User login

The "Holy Grail," Where Do We Go From Here?

As physicians, we are always trying to keep up with the latest techniques and technology to provide the best possible care for our patients. However, history shows us that many of the “newest and greatest” devices have poorly understood, or maybe even, unknown consequences. You may remember the excitement over the Gortex ligament augmentation device (LAD) for ACL reconstruction in the 1970’s or the thermal capsular shrinkage “heat probe” of the 1990’s. The orthopedic annals are littered with groundbreaking technologies that proved to be, at best, merely failures,or, at worst, dangerous to the patients we are trying to heal.

We are now in a time of rapidly changing technology and information overload, clogged with access to reams of information through our PDAs and the internet. Patients learn about new techniques and technology not from their physician, but from advertisements in the media or online. This dissemination of information without any real “filter” to verify accuracy and safety has heightened the burden on us, as surgeons, to be up to speed and critical of every “better mousetrap.” Patients may request or even demand a certain technique based on limited study of online discussions, chat rooms, or non–peer reviewed data. It is our obligation to “first, do no harm” even if the patient demands it.

How can we possibly provide the best for our patients and keep up with technology that may prove to be “the holy grail”? We must rely on well planned, peer-reviewed research studies that clearly analyze not only the positive results, but also the potential complications of new technology. In this month’s issue, E. Carlos Rodríguez-Merchán MD, PhD, (‘‘The Treatment of Cartilage Defects in the Knee Joint: Microfracture, Mosaicplasty, and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation,’’click here) reviews the treatment of cartilage defects in the knee joint: comparing microfracture, mosaicplasty, and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). However, he concludes that good level I evidence is lacking to show significant difference between any of the 3 commonly performed techniques. Does this mean that all of the procedures result in equal outcomes? No. Does this mean that we should abandon the more costly procedures, such as ACI? No. What Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán does is highlight the need for carefully designed level I studies to define the real outcomes, indications, and complications of our new technologies.

What is the holy grail in orthopedics? I would argue that the ability to take an easily obtained and prepared stem cell line and use the appropriate growth factors and chemical signals to cause the cells to differentiate into different tissue types (eg, bone, cartilage, ligament, etc.) represents this holy grail. Think about all of the potential uses for this technology and it is easy to see the whole field of orthopedic surgery being transformed during my lifetime. Imagine being able to grow new cartilage or ligament tissue and direct the body’s response to these new tissues. However, with these possibilities also come enormous risk.

One significant unpredicted outcome or inappropriate application could lead to huge consequences, terrible complications, bad publicity, and loss of patient-physician trust. Just imagine the late night television commercials and billboards advertising for the local law firm that “you may be entitled to compensation.” Or just imagine the uncertainty injected into the physician-patient relationship, “you aren’t going to put one of those recalled parts in me are you?” You may have followed the recent controversy over “pink slime,” the “lean, finely textured beef” added to processed hamburger patties. Although used for decades, the recent media coverage of beef filler has severely affected the public’s trust in the food industry. Can you imagine how a similar public relations nightmare over failed technology could affect the orthopedic industry?

I have often been guilty of complaining about the arduous task of getting new technology approved though the regulatory bodies in the United States, compared with the perceived progressive nature of the process in Europe. I do believe that we should have a streamlined process for some new technology that may save lives, especially chemotherapy medications. However, a more diligent, and thorough process must be applied to new technology used for elective procedures, as in most orthopedic applications. Unfortunately, until sufficient safety data and good outcomes research is completed and analyzed, we must temper the enthusiasm of doctors and patients alike.

Author's Disclosure Statement. The author reports no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

As physicians, we are always trying to keep up with the latest techniques and technology to provide the best possible care for our patients. However, history shows us that many of the “newest and greatest” devices have poorly understood, or maybe even, unknown consequences. You may remember the excitement over the Gortex ligament augmentation device (LAD) for ACL reconstruction in the 1970’s or the thermal capsular shrinkage “heat probe” of the 1990’s. The orthopedic annals are littered with groundbreaking technologies that proved to be, at best, merely failures,or, at worst, dangerous to the patients we are trying to heal.

We are now in a time of rapidly changing technology and information overload, clogged with access to reams of information through our PDAs and the internet. Patients learn about new techniques and technology not from their physician, but from advertisements in the media or online. This dissemination of information without any real “filter” to verify accuracy and safety has heightened the burden on us, as surgeons, to be up to speed and critical of every “better mousetrap.” Patients may request or even demand a certain technique based on limited study of online discussions, chat rooms, or non–peer reviewed data. It is our obligation to “first, do no harm” even if the patient demands it.

How can we possibly provide the best for our patients and keep up with technology that may prove to be “the holy grail”? We must rely on well planned, peer-reviewed research studies that clearly analyze not only the positive results, but also the potential complications of new technology. In this month’s issue, E. Carlos Rodríguez-Merchán MD, PhD, (‘‘The Treatment of Cartilage Defects in the Knee Joint: Microfracture, Mosaicplasty, and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation,’’click here) reviews the treatment of cartilage defects in the knee joint: comparing microfracture, mosaicplasty, and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). However, he concludes that good level I evidence is lacking to show significant difference between any of the 3 commonly performed techniques. Does this mean that all of the procedures result in equal outcomes? No. Does this mean that we should abandon the more costly procedures, such as ACI? No. What Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán does is highlight the need for carefully designed level I studies to define the real outcomes, indications, and complications of our new technologies.

What is the holy grail in orthopedics? I would argue that the ability to take an easily obtained and prepared stem cell line and use the appropriate growth factors and chemical signals to cause the cells to differentiate into different tissue types (eg, bone, cartilage, ligament, etc.) represents this holy grail. Think about all of the potential uses for this technology and it is easy to see the whole field of orthopedic surgery being transformed during my lifetime. Imagine being able to grow new cartilage or ligament tissue and direct the body’s response to these new tissues. However, with these possibilities also come enormous risk.

One significant unpredicted outcome or inappropriate application could lead to huge consequences, terrible complications, bad publicity, and loss of patient-physician trust. Just imagine the late night television commercials and billboards advertising for the local law firm that “you may be entitled to compensation.” Or just imagine the uncertainty injected into the physician-patient relationship, “you aren’t going to put one of those recalled parts in me are you?” You may have followed the recent controversy over “pink slime,” the “lean, finely textured beef” added to processed hamburger patties. Although used for decades, the recent media coverage of beef filler has severely affected the public’s trust in the food industry. Can you imagine how a similar public relations nightmare over failed technology could affect the orthopedic industry?

I have often been guilty of complaining about the arduous task of getting new technology approved though the regulatory bodies in the United States, compared with the perceived progressive nature of the process in Europe. I do believe that we should have a streamlined process for some new technology that may save lives, especially chemotherapy medications. However, a more diligent, and thorough process must be applied to new technology used for elective procedures, as in most orthopedic applications. Unfortunately, until sufficient safety data and good outcomes research is completed and analyzed, we must temper the enthusiasm of doctors and patients alike.

Author's Disclosure Statement. The author reports no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

As physicians, we are always trying to keep up with the latest techniques and technology to provide the best possible care for our patients. However, history shows us that many of the “newest and greatest” devices have poorly understood, or maybe even, unknown consequences. You may remember the excitement over the Gortex ligament augmentation device (LAD) for ACL reconstruction in the 1970’s or the thermal capsular shrinkage “heat probe” of the 1990’s. The orthopedic annals are littered with groundbreaking technologies that proved to be, at best, merely failures,or, at worst, dangerous to the patients we are trying to heal.

We are now in a time of rapidly changing technology and information overload, clogged with access to reams of information through our PDAs and the internet. Patients learn about new techniques and technology not from their physician, but from advertisements in the media or online. This dissemination of information without any real “filter” to verify accuracy and safety has heightened the burden on us, as surgeons, to be up to speed and critical of every “better mousetrap.” Patients may request or even demand a certain technique based on limited study of online discussions, chat rooms, or non–peer reviewed data. It is our obligation to “first, do no harm” even if the patient demands it.

How can we possibly provide the best for our patients and keep up with technology that may prove to be “the holy grail”? We must rely on well planned, peer-reviewed research studies that clearly analyze not only the positive results, but also the potential complications of new technology. In this month’s issue, E. Carlos Rodríguez-Merchán MD, PhD, (‘‘The Treatment of Cartilage Defects in the Knee Joint: Microfracture, Mosaicplasty, and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation,’’click here) reviews the treatment of cartilage defects in the knee joint: comparing microfracture, mosaicplasty, and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). However, he concludes that good level I evidence is lacking to show significant difference between any of the 3 commonly performed techniques. Does this mean that all of the procedures result in equal outcomes? No. Does this mean that we should abandon the more costly procedures, such as ACI? No. What Dr. Rodríguez-Merchán does is highlight the need for carefully designed level I studies to define the real outcomes, indications, and complications of our new technologies.

What is the holy grail in orthopedics? I would argue that the ability to take an easily obtained and prepared stem cell line and use the appropriate growth factors and chemical signals to cause the cells to differentiate into different tissue types (eg, bone, cartilage, ligament, etc.) represents this holy grail. Think about all of the potential uses for this technology and it is easy to see the whole field of orthopedic surgery being transformed during my lifetime. Imagine being able to grow new cartilage or ligament tissue and direct the body’s response to these new tissues. However, with these possibilities also come enormous risk.

One significant unpredicted outcome or inappropriate application could lead to huge consequences, terrible complications, bad publicity, and loss of patient-physician trust. Just imagine the late night television commercials and billboards advertising for the local law firm that “you may be entitled to compensation.” Or just imagine the uncertainty injected into the physician-patient relationship, “you aren’t going to put one of those recalled parts in me are you?” You may have followed the recent controversy over “pink slime,” the “lean, finely textured beef” added to processed hamburger patties. Although used for decades, the recent media coverage of beef filler has severely affected the public’s trust in the food industry. Can you imagine how a similar public relations nightmare over failed technology could affect the orthopedic industry?

I have often been guilty of complaining about the arduous task of getting new technology approved though the regulatory bodies in the United States, compared with the perceived progressive nature of the process in Europe. I do believe that we should have a streamlined process for some new technology that may save lives, especially chemotherapy medications. However, a more diligent, and thorough process must be applied to new technology used for elective procedures, as in most orthopedic applications. Unfortunately, until sufficient safety data and good outcomes research is completed and analyzed, we must temper the enthusiasm of doctors and patients alike.

Author's Disclosure Statement. The author reports no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

The Treatment of Cartilage Defects in the Knee Joint: Microfracture, Mosaicplasty, and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

Bone Graft Extenders and Substitutes in the Thoracolumbar Spine

An Innovative Approach to Concave-Convex Allograft Junctions: A Biomechanical Study

Epithelioid Sarcoma: An Unusual Presentation in the Distal Phalanx of the Toe

Alopecia in an Ophiasis Pattern: Traction Alopecia Versus Alopecia Areata

"Hemorrhoids" turn out to be cancer … and more

“Hemorrhoids” turn out to be cancer

A 49-YEAR-OLD WOMAN, whose husband was on active duty with the US Army, went to an army community hospital in March complaining of hemorrhoids, back pain, and itching, burning, and pain with bowel movements. A guaiac-based fecal occult blood test was positive; no further testing was done to rule out rectal cancer.

The woman was discharged with pain medication but returned the following day, reporting intense anal pain despite taking the medication and bright red blood in her stools. The symptoms were attributed to hemorrhoids, and the patient was given a toilet “donut” and topical medication. Although her records noted a referral to a general surgeon, the referral wasn’t arranged or scheduled.

The patient returned to the hospital in April, May, and June with continuing complaints that included unrelieved constipation. A laxative was prescribed, but no further testing was done, nor was the patient referred to a surgeon.

In August, she went to the emergency department because of rectal bleeding for the previous 2 weeks, abdominal pain, blood in her urine, and difficulty breathing. Once again the symptoms were blamed on hemorrhoids even though the patient questioned the diagnosis.

The patient continued to see various providers at the army community hospital for the rest of the year, during which time she turned 50. None of them recommended a colonoscopy despite standard recommendations to begin colorectal cancer screening at 50 years of age and the woman’s symptoms, which suggested colorectal cancer.

In March of the following year, the patient consulted a bariatric surgeon in private practice, who recommended evaluating the patient’s bloody stools and offered to perform a diagnostic colonoscopy if authorized. The army hospital didn’t immediately authorize the procedure, and it wasn’t performed.

In late September, the patient consulted a surgeon at the hospital, by which time bright red blood was squirting from her anal region and appeared in the toilet water after every bowel movement. She had never undergone a full colon evaluation.

Less than a week after the surgery consult, the patient’s husband was transferred to another military base. Her doctors said that a surgeon at the new base would be told about her medical condition, but that didn’t happen.

Five months later, a surgery consultation at the new military base found a rectal lesion extending 8 cm into the rectum from the anal verge. Pathology confirmed stage IIIC mucinous adenocarcinoma that had spread to the lymph nodes. Two years later, after several surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation, the patient died at 53 years of age.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM If testing to rule out rectal cancer, such as a colonoscopy, had been performed earlier, the cancer would have been diagnosed at a curable stage.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $2.15 million Tennessee settlement.

COMMENT Recurrent, unrelenting symptoms should prompt the alert clinician to explore alternative diagnoses.

For want of diagnosis and treatment, kidney function is lost

A FEBRILE ILLNESS prompted a patient to visit his primary care physician. After 3 months of treatment by the primary care doctor, the patient sought a second opinion and treatment from a federally funded community health clinic, where he was treated for 2 more months. During that time, the patient developed signs and symptoms of impaired kidney function, which laboratory results confirmed.

The clinic staff didn’t address the possible loss of kidney function. Three days after his last examination at the clinic, the patient went to a hospital emergency department, where he was promptly diagnosed with subacute bacterial endocarditis. His kidney function could not be restored.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician and the staff at the clinic were negligent in failing to diagnose and treat the kidney issues. Also, they didn’t recognize and treat the signs and symptoms of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

THE DEFENSE The primary care physician claimed that the patient’s injuries resulted solely from negligence on the part of the clinic staff. He maintained that the patient’s kidney function was normal when the man left his care. The federal government, on behalf of the clinic staff, claimed that the primary care physician was at least 50% responsible for the patient’s injuries.

VERDICT $1.45 million Texas settlement.

COMMENT Subacute bacterial endocarditis can be a challenging diagnosis because of the subtlety and variety of presentations. Remember the zebras when confronted with unexplained symptoms and signs.

Neuropathy blamed on belated diabetes diagnosis

A PATIENT IN A FAMILY PRACTICE was treated by several of the doctors and a physician assistant in the group over about a decade. After the patient developed neuropathy in his arms and legs, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Earlier diagnosis of the diabetes would have prevented development of neuropathy. High blood glucose levels identified on tests weren’t addressed.

THE DEFENSE Only 3 tests had shown excessive levels of glucose; the patient had many comorbidities that required attention. A special diet had been prescribed that would have helped control glucose levels. This was an appropriate initial step to address a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

VERDICT $285,000 New York settlement.

COMMENT It’s easy to overlook or postpone treatment of apparently less urgent issues such as glucose intolerance. Clear documentation and explicit discussion with patients might help mitigate the risk of adverse judgments.

Too many narcotic prescriptions

A WOMAN TREATED FOR CHRONIC SINUSITIS by an ear, nose, and throat physician received prescriptions for oxycodone, acetaminophen and oxycodone, and methadone for years to relieve headaches and facial pain. She died at 40 years of age from a methadone overdose. The physician admitted in a deposition that he’d kept on prescribing the medications even after the patient’s health insurer informed him that she was obtaining narcotics from multiple providers.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.05 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Strict tracking and oversight of opioid administration is essential. Clear documentation and regular follow-up remain very important.

Delayed Tx turns skin breakdown into a long-term problem

A NEARLY IMMOBILE WOMAN was discharged from a hospital—where she’d been treated for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, altered mental status, severe arthritis, and gout—and transported by ambulance to her home. Discharge diagnoses included possible obstructive sleep apnea and hypercapnia. Because the patient needed a great deal of help with activities of daily living, her physician ordered home health services.

Twelve days after discharge, a representative from the home health agency performed an initial assessment in the patient’s home, at which time the patient’s daughter reported that her mother had developed some skin breakdown on her buttocks that required care. The home health nurse allegedly told the daughter that the agency would need an order from her mother’s physician before starting home treatment for the skin breakdown.

The daughter phoned the physician every day for the next few days to get treatment authorization, but the doctor didn’t return her calls. The home health agency didn’t seek authorization from the doctor.

When the home health nurse returned to the patient’s home a week later to begin care, the daughter again mentioned the areas of skin breakdown, which by that time had become pressure sores. The nurse didn’t treat the pressure sores. The home health agency tried to contact the patient’s physician, who didn’t return their calls.

The agency finally received an order to treat the pressure sores 6 days after the home health nurse had begun caring for the patient, by which time the sores were infected and considerably larger. Healing required more than a year of treatment.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM As a result of the delay in treating the pressure sores, the patient’s condition was worse that it otherwise would have been.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied any negligence.

VERDICT Alabama defense verdict.

COMMENT Better communication and coordination of care between home health providers and a patient’s medical home are important to provide optimal care—and avoid lawsuits.

“Hemorrhoids” turn out to be cancer

A 49-YEAR-OLD WOMAN, whose husband was on active duty with the US Army, went to an army community hospital in March complaining of hemorrhoids, back pain, and itching, burning, and pain with bowel movements. A guaiac-based fecal occult blood test was positive; no further testing was done to rule out rectal cancer.

The woman was discharged with pain medication but returned the following day, reporting intense anal pain despite taking the medication and bright red blood in her stools. The symptoms were attributed to hemorrhoids, and the patient was given a toilet “donut” and topical medication. Although her records noted a referral to a general surgeon, the referral wasn’t arranged or scheduled.

The patient returned to the hospital in April, May, and June with continuing complaints that included unrelieved constipation. A laxative was prescribed, but no further testing was done, nor was the patient referred to a surgeon.

In August, she went to the emergency department because of rectal bleeding for the previous 2 weeks, abdominal pain, blood in her urine, and difficulty breathing. Once again the symptoms were blamed on hemorrhoids even though the patient questioned the diagnosis.

The patient continued to see various providers at the army community hospital for the rest of the year, during which time she turned 50. None of them recommended a colonoscopy despite standard recommendations to begin colorectal cancer screening at 50 years of age and the woman’s symptoms, which suggested colorectal cancer.

In March of the following year, the patient consulted a bariatric surgeon in private practice, who recommended evaluating the patient’s bloody stools and offered to perform a diagnostic colonoscopy if authorized. The army hospital didn’t immediately authorize the procedure, and it wasn’t performed.

In late September, the patient consulted a surgeon at the hospital, by which time bright red blood was squirting from her anal region and appeared in the toilet water after every bowel movement. She had never undergone a full colon evaluation.

Less than a week after the surgery consult, the patient’s husband was transferred to another military base. Her doctors said that a surgeon at the new base would be told about her medical condition, but that didn’t happen.

Five months later, a surgery consultation at the new military base found a rectal lesion extending 8 cm into the rectum from the anal verge. Pathology confirmed stage IIIC mucinous adenocarcinoma that had spread to the lymph nodes. Two years later, after several surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation, the patient died at 53 years of age.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM If testing to rule out rectal cancer, such as a colonoscopy, had been performed earlier, the cancer would have been diagnosed at a curable stage.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $2.15 million Tennessee settlement.

COMMENT Recurrent, unrelenting symptoms should prompt the alert clinician to explore alternative diagnoses.

For want of diagnosis and treatment, kidney function is lost

A FEBRILE ILLNESS prompted a patient to visit his primary care physician. After 3 months of treatment by the primary care doctor, the patient sought a second opinion and treatment from a federally funded community health clinic, where he was treated for 2 more months. During that time, the patient developed signs and symptoms of impaired kidney function, which laboratory results confirmed.

The clinic staff didn’t address the possible loss of kidney function. Three days after his last examination at the clinic, the patient went to a hospital emergency department, where he was promptly diagnosed with subacute bacterial endocarditis. His kidney function could not be restored.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician and the staff at the clinic were negligent in failing to diagnose and treat the kidney issues. Also, they didn’t recognize and treat the signs and symptoms of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

THE DEFENSE The primary care physician claimed that the patient’s injuries resulted solely from negligence on the part of the clinic staff. He maintained that the patient’s kidney function was normal when the man left his care. The federal government, on behalf of the clinic staff, claimed that the primary care physician was at least 50% responsible for the patient’s injuries.

VERDICT $1.45 million Texas settlement.

COMMENT Subacute bacterial endocarditis can be a challenging diagnosis because of the subtlety and variety of presentations. Remember the zebras when confronted with unexplained symptoms and signs.

Neuropathy blamed on belated diabetes diagnosis

A PATIENT IN A FAMILY PRACTICE was treated by several of the doctors and a physician assistant in the group over about a decade. After the patient developed neuropathy in his arms and legs, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Earlier diagnosis of the diabetes would have prevented development of neuropathy. High blood glucose levels identified on tests weren’t addressed.

THE DEFENSE Only 3 tests had shown excessive levels of glucose; the patient had many comorbidities that required attention. A special diet had been prescribed that would have helped control glucose levels. This was an appropriate initial step to address a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

VERDICT $285,000 New York settlement.

COMMENT It’s easy to overlook or postpone treatment of apparently less urgent issues such as glucose intolerance. Clear documentation and explicit discussion with patients might help mitigate the risk of adverse judgments.

Too many narcotic prescriptions

A WOMAN TREATED FOR CHRONIC SINUSITIS by an ear, nose, and throat physician received prescriptions for oxycodone, acetaminophen and oxycodone, and methadone for years to relieve headaches and facial pain. She died at 40 years of age from a methadone overdose. The physician admitted in a deposition that he’d kept on prescribing the medications even after the patient’s health insurer informed him that she was obtaining narcotics from multiple providers.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.05 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Strict tracking and oversight of opioid administration is essential. Clear documentation and regular follow-up remain very important.

Delayed Tx turns skin breakdown into a long-term problem

A NEARLY IMMOBILE WOMAN was discharged from a hospital—where she’d been treated for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, altered mental status, severe arthritis, and gout—and transported by ambulance to her home. Discharge diagnoses included possible obstructive sleep apnea and hypercapnia. Because the patient needed a great deal of help with activities of daily living, her physician ordered home health services.

Twelve days after discharge, a representative from the home health agency performed an initial assessment in the patient’s home, at which time the patient’s daughter reported that her mother had developed some skin breakdown on her buttocks that required care. The home health nurse allegedly told the daughter that the agency would need an order from her mother’s physician before starting home treatment for the skin breakdown.

The daughter phoned the physician every day for the next few days to get treatment authorization, but the doctor didn’t return her calls. The home health agency didn’t seek authorization from the doctor.

When the home health nurse returned to the patient’s home a week later to begin care, the daughter again mentioned the areas of skin breakdown, which by that time had become pressure sores. The nurse didn’t treat the pressure sores. The home health agency tried to contact the patient’s physician, who didn’t return their calls.

The agency finally received an order to treat the pressure sores 6 days after the home health nurse had begun caring for the patient, by which time the sores were infected and considerably larger. Healing required more than a year of treatment.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM As a result of the delay in treating the pressure sores, the patient’s condition was worse that it otherwise would have been.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied any negligence.

VERDICT Alabama defense verdict.

COMMENT Better communication and coordination of care between home health providers and a patient’s medical home are important to provide optimal care—and avoid lawsuits.

“Hemorrhoids” turn out to be cancer

A 49-YEAR-OLD WOMAN, whose husband was on active duty with the US Army, went to an army community hospital in March complaining of hemorrhoids, back pain, and itching, burning, and pain with bowel movements. A guaiac-based fecal occult blood test was positive; no further testing was done to rule out rectal cancer.

The woman was discharged with pain medication but returned the following day, reporting intense anal pain despite taking the medication and bright red blood in her stools. The symptoms were attributed to hemorrhoids, and the patient was given a toilet “donut” and topical medication. Although her records noted a referral to a general surgeon, the referral wasn’t arranged or scheduled.

The patient returned to the hospital in April, May, and June with continuing complaints that included unrelieved constipation. A laxative was prescribed, but no further testing was done, nor was the patient referred to a surgeon.

In August, she went to the emergency department because of rectal bleeding for the previous 2 weeks, abdominal pain, blood in her urine, and difficulty breathing. Once again the symptoms were blamed on hemorrhoids even though the patient questioned the diagnosis.

The patient continued to see various providers at the army community hospital for the rest of the year, during which time she turned 50. None of them recommended a colonoscopy despite standard recommendations to begin colorectal cancer screening at 50 years of age and the woman’s symptoms, which suggested colorectal cancer.

In March of the following year, the patient consulted a bariatric surgeon in private practice, who recommended evaluating the patient’s bloody stools and offered to perform a diagnostic colonoscopy if authorized. The army hospital didn’t immediately authorize the procedure, and it wasn’t performed.

In late September, the patient consulted a surgeon at the hospital, by which time bright red blood was squirting from her anal region and appeared in the toilet water after every bowel movement. She had never undergone a full colon evaluation.

Less than a week after the surgery consult, the patient’s husband was transferred to another military base. Her doctors said that a surgeon at the new base would be told about her medical condition, but that didn’t happen.

Five months later, a surgery consultation at the new military base found a rectal lesion extending 8 cm into the rectum from the anal verge. Pathology confirmed stage IIIC mucinous adenocarcinoma that had spread to the lymph nodes. Two years later, after several surgeries, chemotherapy, and radiation, the patient died at 53 years of age.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM If testing to rule out rectal cancer, such as a colonoscopy, had been performed earlier, the cancer would have been diagnosed at a curable stage.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $2.15 million Tennessee settlement.

COMMENT Recurrent, unrelenting symptoms should prompt the alert clinician to explore alternative diagnoses.

For want of diagnosis and treatment, kidney function is lost

A FEBRILE ILLNESS prompted a patient to visit his primary care physician. After 3 months of treatment by the primary care doctor, the patient sought a second opinion and treatment from a federally funded community health clinic, where he was treated for 2 more months. During that time, the patient developed signs and symptoms of impaired kidney function, which laboratory results confirmed.

The clinic staff didn’t address the possible loss of kidney function. Three days after his last examination at the clinic, the patient went to a hospital emergency department, where he was promptly diagnosed with subacute bacterial endocarditis. His kidney function could not be restored.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The primary care physician and the staff at the clinic were negligent in failing to diagnose and treat the kidney issues. Also, they didn’t recognize and treat the signs and symptoms of subacute bacterial endocarditis.

THE DEFENSE The primary care physician claimed that the patient’s injuries resulted solely from negligence on the part of the clinic staff. He maintained that the patient’s kidney function was normal when the man left his care. The federal government, on behalf of the clinic staff, claimed that the primary care physician was at least 50% responsible for the patient’s injuries.

VERDICT $1.45 million Texas settlement.

COMMENT Subacute bacterial endocarditis can be a challenging diagnosis because of the subtlety and variety of presentations. Remember the zebras when confronted with unexplained symptoms and signs.

Neuropathy blamed on belated diabetes diagnosis

A PATIENT IN A FAMILY PRACTICE was treated by several of the doctors and a physician assistant in the group over about a decade. After the patient developed neuropathy in his arms and legs, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM Earlier diagnosis of the diabetes would have prevented development of neuropathy. High blood glucose levels identified on tests weren’t addressed.

THE DEFENSE Only 3 tests had shown excessive levels of glucose; the patient had many comorbidities that required attention. A special diet had been prescribed that would have helped control glucose levels. This was an appropriate initial step to address a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes.

VERDICT $285,000 New York settlement.

COMMENT It’s easy to overlook or postpone treatment of apparently less urgent issues such as glucose intolerance. Clear documentation and explicit discussion with patients might help mitigate the risk of adverse judgments.

Too many narcotic prescriptions

A WOMAN TREATED FOR CHRONIC SINUSITIS by an ear, nose, and throat physician received prescriptions for oxycodone, acetaminophen and oxycodone, and methadone for years to relieve headaches and facial pain. She died at 40 years of age from a methadone overdose. The physician admitted in a deposition that he’d kept on prescribing the medications even after the patient’s health insurer informed him that she was obtaining narcotics from multiple providers.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.05 million New Jersey settlement.

COMMENT Strict tracking and oversight of opioid administration is essential. Clear documentation and regular follow-up remain very important.

Delayed Tx turns skin breakdown into a long-term problem

A NEARLY IMMOBILE WOMAN was discharged from a hospital—where she’d been treated for congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, altered mental status, severe arthritis, and gout—and transported by ambulance to her home. Discharge diagnoses included possible obstructive sleep apnea and hypercapnia. Because the patient needed a great deal of help with activities of daily living, her physician ordered home health services.

Twelve days after discharge, a representative from the home health agency performed an initial assessment in the patient’s home, at which time the patient’s daughter reported that her mother had developed some skin breakdown on her buttocks that required care. The home health nurse allegedly told the daughter that the agency would need an order from her mother’s physician before starting home treatment for the skin breakdown.

The daughter phoned the physician every day for the next few days to get treatment authorization, but the doctor didn’t return her calls. The home health agency didn’t seek authorization from the doctor.

When the home health nurse returned to the patient’s home a week later to begin care, the daughter again mentioned the areas of skin breakdown, which by that time had become pressure sores. The nurse didn’t treat the pressure sores. The home health agency tried to contact the patient’s physician, who didn’t return their calls.

The agency finally received an order to treat the pressure sores 6 days after the home health nurse had begun caring for the patient, by which time the sores were infected and considerably larger. Healing required more than a year of treatment.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM As a result of the delay in treating the pressure sores, the patient’s condition was worse that it otherwise would have been.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied any negligence.

VERDICT Alabama defense verdict.

COMMENT Better communication and coordination of care between home health providers and a patient’s medical home are important to provide optimal care—and avoid lawsuits.

The latest recommendations from the USPSTF

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

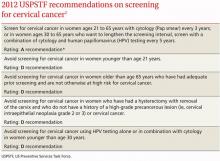

Screening for cervical cancer

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

Screening for cervical cancer

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

Recently, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finalized 7 recommendations on 5 topics and posted draft recommendations on an additional 10 topics. It also implemented new procedures that include posting draft recommendations for public comment (see “A new review process for the USPSTF”). This article reviews the USPSTF activity in 2011, as well as cervical cancer screening recommendations issued earlier this year.

In response to the adverse publicity from the 2009 mammogram recommendations and the increased scrutiny brought on by the affordable care act—which mandates that A and B recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task force are covered preventive services provided at no charge to the patient—the USPSTF developed and implemented a new review procedure. This is intended to increase stakeholder involvement at all steps in the process.

Last year, the USPSTF completed its rollout of this new online review process. The USPSTF now posts all draft recommendations and the evidence report supporting them on its Web site for public comment. final recommendations are posted months later after consideration of the public input. The final recommendations for the 10 topics with draft recommendations posted in 2011 are expected to be released this year.

Potential for confusion. The new process may cause confusion for family physicians. Draft recommendations will receive press coverage and may differ from the final recommendations, as happened with cervical cancer screening recommendations. Physicians will need to familiarize themselves with the process and look for final recommendations on the USPSTF Web site at http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/recommendations.htm.

2012 recommendations

Screening for cervical cancer

The USPSTF released its new recommendations on screening for cervical cancer in March (TABLE 1).1 The final document varied from the 2011 draft recommendations in 2 areas: the roles of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and sexual history.

- The draft issued an I statement (insufficient evidence) for the role of HPV testing. Subsequently, based on stakeholder and public comment (as well as a review of 2 large recently published studies), the USPSTF gave an A recommendation to the use of HPV testing in conjunction with cervical cytology as an option for women ages 30 years and older who want to increase the interval between screening to 5 years.2,3

- The draft stated that the age at which screening should be initiated depends on a patient’s sexual history. The final recommendations state that screening should not begin until age 21, regardless of sexual history.

TABLE 1

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

These new recommendations balance the proven benefits of cervical cytology with the harms from overscreening and are now essentially the same as those of other organizations, including the American Cancer Society, the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and the American Society for Clinical Pathology. They differ in minor ways from those of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the American Academy of Family Physicians is assessing whether to endorse them.

Importantly, the new recommendations identify individuals for whom cervical cytology should be avoided—women younger than age 21, most women older than age 65, and those who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix. A decision to stop screening after the 65th birthday depends on whether the patient has had adequate screening yielding normal findings: This is defined by the USPSTF as 3 consecutive negative cytology results (or 2 consecutive negative co-test results with cytology and HIV testing) within 10 years of the proposed time of cessation, with the most recent test having been performed within 5 years. Avoiding cytology testing after hysterectomy is contingent on the procedure having been performed for an indication other than a high-grade precancerous lesion or cervical cancer. In addition, the recommendations advise against HPV testing in women younger than age 30, as it offers little advantage and leads to much overdiagnosis.

Liquid vs conventional cytology. As a minor point, the USPSTF says the evidence clearly shows that liquid cytology offers no advantage over conventional cytology. But it recognizes that the screening method used is often not determined by the physician.

Recommendations finalized in 2011

TABLE 2 summarizes recommendations completed by the USPSTF last year.

Neonatal gonococcal eye infection prevention

The recommendation to use topical medication (erythromycin ointment) to prevent neonatal gonococcal eye infection is an update and reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Blindness due to this disease has become rare in the United States because of the routine use of a neonatal topical antibiotic, and there is good evidence that it causes no significant harm. Its use continues to be recommended for all newborns.4

TABLE 2

*For more on the USPSTF's grade definitions, see http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm.

Vision screening for children

Vision screening for preschool children can detect visual acuity problems such as amblyopia and refractive errors. A variety of screening tests are available, including visual acuity, stereoacuity, cover-uncover, Hirschberg light reflex, and auto-refractor tests (automated optical instruments that detect refractive errors). The most benefit is obtained by discovering and correcting amblyopia.

There is no evidence that detecting problems before age 3 years leads to better outcomes than detection between 3 and 5 years of age. Testing is more difficult in younger children and can yield inconclusive or false-positive results more frequently. This led the USPSTF to reaffirm vision testing once for children ages 3 to 5 years, and to state that the evidence is insufficient to make a recommendation for younger children.5

Screening for osteoporosis

The recommendations indicate that all women ages 65 and older should undergo screening, although the optimal frequency of screening is not known. The clinical discussion accompanying the recommendation indicates there is reason to believe that screening men may reduce morbidity and mortality, but that sufficient evidence for or against this is lacking.6

Screening can be done with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) of the hip and lumbar spine, or quantitative ultrasonography of the calcaneus. DEXA is most commonly used, and is the basis for most treatment recommendations.

The recommendation to screen some women younger than 65 years, based on risk, is somewhat complex. The USPSTF recommends screening younger women if their 10-year risk of fracture is comparable to that of a 65-year-old white woman with no additional risk factors (a risk of 9.3% over 10 years). To calculate that risk, the USPSTF recommends using the FRAX (Fracture Risk Assessment) tool developed by the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases, Sheffield, United Kingdom, which is available free to clinicians and the public (www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/).

Screening for testicular cancer

The recommendation against screening for testicular cancer may surprise many physicians, even though it is a reaffirmation of a previous recommendation. Testicular cancer is uncommon (5 cases per 100,000 males per year) and treatment is successful in a large proportion of patients, regardless of the stage at which it is discovered. Patients or their partners discover these tumors in time for a cure and there is no evidence physician exams improve outcomes. Physician discovery of incidental and inconsequential findings such as spermatoceles and varicoceles can lead to unnecessary testing and follow-up.7

Screening for bladder cancer

The USPSTF issued an I statement for bladder cancer screening because there is little evidence regarding the diagnostic accuracy of available tests (urinalysis for microscopic hematuria, urine cytology, or tests for urine biomarkers) in detecting bladder cancer in asymptomatic patients. In addition, there is no evidence regarding the potential benefits of detecting asymptomatic bladder cancer.8

Current draft recommendations

The USPSTF posts recommendations on its Web site for public comment for 30 days. To see current draft recommendations, go to http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/tfcomment.htm.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

1. USPSTF. Screening for cervical cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

2. Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:78-88.

3. Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:663-672.

4. USPSTF. Ocular prophylaxis for gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsgononew.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

5. USPSTF. Screening for vision impairment in children ages 1 to 5 years. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvsch.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

6. USPSTF. Screening for osteoporosis. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsoste.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

7. USPSTF. Screening for testicular cancer. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstest.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

8. USPSTF. Screening for bladder cancer in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsblad.htm. Accessed March 10, 2012.

What drugs are effective for periodic limb movement disorder?

CLONAZEPAM improves subjective sleep quality and polysomnogram (PSG) measures of leg movements more than placebo (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a small randomized controlled trial [RCT]); temazepam produces similar results (SOR: C, extrapolated from a small comparison trial).

Melatonin and L-dopa consistently improve certain PSG measures, but their effect on subjective sleep quality varies; valproate improves only subjective measures; apomorphine injections reduce limb movements but not awakenings (SOR: C, very small crossover and cohort trials).

Estrogen replacement therapy is ineffective for periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) associated with menopause (SOR: B, RCT).

Evidence summary

Although PLMD often occurs in association with restless legs syndrome, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and other sleep disorders, it is itself an intrinsic sleep disorder characterized by stereotyped limb movements and sleep disruption.1 Most treatment studies of PLMD report both subjective and objective measures of sleep quality. Two commonly used objective measures, obtained by PSG, are the periodic leg movement (PLM) index and the PLM arousal index. The TABLE summarizes the evidence of medication trials.

Clonazepam improves subjective sleep measures, leg movements

Three comparative trials evaluated clonazepam against placebo, temazepam, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).1-3 In the placebo-controlled and temazepam trials, clonazepam significantly improved subjective sleep parameters and leg movements.1,2 However, the studies produced conflicting results as to whether clonazepam reduced awakening from limb movements. Both temazepam and clonazepam appeared to be comparably effective; the trial was underpowered to detect a difference between them.

The CBT trial didn’t describe the frequency or duration of CBT clearly.3 It isn’t included in the TABLE.

L-Dopa decreases leg motions, effects on subjective sleep symptoms vary

Two comparison trials evaluated L-dopa (combined with carbidopa). One trial compared L-dopa with propoxyphene and placebo, and the other compared it with pergolide, a bromocriptine agonist available in Canada and Europe.4,5

In both trials, L-dopa consistently reduced leg motions at night but produced a variable response in subjective sleep symptoms and nocturnal waking. Propoxyphene yielded modest improvements in subjective sleep symptoms and nocturnal waking over placebo. The L-dopa–propoxyphene comparison trial was underpowered to allow a statistical comparison between the 2 medications.

Melatonin and valproate produce opposite effects in small studies

Three very small trials recorded symptoms and PSG findings in patients taking melatonin, apomorphine, or valproate, and compared them with the values observed at baseline.6-8 Melatonin significantly improved objective measures, but most patients didn’t feel less sleepy. Valproate produced the opposite effect—no clear PSG improvements, but all study patients felt better. Injected apomorphine reduced limb movements but not awakenings.

Estrogen replacement therapy doesn’t help

An RCT of estrogen replacement therapy for PLMD enrolled postmenopausal women, about half of whom were found to have PLMD.9 The study found estrogen replacement therapy to be ineffective for treating menopause-associated PLMD.

Recommendations

Practice parameters developed by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine state that clonazepam, pergolide, L-dopa (with a decarboxylase inhibitor), oxycodone, and propoxyphene are all reasonable choices for medical treatment of PLMD.10 The practice parameters don’t specify a preference for any of these medications.

1. Saletu M, Anderer P, Saletu-Zyhlarz G, et al. Restless legs syndrome (RLS) and periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD): acute placebo-controlled sleep laboratory studies with clonazepam. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11:153-161.

2. Mitler MM, Browman CP, Menn SJ, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus: treatment efficacy of clonazepam and temazepam. Sleep. 1986;9:385-392.

3. Edinger JD, Fins AI, Sullivan RJ, et al. Comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and clonazepam for treating periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep. 1996;19:442-444.

4. Staedt J, Wassmuth F, Ziemann U, et al. Pergolide: treatment of choice in restless legs syndrome (RLS) and nocturnal myoclonus syndrome (NMS). A double-blind randomized crossover trial of pergolide versus L-Dopa. J Neural Transm. 1997;104:461-468.

5. Kaplan PW, Allen RP, Buchholz DW, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the treatment of periodic limb movements in sleep using carbidopa/levodopa and propoxyphene. Sleep. 1993;16:717-723.

6. Kunz D, Bes F. Exogenous melatonin in periodic limb movement disorder: an open clinical trial and a hypothesis. Sleep. 2001;24:183-187.

7. Haba-Rubio J, Staner L, Cornette F, et al. Acute low single dose of apomorphine reduces periodic limb movements but has no significant effect on sleep arousals: a preliminary report. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:180-184.

8. Ehrenberg BL, Eisensehr I, Corbett KE, et al. Valproate for sleep consolidation in periodic limb movement disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:574-578.

9. Polo-Kantola P, Rauhala E, Erkkola R, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy and nocturnal periodic limb movements: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:548-554.

10. Chesson AL, Jr, Wise M, Davila D, et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Report. Sleep. 1999;22:961-968.

CLONAZEPAM improves subjective sleep quality and polysomnogram (PSG) measures of leg movements more than placebo (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a small randomized controlled trial [RCT]); temazepam produces similar results (SOR: C, extrapolated from a small comparison trial).

Melatonin and L-dopa consistently improve certain PSG measures, but their effect on subjective sleep quality varies; valproate improves only subjective measures; apomorphine injections reduce limb movements but not awakenings (SOR: C, very small crossover and cohort trials).

Estrogen replacement therapy is ineffective for periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) associated with menopause (SOR: B, RCT).

Evidence summary

Although PLMD often occurs in association with restless legs syndrome, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and other sleep disorders, it is itself an intrinsic sleep disorder characterized by stereotyped limb movements and sleep disruption.1 Most treatment studies of PLMD report both subjective and objective measures of sleep quality. Two commonly used objective measures, obtained by PSG, are the periodic leg movement (PLM) index and the PLM arousal index. The TABLE summarizes the evidence of medication trials.

Clonazepam improves subjective sleep measures, leg movements

Three comparative trials evaluated clonazepam against placebo, temazepam, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).1-3 In the placebo-controlled and temazepam trials, clonazepam significantly improved subjective sleep parameters and leg movements.1,2 However, the studies produced conflicting results as to whether clonazepam reduced awakening from limb movements. Both temazepam and clonazepam appeared to be comparably effective; the trial was underpowered to detect a difference between them.

The CBT trial didn’t describe the frequency or duration of CBT clearly.3 It isn’t included in the TABLE.

L-Dopa decreases leg motions, effects on subjective sleep symptoms vary

Two comparison trials evaluated L-dopa (combined with carbidopa). One trial compared L-dopa with propoxyphene and placebo, and the other compared it with pergolide, a bromocriptine agonist available in Canada and Europe.4,5