User login

Dupilumab for Off-Label Treatment of Moderate to Severe Childhood Atopic Dermatitis

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy with a history of shellfish anaphylaxis, pollen allergy, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, frequent headaches and ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, vitiligo, warts, and cold sores presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread crusting, cracking, red rash that had been present since 6 months of age. The patient’s mother reported that he had many sleepless nights from uncontrolled itching. His medications included albuterol solution for nebulization, loratadine, and montelukast. Prior to the current presentation he had been treated with triamcinolone and betamethasone creams by the pediatrician. Despite compliance with topical therapy, his mother stated the itching persisted and lesions lingered with minimal improvement. He also was treated with oral corticosteroids for episodic sinusitis and bronchitis, which was beneficial to the skin lesions for only a short duration. The patient was adopted and therefore his family history was unavailable.

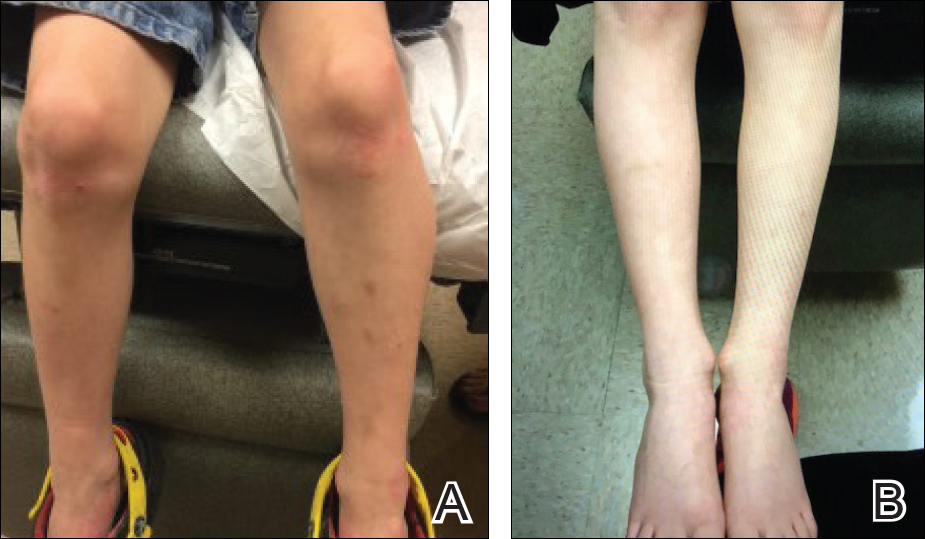

During physical examination, the patient was in the fetal position on the examination table and appeared uncomfortable, scratching himself. The patient admitted to severe widespread itching and burning. On skin examination, multiple thick, lichenified, highly pruritic plaques coalesced on the knees, ankles, arms, and wrists, and very discreet scaly patches were present on the scalp. Annular patches covered 50% of the patient’s body, with highly inflamed lesions concentrated in skin folds (Figure 1), leading to diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Over the course of several months, a number of topical therapies were prescribed. The calcineurin inhibitor pimecrolimus cream 1% proffered minimal relief, and the patient experienced burning with crisaborole despite attempts to combine it with emollients and topical corticosteroids. The patient and his mother favored intermittent use of topical corticosteroids alone; however, he experienced frequent disease flares. Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray and mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment were included in the treatment regimen as adjunctive topical therapies. Additionally, the patient underwent bleach and vinegar bath therapy without success.

Although UVA and UVB phototherapy has shown to be safe and effective in children, our patient had limited treatment options due to insurance restrictions. The patient had been taking oral corticosteroids on and off for years prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic.

Our patient weighed approximately 40 lb and was prescribed methotrexate 5 mg once weekly for 2 weeks along with oral folic acid 1 mg once daily, except when taking the methotrexate. Laboratory workup was ordered at 2- and then 4-week intervals. After 2 weeks of treatment, methotrexate was increased to 10 mg once weekly. His asthma was carefully monitored by the allergist, and his mother was instructed to stop the medication if he had worsening shortness of breath or exacerbation of asthma symptoms. He tolerated methotrexate at 10 mg once weekly well without clinical side effects for 6 months. His mother observed less frequent ear and sinus infections during methotrexate therapy; however, he developed anemia over time and the methotrexate was discontinued. Understanding the nature of off-label use in administering dupilumab, the patient’s mother consented to a scheduled dosage of 300 mg subcutaneous (SQ) injection every month in the absence of a loading dose with the assumption of future modifications pending his response to therapy.

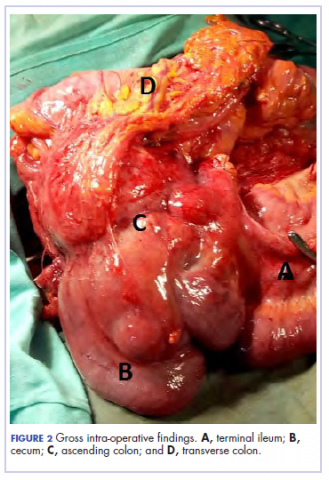

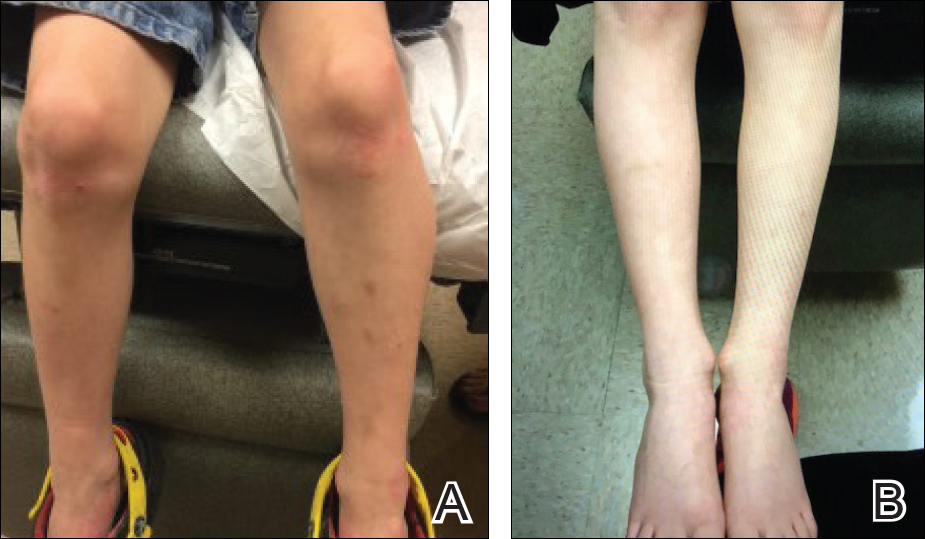

Five days after treatment with a 300-mg SQ dupilumab injection, the patient returned to clinic for evaluation of a vesicular rash with subsequent peeling confined to the shoulders (Figure 2). He and his mother denied any UV exposure, citing he had been completely out of the sun. He denied constitutional symptoms including fever, malaise, swelling, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, enlarged lymph glands, difficulty urinating, breathing, or neurological disturbance. Upon physical examination, the rash was not considered to be a drug eruption. Had a mild drug reaction been suspected, a careful rechallenge, weighing the risks and benefits, would have been considered and was discussed with the mother and patient. New-onset or worsening eye symptoms should be reported; therefore, a referral to ophthalmology was prompted due to our patient’s history of rhinoconjunctivitis and persistent conjunctival injection observed early after initiating dupilumab therapy. Nothing remarkable was found.

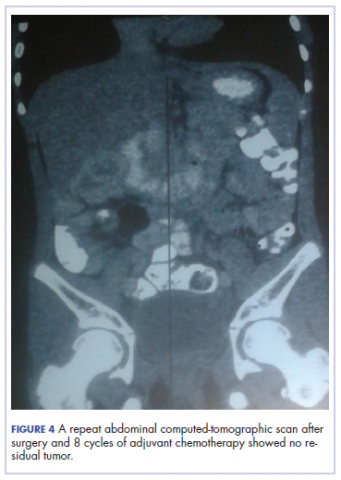

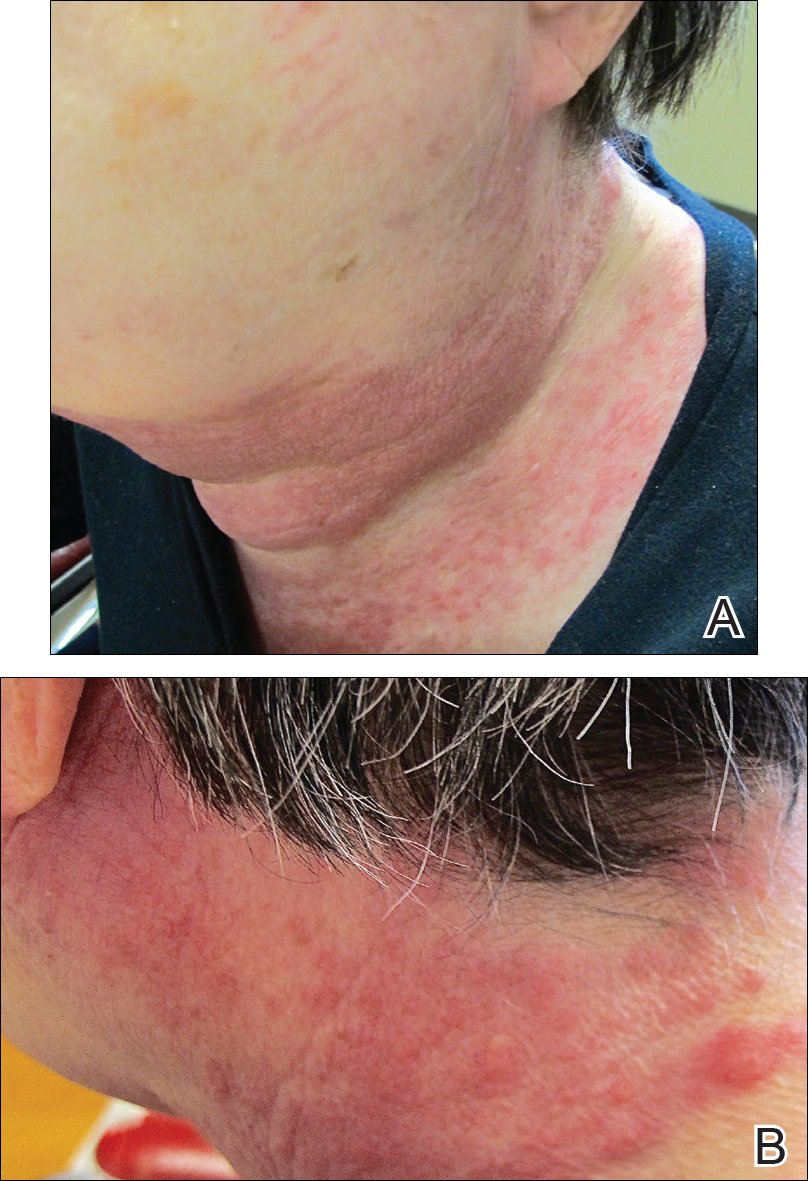

The patient was eager to continue dupilumab therapy due to considerable reduction of itching and elimination of lesions. His mother reported that the greatest benefit 1 month after starting dupilumab was almost no itching (Figure 3A). Additionally, he denied headache or nasopharyngitis at his 1-month office visit. After 2 months of dupilumab therapy, the patient reported persistent lesions on the feet and ankles despite concomitant treatment with topical corticosteroids. The decision to increase the dupilumab dose to 300-mg SQ injection once every 3 weeks for a total of 3 doses was made, which resulted in resolution of all lesions (Figure 3B).

Comment

Prevalence and Pathogenesis

Atopic dermatitis affects 31.6 million individuals in the United States, with 17.8 million experiencing moderate to severe lesions.1 The current prevalence of AD in the pediatric population ranges from 10% to 30% compared to 2% to 10% in adults. Fortunately, up to 70% of young children enter remission or improve by 12 years of age. Atopic diatheses may simultaneously occur, which includes asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis.2

Complications from AD include bacterial and viral infections and ocular disease. Furthermore, impaired growth in stature has been correlated with individuals who have extensive disease.2 Of interest, our 7-year-old patient gained 7 lb and grew almost 3 in within 6 months of being on immunosuppressant therapy. Children with AD have poorer sleep efficiency in contrast to children without AD.3 Eczema is associated with more frequent headaches in childhood, especially in those with sleep disturbances,4 as our patient had experienced prior to systemic therapy.

The pathogenesis of AD is complex, and one must take into consideration the multiple cellular activities including inflammatory mechanics in the absence of IgE-mediated sensitization, epidermal barrier changes, epicutaneous sensitization, dendritic cell roles, T-cell responses and cytokine orchestrations, actions of microbial colonization, and involvement of autoimmunity.5 Select patients with AD have IgE antibodies focused against self-proteins. Disease severity correlates with ubiquity of these antibodies. Moreover, certain autoallergens induce helper T cell (TH1) responses.5 Circulating TH2 cytokines and chemokines IL-4, IL4ra, and IL-13 also have been linked to AD pathogenesis. Additionally, nonlesional skin abnormalities have been observed.6 Most recently, researchers have identified a caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) gene mutation possibly leading to AD.7 Clinically, our patient responded favorably to dupilumab, which inhibits TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL13. He experienced a considerable decrease in itching and inflammation and reduced lesion count after 1 month of treatment with dupilumab. No skin lesions were identified on visual examination at week 17 and inevitably the patient discontinued messy topicals.

Treatment Options

Because AD is characterized by episodes of remission and relapse, management generally is comprised of trigger avoidance, including known allergens and irritants; a skin care regimen that promotes healthy epidermal barrier function; anti-inflammatory therapies to control both flares and subclinical inflammation; and adjunctive therapy for additional symptomatic control (eg, phototherapy, stabilized hypochlorous acid, topical antibiotic treatment) when needed. Avoidance of excessive washing or irritants, food provocation, and emotional stress, as well as toleration of body temperature fluctuations and humidity, is recommended to amend exacerbations.5

Current topical therapies include emollients; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and crisaborole, a newer phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. There are a number of emollients and moisturizers available, and one over-the-counter preparation showed tolerability and improved skin hydration in AD patients and demonstrated less transepidermal water loss than the control group.8 Ointments such as petrolatum usually do not include ingredients such as preservatives, gelling agents, or humectants that can promote stinging or burning.9 Topical corticosteroids, which ameliorate inflammation by subduing proinflammatory cytokine expression, have been the mainstay of treatment for more than 60 years; however, caution should be used due to the potential for side effects, mainly but not limited to systemic absorption in children, development of striae, and skin atrophy. Calcineurin inhibitors prohibit T-cell activity, modify mast cell response, and decrease dendritic cells in the epidermis. Since 2000, calcineurin inhibitors have been utilized as steroid-sparing agents10; however, prior authorization is still necessary with some insurance providers. Crisaborole ointment 2%, the newest topical agent for AD treatment in the market, has shown improvement of erythema, exudation, and pruritus. Approved for patients aged 2 years and older, twice-daily application of topical crisaborole as a steroid-sparing agent has rendered AD symptom relief.11 It has been reported that 4% of patients encounter stinging or burning with topical crisaborole application, whereas up to 50% of calcineurin inhibitors induce these adverse effects.12 Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray or gel acts as an antipruritic and antimicrobial agent, relieving pain associated with skin irritations. Topical antimicrobial preparations such as mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment can reduce Staphylococcus colonization when applied in the nasal passage as well as to affected skin lesions.2

In children, UVA and UVB phototherapy has proven safe and effective and can be utilized in AD when suitable.13 When patients inadequately respond to topical therapies and phototherapy, systemic immunomodulatory agents have been recommended as treatment options.A child’s developing immune system indeed may be sensitive to systemic therapies as the innate immune system fully matures in adolescence and his/her adaptive immune system is undergoing vigorous definition.14 Systemic immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have been used off label for years and pose certain challenges in being identified as durable therapies due to potential side effects. Cyclosporine is effective for the treatment of AD; however, long-term administration should be dosed up to a 12-month period and then stopped to decrease cumulative exposure to the drug. Therefore, further treatment options must be considered. For children, cyclosporine should be administered in a dose of 3 to 6 mg/kg daily. Fluctuations in blood pressure and renal function should be monitored. The recommended pediatric dose for azathioprine is 1 to 4 mg/kg daily with laboratory monitoring, particularly of liver enzymes and complete blood cell count. Obtaining the patient’s thiopurine methyltransferase level may aid in dosing. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are common. Phototherapy is not advised in conjunction with azathioprine due to an increased risk of photocarcinogenicity.13 The literature supporting mycophenolate mofetil in children with AD is limited.

Biologic therapies targeting IgE, B-lymphocyte antigen CD20, IL-5, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, TH17 cells, IL-12, IL-23, interferon gamma, IL-6 receptors, tumor necrosis factor, phosphodiesterase 4, Janus kinase, chymase, and nuclear receptors expressed on adipocytes and immune cells have undergone investigation for treatment of AD.17 Additionally, biologic agents targeting IL-31, IL-13, and IL-22 also have been evaluated.1 Currently, there are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic agents for moderate to severe childhood AD.

Dupilumab, an IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα antagonist, recently has been approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults but not yet for children. Potential side effects include nasopharyngitis, headache, hypersensitivity reactions, and ocular symptoms,11 namely keratitis and conjunctivitis.18 Less than 1% of patients experienced keratitis in clinical trials, while conjunctivitis was reported in 4% of patients taking dupilumab with topical corticosteroids at 52 weeks.18 However, possible ocular findings on slit-lamp examination in AD patients include atopic keratoconjunctivitis, blepharitis, palpebral conjunctival scarring, papillary conjunctival reaction, Horner-Trantas dots, keratoconus, and atopic cataracts. Spontaneous retinal detachment is seen more commonly in individuals with AD than in the general population.19

In clinical trials, hypersensitivity reactions included urticaria and serum sickness or serum sickness–like reactions in less than 1% of patients taking dupilumab.18

Conclusion

Childhood AD can be debilitating, and affected individuals often lead a poorer quality of life if left untreated. Embarrassment and isolation are commonly experienced. Increased responsibility and work in tending for a child with eczema may result in parental exhaustion.21 As with psoriasis, AD can impair activity and productivity.22 Currently, dupilumab has proven to positively impact health-related quality of life for adults.23 Pending the outcome of ongoing pediatric clinical trials, dupilumab may become a benchmark therapy for children younger than 18 years.

- Samalonis L. What’s new in eczema and atopic dermatitis research. The Dermatologist. November 19, 2015. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/whats-new-eczema-and-atopic-dermatitis-research. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Habif T. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bonnet C, Pinczewski A, Cook L, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:160-180.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case control study [published online October 28, 2017]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Silverberg J. Association between childhood eczema and headaches: an analysis of 19 US population-based studies [published online August 29, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:492-499.e5.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:203-216.

- Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle S, Shemer A, et al. Non-lesional atopic dermatitis (AD) skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:954-964.

- Hilton L. AD gene mutation identified: discovery may lead to new therapeutic option for patients. Dermatol Times. 2017;38:30.

- Zeichner JA, Dryer L. Effect of CeraVe Healing Ointment on skin hydration and barrier function on normal and barrier-impaired skin. Poster presented at: Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic & Clinical Conference; January 15-16, 2016; Orlando, FL.

- Garg T, Rath G, Goyal AK. Comprehensive review on additives of topical dosage forms for drug delivery. Drug Delivery. 2015;22:969-987.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Koutnik-Fotopoulous E. Update on the latest eczema treatments. The Dermatologist. February 17, 2016. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/update-latest-eczema-treatments. Accessed August 16, 2018.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Sidbury R, Davis D, Cohen D, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents . J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- van der Merwe R, Gianella-Borradori A. Industry perspective on the clinical development of systemic products for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients with inadequate response to topical prescription therapy. Presented at: FDA Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting; March 9, 2015; Silver Spring, MD.

- Heller M, Shin HT, Orlow SJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: experience in 14 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:127-132.

- Callen JP, Kulp-Shorten CL. Methotrexate. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2013:169-181.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Dhingra N, Leung DY. New era of biological therapeutics in atopic dermatitis [published online January 16, 2013]. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:549-561.

- Dupixent [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Lowery RS. Ophthalmologic manifestations of atopic dermatitis clinical presentation. Medscape website. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1197636-clinical#b4. Updated September 7, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Lenz HJ. Management and preparedness for infusion and hypersensitivity reactions. Oncologist. 2007;12:601-609.

- Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984-992.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the Unites States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2017;77:274-279.

- Tsianakas A, Luger TA, Radin A. Dupilumab treatment improves quality of life in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial [published online January 11, 2018]. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:406-414.

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy with a history of shellfish anaphylaxis, pollen allergy, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, frequent headaches and ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, vitiligo, warts, and cold sores presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread crusting, cracking, red rash that had been present since 6 months of age. The patient’s mother reported that he had many sleepless nights from uncontrolled itching. His medications included albuterol solution for nebulization, loratadine, and montelukast. Prior to the current presentation he had been treated with triamcinolone and betamethasone creams by the pediatrician. Despite compliance with topical therapy, his mother stated the itching persisted and lesions lingered with minimal improvement. He also was treated with oral corticosteroids for episodic sinusitis and bronchitis, which was beneficial to the skin lesions for only a short duration. The patient was adopted and therefore his family history was unavailable.

During physical examination, the patient was in the fetal position on the examination table and appeared uncomfortable, scratching himself. The patient admitted to severe widespread itching and burning. On skin examination, multiple thick, lichenified, highly pruritic plaques coalesced on the knees, ankles, arms, and wrists, and very discreet scaly patches were present on the scalp. Annular patches covered 50% of the patient’s body, with highly inflamed lesions concentrated in skin folds (Figure 1), leading to diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Over the course of several months, a number of topical therapies were prescribed. The calcineurin inhibitor pimecrolimus cream 1% proffered minimal relief, and the patient experienced burning with crisaborole despite attempts to combine it with emollients and topical corticosteroids. The patient and his mother favored intermittent use of topical corticosteroids alone; however, he experienced frequent disease flares. Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray and mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment were included in the treatment regimen as adjunctive topical therapies. Additionally, the patient underwent bleach and vinegar bath therapy without success.

Although UVA and UVB phototherapy has shown to be safe and effective in children, our patient had limited treatment options due to insurance restrictions. The patient had been taking oral corticosteroids on and off for years prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic.

Our patient weighed approximately 40 lb and was prescribed methotrexate 5 mg once weekly for 2 weeks along with oral folic acid 1 mg once daily, except when taking the methotrexate. Laboratory workup was ordered at 2- and then 4-week intervals. After 2 weeks of treatment, methotrexate was increased to 10 mg once weekly. His asthma was carefully monitored by the allergist, and his mother was instructed to stop the medication if he had worsening shortness of breath or exacerbation of asthma symptoms. He tolerated methotrexate at 10 mg once weekly well without clinical side effects for 6 months. His mother observed less frequent ear and sinus infections during methotrexate therapy; however, he developed anemia over time and the methotrexate was discontinued. Understanding the nature of off-label use in administering dupilumab, the patient’s mother consented to a scheduled dosage of 300 mg subcutaneous (SQ) injection every month in the absence of a loading dose with the assumption of future modifications pending his response to therapy.

Five days after treatment with a 300-mg SQ dupilumab injection, the patient returned to clinic for evaluation of a vesicular rash with subsequent peeling confined to the shoulders (Figure 2). He and his mother denied any UV exposure, citing he had been completely out of the sun. He denied constitutional symptoms including fever, malaise, swelling, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, enlarged lymph glands, difficulty urinating, breathing, or neurological disturbance. Upon physical examination, the rash was not considered to be a drug eruption. Had a mild drug reaction been suspected, a careful rechallenge, weighing the risks and benefits, would have been considered and was discussed with the mother and patient. New-onset or worsening eye symptoms should be reported; therefore, a referral to ophthalmology was prompted due to our patient’s history of rhinoconjunctivitis and persistent conjunctival injection observed early after initiating dupilumab therapy. Nothing remarkable was found.

The patient was eager to continue dupilumab therapy due to considerable reduction of itching and elimination of lesions. His mother reported that the greatest benefit 1 month after starting dupilumab was almost no itching (Figure 3A). Additionally, he denied headache or nasopharyngitis at his 1-month office visit. After 2 months of dupilumab therapy, the patient reported persistent lesions on the feet and ankles despite concomitant treatment with topical corticosteroids. The decision to increase the dupilumab dose to 300-mg SQ injection once every 3 weeks for a total of 3 doses was made, which resulted in resolution of all lesions (Figure 3B).

Comment

Prevalence and Pathogenesis

Atopic dermatitis affects 31.6 million individuals in the United States, with 17.8 million experiencing moderate to severe lesions.1 The current prevalence of AD in the pediatric population ranges from 10% to 30% compared to 2% to 10% in adults. Fortunately, up to 70% of young children enter remission or improve by 12 years of age. Atopic diatheses may simultaneously occur, which includes asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis.2

Complications from AD include bacterial and viral infections and ocular disease. Furthermore, impaired growth in stature has been correlated with individuals who have extensive disease.2 Of interest, our 7-year-old patient gained 7 lb and grew almost 3 in within 6 months of being on immunosuppressant therapy. Children with AD have poorer sleep efficiency in contrast to children without AD.3 Eczema is associated with more frequent headaches in childhood, especially in those with sleep disturbances,4 as our patient had experienced prior to systemic therapy.

The pathogenesis of AD is complex, and one must take into consideration the multiple cellular activities including inflammatory mechanics in the absence of IgE-mediated sensitization, epidermal barrier changes, epicutaneous sensitization, dendritic cell roles, T-cell responses and cytokine orchestrations, actions of microbial colonization, and involvement of autoimmunity.5 Select patients with AD have IgE antibodies focused against self-proteins. Disease severity correlates with ubiquity of these antibodies. Moreover, certain autoallergens induce helper T cell (TH1) responses.5 Circulating TH2 cytokines and chemokines IL-4, IL4ra, and IL-13 also have been linked to AD pathogenesis. Additionally, nonlesional skin abnormalities have been observed.6 Most recently, researchers have identified a caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) gene mutation possibly leading to AD.7 Clinically, our patient responded favorably to dupilumab, which inhibits TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL13. He experienced a considerable decrease in itching and inflammation and reduced lesion count after 1 month of treatment with dupilumab. No skin lesions were identified on visual examination at week 17 and inevitably the patient discontinued messy topicals.

Treatment Options

Because AD is characterized by episodes of remission and relapse, management generally is comprised of trigger avoidance, including known allergens and irritants; a skin care regimen that promotes healthy epidermal barrier function; anti-inflammatory therapies to control both flares and subclinical inflammation; and adjunctive therapy for additional symptomatic control (eg, phototherapy, stabilized hypochlorous acid, topical antibiotic treatment) when needed. Avoidance of excessive washing or irritants, food provocation, and emotional stress, as well as toleration of body temperature fluctuations and humidity, is recommended to amend exacerbations.5

Current topical therapies include emollients; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and crisaborole, a newer phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. There are a number of emollients and moisturizers available, and one over-the-counter preparation showed tolerability and improved skin hydration in AD patients and demonstrated less transepidermal water loss than the control group.8 Ointments such as petrolatum usually do not include ingredients such as preservatives, gelling agents, or humectants that can promote stinging or burning.9 Topical corticosteroids, which ameliorate inflammation by subduing proinflammatory cytokine expression, have been the mainstay of treatment for more than 60 years; however, caution should be used due to the potential for side effects, mainly but not limited to systemic absorption in children, development of striae, and skin atrophy. Calcineurin inhibitors prohibit T-cell activity, modify mast cell response, and decrease dendritic cells in the epidermis. Since 2000, calcineurin inhibitors have been utilized as steroid-sparing agents10; however, prior authorization is still necessary with some insurance providers. Crisaborole ointment 2%, the newest topical agent for AD treatment in the market, has shown improvement of erythema, exudation, and pruritus. Approved for patients aged 2 years and older, twice-daily application of topical crisaborole as a steroid-sparing agent has rendered AD symptom relief.11 It has been reported that 4% of patients encounter stinging or burning with topical crisaborole application, whereas up to 50% of calcineurin inhibitors induce these adverse effects.12 Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray or gel acts as an antipruritic and antimicrobial agent, relieving pain associated with skin irritations. Topical antimicrobial preparations such as mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment can reduce Staphylococcus colonization when applied in the nasal passage as well as to affected skin lesions.2

In children, UVA and UVB phototherapy has proven safe and effective and can be utilized in AD when suitable.13 When patients inadequately respond to topical therapies and phototherapy, systemic immunomodulatory agents have been recommended as treatment options.A child’s developing immune system indeed may be sensitive to systemic therapies as the innate immune system fully matures in adolescence and his/her adaptive immune system is undergoing vigorous definition.14 Systemic immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have been used off label for years and pose certain challenges in being identified as durable therapies due to potential side effects. Cyclosporine is effective for the treatment of AD; however, long-term administration should be dosed up to a 12-month period and then stopped to decrease cumulative exposure to the drug. Therefore, further treatment options must be considered. For children, cyclosporine should be administered in a dose of 3 to 6 mg/kg daily. Fluctuations in blood pressure and renal function should be monitored. The recommended pediatric dose for azathioprine is 1 to 4 mg/kg daily with laboratory monitoring, particularly of liver enzymes and complete blood cell count. Obtaining the patient’s thiopurine methyltransferase level may aid in dosing. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are common. Phototherapy is not advised in conjunction with azathioprine due to an increased risk of photocarcinogenicity.13 The literature supporting mycophenolate mofetil in children with AD is limited.

Biologic therapies targeting IgE, B-lymphocyte antigen CD20, IL-5, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, TH17 cells, IL-12, IL-23, interferon gamma, IL-6 receptors, tumor necrosis factor, phosphodiesterase 4, Janus kinase, chymase, and nuclear receptors expressed on adipocytes and immune cells have undergone investigation for treatment of AD.17 Additionally, biologic agents targeting IL-31, IL-13, and IL-22 also have been evaluated.1 Currently, there are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic agents for moderate to severe childhood AD.

Dupilumab, an IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα antagonist, recently has been approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults but not yet for children. Potential side effects include nasopharyngitis, headache, hypersensitivity reactions, and ocular symptoms,11 namely keratitis and conjunctivitis.18 Less than 1% of patients experienced keratitis in clinical trials, while conjunctivitis was reported in 4% of patients taking dupilumab with topical corticosteroids at 52 weeks.18 However, possible ocular findings on slit-lamp examination in AD patients include atopic keratoconjunctivitis, blepharitis, palpebral conjunctival scarring, papillary conjunctival reaction, Horner-Trantas dots, keratoconus, and atopic cataracts. Spontaneous retinal detachment is seen more commonly in individuals with AD than in the general population.19

In clinical trials, hypersensitivity reactions included urticaria and serum sickness or serum sickness–like reactions in less than 1% of patients taking dupilumab.18

Conclusion

Childhood AD can be debilitating, and affected individuals often lead a poorer quality of life if left untreated. Embarrassment and isolation are commonly experienced. Increased responsibility and work in tending for a child with eczema may result in parental exhaustion.21 As with psoriasis, AD can impair activity and productivity.22 Currently, dupilumab has proven to positively impact health-related quality of life for adults.23 Pending the outcome of ongoing pediatric clinical trials, dupilumab may become a benchmark therapy for children younger than 18 years.

Case Report

A 7-year-old boy with a history of shellfish anaphylaxis, pollen allergy, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, frequent headaches and ear infections, sinusitis, bronchitis, vitiligo, warts, and cold sores presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a widespread crusting, cracking, red rash that had been present since 6 months of age. The patient’s mother reported that he had many sleepless nights from uncontrolled itching. His medications included albuterol solution for nebulization, loratadine, and montelukast. Prior to the current presentation he had been treated with triamcinolone and betamethasone creams by the pediatrician. Despite compliance with topical therapy, his mother stated the itching persisted and lesions lingered with minimal improvement. He also was treated with oral corticosteroids for episodic sinusitis and bronchitis, which was beneficial to the skin lesions for only a short duration. The patient was adopted and therefore his family history was unavailable.

During physical examination, the patient was in the fetal position on the examination table and appeared uncomfortable, scratching himself. The patient admitted to severe widespread itching and burning. On skin examination, multiple thick, lichenified, highly pruritic plaques coalesced on the knees, ankles, arms, and wrists, and very discreet scaly patches were present on the scalp. Annular patches covered 50% of the patient’s body, with highly inflamed lesions concentrated in skin folds (Figure 1), leading to diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD).

Over the course of several months, a number of topical therapies were prescribed. The calcineurin inhibitor pimecrolimus cream 1% proffered minimal relief, and the patient experienced burning with crisaborole despite attempts to combine it with emollients and topical corticosteroids. The patient and his mother favored intermittent use of topical corticosteroids alone; however, he experienced frequent disease flares. Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray and mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment were included in the treatment regimen as adjunctive topical therapies. Additionally, the patient underwent bleach and vinegar bath therapy without success.

Although UVA and UVB phototherapy has shown to be safe and effective in children, our patient had limited treatment options due to insurance restrictions. The patient had been taking oral corticosteroids on and off for years prior to presentation to our dermatology clinic.

Our patient weighed approximately 40 lb and was prescribed methotrexate 5 mg once weekly for 2 weeks along with oral folic acid 1 mg once daily, except when taking the methotrexate. Laboratory workup was ordered at 2- and then 4-week intervals. After 2 weeks of treatment, methotrexate was increased to 10 mg once weekly. His asthma was carefully monitored by the allergist, and his mother was instructed to stop the medication if he had worsening shortness of breath or exacerbation of asthma symptoms. He tolerated methotrexate at 10 mg once weekly well without clinical side effects for 6 months. His mother observed less frequent ear and sinus infections during methotrexate therapy; however, he developed anemia over time and the methotrexate was discontinued. Understanding the nature of off-label use in administering dupilumab, the patient’s mother consented to a scheduled dosage of 300 mg subcutaneous (SQ) injection every month in the absence of a loading dose with the assumption of future modifications pending his response to therapy.

Five days after treatment with a 300-mg SQ dupilumab injection, the patient returned to clinic for evaluation of a vesicular rash with subsequent peeling confined to the shoulders (Figure 2). He and his mother denied any UV exposure, citing he had been completely out of the sun. He denied constitutional symptoms including fever, malaise, swelling, joint pain, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, enlarged lymph glands, difficulty urinating, breathing, or neurological disturbance. Upon physical examination, the rash was not considered to be a drug eruption. Had a mild drug reaction been suspected, a careful rechallenge, weighing the risks and benefits, would have been considered and was discussed with the mother and patient. New-onset or worsening eye symptoms should be reported; therefore, a referral to ophthalmology was prompted due to our patient’s history of rhinoconjunctivitis and persistent conjunctival injection observed early after initiating dupilumab therapy. Nothing remarkable was found.

The patient was eager to continue dupilumab therapy due to considerable reduction of itching and elimination of lesions. His mother reported that the greatest benefit 1 month after starting dupilumab was almost no itching (Figure 3A). Additionally, he denied headache or nasopharyngitis at his 1-month office visit. After 2 months of dupilumab therapy, the patient reported persistent lesions on the feet and ankles despite concomitant treatment with topical corticosteroids. The decision to increase the dupilumab dose to 300-mg SQ injection once every 3 weeks for a total of 3 doses was made, which resulted in resolution of all lesions (Figure 3B).

Comment

Prevalence and Pathogenesis

Atopic dermatitis affects 31.6 million individuals in the United States, with 17.8 million experiencing moderate to severe lesions.1 The current prevalence of AD in the pediatric population ranges from 10% to 30% compared to 2% to 10% in adults. Fortunately, up to 70% of young children enter remission or improve by 12 years of age. Atopic diatheses may simultaneously occur, which includes asthma and rhinoconjunctivitis.2

Complications from AD include bacterial and viral infections and ocular disease. Furthermore, impaired growth in stature has been correlated with individuals who have extensive disease.2 Of interest, our 7-year-old patient gained 7 lb and grew almost 3 in within 6 months of being on immunosuppressant therapy. Children with AD have poorer sleep efficiency in contrast to children without AD.3 Eczema is associated with more frequent headaches in childhood, especially in those with sleep disturbances,4 as our patient had experienced prior to systemic therapy.

The pathogenesis of AD is complex, and one must take into consideration the multiple cellular activities including inflammatory mechanics in the absence of IgE-mediated sensitization, epidermal barrier changes, epicutaneous sensitization, dendritic cell roles, T-cell responses and cytokine orchestrations, actions of microbial colonization, and involvement of autoimmunity.5 Select patients with AD have IgE antibodies focused against self-proteins. Disease severity correlates with ubiquity of these antibodies. Moreover, certain autoallergens induce helper T cell (TH1) responses.5 Circulating TH2 cytokines and chemokines IL-4, IL4ra, and IL-13 also have been linked to AD pathogenesis. Additionally, nonlesional skin abnormalities have been observed.6 Most recently, researchers have identified a caspase recruitment domain family member 11 (CARD11) gene mutation possibly leading to AD.7 Clinically, our patient responded favorably to dupilumab, which inhibits TH2 cytokines IL-4 and IL13. He experienced a considerable decrease in itching and inflammation and reduced lesion count after 1 month of treatment with dupilumab. No skin lesions were identified on visual examination at week 17 and inevitably the patient discontinued messy topicals.

Treatment Options

Because AD is characterized by episodes of remission and relapse, management generally is comprised of trigger avoidance, including known allergens and irritants; a skin care regimen that promotes healthy epidermal barrier function; anti-inflammatory therapies to control both flares and subclinical inflammation; and adjunctive therapy for additional symptomatic control (eg, phototherapy, stabilized hypochlorous acid, topical antibiotic treatment) when needed. Avoidance of excessive washing or irritants, food provocation, and emotional stress, as well as toleration of body temperature fluctuations and humidity, is recommended to amend exacerbations.5

Current topical therapies include emollients; corticosteroids; calcineurin inhibitors; and crisaborole, a newer phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. There are a number of emollients and moisturizers available, and one over-the-counter preparation showed tolerability and improved skin hydration in AD patients and demonstrated less transepidermal water loss than the control group.8 Ointments such as petrolatum usually do not include ingredients such as preservatives, gelling agents, or humectants that can promote stinging or burning.9 Topical corticosteroids, which ameliorate inflammation by subduing proinflammatory cytokine expression, have been the mainstay of treatment for more than 60 years; however, caution should be used due to the potential for side effects, mainly but not limited to systemic absorption in children, development of striae, and skin atrophy. Calcineurin inhibitors prohibit T-cell activity, modify mast cell response, and decrease dendritic cells in the epidermis. Since 2000, calcineurin inhibitors have been utilized as steroid-sparing agents10; however, prior authorization is still necessary with some insurance providers. Crisaborole ointment 2%, the newest topical agent for AD treatment in the market, has shown improvement of erythema, exudation, and pruritus. Approved for patients aged 2 years and older, twice-daily application of topical crisaborole as a steroid-sparing agent has rendered AD symptom relief.11 It has been reported that 4% of patients encounter stinging or burning with topical crisaborole application, whereas up to 50% of calcineurin inhibitors induce these adverse effects.12 Stabilized hypochlorous acid spray or gel acts as an antipruritic and antimicrobial agent, relieving pain associated with skin irritations. Topical antimicrobial preparations such as mupirocin 2% antibiotic ointment can reduce Staphylococcus colonization when applied in the nasal passage as well as to affected skin lesions.2

In children, UVA and UVB phototherapy has proven safe and effective and can be utilized in AD when suitable.13 When patients inadequately respond to topical therapies and phototherapy, systemic immunomodulatory agents have been recommended as treatment options.A child’s developing immune system indeed may be sensitive to systemic therapies as the innate immune system fully matures in adolescence and his/her adaptive immune system is undergoing vigorous definition.14 Systemic immunomodulatory agents such as cyclosporine, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and methotrexate have been used off label for years and pose certain challenges in being identified as durable therapies due to potential side effects. Cyclosporine is effective for the treatment of AD; however, long-term administration should be dosed up to a 12-month period and then stopped to decrease cumulative exposure to the drug. Therefore, further treatment options must be considered. For children, cyclosporine should be administered in a dose of 3 to 6 mg/kg daily. Fluctuations in blood pressure and renal function should be monitored. The recommended pediatric dose for azathioprine is 1 to 4 mg/kg daily with laboratory monitoring, particularly of liver enzymes and complete blood cell count. Obtaining the patient’s thiopurine methyltransferase level may aid in dosing. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea are common. Phototherapy is not advised in conjunction with azathioprine due to an increased risk of photocarcinogenicity.13 The literature supporting mycophenolate mofetil in children with AD is limited.

Biologic therapies targeting IgE, B-lymphocyte antigen CD20, IL-5, thymic stromal lymphopoietin, TH17 cells, IL-12, IL-23, interferon gamma, IL-6 receptors, tumor necrosis factor, phosphodiesterase 4, Janus kinase, chymase, and nuclear receptors expressed on adipocytes and immune cells have undergone investigation for treatment of AD.17 Additionally, biologic agents targeting IL-31, IL-13, and IL-22 also have been evaluated.1 Currently, there are no US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic agents for moderate to severe childhood AD.

Dupilumab, an IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα antagonist, recently has been approved for treatment of moderate to severe AD in adults but not yet for children. Potential side effects include nasopharyngitis, headache, hypersensitivity reactions, and ocular symptoms,11 namely keratitis and conjunctivitis.18 Less than 1% of patients experienced keratitis in clinical trials, while conjunctivitis was reported in 4% of patients taking dupilumab with topical corticosteroids at 52 weeks.18 However, possible ocular findings on slit-lamp examination in AD patients include atopic keratoconjunctivitis, blepharitis, palpebral conjunctival scarring, papillary conjunctival reaction, Horner-Trantas dots, keratoconus, and atopic cataracts. Spontaneous retinal detachment is seen more commonly in individuals with AD than in the general population.19

In clinical trials, hypersensitivity reactions included urticaria and serum sickness or serum sickness–like reactions in less than 1% of patients taking dupilumab.18

Conclusion

Childhood AD can be debilitating, and affected individuals often lead a poorer quality of life if left untreated. Embarrassment and isolation are commonly experienced. Increased responsibility and work in tending for a child with eczema may result in parental exhaustion.21 As with psoriasis, AD can impair activity and productivity.22 Currently, dupilumab has proven to positively impact health-related quality of life for adults.23 Pending the outcome of ongoing pediatric clinical trials, dupilumab may become a benchmark therapy for children younger than 18 years.

- Samalonis L. What’s new in eczema and atopic dermatitis research. The Dermatologist. November 19, 2015. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/whats-new-eczema-and-atopic-dermatitis-research. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Habif T. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bonnet C, Pinczewski A, Cook L, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:160-180.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case control study [published online October 28, 2017]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Silverberg J. Association between childhood eczema and headaches: an analysis of 19 US population-based studies [published online August 29, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:492-499.e5.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:203-216.

- Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle S, Shemer A, et al. Non-lesional atopic dermatitis (AD) skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:954-964.

- Hilton L. AD gene mutation identified: discovery may lead to new therapeutic option for patients. Dermatol Times. 2017;38:30.

- Zeichner JA, Dryer L. Effect of CeraVe Healing Ointment on skin hydration and barrier function on normal and barrier-impaired skin. Poster presented at: Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic & Clinical Conference; January 15-16, 2016; Orlando, FL.

- Garg T, Rath G, Goyal AK. Comprehensive review on additives of topical dosage forms for drug delivery. Drug Delivery. 2015;22:969-987.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Koutnik-Fotopoulous E. Update on the latest eczema treatments. The Dermatologist. February 17, 2016. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/update-latest-eczema-treatments. Accessed August 16, 2018.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Sidbury R, Davis D, Cohen D, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents . J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- van der Merwe R, Gianella-Borradori A. Industry perspective on the clinical development of systemic products for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients with inadequate response to topical prescription therapy. Presented at: FDA Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting; March 9, 2015; Silver Spring, MD.

- Heller M, Shin HT, Orlow SJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: experience in 14 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:127-132.

- Callen JP, Kulp-Shorten CL. Methotrexate. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2013:169-181.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Dhingra N, Leung DY. New era of biological therapeutics in atopic dermatitis [published online January 16, 2013]. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:549-561.

- Dupixent [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Lowery RS. Ophthalmologic manifestations of atopic dermatitis clinical presentation. Medscape website. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1197636-clinical#b4. Updated September 7, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Lenz HJ. Management and preparedness for infusion and hypersensitivity reactions. Oncologist. 2007;12:601-609.

- Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984-992.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the Unites States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2017;77:274-279.

- Tsianakas A, Luger TA, Radin A. Dupilumab treatment improves quality of life in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial [published online January 11, 2018]. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:406-414.

- Samalonis L. What’s new in eczema and atopic dermatitis research. The Dermatologist. November 19, 2015. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/whats-new-eczema-and-atopic-dermatitis-research. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Habif T. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bonnet C, Pinczewski A, Cook L, eds. Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby Elsevier; 2010:160-180.

- Fishbein AB, Mueller K, Kruse L, et al. Sleep disturbance in children with moderate/severe atopic dermatitis: a case control study [published online October 28, 2017]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:336-341.

- Silverberg J. Association between childhood eczema and headaches: an analysis of 19 US population-based studies [published online August 29, 2015]. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:492-499.e5.

- Bieber T, Bussmann C. Atopic dermatitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:203-216.

- Suarez-Farinas M, Tintle S, Shemer A, et al. Non-lesional atopic dermatitis (AD) skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:954-964.

- Hilton L. AD gene mutation identified: discovery may lead to new therapeutic option for patients. Dermatol Times. 2017;38:30.

- Zeichner JA, Dryer L. Effect of CeraVe Healing Ointment on skin hydration and barrier function on normal and barrier-impaired skin. Poster presented at: Orlando Dermatology Aesthetic & Clinical Conference; January 15-16, 2016; Orlando, FL.

- Garg T, Rath G, Goyal AK. Comprehensive review on additives of topical dosage forms for drug delivery. Drug Delivery. 2015;22:969-987.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Koutnik-Fotopoulous E. Update on the latest eczema treatments. The Dermatologist. February 17, 2016. http://www.the-dermatologist.com/content/update-latest-eczema-treatments. Accessed August 16, 2018.

- Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for the topical treatment of AD in children and adults [published online July 11, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:494-503.

- Sidbury R, Davis D, Cohen D, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents . J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-349.

- van der Merwe R, Gianella-Borradori A. Industry perspective on the clinical development of systemic products for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients with inadequate response to topical prescription therapy. Presented at: FDA Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting; March 9, 2015; Silver Spring, MD.

- Heller M, Shin HT, Orlow SJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil for severe childhood atopic dermatitis: experience in 14 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:127-132.

- Callen JP, Kulp-Shorten CL. Methotrexate. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Saunders Elsevier; 2013:169-181.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Dhingra N, Leung DY. New era of biological therapeutics in atopic dermatitis [published online January 16, 2013]. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2013;13:549-561.

- Dupixent [package insert]. Tarrytown, NY: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2017.

- Lowery RS. Ophthalmologic manifestations of atopic dermatitis clinical presentation. Medscape website. emedicine.medscape.com/article/1197636-clinical#b4. Updated September 7, 2016. Accessed July 19, 2018.

- Lenz HJ. Management and preparedness for infusion and hypersensitivity reactions. Oncologist. 2007;12:601-609.

- Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984-992.

- Eckert L, Gupta S, Amand C, et al. Impact of atopic dermatitis on health-related quality of life and productivity in adults in the Unites States: an analysis using the National Health and Wellness Survey. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2017;77:274-279.

- Tsianakas A, Luger TA, Radin A. Dupilumab treatment improves quality of life in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial [published online January 11, 2018]. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:406-414.

Practice Points

- Childhood atopic dermatitis can be debilitating, and affected individuals often experience poorer quality of life if left untreated.

- Dupilumab may become a benchmark therapy for children younger than 18 years.

Concurrent Notalgia Paresthetica and Brachioradial Pruritus Associated With Cervical Degenerative Disc Disease

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented with persistent episodes of severe pruritus with exacerbations on the bilateral forearms, arms, and left side of the mid back of 4 years’ duration. He had a refractory and debilitating disease that had failed extensive therapies including topical antipruritics, antihistamines, oral hydroxyzine, capsaicin, potent topical steroids (ie, clobetasol, fluocinonide, triamcinolone), phototherapy with narrowband UVB, and various dietary modifications including a gluten-free trial. The patient reported he had exhausted all medical evaluation through care with more than 7 physicians and multiple dermatologists, including a university-based dermatology department for repeated consultations; he was seen by our dermatology center for an eighth opinion.

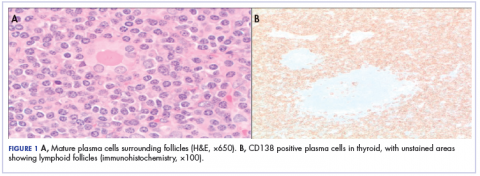

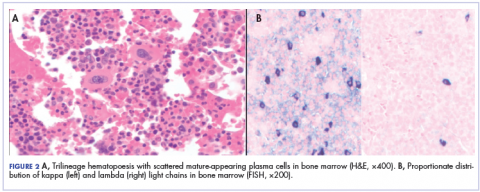

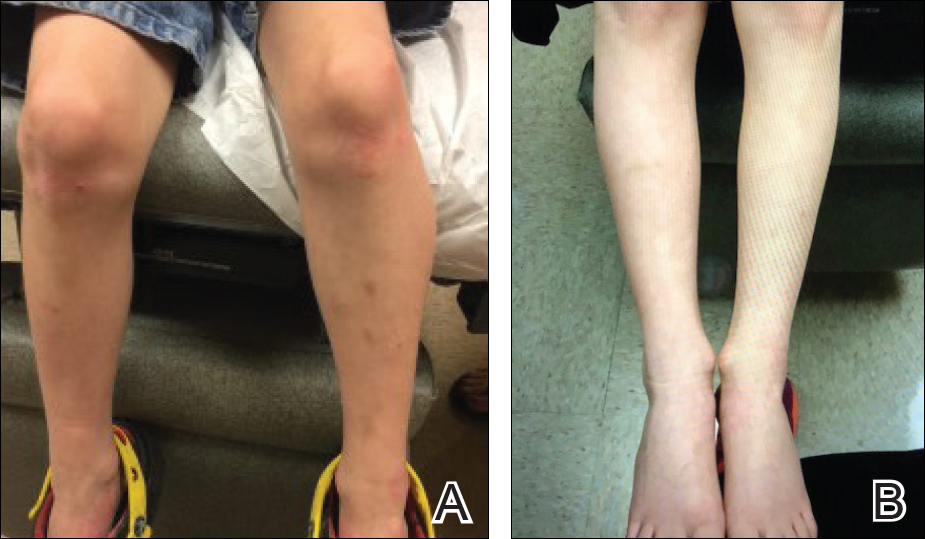

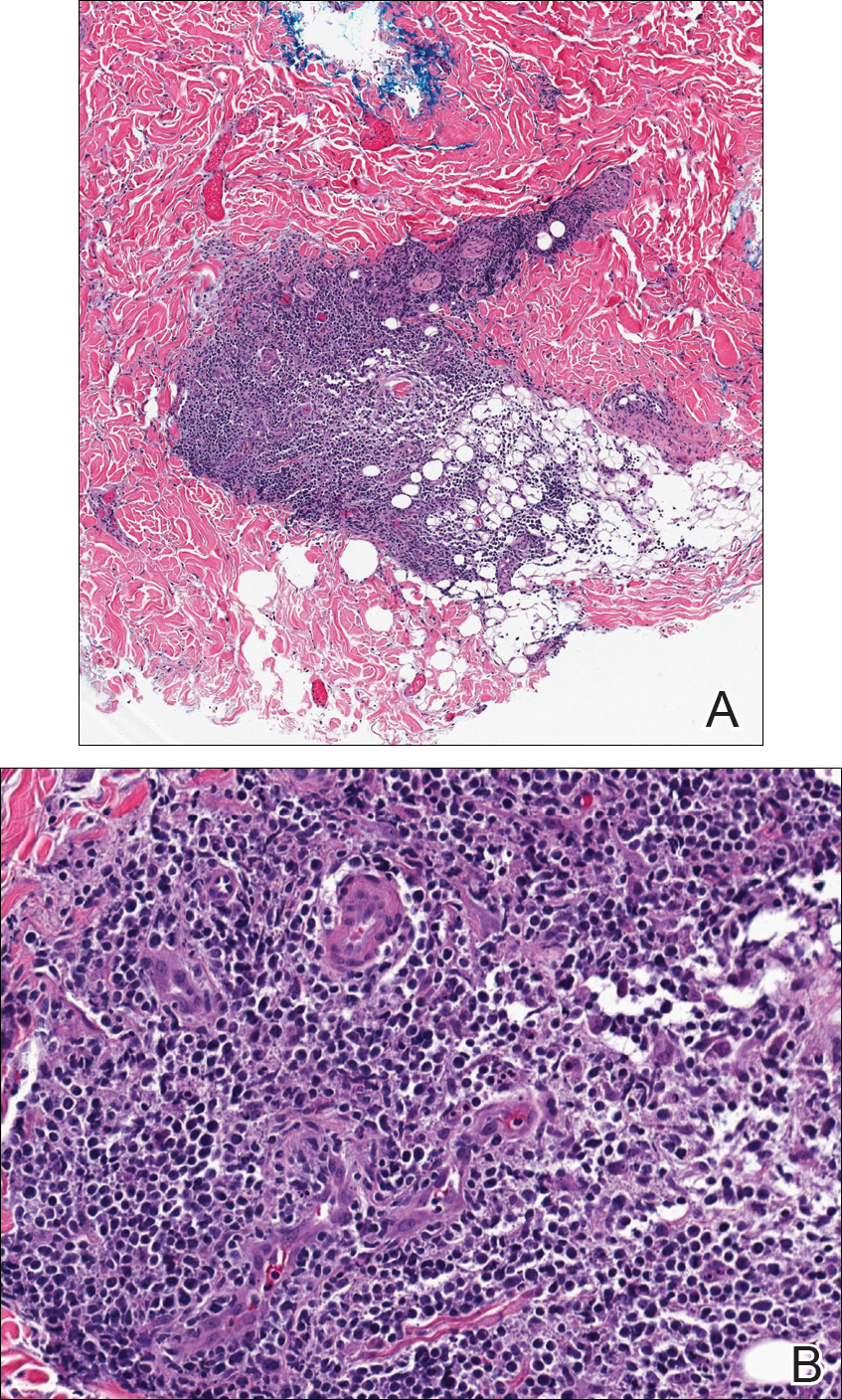

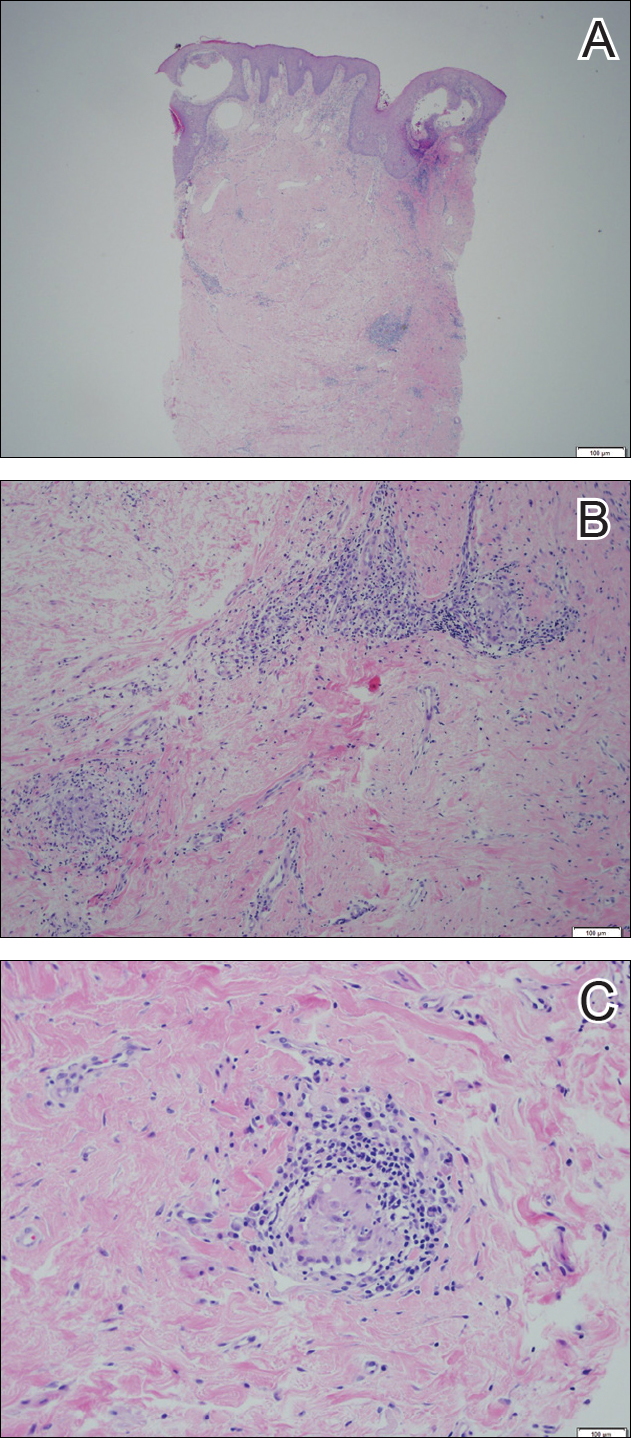

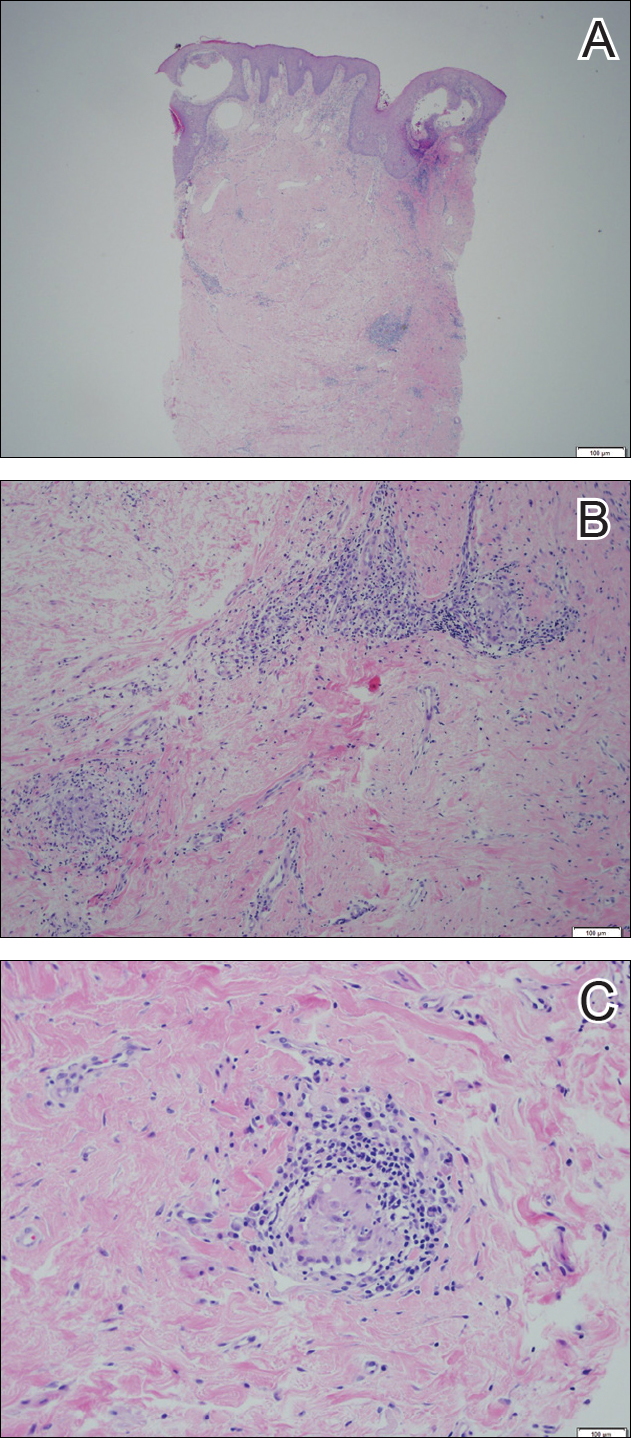

Initial dermatologic examination revealed multiple secondarily excoriated, hemorrhagic, hyperpigmented plaques and nodules on the right side of the mid upper back indicative of notalgia paresthetica (NP) with secondary chronic skin changes (Figure 1). Additional examination of the left arm and forearm revealed several open erosions, raised nodules, and lichenified skin plaques indicative of brachioradial pruritus (BP) with secondary skin changes (Figure 2). In addition, multiple lichenified plaques of the left side of the mid back were associated with decreased sensory alternations to light touch and pin prick. Of note, the localized pruritus pattern, particularly of the unilateral infrascapular back region, heralded the possibility of a neuropathic pruritus condition originating from the cervical spine. Examination confirmed decreased range of motion in the neck with associated marked palpable bilateral cervical muscle spasm and tenderness. Laboratory testing confirmed Staphylococcus aureus secondary skin infection that was treated empirically with chlorhexidine wash. General pruritus serology and imaging workup was ordered with contributory results. The patient’s medical history was notable for noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, obesity, deep venous thrombosis, asthma, vein surgery, cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, atopy, allergies, asthma, and keratosis pilaris, as well as drug intolerances of warfarin sodium, sitagliptin, and clopidogrel. His medications on presentation included glyburide, digoxin, prednisone, aspirin, cetirizine, cimetidine, and hydroxyzine. Based on the relatively classic localized pruritus symptoms and the anatomical distribution of skin findings, a clinical diagnosis of concurrent NP and BRP was made, and radiologic studies of the cervical spine were ordered.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine showed severe central canal stenosis at C3-C4 secondary to disc disease slight asymmetric toward the right side, severe central canal stenosis at C4-C5 slightly more prominent in the midline, severe central stenosis at C5-C6 more prominent in the midline, and mild changes at other levels as described. Laboratory workup revealed an abnormal complete blood cell count with mildly elevated white blood cell count (11,800/µL [reference range, 4000–10,500/µL]), elevated neutrophils (8600/µL [reference range, 1800–7800/µL]), elevated eosinophils (600/µL [reference range, 0–450/µL ]), and elevated IgE (160 IU/mL [reference range, 0–100 IU/mL]). Further testing revealed negative results for Helicobacter pylori IgG and IgM, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis B and C screening panels; antinuclear antibody negative; normal thyroid-stimulating hormone; and normal thyroid peroxidase antibody. Chest radiograph and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative.

We referred the patient for a neurosurgical consultation that uncovered newly diagnosed severe cervical stenosis with mild to moderate canal compromise at C3, C4, C5, and C6. His motor examination revealed full strength in the upper extremities (5/5). Sensory examination showed patchy sensory alteration on the mid back. He declined oral antibiotics as advised for the skin staphylococcal infection and neurosurgical treatment for the cervical disease.

During the 4 years prior to presentation at our center, the patient reported failure to improve with a dermatologically prescribed gluten-free diet as well as all topical and oral steroid treatments. He was presented at a university grand rounds where a suggestion for UVB light treatment was made; the patient reported possible worsening of symptoms with narrowband UVB phototherapy.

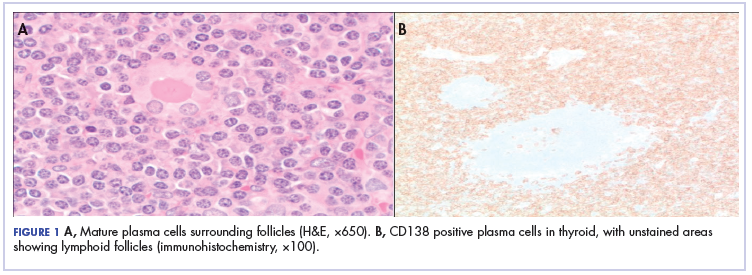

At the patient’s first visit at our center, for immediate symptom relief he underwent therapy with transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation (TENS) with acupuncture of the cervicothoracic spine (Figure 3). He agreed to discontinue oral prednisone and begin chlorhexidine cleansing body wash, low-dose hydroxyzine 10-mg tablets up to 60 mg every 6 hours as required for pruritus, and mupirocin intranasal ointment. At 1-week follow-up, he reported at least 50% improvement in his symptoms with decreased pruritus, improved sleep, and enhanced quality of life. Within 2 weeks of initial assessment, there was a notable 70% clinical improvement of both the NP and BRP, with a notable decrease in cutaneous erosions and flattening of the pruritic skin nodules. He reported adequate control of symptoms with continued TENS for at-home use 3 times daily for 5- to 10-minute intervals.

Comment

NP Presentation

Notalgia paresthetica is a common, albeit heavily unrecognized and underdiagnosed, sensory neuropathic syndrome of the back, classically of the unilateral infrascapular region. Notalg

The dermatologic condition may consist of other symptoms that include but are not limited to localized burning, pain, tenderness, hyperalgesia, or dysesthesia. Notalgia paresthetica typically is associated with a poorly confined tan or hyperpigmented patch in the symptomatic area, though the skin may have no visible findings in many early cases. Notalgia paresthetica tends to be a chronic condition with periodic remissions and exacerbations. It is generally not associated with other comorbidities and is not life threatening; however, it does frequently decrease quality of life, causing much discomfort and annoyance to the affected patients.

Treatment

Topical therapies for NP have generally failed and are considered difficult because of the out-of-reach affected location. There is no uniformly effective treatment of NP.

Pathogenesis

The etiologies for NP and BRP are evolving and remain to be fully elucidated. Although the exact etiology remains uncertain, there are several possible mechanisms that have been proposed for NP: (1) neuropathy from degenerative cervicothoracic disc disease or direct nerve impingement,1 and (2) localized increased sensory innervations of the affected skin areas.2

Differential and Workup

The differential diagnosis in NP may include allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, dermatophytosis, neoplasm, lichen amyloidosis, arthropod reaction, lichenified skin reactions including lichen simplex chronicus, neurodermatitis, infection, and other hypersensitivity reaction.

It is important during the initial assessment of patients with NP and/or BRP to obtain a thorough history of osteoarthritis, neck trauma, motor vehicle accident(s), vertebral fracture, cervical neoplasm or malignancy, family history of NP or BRP, or cervical disc disease. Radiographs or MRIs of the cervical spine may aid in diagnosis and treatment, and perhaps more so if there is an absence of contributory medical history. Radiographic imaging also may be indicated if there is a positive family history of osteoarthritis or vertebral disc disease.

A full laboratory workup including complete blood cell count, chemistry panel including renal and liver functions, and other laboratory tests (eg, IgE levels) may be warranted if pruritus is generalized and persistent to exclude other causes. Proper management of NP and BRP may involve a multispecialty effort of dermatology with radiology; orthopedic surgery; neurosurgery; neurology; and adjunctive fields including acupuncture, massage, chiropractic, and physical therapy.

NP and BRB Overlap

Because NP and BRP often originate from varying degrees of cervical disease, particularly at the C5-C6 level, traditional topical therapies aimed at treating the affected skin of the mid back and forearms may be ineffectual or partially effective as basic emollients. Due to NP and BRP’s periodic spontaneous remissions and exacerbations, it may be reasonably difficult to accurately measure direct response to various therapies. Some topical therapies aimed at the mid back skin or forearms may appear partially effective from a placebo-type perspective.

Currently, uniformly effective treatment of NP and BRP include the following: (1) therapies aimed at the cervical spine at C5-C6, including TENS, cervical massage, physical therapy, and acupuncture; and (2) therapies targeting the underlying lowered pruritus threshold such as oral antihistamines and narrowband UVB. Although uniformly effective treatments in this space had been previously lacking, traditional therapeutic options for NP and BRP included capsaicin cream, eutectic mixture of local anesthetic cream, topical steroids, pramoxine cream, topical cooling, oral steroids, menthol creams, various commercially available topical mixtures of menthol and methyl salicylate, cordran tape, intralesional corticosteroid injections, botulinum toxin injections,3 oral antihistamines, hydroxyzine, doxepin, topiramate, carbamazepine, antidepressants, gabapentin, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, thalidomide,4 paravertebral local anesthetic block, cervical epidural injection, surgical resection of the rib, and many others. Some of the tried systemic therapies exert their effect through the spinal nerves and central nervous system, thereby supporting the neuropathic etiology of NP.

Cervical Disc Disease

Alai et al1 reported a 37-year-old with documented NP on the right side of the back with MRI findings of disc disease at C5-C6 and mild nerve impingement that strongly suggest the association of cervical degenerative disc disease and NP.

Savk and Savk5 reported that 7 of 10 patients with NP demonstrated normal neurological examination and standard electrodiagnostic results. All had skin histopathology compatible with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. There were no amyloid deposits or other described pathology on pathologic examination of the skin. Seven of 10 cases confirmed radiographic changes in the vertebra corresponding to the dermatome of the cutaneous lesion.5

An earlier study by Springall et al6 evaluating the mechanism of NP studied whether the cutaneous symptoms were caused by alternations on the cutaneous innervation of the involved infrascapular area. They p

Histologic studies have shown cutaneous changes in a few cases including lichen amyloidosis that may be secondary to the localized chronic scratching and rubbing.7 Clinical observations in orthopedics have established a clear relationship between the upper thoracic and interscapular region and the lower cervical spine. Frequently, cervical disc disease presents as referred pain in the upper thoracic and interscapular area. Similarly, some tumors of the cervical medulla also have presented as interscapular pain.8

Some have speculated direct involvement and actual entrapment of the posterior rami of T2-T6 spinal nerves.9 However, there are referred symptoms from the cervical area directly to the interscapular back. Degenerative vertebral and disc changes corresponding to the affected dermatome may be observed in some cases. Radiographic imaging of cervical and thoracic spine will help to exclude disc disease and possible nerve compromise.8

With advances in radiography and availability of MRI, earlier detection and intervention of cervical disc disease is possible. Early recognition may promote timely intervention and treatment to prevent cervical spine disease progression. In addition to degenerative cervical discs, osteoarthritis, and cervical spine strain and muscle spasm, there may be neoplasms or other pathology of the cervical spine contributing to NP and BRP.

There is some thought that there may be a relationship between NP and BRP. The described association of many cases of BRP and cervical spine disease6 and description of these diseases as likely neuropathic/neurogenic pruritic conditions also support a probable association of these two conditions. In contrast, NP has classically been described as unilateral in distribution, while BRP may involve unilateral or bilateral dorsolateral forearms. Most recently, as seen in our case, there are increasing incidences of nonclassic presentations of both of these diseases that may involve additional skin areas and be a basis for diagnostic challenges to the clinician.

First-line therapies for NP and BRP with associated cervical spinal disease are currently evolving and may include nondermatologic and noninvasive treatments such as spinal manipulation, physical therapy, acupuncture, cervical soft collars, massage, cervical traction, cervical muscle strengthening and increased range on motion, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (eg, ibuprofen, celecoxib, ketorolac), and oral muscle relaxants (eg, carisoprodol, cyclobenzaprine, methocarbamol, metaxalone). Curren

Conclusion

Notalgia paresthetica and BRP may not be solely skin diseases but rather cutaneous signs of an underlying cervical spine disease. The striking association of NP with BRP we present as well as the degenerative and/or traumatic cervicothoracic spine disease suggests that early spinal nerve impingement or cervical muscle spasm may contribute to the pathogenesis of these skin symptoms. Additional studies are needed to further assess the relationship of NP and BRP as well as the association of each disease entity independently with cervical spine disease, as it is unknown if these are causal or coincidental findings. Although topical therapies may seemingly help decrease the localized symptoms in NP and BRP in some cases, systemic or broader-scope cervical spinal evaluation may be warranted to fully evaluate refractory cases. Cervical spinal imaging and treatment, particularly at C5-C6 levels, may be appropriate as primary or first-line therapy in many cases of NP and BRP. The paradigm shift in thinking will more likely than not be to treat the cervical spine and the skin will follow.

- Alai NN, Skinner HB, Nabili S, et al. Notalgia paresthetica associated with cervical spinal stenosis and cervicothoracic disk disease at C4 through C7. Cutis. 2010;85:77-81.

- Savk E, Savk O, Bolukbasi O, et al. Notalgia paresthetica: a study on pathogenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:754-759.

- Tait CP, Grigg E, Quirk CJ. Brachioradial pruritus and cervical spine manipulation. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:168-170.

- Goodless DR, Eaglstein WH. Brachioradial pruritus treatment with topical capsaicin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29(5, pt 1):783-784.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:1085-1087.

- Springall DR, Karanth SS, Kirkham N, et al. Symptoms of notalgia paresthetica may be explained by increased dermal innervation. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:555-561.

- Weinfeld PK. Successful treatment of notalgia paresthetica with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:980-982.

- Misery L. What is notalgia paresthetica? Dermatology. 2002;204:86-87.

- Pleet AB, Massey EW. Notalgia paresthetica. Neurology. 1978;28:1310-1312.

- Findlay C, Ayis S, Demetriades AK. Total disc replacement versus anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Bone Joint J. 2018;100-B:991-1001.

Case Report

A 74-year-old man presented with persistent episodes of severe pruritus with exacerbations on the bilateral forearms, arms, and left side of the mid back of 4 years’ duration. He had a refractory and debilitating disease that had failed extensive therapies including topical antipruritics, antihistamines, oral hydroxyzine, capsaicin, potent topical steroids (ie, clobetasol, fluocinonide, triamcinolone), phototherapy with narrowband UVB, and various dietary modifications including a gluten-free trial. The patient reported he had exhausted all medical evaluation through care with more than 7 physicians and multiple dermatologists, including a university-based dermatology department for repeated consultations; he was seen by our dermatology center for an eighth opinion.

Initial dermatologic examination revealed multiple secondarily excoriated, hemorrhagic, hyperpigmented plaques and nodules on the right side of the mid upper back indicative of notalgia paresthetica (NP) with secondary chronic skin changes (Figure 1). Additional examination of the left arm and forearm revealed several open erosions, raised nodules, and lichenified skin plaques indicative of brachioradial pruritus (BP) with secondary skin changes (Figure 2). In addition, multiple lichenified plaques of the left side of the mid back were associated with decreased sensory alternations to light touch and pin prick. Of note, the localized pruritus pattern, particularly of the unilateral infrascapular back region, heralded the possibility of a neuropathic pruritus condition originating from the cervical spine. Examination confirmed decreased range of motion in the neck with associated marked palpable bilateral cervical muscle spasm and tenderness. Laboratory testing confirmed Staphylococcus aureus secondary skin infection that was treated empirically with chlorhexidine wash. General pruritus serology and imaging workup was ordered with contributory results. The patient’s medical history was notable for noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, obesity, deep venous thrombosis, asthma, vein surgery, cardiovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, atopy, allergies, asthma, and keratosis pilaris, as well as drug intolerances of warfarin sodium, sitagliptin, and clopidogrel. His medications on presentation included glyburide, digoxin, prednisone, aspirin, cetirizine, cimetidine, and hydroxyzine. Based on the relatively classic localized pruritus symptoms and the anatomical distribution of skin findings, a clinical diagnosis of concurrent NP and BRP was made, and radiologic studies of the cervical spine were ordered.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine showed severe central canal stenosis at C3-C4 secondary to disc disease slight asymmetric toward the right side, severe central canal stenosis at C4-C5 slightly more prominent in the midline, severe central stenosis at C5-C6 more prominent in the midline, and mild changes at other levels as described. Laboratory workup revealed an abnormal complete blood cell count with mildly elevated white blood cell count (11,800/µL [reference range, 4000–10,500/µL]), elevated neutrophils (8600/µL [reference range, 1800–7800/µL]), elevated eosinophils (600/µL [reference range, 0–450/µL ]), and elevated IgE (160 IU/mL [reference range, 0–100 IU/mL]). Further testing revealed negative results for Helicobacter pylori IgG and IgM, human immunodeficiency virus, and hepatitis B and C screening panels; antinuclear antibody negative; normal thyroid-stimulating hormone; and normal thyroid peroxidase antibody. Chest radiograph and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were negative.

We referred the patient for a neurosurgical consultation that uncovered newly diagnosed severe cervical stenosis with mild to moderate canal compromise at C3, C4, C5, and C6. His motor examination revealed full strength in the upper extremities (5/5). Sensory examination showed patchy sensory alteration on the mid back. He declined oral antibiotics as advised for the skin staphylococcal infection and neurosurgical treatment for the cervical disease.

During the 4 years prior to presentation at our center, the patient reported failure to improve with a dermatologically prescribed gluten-free diet as well as all topical and oral steroid treatments. He was presented at a university grand rounds where a suggestion for UVB light treatment was made; the patient reported possible worsening of symptoms with narrowband UVB phototherapy.

At the patient’s first visit at our center, for immediate symptom relief he underwent therapy with transcutaneous electronic nerve stimulation (TENS) with acupuncture of the cervicothoracic spine (Figure 3). He agreed to discontinue oral prednisone and begin chlorhexidine cleansing body wash, low-dose hydroxyzine 10-mg tablets up to 60 mg every 6 hours as required for pruritus, and mupirocin intranasal ointment. At 1-week follow-up, he reported at least 50% improvement in his symptoms with decreased pruritus, improved sleep, and enhanced quality of life. Within 2 weeks of initial assessment, there was a notable 70% clinical improvement of both the NP and BRP, with a notable decrease in cutaneous erosions and flattening of the pruritic skin nodules. He reported adequate control of symptoms with continued TENS for at-home use 3 times daily for 5- to 10-minute intervals.

Comment

NP Presentation

Notalgia paresthetica is a common, albeit heavily unrecognized and underdiagnosed, sensory neuropathic syndrome of the back, classically of the unilateral infrascapular region. Notalg

The dermatologic condition may consist of other symptoms that include but are not limited to localized burning, pain, tenderness, hyperalgesia, or dysesthesia. Notalgia paresthetica typically is associated with a poorly confined tan or hyperpigmented patch in the symptomatic area, though the skin may have no visible findings in many early cases. Notalgia paresthetica tends to be a chronic condition with periodic remissions and exacerbations. It is generally not associated with other comorbidities and is not life threatening; however, it does frequently decrease quality of life, causing much discomfort and annoyance to the affected patients.

Treatment

Topical therapies for NP have generally failed and are considered difficult because of the out-of-reach affected location. There is no uniformly effective treatment of NP.

Pathogenesis

The etiologies for NP and BRP are evolving and remain to be fully elucidated. Although the exact etiology remains uncertain, there are several possible mechanisms that have been proposed for NP: (1) neuropathy from degenerative cervicothoracic disc disease or direct nerve impingement,1 and (2) localized increased sensory innervations of the affected skin areas.2

Differential and Workup

The differential diagnosis in NP may include allergic or irritant contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, dermatophytosis, neoplasm, lichen amyloidosis, arthropod reaction, lichenified skin reactions including lichen simplex chronicus, neurodermatitis, infection, and other hypersensitivity reaction.

It is important during the initial assessment of patients with NP and/or BRP to obtain a thorough history of osteoarthritis, neck trauma, motor vehicle accident(s), vertebral fracture, cervical neoplasm or malignancy, family history of NP or BRP, or cervical disc disease. Radiographs or MRIs of the cervical spine may aid in diagnosis and treatment, and perhaps more so if there is an absence of contributory medical history. Radiographic imaging also may be indicated if there is a positive family history of osteoarthritis or vertebral disc disease.