User login

Acute Aortic Occlusion With Spinal Cord Infarction

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

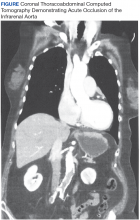

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

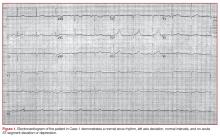

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

Acute aortic occlusion (AAO) is a relatively rare vascular emergency. The actual incidence of AAO is unknown but has been variously reported to be 1% to 4%, and the incidence of AAO secondary to infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm is reported to be about 2%.1 Acute aortic occlusion may present with acute onset of neurologic deficits as a consequence of spinal cord ischemia from thrombotic or embolic etiology. Risk factors for thrombosis include hypertension, tobacco smoking, and diabetes mellitus; heart disease and female gender are associated with embolism.2 Spinal cord infarction accounts for only 1% to 2% of all strokes and is characterized by acute onset of paralysis, bowel and bladder dysfunction, and loss of pain and temperature perception. Proprioception and vibratory sense are typically preserved.3 The authors present the case of a patient with acute onset of lower limb paralysis and urinary incontinence who was later found to have AAO due to thrombosis and consequent spinal cord infarction.

Case Presentation

An 80-year-old white woman presented to the emergency department of Jefferson Regional Medical Center in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, with the sudden onset of severe lower back pain, bilateral leg paralysis and paresthesia, and urinary incontinence. The patient stated that she had been watching television when her legs began to tingle and feel numb. Within 10 to 20 minutes she was unable to move her legs and became incontinent of urine. She reported no injury or previous history of back pain. Her medical history was significant for “irregular heartbeat my whole life,” hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and bladder cancer. She was not receiving systemic anticoagulation therapy. She reported a previous 15 pack-year smoking history but reported that she had quit cigarette smoking and usually drank 1 glass of wine daily. She had previously completed 3 rounds of chemotherapy for bladder cancer and received her first radiation treatment earlier that day. The symptoms began about 8 hours later that evening.

On examination the patient was noted to be in acute distress due to pain. Her vital signs in triage were blood pressure (BP) 122/71 mm Hg, pulse 54 beats per min (BPM), respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 90% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. Laboratory evaluation was remarkable only for serum sodium 132 mEq/L, potassium 2.8 mEq/L, and thrombocytosis with platelets 697 × 103/μL. A neurologic examination showed normal motor function, strength of the upper extremities, and paralysis of the lower extremities, which were insensate to blunt or sharp touch and with decreased skin temperature from the groin distally. Pedal pulses were absent bilaterally. She was incontinent of urine and had anal sphincter laxity.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed bulging lumbar intervertebral discs and foraminal narrowing, which the consulting neurosurgeon did not feel explained her presentation and suggested that a vascular etiology was more likely. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta, bilateral common, and external iliac arteries. The proximal inferior mesenteric artery was occluded, and there was 90% stenosis of the proximal superior mesenteric artery with noncalcified plaque. There was no abdominal aortic aneurysm or dissection demonstrated. A chest CT was unremarkable.

The patient was started on IV heparin 800 U/h and transferred via ambulance to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas, for vascular surgery. On arrival her vital signs were BP 108/69 mm Hg, pulse 123 BPM, respirations 18 breathes per min, temperature 98° F, and pulse oximetry 94% on 2 L/min oxygen via nasal cannula. The patient’s electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with premature ventricular complexes. On examination the bilateral lower extremities were cyanotic and cold to the touch. The pedal pulses were nonpalpable, and decreased distal sensation with dense paralysis was noted.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room (OR) for left axillary bifemoral bypass. Severe atherosclerotic disease was noted at surgery. She was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) for postoperative hemodynamic monitoring. Her clinical course became complicated by mesenteric ischemia from chronic superior mesenteric artery (SMA) occlusion. On postoperative day 2, she became progressively more hypotensive, and she was placed on vasopressin 0.04 U/min and amiodarone 0.5 mg/min infusions.

Bedside echocardiography showed diffuse ventricular hypokinesis and a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of about 30% but no mural thrombus. The patient developed altered mental status and respiratory distress, and her serum lactate increased to 6.1 mg/dL. She was emergently intubated and taken to the OR to attempt recanalization of the SMA occlusion, which was unsuccessful. She was returned to the SICU for continued resuscitation and monitoring. She continued to decline with hypotensive pressures, increasing serum creatinine and lactate, and worsening metabolic acidosis. Management options and goals of care were discussed with the family, and it was decided to honor her do not resuscitate status and pursue comfort care. She was extubated and expired a short time after this was done.

Discussion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency with a mortality rate that approaches 75%.4-6 It results from numerous etiologies, including saddle embolism at the aortic bifurcation, acute thrombus formation, subsequent to aortic dissection, or other causes related to severe atherosclerotic disease or hypercoagulable states.4,7

A recent retrospective series of 29 cases of AAO found that thrombosis was the cause for 76% of cases, and > 40% of patients had a hypercoagulable state either because of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (17%) or malignancy (24%).6 The most common presentation of AAO is the abrupt onset of painful bilateral paresis or paraplegia.5,6 While some studies have suggested that the major determinant of mortality is time elapsed until revascularization,7 other studies have reported that the neurologic status of the extremities is more closely related with mortality.2

The anterior spinal artery is the major independent provider of blood flow to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord, including the anterior horns, the anterior commissure, the anterior funiculi, and to a variable extent, the lateral funiculi. The largest segmental posterior radicular branch of the anterior spinal artery is the artery of Adamkiewicz, which arises from the T9 to T12 level on the left in 75% of cases and provides perfusion to the lumbar spinal cord and the conus medullaris. Obstruction of blood flow in this region has been implicated in the clinical picture of anterior cord syndrome characterized by abrupt onset of radicular pain, flaccid paresis or paralysis, sphincter dysfunction with urinary and fecal incontinence, and decreased pain and temperature sensation below a sensory level with spared proprioception and vibratory sensation.3, 8-10

Aortography is the gold standard procedure for diagnosis of AAO, but it is a time-consuming procedure, and preoperative testing is controversial. Contrast-enhanced CT is useful for evaluation as it can be quickly accomplished and is more available in general hospitals. Moreover, CT scanning may reveal aortic dissections or aneurysms as the cause of occlusion. Deep Doppler ultrasonography also has demonstrated utility as a noninvasive and rapidly performed diagnostic procedure. Magnetic resonance angiography or CT should be performed for all cases unless the patient’s clinical condition prevents this evaluation. Imaging not only confirms diagnosis, but also is valuable for assessment and planning management.11-14

Once the diagnosis of AAO is made, management with IV fluid hydration, heparin administration, and optimizing cardiac function are essential. However, conservative management with anticoagulation alone is associated with high mortality, and unless the ischemia is irreversible or unless the patient is in a dying state, surgery is appropriate.5,7 Depending on the etiology of the AAO, anatomic considerations, and other patient factors, urgent revascularization with thrombo-embolectomy, direct aortic reconstruction, or anatomic or extra-anatomic bypass procedures may be employed. Aortic reconstruction has been advocated for all patients with infrarenal aortic occlusion given the concern for propagation of thrombosis at the distal aorta proximally to the renal and mesenteric arteries.7 Axillary-bifemoral bypass has been advocated as a rapid revascularization strategy with good patency and less physiologic strain for critically ill AAO patients.6

The patient in this study had a constellation of risk factors for developing AAO due to thrombosis and consequently sustaining spinal cord infarction. Echocardiography ruled out embolism of a mural thrombus. She had cardiac dysfunction due to atrial fibrillation and left ventricular failure causing a low-flow state (LVEF 30%). She also had a hypercoagulable state due to bladder malignancy in addition to severe atherosclerotic disease. She was not on systemic anticoagulation therapy because of her high fall risk. Hence, her risk for thrombosis was quite high. Despite expedient revascularization surgery, her postoperative course was complicated as a result of severe mesenteric ischemia due to chronic SMA occlusion, which caused her death.

Conclusion

Acute aortic occlusion is a rare vascular emergency. The patient presenting with the abrupt onset of bilateral leg pain, neurologic deficits of paresis/paralysis, sensory disturbance, and/or sphincter dysfunction, and stigmata of vascular compromise with lower extremity mottling should alert the physician to AAO. Acute aortic occlusion continues to have high morbidity and mortality, and prompt recognition and appropriate transfer for surgical intervention are essential for improving outcomes.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

1. de Varona Frolov SR, Acosta Silva MP, Volvo Pérez G, Fiuza Pérez MD. Outcomes after treatment of acute aortic occlusion. [Article in English, Spanish] Cir Esp. 2015;93(9):573-579.

2. Dossa CD, Shepard AD, Reddy DJ, et al. Acute aortic occlusion: a 40-year experience. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):603-608.

3. Sandson TA, Friedman JH. Spinal cord infarction. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1989;68(5):282-292.

4. Yamamoto H, Yamamoto F, Tanaka F, et al. Acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta with concomitant internal iliac artery occlusion. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17(4):422-427.

5. Zainal AA, Oommen G, Chew LG, Yusha AW. Acute aortic occlusion: the need to be aware. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55(1):29-32.

6. Crawford JD, Perrone KH, Wong VW, et al. A modern series of acute aortic occlusion. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):1044-1050.

7. Babu SC, Shah PM, Nitahara J. Acute aortic occlusion—factors that influence outcome. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21(4):567-572.

8. Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, Howard JF Jr. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47(2):321-330.

9. Rosenthal D. Spinal cord ischemia after abdominal aortic operation: is it preventable? J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(3):391-397.

10. Triantafyllopoulos GK, Athanassacopoulos M, Maltezos C, Pneumaticos SG. Acute infrarenal aortic thrombosis presenting as flaccid paraplegia. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(15):E1042-E1045.

11. Nienaber CA. The role of imaging in acute aortic syndromes. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(1):15-23.

12. Bollinger B, Strandberg C, Baekgaard N, Mantoni M, Helweg-Larsen S. Diagnosis of acute aortic occlusion by computer tomography. Vasa. 1995;24(2):199-201.

13. Bertucci B, Rotundo A, Perri G, Sessa E, Tamburrini O. Acute thrombotic occlusion of the infrarenal abdominal aorta: its diagnosis with spiral computed tomography in a case [Article in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1997;94(5):541-543.

14. Battaglia S, Danesino GM, Danesino V, Castellani S. Color doppler ultrasonography of the abdominal aorta. J Ultrasound. 2010;13(3):107-117.

An unusual case of primary cardiac prosthetic valve-associated lymphoma

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

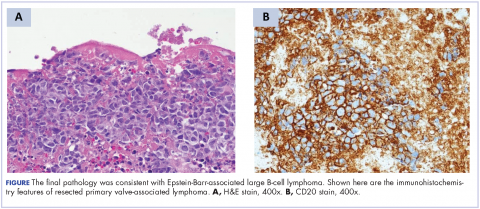

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare neoplasms with an incidence of less than 0.4%.1-3 Primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL), the majority of which is non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounts for around 2% of cardiac tumors and less than 0.5% of extranodal lymphomas.1,4-6 Primary lymphoma involving cardiac valves has been described in few case reports and small case series owing to its rarity.7-10 Most cases of PCL present with manifestations of congestive heart failure or cardiac arrhythmias,11 whereas primary valve-associated lymphoma (PV-AL) is usually diagnosed incidentally during valve repair or replacement. The pathophysiology remains unclear, but a few cases have been associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV).7 Cases previously described in the literature carried an overall poor prognosis and to date there is no standardized treatment approach. We provide here an unusual case of primary prosthetic valve-associated cardiac large B-cell lymphoma, which was successfully treated with adjuvant chemotherapy after valve repair and which resulted in an excellent long-term outcome.

Case presentation and summary

The patient presented in 2012 as a 65-year-old man with a history of ascending aortic aneurysm with secondary aortic insufficiency who in 2004 had undergone composite valve replacement of the aortic valve (AV) root and ascending aorta with a St Jude Toronto root. In June 2011, he was found to have a right parietal intraparenchymal hemorrhage that was thought to be a thromboembolic hemorrhagic ischemic stroke. In March 2012, he had routine follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging that incidentally showed a left frontal ischemic stroke with hemorrhagic conversion. In June 2012, he was found to have first degree atrioventricular block with episodic runs of supraventricular tachycardia.

In September 2012, transthoracic echocardiography was done for further evaluation of possible recurrent cryptogenic strokes. The results showed a hypo-echogenic mass within the proximal ascending aortic root, but this was not confirmed on transesophageal echocardiography. A chest computed-tomography (CT) scan was therefore performed, and it showed aneurysmal dilatation of the aortic root with an irregular marginal filling defect just above the AV suggestive of intraluminal thrombus. The patient was placed on full anticoagulation with warfarin and referred for cardiothoracic surgery to consider graft and valve replacement. However, 3 weeks later and before the surgery, the patient developed a third thromboembolic ischemic event (transient ischemic attack). The recurrent strokes were attributed to thromboembolic events secondary to prosthetic AV thrombosis.

A repeat transthoracic echocardiography was significant for an abnormal AV bioprosthesis with associated thrombus extending to the ascending aorta. Surgical excision and replacement of the AV conduit explant were performed in November 2012. The final pathology was consistent with EBV-associated large B-cell lymphoma (Figure). The initial staging evaluation, including a CT and positron-emission tomography scan and bone marrow biopsy, was negative for any systemic disease. The patient received 4 cycles of R-CHOP-21 (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/m2, doxorubicin 50 mg/m2 , vincristine 2 mg, and prednisone 100 mg) every 3 weeks in an “adjuvant” setting (because patient had no evidence of disease when given the systemic chemotherapy). The patient tolerated chemotherapy well without significant complications, and he is now over 36 months post-treatment without evidence of recurrent disease.

Discussion

Cardiac lymphoma limited only to prosthetic valves is rare, but it has been reported increasingly over the past few years. Until 2010, only six cases of PV-AL had been reported in the literature.7 Including our case, we identified four additional PubMed-indexed cases (using a PubMed search through February 2015). The patient characteristics and treatments received for all identified cases are described in the accompanying Table. The pathology from all of the cases revealed non-Hodgkin lymphoma of large B-cell subtype. PV-AL predominated among men (60%) and older patients with a median age of 62.5 years at diagnosis (range, 48-80 years). Patients had a median duration of 8 years (range, 4-24 years) from date of prosthesis placement to date of lymphoma diagnosis. The three most common presenting manifestations were valvular dysfunction, stroke, and congestive heart failure. All of the patients had surgical intervention on initial presentation. However, management after surgery was not uniform, with only 3 patients reported to have received systemic chemotherapy (Table). None of the patients received adjuvant radiation therapy. Calculated from date of diagnosis, survival duration ranged from less than a month7 to more than 36 months (as reported in our case).

The pathophysiology of PV-AL is not well understood given the rarity of the condition. Similar to other prosthetic-related neoplasms (metallic implants, breast implants),12-14 it has been hypothesized that chronic inflammation and EBV infection may play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this entity. Further, it has been suggested that Dacron, which is used in composite cardiac valve replacements, is carcinogenic and may play a role in some cases.7,15 PV-AL should be highly considered in the differential diagnosis of a suspicious prosthetic valve mass. Various imaging modalities, including echocardiography, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging have been described to have a role in the preoperative evaluation of cardiac tumors by assessing the cardiac function and defining the location and extent of the cardiac tumors.16-19

Given the rarity of this disease entity, there is no standardized approach for treatment. Surgical resection along with repair or replacement of primary involved prosthetic valve is essential for initial treatment. However, there is no consensus about the best approach for subsequent therapy. We cannot be conclusive about the optimum treatment, because of the limited number of published cases, but based on our reading of those cases, it would seem that early surgical intervention and “adjuvant” systemic therapy may have influenced prognosis. We speculate that poor outcomes in the first 6 months were most likely related to primary cardiopulmonary deterioration, whereas later poor outcomes were more likely to be attributable to recurrent lymphoma, particularly for patients who received suboptimal systemic chemotherapy treatment after surgery. All 3 patients who received chemotherapy had no evidence of recurrent disease at last follow-up. Of the 4 patients who received no chemotherapy and survived longer than 6 months (all except 1 died; Table), 2 had recurrent valve lymphoma, 1 had secondary systemic lymphoma, and 1 died of metastatic breast cancer. Those outcomes are in contrast to the 2 out of 3 patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy and who were reported to be alive at 16 and 36 months after diagnosis.

In conclusion, cardiac PV-AL is an increasingly recognized entity that warrants greater awareness among health care providers for early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention. Most of the cases are large B-cell lymphoma. Similar to patients with limited-stage DLBCL, fit patients should be highly considered for “adjuvant” systemic chemotherapy to optimize long-term outcomes. Reporting of similar cases is highly encouraged to better define this rare iatrogenic malignancy.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

1. Hudzik B, Miszalski-Jamka K, Glowacki J, et al. Malignant tumors of the heart. Cancer epidemiol. 2015;39(5):665-672.

2. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, eds. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

3. Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(1):107.

4. Neragi-Miandoab S, Kim J, Vlahakes GJ. Malignant tumours of the heart: a review of tumour type, diagnosis and therapy. Clin Oncol. 2007;19(10):748-756.

5. Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, Nair GM, Catton C, Yau T. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(4):219-228.

6. Burke A, Virmani R. Tumors of the heart and great vessels. In: Atlas of tumor pathology, 3rd Series, Fascicle 16. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1996.

7. Miller DV, Firchau DJ, McClure RF, Kurtin PJ, Feldman AL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arising on cardiac prostheses. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(3):377-384.

8. Albat B, Messner-Pellenc P, Thevenet A. Surgical treatment for primary lymphoma of the heart simulating prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108(1):188-189.

9. Bagwan IN, Desai S, Wotherspoon A, Sheppard MN. Unusual presentation of primary cardiac lymphoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(1):127-129.

10. Durrleman NM, El-Hamamsy I, Demaria RG, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Cardiac lymphoma following mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79(3):1040-1042.

11. Petrich A, Cho SI, Billett H. Primary cardiac lymphoma: an analysis of presentation, treatment, and outcome patterns. Cancer. 2011;117(3):581-589.

12. Cheuk W, Chan AC, Chan JK, Lau GT, Chan VN, Yiu HH. Metallic implant-associated lymphoma: a distinct subgroup of large B-cell lymphoma related to pyothorax-associated lymphoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):832-836.

13. Roden AC, Macon WR, Keeney GL, Myers JL, Feldman AL, Dogan A. Seroma-associated primary anaplastic large-cell lymphoma adjacent to breast implants: an indolent T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(4):455-463.

14. de Jong D, Vasmel WL, de Boer JP, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in women with breast implants. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2030-2035.

15. Durrleman N, El Hamamsy I, Demaria R, Carrier M, Perrault LP, Albat B. Is Dacron carcinogenic? Apropos of a case and review of the literature [In French]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 2004 Mar;97(3):267-270.16. Peters PJ, Reinhardt S. The echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac masses: a review. J Am Soc Echocard. 2006;19(2):230-240.

17. Gulati G, Sharma S, Kothari SS, Juneja R, Saxena A, Talwar KK. Comparison of echo and MRI in the imaging evaluation of intracardiac masses. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27(5):459-469.

18. Krombach GA, Spuentrup E, Buecker A, et al. Heart tumors: magnetic resonance imaging and multislice spiral CT [In German]. RoFo. 2005;177(9):1205-1218.

19. Hoey ET, Mankad K, Puppala S, Gopalan D, Sivananthan MU. MRI and CT appearances of cardiac tumours in adults. Clin Radiol. 2009;64(12):1214-1230.

20. Bonnichsen CR, Dearani JA, Maleszewski JJ, Colgan JP, Williamson EE, Ammash NM. Recurrent Epstein-Barr virus-associated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an ascending aorta graft. Circulation. 2013;128(13):1481-1483.

21. Berrio G, Suryadevara A, Singh NK, Wesly OH. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in an aortic valve allograft. Tex Heart Inst J. 2010;37(4):492-493.

22. Gruver AM, Huba MA, Dogan A, Hsi ED. Fibrin-associated large B-cell lymphoma: part of the spectrum of cardiac lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36(10):1527-1537.

23. Farah FJ, Chiles CD. Recurrent primary cardiac lymphoma on aortic valve allograft: implications for therapy. Tex Heart Inst J. 2014;41(5):543-546.

Durable response to pralatrexate for aggressive PTCL subtypes

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a heterogeneous group of mature T- and natural killer-cell neoplasms that comprise about 10%-15% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States.1,2 The development of effective therapies for PTCL has been challenging because of the rare nature and heterogeneity of these lymphomas. Most therapies are a derivative of aggressive B-cell lymphoma therapies, including CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vinicristine, prednisone) and CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vinicristine, etoposide, prednisone).1 Many centers use autologous or allogeneic stem cell transplant in this setting,1 but outcomes remain poor and progress in developing effective treatments has been slow.

Pralatrexate is the first drug to have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for treating patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL.3 As a folate analog metabolic inhibitor, pralatrexate competitively inhibits dihydrofolate reductase and reduces cellular levels of thymidine monophosphate, which prevents the cell from synthesizing genetic material and triggers it to undergo apoptosis.4 The agency’s approval of pralatrexate was based on results from the PROPEL study, which is possibly the largest prospective study conducted in patients with relapsed or refractory PTCL (109 evaluable patients).2 Findings from the study showed an overall response rate (ORR) of 29%, and a median duration of response (DoR) of 10 months.2

Pralatrexate is administered intravenously at 30 mg/m2 once weekly for 6 weeks of a 7-week treatment cycle. It is generally continued until disease progression or an unacceptable level of toxicity.2 Alternative dosing schedules have been described, including 15 mg/m2 once weekly for 3 weeks of a 4-week treatment cycle for cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.5

In this case series, we examine the outcomes of 2 patients with particularly aggressive subtypes of PTCL who were treated with pralatrexate. The significance of this report is in describing the long duration of response and reporting on a PTCL subtype – subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, alpha/beta type – that was underrepresented in the PROPEL study and is underreported in the literature.

Case presentations and summaries

Case 1

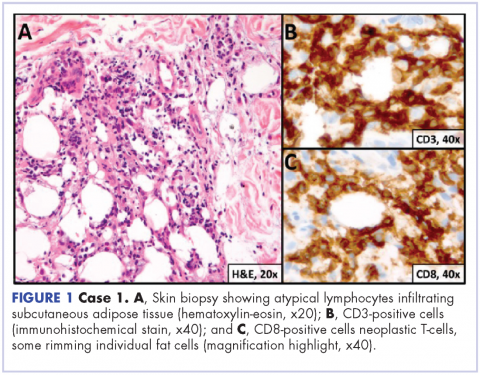

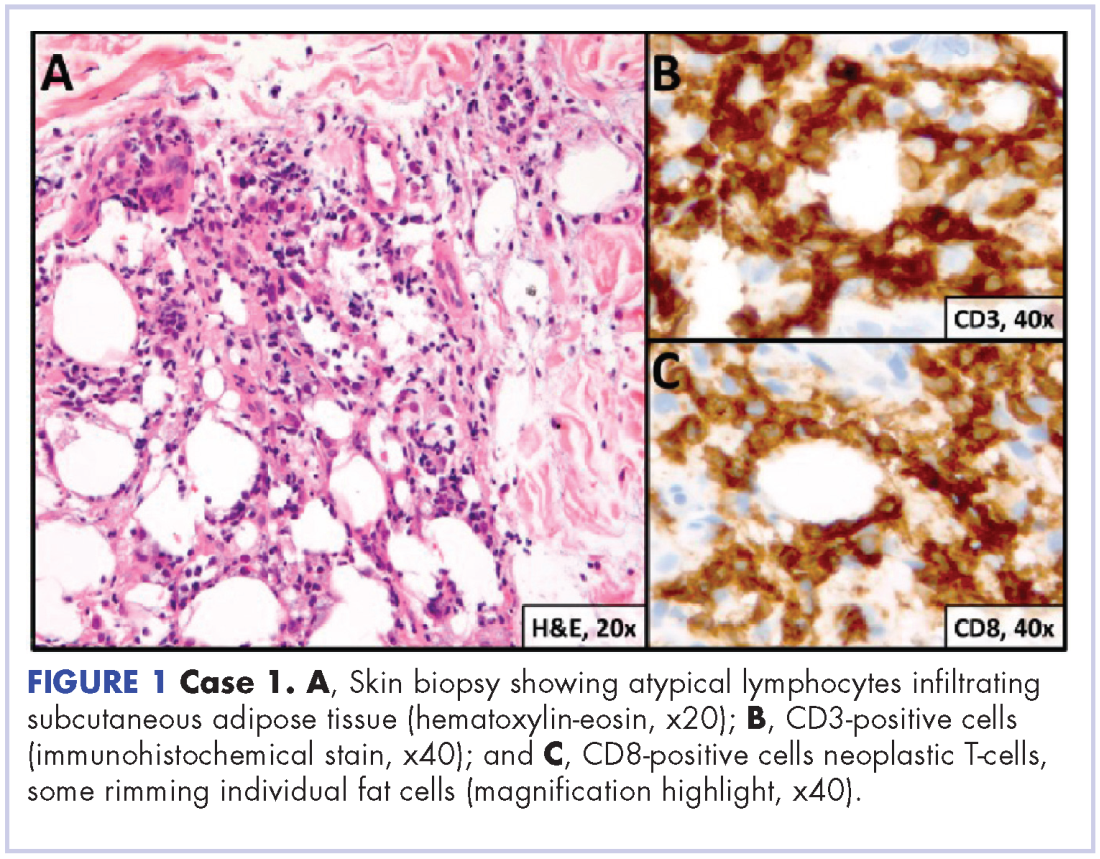

A 23-year-old Asian American man with a medical history of osteogenesis imperfecta presented to Emergency Department at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania with bilateral lower extremity edema, low-grade fevers, a weight loss of 25 lb, and flat hyperpigmented scaly skin patches across his torso. Symptoms had started manifesting around five months prior to the visit. A punch biopsy of a skin lesion revealed skin tissue with focal infiltrate of small- to medium-sized, atypical lymphocytes infiltrating subcutaneous adipose tissue (panniculitis-like) and adnexa. Immunohistochemical stains showed that the abnormal lymphocytes were positive for CD3, CD8, perforin, granzyme B, TIA-1 (minor subset), and TCR beta; and negative for CD4, CD56, and CD30. Proliferation index (Ki67) was 70%. The findings were consistent with primary subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, alpha/beta type (Figure 1). A staging positron-emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) scan demonstrated stage IVB lymphoma with subcutaneous involvement without nodal disease.

He was initially treated with aggressive combination regimens including EPOCH (etoposide, prednisolone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin) and ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), but he had no response and his disease was primary refractory. Because of his osteogenesis imperfecta, he was not a candidate for allogenic stem cell transplant.

He responded to hyperCVAD B combination therapy (methotrexate and cytarabine), but the course was complicated by cytarabine-induced ataxia and dysarthia. He was then treated with 3 months of intravenous alemtuzumab without response. Intravenous methotrexate (2,000 mg/m2) was then used for 3 cycles, but this exacerbated his previous cytarabine-induced neurological symptoms and resulted in only partial response with persistent fluorine-18-deoxyglucose (FDG) avid lesions on a subsequent PET–CT scan.

At that point, the patient was started on pralatrexate at 15 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks on a 4-week cycle schedule. This was his fifth line of therapy and at 16 months from his initial diagnosis. This dosage was continued for 6 months, and he tolerated the therapy well. He reported no exacerbations of his dysarthia, and by the second month, he had achieved clinical and radiographic remission with complete resolution of B symptoms (fevers, night sweats, and weight loss). The dosing was modified to 15 mg/m2 every 2 weeks for 3 months. A whole body PET–CT scan showed resolution of previously FDG avid lesions.

The patient was then continued on 15 mg/m2 pralatrexate every 3 weeks for 1 year and he has been maintained on once-a-month dosing for a second and now third year of therapy. He continues to tolerate the therapy and remains disease free at nearly 2 years since starting pralatrexate.

Case 2

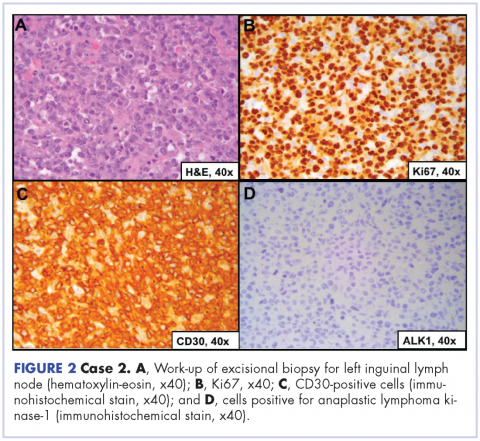

A 64-year-old white man with a medical history of myasthenia gravis (in remission) and invasive thymoma (after thymectomy) presented with diffuse bulky lymphadenopathy and lung lesions to outpatient clinic at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania. His LDH was elevated (278 U/L, reference range 98-192 U/L). Excisional biopsy of a left inguinal lymph node revealed sheets of mitotically active large cells with oval to irregular nuclei, clumped chromatin, conspicuous and sometimes multiple nucleoli, and ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining showed that the neoplastic cells were positive for CD3, CD4, CD30, BCL2 (variable), and MUM1; and negative for ALK 1, CD5, CD8, CD15, CD43, and CD56. Proliferation index (Ki67) was 90% (Figure 2). PET-CT scan showed widespread hypermetabolic lymphoma in the chest, neck, abdomen, and pelvis with pulmonary metastases. Imaging also demonstrated FDG-avid lesions in the gastric and sinus area. The findings were consistent with ALK-negative, anaplastic large cell lymphoma. He was stage IVA; had gastric, lung, and sinus involvement; and disease above and below the diaphragm.

The patient was initially treated with 6 cycles of CHOP and intrathecal methotrexate injections. His post-treatment PET–CT scan showed persistent FDG-avid disease and his LDH level remained elevated. He underwent 1 cycle of ICE and then BCV (busulfan, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) autologous stem cell transplant. Post-transplant PET–CT scan showed improvement from previous 2 scans but still showed several hypermetabolic lymph nodes consistent with persistent disease.

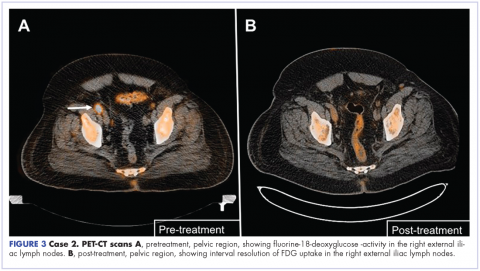

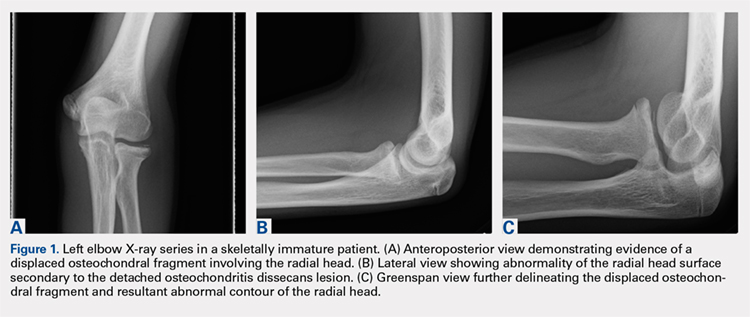

The patient was started on a pralatrexate regimen of 30 mg/m2 once weekly for 6 weeks of a 7-week treatment cycle. After 5 doses, he developed thrombocytopenia and mucositis, which were deemed pralatrexate related. The dosage was reduced to 20 mg/m2 once weekly with variable frequency depending on tolerability. His response assessment with PET–CT scan demonstrated radiographic complete response with resolution of hypermetabolic lesions (Figure 3B).

He then proceeded with pralatrexate for 4 more doses. PET-CT imaging 2 months after the last dose of pralatrexate was consistent with metabolic complete response, and he opted to hold further therapy. His last imaging at 4 years after completion of therapy showed continued remission. At press time, he had been clinically disease free for more than 6 years after his last dose of pralatrexate.

Discussion