User login

V1: The most important lead in inferior STEMI

Q: Which would be the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pericarditis

- Acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction

- Anterior and inferior myocardial infarction

- None of the above

A: The correct answer is acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction.

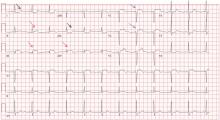

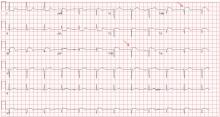

Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) evidenced by ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Hemodynamic instability or ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm in lead V1 raises the suspicion of right ventricular myocardial infarction. In such patients, the American Heart Association guidelines recommend electrocardiography with right-sided precordial leads.1

A 1-mm ST-segment elevation in the right precordial lead V4R is one of the most predictive electrocardiographic findings in right ventricular infarction.2 The electrocardiographic changes in this type of myocardial infarction may be transient and resolve within 10 hours in up to 48% of cases.3

Echocardiography can also be used to confirm the possibility of right ventricular infarction.

Q: Which clinical condition can occur as a complication of right ventricular myocardial infarction?

- Profound hypotension after nitrate administration

- High-degree heart block

- Atrial fibrillation

- All of the above

A: All of the conditions can occur.

Right ventricular involvement is very common, noted in up to 50% of patients with acute inferior STEMI in postmortem studies.4 However, hemodynamically significant right ventricular dysfunction is much less common.

Intravenous volume loading with normal saline is one of the first steps in the management of hypotension associated with right ventricular infarction. Patients with significant bradycardia or a high degree of atrioventricular block may require pacing. Early reperfusion should be achieved, if possible. Heightened suspicion is critical to the early diagnosis of this condition, since the prognosis is much worse than for isolated inferior STEMI.4

Our patient was found to have right coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al; American College of Cardiology. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004; 110:e82–e292.

- Robalino BD, Whitlow PL, Underwood DA, Salcedo EE. Electrocardiographic manifestations of right ventricular infarction. Am Heart J 1989; 118:138–144.

- Braat SH, Brugada P, de Zwaan C, Coenegracht JM, Wellens HJ. Value of electrocardiogram in diagnosing right ventricular involvement in patients with an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1983; 49:368–372.

- Zehender M, Kasper W, Kauder E, et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:981–988.

Q: Which would be the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pericarditis

- Acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction

- Anterior and inferior myocardial infarction

- None of the above

A: The correct answer is acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction.

Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) evidenced by ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Hemodynamic instability or ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm in lead V1 raises the suspicion of right ventricular myocardial infarction. In such patients, the American Heart Association guidelines recommend electrocardiography with right-sided precordial leads.1

A 1-mm ST-segment elevation in the right precordial lead V4R is one of the most predictive electrocardiographic findings in right ventricular infarction.2 The electrocardiographic changes in this type of myocardial infarction may be transient and resolve within 10 hours in up to 48% of cases.3

Echocardiography can also be used to confirm the possibility of right ventricular infarction.

Q: Which clinical condition can occur as a complication of right ventricular myocardial infarction?

- Profound hypotension after nitrate administration

- High-degree heart block

- Atrial fibrillation

- All of the above

A: All of the conditions can occur.

Right ventricular involvement is very common, noted in up to 50% of patients with acute inferior STEMI in postmortem studies.4 However, hemodynamically significant right ventricular dysfunction is much less common.

Intravenous volume loading with normal saline is one of the first steps in the management of hypotension associated with right ventricular infarction. Patients with significant bradycardia or a high degree of atrioventricular block may require pacing. Early reperfusion should be achieved, if possible. Heightened suspicion is critical to the early diagnosis of this condition, since the prognosis is much worse than for isolated inferior STEMI.4

Our patient was found to have right coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention.

Q: Which would be the most appropriate diagnosis?

- Pericarditis

- Acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction

- Anterior and inferior myocardial infarction

- None of the above

A: The correct answer is acute inferior and right ventricular myocardial infarction.

Her electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) evidenced by ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, and aVF. Hemodynamic instability or ST-segment elevation of more than 1 mm in lead V1 raises the suspicion of right ventricular myocardial infarction. In such patients, the American Heart Association guidelines recommend electrocardiography with right-sided precordial leads.1

A 1-mm ST-segment elevation in the right precordial lead V4R is one of the most predictive electrocardiographic findings in right ventricular infarction.2 The electrocardiographic changes in this type of myocardial infarction may be transient and resolve within 10 hours in up to 48% of cases.3

Echocardiography can also be used to confirm the possibility of right ventricular infarction.

Q: Which clinical condition can occur as a complication of right ventricular myocardial infarction?

- Profound hypotension after nitrate administration

- High-degree heart block

- Atrial fibrillation

- All of the above

A: All of the conditions can occur.

Right ventricular involvement is very common, noted in up to 50% of patients with acute inferior STEMI in postmortem studies.4 However, hemodynamically significant right ventricular dysfunction is much less common.

Intravenous volume loading with normal saline is one of the first steps in the management of hypotension associated with right ventricular infarction. Patients with significant bradycardia or a high degree of atrioventricular block may require pacing. Early reperfusion should be achieved, if possible. Heightened suspicion is critical to the early diagnosis of this condition, since the prognosis is much worse than for isolated inferior STEMI.4

Our patient was found to have right coronary artery disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al; American College of Cardiology. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004; 110:e82–e292.

- Robalino BD, Whitlow PL, Underwood DA, Salcedo EE. Electrocardiographic manifestations of right ventricular infarction. Am Heart J 1989; 118:138–144.

- Braat SH, Brugada P, de Zwaan C, Coenegracht JM, Wellens HJ. Value of electrocardiogram in diagnosing right ventricular involvement in patients with an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1983; 49:368–372.

- Zehender M, Kasper W, Kauder E, et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:981–988.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al; American College of Cardiology. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). Circulation 2004; 110:e82–e292.

- Robalino BD, Whitlow PL, Underwood DA, Salcedo EE. Electrocardiographic manifestations of right ventricular infarction. Am Heart J 1989; 118:138–144.

- Braat SH, Brugada P, de Zwaan C, Coenegracht JM, Wellens HJ. Value of electrocardiogram in diagnosing right ventricular involvement in patients with an acute inferior wall myocardial infarction. Br Heart J 1983; 49:368–372.

- Zehender M, Kasper W, Kauder E, et al. Right ventricular infarction as an independent predictor of prognosis after acute inferior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:981–988.

Home testing: The metamorphosis of attitudes about HIV infection

Most of us have not spent the past 25 years on the front line continuously managing HIV-infected patients, but I am sure that at various points in our lives we all have been touched by the AIDS epidemic. Whether comforting a woman with knee pain in the office who is crying over the impending death of her son who lives in a group home for men with AIDS, diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia in a college student only to realize it is the seminal manifestation of his HIV infection, pleading unsuccessfully with several neurosurgeons to get one to perform a brain biopsy on an “enhancing ring lesion” in a young gay opera singer, or being part of a team caring for a gouty patient with AIDS and hepatitis C who had just undergone a successful liver transplantation, we all have our stories with resultant reflections on the era of medicine in which we practice.

In July 2012, the New York Times described the new home test for HIV infection as part of “the normalization of a disease once seen as a mark of shame.”1 As with home pregnancy testing, people can now self-manage their need to know about what is going on in their body. But HIV goes so much deeper than this: it has been and remains a metaphor for and a reflection of many of the social issues that permeate our current political and social environment.

The politics and the social reactions to testing for HIV over the years since the virus was recognized in 1983–1984 is stuff for sociopsychologic treatises. Antibody testing was available in 1985, but in the absence of treatment, to test was simply to deliver a death sentence. Plus, with a diagnosis of AIDS, there would be no dental care, no insurance, no renting of an apartment, and perhaps no job. For some, family ties would be broken as closet doors would be thrown open, revealing a now unrecognized visage wearing the “mark of shame.” Some gay advocates rallied hard against testing, since anonymity and social protection for the infected could not be assured, a pragmatic response to blatant discrimination. In 1987, the first home test for HIV was in development, but—no surprise—there was no need for it.

As early treatments such as zidovudine (AZT) appeared and the value of specific antibiotic prophylaxis was demonstrated, there was some initial hope for treatment, and thus testing made medical sense. The size of the population infected (we were looking at the tip of the iceberg) was also being realized, so testing appealed to the social consciousness—try to limit infection. But discrimination wasn’t gone, and the politics of the time couldn’t quite handle all of the implications of a rapidly growing epidemic. America wasn’t ready for clean-needle-exchange programs, promotion of condom use, or open discussion of gay lifestyles. The Reagan White House was initially dead silent, except for proposing to limit entrance of potentially infected immigrants and promoting abstinence as the ideal protective approach.

Social righteousness took some hold, and protection of patient anonymity and autonomy became of paramount importance. But unintended consequences turned out to include limitation of testing: laws were written to require that HIV testing be accompanied by “appropriate,” stringently defined counseling, something that wasn’t always feasible. Patients needed to sign a release to be tested (“opt in”); many just said no. This tied the hands of physicians, so we developed work-arounds: we checked lymphocyte counts and CD4 counts to help us take care of patients too afraid to let us test for HIV directly.

Finally, in 2006, as therapies began to become increasingly effective and more data started to accumulate regarding the benefits of early antiretroviral therapy, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended routine testing for all patients entering most acute health care facilities, unless they would actively decline (“opt out”). We have still not hit full stride in implementing universal testing for HIV. Nor have we hit our stride on fully accepting all demographic segments of the population. In some communities, HIV infection is still equivalent to the scarlet letter of Hester Prynne, not just because of the disease itself but because of the lifestyle it implies. Legislating laboratory testing practices cannot change all social attitudes. But maybe, hopefully, it is another step.

Dr. Christine Koval in this issue of the Journal discusses the practical use of the newly approved home HIV test. It is a short article, but it took a very, very long time for social and political forces to be modestly aligned sufficiently for there to be anything to write about. Since perhaps 18% of HIV-infected Americans are unaware of their infection, maybe some TV ads for this test, wedged between the ads for treating erectile dysfunction, can indeed bring (as the New York Times described) further “normalization” to the approach to managing HIV-infected patients.

- McNeil DG. Rapid HIV home test wins federal approval. The New York Times 2012 July 3. www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed September 12, 2012.

Most of us have not spent the past 25 years on the front line continuously managing HIV-infected patients, but I am sure that at various points in our lives we all have been touched by the AIDS epidemic. Whether comforting a woman with knee pain in the office who is crying over the impending death of her son who lives in a group home for men with AIDS, diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia in a college student only to realize it is the seminal manifestation of his HIV infection, pleading unsuccessfully with several neurosurgeons to get one to perform a brain biopsy on an “enhancing ring lesion” in a young gay opera singer, or being part of a team caring for a gouty patient with AIDS and hepatitis C who had just undergone a successful liver transplantation, we all have our stories with resultant reflections on the era of medicine in which we practice.

In July 2012, the New York Times described the new home test for HIV infection as part of “the normalization of a disease once seen as a mark of shame.”1 As with home pregnancy testing, people can now self-manage their need to know about what is going on in their body. But HIV goes so much deeper than this: it has been and remains a metaphor for and a reflection of many of the social issues that permeate our current political and social environment.

The politics and the social reactions to testing for HIV over the years since the virus was recognized in 1983–1984 is stuff for sociopsychologic treatises. Antibody testing was available in 1985, but in the absence of treatment, to test was simply to deliver a death sentence. Plus, with a diagnosis of AIDS, there would be no dental care, no insurance, no renting of an apartment, and perhaps no job. For some, family ties would be broken as closet doors would be thrown open, revealing a now unrecognized visage wearing the “mark of shame.” Some gay advocates rallied hard against testing, since anonymity and social protection for the infected could not be assured, a pragmatic response to blatant discrimination. In 1987, the first home test for HIV was in development, but—no surprise—there was no need for it.

As early treatments such as zidovudine (AZT) appeared and the value of specific antibiotic prophylaxis was demonstrated, there was some initial hope for treatment, and thus testing made medical sense. The size of the population infected (we were looking at the tip of the iceberg) was also being realized, so testing appealed to the social consciousness—try to limit infection. But discrimination wasn’t gone, and the politics of the time couldn’t quite handle all of the implications of a rapidly growing epidemic. America wasn’t ready for clean-needle-exchange programs, promotion of condom use, or open discussion of gay lifestyles. The Reagan White House was initially dead silent, except for proposing to limit entrance of potentially infected immigrants and promoting abstinence as the ideal protective approach.

Social righteousness took some hold, and protection of patient anonymity and autonomy became of paramount importance. But unintended consequences turned out to include limitation of testing: laws were written to require that HIV testing be accompanied by “appropriate,” stringently defined counseling, something that wasn’t always feasible. Patients needed to sign a release to be tested (“opt in”); many just said no. This tied the hands of physicians, so we developed work-arounds: we checked lymphocyte counts and CD4 counts to help us take care of patients too afraid to let us test for HIV directly.

Finally, in 2006, as therapies began to become increasingly effective and more data started to accumulate regarding the benefits of early antiretroviral therapy, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended routine testing for all patients entering most acute health care facilities, unless they would actively decline (“opt out”). We have still not hit full stride in implementing universal testing for HIV. Nor have we hit our stride on fully accepting all demographic segments of the population. In some communities, HIV infection is still equivalent to the scarlet letter of Hester Prynne, not just because of the disease itself but because of the lifestyle it implies. Legislating laboratory testing practices cannot change all social attitudes. But maybe, hopefully, it is another step.

Dr. Christine Koval in this issue of the Journal discusses the practical use of the newly approved home HIV test. It is a short article, but it took a very, very long time for social and political forces to be modestly aligned sufficiently for there to be anything to write about. Since perhaps 18% of HIV-infected Americans are unaware of their infection, maybe some TV ads for this test, wedged between the ads for treating erectile dysfunction, can indeed bring (as the New York Times described) further “normalization” to the approach to managing HIV-infected patients.

Most of us have not spent the past 25 years on the front line continuously managing HIV-infected patients, but I am sure that at various points in our lives we all have been touched by the AIDS epidemic. Whether comforting a woman with knee pain in the office who is crying over the impending death of her son who lives in a group home for men with AIDS, diagnosing immune thrombocytopenia in a college student only to realize it is the seminal manifestation of his HIV infection, pleading unsuccessfully with several neurosurgeons to get one to perform a brain biopsy on an “enhancing ring lesion” in a young gay opera singer, or being part of a team caring for a gouty patient with AIDS and hepatitis C who had just undergone a successful liver transplantation, we all have our stories with resultant reflections on the era of medicine in which we practice.

In July 2012, the New York Times described the new home test for HIV infection as part of “the normalization of a disease once seen as a mark of shame.”1 As with home pregnancy testing, people can now self-manage their need to know about what is going on in their body. But HIV goes so much deeper than this: it has been and remains a metaphor for and a reflection of many of the social issues that permeate our current political and social environment.

The politics and the social reactions to testing for HIV over the years since the virus was recognized in 1983–1984 is stuff for sociopsychologic treatises. Antibody testing was available in 1985, but in the absence of treatment, to test was simply to deliver a death sentence. Plus, with a diagnosis of AIDS, there would be no dental care, no insurance, no renting of an apartment, and perhaps no job. For some, family ties would be broken as closet doors would be thrown open, revealing a now unrecognized visage wearing the “mark of shame.” Some gay advocates rallied hard against testing, since anonymity and social protection for the infected could not be assured, a pragmatic response to blatant discrimination. In 1987, the first home test for HIV was in development, but—no surprise—there was no need for it.

As early treatments such as zidovudine (AZT) appeared and the value of specific antibiotic prophylaxis was demonstrated, there was some initial hope for treatment, and thus testing made medical sense. The size of the population infected (we were looking at the tip of the iceberg) was also being realized, so testing appealed to the social consciousness—try to limit infection. But discrimination wasn’t gone, and the politics of the time couldn’t quite handle all of the implications of a rapidly growing epidemic. America wasn’t ready for clean-needle-exchange programs, promotion of condom use, or open discussion of gay lifestyles. The Reagan White House was initially dead silent, except for proposing to limit entrance of potentially infected immigrants and promoting abstinence as the ideal protective approach.

Social righteousness took some hold, and protection of patient anonymity and autonomy became of paramount importance. But unintended consequences turned out to include limitation of testing: laws were written to require that HIV testing be accompanied by “appropriate,” stringently defined counseling, something that wasn’t always feasible. Patients needed to sign a release to be tested (“opt in”); many just said no. This tied the hands of physicians, so we developed work-arounds: we checked lymphocyte counts and CD4 counts to help us take care of patients too afraid to let us test for HIV directly.

Finally, in 2006, as therapies began to become increasingly effective and more data started to accumulate regarding the benefits of early antiretroviral therapy, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended routine testing for all patients entering most acute health care facilities, unless they would actively decline (“opt out”). We have still not hit full stride in implementing universal testing for HIV. Nor have we hit our stride on fully accepting all demographic segments of the population. In some communities, HIV infection is still equivalent to the scarlet letter of Hester Prynne, not just because of the disease itself but because of the lifestyle it implies. Legislating laboratory testing practices cannot change all social attitudes. But maybe, hopefully, it is another step.

Dr. Christine Koval in this issue of the Journal discusses the practical use of the newly approved home HIV test. It is a short article, but it took a very, very long time for social and political forces to be modestly aligned sufficiently for there to be anything to write about. Since perhaps 18% of HIV-infected Americans are unaware of their infection, maybe some TV ads for this test, wedged between the ads for treating erectile dysfunction, can indeed bring (as the New York Times described) further “normalization” to the approach to managing HIV-infected patients.

- McNeil DG. Rapid HIV home test wins federal approval. The New York Times 2012 July 3. www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed September 12, 2012.

- McNeil DG. Rapid HIV home test wins federal approval. The New York Times 2012 July 3. www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed September 12, 2012.

Home testing for HIV: Hopefully, a step forward

In July 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter test kit for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA). This test is a variation of the currently available OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test used in clinical settings by trained personnel for rapid detection of HIV.

The home HIV test is expected to become available in the fall of 2012 from the company’s Web site and at retail drugstores. This will put the power of HIV testing into the hands of anyone able to afford the estimated $60 price and willing to purchase the item online or in stores.

GOAL: TO REDUCE THE NUMBER OF INFECTED PEOPLE WHO ARE UNAWARE

How home testing will change the demographics of HIV testing is not clear, but the intention is to reduce the number of HIV-infected people who are unaware of their infection and to get them in for care. Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has called the new test a “positive step forward” in bringing the HIV epidemic under control.1

Recent figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that, of the 1.2 million HIV-infected people in the United States, up to 220,000 are unaware of their infection.2,3 Since antiretroviral therapy is now considered beneficial even in the early stages of HIV infection, those who are unaware of their infection are missing an opportunity for the most effective therapies.

They may also be unknowingly transmitting the virus, thus perpetuating the HIV epidemic. Awareness of one’s HIV infection may lead to behavioral changes that can reduce the risk of transmission. It has also become clear that antiretroviral therapy can dramatically reduce transmission rates, a concept known as “treatment as prevention.” 4 Thus, access to care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy have the potential to prevent progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the individual and to interrupt the spread of the virus in the community.

There are several steps between awareness of HIV infection and full engagement in HIV care that require attention from the health care community.5 Only a quarter of those with known HIV infection are in care and adherent to antiretroviral therapy, leaving much work to be done on removing barriers to effective treatment.5 The first step is still to identify those infected. The effort to increase the percentage of HIV-infected individuals who know their HIV status is one of the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and HealthyPeople2020.6

HOW THE TEST IS USED

The OraQuick In-Home Test consists of the device and reagents, instructional materials, information on interpreting the results, and contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center for information, support, and local medical referral.7 The overall time needed for testing is 20 to 40 minutes.

To perform the test, an oral fluid specimen is collected by swabbing the upper and lower buccal mucosa along the gum line. Once inserted into the developer solution the swabbed sample is carried onto a membrane strip containing HIV-1/2 antigens.

The device has two windows, one labelled “T” (for test) and the other labelled “C” (for control). If the patient has sufficient antibodies to HIV proteins, the “T” window indicates a positive result if a band is visible. The “C” (control) window displays a band to indicate if the device and reagents are working. If the control window does not show a band, then the kit has not functioned properly and the test result is not reliable.

SOME PEOPLE MAY STILL NEED HELP

For the test to succeed in informing people of their HIV status, it must be used effectively and the results must be interpretable. Of 5,662 participants in phase III investigational-device studies, 99% were able to use the kit and determine a result.7 While the test’s simplicity is similar to that of pregnancy test kits, it is possible that some people (at least 1% of those using the kit) may seek guidance from medical practitioners because they are unable to understand the test results.

For a test result to have the desired outcome of leading to HIV care, individuals must act on a positive result. When home test results are positive, the instructions indicate that “you may have HIV” and provide contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center. It is unclear how reliable the counseling, information, and referral process from OraSure will be and if people will use the service.

Individuals may access medical care at a variety of levels for further assistance if they have a positive test result. These may include primary care offices, emergency and urgent care settings, health departments, and HIV clinics.

LESS SENSITIVE THAN BLOOD TESTS

To provide additional care, clinicians must understand the performance of the home HIV test. Most importantly, the test result must be confirmed.

The In-Home test is less sensitive than currently available HIV blood tests used in the clinical setting, particularly the HIV-1/2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with confirmatory Western blot testing. The In-Home test is less likely to detect HIV infection during the 90-day “window period” when seroconversion is occurring, and so it should not be relied on to rule out HIV during this early period after infection.

The sensitivity and specificity of the OraQuick In-Home HIV test were determined in a phase III trial in 5,662 people (80% at risk of HIV), who were tested concurrently with the “gold standard” blood tests (EIA and Western blot). The sensitivity was 93% (giving a positive result in 106 of 114 patients who had a positive result on blood testing), and the specificity was 99.9% (giving a negative result in 5,384 of 5,385 patients who had a negative result on blood testing).7

Therefore, a positive In-Home test result is likely to be truly positive, but a negative result is not as reliably truly negative. False-negative results may occur particularly in the window period early after HIV infection, so the test should not be relied on within 90 days of high-risk behavior. In contrast, with the fourth-generation blood HIV tests, the window period is approximately 16 days.

The predictive value of the test will depend on the population using it and on the patient’s pretest probability of disease at the time of testing. In the population tested by OraQuick, the positive predictive value was 99.1% and the negative predictive value was 99.9%.7 Mathematical modeling has been done to examine the potential outcomes for use in subpopulations at lower risk and at higher risk.

As clinicians, we will have to address the potential for both false-positive and false-negative test results. False-positive results may be more likely in low-risk populations and may occur in the setting of cross-reactive antibodies from pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, or previous receipt of an experimental HIV vaccination. False-negative results may occur in the setting of acute HIV infection and in those with severely impaired immunity (eg, from agammaglobulinemia or immunosuppressive drugs) and will be more likely in higher-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, blacks, and Hispanics ages 18 to 35 with multiple sexual partners. A positive In-Home HIV test should be followed up with a blood EIA and confirmed with Western blot in all patients.

WHO WILL USE THIS TEST?

It is unclear who will use this new test. In OraSure’s clinical trial, the percentages of people who indicated they would “definitely or probably buy” the test were:

- 20% of the general population

- 27% of those ages 18 to 35

- 49% of blacks ages 18 to 35

- 47% of homosexual men

- 43% of people who said they had more than two sexual partners per year

- 32% who said they use condoms inconsistently.

If this is true, the test may appropriately target several populations that are not currently being tested, either because they lack access to care or because they do not see themselves as being at high risk. Of those with newly diagnosed HIV infection from 2006 to 2009, 40% had had no prior testing, and the groups with the highest percentages of people in this category were black, men with injection drug use as their sole risk factor, those older than 50 years, and those with heterosexual contact as their sole risk factor.8 Because of difficulties in identifying some of these groups as “at risk,” the current CDC guidelines recommend that HIV testing be offered to all patients ages 13 to 64, regardless of their risk factors.9

The home HIV test may fill a gap in testing, extending it to those still not tested in the health care setting or to those who have not sought health care. For the home test to fill that gap, people still have to perceive themselves as at risk and then purchase the test. Through public health strategies and at clinical points of care, we must continue to inform our patients about HIV risk and work to identify new or ongoing risk factors that would prompt additional testing.

MANY QUESTIONS REMAIN

- Will those who need testing want to use this test? People will buy the test only if they perceive themselves to be at risk.

- Is this test affordable for the target populations? $60 will be unaffordable to some.

- Will the directions be followed effectively?

- Will home testing reduce opportunities to counsel patients on their HIV risk factors?

- Will there be situations in which individuals are socially pressured to take the test?

- Can users of the test expect the appropriate amount of privacy? Availability on the Internet and in drug stores is not a guarantee of privacy when purchasing the test, although the result presumably will not be known.

- Will those with positive results seek medical care?

- Will those with negative results who are still at high risk forgo more sensitive testing and continue to engage in high-risk activities?

Nevertheless, since early and continued treatment prevents disease progression and reduces HIV transmission, testing is the first step toward access to effective HIV care. The home HIV test is a step forward in providing high-quality HIV testing to the wider population.

- McNeil DG. Rapid H.I.V. Home Test Wins Federal Approval. New York Times, July 3, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data—United States and 6 US Dependent Areas—2010 HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Volume 17, Number 3 (Part A). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010supp_vol-17no3/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2010 HIV Surveillance Report, Volume 22. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Attia S, Egger M, Müller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2009; 23:1397–1404.

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:793–800.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy People 2020 Summary of Objectives. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HIV.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 102nd Meeting of The Blood Product Advisory Committee (BPAC). Evaluation of the Safety and Effectiveness of the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test. May 15, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Previous HIV testing among adults and adolescents newly diagnosed with HIV infection—National HIV Surveillance System, 18 jurisdictions, United States, 2006–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:441–445.

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–17.

In July 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter test kit for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA). This test is a variation of the currently available OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test used in clinical settings by trained personnel for rapid detection of HIV.

The home HIV test is expected to become available in the fall of 2012 from the company’s Web site and at retail drugstores. This will put the power of HIV testing into the hands of anyone able to afford the estimated $60 price and willing to purchase the item online or in stores.

GOAL: TO REDUCE THE NUMBER OF INFECTED PEOPLE WHO ARE UNAWARE

How home testing will change the demographics of HIV testing is not clear, but the intention is to reduce the number of HIV-infected people who are unaware of their infection and to get them in for care. Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has called the new test a “positive step forward” in bringing the HIV epidemic under control.1

Recent figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that, of the 1.2 million HIV-infected people in the United States, up to 220,000 are unaware of their infection.2,3 Since antiretroviral therapy is now considered beneficial even in the early stages of HIV infection, those who are unaware of their infection are missing an opportunity for the most effective therapies.

They may also be unknowingly transmitting the virus, thus perpetuating the HIV epidemic. Awareness of one’s HIV infection may lead to behavioral changes that can reduce the risk of transmission. It has also become clear that antiretroviral therapy can dramatically reduce transmission rates, a concept known as “treatment as prevention.” 4 Thus, access to care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy have the potential to prevent progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the individual and to interrupt the spread of the virus in the community.

There are several steps between awareness of HIV infection and full engagement in HIV care that require attention from the health care community.5 Only a quarter of those with known HIV infection are in care and adherent to antiretroviral therapy, leaving much work to be done on removing barriers to effective treatment.5 The first step is still to identify those infected. The effort to increase the percentage of HIV-infected individuals who know their HIV status is one of the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and HealthyPeople2020.6

HOW THE TEST IS USED

The OraQuick In-Home Test consists of the device and reagents, instructional materials, information on interpreting the results, and contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center for information, support, and local medical referral.7 The overall time needed for testing is 20 to 40 minutes.

To perform the test, an oral fluid specimen is collected by swabbing the upper and lower buccal mucosa along the gum line. Once inserted into the developer solution the swabbed sample is carried onto a membrane strip containing HIV-1/2 antigens.

The device has two windows, one labelled “T” (for test) and the other labelled “C” (for control). If the patient has sufficient antibodies to HIV proteins, the “T” window indicates a positive result if a band is visible. The “C” (control) window displays a band to indicate if the device and reagents are working. If the control window does not show a band, then the kit has not functioned properly and the test result is not reliable.

SOME PEOPLE MAY STILL NEED HELP

For the test to succeed in informing people of their HIV status, it must be used effectively and the results must be interpretable. Of 5,662 participants in phase III investigational-device studies, 99% were able to use the kit and determine a result.7 While the test’s simplicity is similar to that of pregnancy test kits, it is possible that some people (at least 1% of those using the kit) may seek guidance from medical practitioners because they are unable to understand the test results.

For a test result to have the desired outcome of leading to HIV care, individuals must act on a positive result. When home test results are positive, the instructions indicate that “you may have HIV” and provide contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center. It is unclear how reliable the counseling, information, and referral process from OraSure will be and if people will use the service.

Individuals may access medical care at a variety of levels for further assistance if they have a positive test result. These may include primary care offices, emergency and urgent care settings, health departments, and HIV clinics.

LESS SENSITIVE THAN BLOOD TESTS

To provide additional care, clinicians must understand the performance of the home HIV test. Most importantly, the test result must be confirmed.

The In-Home test is less sensitive than currently available HIV blood tests used in the clinical setting, particularly the HIV-1/2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with confirmatory Western blot testing. The In-Home test is less likely to detect HIV infection during the 90-day “window period” when seroconversion is occurring, and so it should not be relied on to rule out HIV during this early period after infection.

The sensitivity and specificity of the OraQuick In-Home HIV test were determined in a phase III trial in 5,662 people (80% at risk of HIV), who were tested concurrently with the “gold standard” blood tests (EIA and Western blot). The sensitivity was 93% (giving a positive result in 106 of 114 patients who had a positive result on blood testing), and the specificity was 99.9% (giving a negative result in 5,384 of 5,385 patients who had a negative result on blood testing).7

Therefore, a positive In-Home test result is likely to be truly positive, but a negative result is not as reliably truly negative. False-negative results may occur particularly in the window period early after HIV infection, so the test should not be relied on within 90 days of high-risk behavior. In contrast, with the fourth-generation blood HIV tests, the window period is approximately 16 days.

The predictive value of the test will depend on the population using it and on the patient’s pretest probability of disease at the time of testing. In the population tested by OraQuick, the positive predictive value was 99.1% and the negative predictive value was 99.9%.7 Mathematical modeling has been done to examine the potential outcomes for use in subpopulations at lower risk and at higher risk.

As clinicians, we will have to address the potential for both false-positive and false-negative test results. False-positive results may be more likely in low-risk populations and may occur in the setting of cross-reactive antibodies from pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, or previous receipt of an experimental HIV vaccination. False-negative results may occur in the setting of acute HIV infection and in those with severely impaired immunity (eg, from agammaglobulinemia or immunosuppressive drugs) and will be more likely in higher-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, blacks, and Hispanics ages 18 to 35 with multiple sexual partners. A positive In-Home HIV test should be followed up with a blood EIA and confirmed with Western blot in all patients.

WHO WILL USE THIS TEST?

It is unclear who will use this new test. In OraSure’s clinical trial, the percentages of people who indicated they would “definitely or probably buy” the test were:

- 20% of the general population

- 27% of those ages 18 to 35

- 49% of blacks ages 18 to 35

- 47% of homosexual men

- 43% of people who said they had more than two sexual partners per year

- 32% who said they use condoms inconsistently.

If this is true, the test may appropriately target several populations that are not currently being tested, either because they lack access to care or because they do not see themselves as being at high risk. Of those with newly diagnosed HIV infection from 2006 to 2009, 40% had had no prior testing, and the groups with the highest percentages of people in this category were black, men with injection drug use as their sole risk factor, those older than 50 years, and those with heterosexual contact as their sole risk factor.8 Because of difficulties in identifying some of these groups as “at risk,” the current CDC guidelines recommend that HIV testing be offered to all patients ages 13 to 64, regardless of their risk factors.9

The home HIV test may fill a gap in testing, extending it to those still not tested in the health care setting or to those who have not sought health care. For the home test to fill that gap, people still have to perceive themselves as at risk and then purchase the test. Through public health strategies and at clinical points of care, we must continue to inform our patients about HIV risk and work to identify new or ongoing risk factors that would prompt additional testing.

MANY QUESTIONS REMAIN

- Will those who need testing want to use this test? People will buy the test only if they perceive themselves to be at risk.

- Is this test affordable for the target populations? $60 will be unaffordable to some.

- Will the directions be followed effectively?

- Will home testing reduce opportunities to counsel patients on their HIV risk factors?

- Will there be situations in which individuals are socially pressured to take the test?

- Can users of the test expect the appropriate amount of privacy? Availability on the Internet and in drug stores is not a guarantee of privacy when purchasing the test, although the result presumably will not be known.

- Will those with positive results seek medical care?

- Will those with negative results who are still at high risk forgo more sensitive testing and continue to engage in high-risk activities?

Nevertheless, since early and continued treatment prevents disease progression and reduces HIV transmission, testing is the first step toward access to effective HIV care. The home HIV test is a step forward in providing high-quality HIV testing to the wider population.

In July 2012, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first over-the-counter test kit for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA). This test is a variation of the currently available OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Test used in clinical settings by trained personnel for rapid detection of HIV.

The home HIV test is expected to become available in the fall of 2012 from the company’s Web site and at retail drugstores. This will put the power of HIV testing into the hands of anyone able to afford the estimated $60 price and willing to purchase the item online or in stores.

GOAL: TO REDUCE THE NUMBER OF INFECTED PEOPLE WHO ARE UNAWARE

How home testing will change the demographics of HIV testing is not clear, but the intention is to reduce the number of HIV-infected people who are unaware of their infection and to get them in for care. Anthony Fauci, MD, the director of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has called the new test a “positive step forward” in bringing the HIV epidemic under control.1

Recent figures from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that, of the 1.2 million HIV-infected people in the United States, up to 220,000 are unaware of their infection.2,3 Since antiretroviral therapy is now considered beneficial even in the early stages of HIV infection, those who are unaware of their infection are missing an opportunity for the most effective therapies.

They may also be unknowingly transmitting the virus, thus perpetuating the HIV epidemic. Awareness of one’s HIV infection may lead to behavioral changes that can reduce the risk of transmission. It has also become clear that antiretroviral therapy can dramatically reduce transmission rates, a concept known as “treatment as prevention.” 4 Thus, access to care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy have the potential to prevent progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in the individual and to interrupt the spread of the virus in the community.

There are several steps between awareness of HIV infection and full engagement in HIV care that require attention from the health care community.5 Only a quarter of those with known HIV infection are in care and adherent to antiretroviral therapy, leaving much work to be done on removing barriers to effective treatment.5 The first step is still to identify those infected. The effort to increase the percentage of HIV-infected individuals who know their HIV status is one of the goals of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy and HealthyPeople2020.6

HOW THE TEST IS USED

The OraQuick In-Home Test consists of the device and reagents, instructional materials, information on interpreting the results, and contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center for information, support, and local medical referral.7 The overall time needed for testing is 20 to 40 minutes.

To perform the test, an oral fluid specimen is collected by swabbing the upper and lower buccal mucosa along the gum line. Once inserted into the developer solution the swabbed sample is carried onto a membrane strip containing HIV-1/2 antigens.

The device has two windows, one labelled “T” (for test) and the other labelled “C” (for control). If the patient has sufficient antibodies to HIV proteins, the “T” window indicates a positive result if a band is visible. The “C” (control) window displays a band to indicate if the device and reagents are working. If the control window does not show a band, then the kit has not functioned properly and the test result is not reliable.

SOME PEOPLE MAY STILL NEED HELP

For the test to succeed in informing people of their HIV status, it must be used effectively and the results must be interpretable. Of 5,662 participants in phase III investigational-device studies, 99% were able to use the kit and determine a result.7 While the test’s simplicity is similar to that of pregnancy test kits, it is possible that some people (at least 1% of those using the kit) may seek guidance from medical practitioners because they are unable to understand the test results.

For a test result to have the desired outcome of leading to HIV care, individuals must act on a positive result. When home test results are positive, the instructions indicate that “you may have HIV” and provide contact information for the OraQuick Answer Center. It is unclear how reliable the counseling, information, and referral process from OraSure will be and if people will use the service.

Individuals may access medical care at a variety of levels for further assistance if they have a positive test result. These may include primary care offices, emergency and urgent care settings, health departments, and HIV clinics.

LESS SENSITIVE THAN BLOOD TESTS

To provide additional care, clinicians must understand the performance of the home HIV test. Most importantly, the test result must be confirmed.

The In-Home test is less sensitive than currently available HIV blood tests used in the clinical setting, particularly the HIV-1/2 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) with confirmatory Western blot testing. The In-Home test is less likely to detect HIV infection during the 90-day “window period” when seroconversion is occurring, and so it should not be relied on to rule out HIV during this early period after infection.

The sensitivity and specificity of the OraQuick In-Home HIV test were determined in a phase III trial in 5,662 people (80% at risk of HIV), who were tested concurrently with the “gold standard” blood tests (EIA and Western blot). The sensitivity was 93% (giving a positive result in 106 of 114 patients who had a positive result on blood testing), and the specificity was 99.9% (giving a negative result in 5,384 of 5,385 patients who had a negative result on blood testing).7

Therefore, a positive In-Home test result is likely to be truly positive, but a negative result is not as reliably truly negative. False-negative results may occur particularly in the window period early after HIV infection, so the test should not be relied on within 90 days of high-risk behavior. In contrast, with the fourth-generation blood HIV tests, the window period is approximately 16 days.

The predictive value of the test will depend on the population using it and on the patient’s pretest probability of disease at the time of testing. In the population tested by OraQuick, the positive predictive value was 99.1% and the negative predictive value was 99.9%.7 Mathematical modeling has been done to examine the potential outcomes for use in subpopulations at lower risk and at higher risk.

As clinicians, we will have to address the potential for both false-positive and false-negative test results. False-positive results may be more likely in low-risk populations and may occur in the setting of cross-reactive antibodies from pregnancy, autoimmune diseases, or previous receipt of an experimental HIV vaccination. False-negative results may occur in the setting of acute HIV infection and in those with severely impaired immunity (eg, from agammaglobulinemia or immunosuppressive drugs) and will be more likely in higher-risk populations, such as men who have sex with men, intravenous drug users, blacks, and Hispanics ages 18 to 35 with multiple sexual partners. A positive In-Home HIV test should be followed up with a blood EIA and confirmed with Western blot in all patients.

WHO WILL USE THIS TEST?

It is unclear who will use this new test. In OraSure’s clinical trial, the percentages of people who indicated they would “definitely or probably buy” the test were:

- 20% of the general population

- 27% of those ages 18 to 35

- 49% of blacks ages 18 to 35

- 47% of homosexual men

- 43% of people who said they had more than two sexual partners per year

- 32% who said they use condoms inconsistently.

If this is true, the test may appropriately target several populations that are not currently being tested, either because they lack access to care or because they do not see themselves as being at high risk. Of those with newly diagnosed HIV infection from 2006 to 2009, 40% had had no prior testing, and the groups with the highest percentages of people in this category were black, men with injection drug use as their sole risk factor, those older than 50 years, and those with heterosexual contact as their sole risk factor.8 Because of difficulties in identifying some of these groups as “at risk,” the current CDC guidelines recommend that HIV testing be offered to all patients ages 13 to 64, regardless of their risk factors.9

The home HIV test may fill a gap in testing, extending it to those still not tested in the health care setting or to those who have not sought health care. For the home test to fill that gap, people still have to perceive themselves as at risk and then purchase the test. Through public health strategies and at clinical points of care, we must continue to inform our patients about HIV risk and work to identify new or ongoing risk factors that would prompt additional testing.

MANY QUESTIONS REMAIN

- Will those who need testing want to use this test? People will buy the test only if they perceive themselves to be at risk.

- Is this test affordable for the target populations? $60 will be unaffordable to some.

- Will the directions be followed effectively?

- Will home testing reduce opportunities to counsel patients on their HIV risk factors?

- Will there be situations in which individuals are socially pressured to take the test?

- Can users of the test expect the appropriate amount of privacy? Availability on the Internet and in drug stores is not a guarantee of privacy when purchasing the test, although the result presumably will not be known.

- Will those with positive results seek medical care?

- Will those with negative results who are still at high risk forgo more sensitive testing and continue to engage in high-risk activities?

Nevertheless, since early and continued treatment prevents disease progression and reduces HIV transmission, testing is the first step toward access to effective HIV care. The home HIV test is a step forward in providing high-quality HIV testing to the wider population.

- McNeil DG. Rapid H.I.V. Home Test Wins Federal Approval. New York Times, July 3, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data—United States and 6 US Dependent Areas—2010 HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Volume 17, Number 3 (Part A). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010supp_vol-17no3/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2010 HIV Surveillance Report, Volume 22. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Attia S, Egger M, Müller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2009; 23:1397–1404.

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:793–800.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy People 2020 Summary of Objectives. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HIV.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 102nd Meeting of The Blood Product Advisory Committee (BPAC). Evaluation of the Safety and Effectiveness of the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test. May 15, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Previous HIV testing among adults and adolescents newly diagnosed with HIV infection—National HIV Surveillance System, 18 jurisdictions, United States, 2006–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:441–445.

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–17.

- McNeil DG. Rapid H.I.V. Home Test Wins Federal Approval. New York Times, July 3, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/health/oraquick-at-home-hiv-test-wins-fda-approval.html. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data—United States and 6 US Dependent Areas—2010 HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report, Volume 17, Number 3 (Part A). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010supp_vol-17no3/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2010 HIV Surveillance Report, Volume 22. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2010report/index.htm. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Attia S, Egger M, Müller M, Zwahlen M, Low N. Sexual transmission of HIV according to viral load and antiretroviral therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2009; 23:1397–1404.

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:793–800.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Healthy People 2020 Summary of Objectives. http://healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HIV.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2012.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 102nd Meeting of The Blood Product Advisory Committee (BPAC). Evaluation of the Safety and Effectiveness of the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test. May 15, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Previous HIV testing among adults and adolescents newly diagnosed with HIV infection—National HIV Surveillance System, 18 jurisdictions, United States, 2006–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012; 61:441–445.

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–17.

KEY POINTS

- The new test is highly (99.9%) specific for HIV but is not quite as reliable at ruling out infection (93% sensitivity). Therefore, it may miss some cases of HIV, especially during the 90-day window after initial infection.

- False-positive test results may occur, especially in people at low risk. A positive result must be confirmed with a laboratory-based third- or fourth-generation blood test.

- It is important to continue to assess and counsel patients on how to modify their risk of HIV infection.

- Providers are urged to offer HIV testing to all patients ages 13 to 64 at least once, regardless of their risk.

- At least once a year, patients at high risk should get one of the more sensitive laboratory blood tests.

- People who choose to test themselves at home should seek medical care for verification of the test result and for HIV counseling, and, if the result is confirmed positive, access to HIV care.

Novel strategy to prevent recurrent UTI in premenopausal women

Related article Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (October 2012)

Related article Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (October 2012)

Related article Update on Pelvic Floor Dysfunction (October 2012)

Venous Thromboembolism and Weight Changes in Veteran Patients Using Megestrol Acetate as an Appetite Stimulant

New and Noteworthy Information—October

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is linked with a substantial risk of disability, researchers reported in the September 13 online Stroke. The 510 consecutive patients prospectively enrolled in the study had minor stroke or TIA, were not previously disabled, and had a CT or CT angiography completed within 24 hours of symptom onset. After assessing disability 90 days following the event, the investigators found that 15% of patients had a disabled outcome. Those who experienced recurrent strokes were more likely to be disabled—53% of patients with recurrent strokes were disabled, compared with 12% of those who did not have a recurrent stroke. “In terms of absolute numbers, most patients have disability as a result of their presenting event; however, recurrent events have the largest relative impact on outcome,” the study authors concluded.

Persons with high plasma glucose levels that are still within the normal range are more likely to have atrophy of brain structures associated with neurodegenerative processes, according to a study published in the September 4 Neurology. Investigators used MRI scans to assess hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in a sample of 266 cognitively healthy persons ages 60 to 64 who did not have type 2 diabetes. Results showed that plasma glucose levels were significantly linked with hippocampal and amygdalar atrophy. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, alcohol, and smoking, the researchers found that plasma glucose levels accounted for a 6% to 10% change in volume. “These findings suggest that even in the subclinical range and in the absence of diabetes, monitoring and management of plasma glucose levels could have an impact on cerebral health,” the study authors wrote.

The FDA has approved once-a-day tablet Aubagio (teriflunomide) for treatment of adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). During a clinical trial, patients taking teriflunomide had a relapse rate that was 30% lower than that of patients taking placebo. The most common side effects observed during clinical trials were diarrhea, abnormal liver tests, nausea, and hair loss, and physicians should conduct blood tests to check patients’ liver function before the drug is prescribed as well as periodically during treatment, researchers said. In addition, because of a risk of fetal harm, women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before beginning teriflunomide and should use birth control throughout treatment. Teriflunomide is the second oral treatment therapy for MS to be approved in the United States.

Patients who appear likely to have sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease may benefit from CSF 14-3-3 assays to clarify the diagnosis, researchers reported in the online September 19 Neurology. In a systematic literature review, the investigators identified articles from 1995 to January 1, 2011, that involved patients who had CSF analysis for protein 14-3-3. Based on data from 1,849 patients, the researchers determined that assays for CSF 14-3-3 are probably moderately accurate in diagnosing Creutzfeldt-Jakob—the assays had a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 80%, likelihood ratio of 4.7, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.10. The study authors recommend CSF 14-3-3 assays “for patients who have rapidly progressive dementia and are strongly suspected of having sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob and for whom diagnosis remains uncertain (pretest probably of between 20% and 90%).”

Children with migraine and children with tension-type headaches are significantly more likely to have behavioral and emotional symptoms, and the frequency of headaches affects the likelihood of these symptoms, according to a study published in the online September 17 Cephalagia. After examining a sample of 1,856 children ages 5 to 11, investigators found that those with migraine were significantly more likely to experience abnormalities in somatic, anxiety-depressive, social, attention, internalizing, and total score domains of the Child Behavior Checklist. Children with tension-type headaches had a lower rate of abnormalities than children with migraine, but those with tension-type headaches still had significantly more abnormalities than controls. Children with headaches are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than externalizing symptoms such as rule breaking and aggressivity, the researchers found.

Heavy alcohol intake is associated with experiencing intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, according to a study published in the September 11 Neurology. Researchers prospectively followed 562 adults with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage and recorded information about their alcohol intake. A total of 137 patients were heavy alcohol drinkers, and these patients were more likely to be younger (median age, 60), to have a history of ischemic heart disease, and to be smokers. Furthermore, heavy alcohol drinkers had significantly lower platelet counts and prothrombin ratio. The investigators noted that although heavy alcohol intake is associated with intracerebral hemorrhage at a younger age, “the underlying vasculopathy remains unexplored in these patients. Indirect markers suggest small-vessel disease at an early stage that might be enhanced by moderate hemostatic disorders,” the authors concluded.

Long-term use of ginkgo biloba extract does not prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease in older patients, according to a study published in the online September 5 Lancet Neurology. Researchers enrolled 2,854 participants in a parallel-group, double-blind clinical trial in which 1,406 persons were randomized to receive ginkgo biloba extract and 1,414 persons were randomized to placebo. After five years of follow-up, 61 participants taking ginkgo biloba were diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease, while 73 participants in the placebo group received a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease, though the risk was not proportional over time. The incidence of adverse events, as well as hemorrhagic or cardiovascular events, did not differ between groups. “Long-term use of standardized ginkgo biloba extract in this trial did not reduce the risk of progression to Alzheimer’s disease compared with placebo,” the researchers concluded.

The 13.3–mg/24 h dosage strength of the Exelon Patch (rivastigmine transdermal system) has been approved by the FDA for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Approval was based on the performance of the 13.3–mg/24 h dosage in the 48-week, double-blind phase of the OPTIMA study, which analyzed patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease who met predefined functional and cognitive decline criteria for the 9.5–mg/24 h dose. Compared with patients taking the 9.5–mg/24 h dose, patients taking the 13.3–mg/24 h dose showed statistically significant improvement in overall function. In addition, the overall safety profile of the 13.3–mg/24 h dose was the same as that of the lower dose, and fewer patients on the 13.3–mg/24 h dose needed to discontinue treatment than patients on the 9.5–mg/24 h dose.

The FDA has approved Nucynta (tapentadol) for management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy when a continuous, around-the-clock opioid analgesic is needed for an extended period of time. According to preclinical studies, the drug is a centrally acting synthetic analgesic, though the exact mechanism of action is unknown. In two randomized-withdrawal, placebo-controlled phase III trials, researchers studied patients who had at least a one-point reduction in pain intensity during three weeks of treatment and then continued for an additional 12 weeks on the same dose, which was titrated to balance individual tolerability and efficacy. These patients had significantly better pain control than those who switched to placebo. The most common adverse events associated with the drug were nausea, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, headache, and somnolence, but tapentadol was generally well tolerated.

A mouse model of abnormal adult-generated granule cells (DGCs) has provided the first direct evidence that abnormal DGCs are linked to seizures, researchers reported in the September 20 Neuron. To isolate the effects of the abnormal cells, investigators used a transgenic mouse model to selectively delete PTEN from DGCs generated after birth. As a result of PTEN deletion, the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway was hyperactivated, which produced abnormal DGCs that resembled those in epilepsy. “Strikingly, animals in which PTEN was deleted from 9% or more of the DGC population developed spontaneous seizures in about four weeks, confirming that abnormal DGCs, which are present in both animals and humans with epilepsy, are capable of causing the disease,” the researchers stated.

Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who receive gingko biloba 120 mg twice a day do not show improved cognitive performance, researchers reported in the September 18 Neurology. The investigators compared the performance of two groups of patients with MS who scored 1 SD or more below the mean on one of four neuropsychologic tests. Sixty-one patients received 120 mg of ginkgo biloba twice a day for 12 weeks, and 59 patients received placebo. The researchers evaluated participants’ cognitive performance following treatment and found no statistically significant difference in scores between the two groups. Furthermore, no significant adverse events related to gingko biloba treatment occurred, according to the study authors. Overall, the investigators concluded that gingko biloba does not improve cognitive function in patients with MS.

The Solitaire Flow Restoration device performs substantially better than the Merci Retrieval System in treating acute ischemic stroke, according to a study published in the online August 24 Lancet. In a randomized, parallel-group, noninferiority trial, the efficacy and safety of the Solitaire device, a self-expanding stent retriever designed to quickly restore blood flow, was compared with the efficacy and safety of the standard Merci Retrieval system. The 58 patients in the Solitaire group achieved the primary efficacy outcome 61% of the time, compared with 24% of patients in the Merci group, investigators said. Furthermore, patients in the Solitaire group had lower 90-day mortality than patients in the Merci group (17 versus 38). “The Solitaire device might be a future treatment of choice for endovascular recanalization in acute ischemic stroke,” the researchers concluded.

—Lauren LeBano

Transient ischemic attack (TIA) is linked with a substantial risk of disability, researchers reported in the September 13 online Stroke. The 510 consecutive patients prospectively enrolled in the study had minor stroke or TIA, were not previously disabled, and had a CT or CT angiography completed within 24 hours of symptom onset. After assessing disability 90 days following the event, the investigators found that 15% of patients had a disabled outcome. Those who experienced recurrent strokes were more likely to be disabled—53% of patients with recurrent strokes were disabled, compared with 12% of those who did not have a recurrent stroke. “In terms of absolute numbers, most patients have disability as a result of their presenting event; however, recurrent events have the largest relative impact on outcome,” the study authors concluded.

Persons with high plasma glucose levels that are still within the normal range are more likely to have atrophy of brain structures associated with neurodegenerative processes, according to a study published in the September 4 Neurology. Investigators used MRI scans to assess hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in a sample of 266 cognitively healthy persons ages 60 to 64 who did not have type 2 diabetes. Results showed that plasma glucose levels were significantly linked with hippocampal and amygdalar atrophy. After controlling for age, sex, BMI, hypertension, alcohol, and smoking, the researchers found that plasma glucose levels accounted for a 6% to 10% change in volume. “These findings suggest that even in the subclinical range and in the absence of diabetes, monitoring and management of plasma glucose levels could have an impact on cerebral health,” the study authors wrote.

The FDA has approved once-a-day tablet Aubagio (teriflunomide) for treatment of adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS). During a clinical trial, patients taking teriflunomide had a relapse rate that was 30% lower than that of patients taking placebo. The most common side effects observed during clinical trials were diarrhea, abnormal liver tests, nausea, and hair loss, and physicians should conduct blood tests to check patients’ liver function before the drug is prescribed as well as periodically during treatment, researchers said. In addition, because of a risk of fetal harm, women of childbearing age must have a negative pregnancy test before beginning teriflunomide and should use birth control throughout treatment. Teriflunomide is the second oral treatment therapy for MS to be approved in the United States.

Patients who appear likely to have sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease may benefit from CSF 14-3-3 assays to clarify the diagnosis, researchers reported in the online September 19 Neurology. In a systematic literature review, the investigators identified articles from 1995 to January 1, 2011, that involved patients who had CSF analysis for protein 14-3-3. Based on data from 1,849 patients, the researchers determined that assays for CSF 14-3-3 are probably moderately accurate in diagnosing Creutzfeldt-Jakob—the assays had a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 80%, likelihood ratio of 4.7, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.10. The study authors recommend CSF 14-3-3 assays “for patients who have rapidly progressive dementia and are strongly suspected of having sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob and for whom diagnosis remains uncertain (pretest probably of between 20% and 90%).”

Children with migraine and children with tension-type headaches are significantly more likely to have behavioral and emotional symptoms, and the frequency of headaches affects the likelihood of these symptoms, according to a study published in the online September 17 Cephalagia. After examining a sample of 1,856 children ages 5 to 11, investigators found that those with migraine were significantly more likely to experience abnormalities in somatic, anxiety-depressive, social, attention, internalizing, and total score domains of the Child Behavior Checklist. Children with tension-type headaches had a lower rate of abnormalities than children with migraine, but those with tension-type headaches still had significantly more abnormalities than controls. Children with headaches are more likely to have internalizing symptoms than externalizing symptoms such as rule breaking and aggressivity, the researchers found.