User login

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

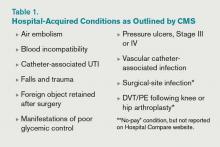

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Quality Journey of Hospitalist David J. Yu

Hospitalist David J. Yu, MD, FACP, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the adult inpatient service at Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., began his quality journey by earning an MBA, then spending a week at University of Toyota in Gardena, Calif., to learn its Lean process-management techniques. He presented a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes poster at HM12 that outlined the multidisciplinary quality initiative at 453-bed Presbyterian Hospital in Albuquerque.

The project identified problems of throughput, ED diversion, disjointed team rounding, inadequate communication, multiple patient handoffs, low staff morale, and greater-than-expected length of stay (LOS).

“We really dug into the issues on a granular level,” with the participation of finance, nursing, care coordinators, physical therapy, and other staffers alongside the hospitalists, Dr. Yu says. The project ended up changing the practice from a model in which 11 hospitalist teams and five admitting hospitalists cared for patients throughout the hospital’s various floors while carrying caseloads too high to manage optimally. They replaced it with a unit-based rounding model, with hospitalists and care coordinators geographically segregated on units and multidisciplinary rounds to improve the efficiency of team communication (see “A Holy Grail,” July 2012, p. 30).

The group also used data to persuade the hospital’s administration to add hospitalist FTEs. As a result, LOS on two pilot units decreased by nearly half a day, with increased inpatient volume, higher patient satisfaction scores on Press-Ganey surveys, and an estimated net financial benefit of nearly $3.5 million between April 2010 and December 2011—even counting the additional hospitalist FTEs. This model has since spread to all medical units in the hospital.

“We need to be in the business of producing ‘defect-free’ discharges,” Dr. Yu quips. “Every group needs a local solution. But the mantra for this work is standardization....That’s where the leadership of the hospitalist comes in. It’s not, ‘Follow me,’ but ‘Hey, join us in collaborating together to come up with a solution.’

“It has been a two-year journey, and we’re still learning.”

Hospitalist David J. Yu, MD, FACP, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the adult inpatient service at Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., began his quality journey by earning an MBA, then spending a week at University of Toyota in Gardena, Calif., to learn its Lean process-management techniques. He presented a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes poster at HM12 that outlined the multidisciplinary quality initiative at 453-bed Presbyterian Hospital in Albuquerque.

The project identified problems of throughput, ED diversion, disjointed team rounding, inadequate communication, multiple patient handoffs, low staff morale, and greater-than-expected length of stay (LOS).

“We really dug into the issues on a granular level,” with the participation of finance, nursing, care coordinators, physical therapy, and other staffers alongside the hospitalists, Dr. Yu says. The project ended up changing the practice from a model in which 11 hospitalist teams and five admitting hospitalists cared for patients throughout the hospital’s various floors while carrying caseloads too high to manage optimally. They replaced it with a unit-based rounding model, with hospitalists and care coordinators geographically segregated on units and multidisciplinary rounds to improve the efficiency of team communication (see “A Holy Grail,” July 2012, p. 30).

The group also used data to persuade the hospital’s administration to add hospitalist FTEs. As a result, LOS on two pilot units decreased by nearly half a day, with increased inpatient volume, higher patient satisfaction scores on Press-Ganey surveys, and an estimated net financial benefit of nearly $3.5 million between April 2010 and December 2011—even counting the additional hospitalist FTEs. This model has since spread to all medical units in the hospital.

“We need to be in the business of producing ‘defect-free’ discharges,” Dr. Yu quips. “Every group needs a local solution. But the mantra for this work is standardization....That’s where the leadership of the hospitalist comes in. It’s not, ‘Follow me,’ but ‘Hey, join us in collaborating together to come up with a solution.’

“It has been a two-year journey, and we’re still learning.”

Hospitalist David J. Yu, MD, FACP, MBA, SFHM, medical director of the adult inpatient service at Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., began his quality journey by earning an MBA, then spending a week at University of Toyota in Gardena, Calif., to learn its Lean process-management techniques. He presented a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes poster at HM12 that outlined the multidisciplinary quality initiative at 453-bed Presbyterian Hospital in Albuquerque.

The project identified problems of throughput, ED diversion, disjointed team rounding, inadequate communication, multiple patient handoffs, low staff morale, and greater-than-expected length of stay (LOS).

“We really dug into the issues on a granular level,” with the participation of finance, nursing, care coordinators, physical therapy, and other staffers alongside the hospitalists, Dr. Yu says. The project ended up changing the practice from a model in which 11 hospitalist teams and five admitting hospitalists cared for patients throughout the hospital’s various floors while carrying caseloads too high to manage optimally. They replaced it with a unit-based rounding model, with hospitalists and care coordinators geographically segregated on units and multidisciplinary rounds to improve the efficiency of team communication (see “A Holy Grail,” July 2012, p. 30).

The group also used data to persuade the hospital’s administration to add hospitalist FTEs. As a result, LOS on two pilot units decreased by nearly half a day, with increased inpatient volume, higher patient satisfaction scores on Press-Ganey surveys, and an estimated net financial benefit of nearly $3.5 million between April 2010 and December 2011—even counting the additional hospitalist FTEs. This model has since spread to all medical units in the hospital.

“We need to be in the business of producing ‘defect-free’ discharges,” Dr. Yu quips. “Every group needs a local solution. But the mantra for this work is standardization....That’s where the leadership of the hospitalist comes in. It’s not, ‘Follow me,’ but ‘Hey, join us in collaborating together to come up with a solution.’

“It has been a two-year journey, and we’re still learning.”

Defining and Protecting Scope of Practice Critical for Hospitalists

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Scope creep can lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes if hospitalist practices fail to plan appropriately, Dr. Simone says. The plan must include “development of a staffing and schedule model to accommodate service expansion (when applicable), creation of policies and procedures addressing the new services, and hospitalist training (when appropriate) to ensure competently trained providers,” he adds.

Before any HM group agrees to comanagement, it should first understand the reasons for the request, Dr. Siegal says. According to a presentation he gave at HM07 on the topic, group leaders should:

- Determine if comanagement is a reasonable solution to the problem.

- Identify stakeholders and understand their goals, concerns, and expectations.

- Ask what might be jeopardized if hospitalists participate: Will it overload an already busy service, compromise care elsewhere, or set unrealistic service expectations?

- Set measurable outcomes to quantify the success (or failure) of the new arrangement.

It’s also important to define responsibilities, establish clear lines of communication, and determine how disagreements will be adjudicated. Establish your scope of practice and stick to it, Dr. Siegal says. A big red flag is when your group does things on nights, weekends, or holidays that it doesn’t do during the week.

Five Ways Hospitalists Can Prevent Overextending Their Services

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

1. Do not feel sorry for yourself; it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Most of what is happening in medicine is outside of our control,” Dr. Nelson says. “We need to realize that our role is going to change, and we should not perceive ourselves as the low person on the totem pole.”

2. Increase “face time” with your specialist colleagues.

Join them for lunch in the physician’s lounge, call your colleagues by their first names, engage in meaningful discussions about cases, and show empathy for them and their patients. Look for opportunities to do mutual education with other services.

3. Know when to draw the line.

“HM leaders should have the skills to analyze an opportunity and assess whether their program has the staffing capacity and clinical skills to successfully deliver a requested service,” Dr. Simone says. “‘No’ is an acceptable answer, if there are clear and reasonable reasons that support that decision.”

4. Make it about the patient.

Whenever your HM service is approached about comanagement, phrase your decision within the context of ensuring patient safety and delivering quality care. In that way, Dr. Siy says, you will be on solid footing.

5. Openly promote strategic “yes” answers.

Instead of digging in their heels, HM groups can periodically examine all requests, pick one or two to begin with, then promote successful outcomes to boost the group’s value.

Shaun Frost: Society of Hospital Medicine Supports the Choosing Wisely Campaign (CWC)

SHM is participating in the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely Campaign (CWC).1 Launched earlier this year, the CWC aims to increase awareness about medical practices that may be of little or no benefit to patients. Presently, 26 physician organizations have teamed with the ABIM Foundation to each create a list of “five things physicians and patients should question.” In addition, Consumer Reports (the product ratings organization well known for grading the quality of such items as automobiles and vacuum cleaners) is coordinating the efforts of 11 consumer groups to advance the CWC agenda.

The CWC aims to highlight two pillars of healthcare reform that will receive enhanced attention in the near future: 1. Cost of care, and 2. Patient experience of care. Heretofore healthcare reform efforts have largely been focused on the quality and patient-safety movements. Equally important, however, to policymakers is affordability and care experience. By focusing on tests and procedures of questionable benefit, the CWC aims to directly address costly unnecessary treatment by encouraging care planning that incorporates patient preferences. This is necessary work because research suggests that physician decisions account for 80% of healthcare expenditures, while the tradition of patients entrusting their doctors with complete decision-making authority leads to care that they do not want.2

Choosing Wisely Begins with Medical Professionalism

In 2002, the ABIM Foundation collaborated with the American College of Physicians Foundation and the European Federation of Internal Medicine to jointly author “Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter.”3 The charter has since been endorsed by more than 130 organizations and triggered countless improvement initiatives to advance its fundamental principles of patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice.

Through project grant support, the ABIM Foundation is emphasizing two key Physician Charter commitments (see Table 1) to advance appropriate healthcare decision-making and encourage stewardship of healthcare resources. The CWC naturally augments this work by focusing on care affordability and decision-making through shared discussions between patients and providers.

SHM’s Involvement

SHM convened a workgroup of hospital medicine quality improvement experts led by John Bulger, DO, the chief quality officer at Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania. This group solicited from SHM committee members 150 suggested tests and treatments that HM clinicians and their patients should question. After critical analysis, the list was narrowed to exclude suggestions already being advanced by the CWC while focusing on those that represent the largest opportunity for hospitalists to impact on affordability and patient experience.

The list was then submitted to SHM members for comment via survey, resulting in 11 recommended medical interventions that were subjected to comprehensive literature review. Workgroup members then rated these 11 interventions according to the following criteria: validity of supporting evidence, feasibility and degree of hospitalist impact, frequency of occurrence, and cost of occurrence.

Finally, the workgroup collaborated with the SHM board of directors to submit to the ABIM Foundation the ultimate list of “five things hospitalists and their patients should question.” Ricardo Quinonez, MD, at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, led a similar process that generated a list of questionable practices in pediatric HM. It, too, was submitted to the ABIM Foundation.

The CWC anticipates publishing SHM’s list in February 2013. In the meantime, please consult the CWC website to find practices commonly performed by hospitalists that have been deemed to be of unclear benefit by other professional medical societies (see “2012 CWC Recommendations for Hospitalists,” left).

SHM plans to build upon this work in the future. Expect to see Choosing Wisely sessions and discussions at the HM13 SHM Annual Meeting in May (www.hospitalmedicine2013.org) focused on creating and teaching QI strategies to implement CWC recommendations. Furthermore, the Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement will be identifying opportunities to develop mentored implementation QI programs related to Choosing Wisely and its principles.

What You Can Do

Hospitalists can make a huge impact on affordability and patient experience given that most of the country’s healthcare dollar is spent in the hospital, and patients are at their most vulnerable to receiving treatment that they may not want when they are acutely ill. Hospitalists, thus, are uniquely positioned to make a positive impact by embracing the Choosing Wisely Campaign’s principles.

Please commit to assisting SHM by visiting the CWC website and learning about other medical society’s thoughts on “things physicians and patients should question.” Pledge thereafter to engage your patients and their families in healthcare decision-making, especially in situations where the benefits of tests and therapies are unclear.

Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- The ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely website. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- The ABIM Foundation. Principles Guiding Wise Choices. ABIM Foundation website. Available at: www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/~/media/Files/2011-Forum/110411_ABIM%20Stewardship.ashx. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- ABIM Foundation, ACP–ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243.

SHM is participating in the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely Campaign (CWC).1 Launched earlier this year, the CWC aims to increase awareness about medical practices that may be of little or no benefit to patients. Presently, 26 physician organizations have teamed with the ABIM Foundation to each create a list of “five things physicians and patients should question.” In addition, Consumer Reports (the product ratings organization well known for grading the quality of such items as automobiles and vacuum cleaners) is coordinating the efforts of 11 consumer groups to advance the CWC agenda.

The CWC aims to highlight two pillars of healthcare reform that will receive enhanced attention in the near future: 1. Cost of care, and 2. Patient experience of care. Heretofore healthcare reform efforts have largely been focused on the quality and patient-safety movements. Equally important, however, to policymakers is affordability and care experience. By focusing on tests and procedures of questionable benefit, the CWC aims to directly address costly unnecessary treatment by encouraging care planning that incorporates patient preferences. This is necessary work because research suggests that physician decisions account for 80% of healthcare expenditures, while the tradition of patients entrusting their doctors with complete decision-making authority leads to care that they do not want.2

Choosing Wisely Begins with Medical Professionalism

In 2002, the ABIM Foundation collaborated with the American College of Physicians Foundation and the European Federation of Internal Medicine to jointly author “Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter.”3 The charter has since been endorsed by more than 130 organizations and triggered countless improvement initiatives to advance its fundamental principles of patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice.

Through project grant support, the ABIM Foundation is emphasizing two key Physician Charter commitments (see Table 1) to advance appropriate healthcare decision-making and encourage stewardship of healthcare resources. The CWC naturally augments this work by focusing on care affordability and decision-making through shared discussions between patients and providers.

SHM’s Involvement

SHM convened a workgroup of hospital medicine quality improvement experts led by John Bulger, DO, the chief quality officer at Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania. This group solicited from SHM committee members 150 suggested tests and treatments that HM clinicians and their patients should question. After critical analysis, the list was narrowed to exclude suggestions already being advanced by the CWC while focusing on those that represent the largest opportunity for hospitalists to impact on affordability and patient experience.

The list was then submitted to SHM members for comment via survey, resulting in 11 recommended medical interventions that were subjected to comprehensive literature review. Workgroup members then rated these 11 interventions according to the following criteria: validity of supporting evidence, feasibility and degree of hospitalist impact, frequency of occurrence, and cost of occurrence.

Finally, the workgroup collaborated with the SHM board of directors to submit to the ABIM Foundation the ultimate list of “five things hospitalists and their patients should question.” Ricardo Quinonez, MD, at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, led a similar process that generated a list of questionable practices in pediatric HM. It, too, was submitted to the ABIM Foundation.

The CWC anticipates publishing SHM’s list in February 2013. In the meantime, please consult the CWC website to find practices commonly performed by hospitalists that have been deemed to be of unclear benefit by other professional medical societies (see “2012 CWC Recommendations for Hospitalists,” left).

SHM plans to build upon this work in the future. Expect to see Choosing Wisely sessions and discussions at the HM13 SHM Annual Meeting in May (www.hospitalmedicine2013.org) focused on creating and teaching QI strategies to implement CWC recommendations. Furthermore, the Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement will be identifying opportunities to develop mentored implementation QI programs related to Choosing Wisely and its principles.

What You Can Do

Hospitalists can make a huge impact on affordability and patient experience given that most of the country’s healthcare dollar is spent in the hospital, and patients are at their most vulnerable to receiving treatment that they may not want when they are acutely ill. Hospitalists, thus, are uniquely positioned to make a positive impact by embracing the Choosing Wisely Campaign’s principles.

Please commit to assisting SHM by visiting the CWC website and learning about other medical society’s thoughts on “things physicians and patients should question.” Pledge thereafter to engage your patients and their families in healthcare decision-making, especially in situations where the benefits of tests and therapies are unclear.

Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- The ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely website. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- The ABIM Foundation. Principles Guiding Wise Choices. ABIM Foundation website. Available at: www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/~/media/Files/2011-Forum/110411_ABIM%20Stewardship.ashx. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- ABIM Foundation, ACP–ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243.

SHM is participating in the ABIM Foundation's Choosing Wisely Campaign (CWC).1 Launched earlier this year, the CWC aims to increase awareness about medical practices that may be of little or no benefit to patients. Presently, 26 physician organizations have teamed with the ABIM Foundation to each create a list of “five things physicians and patients should question.” In addition, Consumer Reports (the product ratings organization well known for grading the quality of such items as automobiles and vacuum cleaners) is coordinating the efforts of 11 consumer groups to advance the CWC agenda.

The CWC aims to highlight two pillars of healthcare reform that will receive enhanced attention in the near future: 1. Cost of care, and 2. Patient experience of care. Heretofore healthcare reform efforts have largely been focused on the quality and patient-safety movements. Equally important, however, to policymakers is affordability and care experience. By focusing on tests and procedures of questionable benefit, the CWC aims to directly address costly unnecessary treatment by encouraging care planning that incorporates patient preferences. This is necessary work because research suggests that physician decisions account for 80% of healthcare expenditures, while the tradition of patients entrusting their doctors with complete decision-making authority leads to care that they do not want.2

Choosing Wisely Begins with Medical Professionalism

In 2002, the ABIM Foundation collaborated with the American College of Physicians Foundation and the European Federation of Internal Medicine to jointly author “Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter.”3 The charter has since been endorsed by more than 130 organizations and triggered countless improvement initiatives to advance its fundamental principles of patient welfare, patient autonomy, and social justice.

Through project grant support, the ABIM Foundation is emphasizing two key Physician Charter commitments (see Table 1) to advance appropriate healthcare decision-making and encourage stewardship of healthcare resources. The CWC naturally augments this work by focusing on care affordability and decision-making through shared discussions between patients and providers.

SHM’s Involvement

SHM convened a workgroup of hospital medicine quality improvement experts led by John Bulger, DO, the chief quality officer at Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania. This group solicited from SHM committee members 150 suggested tests and treatments that HM clinicians and their patients should question. After critical analysis, the list was narrowed to exclude suggestions already being advanced by the CWC while focusing on those that represent the largest opportunity for hospitalists to impact on affordability and patient experience.

The list was then submitted to SHM members for comment via survey, resulting in 11 recommended medical interventions that were subjected to comprehensive literature review. Workgroup members then rated these 11 interventions according to the following criteria: validity of supporting evidence, feasibility and degree of hospitalist impact, frequency of occurrence, and cost of occurrence.

Finally, the workgroup collaborated with the SHM board of directors to submit to the ABIM Foundation the ultimate list of “five things hospitalists and their patients should question.” Ricardo Quinonez, MD, at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, led a similar process that generated a list of questionable practices in pediatric HM. It, too, was submitted to the ABIM Foundation.

The CWC anticipates publishing SHM’s list in February 2013. In the meantime, please consult the CWC website to find practices commonly performed by hospitalists that have been deemed to be of unclear benefit by other professional medical societies (see “2012 CWC Recommendations for Hospitalists,” left).

SHM plans to build upon this work in the future. Expect to see Choosing Wisely sessions and discussions at the HM13 SHM Annual Meeting in May (www.hospitalmedicine2013.org) focused on creating and teaching QI strategies to implement CWC recommendations. Furthermore, the Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement will be identifying opportunities to develop mentored implementation QI programs related to Choosing Wisely and its principles.

What You Can Do

Hospitalists can make a huge impact on affordability and patient experience given that most of the country’s healthcare dollar is spent in the hospital, and patients are at their most vulnerable to receiving treatment that they may not want when they are acutely ill. Hospitalists, thus, are uniquely positioned to make a positive impact by embracing the Choosing Wisely Campaign’s principles.

Please commit to assisting SHM by visiting the CWC website and learning about other medical society’s thoughts on “things physicians and patients should question.” Pledge thereafter to engage your patients and their families in healthcare decision-making, especially in situations where the benefits of tests and therapies are unclear.

Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same.

Dr. Frost is president of SHM.

References

- The ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely: An initiative of the ABIM Foundation. Choosing Wisely website. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- The ABIM Foundation. Principles Guiding Wise Choices. ABIM Foundation website. Available at: www.abimfoundation.org/Initiatives/~/media/Files/2011-Forum/110411_ABIM%20Stewardship.ashx. Accessed Sept. 25, 2012.

- ABIM Foundation, ACP–ASIM Foundation, European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical Professionalism in the New Millennium: A Physician Charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243.

Why It's Hard for Healthcare Providers to Say I'm Sorry

It’s 1982, and in middle-school gyms across the country, among punch bowls and parental scrutiny, young girls and boys are slow-dancing with outstretched arms to a breathtaking song by the band Chicago. The song tells of the agonizing difficulty of apology, how despite the want and need to apologize, it is just too arduous.

Fast-forward 30 years, and it is hard to believe that cheesy No. 1 Billboard hit espoused the feelings that continue to haunt healthcare providers across the country: It’s hard for me to say I’m sorry.

Others Say It

If you look at the world around us, you see apology everywhere. Customer service representatives and customer-minded industries routinely let those words flow off their tongues with ease and grace.

While I was driving down the interstate last week, the number of traffic lanes shrunk from three to two to one. Anticipating widespread aggravation from weary travelers, the state transportation department deployed several large road signs every few miles; they read “WE APOLOGIZE FOR THE INCONVENIENCE … BEAR WITH US WHILE WE MAKE YOUR ROADS SMOOTHER AND SAFER.” Those simple messages made me feel like the congestion was not a senseless waste of time, that the state’s Department of Transportation was actually being strategic and thoughtful in their rationing of lanes during rush hour in the middle of the week.

Phone-based, customer-service departments figured out the simple apology a long time ago. While holding the line for a Lands’ End customer-service representative a few weeks ago, I heard, “We apologize for the delay. Your business is important to us. Please hold the line while we address callers ahead of you.” It validated for me that those phone representatives are not just sitting around eating lunch, completely ignoring my call, and that maybe there are others who procrastinated buying back-to-school backpacks until September—and just happened to call right before me.

I even got an apology at the dry cleaner. Amidst my last batch of clothes, my astute dry cleaner apparently found a very stubborn stain, which resisted all of their usual concoctions. It was on the back of a shirt and I probably would not have even noticed it was there. But nonetheless, they sent an apology tag, with a picture of a distraught butler who seemed to have struggled with that stain for hours.

Why Not Us?

So why is “sorry” so hard in healthcare? When things happen to patients, things that are inconvenient or downright dangerous, we have great difficulty in simply saying: “Hey, I am really sorry this happened to you,” or “I am so sorry you are still here. You must be really frustrated by our inefficiencies.”

I have the distinct pleasure of overseeing my hospital’s risk-management department for a few months. This means I get to see and hear what does and doesn’t happen to patients, which, at times, is misaligned with what should or shouldn’t happen to patients. When unanticipated events occur, the group launches into an investigation of what happened, why it happened, and the risk that it could happen again. After the initial dust settles and the facts are relayed from the care team to the risk-management team, the risk team always asks of those involved: “So what does the patient and their family know?” And we get a range of answers—some polished, some fumbled, some baffled.

The next question is: “Well, what should they know?” And that is always an easy question to answer. They should know the truth. Not just some of the truth, or half the truth, or a partial truth. Not what the care team thinks the patient “can handle.” They should just get the truth. To the best of the team’s ability, they should tell the patient:

- What (they think) happened;

- Why (they think) it happened;

- What it means for the patient; and

- What they are going to do to make it not happen again.

And then the patient (and family members) deserve an apology—sincere, compassionate, genuine. The apology should be the easy part, as most providers do not always know what happened, why it happened, or what they are going to do to prevent it from happening, but they usually truly do feel sorry that it happened at all.

“Sorry”=Positive Results

Patients are unanimous in their desire to be informed if a medical error has occurred; focus groups have found that patients believe such information would enhance their trust in their physicians and would reassure them that they were receiving complete information. And they want an apology.1

But interestingly, many physicians believe that full disclosure with apology is not warranted or appropriate, and that the apology could erode patient trust, might scare the patient, and might increase the risk of legal liability.1

There is little evidence that disclosure is harmful or detrimental, and there is some evidence that it is beneficial to the medical industry (i.e. reduces claims and litigation costs). A study published in 2010 from the University of Michigan Health System found a disclosure-with-compensation program was associated with a 36% reduction in new claims, a 65% reduction in lawsuits, and a 59% reduction in total liability cost.2

I have witnessed this phenomenon from both sides. My mother, who has Alzheimer’s and lives in an assisted-living facility, recently was given twice the dose of her medications one morning. She was “given” her night medications by being placed in her room, which she has no recollection of (the staff are supposed to watch her take her medications). The next morning, she saw the medications and took them, then took another dose when the nurse came by to give her morning medications. It was not realized until she’d already taken the medications and the staff noticed the medicine cup from the night before. My mom said she felt a little weak and dizzy for a few hours, but nothing significant, and she fully recovered. Interestingly, my mom mentioned it in passing, but no one called to let us know a medication error had occurred. Although she was not harmed, it made us, her family, lose a little trust in the facility because we found out about it indirectly, without any acknowledgement or apology.

On the other side of the equation, I have witnessed countless numbers of patient events in which providers feel worried and uncomfortable about the effects of disclosure with apology on themselves and their patients.

The bottom line is, disclosure with apology is needed and appreciated by patients, and it is absolutely the right thing to do. So download that cheesy Chicago song to your iPod and practice saying (or singing) “I’m sorry.” If the butler with chemicals can do it, so can we.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

It’s 1982, and in middle-school gyms across the country, among punch bowls and parental scrutiny, young girls and boys are slow-dancing with outstretched arms to a breathtaking song by the band Chicago. The song tells of the agonizing difficulty of apology, how despite the want and need to apologize, it is just too arduous.

Fast-forward 30 years, and it is hard to believe that cheesy No. 1 Billboard hit espoused the feelings that continue to haunt healthcare providers across the country: It’s hard for me to say I’m sorry.

Others Say It

If you look at the world around us, you see apology everywhere. Customer service representatives and customer-minded industries routinely let those words flow off their tongues with ease and grace.

While I was driving down the interstate last week, the number of traffic lanes shrunk from three to two to one. Anticipating widespread aggravation from weary travelers, the state transportation department deployed several large road signs every few miles; they read “WE APOLOGIZE FOR THE INCONVENIENCE … BEAR WITH US WHILE WE MAKE YOUR ROADS SMOOTHER AND SAFER.” Those simple messages made me feel like the congestion was not a senseless waste of time, that the state’s Department of Transportation was actually being strategic and thoughtful in their rationing of lanes during rush hour in the middle of the week.

Phone-based, customer-service departments figured out the simple apology a long time ago. While holding the line for a Lands’ End customer-service representative a few weeks ago, I heard, “We apologize for the delay. Your business is important to us. Please hold the line while we address callers ahead of you.” It validated for me that those phone representatives are not just sitting around eating lunch, completely ignoring my call, and that maybe there are others who procrastinated buying back-to-school backpacks until September—and just happened to call right before me.

I even got an apology at the dry cleaner. Amidst my last batch of clothes, my astute dry cleaner apparently found a very stubborn stain, which resisted all of their usual concoctions. It was on the back of a shirt and I probably would not have even noticed it was there. But nonetheless, they sent an apology tag, with a picture of a distraught butler who seemed to have struggled with that stain for hours.

Why Not Us?

So why is “sorry” so hard in healthcare? When things happen to patients, things that are inconvenient or downright dangerous, we have great difficulty in simply saying: “Hey, I am really sorry this happened to you,” or “I am so sorry you are still here. You must be really frustrated by our inefficiencies.”

I have the distinct pleasure of overseeing my hospital’s risk-management department for a few months. This means I get to see and hear what does and doesn’t happen to patients, which, at times, is misaligned with what should or shouldn’t happen to patients. When unanticipated events occur, the group launches into an investigation of what happened, why it happened, and the risk that it could happen again. After the initial dust settles and the facts are relayed from the care team to the risk-management team, the risk team always asks of those involved: “So what does the patient and their family know?” And we get a range of answers—some polished, some fumbled, some baffled.

The next question is: “Well, what should they know?” And that is always an easy question to answer. They should know the truth. Not just some of the truth, or half the truth, or a partial truth. Not what the care team thinks the patient “can handle.” They should just get the truth. To the best of the team’s ability, they should tell the patient:

- What (they think) happened;

- Why (they think) it happened;

- What it means for the patient; and

- What they are going to do to make it not happen again.

And then the patient (and family members) deserve an apology—sincere, compassionate, genuine. The apology should be the easy part, as most providers do not always know what happened, why it happened, or what they are going to do to prevent it from happening, but they usually truly do feel sorry that it happened at all.

“Sorry”=Positive Results

Patients are unanimous in their desire to be informed if a medical error has occurred; focus groups have found that patients believe such information would enhance their trust in their physicians and would reassure them that they were receiving complete information. And they want an apology.1

But interestingly, many physicians believe that full disclosure with apology is not warranted or appropriate, and that the apology could erode patient trust, might scare the patient, and might increase the risk of legal liability.1

There is little evidence that disclosure is harmful or detrimental, and there is some evidence that it is beneficial to the medical industry (i.e. reduces claims and litigation costs). A study published in 2010 from the University of Michigan Health System found a disclosure-with-compensation program was associated with a 36% reduction in new claims, a 65% reduction in lawsuits, and a 59% reduction in total liability cost.2

I have witnessed this phenomenon from both sides. My mother, who has Alzheimer’s and lives in an assisted-living facility, recently was given twice the dose of her medications one morning. She was “given” her night medications by being placed in her room, which she has no recollection of (the staff are supposed to watch her take her medications). The next morning, she saw the medications and took them, then took another dose when the nurse came by to give her morning medications. It was not realized until she’d already taken the medications and the staff noticed the medicine cup from the night before. My mom said she felt a little weak and dizzy for a few hours, but nothing significant, and she fully recovered. Interestingly, my mom mentioned it in passing, but no one called to let us know a medication error had occurred. Although she was not harmed, it made us, her family, lose a little trust in the facility because we found out about it indirectly, without any acknowledgement or apology.

On the other side of the equation, I have witnessed countless numbers of patient events in which providers feel worried and uncomfortable about the effects of disclosure with apology on themselves and their patients.

The bottom line is, disclosure with apology is needed and appreciated by patients, and it is absolutely the right thing to do. So download that cheesy Chicago song to your iPod and practice saying (or singing) “I’m sorry.” If the butler with chemicals can do it, so can we.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

It’s 1982, and in middle-school gyms across the country, among punch bowls and parental scrutiny, young girls and boys are slow-dancing with outstretched arms to a breathtaking song by the band Chicago. The song tells of the agonizing difficulty of apology, how despite the want and need to apologize, it is just too arduous.

Fast-forward 30 years, and it is hard to believe that cheesy No. 1 Billboard hit espoused the feelings that continue to haunt healthcare providers across the country: It’s hard for me to say I’m sorry.

Others Say It

If you look at the world around us, you see apology everywhere. Customer service representatives and customer-minded industries routinely let those words flow off their tongues with ease and grace.

While I was driving down the interstate last week, the number of traffic lanes shrunk from three to two to one. Anticipating widespread aggravation from weary travelers, the state transportation department deployed several large road signs every few miles; they read “WE APOLOGIZE FOR THE INCONVENIENCE … BEAR WITH US WHILE WE MAKE YOUR ROADS SMOOTHER AND SAFER.” Those simple messages made me feel like the congestion was not a senseless waste of time, that the state’s Department of Transportation was actually being strategic and thoughtful in their rationing of lanes during rush hour in the middle of the week.

Phone-based, customer-service departments figured out the simple apology a long time ago. While holding the line for a Lands’ End customer-service representative a few weeks ago, I heard, “We apologize for the delay. Your business is important to us. Please hold the line while we address callers ahead of you.” It validated for me that those phone representatives are not just sitting around eating lunch, completely ignoring my call, and that maybe there are others who procrastinated buying back-to-school backpacks until September—and just happened to call right before me.

I even got an apology at the dry cleaner. Amidst my last batch of clothes, my astute dry cleaner apparently found a very stubborn stain, which resisted all of their usual concoctions. It was on the back of a shirt and I probably would not have even noticed it was there. But nonetheless, they sent an apology tag, with a picture of a distraught butler who seemed to have struggled with that stain for hours.

Why Not Us?

So why is “sorry” so hard in healthcare? When things happen to patients, things that are inconvenient or downright dangerous, we have great difficulty in simply saying: “Hey, I am really sorry this happened to you,” or “I am so sorry you are still here. You must be really frustrated by our inefficiencies.”

I have the distinct pleasure of overseeing my hospital’s risk-management department for a few months. This means I get to see and hear what does and doesn’t happen to patients, which, at times, is misaligned with what should or shouldn’t happen to patients. When unanticipated events occur, the group launches into an investigation of what happened, why it happened, and the risk that it could happen again. After the initial dust settles and the facts are relayed from the care team to the risk-management team, the risk team always asks of those involved: “So what does the patient and their family know?” And we get a range of answers—some polished, some fumbled, some baffled.

The next question is: “Well, what should they know?” And that is always an easy question to answer. They should know the truth. Not just some of the truth, or half the truth, or a partial truth. Not what the care team thinks the patient “can handle.” They should just get the truth. To the best of the team’s ability, they should tell the patient:

- What (they think) happened;

- Why (they think) it happened;

- What it means for the patient; and

- What they are going to do to make it not happen again.

And then the patient (and family members) deserve an apology—sincere, compassionate, genuine. The apology should be the easy part, as most providers do not always know what happened, why it happened, or what they are going to do to prevent it from happening, but they usually truly do feel sorry that it happened at all.

“Sorry”=Positive Results

Patients are unanimous in their desire to be informed if a medical error has occurred; focus groups have found that patients believe such information would enhance their trust in their physicians and would reassure them that they were receiving complete information. And they want an apology.1

But interestingly, many physicians believe that full disclosure with apology is not warranted or appropriate, and that the apology could erode patient trust, might scare the patient, and might increase the risk of legal liability.1

There is little evidence that disclosure is harmful or detrimental, and there is some evidence that it is beneficial to the medical industry (i.e. reduces claims and litigation costs). A study published in 2010 from the University of Michigan Health System found a disclosure-with-compensation program was associated with a 36% reduction in new claims, a 65% reduction in lawsuits, and a 59% reduction in total liability cost.2

I have witnessed this phenomenon from both sides. My mother, who has Alzheimer’s and lives in an assisted-living facility, recently was given twice the dose of her medications one morning. She was “given” her night medications by being placed in her room, which she has no recollection of (the staff are supposed to watch her take her medications). The next morning, she saw the medications and took them, then took another dose when the nurse came by to give her morning medications. It was not realized until she’d already taken the medications and the staff noticed the medicine cup from the night before. My mom said she felt a little weak and dizzy for a few hours, but nothing significant, and she fully recovered. Interestingly, my mom mentioned it in passing, but no one called to let us know a medication error had occurred. Although she was not harmed, it made us, her family, lose a little trust in the facility because we found out about it indirectly, without any acknowledgement or apology.

On the other side of the equation, I have witnessed countless numbers of patient events in which providers feel worried and uncomfortable about the effects of disclosure with apology on themselves and their patients.

The bottom line is, disclosure with apology is needed and appreciated by patients, and it is absolutely the right thing to do. So download that cheesy Chicago song to your iPod and practice saying (or singing) “I’m sorry.” If the butler with chemicals can do it, so can we.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

References

- Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, Fraser VJ, Levinson W. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001-1007.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):213-221.

Why It's Hard for Healthcare Providers to Say I'm Sorry

Enter text here

Enter text here

Enter text here

John Nelson: Learning CPT Coding and Documentation Tricky for Hospitalists

There is a lot to learn when it comes to proper coding and the documentation requirements that go with it. It can even be tricky for a new residency grad to keep the difference in CPT and ICD-9 coding straight, to say nothing of the difference between documentation requirements for physician reimbursement versus hospital reimbursement. This column addresses only physician CPT coding (I’ll save documentation to support hospital billing for another column).

Although I believe that devoting the large number of brain cells required to keep this stuff straight gets in the way of maintaining necessary clinical knowledge, physicians have no real choice but to do it. (One could argue that having a professional coder read charts to determine proper CPT codes relieves a doctor of the burden of documentation and coding headaches. But this is only partially true. The doctor still needs to ensure that the documentation accurately reflects what was done for the coder to be able to select the appropriate codes, so he still needs to know a lot about this topic.)

All providers have a duty to reasonably ensure that submitted claims (bills) are true and accurate. Failing to document and code correctly risks anything from you or your employer having to return money, potentially with a penalty and interest, to being accused of criminal fraud.

Medicare and other payors generally categorize inaccurate claims as follows:

- Erroneous claims include inadvertent mistakes, innocent errors, or even negligence but still require payments associated with the error to be returned.

- Fraudulent claims are ones judged to be intentionally or recklessly false, and are subject to administrative or civil penalties, such as fines.

- Claims associated with criminal intent to defraud are subject to criminal penalties, which could include jail time.

While I haven’t heard of any hospitalists being accused of fraud, I know of several who have undergone audits and been required to return money. Whether your employer would refund the money or you would have to write a personal check to refund the money depends on your employment situation. For example, in most cases, the hospital would be liable to make the repayment for hospitalists it employs. If you’re an independent contractor, there is a good chance you could be stuck making the repayment yourself.

Trend: Increased Use of Higher-Level Codes

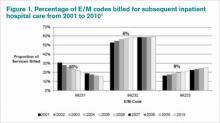

You might have missed it, but there was a recent study of Medicare Part B claims data from 2001 to 2010 showing that “physicians increased their billing of higher-level E/M codes in all types of E/M services.”1 For example, the report showed a steady decrease in use of the 99231 code, the lowest of the three subsequent inpatient hospital care codes, and an increase in the highest level code, 99233 (see Figure 1, below).

I can think of two reasons hospitalists might be increasing the use of higher codes. One, less-sick patients just aren’t seen in the hospital as often as they used to be, so the remaining patients require more intensive services, which could lead to the appropriate use of higher-level codes. Two, doctors have over the past 10 to 15 years invested more energy in learning appropriate documentation and coding, which might have led to correcting historical overuse of lower-level codes.

Did I tell you who conducted the study showing increased use of higher-level codes? It was the federal Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for preventing and detecting fraud and waste. Although the OIG might agree that the sicker patients and correction of historical undercoding might explain some of the trend, it’s a pretty safe bet they’re also concerned that a significant portion is inappropriate or fraudulent. Some portion of it probably is.

“CMS concurred with [OIG’s] recommendations to (1) continue to educate physicians on proper billing for E/M services and (2) encourage its contractor to review physicians’ billing for E/M services. CMS partially concurred with [OIG’s] third recommendation, to review physicians who bill higher-level E/M codes for appropriate action,” the OIG report noted.1

Plan for Education, Compliance

My sense is that most hospitalists employed by a large entity, such as a hospital or large medical group, have access to a certified coder to perform documentation and coding audits, as well as educational feedback when needed. If your practice doesn’t have access to a certified coder, you should consider photocopying some chart notes (e.g. 10 notes from each of your docs) and send them to an outside coder for an audit. Though they are very valuable, audits usually are not enough to ensure good performance.

In my March 2007 column, I described a reasonably simple chart audit allowing each doctor to compare his or her CPT coding pattern to everyone else in the group. You can compare your own coding to national coding patterns via SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine Report (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) or data from the CMS website, and the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) will have data in future surveys. Such comparisons might help uncover unusual patterns that are worthy of a closer look.

Other strategies to promote proper documentation and coding include online educational programs, such as:

- SHM’s CODE-H webinars (www.hospitalmedicine.org/codeh), which are available on demand for a fee;

- American Association of Professional Coders Evaluation and Management Online Training (http://www.aapc.com/training/evaluation-management-coding-training.aspx); and

- The American Health Information Management Association’s (AHIMA) Coding Basics Program (www.ahima.org/continuinged/campus/courseinfo/cb.aspx).

If you prefer, an Internet search can turn up in-person courses to learn documentation and coding. Additionally, your in-house or external coding auditors can provide training.