User login

A sleeping beast: Obstructive sleep apnea and stroke

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke and may also, infrequently, be a consequence of stroke. It is significantly underdiagnosed in the general population and is highly prevalent in patients who have had a stroke. Many patients likely had their stroke because of this chronic untreated condition.

This review focuses on OSA and its prevalence, consequences, and treatment in patients after a stroke.

DEFINING AND QUANTIFYING OSA

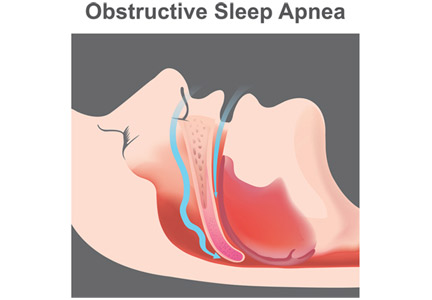

OSA is the most common type of sleep-disordered breathing.1,2 It involves repeated narrowing or complete collapse of the upper airway despite ongoing respiratory effort.3,4 Apneic episodes are terminated by arousals from hypoxemia or efforts to breathe.5 In contrast, central sleep apnea is characterized by a patent airway but lack of airflow due to absent respiratory effort.5

In OSA, the number of episodes of apnea (absent airflow) and hypopnea (reduced airflow) are added together and divided by hours of sleep to calculate the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). OSA is diagnosed by either of the following3,4:

- AHI of 5 or higher, with clinical symptoms related to OSA (described below)

- AHI of 15 or higher, regardless of symptoms.

The AHI also defines OSA severity, as follows3:

- Mild: AHI 5 to 15

- Moderate: AHI 15 to 30

- Severe: AHI greater than 30.

Diagnostic criteria (eg, definition of hypopnea, testing methods, and AHI thresholds) have varied over time, an important consideration when reviewing the literature.

OSA IS MORE COMMON THAN EXPECTED AFTER STROKE

In the most methodologically sound and generalizable study of this topic to date, the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study6 reported in 2013 that about 14% of men and 5% of women ages 30 to 70 have an AHI greater than 5 (using 4% desaturation to score hypopneic episodes) with daytime sleepiness. Other studies suggest that 80% to 90% of people with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.1,7

The prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke is much higher, ranging from 30% to 96% depending on the study methods and population.1,8–12 A 2010 meta-analysis11 of 29 studies reported that 72% of patients who had a stroke had an AHI greater than 5, and 29% had severe OSA. In this analysis, 7% of those with sleep-disordered breathing had central sleep apnea; still, these data indicate that the prevalence of OSA in these patients is about 5 times higher than in the general population.

RISK FACTORS MAY DIFFER IN STROKE POPULATION

Several risk factors for OSA have been identified.

Obesity is one of the strongest risk factors, with increasing body mass index (BMI) associated with increased OSA prevalence.4,6,13 However, obesity appears to be a less significant risk factor in patients who have had a stroke than in the general population. In the 2010 meta-analysis11 of OSA after stroke, the average BMI was only 26.4 kg/m2 (with obesity defined as a BMI > 30.0 kg/m2), and increasing BMI was not associated with increasing AHI.

Male sex and advanced age are also OSA risk factors.4,5 They remain significant in patients after a stroke; about 65% of poststroke patients who have OSA are men, and the older the patient, the more likely the AHI is greater than 10.11

Ethnicity and genetics may also play important roles in OSA risk, with roughly 25% of OSA prevalence estimated to have a genetic basis.14,15 Some risk factors for OSA such as craniofacial shape, upper airway anatomy, upper airway muscle dysfunction, increased respiratory chemosensitivity, and poor arousal threshold during sleep are likely determined by genetics and ethnicity.14,15 Compared with people of European origin, Asians have a similar prevalence of OSA, but at a much lower average BMI, suggesting that other factors are significant.14 Possible genetically determined anatomic risk factors have not been specifically studied in the poststroke population, but it can be assumed they remain relevant.

Several studies have tried to find an association between OSA and type, location, etiology, or pattern of stroke.10,11,16–19 Although some suggest links between cardioembolic stroke and OSA,16,20 or thrombolysis and OSA,10 most have found no association between OSA and stroke features.11,12,21,22

HOW DOES OSA INCREASE STROKE RISK?

Untreated severe OSA is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality,21,22 and OSA is an independent risk factor for incident stroke.23 A number of mechanisms may explain these relationships.

Intermittent hypoxemia and recurrent sympathetic arousals resulting from OSA are thought to lead to many of the comorbid conditions with which it is associated: hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke. Repetitive decreases in ventilation lead to oxygen desaturations that result in cycles of increased sympathetic outflow and eventual sustained nocturnal hypertension and daytime chronic hypertension.1,5,9,13 Also implicated are various changes in vasodilator and vasoconstrictor substances due to endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, which are thought to play a role in the atherogenic and prothrombotic states induced by OSA.1,5,13

Cerebral circulation is altered primarily by the changes in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2). During apnea, the Pco2 rises, causing vasodilation and increased blood flow. After the apnea resolves, there is hyperpnea with resultant decreased Pco2, and vasoconstriction. In a patient who already has vascular disease, the enhanced vasoconstriction could lead to ischemia.1,5

Changes in intrathoracic pressure result in distortion of cardiac architecture. When the patient tries to breathe against an occluded airway, the intrathoracic pressure becomes more and more negative, increasing preload and afterload. When this happens repeatedly every night for years, it leads to remodeling of the heart such as left and right ventricular hypertrophy, with reduced stroke volume, myocardial ischemia, and increased risk of arrhythmia.1,5,13

Untreated OSA is believed to predispose patients to develop atrial fibrillation through sympathetic overactivity, vascular inflammation, heart rate variability, and cardiac remodeling.24 As atrial fibrillation is a major risk factor for stroke, particularly cardioembolic stroke, it may be another pathway of increased stroke risk in OSA.16,20,25

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF OSA NOT OBVIOUS AFTER STROKE

OSA typically causes both daytime symptoms (excessive sleepiness, poor concentration, morning headache, depressive symptoms) and nighttime signs and symptoms (snoring, choking, gasping, night sweats, insomnia, nocturia, witnessed episodes of apnea).3,4,26 Unfortunately, because these are nonspecific, OSA is often underdiagnosed.4,26

Identifying OSA after a stroke may be a particular challenge, as patients often do not report classic symptoms, and the typical picture of OSA may have less predictive validity in these patients.1,27,28 Within the first 24 hours after a stroke, hypersomnia, snoring history, and age are not predictive of OSA.1 Patients found to have OSA after a stroke frequently do not have the traditional symptoms (sleepiness, snoring) seen in usual OSA patients. And they have higher rates of OSA at a younger age than the usual OSA patients, so age is not a predictive risk factor. In addition, daytime sleepiness and obesity are often absent or less prominent.1,9,27,28 Finally, typical OSA signs and symptoms may be attributed to the stroke itself or to comorbidities affecting the patient, lowering suspicion for OSA.

OSA MAY HINDER STROKE RECOVERY, WORSEN OUTCOMES

OSA, particularly when moderate to severe, is linked to pathophysiologic changes that can hinder recovery from a stroke.

Intermittent hypoxemia during sleep can worsen vascular damage of at-risk tissue: nocturnal hypoxemia correlates with white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging, a marker of ischemic demyelination.29 Oxidative stress and release of inflammatory mediators associated with intermittent hypoxemia may impair vascular blood flow to brain tissue attempting to repair itself.30 In addition, sympathetic overactivity and Pco2 fluctuations associated with OSA may impede cerebral circulation.

Taken together, such ongoing nocturnal insults can lead to clinical consequences during this vulnerable period.

A 1996 study31 of patients recovering from a stroke found that an oxygen desaturation index (number of times that the blood oxygen level drops below a certain threshold, as measured by overnight oximetry) of more than 10 per hour was associated with worse functional recovery at discharge and at 3 and 12 months after discharge. This study also noted an association between time spent with oxygen saturations below 90% and the rate of death at 1 year.

A 2003 study32 reported that patients with an AHI greater than 10 by polysomnography spent an average of 13 days longer on the rehabilitation service and had worse functional and cognitive status on discharge, even after controlling for multiple confounders. Several subsequent studies have confirmed these and similar findings.8,33,34

OSA has also been linked to depression,35 which is common after stroke and may worsen outcomes.36 The interaction between OSA, depression, and poststroke outcomes warrants further study.

In the general population, OSA has been independently associated with increased risk of stroke or death from any cause.21,22,37 These associations have also been reported in the poststroke population: a 2014 meta-analysis found that OSA increased the risk of a repeat stroke (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–2.6) and all-cause mortality (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.4–2.1).38

TESTING FOR OSA AFTER STROKE

Because of the high prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke and the potential for worse outcomes associated with untreated OSA, there should be a low threshold for evaluating for OSA soon after stroke. Objective testing is required to qualify for therapy, and the gold standard for diagnosis of OSA is formal polysomnography conducted in a sleep laboratory.2–4 Unfortunately, polysomnography may be unacceptable to some patients, is costly, and is resource-intensive, particularly in an inpatient or rehabilitation setting.28 Ideally, to optimize testing efficiency, patients should be screened for the likelihood of OSA before polysomnography is ordered.

Questionnaires can help determine the need for further testing

Questionnaires developed to assess OSA risk39 include the following:

The Berlin questionnaire, developed in 1999, has 10 questions assessing daytime and nighttime signs and symptoms and presence of hypertension.

The STOP questionnaire, developed in 2008, assesses snoring, tiredness, observed apneic episodes, and elevated blood pressure.

The STOP-BANG questionnaire, published in 2010, includes the STOP questions plus BMI over 35 kg/m2, age over 50, neck circumference over 41 cm, and male gender.

A 2017 meta-analysis39 of 108 studies with nearly 50,000 people found that the STOP-BANG questionnaire performed best with regard to sensitivity and diagnostic odds ratio, but with poor specificity.

These screening tools and modified versions of them have also been evaluated in patients who have had a stroke.

In 2015, Boulos et al28 found that the STOP-BAG (a version of STOP-BANG that excludes neck circumference) and the 4-variable (4V) questionnaire (sex, BMI, blood pressure, snoring) had moderate predictive value for OSA within 6 months after sroke.

In 2016, Katzan et al40 found that the STOP-BAG2 (STOP-BAG criteria plus continuous variables for BMI and age) had a high sensitivity for polysomnographically diagnosed OSA within the first year after a stroke. The specificity was significantly better than the STOP-BANG or the STOP-BAG questionnaire, although it remained suboptimal at 60.5%.

In 2017, Sico et al41 developed and assessed the SLEEP Inventory (sex, left heart failure, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, enlarged neck, weight in pounds, insulin resistance or diabetes, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) and found that it outperformed the Berlin and STOP-BANG questionnaires in the poststroke setting. The SLEEP Inventory had the best specificity and negative predictive value, and a slightly better ability to correctly classify patients as having OSA or not, classifying 80% of patients correctly.

These newer screening tools (eg, STOP-BAG, STOP-BAG2, SLEEP) can be used to identify with reasonable accuracy which patients need definitive testing after stroke.

Pulse oximetry is another possible screening tool

Overnight pulse oximetry may also help screen for sleep apnea and stratify risk after a stroke. A 2012 study42 of overnight oximetry to screen patients before surgery found that the oxygen desaturation index was significantly associated with the AHI measured by polysomnography. However, oximetry testing cannot distinguish between OSA and central sleep apnea, so it is insufficient to diagnose OSA or qualify patients for therapy. Further study is needed to examine the ability of overnight pulse oximetry to screen or to stratify risk for OSA after stroke.

Polysomnography vs home testing

Polysomnography is the gold standard for diagnosing OSA. Benefits include technical support and trouble-shooting, determining relationships between OSA, body position, and sleep stage, and the ability to intervene with treatment.2 However, polysomnography can be cumbersome, costly, and resource-intensive.

A home sleep apnea test, ie, an unattended, limited-channel sleep study, may be an acceptable alternative.2–4,43,44 Home testing does not require a sleep technologist to be present during testing, uses fewer sensors, and is less expensive than overnight polysomnography, but its utility can be limited: it fails to accurately discriminate between episodes of OSA and central sleep apnea, there is potential for false-negative results, and it can underestimate sleep apnea burden because it does not measure sleep.2

Institutional resources and logistics may influence the choice of diagnostic modality. No data exist on outcomes from different diagnostic testing methods in poststroke patients. Further research is needed.

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY: BENEFITS, CHALLENGES, ALTERNATIVES

The first-line treatment for OSA is positive airway pressure (PAP).3 For most patients, this is continuous PAP (CPAP) or autoadjusting PAP (APAP). In some instances, particularly for those who cannot tolerate CPAP or who have comorbid hypoventilation, bilevel PAP (BPAP) may be indicated. More advanced PAP therapies are unlikely to be used after stroke.

PAP therapy is associated with reduced daytime sleepiness, improved mood, normalization of sleep architecture, improved systemic and pulmonary artery blood pressure, reduced rates of atrial fibrillation after ablation, and improved insulin sensitivity.45–49 Whether it reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, including stroke, remains controversial; most data suggest that it does not.50,51 However, when adherence to PAP therapy is considered rather than intention to treat, treatment has been found to lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes.52

Mixed evidence of benefits after stroke

Observational studies provide evidence that CPAP may help patients with OSA after stroke, although results are mixed.53–58 The studies ranged in size from 14 to 105 patients, enrolled patients with mostly moderate to severe OSA, and followed patients from 10 days to 7 years. Adherence to therapy was generally good in the short term (50%–70%), but only 15% to 30% of patients remained adherent at 5 to 7 years. Variable outcomes were reported, with some studies finding improved symptoms in the near term and mixed evidence of cardiovascular benefit in the longer ones. However, as these studies lacked randomization, drawing definitive conclusions on CPAP efficacy is difficult.

Patients were enrolled in the index admission or when starting a rehabilitation service—generally 2 to 3 weeks after their stroke. No clear association was found between the timing of initiating PAP therapy and outcomes. All patients had ischemic strokes, but few details were provided regarding stroke location, size, and severity. Exclusion criteria included severe underlying cardiopulmonary disease, confusion, severe stroke with marked impairment, and inability to cooperate. Almost all patients had moderate to severe OSA, and patients with central sleep apnea were excluded.

The major outcomes examined were drop-out rates, PAP adherence, and neurologic improvement based on neurologic functional scales (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and Canadian Neurologic Scale). As expected, dropout rates were higher in patients randomized to CPAP (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.05–3.21, P = .03), although overall adherence was better than anticipated, with mean CPAP use across trials of 4.5 hours per night (95% CI 3.97–5.08) and with about 50% to 60% of patients adhering to therapy for at least 4 hours nightly.

Improvement in neurologic outcomes favored CPAP (standard mean difference 0.54, 95% CI 0.026–1.05), although considerable heterogeneity was seen. Improved sleepiness outcomes were inconsistent. Major cardiovascular outcomes were reported in only 2 studies (using the same data set) and showed delayed time to the next cardiovascular event for those treated with CPAP but no difference in cardiovascular event-free survival.

PAP poses more challenges after stroke

The primary limitation to PAP therapy is poor acceptance and adherence to therapy.59 High rates of refusal of therapy and difficulty complying with treatment have been noted in the poststroke population, although recent studies have reported better adherence rates. How rates of adherence play out in real-world settings, outside of the controlled environment of a research study, has yet to be determined.

In general, CPAP adherence is affected by claustrophobia, difficulty tolerating a mask, problems with pressure intolerance, irritating air leaks, nasal congestion, and naso-oral dryness. Many such barriers can be overcome with use of a properly fitted mask, an appropriate pressure setting, heated humidification, nasal sprays (eg, saline, inhaled steroids), and education, encouragement, and reassurance.

After a stroke, additional obstacles may impede the ability to use PAP therapy.68 Facial paresis (hemi- or bifacial) may make fitting of the mask problematic. Paralysis or weakness of the extremities may limit the ability to adjust or remove a mask. Aphasia can impair communication and understanding of the need to use PAP therapy, and upper-airway problems related to stroke, including dysphagia, may lead to pressure intolerance or risk of aspiration. Finally, a lack of perceived benefit, particularly if the patient does not have daytime sleepiness, may limit motivation.

Consider alternatives

For patients unlikely to succeed with PAP therapy, there are alternatives. Surgery and oral appliances are not usually realistic options in the setting of recent stroke, but positional therapy, including the use of body positioners to prevent supine sleep, as well as elevating the head of the bed, may be of some benefit.69,70 A nasopharyngeal airway stenting device (nasal trumpet) may also be tolerated by some patients.

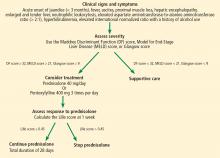

A proposed algorithm for screening, diagnosing, and treating OSA in patients after stroke is presented in Figure 1.

- Selim B, Roux FJ. Stroke and sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin 2012; 7(4):597–607. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2012.08.007

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13(3):479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

- Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al; Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management, and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009; 5(3):263–276. pmid:19960649

- Patil SP, Schneider H, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Adult obstructive sleep apnea: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Chest 2007; 132(1):325–337. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0040

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev 2010; 90(1):47–112. doi:10.1152/physrev.00043.2008

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177(9):1006–1014. doi:10.1093/aje/kws342

- Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, Loredo J, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2014; 189(3):335–344. doi:10.1164/rccm.201309-1735OC

- Aaronson JA, van Bennekom CA, Hofman WF, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is related to impaired cognitive and functional status after stroke. Sleep 2015; 38(9):1431–1437. doi:10.5665/sleep.4984

- Sharma S, Culebras A. Sleep apnoea and stroke. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2016; 1(4):185–191. doi:10.1136/svn-2016-000038

- Huhtakangas JK, Huhtakangas J, Bloigu R, Saaresranta T. Prevalence of sleep apnea at the acute phase of ischemic stroke with or without thrombolysis. Sleep Med 2017; 40:40–46. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.018

- Johnson KG, Johnson DC. Frequency of sleep apnea in stroke and TIA patients: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2010; 6(2):131–137. pmid:20411688

- Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Berenguer J, Sanchez M, Chamorro A. Prevalence and clinical importance of sleep apnea in the first night after cerebral infarction. Neurology 2002; 58:911–916. pmid:11914407

- Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):841–858. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069

- Dudley KA, Patel SR. Disparities and genetic risk factors in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2016; 18:96–102. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.015

- Redline S, Tishler PV. The genetics of sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev 2000; 4(6):583–602. doi:10.1053/smrv.2000.0120

- Lipford MC, Flemming KD, Calvin AD, et al. Associations between cardioembolic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2015; 38(11):1699–1705. doi:10.5665/sleep.5146

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen J, Yi X, Dong S, Cao L. Stroke patterns, topography, and etiology in patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017; 10(4):7137–7143.

- Fisse AL, Kemmling A, Teuber A, et al. The association of lesion location and sleep related breathing disorder in patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One 2017; 12(1):e0171243. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171243

- Brown DL, Mowla A, McDermott M, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype and presence of sleep-disordered breathing: the BASIC sleep apnea study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015; 24(2):388–393. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.09.007

- Poli M, Philip P, Taillard J, et al. Atrial fibrillation as a major cause of stroke in apneic patients: a prospective study. Sleep Med 2017; 30:251–254. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.07.031

- Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep 2008; 31(8):1071–1078. pmid:18714778

- Molnar MZ, Mucsi I, Novak M, et al. Association of incident obstructive sleep apnoea with outcomes in a large cohort of US veterans. Thorax 2015; 70(9):888–895. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206970

- Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182(2):269–277. doi:10.1164/rccm.200911-1746OC

- Marulanda-Londono E, Chaturvedi S. The interplay between obstructive sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation. Fron Neurol 2017; 8:668. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00668

- Szymanski FM, Filipiak KJ, Platek AE, Hrynkiewicz-Szymanska A, Karpinski G, Opolski G. Assessment of CHADS2 and CHA 2DS 2-VASc scores in obstructive sleep apnea patients with atrial fibrillation. Sleep Breath 2015; 19(2):531–537. doi:10.1007/s11325-014-1042-5

- Stansbury RC, Strollo PJ. Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea. J Thoracic Dis 2015; 7(9):E298–E310. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.13

- Chan W, Coutts SB, Hanly P. Sleep apnea in patients with transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: opportunity for risk reduction of recurrent stroke? Stroke 2010; 41(12):2973–2975. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596759

- Boulos MI, Wan A, Im J, et al. Identifying obstructive sleep apnea after stroke/TIA: evaluating four simple screening tools. Sleep Med 2016; 21:133–139. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.12.013

- Patel SK, Hanly PJ, Smith EE, Chan W, Coutts SB. Nocturnal hypoxemia is associated with white matter hyperintensities in patients with a minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Clin Sleep Med 2015; 11(12):1417–1424. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5278

- McCarty MF, DiNicolantonio JJ, O’Keefe JH. NADPH oxidase, uncoupled endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and NF-KappaB are key mediators of the pathogenic impact of obstructive sleep apnea—therapeutic implications. J Integr Cardiol 2016; 2(5):367–374. doi:10.15761/JIC.1000177

- Good DC, Henkle JQ, Gelber D, Welsh J, Verhulst S. Sleep-disordered breathing and poor functional outcome after stroke. Stroke 1996; 27(2):252–259. pmid:8571419

- Kaneko Y, Hajek VE, Zivanovic V, Raboud J, Bradley TD. Relationship of sleep apnea to functional capacity and length of hospitalization following stroke. Sleep 2003; 26(3):293–297. pmid:12749548

- Yan-fang S, Yu-ping W. Sleep-disordered breathing: impact on functional outcome of ischemic stroke patients. Sleep Med 2009; 10(7):717–719. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.006

- Kumar R, Suri JC, Manocha R. Study of association of severity of sleep disordered breathing and functional outcome in stroke patients. Sleep Med 2017; 34:50–56. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.02.025

- Kerner NA, Roose SP. Obstructive sleep apnea is linked to depression and cognitive impairment: evidence and potential mechanisms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016; 24(6):496–508. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2016.01.134

- Bartoli F, Lillia N, Lax A, et al. Depression after stroke and risk of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke Res Treat 2013; 2013:862978. doi:10.1155/2013/862978

- Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med 2005; 353(19):2034–2041. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043104

- Xie W, Zheng F, Song X. Obstructive sleep apnea and serious adverse outcomes in patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014; 93(29):e336. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000336

- Chiu HY, Chen PY, Chuang LP, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire, STOP-BANG, STOP, and Epworth sleepiness scale in detecting obstructive sleep apnea: a bivariate meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2017; 36:57–70. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2016.10.004

- Katzan IL, Thompson NR, Uchino K, Foldvary-Schaefer N. A screening tool for obstructive sleep apnea in cerebrovascular patients. Sleep Med 2016; 21:70–76. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.02.001

- Sico JJ, Yaggi HK, Ofner S, et al. Development, validation, and assessment of an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack-specific prediction tool for obstructive sleep apnea. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017; 26(8):1745–1754. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.03.042

- Chung F, Liao P, Elsaid H, Islam S, Shapiro CM, Sun Y. Oxygen desaturation index from nocturnal oximetry: a sensitive and specific tool to detect sleep-disordered breathing in surgical patients. Anesth Analg 2012; 114(5):993–1000. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e318248f4f5

- Boulos MI, Elias S, Wan A, et al. Unattended hospital and home sleep apnea testing following cerebrovascular events. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2017; 26(1):143–149. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.09.001

- Saletu MT, Kotzian ST, Schwarzinger A, Haider S, Spatt J, Saletu B. Home sleep apnea testing is a feasible and accurate method to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea in stroke patients during in-hospital rehabilitation. J Clin Sleep Med 2018; 14(9):1495–1501. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7322

- Giles TL, Lasserson TJ, Smith BH, White J, Wright J, Cates CJ. Continuous positive airways pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (3):CD001106. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001106.pub3

- Fatureto-Borges F, Lorenzi-Filho G, Drager LF. Effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure in lowering blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a critical review of the literature. Integr Blood Press Control 2016; 9:43–47. doi:10.2147/IBPC.S70402

- Imran TF, Gharzipura M, Liu S, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on pulmonary artery pressure in patients with isolated obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2016; 21(5):591–598. doi:10.1007/s10741-016-9548-5

- Deng F, Raza A, Guo J. Treating obstructive sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure reduces risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation after catheter ablation: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med 2018; 46:5–11. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.02.013

- Seetho IW, Wilding JPH. Sleep-disordered breathing, type 2 diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. Chronic Resp Dis 2014; 11(4):257–275. doi:10.1177/1479972314552806

- Kim Y, Koo YS, Lee HY, Lee SY. Can continuous positive airway pressure reduce the risk of stroke in obstructive sleep apnea patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS ONE 2016; 11(1):e0146317. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146317

- Yu J, Zhou Z, McEvoy RD, et al. Association of positive airway pressure with cardiovascular events and death in adults with sleep apnea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2017; 318(2):156–166. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7967

- Peker Y, Glantz H, Eulenburg C, Wegscheider K, Herlitz J, Thunström E. Effect of positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease patients with nonsleepy obstructive sleep apnea. The RICCADSA randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 194(5):613–620. doi:10.1164/rccm.201601-0088OC

- Martinez-Garcia MA, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Ejarque-Martinez L, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment reduces mortality in patients with ischemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a 5-year follow-up study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180(1):36–41. doi:10.1164/rccm.200808-1341OC

- Broadley SA, Jorgensen L, Cheek A, et al. Early investigation and treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea after acute stroke. J Clin Neurosci 2007; 14(4):328–333. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2006.01.017

- Wessendorf TE, Wang YM, Thilmann AF, Sorgenfrei U, Konietzko N, Teschler H. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea with nasal continuous positive airway pressure in stroke. Eur Respir J 2001; 18(4):623–629. pmid:11716165

- Bassetti CL, Milanova M, Gugger M. Sleep-disordered breathing and acute ischemic stroke: diagnosis, risk factors, treatment, evolution, and long-term clinical outcome. Stroke 2006; 37(4):967–972. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000208215.49243.c3

- Palombini L, Guilleminault C. Stroke and treatment with nasal CPAP. Eur J Neurol 2006; 13(2):198–200. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01169.x

- Martínez-García MA, Campos-Rodríguez F, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Catalán-Serra P, Román-Sánchez P, Montserrat JM. Increased incidence of nonfatal cardiovascular events in stroke patients with sleep apnoea: effect of CPAP treatment. Eur Respir J 2012; 39(4):906–912. doi:10.1183/09031936.00011311

- Brill AK, Horvath T, Seiler A, et al. CPAP as treatment of sleep apnea after stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Neurology 2018; 90(14):e1222–e1230. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005262

- Hsu C, Vennelle M, Li H, Engleman HM, Dennis MS, Douglas NJ. Sleep-disordered breathing after stroke: a randomised controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006; 77(10):1143–1149. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.086686

- Parra O, Sanchez-Armengol A, Bonnin M, et al. Early treatment of obstructive apnoea and stroke outcome: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Resp J 2011; 37(5):1128–1136. doi:10.1183/09031936.00034410

- Ryan CM, Bayley M, Green R, Murray BJ, Bradley TD. Influence of continuous positive airway pressure on outcomes of rehabilitation in stroke patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Stroke 2011; 42(4):1062–1067. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597468

- Bravata DM, Concato J, Fried T, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure: evaluation of a novel therapy for patients with acute ischemic stroke. Sleep 2011; 34(9):1271–1277. doi:10.5665/SLEEP.1254

- Parra O, Sanchez-Armengol A, Capote F, et al. Efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on 5-year survival in patients with ischaemic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. J Sleep Res 2015; 24(1):47–53. doi:10.1111/jsr.12181

- Khot SP, Davis AP, Crane DA, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on stroke rehabilitation: a pilot randomized sham-controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med 2016; 12(7):1019–1026. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5940

- Aaronson JA, Hofman WF, van Bennekom CA, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cognitive and functional outcome of stroke patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med 2016; 12(4):533–541. doi:10.5664/jcsm.5684

- Gupta A, Shukla G, Afsar M, et al. Role of positive airway pressure therapy for obstructive sleep apnea in patients with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med 2018; 14(4):511–521. doi:10.5664/jcsm.7034

- Mello-Fujita L, Kim LJ, Palombini Lde O, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome associated with stroke. Sleep Med 2015; 16(6):691–696. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.12.017

- Svatikova A, Chervin RD, Wing JJ, Sanchez BN, Migda EM, Brown DL. Positional therapy in ischemic stroke patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2011; 12(3):262–266. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.008

- Souza FJ, Genta PR, de Souza Filho AJ, Wellman A, Lorenzi-Filho G. The influence of head-of-bed elevation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2017; 21(4):815–820. doi:10.1007/s11325-017-1524-3

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke and may also, infrequently, be a consequence of stroke. It is significantly underdiagnosed in the general population and is highly prevalent in patients who have had a stroke. Many patients likely had their stroke because of this chronic untreated condition.

This review focuses on OSA and its prevalence, consequences, and treatment in patients after a stroke.

DEFINING AND QUANTIFYING OSA

OSA is the most common type of sleep-disordered breathing.1,2 It involves repeated narrowing or complete collapse of the upper airway despite ongoing respiratory effort.3,4 Apneic episodes are terminated by arousals from hypoxemia or efforts to breathe.5 In contrast, central sleep apnea is characterized by a patent airway but lack of airflow due to absent respiratory effort.5

In OSA, the number of episodes of apnea (absent airflow) and hypopnea (reduced airflow) are added together and divided by hours of sleep to calculate the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). OSA is diagnosed by either of the following3,4:

- AHI of 5 or higher, with clinical symptoms related to OSA (described below)

- AHI of 15 or higher, regardless of symptoms.

The AHI also defines OSA severity, as follows3:

- Mild: AHI 5 to 15

- Moderate: AHI 15 to 30

- Severe: AHI greater than 30.

Diagnostic criteria (eg, definition of hypopnea, testing methods, and AHI thresholds) have varied over time, an important consideration when reviewing the literature.

OSA IS MORE COMMON THAN EXPECTED AFTER STROKE

In the most methodologically sound and generalizable study of this topic to date, the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study6 reported in 2013 that about 14% of men and 5% of women ages 30 to 70 have an AHI greater than 5 (using 4% desaturation to score hypopneic episodes) with daytime sleepiness. Other studies suggest that 80% to 90% of people with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.1,7

The prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke is much higher, ranging from 30% to 96% depending on the study methods and population.1,8–12 A 2010 meta-analysis11 of 29 studies reported that 72% of patients who had a stroke had an AHI greater than 5, and 29% had severe OSA. In this analysis, 7% of those with sleep-disordered breathing had central sleep apnea; still, these data indicate that the prevalence of OSA in these patients is about 5 times higher than in the general population.

RISK FACTORS MAY DIFFER IN STROKE POPULATION

Several risk factors for OSA have been identified.

Obesity is one of the strongest risk factors, with increasing body mass index (BMI) associated with increased OSA prevalence.4,6,13 However, obesity appears to be a less significant risk factor in patients who have had a stroke than in the general population. In the 2010 meta-analysis11 of OSA after stroke, the average BMI was only 26.4 kg/m2 (with obesity defined as a BMI > 30.0 kg/m2), and increasing BMI was not associated with increasing AHI.

Male sex and advanced age are also OSA risk factors.4,5 They remain significant in patients after a stroke; about 65% of poststroke patients who have OSA are men, and the older the patient, the more likely the AHI is greater than 10.11

Ethnicity and genetics may also play important roles in OSA risk, with roughly 25% of OSA prevalence estimated to have a genetic basis.14,15 Some risk factors for OSA such as craniofacial shape, upper airway anatomy, upper airway muscle dysfunction, increased respiratory chemosensitivity, and poor arousal threshold during sleep are likely determined by genetics and ethnicity.14,15 Compared with people of European origin, Asians have a similar prevalence of OSA, but at a much lower average BMI, suggesting that other factors are significant.14 Possible genetically determined anatomic risk factors have not been specifically studied in the poststroke population, but it can be assumed they remain relevant.

Several studies have tried to find an association between OSA and type, location, etiology, or pattern of stroke.10,11,16–19 Although some suggest links between cardioembolic stroke and OSA,16,20 or thrombolysis and OSA,10 most have found no association between OSA and stroke features.11,12,21,22

HOW DOES OSA INCREASE STROKE RISK?

Untreated severe OSA is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality,21,22 and OSA is an independent risk factor for incident stroke.23 A number of mechanisms may explain these relationships.

Intermittent hypoxemia and recurrent sympathetic arousals resulting from OSA are thought to lead to many of the comorbid conditions with which it is associated: hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke. Repetitive decreases in ventilation lead to oxygen desaturations that result in cycles of increased sympathetic outflow and eventual sustained nocturnal hypertension and daytime chronic hypertension.1,5,9,13 Also implicated are various changes in vasodilator and vasoconstrictor substances due to endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, which are thought to play a role in the atherogenic and prothrombotic states induced by OSA.1,5,13

Cerebral circulation is altered primarily by the changes in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2). During apnea, the Pco2 rises, causing vasodilation and increased blood flow. After the apnea resolves, there is hyperpnea with resultant decreased Pco2, and vasoconstriction. In a patient who already has vascular disease, the enhanced vasoconstriction could lead to ischemia.1,5

Changes in intrathoracic pressure result in distortion of cardiac architecture. When the patient tries to breathe against an occluded airway, the intrathoracic pressure becomes more and more negative, increasing preload and afterload. When this happens repeatedly every night for years, it leads to remodeling of the heart such as left and right ventricular hypertrophy, with reduced stroke volume, myocardial ischemia, and increased risk of arrhythmia.1,5,13

Untreated OSA is believed to predispose patients to develop atrial fibrillation through sympathetic overactivity, vascular inflammation, heart rate variability, and cardiac remodeling.24 As atrial fibrillation is a major risk factor for stroke, particularly cardioembolic stroke, it may be another pathway of increased stroke risk in OSA.16,20,25

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF OSA NOT OBVIOUS AFTER STROKE

OSA typically causes both daytime symptoms (excessive sleepiness, poor concentration, morning headache, depressive symptoms) and nighttime signs and symptoms (snoring, choking, gasping, night sweats, insomnia, nocturia, witnessed episodes of apnea).3,4,26 Unfortunately, because these are nonspecific, OSA is often underdiagnosed.4,26

Identifying OSA after a stroke may be a particular challenge, as patients often do not report classic symptoms, and the typical picture of OSA may have less predictive validity in these patients.1,27,28 Within the first 24 hours after a stroke, hypersomnia, snoring history, and age are not predictive of OSA.1 Patients found to have OSA after a stroke frequently do not have the traditional symptoms (sleepiness, snoring) seen in usual OSA patients. And they have higher rates of OSA at a younger age than the usual OSA patients, so age is not a predictive risk factor. In addition, daytime sleepiness and obesity are often absent or less prominent.1,9,27,28 Finally, typical OSA signs and symptoms may be attributed to the stroke itself or to comorbidities affecting the patient, lowering suspicion for OSA.

OSA MAY HINDER STROKE RECOVERY, WORSEN OUTCOMES

OSA, particularly when moderate to severe, is linked to pathophysiologic changes that can hinder recovery from a stroke.

Intermittent hypoxemia during sleep can worsen vascular damage of at-risk tissue: nocturnal hypoxemia correlates with white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging, a marker of ischemic demyelination.29 Oxidative stress and release of inflammatory mediators associated with intermittent hypoxemia may impair vascular blood flow to brain tissue attempting to repair itself.30 In addition, sympathetic overactivity and Pco2 fluctuations associated with OSA may impede cerebral circulation.

Taken together, such ongoing nocturnal insults can lead to clinical consequences during this vulnerable period.

A 1996 study31 of patients recovering from a stroke found that an oxygen desaturation index (number of times that the blood oxygen level drops below a certain threshold, as measured by overnight oximetry) of more than 10 per hour was associated with worse functional recovery at discharge and at 3 and 12 months after discharge. This study also noted an association between time spent with oxygen saturations below 90% and the rate of death at 1 year.

A 2003 study32 reported that patients with an AHI greater than 10 by polysomnography spent an average of 13 days longer on the rehabilitation service and had worse functional and cognitive status on discharge, even after controlling for multiple confounders. Several subsequent studies have confirmed these and similar findings.8,33,34

OSA has also been linked to depression,35 which is common after stroke and may worsen outcomes.36 The interaction between OSA, depression, and poststroke outcomes warrants further study.

In the general population, OSA has been independently associated with increased risk of stroke or death from any cause.21,22,37 These associations have also been reported in the poststroke population: a 2014 meta-analysis found that OSA increased the risk of a repeat stroke (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–2.6) and all-cause mortality (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.4–2.1).38

TESTING FOR OSA AFTER STROKE

Because of the high prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke and the potential for worse outcomes associated with untreated OSA, there should be a low threshold for evaluating for OSA soon after stroke. Objective testing is required to qualify for therapy, and the gold standard for diagnosis of OSA is formal polysomnography conducted in a sleep laboratory.2–4 Unfortunately, polysomnography may be unacceptable to some patients, is costly, and is resource-intensive, particularly in an inpatient or rehabilitation setting.28 Ideally, to optimize testing efficiency, patients should be screened for the likelihood of OSA before polysomnography is ordered.

Questionnaires can help determine the need for further testing

Questionnaires developed to assess OSA risk39 include the following:

The Berlin questionnaire, developed in 1999, has 10 questions assessing daytime and nighttime signs and symptoms and presence of hypertension.

The STOP questionnaire, developed in 2008, assesses snoring, tiredness, observed apneic episodes, and elevated blood pressure.

The STOP-BANG questionnaire, published in 2010, includes the STOP questions plus BMI over 35 kg/m2, age over 50, neck circumference over 41 cm, and male gender.

A 2017 meta-analysis39 of 108 studies with nearly 50,000 people found that the STOP-BANG questionnaire performed best with regard to sensitivity and diagnostic odds ratio, but with poor specificity.

These screening tools and modified versions of them have also been evaluated in patients who have had a stroke.

In 2015, Boulos et al28 found that the STOP-BAG (a version of STOP-BANG that excludes neck circumference) and the 4-variable (4V) questionnaire (sex, BMI, blood pressure, snoring) had moderate predictive value for OSA within 6 months after sroke.

In 2016, Katzan et al40 found that the STOP-BAG2 (STOP-BAG criteria plus continuous variables for BMI and age) had a high sensitivity for polysomnographically diagnosed OSA within the first year after a stroke. The specificity was significantly better than the STOP-BANG or the STOP-BAG questionnaire, although it remained suboptimal at 60.5%.

In 2017, Sico et al41 developed and assessed the SLEEP Inventory (sex, left heart failure, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, enlarged neck, weight in pounds, insulin resistance or diabetes, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) and found that it outperformed the Berlin and STOP-BANG questionnaires in the poststroke setting. The SLEEP Inventory had the best specificity and negative predictive value, and a slightly better ability to correctly classify patients as having OSA or not, classifying 80% of patients correctly.

These newer screening tools (eg, STOP-BAG, STOP-BAG2, SLEEP) can be used to identify with reasonable accuracy which patients need definitive testing after stroke.

Pulse oximetry is another possible screening tool

Overnight pulse oximetry may also help screen for sleep apnea and stratify risk after a stroke. A 2012 study42 of overnight oximetry to screen patients before surgery found that the oxygen desaturation index was significantly associated with the AHI measured by polysomnography. However, oximetry testing cannot distinguish between OSA and central sleep apnea, so it is insufficient to diagnose OSA or qualify patients for therapy. Further study is needed to examine the ability of overnight pulse oximetry to screen or to stratify risk for OSA after stroke.

Polysomnography vs home testing

Polysomnography is the gold standard for diagnosing OSA. Benefits include technical support and trouble-shooting, determining relationships between OSA, body position, and sleep stage, and the ability to intervene with treatment.2 However, polysomnography can be cumbersome, costly, and resource-intensive.

A home sleep apnea test, ie, an unattended, limited-channel sleep study, may be an acceptable alternative.2–4,43,44 Home testing does not require a sleep technologist to be present during testing, uses fewer sensors, and is less expensive than overnight polysomnography, but its utility can be limited: it fails to accurately discriminate between episodes of OSA and central sleep apnea, there is potential for false-negative results, and it can underestimate sleep apnea burden because it does not measure sleep.2

Institutional resources and logistics may influence the choice of diagnostic modality. No data exist on outcomes from different diagnostic testing methods in poststroke patients. Further research is needed.

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY: BENEFITS, CHALLENGES, ALTERNATIVES

The first-line treatment for OSA is positive airway pressure (PAP).3 For most patients, this is continuous PAP (CPAP) or autoadjusting PAP (APAP). In some instances, particularly for those who cannot tolerate CPAP or who have comorbid hypoventilation, bilevel PAP (BPAP) may be indicated. More advanced PAP therapies are unlikely to be used after stroke.

PAP therapy is associated with reduced daytime sleepiness, improved mood, normalization of sleep architecture, improved systemic and pulmonary artery blood pressure, reduced rates of atrial fibrillation after ablation, and improved insulin sensitivity.45–49 Whether it reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, including stroke, remains controversial; most data suggest that it does not.50,51 However, when adherence to PAP therapy is considered rather than intention to treat, treatment has been found to lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes.52

Mixed evidence of benefits after stroke

Observational studies provide evidence that CPAP may help patients with OSA after stroke, although results are mixed.53–58 The studies ranged in size from 14 to 105 patients, enrolled patients with mostly moderate to severe OSA, and followed patients from 10 days to 7 years. Adherence to therapy was generally good in the short term (50%–70%), but only 15% to 30% of patients remained adherent at 5 to 7 years. Variable outcomes were reported, with some studies finding improved symptoms in the near term and mixed evidence of cardiovascular benefit in the longer ones. However, as these studies lacked randomization, drawing definitive conclusions on CPAP efficacy is difficult.

Patients were enrolled in the index admission or when starting a rehabilitation service—generally 2 to 3 weeks after their stroke. No clear association was found between the timing of initiating PAP therapy and outcomes. All patients had ischemic strokes, but few details were provided regarding stroke location, size, and severity. Exclusion criteria included severe underlying cardiopulmonary disease, confusion, severe stroke with marked impairment, and inability to cooperate. Almost all patients had moderate to severe OSA, and patients with central sleep apnea were excluded.

The major outcomes examined were drop-out rates, PAP adherence, and neurologic improvement based on neurologic functional scales (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and Canadian Neurologic Scale). As expected, dropout rates were higher in patients randomized to CPAP (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.05–3.21, P = .03), although overall adherence was better than anticipated, with mean CPAP use across trials of 4.5 hours per night (95% CI 3.97–5.08) and with about 50% to 60% of patients adhering to therapy for at least 4 hours nightly.

Improvement in neurologic outcomes favored CPAP (standard mean difference 0.54, 95% CI 0.026–1.05), although considerable heterogeneity was seen. Improved sleepiness outcomes were inconsistent. Major cardiovascular outcomes were reported in only 2 studies (using the same data set) and showed delayed time to the next cardiovascular event for those treated with CPAP but no difference in cardiovascular event-free survival.

PAP poses more challenges after stroke

The primary limitation to PAP therapy is poor acceptance and adherence to therapy.59 High rates of refusal of therapy and difficulty complying with treatment have been noted in the poststroke population, although recent studies have reported better adherence rates. How rates of adherence play out in real-world settings, outside of the controlled environment of a research study, has yet to be determined.

In general, CPAP adherence is affected by claustrophobia, difficulty tolerating a mask, problems with pressure intolerance, irritating air leaks, nasal congestion, and naso-oral dryness. Many such barriers can be overcome with use of a properly fitted mask, an appropriate pressure setting, heated humidification, nasal sprays (eg, saline, inhaled steroids), and education, encouragement, and reassurance.

After a stroke, additional obstacles may impede the ability to use PAP therapy.68 Facial paresis (hemi- or bifacial) may make fitting of the mask problematic. Paralysis or weakness of the extremities may limit the ability to adjust or remove a mask. Aphasia can impair communication and understanding of the need to use PAP therapy, and upper-airway problems related to stroke, including dysphagia, may lead to pressure intolerance or risk of aspiration. Finally, a lack of perceived benefit, particularly if the patient does not have daytime sleepiness, may limit motivation.

Consider alternatives

For patients unlikely to succeed with PAP therapy, there are alternatives. Surgery and oral appliances are not usually realistic options in the setting of recent stroke, but positional therapy, including the use of body positioners to prevent supine sleep, as well as elevating the head of the bed, may be of some benefit.69,70 A nasopharyngeal airway stenting device (nasal trumpet) may also be tolerated by some patients.

A proposed algorithm for screening, diagnosing, and treating OSA in patients after stroke is presented in Figure 1.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an independent risk factor for ischemic stroke and may also, infrequently, be a consequence of stroke. It is significantly underdiagnosed in the general population and is highly prevalent in patients who have had a stroke. Many patients likely had their stroke because of this chronic untreated condition.

This review focuses on OSA and its prevalence, consequences, and treatment in patients after a stroke.

DEFINING AND QUANTIFYING OSA

OSA is the most common type of sleep-disordered breathing.1,2 It involves repeated narrowing or complete collapse of the upper airway despite ongoing respiratory effort.3,4 Apneic episodes are terminated by arousals from hypoxemia or efforts to breathe.5 In contrast, central sleep apnea is characterized by a patent airway but lack of airflow due to absent respiratory effort.5

In OSA, the number of episodes of apnea (absent airflow) and hypopnea (reduced airflow) are added together and divided by hours of sleep to calculate the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). OSA is diagnosed by either of the following3,4:

- AHI of 5 or higher, with clinical symptoms related to OSA (described below)

- AHI of 15 or higher, regardless of symptoms.

The AHI also defines OSA severity, as follows3:

- Mild: AHI 5 to 15

- Moderate: AHI 15 to 30

- Severe: AHI greater than 30.

Diagnostic criteria (eg, definition of hypopnea, testing methods, and AHI thresholds) have varied over time, an important consideration when reviewing the literature.

OSA IS MORE COMMON THAN EXPECTED AFTER STROKE

In the most methodologically sound and generalizable study of this topic to date, the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study6 reported in 2013 that about 14% of men and 5% of women ages 30 to 70 have an AHI greater than 5 (using 4% desaturation to score hypopneic episodes) with daytime sleepiness. Other studies suggest that 80% to 90% of people with OSA are undiagnosed and untreated.1,7

The prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke is much higher, ranging from 30% to 96% depending on the study methods and population.1,8–12 A 2010 meta-analysis11 of 29 studies reported that 72% of patients who had a stroke had an AHI greater than 5, and 29% had severe OSA. In this analysis, 7% of those with sleep-disordered breathing had central sleep apnea; still, these data indicate that the prevalence of OSA in these patients is about 5 times higher than in the general population.

RISK FACTORS MAY DIFFER IN STROKE POPULATION

Several risk factors for OSA have been identified.

Obesity is one of the strongest risk factors, with increasing body mass index (BMI) associated with increased OSA prevalence.4,6,13 However, obesity appears to be a less significant risk factor in patients who have had a stroke than in the general population. In the 2010 meta-analysis11 of OSA after stroke, the average BMI was only 26.4 kg/m2 (with obesity defined as a BMI > 30.0 kg/m2), and increasing BMI was not associated with increasing AHI.

Male sex and advanced age are also OSA risk factors.4,5 They remain significant in patients after a stroke; about 65% of poststroke patients who have OSA are men, and the older the patient, the more likely the AHI is greater than 10.11

Ethnicity and genetics may also play important roles in OSA risk, with roughly 25% of OSA prevalence estimated to have a genetic basis.14,15 Some risk factors for OSA such as craniofacial shape, upper airway anatomy, upper airway muscle dysfunction, increased respiratory chemosensitivity, and poor arousal threshold during sleep are likely determined by genetics and ethnicity.14,15 Compared with people of European origin, Asians have a similar prevalence of OSA, but at a much lower average BMI, suggesting that other factors are significant.14 Possible genetically determined anatomic risk factors have not been specifically studied in the poststroke population, but it can be assumed they remain relevant.

Several studies have tried to find an association between OSA and type, location, etiology, or pattern of stroke.10,11,16–19 Although some suggest links between cardioembolic stroke and OSA,16,20 or thrombolysis and OSA,10 most have found no association between OSA and stroke features.11,12,21,22

HOW DOES OSA INCREASE STROKE RISK?

Untreated severe OSA is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality,21,22 and OSA is an independent risk factor for incident stroke.23 A number of mechanisms may explain these relationships.

Intermittent hypoxemia and recurrent sympathetic arousals resulting from OSA are thought to lead to many of the comorbid conditions with which it is associated: hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke. Repetitive decreases in ventilation lead to oxygen desaturations that result in cycles of increased sympathetic outflow and eventual sustained nocturnal hypertension and daytime chronic hypertension.1,5,9,13 Also implicated are various changes in vasodilator and vasoconstrictor substances due to endothelial dysfunction and inflammation, which are thought to play a role in the atherogenic and prothrombotic states induced by OSA.1,5,13

Cerebral circulation is altered primarily by the changes in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (Pco2). During apnea, the Pco2 rises, causing vasodilation and increased blood flow. After the apnea resolves, there is hyperpnea with resultant decreased Pco2, and vasoconstriction. In a patient who already has vascular disease, the enhanced vasoconstriction could lead to ischemia.1,5

Changes in intrathoracic pressure result in distortion of cardiac architecture. When the patient tries to breathe against an occluded airway, the intrathoracic pressure becomes more and more negative, increasing preload and afterload. When this happens repeatedly every night for years, it leads to remodeling of the heart such as left and right ventricular hypertrophy, with reduced stroke volume, myocardial ischemia, and increased risk of arrhythmia.1,5,13

Untreated OSA is believed to predispose patients to develop atrial fibrillation through sympathetic overactivity, vascular inflammation, heart rate variability, and cardiac remodeling.24 As atrial fibrillation is a major risk factor for stroke, particularly cardioembolic stroke, it may be another pathway of increased stroke risk in OSA.16,20,25

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF OSA NOT OBVIOUS AFTER STROKE

OSA typically causes both daytime symptoms (excessive sleepiness, poor concentration, morning headache, depressive symptoms) and nighttime signs and symptoms (snoring, choking, gasping, night sweats, insomnia, nocturia, witnessed episodes of apnea).3,4,26 Unfortunately, because these are nonspecific, OSA is often underdiagnosed.4,26

Identifying OSA after a stroke may be a particular challenge, as patients often do not report classic symptoms, and the typical picture of OSA may have less predictive validity in these patients.1,27,28 Within the first 24 hours after a stroke, hypersomnia, snoring history, and age are not predictive of OSA.1 Patients found to have OSA after a stroke frequently do not have the traditional symptoms (sleepiness, snoring) seen in usual OSA patients. And they have higher rates of OSA at a younger age than the usual OSA patients, so age is not a predictive risk factor. In addition, daytime sleepiness and obesity are often absent or less prominent.1,9,27,28 Finally, typical OSA signs and symptoms may be attributed to the stroke itself or to comorbidities affecting the patient, lowering suspicion for OSA.

OSA MAY HINDER STROKE RECOVERY, WORSEN OUTCOMES

OSA, particularly when moderate to severe, is linked to pathophysiologic changes that can hinder recovery from a stroke.

Intermittent hypoxemia during sleep can worsen vascular damage of at-risk tissue: nocturnal hypoxemia correlates with white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging, a marker of ischemic demyelination.29 Oxidative stress and release of inflammatory mediators associated with intermittent hypoxemia may impair vascular blood flow to brain tissue attempting to repair itself.30 In addition, sympathetic overactivity and Pco2 fluctuations associated with OSA may impede cerebral circulation.

Taken together, such ongoing nocturnal insults can lead to clinical consequences during this vulnerable period.

A 1996 study31 of patients recovering from a stroke found that an oxygen desaturation index (number of times that the blood oxygen level drops below a certain threshold, as measured by overnight oximetry) of more than 10 per hour was associated with worse functional recovery at discharge and at 3 and 12 months after discharge. This study also noted an association between time spent with oxygen saturations below 90% and the rate of death at 1 year.

A 2003 study32 reported that patients with an AHI greater than 10 by polysomnography spent an average of 13 days longer on the rehabilitation service and had worse functional and cognitive status on discharge, even after controlling for multiple confounders. Several subsequent studies have confirmed these and similar findings.8,33,34

OSA has also been linked to depression,35 which is common after stroke and may worsen outcomes.36 The interaction between OSA, depression, and poststroke outcomes warrants further study.

In the general population, OSA has been independently associated with increased risk of stroke or death from any cause.21,22,37 These associations have also been reported in the poststroke population: a 2014 meta-analysis found that OSA increased the risk of a repeat stroke (relative risk [RR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.2–2.6) and all-cause mortality (RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.4–2.1).38

TESTING FOR OSA AFTER STROKE

Because of the high prevalence of OSA in patients who have had a stroke and the potential for worse outcomes associated with untreated OSA, there should be a low threshold for evaluating for OSA soon after stroke. Objective testing is required to qualify for therapy, and the gold standard for diagnosis of OSA is formal polysomnography conducted in a sleep laboratory.2–4 Unfortunately, polysomnography may be unacceptable to some patients, is costly, and is resource-intensive, particularly in an inpatient or rehabilitation setting.28 Ideally, to optimize testing efficiency, patients should be screened for the likelihood of OSA before polysomnography is ordered.

Questionnaires can help determine the need for further testing

Questionnaires developed to assess OSA risk39 include the following:

The Berlin questionnaire, developed in 1999, has 10 questions assessing daytime and nighttime signs and symptoms and presence of hypertension.

The STOP questionnaire, developed in 2008, assesses snoring, tiredness, observed apneic episodes, and elevated blood pressure.

The STOP-BANG questionnaire, published in 2010, includes the STOP questions plus BMI over 35 kg/m2, age over 50, neck circumference over 41 cm, and male gender.

A 2017 meta-analysis39 of 108 studies with nearly 50,000 people found that the STOP-BANG questionnaire performed best with regard to sensitivity and diagnostic odds ratio, but with poor specificity.

These screening tools and modified versions of them have also been evaluated in patients who have had a stroke.

In 2015, Boulos et al28 found that the STOP-BAG (a version of STOP-BANG that excludes neck circumference) and the 4-variable (4V) questionnaire (sex, BMI, blood pressure, snoring) had moderate predictive value for OSA within 6 months after sroke.

In 2016, Katzan et al40 found that the STOP-BAG2 (STOP-BAG criteria plus continuous variables for BMI and age) had a high sensitivity for polysomnographically diagnosed OSA within the first year after a stroke. The specificity was significantly better than the STOP-BANG or the STOP-BAG questionnaire, although it remained suboptimal at 60.5%.

In 2017, Sico et al41 developed and assessed the SLEEP Inventory (sex, left heart failure, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, enlarged neck, weight in pounds, insulin resistance or diabetes, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale) and found that it outperformed the Berlin and STOP-BANG questionnaires in the poststroke setting. The SLEEP Inventory had the best specificity and negative predictive value, and a slightly better ability to correctly classify patients as having OSA or not, classifying 80% of patients correctly.

These newer screening tools (eg, STOP-BAG, STOP-BAG2, SLEEP) can be used to identify with reasonable accuracy which patients need definitive testing after stroke.

Pulse oximetry is another possible screening tool

Overnight pulse oximetry may also help screen for sleep apnea and stratify risk after a stroke. A 2012 study42 of overnight oximetry to screen patients before surgery found that the oxygen desaturation index was significantly associated with the AHI measured by polysomnography. However, oximetry testing cannot distinguish between OSA and central sleep apnea, so it is insufficient to diagnose OSA or qualify patients for therapy. Further study is needed to examine the ability of overnight pulse oximetry to screen or to stratify risk for OSA after stroke.

Polysomnography vs home testing

Polysomnography is the gold standard for diagnosing OSA. Benefits include technical support and trouble-shooting, determining relationships between OSA, body position, and sleep stage, and the ability to intervene with treatment.2 However, polysomnography can be cumbersome, costly, and resource-intensive.

A home sleep apnea test, ie, an unattended, limited-channel sleep study, may be an acceptable alternative.2–4,43,44 Home testing does not require a sleep technologist to be present during testing, uses fewer sensors, and is less expensive than overnight polysomnography, but its utility can be limited: it fails to accurately discriminate between episodes of OSA and central sleep apnea, there is potential for false-negative results, and it can underestimate sleep apnea burden because it does not measure sleep.2

Institutional resources and logistics may influence the choice of diagnostic modality. No data exist on outcomes from different diagnostic testing methods in poststroke patients. Further research is needed.

POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY: BENEFITS, CHALLENGES, ALTERNATIVES

The first-line treatment for OSA is positive airway pressure (PAP).3 For most patients, this is continuous PAP (CPAP) or autoadjusting PAP (APAP). In some instances, particularly for those who cannot tolerate CPAP or who have comorbid hypoventilation, bilevel PAP (BPAP) may be indicated. More advanced PAP therapies are unlikely to be used after stroke.

PAP therapy is associated with reduced daytime sleepiness, improved mood, normalization of sleep architecture, improved systemic and pulmonary artery blood pressure, reduced rates of atrial fibrillation after ablation, and improved insulin sensitivity.45–49 Whether it reduces the risk of cardiovascular events, including stroke, remains controversial; most data suggest that it does not.50,51 However, when adherence to PAP therapy is considered rather than intention to treat, treatment has been found to lead to improved cardiovascular outcomes.52

Mixed evidence of benefits after stroke

Observational studies provide evidence that CPAP may help patients with OSA after stroke, although results are mixed.53–58 The studies ranged in size from 14 to 105 patients, enrolled patients with mostly moderate to severe OSA, and followed patients from 10 days to 7 years. Adherence to therapy was generally good in the short term (50%–70%), but only 15% to 30% of patients remained adherent at 5 to 7 years. Variable outcomes were reported, with some studies finding improved symptoms in the near term and mixed evidence of cardiovascular benefit in the longer ones. However, as these studies lacked randomization, drawing definitive conclusions on CPAP efficacy is difficult.

Patients were enrolled in the index admission or when starting a rehabilitation service—generally 2 to 3 weeks after their stroke. No clear association was found between the timing of initiating PAP therapy and outcomes. All patients had ischemic strokes, but few details were provided regarding stroke location, size, and severity. Exclusion criteria included severe underlying cardiopulmonary disease, confusion, severe stroke with marked impairment, and inability to cooperate. Almost all patients had moderate to severe OSA, and patients with central sleep apnea were excluded.

The major outcomes examined were drop-out rates, PAP adherence, and neurologic improvement based on neurologic functional scales (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale and Canadian Neurologic Scale). As expected, dropout rates were higher in patients randomized to CPAP (OR 1.83, 95% CI 1.05–3.21, P = .03), although overall adherence was better than anticipated, with mean CPAP use across trials of 4.5 hours per night (95% CI 3.97–5.08) and with about 50% to 60% of patients adhering to therapy for at least 4 hours nightly.

Improvement in neurologic outcomes favored CPAP (standard mean difference 0.54, 95% CI 0.026–1.05), although considerable heterogeneity was seen. Improved sleepiness outcomes were inconsistent. Major cardiovascular outcomes were reported in only 2 studies (using the same data set) and showed delayed time to the next cardiovascular event for those treated with CPAP but no difference in cardiovascular event-free survival.

PAP poses more challenges after stroke

The primary limitation to PAP therapy is poor acceptance and adherence to therapy.59 High rates of refusal of therapy and difficulty complying with treatment have been noted in the poststroke population, although recent studies have reported better adherence rates. How rates of adherence play out in real-world settings, outside of the controlled environment of a research study, has yet to be determined.

In general, CPAP adherence is affected by claustrophobia, difficulty tolerating a mask, problems with pressure intolerance, irritating air leaks, nasal congestion, and naso-oral dryness. Many such barriers can be overcome with use of a properly fitted mask, an appropriate pressure setting, heated humidification, nasal sprays (eg, saline, inhaled steroids), and education, encouragement, and reassurance.

After a stroke, additional obstacles may impede the ability to use PAP therapy.68 Facial paresis (hemi- or bifacial) may make fitting of the mask problematic. Paralysis or weakness of the extremities may limit the ability to adjust or remove a mask. Aphasia can impair communication and understanding of the need to use PAP therapy, and upper-airway problems related to stroke, including dysphagia, may lead to pressure intolerance or risk of aspiration. Finally, a lack of perceived benefit, particularly if the patient does not have daytime sleepiness, may limit motivation.

Consider alternatives

For patients unlikely to succeed with PAP therapy, there are alternatives. Surgery and oral appliances are not usually realistic options in the setting of recent stroke, but positional therapy, including the use of body positioners to prevent supine sleep, as well as elevating the head of the bed, may be of some benefit.69,70 A nasopharyngeal airway stenting device (nasal trumpet) may also be tolerated by some patients.

A proposed algorithm for screening, diagnosing, and treating OSA in patients after stroke is presented in Figure 1.

- Selim B, Roux FJ. Stroke and sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin 2012; 7(4):597–607. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2012.08.007

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13(3):479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

- Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, et al; Adult Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management, and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2009; 5(3):263–276. pmid:19960649

- Patil SP, Schneider H, Schwartz AR, Smith PL. Adult obstructive sleep apnea: pathophysiology and diagnosis. Chest 2007; 132(1):325–337. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0040

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev 2010; 90(1):47–112. doi:10.1152/physrev.00043.2008

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 177(9):1006–1014. doi:10.1093/aje/kws342

- Redline S, Sotres-Alvarez D, Loredo J, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2014; 189(3):335–344. doi:10.1164/rccm.201309-1735OC

- Aaronson JA, van Bennekom CA, Hofman WF, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is related to impaired cognitive and functional status after stroke. Sleep 2015; 38(9):1431–1437. doi:10.5665/sleep.4984

- Sharma S, Culebras A. Sleep apnoea and stroke. Stroke Vasc Neurol 2016; 1(4):185–191. doi:10.1136/svn-2016-000038

- Huhtakangas JK, Huhtakangas J, Bloigu R, Saaresranta T. Prevalence of sleep apnea at the acute phase of ischemic stroke with or without thrombolysis. Sleep Med 2017; 40:40–46. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.018

- Johnson KG, Johnson DC. Frequency of sleep apnea in stroke and TIA patients: a meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med 2010; 6(2):131–137. pmid:20411688

- Iranzo A, Santamaria J, Berenguer J, Sanchez M, Chamorro A. Prevalence and clinical importance of sleep apnea in the first night after cerebral infarction. Neurology 2002; 58:911–916. pmid:11914407

- Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, et al. Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(7):841–858. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069

- Dudley KA, Patel SR. Disparities and genetic risk factors in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2016; 18:96–102. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.015

- Redline S, Tishler PV. The genetics of sleep apnea. Sleep Med Rev 2000; 4(6):583–602. doi:10.1053/smrv.2000.0120

- Lipford MC, Flemming KD, Calvin AD, et al. Associations between cardioembolic stroke and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2015; 38(11):1699–1705. doi:10.5665/sleep.5146

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen J, Yi X, Dong S, Cao L. Stroke patterns, topography, and etiology in patients with obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Int J Clin Exp Med 2017; 10(4):7137–7143.

- Fisse AL, Kemmling A, Teuber A, et al. The association of lesion location and sleep related breathing disorder in patients with acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One 2017; 12(1):e0171243. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171243

- Brown DL, Mowla A, McDermott M, et al. Ischemic stroke subtype and presence of sleep-disordered breathing: the BASIC sleep apnea study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015; 24(2):388–393. doi:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.09.007

- Poli M, Philip P, Taillard J, et al. Atrial fibrillation as a major cause of stroke in apneic patients: a prospective study. Sleep Med 2017; 30:251–254. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2015.07.031

- Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, et al. Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Sleep 2008; 31(8):1071–1078. pmid:18714778

- Molnar MZ, Mucsi I, Novak M, et al. Association of incident obstructive sleep apnoea with outcomes in a large cohort of US veterans. Thorax 2015; 70(9):888–895. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206970

- Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 182(2):269–277. doi:10.1164/rccm.200911-1746OC

- Marulanda-Londono E, Chaturvedi S. The interplay between obstructive sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation. Fron Neurol 2017; 8:668. doi:10.3389/fneur.2017.00668

- Szymanski FM, Filipiak KJ, Platek AE, Hrynkiewicz-Szymanska A, Karpinski G, Opolski G. Assessment of CHADS2 and CHA 2DS 2-VASc scores in obstructive sleep apnea patients with atrial fibrillation. Sleep Breath 2015; 19(2):531–537. doi:10.1007/s11325-014-1042-5

- Stansbury RC, Strollo PJ. Clinical manifestations of sleep apnea. J Thoracic Dis 2015; 7(9):E298–E310. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.09.13