion of a glucose or fructose drink. The blinded study had a random-order crossover design. Compared with baseline, glucose ingestion increased functional connectivity between the hypothalamus and the thalamus and striatum. Fructose increased connectivity between the hypothalamus and thalamus, but not the striatum. Fructose reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the thalamus, hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, fusiform, and visual cortex.

Research published in the January 7 online Epilepsia provides evidence for a shared genetic susceptibility to epilespsy and migraine with aura. Compared with migraine without aura, the prevalence of migraine with aura was significantly increased among patients with epilepsy who have two or more first-degree relatives with epilepsy. Investigators studied the prevalence of a history of migraine in 730 participants in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project. Eligible participants were 12 or older, had nonacquired focal epilepsy or generalized epilepsy, and had one or more relative epilepsy of unknown cause. The researchers collected information on migraine with and without aura using an instrument validated for individuals 12 and older. The team also interviewed participants about the history of seizure disorders in nonenrolled family members.

Higher exposure to benomyl is associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease, according to an epidemiologic study published in the December 24, 2012, online Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In primary mesencephalic neurons, benomyl exposure inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and alters dopamine homeostasis. Investigators tested the effects of benomyl in cell cultures and confirmed that the chemical damaged or destroyed dopaminergic neurons. The researchers also found that benomyl caused the loss of dopaminergic neurons in zebrafish. The ALDH model for Parkinson’s disease etiology may help explain the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons and describe the mechanism through which environmental toxicants contribute to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis, the authors theorized.

Patients with a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and loss of consciousness may have an increased risk for future TBI and loss of consciousness, according to a study published in the November 21, 2012, online Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. Researchers are conducting an ongoing study of 4,225 nondemented adults age 65 and older. Participants are seen every two years, and 14% have reported a lifetime history of TBI and loss of consciousness. Individuals reporting a first injury before age 25 had an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.54 for TBI and loss of consciousness, compared with a hazard ratio of 3.79 for adults with first injury after age 55.

—Erik Greb

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) disease activity have a higher rate of thinning of the ganglion cell/inner plexiform (GCIP) layer of the eye, researchers reported in the January 1 Neurology. Annual rates of GCIP thinning may be highest among patients with new gadolinium-enhancing lesions, new T2 lesions, and disease duration of less than five years. The investigators performed spectral-domain optical coherence tomography scans every six months on 164 patients with MS and 59 healthy controls. The mean follow-up time was 21.1 months. Annual GCIP thinning occurred 42% faster in patients with relapses, 54% faster in patients with new gadolinium-enhanced lesions, and 36% faster in patients with new T2 lesions.

Vaccination with a monovalent AS03 adjuvanted pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza vaccine does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of epileptic seizures, according to research published in the December 28, 2012, BMJ. Researchers studied 373,398 people with and without epilepsy who had received the vaccine. The primary end point was admission to a hospital or outpatient hospital care with epileptic seizures. The investigators found no increased risk of seizures in patients with epilepsy and a nonsignificantly decreased risk of seizures in persons without epilepsy during the initial seven-day risk period. During the subsequent 23-day risk period, people without epilepsy had a nonsignificantly increased risk of seizures, but patients with epilepsy had no increase in risk of seizures.

Variations in some genes associated with risk for psychiatric disorders may be observed as differences in brain structure in neonates, according to a study published in the January 2 online Cerebral Cortex. Investigators performed automated region-of-interest volumetry and tensor-based morphometry on 272 newborns who had had high-resolution MRI scans. The group found that estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799) predicted intracranial volume. Polymorphisms in estrogen receptor alpha (rs9340799), as well as in disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1, rs821616), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), neuregulin 1, apolipoprotein E, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, were significantly associated with local variation in gray matter volume. “The results highlight the importance of prenatal brain development in mediating psychiatric risk,” noted the authors.

Four months after mild traumatic brain injury (TBI), white matter abnormalities may persist in children, even if cognitive symptoms have resolved, according to research published in the December 12, 2012, Journal of Neuroscience. The magnitude and duration of these abnormalities also appear to be greater in children with mild TBI than in adults with mild TBI. Researchers performed fractional anisotropy, axial diffusivity, and radial diffusivity on 15 children with semiacute mild TBI and 15 matched controls. Post-TBI cognitive dysfunction was observed in the domains of attention and processing speed. Increased anisotropy identified patients with pediatric mild TBI with 90% accuracy but was not associated with neuropsychologic deficits. Anisotropic diffusion may provide an objective biomarker of pediatric mild TBI.

The FDA has approved Eliquis (apixaban) for reducing the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. In a phase III clinical trial, Eliquis, an oral anticoagulant, reduced the risk of stroke or systemic embolism by 21%, compared with warfarin. The drug primarily reduced the risk of hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic stroke that converted to hemorrhagic stroke, and it also decreased the risks of major bleeding and all-cause mortality, compared with warfarin. Eliquis inhibits Factor Xa, a blood-clotting protein, thus decreasing thrombin generation and blood clots. The recommended dose is 5 mg twice daily. For patients age 80 or older and those who weigh 60 kg or less, the recommended dose is 2.5 mg twice daily. Eliquis is manufactured by Bristol-Myers Squibb (New York City) and comarketed with Pfizer (New York City).

Intermittent fasting, together with a ketogenic diet, may reduce seizures in children with epilepsy to a greater extent than the ketogenic diet alone, investigators reported in the November 30, 2012, online Epilepsy Research. The researchers placed six children with an incomplete response to a ketogenic diet on an intermittent fasting regimen. The children, ages 2 to 7, fasted on alternate days. Four children had transient improvement in seizure control, but they also had hunger-related adverse reactions. Three patients adhered to the combined intermittent fasting and ketogenic diet regimen for two months. The ketogenic diet and intermittent fasting may not share the same anticonvulsant mechanisms, noted the authors.

The available evidence does not support the use of cannabis extract to treat multiple sclerosis (MS), according to a review published in the December 2012 Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin. Researchers concluded that the trial data for nabiximols, a mouth spray for patients with MS containing dronabinol and cannabidiol, were limited. In the trials, which were the basis for the drug’s approval, symptoms decreased in a slightly higher number of patients taking nabiximols, compared with patients taking placebo. The drug was used for relatively short periods (ie, six weeks to four months) in many of these studies, however, and no study compared nabiximols with another active ingredient. One properly designed trial with a sufficient number of patients showed no difference in symptom relief between participants who took nabiximols and those who did not.

Baseline depression was associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia in individuals 65 or older, researchers reported in the December 31, 2012, Archives of Neurology. Depression may coincide with cognitive impairment, but may not precede it, the study authors noted. The investigators studied 2,160 community-dwelling Medicare recipients in New York City. The team defined depression as a score of 4 or more on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale. MCI, dementia, and progression from MCI to dementia were the study’s main outcome measures. Baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of incident dementia, but not with incident MCI. Participants with MCI and comorbid depression at baseline had a higher risk of progression to dementia, but not Alzheimer’s disease.

Consumption of fructose resulted in a smaller increase in systemic glucose, insulin, and glucagon-like polypeptide 1 levels than consumption of glucose, according to research published in the January 2 JAMA. Glucose ingestion was associated with a significantly greater reduction in hypothalamic cerebral blood flow than fructose ingestion. Researchers performed MRIs of 20 healthy adults at baseline and after ingestion of a glucose or fructose drink. The blinded study had a random-order crossover design. Compared with baseline, glucose ingestion increased functional connectivity between the hypothalamus and the thalamus and striatum. Fructose increased connectivity between the hypothalamus and thalamus, but not the striatum. Fructose reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the thalamus, hippocampus, posterior cingulate cortex, fusiform, and visual cortex.

Research published in the January 7 online Epilepsia provides evidence for a shared genetic susceptibility to epilespsy and migraine with aura. Compared with migraine without aura, the prevalence of migraine with aura was significantly increased among patients with epilepsy who have two or more first-degree relatives with epilepsy. Investigators studied the prevalence of a history of migraine in 730 participants in the Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project. Eligible participants were 12 or older, had nonacquired focal epilepsy or generalized epilepsy, and had one or more relative epilepsy of unknown cause. The researchers collected information on migraine with and without aura using an instrument validated for individuals 12 and older. The team also interviewed participants about the history of seizure disorders in nonenrolled family members.

Higher exposure to benomyl is associated with an increased risk for Parkinson’s disease, according to an epidemiologic study published in the December 24, 2012, online Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In primary mesencephalic neurons, benomyl exposure inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and alters dopamine homeostasis. Investigators tested the effects of benomyl in cell cultures and confirmed that the chemical damaged or destroyed dopaminergic neurons. The researchers also found that benomyl caused the loss of dopaminergic neurons in zebrafish. The ALDH model for Parkinson’s disease etiology may help explain the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons and describe the mechanism through which environmental toxicants contribute to Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis, the authors theorized.

Patients with a history of traumatic brain injury (TBI) and loss of consciousness may have an increased risk for future TBI and loss of consciousness, according to a study published in the November 21, 2012, online Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. Researchers are conducting an ongoing study of 4,225 nondemented adults age 65 and older. Participants are seen every two years, and 14% have reported a lifetime history of TBI and loss of consciousness. Individuals reporting a first injury before age 25 had an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.54 for TBI and loss of consciousness, compared with a hazard ratio of 3.79 for adults with first injury after age 55.

—Erik Greb

Man, 56, With Wrist Pain After a Fall

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

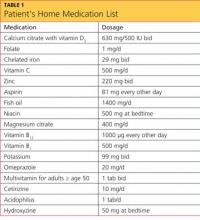

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

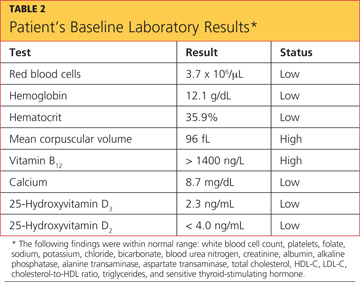

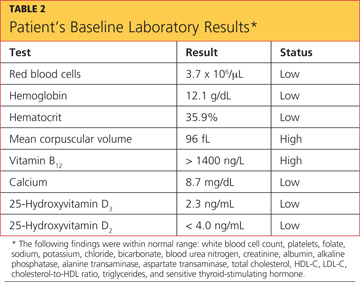

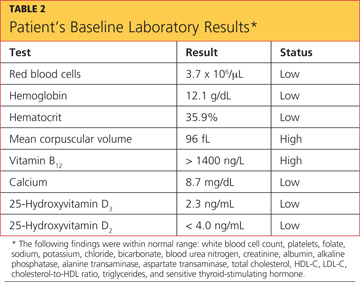

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

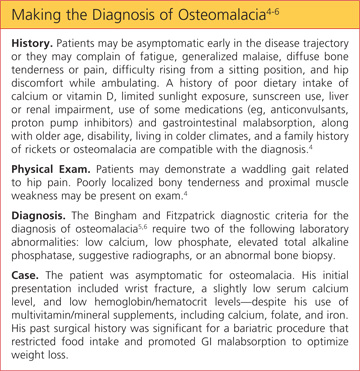

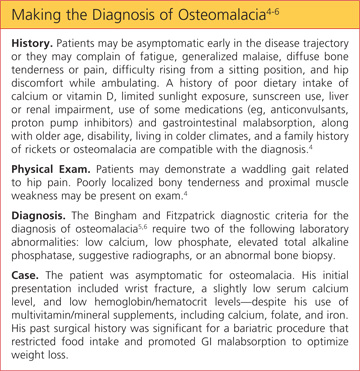

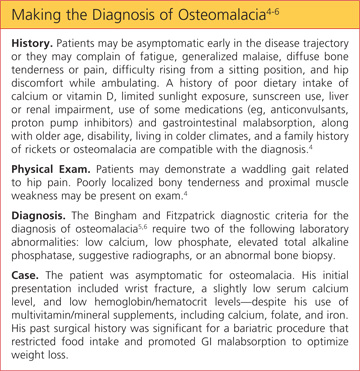

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

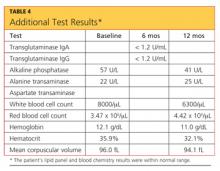

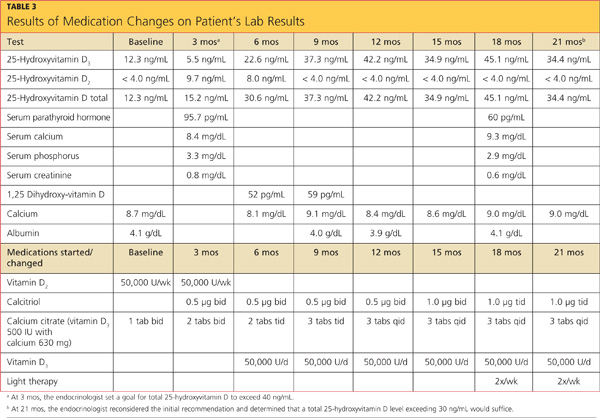

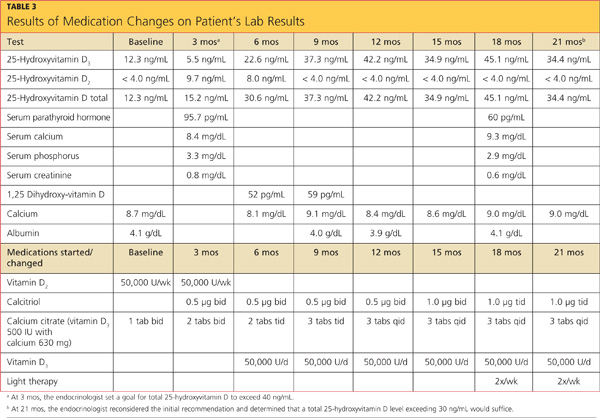

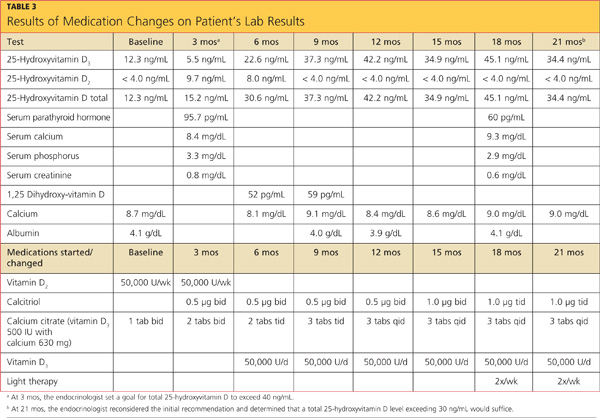

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.

19. Bhan A, Rao AD, Rao DS. Osteomalacia as a result of vitamin D deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):321-331.

20. Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571-2580.

21. Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge C, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179(4):319-326.

22. Ybarra J, Sánchez-Hernández J, Pérez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):19-27.

23. Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, et al. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):15-22.

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.

19. Bhan A, Rao AD, Rao DS. Osteomalacia as a result of vitamin D deficiency. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(2):321-331.

20. Decker GA, Swain JM, Crowell MD. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications after bariatric surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(11):2571-2580.

21. Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge C, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179(4):319-326.

22. Ybarra J, Sánchez-Hernández J, Pérez A. Hypovitaminosis D and morbid obesity. Nurs Clin North Am. 2007;42(1):19-27.

23. Aasheim ET, Björkman S, Søvik TT, et al. Vitamin status after bariatric surgery: a randomized study of gastric bypass and duodenal switch. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(1):15-22.

A white man, age 56, presented to his primary care clinician with wrist pain and swelling. Two days earlier, he had fallen from a step stool and landed on his right wrist. He treated the pain by resting, elevating his arm, applying ice, and taking ibuprofen 800 mg tid. He said he had lost strength in his hand and arm and was experiencing numbness and tingling in his right hand and fingers.

The patient’s medical history included hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, morbid obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, carpel tunnel syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy. His surgical history was significant for duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery, performed eight years earlier, and his weight at the time of presentation was 200 lb; before his gastric bypass, he weighed 385 lb. Since the surgery, his hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and sleep apnea had all resolved. Table 1 shows a list of medications he was taking at the time of presentation.

The patient, a registered nurse, had been married for 30 years and had one child. He had quit smoking 15 years earlier, with a 43–pack-year smoking history. He reported social drinking but denied any recreational drug use. He was unaware of having any allergies to food or medication.

His vital signs on presentation were blood pressure, 110/75 mm Hg; heart rate, 53 beats/min; respiration, 18 breaths/min; O2 saturation, 97% on room air; and temperature, 97.5°F.

Physical exam revealed that the patient’s right wrist was ecchymotic and swollen with +1 pitting edema. The skin was warm and dry to the touch. Decreased range of motion was noted in the right wrist, compared with the left. Pain with point tenderness was noted at the right lateral wrist. Pulses were +3 with capillary refill of less than 3 seconds. The rest of the exam was unremarkable.

The differential diagnosis included fracture secondary to the fall, osteoporosis, osteopenia, osteomalacia, Paget’s disease, tumor, infection, and sprain or strain of the wrist. A wrist x-ray was ordered, as were the following baseline labs: complete blood count with differential (CBC), vitamin B12 and folate levels, blood chemistry, lipid profile, liver profile, total vitamin D, and sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone. Test results are shown in Table 2.

X-ray of the wrist showed fracture only, making it possible to rule out Paget’s disease (ie, no patchy white areas noted in the bone) and tumor (no masses seen) as the immediate cause of fracture. Normal body temperature and normal white blood cell count eliminated the possibility of infection.

Because the patient was only 56 and had a history of bariatric surgery, further testing was pursued to investigate a cause for the weakened bone. Bone mineral density (BMD) testing revealed the following results:

• The lumbar spine in frontal projection measured 0.968 g/cm2 with a T-score of –2.2 and a Z-score of –2.2.

• Total BMD of the left hip was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of –1.7 and a Z-score of –1.4.

• Total BMD of the left femoral neck was 0.863 g/cm2 with a T-score of 1.7 and a Z-score of –1.1.

These findings suggested osteopenia1,2 (not osteoporosis) in all sites, with a 12% decrease of BMD in the spine (suggesting increased risk for spinal fracture) and a 16.3% decrease of BMD in the hip since the patient’s most recent bone scan five years earlier (radiologist’s report). Other abnormal findings were elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) serum, 95.7 pg/mL (reference range, 10 to 65 pg/mL); low total calcium serum, 8.7 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9 to 10.2 mg/dL), and low 25-hydroxyvitamin D total, 12.3 ng/mL (reference range, 25 to 80 ng/mL).

A 2010 clinical practice guideline from the Endocrine Society3 specifies that after malabsorptive surgery, vitamin D and calcium supplementation should be adjusted by a qualified medical professional, based on serum markers and measures of bone density. An endocrinologist who was consulted at the patient’s initial visit prescribed the following medications: vitamin D2, 50,000 U/wk PO; combined calcium citrate (vitamin D3) 500 IU with calcium 630 mg, 1 tab bid; and calcitriol 0.5 μg bid.

The patient’s final diagnosis was osteomalacia secondary to gastric bypass surgery. (See “Making the Diagnosis of Osteomalacia.”4-6)

DISCUSSION

According to 2008 data from the World Health Organization (WHO),7 1.4 billion persons older than 20 worldwide were overweight, and 200 million men and 300 million women were considered obese—meaning that one in every 10 adults worldwide is overweight or obese. In 2010, the WHO reports, 40 million children younger than 5 worldwide were considered overweight.7 Health care providers need to be prepared to care for the increasing number of patients who will undergo bariatric surgeries to treat obesity and its related comorbidities.8

Postoperative follow-up for the malabsorption deficiencies related to bariatric procedures should be performed every six months, including obtaining levels of alkaline phosphatase and others previously discussed. In addition, the Endocrine Society guideline3 recommends measuring levels of vitamin B12, albumin, pre-albumin, iron, and ferritin, and obtaining a CBC, a liver profile, glucose reading, creatinine measurement, and a metabolic profile at one month and two months after surgery, then every six months until two years after surgery, then annually if findings are stable.

Furthermore, the Endocrine Society3 recommends obtaining zinc levels every six months for the first year, then annually. An annual vitamin A level is optional.9 Yearly bone density testing is recommended until the patient’s BMD is deemed stable.3

Additionally, Koch and Finelli10 recommend performing the following labs postoperatively: hemoglobin A1C every three months; copper, magnesium, whole blood thiamine, vitamin B12, and a 24-hour urinary calcium every six months for the first three years, then once a year if findings remain stable.

Use of alcohol should be discouraged among patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, as its use alters micronutrient requirements and metabolism. Alcohol consumption may also contribute to dumping syndrome (ie, rapid gastric emptying).11

Any patient with a history of malabsorptive bypass surgery who complains of neurologic, visual, or skin disorders, anemia, or edema may require a further workup to rule out other absorptive deficiencies. These include vitamins A, E, and B12, zinc, folate, thiamine, niacin, selenium, and ferritin.10

Osteomalacia

Metabolic bone diseases can result from genetics, dietary factors, medication use, surgery, or hormonal irregularities. They alter the normal biochemical reactions in bone structure.

The three most common forms of metabolic bone disease are osteoporosis, osteopenia, and osteomalacia. The WHO diagnostic classifications and associated T-scores for bone mineral density1,2 indicate a T-score above –1.0 as normal. A score between –1.0 and –2.5 is indicative of osteopenia, and a score below –2.5 indicates osteoporosis. A T-score below –2.5 in the patient with a history of fragility fracture indicates severe osteoporosis.1,2

In osteomalacia, bone volume remains unchanged, but mineralization of osteoid in the mature compact and spongy bone is either delayed or inadequate. The remolding cycle continues unchanged in the formation of osteoid, but mineral calcification and deposition do not occur.3-5

Osteomalacia is normally considered a rare disorder, but it may become more common as increasing numbers of patients undergo gastric bypass operations.12,13 Primary care practitioners should monitor for this condition in such patients before serious bone loss or other problems develop.9,13,14

Vitamin D deficiency (see “Vitamin D Metabolism,”4,15-19 below), whether or not the result of gastric bypass surgery, is a major risk factor for osteomalacia. Disorders of the small bowel, the hepatobiliary system, and the pancreas are all common causes of vitamin D deficiency. Liver disease interferes with the metabolism of vitamin D. Diseases of the pancreas may cause a deficiency of bile salts, which are vital for the intestinal absorption of vitamin D.17

Restriction and Malabsorption

The case patient had undergone a gastric bypass (duodenal switch), in which a large portion of the stomach is removed and a large part of the small bowel rerouted—with both parts of the procedure causing malabsorption.11 It is in the small bowel that absorption of vitamin D and calcium takes place.

The duodenal switch gastric bypass surgery causes both restriction and malabsorption. Though similar to a biliopancreatic diversion, the duodenal switch preserves the distal stomach and the pylorus20 by way of a sleeve gastrectomy that is performed to reduce the gastric reservoir; the common channel length after revision is 100 cm, not 50 cm (as in conventional biliopancreatic diversion).13 The sleeve gastrectomy involves removal of parietal cells, reducing production of hydrochloric acid (which is necessary to break down food), and hindering the absorption of certain nutrients, including the fat-soluble vitamins, vitamin B12, and iron.12 Patients who take H2-blockers or proton pump inhibitors experience an additional decrease in the production and availability of HCl and may have an increased risk for fracture.14,20,21

In addition to its biliopancreatic diversion component, the duodenal switch diverts a large portion of the small bowel, with food restricted from moving through it. Vitamin D and protein are normally absorbed at the jejunum and ileum, but only when bile salts are present; after a duodenal switch, bile and pancreatic enzymes are not introduced into the small intestines until 75 to 100 cm before they reach the large intestine. Thus, absorption of vitamin D, protein, calcium, and other nutrients is impaired.20,22

Since phosphorus and magnesium are also absorbed at the sites of the duodenum and jejunum, malabsorption of these nutrients may occur in a patient who has undergone a duodenal switch. Although vitamin B12 is absorbed at the site of the distal ileum, it also requires gastric acid to free it from the food. Zinc absorption, which normally occurs at the site of the jejunum, may be impaired after duodenal switch surgery, and calcium supplementation, though essential, may further reduce zinc absorption.9 Iron absorption requires HCl, facilitated by the presence of vitamin C. Use of H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors may impair iron metabolism, resulting in anemia.20

In a randomized controlled trial, Aasheim et al23 compared the effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with those of duodenal switch gastric bypass on patients’ vitamin metabolism. The researchers concluded that patients who undergo a duodenal switch are at greater risk for vitamin A and D deficiencies in the first year after surgery; and for thiamine deficiency in the months following surgery as a result of malabsorption, compared with patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.20,23

Patient Management

The case patient’s care necessitated consultations with endocrinology, dermatology, and gastroenterology (GI). Table 3 (below) shows the laboratory findings and the medication changes prompted by the patient’s physical exam and lab results. Table 4 lists the findings from other lab studies ordered throughout the patient’s course of treatment.

The endocrinologist was consulted at the first sign of osteopenia, and a workup was soon initiated, followed by treatment. GI was consulted six months after the beginning of treatment, when the patient began to complain of reflux while sleeping and frequent diarrhea throughout the day.

Results of esophagogastroduodenoscopy with biopsy ruled out celiac disease and mucosal ulceration, but a small hiatal hernia that was detected (< 3 cm) was determined to be an aggravating factor for the patient’s reflux. The patient was instructed in lifestyle modifications for hiatal hernia, including the need to remain upright one to two hours after eating before going to sleep to prevent aspiration. The patient was instructed to avoid taking iron and calcium within two hours of each other and to limit his alcohol intake. He was also educated in precautions against falls.

Dermatology was consulted nine months into treatment so that light therapy could be initiated, allowing the patient to take advantage of the body’s natural pathway to manufacture vitamin D3.

CONCLUSION

For post–bariatric surgery patients, primary care practitioners are in a position to coordinate care recommendations from multiple specialists, including those in nutrition, to determine the best course of action.

This case illustrates complications of bariatric surgery (malabsorption of key vitamins and minerals, wrist fracture, osteopenia, osteomalacia) that require diagnosis and treatment. The specialists and the primary care practitioner, along with the patient, had to weigh the risks and benefits of continued proton pump inhibitor use, as such medications can increase the risk for fracture. They also addressed the patient’s anemia and remained attentive to his preventive health care needs.

REFERENCES

1. Brusin JH. Update on bone densitometry. Radiol Technol. 2009;81(2):153BD-170BD.

2. Wilson CR. Essentials of bone densitometry for the medical physicist. Presented at: The American Association of Physicists in Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting; July 22-26, 2003; San Diego, CA.

3. Heber D, Greenway FL, Kaplan LM. et al. Endocrine and nutritional management of the post-bariatric surgery patient: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(11):4825-4843.

4. Osteomalacia: step-by-step diagnostic approach (2011). http://bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/517/diagnosis/step-by-step.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

5. Gifre L, Peris P, Monegal A, et al. Osteomalacia revisited : a report on 28 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(5):639-645.

6. Bingham CT, Fitzpatrick LA. Noninvasive testing in the diagnosis of osteomalacia. Am J Med. 1993;95(5):519-523.

7. World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight (May 2012). Fact Sheet No 311. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html. Accessed December 18, 2012.

8. Tanner BD, Allen JW. Complications of bariatric surgery: implications for the covering physician. Am Surg. 2009;75(2):103-112.

9. Soleymani T, Tejavanija S, Morgan S. Obesity, bariatric surgery, and bone. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23(4):396-405.

10. Koch TR, Finelli FC. Postoperative metabolic and nutritional complications of bariatric surgery. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39(1):109-124.

11. Manchester S, Roye GD. Bariatric surgery: an overview for dietetics professionals. Nutr Today. 2011;46(6):264-275.

12. Bal BS, Finelli FC, Shope TR, Koch TR. Nutritional deficiencies after bariatric surgery. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8(9):544-546.

13. Iannelli A, Schneck AS, Dahman M, et al. Two-step laparoscopic duodenal switch for superobesity: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(10):2385-2389.

14. Lalmohamed A, de Vries F, Bazelier MT, et al. Risk of fracture after bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom: population based, retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e5085.

15. Holrick MF. Vitamin D: important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. South Med J. 2005;98 (10):1024-1027.

16. Kalro BN. Vitamin D and the skeleton. Alt Ther Womens Health. 2009;2(4):25-32.

17. Crowther-Radulewicz CL, McCance KL. Alterations of musculoskeletal function. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1568-1617.

18. Huether SE. Structure and function of the renal and urologic systems. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, Brashers VL, Rote NS, eds. Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. 6th ed. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:1344-1364.