User login

Triple therapy: Boon or bane for high-risk CV patients?

• In a patient with a high risk of reinfarction, thienopyridine therapy (with clopidogrel or prasugrel) should be continued for at least a year. B

• Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. A

• For patients who are good candidates for triple therapy but have an elevated bleeding risk, using a lower dose of aspirin or limiting thienopyridine use to one month may be a reasonable option. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Anthony D, a 61-year-old patient of yours with hypertension and diabetes, is admitted to the hospital with atrial fibrillation and chest pain that radiates to his left arm and hand. On Day 1, he receives aspirin 325 mg and enoxaparin 1 mg/kg; the following day, the patient receives a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel prior to catheterization. He undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention and a bare metal stent is placed in his circumflex artery.

The following day, Anthony is ready for discharge and you consider which maintenance drugs to put him on, given that he already takes multiple medications. Is he a candidate for triple therapy?

Triple therapy—the concurrent use of aspirin, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, and warfarin—is often prescribed for patients with atrial fibrillation who experience acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or require percutaneous coronary intervention with the placement of a stent (PCI-S). The danger associated with concomitantly treating a patient with 3 agents, each of which has a distinct mechanism that increases bleeding risk, is high, but for carefully selected patients, the benefit may outweigh the risk.

Several studies have evaluated triple therapy and compared it with single or dual therapy (TABLE).1-5 Due to a lack of robust outcome studies, however, the benefits and risks of triple therapy cannot be directly quantified, nor are they generalizable to all potential candidates for triple therapy. Thus, finding the optimal treatment for secondary prevention of ACS or prevention of stent thrombosis in a patient with atrial fibrillation requires an understanding of the potential consequences of triple therapy—and a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stroke, and bleeding complications.6-9 To make the best treatment decisions and provide adequate support to patients who were started on triple therapy during a recent hospitalization, here’s what you need to know.

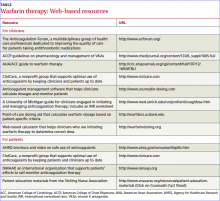

TABLE

Triple therapy: What the studies show

| Study type (N) | Intervention | Efficacy | Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective (124)1 | Group 1: Aspirin + clopidogrel + warfarin Group 2: Nontriple therapy | No significant difference | No significant difference in early major bleeding Group 1: Significant increase in late major bleeding |

| Retrospective (373)2 | Group 1: Anticoagulant + antithrombotic therapy* Group 2: Antithrombotic therapy only | Group 1: Significant improvement in efficacy Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes | Group 1: Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes |

| Cohort (800)3 | Group 1: Warfarin + single antiplatelet agent Group 2: Warfarin + dual antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference in mortality or MI | NR |

| Prospective (359)4 | Group 1: Continued OAC + dual antiplatelet therapy Group 2: Discontinued OAC but continued antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference | Group 1: Significant increase in moderate and severe bleeding |

| Cohort (82,854)5 | Group 1: Warfarin monotherapy Group 2: Aspirin monotherapy Group 3: Clopidogrel monotherapy Group 4: Clopidogrel + aspirin Group 5: Warfarin + aspirin Group 6: Warfarin + clopidogrel Group 7: Warfarin + aspirin + clopidogrel | No significant difference | Groups 6 and 7: Significant increase in crude incidence of bleeding |

| *50% of the participants in Group 1 received triple therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin). MI, myocardial infarction; NR, not reported; OAC, oral anticoagulant. | |||

First, a review of the components

Aspirin, a key component of triple therapy, is the only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) indicated for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.10,11 The reason: Aspirin is more selective for cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) than other NSAIDs and irreversibly inhibits COX enzymes.11 The aspirin-induced decrease in thromboxane production leads to a decline in platelet activation and aggregation, which accounts both for aspirin’s beneficial cardiovascular effects and the associated risk of bleeding—aspirin’s most common adverse effect.12

Most major bleeds linked to aspirin use involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, primarily because of the drug’s direct and indirect effects on the GI mucosa.11-14 Aspirin’s toxicities are dose related, but its antiplatelet properties do not appear to be.14

Adding a thienopyridine

Thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs indicated for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events after ACS or PCI-S include ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel.15 Ticlopidine, the first such agent approved in the United States, is rarely used because of potential neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura.16

Clopidogrel, the most commonly used agent for the purpose of secondary prevention, is the only thienopyridine with trial data for triple therapy.17 Clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect, however, is highly dependent on specific cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzymes for conversion to its active metabolite, and can be impaired by genetic variations in CYP 2C19, as well as by medication interactions. This has led to concern about the drug’s efficacy for secondary prevention of ACS.6,17,18 In 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added a black-box warning for clopidogrel, emphasizing the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cardiovascular death in patients with defective CYP 2C19 activity.19

Prasugrel, approved by the FDA in 2009,20 is useful for patients who respond poorly to clopidogrel. In fact, inadequate platelet inhibition with clopidogrel has prompted some physicians to choose prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.

While prasugrel may have greater efficacy compared with clopidogrel in preventing reinfarction, it appears to have a higher bleeding rate.15,17 Because of its bleeding profile, prasugrel is not recommended for patients >75 years unless they are at high risk for MI (prior MI or diabetes), and it is contraindicated for patients with a history of stroke. Caution is needed when prasugrel is prescribed for patients who weigh <132 lb (consider a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d rather than the usual 10 mg/d) or have an increased propensity to bleed.15

Warfarin provides the anticoagulant component of triple therapy

Until late last year, when dabigatran received FDA approval for use in stroke prevention,21 warfarin was the only oral anticoagulant available in the United States. (To learn more about dabigatran, which is not included in this review because of the lack of evidence regarding its use in triple therapy, see “Time to try this warfarin alternative?”.)

Because multiple drug, food, and disease state interactions can interfere with warfarin therapy, frequent monitoring to maintain a target international normalized ratio (INR) is required.22,23 (See Patient on warfarin? Steer clear of these drugs, in “Avoiding drug interactions: Here’s help,” J Fam Pract. 2010;59: 322-329).

Bridge therapy. Warfarin requires several days to reach its full effect, so anticoagulation with a more immediate-acting medication, such as a low-molecular-weight heparin or fondaparinux, is often used until the INR goal is reached.22,23 Thus, there are instances in which patients requiring triple therapy are actually receiving 4 drugs that increase bleeding risk.

When (or whether) to consider triple therapy

While triple therapy may be an option for patients with atrial fibrillation and ACS or PCI-S, there is no validated scoring system to aid in treatment decisions.24 As already noted, selecting the optimal therapy requires an individual assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and bleeding complications.

Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.10,16 Advanced age; uncontrolled hypertension; chronic conditions such as peripheral vascular disease, anemia, and peptic ulcer disease; and a history of major bleeds are associated with an increased risk of bleeding. 24,25

In a retrospective trial evaluating independent predictors of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent PCI-S,1 the researchers identified several factors that increased the risk of early major bleeding (within 48 hours of stent placement): the use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, stenting of ≥3 vessels, or left main artery disease. Factors that significantly increased the risk of major bleeding more than 48 hours after the procedure included triple therapy, an early major bleed, and baseline anemia.1

Drug combinations: What to consider

In addition to determining whether a patient is a good candidate for triple therapy, it is crucial to consider the choice of drugs. Benefits of prasugrel, compared with clopidogrel, include fewer drug interactions, less resistance to platelet inhibition, more rapid platelet inhibition after an oral loading dose, and higher levels of platelet inhibition during maintenance dosing.15,17

Improved outcomes are another potential benefit, according to TRITON-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 38,17 a large randomized prospective trial comparing the use of prasugrel with clopidogrel in triple therapy. Among study participants, the primary outcome rate—the combined incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke—was 9.9% for those on prasugrel vs 12.1% for the clopidogrel group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.90, P<.001).17 The rate of TIMI major bleeding, however, was higher among those on prasugrel (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.68, P=.03). The evidence suggests that for every 1000 patients treated with prasugrel vs clopidogrel, 24 primary outcomes would be prevented but there would be 10 additional bleeding events.17,26

CASE Anthony D’s risk for stroke, infarction, and stent thrombosis—based on his history of diabetes and hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and PCI-S—and absence of independent bleeding risk factors make him a good candidate for triple therapy. Because the patient is at high risk, the physician starts him on 2 anticoagulants—warfarin (5 mg at bedtime) and enoxaparin (125 mg every 12 hours)—on the evening of his second day in the hospital. On Day 3, clinicians test Anthony’s prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and P2Y12 function assay, which measure 14.9/1.1 and 8% platelet inhibition, respectively.

The patient is discharged on the following medication schedule: enoxaparin 125 mg every 12 hours, to be discontinued after 3 days; warfarin 5 mg daily, prasugrel 10 mg daily, and aspirin 81 mg daily; metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily; lisinopril 10 mg daily; rosuvastatin 10 mg daily; glyburide-metformin 5 mg/500 mg, 2 tablets twice daily; and insulin glargine 20 units at bedtime.

Safety and efficacy: Do the benefits outweigh the risk?

Safety is central to the continuing controversy surrounding the use of triple therapy.6,9 To date, however, no randomized prospective studies have evaluated its benefits and risks.

Numerous retrospective studies and case series have assessed the risk of bleeding associated with triple therapy.6 Several studies compared triple therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation, and found a several-fold increase in both major and minor bleeding events in the triple therapy group.6

Few trials have assessed both the safety and the efficacy of triple therapy, however. One exception is a large retrospective trial, published in 2008.2 The researchers found that triple therapy significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiac events (death, acute MI, and target lesion revascularization); all-cause mortality; and major adverse effects (ie, any major cardiovascular event, major bleeding complication, and/or stroke), with no statistically significant increase in major bleeding events compared with patients on antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation.2

The results of this trial, like those of other studies evaluating triple therapy, were weakened by variance in both the duration of antithrombotic therapy and the drug therapies studied. This limitation was off set, however, by multivariant analysis and well-documented follow-up.2 Despite the researchers’ findings, however, the results of other trials (and our knowledge of the mechanisms of action of the drug components) suggest that triple therapy significantly increases bleeding risk. For patients who would likely benefit from it but face an increased bleeding risk, there are ways to mitigate risk.

Prescribing triple therapy, while mitigating the risks

If bleeding is a serious concern in a patient who would benefit from triple therapy, the drug regimen may be adjusted. Options include:

- targeting a lower INR (2.0-2.5 vs the standard 2.0-3.0).6 While various trials have found a 2.0 to 3.0 range to reduce the risk of stroke, none has compared it with a lower range to evaluate reduction in bleeding risk.27 One potential benefit of trying to maintain a lower INR is the decrease in deviations into the 3.0 to 4.0 range, which is associated with an increased bleeding risk.28 However, lowering the INR target is not supported by any literature.1,18

- using low-dose aspirin therapy after PCI-S

- limiting the thienopyridine component of triple therapy to one month after ACS or PCI-S.6

When the risks of triple therapy outweigh the benefits because of an exceedingly high bleeding risk, single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin is another option to consider.

CASE [H17012] Anthony D’s discharge instructions called for an 81 mg daily dose of aspirin, as opposed to the 325-mg dose for the first 3 months of triple therapy after stent placement recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for unstable angina/ non-ST segment elevated MI.1 Although the patient had no independent bleeding risk, his physician selected the lower dose of aspirin to mitigate the increased bleeding risk posed by the use of prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.6

Lower aspirin dose. Pharmacodynamic studies support the use of a lower dose of aspirin, finding that serum thromboxane is completely inhibited by a maintenance dose as low as 30 mg/d in healthy individuals and 50 mg/d for those with chronic stable angina.14 Using low-dose aspirin for the secondary prevention of ACS when triple therapy is indicated is likely to reduce GI toxicities as well as bleeding risk.

Reduce the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, thienopyridine therapy can be limited to one month in patients who are medically managed or have had a bare metal stent placed if there is concern about the patient’s risk of bleeding.6,10 Based on the findings of the one study that found triple therapy to be an independent predictor of major bleeds, this approach seems reasonable.1 It is called into question, however, by another recent trial, which found that patients on dual antiplatelet therapy for one year (vs one month) had a statistically significant improvement in cardiovascular outcomes.16

Before limiting a patient’s thienopyridine therapy to one month, consider his or her risk of reinfarction. If it is high, continuing the thienopyridine for at least one year is likely to provide the most benefit.

The largest triple therapy trial to date compared the efficacy of triple therapy vs dual therapy (a single antiplatelet agent plus warfarin) in patients with ACS and an indication for warfarin therapy.3 This trial found no statistically significant differences in the combined occurrence of death, stroke, unscheduled PCI, and MI between the 2 treatment groups. (Bleeding risk was not evaluated.) Stroke was significantly increased in the group that received therapy with warfarin and a single antiplatelet agent, with this caveat: The occurrence of stroke was so low overall that no conclusions could be reached from this difference.3

One problem with this trial, and with others evaluating triple therapy, has to do with the lack of consistency, as well as the duration. The warfarin and single antiplatelet group, for example, may have included patients who were receiving only warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel by 6 months after initiating treatment.3 Thus, although reinfarction or stent thrombosis after ACS or PCI-S typically occurs within the first few months, any triple therapy trial that lasts less than a year is likely to report skewed results. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Haley M. Phillippe, PharmD, BCPS, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, University of Alabama Birmingham School of Medicine?Huntsville, 301 Governors Drive, Huntsville, AL 35801; mccrahl@auburn.edu

1. Manzano-Fernandez S, Pastor FJ, Marin F, et al. Increased major bleeding complications related to triple antithrombotic therapy usage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary artery stenting. Chest. 2008;134:559-567.

2. Ruiz-Nodar JM, Marin F, Hurtado JA, et al. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in 426 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:818-25.

3. Nguyen MC, Lim YL, Walton A, et al. Combining warfarin and antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events: is it safe and effective to use just one antiplatelet agent? Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1717-1722.

4. Gilard M, Blanchard D, Helft G, et al. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with anticoagulants undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting (from STENTIng and oral anticoagulants [STENTICO]). Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:338-342.

5. Hansen ML, Sorensent R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1433-1441.

6. Hermosillo AJ, Spinler SA. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin: is the combination appropriate and effective or inappropriate and too dangerous? Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:790-805.

7. Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, et al. Warfarin plus aspirin after myocardial infarction or the acute coronary syndrome: meta-analysis with estimates of risk and benefit. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:241-250.

8. Eikelboom JM, Hirsh J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:255-263.

9. Triple antithrombotic therapy Pharm Lett/Prescr Lett. 2009;25:250901.-

10. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. ACC/AHA guideline revision. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

11. Furst DE, Ulrich RW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, and drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;573-598.

12. Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. The eicosanoids: prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and related compounds. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;293-308.

13. Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM, et al. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:379-386.

14. Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, et al. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2018-2024.

15. Lexi-Comp [database online]. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, Inc. Copyright 1978-2007. Available at: http://www.crlonline.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 5, 2010.

16. Spinler SA, Rees C. Review of Prasugrel for the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:383-95.

17. Spinler SA, Denus SD, et al. Acute coronary syndromes. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;249-277.

18. Plavix [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb/ Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership; 2010.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA announces new boxed warning on Plavix. March 12, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/Press Announcements/ucm204253.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

20. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Effient to reduce the risk of heart attack in angioplasty patients. July 10, 2009. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/News-room/PressAnnouncements/ucm171497.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

21. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Pradaxa to prevent stroke in people with atrial fibrillation. October 19, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm230241.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

22. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, et al. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines (8Th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl):160S-198S.

23. Haines ST, Witt DM, Nutescu EA. Venous thromboembolism. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;331-369.

24. Lip G. The balance between stroke prevention and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation: a delicate balance revisited. Stroke. 2008;39:1406-1408.

25. The Warfarin Antiplatelet Vascular Evaluation Trial Investigators. Oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy and peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:217-227.

26. Schafer JA, Kjesbo NK, Gleason PP. Critical review of prasugrel for formulary decision makers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:335-343.

27. Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2008;133(suppl):546S-592S.

28. Price MJ. Bedside evaluation of thienopyridine antiplatelet therapy. Circulation. 2009;119:2625-2632.

• In a patient with a high risk of reinfarction, thienopyridine therapy (with clopidogrel or prasugrel) should be continued for at least a year. B

• Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. A

• For patients who are good candidates for triple therapy but have an elevated bleeding risk, using a lower dose of aspirin or limiting thienopyridine use to one month may be a reasonable option. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Anthony D, a 61-year-old patient of yours with hypertension and diabetes, is admitted to the hospital with atrial fibrillation and chest pain that radiates to his left arm and hand. On Day 1, he receives aspirin 325 mg and enoxaparin 1 mg/kg; the following day, the patient receives a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel prior to catheterization. He undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention and a bare metal stent is placed in his circumflex artery.

The following day, Anthony is ready for discharge and you consider which maintenance drugs to put him on, given that he already takes multiple medications. Is he a candidate for triple therapy?

Triple therapy—the concurrent use of aspirin, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, and warfarin—is often prescribed for patients with atrial fibrillation who experience acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or require percutaneous coronary intervention with the placement of a stent (PCI-S). The danger associated with concomitantly treating a patient with 3 agents, each of which has a distinct mechanism that increases bleeding risk, is high, but for carefully selected patients, the benefit may outweigh the risk.

Several studies have evaluated triple therapy and compared it with single or dual therapy (TABLE).1-5 Due to a lack of robust outcome studies, however, the benefits and risks of triple therapy cannot be directly quantified, nor are they generalizable to all potential candidates for triple therapy. Thus, finding the optimal treatment for secondary prevention of ACS or prevention of stent thrombosis in a patient with atrial fibrillation requires an understanding of the potential consequences of triple therapy—and a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stroke, and bleeding complications.6-9 To make the best treatment decisions and provide adequate support to patients who were started on triple therapy during a recent hospitalization, here’s what you need to know.

TABLE

Triple therapy: What the studies show

| Study type (N) | Intervention | Efficacy | Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective (124)1 | Group 1: Aspirin + clopidogrel + warfarin Group 2: Nontriple therapy | No significant difference | No significant difference in early major bleeding Group 1: Significant increase in late major bleeding |

| Retrospective (373)2 | Group 1: Anticoagulant + antithrombotic therapy* Group 2: Antithrombotic therapy only | Group 1: Significant improvement in efficacy Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes | Group 1: Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes |

| Cohort (800)3 | Group 1: Warfarin + single antiplatelet agent Group 2: Warfarin + dual antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference in mortality or MI | NR |

| Prospective (359)4 | Group 1: Continued OAC + dual antiplatelet therapy Group 2: Discontinued OAC but continued antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference | Group 1: Significant increase in moderate and severe bleeding |

| Cohort (82,854)5 | Group 1: Warfarin monotherapy Group 2: Aspirin monotherapy Group 3: Clopidogrel monotherapy Group 4: Clopidogrel + aspirin Group 5: Warfarin + aspirin Group 6: Warfarin + clopidogrel Group 7: Warfarin + aspirin + clopidogrel | No significant difference | Groups 6 and 7: Significant increase in crude incidence of bleeding |

| *50% of the participants in Group 1 received triple therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin). MI, myocardial infarction; NR, not reported; OAC, oral anticoagulant. | |||

First, a review of the components

Aspirin, a key component of triple therapy, is the only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) indicated for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.10,11 The reason: Aspirin is more selective for cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) than other NSAIDs and irreversibly inhibits COX enzymes.11 The aspirin-induced decrease in thromboxane production leads to a decline in platelet activation and aggregation, which accounts both for aspirin’s beneficial cardiovascular effects and the associated risk of bleeding—aspirin’s most common adverse effect.12

Most major bleeds linked to aspirin use involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, primarily because of the drug’s direct and indirect effects on the GI mucosa.11-14 Aspirin’s toxicities are dose related, but its antiplatelet properties do not appear to be.14

Adding a thienopyridine

Thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs indicated for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events after ACS or PCI-S include ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel.15 Ticlopidine, the first such agent approved in the United States, is rarely used because of potential neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura.16

Clopidogrel, the most commonly used agent for the purpose of secondary prevention, is the only thienopyridine with trial data for triple therapy.17 Clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect, however, is highly dependent on specific cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzymes for conversion to its active metabolite, and can be impaired by genetic variations in CYP 2C19, as well as by medication interactions. This has led to concern about the drug’s efficacy for secondary prevention of ACS.6,17,18 In 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added a black-box warning for clopidogrel, emphasizing the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cardiovascular death in patients with defective CYP 2C19 activity.19

Prasugrel, approved by the FDA in 2009,20 is useful for patients who respond poorly to clopidogrel. In fact, inadequate platelet inhibition with clopidogrel has prompted some physicians to choose prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.

While prasugrel may have greater efficacy compared with clopidogrel in preventing reinfarction, it appears to have a higher bleeding rate.15,17 Because of its bleeding profile, prasugrel is not recommended for patients >75 years unless they are at high risk for MI (prior MI or diabetes), and it is contraindicated for patients with a history of stroke. Caution is needed when prasugrel is prescribed for patients who weigh <132 lb (consider a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d rather than the usual 10 mg/d) or have an increased propensity to bleed.15

Warfarin provides the anticoagulant component of triple therapy

Until late last year, when dabigatran received FDA approval for use in stroke prevention,21 warfarin was the only oral anticoagulant available in the United States. (To learn more about dabigatran, which is not included in this review because of the lack of evidence regarding its use in triple therapy, see “Time to try this warfarin alternative?”.)

Because multiple drug, food, and disease state interactions can interfere with warfarin therapy, frequent monitoring to maintain a target international normalized ratio (INR) is required.22,23 (See Patient on warfarin? Steer clear of these drugs, in “Avoiding drug interactions: Here’s help,” J Fam Pract. 2010;59: 322-329).

Bridge therapy. Warfarin requires several days to reach its full effect, so anticoagulation with a more immediate-acting medication, such as a low-molecular-weight heparin or fondaparinux, is often used until the INR goal is reached.22,23 Thus, there are instances in which patients requiring triple therapy are actually receiving 4 drugs that increase bleeding risk.

When (or whether) to consider triple therapy

While triple therapy may be an option for patients with atrial fibrillation and ACS or PCI-S, there is no validated scoring system to aid in treatment decisions.24 As already noted, selecting the optimal therapy requires an individual assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and bleeding complications.

Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.10,16 Advanced age; uncontrolled hypertension; chronic conditions such as peripheral vascular disease, anemia, and peptic ulcer disease; and a history of major bleeds are associated with an increased risk of bleeding. 24,25

In a retrospective trial evaluating independent predictors of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent PCI-S,1 the researchers identified several factors that increased the risk of early major bleeding (within 48 hours of stent placement): the use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, stenting of ≥3 vessels, or left main artery disease. Factors that significantly increased the risk of major bleeding more than 48 hours after the procedure included triple therapy, an early major bleed, and baseline anemia.1

Drug combinations: What to consider

In addition to determining whether a patient is a good candidate for triple therapy, it is crucial to consider the choice of drugs. Benefits of prasugrel, compared with clopidogrel, include fewer drug interactions, less resistance to platelet inhibition, more rapid platelet inhibition after an oral loading dose, and higher levels of platelet inhibition during maintenance dosing.15,17

Improved outcomes are another potential benefit, according to TRITON-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 38,17 a large randomized prospective trial comparing the use of prasugrel with clopidogrel in triple therapy. Among study participants, the primary outcome rate—the combined incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke—was 9.9% for those on prasugrel vs 12.1% for the clopidogrel group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.90, P<.001).17 The rate of TIMI major bleeding, however, was higher among those on prasugrel (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.68, P=.03). The evidence suggests that for every 1000 patients treated with prasugrel vs clopidogrel, 24 primary outcomes would be prevented but there would be 10 additional bleeding events.17,26

CASE Anthony D’s risk for stroke, infarction, and stent thrombosis—based on his history of diabetes and hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and PCI-S—and absence of independent bleeding risk factors make him a good candidate for triple therapy. Because the patient is at high risk, the physician starts him on 2 anticoagulants—warfarin (5 mg at bedtime) and enoxaparin (125 mg every 12 hours)—on the evening of his second day in the hospital. On Day 3, clinicians test Anthony’s prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and P2Y12 function assay, which measure 14.9/1.1 and 8% platelet inhibition, respectively.

The patient is discharged on the following medication schedule: enoxaparin 125 mg every 12 hours, to be discontinued after 3 days; warfarin 5 mg daily, prasugrel 10 mg daily, and aspirin 81 mg daily; metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily; lisinopril 10 mg daily; rosuvastatin 10 mg daily; glyburide-metformin 5 mg/500 mg, 2 tablets twice daily; and insulin glargine 20 units at bedtime.

Safety and efficacy: Do the benefits outweigh the risk?

Safety is central to the continuing controversy surrounding the use of triple therapy.6,9 To date, however, no randomized prospective studies have evaluated its benefits and risks.

Numerous retrospective studies and case series have assessed the risk of bleeding associated with triple therapy.6 Several studies compared triple therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation, and found a several-fold increase in both major and minor bleeding events in the triple therapy group.6

Few trials have assessed both the safety and the efficacy of triple therapy, however. One exception is a large retrospective trial, published in 2008.2 The researchers found that triple therapy significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiac events (death, acute MI, and target lesion revascularization); all-cause mortality; and major adverse effects (ie, any major cardiovascular event, major bleeding complication, and/or stroke), with no statistically significant increase in major bleeding events compared with patients on antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation.2

The results of this trial, like those of other studies evaluating triple therapy, were weakened by variance in both the duration of antithrombotic therapy and the drug therapies studied. This limitation was off set, however, by multivariant analysis and well-documented follow-up.2 Despite the researchers’ findings, however, the results of other trials (and our knowledge of the mechanisms of action of the drug components) suggest that triple therapy significantly increases bleeding risk. For patients who would likely benefit from it but face an increased bleeding risk, there are ways to mitigate risk.

Prescribing triple therapy, while mitigating the risks

If bleeding is a serious concern in a patient who would benefit from triple therapy, the drug regimen may be adjusted. Options include:

- targeting a lower INR (2.0-2.5 vs the standard 2.0-3.0).6 While various trials have found a 2.0 to 3.0 range to reduce the risk of stroke, none has compared it with a lower range to evaluate reduction in bleeding risk.27 One potential benefit of trying to maintain a lower INR is the decrease in deviations into the 3.0 to 4.0 range, which is associated with an increased bleeding risk.28 However, lowering the INR target is not supported by any literature.1,18

- using low-dose aspirin therapy after PCI-S

- limiting the thienopyridine component of triple therapy to one month after ACS or PCI-S.6

When the risks of triple therapy outweigh the benefits because of an exceedingly high bleeding risk, single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin is another option to consider.

CASE [H17012] Anthony D’s discharge instructions called for an 81 mg daily dose of aspirin, as opposed to the 325-mg dose for the first 3 months of triple therapy after stent placement recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for unstable angina/ non-ST segment elevated MI.1 Although the patient had no independent bleeding risk, his physician selected the lower dose of aspirin to mitigate the increased bleeding risk posed by the use of prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.6

Lower aspirin dose. Pharmacodynamic studies support the use of a lower dose of aspirin, finding that serum thromboxane is completely inhibited by a maintenance dose as low as 30 mg/d in healthy individuals and 50 mg/d for those with chronic stable angina.14 Using low-dose aspirin for the secondary prevention of ACS when triple therapy is indicated is likely to reduce GI toxicities as well as bleeding risk.

Reduce the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, thienopyridine therapy can be limited to one month in patients who are medically managed or have had a bare metal stent placed if there is concern about the patient’s risk of bleeding.6,10 Based on the findings of the one study that found triple therapy to be an independent predictor of major bleeds, this approach seems reasonable.1 It is called into question, however, by another recent trial, which found that patients on dual antiplatelet therapy for one year (vs one month) had a statistically significant improvement in cardiovascular outcomes.16

Before limiting a patient’s thienopyridine therapy to one month, consider his or her risk of reinfarction. If it is high, continuing the thienopyridine for at least one year is likely to provide the most benefit.

The largest triple therapy trial to date compared the efficacy of triple therapy vs dual therapy (a single antiplatelet agent plus warfarin) in patients with ACS and an indication for warfarin therapy.3 This trial found no statistically significant differences in the combined occurrence of death, stroke, unscheduled PCI, and MI between the 2 treatment groups. (Bleeding risk was not evaluated.) Stroke was significantly increased in the group that received therapy with warfarin and a single antiplatelet agent, with this caveat: The occurrence of stroke was so low overall that no conclusions could be reached from this difference.3

One problem with this trial, and with others evaluating triple therapy, has to do with the lack of consistency, as well as the duration. The warfarin and single antiplatelet group, for example, may have included patients who were receiving only warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel by 6 months after initiating treatment.3 Thus, although reinfarction or stent thrombosis after ACS or PCI-S typically occurs within the first few months, any triple therapy trial that lasts less than a year is likely to report skewed results. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Haley M. Phillippe, PharmD, BCPS, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, University of Alabama Birmingham School of Medicine?Huntsville, 301 Governors Drive, Huntsville, AL 35801; mccrahl@auburn.edu

• In a patient with a high risk of reinfarction, thienopyridine therapy (with clopidogrel or prasugrel) should be continued for at least a year. B

• Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. A

• For patients who are good candidates for triple therapy but have an elevated bleeding risk, using a lower dose of aspirin or limiting thienopyridine use to one month may be a reasonable option. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE Anthony D, a 61-year-old patient of yours with hypertension and diabetes, is admitted to the hospital with atrial fibrillation and chest pain that radiates to his left arm and hand. On Day 1, he receives aspirin 325 mg and enoxaparin 1 mg/kg; the following day, the patient receives a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel prior to catheterization. He undergoes percutaneous coronary intervention and a bare metal stent is placed in his circumflex artery.

The following day, Anthony is ready for discharge and you consider which maintenance drugs to put him on, given that he already takes multiple medications. Is he a candidate for triple therapy?

Triple therapy—the concurrent use of aspirin, a thienopyridine antiplatelet agent, and warfarin—is often prescribed for patients with atrial fibrillation who experience acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or require percutaneous coronary intervention with the placement of a stent (PCI-S). The danger associated with concomitantly treating a patient with 3 agents, each of which has a distinct mechanism that increases bleeding risk, is high, but for carefully selected patients, the benefit may outweigh the risk.

Several studies have evaluated triple therapy and compared it with single or dual therapy (TABLE).1-5 Due to a lack of robust outcome studies, however, the benefits and risks of triple therapy cannot be directly quantified, nor are they generalizable to all potential candidates for triple therapy. Thus, finding the optimal treatment for secondary prevention of ACS or prevention of stent thrombosis in a patient with atrial fibrillation requires an understanding of the potential consequences of triple therapy—and a thorough assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stroke, and bleeding complications.6-9 To make the best treatment decisions and provide adequate support to patients who were started on triple therapy during a recent hospitalization, here’s what you need to know.

TABLE

Triple therapy: What the studies show

| Study type (N) | Intervention | Efficacy | Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective (124)1 | Group 1: Aspirin + clopidogrel + warfarin Group 2: Nontriple therapy | No significant difference | No significant difference in early major bleeding Group 1: Significant increase in late major bleeding |

| Retrospective (373)2 | Group 1: Anticoagulant + antithrombotic therapy* Group 2: Antithrombotic therapy only | Group 1: Significant improvement in efficacy Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes | Group 1: Significant improvement in combination of efficacy and bleeding outcomes |

| Cohort (800)3 | Group 1: Warfarin + single antiplatelet agent Group 2: Warfarin + dual antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference in mortality or MI | NR |

| Prospective (359)4 | Group 1: Continued OAC + dual antiplatelet therapy Group 2: Discontinued OAC but continued antiplatelet therapy | No significant difference | Group 1: Significant increase in moderate and severe bleeding |

| Cohort (82,854)5 | Group 1: Warfarin monotherapy Group 2: Aspirin monotherapy Group 3: Clopidogrel monotherapy Group 4: Clopidogrel + aspirin Group 5: Warfarin + aspirin Group 6: Warfarin + clopidogrel Group 7: Warfarin + aspirin + clopidogrel | No significant difference | Groups 6 and 7: Significant increase in crude incidence of bleeding |

| *50% of the participants in Group 1 received triple therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin). MI, myocardial infarction; NR, not reported; OAC, oral anticoagulant. | |||

First, a review of the components

Aspirin, a key component of triple therapy, is the only nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) indicated for primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.10,11 The reason: Aspirin is more selective for cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) than other NSAIDs and irreversibly inhibits COX enzymes.11 The aspirin-induced decrease in thromboxane production leads to a decline in platelet activation and aggregation, which accounts both for aspirin’s beneficial cardiovascular effects and the associated risk of bleeding—aspirin’s most common adverse effect.12

Most major bleeds linked to aspirin use involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, primarily because of the drug’s direct and indirect effects on the GI mucosa.11-14 Aspirin’s toxicities are dose related, but its antiplatelet properties do not appear to be.14

Adding a thienopyridine

Thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs indicated for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events after ACS or PCI-S include ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel.15 Ticlopidine, the first such agent approved in the United States, is rarely used because of potential neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura.16

Clopidogrel, the most commonly used agent for the purpose of secondary prevention, is the only thienopyridine with trial data for triple therapy.17 Clopidogrel’s antiplatelet effect, however, is highly dependent on specific cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzymes for conversion to its active metabolite, and can be impaired by genetic variations in CYP 2C19, as well as by medication interactions. This has led to concern about the drug’s efficacy for secondary prevention of ACS.6,17,18 In 2010, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) added a black-box warning for clopidogrel, emphasizing the risk of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cardiovascular death in patients with defective CYP 2C19 activity.19

Prasugrel, approved by the FDA in 2009,20 is useful for patients who respond poorly to clopidogrel. In fact, inadequate platelet inhibition with clopidogrel has prompted some physicians to choose prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.

While prasugrel may have greater efficacy compared with clopidogrel in preventing reinfarction, it appears to have a higher bleeding rate.15,17 Because of its bleeding profile, prasugrel is not recommended for patients >75 years unless they are at high risk for MI (prior MI or diabetes), and it is contraindicated for patients with a history of stroke. Caution is needed when prasugrel is prescribed for patients who weigh <132 lb (consider a maintenance dose of 5 mg/d rather than the usual 10 mg/d) or have an increased propensity to bleed.15

Warfarin provides the anticoagulant component of triple therapy

Until late last year, when dabigatran received FDA approval for use in stroke prevention,21 warfarin was the only oral anticoagulant available in the United States. (To learn more about dabigatran, which is not included in this review because of the lack of evidence regarding its use in triple therapy, see “Time to try this warfarin alternative?”.)

Because multiple drug, food, and disease state interactions can interfere with warfarin therapy, frequent monitoring to maintain a target international normalized ratio (INR) is required.22,23 (See Patient on warfarin? Steer clear of these drugs, in “Avoiding drug interactions: Here’s help,” J Fam Pract. 2010;59: 322-329).

Bridge therapy. Warfarin requires several days to reach its full effect, so anticoagulation with a more immediate-acting medication, such as a low-molecular-weight heparin or fondaparinux, is often used until the INR goal is reached.22,23 Thus, there are instances in which patients requiring triple therapy are actually receiving 4 drugs that increase bleeding risk.

When (or whether) to consider triple therapy

While triple therapy may be an option for patients with atrial fibrillation and ACS or PCI-S, there is no validated scoring system to aid in treatment decisions.24 As already noted, selecting the optimal therapy requires an individual assessment of the patient’s risk of reinfarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and bleeding complications.

Risk factors for reinfarction and stent thrombosis are the same ones that increase the risk of ACS initially, and include diabetes mellitus, heart failure, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.10,16 Advanced age; uncontrolled hypertension; chronic conditions such as peripheral vascular disease, anemia, and peptic ulcer disease; and a history of major bleeds are associated with an increased risk of bleeding. 24,25

In a retrospective trial evaluating independent predictors of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent PCI-S,1 the researchers identified several factors that increased the risk of early major bleeding (within 48 hours of stent placement): the use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, stenting of ≥3 vessels, or left main artery disease. Factors that significantly increased the risk of major bleeding more than 48 hours after the procedure included triple therapy, an early major bleed, and baseline anemia.1

Drug combinations: What to consider

In addition to determining whether a patient is a good candidate for triple therapy, it is crucial to consider the choice of drugs. Benefits of prasugrel, compared with clopidogrel, include fewer drug interactions, less resistance to platelet inhibition, more rapid platelet inhibition after an oral loading dose, and higher levels of platelet inhibition during maintenance dosing.15,17

Improved outcomes are another potential benefit, according to TRITON-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 38,17 a large randomized prospective trial comparing the use of prasugrel with clopidogrel in triple therapy. Among study participants, the primary outcome rate—the combined incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke—was 9.9% for those on prasugrel vs 12.1% for the clopidogrel group (hazard ratio [HR]=0.81; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.90, P<.001).17 The rate of TIMI major bleeding, however, was higher among those on prasugrel (HR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.03-1.68, P=.03). The evidence suggests that for every 1000 patients treated with prasugrel vs clopidogrel, 24 primary outcomes would be prevented but there would be 10 additional bleeding events.17,26

CASE Anthony D’s risk for stroke, infarction, and stent thrombosis—based on his history of diabetes and hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and PCI-S—and absence of independent bleeding risk factors make him a good candidate for triple therapy. Because the patient is at high risk, the physician starts him on 2 anticoagulants—warfarin (5 mg at bedtime) and enoxaparin (125 mg every 12 hours)—on the evening of his second day in the hospital. On Day 3, clinicians test Anthony’s prothrombin time/international normalized ratio (PT/INR) and P2Y12 function assay, which measure 14.9/1.1 and 8% platelet inhibition, respectively.

The patient is discharged on the following medication schedule: enoxaparin 125 mg every 12 hours, to be discontinued after 3 days; warfarin 5 mg daily, prasugrel 10 mg daily, and aspirin 81 mg daily; metoprolol succinate 100 mg daily; lisinopril 10 mg daily; rosuvastatin 10 mg daily; glyburide-metformin 5 mg/500 mg, 2 tablets twice daily; and insulin glargine 20 units at bedtime.

Safety and efficacy: Do the benefits outweigh the risk?

Safety is central to the continuing controversy surrounding the use of triple therapy.6,9 To date, however, no randomized prospective studies have evaluated its benefits and risks.

Numerous retrospective studies and case series have assessed the risk of bleeding associated with triple therapy.6 Several studies compared triple therapy with dual antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation, and found a several-fold increase in both major and minor bleeding events in the triple therapy group.6

Few trials have assessed both the safety and the efficacy of triple therapy, however. One exception is a large retrospective trial, published in 2008.2 The researchers found that triple therapy significantly reduced the incidence of major cardiac events (death, acute MI, and target lesion revascularization); all-cause mortality; and major adverse effects (ie, any major cardiovascular event, major bleeding complication, and/or stroke), with no statistically significant increase in major bleeding events compared with patients on antiplatelet therapy without anticoagulation.2

The results of this trial, like those of other studies evaluating triple therapy, were weakened by variance in both the duration of antithrombotic therapy and the drug therapies studied. This limitation was off set, however, by multivariant analysis and well-documented follow-up.2 Despite the researchers’ findings, however, the results of other trials (and our knowledge of the mechanisms of action of the drug components) suggest that triple therapy significantly increases bleeding risk. For patients who would likely benefit from it but face an increased bleeding risk, there are ways to mitigate risk.

Prescribing triple therapy, while mitigating the risks

If bleeding is a serious concern in a patient who would benefit from triple therapy, the drug regimen may be adjusted. Options include:

- targeting a lower INR (2.0-2.5 vs the standard 2.0-3.0).6 While various trials have found a 2.0 to 3.0 range to reduce the risk of stroke, none has compared it with a lower range to evaluate reduction in bleeding risk.27 One potential benefit of trying to maintain a lower INR is the decrease in deviations into the 3.0 to 4.0 range, which is associated with an increased bleeding risk.28 However, lowering the INR target is not supported by any literature.1,18

- using low-dose aspirin therapy after PCI-S

- limiting the thienopyridine component of triple therapy to one month after ACS or PCI-S.6

When the risks of triple therapy outweigh the benefits because of an exceedingly high bleeding risk, single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin is another option to consider.

CASE [H17012] Anthony D’s discharge instructions called for an 81 mg daily dose of aspirin, as opposed to the 325-mg dose for the first 3 months of triple therapy after stent placement recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for unstable angina/ non-ST segment elevated MI.1 Although the patient had no independent bleeding risk, his physician selected the lower dose of aspirin to mitigate the increased bleeding risk posed by the use of prasugrel as a component of triple therapy.6

Lower aspirin dose. Pharmacodynamic studies support the use of a lower dose of aspirin, finding that serum thromboxane is completely inhibited by a maintenance dose as low as 30 mg/d in healthy individuals and 50 mg/d for those with chronic stable angina.14 Using low-dose aspirin for the secondary prevention of ACS when triple therapy is indicated is likely to reduce GI toxicities as well as bleeding risk.

Reduce the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. According to the ACC/AHA guidelines, thienopyridine therapy can be limited to one month in patients who are medically managed or have had a bare metal stent placed if there is concern about the patient’s risk of bleeding.6,10 Based on the findings of the one study that found triple therapy to be an independent predictor of major bleeds, this approach seems reasonable.1 It is called into question, however, by another recent trial, which found that patients on dual antiplatelet therapy for one year (vs one month) had a statistically significant improvement in cardiovascular outcomes.16

Before limiting a patient’s thienopyridine therapy to one month, consider his or her risk of reinfarction. If it is high, continuing the thienopyridine for at least one year is likely to provide the most benefit.

The largest triple therapy trial to date compared the efficacy of triple therapy vs dual therapy (a single antiplatelet agent plus warfarin) in patients with ACS and an indication for warfarin therapy.3 This trial found no statistically significant differences in the combined occurrence of death, stroke, unscheduled PCI, and MI between the 2 treatment groups. (Bleeding risk was not evaluated.) Stroke was significantly increased in the group that received therapy with warfarin and a single antiplatelet agent, with this caveat: The occurrence of stroke was so low overall that no conclusions could be reached from this difference.3

One problem with this trial, and with others evaluating triple therapy, has to do with the lack of consistency, as well as the duration. The warfarin and single antiplatelet group, for example, may have included patients who were receiving only warfarin, aspirin, or clopidogrel by 6 months after initiating treatment.3 Thus, although reinfarction or stent thrombosis after ACS or PCI-S typically occurs within the first few months, any triple therapy trial that lasts less than a year is likely to report skewed results. JFP

CORRESPONDENCE

Haley M. Phillippe, PharmD, BCPS, Auburn University Harrison School of Pharmacy, University of Alabama Birmingham School of Medicine?Huntsville, 301 Governors Drive, Huntsville, AL 35801; mccrahl@auburn.edu

1. Manzano-Fernandez S, Pastor FJ, Marin F, et al. Increased major bleeding complications related to triple antithrombotic therapy usage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary artery stenting. Chest. 2008;134:559-567.

2. Ruiz-Nodar JM, Marin F, Hurtado JA, et al. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in 426 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:818-25.

3. Nguyen MC, Lim YL, Walton A, et al. Combining warfarin and antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events: is it safe and effective to use just one antiplatelet agent? Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1717-1722.

4. Gilard M, Blanchard D, Helft G, et al. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with anticoagulants undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting (from STENTIng and oral anticoagulants [STENTICO]). Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:338-342.

5. Hansen ML, Sorensent R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1433-1441.

6. Hermosillo AJ, Spinler SA. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin: is the combination appropriate and effective or inappropriate and too dangerous? Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:790-805.

7. Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, et al. Warfarin plus aspirin after myocardial infarction or the acute coronary syndrome: meta-analysis with estimates of risk and benefit. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:241-250.

8. Eikelboom JM, Hirsh J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:255-263.

9. Triple antithrombotic therapy Pharm Lett/Prescr Lett. 2009;25:250901.-

10. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. ACC/AHA guideline revision. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

11. Furst DE, Ulrich RW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, and drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;573-598.

12. Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. The eicosanoids: prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and related compounds. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;293-308.

13. Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM, et al. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:379-386.

14. Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, et al. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2018-2024.

15. Lexi-Comp [database online]. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, Inc. Copyright 1978-2007. Available at: http://www.crlonline.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 5, 2010.

16. Spinler SA, Rees C. Review of Prasugrel for the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:383-95.

17. Spinler SA, Denus SD, et al. Acute coronary syndromes. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;249-277.

18. Plavix [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb/ Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership; 2010.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA announces new boxed warning on Plavix. March 12, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/Press Announcements/ucm204253.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

20. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Effient to reduce the risk of heart attack in angioplasty patients. July 10, 2009. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/News-room/PressAnnouncements/ucm171497.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

21. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Pradaxa to prevent stroke in people with atrial fibrillation. October 19, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm230241.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

22. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, et al. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines (8Th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl):160S-198S.

23. Haines ST, Witt DM, Nutescu EA. Venous thromboembolism. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;331-369.

24. Lip G. The balance between stroke prevention and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation: a delicate balance revisited. Stroke. 2008;39:1406-1408.

25. The Warfarin Antiplatelet Vascular Evaluation Trial Investigators. Oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy and peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:217-227.

26. Schafer JA, Kjesbo NK, Gleason PP. Critical review of prasugrel for formulary decision makers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:335-343.

27. Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2008;133(suppl):546S-592S.

28. Price MJ. Bedside evaluation of thienopyridine antiplatelet therapy. Circulation. 2009;119:2625-2632.

1. Manzano-Fernandez S, Pastor FJ, Marin F, et al. Increased major bleeding complications related to triple antithrombotic therapy usage in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary artery stenting. Chest. 2008;134:559-567.

2. Ruiz-Nodar JM, Marin F, Hurtado JA, et al. Anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy use in 426 patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:818-25.

3. Nguyen MC, Lim YL, Walton A, et al. Combining warfarin and antiplatelet therapy after coronary stenting in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events: is it safe and effective to use just one antiplatelet agent? Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1717-1722.

4. Gilard M, Blanchard D, Helft G, et al. Antiplatelet therapy in patients with anticoagulants undergoing percutaneous coronary stenting (from STENTIng and oral anticoagulants [STENTICO]). Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:338-342.

5. Hansen ML, Sorensent R, Clausen MT, et al. Risk of bleeding with single, dual, or triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1433-1441.

6. Hermosillo AJ, Spinler SA. Aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin: is the combination appropriate and effective or inappropriate and too dangerous? Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:790-805.

7. Rothberg MB, Celestin C, Fiore LD, et al. Warfarin plus aspirin after myocardial infarction or the acute coronary syndrome: meta-analysis with estimates of risk and benefit. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:241-250.

8. Eikelboom JM, Hirsh J. Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:255-263.

9. Triple antithrombotic therapy Pharm Lett/Prescr Lett. 2009;25:250901.-

10. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. ACC/AHA guideline revision. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

11. Furst DE, Ulrich RW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, and drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;573-598.

12. Smyth EM, FitzGerald GA. The eicosanoids: prostaglandins, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and related compounds. In: Katzung BG. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;293-308.

13. Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Brennan DM, et al. Aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease: the association of aspirin dose and clopidogrel with thrombosis and bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:379-386.

14. Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, et al. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2018-2024.

15. Lexi-Comp [database online]. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp, Inc. Copyright 1978-2007. Available at: http://www.crlonline.com/crlsql/servlet/crlonline. Accessed November 5, 2010.

16. Spinler SA, Rees C. Review of Prasugrel for the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:383-95.

17. Spinler SA, Denus SD, et al. Acute coronary syndromes. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;249-277.

18. Plavix [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb/ Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership; 2010.

19. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA announces new boxed warning on Plavix. March 12, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/Press Announcements/ucm204253.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

20. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Effient to reduce the risk of heart attack in angioplasty patients. July 10, 2009. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/News-room/PressAnnouncements/ucm171497.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

21. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Pradaxa to prevent stroke in people with atrial fibrillation. October 19, 2010. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm230241.htm. Accessed March 11, 2011.

22. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, et al. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists. American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Guidelines (8Th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl):160S-198S.

23. Haines ST, Witt DM, Nutescu EA. Venous thromboembolism. In: Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008;331-369.

24. Lip G. The balance between stroke prevention and bleeding risk in atrial fibrillation: a delicate balance revisited. Stroke. 2008;39:1406-1408.

25. The Warfarin Antiplatelet Vascular Evaluation Trial Investigators. Oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy and peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:217-227.

26. Schafer JA, Kjesbo NK, Gleason PP. Critical review of prasugrel for formulary decision makers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:335-343.

27. Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2008;133(suppl):546S-592S.

28. Price MJ. Bedside evaluation of thienopyridine antiplatelet therapy. Circulation. 2009;119:2625-2632.

Statin neuropathy?

It took 13 years before an 82-year-old patient learned what had caused the pain and tingling in his feet that he’d been living with all those years.

In 1996 he had a coronary stent insertion, and after the procedure, began taking a beta-blocker and atorvastatin. He subsequently noticed a sensory change in his toes bilaterally. This slowly progressed to paresthesia in the anterior segments of both feet on the plantar and dorsal surfaces.

A nerve conduction study (TABLE) confirmed the presence of a sensorimotor polyneuropathy, despite the fact that he did not have diabetes, or any other condition known to predispose him to polyneuropathy. The patient’s left sural peak latency and amplitude, a measure of sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), was absent. The right sural SNAP demonstrated a mild decrease of the amplitude with a normal distal latency. The left peroneal F wave response (a measure of nerve conduction velocity) was within the upper limits of normal. The left tibial F wave response was normal. The left peroneal and left tibial CMAPs (compound muscle action potentials) were normal.

A nerve biopsy was not considered for this patient because its main use is in the identification of specific lesions that are generally lacking in acquired, distal, symmetrical sensory neuropathy. (Plus, biopsy gives no more information than electrophysiological tests.)1

TABLE

A look at the patient’s nerve conduction results

| Nerve and site | Peak latency (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Segment | Latency difference (ms) | Distance (mm) | Conduction velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory nerve conduction | ||||||

| Sural nerve (left) Lower leg | 0.0 | 0.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Sural nerve (right) Lower leg | 4.0 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Motor nerve conduction | ||||||

| Peroneal nerve (left) Ankle | 4.3 | 1.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Fibular head | 13.2 | 1.6 | Ankle-fibular head | 8.9 | 358 | 40 |

| Knee | 16.2 | 1.5 | Fibular head-knee | 3.0 | 115 | 38 |

| Tibial nerve (left) Ankle | 4.2 | 2.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Popliteal fossa | 15.4 | 2.6 | Ankle-popliteal fossa | 11.2 | 450 | 40 |

| ms, millisecond; m/s, meters/second; mV, millivolt; N/A, not applicable. | ||||||

Connecting the dots years later

Neither the patient’s cardiologist, nor his general physician, was aware of any connection between statins and neuropathy, but the patient stopped taking the drug in 2003. And while the neuropathy never went away, it did subside slightly to a fairly constant level.

In August 2009, because of suboptimal levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and C-reactive protein, his cardiologist prescribed simvastatin 5 mg daily.

On the third day, the patient experienced a marked increase of the neuropathy, which extended above his ankles. Cutaneous sensory loss became more extensive and pronounced. He stopped the statin that day, but the paresthesia did not lessen. In addition, he developed intermittent pins and needles in both hands and some instability in his gait. To date, there has been no improvement in his symptoms. Nerve conduction studies were not repeated.

Discussion: The various causes of neuropathy

In 2003, this journal published a question, “Do statins cause myopathy?”2 The item concluded that if they did, the risk was very low, although isolated case reports suggested a myopathy risk for all statins, ranging from benign myalgia to fatal rhabdomyolysis.

It is now widely acknowledged that statins can cause myopathy in as many as 10% of patients taking these drugs.3

The involvement of peripheral nerves bilaterally, usually affecting distal axons of the feet and legs, is the most common form of polyneuropathy and its presentation generally excludes consideration of other forms of neuropathy, such as the mononeuropathies and neuritis. Affected nerves may be sensory, motor, or autonomic.

Symptoms include all varieties of paresthesia, sensory loss, muscle weakness, and pain. The most common cause is diabetes mellitus, which must be the first condition to be excluded. Other conditions, such as vitamin deficiencies, have also been linked with this complication.

Laboratory work-up, aside from blood glucose testing for diabetes, should include routine complete blood count and SMA-12, as well as thyroid profile and vitamin deficiency status (particularly vitamins B12 and B1).

Is a medication—perhaps a statin— to blame?

Numerous drugs are known to be associated with neuropathy.4 These include chemotherapy agents (cisplatin, taxoids), certain antibiotics, nucleoside analogs, dapsone, metronidazole, and certain cardiovascular drugs (amiodarone, hydralazine, statins).4 Recent work has indicated that simvastatin inhibits central nervous system remyelination by blocking progenitor cell differentiation.5 By extension, it probably inhibits progenitor cells in the peripheral nervous system.

The possibility of an association between statins and peripheral neuropathy has expanded from several case reports to a population-based study involving 465,000 subjects.6 More recently, a review of the literature7 concluded that exposure to statins may increase the risk of polyneuropathy and that statins should be considered the cause when other etiologies have been excluded. The authors suggested that the incidence of peripheral neuropathy due to statins is approximately 1 person/14,000 person-years of treatment.

An exposure, a “break,” and another exposure

The reappearance or aggravation of symptoms after cessation of statin therapy and subsequent second exposure has been described in the literature.8 In the case described here, the time between re-exposure and symptoms was suggestive of a T-cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction. It has been proposed that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha released by T cells may contribute to the pathogenesis of demyelinating neuropathy.9

Managing this patient’s lipid levels going forward

The patient described in this report is now receiving ezetimibe 10 mg daily, which reduces the absorption of cholesterol from the diet, and niacin 2 g daily, which he can tolerate. His most recent fasting lipid panel showed the following results: cholesterol, 171 mg/dL; LDL cholesterol, calculated, 113 mg/dL; HDL cholesterol, 37 mg/dL; triglycerides, 106 mg/dL; and non-HDL cholesterol, 134 mg/dL.

Controlling the patient’s pain was another matter. Drugs commonly used for paresthesia and pain (including opiates) did not provide relief. Pregabalin (Lyrica) also had little effect. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation did not perceptibly lessen his symptoms, and was also discontinued.

At the present time, this patient is not on any specific treatment for his neuropathy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Walter F. Coulson, MD, Department of Pathology, UCLA, CHS, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1732; wcoulson@mednet.ucla.edu

1. Said G. Indications and usefulness of nerve biopsy. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1532-1535.

2. Daugird AJ, Crowell K. Do statins cause myopathy? J Fam Pract. 2003;52:973-976.

3. Joy TR, Hegele RA. Narrative review: Statin-related myopathy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:858-868.

4. Weimer LH. Medication-induced peripheral neuropathy. Curr Neurosci Rep. 2003;3:86-92.

5. Miron VE, Zehntner SP, Kuhlmann T, et al. Statin therapy inhibits remyelination in the central nervous system. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1880-1890.

6. Gaist D, Jeppesen U, Andersen M, et al. Statins and risk of polyneuropathy: a case-control study. Neurology. 2002;58:1333-1337.

7. Chong PH, Boskovich A, Stevkovic N, et al. Statin-associated peripheral neuropathy: review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24:1194-1203.

8. Phan T, McLeod JG, Pollard JD, et al. Peripheral neuropathy associated with simvastatin. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:625-628.

9. Stübgen JP. Tumor necrosis factor–alpha antagonists and neuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:281-292.

It took 13 years before an 82-year-old patient learned what had caused the pain and tingling in his feet that he’d been living with all those years.

In 1996 he had a coronary stent insertion, and after the procedure, began taking a beta-blocker and atorvastatin. He subsequently noticed a sensory change in his toes bilaterally. This slowly progressed to paresthesia in the anterior segments of both feet on the plantar and dorsal surfaces.

A nerve conduction study (TABLE) confirmed the presence of a sensorimotor polyneuropathy, despite the fact that he did not have diabetes, or any other condition known to predispose him to polyneuropathy. The patient’s left sural peak latency and amplitude, a measure of sensory nerve action potential (SNAP), was absent. The right sural SNAP demonstrated a mild decrease of the amplitude with a normal distal latency. The left peroneal F wave response (a measure of nerve conduction velocity) was within the upper limits of normal. The left tibial F wave response was normal. The left peroneal and left tibial CMAPs (compound muscle action potentials) were normal.

A nerve biopsy was not considered for this patient because its main use is in the identification of specific lesions that are generally lacking in acquired, distal, symmetrical sensory neuropathy. (Plus, biopsy gives no more information than electrophysiological tests.)1

TABLE

A look at the patient’s nerve conduction results

| Nerve and site | Peak latency (ms) | Amplitude (mV) | Segment | Latency difference (ms) | Distance (mm) | Conduction velocity (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory nerve conduction | ||||||

| Sural nerve (left) Lower leg | 0.0 | 0.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Sural nerve (right) Lower leg | 4.0 | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |